Abstract

Purpose

Lifelong multivitamin supplementation is recommended to prevent nutritional deficiencies. Despite this advice, deficiencies are common which may be due to poor adherence to MVS intake. The aim of this study was to identify which factors affect patient adherence to Multivitamin Supplement (MVS) intake after bariatric surgery.

Materials and Methods

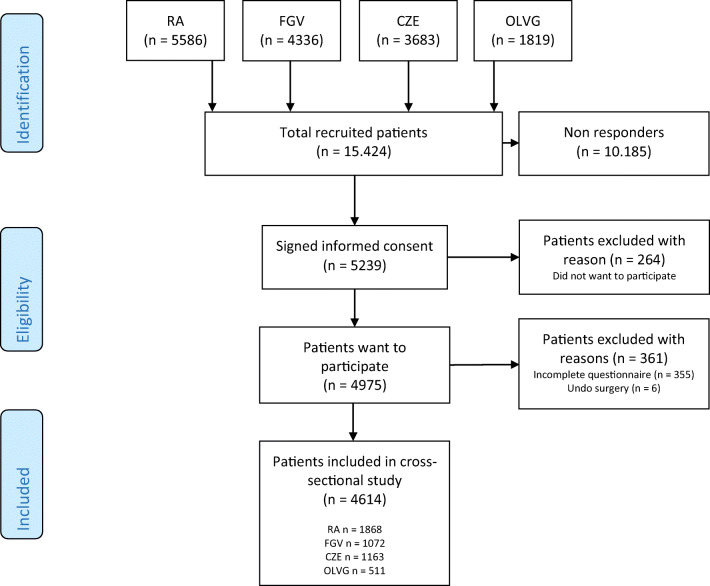

A 42-item questionnaire was sent to 15,424 patients from four Dutch bariatric center. In total, 4975 patients wanted to participate of which 361 patients were excluded. A total of 4614 patients were included, and MVS users (n=4274, 92.6%) were compared to non-users (n=340, 7.4%). Most patients underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (64.3%) or sleeve gastrectomy (32.3%).

Results

Seven hundred and ten patients (15.4%) reported inconsistent MVS use and 340 patients (7.4%) did not use any MVS at all. For inconsistent MVS users, most reported reasons included forgetting daily intake (68.3%), gastro-intestinal side effects (25.6%) and unpleasant taste or smell (22.7%), whereas for non-users gastro-intestinal side effects (58.5%), high costs (13.5%) and the absence of vitamin deficiencies (20.9%) were most frequently reported. Overall, 28.5% were dissatisfied about instructions on MVS use, attention paid to MVS use during medical consultation and the extent to which personal preferences were taken into account.

Conclusion

The attitude of bariatric patients towards MVS use is predominantly negative. It is important to provide accurate information on different options for MVS intake and collect information about patient’s personal preferences when prescribing supplements. Improving adherence to MVS intake is challenging and requires implementation of a shared decision-making process, further optimization of MVS formulas and exploring options for reimbursement.

Graphical abstract

Key words: Bariatric surgery, Metabolic surgery, Vitamin supplementation, Vitamin deficiencies, Patient compliance, Patient adherence, Questionnaire

Introduction

Worldwide, morbid obesity is a fast-growing problem for which bariatric surgery is an effective treatment to lose weight and improve obesity related comorbidities including hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus and obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome [1]. In spite of multiple clinical benefits, all bariatric procedures, to variable degrees, alter the anatomy and physiology of the gastro-intestinal tract. As a result, patients are more susceptible to developing nutritional deficiencies. Therefore, lifelong use of multivitamin supplementation (MVS) is recommended [2–4]. However, therapeutic non-adherence to MVS intake after bariatric surgery is frequently encountered in both clinical practice and research and is therefore a major topic of discussion [5, 6]. Despite proven safety and effectiveness, a large number of bariatric patients stop taking MVS or become less consistent with MVS intake over time. Potential barriers and facilitators of non-adherence have recently been described in a narrative review by our study group [7], but research in the population of bariatric patients is lacking. The aim of this study is to identify which factors affect patient adherence to MVS intake after bariatric surgery from a patient perspective.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional non-validated 42-question survey among bariatric patients from four Dutch high-volume bariatric centers: Catharina Hospital Eindhoven, Rijnstate Arnhem, Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland and Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis. All questions were multiple-choice and divided into four topics: patient-related factors, MVS-related factors, psychosocial and economic-related factors and healthcare-related factors. The format of these topics was established based on the study by Jin et al. [8]. A previous review by our research group on potential influencing factors that negatively influence the adherence to MVS intake was used as input for the questions [7].

