Abstract

Simple Summary

Prognosis of advanced cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma (CSCC) is poor. Recent clinical trials have shown that immunotherapy achieves significantly improved survival of patients with advanced CSCCs. However, few real-world data are available on treatment patterns and clinical outcomes of patients with advanced CSCCs receiving anti-programmed cell-death protein-1 (PD-1). To approach this issue, we conducted a retrospective study on 245 patients with advanced CSCCs from 58 centers who had been enrolled in an early-access program; 240 received cemiplimab. Our objectives were to evaluate, in the real-life setting, best overall response rate, progression-free survival, overall survival and safety. Results demonstrated cemiplimab efficacy in patients with advanced CSCCs, regardless of immune status. Patients with good Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status benefited more from cemiplimab. The safety profile was acceptable.

Abstract

Although cemiplimab has been approved for locally advanced (la) and metastatic (m) cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas (CSCCs), its real-life value has not yet been demonstrated. An early-access program enrolled patients with la/mCSCCs to receive cemiplimab. Endpoints were best overall response rate (BOR), progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), duration of response (DOR) and safety. The 245 patients (mean age 77 years, 73% male, 49% prior systemic treatment, 24% immunocompromised, 27% Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) ≥ 2) had laCSCCs (35%) or mCSCCs (65%). For the 240 recipients of ≥1 infusion(s), the BOR was 50.4% (complete, 21%; partial, 29%). With median follow-up at 12.6 months, median PFS was 7.9 months, and median OS and DOR were not reached. One-year OS was 73% versus 36%, respectively, for patients with PS < 2 versus ≥ 2. Multivariate analysis retained PS ≥ 2 as being associated during the first 6 months with PFS and OS. Head-and-neck location was associated with longer PFS. Immune status had no impact. Severe treatment-related adverse events occurred in 9% of the patients, including one death from toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cemiplimab real-life safety and efficacy support its use for la/mCSCCs. Patients with PS ≥ 2 benefited less from cemiplimab, but it might represent an option for immunocompromised patients.

Keywords: PD-1–blocking antibody, cemiplimab, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, real-life setting, immunocompromised, chronic dermatosis

1. Introduction

Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma (CSCC) is the second most common skin cancer after basal-cell carcinoma [1]. In Europe, the reported age-standardized CSCC incidence ranges from 15 to 77 per 100,000 individuals per year, predominantly occurring in males [2,3]. The incidence is constantly increasing, probably because of early CSCC resection, population aging and changing UV-exposure habits [4].The CSCC risk is heightened for immunocompromised patients, being about 100-times higher after organ transplantation [5,6,7,8,9], and for those CSCC oncogenic human papillomavirus-positive, or with chronic dermatitis, exposure to arsenic or ionizing radiation, or genodermatosis (e.g., dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, xeroderma pigmentosum, albinism and Muir–Torre syndrome) [10,11,12,13,14,15]. At an early stage, CSCC prognosis is excellent, with 90% 10-year survival [16]. However, ~5% of the patients experience local recurrences, ~4% of them develop regional disease and outcomes are fatal for ~2% [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. According to American data [23], the CSCC mortality rate is of the same order of magnitude as that of melanoma. The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of patients with resectable, regional CSCCs was 50–60% [18,19]. The prognosis becomes more uncertain for locally advanced or metastatic disease, with either regional or distant metastases.

Since 2018, anti-programed cell-death protein-1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibodies have emerged as first-line treatments for the management of unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic CSCCs. Cemiplimab was the first immunotherapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency [24], followed by pembrolizumab, in the United States, for patients who are not candidates for curative radiotherapy or surgery [25]. Immunotherapies have demonstrated anti-tumor activity with response rates exceeding 40% and acceptable safety profiles [24,25,26,27].

In France, an early-access program made cemiplimab available to patients with locally advanced or metastatic CSCCs during the time between completion of enrollment in cemiplimab clinical trials and its regulatory approval. This retrospective, multicenter CAREPI trial aimed to evaluate cemiplimab efficacy and safety in the real-life setting of those early-access patients. Our results confirmed cemiplimab efficacy in real life and identified clinical characteristics of those patients associated with progression-free survival (PFS) and OS.

2. Materials and Methods

Patients eligible for the early-access program (August 2018 to October 2019) were adults with locally advanced or metastatic CSCCs not amenable to surgery. Exclusion criteria were active autoimmune diseases or infections, uncontrolled brain metastases, pregnancy or breastfeeding. Patients received intravenous cemiplimab infusions (3 mg/kg every 2 weeks) until death from any cause, unacceptable toxicity, or patient’s or physician’s decision. Investigators were asked to complete a standardized case-report form for each patient included in the early-access program.

This retrospective study was approved by the local Avicenne Hospital Ethics Committee (CLEA-2019-75). The national database has been declared to the French data-protection agency (CNIL approval number 2215607). In compliance with French law, consent regarding non-opposition to collect and use the data was obtained from each patient.

The primary endpoint was the best overall response rate (BOR); secondary endpoints included PFS, OS, duration of response (DOR) and safety. Standard-of-care tumor assessments were carried out at the treating facility without central review. Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5. Efficacy and safety were assessed for all patients who received at least one cemiplimab infusion.

