Abstract

Whole-chromosome fusions play a major role in the karyotypic evolution of reptiles. It has been suggested that certain chromosomes tend to fuse with sex chromosomes more frequently than others. However, the comparative genomic synteny data are too scarce to draw strong conclusions. We obtained and sequenced chromosome-specific DNA pools of Sceloporus malachiticus, an iguanian species which has experienced many chromosome fusions. We found that four of seven lineage-specific fusions involved sex chromosomes, and that certain syntenic blocks which constitute the sex chromosomes, such as the homologues of the Anolis carolinensis chromosomes 11 and 16, are repeatedly involved in sex chromosome formation in different squamate species. To test the hypothesis that the karyotypic shift could be associated with changes in recombination patterns, we performed a synaptonemal complex analysis in this species and in Sceloporus variabilis (2n = 34). It revealed that the sex chromosomes in S. malachiticus had two distal pseudoautosomal regions and a medial differentiated region. We found that multiple fusions little affected the recombination rate in S. malachiticus. Our data confirm more frequent involvement of certain chromosomes in sex chromosome formation, but do not reveal a connection between the gonosome–autosome fusions and the evolution of recombination rate.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Challenging the paradigm in sex chromosome evolution: empirical and theoretical insights with a focus on vertebrates (Part II)’.

Keywords: lizards, synaptonemal complexes, flow-sorted chromosome probes, FISH, next-generation sequencing

1. Introduction

Whole-chromosome fusions have played a major role in the karyotype evolution of vertebrates. The ancestral vertebrate karyotype is thought to be bimodal, i.e. with a clear distinction between normal-sized macrochromosomes and small ‘dot-like’ microchromosomes [1], since the microchromosomes of different lineages share high homology [2,3]. Bimodal karyotypes are a characteristic feature of some amphibians and fishes (mostly basal clades), birds and a majority of reptiles [4]. Unimodal karyotypes with chromosomes of gradually decreasing size are characteristic for many amphibians (derived clades), teleost fishes, mammals and some reptiles [5], and originate independently in different lineages by the fusion of microchromosomes with each other and with the macrochromosomes [6,7].

The fusions involving sex chromosomes are particularly interesting, because the translocated autosomal fragments become subjected to different evolutionary forces (e.g. sex linkage, heterozygosity, suppression of recombination, etc.) than before rearrangement, in contrast with autosome–autosome fusions. It has been suggested that certain chromosome pairs are more often involved in sex chromosome formation in vertebrate evolution than others, both by becoming sex chromosomes de novo and by fusing with already existing sex chromosomes [8,9]. According to the most widespread model of sex chromosome evolution, the translocations of loci with sexual antagonistic alleles on the sex chromosomes are positively selected, and such loci accumulate in the sex chromosomes [10,11]. Another model shows that such fusions could be favoured in cases of selection for heterozygosity, because the loci added to the sex chromosomes always remain present in the heterozygous state in the heterogametic sex [12]. Female meiotic drive is also suspected to be the driving force in the fixation of the sex chromosome–autosome fusion, which is supported by the higher incidence of the fusions in the XX/XY systems than in the ZZ/ZW systems [13]. There is also a population genetic model which implies that this observed pattern is best reconstructed if the fusions are deleterious and are fixed by drift, and the mutation rate is male-biased [14]. Thus, the predisposition of fusions between certain autosomes and sex chromosomes to become fixed may arise if sex linkage or high heterozygosity are particularly beneficial for certain loci, or if these fusions are the least deleterious. However, there are not many empirical data to support this hypothesis, since similar fusions may repeatedly occur in different lineages by coincidence.

To address the question of possible non-random involvement of certain linkage groups in fusions with sex chromosomes, it is important to compare syntenic maps of different species which have experienced sex chromosome–autosome fusions in the evolution of their karyotypes. It is known that in therian mammals and birds, the vertebrate groups with most extensively studied chromosomal diversity, such fusions are rare and the sex chromosomes are among the most conserved elements of the karyotype. In birds, this is because sex chromosome–autosome fusions are generally less frequent in ZZ/ZW systems than in XX/XY systems [14]. In mammals, conservation of the sex chromosomes is most likely caused by the mechanisms of dosage compensation: the inactivated X chromosome significantly alters gene expression in the translocated autosomal fragments, and thus makes the majority of such fusions deleterious [15,16]. Sex chromosome–autosome fusions are much more frequent in squamate reptiles [14]. The exact causes of this are unclear. It is possible that their fixation is facilitated by the absence of global dosage compensation at least in some reptile lineages [17], which makes such fusions less deleterious. It is notable that such fusions are absent in the green anole, the only reptile species with proven global dosage compensation [18,19]. However, the dosage compensation patterns are known only for a handful of reptile species, which makes any conclusions premature.

Among the reptile groups with frequent sex chromosome–autosome fusions, the pleurodont iguanians provide a good model for investigating the sex chromosome–autosome fusions. The ancestral XX/XY-type sex chromosomes of these lizards represent one of the most ancient vertebrate syntenic groups as they are homologous to a single chromosome pair in birds (the chicken chromosome 15 (GGA15)) [18,20,21]. They are preserved as a single chromosome pair in the ancestral karyotype of Iguania (2n = 36) [22]. Thus, all the fusions involving the sex chromosomes in pleurodonts occurred independently in each clade and after the initial sex chromosome differentiation [23]. Previously, we studied sex chromosome–autosome fusions in the anole (sub)genera Ctenonotus and Norops (Dactyloidae) [24,25]. Another interesting pleurodont group with a high incidence of sex chromosome–autosome fusion is the genus Sceloporus (Phrynosomatidae). It displays a higher chromosomal variability than most reptiles: thus 2n varies in this genus from 22 to 46. All these karyotypes can be derived from the ancestral phrynosomatid karyotype (2n = 34) via chromosomal fusions and fissions [26,27]. Both the sex chromosomes and autosomes are involved in fusions in the species with low diploid numbers [26,28].