We included patients who underwent bariatric surgery from 2010 to 2020, including sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), one-anastomosis gastric bypass, single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass and duodenal switch. Patients who underwent revisional and/or secondary surgery were also included. Exclusion criteria were incomplete questionnaires and reversal of the bariatric procedure (‘undo surgery’). In total, 15,424 patients were recruited between October and December 2020 (Figure 1). All data were collected anonymously in Data Management® (Cloud9, Research Manager, Deventer). Digital informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart patient inclusion. CZE, Catharina Hospital Eindhoven; FGV, Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland; OLVG, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis; RA, Rijnstate Arnhem

Statistical Analyses

Continuous data is presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed data and as median and interquartile range (Q1–Q3) for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentages. Differences in outcomes between MVS users and non-users are compared using independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables. Chi-square tests are used for categorical variables. p-values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA Version 25.0) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

In total, 5239 patients (34%) signed the informed consent of which 4614 patients were available for analysis (Figure 1). The study population was divided into two groups: MVS users (n = 4274, 92.6%) and non-users (n = 340, 7.4%) (Table 1). Both groups were similar with respect to gender, educational level, body weight and body mass index. In comparison to MVS users, non-users were younger (51.0 (43.0–57.0) vs 43.0 (33.0–53.0) years) and differed in marital status, type of surgery and time since surgery (p < 0.001 for all). The majority of MVS users underwent RYGB (66.0%) whereas the majority of the non-users underwent SG (54.4%).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population

| Total group (n = 4614) |

MVS users (n = 4274) |

Non-users (n = 340) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.0 (43.0 – 57.0) | 51.0 (43.0 – 57.0) | 43.0 (33.0 – 53.0) | < 0.0011 |

| Gender (male) | 930 (20.2) | 871 (20.4) | 59 (17.4) | 0.1812 |

| Marital status | ||||

| - Single | 772 (16.7) | 694 (16.2) | 78 (22.9) | 0.0012 |

| - Living with partner | 606 (13.1) | 547 (12.8) | 59 (17.4) | |

| - Married or registered partnership | 2900 (62.9) | 2721 (63.7) | 179 (52.6) | |

| - Divorced or separated | 251 (5.4) | 233 (5.5) | 18 (5.3) | |

| - Widowed | 85 (1.8) | 79 (1.8) | 6 (1.8) | |

| Education level | ||||

| - Low | 1165 (25.2) | 1085 (25.4) | 80 (23.5) | 0.6242 |

| - Middle | 2062 (44.7) | 1902 (44.5) | 160 (47.1) | |

| - High | 1387 (30.1) | 1287 (30.1) | 100 (29.4) | |

| Body weight (kg) | 84.0 (73.6 – 97.0) | 84.0 (73.5 – 97.0) | 85.0 (74.1 – 98.8) | 0.2571 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.7 (25.7 – 32.4) | 28.7 (25.7 – 32.4) | 28.7 (25.9 – 33.2) | 0.4721 |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| - Sleeve gastrectomy | 1490 (32.3) | 1305 (30.5) | 185 (54.4) | < 0.0012 |

| - Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | 2966 (64.3) | 2819 (66.0) | 147 (43.2) | |

| - One-anastomosis gastric bypass | 108 (2.3) | 105 (2.5) | 3 (0.9) | |

| - Other | 43 (0.9) | 39 (0.9) | 4 (1.2) | |

| - Unknown | 7 (0.2) | 6 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Time since surgery | ||||

| - 0–1 years | 680 (14.7) | 658 (15.4) | 22 (6.5) | <0.0012 |

| - 1–2 years | 1071 (23.2) | 1024 (24.0) | 47 (13.8) | |

| - 2–3 years | 1096 (23.8) | 1011 (23.7) | 85 (25.0) | |

| - 3–4 years | 866 (18.8) | 771 (18.0) | 95 (27.9) | |

| - 4–5 years | 570 (12.4) | 521 (12.2) | 49 (14.4) | |

| - > 5 years | 331 (7.2) | 289 (6.8) | 42 (12.4) | |

Data are presented as median (Q1 – Q3) and frequencies (percentages)

