Abstract

There is unprecedented increase in low-temperature stress (LTS) during post-heading stages in rice as a consequence of the recent climate changes. Quantifying the effect of LTS on yields is key to unraveling the impact of climatic changes on crop production, and therefore developing corresponding mitigation strategies. The present research was conducted to analyze and quantify the effect of post-heading LTS on rice yields as well as yield and grain filling related parameters. A two-year experiment was conducted during rice growing season of 2018 and 2019 using two Japonica cultivars (Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46) with different low-temperature sensitivities, at four daily minimum/maximum temperature regimes of 21/27 °C (T1), 17/23 °C (T2), 13/19 °C (T3) and 9/15 °C (T4). These temperature treatments were performed for 3 (D1), 6 (D2) or 9 days (D3), at both flowering and grain filling stages. We found LTS for 3 days had no significant effect on grain yield, even when the daily mean temperature was as low as 12 °C. However, LTS of between 6 and 9 days at flowering but not at filling stage significantly reduced grain yield of both cultivars. Comparatively, Huaidao 5 was more cold tolerant than Nanjing 46. LTS at flowering and grain filling stages significantly reduced both maximum and mean grain filling rates. Moreover, LTS prolonged the grain filling duration of both cultivars. Additionally, there was a strong correlation between yield loss and spikelet fertility, spikelet weight at maturity, grain filling duration as well as mean and maximum grain filling rates under post-heading LTS (p < 0.001). Moreover, the effect of post-heading LTS on rice yield can be well quantified by integrating the canopy temperature (CT) based accumulated cold degree days (ACDDCT) with the response surface model. The findings of this research are useful in modeling rice productivity under LTS and for predicting rice productivity under future climates.

Keywords: accumulated cold degree days, canopy temperature, flowering, grain filling, spikelet fertility, response surface model, rice yield

1. Introduction

Almost half of the global population consume rice [1]. Japonica and Indica are two main subspecies of Asian rice (Oryza sativa L.) widely cultivated throughout the world [2]. Low temperature between 12–15 °C can affect rice production [3,4], given its tropical and subtropical origin [5]. Yield losses in rice resulting from low-temperature stress (LTS) are well documented in Japan [6], Korea [7], China [8,9,10,11] and Australia [12]. Tolerance to cold differs among rice cultivars. For instance, Japonica rice from Korea displays greater cold tolerance than most varieties from Russia and China [13]. The cold tolerance property of rice not only depends on origin or subtype, but also on the growth stage as well as duration and intensity of LTS [14,15]. The expected higher frequency and extreme temperature patterns under recent climatic changes are poised to exacerbate the negative impacts of LTS on rice production [16]. The need to evaluate and quantify the effect of LTS on rice yield is motivated by the projected future climate changes and their impact on agricultural production.

Numerous studies have been conducted to identify cold-resistant cultivars, growth stages most sensitive to LTS and mechanisms underlying effects of LTS on rice yields. LTS causes loss of rice yields in several ways [17]. LTS during germination causes seedling death and delayed crop establishment [18], whereas during the vegetative stage, LTS reduces rice yield by reducing rice biomass [15]. LTS during jointing reduces grain yield by decreasing the number of spikelet per panicle [19]. LTS during booting stage induces male sterility and reduces the number of spikelet per panicle [3,20]. During heading and flowering stages, LTS causes poor panicle exertion, which disrupts anther dehiscence and pollination, resulting in spikelet sterility [19,21]. Japonica rice needs much longer grain filling time at daily mean air temperature of 21 °C, and the process may not be completed even in 75 days after flowering at temperatures under 17 °C [22]. The entire rice reproductive process from gamete formation, fertilization and grain development is sensitive to LTS [23], with the last pre-heading and the first post-heading weeks being most sensitive [24]. Extreme low temperature at the flowering and booting stages severely decreases spikelet fertility [25].

However, yield losses due to LTS should be interpreted with caution, having observed significant difference between rice under natural less stressful field conditions and those under controlled conditions with more stringent and intense stress conditions [26]. Therefore, more experiments in chambers with wide temperature variations during key growth stages are needed to effectively assess the impact of LTS on long-term food security. Even though models for quantifying the impact of cold and heat stresses on rice production have been developed [3,27,28,29,30], they rely on the cumulative cold or hot degree days below or above the optimum levels during key growth and development stages [31]. Accumulated cold degree days (ACDD) is one of the simple growth models that has been used in estimating the serious negative effects of low-temperature stress at booting on rice yield in northern Japan [32]. A modified stage-dependent model was developed where ACDD were calculated using water temperature (standing water in the paddy field) under cool climates in describing the effects of LTS at booting in Japonica rice [6]. However, the sensitivity of flowering and grain filling stages to LTS are less defined [15]. Even though the subroutine of the ORYZA model for cold-induced sterility during flowering is empirically derived from the ACDD, it does not compensate for cold-induced sterility in environments with wide diurnal swing temperature [33]. In general, there is need to develop models that can fully describe the above complex relationships, to improve the accuracy of estimating yield losses under extreme temperature stress [34].

The present study was designed to analyze the dynamics of yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters in rice under moderate to extreme post-heading LTS. The impact of post-heading LTS on yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters were also quantified by integrating the response surface model (RSM) with the canopy temperature based accumulated cold degree days (ACDDCT). The findings of this research are useful in estimating rice yield under variable LTS. Accordingly, the models can be used in evaluating the impact of future climate change on rice production, and therefore can inform on corresponding resilient measures.

2. Results

2.1. Effects of Post-Heading LTS on Grain Yield and Related Parameters

There was no significant difference in grain yield and yield related parameters between two experiment seasons. Yield per plant (YPP) and spikelet fertility (SF) were most influenced by low temperature level, and it was duration dependent. Post-heading LTS had no significant effect on thousand grain weight (TGW) and spikelet number per panicle (SNPP). The interaction was highly significant for most two-treatment (temperature level and duration, temperature level and cultivar, temperature level and stage, temperature duration and stage, as well as cultivar and stage) and three-treatment factors (cultivar, stage and temperature level, cultivar, stage and temperature duration, as well as stage, temperature level and duration). The interaction of four or more treatment factors was not significant. Notably, the two cultivars responded to LTS differently (Table S1). For instance, relative to Huaidao 5, the YPP and SF of Nanjing 46 decreased significantly with decreasing temperature level at the flowering stage but not grain filling stage, in a duration dependent manner. As LTS at flowering increased from T2D1 to T4D3, the YPP of Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46 decreased by 6.39% to 38.4% and 0% to 73.6%, respectively. The duration of low temperature significantly influenced the effect of low temperature on yields. Three days duration of LTS had no significant effect on grain yield even when the daily mean temperature was as low as 12 °C (T4D1). However, moderate low temperature level (20 °C) for 9 days (T2D3) at flowering stage significantly reduced grain yields (12.5%) of Nanjing 46. Moreover, the effect of T3D3 at flowering stage on yield damage for Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46 (15.7% and 26.9%) was comparable to that of T4D2 (12.7% and 28.1%), respectively. Similarly, yield loss was directly proportion to the duration of LTS. T4D2 at the flowering stage decreased YPP of Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46 by 16.9% and 27.9%, respectively, whereas T4D3 caused respective 40.8% and 74.2% decrease in YPP of the two varieties (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of low-temperature stress at flowering and grain filling stages on yield and related parameters over the two-year experiment period.

| Cultivar | LTS | Flowering Stage | Grain Filling Stage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF (%) |

TGW (g) |

YPP (g plant−1) |

SNPP | SF (%) |

TGW (g) |

YPP (g plant−1) |

SNPP |

||

| Huaidao 5 | Control | 94.6 a | 29.8 | 17.2 a | 122.1 | 96.5 | 29.5 | 17.7 | 124.9 |

| T2D1 | 96.2a | 31.0 | 18.3 a | 123.0 | 97.3 | 30.5 | 18.7 | 126.0 | |

| T2D2 | 94.6 a | 30.4 | 17.7 a | 123.1 | 96.2 | 29.5 | 18.0 | 126.8 | |

| T2D3 | 92.5 a | 29.8 | 16.9 a | 123.1 | 96.1 | 30.1 | 18.3 | 126.9 | |

| T3D1 | 96.5 a | 30.3 | 17.7 a | 120.9 | 96.3 | 30.2 | 18.2 | 125.6 | |

| T3D2 | 90.7 a | 29.5 | 16.9 a | 125.8 | 95.9 | 30.9 | 17.9 | 121.3 | |

| T3D3 | 78.4 b | 30.7 | 14.5 c | 120.6 | 96.2 | 30.9 | 18.7 | 126.2 | |

| T4D1 | 95.6 a | 30.1 | 17.8 a | 123.4 | 97.7 | 30.4 | 19.2 | 129.2 | |

| T4D2 | 79.9 b | 30.5 | 15.0 bc | 122.5 | 96.4 | 29.9 | 18.4 | 127.4 | |

| T4D3 | 55.6 c | 30.5 | 10.6 d | 125.1 | 95.5 | 29.1 | 17.2 | 123.9 | |

| Statistical Significance | Year (Y) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Temp (T) | ** | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Duration (D) | ** | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Y*T | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Y*D | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| T*D | ** | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Y*T*D | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Nanjing 46 | Control | 91.4 a | 27.3 | 16.7 a | 134 | 94.6 | 26.3 | 16.8 | 134.9 |