In this study, we investigated the karyotype of Sceloporus malachiticus, the green spiny lizard, which represents the clade with 2n = 22, to identify the chromosome rearrangements which occurred in this lineage and to perform comparative analysis of the sex chromosome–autosome and autosome–autosome rearrangements. We obtained flow-sorted chromosome samples, which were analysed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and low coverage sequencing to determine their homology with the chromosomes of the green anole, Anolis carolinensis, a species which retains the ancestral karyotype of Iguania [22].

The dramatic karyotypic shift from 2n = 34 to 2n = 22 in S. malachiticus and related species is interesting in the context of the search for general patterns of karyotype and genome evolution in animals. It has been hypothesized that the possible biological significance of such multiple chromosome fusions could be the expansion of linkage groups under a selection for decreased recombination [1,29]. In this scenario, the sex chromosome–autosome fusions could become especially favourable, because sex chromosomes are characterized by decreased recombination rates. Besides the fact that parts of Y and W chromosomes do not recombine at all, X and Z chromosomes also have decreased recombination rates at the population level, because they recombine in only half the generations. It might be expected that in this case, other forces, such as changes in global crossover rates, would also act to decrease recombination in those species with multiple fusions. To check the hypothesis on the connection between chromosome fusion and the evolution of recombination patterns, we applied an immunocytological approach to detect meiotic crossing over in synaptonemal complex (SC) spreads of S. malachiticus and Sceloporus variabilis (a related species with the unaltered ancestral karyotype of Phrynosomatidae, 2n = 34) and analysed the recombination patterns in both autosomes and sex chromosomes.

2. Material and methods

The male specimens of S. malachiticus and S. variabilis were obtained from the pet trade. To confirm the species identification, the 5′-fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene was sequenced using protocols and primers described previously [30].

The primary fibroblast cell cultures of S. malachiticus were obtained in the Laboratory of Animal Cytogenetics, the Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Russia, using the protocols described previously [31,32]. All cell lines were deposited in the IMCB SB RAS cell bank (‘The general collection of cell cultures', 0310-2016-0002). Metaphase chromosome spreads were prepared from chromosome suspensions obtained from early passages of primary fibroblast cultures as described previously [33,34].

C-like 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was performed in the following way. The slides were incubated in 0.2 M hydrogen chloride (HCI) for 20 min at room temperature. Then they were kept in Ba(OH)2 solution at 55°C for 4 min, and then incubated in 2 × saline-sodium citrate buffer at 60°C for 60 min. Then they were washed in distilled water at room temperature, and stained with DAPI using the Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

The SC spreads of S. malachiticus and S. variabilis were prepared and immunostained as described previously, using the antibodies to SYCP3, the protein of the lateral element of the SC; to MLH1, the mismatch-repair protein which marks mature recombination nodules; and to CENP, the centromere proteins [35]. The overall recombination rate was estimated using the average r parameter suggested by Veller et al. [36]. This parameter takes into account chromosome number, crossover number and crossover location. The physical sense of average r is a probability of two randomly selected loci to recombine in a meiotic event. It has two components: the interchromosomal, which reflects recombination via independent chromosome segregation, and the intra-chromosomal, which reflects crossover recombination.

The flow-sorted chromosome samples of S. malachiticus were obtained using the Mo-Flo® (Beckman Coulter) high-speed cell sorter at the Cambridge Resource Centre for Comparative Genomics, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, as described previously [37]. The painting probes were generated from the degenerate oligonucleotide-primed polymerase chain reaction (DOP-PCR) amplified samples by a secondary DOP-PCR incorporation of biotin-dUTP and digoxigenin-dUTP (Sigma) [38]. FISH was performed with standard techniques [39].

The preparations were analysed with an Axioplan 2 imaging microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a charge-coupled device camera (CV M300, JAI), CHROMA filter sets and the ISIS4 image processing package (MetaSystems GmbH). The brightness and contrast of all images were enhanced using Corel PaintShop Photo Pro X6 (Corel Corp.).

For the preparation of the sorted chromosomes of S. malachiticus for sequencing, we used TruSeq Nano DNA Low Throughput Library Prep Kit (Illumina). Paired-end sequencing was performed on Illumina MiSeq using Reagent Kits v2, 600-cycles. The next generation sequencing (NGS) data were deposited in NCBI SRA database (PRJNA616430). Sequencing data were processed using the ‘DOPseq_analyzer’ pipeline [23,40]. The following parameters were used: for read trimming ‘ampl’ was set to ‘dop’, Illumina adapter trimming was enabled, additional cutadapt options ‘–trim-n –minimum-length 20’ were specified. Reads were aligned to A. carolinensis genome (AnoCar2.0) downloaded from Ensembl (www.ensembl.org) using the BWA MEM algorithm with default parameters. Additional filters were minimum MAPQ = 20 and minimum alignment length = 20. For target region identification, scaffolds with chromosome assignments and scaffolds over 50 kb in size were used. The key parameter in the ‘DOPseq_analyzer’ output to determine the target scaffolds and chromosomes is pd_mean, which is the mean distance between the positions of the scaffold which are covered by the sequencing reads. The target scaffolds are characterized by lower pd_mean and contaminant scaffolds are characterized by higher pd_mean. The position of the scaffolds on the chromosomes of A. carolinensis was determined using the data on their synteny to the chicken chromosomes, obtained from UCSC Genome Browser (www.genome.ucsc.edu), and the previously obtained data on the synteny between the Anolis and chicken chromosomes [21,23].

