Abstract

Regulating insulin and leptin levels using a protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibitor is an attractive strategy to treat diabetes and obesity. Glycyrrhetinic acid (GA), a triterpenoid, may weakly inhibit this enzyme. Nonetheless, semisynthetic derivatives of GA have not been developed as PTP1B inhibitors to date. Herein we describe the synthesis and evaluation of two series of indole- and N-phenylpyrazole-GA derivatives (4a–f and 5a–f). We measured their inhibitory activity and enzyme kinetics against PTP1B using p-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) assay. GA derivatives bearing substituted indoles or N-phenylpyrazoles fused to their A-ring showed a 50% inhibitory concentration for PTP1B in a range from 2.5 to 10.1 µM. The trifluoromethyl derivative of indole-GA (4f) exhibited non-competitive inhibition of PTP1B as well as higher potency (IC50 = 2.5 µM) than that of positive controls ursolic acid (IC50 = 5.6 µM), claramine (IC50 = 13.7 µM) and suramin (IC50 = 4.1 µM). Finally, docking and molecular dynamics simulations provided the theoretical basis for the favorable activity of the designed compounds.

Keywords: protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, glycyrrhetinic acid, p-nitrophenylphosphate assay, molecular docking, molecular dynamics

1. Introduction

For many years, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) has been known for its role in the negative regulation of the insulin and leptin signaling pathway [1,2,3,4]. Therefore, blocking this enzyme is an attractive strategy to treat both diabetes and obesity, which represents an advantage over existing therapies to date. Furthermore, PTP1B has gained much attention in recent years since it is involved in other diseases such as Alzheimer’s [5], Parkinson’s disease [6,7], cardiovascular disorders [8,9,10,11], and malignant tumors [12,13,14,15,16]. This makes the development of PTP1B inhibitors even more interesting.

Extensive research has demonstrated that natural oleanane-type pentacyclic triterpenes display potent inhibitory activity and selectivity against PTP1B [17,18,19,20,21]. Maslinic acid [22,23], oleanolic acid [24,25,26] and celastrol [27,28,29] are the most representative examples of this type of inhibitors. Less known is glycyrrhetinic acid (GA), which is an oleanane-type triterpene found abundantly (up to 24%) as glycyrrhizin in the root of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) [30,31,32]. GA has shown several beneficial pharmacological activities including anti-viral, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-fungal and hepatoprotective properties [33]. Furthermore, oral administration of 18β-GA (100 mg/kg) enhances insulin levels and reduces blood glucose levels comparable to that of glibenclamide in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [34,35]. Recently it has been demonstrated that GA improves glucose uptake and reverses insulin resistance by targeting RAS proteins and activating the PI3K/Akt pathway, respectively [36]. In a patent application, GA was also shown to reduce the lipid synthesis or formation of very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL’s) [37]. Moreover, both GA epimers (18α and 18β) have been identified as weak competitive PTP1B inhibitors [38,39]. Interestingly, GA can cross the blood-brain barrier [40,41] which is an essential property in the context of PTP1B inhibitors. Reducing the hypothalamic PTP1B activity of obese mice has been shown to greater enhance leptin and insulin sensitivity than that of other tissues, which also effectively decreases adiposity and improves glucose metabolism [3,42]. Hence, we believe that GA is an attractive scaffold for further chemical modifications to improve its PTP1B-inhibitory activity.

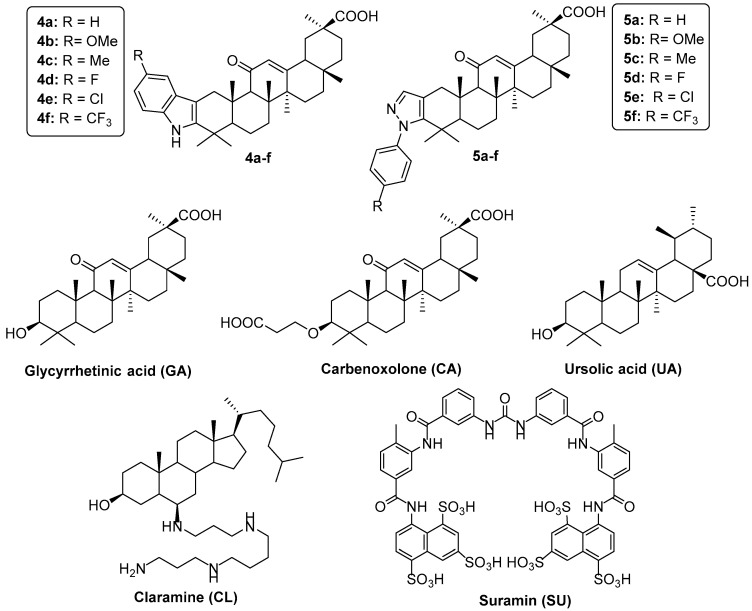

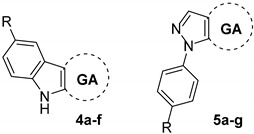

Accordingly, it should be noted that the semisynthesis of ring-substituted triterpenes having nitrogenated heterocycles fused to the A-ring has been reported as a strategy for improving PTP1B inhibitory activity [19,20]. For instance, combining the indole or N-phenylpyrazole scaffold to maslinic acid (MA, an olenane-type triterpene) has dramatically improved the potency of this triterpenoid [43]. Moreover, the presence of indole or N-phenylpyrazole moieties at the A-ring of MA produced more potent PTP1B inhibitors than other heterocycles such as thiazole, pyrimidine, quinazoline and pyrazine. Therefore, this strategy could be applied to GA, but it remains to be validated, since no attempt of semisynthetic heterocyclic ring-substituted GA derivatives as PTP1B inhibitors has been reported to date. Thus, we focused on increasing the inhibitory activity of GA, which is relatively easy and cheap to obtain in large quantities from plant extracts. To do so, we synthesized two series of GA derivatives (Figure 1): series one regroups six A-ring-fused indoles, whereas series two regroups six A-ring-fused N-phenylpyrazoles. It is well-known that the catalytic site of PTP1B is a positively-charged pocket formed by side chains of Tyr46, Arg45, Asp48, Lys120, Phe182, Ile219, Asp181 and Gln262 [44], whereas the allosteric binding site has a hydrophobic pocket formed by side chains of Leu192, Asn193, Phe196 Glu276, Lys279, and Phe280 [45]. From these observations, we hypothesized that introducing an atom or group of atoms bearing a partially negative charge (e.g., -OCH3, -F, -C and -CF3), as well as hydrophobic groups (e.g., -CH3 and -CF3) on the phenyl moiety of indole (series one) and N-phenylpyrazole (series two), can improve dipole-dipole and hydrophobic interactions at both catalytic and allosteric binding sites, respectively. Moreover, the size of these groups could promote an ideal orientation for the designed compounds to perform π-stacking and hydrophobic interactions between the phenyl moiety and the side chains of aromatic amino acids at the allosteric binding site.

Figure 1.

GA derivatives 4a–f and 5a–f, glycyrrhetinic acid, carbenoxolone, ursolic acid, claramine and suramin.

The newly synthesized compounds were tested at several concentrations against PTP1B. Their inhibitory activity was compared to the reference compounds carbenoxolone (CA), ursolic acid (UA), claramine (CL) and suramin (SU) (Figure 1). UA is a natural ursane-type pentacyclic triterpenoid that has been identified as a potent PTP1B inhibitor. Moreover, this compound enhances insulin receptor signaling and stimulates glucose uptake in vitro [46]. The second, CL, is a potent allosteric PTP1B inhibitor that has been shown to restore glycemic control and cause weight loss without increasing energy expenditure in mice. Due to its similar structure to trodusquemine, it has been proposed that CL targets the disordered C terminus of PTP1B [47,48]. Finally, SU is an anti-trypanosomal drug used to treat African sleeping sickness and river blindness. However, it has shown potent competitive PTP1B inhibitory activity [49]. On the other hand, despite the PTP1B inhibitory activity of CA (the hemisuccinate derivative of GA), it has not been reported on to date; thus, we decided to assess this compound because of its similar structure to GA. CA has been widely used to treat gastric ulcers and other types of inflammation by targeting 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD). It has also shown amelioration of metabolic syndrome in obese rats [50].

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

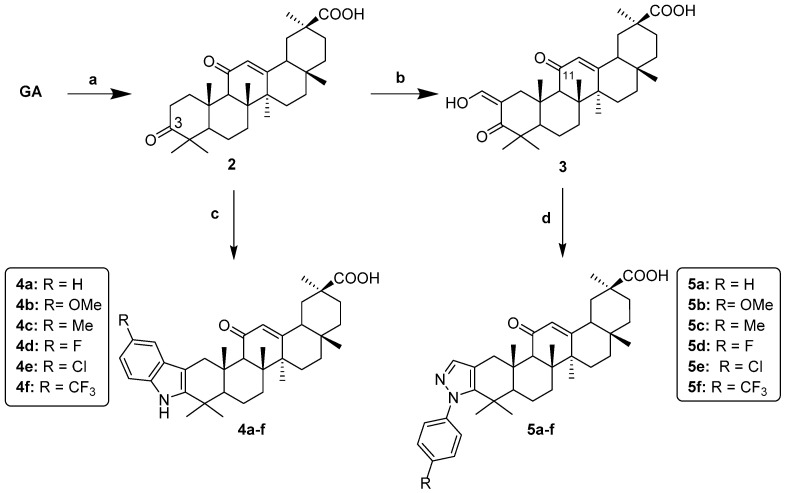

The synthetic route for the synthesis of indole- and pyrazole-GA derivatives is shown in Scheme 1. Briefly, GA was oxidized to ketone (2) using Jones reagent. Indole-GA derivatives (4a–f) were prepared using Fischer indolization by reacting compound 2 with phenylhydrazine or p-substituted phenylhydrazines in refluxing acetic acid. It is worth mentioning that these final compounds were obtained in good overall yields. On the other hand, the intermediate 2 was reacted with ethyl formate in the presence of NaH to afford compound 3. Afterwards, this 1,3-dicarbonylic intermediate was reacted with the corresponding phenylhydrazine or p-substituted phenylhydrazines to afford the N-phenylpyrazole-GA derivatives (5a–f) in moderate yields.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CrO3/H2SO4, acetone 0 °C, overnight; (b) ethyl formate, NaH, dioxane, 40 °C, 1 h then 100 °C, 4 h; (c) Ar-NHNH2 hydrochloride, AcOH, reflux, 2 h; (d) Ar-NHNH2 hydrochloride, EtOH, 70 °C, 1 h.