| T2D1 | 94.1 a | 26.9 | 16.7 a | 131.8 | 93.4 | 26.4 | 17.0 | 138.0 | |

| T2D2 | 86.8 abc | 26.8 | 16.0 ab | 137.9 | 94.4 | 26.1 | 17.3 | 140.7 | |

| T2D3 | 78.8 cd | 27.2 | 14.6 c | 136.1 | 95 | 26.6 | 17.7 | 139.9 | |

| T3D1 | 94.4 a | 26.9 | 17.3 a | 135.9 | 94.1 | 26 | 16.1 | 131.6 | |

| T3D2 | 82.7 bc | 26.8 | 15.4 ab | 139.2 | 95.3 | 26 | 17.2 | 138.9 | |

| T3D3 | 68.7 de | 26.7 | 12.2 c | 133.8 | 95.7 | 26.1 | 16.5 | 132.3 | |

| T4D1 | 90.1 ab | 26.8 | 16.3 ab | 135.3 | 94.1 | 25.9 | 17.1 | 140.4 | |

| T4D2 | 66.6 e | 27.2 | 12.0 c | 132.0 | 94.7 | 25.3 | 16.5 | 138.0 | |

| T4D3 | 23.9 f | 26.8 | 04.4 d | 137.0 | 94.6 | 25.0 | 16.4 | 138.5 | |

| Statistical | Y | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Significance | T | ** | ns | ** | ns | ns | * | ns | ns |

| D | ** | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Y*T | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Y*D | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| T*D | ** | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Y*T*D | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

Note: The data represents mean values of products or treatments followed by different letters showing significant differences between different treatments. The mean values with similar letters or without letters are statistically non-significant. (SF) spikelet fertility; (TGW) thousand grain weight; (SNPP) spikelet number per panicle; (YPP) yield per plant. T1, T2, T3 and T4 are low temperature levels. The Tmin/Tmax for T1, T2, T3 and T4 were 21/27, 17/23, 13/19 and 9/15 °C, respectively. D1, D2 and D3 represent LTS duration of 3, 6 and 9 days, respectively. T1D2 was the control group. * represents p < 0.05; ** represents p < 0.001, while ns represents p > 0.05.

LTS at the flowering stage reduced yield mainly by inducing spikelet infertility, whereas the little change in YPP from LTS at the grain filling stage was due to a slight decrease in TGW. Decrease in SF was directly proportional to the duration of low temperature at the flowering stage. Notably in this regard, Nanjing 46 was more sensitive to low temperature than Huaidao 5. Particularly, the SF of Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46 decreased by 0–41.2% and 0–73.8%, respectively, under T2D1 to T4D3 at the flowering stage. The SF of Huaidao 5 under T4D2 and T4D3 at flowering decreased from 15.5% to 41.2%, respectively, whereas that of Nanjing 46 under the same conditions deceased from 27.1% to 73.8%, respectively (Table 1).

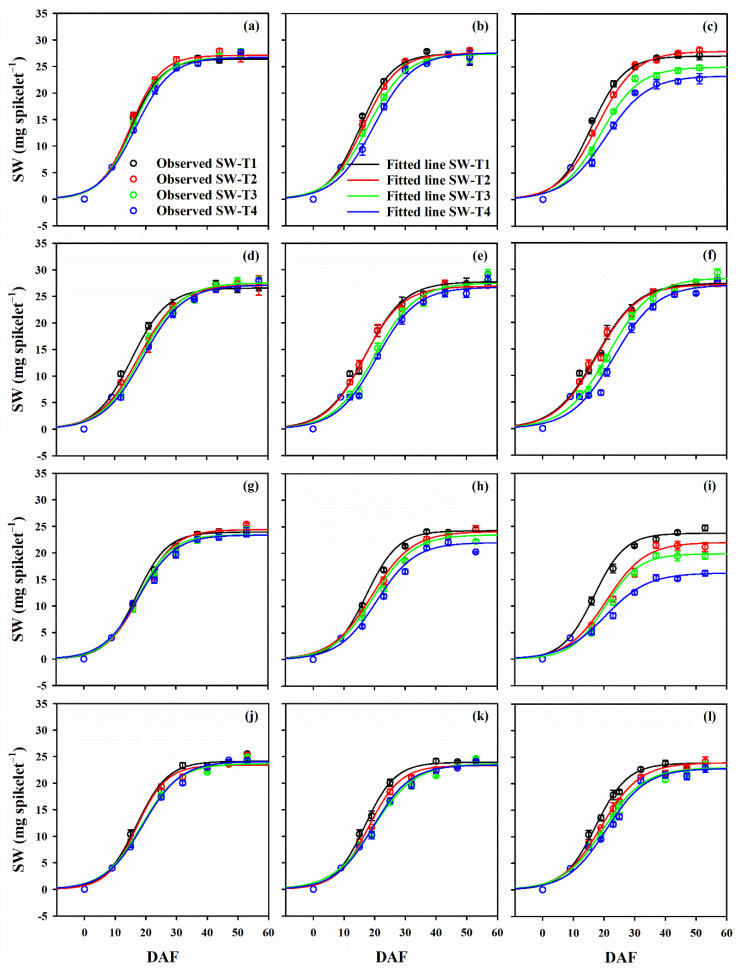

2.2. Effects of Post-Heading LTS on Grain Filling

For controls, grain filling started rapidly within 10–12 days after flowering (DAF) before a lag phase at 20 DAF. The final SW was achieved at 30 and 35 DAF in Huaidao and Nanjing 46, respectively. LTS at flowering delayed grain filling by 2–5 days, however, spikelet weight (SW) increased sharply thereafter (Figure 1). Moreover, LTS at the flowering stage significantly decreased the spikelet weight at maturity (SWm). T3 and T4 during the grain filling stage significantly impaired grain filling in Nanjing 46, and even caused retardation in Huaidao 5. However, the grain filling recovered within 5–10 days post treatment, and there was no significant decrease in SWm at maturity. LTS at flowering and grain filling stages significantly increased time to 50% grain filling (t50) and slightly increased the steepness of curve (b) in both cultivars. LTS at these stages delayed grain filling duration from flowering to maturity (D) by 5–12 days in both cultivars. LTS decreased the maximum and mean grain filling rates (Rmax and Rmean) both at T3 and T4 for 6 and 9 days duration, and this decrease was more severe under LTS at flowering stage (Table 2).

Figure 1.

The sigmoid relationship of days after flowering (DAF) with spikelet weight (SW) in Huaidao 5 (capital letters panels) and Nanjing 46 (small letters panels) under low-temperature stress (LTS) at the flowering stage (a–c) and (g–i) grain filling stage (d–f) and (i–l) stages. The Tmin/Tmax at T1, T2, T3 and T4 were 21/27, 17/23, 13/19 and 9/15 °C, respectively. Graph (a,d,g,j), (b,e,h,k) and (c,f,i,l) represent LTS durations of 3, 6 and 9 days, respectively. Bars on each symbol show the standard error of means. Observed values of SWm were fitted against DAF using regression analysis.

Table 2.

