Significance

Broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) can prevent new HIV-1 infections, but most are insufficiently broad or potent to protect from the diverse pool of circulating viruses. V2-glycan/apex bNAbs are exceptionally potent, but their breadth is limited. Their neutralizing activity requires tyrosine sulfation, a posttranslational modification that precludes their improvement with phage or yeast display. Here, we demonstrate the utility of a mammalian display approach whereby the heavy- and light-chain loci of a B cell line are CRISPR edited to encode the apex bNAb CAP256-VRC26.25. These loci were iteratively diversified through homology-directed repair with a library of DNA templates and through in vitro somatic hypermutation and selected with diverse envelope glycoprotein trimers. This approach can identify broader and more-potent apex bNAbs.

Keywords: B cell display, affinity maturation, V2-glycan bNAbs, tyrosine sulfation, CAP256-VRC26.25

Abstract

Three variable 2 (V2) loops of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (Env) trimer converge at the Env apex to form the epitope of an important classes of HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs). These V2-glycan/apex antibodies are exceptionally potent but less broad (∼60 to 75%) than many other bNAbs. Their CDRH3 regions are typically long, acidic, and tyrosine sulfated. Tyrosine sulfation complicates efforts to improve these antibodies through techniques such as phage or yeast display. To improve the breadth of CAP256-VRC26.25 (VRC26.25), a very potent apex antibody, we adapted and extended a B cell display approach. Specifically, we used CRISPR/Cas12a to introduce VRC26.25 heavy- and light-chain genes into their respective loci in a B cell line, ensuring that each cell expresses a single VRC26.25 variant. We then diversified these loci through activation-induced cytidine deaminase–mediated hypermutation and homology-directed repair using randomized CDRH3 sequences as templates. Iterative sorting with soluble Env trimers and further randomization selected VRC26.25 variants with successively improving affinities. Three mutations in the CDRH3 region largely accounted for this improved affinity, and VRC26.25 modified with these mutations exhibited greater breadth and potency than the original antibody. Our data describe a broader and more-potent form of VRC26.25 as well as an approach useful for improving the breadth and potency of antibodies with functionally important posttranslational modifications.

Recent large-scale human clinical studies of the CD4-binding site bNAb VRC01 (1, 2) have highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of antibody-mediated prophylaxis for HIV-1. First, they show that antibodies can protect from challenges with neutralization-sensitive viral variants, if present at sufficient concentrations, consistent with many studies in nonhuman primates (3). Second, they imply that humans are frequently exposed to viral swarms that are diverse enough to include resistant viruses. Thus the ability of an antibody to efficiently neutralize 90% of isolates does not imply that it will protect from 90% of exposures. Third, they highlight the difference between standard cell-culture neutralization assays and in vivo challenge studies, so that 80% of potential infections may be prevented with concentrations of bNAbs that can be substantially higher than their reported IC80 (80% inhibitory concentration) values. Collectively these studies imply that useful antibody-mediated prophylaxis will require bNAbs or bNAb mixtures that are broader and more potent than those currently available.

There are a number of approaches for developing very broad and potent antibodies. One approach is to start with exceptionally potent antibodies and enhance their breadth. In this context, antibodies that recognize the apex of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (Env) trimer are especially attractive because, although they have more-limited breadth, they are 10- or 100-fold more potent than bNAbs of other classes (4–7). These V2-glycan/apex bNAbs are so potent, in part, because a single antibody can inactivate the Env trimer, whereas more than one CD4-binding site or V3-glycan bNAb may be required to maximally neutralize the same trimer (8). These antibodies have other unusual properties. For example, their CDRH3 regions are unusually long, acidic, and tyrosine sulfated, and binding to Env is more dependent on this CDRH3 region. The highly polarizable CDRH3 sulfotyrosines, often buried in a cavity formed at the Env apex, can themselves contribute substantial binding energy (8–10). However, the presence and importance of tyrosine sulfation complicates efforts to use standard phage- and yeast-based approaches to improve these bNAbs because sulfotransferases in bacteria and yeast have specificities distinct from those in humans. Fortunately, the large library sizes that these approaches afford are not necessary to the task of improving an already potent antibody, and thus mammalian cell display approaches are appropriate to the goal of broadening apex antibodies.

Cell-based selection strategies require that a single library member is associated with each cell. CRISPR-mediated editing of the B cell receptor (BCR) genes solves this problem in a straightforward manner because only one BCR is expressed on each cell (11). In addition, the heavy- and light-chain loci are susceptible to modification with activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) (12), an enzyme that mediates somatic hypermutation (SHM) of BCR in vivo. Here, we investigated the utility of a mammalian cell-based selection approach in which a B cell line was edited using CRISPR/Cas12a to express the heavy and light chains of the V2-glycan/apex bNAb CAP256-VRC26.25 (VRC26.25). VRC26.25 is more potent than most other apex bNAbs (13) and, unlike other apex antibodies, it neutralizes virus produced from primary T cells as efficiently as from a HEK293T cell line (14), suggesting this potency could be more relevant in vivo. VRC26.25 genes edited into their respective loci were then diversified by introduction of a highly active AID molecule, and through homology-directed repair (HDR) using several sets of randomized DNA templates. The resulting BCR library was then iteratively selected with soluble HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (SOSIP) trimers derived from several diverse isolates, including those resistant to VRC26.25. This approach enabled identification of several mutations that, when combined, improved the breadth and potency of VRC26.25. Our data show that CRISPR-generated diversification of BCR can be useful to improving an important class of HIV-1 bNAbs.

Results

Development of a B Cell Line Expressing Inferred Germline Forms of VRC26.25.

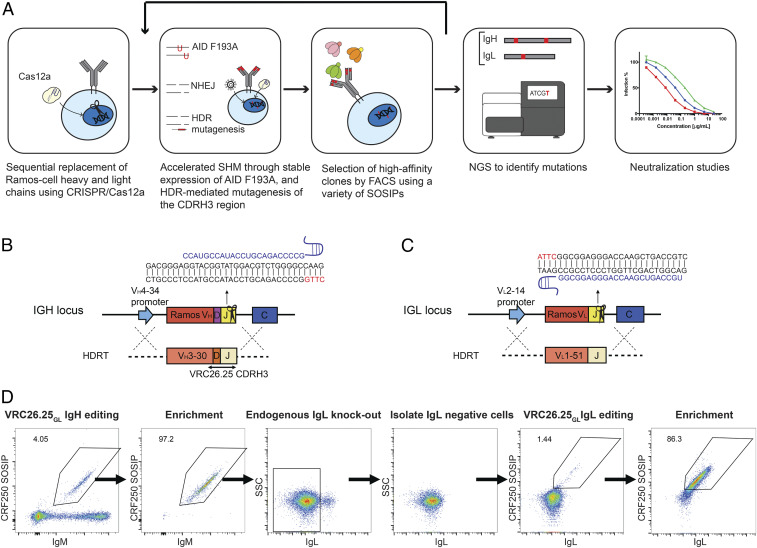

Because the binding activity of VRC26.25 relies on specific tyrosylsulfotransferase present in mammalian cells, we opted to improve this bNAb through a human B cell display approach. Fig.1A represents our overall workflow, in which VRC26.25 heavy- and light-chain genes were introduced into their respective loci of Ramos cells, an AID-active B cell line, facilitating continuous somatic hypermutation of these genes (15, 16). In addition, HDR-mediated introduction of a CDRH3 library increased BCR diversity. Diversified BCRs were then selected by soluble Env (SOSIP) trimers by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and further characterized with neutralization studies. To introduce the VRC26.25 heavy and light chains into Ramos BCRs, we edited the IgH and IgL loci separately by CRISPR/Cas12a (Fig. 1 B and C, respectively). Cas12a is an efficient CRISPR effector that requires single guide RNA (gRNA), and utilizes TTN PAM sequences (17). Ramos cells were electroporated with preassembled Cas12a ribonucleoproteins (RNP) loaded with a gRNA targeting the IGHJ6 gene or the IGLJ2 genes. The efficiency of gRNAs was determined by flow cytometry using loss of BCR expression or though tracking of indels by decomposition assay (18) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). As shown in these figures, gRNA-loaded Cas12a generated indels in at least 82% of cells, indicating that cleavage efficiency would be sufficient to edit these loci with VRC26.25-derived genes using HDR.

