Abstract

Increases in cancer diagnosis have tremendous negative impacts on patients and their family and major societal and economical costs. The beneficial effect of chemotherapeutic agents on tumor suppression comes with major unwanted side effects such as weight and hair loss, nausea and vomiting and neuropathic pain. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), which can include both painful and non-painful symptoms, can persist six months or longer after patient’s last chemotherapeutic treatment. These peripheral sensory and motor deficits are poorly treated by our current analgesics with limited effectiveness. Therefore, the development of novel treatment strategies is an important pre-clinical research focus and urgent need for patients. Approaches to prevent CIPN have yielded disappointing results since these compounds may interfere with the anti-tumor properties of chemotherapeutic agents. Nevertheless, the first (serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRIs), anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressant) and second (5 % lidocaine patches, 8 % capsaicin patches and weak opioids such as tramadol) lines of treatment for CIPN have shown some efficacy. The clinical challenge of CIPN management in cancer patients and the need to target novel therapies with long term efficacy in alleviating CIPN is an ongoing research focus. The endogenous cannabinoid system has shown great promise and efficacy in alleviating CIPN in preclinical and clinical studies. In this review, we will discuss the mechanisms through which the platinum, taxane, and vinca alkaloid classes of chemotherapeutics may produce CIPN, and the potential therapeutic effect of drugs targeting the endocannabinoid system in preclinical and clinical studies, in addition to cannabinoid compounds diffuse mechanisms of action in alleviation of CIPN.

1. Introduction

The societal and economic impact of cancer and its treatment is tremendous. The American Cancer Society estimates 1.7 million new diagnoses and 600,000 deaths from cancer in 2018 [1]. Of these cases, a majority will utilize chemotherapy as part of the treatment regimen. In addition to the weight and hair loss, nausea and vomiting, and low energy associated with chemotherapy, 40–80% of patients will develop neuropathic pain in the form of chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) within 3–6 months into their chemotherapeutic treatment [2, 3]. CIPN commonly manifests in the hands and feet with symptoms favoring sensory over motor deficits (Fig. 1). Sensory deficits may present as a loss of sensation, a heightened response to pain (hyperalgesia) or painful response to ordinarily innocuous stimulation (allodynia) leading to chronic pain in cancer patients [3]. Symptoms of CIPN may not abate after discontinuation of the chemotherapy, a phenomenon referred to clinically as “coasting” [4]. Indeed, studies confirmed that 30–40 % of patients experienced CIPN six months or longer after discontinuation of chemotherapeutic treatment according to a systemic review and meta-analysis by Seretny and collaborators [5, 6]. Chronic pain altogether afflicts more than 120 million Americans and is extremely costly to our society, amounting to $600 billion annually in medical expenses, in addition to loss of work productivity and long-term insurance disability [7, 8].

Fig. 1: Current and prospective treatments for CIPN.

Current treatments for CIPN are limited, the SNRIs with duloxetine being the primary option. Numerous clinical trials investigating prospective treatments are recruiting or in progress currently. A wide variety of potential treatment options are being considered from drugs and natural products, to mechanical and electrical stimulation.

Despite the prevalence of CIPN in cancer patients being estimated between 19 to 85 % [9], relatively few treatments exist and have limited efficacy. Therefore, the development of novel treatment strategies is an essential pre-clinical research focus. Unfortunately, approaches to prevent CIPN have yielded disappointing results due to interference of analgesic compounds with the anti-tumor properties of chemotherapeutic agents [10, 11]. The first line of treatments for CIPN include: SNRIs (serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors) primarily duloxetine, anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin), and tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline) [12, 13](Fig. 1). The second line of treatments include: 5 % lidocaine patches, 8 % capsaicin patches and weak opioids, primarily tramadol [12](Fig. 1). The third line of treatment is strong opioids which carry a high potential for side effects, addiction, and dependence [12, 14](Fig. 1). With these limited treatment options, the management of CIPN in cancer patients is clinically challenging and remains a burden for patients and clinicians, particularly due to the absence of long-term effective therapies which lack major unwanted side effects such as abuse potential [15, 16]. In fact, the current analgesics used for CIPN are ineffective approximately 70 % of patients [12, 17]. It is clear that there is still a great need for development of long lasting, highly efficacious and personalized pain therapies.

Consequently, cannabis and cannabinoid based pharmacotherapies have received a great amount of enthusiasm in the past decade as potential novel treatments for a variety of conditions including chronic pain, muscle spasticity, and chemotherapy associated nausea and vomiting [18–20]. Canada and 34 states in the United States including Washington D.C., and the territories of Guam and Puerto Rico, have introduced laws to allow medical use of cannabis to treat disease or alleviate symptoms [21, 22]. Products in the cannabinoid class range from whole-plant cannabis flower or cannabis extracts, such as Nabiximols (Sativex), to synthetics delivered as capsules (nabilone and dronabinol) [23]. There is strong evidence supporting the use of cannabinoids for the treatment of chronic pain due to chemotherapy [20–22, 24]. Moreover, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a report in January 2017 outlining the health effects of cannabinoids and cannabis as medicine in a variety of conditions [25]. The committee of experts concluded in their final report that conclusive evidence exists in favor of the effectiveness of cannabis or cannabinoid compounds for the treatment of chronic pain, emesis, and patient-reported muscle spasticity from multiple sclerosis (MS) [25]. It is clear that compounds targeting the endocannabinoid system show great promise as a novel class of medications, particularly in pain, at a time when novel treatments are desperately needed. In this review, we will discuss the mechanisms by which the platinum, taxane, and vinca alkaloid classes of chemotherapeutics may produce CIPN, the potential therapeutic effect of drugs targeting the endocannabinoid system in preclinical and clinical studies, and alleviation of CIPN by cannabinoid compounds with broad mechanisms of action.

2. Specific cancers targeted by the three classes of chemotherapeutic agents

This review focuses on three classes of chemotherapeutics: the platinums, taxanes, and vinca alkaloids (Fig. 2). The platinum (cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin) compounds are used for the treatment of anal, colon, endometrial, hepatobiliary and pancreatic cancers, in addition to lymphoma, osteogenic sarcoma, and medulloblastoma [26](Fig. 2). The taxane class (paclitaxel, docetaxel) are beneficial in the treatment of cancers of the prostate and fallopian tube, peritoneal neoplasm [26] and triple negative breast cancer [27, 28](Fig. 2). The vinca alkaloids (vincristine, vinblastine) are used for the treatment of lymphoblastic leukemia, choriocarcinoma, retinoblastoma, pheochromocytomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, and ovarian germ cell cancers [26](Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Types of cancer treated with chemotherapeutic agents.

The three classes of chemotherapeutic agents: platinum, taxane and vinca alkaloid and the different types of cancer treated.

There is considerable overlap between these three classes of chemotherapeutics and the types of cancer they are indicated for [26]. The platinum and vinca alkaloids are both used in the treatment of lymphocytic leukemia, lymphoma (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin), neuroblastoma, multiple myeloma and hepatoblastoma (Fig. 2). Moreover, the platinum and vinca alkaloids compounds are used in treatment of adrenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, esophageal, stomach, penile, and ovarian cancers. Finally, the taxane and vinca alkaloids compounds are both used to treat sarcoma and thymoma (Fig. 2). All three classes of chemotherapeutics are indicated in treatment of aggressive, metastatic cancers including bladder, breast, melanoma, pancreatic, testicular and lung (small cell, non-small cell) cancers (Fig. 2). The three classes of chemotherapeutic agents may be employed in combination with other chemotherapeutics, along with other targeted therapies including surgery and radiation, as well as immunotherapy or hormonal therapy [26]. As with their indications, the three classes of chemotherapeutics also share considerable overlap in general mechanisms of action, in addition to mechanisms that are specific to each class.

