Abstract

Eosinophilic myocarditis is a rare and frequently fatal disease that is often undiagnosed until autopsy. We report a case of eosinophilic myocarditis with an unusual initial presentation of palpitations that subsequently evolved into ventricular tachycardia storm and death within 4 days. (Level of Difficulty: Beginner.)

Key Words: eosinophilic myocarditis, palpitations, polymorphic pre-mature ventricular contractions, ventricular tachycardia storm

Abbreviations and Acronyms: EM, eosinophilic myocarditis; PVC, pre-mature ventricular contractions; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia

Graphical abstract

History of presentation

A 31-year-old physically active and otherwise healthy woman presented with 2 days of palpitations to an outpatient clinic, where an electrocardiogram reportedly showed first-degree atrioventricular node block and frequent polymorphic pre-mature ventricular contractions (PVCs). Vital signs and physical examinations were unremarkable. Two days later, she went to the University Medical Center in New Orleans with worsening palpitations and fatigue. She was afebrile with blood pressure of 112/75 mm Hg and pulse of 113 beats/min on presentation.

Learning Objectives

-

•

Frequent symptomatic polymorphic pre-mature ventricular contractions should raise consideration of myocarditis in an otherwise healthy person.

-

•

Eosinophilic myocarditis can present without biomarker evidence of inflammation or other laboratory abnormalities.

Medical History

The patient had no past medical or surgical disease, and family history was remarkable only for atrial fibrillation in her mother. She was not taking any medications or supplements and had no history of substance abuse. She had no history of recent viral prodrome, syncope, or travel.

Differential Diagnosis

Malignant PVCs in an otherwise healthy young patient can be seen in myocarditis, cardiac sarcoidosis, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, inherited arrhythmic conditions, and cardiac ischemia from spontaneous coronary artery dissection. In this case, myocarditis was highest on the differential.

Investigations

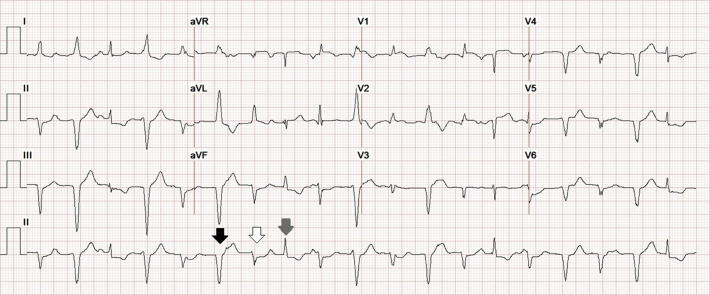

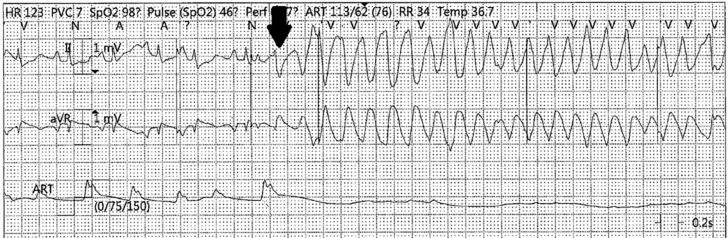

Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia at a rate of 113 beats/min with frequent polymorphic PVCs (Figure 1). White blood cell count, eosinophil count, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were normal. Additionally, the complete metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, creatinine phosphokinase, and urine drug screening results were normal. However, cardiac troponin I was elevated at 0.69 ng/ml and measured 0.57 ng/ml 6 h later. B-type natriuretic peptide was not measured.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram at Presentation

Sinus tachycardia at a rate of 113 beats/min with frequent polymorphic PVCs. A sinus beat (gray arrow) and 2 different PVC morphologies (black and white arrows), both likely originating from the posterobasal or posteromedial left ventricle, are highlighted (10).

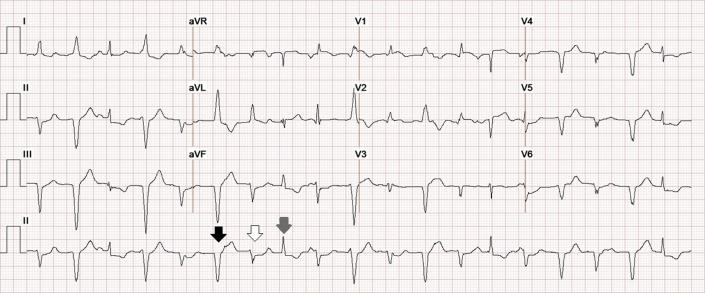

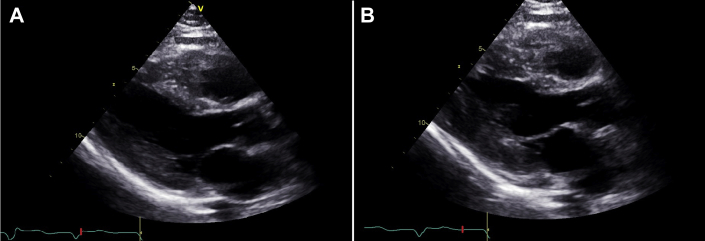

Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated normal chamber sizes and wall thickness, normal left and right ventricular systolic function with basal anteroseptal hypokinesis, no pericardial effusion, and abnormal left ventricular global longitudinal strain of –11% with apical sparing pattern (Figures 2 and 3). Serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation showed no monoclonal protein spike, and serum free light-chain ratio was normal.