Fig. 1.

Introduction of VRC26.25GL heavy- and light-chain genes into Ramos cells. (A) The workflow of these studies is represented. The heavy- and light-chain loci of Ramos cells were edited to encode VRC26.25GL. These loci were then diversified through stable expression of an AID variant (F193A) and through libraries of HDRTs targeting the CDRH3 region. BCRs were iteratively selected with various SOSIP trimers, and the B cell loci of selected cells were deep sequenced after each selection. Enriched mutations were introduced into mature, wild-type VRC26.25, and the resulting bNAb variants were assayed for their ability to neutralize a panel of global HIV-1 isolates. (B) A strategy for replacing the variable region of the Ramos-cell heavy chain. Cas12a recognizing a CTTG PAM region (red) cleaved a region encoded by the JH6 gene. Sequences of the single-stranded Cas12a gRNA and the double-stranded target are shown. The native gene was replaced using an HDRT encoding a 5′ homology arm that complements the V4-34 promoter, followed by the V3-30 leader sequence with intron, the VRC26.25GL heavy-chain variable region, and a 3′ homology arm that complements the intron after JH6, as indicated. (C) Similarly, the Ramos lambda light-chain locus was cleaved in a region encoded by the JL2 gene, and the native light-chain gene was replaced using an HDRT encoding a 5′ homology arm complementing the V2-14 promoter, the V1-51 leader with intron, the VRC26.25GL light-chain, and a 3′ homology arm that complements the intron after JL2. (D) The process of replacing the native Ramos antibody genes with the VRC26.25GL heavy and light chains. The heavy chain was introduced first using the approach shown in panel B. Heavy chain–edited cells were then enriched by FACS using the SOSIP protein based on the CRF250 isolate (CRF250 SOSIP, vertical axis), and an anti-IgM antibody (IgM, horizontal axis). Expression of the native Ramos light-chain was eliminated by NHEJ, and the VRC26.25GL light chain was introduced using the approach shown in panel C, rescuing BCR expression in successfully edited cells. Finally, VRC26.25GL BCR-expressing cells were again enriched by FACS using CRF250 SOSIP and IgL antibodies.

To maximize the scope for improvement of VRC26.25 and in particular its critical CDRH3 region, inferred germline (iGL) forms of the VRC26.25 variable genes were introduced, with the CDRH3 derived from the mature VRC26.25 (19–21). We refer to this construct as VRC26.25GL throughout. Thus, HDR was mediated by single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) HDR templates (HDRTs) encoding the VRC26.25GL heavy- or light-chain variable regions, electroporated with Cas12a RNP. The efficiency of HDR was determined in parallel by flow cytometry with a soluble HIV-1 Env trimer (SOSIP) derived from the CRF250 isolate, followed by next-generation sequencing (NGS). Approximately 4% of cells expressed VRC26.25GL heavy chain–bearing antibodies that were recognized by the CRF250 SOSIP (Fig. 1D). These cells were sorted using the indicated gate for subsequent introduction of the VRC26.25GL light chain. Because BCR composed of the VRC26.25GL heavy chain and the native Ramos-cell light chain already bound SOSIP trimers detectably, we undertook a two-step strategy to replace this native light chain with the VRC26.25GL light chain. First, we eliminated expression of the native Ramos-cell light chain, and second, we rescued BCR expression by introducing the VRC26.25GL light chain at 1.44% frequency into the IgL locus of these VRC26.25GL heavy chain–expressing cells. Heavy and light chain–edited cells were then selected by FACS with CRF250 SOSIPs and IgL antibodies, and binding signals were enriched after sorting (Fig. 1D). RNA was isolated and analyzed by NGS (22, 23). This analysis determined that 90% of cells expressed the VRC26.25GL heavy chain, and 80% of cells expressed the light chain after sorting.

Accelerated BCR Diversification in Ramos Cells.

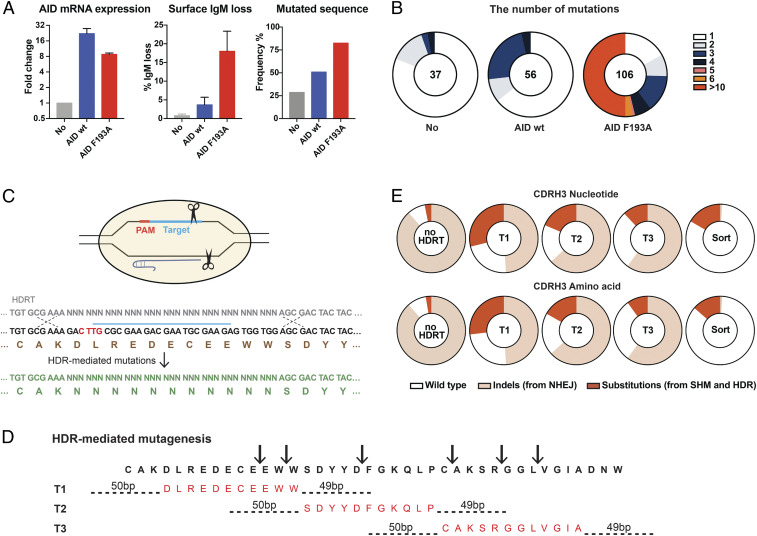

AID, a cytidine deaminase that mediates SHM and class switch recombination, is active in Ramos cells, but the relatively slow rate of SHM in these cells limits BCR diversity (24, 25). To accelerate SHM in these cells, we stably introduced exogenous wild-type AID or previously described AID variant (F193A) into CRISPR-edited Ramos cells. AID F193A has been previously shown to enhance the rate of SHM relative to AID (26). We observed that the total abundance of AID F193A was modestly lower than that observed in cells stably expressing exogenous wild-type AID (Fig. 2A, Left panel) but that the efficiency of SHM in AID F193A cells was significantly higher as determined by loss of surface IgM expression (Fig. 2A, Middle panel) and by NGS analysis (Fig. 2A, Right panel and B). Accordingly, our subsequent studies used VRC26.25GL-edited Ramos cells stably expressing AID F193A.

Fig. 2.