3. Chemotherapeutic agent mechanisms of action

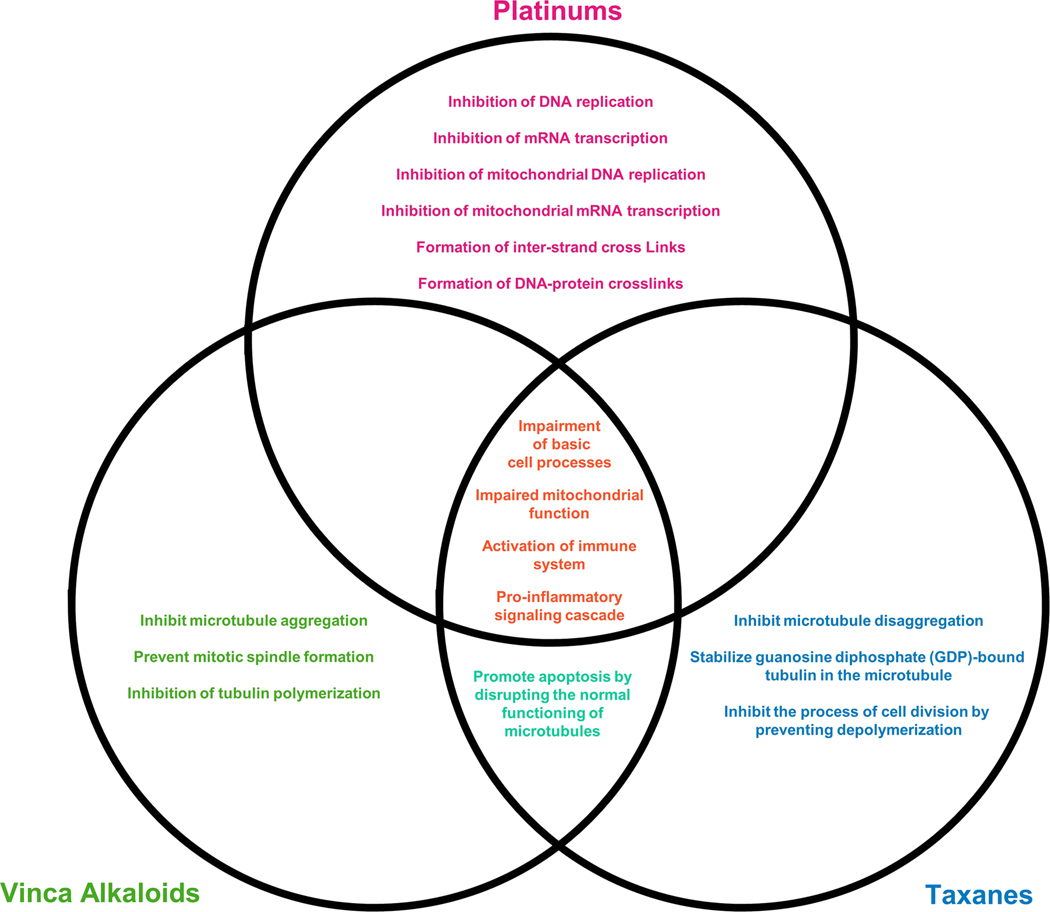

The three classes of chemotherapeutic agents (platinum, taxanes, and vinca alkaloids) share a common global mechanism of action; interference with normal cell processes that ultimately drives cancer cells towards apoptosis (Fig. 3). Platinum compounds form complexes with both nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, interfering with key cell processes such as transcription and translation, leading to dysfunction in cell machinery ultimately driving the cell towards apoptosis [29](Fig. 3). The taxane and vinca alkaloid compounds promote apoptosis by disrupting the normal functioning of microtubules; cell machinery critical for cell shape, transportation of cell cargo, and cell replication and division [30]. All three classes induce apoptosis through the disruption of normal cell processes resulting in increased activation of immune cells (macrophages, T lymphocytes (T cells), and monocytes), leading to pro-inflammatory signaling cascade (interleukins, cytokines, and others) that promote cell death [31] (Fig. 3). These chemotherapeutics lack specificity and cannot specifically target cancer cells exclusively. Consequently, this gives rise to chemotherapy-induced neuropathy (CIPN), one of the side effects caused by the damage of healthy cells such as sensory neurons.

Fig. 3: Mechanisms of action of chemotherapeutic agents.

The three classes of chemotherapeutic agents (platinum, taxane and vinca alkaloid) all interfere with normal cell processes in order to drive cancer cells towards apoptosis.

4. Chemotherapy Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN)

The mechanisms of induction of neuropathic pain for these three classes of chemotherapeutic agents have been reviewed in depth [12, 31]. Two broad mechanisms of induction of neuropathic pain have been distinguished: 1) neuronal inflammation and 2) altered excitability of peripheral neurons (Fig. 4). The activation of the immune system leading to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines has been hypothesized to be one mechanism producing epidermal fiber loss following treatment with platinum compounds [32], as well as taxanes and vinca alkaloids [33] (Fig. 4). Glial cell activation is increased in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia following oxaliplatin [34] and paclitaxel treatments [35] (Fig. 4). T cell expression is also affected by treatment with paclitaxel [36]. Notably, the persistence of paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia, defined as an increased sensitivity to pain upon application of a monofilament to the hind paw, is lengthened in T cell deficient (Rag1−/−) mice compared to wild type [37]. Moreover, mechanical allodynia following paclitaxel treatment can be reversed by the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 10 (IL-10) [37, 38].

Fig. 4: Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy.

The mechanisms by which chemotherapeutics destroy cancer cells also result in damage of peripheral neurons. Inhibition of normal vital cell processes such as cell division and respiration promotes pro-inflammatory and apoptotic signaling cascades and altered excitability of peripheral neurons. Peripheral sensitization of nociceptive neurons may result in long term changes in the spinal cord and brain, resulting in chronic pain.

The activation of the immune system and the pro-inflammatory signaling cascades can directly sensitize peripheral neurons, resulting in allodynia (Fig. 4). Increases in chemokines C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12) [39], fractalkine (CX3CL1) [40] and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) [41] have been observed following treatment with the microtubule targeting chemotherapeutics vincristine and paclitaxel (Fig. 4). These chemokines may potentiate nociceptive responses via recruitment of immune cells, such as microglia, that promote a pro-inflammatory state.

One week following paclitaxel administration, significant increases in pro-inflammatory immune cells have been found in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [42]. The mechanical allodynia observed after paclitaxel treatment has been correlated with an increase in spontaneous firing of DRG cells resulting in part by an increased expression of excitatory sodium channels and decreases in inhibitory potassium channels [43]. Changes in transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channel function have also been associated with the cold allodynia characteristic of oxaliplatin treatment, specifically the transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 8 (TRPM8) receptor [44, 45], in addition to the transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) receptor which has been associated with both mechanical and cold allodynia in oxaliplatin models [45, 46](Fig. 4). Following cisplatin and oxaliplatin treatment, increases in transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1) expression in the dorsal root- and trigeminal ganglia of mice were associated with both heat and mechanical hypersensitivity [47]. Alterations in mitochondria have been observed following treatment with paclitaxel [48], cisplatin [49], and vincristine [33]. Changes in mitochondrial function can result in the over production of reactive oxygen species in the DRG which may then alter ion channels and promote a hyperexcitable state in nociceptive neurons [48, 50](Fig. 4).

While various pharmacological approaches exist to alleviate pain such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, anticonvulsants, antidepressants and local anesthetics, the broad neuromodulatory role of the endocannabinoid system offers a novel treatment avenue [12, 51, 52](Fig. 1). Evidence is mounting that the use of compounds targeting the endocannabinoid system constitute a new class of therapeutics to add to the pharmaceutical toolbox in the management of chronic pain [24, 53].

5. The Endocannabinoid System

The endocannabinoid system is a broadly active neuromodulatory system, playing a key role in pain modulation as well as inflammatory processes mediated by the immune system. The endocannabinoid system is comprised of the enzymes responsible for the synthesis and catabolism of the endocannabinoid ligands, the ligands themselves, and the receptors upon which the ligands act [18, 54]. The two best characterized endocannabinoids are anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) [55]. In the brain, endocannabinoids are synthesized ondemand from membrane phospholipids (i.e. not stored in synaptic vesicles) and act primarily in a retrograde fashion; synthesis occurs in the postsynaptic neuron and the ligand activates cannabinoid receptors in the presynaptic neuron [56]. Anandamide is then degraded by the catabolic enzyme fatty-acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) and 2-AG by monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL) [54].

The G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) [57, 58] and cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) [59] are the site of action for much of the action of the endocannabinoids, though other orphan G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ligand-gated ion channels, such as TRPV1, are also activated and modulated by the same ligands [60, 61]. CB1 and CB2 receptors produce a net inhibitory effect on cell excitability through inhibition of both voltage gated calcium channels [62] and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) generation by adenylyl cyclase [63], in addition to stimulation of G protein-coupled inward rectifying potassium channels (GIRKs) [64, 65].

While activation of the CB1 receptor is responsible for the psychoactive effect of cannabis, the CB1 receptors are expressed throughout the brain and spinal cord in key areas responsible for pain transmission and modulation. CB1 receptor is expressed on neurons throughout the spinothalamic pain pathway from peripheral Aδ and C fibers and dorsal root ganglia [66], substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord dorsal horn [67], ventral posterolateral (VPL) nucleus of the thalamus [68], rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) [69], and cortex [70], in addition to pain-modulatory areas such as the amygdala [71] and periaqueductal gray [72] (Fig. 5). Studies utilizing selective CB1 receptor agonists (arachidonyl-2’-chloroethylamide (ACEA), AM9405) have been shown to alleviate pain [73, 74], but the central expression of the CB1 receptor results in psychoactive effects that negatively impact their usefulness. Conversely, CB2 receptor expression is non-neuronal; the receptor is expressed on glia, immune cells and peripheral tissues, but not on central nervous system (CNS) neurons in areas responsible for cognition, attention, and other higher-order functions [75]. For this reason, CB2 selective ligands show promise as future therapeutic agents with the capacity to relieve pain without the psychoactive effect characteristic of CB1 agonism [76]. Mixed CB1/CB2 receptor agonists such as delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), have also been shown to alleviate pain, but again are limited in their usefulness due to psychoactive effects [35, 51, 77–79].

Fig. 5: Cannabinoid mechanisms in pain.

Cannabinoid receptors are present throughout the brain, spinal cord, and periphery. Cannabinoid-mediated analgesia involves complicated cross-talk between various brain structures, neurotransmitter systems and receptors, and immune and glial cells.

Engaging the endogenous cannabinoid system has also been explored using selective inhibitors of enzymes responsible for endocannabinoid catabolism; fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) for anandamide (AEA) and monoacylglycerol lipase (MGL) for 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG). Selective FAAH and MAGL inhibitors produce antinociceptive effects in acute, inflammatory and neuropathic pain models [80, 81], and this antinociceptive effect is amplified when both enzymes are inhibited simultaneously [82, 83]. Specific to the focus of this review, compounds targeting the endocannabinoid system have been shown to be efficacious in treating CIPN in preclinical studies. They are acting through inhibition of immune-mediated processes such as pro-inflammatory signaling that sensitize the nociceptive pathway, as well as by direct modulation of the nerves in pain pathways and facilitation of descending inhibitory pain processes.