The effect of post-heading low-temperature stress (LTS) on grain filling related parameters.

| Cultivar | Stage | Treatment | SWm (mg spike−1) |

B | t50 (d) |

p Value | R2 | D (d) | Rmean (mg spike−1 d−1) |

Rmax (mg spike−1 d−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huaidao 5 | Flowering | Control | 27.4 | 5.2 | 15.4 | <0.0001 | 0.981 | 31.1 | 0.88 | 1.32 |

| T2D1 | 27.1 | 5.0 | 15.0 | <0.0001 | 0.976 | 30.0 | 0.90 | 1.36 | ||

| T2D2 | 27.5 | 5.6 | 16.3 | <0.0001 | 0.983 | 33.1 | 0.83 | 1.23 | ||

| T2D3 | 27.9 | 6.2 | 17.8 | <0.0001 | 0.987 | 36.4 | 0.77 | 1.13 | ||

| T3D1 | 26.7 | 5.3 | 15.6 | <0.0001 | 0.981 | 31.3 | 0.85 | 1.26 | ||

| T3D2 | 27.4 | 6.2 | 17.7 | <0.0001 | 0.986 | 36.4 | 0.75 | 1.10 | ||

| T3D3 | 24.9 | 6.3 | 18.8 | <0.0001 | 0.973 | 37.6 | 0.66 | 0.99 | ||

| T4D1 | 26.7 | 5.8 | 16.6 | <0.0001 | 0.980 | 33.9 | 0.79 | 1.15 | ||

| T4D2 | 27.6 | 6.4 | 19.7 | <0.0001 | 0.975 | 39.0 | 0.71 | 1.08 | ||

| T4D3 | 23.3 | 6.8 | 20.3 | <0.0001 | 0.951 | 40.8 | 0.57 | 0.86 | ||

| Grain Filling | Control | 27.8 | 6.4 | 17.0 | <0.0001 | 0.957 | 36.3 | 0.77 | 1.09 | |

| T2D1 | 27.2 | 6.5 | 17.9 | <0.0001 | 0.971 | 37.4 | 0.73 | 1.05 | ||

| T2D2 | 26.9 | 6.2 | 16.7 | <0.0001 | 0.974 | 35.2 | 0.76 | 1.08 | ||

| T2D3 | 27.2 | 6.7 | 17.6 | <0.0001 | 0.965 | 37.7 | 0.72 | 1.01 | ||

| T3D1 | 27.6 | 6.6 | 18.7 | <0.0001 | 0.969 | 38.4 | 0.72 | 1.05 | ||

| T3D2 | 27.5 | 6.7 | 20.1 | <0.0001 | 0.970 | 40.2 | 0.68 | 1.03 | ||

| T3D3 | 28.4 | 7.1 | 21.5 | <0.0001 | 0.976 | 42.7 | 0.67 | 1.00 | ||

| T4D1 | 27.1 | 6.5 | 19.3 | <0.0001 | 0.986 | 38.9 | 0.70 | 1.04 | ||

| T4D2 | 26.7 | 6.5 | 20.7 | <0.0001 | 0.972 | 40.2 | 0.66 | 1.03 | ||

| T4D3 | 27.1 | 7.0 | 23.2 | <0.0001 | 0.969 | 44.2 | 0.61 | 0.97 | ||

| Nanjing 46 | Flowering | Control | 24.3 | 5.2 | 17.3 | <0.0001 | 0.983 | 32.9 | 0.74 | 1.17 |

| T2D1 | 24.4 | 5.5 | 18.4 | <0.0001 | 0.979 | 35.0 | 0.70 | 1.11 | ||

| T2D2 | 24.1 | 6.6 | 19.1 | <0.0001 | 0.965 | 38.8 | 0.62 | 0.91 | ||

| T2D3 | 21.9 | 6.3 | 20.5 | <0.0001 | 0.936 | 39.8 | 0.55 | 0.87 | ||

| T3D1 | 23.4 | 5.4 | 17.6 | <0.0001 | 0.977 | 33.8 | 0.69 | 1.08 | ||

| T3D2 | 23.5 | 6.5 | 19.6 | <0.0001 | 0.971 | 39.1 | 0.60 | 0.90 | ||

| T3D3 | 19.8 | 5.5 | 20.3 | <0.0001 | 0.939 | 37.0 | 0.54 | 0.90 | ||

| T4D1 | 23.3 | 5.9 | 17.9 | <0.0001 | 0.975 | 35.4 | 0.66 | 0.99 | ||

| T4D2 | 22.0 | 6.3 | 20.7 | <0.0001 | 0.971 | 39.5 | 0.56 | 0.87 | ||

| T4D3 | 16.2 | 6.9 | 20.8 | <0.0001 | 0.951 | 41.3 | 0.39 | 0.59 | ||

| Grain Filling | Control | 23.9 | 5.0 | 16.8 | <0.0001 | 0.978 | 31.6 | 0.76 | 1.20 | |

| T2D1 | 23.4 | 4.9 | 17.0 | <0.0001 | 0.976 | 31.6 | 0.74 | 1.19 | ||

| T2D2 | 23.3 | 5.3 | 17.9 | <0.0001 | 0.981 | 33.7 | 0.69 | 1.10 | ||

| T2D3 | 23.9 | 6.3 | 19.2 | <0.0001 | 0.964 | 38.1 | 0.63 | 0.95 | ||

| T3D1 | 23.7 | 6.1 | 18.4 | <0.0001 | 0.983 | 36.6 | 0.65 | 0.97 | ||

| T3D2 | 23.7 | 6.8 | 19.4 | <0.0001 | 0.985 | 39.9 | 0.59 | 0.87 | ||

| T3D3 | 23.0 | 6.6 | 19.8 | <0.0001 | 0.964 | 39.6 | 0.58 | 0.87 | ||

| T4D1 | 24.1 | 6.1 | 18.9 | <0.0001 | 0.981 | 37.3 | 0.65 | 0.99 | ||

| T4D2 | 23.4 | 6.1 | 19.6 | <0.0001 | 0.978 | 37.7 | 0.62 | 0.96 | ||

| T4D3 | 22.8 | 6.5 | 20.8 | <0.0001 | 0.961 | 40.2 | 0.57 | 0.88 |

Note: T1, T2, T3 and T4 are temperature levels. The Tmin/Tmax of T1, T2, T3 and T4 were 21/27, 17/23, 13/19 and 9/15 °C, respectively. D1, D2 and D3 represent low-temperature stress duration of 3, 6 and 9 days, respectively. T1D2 was the control group. SWm: the spikelet weight at maturity; b: the shape or steepness of the sigmoid curve; t50: days from flowering to 50% grain filling; (D) total days from flowering to 95% SWm; Rmean: the mean grain filling rate; (Rmax) the maximum grain filling rate.

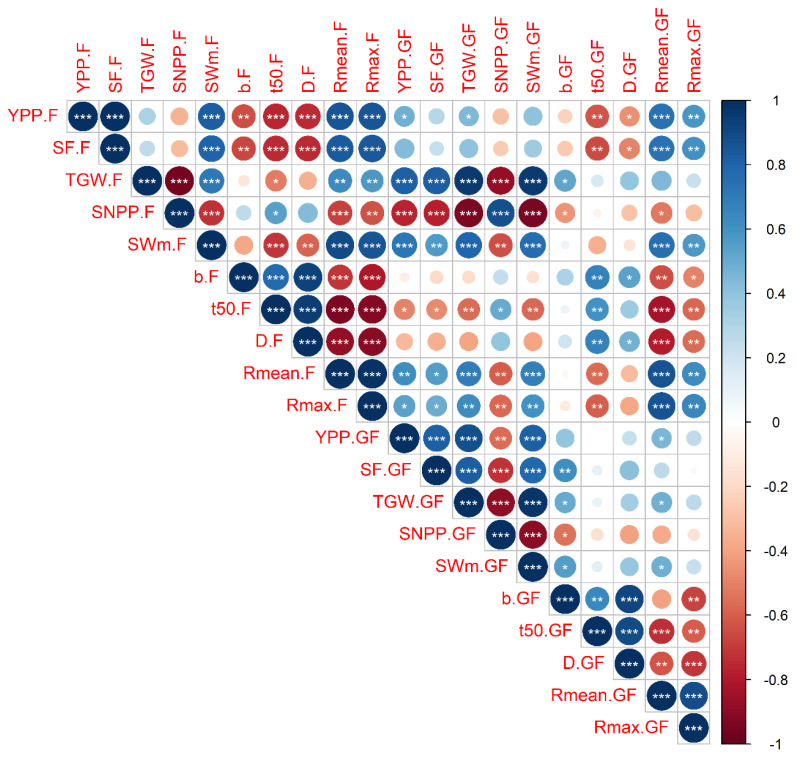

2.3. The Correlation between Yield as Well as Yield and Grain Filling Related Parameters

We found a positive correlation between YPP and SF (p < 0.001), spikelet weight at maturity (SWm) (p < 0.001) and mean grain filling rate (Rmean) (p < 0.001) under LTS at both flowering and grain filling stages. In addition, under LTS at flowering stage, YPP positively correlated with the maximum grain filling rate (Rmax) but negatively correlated with the steepness of curve (b) (p < 0.01), days from flowering to 95% SWm (D) (p < 0.001) and days from flowering to 50% grain filling (t50) (p < 0.001). Additionally, under LTS at the grain filling stage, YPP positively correlated with thousand grain weight (TGW) (p < 0.001), but negatively correlated with spikelet number per panicle (SNPP) (p < 0.01). The highly positive correlation of decreasing SF with SWm (p < 0.001) under LTS at flowering stage was due to a greater number of empty spikelet and ultimately causing decreased spikelet weight (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Pearson correlation matrix between yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters under low-temperature stress at flowering (F) and grain filling (GF) stages. (YPP) yield per plant; (SF) spikelet fertility; (TGW) thousand grain weight; (SNPP) spikelet number per panicle; (SWm) spikelet weight at maturity; (b) the shape or steepness of the sigmoid curve; (t50) days from flowering to 50% grain filling; (D) days from flowering to 95% (SWm) (Rmean) grain filling rate; (Rmax) maximum grain filling rate. *, ** and *** represent the significant correlation at p < 0.05, p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively.