Accelerated BCR diversification in Ramos cells. (A) Ramos cells were transduced with retroviruses expressing AID or an AID variant (F193A). AID expression was measured by qRT-PCR assay 2 wk posttransduction. Expression is shown normalized to the endogenous AID expressed in untransduced cells. The error bars represent SD of triplicates (Left). Cell-surface IgM expression was measured by flow cytometry 2 wk post transduction. The bars represent loss of IgM expression, an indication of AID activity. The error bars represent SD of two independent experiments (Center). The percentage of mutated heavy chain, determined by NGS 1 mo posttransduction, was compared in unmodified Ramos cells, where a baseline level of mutation is observed, and in cells transduced with AID or AID F193A (Right). (B) An analysis of NGS results in which the number of mutations per sequence analyzed is presented. The number of analyzed sequences with >100 UMI are shown in the Center of each chart. (C–E) In addition to AID-mediated mutations, the heavy chains of AID F193A–transduced VRC26.25GL cells were diversified through HDR-mediated randomization, as shown. (C) An example of HDRT-mediated random mutagenesis is presented. After Cas12a-mediated cleavage, soft-randomized HDRT introduced mutations into the VRC26.25 CDRH3. “N” represents 91% original wild-type bases with 3% of each of the other nucleotides. (D) The strategy used to randomize the full VRC26.25 CDRH3 is shown. The CDRH3 region was cleaved at six locations using Cas12a and six distinct gRNAs, as indicated by arrows. One of three HDRTs (T1, T2, and T3), each soft randomized in an 11– or 12–amino acid region (red), was used to edit the cleaved CDRH3 target. HDRT homology arms are indicated by dotted lines. (E) Pie charts represent the proportion of indels and substitutions in the CDRH3 of HDRT-mutated cells, as determined by NGS after one round of editing in AID F193A–transduced VRC26.25GL cells. These cells were electroporated with RNP including all six gRNAs, in the absence (no HDRT) or presence of the indicated HDRT. Cells mutated using HDRT T1, T2, and T3 were combined, sorted with CRF250 SOSIP and an anti-IgL antibody, and again analyzed (sort). Nucleotide (Top) and amino acid (Bottom) changes are shown.

We also took a second approach to accelerate VRC26.25GL diversification by using CRISPR-Cas12a–initiated HDR (27, 28), in this case focused on the CDRH3 region and directed by “soft-randomized” HDRT. That is, HDRTs were generated so that at a given randomized position, most sequences retained the original native nucleotide. Specifically, at each HDRT position represented by an “N” in Fig. 2C, the original nucleotide was introduced 91% of the time, whereas the three alterative nucleotides were introduced at 3% each. This strategy introduces a limited number of mutations per library member and limits catastrophic mutations (29, 30). The VRC26.25 CDRH3 regions of Ramos cells stably expressing AID F193A were modified with three soft-randomized HDRTs, each randomizing 11 to 12 CDRH3 codons, which were introduced with RNP associated with six gRNAs cleaving distinct sites with this region (Fig. 2D). A single round of RNP electroporation with HDRT altered 70 to 82% of CDRH3 sequences analyzed at both nucleotide and amino acid level by NGS (Fig. 2E), with 10 to 30% associated with substitutions derived from SHM or randomized HDRT. More substitutions derived from randomized HDRT (10 to 28% from each HDRT) than from SHM, as determined by control cells electroporated without HDRT (2 to 3%). In addition, in all RNP-electroporated cells, nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) generated insertions or deletions, frequently associated with frame shifts or premature stop codons. Sorting of a mixture of HDRT-randomized cells with a SOSIP antigen eliminated most of these NHEJ-modified cells. These data indicate that HDR-mediated randomization of the VRC26.25GL CDRH3 introduces mutations more efficiently than AID-mediated SHM.

Affinity Maturation In Vitro.

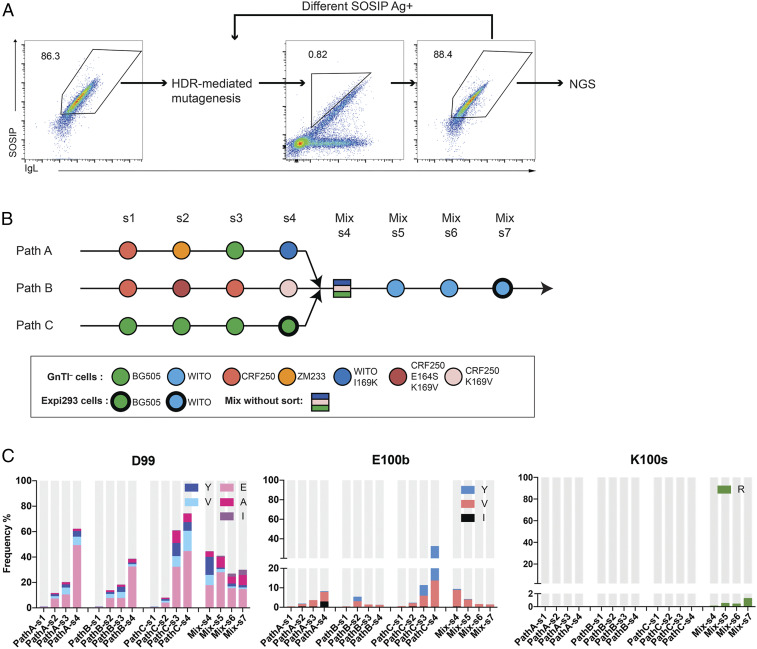

NGS analysis identified ∼1.0 × 105 and 4.2 × 103 distinct heavy- and light-chain open reading frames, respectively, after one round of HDR mutagenesis with soft-randomized templates. Ramos cells expressing these genes were then selected iteratively for their ability to bind diverse SOSIP trimers, HDR-mutated again, and analyzed at each round by NGS (Fig. 3A). AID F193A was present and presumably active throughout the process. As represented in Fig. 3B, high-affinity BCRs were selected with a range of SOSIP variants. BG505.SOSIP.v5.2 I201C-A433C (BG505 SOSIP) has enhanced stability and induced strong antibody responses (31). We therefore generated chimeras based on this SOSIP trimer in which its V1V2 region was replaced with those of the HIV-1 isolates ZM233 and WITO (ZM233 SOSIP and WITO SOSIP, respectively). The CRF250 V1V2 was engineered onto SOSIP.v7 backbone (CRF250 SOSIP) (32, 33) because its binding efficiency was significantly increased compared to the analogous SOSIP.v5 chimera. SOSIP trimers produced in GnTI– cells typically bound VRC26.25GL more efficiently than those produced in Expi293F cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), consistent with previous results reported in Andrabi, et al. (34). We therefore used these trimers to select B cells in the early rounds of selection but completed selection with SOSIP molecules produced in Expi293F cell, capable of complex glycosylation, to better emulate the native Env trimer.

Fig. 3.

Affinity maturation of VRC26.25 in vitro. (A) VRC26.25GL-expressing cells sorted as shown in Fig. 1D (Right panel) were diversified through the introduction of AID F193A and CRISPR-mediated editing in the CDRH3 regions. The top 0.5 to 3% SOSIP-positive IgL-positive cells were selected with a diagonal gating (Center) to reduce biases from high BCR expression. Most sorted cells bound SOSIP trimers efficiently (Right). (B) The selection cycle represented in panel A was repeated seven times for each of three pathways (Path A, B, and C), selecting with distinct sets of SOSIP antigens, as indicated with colored circles. Cells were mutated with soft-randomized HDRT and sorted four times using progressively lower concentrations of fluorescently labeled SOSIP trimers (s1 to s4). Cells were mixed (Mix-s4) and sorted an additional three cycles (Mix s5 to s7) with a SOSIP variant bearing a WITO apex region resistant to VRC26.25 (light blue circles). NGS analysis was performed after each selection step. Circles with thin boundaries represent SOSIP trimers produced from GnTI– cells that lack complex glycans, whereas circles with thick boundaries indicate SOSIP molecules produced from Expi293 cells and decorated with complex glycans. (C) The bars represent the frequency of mutations at the indicated heavy-chain residues as the emerged from sort 1 (s1) to sort 7 (s7). Gray indicates the original wild-type residue.

