Abstract

In view of the growing concern about the impact of synthetic fungicides on human health and the environment, several government bodies have decided to ban them. As a result, a great number of studies have been carried out in recent decades with the aim of finding a biological alternative to inhibit the growth of fungal pathogens. In order to avoid the large losses of fruit and vegetables that these pathogens cause every year, the biological alternative’s efficacy should be the same as that of a chemical pesticide. In this review, the main studies discussed concern Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts as potential antagonists against phytopathogenic fungi of the genera Penicillium and Aspergillus and the species Botrytis cinerea on table grapes, wine grapes, and raisins.

Keywords: biocontrol, bioprotection, yeasts, non-Saccharomyces, Aspergillus, Penicillium, Botrytis cinerea, table grapes, vinification grapes, raisins, sustainability

1. Introduction

Among microorganisms with food and industrial interest, yeasts are one of the most significant/important agents. This is especially true for Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which has been used for centuries in wine, beer, and bread production and which was the first genetically manipulated eukaryote [1]. In addition, the so-called non-conventional yeast species—e.g., Kluyveromyces lactis (Dombrowski) van der Walt (1971)), Debaryomyces hansenii ((Zopf) Lodder & Kreger-van Rij), Zygosaccharomyces rouxii ((Boutroux) Yarrow), and Z. bailii ((Lindner) Guilliermond (1912))—play a role in traditional food processes [2]. However, several non-conventional species remain largely unexplored both in basic research and for their possible commercialization. This constitutes a huge, untapped reservoir of potential biotechnological innovations which involve the selection of species and strains with new metabolic traits such as the secretion of proteins, adhesiveness, antimicrobial properties, etc. Several genomes of non-conventional yeast species have been completely sequenced and their number continues to grow [3]. Thus, novel methods for the genetic analysis and modification of yeasts, as well as their genomic and post-genomic analysis, will represent a platform for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying both the simple and complex biological features that are useful for the development of novel and eco-compatible applications.

Nowadays, the vitiviniculture sector is highly motivated to develop sustainable approaches to counteract climate change, which affects the entire wine industry across the world. In particular, some areas are affected by increasingly widespread rainfall with the risk of hydrogeological instability, whereas others are affected by unprecedented droughts and heat waves.

From a microbiological point of view, climate change could increase the risk of plant diseases due to the proliferation of pathogenic fungi belonging to the genera Botrytis, Penicillium, and Aspergillus. Their uncontrolled proliferation could cause huge economic losses. This situation has often been managed with the use of pesticides, whose abuse led the European community to establish rules for the sustainable use of agrichemicals to reduce risks and impacts on both people’s health and the environment through the EU Directive 2009/128/CE. Moreover, this directive promotes the use of integrated defense and different approaches or techniques, such as non-chemical alternatives to pesticides, including a biological control approach.

The term “biological control” was used for the first time by Smith (1919) to describe the introduction of natural enemies of exotic insects for the permanent suppression of insect pests [4]. In general, this term includes practically all pest control measures except the application of chemicals. In particular, the use of microorganisms selected as biocontrol agents (BCAs) was later introduced by Baker and Cook (1974) [5]. They defined biocontrol as the reduction in pathogen presence or disease activities by the introduction of one or more antagonist organisms. Biocontrol is successfully applied for constitutive or induced resistance that can be triggered by natural plant products and/or antagonistic microorganisms to control pathogens [6,7]. According to the definition of biocontrol in the agri-food sector, this approach refers to a set of emerging strategies that are alternatives to the use of chemicals for combatting fruit and vegetable diseases. Moreover, biocontrol also extends to food production and preservation [8,9]. Innovative strategies in biocontrol include the use of selected microorganisms or BCAs, with antagonistic activity against other microorganisms, reducing the use of pesticides [6] and boosting food quality and safety [10,11].

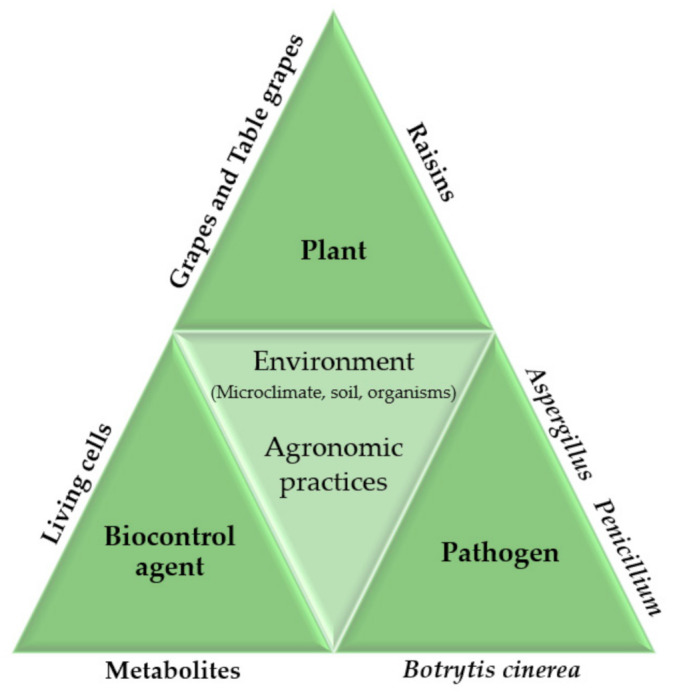

The criteria for the selection of an ideal BCA are the following: It must be genetically stable, effective at a low concentration, not fastidious in its nutritional requirements, capable of surviving under adverse environmental conditions, effective against a wide range of pathogens and different harvested commodities, resistant to pesticides, a non-producer of metabolites harmful to humans, non-pathogenic to the host, in a storable form, and compatible with other chemical and physical treatments. In addition, a microbial antagonist should have an adaptive advantage over specific pathogens [6,7]. Recently, research has aimed at improving their performance in order for them to be used as biopesticides, starting from a thorough examination of the physiological and molecular mechanisms of interaction among all the parties involved (plant, pathogen/parasite, and BCA) to increase the breadth of the BCA spectrum of action [12]. In 1988, Pusey et al. tested and subsequently patented a Bacillus subtilis ((Ehrenberg) Cohn) strain in the USA as the first biocontrol microorganism in post-harvest peach brown rot disease in combination with 2,6-dichloro-4-nitroaniline, water-based wax, paraffin, and mineral oil base [13]. Then, in 1991, the same researchers successfully applied and patented B. subtilis on post-harvest apples and grapes to inhibit the growth of brown, gray, and bitter rots [14]. Later, the yeast species Rhodotorula glutinis ((Fresenius) Harrison) and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa ((Jorgensen) Harrison) were patented as biocontrol agents against mold, the causative agents of gray and blue molds, along with mucor and transit rots of fruit [15]. Subsequently, Wilson et al. in 1998 released a patent on Candida oleophila (Montrocher (1967)) as an agent against post-harvest diseases caused by Penicillium expansum ((Persoon) Saccardo), Penicillium digitatum ((Persoon) Saccardo), and Botrytis cinerea (Persoon (1794)) [16]. Meanwhile, in 2006, the yeast Mestchnikowia fructicola was used against the pathogenic fungi B. cinerea, P. digitatum, and Aspergillus niger (van Tieghem), being able to reduce the post-harvest decay of fruit through competitive inhibition [17]. The advent of high-throughput sequencing (or next-generation sequencing, NGS) technologies is now driving a paradigm change, allowing researchers to integrate microbial community studies into the traditional biocontrol approach [18] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Evolution of biocontrol research towards the integration of microbial communities into the current research triangle (re-adapted by [18]).