2.2. NMR Characterization of Compounds 4f and 5f

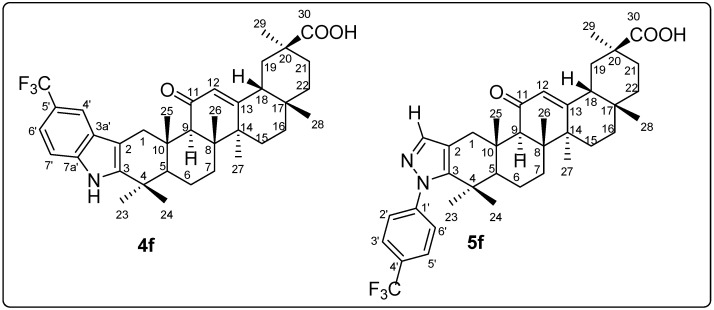

The sequence of reactions used herein made it possible to obtain series 4a–f and 5a–g. However, it was necessary to confirm that the indole and pyrazole heterocycles were fused to the A-ring of GA. Therefore, to obtain a full assignation for H and C atoms, we carried out an analysis for the most representative compounds 4f and 5f (Figure 2) using 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra along with COSY, HSQC, HMBC and NOESY experiments (Table S1).

Figure 2.

Carbon numbering used for the assignment of 1H NMR and 13C NMR signals of 4f and 5f.

For both analogs, the chemical shift data of the GA skeleton is in accordance with previous studies [51,52]. However, in the 1H NMR spectra, there are some representative signals in the aromatic region from 7.2 to 7.9 ppm. The two doublets (J = 7.8 and 7.9 Hz) characteristic of a para substituted pattern, were assigned to the phenyl ring of compound 5f, whereas a singlet at 7.36 ppm corresponded to the pyrazole ring. On the other hand, two singlets with different intensities at 7.79 ppm (H–4′) and 7.34 ppm (H–6′ and H–7′) for 4f were found; these signals along with a broad singlet at 7.91 ppm (NH) correspond to the indole ring.

When the indolization reaction was carried out, the signal at about 217 ppm (C3 carbonyl for compound 2) is shifted upfield for compound 4f at 142.1 ppm in the 13C NMR spectra. Similarly, when N-phenylpyrazole was prepared, both signals at 200 and 210 ppm (C3 carbonyl and formyl at C2, for intermediate 3) are shifted upfield for compound 5f at 145.79 and 114.4 ppm, respectively. Using an HMBC experiment, we first identified the methyl groups that produced correlation with the C3 signal in both 4f and 5f. The correlations observed with 23–CH3 and 24–CH3 in combination with 13C NMR data found in literature allowed the identification of the following carbons: 1–CH2, 2–C, 4–C, 5–CH, 10–C. Using an HSQC experiment, the 5–C signals observed at 53.1 ppm (for 4f) or 53.58 ppm (for 5f) were linked to the 5α–H at 1.44 ppm (for 4f) and 1.20 ppm (for 5f), respectively. In the HMBC experiment, the 5α–H signal allowed the identification of 25β–CH3 which correlates with a signal at about 37 ppm (for both 4f and 5f) as well as 108 ppm (for 4f) and 114 ppm (for 5f). These signals correspond to 1–C and 2–C carbons. The 1–C signal was linked to both 1–CH2 hydrogens at 2.3 and 4.0 ppm for 4f as well as 2.2 and 3.6 ppm for 5f. The signal at 2.3 ppm (for 4f) and 2.2 ppm (for 5f) produces a NOE correlation with 25β–CH3; hence, it corresponds to 1β–H, whereas the signal at 4.0 ppm (for 4f) and 3.6 ppm (for 5f) corresponds to 1α–H. It is worth mentioning that both 1–CH2 signals are shifted downfield compared to compound 2, which is possible with the presence of heterocycles fused to the C2 and C3 positions of the triterpenoid skeleton.

2.3. PTP1B Inhibitory Activity of Indole- and Pyrazole-GA Derivatives

Compounds 4a–f and 5a–f were tested against PTP1B enzyme to determine their ability to inhibit the formation of p-nitrophenol from p-nitrophenylphosphate. Different concentrations of 4a–f and 5a–f, as well as reference inhibitors GA, CA, UA, SU and CL, provided the IC50 values shown in Table 1. The first general observation from these data is that the fusion of both indole and N-phenylpyrazole heterocycles to the GA skeleton yielded potent PTP1B inhibitors (IC50 values ranging from 10.1 to 2.5 µM) with 6 to 25-fold better potency than GA (IC50 = 62.0 µM). The newly-designed compounds exhibited better inhibitory effect against PTP1B than that shown by positive controls UA (IC50 = 5.6 µM), CA (IC50 = 69.7 µM) and CL (IC50 = 13.7 µM). Precisely, the order of potency for indole–GA inhibitors was 4f > 4b > 4d > 4a > 4c > 4e whereas for N-phenylpyrazole–GA inhibitors, the order was 5f > 5b = 5c = 5a > 5e > 5d. Thus, the substituent attached to the phenyl moiety modulates the PTP1B inhibitory activity. In this way, we noticed that introducing a chlorine atom or a methyl group at the C5′ position of the indole ring has a negative impact on activity compared to 4a (IC50 = 6.6 µM). Conversely, introducing a fluorine, methoxy or trifluoromethyl group at the same position greatly increases the potency. Indeed, 4f (IC50 = 2.5 µM) is the most potent PTP1B inhibitor among the two series. It is also worth noting that this inhibitor is the only one that showed better potency than that of SU (IC50 = 4.1 µM). On the other hand, for N-phenylpyrazole–GA inhibitors, the presence of fluorine (5d: IC50 = 9.6 µM) and chlorine (5e: IC50 = 7.5 µM) at the phenyl moiety is not well tolerated when compared to the unsubstituted derivative 5a (IC50 = 5.1 µM). Contrarily, methoxy (5b: IC50 = 4.8 µM), methyl (5c: IC50 = 4.8 µM) and trifluoromethyl (5f: IC50 = 4.4 µM) groups improve the inhibitory activity against PTP1B.

Table 1.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibitory activity of indole– and pyrazole–GA derivatives (4a–f and 5a–f).

| Compound | R | IC50 (µM ± S.D) |

|---|---|---|

| 4a | H | 6.6 ± 0.13 |

| 4b | OCH3 | 4.3 ± 0.26 |

| 4c | CH3 | 8.3 ± 0.10 |

| 4d | F | 5.2 ± 0.22 |

| 4e | Cl | 10.1 ± 0.21 |

| 4f | CF3 | 2.5 ± 0.03 |

| 5a | H | 5.1 ± 0.56 |

| 5b | OCH3 | 4.8 ± 0.20 |

| 5c | CH3 | 4.8 ± 0.30 |

| 5d | F | 9.6 ± 0.20 |

| 5e | Cl | 7.5 ± 0.22 |

| 5f | CF3 | 4.4 ± 0.07 |

| GA | - | 62.0 ± 5.04 |

| CA | - | 69.7 ± 6.98 |

| UA a | - | 5.6 ± 0.23 |

| CL a | - | 13.7 ± 0.11 |

| SU a | - | 4.1 ± 0.12 |

a Positive controls. Values are represented as three independent determinations.

According to these findings, we believe that indole–GA derivatives bearing electronegative as well as HBA groups improve their inhibitory activity against PTP1B. In contrast, bulky hydrophobic groups attached to N-phenylpyrazole–GA derivatives had a positive impact on their potency. Furthermore, it is important to mention that the incorporation of trifluoromethyl groups significantly enhanced the inhibitory effect of both series.

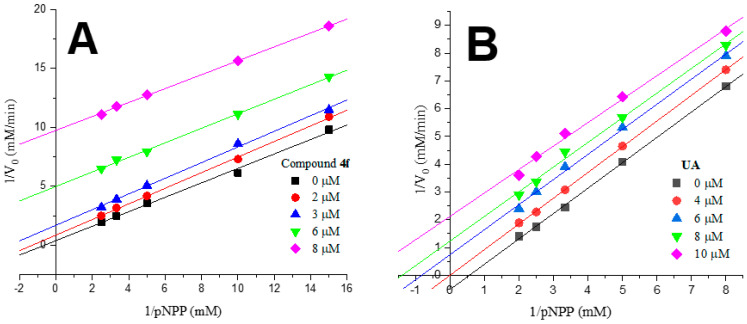

2.4. Enzymatic Kinetic Studies

Some compounds were chosen to perform enzyme kinetic assays to investigate their type of inhibition. Kinetic analyses were performed at different concentrations of substrate and inhibitor. Table 2 and Figure 3 show the kinetic parameters and the graphic representation (Lineweaver-Burk plot). Compounds 4f, 5f, UA, and CL show non-competitive inhibition (Ki values: 3.9, 4.6, 8.9, and 15.4 µM, respectively), and only SU shows competitive inhibition (Ki value = 7.1 µM). Knowing the type of inhibition of the enzyme–inhibitor complex is important to identify potential bioactive molecules to develop therapeutic agents and direct molecular modeling studies.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of PTP1B with different inhibitors.

| Compound | Ki (µM) | Inhibition Type |

|---|---|---|

| 4f | 3.9 ± 0.5 | non-competitive |

| 5f | 4.6 ± 0.6 | non-competitive |

| UA | 8.9 ± 0.7 | non-competitive |

| CL | 15.4 ± 1.7 | non-competitive |

| SU | 7.1 ± 0.9 | competitive |

Figure 3.

Lineweaver-Burk plots for PTP1B inhibition of 4f (A) and UA (B).