Using these SOSIP proteins, we selected diversified VRC26.25GL variants through three parallel pathways, anticipating that variants selected through more than one pathway would bind a broader range of HIV-1 Envs. Path A included four diverse SOSIP trimers, each recognized by VRC26.25 with decreasing affinity. This path included a fourth selection with a WITO variant modified with a point mutation (I169K) in the VRC26.25 epitope, which is sufficient to make the WITO Env sensitive to VRC26.25 neutralization. In parallel, Path B selected with variants of the CRF250 SOSIP, in some cases modified in its VRC26.25 epitope with VRC26.25-resistance mutations (E164S and K169V) (8). Path C variants selected repeatedly with the BG505 SOSIP trimer, including a fourth selection using this SOSIP with complex glycosylation. After four rounds of HDR-mediated diversification, selection, and NGS analysis for each pathway, cells were combined and further selected with the WITO SOSIP, fully resistant to VRC26.25, to enrich for broader antibody variants selected in the preceding rounds. Each round of selection in each pathway (s1 to s4) and in the mixtures (s5 to s7) improved binding of the selected cell population to both CRF250- and BG505-based SOSIP trimers, regardless of which SOSIP proteins were used for selection (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C). Binding of these selected populations also exceeded binding observed with cells expressing the mature VRC26.25 heavy chain, further indicating that mutations accumulated in VRC26.25GL improved SOSIP binding.

To identify these affinity-enhancing mutations, RNA of selected cells was isolated after each sort, and heavy and light chain genes were sequenced by NGS. As expected, most mutations were found in the CDRH3 region (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B), indicating that HDR-mediated mutations dominated the diversification of these loci, as observed in Fig. 2E. Fewer mutations were observed in the region near the sulfated YYD motif, presumably because of its critical role in Env association. Mutations in CDRH1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), CDRH2, and in the light chain (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C) were also identified, indicating an active role for AID in BCR diversification. A number of specific changes emerged independently in more than one pathway (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and C), including critical mutations D99E, E100bV, and K100sR (Fig. 3C).

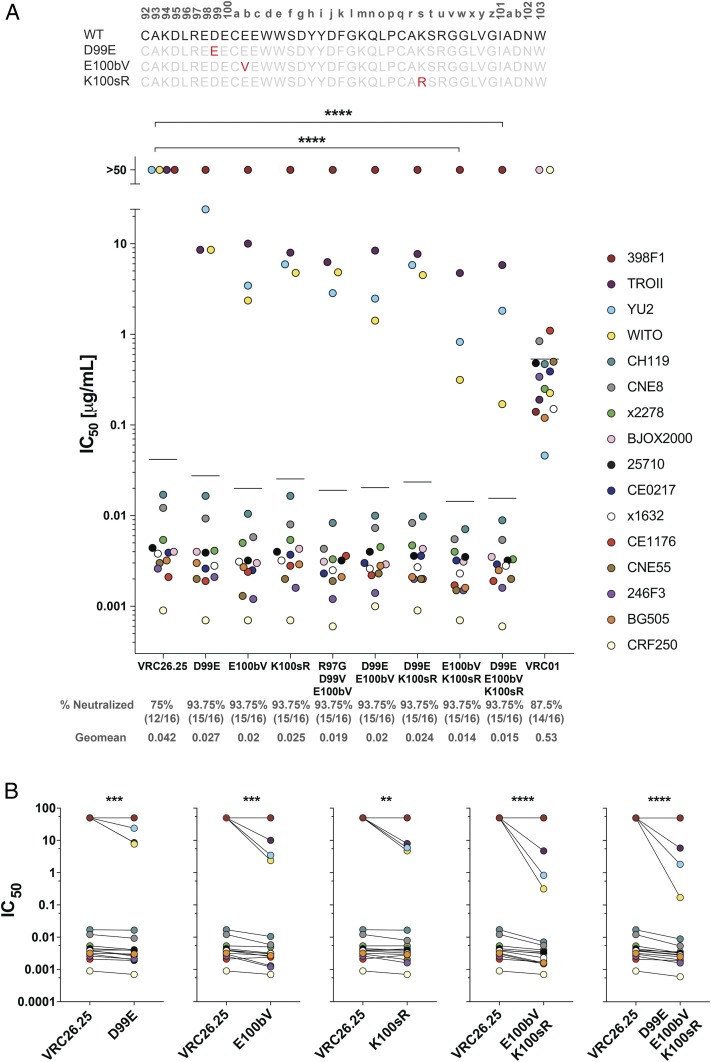

VRC26.25 Variants with Improved Potency and Breadth.