BMI, body mass index; MVS, multivitamin supplementation

1Mann-Whitney U Test

2Pearson Chi-square test

MVS-Related Factors

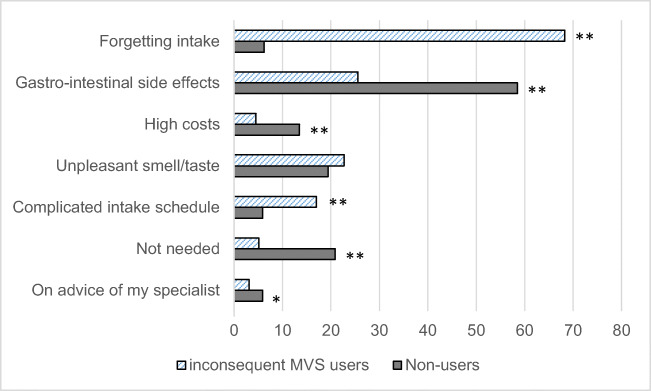

In total, 4274 patients (92.6%) used a MVS after bariatric surgery. A majority of the MVS users (85.2%) use specifically designed WLS (weight loss surgery) MVS, of which the majority used the formulations of FitForMe® (69.5%). Other reported WLS formulations were “Vitamine op recept” (8.5%), Flindall (3.9%) and Elan (3.0%). A small part of the MVS users (12.7%) used regular (‘over the counter’) MVS. Of all MVS users, 16.6% did not take their MVS consistently, for which most frequently reported reasons were ‘forgetting daily intake’ (68.3%), ‘gastro-intestinal side effects’ (dyspepsia, difficultly with swallowing, 25.6%) and ‘unpleasant taste or smell’ (22.7%). Moreover, 17.0% reported that scheduling their daily intake is difficult because of interactions with the calcium/vitamin D supplement or other medication. They believe that their MVS intake would improve if they could take all tablets at the same time. There was also a group of patients who reported not to use any MVS (n = 340). The majority of the non-users (52.7%) stopped taking MVS more than 1 year after surgery. Compared to MVS users with inconsistent MVS intake, non-users reported different reasons for discontinuing MVS intake (Figure 2). For non-users, gastro-intestinal side effects of MVS were a major factor (58.5%), as well as high costs (13.5%). A large part of the non-users also believed they did not require any MVS as their laboratory results are good and they feel physically fit (20.9%). In both groups, a small part of patients reduced or stopped MVS intake on advice of their specialist due to excessive serum vitamin.

Fig. 2.

Reasons for non-compliance with MVS (%). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001 (Pearson Chi-square test)

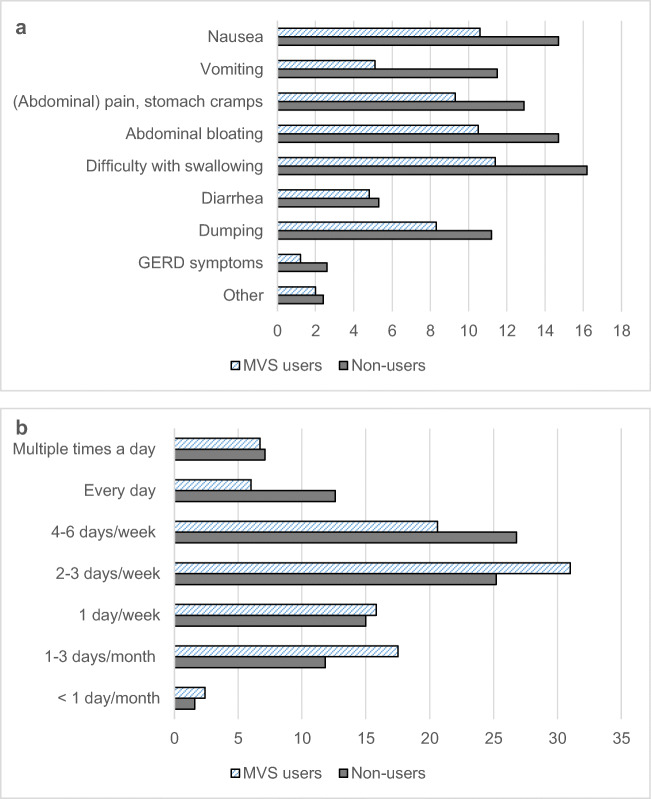

Gastro-intestinal Complaints

In this paragraph, a distinction is made between postoperative gastro-intestinal complaints in general (independent of MVS intake) and those directly related to MVS intake. General postoperative gastro-intestinal complaints (independent of MVS intake) occurred more often in non-users than in MVS users (37.4% vs. 26.3%, p < 0.001) (Figure 3a). Most reported complaints were nausea, vomiting, difficulty with swallowing, abdominal bloating, (abdominal) pain or stomach cramps and dumping. Less frequent reported complaints were diarrhea, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, belching and hiccups. The distribution of the frequency of complaints was significantly different between both groups (Figure 3b). Most non-users experienced these complaints daily while this was a few days per week or month for most MVS users (p = 0.040). Gastro-intestinal complaints that are directly related to MVS intake were reported by 58.5% of the non-users. Most frequently reported complaints were nausea (85.4%), excessive belching and hiccups (43.7%), vomiting (42.7%), difficulty with swallowing (40.2%), bloated feeling (21.1%) and reflux (18.1%). These complaints occurred immediately after ingestion (29.4%), 5–10 min after ingestion (43.8%), 15–30 min after ingestion (18.6%) or ≥ 1 h after ingestion (5.2%). For the majority, these complaints have arisen directly after starting MVS use (72.7%). After cessation of MVS intake, 61.9% was free of complaints, while complaints reduced in 12.9% and worsened in 4.1%. In 17.0%, no differences were observed.