2.5. Molecular Docking Studies

To investigate the potential binding modes of 4a–f and 5a–f, we carried out a consensus docking simulation using Autodock (AD), Autodock Vina and GOLD. This study was performed employing the three aforementioned docking softwares to combine the information of multiple scoring functions to identify the correct or most accurate solution for each ligand–protein interaction. The designed compounds and controls were docked at the catalytic site (PDB ID: 1C83 [44]) and the experimentally validated allosteric site (PDB ID: 1T49 [45]) using the X–ray structures of PTP1B. Since docking validation is an important aspect for measuring the quality of the docking protocol, we re-docked the co-crystal structures found in both 1C83 and 1T49 complexes. To do so, 6-(oxalyl-amino)-1H-indole-5-carboxylic acid (AOI) was docked into the active site (PDB ID: 1C83) while 3-(3,5-dibromo-4-hydroxybenzoyl)-2-ethyl-benzofuran-6-sulfonic acid (4-sulfamoyl-phenyl)-amide (892) was docked at the allosteric binding site (PDB ID: 1T49). The resulting docking simulations for both ligands (Table 3) provided lower binding free energies in AD and Vina as well as higher CHEMPLP fitness score (CS) and GoldScore (GS) values in GOLD, indicating a favorable ligand binding affinity to their respective binding sites.

Table 3.

Docking validation of co-crystalized structures AOI and 892 at the catalytic site and allosteric binding site, respectively.

| Compound | Autodock | Autodock Vina | GOLD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcal/mol (RMSD) | kcal/mol (RMSD) | CS (RMSD) | GS (RMSD) | |

| AOI | −9.8 (0.41) | −7.9 (0.72) | 75.9 (0.40) | 62.6 (0.40) |

| 892 | −11.5 (1.22) | −9.3 (1.32) | 109.8 (0.61) | 78.4 (0.61) |

After superimposing the binding pose of the re-docked structure onto the binding pose of the co-crystal structure, a root mean square deviation (RMSD) value of less than 1.5 Å was obtained. We therefore believe that the docking protocol presented herein is a good reproduction of the correct binding for the co-crystal ligands. Hence, it may be efficient to predict the most favorable binding pose for the designed compounds and controls.

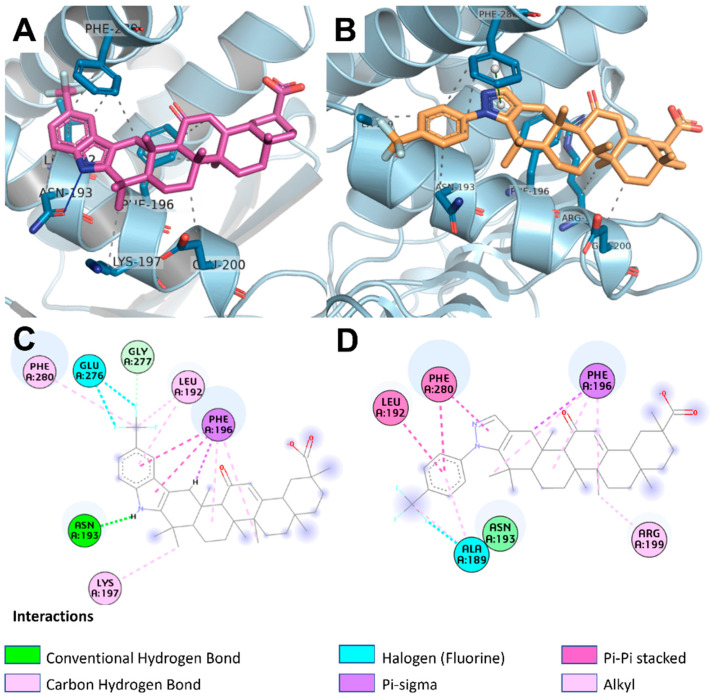

As shown in Table 4, SU fitted better at the catalytic site, providing lower binding free energies (−15.6 and −9.2 kcal/mol for AD and Vina respectively) than those of the allosteric binding site (−11.2 and −7.2 kcal/mol for AD and Vina, respectively). Indeed, these data are in accordance with our enzymatic kinetic studies where SU is a competitive inhibitor. Similarly, GA and CA showed more favorable binding energies and scores at the catalytic site. Conversely, UA displayed similar binding energies as well as scores at both catalytic and allosteric binding sites of PTP1B. Therefore, we cannot discern for which does it have more affinity. As expected, the synthesized derivatives (4a–f and 5a–f) showed better binding free energies and scores than those of reference compounds GA, CA and UA at both the catalytic and allosteric binding sites of PTP1B. Nevertheless, most of these compounds yielded lower binding free energies as well as higher scores for the allosteric binding site, which indicates that they preferably interact with this one; this in turn may explain why compounds 4f and 5f are non-competitive inhibitors. Precisely, the triterpenoid 4f gave better binding free energy values and scores [−8.8 kcal/mol (AD), −9.9 kcal/mol (Vina), 59.5 (CS) and 49.6 (GS)] compared to 5f [−8.3 kcal/mol (AD), −8.2 kcal/mol (Vina), 43.7 (CS) and 28.5 (GS)]. Interestingly, both analogs fit with the same orientation into the allosteric binding site (Figure 4). For instance, the pyrazole and indole moiety of 4f and 5f, respectively, perform key π-stacking interactions as well as hydrophobic contacts with the side chain of Phe196 and Leu192. Additionally, the triterpenoid skeleton of both derivatives also interacts by means of hydrophobic contacts with Phe196 residue. However, compound 4f produces an H–bond between its NH group and the carbonyl group from the side chain of Asn193, while compound 5f shows an extra π-stacking interaction between its phenyl moiety and the side chain of Phe280 which is absent in compound 4f. Surprisingly, both compounds performed halogen interactions between their -CF3 group and Glu276 or Ala189. Of note, it has been demonstrated that the -CF3 group can enhance ligand binding affinity through close contacts with backbone carbonyl groups in a protein (orthogonal multipolar C–F···C=O interactions) [53]. Thus, this may explain why the -CF3 group significantly enhanced the PTP1B inhibitory activity in both GA series. From docking results, we consider that moieties able to perform π-stacking interactions (such as pyrazole and indole) play a critical role in improving the binding affinity into the allosteric binding site of PTP1B.

Table 4.

Molecular docking results for derivatives 4a–f and 5a–f.

| Compound | Catalytic Site a | Allosteric–Binding Site b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcal/mol c | kcal/mol d | CS e | GS f | kcal/mol c | kcal/mol d | CS e | GS f | |

| 4a | −8.9 | −9.6 | 60.5 | 47.3 | −9.4 | −10.0 | 59.8 | 20.6 |

| 4b | −9.2 | −8.5 | 44.1 | 43.5 | −9.4 | −10.1 | 55.1 | 35.2 |

| 4c | −8.7 | −8.7 | 56.7 | 31.6 | −9.2 | −10.7 | 69.8 | 45.0 |

| 4d | −8.6 | −9.4 | 56.3 | 43.5 | −8.9 | −10.2 | 58.1 | 16.7 |

| 4e | −8.5 | −8.5 | 52.6 | 31.8 | −9.1 | −10.0 | 56.6 | 13.0 |

| 4f | −7.9 | −9.1 | 47.8 | 46.7 | −8.8 | −9.9 | 59.5 | 40.6 |

| 5a | −9.2 | −8.3 | 44.6 | 33.4 | −9.3 | −7.2 | 70.6 | 8.9 |

| 5b | −9.2 | −7.7 | 46.1 | 4.7 | −9.2 | −7.8 | 66.9 | 32.5 |

| 5c | −9.9 | −8.0 | 49.4 | 27.0 | −8.7 | −9.2 | 42.7 | 10.5 |

| 5d | −8.9 | −8.0 | 60.1 | 21.8 | −8.6 | −8.5 | 41.4 | 4.1 |

| 5e | −8.5 | −7.7 | 49.2 | 23.7 | −8.7 | −8.3 | 69.8 | 6.4 |

| 5f | −7.6 | −8.5 | 41.1 | 6.4 | −8.3 | −8.2 | 43.7 | 28.5 |

| GA | −7.9 | −7.1 | 40.1 | 16.1 | −7.6 | −7.5 | 40.2 | 23.4 |

| CA | −10.9 | −7.5 | 54.8 | 31.1 | −8.2 | −7.7 | 53.5 | 23.3 |

| UA | −8.6 | −7.6 | 54.0 | 23.9 | −8.0 | −7.5 | 47.3 | 31.4 |

| SU | −15.6 | −9.2 | ND | ND | −11.2 | −7.2 | ND | ND |

a Using the X-ray structure of PTP1B (PDB ID: 1C83); b Using the X-ray structure of PTP1B (PDB ID: 1T49); c Binding energy values retrieved from Autodock; d Binding energy values retrieved from Autodock Vina; e CHEMPLP score values retrieved from GOLD; f GoldScore values retrieved from GOLD.

Figure 4.

Binding mode of 4f (A) and 5f (B) docked into the allosteric binding site of PTP1B (cyan). 2D diagram of docked 4f (C) and 5f (D) in PTP1B, showing interactions with the residues at the allosteric binding site.

2.6. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the YASARA structure software [54] and the AMBER14 [55] forcefield. Three different studies were carried out for the positive control UA and derivatives 4f and 5f resulting from the docking simulations at the allosteric binding site of PTP1B. In the first one, we evaluated RMSD fluctuations of the Cα carbons to know the stability of each protein–ligand complex. In the second, we calculated the binding affinity of each ligand at the allosteric site of PTP1B during a period of 50 nanoseconds of MD simulation. Finally, to find out the efficacy of the compounds UA, 4f and 5f to dissociate from the allosteric site of PTP1B, we carried out a steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulation where a steering potential was applied to pull the ligand outside of the protein.