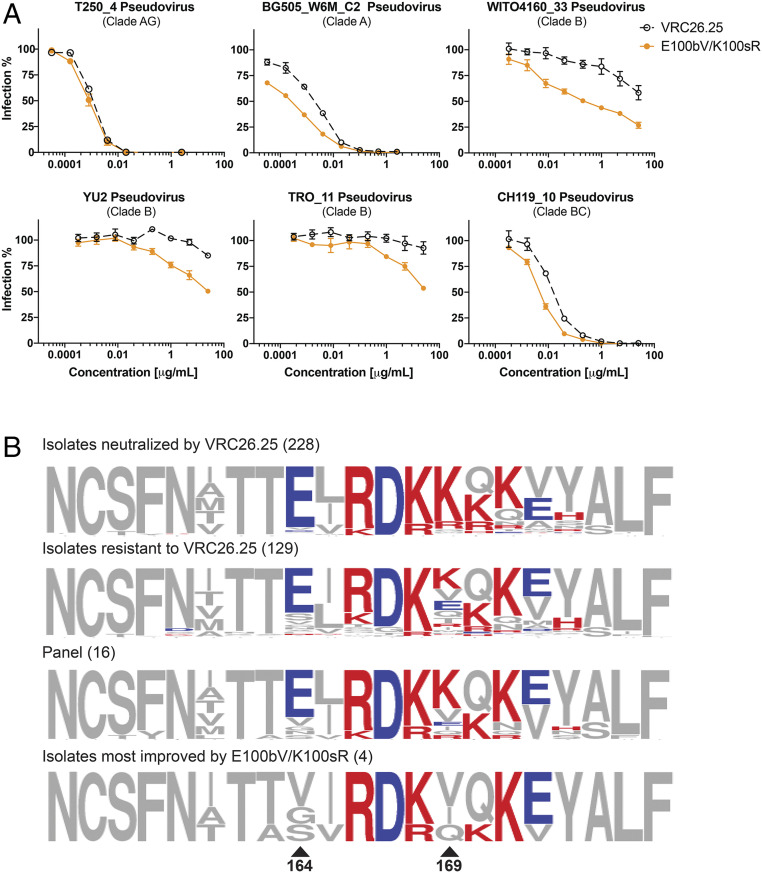

To determine whether the selected mutations could enhance the breadth or potency of mature, wild-type VRC26.25, they were introduced in various combinations into plasmids encoding a soluble form of this antibody. These VRC26.25 variants were then evaluated for their ability to neutralize a standard panel of 12 global isolates (35), as well as three isolates used for selection (CRF250, BG505, and WITO), and an additional VRC26.25-resistant isolate, YU2 (Figs. 4 and 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Three mutations highlighted in Fig. 4A (D99E, E100bV, and K100sR) significantly improved neutralization of WITO, YU2, and TROII and allowed measurement of their IC50 (50% inhibitory concentration) but not IC80 values, with a highest concentration of 25 µg/mL. Note though that TROII and YU2 could not be neutralized to completion. These mutations also improved neutralization of most other isolates tested. In contrast, a number of other mutations, such as D99Y, enhanced neutralization of some isolates but impaired neutralization of others (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Combinations of the more universal mutations further improved neutralization of most isolates, with the E100bV/K100sR combination resulting into the greatest improvement in mean potency compared with wild-type VRC26.25 (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The D99E variant slightly impaired mean potency when added to E100bV/K100sR, although this triple mutation neutralized CRF250 and WITO isolates more efficiently than E100bV/K100sR alone. All variants with E100bV/K100sR were significantly more potent than wild-type VRC26.25 (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The largest neutralization improvements were associated with the Envs lacking glutamic acid at V1V2 residue 164 and/or a lysine at position 169 (Fig. 5B), perhaps reflecting selection with SOSIP variants lacking these residues (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). The absence of these amino acids also predicts VRC26.25 resistance in previous studies of viral escape from VRC26.25 (8, 13) and of serum from CAP256 donor (36).

Fig. 4.

VRC26.25 variants with improved potency and breadth. (A) The amino acid sequence of the wild-type VRC26.25 CDRH3 is shown with Kabat numbering indicated. Key mutations D99E, E100bV, and K100sR (red) are also shown aligned with the wild-type sequence. HIV-1 pseudoviruses of indicated isolates were incubated with the indicated VRC26.25 variant or the CD4-binding site bNAb VRC01 in TZM-bl cells. Measured IC50 values were plotted. Pseudoviruses resistant to the indicated antibody were assigned an IC50 of 50 µg/mL. Each dot represents the mean from two independent experiments of triplicates. A previously defined 12-isolate global panel was evaluated together with four additional isolates, namely CRF250, BG505, YU2, and WITO. Geometric mean values are indicated by horizontal lines, and their numerical values are provided beneath the figure, along with the percent of 16 isolates neutralized by the antibody-indicated variant. (B) IC50 values of the indicated VRC26.25 variant was compared to the IC50 of wild-type VRC26.25 for each of the 16 isolates in the panel. Significance in both panels was determined by a Wilcoxon matched signed rank test: ns, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Fig. 5.

Env determinants of enhanced VRC26.25 potency and breadth. (A) TZM-bl neutralization curves of the most potent VRC26.25 variant against pseudotyped viral isolates whose SOSIPs were used during selection (Top), and those isolates whose neutralization was most improved by these variants (Bottom; note that WITO is in both groups). Errors bars represent SEM of triplicates. (B) The amino acid alignment of susceptible and resistant viruses against VRC26.25 (first and second row), the 16-panel isolates (third row), and those isolates whose neutralization was most improve by the E100bV and K100sR mutations (fourth row) are shown. Two positions critical to viral escape from wild-type VRC26.25 are indicated with triangles. Basic and acidic amino acids were labeled in red and blue, respectively.

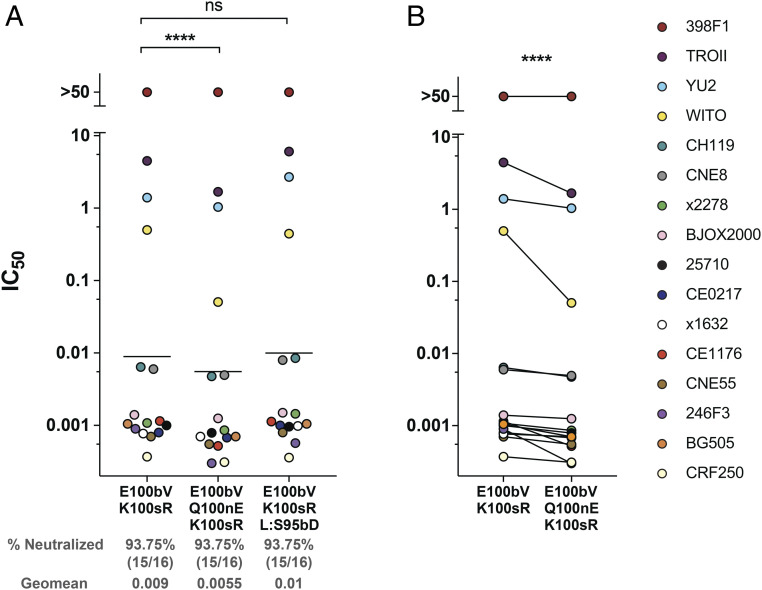

Using E100bV/K100sR as a starting point, we evaluated additional mutations that emerged from the screen, namely heavy-chain Q100nE and light-chain S95bD (Fig. 6). Introduction of Q100nE further improved neutralization of most isolates assayed (Fig. 6 A and B). Q100nE also improved neutralization of viral isolates such as CE1176 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) that were not significantly improved by the E100bV/K100sR combination alone. However, S95bD in the light chain modestly improved neutralization of five isolates and impaired neutralization in several cases (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Collectively, these data show that the triple mutation of E100bV/Q100nE/K100sR significantly improves the breadth and potency of the HIV-1 bNAb VRC26.25.

Fig. 6.

Further improvement of VRC26.25 variants. (A) A figure similar to that in Fig. 4A, except that IC50 values of the indicated modifications of E100bV/K100sR are compared to E100bV/K100sR itself. L preceding a mutation indicates a light-chain residue. Each dot represents the mean from two independent experiments of triplicates. Geometric means were indicated by horizontal lines. (B) A figure similar to that in Fig 4B, except that the E100bV/K100sR variant was compared to E100bV/Q100nE/K100sR variant. Significance was determined by a Wilcoxon matched signed rank test: ns, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

Despite enormous progress in the development of HIV-1 bNAbs, recent clinical trials make clear that further improvements in bNAb breadth and potency will be important to their successful use in humans. V2-glycan/apex antibodies form an especially potent class of bNAbs, and VRC26.25 is an especially potent member of this class. We therefore undertook to expand its breadth, which lags behind that of many other well-characterized bNAbs. However, VRC26.25 and other apex antibodies are posttranslationally modified by addition of sulfate moieties to their CDRH3 regions, complicating their improvement by traditional selection methods. We accordingly extended mammalian selection techniques by using CRISPR to replace an endogenous antibody in a Ramos B cell line with the inferred germline versions of VRC26.25. We began with an iGL form first to promote more rapid improvement of the CDRH3 region and second to explore a wider range of solutions to high-affinity SOSIP binding. Using the fact that B cells express only one BCR allele (11), we bypassed a technical challenge associated with other mammalian display techniques, namely the problem of introducing and selecting a single gene per cell. We then accelerated diversification of these genes using an enhanced AID and multiple rounds of editing using a soft-randomized library of HDRTs. Cells diversified in this manner were selected iteratively with divergent SOSIP proteins, including those derived from isolates resistant to VRC26.25.

This approach builds on many previous efforts to recapitulate somatic hypermutation in vitro in B cells (37–41) or other cells by expression of recombinant AID (42). As reported in these studies, AID-mediated mutation rates are relatively slow in vitro. Similarly, we observed that CRISPR-mediated HDR of a library of templates significantly outpaced the rate of mutation observed with even a hyperactive AID variant (Fig. 2E) and likely contributed to most mutations retained in our lead VRC26.25 variant. Despite these limitations of AID, it is striking that mutations introduced by this enzyme recapitulated a number of similar mutations observed during the natural evolution in the donor CAP256, from whom the VRC26 lineage was isolated (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). These include an S31N/R mutation in the CDRH1, S55T/N, and A60G in CDRH2 and gain of a light-chain glycosylation at position 26 in the majority of lineage members. Thus AID-mediated mutations observed in an iGL form of an antibody selected with SOSIP trimers could help anticipate mutations that can emerge in response to the same antigen in vivo. This approach could thus inform the design of inoculation protocols based on successive administrations of distinct antigen variants.