Patient characteristics are expressed as numbers (percentages) for discrete variables, and mean ± standard deviation or median (range) for continuous variables. Data cutoff was 19 June 2020. Median follow-up was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier reverse method. OS and PFS were defined, respectively, as the times from the first cemiplimab dose to death from any cause and until disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. DOR was defined as the time from BOR to first documentation of disease progression. OS, PFS, duration of cemiplimab treatment, and DOR were censored at the date of last information update, estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and expressed as median (95% confidence intervals (CIs)). Prognostic factors associated with PFS and OS were identified with log-rank tests. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model with a step function was used because Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) violated the proportional hazards assumption. PS was determined twice (< or ≥6 months). The cumulative incidence of relapses was estimated according to type of response using competing-risk analyses and were compared with Gray’s test. All tests were two-sided, with significance set at p < 0.05. Analyses were computed with R statistical software V.4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Patients

All information concerning 245 patients, from 58 French centers, was collected. Five patients died before the first infusion and were not analyzed for efficacy and safety. Baseline (pre-cemiplimab) patient characteristics are reported for the 245 intent-to-treat patients in Table 1. Their mean age was 77 years, 73% were male, 27% had PS ≥ 2 and 24% were immunocompromised. Among the 59 immunocompromised, 64% had blood disorders, including 34% with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Among the intent-to-treat population, CSCCs were 35% localized, 39% regional disease and 26% had distant metastases; 11% had chronic dermatitis and 3% had cutaneous ulcers. Two-thirds of CSCCs were located on the head and neck. Histopathological examination revealed 23% were poorly differentiated and 11% exhibited perineural invasion.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all 245 intent-to-treat CSCC patients.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 77.1 ± 13.3 |

| Male sex | 178 (73) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 60 (25) |

| 1 | 118 (48) |

| ≥2 | 66 (27) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) |

| Immunocompromised | 59 (24) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus-positive | 8 (3) |

| Organ transplant | 7 (3) |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 20 (8) |

| Other blood disorders a | 18 (7) |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 6 (3) |

| Genodermatosis | 8 (3) |

| Inherited epidermolysis bullosa | 2 (0.8) |

| Muir–Torre syndrome | 2 (0.8) |

| Xeroderma pigmentosum | 1 (0.4) |

| Ichthyosis | 2 (0.8) |

| Epidermodysplasia verruciformis | 1 (0.4) |

| Chronic dermatitis | 28 (11) |

| Burns | 4 (1.6) |

| Scars | 2 (0.8) |

| Lichen planus | 2 (0.8) |

| Chronic wounds | 9 (4) |

| Warts/condylomas | 4 (1.6) |

| Arsenic keratosis | 2 (0.8) |

| Radiodermatitis | 3 (1.2) |

| Others b | 2 (0.8) |

| ≥3 primary CSCCs | 80 (33) |

| Primary CSCC site | |

| Head-and-neck c | 164 (70) |

| Trunk | 9 (4) |

| Anorectal and/or genital | 12 (5) |

| Arm or leg | 58 (24) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.2) |

| Histopathological characteristics | |

| Poor differentiation | 57 (23) |

| Perineural invasion | 26 (11) |

| Both | 9 (4) |

| None | 69 (28) |

| Unknown | 84 (34) |

| CSCC stage | |

| Localized | 85 (35) |

| Regional | 95 (39) |

| Distant metastases | 64 (26) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) |

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number (%). ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; CSCC, cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. a Other blood disorders included: polycythemia vera, four; Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, three; two each: mantle-cell lymphoma or myelodysplastic syndrome; one each: large B-cell lymphoma, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, essential thrombocythemia, multiple myeloma associated with amyloid light-chain amyloidosis, IgM monoclonal gammopathy, thrombopenia of unspecified cause or idiopathic CD4 lymphocytopenia. b Carcinomas due to phototherapy or erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp. c Including two CSCCs located on the lips.

Regarding previous treatments (see Table S1), 60% of intent-to-treat patients had received radiotherapy and 79% had undergone surgical excision. Moreover, about half had received systemic treatment, which was most frequently (38%) anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) plus chemotherapy. Three-quarters received one line of systemic therapy before cemiplimab.

Cemiplimab administration lasted a median of 5.5 (95% CI 4.6–8.8) months, for a median of 10 (1–40) infusions for each per-protocol patient, with 29% (95% CI 23–36) of the patients still being treated beyond 12 months.

3.2. Efficacy Evaluation

Responses of the 240 assessable patients are detailed in Table 2: 21% complete responses and 29% partial responses, for a BOR of 50% (95% CI 44–57). Only 64% of responses were confirmed. The BORs did not differ according to immunocompromised versus immunocompetent status (50% versus 51%, respectively), with prior systemic treatment versus without (51% versus 50%, respectively; p = 0.9), or according to local, regional or distant disease (48%, 56% or 46%, respectively; p = 0.41). However, the BORs were lower for patients with PS ≥ 2 versus <2 (37% versus 56%, respectively; p = 0.01). Patients with chronic dermatitis tended to have poorer responses than those without (32% versus 52%, respectively; p = 0.06). The disease-control rate was 59.6% (95% CI 53.1–65.8).

Table 2.

Best overall responses (n = 240) as assessed by investigators.

| Outcome | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Complete response | 51 (21) |

| Confirmed | 36 (15) |

| Unconfirmed | 15 (6) |

| Partial response | 70 (29) |

| Confirmed | 41 (17) |

| Unconfirmed | 29 (12) |

| Stable disease | 22 (9) |

| Progressive disease | 84 (35) |

| Not assessable | 13 (5) |

| Best overall response rate, n (% [95% CI]) | 121 (50.4 [43.9–56.9]) |

| Confirmed | 77 (32) |

| Unconfirmed | 44 (18) |

| Best overall disease control rate, n (% [95% CI]) | 143 (59.6 [53.1–65.8]) |

Results are expressed as number (%), unless stated otherwise.