Fig. 3.

a Post-prandial complaints of MVS users and non-users (%). Multiple answers possible. b Frequency of post-prandial complaints of MVS users and non-users (%)

Psychosocial and Economic Factors

Differences in psychosocial-related factors are described in Table 2. Of the MVS users, 10.6% of the patients were not motivated for daily MVS intake compared to 69.1% of the non-users (p < 0.001). Reasons for poor motivation were absence of deficiencies (15.9%), absence of complaints (20.8%) or a combination of both (32.4%). Other reported factors included experiencing gastro-intestinal complaints directly related to MVS use (10.4%) and the unpleasant smell, taste and/or size (2.9%). Some patients forget to take their daily MVS and some patients only take their MVS because the healthcare professional tells them they have to. Less frequent reasons are the costs of MVS and the occurrence of excessive serum vitamin A or B6. Moreover, some patients believed that they receive plenty of vitamins from their nutrition and therefore do not need to use MVS. A quarter of the non-users believe that the risk of vitamin deficiencies cannot be reduced by using MVS, compared to 9.1% of the MVS users (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Differences in psychosocial-related factors

| MVS users (n = 4274) |

Non-users (n = 340) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are you motivated to take MVS daily lifelong? | < 0.0011 | ||

| - Yes | 3819 (89.4) | 105 (30.9%) | |

| - No | 455 (10.6) | 235 (69.1%) | |

| Why are you not motivated? | |||

| - Good blood tests and no complaints | 136 (29.8) | 88 (37.4) | |

| - No complaints | 104 (22.8) | 40 (17.0) | |

| - Good blood tests | 72 (15.8) | 38 (16.2) | |

| - Gastro-intestinal complaints after MVS ingestion | 47 (10.3) | 25 (10.6) | |

| - Unpleasant smell/taste/size | 11 (2.4) | 9 (3.8) | |

| - Other | 86 (18.9) | 35 (14.9) | |

| Do you know why it is important to take MVS for life long*? | - | ||

| - To prevent vitamin deficiencies | 4058 (94.9) | 300 (88.2) | |

| - To feel fit and energetic | 1894 (44.3) | 159 (46.8) | |

| - To strengthen the immune system | 1821 (42.6) | 131 (38.5) | |

| - To lose more weight | 34 (0.8) | 8 (2.4) | |

| - Because the Obesity center tells me that I have to take them | 200 (4.7) | 38 (11.2) | |

| - I don’t know | 41 (1.0) | 16 (4.7) | |

| What disadvantages do you expect from the MVS?* | |||

| - None | 3088 (72.3) | 133 (39.1) | - |

| - Unpleasant side effects | 443 (10.4) | 120 (35.3) | |

| - The (high) costs of MVS | 719 (16.8) | 66 (19.4) | |

| - Excessive serum levels | 331 (7.7) | 32 (9.4) | |

| - It has no effect | 138 (3.2) | 44 (12.9) | |

| - The physician has shares in MVS | 66 (1.5) | 9 (2.6) | |

| - Lower weight loss | 58 (1.4) | 4 (1.2) | |

| - Other | 50 (1.2) | 8 (2.4) | |

| Do you receive emotional support for lifestyle changes after surgery*? | |||

| - No | 782 (18.3) | 105 (30.9) | |

| - Yes, from my partner | 2463 (57.6) | 171 (50.3) | |

| - Yes, from family | 2247 (52.6) | 161 (47.4) | |

| - Yes, from friends | 1618 (37.9) | 98 (28.8) | |

| - Yes, from the healthcare professionals of the Obesity Centre | 1333 (31.2) | 58 (17.1) | |

| Is your MVS intake better because of emotional support? | |||

| - Yes | 767 (22.0) | 17 (7.2) | < 0.0011 |

| - No | 2725 (78.0) | 218 (92.8) | |

Data are presented as frequencies (percentages)

MVS, multivitamin supplement

1Pearson Chi-square test

*Multiple answers were possible

The lifelong aspect of daily intake of MVS is also a barrier for many patients (38.0% vs. 60.6% for MVS users vs. non-users, p < 0.001). A majority of these patients think that their adherence would be better if the treatment period was shorter (40.3% vs. 64.6%, for MVS users vs. non-users, p < 0.001). Similar to the reported reasons for demotivation, expected disadvantages from MVS use also include the high costs (17.0%), unpleasant side effects (12.2%) and risk of excessive serum levels (7.9%). Strikingly, 72.3% of the MVS users report no disadvantages of MVS use compared to 39.1% of the non-users (p < 0.001). Most of the MVS users think that the price is acceptable (60.6%), whereas most non-users find the costs too high (61.2%) (p < 0.001). Many patients indicate that reimbursement of supplements would improve their adherence to MVS intake (38.1% vs. 43.5% for MVS users vs. non-users, p = 0.049).