3. Results

(a) . Species identification and the mitotic karyotype of Sceloporus malachiticus

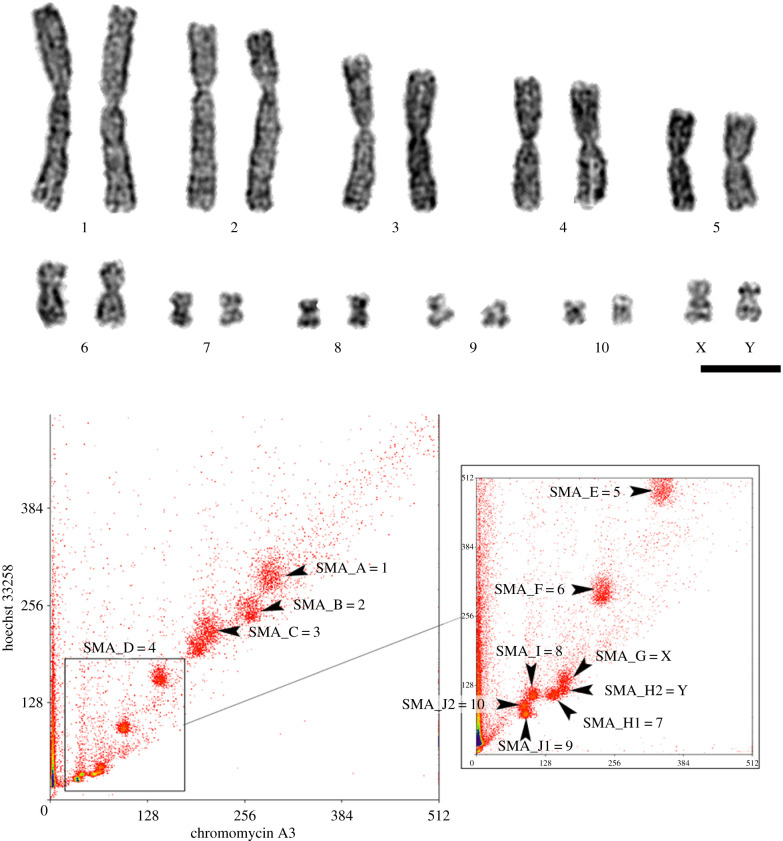

The COI gene sequence confirmed that the specimens studied belong to S. malachiticus (GenBank MT140115) and S. variabilis (GenBank MT131783). The mitotic karyotype of S. malachiticus was typical for the 2n = 22 clade of Sceloporus [26], and included six pairs of large metacentric chromosomes, medium-sized X and Y chromosomes, and four pairs of small metacentric chromosomes (figure 1a). The flow-sorted karyotype consisted of 12 peaks (figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Karyotype of S. malachiticus. (a) G-banded karyotype. Scale bar: 10 µm. (b) Flow-sorted karyotype. Peak IDs and contents are indicated by the arrowheads. X and Y axes: fluorescence intensity for each fluorochrome.

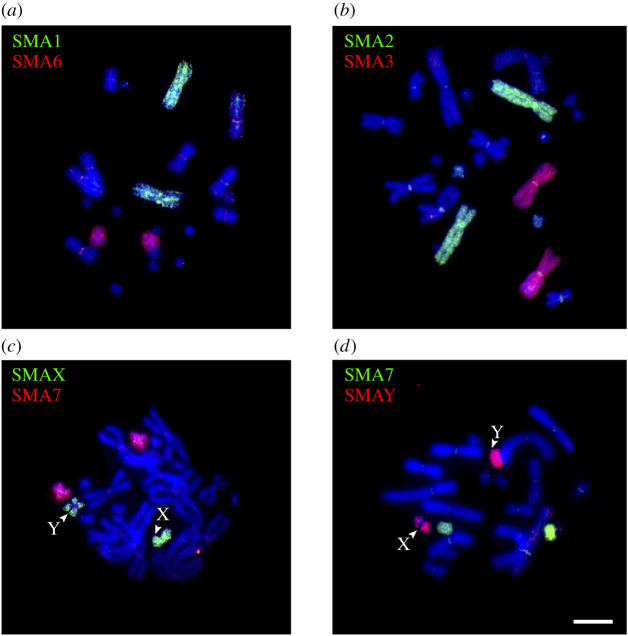

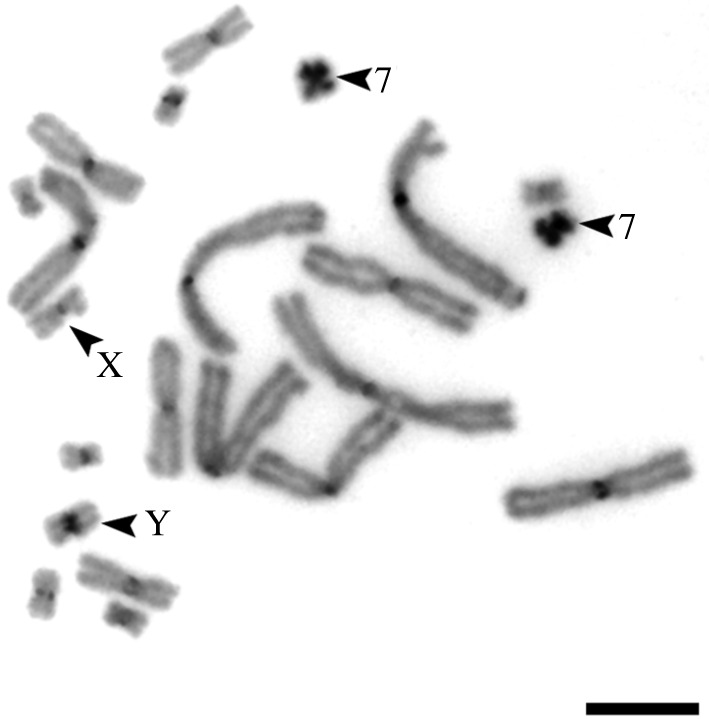

C-like DAPI staining showed DAPI-positive bands in the centromeres of each chromosome. The Y chromosome had a more prominent band than the X chromosome. Chromosome 7 was totally heterochromatic (figure 2).

Figure 2.