6. Targeting the Endocannabinoid System in Animal CIPN Models

Endocannabinoids, inhibitors of endocannabinoid degradation, synthetic cannabinoids and phytocannabinoids (plant-derived) have shown efficacy in rodent models of CIPN induced by the platinum, taxane, and vinca alkaloid classes of chemotherapeutic agents [77, 80, 84]. CIPN can be measured behaviorally in rodents as changes in thermal (cold or heat) and mechanical sensitivity, proprioception, and motor performance. The changes in thermal sensitivity can be quantified as a decrease in latency to withdraw the paw away from a hot surface, or increased time spent attending to (i.e. licking/biting/shaking) the paw following application of a drop of acetone to the plantar surface, which produces a cold sensation upon evaporation [76]. Changes in mechanical sensitivity are commonly evaluated using calibrated monofilaments (von Frey) applied to the plantar surface of the paw, and the force required to elicit a paw withdrawal response is measured [85]. Proprioceptive and motor performance changes can be measured by decreased performance in tasks such as balance beam [86] or ladder walking and grip strength, which is evaluated using a specialized grip strength meter [87]. Histology and electrophysiology can be employed to further characterize changes in nerve morphology or action potential conduction [43].

6.1. Platinum Compounds

Alleviation of CIPN by compounds targeting the endocannabinoid system has been demonstrated in the cisplatin and oxaliplatin rodent models (see Table 1 for details). More specifically, cannabidiol, a phytocannabinoid without significant agonism toward either CB1 or CB2 receptors, has been shown to alleviate mechanical allodynia in the cisplatin model, with proposed mechanisms mediated through agonist-induced desensitization of the TRPV1 receptor, agonism at 5-HT1A receptors and modulation of glycine receptors, among others [88]. The CB1 agonists, ACEA and PrNMI, were also effective in reversing the cisplatin-induced mechanical and cold allodynia as well as heat hyperalgesia [73, 89]. This antinociceptive effect of ACEA is mediated by CB1 receptors [73] whereas PrNMI’s effect is mediated by both CB1 and CB2 receptors [89]. CB2 agonists (AM1710 and JWH-133) have also been shown to alleviate mechanical and cold allodynia and heat hyperalgesia in the cisplatin model [73, 90]. This antinociceptive effect is mediated by CB2, but not CB1 receptors [73, 90]. The mixed cannabinoid receptor 1 and 2 (CB1/2) agonists (Δ9-THC, CP55,940 and WIN55,212–2) have also been shown to reverse mechanical and cold allodynia and heat hyperalgesia in cisplatin-induced neuropathy [73, 88, 91, 92]. These antinociceptive effects of these mixed agonists are mediated by both CB1 and CB2 receptors [73]. A recent study also shows that G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) and β-arrestin2 could be responsible for the desensitization of CB1 receptors which would contribute to the rate at which tolerance develops to the antinociceptive effects of CB1 or CB1/2 agonists, such as WIN55,212–2 [92]. Exogenous intraplantar administration of endocannabinoids (anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG)) has also been shown to reverse mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia through CB1 but not CB2 receptors [93, 94]. Both centrally active (URB597) and peripherally restricted (URB937) FAAH inhibitors were found to alleviate mechanical and cold allodynia as well as plantar heat hyperalgesia in the cisplatin model [80, 93, 95]. Some studies linked this antinociceptive effect to selective activation of CB1 receptor [93, 95], whereas we observed that the anti-allodynic effect is attributed to the activation of both CB1 and CB2 receptors [80]. MGL inhibitors such as JZL184 have been used to alleviate mechanical and cold allodynia [80, 94]. Again, whether the antinociceptive effect of JZL184 is mediated by CB1 receptors only [94] or also involves both CB1 and CB2 receptors [80] remains under investigation. The discrepancies in the mechanisms of action of FAAH and MGL inhibitors could be partially explained by the differences in the route of administration (intraplantar versus systemic), the dose used, and differences in methodology assessing mechanical allodynia. Alleviation of the mechanical allodynia associated with oxaliplatin treatment has also been demonstrated using cannabidiol (CBD) and Δ9-THC administered alone or in combination; supporting evidence that the antinociceptive effect of cannabinoids is not limited to just one type of chemotherapy treatment [84].

Table 1:

Preclinical cannabinoid studies in platinum-induced peripheral neuropathy

| Platinum | Dosage days | Exp. Time | Species | Sex | Drugs | Pharm. Specificity | Dose | Antinociception | Pain | Mediated by: | Tetrad | Dosage | Markers | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemo agent | Mice or Rat | M/F | Route | Test | CB1 | CB2 | or WD | Endo | Inflammation/others | ||||||

| Cisplatin | 2.3 mg/kg i.p. 9 times every other day | 18 days | Mice C57Bl6 | M | Cannabidiol (CBD) | phytocannabinoid | 2 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [88] |

| Cisplatin | 2 mg/kg i.p 1/week for 5 weeks | 5 weeks | Rat Wistar | M | ACEA | CB1 agonist | 1 mg/kg i.p.; 50 μg/25 μl i.pl. | Yes Von Frey only | Von Frey and plantar heat | Yes AM251 i.p. and i.pl. | NT | Yes | NT | NT | [73] |

| Cisplatin | 3 mg/kg i.p. 1/week for 4 weeks | 4 weeks | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M and F | PrNMI | CB1 agonist p-r | 0 to 3 mg/kg i.g.; 0 to 2 mg/kg i.p.; 0.25 mg/kg i.pl. | Yes | Von Frey and acetone | Yes SR141716 3 mg/kg i.g. | Yes SR144528 3 mg/kg i.g. | Yes | NT | CB1; CB2: NapePLD;DAGLα; MGL; FAAH | [89] |

| Cisplatin | 3 mg/kg i.p. weekly | 4 weeks | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | AM1710 | CB2 agonist | 0.1 to 5 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and acetone | No AM251 3 mg/kg i.p. | Yes AM630 3 mg/kg i.p. | NT | NT | NT | [90] |

| Cisplatin | 2 mg/kg i.p. 1/week for 5 weeks | 5 weeks | Rat Wistar | M | JWH-133 | CB2 agonist | 1 mg/kg i.p. and 50 μg/25μl i.pl. | Yes Von Frey only | Von Frey and plantar heat | NT | Yes SR144528 i.p. and i.pl. | Yes | NT | NT | [73] |

| Cisplatin | 1 or 2 mg/kg i.p. 1/week for 5 weeks | 5 weeks | Rat Wistar | M | WIN55,212–2 | CB1/2 agonist | 1 or 2 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | Yes | NT | NT | [91] |

| Cisplatin | 2 mg/kg i.p. 1/week for 5 weeks | 5 weeks | Rat Wistar | M | WIN55,212–2 | CB1/2 agonist | 1 mg/kg i.p. and 50 μg/25μl i.pl. | Yes Von Frey only | Von Frey and plantar heat | Yes AM251 i.p. and i.pl. | Yes SR144528 i.p. No for i.pl. | Yes | NT | NT | [73] |

| Cisplatin | 5 mg/kg i.p. 1/week for 3 weeks | 25 days | Mice C57Bl6 S426A/S430A | M | WIN55,212–2 | CB1/2 agonist | 3 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | Yes | NT | NT | [92] |

| Cisplatin | 5 mg/kg i.p. 1/week for 3 weeks | 19 days | Mice C57Bl6 S426A/S430A | M | CP55,940 | CB1/2 agonist | 0.3 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | Yes | NT | NT | [92] |

| Cisplatin | 2.3 mg/kg i.p. 9 times every other day | 18 days | Mice C57Bl6 | M | Delta 9- tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) | CB1/2 agonist | 2 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [88] |

| Cisplatin | 1 mg/kg i.p. 7 times daily | 7 days | Mice C3H/HeN | M | AEA | endocannabinoid | 10 μg/10μl i.pl. | Yes | Von Frey and plantar heat | Yes AM281 10μg/10μl i.pl | No AM630 4 μg/10μl i.pl. | NT | AEA decrease paw (cisplatin) | TRPV1 ATF-3-ir p-NF | [93] |

| Cisplatin | 1 mg/kg i.p. 7 times daily | 7 days | Mice C3H/HeN | M | URB597 | FAAH inhibitor | 9 μg/10μl i.pl.; 0.3 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and plantar heat | Yes AM281 10 μg/10μl i.pl. or 0.33 mg/kg i.p. | No AM630 4 μg/10μl i.pl. | NT | AEA increase DRG (URB597) | TRPV1 ATF-3-ir p-NF | [93] |

| Cisplatin | 3 mg/kg i.p. 1/week for 2 weeks | 16 days | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | URB597 | FAAH inhibitor | 0.1 or 1 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and acetone | Yes AM251 3 mg/kg i.p. | Yes AM630 3 mg/kg i.p. | NT | AEA increase spinal cord (cisplatin) | CB1; CB2; FAAH; MGL; TRPA1; TRPV1 | [80] |

| Cisplatin | 3 mg/kg i.p. 1/week for 2 weeks | 16 days | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | URB937 | FAAH inhibitor p-r | 0.1 or 1 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and acetone | Yes AM251 3 mg/kg i.p. | Yes AM630 3 mg/kg i.p. | NT | AEA increase spinal cord (cisplatin) | CB1; CB2; FAAH; MGL; TRPA1; TRPV1 | [80] |

| Cisplatin | 1 mg/kg i.p. 7 times daily | 7 days | Mice C3H/HeN | M | URB597 | FAAH inhibitor | 9 μg/10μl i.pl. | Yes | Von Frey | Yes AM281 10 μg/10μl i.pl. | No AM630 10 μg/10μl i.pl. | NT | AEA increase paw (cisplatin +URB597) | NT | [95] |