Alternatively, it could be interesting to investigate the use of endophytic microorganisms as BCAs. Indeed, fungi and bacteria living in plant tissues can have beneficial effects without causing disease [19,20], such as providing protection against pathogens and environmental stressors [21,22,23]. Several studies have revealed that fungal endophytes produce a variety of effects in their host, such as the release of phytohormones [24] and/or molecules useful for preventing certain plant diseases [25,26,27]. Considering that endophytes occupy the same niche as phytopathogens in plants and compete for space and nutrients, harnessing them as BCAs could represent an innovative way to counteract plant diseases and reduce the utilization of pesticides. In particular, evidence regarding the presence of endophytic grape yeasts belonging to the genera Metschnikowia, Pichia, and Hanseniaspora has been reported in the literature [28,29]. Considering ideal expression systems [30], endophytic yeasts will gain increasing interest for future biotechnological applications as biocontrol agents in plants.

In a period of almost 60 years, from 1963 to 2021, numerous studies have been conducted on the application of biocontrol mechanisms in the agri-food sector. Since 1990, several studies on biocontrol agents of grape pathogens have been carried out. Although some studies have been carried out on the biocontrol of pre- and post-harvest grape, about 48% of the available literature concerns investigations of postharvest grape. Thus, considering the growing interest in the potential role of yeasts as BCAs [30] and the relatively fragmented information related to single species and strains, this review aims to summarize the current knowledge regarding yeast activity against pathogenic fungi on postharvest grapes. Moreover, several pathogens and consequently new yeast species with the potential to be used as BCAs have recently been discovered and citations about their roles are reported here. However, this review was inspired by the scarcity of information related to the biocontrol activity of yeasts against Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., and Botrytis cinerea species—i.e., the three main causes of postharvest grape diseases [31,32,33,34]. Finally, the present work analyzes the relevant mechanisms underlying the antagonistic action of yeasts on the above-mentioned molds and presents a comprehensive table with reference material for a rapid and direct comparison.

2. BCA Mechanisms of Action

At present, the utilization of BCAs is growing quickly in the wine sector since research is shedding light on how they behave (their mode of action), which is key to determining their potential success in industrial applications.

One of the most studied biocontrol mechanisms of action of BCAs is the competition for space and nutrients. This mechanism assumes great importance in post-harvest treatments since numerous infections originate from wounds caused during the collection, selection, packaging, and marketing phases of grapes. Competition is an effective biocontrol activity if the antagonist is present at the same time and location in the pathogen in a sufficient amount, limiting the resources available [34]. Another relevant approach is iron competition, as this involves the antagonist production of siderophores, small molecules with a high affinity for iron and that are capable of chelating Fe3+ ions. This is important in the biocontrol exerted by molds, since iron is fundamental for their growth and for the pathogenesis process [34]. Furthermore, biofilm formation and resistance induction are other possible mechanisms. The formation of biofilms is a specific strategy for the space competition used by BCAs to successfully colonize intact or damaged fruit surfaces and better promote adherence and multiplication.

The induction of resistance in plants consists of stimulating the activation of defense mechanisms by means of elicitors, which are synthetic or natural molecules that mimic the attack of a pathogen or a state of stress. This mechanism can involve the activation of pathogenesis-related proteins (β-1,3-glucanases and chitinases) or defense-related enzymes, such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), peroxidase, and polyphenoloxidase, which are produced by biocontrol agents [35,36].

The production of primary and secondary metabolites, particularly against filamentous fungi, is considered a crucial mechanism of action of BCAs. Among metabolites, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) have a high biocontrol efficacy. They are small (usually <300 Da) molecules with a low solubility in water and a high vapor pressure. VOCs include several molecular classes that show a high spectrum of action as antimicrobials, such as hydrocarbons, alcohols, thioalcohols, aldehydes, ketones, thioesters, cyclohexanes, heterocyclic compounds, phenols, and benzene derivatives [34,35]. This mechanism has great efficacy in the in vitro tests, but when carrying out trials on the fruit surface the applied VOC concentration must be carefully finetuned. Killer toxins are also efficient metabolites for biocontrol. They are proteins or glycoproteins that are lethal for pathogenic fungi or secondary metabolites that are able to inhibit the proliferation of molds on table grapes and grapes [34]. Additionally, the secretion of lytic enzymes by BCAs, such as glucanases, chitinases, lipases, and proteases, is a common feature in all types of host–pathogen interactions and has been extensively studied [34,35].

3. Yeast Applications against Pathogenic Fungi of the Grape in Post-Harvest

From an economic and social point of view, the grape (Vitis vinifera L.) is one of the most widely cultivated fruit plants in the world and is susceptible to infections caused by pathogenic fungi [36]. Therefore, in recent times, the reduction in phytopathogenic fungi attacking the grape has also become of vital interest for vine growers in the post-harvest phase [37]. Microbiological applications to prevent infections represent a new strategic frontier for maintaining the post-harvest quality of table and wine grapes [38,39]. A study conducted in 2000 stated that the application of BCAs in the field allows the early colonization of fruit surfaces, thus protecting against latent infections that occur after harvest. In particular, over the past 20 years the role and mechanisms of yeast activity as a biocontrol against pathogenic fungi have been assessed and described (Table A1, Appendix A).

The pathogenic fungi primarily studied are Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., and B. cinerea. However, other grape pathogenic fungi have lately been mentioned in the literature, such as Rhizopus stolonifera ((Ehrenberg) Vuillemin), Mucor piriformis (A. Fischer), Colletotrichum acutatum (J.H. Simmonds), Alternaria sp. (Nees), and Rhizoctonia sp. (Kühn) [40,41]. The yeasts which exert biocontrol activity against these fungi are Trichoderma harzianum (Rifai), Pichia membranifaciens (E.C. Hansen (1904)), Kloeckera apiculata ((Reess) Janke), Candida guilliermondii (Castellani) Langeron & Guerra var. carpophila Phaff & M.W. Miller (1961)), Cryptococcus laurentii ((Kufferath) CE Skinner), Cryptococcus flavus, Cryptococcus albicus, Candida pyralidae (Kurtzman (2001b)), Pichia kluyveri (Bedford ex Kudryavtsev (1960)), and P. expansum [40,41,42,43,44,45].

