Abstract

Background

Community pharmacists have provided health care services uninterruptedly throughout the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. However, their public health role is often overlooked.

Objectives

The purpose of this article is to discuss the roles and the coping mechanisms of community pharmacists working during the COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico.

Methods

A cross-sectional study, using an electronic survey, was conducted to assess the community pharmacists’ response during the COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico. Two open-ended questions explored community pharmacists’ opinions about the pharmacist’s role and coping mechanisms during the pandemic. The responses were analyzed following an inductive thematic analysis. Two major themes emerged from their responses: professional and personal experiences.

Results

Of the 302 participants who completed the survey, 77% of them answered 1 or both open-ended questions. The answers were diverse, and the respondents went beyond the specific topics asked. In professional experiences, important roles as educators and providing continuity of care and emotional support to their patients were highlighted. They also expressed concerns and frustrations on the profession’s shortcomings, feeling overworked yet with a lack of recognition. In personal experiences, most of the respondents were concerned about the impact of having to juggle work and home life. They also reported mental health concerns, expressing feeling stressed, overworked, and worried about the constant risk of exposure and fear of exposing their loved ones.

Conclusion

Community pharmacists in Puerto Rico ensured the continuation of care, provided education, and managed anxious and stressed patients. Most relied on family members to cope with the extra burden that the COVID-19 pandemic. The lack of recognition created resentfulness among participants. It is essential to listen to our community pharmacists’ voices to support and respond to their needs and learn from their experiences as frontline health care workers.

Key Points.

Background

-

•

Despite the uncertainty of COVID-19, pharmacists have continued to provide services in their communities. Their roles and coping mechanisms during this pandemic are unknown.

Findings

-

•

Most community pharmacists felt that their central role was to educate patients, including preventive measures, considering themselves a primary source of information.

-

•

Study participants expressed they were essential in guaranteeing the continuity of care while managing an increased workload. They felt this had taken a toll on their mental health.

Background

Pharmacists have been essential frontline health professionals who have provided continued services during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1, 2, 3 COVID-19, a severe infectious disease caused by a novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.4 In response to this public health threat, the governor of Puerto Rico established a curfew and a general lockdown on March 15. Essential businesses, including pharmacies, remained open and were among the few health care establishments accessible to the public.5 Since then, community pharmacists have provided their health care services uninterruptedly throughout the pandemic. The impact of this experience among community pharmacists has yet to be explored.

Since the onset of the pandemic, pharmacists have ensured the continuity of care, including being the first point of contact for many patients, providing education, managing medication shortages, engaging in virtual consultation, and screening and triaging patients with COVID-19.6 In Puerto Rico, community pharmacists have also been allowed to test and, more recently, to vaccinate for COVID-19.7 Pharmacists are recognized as one of the most accessible health professionals and are key for reaching the desired vaccination rates against COVID-19 in the United States and worldwide.8 , 9 The population of Puerto Rico is approximately 3 million with a life expectancy at 80.9 years.10 Chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, asthma, chronic kidney diseases, and mental health disorders are prevalent and place a financial toll on the Puerto Rico health system. In Puerto Rico, there are approximately 900 community pharmacies distributed among 76 municipalities.11 They provide essential health care services in their communities especially in times of need, such as in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.11

However, regardless of pharmacists’ proximity to their communities and the crucial role they have played during the pandemic, their public health role is often overlooked. When the first COVID-19 case was identified in Puerto Rico on March 13, 2020, the governor of Puerto Rico appointed a Medical Task Force to establish a public health response. This interprofessional group was composed of volunteer scientists and health professionals.12 Although initially, pharmacists were not part of this group, later, a pharmacist with infectious disease expertise was invited to be part of this task force. On May 27, 2020, the governor of Puerto Rico approved financial incentives for health care essential workers,13 but pharmacists were not included. In response, the Colegio de Farmacéuticos (Puerto Rico Pharmacists’ Association) issued a press announcement on August 17, 2020, claiming that pharmacists and pharmacy technicians should be awarded a financial incentive.14 These are some examples of the lack of recognition of the role and efforts of the pharmacy profession in response to the emerging COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico.

Despite the uncertainty of COVID-19, pharmacists have continued to provide services in their communities. By September 2020, there was no information or study regarding community pharmacists’ response during the COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico.

0bjective

The purpose of this article is to discuss the roles and the coping mechanisms of community pharmacists working during the COVID-19 pandemic from their own perspectives.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the community pharmacists’ response during the COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico. An electronic survey was developed on the basis of previously published surveys evaluating pharmacists’ roles in pandemics and on the guidance given by the pharmacy organization’s joint policy recommendations to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.15 , 16 The comprehensive electronic survey was built in REDCap (Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL),17 , 18 and it contained 10 demographic questions and 27 questions on 4 areas: practice and service adaptation and willingness to test, treat, and immunize. It also included 2 open-ended questions: What do you think is the role of the community pharmacy in this COVID-19 outbreak? and How are you coping with the COVID-19 pandemic, personally, and professionally? The survey findings have been published elsewhere.19 For this article, only the open-ended questions were analyzed and reported.