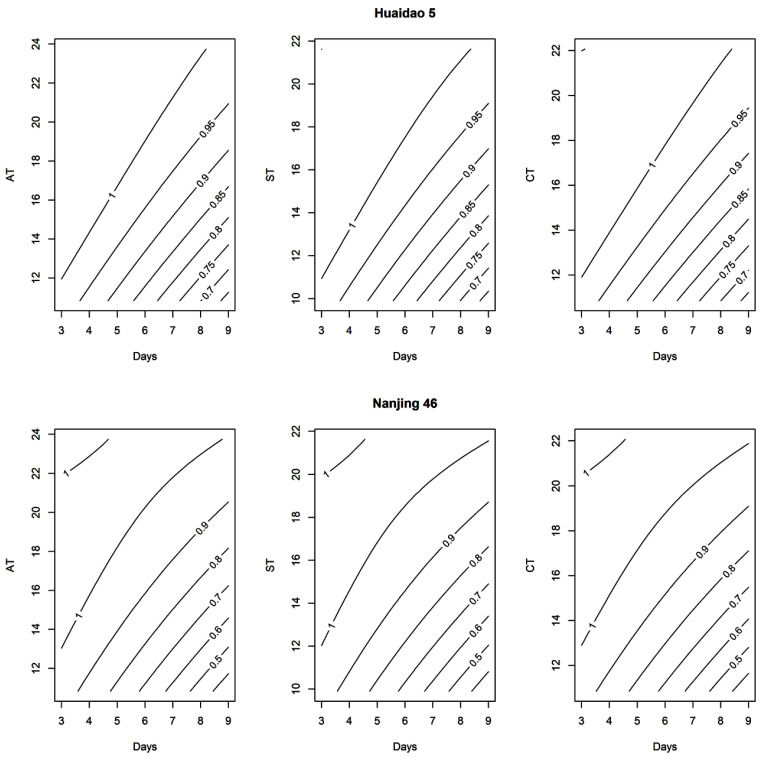

2.4. Response Surface Model for the Association between LTS and Grain Yields as Well as Yield Related Parameters

The relative change in YPP with decreasing AT, ST and CT under increasing LTS duration perfectly fitted in the RSM (Table 3). The 10–30% decrease in YPP of Huaidao 5 was observed at 18–12 °C (AT), 16–11 °C (ST) and 17–12 °C (CT) with 9 days duration at flowering, while same decrease in YPP of Nanjing 46 was observed at 20–16 °C (AT), 18–14 °C (ST) and 18–15 °C (CT) with same LTS duration at flowering (Figure 3). Moreover, given that the effect of LTS on yield was most influenced by CT than AT and ST, we quantified the effects of LTS on yield with CT as well as on yield and grain filling related parameters. The coefficient d of RSM was highly significant (p < 0.001) for most of the parameters (YPP, SF, SWm, t50, Rmax, Rmean and D) in both varieties (Table S2), which confirmed the strong interaction of LTS duration with low temperature level. This phenomenon is depicted in contour plots for the effect of post-heading LTS on yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters in Figures S1–S3.

Table 3.

Parameters of response surface model (RSM) for the relationship of low air temperature (AT), soil temperature (ST) and canopy temperature (CT) with grain yield of Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46 at flowering stage under varied low-temperature stress.

| Cultivar | Air Temperature (AT) |

Soil Temperature (ST) |

Canopy Temperature (CT) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Parameters | Estimate | Significance | Estimate | Significance | Estimate | Significance | |

| Huaidao 5 | a | 0.8599 | 0.0038 ** | 0.8775 | 0.0036 ** | 0.7767 | 0.0146 * |

| b | −0.0772 | 0.0491 * | −0.0787 | 0.0501 | −0.0845 | 0.0499 * | |

| c | 0.0363 | 0.105 | 0.0377 | 0.1201 | 0.0493 | 0.0935 | |

| d | 0.0044 | 0.0019 ** | 0.0049 | 0.0021 ** | 0.0051 | 0.0028 ** | |

| e | −0.0024 | 0.3439 | −0.0024 | 0.3534 | −0.0024 | 0.3757 | |

| f | −0.0014 | 0.0395 * | −0.0016 | 0.0436 * | −0.0019 | 0.0388 * | |

| R2 | 0.9601 | 0.9584 | 0.954 | ||||

| Nanjing 46 | a | 0.8135 | 0.0573 | 0.8395 | 0.0364* | 0.6942 | 0.1168 |

| b | −0.1383 | 0.0542 | −0.1414 | 0.0372* | −0.1531 | 0.0365 * | |

| c | 0.0534 | 0.1797 | 0.0552 | 0.1586 | 0.0725 | 0.1273 | |

| d | 0.0085 | 0.0015 ** | 0.0095 | 0.0009 *** | 0.0099 | 0.0012 ** | |

| e | −0.0047 | 0.3106 | −0.0047 | 0.2707 | −0.0047 | 0.2943 | |

| f | −0.0023 | 0.0597 | −0.0026 | 0.045 * | −0.0031 | 0.0426 * | |

| R2 | 0.9183 | 0.9319 | 0.9241 |

*** represents p < 0.001; ** represents p < 0.01; * represents p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Contour plots for relative change in yield per plant (YPP) under decreasing low air temperature (AT), soil temperature (ST) and canopy temperature (CT) with increasing low-temperature stress (LTS) duration at flowering stage in Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46.