3.1. Biological Control against Aspergillus Genus

In recent years, several yeast species have been investigated and used as potential BCAs against Aspergillus carbonarius ((Bainier) Thom), which affect not only grapes but also other fruits. Fungi belonging to the Aspergillus genus are generally responsible for the release of mycotoxins, which are compounds that are harmful to humans, including ochratoxin A [46,47,48], for which extensive legislation has been passed (Regulation (EC) no. 401/2006). Notably, it was demonstrated that the yeasts Trichosporon mycotoxinivorans and Yarrowia lipolytica ((Wickerham, Kurtzman & Herman) van der Walt & von Arx) are able to degrade these toxins [37]. Moreover, in 2017, Cordero-Bueso et al. [49] selected four non-Saccharomyces yeasts (P. kluyveri, Hanseniaspora uvarum ((Niehaus) Shehata, Mrak & Phaff ex M.Th. Smith), Meyerozyma (Pichia) guilliermondii ((Wickerham) Kurtzman et M. Suzuki), and Hanseniaspora clermontiae (Cadez, Poot, Raspor & M.Th. Smith (2003))) to counteract the A. carbonarius infection of grape, and different mechanisms of action were reported. The study revealed that yeasts could inhibit the growth of A. carbonarius through competition for the substrate but not by iron competition. Furthermore, P. kluyveri and H. uvarum also acted through biofilm formation, the secretion of lytic enzymes, the induction of resistance, and the production of killer toxins and VOCs. On the other hand, the yeasts M. guilliermondii and H. clermontiae carried out biocontrol activity through the production of unidentified VOCs and enzymatic activity, respectively. However, regarding the production of VOCs, it is known that Cyberlindnera jadinii ((Sartory et al.) Minter), Lanchea thermotolerans, Candida intermedia ((Ciferri & Ashford) Langeron & Guerra (1938)), and Candida friedrichii (Uden & Windisch (1968)) can inhibit the growth of A. carbonarius and Aspergillus ochraceus through the production of 2-phenylethanol [50,51]. The proliferation of A. niger can be counteracted using the yeast D. hansenii, which works through the production of killer toxins [46]. Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Meyen ex E.C. Hansen (1883)), Wickerhamomyces anomalus ((Hansen) Kurtzman, Robnett & Basehoar-Powers (2008)), Rhodosporidium fluviale, and Rhodosporidium paludigenum were used to prevent the growth of Aspergillus japonicas (Saito), Aspergillus uvarum, and Aspergillus aculeatus (Lizuka) on table grapes post-harvest. These yeasts exhibited biocontrol activity through the production of lytic enzymes, with the exception of W. anomalus, which also produced killer toxins [52]. Recently, yeast species belonging to the genera Saccharomyces, Pichia, Metschnikowia, Dekkera (van der Walt), and Rhodotorula (Harrison (1928)) were found to be able to reduce the growth rate of A. carbonarius, thus offering a set of species potentially acting as antagonists of the pathogenic fungi involved in grape and wine production [53,54].

3.2. Biological Control against Penicillium Genus

Penicillium is one of the most common fungal genera in nature and its several species can proliferate in different habitats. Moreover, some of them are able to produce mycotoxins [55]. P. expansum produces both patulin (PAT) and citrinin (CIT), harmful compounds which provoke potentially high health risks [56]. Thus, the selection of BCAs against some detrimental species of Penicillium in the grape post-harvest phases is advised. Several non-Saccharomyces species show activity towards P. expansum and P. digitatum [49]. In particular, the production of VOCs by Candida sake ((Saito & Oda) van Uden & H.R. Buckley ex S.A. Meyer & Ahearn (1983)) yeast against the former appears effective [57]. W. anomalus, for example, counteracts the proliferation of P. digitatum through the release of killer toxins and lytic enzymes [58]. Additionally, W. anomalus is able to inhibit the growth of the pathogenic fungi P. expansum, Starmerella bacillaris (formerly Candida zemplinina, on apple in post-harvest) (Sipiczki (2003)), and R. paludigenum (on pear in post-harvest) by competition for the substrate, the induction of resistance, and the secretion of lytic enzymes (such as polyphenol oxidase, catalase, and chitinase) [59,60]. Additionally, M. fructicola was proven to possess an antagonistic activity based on iron competition, the induction of resistance, and the production of lytic enzymes against P. digitatum [61]. Recently, two species of Penicillium (Link (1809)), P. rubens (Biourge) [36], and P. georgiense (S.W.Peterson & B.W.Horn) [52], were isolated for the first time on table grapes and identified as post-harvest grape deterioration agents. Y. lipolytica counters P. rubens through the production of lytic enzymes [36]. The same mechanism of action is used by S. cerevisiae, W. anomalus, R. fluviale, and R. paludigenum in counteracting P. georgiense and P. expansum. Moreover, the inhibitory activity of R. paludigenum is also achieved by the induction of resistance and the production of killer toxins [52]. Finally, Yang et al. [62] tested the coupled use of vitamin C and Pichia caribbica (Vaughan-Martini, Kurtzman, S.A. Meyer & O’Neill (2005)) against P. expansum. The results showed that the application of vitamin C could improve the biological control against the fungus by increasing the metabolic activity of the yeast and promoting competition with the pathogen [63].

3.3. Biological Control against B. cinerea

The species B. cinerea (Persoon) is particularly relevant in the wine field for two fundamentally different reasons: It induces diseases in grapes and is also used in raisining wine technology. Since the research on the biocontrol activity of this species is very extensive, this paragraph provides a more thorough analysis than the previous.

B. cinerea is an airborne filamentous fungus that causes grey mold disease [64]. This necrotrophic phytopathogenic fungus is extremely polyphagous and ubiquitous, thus its action extends to almost all regions of the world with great losses in fruit and vegetable crops, including the grapevine [65]. Moreover, B. cinerea produces a polyketide mycotoxin, botcinic acid, during infection [66]. The growth of B. cinerea is commonly controlled through a combination of a fungicide treatment and specific agronomic practices. Indeed, although the latter approach helps minimize infections, it is not sufficient to prevent the disease caused by B. cinerea in many wine-growing areas [67].

Mechanisms of yeast action against the proliferation of B. cinerea have been reported to be mainly linked to the production of enzymatic activities, iron or nutrient competition, and the production of VOCs.