C-like DAPI staining of the S. malachiticus metaphase plate. Arrowheads indicate the heterochromatic chromosome 7 and the sex chromosomes. Scale bar: 10 µm.

(b) . Fluorescence in situ hybridization with the flow-sorted chromosome-specific probes

FISH with the labelled probes derived from each peak was performed on the metaphase plates of the same specimen. The probes derived from most peaks hybridized with single chromosome pairs (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Two peaks, SMA_G and SMA_H2, both hybridized with the sex chromosomes, and were concluded to correspond to the chromosomes X and Y, respectively. The peak SMA_H2 (mostly consisting of the Y chromosome), in addition, showed weak hybridization with the similar-sized chromosome 7 (mostly contained in the peak SMA_H1) probably owing to contamination during flow sorting (figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Examples of FISH with the flow-sorted chromosome-specific probes of the male S. malachiticus on its metaphase plates. Note that the sex chromosome-specific probes label the respective chromosomes across the whole length, but label the sex chromosomes of the opposite type (e.g. the SMA_X probe on the Y chromosome) only in the distal pseudoautosomal regions. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Both sex chromosome probes hybridized with the respective chromosomes along the whole length, but showed weaker or no hybridization in the medial, centromere-adjacent region of the homologous chromosome (figure 3c,d). This pattern corresponds to the presence of two homologous pseudoautosomal regions in the distal parts of the sex chromosomes, and the differentiated non-recombining regions in the middle.

(c) . Sequencing of the flow-sorted chromosome-specific probes

The NGS data analysis showed that the six largest macrochromosomes of S. malachiticus (SMA1–SMA6) correspond to the macrochromosomes of A. carolinensis (ACA1–ACA6), with two notable exceptions (table 1; electronic supplementary material, file S1).

Table 1.

The homology between the chromosomes of S. malachiticus and A. carolinensis, inferred from the NGS data.

| S. malachiticus chromosomes | A. carolinensis chromosomes |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2, 1 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 4 |

| 5 | 5 |

| 6 | 6, 1 |

| X | X, 11, 16, 17, 18 |

| Y | 11, 16, 17, 18 |

| 7 | 15 |

| 8 | 7, 10 |

| 9 | 9, 14 |

| 10 | 8, 12 |

In addition to high homology to ACA2, SMA2 shows homology with the segment located between the positions 204854915–205800612 of ACA1 (AnoCar2.0). In ACA1, this fragment represents an isolated segment of homology with the chicken chromosome 12 (GGA12), surrounded by the segments homologous to GGA3. It is notable that the segments homologous to GGA12 are mostly located on ACA2.

Similarly, SMA6, along with homology to ACA6, shows homology with the segment located between the positions 192604161 and 196661610 of ACA1 (AnoCar2.0). In ACA1, this genomic block is homologous to a segment of GGA2, and is also surrounded by the segments homologous to GGA3. The adjacent segments of GGA2 are homologous to ACA6.

The sex chromosomes of S. malachiticus contain the genomic blocks which are homologous to the chromosomes ACAX, ACA11, ACA16, ACA17 and ACA18. In the Y chromosome-specific DNA sample, 3 of 47 (6%) identified homologous ACA scaffolds belonged to ACAX, in contrast with 7 of 53 (13%) in the X chromosome. These scaffolds showed higher pd_mean than the scaffolds corresponding to other ACA chromosomes. They probably represent a contamination of the Y-sample by the X chromosome owing to similar size.

The chromosomes SMA8, SMA9 and SMA10 correspond to the chromosomes ACA7 + ACA10, ACA9 + ACA14 and ACA8 + ACA12, respectively. In the chromosome SMA7, only the genomic blocks homologous to ACA15 were found. Notably, the chromosome termed ‘chromosome 7’ in several recent studies on Sceloporus tristichus, another species with 2n = 22, in fact, represents the XX/XY chromosome pair. This follows from its position in the karyotype and reported gene content [41,42].

The data on the homology between the chromosomes of S. malachiticus and A. carolinensis are summarized in table 1 and the electronic supplementary material, file S1. Notably, of seven translocations that occurred in the S. malachiticus lineage, four involved the sex chromosomes and three were between three different combinations of micro-autosome pair.

