Abstract

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection is a significant risk factor for developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). As HCC is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, screening patients with CHB at a high risk for HCC is recommended in an attempt to improve these outcomes. However, the screening recommendations on who to screen and how often are not uniform. Identifying patients at the highest risk of HCC would allow for the best use of health resources. In this review, we evaluate the literature on screening patients with CHB for HCC, strategies for optimizing adherence to screening, and potential risk stratification tools to identify patients with CHB at a high risk of developing HCC.

Keywords: hepatitis B, hepatocellular carcinoma, cost-effectiveness, screening, risk stratification, alpha-fetoprotein, adherence, ultrasound

1. Introduction

Liver cancer is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality on a global scale, with approximately 30,000 deaths expected annually in the United States in 2020 [1], and significantly increased incidence rates modelled by 2030 world-wide [2]. The most common form of liver cancer is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which accounts for approximately 75–85% of liver cancer cases [3]. HCC is within the seven most common cancers worldwide, and the third largest cause of cancer-induced mortality [4]. The leading cause of HCC worldwide is chronic hepatitis B virus (CHB) infection, which affects more than 250 million people world-wide [5]. Although every patient with CHB is at an elevated risk of developing HCC, this does not mean that each patient is at an equivalent risk. As demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, surveillance programs can be easily disrupted. However, effective models of risk stratification can ensure that remaining resources are optimally allocated to the prioritization and prevention for those at the highest risk until the system returns to full capacity [6]. Several scoring systems have been created in an attempt to optimize the distribution of patients into different risk profiles, based on patient characteristics, along with viral characteristics [7]. The heterogeneity of the global CHB induced HCC population has made it difficult to develop a unified risk-scoring system, with differences among methodologies in terms of how these scoring systems identify, score, and evaluate relevant variables. This review aims to provide a comprehensive summary for the clinician, regarding screening for HCC in patients with CHB. Topics covered include reviewing the epidemiology of HCC in CHB, the state of research regarding screening patients with CHB for HCC, a summary of current guidelines for screening, highlighting the key literature regarding cost-effectiveness of screening, identifying barriers to adherence, discussing strategies to improve screening, and providing a complete and comprehensive analysis of existing HCC risk stratification models in patients with HBV.

2. Epidemiology of Liver Cancer and HBV

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection accounts for 44–55% of HCC diagnoses world-wide, and those infected are at a 20-fold increased risk when compared to a non-infected population [8]. Although the prevalence of HCC in patients with CHB varies between populations, rates as high as 23.2% have been previously reported in Asia-specific studies [9]. High prevalence CHB regions are often resource limited and have a low human development index [10]; some of the most endemic regions include the Amazon Basin, Africa, Central, and Southeast Asia [11]. The relationship between CHB and HCC is further exemplified by the elevated risk of developing HCC in endemic regions, with sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern Asia being responsible for >80% of HCC cases [11]. This may change as HBV immunization programs gain stability in these regions [12]; however, there are limitations to its use as a prophylactic strategy against vertical transmission [13]. Although it is not a traditionally endemic region, the CHB population has been increasing in recent years in North America [14], with a 2020 study estimating approximately 1.59 million people having CHB in the United States of America [15]. This increase is mainly driven by external factors, such as an influx of immigration from countries with a high CHB prevalence. The increase in CHB has been paralleled by an increase in HCC, which is now the fastest growing cancer in the United States in terms of incidence [1]. Furthermore, the proportion of HCC cases resulting from CHB has also increased, with one American study demonstrating that the proportion of CHB-induced HCC cases grew from 4% to 21% [16]. Therefore, as CHB and HCC become more common in western populations, the burden of disease has shifted from its traditional localized distribution to a global impact.

3. Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

3.1. Rationale for Screening

The rationale for any screening strategy is to identify patients at earlier stages of disease where treatment has a higher likelihood of success, as well as to identify risk factors that increase the risk of developing the disease, as to allow for interventions [17]. Factors to consider in the evaluation of any screening strategy are whether it is a disease of concern, and whether the screening test is effective, reasonable in cost, and improves outcomes [17,18]. Screening for HCC clearly meets these criteria, given that HCC is a public health concern, leading to a significant loss of life years and quality of life [19].

Currently, an ultrasound with the possibility of adding alpha-fetoprotein are recommended as the screening strategies for HCC [20,21,22,23,24]. At this time, there are only three randomized clinical trials comparing HCC surveillance versus no surveillance, with conflicting results related to methodological challenges. The first trial studied patients from Shanghai that were employed in factories, schools or private enterprises, with CHB or chronic liver disease; they were allocated by cluster sampling into those who received AFP and an ultrasound every 6 months (n = 8109) and a control group (n = 9711) enrolled between 1992–1994 [25]. In screened patients, 38 patients with liver cancer were identified after 12,038 person-years, and in the control group 18 patients were diagnosed after 9573 person-years. Patients identified in the screening group had a 1-year survival of 88.1% and two-year survival of 77.5%, and HCC were found at an earlier stage than the control group; the control group had a 0% 1-year survival. Although this study estimated an average cost of $1500 USD per early-stage HCC diagnosis, the number of false positive screening results was not reported, and would likely have increased the procedural and administrative cost of executing this program.

A similar study was conducted through 1993–1995 in Shanghai, consisting of 18,816 patients aged 35–59 with chronic hepatitis B. Participants were randomly allocated to screening (9373) with alpha-fetoprotein and ultrasounds every 6 months, versus a control group (9443) [26]. The surveillance arm identified 86 cases with 32 deaths from HCC, and the control arm had 67 cases with 54 deaths, leading to a risk ratio of 0.63 (95% CI 0.41–0.98) for the screening arm. Notably, this trial has been criticized for a lack of information about each group’s baseline characteristics, and how the outcome of death from liver cancer was defined [27]. Furthermore, the cohort likely has significant overlap with the last study by Yang et al. [25], given the population characteristics and time frame of recruitment.

The third randomized trial focused on men aged 30–69 between 1989–1995 in Jiangsu Province, China, using alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels every 6 months (n = 3712, mean follow-up 61.9 months) with a threshold of 20 μg/L, versus a control group (n = 1869, mean follow-up 62.8 months) [28]. Adherence rates for obtaining AFP were low at about 30%. A significantly larger number of cases were identified in the screening arm vs. the control arm at early stages (BCLC Stage 0-A [29]), with early detection rates of 29.6% and 6.0%, respectively. The 5-year survival between the groups did not differ at 4%, and the risk ratio in the screening arm was not statistically significant (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.68–1.03), which may be related to the limited antiviral therapy available at the time of the study. The study has been criticized for the unclear randomization and allocation concealment techniques that were used [27].