The survey was piloted with 5 pharmacists in Puerto Rico. Their recommendations regarding the structure and wording of the survey were incorporated. The survey was launched on May 18, 2020, and our target population was the 1200 licensed pharmacists in Puerto Rico working in a community setting. The survey was distributed through the Puerto Rico Pharmacist Association’s e-mail Listserv and through social media such as Facebook, Linked In, and pharmacists’ WhatsApp chats. The survey invitation and link were re-sent on a weekly basis for 3 consecutive weeks. The survey was closed on June 12, 2020. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Nova Southeastern University (NSU).

For this article, only the open-ended questions were analyzed and reported. Participants who responded to 1 or both open-ended questions were included in the analysis. Those who were not employed in a community pharmacy were excluded.

Data analysis

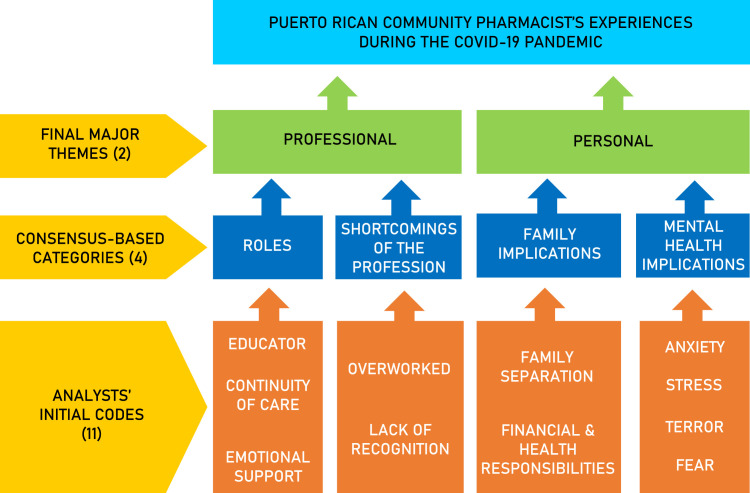

The open-ended questions were analyzed following a thematic analysis approach. The thematic analysis aimed to identify, analyze, and report patterns within the data20 (Figure 1 ). Following a thematic analysis allowed the production of a detailed description of the data set and interpretation of our research topic.

Figure 1.

Thematic analysis steps proposed by Braun and Clarke.20

Three of the authors (G.S.S., A.H.D., and K.R.R.) approached the data set and followed the steps proposed by Braun and Clarke20 (Figure 1). G.S.S. is a Hispanic female researcher with an educational background in public health who has worked with vulnerable populations and public health emergencies, such as natural disasters. She is an assistant professor at NSU College of Pharmacy (COP) at the San Juan Regional Campus. She has conducted and is currently involved in various qualitative research projects and has had formal and informal training in conducting qualitative interviews and focus groups. A.H.D. and K.R.R. were fourth-year student pharmacists at NSU-COP San Juan Regional Campus at the time of the analysis while participating in an academic rotation with G.S.S. They are both Hispanic and female and were trained in qualitative research and data analysis by the first author.

The sanitized data, without any identifiable information, were exported from REDCap to a pdf file. The aforementioned authors engaged in their own independent analysis of the entire data set by reading, re-reading, and noting the initial ideas. Then the questions were split evenly between 2 of the authors (A.H.D. and K.R.R.), which generated initial codes for their respected questions. The first author analyzed and generated codes for the entirety of the data set.

After having the data set completely coded, each author, independently, reviewed their codes, evaluated their pertinence, and collated them into themes. The emerging themes were then cross-checked by each author. When this procedure revealed discrepancies in topics, the coders clarified and discussed other possible interpretations, refined, or created a new code or theme.

The researchers reviewed the themes that were generated and created a final thematic map. The final report is being presented in this article. Open-ended questions were coded and analyzed in their original language, Spanish or English, to preserve their meaning. For this article, quotes have been translated accurately by the authors. To ensure accuracy of the translated quotes, back-translation was conducted by a Hispanic registered nurse with fluency in both English and Spanish (Appendix 1).