2.6.1. Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) Analysis

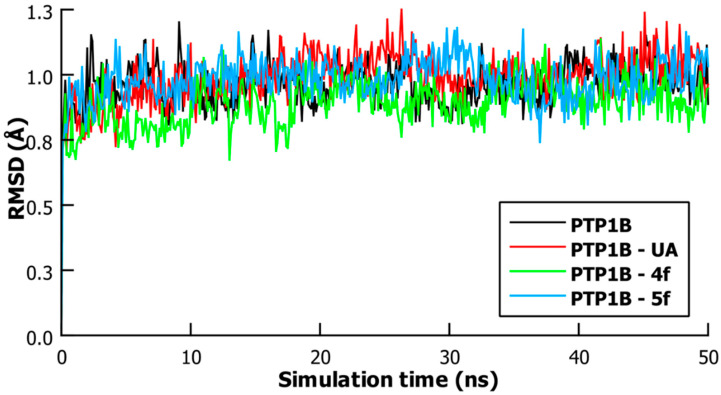

In this study, we performed an RMSD analysis on the PTP1B protein system and the PTP1B protein–ligand complexes of UA, 4f and 5f during 50 nanoseconds of time simulation. The results of this analysis can be employed as a measure of the overall fluctuation of the protein’s Cα carbons. Thus, the lower the value of RMSD, the less fluctuation of the Cα carbons there are, and therefore more stability for the protein’s main chain atoms. It is important to mention that PTP1B’s crystal structure used in this study (PDB ID: 1T49) exists as a catalytically inactive conformation. Thus, lower RMSD values indicate that the ligand stabilizes this form. As shown in Figure 5, the PTP1B system tends to stabilize after 3 nanoseconds with an average RMSD value = 1.02 Å (from 3 to 50 nanoseconds). However, slightly lower mean RMSD values were found in the PTP1B–UA and PTP1B–5f complexes (1.01 and 1.00 Å, respectively), which indicates that both compounds can stabilize the PTP1B protein system. At the same time, it can be clearly seen that the overall fluctuation of the PTP1B–4f complex is the lowest among the three (mean RMSD value = 0.91 Å), suggesting that the binding of 4f at the allosteric site has the best impact for stabilizing the overall conformation of PTP1B in its inactive state.

Figure 5.

Standard RMSD of PTP1B, PTP1B–UA, PTP1B–4f and PTP1B–5f systems.

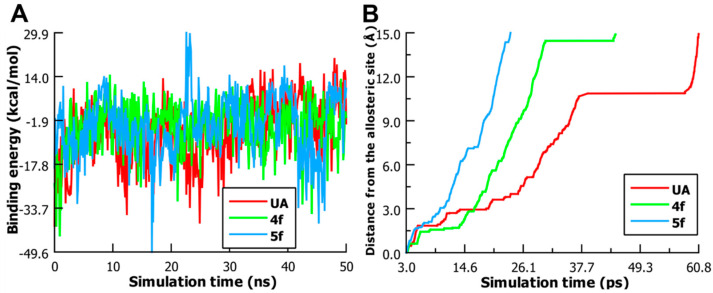

2.6.2. Binding Energy and Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) Studies

To quantitatively know the affinity of the three compounds to the allosteric binding site of PTP1B, we performed a binding energy analysis as a function of simulation time for a period of 50 nanoseconds including the binding energy average (Figure 6A). YASARA retrieves the binding energy by calculating the energy at an infinite distance between the selected object and the rest of the simulation system (i.e., the unbound state) and subtracting the energy of the simulation system (i.e., the bound state) every 100 picoseconds. Thus, more positive energy values indicate better binding [56] in the context of AMBER14 forcefield. Among the three simulated ligands, UA displayed an average binding energy value = −5.87 kcal/mol, whereas compounds 4f and 5f presented more positive binding energy profiles (average = −3.82 and −3.85 kcal/mol, respectively) suggesting better binding at this cavity. However, we noticed that 5f showed less homogenous fluctuations in its binding energy profile compared to UA and 4f. For instance, this compound exhibited strong negative as well as positive fluctuations at 16.4 nanoseconds (−21.13 kcal/mol) and 22.6 nanoseconds (29.5 kcal/mol) of MD simulation, respectively, which indicates less binding stability than 4f at the allosteric binding site of PTP1B.

Figure 6.

(A) Binding energy of UA, 4f and 5f as function of 50 ns of MD simulation. (B) SMD performed on PTP1B–ligand complexes to pull out ligands to a distance of 15 Å from the allosteric binding site.

To further provide information about the affinity of the ligands at the allosteric binding site, we carried out a SMD simulation. Of note, SMD is a special MD simulation where time-dependent external forces are applied to a ligand to facilitate its unbinding from a protein in order to study how both the ligand and the protein respond. The PTP1B complexes submitted to 50 nanoseconds MD simulations were used to pull off compounds UA, 4f and 5f to a distance of 15 Å from the allosteric binding site. The pulling was performed with a constant acceleration of 2000 pm/picoseconds2. As shown in Figure 6B, it can be clearly seen that compound 5f dissociates earlier (23.6 ps) from the allosteric binding site than 4f (44.4 ps). During the unbinding process of UA from PTP1B, we noticed that the carboxylate group of this triterpenoid formed a salt-bridge interaction with the ammonium group of Lys197. This strong interaction led to an increased residence time at this site. Thus, UA was found to be the last to leave the allosteric binding site (60.8 ps) among the three simulated ligands followed by compounds 4f and 5f.

Overall, the results from MD and SMD simulations indicate that 4f, 5f and UA can bind to the allosteric binding site. However, 4f is a more potent PTP1B inhibitor than 5f and UA due to the fact that it better stabilizes the overall inactive conformation of PTP1B and also showed the most positive average binding energy value. Due to the slow dissociation of UA from the allosteric binding site, we believe that this compound can occupy this cavity for a longer time, thus stabilizing for a longer period PTP1B in its catalytically inactive conformation. Hence, this may explain why UA exhibited a potent PTP1B inhibitory effect even though it showed a less favorable binding energy profile than 4f and 5f.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General

All chemicals and starting materials were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich. (Toluca MEX, Mexico and St. Louis, MO, USA). Reactions were monitored by TLC on 0.2 mm percolated silica gel 60 F254 plates (Sigma–Aldrich) and visualized by irradiation with a UV lamp. Melting points were determined in a Fisher–Johns melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Both 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were measured with Agilent DD2 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Bruker Ascend (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) spectrometers, operating at 600 MHz and 400 MHz for 1H, respectively and 151 MHz for 13C. Chemical shifts are given in parts per million, relative to tetramethylsilane (Me4Si, δ = 0); J values are given in Hz. Splitting patterns are expressed as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; q, quartet; dd, doublet of doublet; t, triplet; m, multiplet; bs, broad singlet. The numbering reported in Figure 2 was used for the assignment of 1H and 13C NMR signals. The UPLC–ESI–MS analyses for final compounds were performed on a Waters Acquity UPLC–HSS Class system (Waters, Wayland, MA, USA) equipped with a quaternary pump, sample manager, column oven, and photodiode array detector (PDA) interfaced with a SQD2 single-quadrupole mass spectrometer detector with an electrospray ion source. Empower software version 3 was used to control the UPLC–ESI–MS system and for data acquisition and processing. The analytical method was developed using an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 (3.0 × 100 mm, 8 μm). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% aqueous formic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B), with an isocratic elution of 20% A and 80% of B. The flow rate was set to 0.7 mL/min, injection volume was 10 μL, and column temperature was maintained at 22 °C using a column oven. All samples were analyzed at 0.01 mg/mL. The detection was carried out through the run at 190–790 nm, while MS parameters were as follows: the cone and capillary voltages were set at 15.0 V and 0.8 kV, respectively; the source temperature was 600 °C. ESI–MS spectra were obtained using nitrogen as the collision gas, within a mass range of m/z 50–600 Da (scan duration of 0.5 s). Each sample was analyzed in positive (ESI+) mode. Compounds were named using the automatic name generator tool implemented in ChemDraw Professional 16.0.1.4 software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA), according to IUPAC rules.

3.2. Synthesis

For the synthesis of GA compounds 4a–f and 5a–f (Scheme 1), the commercially available 18β–glycyrrhetinic acid was used. Compounds 2 and 3 were prepared by the procedure described in Refs. [57,58] with slight modifications. The synthesis of 4a–f and 5a–f is briefly described below.

3.2.1. Synthesis of 3,11-Dioxo-olean-12-en-30-oic Acid (2)

A solution of 18β–glycyrrhetinic acid (1.5 g, 3.2 mmol) in acetone (100 mL) was cooled to 0 °C; CrO3 (688 mg, 6.9 mmol) in sulfuric acid (98%, 4.6 mL) and water (15.7 mL) was then added slowly. The mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The acetone was evaporated, and the residue was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL) and washed with water and brine (1 × 50 mL). The combined organic layers were dried with sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to dryness. Finally, the solid was recrystallized from MeOH, CH2Cl2, and drops of water to give 2 (1.37 g, 91%) as colorless crystals. M.p. ˃ 300 °C (308 °C [57]); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 5.74 (s, 1H), 2.97 (m, 1H), 2.63 (m, 1H), 2.36 (ddd, J = 15.84, 6.4, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 2.20 (dd, J = 13.4 and 3.3 Hz, 1H), 2.01 (m, 2H), 1.93 (ddd, J = 13.7, 4.2, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 1.85 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 1.72–1.32 (m, 13H), 1.37 (s, 3H), 1.27 (s, 3 H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 0.85 (s, 3H). The spectroscopic data agrees with previously reported data [57].

3.2.2. General Procedure for Fischer Indolization (Compounds 4a–f)

A mixture of ketone 2 (0.42 mmol), phenylhydrazine (0.51 mmol) or p-substituted phenylhydrazine hydrochloride (0.51 mmol), and glacial acetic acid (4 mL) was heated at reflux during 2 h. When the mixture reached room temperature, the solid formed was collected by filtration, washed with cold glacial acetic acid and water. These compounds were pure enough and no additional purification steps were needed.