A meta-analysis from 2014 which included the second and third trial, as well as 18 observational studies examining the role of screening in patients with chronic liver disease, concluded that it was uncertain whether systematic surveillance improved patient survival, and highlighted that more data were required given the relatively few studies on the CHB population [27]. A second meta-analysis published by Singal et al. [30] looking at patients with cirrhosis, suggested that the use of ultrasound was associated with a higher probability of diagnosing cancers at an earlier stage (OR 2.08, 95% CI 1.80–2.37) and improved survival (OR 1.90; 95% CI 1.67–2.17). These differences remained significant when accounting for lead time bias; however, only three publications looked at HBV patients in particular, with no subgroup analysis performed.

More recent epidemiological studies have shown potential survival benefits of HCC surveillance. One Canadian trial examined outcomes in patients with viral hepatitis diagnosed with liver cancer, and the impact of ultrasound screening prior to their diagnosis [31]. The 5-year survival in patients receiving routine surveillance (at least an ultrasound annually) was 31.93% (95% CI 25.77–38.24%) versus 20.67% (95% CI 16.86–24.74%) in patients who were not screened. Moreover, surveillance was associated with a mortality risk of 0.76 (95% CI 0.64–0.91), which indirectly supports the role of screening. Similarly, in patients with all-cause cirrhosis, screening for HCC has been suggested to have potential survival benefits [32,33,34]; although, a case-control study of the US Veterans Affairs cohort did not show a survival difference between those screened with ultrasounds and those who were not [35]. Current recommendations from the US National Cancer Institute suggest that screening patients at an increased risk does not lead to a decrease in mortality from HCC, as shown by fair quality evidence that is based on lead and length time bias [36].

Ideally, a randomized clinical trial in an attempt to best answer this question would be useful; however, this is unlikely to happen, given ethical concerns about the harm associated with no surveillance, as patients and practitioners prefer surveillance [37]. Further, answers to the true benefit of screening through cohort/case-control trials focusing on the role of screening patients with CHB will be important, given the limited high-quality literature to date. One potential barrier to a universal consensus regarding screening is the variation in efficacy of screening between regions. This is due to internal population factors, such as the prevalence of CHB and risk of tumor development based on prognostic factors of disease severity, in addition to health care resources available in the region. For example, although a male cohort between the ages of 70–79 may be at the highest risk of developing HCC, Japanese, African, and Chinese populations are skewed as significantly younger [21]. These differences in epidemiology are mirrored by regional differences in post-diagnosis outcomes [38], dependent on factors, such as availability of therapeutics and patient health status. Consequently, any analysis regarding the impact of surveillance may be limited to regional applicability, and if an RCT is conducted in the future it would be best to involve multiple regions, in an effort to create a generalizable scope of study.

3.2. Current Society Guidelines for HCC Screening

Currently, it is recommended by all major hepatology international societies to screen for liver cancer in patients with CHB deemed to be high risk with the use of abdominal ultrasound every 6 months, with variable recommendations regarding the inclusion of AFP. Although these guidelines are largely similar, there are some minor differences, i.e., the use of AFP and when to screen patients from an African background. We summarize the current society guidelines in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of International HCC Screening Recommendations.

| 1 | APASL 2017 | AASLD 2018 | CASL 2019 | EASL 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Strategy | ||||

| Abdominal ultrasound (US) | Recommended every 6 months | |||

| Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) | Recommend AFP every 6 months with US | Can consider AFP every 6 months with US | AFP use not recommended | |

| Patients for Which Screening is Recommended | ||||

| Patients with cirrhosis | Yes | Child Pugh A/B | Yes | Child Pugh A/B |

| Asian men with chronic hepatitis B | >40 years old | PAGE-B ≥ 10 | ||

| Asian women with chronic hepatitis B | >50 years old | |||

| African men/women with chronic hepatitis B | >20 | >40 | >20 | |

| Family history of hepatocellular carcinoma | Yes | Yes | Yes, >40 years old | No |

| Co-infected with hepatitis delta virus (HDV) | No | Yes | No | No |

| Co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | No | No | >40 years old | No |

1 APASL: Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; AASLD: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; EASL: European Association for the Study of the Liver; CASL: Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver; PAGE-B: platelets, age, gender-HBV score.

AFP is a glycoprotein produced primarily during the ontogenesis of the yolk sack and fetal liver, with a suppressed expression following birth. However, increased AFP production has been associated with reparative growth following liver damage [39], as well as oncogenesis, acting as a pro-proliferative protein involved in regulating apoptosis, growth, and angiogenesis [40]. Due to its association with abnormal hepatocyte proliferation, AFP elevations are well documented in both malignant liver disease [40] and nonmalignant liver diseases, such as acute hepatic failure [41] and CHB [42]. Unfortunately, the use of AFP as a screening tool remains unclear. A recent meta-analysis evaluated the effectiveness of screening with ultrasound versus using ultrasound and AFP in detecting early cancer [43]. Thirty-two studies were identified in this study (consisting of 13,367 patients). Ultrasound identified any stage of HCC with 84% sensitivity (95% CI 76–92%), while identifying early-stage HCC with 47% sensitivity (95% CI 33–61%). The addition of AFP to ultrasound increased the sensitivity to 63% (95% CI 48–75%) for early-stage HCC, and to 97% (95% CI 91–99%) for all stages of cancer. Subsequently, the addition of AFP reduced the specificity to 84% (95% CI 77–89%) from 92% (95% CI 85–96%). There were some limitations to this meta-analysis, as it had no studies that were looking at survival. Moreover, most studies only looked at HCC at any stage vs. early HCC, which may overestimate surveillance test performance. Furthermore, negative screening tests were not confirmed by another modality, which may lead to verification bias. Overall, it is critical to note that using AFP by itself is not recommended, as it has poor sensitivity and specificity [44].

3.2.1. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL)

The 2017 APASL guidelines [24] recommend abdominal ultrasounds with AFP every 6 months for HCC screening in patients with CHB cirrhosis in Asian females > 50 years, Asian males > 40 years, patients of African background > 20 years, and in patients with a family history of HCC (no specific starting age recommended) (Table 1). The AFP threshold recommended is 200 ng/mL to obtain the optimal positive likelihood ratio.

3.2.2. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)

The 2018 AASLD guidelines [22,23] recommend abdominal ultrasounds every 6 months with or without AFP. The latter is a significant change from the 2010 guidelines [45], which explicitly recommended against AFP, due to concerns with false positives and subsequent testing. The AFP threshold recommended by the AASLD is 20 ng/mL. High risk groups that are recommended for HCC screening include patients with cirrhosis secondary to CHB with either Child–Pugh A or B; Child–Pugh C patients who are non-transplant candidates are excluded, as treatment would likely not be feasible. Other patients recommended for screening include Asian females > 50 years, Asian males > 40 years, patients of African background > 40 years, patients with a first-degree relative with a history of HCC (no specific starting age recommended), and patients co-infected with hepatitis delta (HDV) (no specific starting age recommended) (Table 1).