BCAs exerting biocontrol through enzyme production were first reported by Lima et al. in 1998 [68], when two strains belonging to C. laurentii (LS-28) and R. glutinis (LS-11) species were isolated on Italian table grapes. These yeasts showed a high biocontrol activity towards B. cinerea thanks to the secretion of β-1,3-glucanase. Later, other yeasts of the species C. oleophila, D. hansenii, M. guilliermondii, and Metschnikowia were tested in the in vivo tests on table grapes. In particular, the Metschnikowia-like yeast strain LS-15 significantly reduced the grey fungus (from 28.3% to 38.2%) [69], such as M. fructicola (strain NRRL Y-27328, CBS 8853), which showed its possible capability to inhibit Botrytis rot in stored grapes [70]. Additionally, P. membranifaciens FY-101 exhibited antagonistic properties against B. cinerea, preventing the symptoms of grey rot disease in V. vinifera and Vitis rupestris, probably due to the secretion of β-1,3-glucanases [71,72]. Moreover, in 2015, Parafati et al. [73] analyzed the effectiveness of W. anomalus, M. pulcherrima, and Aureobasidium pullulans, isolated from different food sources, as BCAs against B. cinerea. W. anomalus strains were selected for their high kill capacity against the sensitive S. cerevisiae strain, identifying β-glucanase as responsible for the toxicity mechanism. In vitro studies revealed that they were able to reduce mycelial growth with a variable efficacy. Furthermore, while M. pulcherrima and W. anomalus strains showed greater inhibition at pH 4.5 (72.67% and 81.50%, respectively), the A. pullulans strains maintained the same activity at different pH values (such as 70.89% and 71.33%, respectively, at pH 6 and 4.5). Regarding the enzymatic activities, only A. pullulans and W. anomalus strains showed a β-1,3-glucanase activity capable of hydrolyzing laminarin. Additionally, the A. pullulans strains showed pectinolytic and proteolytic activity.

The iron competition mechanism against B. cinerea was elucidated in M. pulcherrima (MACH1) [74]. In culturing MACH1 with different iron concentrations (supplemented as FeCl3) together with B. cinerea, it was observed that the yeast strain produced a wide pigmented zone of inhibition when the iron concentrations were low. In addition, in the inhibition zones, the conidia of the pathogen did not germinate and mycelial degeneration was observed. Furthermore, in vivo experiments on apples supplemented with low iron conditioning revealed a greater reduction in infection compared to a high iron conditioning state. Thus, iron deficiency appears to be an important factor in the biocontrol exerted by yeast against various fungal pathogens. Indeed, as described in Parafati (2015) [73], M. pulcherrima strains synthesize pigments such as pulcherrimin, producing the widest zones of inhibition in absence of FeCl3 [75]. Later, Cordero-Bueso et al. [49] corroborated this mechanism of action against B. cinerea on grapes.

Competition for nutrients plays an important role in the K. apiculata’s biological control capability against B. cinerea. Specifically, the strain 34-9 isolated from citrus roots exhibited rapid colonization of grape wounds and a great ability to control B. cinerea in the in vivo and in vitro tests on grapes (V. vinifera L. × Vitis labrusca L. cv. Kyoho) [76]. In addition, H. uvarum (anamorph K. apiculata) was used in combination with tea polyphenols (TP) against B. cinerea on V. vinifera L. Kyoho. The results showed that TP significantly increased the yeast population and efficacy at the different tested concentrations. This case is an example of how the biocontrol activity exhibited by some antagonists can be improved [77].

In general, the composition of the microbiota appears to be relevant in the control of B. cinerea, as reported in a study carried out on grapes involved in the production of the Italian straw wine “Vino Santo Trentino”, which uses the “Nosiola” grape [78], where the Hanseniaspora, Metschnikowia, Cryptococcus, and Issatchenkia genera were identified. Their presence was intricately related to the extent of infection caused by B. cinerea. Moreover, these microorganisms are poorly resistant to ethanol and have low pH values, thus they did not represent a risk for either the winemaking process or the development of bad flavors, since they disappear during the process [78]. Another noticeable microbiota is the one identified on mummified grapes infected with B. cinerea during winter (noble rot) in the Tokaj region (Hungary) [79]. The presence of viable strains showed that mummified grapes could serve as a safe yeast reservoir and could contribute to maintaining these colonizing populations of grapes in the vineyard over time. Indeed, among the most frequent isolates it was possible to detect three species of Hanseniaspora, pigmented strains of Metschnikowia, three species of Saccharomyces (S. paradoxus, S. cerevisiae, and S. uvarum), Aureobasidium subglaciale, Kabatiella microsticta (Bubk (1907)), Columnosphaeria fagi, and W. anomalus. These yeasts maintained complex interactions with B. cinerea, including antagonism (growth and contact inhibition, competition for nutrients) and synergism (cross-feeding). The Metschnikowia strains showed antagonistic activity against Botrytis, inhibiting the germination of their conidia and the extension of their hyphae, probably due to competition for iron, while S. paradoxus and S. uvarum activities were associated with competition for nutrients [79].

Wang et al. (2018) [80] evaluated the biocontrol exerted by 10 non-Saccharomyces yeasts strains, isolated from vineyards, against B. cinerea on “Thompson seedless” table grapes. The isolates belonged to the species A. pullulans, Candida saitoana (Nakase & M. Suzuki (1985)), Curvibasisium pallidicorallinum, Metschnikowia chrysoperlae, M. pulcherrima, M. guilliermondii, and W. anomalus. All of them rapidly colonized grape berries, with W. anomalus being the most effective. The results suggested that the latter was the most effective and that the biocontrol mechanism of these yeasts was the competition for the niche.

Cordero-Bueso et al. (2017) investigated the potential biocontrol action of epiphytic non-Saccharomyces yeast strains isolated from grape berries from V. vinifera spp. sylvestris and V. vinifera spp. against B. cinerea [49]. Of the 19 antagonist strains belonging to seven different species, the most effective in reducing the incidence of B. cinerea were H. clermontiae (Cadez, Poot, Raspor & M.Th. Smith (2003)), H. uvarum, M. guilliermondii, and P. kluyveri. In particular, P. kluyveri strain SEHMA6B has shown to be more effective against B. cinerea than the synthetic fungicides. Moreover, in 2019, Carmichael et al. [81] evaluated the abundance and the diversity of yeast populations already known as natural antagonists of postharvest pathogens (Aureobasidium, Cryptococcus, Rhodotorula, and Sporobolomyces), with a particular focus on their action against B. cinerea, in the different phenological stages of table grapes (variety crimson seedless). The results of this study showed that a high presence of populations of possible biocontrol yeasts was associated with a low prevalence of pathogenic groups. The development stages of table grapes with low concentrations of B. cinerea presented an abundance of Rhodotorula, Aureobasidium, and Cryptococcus.