| Cisplatin | 1 mg/kg i.p. 7 times daily | 7 days | Mice C3H/HeN | M | 2-AG | encocannabinoid | 18μg/10μl i.pl. | Yes | Von Frey | Yes AM281 10μg/10μl i.pl. | No AM630 4 μg/10μl i.pl. | NT | 2-AG and AEA decrease DRG and skin (cisplatin) | NT | [94] |

| Cisplatin | 1 mg/kg i.p. 7 times daily | 7 days | Mice C3H/HeN | M | JZL184 | MGL inhibitor | 10μg/10μl s.c. paw or i.pl. | Yes | Von Frey | Yes AM281 0.33 mg/kg i.p. or 10μg/10μl i.pl. | No AM630 1 mg/kg i.p. or 4 μg/10μl i.pl. | NT | 2-AG increase DRG (cisplatin+JZL184) | NT | [94] |

| Cisplatin | 3 mg/kg i.p. 1/week for 2 weeks | 16 days | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | JZL184 | MGL inhibitor | 1, 3 and 8 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and acetone | Yes AM251 3 mg/kg i.p. | Yes AM630 3 mg/kg i.p. | NT | 2-AG increase s. c. and decrease paw (cisplatin) | CB1; CB2; FAAH; MGL; TRPA1; TRPV1 | [80] |

| Oxaliplatin | 6 mg/kg i.p. 1 time | 3 weeks | Mice C57Bl6 | M | CBD | phytocannabinoid | 1.25 – 10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [84] |

| Oxaliplatin | 6 mg/kg i.p. 1 time | 3 weeks | Mice C57Bl6 | M | Δ9-THC | CB1/2 agonist | 10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [84] |

| Oxaliplatin | 6 mg/kg i.p. 1 time | 3 weeks | Mice C57Bl6 | M | CBD + Δ9-THC | phytocannabinoid + CB1/2 agonist | CBD 0.16 mg/kg i.p. and Δ9-THC 0.16 mg/kg ip | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [84] |

AM281, CB2 antagonist/inverse agonist; AM630, CB2 antagonist; ATF-3-ir, cyclic AMP-dependent transcription factor ATF-3; DAGLα, diacylglycerol lipase; F, female; i.p., intraperitoneal; i.pl., intraplantar; i.g., intragastric; M, male; NapePLD, N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamine phospholipase D; NT, not tested; p-NF; phosphorylated neurofilament; p-r, peripherally restricted; PrNMI, peripherally restricted cannabinoid 1 receptor agonist; SR141716, CB1 antagonist; SR144528, CB2 inverse agonist; WD, withdrawal.

6.2. Taxane Compounds

The preclinical evidence for cannabinoids’ antinociceptive effects in CIPN induced by taxane compounds are mounting (see Table 2 for specific details). CBD, a phytocannabinoid, has demonstrated antinociceptive effect in mechanical and cold allodynia induced by CIPN using paclitaxel [84, 96, 97]. This antinociceptive effect is blocked by administration of a 5-HT1A antagonist (WAY100635), but not by antagonists for CB1 or CB2 receptors [97]. CB2 specific agonists such as R,S-AM1241 and AM1714 [98], AM1710 [78, 90, 99], MDA7 [100, 101] and MDA19 [102] have also been found to alleviate mechanical and cold allodynia induced by paclitaxel. This antinociceptive effect is mediated by CB2 receptors [78, 90, 98–100], but not CB1 receptors [78, 90, 98, 99]. One study demonstrated that β-caryophyllene (CB2 dietary agonist), a terpene found in black pepper and cannabis, alleviates mechanical allodynia and plantar heat hyperalgesia through a CB2 mechanism of action [103]. Mixed agonists (Δ9-THC, CP55,940 and WIN55,212–2) reverse mechanical and cold allodynia and plantar heat hyperalgesia [35, 77–79, 84, 99]. The antinociceptive effects of the mixed agonists CP55,940 [77] and WIN55,212–2 [78, 79] in the paclitaxel model were found to be mediated by CB1, but not CB2 receptors. The combination of Δ9-THC with CBD was shown to alleviate mechanical allodynia and the additive or synergistic effects of these two compounds may be mediated through separate molecular targets or changes in pharmacokinetics with co-administration [84, 107]. Indeed, it was suggested that CBD may enhance Δ9-THC mediated antinociceptive and hypolocomotor effects through inhibition of Δ9-THC metabolism [107]. However, more studies are necessary to determine the mechanisms involved in any additive or synergistic effects with coadministration. Moreover, MGL (JZL184 and 10) inhibitors reversed paclitaxel-induced mechanical allodynia through both CB1 and CB2 receptors mechanisms of action [104].

Table 2:

Preclinical cannabinoid studies in taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy

| Taxane | Dosage days | Exp. time | Species | Sex | Drugs | Pharm Specificity | Dose | Antinociception | Pain | Mediated by: | Tetrad | Dosage | Markers | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemo agent | Mice or Rat | M/F | Route | Test | CB1 | CB2 | or WD | Endo | Inflammation/others | ||||||

| Paclitaxel | 1 to 8 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 29 days | Mice C57Bl6 | M and F | CBD | phytocannabinoid | 5 – 10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and Acetone | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [96] |

| Paclitaxel | 8 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 10 weeks | Mice C57Bl6 | F | CBD | phytocannabinoid | 2.5 – 10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | No SR1471716A (3 mg/kg i.p.) | No SR144528 (3 mg/kg i.p.) Yes Way100635 (1 mg/kg i.p.) | NT | NT | NT | [97] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 3 weeks | Mice C57Bl6 | M | CBD | phytocannabinoid | 0.625 – 20 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [84] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 3 weeks | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | R,S-AM1241 | CB2 agonist | 1 – 10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | No SR141716A (10 mg/kg i.p.) | Yes SR144528 (10 mg/kg i.p.) | NT | NT | NT | [98] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 21 days | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | AM1714 | CB2 agonist | 1 – 10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | No SR141716A (10 mg/kg i.p.) | Yes SR144528 (10 mg/kg i.p.) | NT | NT | NT | [98] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 4 weeks | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | AM1710 | CB2 agonist | 0.1 to 5 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and Acetone | No AM251 (3 mg/kg i.p.) | Yes AM630 (3 mg/kg i.p.) | NT | NT | NT | [90] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 51 days | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | AM1710 | CB2 agonist | 0.032 – 3.2 mg/kg s.c. | Yes | Von Frey and Acetone | No AM251 (3 mg/kg s.c.) and CB1 expression | Yes AM630 (3 mg/kg s.c.) and CB2 expression | NT | NT | CD11b GFAP | [78] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 15 days | Mice C57Bl6 CB1 KO CB2 KO | M + F | AM1710 | CB2 agonist | 5 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and Acetone | No CB1 KO | Yes CB2 KO and AM630 (5 mg/kg i.p. or 5 μg i.t.) | Yes | NT | MCP1 IL-1β IL-6 TNFα | [99] |

| Paclitaxel | 1 mg/kg i.p. for 4 consecutive days | 15 days | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | MDA7 | CB2 agonist | 15 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | CB2 expression | NT | NT | Iba-1; IL-6 IL-10; BDNF pNFκBp65 CaMKIIα; p-CREB; ΔFosB IRF8 | [101] |

| Paclitaxel | 1 mg/kg i.p. for 4 consecutive days | 28 days | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | MDA7 | CB2 agonist | 15 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | Yes AM630 (5 mg/kg i.p.) and CB2 KO | NT | NT | IL-1β; TNFα LPS; CD11b GFAP; pERK IκBα; TLR2 TLR4 | [100] |

| Paclitaxel | 1 mg/kg i.p. for 4 consecutive days | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | MDA19 | CB2 agonist | 5–15 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [102] | |

| Paclitaxel | 1 mg/kg i.p. for 4 consecutive days | Mice CB2 WT CB2 KO | M | MDA19 | CB2 agonist | 10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | Yes CB2 KO | NT | NT | NT | [102] | |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 31 days | Mice swiss | M | Β-carophyllene | CB2 dietary agonist | 12.5 – 25 mg/kg p.o. | Yes | Von Frey and Plantar heat | No AM251 (1 mg/kg i.p.) | Yes AM630 (3 mg/kg i.p.);CB2 expression | NT | NT | IL-1β; MCP-1 Iba-1 pNFκBp65 p-p38 | [103] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 15 days | Mice C57Bl6 | M + F | Δ9-THC | CB1/2 agonist | 5 or 10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and Acetone | NT | NT | Yes | NT | No | [99] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 3 weeks | Mice C57Bl6 | M | Δ9-THC | CB1/2 agonist | 0.625– 20 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [84] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 15 days | Mice C57Bl6 CB1 KO CB2 KO | M + F | CP55,940 | CB1/2 agonist | 0.3 (low) to 10 (high) mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and Acetone | Yes CB1 KO (low dose) | No CB2 KO (low); Yes (high) confirmed by AM630 (5 mg/kg i.p.) | Yes | NT | No | [77] |

| Paclitaxel | 1 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 4 weeks | Rat Wistar | M | WIN55,212–2 | CB1/2 agonist | 1 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey and Plantar heat | NT | NT | NT | NT | IL-1β IL-6 TNFα iNOS CD11b MHC-II GFAP | [35] |