3.2.3. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)

The 2018 EASL guidelines [21] advocate screening high risk patients with abdominal ultrasounds every 6 months, and do not recommend using AFP routinely, due to concerns regarding false-positive results in the context of active liver inflammation. Patients recommended for screening include those with Child–Pugh A or B cirrhosis; Child–Pugh C cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation; and patients with chronic hepatitis B determined to be at an intermediate or high risk of developing HCC, based on PAGE-B classes for those of Caucasian background (Table 1).

3.2.4. Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver (CASL)

The 2019 CASL guidelines [20] recommend performing abdominal ultrasounds every 6 months for patients deemed to be at a high risk for developing HCC. This includes patients with CHB cirrhosis, Asian females > 50 years, Asian males > 40 years, patients of African background > 20 years, and patients with a family history of hepatocellular carcinoma starting at age 40, as well as patients with HIV co-infection > 40 years (Table 1).

3.2.5. Guideline Based Approach to Co-Infection

All four guidelines discussed above highlight the potential impact of co-infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV), HDV or HIV as a risk factor for developing HCC, although each set of guidelines emphasizes a different viral co-infection. The data for the impact of co-infection on its development is strongest in HDV [46,47], with data for HCV [48] and HIV [49,50] being weaker. Although there may be an increased risk with co-infection, there is little evidence regarding how screening guidelines should be changed. This likely explains the lack of explicit comment throughout guidelines, regarding the impact of co-infection and HCC screening; this is an important area for further research. That being said, it is important to recognize that both patients with mono-infection and significant co-infection undergo the same HCC surveillance protocol under the previously mentioned guidelines, suggesting the primary driver for surveillance in this situation is the oncogenic potential of CHB.

3.3. Cost Effectiveness of Screening Strategies for HCC

A key component of any screening strategy is ensuring it offers good value for money; that is, the strategy is cost effective. The majority of studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of screening consider patients with cirrhosis, with a minority of studies looking at hepatitis B being mostly focused on Asian populations [51]. In studies comparing screening using abdominal ultrasound +/− AFP with no screening [52,53,54,55,56], screening programs were cost effective in all but one study [55].

There are two recent studies evaluating the cost effectiveness of imaging-based screening, as compared to no screening at all. A Taiwanese based study evaluated the cost effectiveness of screening patients with CHB with ultrasounds every 6 months versus no ultrasounds [56]. The base case was a 50-year-old individual who was followed over a 25-year time horizon. Screening had a cost of $5912.37 USD for 13.78 years of life, as compared to $557.10 for 13.53 years of life in the unscreened arm, working out to an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of $20,856.25/year of life gained. Sangmala and colleagues expanded this analysis, and evaluated multiple screening strategies in a Thailand population of patients with CHB between the ages of 40–60 with a lifetime time horizon [52]. The strategies evaluated in this model included abdominal ultrasound, AFP and US, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at either a 6-monthly or 12-monthly frequency. Without any form of screening, only 6.24 quality adjusted life years (QALY) were gained. The use of ultrasound or ultrasound and AFP for HCC screening were found to be the most cost effective strategies. Notably, CT and MRI based strategies were not cost effective.

A recent analysis evaluating the cost effectiveness of screening compares abdominal ultrasound with or without AFP for HCC screening. This analysis is novel in its consideration of the potential harm of unnecessary tests, due to false positives [57], which is not considered in previous studies. The cohort studied were patients with compensated cirrhosis over a lifetime horizon. The most cost effective strategy for the cohort was using US with AFP, with a cost of $1,254,173.20 USD for 6.02 QALY; both using US and no surveillance in this cohort was more expensive and less effective than US with AFP. Modelling the impact of false positive testing in the CHB population is an important area to evaluate, until then, extrapolation from the available evidence is required.

4. Challenges with Screening Adherence

Adherence by patients to screening programs is a key indicator of success. Unfortunately, a major challenge with HCC surveillance programs is that of poor adherence rates. A study from Washington State looking at 1137 patients with cirrhosis highlights this challenge. Over a 2-year period, 33% of this group had at least one ultrasound (intermittent surveillance), and those with CHB cirrhosis were found to be more likely to undergo surveillance. Notably, only 2% of patients in this study underwent consistent surveillance, defined as having an ultrasound every 6 months [32]. A recent meta-analysis looking at screening for patients at a high risk of developing HCC identified 22 studies involving 19,511 patients, showing an overall adherence rate of 52% (95% CI 38–66%). Looking at the subset of studies of patients with CHB (4 trials, 2651 patients), the adherence rate was significantly lower (32%, 95% CI 13–51%). A subsequent meta-analysis focusing on patients with cirrhosis identified 29 studies (n = 118,779 patients) with a surveillance rate of 24% (95% CI 18.4–30.1); however, higher surveillance rates were observed when patients were seen by gastroenterologists and/or hepatologists [58].

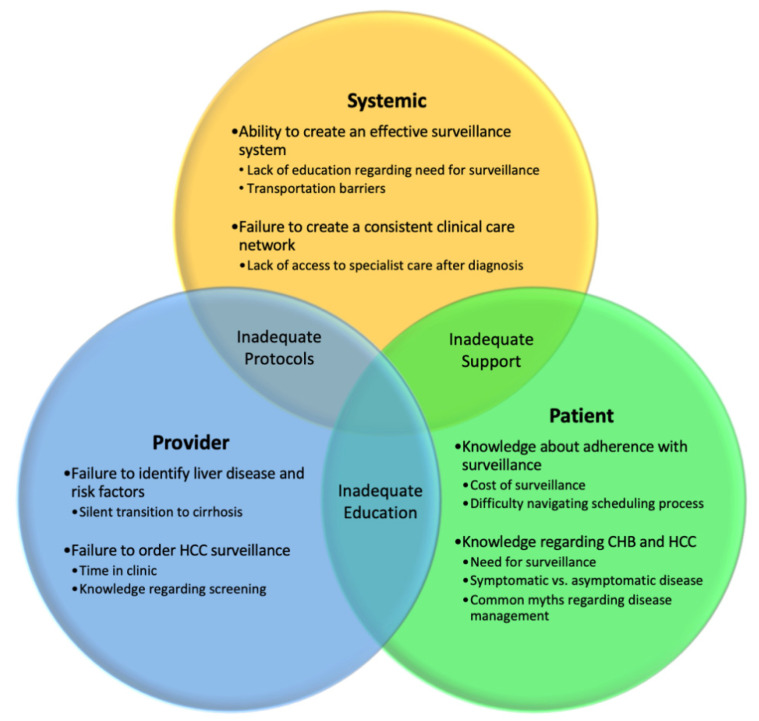

Screening programs are complex, and there are many reasons why lower adherence rates to screening are observed. Simply, there are system, provider, and patient-based factors, as outlined in Figure 1. Physician failure to order HCC surveillance was the most common reason for patients not receiving surveillance in two studies [59,60], with a separate investigation of physician surveillance practices finding only 22% relied on biannual imaging for HCC surveillance [61]. However, patient-driven non-adherence remains a significant determinant of surveillance inconsistency, with Singal et al. estimating patient non-adherence accounted for <10% of adherence failures [62] in their study. Patient factors can be further divided into those that are related to feasibility (i.e., cost, insurance coverage [62], difficulty navigating system, transportation [63]) and patient perceptions (i.e., knowledge regarding need for surveillance, HCC presentation, management [63]). Both patient and provider factors are further exacerbated by systemic flaws, with issues related to supporting surveillance infrastructure and clinical care network [64], identified by existing studies.

