Abstract

The objective of this study was to describe the frequency, potential harm, and nature of electronic health record (EHR)-related medication errors in intensive care units (ICUs). Using a secondary data analysis of a large database of medication safety events collected in a study on EHR technology in ICUs, we assessed the EHR relatedness of a total of 1622 potential preventable adverse drug events (ADEs) identified in a sample of 624 patients in 2 ICUs of a medical center. Thirty-four percent of the medication events were found to be EHR related. The EHR-related medication events had greater potential for more serious patient harm and occurred more frequently at the ordering stage as compared to non–EHR-related events. Examples of EHR-related events included orders with omitted information and duplicate orders. The list of EHR-related medication errors can be used by health care delivery organizations to monitor implementation and use of the technology and its impact on patient safety. Health information technology (IT) vendors can use the list to examine whether their technology can mitigate or reduce EHR-related medication errors.

INTRODUCTION

Electronic health record (EHR) use has produced patient safety benefits but has also created new medical errors, including medication errors. The 2012 Institute of Medicine report, Health IT and Patient Safety: Building Safer Systems for Better Care, summarizes research as follows: “While some studies suggest improvements in patient safety can be made, others have found no effect. Instances of health IT-associated harm have been reported.”1(pS2) EHR safety is a major problem in health care.2 Fifty-three percent of respondents to a recent survey of members of the American Health Lawyers Association and the American Society for Healthcare Risk Management report experiencing EHR-related serious events in the past 5 years.3 A study of Finnish EHR users confirms this widespread concern for EHR safety.4 A recent sentinel event alert from the Joint Commission highlights the importance of the safe use of health information technology (IT), including the evaluation of health IT-related adverse events and modifications necessary to avoid patient harm.5 This study examines health IT-associated harm in the major category of medication errors.

Several studies have reported EHR-related medication errors. For instance, Koppel et al.6 identified 22 types of medication error that were “facilitated” by computerized physician order entry (CPOE). Research has focused on (1) specific phases of the medication management process, for example, patient identification errors in CPOE system before writing orders,7 prescribing errors related to CPOE or EHR,8-10 and errors in medication administration11; (2) specific categories of medication, for example, antineoplastic drugs,12 aminoglycosides,13 and concomitant orders for warfarin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole14; or (3) specific types of medication error related to CPOE, such as duplicate orders.15,16 However, systematic, prospective studies identifying EHR-related errors across the entire medication management process (eg, Walsh et al.17) are rare.

Walsh et al.17 conducted a study in a pediatric hospital and assessed a total of 352 randomly selected inpatient admissions over a period of 9 months post-CPOE implementation. The error identification methodology used in this study was based on the protocol of Bates and colleagues,18 which is similar to the methodology used in our study. After identification of medication errors, 2 pediatricians rated errors as computer-related “only if the errors were highly unlikely to occur in a paper-based system and had a clear computer-based mechanism.”17(p1874) They found 19% of the medication errors to be computer-related; this was a rate of 10 errors per 1000 patient-days. A strength of this study is the collection of data on EHR-related medication errors across the entire medication management process. Its limitations include (1) focus on pediatric hospital, and (2) general rather than systematic approach to “EHR relatedness.” In this study, we systematically assess EHR-related medication errors in a group of vulnerable critically ill adult patients; the sample is twice as large as that of Walsh et al.17

CONCEPTUALIZATION OF EHR-RELATED MEDICATION ERRORS

EHR implementation in the complex hospital environment can create various changes, for example, unintended consequences,19 workarounds,20 and “technological iatrogenesis.”21 The 2005 JAMA paper by Koppel et al.6 raised major discussion about the role of CPOE (one component of EHR technology) in medication errors. Later studies have examined technology-induced errors,10 medication errors related to CPOE,17 computer-related errors,22 or health IT safety problems.23 Several frameworks have been proposed to describe errors and other problems that occur post-EHR implementation.2,24,25 Whereas this research is important, efforts are needed to clarify and operationalize the “EHR-related” concept. Some studies rely on perceptions by researchers,26 physicians,27,28 or lawyers and risk managers3 to assess EHR-related safety. Other studies analyze events reported by clinicians who mention the involvement of technology; these events are then coded by researchers into various categories or some taxonomy.23,25,29,30 A few studies have defined specific criteria for EHR-related medication safety. As indicated above, Walsh et al.17 asked physicians to rate medication errors as being computer-related only “if the errors were highly unlikely to occur in a paper-based system and had a clear computer-based mechanism.”17(p1874) Samaranayake et al.31 defined technology-related medication errors as “any error related to a technology used in the medication use process, which would not have happened if not for the use of this technology.”31(p829) In a similar manner, Stultz et al.32 defined IT-related errors based on the actual technology available at the time of the error.