Figure 2.

Transthoracic Echocardiogram

(A) End-diastolic and (B) end-systolic frames of the parasternal long-axis view. Left and right ventricular function and wall thickness were normal, with left ventricular basal anteroseptal hypokinesis.

Figure 3.

Polar Plot of Peak Longitudinal Strain

Speckle-tracking peak global longitudinal strain of the left ventricle is reduced at -11% with an exaggerated apical sparing pattern. ANT = anterior; INF = inferior; LAT = lateral; POST = posterior; SEPT = septal.

Management

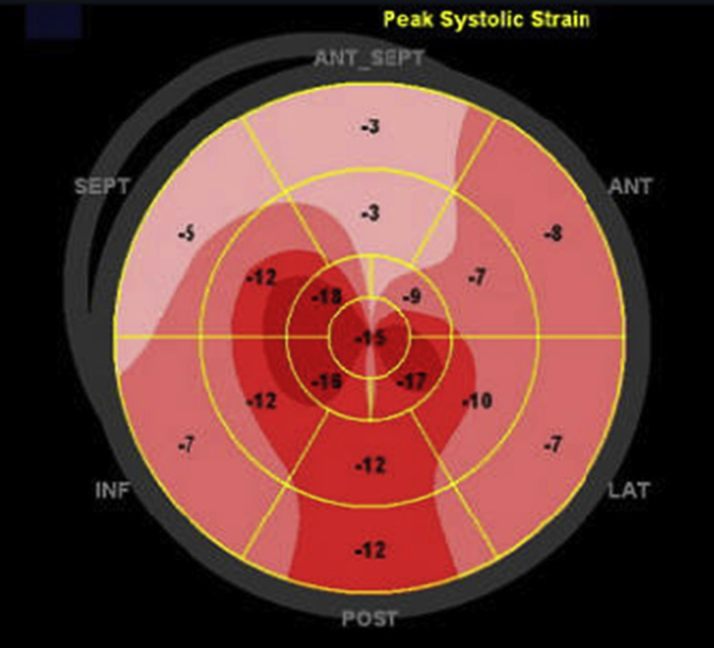

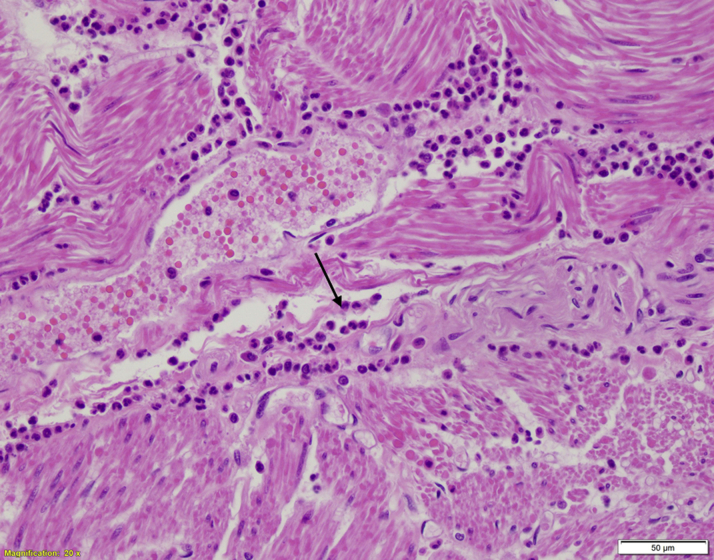

The patient was admitted to a telemetry bed and started on oral metoprolol, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was ordered. Approximately 15 h after admission and before performance of the cardiac magnetic resonance study, the patient went into cardiac arrest. The initial rhythm was polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) requiring electrical defibrillation before the return of spontaneous circulation. Amiodarone and, later, lidocaine were administered intravenously for refractory VT; the patient was intubated and sedated with fentanyl and midazolam. She was started on methylprednisolone empirically for myocarditis. The patient continued to have episodes of sustained VT, and she was taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory, where her coronary arteries were found to be normal without evidence of vasospasm. Right heart catheterization and endomyocardial biopsy were not obtained. Overdrive transvenous pacing was initiated, followed by therapeutic paralysis with cisatracurium. She continued to have incessant polymorphic VT and ventricular fibrillation (VF) requiring frequent electrical defibrillation (Figure 4). Safe transfer to a center with advanced mechanical circulatory support was not believed to be an option, and she eventually died. Autopsy revealed diffuse interstitial infiltrates with extensive involvement of eosinophils and mast cells throughout the left and right ventricular myocardium consistent with eosinophilic myocarditis (Figure 5). There was no evidence of infection, vasculitis, hypersensitivity, or any other kind of malignancy.