| Paclitaxel | 1 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 22 days | Rat Wistar | M | WIN55,212–2 | CB1/2 agonist | 1 – 2.5 mg/kg i.p. and 50 to 250 μg i.pl. | Yes | Von Frey and Plantar heat | Yes SR141716 (1 mg/kg i.p.) | NT | Yes | NT | NT | [79] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 51 days | Rat S-D | M | WIN55,212–2 | CB1/2 agonist | 0.1 – 1 mg/kg s.c. | Yes | Von Frey and Acetone | Yes AM251 (3 mg/kg s.c.) VF only | No AM630 (3 mg/kg s.c.) for VF and Acetone | NT | NT | CD11b GFAP | [78] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 3 weeks | Mice C57Bl6 | M | CBD + Δ9-THC | phytocannabinoid + CB1/2 agonist | CBD + Δ9-THC 1:1) 0.08 –40 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [84] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 9 weeks | Mice C57Bl6 CB1 KO CB2 KO | M | JZL184 | MGL inhibitor | 4 – 40 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | Yes SR141716 (3 mg/kg i.p.) and CB1 KO | Yes SR144528 (3 mg/kg i.p.) and CB1 KO | NT | AEA 2-AG | MCP-1 p-p38MAPK | [104] |

| Paclitaxel | 2 mg/kg i.p. 4 times every 2 days | 9 weeks | Mice CB1 KO CB2 KO | M | MJN110 | MGL inhibitor | 0.3 – 5 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | Yes SR141716 (3 mg/kg i.p.) and CB1 KO | Yes SR144528 (3mg/kg i.p.) and CB1 KO | NT | NT | MCP-1 p-p38MAPK | [104] |

i.t., intrathecal; F, female; M, male; NT, not tested; p.o., per os; WD, withdrawal.

6.3. Vinca Alkaloid Compounds

While vinca alkaloid induced CIPN has the least amount of preclinical studies using cannabinoid-based intervention, the results from the few studies are encouraging (see Table 3 for details). Phytocannabinoids, such as cannabidiol (CBD) and Δ9-THC, have been used to alleviate vincristine-induced CIPN [84]. This study evaluated the combination of CBD and Δ9-THC at lower doses in the alleviation of CIPN by vincristine, which may be useful in reducing the psychoactive effect associated with Δ9-THC. Moreover, the CB2 agonist AM1241 has been used to alleviate vincristine CIPN [105] and the reduction in mechanical pain sensitivity was demonstrated to be CB2, but not CB1 receptor mediated [105]. The synthetic mixed agonist WIN55,212–2 has also been given to reverse mechanical allodynia from CIPN induced by vincristine, an effect mediated by both CB1 and CB2 receptors [105]. Finally, inhibition of FAAH by ST4070 has been shown to reverse mechanical allodynia induced by vincristine [106](Table 3).

Table 3.

Preclinical studies in vinca alkaloid-induced peripheral neuropathy

| Vinca alkaloid chemo agent | Dosage days | Exp. time | Species: mice or rat | Sex: M/F | Drugs | Pharm. specificity | Dose and route | Antinociception | Pain: test | Mediated by: | Tetrad or WD | Dosage: Endo. | Markers: inflammation/others | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB1 | CB2 | ||||||||||||||

| Vincristine | 0.1 mg/kg i.p. 1 and 7 on | 3 weeks | Mice, C57Bl6 | M | CBD | Phytocannabinoid | 1.25–10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [84] |

| Vincristine | 0.1 mg/kg i.p. 5 on, 2 off, 5 on | 12 days | Rat, Sprague-Dawley | M | AM1241 | CB2 agonist | 2.5 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | No, SR141716 2.5 mg/kg i.p. | Yes, SR144528 2.5 mg/kg | NT | NT | NT | [105] |

| Vincristine | 0.1 mg/kg i.p. 5 on, 2 off, 5 on | 12 days | Rat, Sprague-Dawley | M | WIN55,212-2 | CB1/2 agonist | 0.75–2.5 mg/kg i.p. and 10–30 μg (i.t.) and 30–150 μg i.pl. | Yes | Von Frey | Yes, SR141716 2.5 mg/kg i.p. and 30 μg i.t. | Yes, SR144528 2.5 mg/kg i.p. and 30 μg i.t. | Yes | NT | NT | [105] |

| Vincristine | 0.1 mg/kg i.p. 5 on, 2 off, 5 on | 12 days | Rat, Sprague-Dawley | M | WIN55,212-3 | CB1/2 agonist inactive | 2.5 mg/kg i.p. and 10 μg (i.t.) | No | Von Frey | NA | NA | NT | NT | NT | [105] |

| Vincristine | 0.1 mg/kg i.p. 1 and 7 on | 3 weeks | Mice, C57Bl6 | M | Δ9- THC | CB1/2 agonist | 10 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [84] |

| Vincristine | 0.1 mg/kg i.p. 1 and 7 on | 3 weeks | Mice, C57Bl6 | M | Δ9- THC + CBD | CB1/2 agonist + phytocannabinoid | CBD 0.16 mg/kg i.p. and Δ9-THC 0.16 mg/kg i.p. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [84] |

| Vincristine | 0.15 mg/kg i.p.3x/week for 2 weeks | 2 weeks | Rat Sprague-Dawley | M | ST4070 | FAAH inhibitor | 50 mg/kg p.o. | Yes | Von Frey | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | [106] |

CB1 cannabinoid receptor 1, CB2 cannabinoid receptor 2, CBD cannabidiol, Endo. endocannabinoid, Exp. experiment, F female, FAAH fatty-acid amide hydrolase, i.p. intraperitoneal, i.pl. intraplantar, i.t. intrathecal, M male, NT not tested, p.o. per os, Pharm. pharmacological, ST4070 reversible FAAH inhibitor, WD withdrawal, Δ9-THC delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol

7. Cannabinoids in clinical chronic neuropathic pain studies

Both a recent meta-analysis [20] and a National Academy of Sciences recommendation from a committee of cannabinoid experts [25] have found substantial evidence from clinical trials that cannabinoid-based medicines are effective for the treatment of chronic pain. These findings are based on a growing number of clinical studies and trials that have investigated the efficacy of cannabinoids. Despite evidence supporting the beneficial effect of cannabinoids in treating neuropathic pain in general, it is important to point out that only one pilot study has examined the effect of cannabinoids in the treatment of chemotherapy-evoked neuropathic pain (see Table 4). This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical pilot study did not find a benefit of nabiximols, a cannabis extract with a 1:1 ratio of Δ9-THC to CBD, in the treatment of chronic chemotherapy pain [113]. However, this study was conducted using a small number of patients and, in consequence, prevented the power analysis to reach significance. Based on the limitations of this pilot study and the relative lack of clinical data, additional larger-scale randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials on the effects of cannabinoids in chronic chemotherapy are warranted.

Table 4:

Clinical cannabinoid studies in chronic pain of mixed etiology

| Chronic pain conditions | Pain test before tx | Type of study | Study design | Time study | Drugs | Dose per day | Route | Patients (#) | Gender M/F | Ethnicity | Age | Reduction pain intensity | Pain test after tx | Side effects | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropathic pain mixed etiology | VAS >30/100 | randomized double-blind placebo control | parallel | 3 sessions of 6 hours; session interval 3 to 21 days | Δ9-THC or placebo | 19.25 mg low dose 34.3 mg high dose | inhale using cigarette | 38 | 20/18 | 33 C 1 AA 1 H 3 O | 46 (range 21–71) | Yes 30 % | VAS | Euphoria Mood changes Decline cognition | [112] |

| Neuropathic pain mixed etiology | VAS >40/100 | randomized double-blind | 4 period crossover Latin square | 5 days (9 days washout) | Δ9-THC or placebo | 1.875 to 7.05 mg of THC | gelatin capsules inhaled by pipe | 23 | 11/12 | NR | 45.4 (±12.3) | Yes | NRS Daily | headachedry eye dizziness numbness cough burning sensation pain area | [126] |

| Central and peripheral neuropathic pain mixed etiololy | NPS 40/100 | randomized placebo-controlled | crossover | 2 sessions; session interval 4 hours | Δ9-THC or placebo | 45.9 mg low dose 56.3 mg high dosee | vaporizeusing foltin puff | 42 | 29/13 | 26 C7 H5AA 2 A 2 O | 46.4 (±13.6) | Yes 30 % | NPS | hypotension | [125] |

| Central and peripheral neuropathic pain mixed etiololy | VAS >30/100 | randomizeddouble-blind placebo-controlled | crossover | 3 sessions of 6 hours; session interval 3 to 14 days | Δ9-THC or placebo | 10.32 mg low dose 28 mg high dose | vaporized using volcano system | 39 | 28/11 | 28 C 5 AA 3 H 3 O | 50 (±11) | Yes 30 % | VAS | Euphoria Sedation Confusion Nausea Hunger | [127] |

| Central neuropathic pain MS associated | NRS | randomized double-blind placebo-controlled | parallel | 4 weeks | Δ9-THC formulationECP002A | 9 mg to 29 mg of Δ9-THC | oral | 24 | 8/16 | NR | 54.3 (±8.9) | Yes after tx No daily diary | NRS VAS McGill QP | headache dizziness fatigue euphoric mood | [122] |

| HIV-DSPN | VAS 30/100 | randomized double-blind | Parallel | 12 days | Δ9-THC or placebo | 96 mg Δ9-THC 3sessions X 32 mg Δ9-THC per session | inhale using cigarette | 55 | 22/5 Exp 26/2 Control | NR | 50 (±6) | Yes ≥ 30 % | VAS Daily | NR | [128] |

| HIV-DSPN | DDS >5/20 | randomized double-blind | Crossover | 5 days (no washout) | Δ9-THC or placebo | Titrating dose up and down 96 mg THC 4 sessions X 24 mg Δ9-THC per session | inhale using cigarette | 34 | 33/1 | NR | 49.1 (±6.9) | Yes | DDS | NR | [129] |

| Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy | NRS ≥ 4/10 | randomized placebo-controlled | Crossover | 4 weeks (2 weeks washout) | Nabiximols Sativex THC:CBD | 8.1 to 32.4 mg of Δ9-THC 7.5 to 30 mg of CBD | oromucosal spray | 18 | 3/15 | NR | 56 (±10.8) | No | NRS Daily | dizziness fatigue dry mouth nausea diarrhea | [113] |

| Peripheral neuropathy | NRS ≥ 3/10 | randomized double-blind placebo-controlled | parallel | 15 weeks | Nabiximols Sativex THC:CBD | 21.6 to 64.8 mg of Δ9-THC 10 to 60 mg of CBD | oromucosal spray | 246 | 96/150 | 243 C 2 AA | 57.3 (±14.2) | No | NRS BPI-SF DAT | headache dizziness dry mouth nausea diarrhea | [114] |

| Neuropathic pain peripheral origin | NRS 7/10 | randomized double-blind placebo control | parallel | 5 weeks | Nabiximols Sativex THC:CBD | 3.51 to 84.78 mg of Δ9-THC 3.25 to 78.5 mg of CBD | oromucosal spray | 125 | 51/74 | 121 C 4 O | 52.4 (±15.8) | Yes ≥ 30 % | VAS NRS NPS PDI | Dizziness fatigue dry mouth nausea | [115] |

| Central neuropathic pain MS associated | NRS | randomized double-blind placebo-controlled | parallel | 5 weeks | Nabiximols Sativex THC:CBD | 21.6 to 129.6 mg of Δ9-THC 20 to 120 mg of CBD | oromucosal spray | 64 | 14/49 | NR | 49 (±8.4) | Yes | NRS daily | dizziness headache dry mouth nausea diarrhea | [118] |

| Central neuropathic pain MS associated | NRS ≥ 4/10 | randomized double-blind placebo-controlled | parallel | 14 weeks | Nabiximols Sativex THC:CBD | 23.76 to 32.4 mg of Δ9-THC 22 to 30 mg of CBD | oromucosal spray | 339 | 109/230 | 332 C 4 AA 2 A | 48.97 (±10.47) | No | NRS | dizziness fatigue dry mouth nausea diarrhea | [121] |

| HIV-DSPN and neuropathic pain mixed etiology | VAS >30/100 | randomized double-blind placebo-controlled | crossover | 2 weeks (washout) | Nabiximols Sativex THC:CBD | 2.5 to 120 mg of Δ9-THC 2.5 to 120 mg of CBD | oromucosal spray | 20 | 10/10 | NR | 48 | Yes > 50 % | VAS | headache hypotension intoxication diarrhea | [116] |

| Spinal cord injury | NPS >5/10 | randomized double-blind | crossover | Dronabinol or control (diphenhydramine) | 5 mg to 20 mg/day | capsules p.o. | 7 | 5/2 | 6 C 1 AA | 50.1 (±8.3) | No | NRS | drowsiness fatigue dry mouth constipation | [124] | |

| Central neuropathic pain MS associated | NRS ≥ 3/10 | randomized double-blind placebo-controlled | crossover | 6 weeks (washout) | Dronabinol | 2.5 to 10 mg | oral | 24 | 10/14 | NR | 50 (23 to 55) | Yes | NRS | dizziness tiredness myalgia dry mouth nausea | [119] |

| Central neuropathic pain MS associated | NRS ≥ 4/10 | randomized double-blind Placebo-controlled | parallel | 16 weeks | Dronabinol | 7.5 to 15.0 mg | oral | 240 | 65/175 | NR | 47.7 (±9.7) | No | NRS | headache dizziness fatigue vertigo dry mouth nausea diarrhea | [123] |

| Neuropathic pain mixed etiology | VAS 70/100 | randomized double-blind | crossover | 14 weeks (2 weeks washout) | Nabilone or Dihydrocodeine | Nabilone 2 mg | p.o. | 96 | 46/50 | NR | 50.15 (±13.69) | Yes | VAS | tiredness tingling headache | [117] |

| HIV-DSPN | VAS >70/100 | randomized double-blind placebo-controlled | parallel | 9 weeks (4 weeks for titration) | Nabilone | 2 mg | oral | 15 | 2/13 | NR | 45.5 (±10.84) | Yes | VAS | dizziness drowsiness | [120] |

| Neuropathic pain mixed etiology | VAS | randomized double-blind placebo-controlled | crossover | 5 weeks | 1’,1’Dimethyl-Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol-11oic acid (CT-3) | 40 mg (10 mg per capsules) | oral | 21 | 13/8 | NR | 50.86 (±11.69) | Yes | VAS | tiredness dry mouth | [53] |

AA, African-American; A, asian; BPI-SF, brief pain inventory short form; C, caucasian; DAT, dynamic allodynia test; DDS, descriptor differential scale; H, hispanic; HIV-DSPN, human immunodeficiency virus distal sensory peripheral neuropathy; F, female; M, male; McGill QP, McGill pain questionnaire; Mixed etiology, include but are not exclusive to complexe regional pain syndrome 1 (CRPS-1) and II (CRPS-II), spinal cord injury, diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, radiculopathy, focal nerve lesion and others ;NPS, neuropathic pain scale; NR, not reported; NRS, numerical rating scale; O, other; PDI, pain disability index; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Clinical studies assessing the analgesic effect of cannabinoids in chronic neuropathic pain of mixed etiology have slowly emerged in the last twenty years as summarized in four recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews [108–111]. More specifically, it has been demonstrated that Δ9-THC significantly alleviated neuropathic pain of mixed etiology relative to placebo control group (see Table 4 for specific details)[112, 125–127]. Δ9-THC has also been shown to have analgesic properties in patients suffering from neuropathic pain associated with multiple sclerosis (MS) [122]. Distal sensory peripheral neuropathy (DSPN) found in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients has been found to be alleviated by Δ9-THC patients relative to placebo control [128, 129]. There are three clinical trials that found nabiximols (Sativex, a 1:1 THC:CBD) to be effective in patients with neuropathic pain of peripheral origin [115], central neuropathic pain mainly spasticity associated with MS [118] and HIV-DSPN [116]. Conversely, three studies found that nabiximols did not generate a positive analgesic response in patients with chemotherapy-induced neuropathy [113], peripheral neuropathy [114] and central neuropathy associated with MS [121]. The difference in the clinical outcome of these studies could be attributed to different factors such as sample size of patients, different types of chronic pain, difference in the duration of the chronic pain for patients recruited, origin of symptoms, past medications used to alleviate pain and individual responses to medications and treatments. Of the two clinical trial evaluating the analgesic properties of dronabinol in patients with central neuropathic pain associated with MS, one had positive findings [119] in contrast to negative findings observed with the other study [123]. The number of patients evaluated in the latter study was much higher relative to the study with positive results (Table 4). Another study also found negative results for dronabinol used in patients with chronic pain associated with spinal cord injury [124]. Nabilone has been shown to alleviate pain in neuropathic pain patients of mixed etiology [117] and also in patients with HIV-DSPN [120]. One study found that 1’,1’Dimethylheptyl-Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol-11-oic acid (CT-3) [53] reduced pain intensity in neuropathic pain patients of mixed etiology. The clinical evidence and benefits of cannabinoids for the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain of diverse etiology are mounting but are still weak and at an infancy state. Additional clinical trials are necessary to address the knowledge gap between the preclinical and clinical findings in order to improve our understanding of the role and impact of the cannabinoid system in alleviating pain in patients suffering from chronic pain of mixed etiology.

8. Placebo and nocebo effects in cannabinoid clinical studies

The contribution of the placebo effect is an important consideration when evaluating the antinociceptive effects of cannabinoids both in clinical trials, as well as anecdotal reports. A placebo response, an effect that is not the direct result of the pharmacological actions of the drug itself, may occur as the result of an individual’s psychology (expectations, priming and others) or physiology (genetic variations, and others), and is mediated in part through the endocannabinoid system and changes in brain connectivity [130–133]. The extent to which these individual differences contribute to cannabinoid-mediated analgesia are still being uncovered. Moreover, due to the relatively small amount of clinical trial data evaluating cannabinoids in pain, unsubstantiated claims towards cannabis efficacy have gone unchecked. The recent explosion in popularity and availability of cannabis along with the often ill-informed perception in the general public that natural products are safer than pharmaceutical equivalents may likely contribute towards the perception that cannabis is a panacea for all physiological and psychological ailments, including pain [132, 133]. Preconceptions concerning cannabis by the user, the user’s community and health care provider may positively (placebo) or negatively (nocebo) affect responses in the individual [132]. While surveys and anecdotal reports by cannabis users generally regard cannabis as effective, only a small number of double-blind, placebo controlled clinical studies exist, primarily as a treatment for pain conditions (see Table 4). Clinical studies have used either NIDA provided cannabis cigarettes or nabiximols, a cannabis tincture [132]. Studies with nabiximols, a 1:1 THC:CBD peppermint flavored cannabis tincture, use an inert peppermint flavored tincture as the placebo control, while studies using NIDA provided smoked cannabis use placebo cigarettes containing cannabis with the cannabinoids removed via an ethanol extraction [132, 133]. The analgesic efficacy of cannabis in these clinical studies has largely found to be a modest, but statistically significant improvement over placebo in symptoms (see table 4). What is unclear in studies using smoked cannabis, is to what extent the participants’ prior knowledge, opinions, and exposure to cannabis contribute to the placebo or nocebo response. Do cannabis naïve or non-naïve participants experience greater placebo or nocebo effects with placebo cannabis? Answering these types of questions in future studies will contribute to a more nuanced understanding of both the types of conditions, and types of individuals cannabis based medications are best indicated for.