The median time to complete response was 5.9 (range 1.7–13.6) months. Complete responders’ median treatment duration was 11.3 months (range 13–516 days), versus 7.5 months (range 43–595 days) for partial responders. The reasons for cemiplimab discontinuation were not fully available for these patients. Among the 51 complete responders, only three (6%) progressed during follow-up: two progressed on cemiplimab after 318 or 471 days of treatment and one progressed 3 months after stopping cemiplimab, which had been administered for 241 days (see Figure S1). A median of 61 days of follow-up were available for 27 (53%) complete responders after cemiplimab discontinuation: only one of them relapsed. At 1 year, relapses were significantly more frequent for partial responders (53%) than complete responders (9%) (p = 0.007).

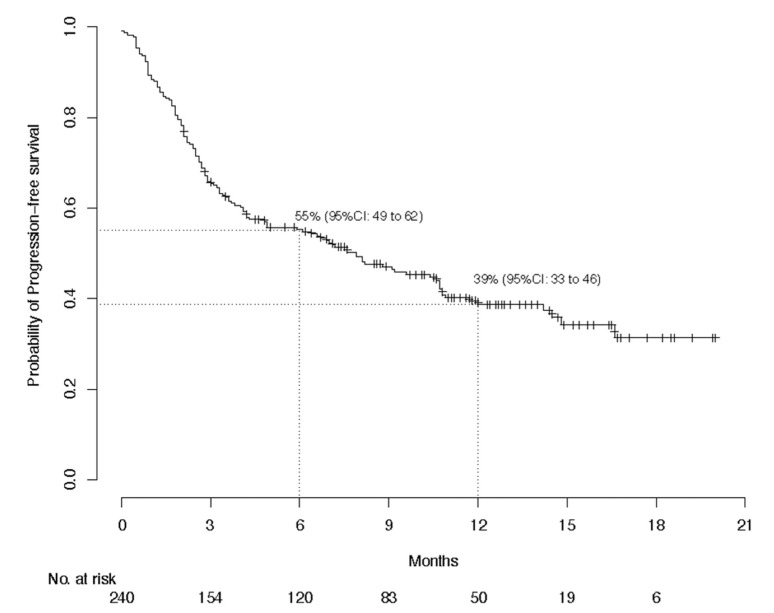

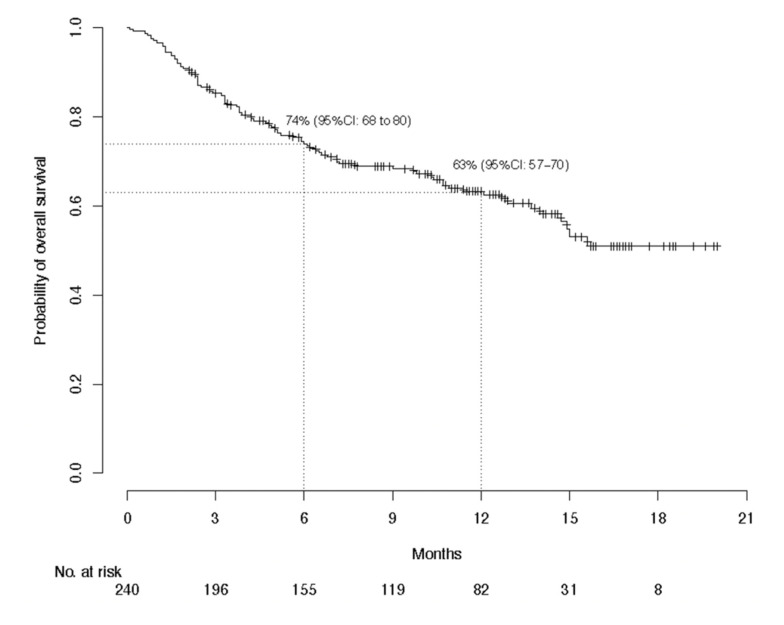

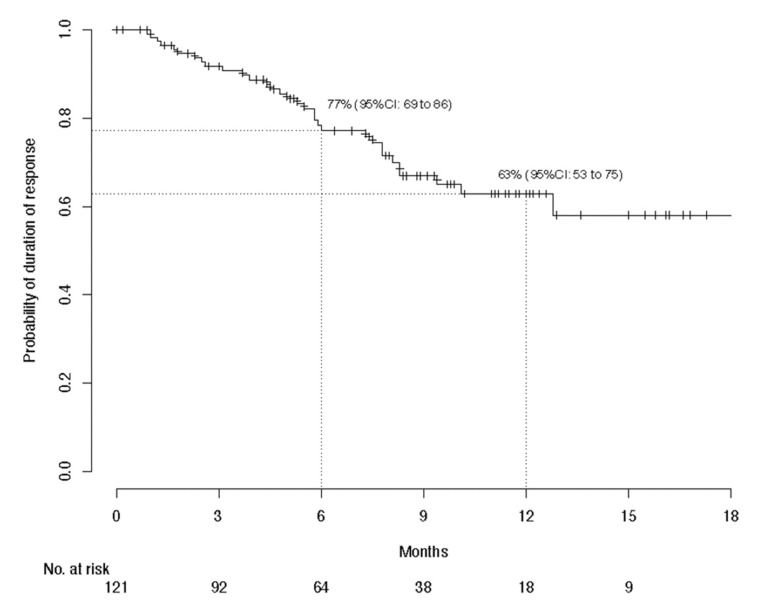

With global median follow-up at 12.6 months, median PFS lasted 7.9 (95% CI, 4.9–10.7) months and 1-year PFS was 38.7%; median global OS was not reached and the 1-year OS was 63.1%; and median global DOR was not reached and the 1-year DOR rate was 62.9% (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). The 1-year PFS and OS rates did not differ according to immune status or previous systemic treatment status (p > 0.21). However, their durations were significantly shorter for patients with PS ≥ 2 versus PS < 2, with respective estimated percentages (95% CI) of 25.1% (15.0–41.8%) and 43.5% (36.3–52.3%) (p < 0.0001) for PFS, and 36% (25–52%) and 73% (66–81%) (p < 0.0001) for OS. The highly significant impact of PS ≥ 2 on PFS and OS was confirmed during the first 6 months, after adjustment for age, sex, chronic dermatitis, primary CSCC site and disease stage (Table 3). After 6 months, PS was no longer associated with PFS or OS. Primary head-and-neck CSCC was also associated with a better PFS.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimations of the 6-month and 1-year probabilities of progression-free survival for the per-protocol population (n = 240).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimations of the 6-month and 1-year probabilities of overall survival for the per-protocol population (n = 240).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimations of the 6-month and 1-year probabilities of duration of response after cemiplimab treatment for the per-protocol population (n = 240).

Table 3.

Factors associated with progression-free survival or overall survival in univariate and multivariate analyses.

| Factor | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Progression-free survival | ||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.62 | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 0.63 |

| Male sex | 0.79 (0.55–1.15) | 0.22 | 0.91 (0.61–1.37) | 0.66 |

| Immunocompromised | 1.03 (0.7–1.51) | 0.89 | 1.15 (0.76–1.76) | 0.5 |

| ECOG PS ≥ 2 | ||||

| ≤6 months | 2.3 (1.53–3.44) | <0.0001 | 2.33 (1.52–3.55) | 0.0001 |

| 6 months | 0.88 (0.31–2.51) | 0.81 | 0.85 (0.3–2.46) | 0.77 |

| Chronic dermatitis | 1.67 (1.02–2.71) | 0.04 | 1.07 (0.61–1.87) | 0.8 |

| Primary head-or-neck CSCC | 0.58 (0.41–0.81) | 0.0002 | 0.52 (0.34–0.79) | 0.0025 |