Non-users are more often dissatisfied about the achieved postoperative weight loss compared to MVS users (32.9% vs. 21.0%, p < 0.001) and 14.7% believe that MVS use has influenced their postoperative weight loss (15.2% vs. 7.4% for MVS users vs. non-users, p < 0.001).

Similarly, more non-users reported to receive no emotional support for lifestyle changes after bariatric surgery compared to MVS users (30.9% vs. 18.3%, p < 0.001). However, the majority of patients (79.0%) reported that their MVS intake is not better because of this emotional support (78.0% vs 92.8% for MVS users vs. non-users, p < 0.001).

Healthcare-Related Factors

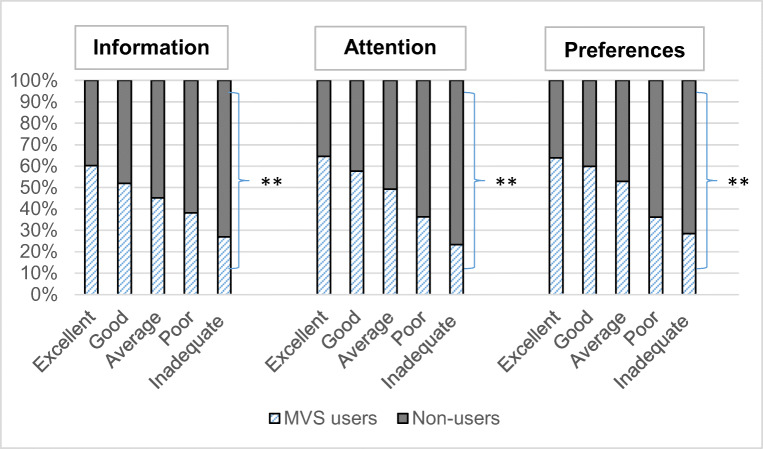

Non-users were more often dissatisfied about instructions provided about the importance of MVS use, attention paid to MVS use during medical consultation and the extent to which personal preferences of MVS use are taken into account, compared to MVS users (p < 0.001 for all, Figure 4). Most frequent reasons for scoring poorly or inadequate on one of these subscales (n=1315, 28.5%) were ‘too general information’(57.1%), ‘personal preferences not taken into account’ (51.0%) and ‘not enough time for adequate information about MVS during medical consultations’ (36.5%). Other reasons were that the patient needs to actively ask for information by themselves (28.9%) and too short consultation time (23.5%). Less frequently reported reasons were that the patient is only told what he/she is doing wrong (9.4%), they only advise one MVS formulation and do not provide alternatives (6.5%), the patient does not feel understood (5.1%) and other reasons (COVID-19 virus, topic of MVS is not discussed or ’I don’t understand the doctor’, 16.7%). Reported unclear topics were missing information about side effects (17.8%), disadvantages (12.2%) and benefits (4.9%). Moreover, patients reported that they do not know when (6.8%) or how (4.1%) to take their MVS. Some experienced a lack of information about alternative MVS options and what to do in case of complaints (3.0%). Half of all included patients reported that their healthcare professional does not ask about MVS-related complaints (50.6% vs. 42.4% for MVS users and non-users, p < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Rating scores of healthcare-related factors. **p < 0.001 (Pearson Chi-square test)

Discussion

Overall, adherence to MVS therapy is poor in 22.3% of all included patients, of which one-third did not use any MVS. This non-adherence rate is similar to the review by Zarshenas et al. (20–32%) [9, 10]. An important difference between the MVS users and non-users in this study is the time since surgery, which was shorter for MVS users. In the study by Ben-Porat et al., 92.6% of the patients took MVS during the first postoperative year, while only 37.0% took MVS after 4 years [11]. It is plausible that adherence to MVS intake is better in the first postoperative year due to an intensive follow-up, compared to multiple years after surgery when most patients are no longer supervised. The number of compliant MVS users in our study could therefore be overestimated. However, irrespective of adherence to MVS intake, the attitude of many bariatric patients towards MVS use is predominantly negative.

Barriers Influencing Adherence to MVS Intake

Most frequently reported reasons to stop taking MVS (consistently) are gastro-intestinal complaints, high costs and an unpleasant smell, taste or size. About one-third of the patients suffered from gastro-intestinal complaints and half of the patients indicated that healthcare professionals do not discuss these complaints during medical consultations, letting this problem be underexposed.