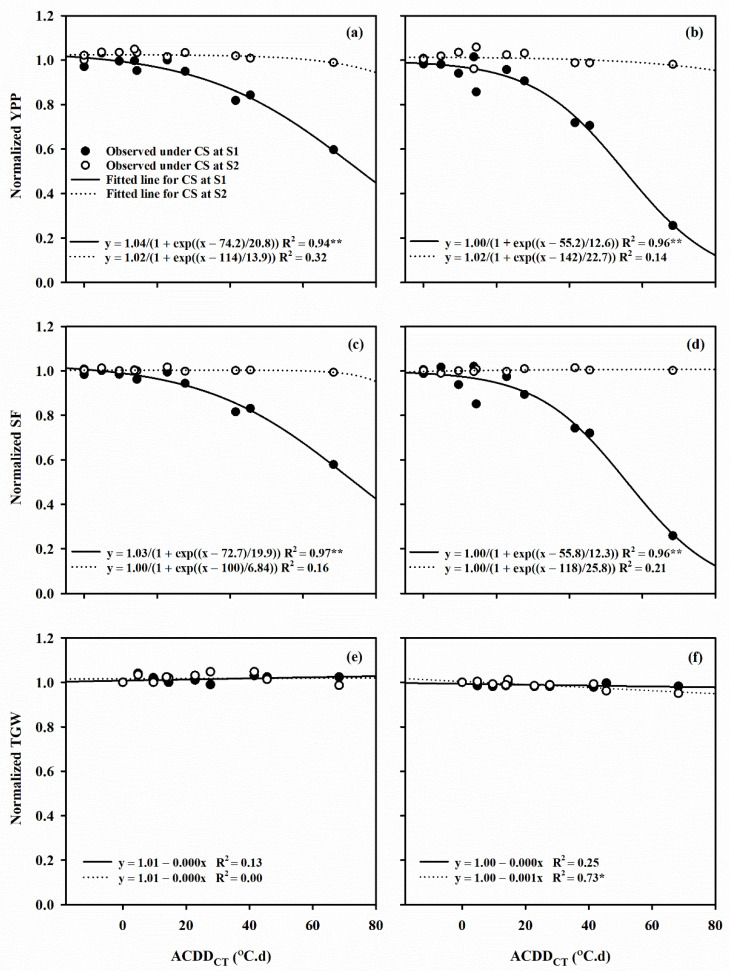

2.5. Quantitative Effects of Post-Heading LTS on Yield and Related Parameters

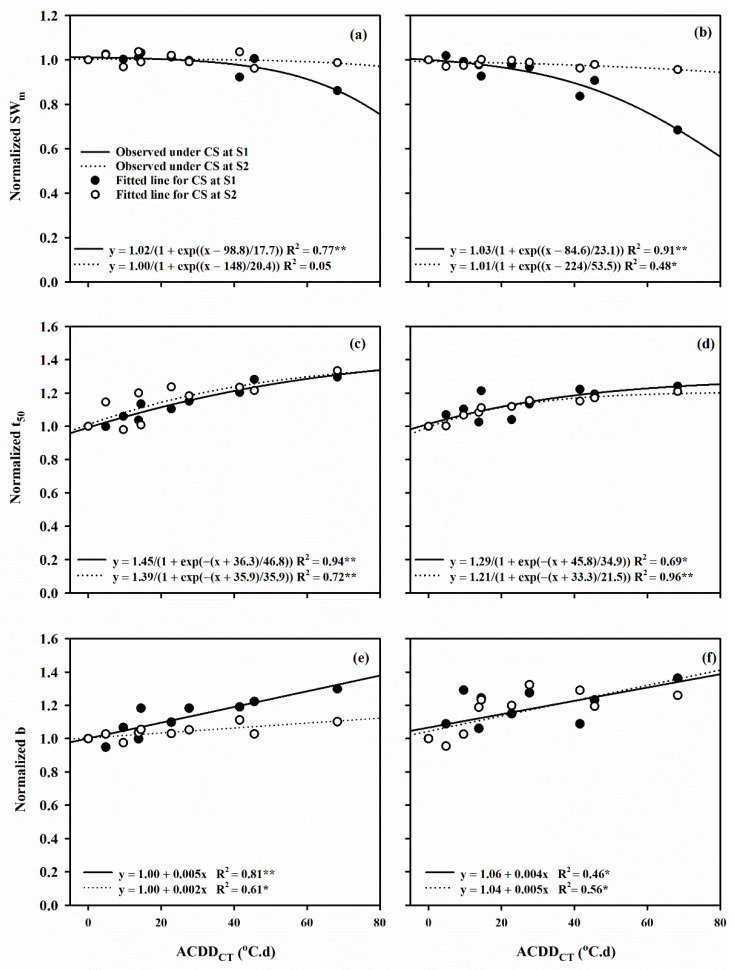

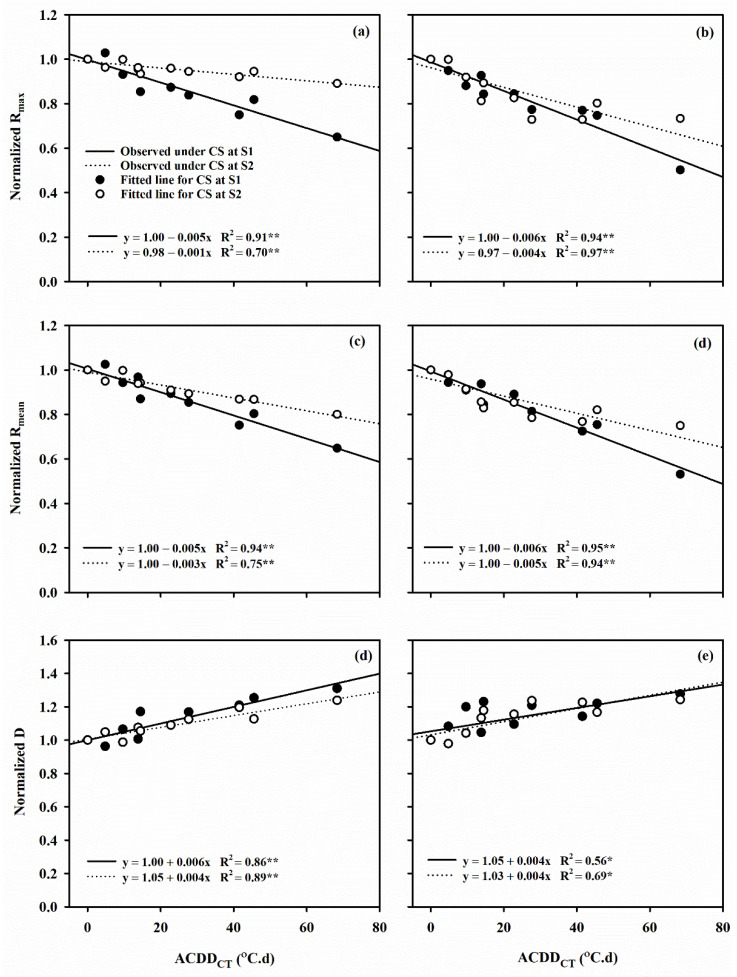

The relationship between normalized YPP, SF, SWm and t50 and ACDDCT perfectly fitted into the sigmoid function: y = a/1 − exp ((x − x0)/b). Under LTS at flowering stage, the 50% reduction in YPP was caused by an ACDDCT of 74.2 and 55.2 °C.d, in SF by 72.7 and 55.8 °C, and in SWm by 98.8 and 84.6 °C.d in Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46, respectively (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Normalized b, Rmean, Rmax and D with ACDDCT under post-heading LTS displayed a linear relationship (y = a + bx) for both cultivars. A 1 °C.d increase in ACDDCT at flowering decreased the Rmean of Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46 by 0.5% and 0.3%, respectively, where similar conditions at grain filling stages resulted in a 0.6% and 0.5% increase in the Rmean of Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46, respectively. On the other hand, a 1 °C.d increase in ACDDCT at flowering and grain filling stages resulted in 0.5% and 0.1% decrease in Rmax of Huaidao 5 and 0.6% and 0.4% decrease in Rmax of Nanjing 46, respectively. Additionally, a 1 °C.d ACDDCT increase at flowering stage resulted in a linear increase of 0.6% and 0.4% in D of Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46, respectively. At the grain filling stage, a 1 °C.d ACDDCT increased the D by 0.4% for both Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46 (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

The relationship between the change in canopy temperature based accumulated cold degree days (ACDDCT) and the relative change in (a,b) yield per plant (YPP), (c,d) spikelet fertility (SF), (e,f) thousand grain weight (TGW) in Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46, respectively. (S1) flowering stage; (S2) grain filling stage. Capital letters represent Huaidao 5 whereas the small letters represent Nanjing 46. ** represents p < 0.01; * represents p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

The relationship between the change in canopy temperature based accumulated cold degree days (ACDDCT) and the relative change in (a,b) spikelet weight at maturity (SWm), (c,d) days from flowering to 50% grain filling (t50), (e,f) shape or steepness of curve (b) in Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46, respectively. (S1) Flowering stage; (S2) grain filling stage. Capital letters represent Huaidao 5 whereas the small letters represent Nanjing 46. ** represents p < 0.01; * represents p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

The relationship between the change in canopy temperature based accumulated cold degree days (ACDDCT) and the relative change in (a,b) maximum filling rate (Rmax), (c,d) mean filling rate (Rmean) and (e,f) total days from flowering to 95% SWm (D) in Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46, respectively. (S1) Flowering stage; (S2) grain filling stage. Capital letters represent Huaidao 5 whereas the small letters represent Nanjing 46. ** represents p < 0.01; * represents p < 0.05).

3. Discussion

3.1. Effect of Post-Heading LTS on Yields and Related Parameters in Rice

The limiting effect of prolonged low temperature on yield has been widely reported [21,23,25,35]. Herein, we found short LTS of low temperature between 12 and 20 °C for 3 days had no significant effect on yields of both rice varieties, in contrast, the lethal effects of short-term post-heading heat stress on yield has been reported in Japonica rice [30,36]. However, longer LTS of 6 and 9 days at the flowering stage significantly decreased the SF or YPP of both rice varieties. We found T3D3 with less ACDDCT caused greater yield loss than T4D2 with more ACDDCT, underling the significant negative effect of low temperature duration on yields as previously reported by [23,35]. Additionally, we found LTS at the flowering stage resulted in greater loss than at the grain filling stage. LTS at flowering mainly induced spikelet infertility, consistent with previous findings [21,24]. Flowering is one of the most critical stages in rice production. LTS affects critical events such as anthesis, anther dehiscence, pollination and fertilization [23]. Anthesis is highly sensitive to LTS, which explains high spikelet infertility under prolonged low-temperature stress. Comparatively, Nanjing 46 with longer flowering period was more sensitive to LTS at the flowering stage than Huaidao 5 with shorter flowering period. Fast germination of pollen is the cold tolerance characteristics in cultivars with shorter flowering period [37]. Varieties with short to medium grain length, typically recommended for cold regions, were found to be more tolerant to low temperatures but more sensitive to high temperatures, in comparison to cultivars with long grain length [31]. High anther dehiscence increases the rate of pollination at the flowering stage in cold tolerant genotypes, thus reduces spikelet sterility [38].

The flowering stage of Japonica cultivars usually lasts approximately 9 days [36]. Therefore, LTS after flowering or during grain filling only moderately influence rice yield. However, the effect of LTS at the grain filling stage cannot be ignored because low daily temperature substantially slows growth. Low temperatures of 21 °C prolonged the grain filling stage of Japonica rice, and in some instances, the process could not complete in 75 days at daily mean temperature of 17 °C [22]. Low temperature results in thermal retardation or permanently impairs critical growth and developmental processes, thus reducing yields [19]. In this study, we found 12–22 °C temperatures only slightly reduced final grain weight of Nanjing 46 and Huaidao 5 at maturity, consistent with previous finding [39]. LTS at the flowering stage resulted in significantly low SW because it disrupted filling of spikelet. In fact, SF positively correlated with SW (p < 0.001). LTS at both flowering and grain filling stages substantially decreased the mean and maximum grain filling rates (Rmean and Rmax) in both Nanjing 46 and Huaidao 5, attributed to thermal retardation [19]. In the present study, we found LTS for 3–9 days significantly slowed down or stopped altogether grain filling process. However, the process resumed within 5–10 days in ambient growth conditions.