In contrast to AID, introduction of variants using a library of HDRT appears to be a rapid and effective means of accelerating antibody diversification. This was achieved by cleaving multiple regions in the CDRH3-encoding region in the presence of short soft-randomized single-stranded HDRT, affording control of which nucleotides are mutated and the frequency with which they are mutated. Thus the rate of mutation can be controlled to a level appropriate to size of the library and the selection regime. A key difficulty with this approach, as with all mammalian display approaches, is the library size is relatively smaller than with phage or yeast display. We partially overcome this limitation by CRISPR mutating the same gene multiple times. Although this technique can result in overwriting useful mutations, previously diversified sequences are less likely to be overwritten than unedited regions because, due to mismatches, they are less likely to be recognized by the Cas12a gRNA. We focused in this study on CDRH3 because of its unusual importance to VRC26.25 (8), but future implementations could easily extend editing to other heavy- and light-chain regions.

The utility of this approach is demonstrated through a significant improvement in the breadth and potency of VRC26.25. Specifically, we identified three CDRH3 mutations—E100bV, Q100nE, and K100sR—that combined to improve geometric mean potency of an already very potent antibody by at least threefold and improved neutralization of three of four fully resistant isolates (Figs. 4 and 6). The SOSIP proteins used in our selections were critical to achieving this breadth since they derived from Env proteins that were resistant to VRC26.25, in part because of Env residues 164 and 169 in the VRC26.25 epitope (Fig. 3B). Together, these residues account for ∼70% of isolates resistant to VRC26.25 (8). Residue 164, usually a glutamic acid, is smaller and uncharged in isolates whose neutralization was most improved by the CDRH3 mutations described here. Similarly, neutral residues at Env 169, typically a lysine or arginine, predict both VRC26.25 resistance and the greatest improvement in neutralization with our selected VRC26.25 variants. Thus E100bV/K100sR and E100bV/Q100nE/K100sR rescued neutralization of the WITO, YU2, and TROII isolates, each with neutral residues at positions 164 and 169. In contrast, our improved variants did not rescue the 398F1 isolate with a less common glutamic acid at position 169, perhaps because none of the SOSIP proteins used in selection included this glutamic acid. Further efforts will be necessary to more efficiently neutralize a wider range of resistant isolates. These may include additional selection rounds with divergent SOSIP trimers with more native glycosylation and HDR-mediated diversification of other CDR regions.

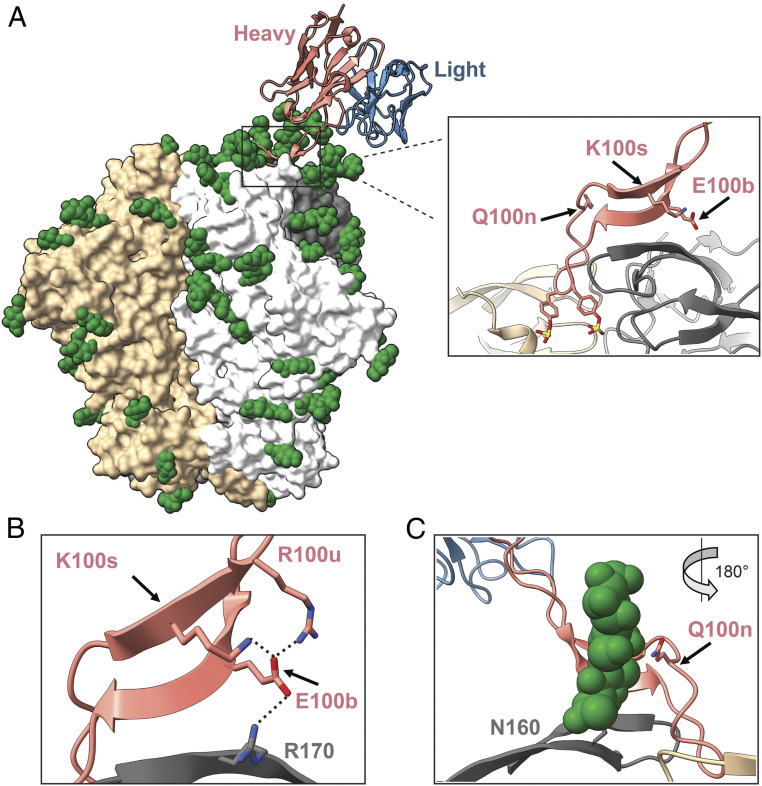

It remains unclear exactly how the CDRH3 residues E100bV, Q100nE, and K100sR (Fig. 7A) improve the potency of VRC26.25 and how they rescue neutralization with variants bearing neutral amino acids at Env residues 164 and 169. E100b is in the center of a network of basic residues comprised of Env K/R 170, adjacent to critical Env escape residue 169, as well as VRC26.25 residues K100s and R100u on the opposite CDRH3 strand (Fig. 7B). Its alteration to valine in E100bV disrupts this network, perhaps enabling residues more proximal to the CDRH3 tip to interact more favorably in the apex cavity. Similarly, replacement of K100s with an arginine also alters this same local network of charge residues, perhaps by facilitating a tighter salt bridge with E100c. Notable the E100bV and K100sR mutations function independently and additively to enhance VRC26.25 neutralization, consistent with an impact on CDRH3 residues positioned more deeply in the apex cavity. Higher-energy binding of the CDRH3 tip to the apex cavity may explain why changes to Env E164 are also accommodated. E164 is outside the cavity, and this residue rather appears to mediate interaction among Env protomers. Its mutation to smaller, uncharged residues may loosen protomer contacts that maintain the apex cavity. A more-optimal VRC26.25 CDRH3 tip could help lock this less-stable apex cavity into its closed conformation. Q100n interacts with the glycan at Env asparagine 160 (Fig. 7C). Q100nE may disrupt this interaction and again facilitate higher affinity binding of the CDRH3 tip to the apex cavity. Alternatively, it could simply enhance binding to this conserved glycan. Further functional and structural studies will help clarify these possibilities and guide further improvements to VRC26.25 breadth and potency.

Fig. 7.

The structure of VRC26.25 in complex with CAP256.wk34.c80 SOSIP (Protein Data Bank: 6VTT). (A) The structure of a VRC26.25 Fab domain complexed with CAP256.wk34.c80 SOSIP trimer. Three SOSIP protomers are represent in gray, white, and tan surfaces, respectively. Green spheres indicate glycans resolved in the structure. The VRC26.25 heavy chain is shown in salmon, and the light chain is shown in blue. Note that the heavy-chain CDRH3 contacts all three Env protomers. Inset presents this CDRH3 with E100b, Q100n, and K100s shown and labeled. Note also the two CDRH3 sulfotyrosines (100h and 100i) that project into the apex cavity. (B) Residue E100b interacts with a network basic of residues including SOSIP R170 (gray) and VRC26.25 CDRH3 residues K100s and R100u. Potential electrostatic contacts are indicated with a dashed line. (C) VRC26.25 residue Q100n contacts a critical glycan at SOSIP N160 (green).