Results

A total of 314 participants completed the 27-item survey (26.2% response rate). As previously mentioned, the survey findings have been published elsewhere.19 Participants who were not employed as a community pharmacist at the time of the survey were removed from the sample (n = 12). Of the 302 participants included in the final survey study sample, 77% (n = 233) answered 1 or both open-ended questions. Three files were removed from this sample owing to inappropriate comments or insufficient input to analyze. Only findings from these 230 participants are reported herein. The characteristics of these 230 participants are described in Table 1 . Their work schedule ranged between 4 and 80 hours, with a mean of 38 hours per week. Participants’ responses regarding the role of the pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic and their coping mechanisms were diverse, and the participants went beyond the specific topics that were asked.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographics (n = 230)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 206 (89.5) |

| Male | 24 (10.5) |

| Age, y | |

| ≤ 39 | 111 (48.3) |

| ≥ 40 | 119 (51.7) |

| Education | |

| BS | 100 (33.1) |

| PharmD | 202 (66.9) |

| Graduation year (n = 217)a | |

| Prior 2000 | 133 (61.3) |

| ≥ 2000 | 84 (38.7) |

| Type of pharmacy | |

| Independent or specialty pharmacy | 136(59.1) |

| Chain community pharmacy | 94 (40.9) |

| Position | |

| Pharmacy manager | 75 (32.6) |

| Staff pharmacist | 87 (37.9) |

| Floating pharmacist | 35 (15.2) |

| Pharmacy owner | 33(14.3) |

Of the 230 participants, only 217 answered this question.

After following an inductive thematic analysis process, 19 codes were originally identified. These were narrowed down on the basis of their recurrence, relevance, and relationship across them. Eleven codes were categorized into 4 consensus-based categories and further classified into 2 major themes: professional and personal experiences (Figure 2 ). These 2 themes helped better understand the community pharmacists’ experiences during COVID-19. Actual quotes from the participants’ responses are presented to support the results. Original quotes are included in Appendix 2.

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the data analysis and reduction process.

Professional

Regarding their professional experiences, most community pharmacists considered that they had an important role as educators in providing continuity of care and emotional support to their patients. In addition, they expressed their concerns and frustrations on the shortcomings of the profession, most of them expressing feeling overworked yet with a present lack of recognition as essential health care providers.

Patient education

Most participants felt that their central role was to educate patients, considering themselves as a primary source of information. They provided education regarding preventive measures for COVID-19, symptom identification, tips to improve the immune system, and recommendations for over-the-counter products. They educated about the proper use of masks, hygiene, and physical distancing. As 1 of the study participants stated about their role, “Educate clients and patients about prevention, keeping a healthy lifestyle, being ready to respond questions and providing resources for anybody’s needs” (female, owner of an independent pharmacy).

Continuity of care

Another vital role highlighted by the study participants was to maintain the continuity of care. This was accomplished by dispensing maintenance medications to patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, that required continued treatment and evaluation. A frequent recommendation mentioned was to take home the 90-day supply of medications to decrease the number of visits to the pharmacy and avoid unnecessary exposure.

Participants stated that they also had had to provide emotional support to their patients. They mentioned that some of their patients visited the pharmacy looking for a sense of stability, security, and words of comfort that would alleviate the anxiety caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the words of a participant, “Many times, we notice in our consults that they just want to hear words of encouragement and security amid the crisis, and that has also become part of our role. This is because patients know that we are health professionals prepared, accessible, and have gained their trust” (female, floating pharmacist, in an independent pharmacy).

Shortcomings of the profession

The community pharmacists expressed having to deal with an increased workload, identifying factors such as lack of employees, shorter work hours, and taking on the roles of other health professionals. Some mentioned that physicians had remained closed initially during the pandemic, and they had to attend to their patients. Others remarked having to take on extra shifts because of other “floater” pharmacists refusing to work. Adding to normal pharmacists’ duties, participants described having the extra load of getting personal protective equipment for their employees, creating new protocols, and dealing with anxious staff and patients. As a respondent said,

At first, it was very hard because the pharmacy never closed, and we had to make many changes in the way we worked, on the protocols and the physical structure. It was not easy to find protective equipment and educating, not only patients but staff also. The workload increased, and at the same time, the work hours shortened. Also, there is the fear of bringing the virus home (female, pharmacy manager working in an independent pharmacy).

There was also an overwhelming underlying outcry from the participants about the lack of recognition for their work and their efforts during the pandemic. Not only from their employers but specifically directed toward the government and the professional pharmacists’ associations. Many participants reported feeling forgotten and outraged at the fact that pharmacists were left out of all projects aimed at recognizing and incentivizing essential workers and health professionals, despite providing continued service since the start of the pandemic. One pharmacist commented,

It is challenging as a health care professional to risk our own health and our families to be able to uphold our commitment to the community’s health. I believe that [the professional pharmacist associations] have not been proactive or diligent in pleading for our profession. They have left us completely on the sidelines to the public, even our own government, when we pharmacists have been on the front lines, receiving all the public, because we are the health care professionals who are most accessible to them. Every time we get assigned more tasks and responsibilities, for the same salary and with the same lack of employees. I think that they should emulate other Associations that have defended their health care professionals regarding financial incentives and help from the government and defending the role of their professionals (female, owner of an independent pharmacy).