Compound 4a

Yield 55%; m.p. 245–248 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 8.82 (bs, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 5.68 (s, 1H), 3.83 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 2.57 (s, 1H), 2.19–2.13 (m, 2H), 2.10–1.47 (m, 16H), 1.33 (s, 3H), 1.24 (s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.12 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 0.75 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 199.9, 173.6, 169.7, 140.5, 136.2, 128.5, 127.9, 120.4, 118.2, 118.1, 110.3, 106.3, 60.3, 52.9, 48.4, 45.2, 43.4, 43.2, 41.1, 37.9, 37.7, 37.5, 33.9, 31.9, 31.7, 30.9, 30.8, 28.5, 28.4, 26.4, 26.3, 23.2, 23.1, 18.4, 18.2, 15.9. ESI–MS for C36H48NO3 [M+H]+: calc. 542.36 found 542.33; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 4.8 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/ 20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 4b

Yield 53%; m.p. 243–244 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 7.66 (bs, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (s, 1H), 3.92 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 2.68 (s, 1H), 2.27–2.21 (m, 2H), 2.10–1.47 (m, 16H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.31 (s, 3H), 1.24 (s, 3H), 1.24 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.07 (s, 1H), 1.05 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 0.87 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 200.3, 182.3, 169.5, 141.2, 131.3, 128.9, 128.7, 111.2, 110.3, 111.0, 107.2, 100.6, 60.7, 56.1, 53.1, 48.2, 45.6, 44.0, 43.5, 40.9, 38.2, 37.9, 37.8, 34.2, 32.2, 32.0, 31.2, 31.0, 28.7, 28.6, 26.7, 26.6, 23.7, 23.5, 18.6, 18.5, 16.2. ESI–MS for C37H50NO4 [M+H]+: calc. 572.37 found 572.38; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 4.6 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/ 20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 4c

Yield 61%; m.p. 268–271 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 8.89 (bs, 1H), 7.09 (d, J = 0.5 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 5.61 (s, 1H), 3.71 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 3.26 (s, 1H, Ar–CH3), 2.27–2.21 (m, 2H), 2.10–1.47 (m, 16 H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.31 (s, 3H), 1.24 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.17 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H), 0.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 200.3, 182.3, 169.4, 140.7, 134.9, 129.4, 129.0, 128.6, 122.9, 118.9, 110.3, 107.3, 61.0, 53.5, 48.6, 45.9, 44.3, 43.8, 41.4, 38.5, 38.2, 34.5, 32.6, 32.4, 31.5, 31.4, 29.1, 28.9, 27.1, 23.9, 23.8, 21.9, 19.0, 18.8, 16.5. ESI–MS for C37H50NO3 [M+H]+: calc. 556.80 found 556.41; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 6.2 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 4d

Yield 73%; m.p. 245–248 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 8.63 (bs, 1H), 7.13 (dd, J = 8.7 and 4.3 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (dd, J = 9.7 and 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (ddd, J = 18.0, 9.0 and 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.72 (s, 1H), 3.80 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 2.59 (s, 1H), 2.08–1.34 (m, 16H) 1.28 (s, 1H), 2.27–2.21 (m, 2H), 1.42 (s, 3H), 1.31 (s, 3H), 1.24 (s, 3H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.17 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.07 (m, 1H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H), 0.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 200.3, 182.7, 169.6, 159.3, 156.9, 142.6, 133.1, 129.3, 111.1, 109.5, 109.3, 108.1, 104.2, 60.9, 53.4, 48.6, 45.9, 44.3, 43.8, 41.4, 38.5, 38.2, 38.0, 34.6, 32.5, 31.5, 29.0, 28.9, 27.0, 24.0, 23.8, 19.0, 18.8, 16.5. ESI–MS for C36H47FO3 [M+H]+: calc. 560.77 found 560.37; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 5.1 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 4e

Yield 70%; m.p. 256–258 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 9.38 (bs, 1H), 7.24 (d, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (dd, J = 8.5 and 2.1 Hz, 1H), 5.61 (s, 1H), 3.71 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (s, 1H), 1.28 (s, 1H), 2.27–2.21 (m, 2H), 2.07–1.45 (m, 17H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.11 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.04 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H), 0.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 199.8, 180.8, 169.2, 141.9, 134.7, 129.0, 124.8, 121.3, 118.3, 111.2, 107.4, 60.6, 53.6, 53.1, 48.3, 45.5, 43.9, 43.5, 41.2, 38.2, 37.9, 37.6, 34.3, 32.1, 31.2, 28.7, 28.6, 26.7, 26.6, 23.6, 23.5, 20.5, 18.7, 18.5, 16.1. ESI–MS for C36H47ClNO3 [M+H]+: calc. 576.32 found 576.31; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 6.5 min, isocratic elution of 80 % CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 4f

Yield 69%; m.p. 267–269 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 7.91 (bs, 1H, NH), 7.79 (s, 1H, H–4′), 7.34 (s, 2H, H–6′and H–7′), 5.80 (s, 1H, H–12), 3.97 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H, 1α–H), 2.67 (s, 1H, H–9α), 2.29 (m, 1H, 1β–H), 2.25 (m, 1H, H–18β), 2.08 (m, 1H, H–15), 2.06 (m, 1H, H–16), 1.80 (m, 1H, H–7), 2.02 (m, 1H, H–19), 1.79 (m, 1H, H–21), 1.72 (m, 1H, H–6), 1.69 (m, 1H, H–19), 1.55 (m, 2H, H–7 and H–21), 1.44 (m, 2H, H–5α and H–22), 1.42 (s, 3H, 29–CH3), 1.39 (m, 1H, H–6), 1.33 (s, 3H, 24–CH3), 1.28 (m, 1H, H–16), 1.27 (s, 3H, 23–CH3), 1.24 (s, 3H, 26–CH3), 1.23 (s, 3H, 27–CH3), 1.18 (s, 3H, 25–CH3), 1.07 (m, 1H, H–16), 0.87 (s, 3H, 28–CH3). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 199.8 (C11), 182.1 (C30), 169.3 (C13), 142.1 (C3), 137.8 (C3a’), 129.0 (C12), 127.9 (C7a’), 126.1 (CF3), 121.6 (C5′), 118.0 (C6′), 116.4 (C4′), 110.4 (C7′), 108.4 (C2), 60.5 (C9), 53.1 (C5), 48.3 (C18), 45.5 (C8), 44.0 (C14), 43.5 (C20), 41.1 (C19), 38.1 (C10), 37.9 (C22), 37.5 (C1), 34.2 (C4), 32.2 (C7), 31.1 (C17), 28.7 (C26), 28.6 (C28), 27.7 (C15), 26.6 (C16), 23.6 (C29), 23.5 (C23), 18.7 (C6), 18.5 (C27), 16.2 (C25). ESI–MS for C37H47F3NO3 [M+H]+: calc. 610.77 found 610.36; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 7.0 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

3.2.3. Synthesis of 3,11-Dioxo-2-formylolean-12-en-30-oic Acid (3)

Under nitrogen atmosphere, compound 2 (500 mg, 1.1 mmol) was dissolved in dry dioxane (10 mL) and NaH (10 mmol) was slowly added. This mixture was heated to 45 °C; subsequently, ethyl formate (0.5 mL, 5.8 mmol) was added dropwise. After 45 min, the reaction mixture was refluxed for 5 h then cooled at room temperature and finally poured in 10% HCl (100 mL). The resulting precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using hexanes/ethyl acetate (80:20) to give 260 mg (50%) of 3 as colorless crystals. M.p: 260–263 °C. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 8.64 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 5.78 (s, 1H), 3.46 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 2.44 (s, 1H), 2.23 (dd, J = 13.4, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 1.94 (d, J = 15 Hz, 1H), 1.86 (td J = 13.6, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 1.63 (t, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 1.38 (s, 3H), 1.23 (s, 3H), 1.20 (s, 3H), 1.17 (s, 3H), 1.14 (s, 3H), 1.13 (s, 3H), 0.86 (s, 3H). The spectroscopic data agrees with previously reported data [58].

3.2.4. Synthesis of N-Phenylpyrazole Derivatives 5a–f

To a solution of compound 3 (150 mg, 0.3 mmol) in dry ethanol (5 mL), phenylhydrazine (0.45 mmol) or p-substituted phenylhydrazines hydrochloride (0.45 mmol) was added. This solution was stirred at 70 °C for 1 h, cooled at room temperature and the solvent was subsequently evaporated. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography using hexanes/ethyl acetate (from 80:20 to 70:30). Afterwards, the resulting compounds were recrystallized from CH2Cl2 and MeOH.

Compound 5a

Yield 32%; light yellow solid; m.p. 243–245 °C; 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 7.43 (m, 3H), 7.39 (m, 3H), 5.77 (s, 1H), 3.76 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (s, 1H), 2.04–1.21 (m, 17H), 1.38 (s, 3H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.18 (s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.85 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 200.0, 181.3, 169.7, 145.8, 142.3, 138.4, 129.3, 128.8, 114.4, 60.6, 60.5, 54.5, 48.3, 45.3, 43.9, 43.4, 41.1, 38.1, 37.8, 37.7, 34.9, 32.1, 32.0, 31.0, 29.5, 28.7, 28.6, 26.7, 26.5, 23.4, 22.6, 21.2, 18.5, 18.3, 15.7, 14.3. ESI–MS for C37H48N2O3 [M+H]+: calc. 569.80 found 569.32; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 6.3 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 5b

Yield 44%; colorless crystals; m.p. 208–211 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 7.37 (s, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.77 (s, 1H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.76 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (s, 1H), 2.26–1.41 (m, 17H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.86 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 199.9, 181.1, 169.7, 159.9, 145.9, 138.3, 135.2, 130.4, 128.9, 114.3, 113.7, 60.6, 55.7, 54.6, 48.3, 47.0, 45.0, 45.4, 43.9, 43.5, 42.2, 41.2, 38.2, 37.9, 37.8, 34.9, 32.2, 32.1, 31.1, 29.5, 28.8, 28.6, 26.7, 26.6, 23.4, 22.6, 18.4, 15.7. ESI–MS for C38H81N2O4 [M+H]+: calc. 599.80 found 599.39; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 5.7 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 5c

Yield 38%; colorless crystals; m.p. 240–241 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 5.78 (s, 1H), 3.76 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (s, 1H), 2.41 (s, 3H), 2.26–1.40 (m, 17H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.86 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 200.2, 181.4, 170.0, 146.1, 140.2, 139.3, 138.7, 129.5, 129.4, 129.2, 114.7, 60.9, 54.9, 48.7, 45.7, 44.2, 43.7, 41.5, 38.5, 38.2, 38.1, 35.2, 32.5, 32.4, 31.4, 29.9, 29.1, 28.9, 27.1, 26.9, 23.7, 22.9, 21.7, 18.9, 18.7, 16.1. ESI–MS for C38H51N2O3 [M+H]+: calc. 583.83 found 583.39; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 8.7 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 5d