| Localized disease | 1.16 (0.82–1.64) | 0.41 | 0.72 (0.49–1.05) | 0.09 |

| Previous systemic treatment | 0.88 (0.62–1.23) | 0.44 | 1.03 (0.71–1.50) | 0.88 |

| Overall survival | ||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.81 | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.46 |

| Male sex | 0.9 (0.56–1.44) | 0.66 | 1.01 (0.61–1.67) | 0.97 |

| Immunocompromised | 0.82 (0.49–1.35) | 0.43 | 0.91 (0.53–1.56) | 0.72 |

| ECOG PS ≥ 2 | ||||

| ≤6 months | 4.39 (2.62–7.33) | <0.0001 | 4.56 (2.64–7.85) | 0.0001 |

| >6 months | 1.61 (0.61–4.27) | 0.34 | 1.69 (0.63–4.52) | 0.3 |

| Chronic dermatitis | 0.98 (0.49–1.95) | 0.95 | 0.7 (0.32–1.51) | 0.36 |

| Primary head-or-neck CSCC | 0.76 (0.49–1.18) | 0.22 | 0.67 (0.4–1.13) | 0.13 |

| Localized disease | 1.02 (0.66–1.58) | 0.94 | 0.74 (0.45–1.2) | 0.22 |

| Previous systemic treatment | 0.76 (0.5–1.17) | 0.21 | 1.09 (0.68–1.76) | 0.72 |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; CSCC, cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma.

3.3. Adverse Events

One-third of the patients experienced treatment-related AEs (TRAEs; Table 4), with the most common being (in decreasing order): fatigue, arthralgias/myalgias, hepatic disorders, diarrhea and pruritus. They led to treatment discontinuation for 16 (7%) patients. Twenty-two patients experienced at least one grade-3 or higher TRAE, as detailed in Table 5. They were mostly hepatic disorders and fatigue, but also renal impairment, arthralgias/myalgias, and two kidney-transplant rejections. The death of one patient from toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell’s syndrome) was attributed to cemiplimab. A median of 6 (range 0–70) weeks separated cemiplimab onset and the first AE. The response rates for patients with TRAEs (54.7%) and those without (47.3%) did not differ significantly (p = 0.45).

Table 4.

Each cemiplimab-related adverse event occurred in at least two of the 240 treated patients.

| Adverse Event | Any Grade | Grade ≥ 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Any | 75 (31) | 22 (9) |

| Led to cemiplimab discontinuation | 16 (7) | 12 (5) |

| Fatigue | 21 (9) | 4 (2) |

| Arthralgias/myalgias | 17 (7) | 2 (1) |

| Cholestasis/cytolysis/hepatitis | 10 (4) | 5 (2) |

| Diarrhea | 7 (3) | 0 |

| Pruritus | 6 (3) | 0 |

| Rash | 5 (2) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 5 (2) | 0 |

| Renal failure | 5 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 4 (2) | 0 |

| Lymphopenia | 3 (1) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 3 (1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 3 (1) | 0 |

| Anemia | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Myocarditis | 2 (1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Corticotropic insufficiency | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Colitis | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Vomiting | 2 (1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Loss of weight | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Balance disorder | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Transplant rejection | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

Results are expressed as number (%).

Table 5.