Figure 4.

Rhythm Strip

Rhythm strip before cardiac arrest with R-on-T phenomenon (black arrow) triggering ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 5.

Autopsy Histopathology (Hematoxylin and Eosin)

Cardiac myocytes with interstitial inflammatory infiltrate composed of numerous eosinophils (black arrow) and occasional mast cells throughout the left and right ventricular myocardium, consistent with eosinophilic myocarditis with minimal necrosis.

Discussion

Eosinophilic myocarditis (EM) is a rare inflammatory disorder of the heart that is characterized histologically by eosinophilic infiltration of the myocardium. Although often idiopathic, as it appears to have been in our case, EM has been associated with drug hypersensitivity reactions, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, hypereosinophilic syndromes, infections, and malignancies, none of which were present in this patient on autopsy (1,2). The diagnosis of EM can be challenging and is made exclusively at the time of autopsy in 19% of reported cases (3). Although biomarkers of inflammation can help in the diagnosis, peripheral eosinophilia and C-reactive protein elevation are each absent in more than 20% of cases (4). Unfortunately, there are no proven therapies for this condition (5).

EM often presents with dyspnea, chest pain, fever, or nonspecific symptoms. Palpitations are a rare presenting symptom, occurring in only 1% of published reports (3). Our case is particularly instructive because of the rapid deterioration to VT storm, which has been reported only once previously (3) to our knowledge.

Although PVCs are often thought to have a benign prognosis, in a recent single-center prospective study, 51% of patients with frequent symptomatic PVCs and without ischemic heart disease met diagnostic criteria for myocarditis (6). More recently, polymorphic PVCs have been shown to be characteristic of acute rather than chronic myocarditis (7). When assessing PVCs, it is important to note the presence of higher-risk features, including frequent or polymorphic PVCs, worsening ectopy with exercise, wider QRS duration, a short coupling interval, and a non–outflow tract origin (8). Our patient exhibited several high-risk features, including frequent and polymorphic PVCs from a non–outflow tract location in the posterobasal or posteromedial left ventricle. Given the lack of proven therapies for eosinophilic myocarditis, electrical instability should prompt consideration of early transfer to a center with advanced mechanical circulatory support.

Additionally, as in the current case, myocardial strain by speckle-tracking echocardiography may show an apical sparing pattern. To our knowledge, the only prior report that described an echocardiography strain pattern for a patient with EM also reported apical sparing (9).

Follow-Up

There was no follow-up encounter with this patient because she died during her initial hospitalization.

Conclusions

We present an unusual case of acute fulminant EM presenting with palpitations and PVCs that rapidly progressed to refractory VT storm and, eventually, death. This clinical case illustrates the need to recognize the high-risk features of PVCs and, when appropriate, to raise clinical suspicion for myocarditis.

Funding Support And Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

Marat Fudim, MD, served as Guest Associate Editor for this paper.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Kuchynka P., Palecek T., Masek M. Current diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of eosinophilic myocarditis. Biomed Res Int 2016. 2016:2829583. doi: 10.1155/2016/2829583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts W.C., Kietzman A.T. Severe eosinophilic myocarditis in the portion of the left ventricular wall excised to insert a left ventricular assist device for severe heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2020;125:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brambatti M., Matassini M.V., Adler E.D. Eosinophilic myocarditis: characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2363–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudhry M.A., Grazette L., Yoon A. Churg-Strauss syndrome presenting as acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis: concise review of the literature. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2014;15:8–12. doi: 10.2174/1573402114666180903164900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kociol R.D., Cooper L.T., Fang J.C. Recognition and initial management of fulminant myocarditis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e69–e92. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakkireddy D., Turagam M.K., Yarlagadda B. Myocarditis causing premature ventricular contractions insights from the MAVERIC registry. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019;12 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.119.007520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peretto G., Sala S., Rizzo S. Ventricular arrhythmias in myocarditis: characterization and relationships with myocardial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1046–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorenek B., Fisher J.D., Kudaiberdieva G. Premature ventricular complexes: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations in clinical practice: a state-of-the-art review by the American College of Cardiology Electrophysiology Council. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2020;57:5–26. doi: 10.1007/s10840-019-00655-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isaza N., Bolen M.A., Griffin B.P. Functional changes in acute eosinophilic myocarditis due to chemotherapy with Ibrutinib. CASE (Phila) 2019;3:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.case.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Segal O.R., Chow A.W.C., Wong M.R.C.P. (2007). A novel algorithm for determining endocardial VT exit site from 12-lead surface ECG characteristics in human, infarct-related ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:161–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]