Yield 42%; white solid; m.p. 260–264 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 7.37 (m, 3H), 7.11 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 5.78 (s, 1H), 3.77 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 2.56 (s, 1H), 2.09–1.23 (m, 17H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.86 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 199.8, 181.1, 180.1, 164.0, 161.5, 146.0, 138.8, 131.2, 131.1, 128.9, 115.7, 115.4, 114.7, 60.6, 54.6, 48.4, 45.4, 43.9, 43.5, 41.2, 38.2, 37.9, 37.8, 34.9, 32.2, 32.1, 31.1, 29.6, 28.8, 28.6, 26.7, 26.6, 23.4, 22.7, 18.6, 18.4, 15.8. ESI–MS for C37H48FN2O3 [M+H]+: calc. 587.79 found 587.36; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 6.2 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 5e

Yield 70%; colorless crystals; m.p. 263–266 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δH = 7.41 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (s, 1H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.78 (s, 1H), 3.77 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 2.56 (s, 1H), 2.13–1.23 (m, 17H), 1.39 (s, 3H), 1.22 (s, 3H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.07 (s, 3H), 1.03 (s, 3H), 0.86 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 200.2, 181.5, 181.4, 170.0, 146.4, 141.3, 139.3, 135.3, 131.0, 129.2, 115.1, 60.9, 54.9, 48.7, 45.7, 44.3, 43.8, 41.5, 38.5, 38.2, 38.0, 35.2, 32.5, 32.4, 31.5, 31.4, 29.9, 29.1, 28.9, 27.1, 26.9, 23.7, 23.1, 18.9, 18.7, 16.1. ESI–MS for C37H48ClN2O3 [M+H]+: calc. 603.24 found 603.34; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 9.5 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

Compound 5f

Yield 84%; m.p. 270–271 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δH = 7.86 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, H–2′ and H–6′), 7.61 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, H–3′ and H–5′), 7.36 (s, 1H, pyrazole–H), 5.47 (s, 1H, H–12), 3.55 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 1β–H), 2.57 (s, 1H, H–9), 2.17 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H, H–1α), 2.11 (m, 1H, H–19), 2.10 (m, 1H, H–16), 2.06 (m, 1H, H–18), 1.83 (m, 1H, H–21), 1.80 (m, 1H, H–15), 1.70 (m, 1H, H–7), 1.69 (m, 1H, H–19), 1.68 (m, 1H, H–6), 1.52 (m, 1H, H–6), 1.42 (m, 1H, H–7), 1.36 (m, 1H, H–22), 1.35 (m, 1H, H–15), 1.35 (s, 3H, 29–CH3), 1.33 (m, 1H, H–21), 1.32 (m, 1H, H–5), 1.25 (m, 1H, H–22), 1.08 (s, 3H, 26–CH3), 1.08 (s, 3H, 27–CH3), 0.99 (m, 1H, H–16), 0.97 (s, 3H, 23–CH3), 0.94 (s, 3H, 24–CH3), 0.75 (s, 3H, 28–CH3). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3): δC = 198.8 (C11), 177.8 (C30), 170.4 (C13), 145.9(C3a’), 145.8 (C3), 138.7 (C–pyrazole), 130.2 (C5′), 129.74 (C7′), 127.5 (C12), 126.2 (C6′), 126.1 (C4′), 126.08 (C7a’), 122.75 (CF3), 114.40 (C2) 59.8 (C9), 53.6 (C5), 48.25 (C18), 44.8 (C14), 44.7 (C8), 43.3 (C20), 41.02 (C19) 37.8 (C10), 37.7 (C22), 37.03 (C1), 34.5 (C4), 31.8 (C7), 31.5 (C17), 30.6 (C21), 29.5 (C23), 28.2 (C28), 28.0 (C27), 26.40 (C15), 26.0 (C16), 23.1(C29), 22.7 (C24), 18.1 (C26), 18.05 (C6), 15.63 (C25). ESI–MS for C38H48 F3N2O3 [M+H]+: calc. 637.80 found 637.41; UPLC purity of >95.0% (retention time = 8.7 min, isocratic elution of 80% CH3CN/20% aqueous formic acid 0.1%, Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column).

3.3. In Vitro Assays

3.3.1. PTP1B Inhibitory Assay

To test the inhibitory activity of the compounds against PTP1B, a spectrocolorimetric method previously described was employed [59,60]. The compounds and positive control were dissolved in DMSO or buffer solution [50 mM; Tris-HCI Buffer, pH 6.8], DL-dithiothreitol 1.5 mM, all from Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA. Aliquots of 0–10 μL of testing compounds (triplicated) were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C with 85 μL of enzyme stock solution (3 μM) in buffer solution. After incubation, 5 μL of the substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP, 0.5 mM, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added and incubated a further 25 min at 37 °C; then, the absorbance was recorded at 415 nm.

The IC50 was calculated by regression analysis using Equation:

where %PTP1B is the percentage of inhibition, A100 is the maximum inhibition, i is the inhibitor concentration, IC50 is the concentration required to inhibit the activity of the enzyme by 50%, and s is the cooperative degree.

3.3.2. Enzyme Kinetics

The kinetic studies were carried out under the same conditions described above. Different saturation curves were constructed at fixed inhibitor concentrations. The different inhibitor concentrations were determined based on the previously determined IC50 for each compound. Subsequently, the data obtained were analyzed through a non-linear regression, using OriginPro version 2018 (64-bit) SR1 (Northamton MA, USA, https://www.originlab.com) (accessed on 2 April 2021), adjusting to the following mathematical models:

Competitive:

where Vm is the maximum velocity, S is the substrate, Km is the Michaelis–Menten constant, Kic and Kiu are the competitive and uncompetitive inhibition constants, respectively.

And non-competitive:

where Vm is the maximum velocity, S and i are the concentration of substrate and inhibitor, respectively; Ki is the inhibition constant, and nh is the number of Hill.

The type of inhibition of PTP1B was determined by fitting the data to both models, where the fit with the best R2 indicates the type of inhibition of the compounds. Additionally, Lineweaver–Burk graphs were constructed to visualize the type of inhibition graphically [61].

3.4. In Silico Studies

Ligands were constructed and their geometry was optimized employing the semi-empirical Parameterization Method 3 (PM3) using Chem3D BioUltra 16.0 software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) with GAMESS interface [62]. X–ray structures of PTP1B were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/) (accessed on 10 April 2021) entries 1C83 and 1T49. Using YASARA structure (version 20.7.43) [54], first the water molecules were removed from the macromolecules, then their geometry was minimized employing the NOVA [63] forcefield by running the em_clean macro. After removing the co-crystallized ligand, the minimized structures (saved as *.pdb format) were used to dock each ligand employing Autodock 4.2 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) [64], Autodock Vina (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) [65] and GOLD (The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, UK) version 2020.2 [66]. On the other hand, MD simulations of ligand–protein complexes were performed using YASARA structure. The results from docking and MD simulations were visualized using PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC) and Protein Ligand Interaction Profiler server [67,68] whereas 2D–interaction diagrams were produced with Discovery Studio visualizer 2021 (Dassault Systèmes, San Diego, CA, USA) [69]. The protocol for docking and MD simulations studies was as follows.

3.4.1. Molecular Docking

For molecular docking using Autodock 4.2 and Autodock Vina, the graphical interface AutoDockTools 1.7.1 [64] suite was used to prepare and analyze the docking simulations. Hydrogen atoms were added to the macromolecules and Gasteiger–Marsilli charges were assigned to the atoms in the protein as well as ligands. Both protein and ligands were exported as *.pdbqt files. Docking simulations using Autodock 4.2 at the catalytic site of PTP1B (using 1C83 macromolecule) were performed with a grid box size: 45 Å × 60 Å × 47 Å with a spacing of 0.345 Å and coordinate: x = −21.39, y = 6.76 and z = −0.48; whereas docking simulations at the allosteric site of PTP1B (using 1T49 macromolecule) were performed with a grid box size: 60 Å × 60 Å × 60 Å with a spacing of 0.345 Å and coordinates x = 55.74, y = 33.41 and z = 24.47. The search was carried out with the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm. A total of 100 GA runs with a maximal number of 25,000,000 evaluations, a mutation rate of 0.02 and an initial population of 150 conformers were covered. Finally, each ligand with the best cluster size and the lowest binding energy was selected for further analysis. Molecular docking using Autodock Vina was carried out employing the same coordinates as previously mentioned, except that the grid box dimensions were: 16.8 Å × 22.5 Å × 17.6 Å and 22.5 Å × 22.5 Å × 22.5 Å for 1C83 and 1T49 macromolecules, respectively, and the exhaustiveness value was set to 500.

The resulting ligand complexes obtained for both 1C83 and 1T49 macromolecules were exported to GOLD. Using the GOLD wizard, the proteins were prepared by adding hydrogens and extracting the ligands which were further docked at the catalytic site or allosteric site within a 6 Å radius sphere was carried out using the following parameters: 100 genetic algorithm runs and 125,000 operations. CHEMPLP fitness was chosen as the main scoring function whereas GoldScore fitness was chosen as the re-scoring function. The dockings were ranked according to the value of the CHEMPLP and GoldScore fitness function.

Using the LigRMSD web server (https://ligrmsd.appsbio.utalca.cl/) (accessed on 12 April 2021), the docking protocol for each software was validated by comparing the RMSD value of the co-crystal structure and the docked structure [70].