Some participants even went as far as citing this as the reason they would not volunteer for COVID-19 testing since it posed too big of a risk, and their employer and government did not seem too concerned about them as a professional or an employee.

Personal

Family implications

The respondents expressed how hard it was to juggle work and home life with increasing concerns about exposing family members. Some participants mentioned having to deal with childcare and homeschooling because their children were now at home unattended or having to separate themselves from their young and immunocompromised family members to prevent infecting them. To cope with this situation, some opted to send their children to live with family members, paying for teachers and people to take care of them, and having strict rules for physical contact. One pharmacist commented,

The workload in terms of [the number of prescriptions] hasn’t increased, but the support systems to handle them have suffered. I now have to divide my time between childcare for two kids [ages three and six], homeschooling, house upkeep, plus all the pharmacy-related tasks. All this without daycare, schools, family to help out, puts a severe strain on family and work dynamics (female, owner and manager of an independent pharmacy).

Another pharmacist, who had given birth during the pandemic, commented on how difficult it had been for her to take care of her newborn while still working and being exposed in the pharmacy.

Along with family obligations and responsibilities came the financial instability during the pandemic. Many pharmacists reported feeling worried about dwindling sales in their pharmacies, lack of financial stimulus from the government, and no hazard pay from their employers. Some respondents shared that they are considered high risk or are immunocompromised and yet continue working to meet their financial responsibilities. In the words of a participating pharmacist,

...[there is] financial insecurity and inability to self-isolate for a long period or work from home if needed due to health concerns. Not having sick benefits as an exempt employee causes emotional hardship when deciding between a paycheck or being safe and protecting yourself and coworkers. I am in constant stress about PPE [referring to personal protective equipment] availability at work as it’s not secure, and I am experiencing frequent panic attacks and guilt from not being able to provide care as I wish because of fear (female, staff pharmacist of a chain pharmacy)

Mental health implications

Finally, the most talked-about topic was the impact of the current situation on the pharmacist’s mental health. Participants talked about dealing with anxiety, depression, and the terror of getting sick or getting someone else sick. Some pharmacists mentioned having frequent panic attacks and even worsening headaches owing to the immense stress they were subjected to. One respondent shared, “It was very hard for me at first, I felt depressed, constantly listening to the news, and I was scared. It has sunken in now; this is our reality, and we must live with it. There are days that I get angry, and I want to cry out of frustration due to physicians who disappeared, ill-informed patients, and a rise in prescriptions, but I must take it one day at a time” (female, staff pharmacist of a chain pharmacy). Another pharmacist shared, “It has been incredibly hard to cope with personal issues and the increased workload in the pharmacy. The number of situations that happen in the pharmacy daily due to COVID-19 makes the environment very volatile. Also, trying to deal with a fear of exposure, stress, and anxiety has challenged me in many ways” (female, working on an independent pharmacy).

Discussion

The COVID-19 outbreak has highlighted the importance of the role of pharmacists in the health care system. They have continued to provide their health services, accompanied by the added workload the current pandemic has brought on.21 This survey was launched as the pandemic was emerging (early May 2020), and there were many uncertainties. Exploring their experiences regarding their roles and their coping mechanisms during this time exposed many issues in both professional and personal aspects. Evaluating and addressing these concerns can help community pharmacists to better prepare for future public health emergencies.

Community pharmacists are aware of the influence they have on their patients, and because of to their accessibility, patients see them more often than their primary care physicians.22 Hence, in many instances, they are the first point of contact for the resolution of health issues. This remained true during the emerging COVID-19 pandemic. Their role as educators and patient counselors was a recurrent theme among this cohort. This role went beyond physical health and included words of encouragement and support for anxious patients who could not remain calm during these uncertain times. Studies have shown that, for many people, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in psychological deterioration.6 , 23 , 24 In addition, pharmacists have had to step up and take on a more active role with patients since, as stated by the participants, many physician’s offices were closed, or patients were just not able to contact their primary care physicians.21

Community pharmacists typically have a long list of responsibilities that have expanded to meet the needs of COVID-19, specifically a growing need to educate both patients and their staff and conduct both testing and vaccinations for COVID-19.2, 15, 25 Many study participants expressed their exhaustion owing to having to keep up with their usual duties with less staff, shorter working hours, and the confusion of scared patients. Pharmacists reported an increase in the workload and how being overworked may have consequences on the quality of care.

The reported increase in workload accompanied by the fear and uncertainty of COVID-19 was exacerbated by their perceived lack of recognition from the public and the Puerto Rico government. Leaving pharmacists out of the financial incentives caused outrage and hurt in the pharmacy community.26 In Ontario, Canada, pharmacists had to endure similar situations. They failed to be recognized as frontline health professionals and were left without the economic stimulus provided by the local government.27 The comments expressed as part of this study revealed the work that pharmacists do daily and the augmented stress and increase in workload that they experienced. Community pharmacists in this survey clearly resented their exclusion from governmental recognition and felt that pharmacy associations underrepresented them. They expressed a desire that their profession is taken as seriously as their contributions to the health of society.