Serious cemiplimab-related adverse events in the 240 treated patients.

| Adverse Event | Severity Grade | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | |

| Cholestasis/cytolysis/hepatitis | 5 (2) | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 4 (2) | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Renal impairment | 3 (1) | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Arthralgias/myalgias | 2 (1) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Colitis | 2 (1) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Transplant rejection | 2 (1) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 1 (0.4) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Myocarditis | 1 (0.4) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 (0.4) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 (0.4) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 1 (0.4) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Results are expressed as number (%) or number.

4. Discussion

This retrospective study on 240 CSCC patients confirmed cemiplimab efficacy in the real-life setting as a curative treatment for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic disease. Patients in this series share characteristics with the 193 patients enrolled in the phase II trial evaluating cemiplimab that led to its approval [24,26,28,29]: predominantly men, older age, 29% poorly differentiated tumors [26], and mostly head-and-neck primary locations. Unlike those study participants, our population included 24% immunocompromised patients, with 16% having blood disorders (i.e., chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other hemopathies), and 27% with PS ≥ 2. Notably, in our series, 49% had received systemic treatment before starting cemiplimab, versus 34% in the phase II trial [28], 3% had a genodermatosis and 11% had an underlying chronic dermatitis, most frequently chronic wounds. The BOR herein was 50%, including 21% complete responses, which is of the same order of magnitude as in other trials evaluating anti-PD-1 [24,25,26,27,28,29].

Our results suggest that immunocompromised patients, including those with blood disorders, respond and survive as well as immunocompetent patients, meaning they apparently benefit from anti-PD-1, despite usually being excluded from trials. However, management of these patients, particularly transplant recipients, must be extremely attentive so as to avoid rejection, as highlighted by the two kidney-transplant rejections observed herein; nonetheless, they should be included in trials. Indeed, anti-PD-1 increased the risk of graft rejection and, when rejection occurred, mortality was recently estimated at 36%, with a high risk for liver-transplant recipients [30]. An ongoing trial is evaluating the safety and efficacy of cemiplimab with everolimus/sirolimus plus prednisone or without as treatment for advanced CSCCs in kidney transplantees (NCT04339062).

Our findings also support that systemic treatment-naïve patients responded as well as pretreated patients. They also showed that frail patients with poor PS responded less well. However, because more than one-third of them responded to cemiplimab, anti-PD-1 should remain the first-line systemic treatment of choice. It is now critical to identify factors predictive of response in these frail patients. Our observations indicate that patients with underlying chronic dermatitis might respond less well to cemiplimab than patients without, but that outcome remains to be confirmed by a larger study.

Remarkably, our complete responders rarely relapsed (6%), even after stopping cemiplimab. Notably, although disease progression after an objective response was observed in 21% of responders, the risk of relapse was markedly higher for partial responders than complete responders, as previously reported for melanoma patients [31,32]. Determining responders’ factors predictive of relapse and optimal treatment duration for partial responders would contribute greatly to improving their management.

Although direct comparison is impossible, for our entire population, 1-year PFS (38.7%) and OS (63.1%) were substantially lower than in Migden et al.’s phase II study [24]. Indeed, their patients’ 1-year PFS and OS ranged between 47% and 58%, and 76% and 93%, respectively, according to the different patient subgroups [28,33]. One factor that could explain this difference would be our overestimation of the response rate, attributable to either the high frequency of unconfirmed responses or the lack of independent central review. Indeed, in Migden et al.’s phase II study [26], the response rate was overestimated by investigators (53%) compared to blinded independent central reviewers (44%), as recently demonstrated by the analysis of 20 trials that had central and investigators’ BOR assessments available [34]. However, our series’ BOR was very close to the investigators’ estimated response rate in Migden et al.’s trial [26].

Another hypothesis might be that our lower-than-expected PFS and OS might reflect our patients’ characteristics, i.e., 27% with PS ≥ 2, whose 1-year OS at 36% was significantly shorter, as reported for lung cancer [35], whereas that OS rate for patients with PS < 2 reached the lower threshold of the OS estimated in the cemiplimab phase II CSCC trial [28,33]. Our best model for OS included only PS, while our best model for PFS included PS and primary head-and-neck. Although it is difficult to attribute a protective effect to head-and-neck CSCCs, it can be hypothesized that the tumor mutational burden would be increased in CSCCs located at that site, a chronically sun-exposed area, compared to other cutaneous areas not chronically sun-exposed. Because high tumor mutational burden predicts prolonged survival in patients receiving anti PD-1 [36], such a higher burden might help explain the association between longer PFS and head-and-neck site retained by our multivariate analysis. Further molecular studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis. Notably, PFS and OS did not differ according to CSCC stage, prior systemic treatment status or immune status, thereby suggesting that it would be of interest to enroll immunocompromised patients in trials evaluating anti-PD-1.

The cemiplimab-safety profile for our series was comparable with that in other studies on PD-1–blocking agents to treat CSCC [24,26,37]. Most AEs were manageable, except for 16 (7% of the patients) that necessitated cemiplimab discontinuation. One cemiplimab-related death from toxic epidermal necrolysis occurred. About 20 Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis cases have been reported with other inhibitors of PD-1 or its ligand [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Toxic epidermal necrolysis is responsible for high mortality [56]. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines, cyclosporine or intravenous immunoglobulins combined with corticosteroids should be initiated when toxic epidermal necrolysis is diagnosed [57]. Indeed, with the increasing use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors, physicians should be aware of this very rare AE. Twenty-two (9%) of our patients developed severe grade-3 or -4 TRAEs, a rate consistent with previous studies on PD-1–blocking agents [24,25,26,50]. One early-onset cemiplimab-induced grade-4 drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms with a favorable outcome occurred in a 76-year-old woman. Considering these frail patients, the safety profile seems acceptable.