A large part of the non-users believe that they do not need to take any MVS because their laboratory results are good and they feel fit. The majority of patients understand that MVS is necessary, but not everyone seems convinced of the advantages of WLS MVS. Patients often believe that the costs of WLS MVS do not outweigh the benefits, which can lead to lower adherence. However, it has been shown by Homan et al. that adequate supplementation results in less vitamin deficiencies and reduces overall healthcare costs [12]. Total costs per patient for prevention and treatment of vitamin deficiencies were €306 (regular MVS users) vs. €216 (WLS users) every 3 months, with a chance of developing a vitamin deficiency of 30% (regular MVS) vs. 14% (WLS MVS) [12].

Dissatisfaction with medical consultations is another striking topic of this survey study. A third of the patients in our study was dissatisfied with the explanation about and awareness for MVS use. Many patients indicated that the information on MVS use is too general and limited and that their personal preferences were not taken into account. Healthcare professionals often recommend one type of WLS supplement and patients therefore cannot choose which supplement suits their preferences. All of these issues may consequently contribute to poor motivation for adequate MVS intake. The study by Osterberg et al. described that healthcare professionals contribute to patients’ poor adherence by prescribing complex medication regimens, failing to explain side effects and benefits, not giving consideration to patient’s lifestyle or the attributed costs of MVS, which may lead to a poor relationship with their patients [13]. In addition, the overall ability of healthcare professionals to recognise patient’s non-adherence is poor [13]. These findings are confirmed by our study as many patients indicated to have a lack of proper information. These healthcare-related findings are quite similar to those found in long-term adherence studies with other chronic diseases [7].

Challenges to Improve Adherence to MVS Intake

There are three different parties who can improve patient adherence to MVS intake after bariatric surgery.

First, the healthcare professionals play a large part in improving satisfaction and patient adherence to MVS intake. We need to engage to provide better education on MVS use and better shared decision making with patients after bariatric surgery. Explanation about the necessity of MVS after bariatric surgery is an essential point, but the MVS advice by healthcare professionals is often not in line with patients’ personal preferences. There are several options for using MVS, all with pros and cons, which therefore should always be discussed during consultations to increase patient satisfaction. In addition, gastro-intestinal symptoms in general or related to MVS intake should also be part of the medical consultation in order to improve patient adherence to MVS intake. Assessment, prevention and management of gastro-intestinal complaints are an important part of postoperative bariatric care, which is described in the study by Zarshenas et al. [10]. Besides that, there should be more focus on improving the relationship between patient and healthcare professional. Having knowledge of patients’ perceptions, beliefs and their personal circumstances is crucial for a decision-making process. It needs to be taken into account that the preferences of bariatric patients may differ considerably from those of the healthcare professional. Thus, the solution lies in shared decision making (SDM) [14]. SDM describes the process where the patient must be well informed, and patients’ preferences must become a more important part during medical consultations. The emphasis is not on the final decision but on the process that works towards this decision. Several studies show that SDM has a positive effect on the interaction between patient and healthcare professional. It increases patient’s level of knowledge, which leads to more accurate risk assessment of treatment options and increases patient’s assertiveness during SDM [15–19]. Application of SDM in MVS use after bariatric surgery could therefore be a breakthrough in improving the adherence.

Second, the MVS producers can increase therapy adherence by further optimizing their supplements. MVS formulas should be scrutinized due to the high percentage of gastro-intestinal side effects and an unpleasant taste and smell, which is indicated as an important barrier by many patients in our study. A significant decrease in intensity of taste and aversion to certain food types after bariatric surgery could be a contributing factor [20]. For this reason, many patients switch from WLS MVS to regular MVS. Many regular MVS have an enteric coating, which may reduce the unpleasant aftertaste that many patients suffered from. However, this type of coating is not desirable as the ability to absorb MVS is compromised after bariatric surgery [21]. A proper formula of supplements is necessary to ensure adequate absorption, which requires considerations of all drug substances and pharmaceutical ingredients [22]. An ideal combination of taste, appearance and colour in supplements will contribute to its acceptance [23]. MVS manufacturers must investigate how these aspects can be improved while simultaneously ensuring adequate absorption.

Third, insurance companies could contribute to the improvement of patient adherence to MVS intake by reimbursing supplements. Costs are a frequently reported reason for patients to stop using specialised WLS MVS. Reimbursement of supplements with proven effectiveness could improve the therapy adherence, which is indicated by many patients in our study. Therefore, healthcare authorities involved in the reimbursement of bariatric procedures should consider integrating costs of WLS MVS with postoperative follow-up. We believe that only reimbursing WLS MVS with proven effectiveness, based on extensive scientific research, should be considered. This reimbursement will motivate many patients to switch to WLS MVS.