The underappreciation of pharmacists during the pandemic and the stress of managing the COVID-19 requirements added an extra burden to their mental well-being.6 , 28 Amid a worldwide pandemic, anxiety, stress, and fear are rampant because so many aspects of daily life have been altered.29 However, for those who never got a chance to interrupt their work to attend to their personal responsibilities, these issues were heightened. A study conducted in Wuhan, China, concluded that mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, and insomnia were significantly greater in frontline medical workers.29 The respondents reported the overwhelming stress they had been subjected to and how little was being done to address their concerns. Overworked, underappreciated, stressed, and fearful pharmacists could lead to medical errors.30 This is a major issue that should be recognized and addressed in educational efforts to prepare for future public health threats.

This study was conducted in May 2020, when there was still much uncertainty about COVID-19. Data collection was conducted approximately 3 months after the lockdown was implemented, and pharmacists had continued to provide services without the option of telehealth or other alternatives available to other primary care centers. The responses to the open-ended comments analyzed in this study reflect the experiences in this specific time period and may have now changed. Nearly two-thirds of the survey participants expanded in the open comments, yet the results do not necessarily reflect the opinions or experiences of all community pharmacists on the island. The 2 major themes that framed the results section could have been influenced by the structure of 1 of the open-ended questions.

Conclusion

This study explored the community pharmacists’ experience regarding their role and coping mechanism during the COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico. Being the first point of contact for their patients, they ensured the continuation of care, provided education, and even managed anxious and stressed patients. Most relied on family members to cope with the extra burden that the COVID-19 pandemic put on them and on taking “one day at a time.” The reported lack of recognition put an extra toll on them, creating resentfulness among participants. It is essential to listen to the voices of our community pharmacists to support and respond to their needs and learn from their experiences. Community pharmacists need the support to respond to public health emergencies as frontline health care workers.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the research team’s invaluable contribution to this project. Our gratitude to Jesus Sanchez, PhD, Silvia E. Rabionet, EdD, and Blanca I. Ortiz, PharmD.

Biographies

Georgina Silva-Suárez, PhD, CHES, Assistant Professor, College of Pharmacy, Nova Southeastern University, San Juan, PR

Yarelis Alvarado Reyes, PharmD, BCPS, BCCCP, Clinical Assistant Professor, College of Pharmacy, Nova Southeastern University, San Juan, PR

AnaHernandez-Diaz, PharmD(c), Student Pharmacist, College of Pharmacy, Nova Southeastern University, San Juan, PR

Keysha Rodriguez Ramirez, PharmD(c), Student Pharmacist, College of Pharmacy, Nova Southeastern University, San Juan, PR

Frances M. Colón-Pratts, PharmD, CDCES, Clinical Assistant Professor, College of Pharmacy, Nova Southeastern University, San Juan, PR

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest or financial relationships.

Appendix

Appendix 1

Back-translation

June 17, 2021

Performed by: Maria T. Silva, RN

- She was born and raised in Puerto Rico and has lived in United Stated for more than 27 years. She is a registered nurse in Orlando Health.

| ORIGINAL TEXT | TRANSLATION | BACK-TRANSLATION |

|---|---|---|

| "Educate clients and patients about prevention, keeping a healthy lifestyle, being ready to respond questions and providing resources for anybody's needs." (Female, owner of an independent pharmacy). | ||

| “Muchas veces nos damos cuenta que en sus consultas solo quieren escuchar palabras de aliento y seguridad en medio de la crisis y eso también se ha convertido en parte de nuestro rol. Esto es así porque los pacientes saben que somos profesionales de la salud preparado, accesibles y hemos ganado su confianza.” | "Many times, we notice in our consults that they just want to hear words of encouragement and security amid the crisis, and that has also become part of our role. This is because patients know that we are health professionals prepared, accessible, and have gained their trust." (Female, floating pharmacist, in an independent pharmacy). | “Muchas veces, notamos en nuestras consultas que solos quieren escuchar palabras de aliento y seguridad en medio de la crisis, y eso también se ha convertido en parte de nuestro rol. Esto se debe a que los pacientes saben que nosotros somos profesionales de la salud, preparados, accesibles, y que nos hemos ganado su confianza.” (Farmacéutica flotante, una farmacia independiente) |