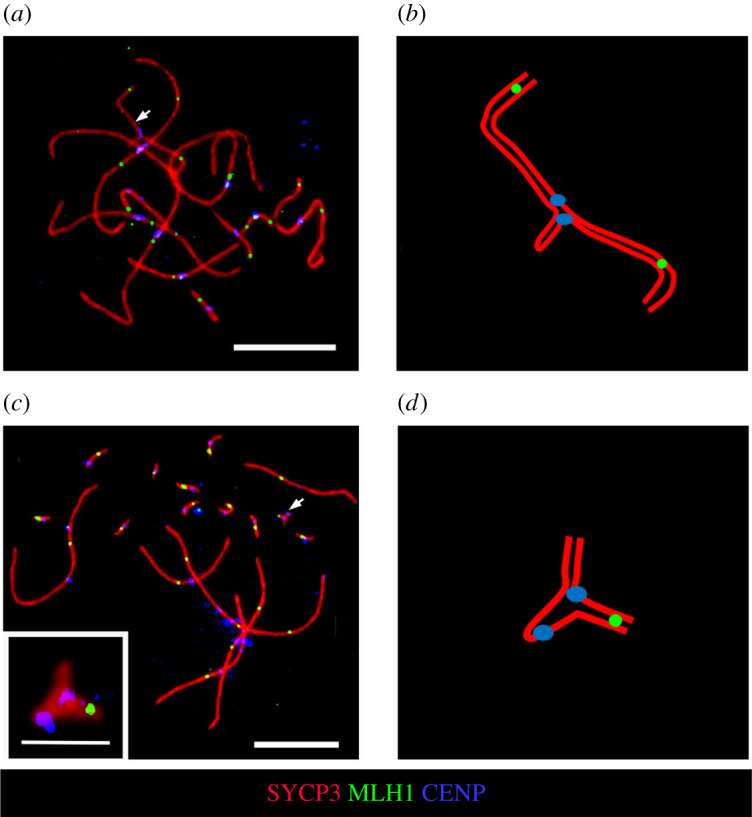

(d) . Synaptonemal complex analysis

The SC karyotype of S. malachiticus consisted of 11 metacentric bivalents, including the XY bivalent with misaligned centromeres and a lateral buckle on one of the homologues (figure 4a). This corresponds to the previously reported SC karyotype of a closely related species Sceloporus undulatus [28], and to the mitotic karyotype of S. malachiticus obtained in the present work. The recombination nodules, marked with the MLH1 protein, were located in the distal parts of the sex bivalent (figure 4b). Fifty-eight per cent (29 out of 50) of the analysed bivalents had one MLH1 focus, and 42% (21 out of 50) had two MLH1 foci. The two foci were always located on different arms. The SC karyotype of S. variabilis consisted of 17 bivalents: six metacentric macrochromosomal bivalents and 11 microchromosomal bivalents (figure 4c). This corresponds to its previously known mitotic karyotype [43]. One of the micro-bivalents consisted of homologues of unequal lengths, with the larger homologue forming a lateral buckle (figure 4c,d). It was concluded to be the sex bivalent, basing on its similarity with the previously studied micro-sex bivalents in Anolis [44]. The micro-bivalents, including the sex bivalent, always had one MLH1 focus.

Figure 4.

SC analysis of S. malachiticus (a,b) and S. variabilis (c,d). (a,c) Immunofluorescent staining of SC spreads. The sex bivalents are indicated by arrows. Scale bars: 10 µm. Inset: the micro-sex bivalent of S. variabilis, scale bar: 2 µm. (b,d) Schematic drawings of the sex bivalents.

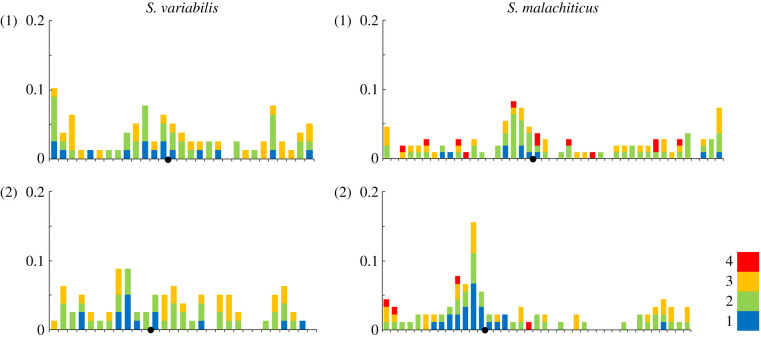

The average crossover number in S. malachiticus (15.6 ± 2.3 per spread) was significantly lower than in S. variabilis (20.9 ± 1.7 per spread) (p < 0.01). However, the r parameter shows that the lower number of crossovers in S. malachiticus reflects only its lower chromosome number and not a change in crossing over patterns: the intra-chromosomal components of r (0.032 ± 0.005 in S. malachiticus and 0.033 ± 0.006 in S. variabilis) are not significantly different (p > 0.05). It is notable that both species have crossover peaks not only near the telomeres, but also near the centromeres of macro-autosomes, with centromeric peaks more pronounced in S. malachiticus (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Numbers and distributions of the MLH1 foci on two largest chromosomes of S. variabilis and S. malachiticus. The x-axis shows the positions of MLH1 foci along the SCs in relation to the centromere (black circle). One scale division represents a segment of the average length of each SC equal to 1 µm. The y-axis shows the proportion of MLH1 foci in each interval. Different colours show bivalents with different MLH1 numbers, from 1 to 4.

4. Discussion

The results of FISH and whole-chromosome-specific DNA sequencing show that the sex chromosomes in S. malachiticus experienced more fusions than the autosomes. Both FISH and crossover mapping data show the presence of two distal pseudoautosomal regions, and a lack of homology between the X and Y chromosomes in the medial regions. This indicates that the autosomal fragments translocated onto the sex chromosomes from both sides. However, our methods do not allow the determination of the relative positions of each syntenic block inside the sex chromosomes. The fact that the non-recombining segment is flanked by two pseudoautosomal regions explains why novel translocations did not form a multiple sex chromosome system in this case. This may indicate that most multiple sex chromosome systems actually represent translocations onto non-recombining parts, when they are located terminally and are not flanked by pseudoautosomal regions. Otherwise, if there is a recombining segment between the sex-determining locus and the point of fusion, the fused autosomal segment can be transferred to another sex chromosome by crossing over, and a stable multiple sex chromosome complex cannot be formed.

Of the fusions which we identified in the sex chromosomes of S. malachiticus, several appear to be homoplasies, as they appear independently in different squamate lineages. Namely, the combination of the homologues of ACAX + ACA11 occur independently in Ctenonotus (Dactyloidae, Pleurodonta, Iguania) [24,25] and in the Z chromosome of Paroedura (Gekkonidae) [45]; the combination of the homologues of ACAX + ACA18 occur in Norops (Dactyloidae, Pleurodonta, Iguania) [23] and the combination of the homologues of ACA11 +ACA16 is characteristic for the Z chromosome of Lacertidae [46]. It is also notable that both in Norops and Sceloporus, the sex chromosomes stand out by undergoing more fusions than autosomes. However, the homologues of ACA9 and ACA12, which constitute the sex chromosomes of Norops along with ACAX and ACA18, are not fused with the sex chromosomes and with each other in S. malachiticus. The fusion of the homologues of ACA15 and ACA16, which created chromosome 12 of Norops [23], is also not found in S. malachiticus.