9. Potential Mechanisms of Action and Interaction of Cannabinoids in Pain

As mentioned in the introduction, the endocannabinoid system is a broadly active neuromodulatory system, and exploration of the entirety of its mechanisms is beyond the scope of this review. In the following section, we provide a brief, but far from exhaustive, review of the potential sites by which the antinociceptive effects of compounds targeting the endocannabinoid system are mediated.

9.1. Cation Channels

Cannabinoids can modulate ion channel activity via CB1 receptor activation. CB1 receptor activation results in inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and decreases in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [58](Fig. 5). This leads to a decreased activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) which can phosphorylate, and inactivate voltage gated potassium channels [58]. Application of 1 μM of the synthetic cannabinoids WIN55,212–2 and CP55,940 was found to increase voltage-gated potassium channel currents in rat hippocampal neurons via modulation of cAMP [134]. By decreasing cAMP concentrations, and thus protein kinase A (PKA) activity, the inhibitory potassium channels become more active and the cell is moved away from depolarization. This inhibitory effect may be beneficial in pain states in which there is hyperexcitability of neurons along the nociceptive pathway.

Cannabinoids may also modulate calcium functioning (Fig. 5). Calcium influx upon cell depolarization plays a key role in neurotransmitter release, mediated by N-, P-, and Q- type voltage-gated calcium channels. Inhibition of N- and P/Q voltage-gated calcium channels via CB1 receptor activation has been demonstrated at nanomolar concentrations of the synthetic mixed CB1/2 agonist R-(+)-WIN55,212–2 in rat hippocampal neurons [135]. Inhibition of T-type V3 calcium channels has been demonstrated with 1 μM Δ9-THC and CBD in rat inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve [136]. Alterations in voltage-gated calcium channel 3.2 isoforms have been implicated in various pain states, and the cannabinoid-mediated inhibition of these calcium channels may be efficacious in treating chronic and neuropathic pain [137].

9.2. Transient Receptor Potential Channels

Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) channels are non-selective cation channels that may be activated via various physical or chemical means (Fig. 5). Activation of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) is associated with the painful burning sensation associated with consumption of capsaicin containing chili peppers [138]. TRPV1 is also heat and pH sensitive, and is expressed along the pain pathway in peripheral nerves, dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia, and cortex [138, 139]. TRPV1 may be activated and then desensitized by agonists such as capsaicin, which is prescribed as a topical application for pain. The structural similarity of capsaicin and anandamide led to the discovery that anandamide also behaves as a low efficacy agonist at TRPV1 [61], and like capsaicin, is capable of producing agonist-induced desensitization of TRPV1 [140]. CBD, a plant cannabinoid, does not produce the psychoactive effect produced by Δ9-THC. CBD has also been demonstrated to be an agonist at TRPV1 [141] and prevents allodynia in nerve ligation models which is blocked by co-administration of a TRPV1, but not CB1 receptor antagonist [142]. Cannabinoid-mediated desensitization of TRPV1 may be efficacious in treating the heat hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia associated with neuropathic pain.

Transient Receptor Potential A1 (TRPA1) is commonly co-expressed with TRPV1 along the pain pathway and mediates similar sensations of pain, in addition to irritation and itch (Fig. 5). TRPA1 is activated by allyl isothiocyanate, an active component of mustard and wasabi, as well as Δ9-THC, CBD, cannabichromene (CBC) and CBG cannabigerol (CBG) at nanomolar concentrations in transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells and micromolar concentrations in rat DRG (dorsal root ganglion) [143]. TRPA1 function can be disrupted by oxaliplatin, resulting in cold allodynia. CBC or other cannabinoids may have utility in preventing this side effect. TRPM8 (transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 8) also mediates cold sensation, either by temperature or activation by menthol. Δ9-THC, CBD and CBG also were found to antagonize TRPM8 at low micromolar concentrations in transfected HEK (human embryonic kidney) cells and micromolar concentrations in rat DRG [143]. Antagonism of TRPM8 by cannabinoids may be efficacious in treating cold hyperalgesia.

9.3. Glycine

Glycine receptors are ligand-gated chloride ion channels mediating fast inhibitory neurotransmission in the CNS and are known mediators of pain states (Fig. 5). The activation occurs by glycine and other amino acids, with known modulators of glycine receptors including alcohol and cannabinoids. Anandamide, Δ9-THC and CBD have been demonstrated to be allosteric modulators of glycine receptors derived from rat ventral tegmental area and Xenopus oocytes and HEK cells transfected with human glycine receptors [144, 145]. The efficacy of cannabinoid-mediated analgesia has been positively correlated to α3 glycine receptor potentiation in rat dorsal horn neurons, and abolished in α3 knockout mice, but not with CB1 receptor antagonism or in CB1/CB2 knockout mice [146, 147].

9.4. GABA

CB1 receptors are expressed in high density on inhibitory GABAergic nerve terminals in the brain and spinal cord (Fig. 5). Activation of inhibitory CB1 receptors on inhibitory GABAergic nerve terminals thus results in net disinhibition of excitation of the descending pain inhibitory pathways [148]. In brief, in the descending pain pathway, the periaqueductal gray (PAG) modulates pain promoting “ON cells” and pain inhibiting “OFF cells” in the rostral ventral medulla (RVM). Cannabinoids and opioids are thought to switch on the pain inhibitory “OFF cells” of the RVM, which project to the spinal cord to excite inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal horn to produce analgesia. They will also inhibit the pain promoting “ON cells” of the RVM which may inhibit “OFF cells” or disinhibit ascending pain pathways [148].

9.5. Glutamate

Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS (central nervous system) and plays a central role in the transmission, processing, and modulation of pain signaling (Fig. 5). Moreover, both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors have been demonstrated to be involved in cannabinoid-induced analgesia. Intra-PAG injections of WIN55,212–2 produced analgesia to nociceptive thermal stimuli in rats, and this effect was blocked by pre-treatment with a CB1 receptor antagonist, and metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) 2, 3 and 5 antagonists, as well as an N-methyl D-Aspartate (NDMA) antagonist [149]. The involvement of mGluR5 in the effect of WIN55,212–2 analgesia is further supported by findings that confirm the analgesic effect of intra-PAG injection of WIN55,212–2 in the formalin pain model. This effect is marked by decreased “ON cell” firing and increased “OFF cell” firing in the RVM, and is blocked by pretreatment with a mGluR5 antagonist [150]. Furthermore, alterations in CB1 and mGluR5 are seen in rats subjected to nerve constriction neuropathic pain model [151].

The analgesic effect of WIN55,212–2 in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) is also mediated by metabotropic and NMDA glutamate receptors. The administration of the NMDA antagonist (AP5) into the nucleus accumbens (NAc) prior to intra-BLA administration of WIN55,212–2 abolished analgesia in the tail flick test in rats [152]. Additionally, the interactions between mGluR5 and CB1 receptors on projections from the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) to the central amygdala (CEA) are altered in an arthritis pain model in rats, and co-activation of the two receptors was required for analgesia [153, 154].

9.6. Serotonin

Cannabinoid-serotonin interactions may be an important target for both the sensory aspect of pain, as well as the affective component of pain that can accompany the chronic pain often linked to physical, emotional, and financial burden associated with major medical intervention such as cancer treatment. There is evidence for both indirect modulation of serotonergic tone via CB1 receptors, in addition to direct modulation of cannabinoids at serotonin receptors (Fig. 5). Systemic administration of cannabinoid agonists ACEA (CB1 receptor) and WIN55,212–2 (mixed CB1/2 receptors) produced antinociception to thermal stimulation in mice, and this effect was blocked by spinal depletion of serotonin by 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine (5,7-DHT), as well as by administration of the 5-HT2A antagonist ketanserin, the 5-HT7 antagonist SB-269970 and the 5-HT2A/5-HT7 antagonist risperidone [155]. Additionally, micro-injections of WIN55,212–2 in the RVM and Dorsal Raphe Nucleus (DRN) produce antinociception, decreased “ON cell” and increased “OFF cell” firing in the RVM, and increased activity of 5-HT containing neurons of the DRN [156, 157]. CBD was found to reduce paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain through a 5-HT1A mechanism that was not blocked by a CB1 receptor antagonist suggesting a more direct interaction [97]. Additionally, 5-HT3A currents are shown to be modulated by Δ9-THC in transfected HEK cells and rat neurons isolated from the inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve [158]. Taken together, cannabinoid-serotonin interactions may underlie many of the medicinal effects of cannabinoids, including antinociception.

9.7. Anti-inflammatory & Immunomodulatory Actions

Cannabinoid receptors are expressed throughout the central and peripheral nervous system white matter and in immune cells [56, 159] (Fig. 5). These key sites of action play an important role in the alleviation of chronic, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain. Indeed, the up-regulation of endocannabinoids has been demonstrated in patients with multiple sclerosis [160] along with increases in CB1 and CB2 mRNA that correlate with an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) [161]. Δ9-THC and CBD have been demonstrated to decrease production of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine release in vitro [162]. AEA promotes increases in anti-inflammatory IL-10 and decreases pro-inflammatory nitric oxide release, and upregulation in pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNA following LPS stimulation of rat primary microglia [163]. Aberrant T cell migration and accumulation can occur in inflammatory pain conditions, and targeting T cells with cannabinoid compounds are suggested to be a potent regulator of immune pathway-driven inflammatory pain [164]. Of particular clinical relevance, CB2 agonists were shown to inhibit T cell proliferation [164] and migration [165, 166], and induce apoptosis [167].