| “Al principio fue difícil porque la farmacia nunca cerró y tuvimos que hacer muchos cambios en la forma de trabajar, protocolos, en la estructura física, no fue fácil conseguir el equipo de protección y orientar tanto a los pacientes como al equipo de trabajo. El volumen de trabajo aumentó y a la vez se redujo horario. También miedo de traer el virus a mi hogar.” | "At first, it was very hard because the pharmacy never closed, and we had to make many changes in the way we worked, on the protocols and the physical structure. It was not easy to find protective equipment and educating, not only patients but staff also. The workload increased, and at the same time, the work hours shortened. Also, there is the fear of bringing the virus home." (Female, pharmacy manager working in an independent pharmacy). | “Al principio, fue muy difícil porque la farmacia nunca cerró, y nosotros tuvimos que hacer muchos cambios en la forma en trabajamos, sobre los protocolos y la estructura física. No fue fácil encontrar equipo de protección y educar, no solo a los pacientes si no también al personal. La carga de trabajo aumentó y, al mismo tiempo, se redujo las horas de trabajo. Además, existe el temor de llevar el virus a casa.” (Directora de farmacia, que trabaja en una farmacia independiente) |

| Es retante como profesional de la Salud, arriesgar nuestra propia salud y la de nuestras familias para poder cumplir con nuestro compromiso con la salud de la comunidad. Además, entiendo que [las asociaciones de farmacia] no han sido proactivos ni diligentes en abogar por nuestra profesión, nos han dejado al margen completamente ante la población y el mismo gobierno de PR. Cuando los Farmacéuticos estamos en la primera línea de batalla, recibiendo a toda la población porque somos los profesionales de la salud más accesibles a ellos. Y cada vez se nos delegan más tareas y responsabilidades, por el mismo salario y con la misma escasez de empleados en el recetario. Entiendo deben emular a otros Colegios que han defendido a sus profesionales ante la solicitud de ayudas o incentivos del gobierno y defendiendo los roles de sus profesionales. | "It is challenging as a health care professional to risk our own health and our families to be able to uphold our commitment to the community's health. I believe that [the professional pharmacist associations] have not been proactive or diligent in pleading for our profession. They have left us completely on the sidelines to the public, even our own government, when we pharmacists have been on the front lines, receiving all the public, because we are the health care professionals who are most accessible to them. Every time we get assigned more tasks and responsibilities, for the same salary and with the same lack of employees. I think that they should emulate other Associations that have defended their health care professionals regarding financial incentives and help from the government and defending the role of their professionals." (Female, owner of an independent pharmacy). | “Es un desafío como profesional de la salud, arriesgar nuestra propia Salud y la de nuestras familias para poder mantener nuestro compromiso con la salud de la comunidad. Creo que [las asociaciones de farmacéuticos profesionales] no han sido proactivos ni diligentes en abogar por nuestra profesión. Nos han dejado completamente al margen del público, incluso de nuestro propio gobierno, cuando los farmacéuticos hemos estado en primera línea, recibiendo a todo el público, porque somos los profesionales de la salud más accesibles para ellos. Asignados más tareas y responsabilidades, por el mismo salario y con la misma falta de empleados. Creo que deberían emular a otras Asociaciones que han defendido a sus profesionales de la salud en cuanto a incentivos económicos y ayudas del gobierno y defendiendo el rol de sus profesionales.” (Propietaria de una farmacia independiente) |

| "The workload in terms of [the number of prescriptions] hasn't increased, but the support systems to handle them have suffered. I now have to divide my time between childcare for two kids [ages three and six], homeschooling, house upkeep, plus all the pharmacy-related tasks. All this without daycare, schools, family to help out, puts a severe strain on family and work dynamics." (female, owner and manager of an independent pharmacy). | ||

| "...[there is] financial insecurity and inability to self-isolate for a long period or work from home if needed due to health concerns. Not having sick benefits as an exempt employee causes emotional hardship when deciding between a paycheck or being safe and protecting yourself and coworkers. I am in constant stress about PPE [referring to personal protective equipment] availability at work as it's not secure, and I am experiencing frequent panic attacks and guilt from not being able to provide care as I wish because of fear." (female, staff pharmacist of a chain pharmacy). | ||

| “Al principio se me hizo difícil, me sentí depresiva, constantemente escuchaba las noticias y tenía miedo. Ahora lo asimile, esta es nuestra realidad y hay q vivir con eso. Hoy dia que me enojo y quiero llorar por las frustraciones de médicos desaparecidos, pacientes mal informados, el alza de recetas, pero un día a la vez. Creo q deben de resaltar nuestra labor porque nunca se nos toma en consideración en hacer ordenes administrativas y en los beneficios.” | "It was very hard for me at first, I felt depressed, constantly listening to the news, and I was scared. It has sunken in now; this is our reality, and we must live with it. There are days that I get angry, and I want to cry out of frustration due to physicians who disappeared, ill-informed patients, and a rise in prescriptions, but I must take it one day at a time." (female, staff pharmacist of a chain pharmacy). | “ Fue muy duro para mi al principio, me sentía deprimida, escuchaba constantemente las noticias, y tenía miedo. Lo he asimilado ahora; está nuestra realidad, y debemos vivir con ella. Hay días que me enfado, y quiero llorar de frustración por los médicos que desaparecieron, los pacientes mal informados, y el aumento de las recetas, pero debo tomarlo un día a la vez. “ (Farmacéutica en una farmacia de cadena) |

| "It has been incredibly hard to cope with personal issues and the increased workload in the pharmacy. The number of situations that happen in the pharmacy daily due to COVID-19 makes the environment very volatile. Also, trying to deal with a fear of exposure, stress, and anxiety has challenged me in many ways." (female, working on an independent pharmacy). |

Appendix 2

Quotes used as examples in their original language

Ëducate clients and patients about prevention, keeping healthy lifestyle, be ready to respond to questions and providing resources for anybody's needs.