3.2. Quantification of Post-Heading LTS Effects on Rice Yield

Rice yields are most affected by length of low temperature period [39]. Quantification of crop yield potential under changing climate condition typically rely on crop models, which are lacking in most cases due to a lack of field data [33]. Temperature sensitivity model may be key in accurately predicting the phenological responses to climate change [40]. At the same time, the impact of extreme temperature duration on yield needs to be factored in the model [41]. In addition, it is difficult to predict sterility because canopy temperature may differ from air temperature due to transpiration cooling effect [42]. The temperature in the panicles would be more significant than air temperature because the panicle is more sensitive to temperature than the other plant organs [30,32]. Herein, air temperature, canopy surface temperature and soil temperature were measured daily. We found the canopy surface temperature was more comparable to the temperature of panicles during post-heading stages. In addition, diurnal variation of canopy surface temperature was lower than that of air temperature in phytotron chambers with T1 and T2, but the difference was smaller at T3 and T4. Moreover, the greater difference between canopy and air temperature is mainly observed during midday at full sunshine [43]. We found canopy surface temperature can better quantify the effect of LTS on yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters than soil and air temperatures.

In this study, by integrating the RSM with the canopy temperature based accumulated cold degree days (ACCDCT), we perfectly described (R2 > 0.90) the relative change in YPP, SF, SWm, t50, Rmean and Rmax under varied daily mean CT and LTS duration for both cultivars, which considered the interaction between low temperature and duration. The logistic regression function described the exponential relationship of the relative change in SF, YPP, SWm and t50 to ACDDCT (R2 > 0.90) as previously reported [6,44]. Even though the ORYZA model for cold-induced sterility during flowering is also empirically derived from ACDDCT, it cannot quantify the cold-induced sterility in environments with large variation in diurnal temperature [33]. Notably in this study, we observed that even though T4D1 has greater ACCDCT (23 °C.d) than T2D3 (15 °C.d), T2D3 caused greater impact on SF and YPP than T4D1, this observation can be well estimated by integrating the RSM with the ACCD, but still needs to be tested in rice growth models with more independent dataset from wider environments in the near future.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Crop Husbandry and Experimental Design

Controlled-environment sunlit phytotron experiments were conducted in Rugao (120.33° E, 32.23° N), Jiangsu Province, China, between 2018 and 2019 using two Japonica rice cultivars (Huaidao-5 with high resistance to cold stress and Nanjing 46 with low resistance to cold stress). Seedlings at three-leaf stage were transplanted into plastic pots (diameter 28 cm and height 25 cm) filled with 15 kg soil. The planting density was 3 hills per pot (2 seedlings per hill). The pots were grown under ambient weather conditions before LTS treatment. Basal fertilizer at the rate of 1.5 g N, 1.5 g P2O5 and 2 g K2O per pot was applied before transplantation. Supplemental N was top-dressed at mid-tillering and jointing stages at the rate of 0.3 g N and 1.2 g N per pot, respectively. The pots were kept flooded until one week before harvesting. Watering at the late active tillering stage was stopped to ensure efficient tillering. Weeds were removed manually, whereas pest and diseases were controlled using pesticides. LTS was designed at four temperature levels (Tmin/Tmax: 21/27 °C, 17/23 °C, 13/19 °C, and 9/15 °C) and three temperature durations (3, 6 and 9 days), at flowering and grain filling stages. The experiments were performed in four separate phytotrons. The post-heading LTS treatments are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of the post-heading low-temperature stress treatments.

| Cultivar | Stage | Temperature (Tmin/Tmax) (°C) | Duration (days) | Start of Treatment | End of Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huaidao 5 | Flowering | T1 (21/27), T2 (17/23), T3 (13/19) and T4 (09/15) |

D1 (3), D2 (6) and D3 (9) |

08/23 in 2018 08/26 in 2019 |

09/01 in 2018 09/04 in 2019 |

| Grain Filling | 09/02 in 2018 09/08 in 2019 |

09/11 in 2018 09/17 in 2019 |

|||

| Nanjing 46 | Flowering | 09/08 in 2018 09/12 in 2019 |

09/17 in 2018 09/21 in 2019 |

||

| Grain Filling | 09/21 in 2018 09/23 in 2019 |

09/30 in 2018 10/02 in 2019 |

Note: T is the temperature level; D is the stress duration; Tmin is the daily minimum temperature; Tmax: daily maximum temperature.

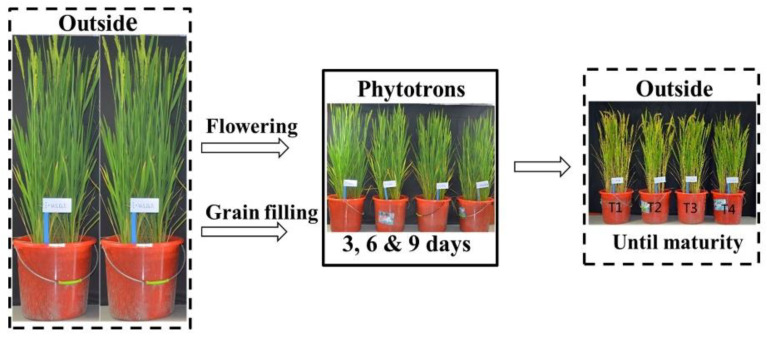

Pots with homogenous tiller number (primary + secondary) were transferred into phytotrons (L × W × H: 3.4 m × 3.2 m × 2.8 m) when 50% of panicles of each pot started flowering (flowering stage). Another set of pots was transferred into the same phytotrons 12 days after start of flowering (grain filling stage) (Figure 7). Each treatment was performed in triplicate and the treatments were completely randomized. At the end of respective treatment durations, the pots were labeled, removed from chambers and maintained under ambient conditions until maturity.

Figure 7.

Pictorial view of the experiment design. T1, T2, T3 and T4 are temperature levels. The Tmin/Tmax of T1, T2, T3 and T4 were 21/27, 17/23, 13/19 and 9/15 °C, respectively.

4.2. Ambient and Phytotron Environment

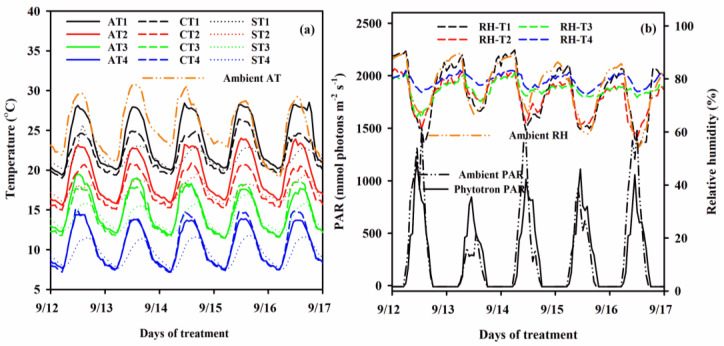

Air temperature (AT) (°C), soil temperature (ST) (°C) and relative humidity (RH) (%) in the phytotrons were monitored at 10 min interval using a VP-4 sensor from METER Group, Inc. (Washington, DC, USA). The canopy surface temperature (CT, °C) and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR, μmol photons m−2 s−1) were also measured at 10 min interval using an SI-111 infrared radiometer, Apogee Instruments Inc (Logan, UT, USA) and QSO-S PAR Photon Flux sensor (Washington, DC, USA), respectively. The sensors were installed as previously described [36,45]. Diurnal AT, ST, CT, RH and PAR changes under the four temperature levels are shown in Figure 1. The CT and ST were lower than ATs. However, in T3 and T4 chambers with 6 and 9 days durations, the CT was slightly higher than AT. At T1, T2, T3 and T4, the daily average ATs were 23.8, 19.2, 14.8 and 11.2 °C, respectively. The STs were 21.6, 17.4, 14.1 and 9.9 °C, respectively, whereas the CTs were 22.2, 17.5, 14.1 and 11.1 °C, respectively (Figure 8a). The daily average PAR in chambers were about 700 μmol photons m−2 s−1 and 400 μmol photons m−2 s−1 on sunny and cloudy days, respectively. The daytime RH was about 75% and 65% at T3/T4 and T1/T2, respectively (Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

The (a) diurnal air (solid lines), canopy (broken lines) and soil temperatures (dotted lines) and (b) relative humidity (RH) (broken lines) and incident photosynthetically active radiations (PAR) (solid line) during low temperature treatment episodes in the phytotrons. Double dotted lines represent the ambient AT, PAR and RH of the same days.