Figure 1.

Factors Associated with Decreased Adherence to HCC Screening [37,59,65,66].

Methods to Improve Adherence

A number of strategies have been studied in an attempt to improve adherence to HCC screening, including the education of primary care providers, nurse led clinics, mailed outreach, and radiology led programs [58]. Although all of these techniques have merit, the impact of these strategies are variable in efficacy. There have been four studies utilizing a post-intervention outcome of the proportion of patients meeting the gold-standard of having ultrasounds every 6 months. A randomized control trial evaluating outreach letters by mail showed that the rate increased from a baseline of 7% to 21% in the intervention arm [67]. Moreover, systematic changes may be associated with higher rates of surveillance, although likely coming at a higher cost. For example, in Australia, the introduction of a nurse-led clinic led to 53% of patients seen in the clinic having appropriate ultrasounds [68], while a more intense system redesign and patient education program led to 63% of patients being screened [69]. From the radiology provider side, a radiology recall program in the United Kingdom [70] led to 46% of patients achieving appropriate screening. There is no one-size solution, but likely a structured intervention whereby the payer, patient, provider, and system will be important to increase the adherence rate of screening.

5. Risk Stratification Systems for HCC Risk in Patients with HBV

When comparing the various models of risk assessment, there appears to be some common areas of contention, which are addressed differently by different models. Risk stratification scores for HCC risk in HBV have been previously reviewed [71]. Here, in Table 2 and Table 3, we present an updated critical summary of all published models of HCC risk assessment in patients with CHB. The majority of studies assessed in this review involve risk models, generated using homogenous populations. Although this is a result of the relatively homogenous populations in some of the countries in which these studies were generated (i.e., South Korea, Taiwan), this limits the utility of these models as international standards for HCC surveillance. In comparison, models generated in western countries, such as PAGE-B, have an advantage in terms of generalizability, as their study population for CHB often has a greater degree of ethnic diversity. However, as the number of models grows, newer studies such as the aMAP have been able to test their model in multiple populations of different ethnicities prior to publication, providing further support for the generalizability of their model. Although many studies report using gender as a risk factor, it is most likely that gender is incorrectly used, and this should be biological sex rather than the social concept of gender [72]; acknowledging this, we report the criteria as provided by the original publication. Ultimately, the majority of risk assessment models were reliant on follow-up studies, validating them in other population groups to strengthen their argument for generalizability.

Table 2.

Critical Analysis of Untreated Patient Risk Assessment Models.

| Name 1 | Components | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPM [73] | Cirrhosis Age Chronic HCV infection AFP CHB infection Chronic hepatitis Alcohol consumption Alcohol history Sex ALT |

|

|

| CU-HCC [74] | Age Albumin Bilirubin HBV DNA Cirrhosis |

|

|

| LSM-HCC [78] | Age Albumin HBV DNA LSM |

|

|

| GAG-HCC [81] | Version 1: Gender Age HBV DNA BCP mutations Cirrhosis Version 2: Gender Age HBV DNA Cirrhosis |

|

|

| REACH-B [82] | Gender Age ALT HBeAg HBV DNA |

|

|

| aMAP score [85] | Age Sex Albumin Bilirubin Platelet |

|

|

| RWS-HCC [88] | Sex Age Cirrhosis AFP |

|

|

| NGM1-HCC [89] | Gender Age Family history of HCC Alcohol consumption ALT HBeAg |

|

|

| NGM2-HCC [89] | Gender Age Family history of HCC Alcohol consumption ALT HBV DNA level |

|

|

| LSPS [90] |

|

|

|

| AGED [92] | Age Gender HBeAg HBV DNA |

|

|

| D2AS Risk score [93] | HBV DNA Sex Age |

|

|

1 IPM: individual prediction model; CU-HCC: Chinese University HCC score; LSM-HCC: liver stiffness measurement-HCC; GAG-HCC: guide with age, gender, HBV DNA, core promoter mutations and cirrhosis; REACH-B: risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B; aMAP score: age, male, albumin-bilirubin, platelets; RWS-HCC: real world risk score for hepatocellular carcinoma; NGM1-HCC: nomogram 1 for HCC risk; NGM2-HCC: nomogram 2 for HCC Risk; LSPS: LS value-spleen diameter to platelet ratio score; AGED: age, gender, HBeAg and HBV DNA levels; D2AS: DNA2, age, sex.

Table 3.

Critical Analysis of Treated Patient Risk Assessment Models.

| Name 1 | Components | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAGE-B [94] | Age Sex Platelets |

|

|

| mREACH-B [98] | Gender Age ALT HBeAg LSM |

|

|

| AASL-HCC [100] | Age Albumin Sex Cirrhosis |

|

|

| CAMD [101] | Cirrhosis Age Sex Diabetes |

|

|

| REAL-B [103] | Sex Age Alcohol Cirrhosis Diabetes Baseline Platelet Count Baseline AFP |

|

|

| HCC-RESCUE [104] | Age Gender Cirrhosis |

|

|

| APA-B [106] | Age Platelet Count Baseline AFP |

|

|

1 PAGE-B: platelets, age, gender-HBV score; mREACH-B: modified REACH-B; AASL-HCC: age, albumin, sex, liver cirrhosis)-HCC score; CAMD: cirrhosis, age, male sex, and diabetes mellitus score; REAL-B: real-world effectiveness from the Asia Pacific rim liver consortium for HBV; HCC-RESCUE: HCC-risk estimating score in CHB patients under entecavir; APA-B: age, platelet counts, and alpha-fetoprotein.

Another area of difference between risk assessment models is the use of a three-tier vs. two-tier stratification of patient risk of developing HCC. While three-tier models are more likely to be statistically accurate than two-tier models, given they allow for a greater degree of objectivity over the data being analyzed, they are limited in their potential utility. Protocols in practice for patients with CHB [107] essentially culminate in a binary decision, and it must be determined whether the patient would be included in a screening protocol or not. Ultimately, three-tier models may have limited clinical applicability, as many of the systems in place for screening patients are not designed to have separate protocols for patients who are “high risk” vs. those categorized as “medium risk”. Thus, having a paralleled stratification of outcome and model is beneficial for ease of use, and mitigates confusion on how patients should be stratified into surveillance vs. screening.