Strengths

All consecutive postoperative patients were recruited to avoid selection bias. Participation was anonymous; no information from the electronic patient file was retrieved. There was no risk or personal benefit, which reduced the risk of giving socially desirable answers. To provide accurate assessment of vitamin intake, the questions were designed with a free-text field option to avoid too limited answers possibilities. Because patients from four hospitals were included, the external validity of this study is high and results can be used by many (inter)national obesity centers.

Limitations

A total of 10,810 patients (70.1%) did not participate. It is unclear whether these patients use a MVS. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery is poor despite clear international guidelines [24]. No validated questionnaire was used, as such a questionnaire does not exist. However, our survey study was intended to get a first impression of factors influencing adherence to MVS intake and analyze various topics for advice in daily practice. A validated questionnaire was therefore not required. This questionnaire contained only self-reported patient data and provides subjective information who cannot be verified due to the anonymous character, which can cause underestimation or overestimation.

Future Perspectives

These results can be used for further hypothesis-generating research and perform research into the influence of different bariatric procedures (primary vs. revision surgery) and time after surgery on patient adherence to MVS intake. It is important to analyze which patient groups are at higher risk for poor adherence to MVS intake and whether the percentage of vitamin deficiencies is higher in patients who do not use any MVS. The relationship between patient and healthcare professional and discrepancies between experiences from both perspectives are also important topics for further clarification. Finally, the development of tools supporting SDM in MVS choices is important as well.

Conclusion

The attitude of many bariatric patients towards MVS use is predominantly negative. A large proportion of patients are dissatisfied about the advices on MVS intake during medical consultations and that patients’ personal preferences are often not taken into account. High costs, no reimbursement and gastro-intestinal complaints lead to poor motivation for MVS intake. Gastro-intestinal side effects, good laboratory results and an unpleasant taste and smell are the most frequently reported reasons for the discontinuation of MVS intake. It is important to take patient’s preferences into account and to provide more extensive information about different possibilities in MVS use. Challenges lie in improving patient adherence by implementing SDM in MVS use, further optimization of WLS MVS formulas and exploring options for reimbursement, which could be major factors in reducing vitamin deficiencies following bariatric surgery.

Appendix 1.

Questionnaire

| General information |

- Age (years) - Gender (male / female) - Marital status - Education level - Profession - Current body weight (kilogram) - Length (centimeters) - Type of bariatric surgery - Date of surgery (month + year) |

| Patient related factors |

- Do you suffer from gastro-intestinal complaints after your meals. If so, which complaints? (e.g. nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea) - How often do you have these complaints? |

| MVS related factors |

- Do you take a MVS? - Which MVS do you use? - Which form of MVS do you take? - How many MVS do you take per day? - What do you think of the number of MVS you have to take per day? - When do you take the MVS? - How do you take the MVS? - Do you take the MVS separately from calcium/vitamin D? - Do you take the MVS with other medication? - How often do you take your MVS? For patients who not take the MVS daily: - Why is it not possible to take the MVS daily? - If you experienced complaints after taking MVS, which complaints are involved? - When did these complaints start? - At what time do you start to feel complaints from the MVS? - Why did you stop taking MVS? - How do you feel since you stopped or switch your MVS? For patient who never take MVS: - When did you stop taking MVS? - If you experienced complaints after taking MVS, which complaints are involved? - When did these complaints start? - At what time do you start to feel complaints from the MVS? - Why did you stop taking MVS? - How do you feel since you stopped or switch your MVS? |

| Psychosocial and economic factors |

- Are you motivated to take the MVS daily and lifelong? - Do you find it annoying that your MVS use is necessary lifelong? - Why are you not motivated? - Do you know why it is important to take MVS lifelong? - Do you think you can reduce the risk of vitamin deficiencies by using the MVS consistently? - What disadvantages do you expect from MVS use? - What do you think about the costs of your MVS? Are these costs acceptable to you? - Would you take the MVS better if the treatment period is shorter (thus not life-long)? - Do you think that reimbursement of MVS would improve your adherence to MVS intake? - Are you satisfied about the achieved postoperative weight loss? - Do you think that MVS use has influenced this weight loss? - Do you receive emotional support for lifestyle changes after surgery? - Is your MVS intake better because of this emotional support? |

| Healthcare related factors |

- How do you rate the received explanation from the healthcare professionals about using MVS? If not/less satisfied: why are you less or not satisfied? - How do you rate the attention paid to your MVS use during medical consultations? If not/less satisfied: why are you less or not satisfied? - How do you rate the extent to which your personal preferences are taken into account by the healthcare professionals about your MVS use? If not/less satisfied: why are you less or not satisfied? - Does the healthcare professional ask about gastro-intestinal complaints due to MVS use during medical consultations? - Which points are unclear about MVS use in your opinion? |