Building on existing research on EHR-related safety, we operationalize EHR-related medication errors by using causality mechanisms and the Naranjo algorithm for adverse drug reactions.33 Table 1 displays the 4 questions used to assess EHR relatedness of medication errors.

Table 1:

Assessment of EHR Relatedness of Medication Errors

| Questions | Assumed to Be EHR Related If … |

|---|---|

| 1. Is there direct evidence for this type of error in the literature as being EHR-related? | Yes |

| 2. Is there a possible mechanism for this error being EHR-related? | Yes |

| 3. Could this error have been prevented with a technology redesign? | Yes |

| 4. Are there other non-EHR factors that could explain the error? | No |

An EHR-related medication error is, therefore, defined as a medication error with the following 4 conditions:

There is some evidence in the literature for this type of error as being EHR-related (Yes to question 1).

We can identify an EHR-related mechanism for this error (Yes to question 2).

The error could be prevented with a technology redesign (Yes to question 3).

There are no other non-EHR factors that could explain the error (No to question 4).

In this study, we conducted a secondary analysis of a large database of medication safety events collected in an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)-funded study on EHR technology in ICUs (http://cqpi.wisc.edu/computerized-provider-order-entry-in-icus.htm).34 The objectives of the secondary data analysis were (1) to quantify the incidence of EHR-related medication errors, (2) to assess the harm associated with EHR-related medication errors, and (3) to describe the nature of EHR-related medication errors.

METHODS

We conducted a secondary analysis of medication safety events identified in 2 ICUs of a large medical center. Our early findings of the larger study show the complexity of medication safety events35 and assess the impact of EHR implementation on medication safety.34 Details on the study can be found at http://cqpi.wisc.edu/computerized-provider-order-entry-in-icus.htm.

In this article, we describe the creation of an algorithm applied to medication safety data to assess whether medication errors are related to EHR technology. We also conduct descriptive analyses on the nature and potential harm of EHR-related errors as compared to medication errors that were not related to EHR. We obtained IRB approval from the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the study hospital.

Sample and setting

We collected medication safety data in 2 intensive care units (ICUs) of a 400-bed tertiary care, community teaching hospital located in the northeastern United States. At the time of data collection, the adult ICU held 24 beds and provided care to critical care, trauma, and noncardiac postsurgical patients. The average length of stay was 8.1 days. Intensivists were primarily responsible for most patients, with the exception of surgical patients who were cared for by surgeons with consultative input from intensivists. The cardiac ICU held 18 beds and provided care to medical and surgical cardiovascular patients, including solid organ transplant patients. The unit sometimes held pulmonary/critical care overflow patients as well. The average length of stay was 4.9 days.

An EHR (EpicCare Inpatient Clinical System, Spring 2006) was implemented in the study hospital in October 2007. Included in the EHR system were CPOE, electronic medication administration records (eMARs), a pharmacy system, and electronic provider documentation. The hospital had implemented electronic nursing documentation in June 2005.

The medication management process begins with providers entering all medication orders directly into the EHR. Providers would often enter the first part of the medication name into a search field and then select a medication, dose form, and route from a computer-generated pick list. In the medication ordering screen, defaults would be prefilled for doses, dosing units, routes, and frequencies, based on the most common order for the medication. Providers could change the default dose, route, and frequency by clicking on a button or entering the desired value into a free text field. Providers would select dosing units from a drop-down menu. Prebuilt medication orders could be selected from a preference list or an order set. Default start times and administration schedules were added by the system, such that the first dose should be given at the next 5-minute time interval from the time the order was placed. Administration times would then continue on the routine administration schedule. Providers could make changes by entering free text administration instructions or free text comments about the order. At all times during medication ordering, drug allergies were visible in red at the top of the patient record. Each provider could only have one electronic patient record open at a time.