In short, we have extended and demonstrated the utility of B cell display technologies for improving the breadth and potency of posttranslationally modified antibodies less amenable to phage- or yeast display approaches. In doing so, we have identified VRC26.25 variants that may improve the clinical use of this bNAb and developed a platform that can further improve the breadth of the very potent apex class of HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies.

Materials and Methods

ssDNA HDRT Preparation.

The HDRT encoding heavy- and light-chain nucleotide sequences are listed in SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C and D, respectively. To produce extralong ssDNA templates, the DNA fragments were amplified via Guide-it Long ssDNA Production System (Takara, 632644) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Ramos Culture and Electroporation.

Ramos 2G6 cells, a subclone capable of undergoing class switching in vitro (43), were purchased from ATCC (CRL-1923). These cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 GlutaMAX media, with 10 to 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Cell density was kept between 0.5 to 2.0 × 106 cells/mL. Culture medium was changed to medium without penicillin-streptomycin before electroporation. For optimal editing, 4.2 million Ramos were washed with once phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and concentrated into 80 µl electroporation buffer (Lonza, V4XC-3024). For RNP preparation, 4.5 µL 100 µM gRNA, 1.12 µL 250 µM Mb2Cas12a (as described in ref. 44). 2.43 µL PBS, and 1.95 µL 646 mM NaCl were mixed and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 15 min. A total of 16 µg HDRT or 16 µL 100 µM random ssDNA oligo synthesized from Integrated DNA Technologies (as control) were then added and incubated for an additional 1 to 2 min. Cells were mixed with RNP + HDRT and transferred to 100-µL nucleocuvette vessels then electroporated using a Lonza 4D nucleofector CA-137 program according to manufacturer’s instructions. After electroporation, cells were incubated at RT for 10 min before transfer into 6-well plates containing antibiotics-free medium with 20% FBS.

Retrovirus Production and Transduction.

Plasmid-encoding AID, pMSCVgfp::AID, was a gift from Nina Papavasiliou, Laboratory of Lymphocyte Biology, New York (Addgene plasmid No. 15925; http://n2t.net/addgene:15925; RRID: Addgene_15925). The AID F193A mutation was introduced into this plasmid through site-directed mutagenesis (NEB, E0554S). Retroviruses were packaged with retroviral expression system (Takara, 631512). Viruses were concentrated with Retro-X concentrator (Takara, 631455) and stored at −80 °C. For transduction, Ramos cells were cultured in retrovirus-containing media for 24 h, after which the media was exchanged. After an additional 48 h, stable AID-GFP positive cells were selected by FACS.

SOSIP Production and Conjugation.

The constructs of BG505.SOSIP.v5, ZM233.SOSIP.v5, WITO.SOSIP.v5, CRF250.SOSIP.v7, and their variants created by site-directed mutagenesis (NEB, E0554S) were made and transfected into Expi293F cells or Expi293 GnTI− cells. SOSIP constructs, furin, formylglycine-generating enzyme, and protein disulfide isomerase were cotransfected at 4:1:1:1 ratio with FectoPRO. Supernatants were harvested 5 d after transfection, filtered, and purified with PGT145 affinity column. Proteins were eluted with gentle Ag/Ab elution buffer (Thermo, 21027). The elution was exchanged with buffer (10 mM Hepes, 75 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) and concentrated in 30K Amicon Ultra-15 filter tubes. Purified SOSIPs were conjugated with fluorescence by Lightning-Link Antibody Labeling Kits according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow Cytometry and FACS.

Cultured cells were counted to achieve desired cell numbers and washed once with FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FBS, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid). Cells were stained for 20 min on ice with SOSIPs and antibodies in volumes of 100 µL per 1 × 106 cells and washed again with FACS buffer. Cells were gated according to background levels, determined as the binding percentage in unedited cells with the same SOSIP at the same concentration. Single live cells were analyzed on BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer.

For cells for FACS, stained cell was filtered through cell strainer before being loaded on BD FACSAria Fusion at the TSRI FL Flow core. Cells with the highest (0.5 to 3%) signal as sorted with a diagonal gate were retained. Data were analyzed by FlowJo software.

NGS of Ig Messenger RNA.

RNA was isolated from ∼10,000 to 100,000 sorted cells with the RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen, 74004). Heavy-chain complementary DNA synthesis was performed with 8 µL RNA with 10 pmol of primers targeting constant region of IgM and IgG (GTG ATG GAG TCG GGA AGG AAG and GAA GTA GTC CTT GAC CAG GCA) in 20 µL total reaction with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Thermo) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Remaining dNTPs were removed with ExoSAP-IT (Thermo). The entire treated PCR products then were added with 10 pmol VRC26.25GL heavy chain–specific primer and Ramos heavy-chain primer (AGA CGT GTG CTC TTC CGA TCT NNT ACN NNN NNA GTN NNN NNC TGG GAG GTC CCT GAG ACT CTC CTG and AGA CGT GTG CTC TTC CGA TCT NNT ACN NNN NNA GTN NNN NNC TTC GGA GAC CCT GTC CCT CAC CTG) with HotStar Taq plus polymerase. The primers contain unique molecular identifiers (UMI), and Illumina adaptor sequences were incorporated during this round of PCR. Residual primers and dNTPs were removed with ExoSAP-IT treatment, and double-stranded DNA was purified with solid phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads (0.8×). A second round PCR was performed using a 5′ nested primer (GTG ACT GGA GTT CAG ACG TGT GCT CTT CCG ATC) and 3′ UMI containing nested primer mix (IgM: ACA CTC TTT CCC TAC ACG ACG CTC TTC CGA TCT (NN)2-6 GG TTG GGG CGG ATG CAC TCC, IgG: ACA CTC TTT CCC TAC ACG ACG CTC TTC CGA TCT (NN)2-6 SG ATG GGC CCT TGG TGG ARG C) in a 50 µL reaction volume (Q5 hifi, NEB). The PCR products were cleaned with dual-side SPRI selection (0.55×/0.75×). Final products were confirmed on 1% agarose gel and were indexed with NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Dual Index Primers Set 1). Indexed fragments were pooled and sequenced on Illumina Miseq to obtain 2 × 300 base pairs read chemistry.

Light chain preparation is the same as heavy chain, except changed IgL primers below. IgL-RT (GCT CCC GGG TAG AAG T), VRC26.25GL light chain–specific primer and Ramos light-chain primer (AGA CGT GTG CTC TTC CGA TCT NNT ACN NNN NNA GTN NNN NNG GTC CTG GGC CCA GTC TGT GTT G and AGA CGT GTG CTC TTC CGA TCT NNT ACN NNN NNA GTN NNN NNG GTC CTG GGC CCA GTC TGC CCT G), and 3′ UMI containing nested primer mix (IgL: ACA CTC TTT CCC TAC ACG ACG CTC TTC CGA TCT (NN)2-6 GY GGG AAC AGA GTG AC).

Antibody Production and Purification.

Expi293 cells were resuspended at a density of 3 × 106 cells/mL and cotransfected with plasmids encoding heavy chains, light chains, and human tyrosine protein sulfotransferase 2 at 2:2:1 ratio with FectoPRO transfection reagents. At 4 to 6 d post transfection, supernatants were collected, filtered, and purified through HiTrap Mabselect SuRe columns (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Columns were washed and eluted with IgG elution buffer (Thermo, 21004), and pH values were adjusted with neutralization buffer (1M Tris HCl, pH 9.0). The elution was buffer exchanged and concentrated with PBS in 30 K Amicon Ultra-15 filter tubes.