The autosomes, and especially macrochromosomes, were more stable during karyotypic evolution of S. malachiticus. The segments of ACA1 which show homology to SMA2 and SMA6 are homologous to the segments of the chicken chromosomes GGA12 and GGA2. Most parts of these chicken chromosomes have homology with SMA2/ACA2 and SMA6/ACA6, respectively. This indicates that these segments of ACA1 most probably represent relatively recent translocations from proto-ACA2 and proto-ACA6, which occurred in the Anolis lineage and are not shared by Sceloporus. Alternatively, this might represent an assembly error in the A. carolinensis genome.

SMA8, SMA9 and SMA10 contain homologues of two A. carolinenesis microchromosomes each (figure 1b and table 1). SMA7 is larger than other small autosomes, although its sequence shows homology only with ACA15. It is possible that SMA7 also contains genomic segments which are not covered or not assembled in the current version of the A. carolinensis genome, or is enlarged owing to repeat accumulation. The latter explanation is supported by the high heterochromatinization of SMA7 (figure 2).

The repeated involvement of the homologues of ACA11 in the formation of sex chromosomes requires special attention, because this chromosome is homologous to the sex chromosome system of therian mammals and carries the SOX3 gene. The syntenic region ACA18 contains the AMH gene and is independently involved in sex chromosome formation in varanids [47], Norops sagrei [23], platypus [48], frogs [49], and several species of teleosts [50,51]. Synteny with ACA16 (GGA17) was found in the Z chromosome of Pogona vitticeps (Agamidae, Acrodonta, Iguania) [22].

Although we detected some repeated sex chromosome–autosome fusions, the paucity of the available comparative data prevents us from determining whether certain chromosomes fuse with sex chromosomes significantly more frequently than others. More comprehensive understanding of our data and more detailed comparative analysis will be available with the emergence of more syntenic maps of squamates with sex chromosome–autosome fusions. In some of them, the existing syntenic maps cover only the homologues of the A. carolinensis macrochromosomes, as in lacertids [6] and geckos [7], or have too small numbers of markers, as in tuatara [46]. For others, i.e. skinks, syntenic maps do not exist at all [52].

Our data did not support the hypothesis that S. malachiticus could have lower crossing over rates than S. variabilis, a related species without multiple fusions (2n = 34). On the contrary, both species of Sceloporus show similar intra-chromosomal components of r, which are higher than in two previously studied Anolis species with 2n = 36 [35]. Thus, at least in the studied species of Pleurodonta, the crossover patterns depend more on the phylogenetic position of the species than on the structure of its karyotype. However, for all these four species, we studied only the recombination patterns in males. Studying the recombination patterns in females would be required to characterize meiotic crossing over more completely in these species.

The high overall r values in Sceloporus are owing to the centromeric peaks of crossover distribution in macro-autosomes, in contrast with Anolis, which demonstrate mostly distally located crossovers. As shown by Veller et al. [36], the median crossovers contribute much more to the effective recombination rate than distal ones. The centromeric localization of crossovers in Sceloporus, most pronounced in the 2n = 22 clade, have been shown previously by the analyses of meiotic metaphase chromosomes [26,28]. Although in these works, the crossovers in the macrochromosomes are reported as exclusively centromeric in the 2n = 22 species, we also detected minor telomeric crossover peaks in S. malachiticus. It is highly unusual for vertebrates to have crossover peaks near the centromeres: the more common pattern is a reduction of crossover rate in the centromeric regions, which is called the ‘centromere effect’ [53]. The physiological mechanisms and possible biological significance of the altered crossover patterns in Sceloporus deserve further study. However, despite the high overall r values, the loci which were involved in the sex chromosome–autosome fusions in S. malachiticus should experience decreased local recombination owing to the absence of recombination events in the medial part of the XY bivalent.

In conclusion, among the ancestral autosomes which fused with the sex chromosomes in S. malachiticus, we identified several chromosomes which are repeatedly involved in sex chromosome formation in different vertebrate lineages. However, more comparative syntenic data for different species, obtained by molecular cytogenetics and chromosome-level genome assemblies, are required to statistically test these observations. We did not find a support for the idea that multiple chromosomal fusions, including sex chromosome–autosome fusions, may be associated with major genome-wide changes in crossing over patterns.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Microscopic Center of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences for granting access to microscopic equipment. We thank I. Kichigin for help in NGS data analysis and K. Petrova for assisting in G-banding of S. malachiticus chromosomes.

Ethics

All manipulations with animals were approved by the Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology Ethics Committee (statement no. 01/18 from 5 March 2018).

Data accessibility

The NGS data were deposited in NCBI SRA database under the accession no. PRJNA616430.

Authors' contributions

A.P.L. performed the synaptonemal complex analysis and DNA barcoding. K.V.T. performed FISH. S.A.R. performed cell culturing. A.S.M. prepared the Illumina DNA libraries. D.Y.P. performed bioinformatic analysis. J.C.P. and M.A.F.-S. obtained the flow-sorted chromosome-specific probes. A.P.L., V.A.T. and P.M.B. designed the study. All authors participated in writing and editing the manuscript, gave final approval for publication and agree to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the research grant no. 19-54-26017 from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, the research grant no. 2019-0546 (FSUS-2020-0040) and no. 0324-2019-0042 from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Russia) via the Novosibirsk State University and the Institute of Cytology and Genetics.

References

- 1.Morescalchi A. 1977. Phylogenetic aspects of karyological evidence. In Major patterns in vertebrate evolution (ed. M Hecht), pp. 149-167. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braasch I, et al. 2016. The spotted gar genome illuminates vertebrate evolution and facilitates humanteleost comparisons. Nat. Genet. 48, 427-437. ( 10.1038/ng.3526) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uno Y, et al. 2012. Inference of the protokaryotypes of amniotes and tetrapods and the evolutionary processes of microchromosomes from comparative gene mapping. PLoS ONE 7, e53027. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0053027) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olmo E, Signorino G. 2005. Chromorep: a reptilies chromosomes database. See http://chromorep.univpm.it/.