After the provider electronically signed the order, the system conducted checks for drug allergies, drug-drug interactions and duplicate orders. Information about any issues identified was listed in a pop-up alert displayed to the ordering provider, who was required to enter the reason for overriding the alert unless the order was canceled or modified. Pharmacists also received the medication alerts, including what action the provider took in response to the alert. For orders with overridden alerts, an icon appeared on the MAR with the order to inform other clinicians.

A pharmacist reviewed each order for appropriateness. Because the pharmacy computer system was integrated with the medication ordering system, no transcription was required. Orders appeared in an integrated eMAR that also displayed scheduled administration times. Nurses would enter the time of medication administration, either by allowing the computer to use the current date/time stamp or by entering a time. Upon entering a patient record, the MAR alerted nurses of any overdue medication doses.

Data collection and adjudication

Data were collected prospectively on a total of 624 consecutive ICU admissions between March and June 2008. The data collection method used an adapted version of the protocol developed by Bates and colleagues18 and has been described in a previous publication.35 Four trained nurse data collectors reviewed medication orders daily, identifying errors and adverse drug events (ADEs). All of the errors and ADEs related to a single order are treated as a single case in our data set and are referred to as an event. We identified events involving a single error, a grouping of errors, and sequential errors.35

Two adjudication processes were used (1) to determine the type of medication errors and the stage of medication management in which the error occurred (eg, ordering, administration), and (2) to determine whether the patient suffered harm related to the medication error(s) and the level of harm or potential harm. Interrater reliability of the first adjudication process was high (Cohen’s kappa scores of 0.97),34,35 whereas adjudication of actual or potential harm produced low reliability, but similar to that found in other studies.36 Therefore, 2 physicians adjudicated the level of patient harm separately. If the 2 physicians did not agree on the harm adjudication, a third physician reviewed each event and resolved the discrepancy. Additional details on the adjudication processes can be found in previous publications.34,35

For this article, we include medication errors that had potential to cause patient harm but did not actually harm patients (841 potential preventable ADEs), and errors that had no potential to cause patient harm (781 no-harm medication errors). We do not include data for the 81 actual preventable ADEs that caused patient harm because of their small number and the fact that data were collected differently for these complicated events.

Adjudication of EHR relatedness

Every event in the medication safety database was evaluated for EHR relatedness. This evaluation was based on description of the events and information on the medication errors involved in the event. Initially, 2 researchers independently evaluated 45 events in order to assess interrater reliability of the EHR relatedness evaluation methodology. The kappa values for the 4 questions listed in Table 1 were as follows: question 1: 0.78, question 2: 0.82, question 3: 0.64, and question 4: 0.72. The adjudication for EHR relatedness also involved an overall question: “Is the event EHR related or not?” The kappa value for this overall question was 0.82. Consensus between the 2 researchers on the 45 events was obtained after discussion. One researcher then evaluated the remaining medication events on the questions on EHR relatedness.

Data analysis

Using the indicator of EHR relatedness (see below), we conducted descriptive analyses showing the percentage of events that are EHR related and the level of potential harm associated with EHR-related events. We also examined the medication errors occurring in EHR-related events. For most events, we include in the analysis the single error category associated with the event. For events with sequential errors, we use the error category of the last error in the sequence. Of the 66 events with a grouping of errors, 21 had multiple errors in a single category, which was included in the analysis. For the remaining 45 events, a researcher reviewed the events and selected the error category that was most appropriate to include.

RESULTS

Indicator of EHR relatedness

Due to issues of collinearity as well as small cell sizes, typical logistic regression analysis was not able to provide insight into a predictive algorithm of EHR relatedness. Instead, we used a Bayesian network to assess the probabilistic relationships among the indicators of EHR relatedness. Specifically, we used a binary Bayesian classification routine Netica37 to establish the rules for EHR-relatedness (see Table 2).