MVS = multivitamin supplement

Author Contribution

Designed study: HJMS, LH, SP, JFS, EJH

Patient inclusion: HJMS, LH, WT, PWJR, TN

Conducted research and interpretation data: HJMS, LH

Drafted the article: All authors

Primary responsibility for final content: All authors

All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The non-WMO statement was approved by the Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen (2020-6690). Local ethical approval was obtained by all participating hospitals: Catharina Hospital Eindhoven (nWMO-2020.130), Rijnstate Arnhem (2020-1667), Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland (2020-076) and Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis (WO 20.209).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Key Points

- In total, 15.4% reported inconsistent MVS use and 7.4% did not use any MVS

- Forgetting, gastro-intestinal side effects and costs are the most frequent reasons

- In total, 28.5% dissatisfaction about medical consultation

- The relationship between patient and healthcare is disrupted

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

HJM Smelt and L. Heusschen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

H. J. M. Smelt, Email: marieke.smelt@catharinaziekenhuis.nl

L. Heusschen, Email: lheusschen@rijnstate.nl

W. Theel, Email: w.theel@franciscus.nl

P.W.J. van Rutte, Email: P.w.j.vanrutte@olvg.nl

T. Nijboer, Email: T.nijboer-burgers@olvg.nl

S. Pouwels, Email: sjaakpwls@gmail.com

J. F. Smulders, Email: frans.smulders@catharinaziekenhuis.nl

E. J. Hazebroek, Email: ehazebroek@rijnstate.nl

References

- 1.Genser L, Barrat C. Long term outcomes after bariatric and metabolic surgery. Presse Med. 2018;47(5):471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM, Livingston E, Salvador J, Still C. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4823–4843. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, Timothy Garvey W, Hurley DL, Molly McMahon M, Heinberg LJ, Kushner R, Adams TD, Shikora S, Dixon JB, Brethauer S. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient--2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(2):159–191. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aills L, Blankenship J, Buffington C, Furtado M, Parrott J. ASMBS Allied Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5 Suppl):73–108. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schijns W, Schuurman LT, Melse-Boonstra A, van Laarhoven C, Berends FJ, Aarts EO. Do specialized bariatric multivitamins lower deficiencies after RYGB? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(7):1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heusschen L, Schijns W, Ploeger N, Deden LN, Hazebroek EJ, Berends FJ, Aarts EO. The true story on deficiencies after sleeve gastrectomy: results of a double-blind RCT. Obes Surg. 2020;30(4):1280–1290. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smelt HJM, Pouwels S, Smulders JF, Hazebroek EJ. Patient adherence to multivitamin supplementation after bariatric surgery: a narrative review. J Nutr Sci. 2020;9:1–8. doi: 10.1017/jns.2020.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, Chuen Li S. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: a review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(1):269–286. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James H, Lorentz P, Collazo-Clavell ML. Patient-reported adherence to empiric vitamin/mineral supplementation and related nutrient deficiencies after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26(11):2661–2666. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zarshenas N, Tapsell LC, Neale EP, Batterham M, Talbot ML. The relationship between bariatric surgery and diet quality: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2020;30(5):1768–1792. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04392-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben-Porat T, Elazary R, Goldenshluger A, Sherf Dagan S, Mintz Y, Weiss R. Nutritional deficiencies four years after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy-are supplements required for a lifetime? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(7):1138–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Homan J, Schijns W, Janssen IMC, Berends FJ, Aarts EO. Adequate multivitamin supplementation after Roux-En-Y gastric bypass results in a decrease of national health care costs: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Obes Surg. 2019;29(5):1638–1643. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-03750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan JL, Blake DR. Patient non-compliance: deviance or reasoned decision-making? Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(5):507–513. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joosten EA, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP, de Jong CA. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(4):219–226. doi: 10.1159/000126073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7) 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):1–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4(4):Cd001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knops AM, Legemate DA, Goossens A, Bossuyt PM, Ubbink DT. Decision aids for patients facing a surgical treatment decision: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;257(5):860–866. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182864fd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tichansky DS, Boughter JD, Jr, Madan AK. Taste change after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2(4):440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth DE, Pezzack B, Al Mahmud A, Abrams SA, Islam M, Aimone Phillips A, et al. Bioavailability of enteric-coated microencapsulated calcium during pregnancy: a randomized crossover trial in Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(6):1587–1595. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.090621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lizer MH, Papageorgeon H, Glembot TM. Nutritional and pharmacologic challenges in the bariatric surgery patient. Obes Surg. 2010;20(12):1654–1659. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen LV., Jr Dosage form design and development. Clin Ther. 2008;30(11):2102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thereaux J, Lesuffleur T, Païta M, Czernichow S, Basdevant A, Msika S, Millat B, Fagot-Campagna A. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery in a national cohort. Br J Surg. 2017;104(10):1362–1371. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]