3.4.2. MD Simulations

The ligand–protein complexes were submitted to MD simulations with YASARA Structure [54]. The simulations started by running the md_run macro, which included an optimization of the hydrogen bonding network to increase the solute stability, and a pKa prediction to fine-tune the protonation states of protein residues at the chosen pH of 7.4. NaCl ions were added with a physiological concentration of 0.9%, with an excess of either Na or Cl to neutralize the cell. After steepest descent and simulated annealing minimizations to remove clashes, the simulation was run for 50 nanoseconds using the AMBER14 force field [55] for the solute, GAFF2 [71] and AM1BCC [72] for ligands and TIP3P for water. The cutoff was 8 Å for Van der Waals forces (the default used by AMBER [73], no cutoff was applied to electrostatic forces (using the Particle Mesh Ewald algorithm, [74]). The equations of motions were integrated with a multiple timestep of 1.25 fs for bonded interactions and 2.5 fs for non-bonded interactions at a temperature of 298 K and a pressure of 1 atm (NPT ensemble) using algorithms described in detail previously [54]. After inspection of the solute RMSD as a function of simulation time, the first 100 picoseconds were considered equilibration time and excluded from further analysis.

The binding energy and SMD studies were performed by running the md_analyzebindingenergy and md_steered macros, respectively.

4. Conclusions

Two A–ring–fused GA series having an indole or N-phenylpyrazole moieties were prepared. These moieties dramatically improved from 6- to 25-fold the PTP1B inhibitory activity of GA. Interestingly, several of the titled compounds exhibited better potency than those of claramine and ursolic acid. However, adding a chlorine atom at the phenyl moiety in both series was found to have a negative impact on the inhibitory activity against PTP1B. Nevertheless, the presence of a trifluoromethyl group at the same position greatly improves this activity. The results regarding the PTP1B inhibitory effect along with the enzyme kinetics studies demonstrated that both 4f and 5f are the most potent non-competitive PTP1B inhibitors with IC50 values = 2.5 and 4.4 µM as well as Ki values = 3.9 and 4.6 µM, respectively. It is worthwhile to mention that 5f is the only compound that has a better inhibitory effect than that of suramin.

The docking simulations performed on PTP1B showed that the newly-synthesized compounds bind preferably to the allosteric binding site with lower binding free energies as well as better scores than that of ursolic acid (non-competitive inhibitor). In addition, these studies displayed that the π-stacking and fluorine (from –CF3) interactions performed by the substituted indole or N-phenylpyrazole moieties with the amino acid residues Phe196, Phe280, Glu276 and Ala189 located inside this enzyme cavity have a positive impact on the binding affinity. The results from MD simulations demonstrated that the binding of 4f at the allosteric binding site stabilizes better the PTP1B in its inactive conformation compared to 5f and ursolic acid. However, both 4f and 5f have a similar binding energy profile. Finally, the SMD study showed that ursolic acid has the slowest dissociation rate from this site, followed by 4f and 5f.

We look forward to expanding the library of these compounds with the purpose of elucidating quantitative structural relationships associated with their PTP1B inhibitory effect. Moreover, further research can be conducted to determine the anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effect in vivo for the titled compounds.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Programa para el Desarrollo Profesional Docente (PRODEP, grant number: UAM–PTC–689), Fortalecimiento y Mantenimiento de Infraestructuras de Investigación de Uso Común y Capacitación Técnica CONACyT (grant number: 317036) and Proyecto de cátedras CONACyT (grant number: 1238) for supporting this research. Moreover, the authors acknowledge Ernesto Sánchez Mendoza for providing the NMR data. Ledy De-la-Cruz-Martínez acknowledges Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) for the master’s degree scholarship awarded (CVU: 1044972).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online. Table with 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts (δ) of compounds 4f and 5f. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of final compounds. Spectra resulting from different NMR experiments (NOESY, COSY, HSQC and HMBC) of compounds 4f and 5f. UPLC–ESI–MS data of final compounds are available.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.-B.; methodology, L.D.-l.-C.-M., C.D.-B., M.G.-A., J.C.P.-F., J.M.G.-A., J.M.T.-V. and J.E.-C.; software, L.D.-l.-C.-M., C.D.-B. and F.C.-B.; formal analysis, L.D.-l.-C.-M., C.D.-B., M.G.-A. and F.C.-B.; investigation, L.D.-l.-C.-M., C.D.-B. and F.C.-B.; resources, F.C.-B., J.P.-V., J.F.P.-E. and O.S.-A.; data curation, L.D.-l.-C.-M., C.D.-B. and F.C.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D.-l.-C.-M., C.D.-B. and M.G.-A.; writing—review and editing, C.D.-B. and F.C.-B.; visualization, F.C.-B.; supervision, F.C.-B.; project administration, F.C.-B.; funding acquisition, F.C.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Programa para el Desarrollo Profesional Docente (PRODEP, grant number: UAM–PTC–689), Fortalecimiento y Mantenimiento de Infraestructuras de Investigación de Uso Común y Capacitación Técnica CONACyT (grant number: 317036) and Proyecto de cátedras CONACyT (grant number: 1238).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds 4a–f as well 5a–f are available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tonks N.K., Diltz C.D., Fischer E.H. Purification of the major protein-tyrosine-phosphatases of human placenta. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:6722–6730. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)68702-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonks N.K. PTP1B: From the sidelines to the front lines! FEBS Lett. 2003;546:140–148. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00603-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picardi P.K., Calegari V.C., de Oliveira Prada P., Contin Moraes J., Araujo E., Gomes Marcondes M.C.C., Ueno M., Carvalheira J.B.C., Velloso L.A., Saad M.J.A. Reduction of hypothalamic protein tyrosine phosphatase improves insulin and leptin resistance in diet-induced obese rats. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3870–3880. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr A.J. Protein tyrosine phosphatases as drug targets: Strategies and challenges of inhibitor development. Future Med. Chem. 2010;2:1563–1576. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vieira M.N., Lyra e Silva N.M., Ferreira S.T., De Felice F.G. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B): A potential target for Alzheimer’s therapy? Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:7. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng C.W., Chen N.F., Chan T.F., Chen W.F. Therapeutic Role of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B in Parkinson’s Disease via Antineuroinflammation and Neuroprotection In Vitro and In Vivo. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020;2020:8814236. doi: 10.1155/2020/8814236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeon Y.-M., Lee S., Kim S., Kwon Y., Kim K., Chung C.G., Lee S., Lee S.B., Kim A.H.-J. Neuroprotective effects of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibition against ER stress-induced toxicity. Mol. Cells. 2017;40:280. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thiebaut P.A., Besnier M., Gomez E., Richard V. Role of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B in cardiovascular diseases. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016;101:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wade F., Belhaj K., Poizat C. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. Heart Fail. Rev. 2018;23:261–272. doi: 10.1007/s10741-018-9676-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen T.D., Schwarzer M., Schrepper A., Amorim P.A., Blum D., Hain C., Faerber G., Haendeler J., Altschmied J., Doenst T. Increased Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B (PTP 1B) Activity and Cardiac Insulin Resistance Precede Mitochondrial and Contractile Dysfunction in Pressure-Overloaded Hearts. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008865. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelsalam S.S., Korashy H.M., Zeidan A., Agouni A. The role of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP)-1B in cardiovascular disease and its interplay with insulin resistance. Biomolecules. 2019;9:286. doi: 10.3390/biom9070286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu M., Liu Z., Liu Y., Zhou X., Sun F., Liu Y., Li L., Hua S., Zhao Y., Gao H., et al. PTP 1B markedly promotes breast cancer progression and is regulated by miR-193a-3p. FEBS J. 2019;286:1136–1153. doi: 10.1111/febs.14724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Q., Wu N., Li X., Guo C., Li C., Jiang B., Wang H., Shi D. Inhibition of PTP1B blocks pancreatic cancer progression by targeting the PKM2/AMPK/mTOC1 pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10 doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2073-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lessard L., Stuible M., Tremblay M.L. The two faces of PTP1B in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2010;1804:613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J., Liu B., Chen X., Su L., Wu P., Wu J., Zhu Z. PTP1B expression contributes to gastric cancer progression. Med. Oncol. 2012;29:948–956. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-9911-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lessard L., Labbé D., Deblois G., Bégin L.R., Hardy S., Mes-Masson A.-M., Saad F., Trotman L.C., Giguère V., Tremblay M.L. PTP1B is an androgen receptor–regulated phosphatase that promotes the progression of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1529–1537. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain H., Green I.R., Abbas G., Adekenov S.M., Hussain W., Ali I. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibitors as potential anti-diabetes agents: Patent review (2015–2018) Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2019;29:689–702. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1655542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang C.S., Liang L.F., Guo Y.W. Natural products possessing protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibitory activity found in the last decades. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012;33:1217–1245. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L.J., Jiang B., Wu N., Wang S.Y., Shi D.Y. Natural and semisynthetic protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibitors as anti-diabetic agents. RSC Adv. 2015;5:48822–48834. doi: 10.1039/C5RA01754H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma H., Kumar P., Deshmukh R.R., Bishayee A., Kumar S. Pentacyclic triterpenes: New tools to fight metabolic syndrome. Phytomedicine. 2018;50:166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verma M., Gupta S.J., Chaudhary A., Garg V.K. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors as antidiabetic agents–A brief review. Bioorg. Chem. 2017;70:267–283. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez-Jiménez A., Rufino-Palomares E.E., Fernández-Gallego N., Ortuño-Costela M.C., Reyes-Zurita F.J., Peragón J., Salguero E.L.G., Mokhtari K., Medina P.P., Lupiáñez J.A. Target molecules in 3T3-L1 adipocytes differentiation are regulated by maslinic acid, a natural triterpene from Olea europaea. Phytomedicine. 2016;23:1301–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mkhwanazi B.N., van Heerden F.R., Mavondo G.A., Mabandla M.V., Musabayane C.T. Triterpene derivative improves the renal function of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: A follow-up study on maslinic acid. Renal Fail. 2019;41:547–554. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2019.1623818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Q.C., Guo T.T., Zhang L., Yu Y., Wang P., Yang J.F., Li Y.X. Synthesis and biological evaluation of oleanolic acid derivatives as PTP1B inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;63:511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian S., Li H., Chen Y., Zhang W., Yang S., Wu Y. Synthesis and biological evaluation of oleanolic acid derivatives as inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1743–1750. doi: 10.1021/np100064m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y.N., Zhang W., Hong D., Shi L., Shen Q., Li J.Y., Li J., Hu L.H. Oleanolic acid and its derivatives: New inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B with cellular activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:8697–8705. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyriakou E., Schmidt S., Dodd G.T., Pfuhlmann K., Simonds S.E., Lenhart D., Geerlof A., Schriever S.C., De Angelis M., Schramm K.-W., et al. Celastrol promotes weight loss in diet-induced obesity by inhibiting the protein tyrosine phosphatases PTP1B and TCPTP in the hypothalamus. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:11144–11157. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfuhlmann K., Schriever S.C., Baumann P., Kabra D.G., Harrison L., Mazibuko-Mbeje S.E., Contreras R.E., Kyriakou E., Simonds S.E., Tiganis T., et al. Celastrol-induced weight loss is driven by hypophagia and independent from UCP1. Diabetes. 2018;67:2456–2465. doi: 10.2337/db18-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Angelis M., Schriever S.C., Kyriakou E., Sattler M., Messias A.C., Schramm K.W., Pfluger P.T. Detection and quantification of the anti-obesity drug celastrol in murine liver and brain. Neurochem. Int. 2020;136:104713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauren D.R., Jensen D.J., Douglas J.A., Follett J.M. Efficient method for determining the glycyrrhizin content of fresh and dried roots, and root extracts, of Glycyrrhiza species. Phytochem. Anal. Int. J. Plant Chem. Biochem. Tech. 2001;12:332–335. doi: 10.1002/pca.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baltina L.A. Chemical modification of glycyrrhizic acid as a route to new bioactive compounds for medicine. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:155–171. doi: 10.2174/0929867033368538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karaoğul E., Parlar P., Parlar H., Alma M.H. Enrichment of the glycyrrhizic acid from licorice roots (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) by isoelectric focused adsorptive bubble chromatography. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2016;2016:7201740. doi: 10.1155/2016/7201740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hussain H., Green I.R., Shamraiz U., Saleem M., Badshah A., Abbas G., Rehman N.U., Irshad M. Therapeutic potential of glycyrrhetinic acids: A patent review (2010–2017) Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2018;28:383–398. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2018.1455828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalaiarasi P., Pugalendi K.V. Antihyperglycemic effect of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, aglycone of glycyrrhizin, on streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009;606:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sen S., Roy M., Chakraborti A.S. Ameliorative effects of glycyrrhizin on streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011;63:287–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y., Yang S., Zhang M., Wang Z., He X., Hou Y., Bai G. Glycyrrhetinic acid improves insulin-response pathway by regulating the balance between the Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways. Nutrients. 2019;11:604. doi: 10.3390/nu11030604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guan M., Liu Q. Application of 18 β-Glycyrrhetinic Acid in Preparation of Medicines for Treating Diseases Related to Lipid Metabolism Disorder. CN201811156633.6A. CN Patent. 2018 Sep 30;