Table 2:

Rules for EHR Relatedness Based on the Bayesian Analysis

| Rules | Probability of “Yes” on the Single EHR-Related Question |

Number of Events |

|---|---|---|

| RULE 1. If Q1 = 1 and Q2 = 1 and Q3 = 1 and Q4 = 1 | 0.98 | 263 events |

| RULE 2. If Q1 = 1 and Q2 = 1 and Q3 = 1 and Q4 = 0 | 1.00 | 294 events |

| RULE 3. If Q1 = 0 and Q2 = 1 and Q3 = 1 and Q4 = 1 | 0.00 | 6 events |

| RULE 4. If Q1 = 0 and Q2 = 0 and Q3 = 1 and Q4 = 1 | 0.00 | 488 events |

| RULE 5. If Q1 = 0 and Q2 = 0 and Q3 = 0 and Q4 = 1 | 0.00 | 564 events |

| RULE 6. If Q1 = 0 and Q2 = 0 and Q3 = 0 and Q4 = 0 | 0.00 | 7 events |

Q1: Is there direct evidence for this type of error in the literature as being EHR-related?

Q2: Is there a possible mechanism for this error being EHR-related?

Q3: Could this error have been prevented with a technology redesign?

Q4: Are there other non-EHR factors that could explain the error?

We used the rules to create an indicator of EHR relatedness. We defined EHR-related events as following rules 1 and 2 and non–EHR-related events as following rules 3 to 6. By this definition, 557 events of 1622 (34%) were found to be EHR related. To assess the validity of the new indicator, we compared it to the single-item adjudication of EHR relatedness. For all but 9 cases, the results of the algorithm matched the adjudication. A researcher reviewed the 9 cases that did not match and assigned a value for the indicator of EHR relatedness. Our final measure indicates that 551 of 1622 medication safety events (34%) were EHR related.

Potential harm and EHR relatedness

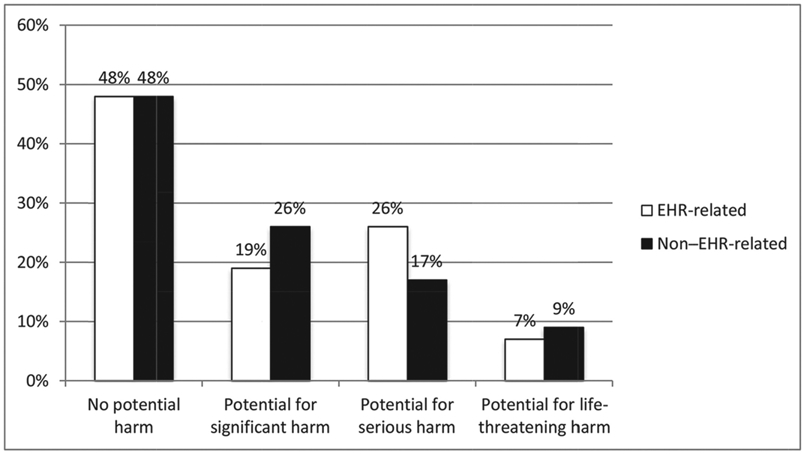

We conducted descriptive analyses comparing the amount of potential harm for EHR-related medication safety events to those that were not EHR related. As can be seen in Figure 1, 20% of events had the potential for serious harm, and these events were more likely to be EHR related (26% compared to 17% for non–EHR-related events, p < .001), while events with the potential to cause significant harm were less likely to be EHR related (19% compared to 26% for non–EHR-related events, p < .001).

Figure 1: Level of Potential Harm of EHR-Related Events and Non–EHR-Related Events.

Note: Pearson chi-square = 22.94, p < .001

Medication errors

We also examined EHR-related medication safety events by stage in the medication management process and error type (Table 3). EHR- and non–EHR-related medication errors were not distributed equally across stages (chi-square test: p < .001): ordering errors represented a larger proportion of EHR-related events (56%) as compared to non–EHR-related events (37%). On the other hand, administration errors were more frequent among non–EHR-related events (58%) as compared to EHR-related events (40%). Error types that were often related to the EHR included wrong patient ordering errors, administration of a medication without a medication order, omitted information when ordering, and ordering a medication for a patient with a known allergy. Frequent errors that were less commonly EHR related included ordering an underdose, dispensing errors, omitted medication administrations, late medication administrations, and monitoring errors. Note that omitted and late administration errors occurred so frequently that, although only 23% of these events are EHR related, they are among the 3 most common types of EHR-related errors, that is, duplicate ordering errors (92 events), omitted administration (76 events), and late administration (79 events).