“Muchas veces nos damos cuenta que en sus consultas solo quieren escuchar palabras de aliento y seguridad en medio de la crisis y eso también se ha convertido en parte de nuestro rol. Esto es así porque los pacientes saben que somos profesionales de la salud preparado, accesibles y hemos ganado su confianza. ”

“Al principio fue difícil porque la farmacia nunca cerró y tuvimos que hacer muchos cambios en la forma de trabajar, protocolos, en la estructura física, no fue fácil conseguir el equipo de protección y orientar tanto a los pacientes como al equipo de trabajo. El volumen de trabajo aumentó y a la vez se redujo horario. También miedo de traer el virus a mi hogar. ”

“Es retante como profesional de la Salud, arriesgar nuestra propia salud y la de nuestras familias para poder cumplir con nuestro compromiso con la salud de la comunidad. Además entiendo que [las asociaciones de farmacia] no han sido proactivos ni diligentes en abogar por nuestra profesión, nos han dejado al margen completamente ante la población y el mismo gobierno de PR. Cuando los Farmacéuticos estamos en la primera línea de batalla, recibiendo a toda la población porque somos los profesionales de la salud más accesibles a ellos. Y cada vez se nos delegan más tareas y responsabilidades, por el mismo salario y con la misma escasez de empleados en el recetario. Entiendo deben emular a otros Colegios que han defendido a sus profesionales ante la solicitud de ayudas o incentivos del gobierno y defendiendo los roles de sus profesionales. ”

“The workload in terms of [number of prescriptions] hasn’t increased, but the support systems to handle them have suffered. I now have to divide my time between child care for 2 kids ages (3&6), homeschooling, house up keep plus all the pharmacy-related tasks. All this without daycare, schools, family to help out, puts a very serious strain on family and work dynamics. Taking it day by day and doing the best we can. Not easy, but we will get through it. ”

“Financial insecurity and inability to self-isolate for a long period of time or work from home if needed due to health concerns. Not having sick benefits as an exempt employee causes emotional hardship when deciding between a paycheck or being safe and protecting yourself and coworkers. Constant stress about PPE availability at work as it's not secured. Experiencing frequent panic attacks and guilt from not been able to provide care as I wish because of fear. ”

“Al principio se me hizo difícil, me sentí depresiva, constantemente escuchaba las noticias y tenía miedo. Ahora lo asimile, esta es nuestra realidad y hay q vivir con eso. Hoy dia que me enojo y quiero llorar por las frustraciones de médicos desaparecidos, pacientes mal informados, el alza de recetas, pero un día a la vez. Creo q deben de resaltar nuestra labor porque nunca se nos toma en consideración en hacer ordenes administrativas y en los beneficios. ”

“It has been incredibly hard to cope with personal issues and the increased workload in the pharmacy. The amount of situations that happen in the pharmacy daily due to COVID-19 makes the environment very volatile. Also, trying to deal with fear of exposure, stress and anxiety has challenged me in many ways. I try to give my best to patients every day we can and hope the government will accept us as health care providers capable of providing immunizations, proper education and to advocate about Covid-19 and the proper protective measures to take to avoid exposure to this virus. ”

References

- 1.Cadogan C.A., Hughes C.M. On the frontline against COVID-19: community pharmacists’ contribution during a public health crisis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):2032–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bukhari N., Rasheed H., Nayyer B., Babar Z.-U.-D. Pharmacists at the frontline beating the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2020;13(8):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00210-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elbeddini A., Yeats A. Pharmacist intervention amid the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: from direct patient care to telemedicine. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2020;13:23. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00229-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 Available at:

- 5.Orden Ejecutiva de la Gobernadora de Puerto Rico, Hon. Wanda Vázquez Garced, para viabilizar los cierres necesarios Gubernamentales y Privados para combatir los efectos del Coronavirus (Covid-19) y controlar el riesgo de contagio en nuestra Isla. Departamento del Trabajo y Recursos Humanos 15 Mar 2020. Available at: https://www.trabajo.pr.gov/OE-2020-023.asp. Accessed September 15, 2020.