- 5.Morescalchi A. 1980. Evolution and karyology of the amphibians. Boll. Zool. 47, 113-126. ( 10.1080/11250008009438709) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srikulnath K, Matsubara K, Uno Y, Nishida C, Olsson M, Matsuda Y. 2014. Identification of the linkage group of the Z sex chromosomes of the sand lizard (Lacerta agilis, Lacertidae) and elucidation of karyotype evolution in lacertid lizards. Chromosoma 123, 563-575. ( 10.1007/s00412-014-0467-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srikulnath K, Uno Y, Nishida C, Ota H, Matsuda Y. 2015. Karyotype reorganization in the Hokou gecko (Gekko hokouensis, Gekkonidae): the process of microchromosome disappearance in Gekkota. PLoS ONE 10, e0134829. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0134829) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deakin JE, Ezaz T. 2019. Understanding the evolution of reptile chromosomes through applications of combined cytogenetics and genomics approaches. Cytogenet Genome Res. 157, 7-20. ( 10.1159/000495974) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigeman H, Ponnikas S, Chauhan P, Dierickx E, De Brooke M, Hansson B. 2019. Repeated sex chromosome evolution in vertebrates supported by expanded avian sex chromosomes. Proc. R. Soc. B 286, 2019-2051. ( 10.1098/rspb.2019.2051) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rice WR. 1987. The accumulation of sexually antagonistic genes as a selective agent promoting the evolution of reduced recombination between primitive sex chromosomes. Evolution 41, 911-914. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1987.tb05864.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B. 1980. Sex differences in fitness and selection for centric fusions between sex-chromosomes and autosomes. Genet. Res. 35, 205-214. ( 10.1017/S0016672300014051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlesworth B, Wall JD. 1999. Inbreeding, heterozygote advantage and the evolution of neo-X and neo-Y sex chromosomes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 51-56. ( 10.1098/rspb.1999.0603) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pokorná M, Altmanová M, Kratochvíl L. 2014. Multiple sex chromosomes in the light of female meiotic drive in amniote vertebrates. Chromosome Res. 22, 35-44. ( 10.1007/s10577-014-9403-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pennell MW, Kirkpatrick M, Otto SP, Vamosi JC, Peichel CL, Valenzuela N, Kitano J. 2015. Y fuse? Sex chromosome fusions in fishes and reptiles. PLoS Genet. 11, e10005237. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005237) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashley T. 2002. X-autosome translocations, meiotic synapsis, chromosome evolution and speciation. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 96, 33-39. ( 10.1159/000063030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobigny G, Ozouf-Costaz C, Bonillo C, Volobouev V. 2004. Viability of X-autosome translocations in mammals: an epigenomic hypothesis from a rodent case-study. Chromosoma 113, 34-41. ( 10.1007/s00412-004-0292-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rovatsos M, Gamble T, Nielsen S, Georges A, Ezaz T, Kratochvíl L. 2020. Do male and female heterogamety really differ in expression regulation? Lack of global dosage balance in pygopodid geckos. bioRxiv. (doi:10.1101/2020.06.03.132241)