A limitation of most existing risk scores is a lack of discrimination between the stages of fibrosis beyond a diagnosis of overt cirrhosis. Studies have demonstrated a similar 5-year HCC probability for patients with a histopathological diagnosis of cirrhosis and those with a diagnosis of advanced fibrosis [108], elucidating the need for a more nuanced approach to fibrosis when developing a risk score. An improved assessment of the degree of fibrosis may help improve the cost effectiveness of screening strategies; there are a number of non-invasive techniques for fibrosis evaluation, which have been reviewed in recent guidelines [109]. Further, antiviral-treated patients require accurate staging of fibrosis for updating their risk of developing HCC, as patients with an appropriate treatment response may present with a regression of fibrosis, a positive prognostic indicator for HCC risk [110].

A recent study suggested the utility of a model combining AFP and the FIB-4 model, to predict HCC outcomes for patients with compensated cirrhosis, due to CHB being treated with antiviral therapy [111]. However, the novel approach was not compared to existing HCC-CHB risk stratification models, and the reliability of FIB-4 for non-Asian patients with CHB has also been called into question [112]. To appropriately utilize a FIB-4-like system for CHB, further adaptation may be necessary, with novel modifications being capable of identifying fibrosis, and stratifying HCC risk in the CHB population currently being investigated [112,113].