While the biocontrol mechanisms on table grapes have been widely investigated, the antagonism of yeasts against B. cinerea in raisin grapes is poorly documented. The work of Ribereau-Gayon in 1970 [82] suggested that B. cinerea acts as an active component in the raisins of certain grapes. The role of Botrytis depends on the environmental conditions. When the berry tissue remains intact until its maturity, B. cinerea causes a “noble putrefaction” that improves the constitution of the berry. It dries out the berry and increases the sugar concentrations but the acidity only slightly. If, on the contrary, there are injuries caused by insects, birds, worms or attacks by other fungi, Botrytis develops rapidly in this environment as a favorable pathogen. In this way, the concentration of sugars and acidity are strongly reduced.

Regarding the release of VOCs, Lemos et al. (2016) [83] isolated S. bacillaris species from the fermenting musts of overripe dry grapes (variety Raboso Piave). This variety was selected since the aging of the skin makes them more susceptible to infections caused by fungal pathogens, such as B. cinerea. In vitro tests indicated that the VOC production was primarily responsible for the antifungal effects exhibited by S. bacillaris. Then, in 2018, Kasfi et al. [84] isolated epiphytic microorganisms from the variety “Thompson seedless” in order to identify those that exerted biocontrol on B. cinerea. Among all the isolates, five yeast strains showed in vitro the best activity against Botrytis: Three were M. guilliermondii and two were C. membranaefaciens. Some of them inhibited the mycelial growth of the pathogen through VOCs. In 2017, Cordero-Bueso et al. showed a similar phenomenon in an A. pullulans yeast strain [49].

4. Conclusions

Pathogenic strains belonging to the genera Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Botrytis are perhaps the most challenging problem for fruit and vegetable crops around the world. These phytopathogenic fungi cause great economic losses every year and are a potential hazard for humans, so their control is essential in both pre-harvest and post-harvest grapes [35,85]. Regarding attempts to obtain an organic alternative to replace chemical pesticides, many studies have been carried out on yeast BCAs in the last few decades. If the efficacy of yeasts is confirmed, further studies will be required to assess the potential risk to human health.

Although epiphytic strains belonging to the genus Saccharomyces tend to be recurrent antagonists of these fungi, their efficacy as BCAs is frequently inferior to that of other non-Saccharomyces yeasts and synthetic fungicides. The non-Saccharomyces genera constitute a great variety of species that have shown effective antagonistic capacity against pathogenic fungi on grapes. Some studies have shown the possibility of further enhancing its action by combining it with other substances or organisms. Moreover, endophytic yeasts could soon become a resource in terms of BCAs. In fact, the genera Metschnikowia, Pichia, and Hanseniaspora have recently been detected in grapes [28,86].

The action of pathogenic mold antagonists in the in vitro experiments on postharvest grapes differs from the action that they exhibit in vivo. This highlights the importance of carrying out experiments under field conditions before marketing a product, as well as the suitability of evaluating different strains on grape berries to screen and determine their potential toxicity or find which ones are most effective against a pathogen. The difficulty in developing a commercial formulation is also accentuated by the many parameters that must be considered.

Regarding the type of grape used, the number of studies assessing the performance of BCAs on table grapes is considerably higher than the number of studies assessing their performance on wine grapes and raisins. In some of these, the microbiota of wine grapes was isolated to evaluate the activity of these possible antagonists on table grapes. Therefore, if the results were positive, it could be deduced that these BCAs would also demonstrate activity in wine grapes, although in vivo studies would be necessary to confirm this. On the other hand, the action of B. cinerea is not always negative, since under certain circumstances it can cause “noble putrefaction” on raisins, increasing the concentration of sugars and allowing the production of sweet wines such as “Vino Santo Trentino” or the Tokaj wines. Finally, since the interplay between pathogen, antagonist, and environment is highly complex, understanding the mechanisms and conditions at the root of the BCA action will enhance the effectiveness of future decisions made regarding biocontrol strategies.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Description of the mechanisms of action of potential biological control agents. ND: Not done; +: Biocontrol activity; -: Not biocontrol activity.

| Genus | Species | Control Agents | Mechanism of Action | References | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living Cells | Metabolite | ||||||||||

| Competition for Substrate | Competition for Iron | Killer Factor | Biofilm | VOCs | BCAs | Resistance Induction | Enzymatic Activity | ||||

| Aspergillus | A. carbonarius | P. kluyveri | + | - | - | + | - | ND | - | + | [49] |

| H. uvarum | + | - | - | - | - | ND | - | - | [49] | ||

| M. guilliermondii | + | - | - | - | + | ND | - | + | [49] | ||

| H. clermontiae | + | - | - | - | - | ND | - | + | [49] | ||

| Cyberlindnera jadinii | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | [50] | ||

| C. friedrichii | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | [50] | ||

| C. intermedia | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | [50,51] | ||

| L. thermotolerans | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | [50] | ||

| S. cerevisiae | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [53,54] | ||

| A. niger | D. hansenii | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | [46] | |

| A. ochraceus | Cyberlindnera jadinii | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | [50] | |

| C. friedrichii | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | [50] | ||

| C. intermedia | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | [50] | ||

| L. thermotolerans | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | [50] | ||

| A. japonicas | S. cerevisiae | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | |

| W. anomalus | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R. fluviale | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R. paludigenum | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| A. uvarum | S. cerevisae | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | |

| W. anomalus | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R. fluviale | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R. paludigenum | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| A. aculeatus | S. cerevisiae | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | |

| W. anomalus | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R.fluviale | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R. paludigenum | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| Penicillium | P. expansum | P. kluyveri | + | + | - | + | - | ND | - | + | [49] |

| H. uvarum | + | - | - | - | - | ND | - | - | [49] | ||

| M. guilliermondii | + | - | - | - | + | ND | - | + | [49] | ||

| H. clermontiae | + | - | - | - | - | ND | - | + | [49] | ||

| Candida sake | - | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | [57] | ||

| Starmerella BCAillaris | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | [60] | ||

| W. anomalus | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | + | + | [49,52] | ||

| S.cerevisiae | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R.fluviale | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R. paludigenum | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | + | [52,61] | ||

| P. carribica + Vitamin C | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | + | [51] | ||

| P. digitatum | W. anomalus | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [62] | |

| M. fructicola | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | + | [50] | ||

| P. georgiense | S. cerevisiae | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | |

| W. anomalus | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R. fluviale | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [52] | ||

| R. paludigenum | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | + | [52] | ||