- 18.Marin R, et al. 2017. Convergent origination of a Drosophila-like dosage compensation mechanism in a reptile lineage. Genome Res. 27, 1974-1987. ( 10.1101/gr.223727.117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rupp SM, Webster TH, Olney KC, Hutchins ED, Kusumi K, Wilson Sayres MA. 2017. Evolution of dosage compensation in Anolis carolinensis, a reptile with XX/XY chromosomal sex determination. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 231-240. ( 10.1093/gbe/evw263) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acosta A, Mart Inez-Pacheco L, Iaz-Barba KD, Porras N, Guti Errez-Mariscal M, Cortez D. 2019. Deciphering ancestral sex chromosome turnovers based on analysis of male mutation bias. Genome Biol. Evol. 11, 3054-3067. ( 10.1093/gbe/evz221) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kichigin IG, et al. 2016. Evolutionary dynamics of Anolis sex chromosomes revealed by sequencing of flow sorting-derived microchromosome-specific DNA. Mol. Genet. Genomics 291, 1955-1966. ( 10.1007/s00438-016-1230-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deakin JE, et al. 2016. Anchoring genome sequence to chromosomes of the central bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps) enables reconstruction of ancestral squamate macrochromosomes and identifies sequence content of the Z chromosome. BMC Genomics 17, 447. ( 10.1186/s12864-016-2774-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alföldi J, et al. 2011. The genome of the green anole lizard and a comparative analysis with birds and mammals. Nature 477, 587-591. ( 10.1038/nature10390) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giovannotti M, et al. 2017. New insights into sex chromosome evolution in anole lizards (Reptilia, Dactyloidae). Chromosoma 126, 245-260. ( 10.1007/s00412-016-0585-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lisachov AP, Makunin AI, Giovannotti M, Pereira JC, Druzhkova AS, Caputo Barucchi V, Ferguson-Smith MA, Trifonov VA. 2019. Genetic content of the neo-sex chromosomes in Ctenonotus and Norops (Squamata, Dactyloidae) and degeneration of the Y chromosome as revealed by high-throughput sequencing of individual chromosomes. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 157, 115-122. ( 10.1159/000497091) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall WP. 2009. Chromosome variation, genomics, speciation and evolution in Sceloporus lizards. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 127, 143-165. ( 10.1159/000304050) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leaché AD, Banbury BL, Linkem CW, Nieto-Montes De Oca A, . 2016. Phylogenomics of a rapid radiation: is chromosomal evolution linked to increased diversification in North American spiny lizards (genus Sceloporus)? BMC Evol. Biol. 16, 63. ( 10.1186/s12862-016-0628-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reed KM, Sudman PD, Sites JW, Greenbaum IF. 1990. Synaptonemal complex analysis of sex chromosomes in two species of Sceloporus. Copeia 4, 1122-1129. ( 10.2307/1446497) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morescalchi A. 2009. Adaptation and karyotype in Amphibia. Ital. J. Zool. 44, 287-294. ( 10.1080/11250007709430182) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagy ZT, Sonet G, Glaw F, Vences M. 2012. First large-scale DNA barcoding assessment of reptiles in the biodiversity hotspot of Madagascar, based on newly designed COI primers. PLoS ONE 7, e34506. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0034506) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanyon R, Galleni L. 1991. A rapid fibroblast culture technique for high resolution karyotypes. Ital. J. Zool. 58, 81-83. ( 10.1080/11250009109355732) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romanenko SA, et al. 2015. Segmental paleotetraploidy revealed in sterlet (Acipenser ruthenus) genome by chromosome painting. Mol. Cytogenet. 8, 90. ( 10.1186/s13039-015-0194-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang F, O'brien PCM, Milne BS, Graphodatsky AS, Solanky N, Trifonov V, Rens W, Sargan D, Ferguson-Smith MA. 1999. A complete comparative chromosome map for the dog, red fox, and human and its integration with canine genetic maps. Genomics 62, 189-202. ( 10.1006/geno.1999.5989) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graphodatsky AS, Yang F, O'brien PCM, Perelman P. 2001. Phylogenetic implications of the 38 putative ancestral chromosome segments for four canid species. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 92, 243-247. ( 10.1159/000056911) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lisachov AP, Tishakova KV, Tsepilov YA, Borodin PM. 2019. Male meiotic recombination in the Steppe Agama, Trapelus sanguinolentus (Agamidae, Iguania, Reptilia). Cytogenet. Genome Res. 157, 107-114. ( 10.1159/000496078) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veller C, Kleckner N, Nowak MA. 2019. A rigorous measure of genome-wide genetic shuffling that takes into account crossover positions and Mendel's second law. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1659-1668. ( 10.1073/pnas.1817482116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang F, Carter NP, Shiu L, Ferguson-Smith MA. 1995. A comparative study of karyotypes of muntjacs by chromosome painting. Chromosoma 103, 642-652. ( 10.1007/BF00357691) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Telenius H, Carter NP, Bebb CE, Nordenskjöld M, Ponder BAJ, Tunnacliffe A. 1992. Degenerate oligonucleotide-primed PCR: general amplification of target DNA by a single degenerate primer. Genomics 13, 718-725. ( 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90147-K) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liehr T, Kreskowski K, Ziegler M, Piaszinski K, Rittscher K.. 2016. The standard FISH procedure. In Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) (ed. T Liehr), pp. 109-118. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makunin AI, et al. 2016. Contrasting origin of B chromosomes in two cervids (Siberian roe deer and grey brocket deer) unravelled by chromosome-specific DNA sequencing. BMC Genomics 17, 618. ( 10.1186/s12864-016-2933-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bedoya AM, Leache AD. 2020. Characterization of a large pericentric inversion in plateau fence lizards (Sceloporus tristichus): evidence from chromosome-scale genomes. bioRxiv. ( 10.1101/2020.03.18.997676) [DOI]

- 42.Leaché AD, Cole CJ. 2007. Hybridization between multiple fence lizard lineages in an ecotone: locally discordant variation in mitochondrial DNA, chromosomes, and morphology. Mol. Ecol. 16, 1035-1054. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03194.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Porter CA, Haiduk MW, Queiroz KDE. 1994. Evolution and phylogenetic significance of ribosomal gene location in chromosomes of squamate reptiles. Copeia 2, 302-313. ( 10.2307/1446980) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lisachov AP, Trifonov VA, Giovannotti M, Ferguson-Smith MA, Borodin PM. 2017. Immunocytological analysis of meiotic recombination in two anole lizards (Squamata, Dactyloidae). Comp. Cytogenet. 11, 129-141. ( 10.3897/CompCytogen.v11i1.10916) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rovatsos M, Farkačová K, Altmanová M, Johnson Pokorná M, Kratochvíl L. 2019. The rise and fall of differentiated sex chromosomes in geckos. Mol. Ecol. 28, 3042-3052. ( 10.1111/mec.15126) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Meally D, Miller H, Patel HR, Marshall Graves JA, Ezaz T. 2010. The first cytogenetic map of the tuatara, sphenodon punctatus. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 127, 213-223. ( 10.1159/000300099) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lind AL, et al. 2019. Genome of the Komodo dragon reveals adaptations in the cardiovascular and chemosensory systems of monitor lizards. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1241-1252. ( 10.1038/s41559-019-0945-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cortez D, Marin R, Toledo-Flores D, Froidevaux L, Liechti A, Waters PD, Grützner F, Kaessmann H. 2014. Origins and functional evolution of Y chromosomes across mammals. Nature 508, 488-493. ( 10.1038/nature13151) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miura I. 2018. Sex determination and sex chromosomes in Amphibia. Sex Dev. 11, 298-306. ( 10.1159/000485270) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bej DK, Miyoshi K, Hattori RS, Strüssmann CA, Yamamoto Y. 2017. A duplicated, Truncated amh gene is involved in male sex determination in an old world silverside. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 7, 2489-2495. ( 10.1534/g3.117.042697) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li M, et al. 2015. A tandem duplicate of anti-Müllerian hormone with a missense SNP on the Y chromosome is essential for male sex determination in Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005678. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005678) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lisachov AP, Poyarkov N, Pawangkhanant P, Borodin P, Srikulnath K. 2018. New karyotype of Lygosoma bowringii (Günther, 1864) suggests cryptic diversity. Herpetol. Notes 11, 1083-1088. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nambiar M, Smith GR. 2016. Repression of harmful meiotic recombination in centromeric regions. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 54, 188-197. ( 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.01.042) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The NGS data were deposited in NCBI SRA database under the accession no. PRJNA616430.