Limitations of this study are its retrospective design, the lack of central assessment of disease response, the too short follow-up that precluded accurate determinations of OS, DOR, and the long-term outcomes of responders after stopping anti-PD-1. Indeed, longer follow-up would be helpful. Moreover, PFS results may not be very accurate because assessments were made according to standard of care and may have been performed at different timepoints.

5. Conclusions

The results of this retrospective study confirm cemiplimab’s strong anti-tumor activity and manageable safety, meaning it should be offered to patients with unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic CSCCs. Our analysis of the characteristics of CSCC patients who received cemiplimab in the real-life setting demonstrated the poor prognosis associated with PS ≥ 2. The association between head-and-neck involvement and longer PFS requires additional molecular prognostic studies to determine whether or not that site has a protective effect on PFS for patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease. Moreover, the results of this analysis indicate that cemiplimab might be beneficial for immunocompromised patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Elisa Funck-Brentano from Hôpital Ambroise Paré, AP-HP, Boulogne, who included 3 cases in this study, for her contribution to this study. They would like to thank all members of the Groupe Français de Cancérologie and of the French Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Study Group (CAREPI). They would like to thank other physicians involved in the study and the patients who participated in this early access program. Editorial assistance was provided by Janet Jacobson. The authors thank Margot Denis for technical assistance.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers13143547/s1, Figure S1. The responses for each cemiplimab-recipient and the times at which they and other events occurred are reported. Table S1. Therapies given to the 245 intent-to-treat patients before cemiplimab.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D. (Sophie Dalac), L.M. (Laurent Mortier) and È.M.; formal analysis, M.B. and È.M.; investigation, C.H., L.F. and È.M.; methodology, M.B.; project administration, È.M.; resources, C.H., L.F., A.P.-L., F.H., P.C. (Philippe Celerier), F.A., N.B., M.D. (Monica Dinulescu), A.J., N.M., A.-B.D.-M., L.C., È.-M.N., É.A., B.D., C.L., C.B. (Clémence Berthin), N.K., F.G., J.d.Q., P.-E.S., N.P., J.-P.A., S.A., B.B., S.D. (Sophie Darras), V.H., S.D. (Suzanne Devaux), M.M., L.M. (Laurent Misery), S.M., M.E., F.B.-P., C.J., R.L., F.S., J.S., S.C., M.S., Y.T., D.S. (Dominique Spaeth), C.G.-M., O.C., R.T., M.P., M.D. (Marc Dumas), L.P., P.C. (Pierre Combe), O.L., P.G., Y.R., I.K.-B., D.S. (David Solub), A.S., C.B. (Christophe Bedane) and G.Q.; software, M.B.; supervision, È.M.; visualization, C.H., L.F. and È.M.; writing—review and editing, C.H., L.F., A.P.-L., M.B., F.H., P.C. (Philippe Celerier), F.A., N.B., M.D. (Monica Dinulescu), A.J., N.M., A.-B.D.-M., L.C., È.-M.N., É.A., B.D., C.L., C.B. (Clémence Berthin), N.K., F.G., J.d.Q., P.-E.S., N.P., J.-P.A., S.A., B.B., S.D. (Sophie Darras), V.H., S.D. (Suzanne Devaux), M.M., L.M. (Laurent Misery), S.M., M.E., F.B.-P., C.J., R.L., F.S., J.S., S.C., M.S., Y.T., D.S. (Dominique Spaeth), C.G.-M., O.C., R.T., M.P., M.D. (Marc Dumas), L.P., P.C. (Pierre Combe), O.L., P.G., Y.R., I.K.-B., D.S. (David Solub), A.S., C.B. (Christophe Bedane), G.Q., S.D. (Sophie Dalac), L.M. (Laurent Mortier) and È.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of AVICENNE HOSPITAL (protocol code CLEA-2019-75; date of approval 27 September 2019). The national database has been declared to the French data-protection agency (CNIL approval number 2215607).

Informed Consent Statement

In compliance with French law, consent regarding non-opposition to collect and use the data was obtained from each patient.

Data Availability Statement

Relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Materials and are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