| P. rubens | Y. lipolytica | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | [49] | |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, A.D.C. and M.A.M.-V.; resources, M.M.; data curation, I.V., G.C.-B., A.D.C. and M.A.M.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.C., M.A.M.-V. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, I.V., G.C.-B., R.F. and J.C.; supervision, I.V. and G.C.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Molina-Espeja P. Next Generation Winemakers: Genetic Engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Trendy Challenges. Bioengineering. 2020;7:128. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering7040128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kręgiel D., Pawlikowska E., Antolak H. Non-Conventional Yeasts in Fermentation Processes: Potentialities and Limitations. IntechOpen; London, UK: 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendland J. Special Issue: Non-Conventional Yeasts: Genomics and Biotechnology. Microorganisms. 2020;8:21. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith H.S. On some phases of insect control by the biological method. J. Econ. Entomol. 1919;12:288–292. doi: 10.1093/jee/12.4.288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker K.F., Cook R.J. Biological Control of Plant Pathogens. W.H. Freeman and Company; San Francisco, CA, USA: 1974. p. 433. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson C.L., Wisniewski M.E. Biological Control of Postharvest Diseases of Fruits and Vegetables: An Emerging Technology. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1989;27:425–441. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.27.090189.002233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma R.R., Singh D., Singh R. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables by microbial antagonists: A review. Biol. Control. 2009;50:205e221. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ab Rahman S.F.S., Singh E., Pieterse C.M., Schenk P.M. Emerging microbial biocontrol strategies for plant pathogens. Plant Sci. 2018;267:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X., Li B., Zhang Z., Chen Y., Tian S. Antagonistic Yeasts: A Promising Alternative to Chemical Fungicides for Controlling Postharvest Decay of Fruit. J. Fungi. 2020;6:158. doi: 10.3390/jof6030158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez-Navarro C., González-Muñoz M.T., Jimenez-Lopez C., Rodriguez-Gallego M. Bioprotection. In: Finkl C.W., editor. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2011. pp. 185–189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biocontrol-Dictionary Agroecology. [(accessed on 2 February 2021)]; Available online: https://dicoagroecologie.fr/en/encyclopedia/biocontrol/

- 12.Droby S., Wisniewski M., Macarisin D., Wilson C. Twenty years of postharvest biocontrol research: Is it time for a new paradigm? Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2009;52:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pusey P.L., Wilson C.L. Postharvest Biological Control of Stone Fruit Brown Rot by Bacillus subtilis. Number 4,764,371. US Patent. 1988 Aug 16;

- 14.Pusey P.L. Preharvest Peaches, Postharvest Apples and Postharvest Grapes Are Coated with Bacillus Subtilis B-3 to Inhibit Growth of Brown Rot, Gray Mold Rot and Bitter Rot. No. 5,047,239. U.S. Patent. 1991 Sep 10;

- 15.Shanmuganathan N. Yeasts as a Biocontrol for Microbial Diseases of Fruit. No. 5,525,132. U.S. Patent. 1996 Jun 11;

- 16.Wilson C.L., Wisniewski M.E., Chalutz E. Biological Control of Diseases of Harvested Agricultural Commodities Using Strains of the Yeast Candida oleophila. No. 5,741,699. U.S. Patent. 1998

- 17.Droby S. Yeast NRRL Y-30752 for Inhibiting Deleterious Microorganisms on Plants. No. 6,994,849. U.S. Patent. 2006 Feb 7;