4.3. Yield as Well as Yield and Grain FillingRelated Parameters

Panicles were collected every 7 days till maturity and were placed in the oven at 80 °C to achieve a constant dry weight. The panicles were divided into three parts (upper, middle and lower), with 100 spikelets picked randomly from each part, weighed and averaged for spikelet weight (SW, mg spikelet−1). Yield per plant (YPP; g plant−1) and yield components as spikelet fertility (SF%), spikelet number per panicle (SNPP) and thousand-grain weight (TGW; g) were calculated after harvesting at physiological maturity (3 pots per treatment), as previously described [30].

The dynamics of SW against days after flowering (DAF) was described using Equation (1):

| (1) |

where y is the graph of SW against DAF (x), a is the estimated SW at maturity (SWm; mg spikelet−1), x0 is the estimated t50, the time in days when achieving 50% weight of SWm, b is the equation coefficient which determines the shape or steepness of curve [30,46].The maximum grain filling rate (Rmax; mg spike−1 d−1), the mean grain filling rate (Rmean; mg spike−1 d−1) and the total days from flowering to 95% SWm (D; d) under each treatment were calculated based on estimates derived from Equation (1), as described in Equations (2) and (3):

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

4.4. Response Surface Model

Relative grain yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters were calculated by dividing the treatment value with respective control value (T1 treatment). The relative changes in grain yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters were fitted against decreasing low temperature level and increasing low temperature duration using RSM [47] as Equation (5):

| (5) |

where y is the dependent variable (relative yield, as well as yield related and grain filling related parameters), x1 = LTS duration (3, 6 and 9 days) in each treatment and x2 = daily average air (AT), or soil (ST) or canopy (CT) temperatures (independent variables), while a, b, c, d, e and f are the coefficients of RSM which were obtained after fitting the observed values of y, x1 and x2 on the above Equation (5).

4.5. Quantification of the Effect of Post-Heading LTS on Yields and Related Parameters

The effect of post-heading LTS on yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters were derived using CT-based accumulated cold degree days (ACDDCT) as previously described [48]:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

where CDDi (°C.d) is the average hourly cold degree day at ith day under LTS treatment, CDt (°C.d) is the hourly cold degree day at t hour of a day, and CTt (°C) is hourly canopy temperature at t hour of a day. CTh is the daily average lowest canopy temperature which reduces grain yield by 10% [15]. In this research, CTh was estimated by analyzing the yield response to decreasing canopy low temperature levels and increasing low temperature duration on RSM in equation (5) and was set as 17.9 °C.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Two years of experimental data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA using SigmaPlot Version 14.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA) to estimate the effects of low temperature treatment on grain yield and yield components. The significant differences between treatments were identified at the 0.05 and 0.001 probability level (p) by Tukey’s test. The dynamics of SW against days after flowering (DAF) were fitted on 3 parameters sigmoid function using non-linear regression analysis in SigmaPlot Version 14.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). Furthermore, the association between yield or yield related parameters and grain filling related parameters was assessed based on Pearson correlation analysis using the ‘corrplot’ package in R software V. 4.0.8. Response surface analysis was conducted to assess the effects of low temperature level and duration on yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters using ‘rsm’ package in R software, V. 4.0.8. The effects of LTS on yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters were demonstrated using line and contour graphs.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found that low temperature at the flowering and grain filling stages reduced rice yield. Huaidao 5 is an early-maturing cultivar that is more tolerant to post-heading LTS, relative to late-maturing Nanjing 46. Yields of Huaidao 5 and Nanjing 46 are both significantly influenced when canopy temperatures are lower than 17.1 and 18.6 °C, respectively. Short LTS with 3 days has no significant impact on rice yields, even if the temperature was as low as 12 °C. Contrarily, LTS of 6 to 9 days at the flowering stage severely decreased YPP, SF, SWm, Rmax and Rmean but increased t50 and D. In addition, post-heading LTS has no effect on TGW and SNPP. However, LTS at the grain filling stage significantly prolonged the grain filling period but decreased grain filling rates. By incorporating these relationships, we developed a RSM with accumulated cold degree days based on canopy temperature. The model can effectively quantify the effect of post-heading LTS on rice yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters. By facilitating modeling of yields under LTS, our model can be used in evaluating the impact of future climate change on rice productivity.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants10071425/s1, Figure S1: Contour plots for relative change in spikelet weight at maturity (SWm), days from flowering to 50% grain filling (t50) and shape or steepness of sigmoid curve (b) under varied low-temperature stresses at flowering (A/a) and grain filling (B/b) stages in Huaidao 5 (A/B) and Nanjing 46 (a/b), Figure S2: Contour plots for relative changes in maximum grain filling rate (Rmax), mean grain filling rate (Rmean) and the total days from flowering to 95% SWm (D) under varied low-temperature stresses at flowering (A/a) and grain filling (B/b) stages in Huaidao 5 (A/B) and Nanjing 46 (a/b), Figure S3: Contour plots for relative changes in yield per plant (YPP), spikelet fertility (SF) and thousand grain weight (TGW) under varied low-temperature stresses at flowering (A/a) and grain filling (B/b) stages in Huaidao 5 (A/B) and Nanjing 46 (a/b), Table S1: Variance analysis of grain yield and related parameters under post-heading low-temperature stress during two-year experiments in 2018-2019, Table S2: Parameters of the RSM fitted on yield as well as yield and grain filling related parameters under varied low-temperature stresses