M. Samimi received fees from Janssen Cilag for speaking at an educational meeting and has received reimbursement for travel and accommodation expenses for attending national and international medical congresses from Abbvie, Amgen SAS, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene SAS, Galderma International, Lilly France SAS, MSD France. N. Meyer: Investigator and/or consultant and/or speaker and/or research grants from BMS, MSD, Roche, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Merck, Sanofi, Sun Pharma. J.-P. Arnault: Novartis (boards), speaker (BMS and MSD). E. Maubec: Investigator and/or consultant and/or research grants from BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Sanofi. F. Herms reports receiving fees for consulting, advisory boards and travel accommodations for attending congresses from Sanofi et SUN Pharma. S. Mansard reports participation on boards and having received support for travel accommodations for attending congresses from Sanofi, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, MSD, BMS. G. Quereux reports receiving fees for consulting, advisory boards and being an investigator from Sanofi, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, MSD, Roche and BMS.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rogers H.W., Weinstock M.A., Feldman S.R., Coldiron B.M. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081–1086. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stratigos A.J., Garbe C., Dessinioti C., Lebbe C., Bataille V., Bastholt L., Dréno B., Fargnoli M.C., Forsea A.M., Frenard C., et al. European interdisciplinary guideline on invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: Part 1. epidemiology, diagnostics and prevention. Eur. J. Cancer. 2020;128:60–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maubec E. Update of the management of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. Acta Dermatol. Venereol. 2020;100:adv00143. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen G.B., Ingvar C., Hartman L.W., Olsson H., Nielsen K. Sunbed use increases cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma risk in women: A large-scale, prospective study in Sweden. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2019;99:878–883. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen P., Hansen S., Møller B., Leivestad T., Pfeffer P., Geiran O., Fauchald P., Simonsen S. Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999;40:177–186. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrett G.L., Blanc P.D., Boscardin J., Lloyd A.A., Ahmed R.L., Anthony T., Bibee K., Breithaupt A., Cannon J., Chen A., et al. Incidence of and risk factors for skin cancer in organ transplant recipients in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:296–303. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizvi S.M.H., Aagnes B., Holdaas H., Gude E., Boberg K.M., Bjørtuft Ø., Helsing P., Leivestad T., Møller B., Gjersvik P. Long-term change in the risk of skin cancer after organ transplantation: A population-based nationwide cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1270–1277. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindelöf B., Sigurgeirsson B., Gäbel H., Stern R.S. Incidence of skin cancer in 5356 patients following organ transplantation. Br. J. Dermatol. 2000;143:513–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grulich A.E., van Leeuwen M.T., Falster M.O., Vajdic C.M. Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;370:59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faust H., Andersson K., Luostarinen T., Gislefoss R.E., Dillner J. Cutaneous human papillomaviruses and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: Nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016;25:721–724. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torchia D., Massi D., Caproni M., Fabbri P. Multiple cutaneous precanceroses and carcinomas from combined iatrogenic/professional exposure to arsenic. Int. J. Dermatol. 2008;47:592–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reed W.B., College J., Jr., Francis M.J.O., Zachariae H., Mohs F., Sher M.A., Sneddon I.B. Epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica with epidermal neoplasms. Arch. Dermatol. 1974;110:894–902. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1974.01630120044009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson D.E. An inherited form of large bowel cancer: Muir’s syndrome. Cancer. 1980;45:1103–1107. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800315)45:5+<1103::AID-CNCR2820451313>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King R.A., Creel D., Cervenka J., Okoro A.N., Witkop C.J. Albinism in Nigeria with delineation of new recessive oculocutaneous type. Clin. Genet. 1980;17:259–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1980.tb00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraemer K.H., Lee M.M., Scotto J. Xeroderma pigmentosum. Cutaneous, ocular, and neurologic abnormalities in 830 published cases. Arch. Dermatol. 1987;123:241–250. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1987.01660260111026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karia P.S., Jambusaria-Pahlajani A., Harrington D.P., Murphy G.F., Qureshi A.A., Schmults C.D. Evaluation of American Joint Committee on Cancer, International Union Against Cancer, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital tumor staging for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:327–334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leibovitch I., Huilgol S.C., Selva D., Hill D., Richards S., Paver R. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery in Australia, I. Experience over 10 years. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005;53:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varra V., Woody N.M., Reddy C., Joshi N.P., Geiger J., Adelstein D.J., Burkey B.B., Scharpf J., Prendes B., Lamarre E.D., et al. Suboptimal outcomes in cutaneous squamous cell cancer of the head and neck with nodal metastases. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:5825–5830. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veness M.J., Morgan G.J., Palme C.E., Gebski V. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy in patients with cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to lymph nodes: Combined treatment should be considered best practice. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:870–875. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000158349.64337.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veness M.J., Palme C.E., Morgan G.J. High-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Results from 266 treated patients with metastatic lymph node disease. Cancer. 2006;106:2389–2396. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmults C.D., Karia P.S., Carter J.B., Han J., Qureshi A.A. Factors predictive of recurrence and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: A 10-year, single-institution cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:541–547. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osterlind A., Hjalgrim H., Kulinsky B., Frentz G. Skin cancer as a cause of death in Denmark. Br. J. Dermatol. 1991;125:580–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb14799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karia P.S., Han J., Schmults D. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013;68:957–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Migden M.R., Rischin D., Schmults C.D., Guminski A., Hauschild A., Lewis K.D., Chung C.H., Hernandez-Aya L., Lim A.M., Chang A.L.S., et al. PD-1 blockade with cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:341–351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grob J.J., Gonzalez R., Basset-Seguin N., Vornicova O., Schachter J., Joshi A., Meyer N., Grange F., Piulats J.M., Bauman J.R., et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for recurrent or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: A single-arm phase II trial (KEYNOTE-629) J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:2916–2925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Migden M.R., Khushalani N.I., Chang A.L.S., Lewis K.D., Schmults C.D., Hernandez-Aya L., Meier F., Schadendorf D., Guminski A., Hauschild A., et al. Cemiplimab in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Results from an open-label, phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:294–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maubec E., Boubaya M., Petrow P., Beylot-Barry M., Basset-Seguin N., Deschamps L., Grob J.J., Dréno B., Scheer-Senyarich I., Bloch-Queyrat C., et al. Phase II study of pembrolizumab as first-line, single-drug therapy for patients with unresectable cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:3051–3061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rischin D., Khushalani N.I., Schmults C.D., Guminski A.D., Chang A.L., Lewis K.D., Lim A.M., Hernandez-Aya L.F., Hughes B.G.M., Schadendorf D., et al. Phase II study of cemiplimab in patients (pts) with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC): Longer follow-up. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:10018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.10018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rischin D., Migden M.R., Lim A.M., Schmults C.D., Khushalani N.I., Hughes B.G.M., Schadendorf D., Dunn L.A., Hernandez-Aya L., Chang A.L.S., et al. Phase 2 study of cemiplimab in patients with metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Primary analysis of fixed-dosing, long-term outcome of weight-based dosing. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2020;8:e000775. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen L.S., Ortuno S., Lebrun-Vignes B., Johnson D.B., Moslehi J.J., Hertig A., Salem J.E. Transplant rejections associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A pharmacovigilance study and systematic literature review. Eur. J. Cancer. 2021;148:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robert C., Ribas A., Schachter J., Arance A., Grob J.J., Mortier L., Daud A., Carlino M.S., McNeil C.M., Lotem M., et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-006): Post-hoc 5-year results from an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen Y.J.L., Rozeman E.A., Mason R., Goldinger S.M., Geukes Foppen M.H., Hoejberg L., Schmidt H., van Thienen J.V., Haanen J.B.A.G., Tiainen L., et al. Discontinuation of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy in the absence of disease progression or treatment limiting toxicity: Clinical outcomes in advanced melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2019;30:1154–1161. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Libtayo 350 mg Concentrate Solution for Infusion—Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)—(emc) [Internet] [(accessed on 31 March 2021)]; Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10438.