- 38.Na M., Cui L., Min B.S., Bae K., Yoo J.K., Kim B.Y., Oh W.K., Ahn J.S. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitory activity of triterpenes isolated from Astilbe koreana. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3273–3276. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seong S.H., Nguyen D.H., Wagle A., Woo M.H., Jung H.A., Choi J.S. Experimental and computational study to reveal the potential of non-polar constituents from Hizikia fusiformis as dual protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B and α-glucosidase inhibitors. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17:302. doi: 10.3390/md17050302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabuchi M., Imamura S., Kawakami Z., Ikarashi Y., Kase Y. The blood–brain barrier permeability of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, a major metabolite of glycyrrhizin in Glycyrrhiza root, a constituent of the traditional Japanese medicine yokukansan. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012;32:1139–1146. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9839-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizoguchi K., Kanno H., Ikarashi Y., Kase Y. Specific binding and characteristics of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid in rat brain. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bence K.K., Delibegovic M., Xue B., Gorgun C.Z., Hotamisligil G.S., Neel B.G., Kahn B.B. Neuronal PTP1B regulates body weight, adiposity and leptin action. Nat. Med. 2006;12:917–924. doi: 10.1038/nm1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiu W.-W., Shen Q., Yang F., Wang B., Zou H., Li J.-Y., Li J., Tang J. Synthesis and biological evaluation of heterocyclic ring-substituted maslinic acid derivatives as novel inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:6618–6622. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen H.S., Iversen L.F., Jeppesen C.B., Branner S., Norris K., Rasmussen H.B., Møller K.B., Møller N.P.H. 2-(oxalylamino)-benzoic acid is a general, competitive inhibitor of protein-tyrosine phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:7101–7108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiesmann C., Barr K.J., Kung J., Zhu J., Erlanson D.A., Shen W., Fahr B.J., Zhong M., Taylor L., Randal M., et al. Allosteric inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nsmb803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang W., Hong D., Zhou Y., Zhang Y., Shen Q., Li J.-Y., Hu L.-H., Li J. Ursolic acid and its derivative inhibit protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B, enhancing insulin receptor phosphorylation and stimulating glucose uptake. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2006;1760:1505–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qin Z., Pandey N.R., Zhou X., Stewart C.A., Hari A., Huang H., Stewart A., Brunel J.M., Chen H.H. Functional properties of Claramine: A novel PTP1B inhibitor and insulin-mimetic compound. Biochem. Biophys. Res Commun. 2015;458:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carmona S., Brunel J.-M., Bonier R., Sbarra V., Robert S., Borentain P., Lombardo D., Mas E., Gerolami R. A squalamine derivative, NV669, as a novel PTP1B inhibitor: In vitro and in vivo effects on pancreatic and hepatic tumor growth. Oncotarget. 2019;10:6651–6667. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.27286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y.L., Keng Y.F., Zhao Y., Wu L., Zhang Z.Y. Suramin is an active site-directed, reversible, and tight-binding inhibitor of protein-tyrosine phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12281–12287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sakamuri S.S.V.P., Sukapaka M., Prathipati V.K., Nemani H., Putcha U.K., Pothana S., Koppala S.R., Ponday L.R.K., Acharya V., Veetill G.N., et al. Carbenoxolone treatment ameliorated metabolic syndrome in WNIN/Ob obese rats, but induced severe fat loss and glucose intolerance in lean rats. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chaturvedula V.S.P., Yu O., Mao G. Isolation and NMR spectral assignments of 18-glycyrrhetinic acid-3-Od-glucuronide and 18-glycyrrhetinic acid. IOSR J. Pharm. 2014;4 doi: 10.9790/3013-0412-44-48. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baltina L., Kunert O., Fatykhov A., Kondratenko R.M., Spirikhin L., Galin F.Z., Tolstikov G.A., Haslinger E. High-resolution 1 H and 13 C NMR of Glycyrrhizic acid and its esters. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2005;41:432–435. doi: 10.1007/s10600-005-0171-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pollock J., Borkin D., Lund G., Purohit T., Dyguda-Kazimierowicz E., Grembecka J., Cierpicki T. Rational design of orthogonal multipolar interactions with fluorine in protein–Ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:7465–7474. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krieger E., Vriend G. New ways to boost molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2015;36:996–1007. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maier J.A., Martinez C., Kasavajhala K., Wickstrom L., Hauser K.E., Simmerling C. ff14SB: Improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen D.E., Willick D.L., Ruckel J.B., Floriano W.B. Principal component analysis of binding energies for single-point mutants of hT2R16 bound to an agonist correlate with experimental mutant cell response. J. Comput. Biol. 2015;22:37–53. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2014.0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rao G.S., Kondaiah P., Singh S.K., Ravanan P., Sporn M.B. Chemical modifications of natural triterpenes—glycyrrhetinic and boswellic acids: Evaluation of their biological activity. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:11541–11548. doi: 10.1002/chin.200914185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao C., Dai F.-J., Cui H.-W., Peng S.-H., He Y., Wang X., Yi Z.-F., Qiu W.W. Synthesis of novel heterocyclic ring-fused 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives with antitumor and antimetastatic activity. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2014;84:223–233. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diaz-Rojas M., Raja H., Gonzalez-Andrade M., Rivera-Chavez J., Rangel-Grimaldo M., Rivero-Cruz I., Mata R. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors from the fungus Malbranchea albolutea. Phytochemistry. 2021;184:112664. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rangel-Grimaldo M., Macias-Rubalcava M.L., Gonzalez-Andrade M., Raja H., Figueroa M., Mata R. α-Glucosidase and Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B Inhibitors from Malbranchea circinata. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83:675–683. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Copeland R.A. In: Enzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism, and Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Robert A., editor. Volume 291. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY, USA: 2001. p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmidt M.W., Baldridge K.K., Boatz J.A., Elbert S., Gordon M.S., Jensen J.H., Koseki S., Matsunaga N., Nguyen K.A., Su S., et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 1993;14:1347–1363. doi: 10.1002/jcc.540141112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krieger E., Koraimann G., Vriend G. Increasing the precision of comparative models with YASARA NOVA—A self-parameterizing force field. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2002;47:393–402. doi: 10.1002/prot.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Trott O., Olson A. JAutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones G., Willett P., Glen R.C., Leach A.R., Taylor R. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adasme M.F., Linnemann K.L., Bolz S.N., Kaiser F., Salentin S., Haupt V.J., Schroeder M. PLIP 2021: Expanding the scope of the protein-ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salentin S., Schreiber S., Haupt V.J., Adasme M.F., Schroeder M. PLIP: Fully automated protein–ligand interaction profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W443–W447. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021. Dassault Systemes; San Diego, CA, USA: 2021. Version v21.1.0.20298. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Velázquez-Libera J.L., Durán-Verdugo F., Valdés-Jiménez A., Núñez-Vivanco G., Caballero J. LigRMSD: A web server for automatic structure matching and RMSD calculations among identical and similar compounds in protein-ligand docking. Bioinformatics. 2020;36:2912–2914. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang J., Wolf R.M., Caldwell J.W., Kollman P.A., Case D.A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jakalian A., Jack D.B., Bayly C.I. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II. Parameterization and validation. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:1623–1641. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hornak R.V., Abel A., Okur B., Strockbine A., Roitberg C. Simmerling, Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2005;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Essmann U., Perera L., Berkowitz M.L., Darden T., Lee H., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. doi: 10.1063/1.470117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are contained within the article.