Table 3:

Error Categories by EHR Relatedness

| Error Stage | Error Category | EHR-Related Errors |

Non–EHR-Related Errors |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordering | Overdose | 37 | 41% | 53 | 59% | 90 |

| Underdose | 15 | 22% | 53 | 78% | 68 | |

| Omitted information | 16 | 67% | 8 | 33% | 24 | |

| Wrong patient | 4 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 4 | |

| Wrong drug | 34 | 50% | 34 | 50% | 68 | |

| Allergy | 8 | 62% | 5 | 38% | 13 | |

| Drug-drug interaction | 0 | 0% | 2 | 100% | 2 | |

| Wrong start/stop time | 41 | 44% | 53 | 56% | 94 | |

| Duplicate | 92 | 56% | 73 | 44% | 165 | |

| Inappropriate or wrong rate, frequency, form, concentration, or other information | 53 | 33% | 107 | 67% | 160 | |

| Other ordering error | 9 | 47% | 10 | 53% | 19 | |

| Preparation | Preparation | 0 | 0% | 1 | 100% | 1 |

| Dispensing | Dispensed late or not dispensed | 15 | 28% | 38 | 72% | 53 |

| Other dispensing error | 1 | 25% | 3 | 75% | 4 | |

| Administration | Overdose | 0 | 0% | 2 | 100% | 2 |

| Underdose | 0 | 0% | 3 | 100% | 3 | |

| Wrong patient | 0 | 0% | 1 | 100% | 1 | |

| Omitted dose | 79 | 23% | 261 | 77% | 340 | |

| Late administration | 76 | 23% | 248 | 77% | 324 | |

| Wrong documentation | 47 | 35% | 88 | 65% | 135 | |

| Administered, no order | 14 | 82% | 3 | 18% | 17 | |

| Other administration error | 6 | 30% | 14 | 70% | 20 | |

| Monitoring | Monitoring | 4 | 27% | 11 | 73% | 15 |

| Total | 551 | 34% | 1071 | 66% | 1622 | |

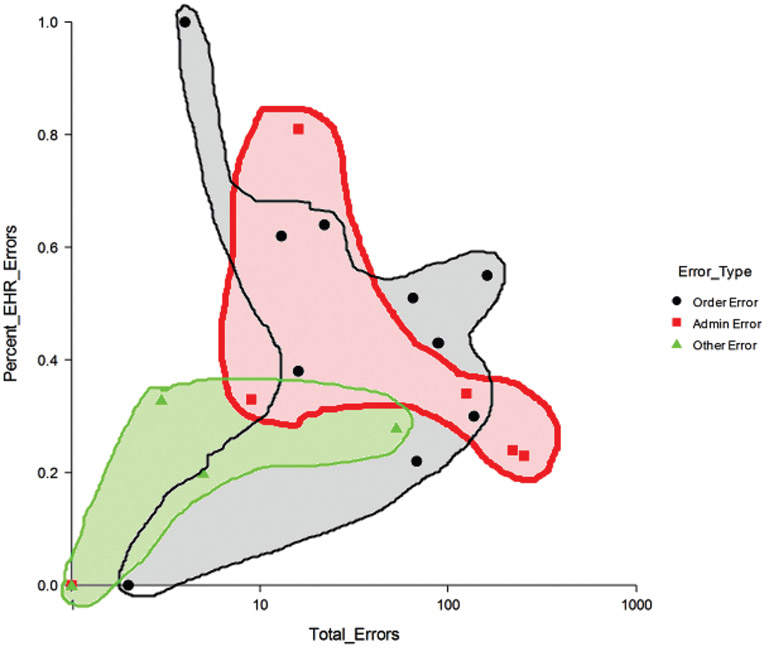

We then examined the ratio of EHR-related errors to all errors. The error categories with the highest ratio of EHR-related errors are often ordering errors, such as orders with omitted information and duplicate orders. Excluding categories with a very small number of events, the lowest ratio of EHR-related errors is found for ordering errors (underdose), administration errors (omitted doses and late administration), monitoring errors, and dispensing errors (late dispensing). Figure 2 shows the relationship between the frequency of errors (measured on the x-axis) and the percentage of EHR-related medication safety events (y-axis). The color and shape of each point on the graph indicates the stage in the medication management process in which the error occurs. For example, the 2 small red squares on the far right of the figure indicate that 2 types of administration error (late administrations and omitted administrations) occur frequently but are not often EHR related. The small black circle at the top left of the figure indicates that a type of ordering error (wrong patient) occurs rarely but was always found to be EHR related.