6. Conclusions

Although screening for HCC in high-risk patients with CHB is considered the standard of care and has proven benefits, there remains significant gaps in the knowledge base. Outstanding questions include whether alpha-fetoprotein should be a part of the screening program, as well as the risk stratification of patients with CHB in order to tailor screening programs to those with the highest risk of HCC. From a practical standpoint, investigations on how to develop structured interventions involving the payer, patient, and system to improve adherence to screening programs will be needed to maximize the effectiveness of any of these programs. Ultimately, surveillance programs are necessary for the effective identification of early-stage cancer in high-risk patients. This paper identifies potential areas of improvement to further improve their impact and accuracy in a clinical setting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E.C. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S. and S.E.C.; writing—review and editing, M.B. and R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rahib L., Wehner M.R., Matrisian L.M., Nead K.T. Estimated Projection of US Cancer Incidence and Death to 2040. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e214708. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valery P.C., Laversanne M., Clark P.J., Petrick J.L., McGlynn K.A., Bray F. Projections of Primary Liver Cancer to 2030 in 30 Countries Worldwide. Hepatology. 2018;67:600–611. doi: 10.1002/hep.29498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittal S., El-Serag H.B. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Consider the Population. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013;47:S2–S6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182872f29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulik L., El-Serag H.B. Epidemiology and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:477–491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng G., Gill U.S., Kennedy P.T.F. Prioritisation and the Initiation of HCC Surveillance in CHB Patients: Lessons to Learn from the COVID-19 Crisis. Gut. 2020;69:1907–1912. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomaa A.-I., Khan S.-A., Toledano M.-B., Waked I., Taylor-Robinson S.-D. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Pathogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4300–4308. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagnelli E., Macera M., Russo A., Coppola N., Sagnelli C. Epidemiological and Etiological Variations in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Infection. 2020;48:7–17. doi: 10.1007/s15010-019-01345-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wanich N., Vilaichone R.K., Chotivitayatarakorn P., Siramolpiwat S. High Prevalence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Infection in Thailand. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016;17:2857–2860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemoine M., Nayagam S., Thursz M. Viral Hepatitis in Resource-Limited Countries and Access to Antiviral Therapies: Current and Future Challenges. Future Virol. 2013;8:371–380. doi: 10.2217/fvl.13.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Serag H.B. Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–1273. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang M.-H., Chen C.-J., Lai M.-S., Hsu H.-M., Wu T.-C., Kong M.-S., Liang D.-C., Shau W.-Y., Chen D.-S. Universal Hepatitis B Vaccination in Taiwan and the Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:1855–1859. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A.E., Plitt S.S., Osiowy C., Surynicz K., Kouadjo E., Preiksaitis J., Lee B. Factors Associated with Vaccine Failure and Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis B among a Cohort of Canadian Mothers and Infants. J. Viral Hepat. 2011;18:468–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu M., Zhou Y., Holmberg S.D., Moorman A.C., Spradling P.R., Teshale E.H., Boscarino J.A., Daida Y.G., Schmidt M.A., Li J., et al. Trends in Diagnosed Chronic Hepatitis B in a US Health System Population, 2006–2015. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019;6:ofz286. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim J.K., Nguyen M.H., Kim W.R., Gish R., Perumalswami P., Jacobson I.M. Prevalence of Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1429–1438. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J.D., Mohammed H.A., Harmsen W.S., Enders F., Gores G.J., Roberts L.R. Recent Trends in the Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Olmsted County, Minnesota: A US Population-Based Study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017;51:742–748. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman C. What Makes a Screening Exam “Good”? Virtual Mentor VM. 2006;8:34–37. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.1.cprl1-0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson J.M.G., Jungner G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandhi S., Khubchandani S., Iyer R. Quality of Life and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2014;5:296–317. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coffin C.S., Fung S.K., Alvarez F., Cooper C.L., Doucette K.E., Fournier C., Kelly E., Ko H.H., Ma M.M., Martin S.R., et al. Management of Hepatitis B Virus Infection: 2018 Guidelines from the Canadian Association for the Study of Liver Disease and Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada. Can. Liver J. 2018;1:156–217. doi: 10.3138/canlivj.2018-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terrault N.A., Lok A.S.F., McMahon B.J., Chang K.-M., Hwang J.P., Jonas M.M., Brown R.S., Bzowej N.H., Wong J.B. Update on Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 Hepatitis B Guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560–1599. doi: 10.1002/hep.29800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marrero J.A., Kulik L.M., Sirlin C.B., Zhu A.X., Finn R.S., Abecassis M.M., Roberts L.R., Heimbach J.K. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723–750. doi: 10.1002/hep.29913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omata M., Cheng A.-L., Kokudo N., Kudo M., Lee J.M., Jia J., Tateishi R., Han K.-H., Chawla Y.K., Shiina S., et al. Asia-Pacific Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A 2017 Update. Hepatol. Int. 2017;11:317–370. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9799-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang B., Zhang B., Xu Y., Wang W., Shen Y., Zhang A., Xu Z. Prospective Study of Early Detection for Primary Liver Cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1997;123:357–360. doi: 10.1007/BF01438313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang B.-H., Yang B.-H., Tang Z.-Y. Randomized Controlled Trial of Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2004;130:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kansagara D., Papak J., Pasha A.S., O’Neil M., Freeman M., Relevo R., Quiñones A., Motu’apuaka M., Jou J.H. Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;161:261. doi: 10.7326/M14-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J.-G., Parkin D.M., Chen Q.-G., Lu J.-H., Shen Q.-J., Zhang B.-C., Zhu Y.-R. Screening for Liver Cancer: Results of a Randomised Controlled Trial in Qidong, China. J. Med. Screen. 2003;10:204–209. doi: 10.1258/096914103771773320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie D.-Y., Ren Z.-G., Zhou J., Fan J., Gao Q. 2019 Chinese Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Updates and Insights. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2020;9:452–463. doi: 10.21037/hbsn-20-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singal A.G., Pillai A., Tiro J. Early Detection, Curative Treatment, and Survival Rates for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thein H.-H., Yi Q., Dore G.J., Krahn M.D. Natural History of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in HIV-Infected Individuals and the Impact of HIV in the Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy: A Meta-Analysis. AIDS Lond. Engl. 2008;22:1979–1991. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e6d51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singal A.G., Tiro J., Li X., Adams-Huet B., Chubak J. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance Among Patients With Cirrhosis in a Population-Based Integrated Health Care Delivery System. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017;51:650–655. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi D.T., Kum H.-C., Park S., Ohsfeldt R.L., Shen Y., Parikh N.D., Singal A.G. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening Is Associated With Increased Survival of Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;17:976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong M.J., Rosinski A.A., Huynh C.T., Raman S.S., Lu D.S.K. Long-Term Survival after Surveillance and Treatment in Patients with Chronic Viral Hepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatol. Commun. 2017;1:595–608. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moon A.M., Weiss N.S., Beste L.A., Su F., Ho S.B., Jin G.-Y., Lowy E., Berry K., Ioannou G.N. No Association Between Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Reduced Cancer-Related Mortality in Patients With Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1128–1139. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.PDQ . PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. National Cancer Institute (US); Bethesda, MD, USA: 2002. Screening and Prevention Editorial Board Liver (Hepatocellular) Cancer Screening (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanwal F., Singal A.G. Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Best Practice and Future Direction. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:54–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goutté N., Sogni P., Bendersky N., Barbare J.C., Falissard B., Farges O. Geographical Variations in Incidence, Management and Survival of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in a Western Country. J. Hepatol. 2017;66:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taketa K. Alpha-Fetoprotein: Reevaluation in Hepatology. Hepatology. 1990;12:1420–1432. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galle P.R., Foerster F., Kudo M., Chan S.L., Llovet J.M., Qin S., Schelman W.R., Chintharlapalli S., Abada P.B., Sherman M., et al. Biology and Significance of Alpha-fetoprotein in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Int. 2019;39:2214–2229. doi: 10.1111/liv.14223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takikawa Y., Suzuki K. Is AFP a New Reliable Marker of Liver Regeneration in Acute Hepatic Failure? J. Gastroenterol. 