- 6.Elbeddini A., Wen C.X., Tayefehchamani Y., To A. Mental health issues impacting pharmacists during COVID-19. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2020;13:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00252-0. 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orden Administrativa G-FL. 459: administración de pruebas para detectar el coronavirus realizadas en farmacias de Puerto Rico. Departamento de Salud de Puerto Rico 20 Aug 2020. Available at: http://salud.gov.pr/OA%20COVID19/OA%20459%20Administraci%C3%B3n%20de%20pruebas%20para%20detectar%20COVID-19%20realizadas%20en%20farmacias%20de%20PR.pd. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- 8.Sousa Pinto G., Hung M., Okoya F., Uzman N. FIP's response to the COVID-19 pandemic: global pharmacy rises to the challenge. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2021;17(1):1929–1933. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zikry G., Hess K. Pharmacy as a destination for receiving vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pharmacy Times. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/pharmacy-as-a-destination-for-receiving-vaccines-during-the-covid-19-pandemic Available at:

- 10.Abrons J.P., Andreas E., Jolly O., Parisi-Mercado M., Daly A., Carr I. Cultural sensitivity and global pharmacy engagement in the Caribbean: Dominica, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and St. Kitts. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(4):7219. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maldonado C.L. Echan raices las farmacias de la comunidad. Primera Hora. September 20, 2018;2018 https://www.primerahora.com/noticias/puerto-rico/notas/echan-raices-las-farmacias-de-la-comunidad/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruz-Correa M., Díaz-Toro E.C., Falcón J.L., et al. Public health academic alliance for COVID-19 response: the role of a national medical task force in Puerto Rico. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4839. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resolución Conjunta 555: Incentivo económico a profesionales de la salud (2020). Available at: https://senado.pr.gov/Legislations/rcs0555-20.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- 14.Colegio de farmacéuticos de Puerto Rico reclama nuevamente al gobierno incentivo para farmacéuticos y técnicos de farmacia [press release]. 17 de agosto de 2020. Available at: https://cfpr.org/files/COMUNICADO%20PRENSA%20INCENTIVO%20COLEGIO%20D%20FARMACEUTICOS%20COVID%20AGOSTO%202020.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- 15.Pharmacists as Front-Line Responders for COVID-19 Patient Care. Executive Summary. APhA, ASHP, NASPA, NACDS, HOPA, NCPA, ASCP, AACP, ACCP, NASP, CPNP, ACPE. Available at: https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-centers/Coronavirus/docs/Pharmacist-frontline-COVID19.ashx?la=en&hash=1A5827F821D22FD7C75DDEEF815326BDA88469FF. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 16.SteelFisher G.K., Benson J.M., Caporello H., et al. Pharmacist views on alternative methods for antiviral distribution and dispensing during an influenza pandemic. Health Secur. 2018;16(2):108–118. doi: 10.1089/hs.2017.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95 doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva-Suárez G., Alvarado Reyes Y., Colón-Pratts F.M., Sanchez J., Ortiz B.I., Rabionet S.E. Assessing the willingness of community pharmacists to test–treat–immunize during the COVID-19 pandemic in Puerto Rico. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2021;12(2):109–113. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elbeddini A., Botross A., Gerochi R., Gazarin M., Elshahawi A. Pharmacy response to COVID-19: lessons learnt from Canada. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2020;13(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00280-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuyuki R.T., Beahm N.P., Okada H., Al Hamarneh Y.N. Pharmacists as accessible primary health care providers: review of the evidence. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2018;151(1):4–5. doi: 10.1177/1715163517745517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sher L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM. 2020;113(10):707–712. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serafini G., Parmigiani B., Amerio A., Aguglia A., Sher L., Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM. 2020;113(8):531–537. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Pharmacist Association. APhA COVID-19 RESOURCES: KNOW THE FACTS Pharmacy Models for COVID-19 Testing. Available at: https://aphanet.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/audience/APhACOVID-19PharmacyModelsforTesting0720_web.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2020.

- 26.Carta Circular conjunta con el departamento de Salud - Incentivo Económico a Enfermeros, Enfermeras, Tecnólogos Médicos y Médicos Residentes del sector privado, (2020). Available at: http://www.hacienda.gobierno.pr/publicaciones/carta-circular-num-20-1. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- 27.Government of Ontario Eligible workplaces and workers for pandemic pay. https://www.ontario.ca/page/eligible-workplaces-and-workers-pandemic-pay Available at:

- 28.Farinde A. Evaluate pharmacists’ mental health amid COVID-19. Pharmacy Times. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/evaluate-pharmacists-mental-health-amid-covid-19 Available at: Accessed August 5, 2021.

- 29.Cai Q., Feng H., Huang J., et al. The mental health of frontline and non-frontline medical workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: a case-control study. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson G.M., Wu M.S., Bergin J.K. Pharmacist’s attitudes towards dispensing errors: their causes and prevention. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1999;24(1):57–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.1999.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]