Figure 2: Frequency of Errors and EHR Relatedness by Stage of the Medication Management Process.

Table 4 shows examples of EHR-related medication errors in selected error categories.

Table 4:

Examples of EHR-Related Medication Errors

| Error Stage | Error Category | Examples of EHR-Related Error |

|---|---|---|

| Ordering | Overdose | Interface design made it challenging to enter a one-time dose in addition to existing order of daily dose. |

| Omitted information | EHR is designed to guide entry of information, but there are no hard stops for missing information (but hard stops may lead to questionable information being entered). | |

| Wrong drug | Wrong drug may be ordered when, for example, 2 drugs with similar names appear next to one another on the order screen. | |

| Allergy | Poor design of alerts for drug allergy may lead to alerts being ignored or overridden. | |

| Wrong start/stop time | Default start times are provided, but prescribers may not have necessary knowledge to specify start/stop times. | |

| Duplicate | Poor design of alerts for duplicate medication orders may lead to alerts being ignored or overridden. | |

| Administration | Wrong documentation | Medication administration is documented in clinician note, but not in eMAR. |

| Administered, no order | Medication may be given without order: change in patient status led provider to cancel medication, but it was unclear to the nurse that the medication had been canceled. |

DISCUSSION

In this study of ICU medication error occurrence after the implementation of an EHR with CPOE, eMAR, integrated pharmacy system, and clinician documentation, we found that one-third of all medication errors were EHR related, and of those, one-third had the potential for life-threatening or serious harm. Of great concern is that EHR-related errors had the potential for more serious patient harm compared to non–EHR-related errors.

The study by Walsh et al.17 found that only 19% of all medication errors identified in a pediatric ICU were related to CPOE. We found a higher percentage of EHR-related medication errors: 34%. It is possible that we identified a higher proportion of EHR-related medication errors because of greater computerization in the medication management process. The study by Walsh et al. focused on CPOE, whereas our study assessed a more comprehensive EHR technology that included not only CPOE, but also documentation and electronic MAR and pharmacy system. A retrospective study of IT-related medication errors in a pediatric hospital found that 50% of medication errors were IT related38; however, their definition of IT was broader than ours, as the authors included not only the EHR (like we did) but also medication administration technologies, such as bar-coding medication administration technology and smart infusion pump technology.

Over half of the EHR-related errors identified in this study occurred at the ordering stage and about 40% in the administration phase. Compared to non–EHR-related errors, EHR-related errors were more commonly occurring in the ordering phase and less often occurring during administration. EHR-related errors related to the CPOE functionality have received a lot of attention,39 but EHR-related errors in the administration stage have rarely been discussed. Many of these administration errors had their genesis in the ordering phase. For instance, default medication start times are much more tightly coupled to the ordering time than in previous paper-based systems; subsequently, medication doses were administered late or the first dose of a new medication was entirely omitted from administration because the medication was not available, leading to a much later first dose than intended.

Our analyses of the 4 questions used to determine EHR relatedness found that the first 2 questions (ie, similar events having been previously been reported in the literature and an EHR-related mechanism being present) explained the majority of EHR relatedness. Future research should examine whether the smaller set of 2 questions is sufficient to characterize EHR relatedness.

Recent research has focused on a deeper understanding of the concept of EHR relatedness, one that focuses on the work system’s interactions with the EHR in addition to issues related to inadequate EHR design.5,40-42 Our use of this systems approach in defining the 4 EHR-relatedness rules increases the reliability of our measure, decreasing the likelihood of events being incorrectly classified as not being EHR related. For example, in the larger study, we found that duplicate medication errors increased after EHR implementation, and contributing factors related to this increase included the EHR design as well as task-related changes during physician rounding (eg, multiple persons entering orders for the same patient at the same time) and organization-related changes in handoff communication with duplicate orders placed before and after change of shift.40 These complexities demonstrate the need for a sociotechnical systems approach such as the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model43,44 to systematically address EHR safety.45 A recent review of the literature on EHR safety,46 organized according to the SEIPS model, found factors contributing to EHR safety in each element of the work system. Future research should, therefore, expand on current efforts to identify individual contributing factors related to EHR safety42,46 and begin to also assess system interactions.