Author Contributions

Y.Z. and L.T. designed and supervised the project; I.A., J.D., M.K. and W.W. performed the greenhouse experiment; B.L., L.L. and W.C. provided critical feedback and helped to shape the research; I.A. wrote the manuscript with help from L.T., A.M. and Y.Z. for critical revisions and drafting. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31571566, 32021004), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (31725020), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shelton A.M., Zhao J.-Z., Roush R.T. Economic, Ecological, Food Safety, and Social Consequences of the Deployment of Bt. Transgenic Plants. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 2002;47:845–881. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida S. Fundamentals of Rice Crop Science. International Rice Research Institute; Los Baños, Philippines: 1981. pp. 65–109. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimono H., Hasegawa T., Iwama K. Response of Growth and Grain Yield in Paddy Rice to Cool Water at Different Growth Stages. Field Crop. Res. 2002;73:67–79. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4290(01)00184-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galiba G., Tóth B. Cold Stress. In: Brian T., Brian G.M., Denis J.M., editors. Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences. 2nd ed. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: London, UK: 2016. pp. 1–7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang X., Kurata N., Wei X., Wang Z.X., Wang A., Zhao Q., Zhao Y., Liu K., Lu H., Li W., et al. A Map of Rice Genome Variation Reveals the Origin of Cultivated Rice. Nature. 2012;490:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature11532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimono H., Hasegawa T., Iwama K. Modeling the Effects of Water Temperature on Rice Growth and Yield under a Cool Climate: I. Model Development. Agron. J. 2007;99:1327–1337. doi: 10.2134/agronj2006.0337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee M.H. Low Temperature Tolerance in Rice: The Korean Experience In Increased Lowland Rice Production in the Mekong Region, Proceedings of the International Workshop, Vientiane, Laos, 30 October–2 November 2000. Australian Centre for International Ag-ricultural Research; Canberra, Australia: 2001. pp. 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai L., Lin X., Ye C., Ise K., Saito K., Kato A., Xu F., Yu T., Zhang D. Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci Controlling Cold Tolerance at the Reproductive Stage in Yunnan Landrace of Rice, Kunmingxiaobaigu. Breed. Sci. 2004;54:253–258. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.54.253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu L.M., Zhou L., Zeng Y.W., Wang F.M., Zhang H.L., Shen S.Q., Li Z.C. Identification and Mapping of Quantitative Trait Loci for Cold Tolerance at the Booting Stage in a Japonica Rice Near-Isogenic Line. Plant Sci. 2008;174:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang W., Lee J., Chu S.H., Ham T.H., Woo M.O., Cho Y., II, Chin J.H., Han L., Xuan Y., Yuan D., et al. Genotype×environment Interactions for Chilling Tolerance of Rice Recombinant Inbred Lines under Different Low Temperature Environments. Field Crop. Res. 2010;117:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2010.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang P., Hu T., Kong F., Xu J., Zhang D. Rice Exposure to Cold Stress in China: How Has Its Spatial Pattern Changed under Climate Change? Eur. J. Agron. 2019;103:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2018.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farell T.C., Fox K.M., Williams R.L., Fukai S., Reinke R.F., Lewin L.G. Increased lowland rice production in the Mekong Region, Proceedings of the International Workshop, Vientiane, Laos, 30 October–2 November 2000. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research; Canberra, Australia: 2001. Temperature constraints to rice production in Australia and Laos: A shared problem; pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J., Lin X., Sun Q., Jena K.K. Evaluation of Cold Tolerance for Japonica Rice Varieties from Different Country. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013;5:54–56. doi: 10.19026/ajfst.5.3311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li T.G., Visperas R.M., Vergara B.S. Correlation of Cold Tolerance at Different Growth Stages in Rice. J. Integ. Plant Biol. 1981;23:203–207. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimono H., Hasegawa T., Moriyama M., Fujimura S., Nagata T. Modeling Spikelet Sterility Induced by Low Temperature in Rice. Agron. J. 2005;97:1524–1536. doi: 10.2134/agronj2005.0043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao L., Liu L., Asseng S., Xia Y., Tang L., Liu B., Cao W., Zhu Y. Estimating Spring Frost and Its Impact on Yield across Winter Wheat in China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018;260–261:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neelima P., Rani K.J., Raju C.D., Keshavulu K. Evaluation of Rice Genotypes for Cold Tolerance. Agric. Sci. Res. J. 2015;5:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khatun H., Biswas P.S., Hwang H.G., Kim K.-M. A Quick and Simple In-House Screening Protocol for Cold-Tolerance at Seedling Stage in Rice. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2016;4:373–378. doi: 10.9787/PBB.2016.4.3.373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs B.C., Pearson C.J. Growth, Development and Yield of Rice in Response to Cold Temperature. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 1999;182:79–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-037x.1999.00259.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunawardena T.A., Fukai S., Blamey F.P.C. Low Temperature Induced Spikelet Sterility in Rice. II. Effects of Panicle and Root Temperatures. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2003;54:947–956. doi: 10.1071/AR03076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satake T., Koike S. Sterility Caused by Cooling Treatment at the Flowering Stage in Rice Plants I. The Stage and Organ Susceptible to Cool Temperature. Jap. J. Crop Sci. 1983;52:207–214. doi: 10.1626/jcs.52.207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida S., Hara T., Hara T. Effects of Air Temperature and Light on Grain Filling of an Indica and a Japonica Rice (Oryza sativa L.) under Controlled Environmental Conditions. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1977;23:93–107. doi: 10.1080/00380768.1977.10433026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arshad M.S., Farooq M., Asch F., Krishna J.S.V., Prasad P.V.V., Siddique K.H.M. Thermal Stress Impacts Reproductive Development and Grain Yield in Rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017;115:57–72. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siddik M.A., Zhang J., Chen J., Qian H., Jiang Y., Raheem A.k., Deng A., Song Z., Zheng C., Zhang W. Responses of Indica Rice Yield and Quality to Extreme High and Low Temperatures during the Reproductive Period. Eur. J. Agron. 2019;106:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2019.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martínez-Eixarch M., Ellis R.H. Temporal Sensitivities of Rice Seed Development from Spikelet Fertility to Viable Mature Seed to Extreme-Temperature. Crop Sci. 2015;55:354. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2014.01.0042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L., Xia Y., Liu B., Chang C., Xiao L., Shen J., Tang L., Cao W., Zhu Y. Individual and Combined Effects of Jointing and Booting Low-Temperature Stress on Wheat Yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2020;113 doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2019.125989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi P., Tang L., Lin C., Liu L., Wang H., Cao W., Zhu Y. Modeling the Effects of Post-Anthesis Heat Stress on Rice Phenology. Field Crop. Res. 2015;177:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2015.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L., Song H., Shi K., Liu B., Zhang Y., Tang L., Cao W., Zhu Y. Response of Wheat Grain Quality to Low Temperature during Jointing and Booting Stages—On the Importance of Considering Canopy Temperature. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019;278:107658. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2019.107658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji H., Xiao L., Xia Y., Song H., Liu B., Tang L., Cao W., Zhu Y., Liu L. Effects of Jointing and Booting Low Temperature Stresses on Grain Yield and Yield Components in Wheat. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017;243:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi P., Zhu Y., Tang L., Chen J., Sun T., Cao W., Tian Y. Differential Effects of Temperature and Duration of Heat Stress during Anthesis and Grain Filling Stages in Rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016;132:28–41. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2016.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espe M.B., Hill J.E., Hijmans R.J., McKenzie K., Mutters R., Espino L.A., Leinfelder-Miles M., van Kessel C., Linquist B.A. Point Stresses during Reproductive Stage Rather than Warming Seasonal Temperature Determine Yield in Temperate Rice. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017;23:4386–4395. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimono H. Earlier Rice Phenology as a Result of Climate Change Can Increase the Risk of Cold Damage during Reproductive Growth in Northern Japan. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011;144:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2011.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Espe M.B., Yang H., Cassman K.G., Guilpart N., Sharifi H., Linquist B.A. Estimating Yield Potential in Temperate High-Yielding, Direct-Seeded US Rice Production Systems. Field Crop. Res. 2016;193:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2016.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang P., Zhang Z., Chen Y., Wei X., Feng B., Tao F. How Much Yield Loss Has Been Caused by Extreme Temperature Stress to the Irrigated Rice Production in China? Clim. Chang. 2016;134:635–650. doi: 10.1007/s10584-015-1545-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Da Cruz R.P., Kothe Milach S.C., Federizzi L.C. Rice Cold Tolerance at the Reproductive Stage in a Controlled Environment. Sci. Agric. 2006;63:255–261. doi: 10.1590/S0103-90162006000300007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun T., Hasegawa T., Tang L., Wang W., Zhou J., Liu L., Liu B., Cao W., Zhu Y. Stage-Dependent Temperature Sensitivity Function Predicts Seed-Setting Rates under Short-Term Extreme Heat Stress in Rice. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018;256–257:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sánchez B., Rasmussen A., Porter J.R. Temperatures and the Growth and Development of Maize and Rice: A Review. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014;20:408–417. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell J.H., Zulkafli S.L., Bosse J., Campbell B., Snell P., Mace E.S., Godwin I.D., Fukai S. Rice-Cold Tolerance across Reproductive Stages. Crop Past. Sci. 2016;67:823–833. doi: 10.1071/CP15331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed N., Maekawa M., Tetlow I.J. Effects of Low Temperature on Grain Filling, Amylose Content, and Activity of Starch Biosynthesis Enzymes in Endosperm of Basmati Rice. Aus. J. Agric. Res. 2008;59:599. doi: 10.1071/AR07340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng F., Zhou Y., Wang S., Duan J., Zhang Z., Niu H., Jiang L., Cui S., Li X., Luo C., et al. Temperature Sensitivity Thresholds to Warming and Cooling in Phenophases of Alpine Plants. Clim. Chang. 2016;139:579–590. doi: 10.1007/s10584-016-1802-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barlow K.M., Christy B.P., O’Leary G.J., Riffkin P.A., Nuttall J.G. Simulating the Impact of Extreme Heat and Frost Events on Wheat Crop Production: A Review. Field Crop. Res. 2015;171:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2014.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Julia C., Dingkuhn M. Predicting Temperature Induced Sterility of Rice Spikelets Requires Simulation of Crop-Generated Microclimate. Eur. J. Agron. 2013;49:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2013.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang W., Han Y., Du H. Relationship between Canopy Temperature at Flowering Stage and Soil Water Content, Yield Components in Rice. Rice Sci. 2007;14:67–70. doi: 10.1016/S1672-6308(07)60010-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu W., Yu K., He T., Li F., Zhang D., Liu J. The Low Temperature Induced Physiological Responses of Avena nuda L., a Cold-Tolerant Plant Species. Sci. World J. 2013:658793. doi: 10.1155/2013/658793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai C., Yin X., He S., Jiang W., Si C., Struik P.C., Luo W., Li G., Xie Y., Xiong Y., et al. Responses of Wheat and Rice to Factorial Combinations of Ambient and Elevated CO 2 and Temperature in FACE Experiments. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016;22:856–874. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim J., Shon J., Lee C.K., Yang W., Yoon Y., Yang W.H., Kim Y.G., Lee B.W. Relationship between Grain Filling Duration and Leaf Senescence of Temperate Rice under High Temperature. Field Crop. Res. 2011;122:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2011.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tavares O.C.H., Santos L.A., Filho D.F., Ferreira L.M., García A.C., Castro T.A.V.T., Zonta E., Pereira M.G., Fernandes M.S. Response Surface Modeling of Humic Acid Stimulation of the Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Root System. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2020;67:1046–1059. doi: 10.1080/03650340.2020.1775199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu L., Ji H., An J., Shi K., Ma J., Liu B., Tang L., Cao W., Zhu Y. Response of Biomass Accumulation in Wheat to Low-Temperature Stress at Jointing and Booting Stages. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019;157:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.09.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.