2002;37:681–682. doi: 10.1007/s005350200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patil M., Sheth K.A., Adarsh C.K. Elevated Alpha Fetoprotein, No Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2013;3:162–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2013.02.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tzartzeva K., Obi J., Rich N.E., Parikh N.D., Marrero J.A., Yopp A., Waljee A.K., Singal A.G. Surveillance Imaging and Alpha Fetoprotein for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1706–1718. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frenette C.T., Isaacson A.J., Bargellini I., Saab S., Singal A.G. A Practical Guideline for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening in Patients at Risk. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes. 2019;3:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruix J., Sherman M. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alfaiate D., Clément S., Gomes D., Goossens N., Negro F. Chronic Hepatitis D and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J. Hepatol. 2020;73:533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farci P., Niro G.A., Zamboni F., Diaz G. Hepatitis D Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Viruses. 2021;13:830. doi: 10.3390/v13050830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho L.Y., Yang J.J., Ko K.-P., Park B., Shin A., Lim M.K., Oh J.-K., Park S., Kim Y.J., Shin H.-R., et al. Coinfection of Hepatitis B and C Viruses and Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Cancer. 2011;128:176–184. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim H.N. Chronic Hepatitis B and HIV Coinfection: A Continuing Challenge in the Era of Antiretroviral Therapy. Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 2020;19:345–353. doi: 10.1007/s11901-020-00541-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Merchante N., Rodríguez-Fernández M., Pineda J.A. Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in HIV-Infected Patients: Current Evidence and Controversies. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17:6–17. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen A.L.T., Nguyen H.T.T., Yee K.C., Palmer A.J., Blizzard C.L., de Graaff B. A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of Health Economic Evaluations of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening Strategies. Value Health. 2021;24:733–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sangmala P., Chaikledkaew U., Tanwandee T., Pongchareonsuk P. Economic Evaluation and Budget Impact Analysis of the Surveillance Program for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Thai Chronic Hepatitis B Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8993–9004. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.20.8993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kang J.Y., Lee T.P., Yap I., Lun K.C. Analysis of Cost-Effectiveness of Different Strategies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening in Hepatitis B Virus Carriers. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1992;7:463–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1992.tb01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lam C. Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): Is It Cost-Effective? Hong Kong Pract. 2000;22:546–551. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robotin M.C., Kansil M., Howard K., George J., Tipper S., Dore G.J., Levy M., Penman A.G. Antiviral Therapy for Hepatitis B-Related Liver Cancer Prevention Is More Cost-Effective than Cancer Screening. J. Hepatol. 2009;50:990–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang Y., Lairson D.R., Chan W., Lu S.-N., Aoki N. Cost-Effectiveness of Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma among Subjects at Different Levels of Risk. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2011;17:261–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parikh N.D., Singal A.G., Hutton D.W., Tapper E.B. Cost-Effectiveness of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance: An Assessment of Benefits and Harms. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1642–1649. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolf E., Rich N.E., Marrero J.A., Parikh N.D., Singal A.G. Use of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hepatology. 2021;73:713–725. doi: 10.1002/hep.31309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singal A.G., Yopp A.C., Gupta S., Skinner C.S., Halm E.A., Okolo E., Nehra M., Lee W.M., Marrero J.A., Tiro J.A. Failure Rates in the Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance Process. Cancer Prev. Res. Phila. Pa. 2012;5:1124–1130. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marquardt P., Liu P., Immergluck J., Olivares J., Arroyo A., Rich N.E., Parikh N.D., Yopp A.C., Singal A.G. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening Process Failures in Patients with Cirrhosis. Hepatol. Commun. 2021 doi: 10.1002/hep4.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bharadwaj S., Gohel T.D. Perspectives of Physicians Regarding Screening Patients at Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2016;4:237–240. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gou089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singal A.G., Li X., Tiro J., Kandunoori P., Adams-Huet B., Nehra M.S., Yopp A. Racial, Social, and Clinical Determinants of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance. Am. J. Med. 2015;128:90.e1–90.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farvardin S., Patel J., Khambaty M., Yerokun O.A., Mok H., Tiro J.A., Yopp A.C., Parikh N.D., Marrero J.A., Singal A.G. Patient-Reported Barriers Are Associated with Lower Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance Rates in Patients with Cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2017;65:875–884. doi: 10.1002/hep.28770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goldberg D.S., Taddei T.H., Serper M., Mehta R., Dieperink E., Aytaman A., Baytarian M., Fox R., Hunt K., Pedrosa M., et al. Identifying Barriers to Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in a National Sample of Patients with Cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2017;65:864–874. doi: 10.1002/hep.28765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simmons O.L., Feng Y., Parikh N.D., Singal A.G. Primary Care Provider Practice Patterns and Barriers to Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;17:766–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dalton-Fitzgerald E., Tiro J., Kandunoori P., Halm E.A., Yopp A., Singal A.G. Practice Patterns and Attitudes of Primary Care Providers and Barriers to Surveillance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2015;13:791–798. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Singal A.G., Tiro J.A., Murphy C.C., Marrero J.A., McCallister K., Fullington H., Mejias C., Waljee A.K., Pechero Bishop W., Santini N.O., et al. Mailed Outreach Invitations Significantly Improve HCC Surveillance Rates in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Hepatology. 2019;69:121–130. doi: 10.1002/hep.30129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nazareth S., Leembruggen N., Tuma R., Chen S.-L., Rao S., Kontorinis N., Cheng W. Nurse-Led Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance Clinic Provides an Effective Method of Monitoring Patients with Cirrhosis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2016;22(Suppl. 2):S3–S11. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kennedy N.A., Rodgers A., Altus R., McCormick R., Wundke R., Wigg A.J. Optimisation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Patients with Viral Hepatitis: A Quality Improvement Study. Intern. Med. J. 2013;43:772–777. doi: 10.1111/imj.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Farrell C., Halpen A., Cross T.J.S., Richardson P.D., Johnson P., Joekes E.C. Ultrasound Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Service Evaluation of a Radiology-Led Recall System in a Tertiary-Referral Centre for Liver Diseases in the UK. Clin. Radiol. 2017;72:338.e11–338.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu S., Zeng N., Sun F., Zhou J., Wu X., Sun Y., Wang B., Zhan S., Kong Y., Jia J., et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Prediction Models in Chronic Hepatitis B: A Systematic Review of 14 Models and External Validation. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Congly S.E., Brownfield K.A. Distinguishing between Sex and Gender Is Critical for Research in Transplantation. Transplantation. 2019;104:e57. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Han K.-H., Ahn S.H. How to Predict HCC Development in Patients with Chronic B Viral Liver Disease? Intervirology. 2005;48:23–28. doi: 10.1159/000082091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wong V.W.S., Chan S.L., Mo F., Chan T.C., Loong H.H.F., Wong G.L.H., Lui Y.Y.N., Chan A.T.C., Sung J.J.Y., Yeo W., et al. Clinical Scoring System to Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B Carriers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:1660–1665. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chan H.L.Y., Hui A.Y., Wong M.L., Tse A.M.L., Hung L.C.T., Wong V.W.S., Sung J.J.Y. Genotype C Hepatitis B Virus Infection Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut. 2004;53:1494–1498. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abu-Amara M., Cerocchi O., Malhi G., Sharma S., Yim C., Shah H., Wong D.K., Janssen H.L.A., Feld J.J. The Applicability of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk Prediction Scores in a North American Patient Population with Chronic Hepatitis B Infection. Gut. 2016;65:1347–1358. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-309099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yip T.C.-F., Hui V.W.-K., Tse Y.-K., Wong G.L.-H. Statistical Strategies for HCC Risk Prediction Models in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B. Hepatoma Res. 2021;2021:7. doi: 10.20517/2394-5079.2020.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wong G.L.-H., Chan H.L.-Y., Wong C.K.-Y., Leung C., Chan C.Y., Ho P.P.-L., Chung V.C.-Y., Chan Z.C.-Y., Tse Y.-K., Chim A.M.-L., et al. Liver Stiffness-Based Optimization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk Score in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B. J. Hepatol. 2014;60:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ganne-Carrié N., Ziol M., de Ledinghen V., Douvin C., Marcellin P., Castera L., Dhumeaux D., Trinchet J.-C., Beaugrand M. Accuracy of Liver Stiffness Measurement for the Diagnosis of Cirrhosis in Patients with Chronic Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2006;44:1511–1517. doi: 10.1002/hep.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wong V.W.-S., Janssen H.L.A. Can We Use HCC Risk Scores to Individualize Surveillance in Chronic Hepatitis B Infection? J. Hepatol. 2015;63:722–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yuen M.-F., Tanaka Y., Fong D.Y.