CB2 selective receptor agonists eschew the psychotropic effects associated with CB1 receptor agonism, and are an emerging pharmacological prospect for targeting maladaptive T cell processes which underlie many disorders.

9.8. Cannabinoid-Chemotherapeutic CYP450 Pharmacokinetic Interactions

Pharmacokinetic interactions are critical parameters to account for when considering treatment options for side effects associated with chemotherapy regimens. While cisplatin is excreted unchanged, paclitaxel is metabolized through CYP450 2C8 (major) and 3A4/3A5 (minor) [168, 169], docetaxel through 3A4 [170] and vincristine through 3A5 (major) and 3A4 (minor) enzymes [171]. While the interaction of Δ9-THC with CYP enzymes is likely too weak to be clinically relevant [172], the high dose tolerability of CBD could be a clinical concern; doses as high as 600 mg have been evaluated for anxiolytic efficacy [173]. Of relevance to the chemotherapeutics in question, CBD can inhibit CYP450 3A4 and 3A5 with Ki values of 1 μM and 0.195 μM, respectively [174]. It has been noted that this is a physiologically relevant concentration, as 20 mg of smoked CBD was previously reported to produce a blood concentration of 114 ng/mL or 0.363 μM [175]. CBD was recently approved under the brand name Epidiolex, as a sublingual extract for the treatment of epileptic syndromes. Hemp-derived CBD isolates and products containing CBD [176] have also flooded the nutraceutical gray market in the past few years, where customers may consume CBD without consulting their licensed medical practitioner first, and be unaware of potentially dangerous interactions with medications they are currently taking. While cannabinoids show promise for treatment of a wide variety of ailments, caution should be advised before more research becomes available.

9.9. Cannabinoid-opioid interactions

Cannabinoid CB1 and opioid receptors are both associated with analgesia, and both share many characteristics including inhibitory G protein coupling and presynaptic expression that underlie a neuro-modulatory role as inhibitors of neurotransmitter release (Fig. 5). Whether co-expression of cannabinoid and opioid receptors are required for the analgesic effects of either class of compounds appears to vary based by ligand, dose, and receptor profile, as well as type of pain. Studies using receptor knockout mice found that opioid receptors (mu, delta and kappa) were not required for Δ9-THC antinociception in the tail flick test [177], nor were CB1 receptors necessary for morphine antinociception in chemical, mechanical, or thermal pain [178]. Conversely, studies using antagonists in normal mice have found blockade of cannabinoid-induced antinociception in the tail flick test using the kappa opioid antagonist nor-BNI [179]. The CB1 receptor antagonist, AM251, blocked mu-opioid mediated analgesia in the tail flick test [180] and blocked mechanical hyperalgesia induced by intraplantar prostaglandin E2 injection [181]. Moreover, the antinociceptive effects of the CB2 specific agonist AM1241 were absent in mu opioid knockout mice, and inhibited by intraplantar administration of naloxone or anti-serum to β-endorphin [182]. It was hypothesized that AM1241 produces analgesia through a CB2-mediated release of β-endorphin from cutaneous keratinocytes. Another study supports the role of opioid receptor involvement in AM1241 antinociception, but that this is not a universal mechanism of CB2 mediated antinociception as naloxone blocked the effects of AM1241, but not of JWH133, another CB2 selective compound [183]. Therefore, the use of cannabinoid medications either as a replacement therapy or an opioid-sparing adjuvant therapy are intriguing possibilities. Notably, a retrospective time-series analysis of state death certificate data from 1990–2000 found that opioid overdose deaths were 24.8% lower in states with medical cannabis laws compared to states without legalized medical cannabinoids [184]. The possible use of cannabinoid medications either as a replacement therapy or an opioid-sparing adjuvant therapy are an intriguing possibility. Clinical studies also suggest that cannabinoid compounds could be used in combination with opioids and, therefore, reduce opioid doses leading to lower side effects [185, 186]. In addition, several studies suggest that either oral Δ9-THC [187] or smoked cannabis [185] can elicit additive beneficial effects on chronic non-cancer pain when used in combination with either morphine or oxycodone.

10. Conclusion

While the clinical evidence for cannabinoid-based therapies is still in its infancy, a growing number of preclinical studies support the development of cannabinoid-based medications for treatment of chemotherapeutic agent inducing neuropathic pain, among other conditions. Of important clinical consideration, while some cannabinoid compounds may be psychoactive, this is not a requisite for this class of compounds, and may not be necessary for their beneficial effects. Indeed, CB2 specific compounds, peripherally-restricted CB1 compounds, and phytocannabinoids such as CBD are also efficacious in various preclinical models, and avoid the psychoactive effect associated with centrally acting CB1 receptor agonists, such as Δ9-THC. There is a great need for novel, highly effective therapeutic agents, for chronic pain and otherwise, and the endocannabinoid system is proving to be one of the most promising systems to probe for novel treatments for a variety of conditions. The broad neuro-modulatory role of cannabinoids, and diverse library of both natural and synthetic compounds offer a wealth of possible future treatments for various conditions, and many exciting avenues of preclinical and clinical research for years to come.

Key points.

Three classes of chemotherapeutic agents: associated cancer and side effects

Beneficial effects of cannabinoid compounds in preclinical and clinical studies

Mechanisms of action of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to my beloved mother, Manon Marcotte, who passed away from lymphoma on January 3rd 2011 (JG) and all the people who have lost their battles against cancer and to all of those who are still fighting this dreadful disease. Special acknowledgement to Terri Lloyd who is currently fighting triple negative breast cancer and is an Admissions Director for the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center.

Funding: This work has been supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse DA044999–01A1 (DJM and JG), Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine Grant 121035 (JG), the CH Foundation (MN) and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas RP140008 (KP).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest: The authors Henry L Blanton, Jennifer Brelsfoard, Nathan DeTurk, Kevin Pruitt, Madhusudhanan Narasimhan, Daniel J Morgan and Josée Guindon declared that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grisold W, Cavaletti G, Windeback AJ. Peripheral neuropathies from chemotherapeutics and targets agents: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staff NP, Grisold A, Grisold W, Windebank AJ. Chemoterapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a current review. Ann Neurol 2017;81:772–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Windebank AJ, Grisold W. Chemoterapy-induced neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2008;13:27–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pike CT, Birnbaum HG, Muehlenbein CE, Pohl GM, Natale RB. Healthcare costs and workloss burden of patients with chemotherapy-associated peripheral neuropathy in breast, ovarian, head and neck, and nonsmall cell lung cancer. Chemother Res Pract. 2012;2012:913848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seretny M, Currie GL, Sena ES, Ramnarine S, Grant R, MacLeod MR et al. Incidence, prevalence, and predictors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2014;155:2461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaskin DJ, Richar P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain 2012;13:715–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nahin RL. 2015. Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. J Pain. 2015;16:769–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fallon MT. Neuropathic pain in cancer. Br J Anaesth 2013; 111:105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kannarkat G, Lasher EE, Schiff D. Neurologic complications of chemotherapy agents. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paice JA. Chronic treatment-related pain in cancer survivors. Pain 2011;152:S84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flatters SJL, Dougherty PM, Colvin LA. Clinical and preclinical perspectives on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN): a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:737–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim PY, Johnson CE. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a review of recent findings. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30:570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf S, Barton D, Kottschade L, Grothey A, Loprinzi C. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: prevention and treatment strategies. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44:1507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper TE, Chen J, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Carr DB, Aldington D, Cole P, Moore RA. Morphine for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017. May 22;5:CD011669. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011669.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fradkin M, Batash R, Elamleh S, Debi R, Schaffer P, Schaffer M et al. Management of peripheral neuropathy induced by chemotherapy. Curr Med Chem. 2019; doi: 10.2174/0929867326666190107163756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilron I, Bailey JM, Tu D, Holden RR, Weaver DF, Houlden RL, 2005. Morphine, gabapentin, or their combination for neuropathic pain. N Engl J Med 352;1324–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guindon J, Hohmann AG. The endocannabinoid system and pain. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2009;8:403–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rock EM, Parker LA . Cannabinoids as potential treatment for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whiting D. Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists: a heterogeneous class of novel psychoactive substance with emerging risk of psychosis. Evid Based Ment Health. 2015;18:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balneaves LG, Alraja A, Ziemianski D, McCuaig F, Ware M. A National Needs Assessment of Canadian Nurse Practitioners Regarding Cannabis for Therapeutic Purposes. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2018;3:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware MA, Wang T, Shapiro S, Collet JP. Cannabis for the Management of Pain: Assessment of Safety Study (COMPASS). J Pain 2015;16:1233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazekamp A, Ware MA, Muller-Vahl KR, Abrams D, Grotenhermen F. The medicinal use of cannabis and cannabinoids--an international cross-sectional survey on administration forms. J Psychoactive Drugs 2013;45:199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch ME, Ware MA. Cannabinoids for the Treatment of Chronic Non-Cancer Pain: An Updated Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015;10:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids. The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. 2017. nationalacademies.org DOI:10.17226/2462510.17226/24625https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK423845/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK423845/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, Lo EJ, Marcu A, Grant JR, Sajed T et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1074–D1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stover DG, Winer EP. Tailoring adjuvant chemotherapy regimens for patients with triple negative breast cancer. Breast. 2015;24:S132–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao H, He G, Yan S, Chen C, Song L, Rosol TJ et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: is there a treatment on the horizon? Oncotarget. 2017;8:1913–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:364–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jordan MA, Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:253–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Starobova H, Vetter I. Pathophysiology of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]