- 18.Massart S., Martinez-Medina M., Jijakli M.H. Biological control in the microbiome era: Challenges and opportunities. Biol. Control. 2015;89:108. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2015.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan Y., Gao L., Chang P., Zhi L. Endophytic fungal community in grape is correlated to foliar age and domestication. Ann. Microbiol. 2020;70:30. doi: 10.1186/s13213-020-01574-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva-Valderrama I., Toapanta D., Miccono M.A., Lolas M., Díaz G.A., Cantu D., Castro A. Biocontrol Potential of Grapevine Endophytic and Rhizospheric Fungi against Trunk Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2021;11:614620. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.614620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuldau G., BCAon C. Clavicipitaceous endophytes: Their ability to enhance resistance of grasses to multiple stresses. Biol. Control. 2008;46:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baltruschat H., Fodor J., Harrach B.D., Niemczyk E., Barna B., Gullner G., Janeczko A., Kogel K.H., Schäfer P., Schwarczinger I., et al. Salt tolerance of barley induced by the root endophyte Piriformospora indica is associated with a strong increase in antioxidants. New Phytol. 2008;180:501–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherameti I., Tripathi S., Varma A., Oelmüller R. The root-colonizing endophyte Pirifomospora indica confers drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by stimulating the expression of drought stress-related genes in leaves. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2008;21:799–807. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-6-0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain P., Pundir R.K. Potential Role of Endophytes in Sustainable Agriculture-Recent Developments and Future Prospects. In: Maheshwari D., editor. Endophytes: Biology and Biotechnology. Sustainable Development and Biodiversity. Volume 15. Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larran S., Simón M.R., Moreno M.V., Santamarina Siurana M.P., Perelló A. Endophytes from wheat as biocontrol agents against tan spot disease. Biol. Control. 2016;92:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2015.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang J.F., Tian X.L., Shi M.W., Ran L.X. Identification of endophytes with biocontrol potential from Ziziphus jujuba and its inhibition effects on Alternaria alternata, the pathogen of jujube shrunken-fruit disease. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haidar R., Roudet J., Bonnard O., Dufour M.C., Corio-Costet M.F., Fert M., Gautier T., Deschamps A., Fermaud M. Screening and modes of action of antagonistic Bacteria to control the fungal pathogen Phaeomoniella chlamydospore involved in grapevine trunk diseases. Microbiol. Res. 2016;192:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall M.E., Wilcox W.F. Identification and Frequencies of Endophytic Microbes within Healthy Grape Berries. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2019;70:212–219. doi: 10.5344/ajev.2018.18033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghanbarzadeh B., Ahari A.B., Sampaio J.P., Arzanlou M. Biodiversity of epiphytic and endophytic yeasts on grape berries in Iran. Nova Hedwig. 2020;110:137–156. doi: 10.1127/nova_hedwigia/2020/0569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baghban R., Farajnia S., Rajabibazl M., Ghasemi Y., Mafi A., Hoseinpoor R., Rahbarnia L., Aria M. Yeast Expression Systems: Overview and Recent Advances. Mol. Biotechnol. 2019;61:365–384. doi: 10.1007/s12033-019-00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsitsigiannis D.I., Dimakopoulou M., Antoniou P.P., Tjamos E.C. Biological control strategies of mycotoxigenic fungi and associated mycotoxins in Mediterranean basin crops. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2012;51:158–174. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poveda J., Barquero M., González-Andrés F. Insight into the Microbiological Control Strategies against Botrytis cinerea Using Systemic Plant Resistance Activation. Agronomy. 2020;10:1822. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10111822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Simone N., Pace B., Grieco F., Chimienti M., Tyibilika V., Santoro V., Capozzi V., Colelli G., Spano G., Russo P. Botrytis cinerea and Table Grapes: A Review of the Main Physical, Chemical, and Bio-Based Control Treatments in Post-Harvest. Foods. 2020;9:1138. doi: 10.3390/foods9091138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spadaro D., Droby S. Development of biocontrol products for postharvest diseases of fruit: The importance of elucidating the mechanisms of action of yeast antagonists. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016;47:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freimoser F.M., Rueda-Mejia M.P., Tilocca B., Migheli Q. Biocontrol yeasts: Mechanisms and applications. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019;35:154. doi: 10.1007/s11274-019-2728-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Francesco A., Martini C., Mari M. Biological control of postharvest diseases by microbial antagonists: How many mechanisms of action? Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016;145:711–717. doi: 10.1007/s10658-016-0867-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang M., Zhao L., Zhang X., Dhanasekaran S., Abdelhai M.H., Yang Q., Jiang Z., Zhang H. Study on biocontrol of postharvest decay of table grapes caused by Penicillium rubens and the possible resistance mechanisms by Yarrowia lipolytica. Biol. Control. 2019;130:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2018.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pretscher J., Tilman F., Branscheidt S., Jäger L., Kahl S., Schlander M., Thines E., Claus H. Yeasts from Different Habitats and Their Potential as Biocontrol Agents. Fermentation. 2018;4:31. doi: 10.3390/fermentation4020031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nally M.C., Pesce V.M., Maturano Y.P., Toro M.E., Combina M., Castellanos de Figuero L.I., Vazquez F. Biocontrol of fungi isolated from sour rot infected table grapes by Saccharomyces and other yeast species. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013;86:456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.07.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batta Y. Postharvest control of soft-rot fungi on grape berries by fungicidal treatment and Trichoderma. J. Appl. Hortic. Lucknow. 2006;8:29–32. doi: 10.37855/jah.2006.v08i01.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mewa-Ngongang M., du Plessis H.W., Ntwampe S.K.O., Chidi B.S., Hutchinson U.F., Mekuto L., Jolly N.P. The Use of Candida pyralidae and Pichia kluyveri to Control Spoilage Microorganisms of Raw Fruits Used for Beverage Production. Foods. 2019;8:454. doi: 10.3390/foods8100454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evangelista-Martínez Z., Contreras-Leal E.A., Corona-Pedraza L.F., Gastélum-Martínez E. Biocontrol potential of Streptomyces sp. CACIS-1.5CA against phytopathogenic fungi causing postharvest fruit diseases. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2020;30:117. doi: 10.1186/s41938-020-00319-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan Q., Tian S.P. Postharvest biological control of Rhizopus rot of nectarine fruits by Pichia membranefaciens. Plant Dis. 2000;84:1212–1216. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.11.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McLaughline R.J., Wilson C.L., Droby S., Ben-Arie R., Chalutz E. Biological control of postharvest diseases of grape, peach and apple with yeasts Kloeckera apiculata and Candida guilliermondii. Plant Dis. 1992;76:470–473. doi: 10.1094/PD-76-0470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts R.G. Biological control of Mucor rot of pear by Cryptococcus laurentii, C. flavus and C. albicus. Phytopathology. 1990;80:1051. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lima G., Ippolito A., Nigro F., Salerno M. Effectiveness of Aureobasidium pullulans and Candida oleophila against postharvest strawberry rots. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1997;10:169–17845. doi: 10.1016/S0925-5214(96)01302-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corbaci C., Ucar F.B. Purification, characterization and in vivo biocontrol efficiency of killer toxins from Debaryomyces hansenii strains. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;119:1077–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.07.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ponsone M.L., Chiotta M.L., Palazzini J.M., Combina M., Chulze S. Control of Ochratoxin A Production in Grapes. Toxins. 2012;4:364–372. doi: 10.3390/toxins4050364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Q., Wang J., Zhang H., Li C., Zhang X. Ochratoxin A is degraded by Yarrowia lipolytica and generates non-toxic degradation products. World Mycotoxin J. 2016;9:1–10. doi: 10.3920/WMJ2015.1911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cordero-Bueso G., Mangieri N., Maghradze D., Foschino R., Valdetara F., Cantoral J.M., Vigentini I. Wild Grape-Associated Yeasts as Promising Biocontrol Agents against Vitis vinifera Fungal Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2025. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Farbo M.G., Urgeghe P.P., Fiori S., Marcello A., Oggiano S., Balmas V., Hassan Z.U., Jaoua S., Mighelia Q. Effect of yeast volatile organic compounds on ochratoxin A-producing Aspergillus carbonarius and A. ochraceus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018;284:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tilocca B., Balmas V., Hassan Z.U., Jaoua S., Migheli Q. A proteomic investigation of Aspergillus carbonarius exposed to yeast volatilome or to its major component 2-phenylethanol reveals major shifts in fungal metabolism. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019;306:108265. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.108265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Solairaj D., Legrand N.N.G., Yang Q., Zhang H. Isolation of pathogenic fungi causing postharvest decay in table grapes and in vivo biocontrol activity of selected yeasts against them. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020;110:101478. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2020.101478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tryfinopoulou P., Fengou L., Panagou E.Z. Influence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Rhotodorula mucilaginosa on the growth and ochratoxin A production of Aspergillus carbonarius. LWT. 2019;105:66–78. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.01.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tryfinopoulou P., Chourdaki A., Nychas G.E., Panagou E.Z. Competitive yeast action against Aspergillus carbonarius growth and ochratoxin A production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020;317:108460. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.108460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fornes F., Almela V., Abad M., Agust M. Low concentrations of chitosan coating reduce water spot incidence and delay peel pigmentation of Clementine mandarin fruit. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005;85:1105–1112. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Camili E., Benato E., Pascholati S., Cia P. Fumigation of ‘Italia’ grape with acetic acid for postharvest control of Botrytis cinerea. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2010;32:436–443. doi: 10.1590/S0100-29452010005000053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arrarte E., Garmendia G., Rossini C., Wisniewski M., Vero S. Volatile organic compounds produced by Antarctic strains of Candida sake play a role in the control of postharvest pathogens of apples. Biol. Control. 2017;109:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2017.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parafati L., Cirvilleri G., Restuccia C., Wisniewski M. Potential Role of Exoglucanase Genes (WaEXG1 and WaEXG2) in the Biocontrol Activity of Wickerhamomyces anomalus. Microb. Ecol. 2017;73:876–884. doi: 10.1007/s00248-016-0887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nadai C., Fernandes Lemos W.J., Jr., Favaron F., Giacomini A., Corich V. Biocontrol activity of Starmerella BCAillaris yeast against blue mold disease on apple fruit and its effect on cider fermentation. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Q., Zhao L., Li Z., Li C., Li B., Gu X., Zhang X., Zhang H. Screening and identification of an antagonistic yeast controlling postharvest blue mold decay of pears and the possible mechanisms involved. Biol. Control. 2019;133:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Piombo E., Sela N., Wisniewski M., Hoffmann M., Gullino M.L., Allard M.W., Levin E., Spadaro D., Droby S. Genome Sequence, Assembly and Characterization of Two Metschnikowia fructicola Strains Used as Biocontrol Agents of Postharvest Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:593. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun C., Fu D., Lu H., Zhang J., Zheng X., Yu T. Autoclaved yeast enhances the resistance against Penicillium expansum in postharvest pear fruit and its possible mechanisms of action. Biol. Control. 2018;119:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2018.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Q., Diao J., Solairaj D., Legrand N.N.G., Zhang H. Investigating possible mechanisms of Pichia caribbica induced with ascorbic acid against postharvest blue mold of apples. Biol. Control. 2020;141:104–129. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johnston P.R., Seifert K.A., Stone J.K., Rossman A.Y., Marvanová L. Recommendations on generic names competing for use in Leotiomycetes (Ascomycota) IMA Fungus. 2014;5:91–120. doi: 10.5598/imafungus.2014.05.01.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Santos A., Sánchez A., Marquina D. Yeast as biological agents to control Botrytis cinerea. Microbiol. Res. 2004;159:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dalmais B., Schumacher J., Moraga J., Le Pêcheur P., Tudzynski B., Collado I.G., Viaud M. The Botrytis cinerea phytotoxin botcinic acid requires two polyketide synthases for production and has a redundant role in virulence with botrydial. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011;12:564–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00692.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pertot I., Giovannini O., Benanchi M., Caffi T., Rossi V., Mugnai L. Combining biocontrol agents with different mechanisms of action in a strategy to control Botrytis cinerea on grapevine. Crop Prot. 2017;97:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2017.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lima G., De Curtis F., Castoria R., De Cicco V. Activity of the yeast Cryptococcus laurentii and Rhodotorula glutinis against post-harvest rots on different fruits. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 1998;8:257–267. doi: 10.1080/09583159830324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schena L., Ippolito A., Zahavi T., Cohen L., Droby S. Molecular approaches to assist the screening and monitoring of postharvest biocontrol yeasts. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2000;106:681–691. doi: 10.1023/A:1008716018490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kurtzman C.P., Droby S. Metschnikowia fructicola, a new ascosporic yeast with potential for biocontrol of postharvest fruit rots. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;24:395–399. doi: 10.1078/0723-2020-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Masih E.I., Slezack-Deschaumes S., Marmaras I., Barka E.A., Vernet G., Charpentier C., Adholeya A., Paul B. Characterisation of the yeast Pichia membranifaciens and its possible use in the biological control of Botrytis cinerea, causing the grey mould disease of grapevine. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001;202:227–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Masih E.I., Paul B. Secretion of beta-1,3-glucanases by the yeast Pichia membranifaciens and its possible role in the biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea causing grey mold disease of the grapevine. Curr. Microbiol. 2002;44:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s00284-001-0011-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parafati L., Vitale A., Restuccia C., Cirvilleri G. Biocontrol ability and action mechanism of food-isolated yeast strains against Botrytis cinerea causing post-harvest bunch rot of table grape. Food Microbiol. 2015;47:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saravanakumar D., Ciayorella A., Spadaro D., Garibaldi A., Gullino M.L. Metschnikowia pulcherrima strain MACH1 outcompetes Botrytis cinerea, Alternaria alternata and Penicillium expansum in apples through iron depletion. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2008;49:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sipiczki M. Metschnikowia pulcherrima and Related Pulcherrimin-Producing Yeasts: Fuzzy Species Boundaries and Complex Antimicrobial Antagonism. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1029. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8071029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Long C.A., Wu Z., Deng B.X. Biological control of Penicillium italicum of Citrus and Botrytis cinerea of Grape by Strain 34-9 of Kloeckera apiculata. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2005;221:197–201. doi: 10.1007/s00217-005-1199-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu H.M., Guo J.H., Cheng Y.J., Liu P., Long C.A., Deng B.X. Inhibitory activity of tea polyphenol and Hanseniaspora uvarum against Botrytis cinerea infections. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;51:258–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guzzon R., Franciosi E., Larcher R. A new resource from traditional wines: Characterization of the microbiota of “vino santo” grapes as a biocontrol agent against Botrytis cinerea. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2014;239:117–126. doi: 10.1007/s00217-014-2195-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sipiczki M. Overwintering of vineyard yeasts: Survival of interacting yeast communities in grapes mummified on vines. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:212. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang X., Glawe D.A., Kramer E., Weller D., Okubara P.A. Biological control of botrytis cinerea: Interactions with native vineyard yeasts from Washington State. Phytopathology. 2018;108:691–701. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-17-0306-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carmichael P.C., Siyoum N., Chidamba L., Korsten L. Exploring the microbial communities associated with Botrytis cinerea during berry development in table grape with emphasis on potential biocontrol yeasts. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019;154:919–930. doi: 10.1007/s10658-019-01710-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ribereau-Gayon J. Les modalités de l’action de Botrytis cinerea sur la baie du raisin. OENO ONE. 1970;4:255–259. doi: 10.20870/oeno-one.1970.4.2.1991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lemos Junior W.J.F., Bovo B., Nadai C., Crosato G., Carlot M., Favaron F., Giacomini A., Corich V. Biocontrol Ability and Action Mechanism of Starmerella BCAillaris (Synonym Candida zemplinina) Isolated from Wine Musts against Gray Mold Disease Agent Botrytis cinerea on Grape and Their Effects on Alcoholic Fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1499. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kasfi K., Taheri P., Jafarpour B., Tarighi S. Identification of epiphytic yeasts and Bacteria with potential for biocontrol of grey mold disease on table grapes caused by Botrytis cinerea. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2018;16:e1002. doi: 10.5424/sjar/2018161-11378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Abdallah M.F., Ameye M., De Saeger S., Audenaert K., Haesaert G. Biological Control of Mycotoxigenic Fungi and Their Toxins: An Update for the Pre-Harvest Approach. IntechOpen; London, UK: 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]