- 34.Dello Russo C., Cappoli N., Navarra P. A comparison between the assessments of progression-free survival by local investigators versus blinded independent central reviews in phase III oncology trials. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020;76:1083–1092. doi: 10.1007/s00228-020-02895-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsubara T., Seto T., Takamori S., Fujishita T., Toyozawa R., Ito K., Yamaguchi M., Okamoto T. Anti-PD-1 monotherapy for advanced NSCLC patients with older age or those with poor performance status. Oncol. Targets Ther. 2021;14:1961–1968. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S301500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samstein R.M., Lee C.H., Shoushtari A.N., Hellmann M.D., Shen R., Janjigian Y.Y., Barron D.A., Zehir A., Jordan E.J., Omuro A., et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:202–206. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y., Zhou S., Yang F., Qi X., Wang X., Guan X., Shen C., Duma N., Vera Aguilera J., Chintakuntlawar A., et al. Treatment-related adverse events of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1008–1019. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nayar N., Briscoe K., Penas P.F. Toxic epidermal necrolysis-like reaction with severe satellite cell necrosis associated with nivolumab in a patient with ipilimumab refractory metastatic melanoma. J. Immunother. 2016;39:149–152. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saw S., Lee H.Y., Ng Q.S. Pembrolizumab-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome in non-melanoma patients. Eur. J. Cancer. 2017;81:237–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demirtas S., El Aridi L., Acquitter M., Fleuret C., Plantin P. Toxic epidermal necrolysis due to anti-PD1 treatment with fatal outcome. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017;144:65–66. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vivar K.L., Deschaine M., Messina J. Epidermal programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in TEN associated with nivolumab therapy. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2017;44:381–384. doi: 10.1111/cup.12876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rouyer L., Bursztejn A.C., Charbit L., Schmutz J.L., Moawad S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with radiation recall dermatitis in a patient treated with nivolumab. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2018;28:380–381. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2018.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shah K.M., Rancour E.A., Al-Omari A., Rahnama-Moghadam S. Striking enhancement at the site of radiation for nivolumab-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Dermatol. Online J. 2018;24 doi: 10.5070/D3246040713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haratake N., Tagawa T., Hirai F., Toyokawa G., Miyazaki R., Maehara Y. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by pembrolizumab in a lung cancer patient. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018;13:1798–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chirasuthat P., Chayavichitsilp P. Atezolizumab-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome in a patient with non-small cell lung carcinoma. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2018;10:198–202. doi: 10.1159/000492172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffin L.L., Cove-Smith L., Alachkar H., Radford J.A., Brooke R., Linton K.M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) associated with the use of nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) for lymphoma. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:229–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salati M., Pifferi M., Baldessari C., Bertolini F., Tomasello C., Cascinu S., Barbieri F. Stevens-Johnson syndrome during nivolumab treatment of NSCLC. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29:283–284. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwang A., Iskandar A., Dasanu C.A. Stevens-Johnson syndrome manifesting late in the course of pembrolizumab therapy. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019;25:1520–1522. doi: 10.1177/1078155218791314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dasanu C.A. Late-onset Stevens-Johnson syndrome due to nivolumab use for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019;25:2052–2055. doi: 10.1177/1078155219830166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen E.E.W., Soulières D., Le Tourneau C., Dinis J., Licitra L., Ahn M.J., Soria A., Machiels J.P., Mach N., Mehra R., et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;393:156–167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31999-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cai Z.R., Lecours J., Adam J.P. Toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with pembrolizumab. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2020;26:1259–1265. doi: 10.1177/1078155219890659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keerty D., Koverzhenko V., Belinc D., LaPorta K., Haynes E. Immune-mediated toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cureus. 2020;12:e9587. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cassaday R.D., Garcia K.A., Fromm J.R. Phase 2 study of pembrolizumab for measurable residual disease in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2020;4:3239–3245. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riano I., Cristancho C., Treadwell T. Stevens-Johnson syndrome-like reaction after exposure to pembrolizumab and recombinant zoster vaccine in a patient with metastatic lung cancer. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2020;8 doi: 10.1177/2324709620914796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maloney N.J., Ravi V., Cheng K., Bach D.Q., Worswick S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis-like reactions to checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020;59:e183–e188. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dodiuk-Gad R.P., Chung W.H., Valeyrie-Allanore L., Shear N.H. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: An update. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2015;16:475–493. doi: 10.1007/s40257-015-0158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brahmer J.R., Lacchetti C., Schneider B.J., Atkins M.B., Brassil K.J., Caterino J.M., Chau I., Ernstoff M.S., Gardner J.M., Ginex P., et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:1714–1768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Materials and are available from the authors upon reasonable request.