In this study, we found various characteristics and types of EHR-related error, including errors associated with design features of the EHR technology, such as poorly designed interface and data entry screen, unclear presentation of information on current medication orders, and need for double documentation (eg, clinician note and eMAR) (see Table 4). Issues with alert design are common characteristics among EHR-related errors, for example, poorly designed alerts for duplicate medication orders. We also found EHR-related errors linked to lack of fit of the technology with the rest of the sociotechnical (work) system. For instance, in Table 4, we described how medication orders with wrong start/stop time are related to lack of prescriber knowledge of specific patient circumstances. The EHR technology requires prescribers to enter medication start/stop times, but they may not have the knowledge (eg, patient scheduled for surgical procedure) to make such decisions. Therefore, they often use default start times. The technology as well as the system in which the technology is used should be designed concurrently; this is a core principle of sociotechnical systems design.47

Implementation, use, and updates of EHR technology represent systemic changes that affect all work system elements. Therefore, we need to not only design the technology appropriately (eg, usability of interface), but also evaluate the fit of the technology with the rest of the work system.48,49 We also need to develop, implement, and evaluate organizational processes aimed at identifying EHR-related safety problems after technology implementation45; this fits the human factors engineering concept of continuous adaptation and improvement of work systems.49 We actually implemented this principle as we presented preliminary results on medication errors to the participating organization; this occurred within 1 year of the EHR implementation. The organization used our data and feedback to make several changes to the design and implementation of the technology. For instance, some of the alerts were redesigned to provide better, more relevant information to the prescriber. Understanding what happens after the initial technology implementation is particularly important, as clinicians are likely to develop strategies and workarounds to deal with EHR technology limitations and problems. Identifying these strategies may provide useful information about how to redesign the technology and improve its implementation and use. Safety is an emergent property of sociotechnical (work) systems and, therefore, needs to be observed over time as people interact with and adapt to the technology.

This study has several limitations, including the fact that data were collected in a single health care organization with semiclosed ICUs, therefore limiting generalizability of results. Data were collected in 2008 on an older version of a common inpatient EHR system; this may also affect the generalizability of our results. EHR technologies by other vendors or more recent versions of implemented EHR technology may have different characteristics and safety-related issues. However, our study provides actual quantification of EHR-related medication errors, including potential harm. Our study also provides an approach to evaluate EHR-related safety that can be used in future research. Actual ADE data were excluded from this analysis, as many of the ADEs were related to hypoglycemia and its treatment; the documentation of which improved with EHR implementation, thus making it easier to identify these events. Future research could examine these complicated ADE events that actually harmed patients and further understand the role of EHR technology in contributing to patient harm.

CONCLUSION

EHR-related medication errors are frequent as they represent 34% of all medication safety events identified among 624 ICU patients. They also have the potential to cause more serious patient harm than non–EHR-related errors. The list of EHR-related medication events (see Table 3) could potentially be used by health care delivery organizations to further monitor potential patient safety problems with the implementation and use of EHR technology. The list could also be used by health IT vendors in their quality assurance efforts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is based on work supported by the American Society for Healthcare Risk Management. This research was also made possible by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), grant number R01 HS15274. This study was also supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 9U54TR000021. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or AHRQ.

Contributor Information

Pascale Carayon, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin; Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin..

Shimeng Du, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin; Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin..

Roger Brown, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin; Research Design and Statistics, University of Wisconsin School of Nursing, Madison, Wisconsin..

Randi Cartmill, Department of Surgery, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin..

Mark Johnson, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois..

Tosha B. Wetterneck, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin; Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, Wisconsin..