-T., Fung J., Wong D.K.-H., Yuen J.C.-H., But D.Y.-K., Chan A.O.-O., Wong B.C.-Y., Mizokami M., et al. Independent Risk Factors and Predictive Score for the Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B. J. Hepatol. 2009;50:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang H.I., Yuen M.F., Chan H.L.Y., Han K.H., Chen P.J., Kim D.Y., Ahn S.H., Chen C.J., Wong V.W.S., Seto W.K. Risk Estimation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B (REACH-B): Development and Validation of a Predictive Score. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:568–574. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen T.M., Chang C.C., Huang P.T., Wen C.F., Lin C.C. Performance of Risk Estimation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B (REACH-B) Score in Classifying Treatment Eligibility under 2012 Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) Guideline for Chronic Hepatitis B Patients. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013;37:243–251. doi: 10.1111/apt.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Magalhães-Costa P., Lebre L., Peixe P., Santos S., Chagas C. Carcinoma Hepatocelular Em Doentes Com Infecção Crónica Pelo Vírus Da Hepatite B Sob Análogos Dos Nucleós(t)Idos de 3a Geração: Factores de Risco e o Desempenho de Um Score de Risco. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2016;23:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jpge.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fan R., Papatheodoridis G., Sun J., Innes H., Toyoda H., Xie Q., Mo S., Sypsa V., Guha I.N., Kumada T., et al. AMAP Risk Score Predicts Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2020;73:1368–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Alempijevic T.M., Stojkovic Lalosevic M., Dumic I., Jocic N., Markovic A.P., Dragasevic S., Jovicic I., Lukic S., Popovic D., Milosavljevic T. Diagnostic Accuracy of Platelet Count and Platelet Indices in Noninvasive Assessment of Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Patients. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/6070135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shiha G., Mikhail N., Soliman R. External Validation of AMAP Risk Score in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype 4 and Cirrhosis Who Achieved SVR Following DAAs. J. Hepatol. 2020;74:994–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Poh Z., Shen L., Yang H.-I., Seto W.-K., Wong V.W., Lin C.Y., Goh B.-B.G., Chang P.-E.J., Chan H.L.-Y., Yuen M.-F., et al. Real-World Risk Score for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (RWS-HCC): A Clinically Practical Risk Predictor for HCC in Chronic Hepatitis B. Gut. 2016;65:887–888. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang H.-I., Sherman M., Su J., Chen P.-J., Liaw Y.-F., Iloeje U.H., Chen C.-J. Nomograms for Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:2437–2444. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shin S.H., Kim S.U., Park J.Y., Kim D.Y., Ahn S.H., Han K.-H., Kim B.K. Liver Stiffness-Based Model for Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Comparison with Histological Fibrosis. Liver Int. 2015;35:1054–1062. doi: 10.1111/liv.12621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim B.K., Park Y.N., Kim D.Y., Park J.Y., Chon C.Y., Han K.-H., Ahn S.H. Risk Assessment of Development of Hepatic Decompensation in Histologically Proven Hepatitis B Viral Cirrhosis Using Liver Stiffness Measurement. Digestion. 2012;85:219–227. doi: 10.1159/000335430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fan C., Li M., Gan Y., Chen T., Sun Y., Lu J., Wang J., Jin Y., Lu J., Qian G., et al. A Simple AGED Score for Risk Classification of Primary Liver Cancer: Development and Validation with Long-Term Prospective HBsAg-Positive Cohorts in Qidong, China. Gut. 2019;68:948–949. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sinn D.H., Lee J.-H., Kim K., Ahn J.H., Lee J.H., Kim J.H., Lee D.H., Yoon J.-H., Kang W., Gwak G.-Y., et al. A Novel Model for Predicting Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B and Normal Alanine Aminotransferase Levels. Gut Liver. 2017;11:528–534. doi: 10.5009/gnl16403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Papatheodoridis G., Dalekos G., Sypsa V., Yurdaydin C., Buti M., Goulis J., Calleja J.L., Chi H., Manolakopoulos S., Mangia G., et al. PAGE-B Predicts the Risk of Developing Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Caucasians with Chronic Hepatitis B on 5-Year Antiviral Therapy. J. Hepatol. 2016;64:800–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kirino S., Tamaki N., Kaneko S., Kurosaki M., Inada K., Yamashita K., Osawa L., Hayakawa Y., Sekiguchi S., Watakabe K., et al. Validation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk Scores in Japanese Chronic Hepatitis B Cohort Receiving Nucleot(s)Ide Analog. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Aust. 2020;35:1595–1601. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yip T.C.F., Wong G.L.H., Wong V.W.S., Tse Y.K., Liang L.Y., Hui V.W.K., Lee H.W., Lui G.C.Y., Chan H.L.Y. Reassessing the Accuracy of PAGE-B-Related Scores to Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B. J. Hepatol. 2020;72:847–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim M.N., Hwang S.G., Rim K.S., Kim B.K., Park J.Y., Kim D.Y., Ahn S.H., Han K.H., Kim S.U. Validation of PAGE-B Model in Asian Chronic Hepatitis B Patients Receiving Entecavir or Tenofovir. Liver Int. 2017;37:1788–1795. doi: 10.1111/liv.13450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee H.W., Yoo E.J., Kim B.K., Kim S.U., Park J.Y., Kim D.Y., Ahn S.H., Han K.-H. Prediction of Development of Liver-Related Events by Transient Elastography in Hepatitis B Patients With Complete Virological Response on Antiviral Therapy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1241–1249. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Seo Y.S., Jang B.K., Um S.H., Hwang J.S., Han K.-H., Kim S.G., Lee K.S., Kim S.U., Kim Y.S., Lee J.I. Validation of Risk Prediction Models for the Development of HBV-Related HCC: A Retrospective Multi-Center 10-Year Follow-up Cohort Study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:113213–113224. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yu J.H., Suh Y.J., Jin Y.-J., Heo N.-Y., Jang J.W., You C.R., An H.Y., Lee J.-W. Prediction Model for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Treatment-Naive Chronic Hepatitis B Patients Receiving Entecavir/Tenofovir. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019;31:865–872. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hsu Y.-C., Yip T.C.-F., Ho H.J., Wong V.W.-S., Huang Y.-T., El-Serag H.B., Lee T.-Y., Wu M.-S., Lin J.-T., Wong G.L.-H., et al. Development of a Scoring System to Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Asians on Antivirals for Chronic Hepatitis B. J. Hepatol. 2018;69:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim S.U., Seo Y.S., Lee H.A., Kim M.N., Kim E.H., Kim H.Y., Lee Y.R., Lee H.W., Park J.Y., Kim D.Y., et al. Validation of the CAMD Score in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection Receiving Antiviral Therapy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;18:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yang H.-I., Yeh M.-L., Wong G.L., Peng C.-Y., Chen C.-H., Trinh H.N., Cheung K.-S., Xie Q., Su T.-H., Kozuka R., et al. Real-World Effectiveness From the Asia Pacific Rim Liver Consortium for HBV Risk Score for the Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients Treated With Oral Antiviral Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;221:389–399. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sohn W., Cho J.-Y., Kim J.H., Lee J.I., Kim H.J., Woo M.-A., Jung S.-H., Paik Y.-H. Risk Score Model for the Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Treatment-Naïve Patients Receiving Oral Antiviral Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis B. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2017;23:170–178. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2016.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Güzelbulut F., Gökçen P., Can G., Adalı G., Değirmenci Saltürk A.G., Bahadır Ö., Özdil K., Doğanay H.L. Validation of the HCC-RESCUE Score to Predict Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Caucasian Chronic Hepatitis B Patients under Entecavir or Tenofovir Therapy. J. Viral Hepat. 2021;28:826–836. doi: 10.1111/jvh.13485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen C.-H., Lee C.-M., Lai H.-C., Hu T.-H., Su W.-P., Lu S.-N., Lin C.-H., Hung C.-H., Wang J.-H., Lee M.-H., et al. Prediction Model of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Asian Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Treated with Entecavir. Oncotarget. 2017;8:92431–92441. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Heimbach J.K., Kulik L.M., Finn R.S., Sirlin C.B., Abecassis M.M., Roberts L.R., Zhu A.X., Murad M.H., Marrero J.A. AASLD Guidelines for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:358–380. doi: 10.1002/hep.29086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Axley P., Mudumbi S., Sarker S., Kuo Y.-F., Singal A. Patients with Stage 3 Compared to Stage 4 Liver Fibrosis Have Lower Frequency of and Longer Time to Liver Disease Complications. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0197117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Berzigotti A., Tsochatzis E., Boursier J., Castera L., Cazzagon N., Friedrich-Rust M., Petta S., Thiele M. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on Non-Invasive Tests for Evaluation of Liver Disease Severity and Prognosis–2021 Update. J. Hepatol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Udompap P., Kim W.R. Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Suppressed Viral Replication: Changes in Risk Over Time. Clin. Liver Dis. 2020;15:85–90. doi: 10.1002/cld.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chiang H.-H., Lee C.-M., Hu T.-H., Hung C.-H., Wang J.-H., Lu S.-N., Lai H.-C., Su W.-P., Lin C.-H., Peng C.-Y., et al. A Combination of the On-Treatment FIB-4 and Alpha-Foetoprotein Predicts Clinical Outcomes in Cirrhotic Patients Receiving Entecavir. Liver Int. 2018;38:1997–2005. doi: 10.1111/liv.13889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Demir M., Grünewald F., Lang S., Schramm C., Bowe A., Mück V., Kütting F., Goeser T., Steffen H.-M. Elevated Liver Fibrosis Index FIB-4 Is Not Reliable for HCC Risk Stratification in Predominantly Non-Asian CHB Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4602. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Metwally K., Elsabaawy M., Abdel-Samiee M., Morad W., Ehsan N., Abdelsameea E. FIB-5 versus FIB-4 Index for Assessment of Hepatic Fibrosis in Chronic Hepatitis B Affected Patients. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2020;6:335–338. doi: 10.5114/ceh.2020.102157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]