Pseudovirus Production.

HEK293T cells in antibiotics-free medium were cotransfected with the plasmid-expressing Env of desired isolates and pNL4.3∆Env plasmid at 1:1 ratio with PEIpro reagents. After 48 h, supernatants were collected, filtered, and stored at −80 °C.

Neutralization Assay.

TZM-bl neutralization assays were performed as previously described (45). Briefly, titrated antibodies in 96-well plates with tips change were incubated with pseudotyped viruses at 37 °C for 1 h. TZM-bl cells were then added to the virus/inhibitor mix using 10,000 cells/well. Cells were then incubated for 48 h at 37 °C. Viral entry was determined by luciferase readout with BriteLite Plus (PerkinElmer, 6066761) and read on a Victor X3 plate reader (PerkinElmer). IC50 and IC80 values were calculated using a three-parameter nonlinear regression in GraphPad Prism 7.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by NIH Grants U19 AI49656, R21 AI152836, and UM1 AI126621 (M.F.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2106203118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Gilbert P. B., et al., Basis and statistical design of the passive HIV-1 antibody mediated prevention (AMP) test-of-concept efficacy trials. Stat. Commun. Infect. Dis. 9, 20160001 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corey L.et al.; HVTN 704/HPTN 085 and HVTN 703/HPTN 081 Study Teams , Two randomized trials of neutralizing antibodies to prevent HIV-1 acquisition. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1003–1014 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gautam R., et al., A single injection of anti-HIV-1 antibodies protects against repeated SHIV challenges. Nature 533, 105–109 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doria-Rose N. A.et al.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program , Developmental pathway for potent V1V2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature 509, 55–62 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker L. M.et al.; Protocol G Principal Investigators , Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science 326, 285–289 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker L. M.et al.; Protocol G Principal Investigators , Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature 477, 466–470 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sok D., et al., Recombinant HIV envelope trimer selects for quaternary-dependent antibodies targeting the trimer apex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 17624–17629 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorman J., et al., Structure of super-potent antibody CAP256-VRC26.25 in complex with HIV-1 envelope reveals a combined mode of trimer-apex recognition. Cell Rep. 31, 107488 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pancera M., et al., Crystal structure of PG16 and chimeric dissection with somatically related PG9: Structure-function analysis of two quaternary-specific antibodies that effectively neutralize HIV-1. J. Virol. 84, 8098–8110 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLellan J. S., et al., Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature 480, 336–343 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pernis B., Chiappino G., Kelus A. S., Gell P. G., Cellular localization of immunoglobulins with different allotypic specificities in rabbit lymphoid tissues. J. Exp. Med. 122, 853–876 (1965). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu M., et al., Two levels of protection for the B cell genome during somatic hypermutation. Nature 451, 841–845 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doria-Rose N. A., et al., New member of the V1V2-directed CAP256-VRC26 lineage that shows increased breadth and exceptional potency. J. Virol. 90, 76–91 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenzi J. C. C., et al. Neutralizing activity of broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies against primary African isolates. J. Virol. e01909 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sale J. E., Neuberger M. S., TdT-accessible breaks are scattered over the immunoglobulin V domain in a constitutively hypermutating B cell line. Immunity 9, 859–869 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin A., Scharff M. D., Somatic hypermutation of the AID transgene in B and non-B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12304–12308 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zetsche B., et al., Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 163, 759–771 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brinkman E. K., Chen T., Amendola M., van Steensel B., Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, e168 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrabi R., et al., Identification of common features in prototype broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV envelope V2 apex to facilitate vaccine design. Immunity 43, 959–973 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dosenovic P., et al., Immunization for HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies in human Ig knockin mice. Cell 161, 1505–1515 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borst A. J., et al., Germline VRC01 antibody recognition of a modified clade C HIV-1 envelope trimer and a glycosylated HIV-1 gp120 core. eLife 7, e37688 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turchaninova M. A., et al., High-quality full-length immunoglobulin profiling with unique molecular barcoding. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1599–1616 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briney B., Inderbitzin A., Joyce C., Burton D. R., Commonality despite exceptional diversity in the baseline human antibody repertoire. Nature 566, 393–397 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rada C., Jarvis J. M., Milstein C., AID-GFP chimeric protein increases hypermutation of Ig genes with no evidence of nuclear localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7003–7008 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang W., et al., Clonal instability of V region hypermutation in the Ramos Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line. Int. Immunol. 13, 1175–1184 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geisberger R., Rada C., Neuberger M. S., The stability of AID and its function in class-switching are critically sensitive to the identity of its nuclear-export sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6736–6741 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Findlay G. M., Boyle E. A., Hause R. J., Klein J. C., Shendure J., Saturation editing of genomic regions by multiplex homology-directed repair. Nature 513, 120–123 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason D. M., et al., High-throughput antibody engineering in mammalian cells by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-directed mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 7436–7449 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otsuka Y., et al., Diverse pathways of escape from all well-characterized VRC01-class broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1007238 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinlan B. D., Gardner M. R., Joshi V. R., Chiang J. J., Farzan M., Direct expression and validation of phage-selected peptide variants in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 18803–18810 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torrents de la Peña A., et al., Improving the immunogenicity of native-like HIV-1 envelope trimers by hyperstabilization. Cell Rep. 20, 1805–1817 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sliepen K., et al., Structure and immunogenicity of a stabilized HIV-1 envelope trimer based on a group-M consensus sequence. Nat. Commun. 10, 2355 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guenaga J., et al., Structure-guided redesign increases the propensity of HIV Env to generate highly stable soluble trimers. J. Virol. 90, 2806–2817 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrabi R., et al., Glycans function as anchors for antibodies and help drive HIV broadly neutralizing antibody development. Immunity 47, 524–537.e3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.deCamp A., et al., Global panel of HIV-1 Env reference strains for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 88, 2489–2507 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhiman J. N., et al., Viral variants that initiate and drive maturation of V1V2-directed HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 21, 1332–1336 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seo H., et al., Rapid generation of specific antibodies by enhanced homologous recombination. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 731–735 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L., Jackson W. C., Steinbach P. A., Tsien R. Y., Evolution of new nonantibody proteins via iterative somatic hypermutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16745–16749 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arakawa H., et al., Protein evolution by hypermutation and selection in the B cell line DT40. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, e1 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L., Tsien R. Y., Evolving proteins in mammalian cells using somatic hypermutation. Nat. Protoc. 1, 1346–1350 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cumbers S. J., et al., Generation and iterative affinity maturation of antibodies in vitro using hypermutating B-cell lines. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 1129–1134 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowers P. M., et al., Coupling mammalian cell surface display with somatic hypermutation for the discovery and maturation of human antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20455–20460 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ford G. S., Yin C. H., Barnhart B., Sztam K., Covey L. R., CD40 ligand exerts differential effects on the expression of I gamma transcripts in subclones of an IgM+ human B cell lymphoma line. J. Immunol. 160, 595–605 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ou T., et al., Efficient reprogramming of the heavy-chain CDR3 regions of a human antibody repertoire. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2021). 10.1101/2021.04.01.437943 (Accessed 3 April 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Davis-Gardner M. E., Alfant B., Weber J. A., Gardner M. R., Farzan M., A bispecific antibody that simultaneously recognizes the V2- and V3-glycan epitopes of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein is broader and more potent than Its parental antibodies. MBio 11, e03080 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.