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Health IT and Patient Safety: Building Safer Systems for Better Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker JM, Carayon P, Leveson N, et al. EHR safety: the way forward to safe and effective systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008; 15(3):272–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menon S, Singh H, Meyer AND, Belmont E, Sittig DF. Electronic health record–related safety concerns: a cross-sectional survey. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2014;34(1):l4–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palojoki S, Pajunen T, Saranto K, Lehtonen L. Electronic health record-related safety concerns: A cross-sectional survey of electronic health record users. JMIR Med Inform. 2016;4(2):e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Joint Commission. Safe use of health information technology. Sentinel Event Alert, Issue 54. https://www.jointcommission.org/safe_health_it.aspx. Published March 31, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koppel R , Metlay JP, Cohen A , et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medications errors. JAMA. 2005;293(10): 1197–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henneman PL, Fisher DL, Henneman EA, et al. Providers do not verify patient identity during computer order entry. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(7):641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reckmann MH, Westbrook JI, Koh Y, Lo C, Day RO. Does computerized provider order entry reduce prescribing errors for hospital inpatients? A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(5):613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh H, Mani S, Espadas D, Petersen N, Franklin V, Petersen LA. Prescription errors and outcomes related to inconsistent information transmitted through computerized order entry: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10):982–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kushniruk AW, Triola MM , Borycki EM , Stein B, Kannry JL. Technology induced error and usability: the relationship between usability problems and prescription errors when using a handheld application. Int J Med Inform. 2005;74(7–8):519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez-Gonzalez CG, Herranz-Alonso A, Martin-Barbero ML, et al. Prevalence of medication administration errors in two medical units with automated prescription and dispensing. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(1):72–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nerich V, Limat S, Demarchi M, et al. Computerized physician order entry of injectable antineoplastic drugs: An epidemiologic study of prescribing medication errors. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79(10):699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eslami S, Abu-Hanna A, de Keizer NF, de Jonge E. Errors associated with applying decision support by suggesting default doses for aminoglycosides. Drug Saf. 2006;29(9):803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strom BL, Schinnar R, Aberra F, et al. Unintended effects of a computerized physician order entry nearly hard-stop alert to prevent a drug interaction: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(17):1578–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magid S, Forrer C, Shaha S. Duplicate orders: an unintended consequence of computerized provider/physician order entry (CPOE) implementation. Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(4):377–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wetterneck TB, Walker JM, Blosky MA, et al. Factors contributing to an increase in duplicate medication order errors after CPOE implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(6):774–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh KE, Adams WG, Bauchner H, et al. Medication errors related to computerized order entry for children. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):1872–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bates DW Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: implications for prevention. JAMA. 1995;274(1):29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Dykstra RH, Guappone K, Carpenter JD, Seshadri V. Categorizing the unintended sociotechnical consequences of computerized provider order entry. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(suppl 1):S21–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koppel R , Wetterneck T, Telles JL , Karsh B-T. Workarounds to barcode medication administration systems: their occurrences, causes, and threats to patient safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:408–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmieri PA, Peterson LT, Ford EW. Technological iatrogenesis: New risks force heightened management awareness. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2007;27(4):19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chuo J , Hicks RW. Computer-related medication errors in neonatal intensive care units. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35(1):119–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magrabi F, Ong MS, Runciman W, Coiera E. An analysis of computer-related patient safety incidents to inform the development of a classification. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17(6):663–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sittig DF, Singh H. Eight rights of safe electronic health record use. JAMA. 2009;302(10):1111–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magrabi F, Ong M-S, Runciman W, Coiera E. Using FDA reports to inform a classification for health information technology safety problems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(1):45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung KC, van der Veen W Bouvy ML, Wensing M, van den Bemt PM , de Smet PA. Classification of medication incidents associated with information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e63–e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Love JS, Wright A, Simon SR, et al. Are physicians’ perceptions of healthcare quality and practice satisfaction affected by errors associated with electronic health record use? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(4):610–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soran C, Simon SR, Jenter CA, et al. Do electronic health records create more errors than they prevent? AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008. November 6:1143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magrabi F, Baker M, Sinha I, et al. Clinical safety of England’s national programme for IT: a retrospective analysis of all reported safety events 2005 to 2011. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(3):198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiff GD, Amato MG, Eguale T, et al. Computerised physician order entry-related medication errors: analysis of reported errors and vulnerability testing of current systems. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24(4):264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samaranayake NR, Cheung ST, Chui WC, Cheung BM. Technology-related medication errors in a tertiary hospital: a 5-year analysis of reported medication incidents. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(12):828–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stultz JS, Nahata MC. Computerized clinical decision support for medication prescribing and utilization in pediatrics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(6):942–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naranjo CA, Busto O, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Cartmill R, et al. Medication safety in two ICUs of a community teaching hospital after EHR implementation. J Patient Saf In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carayon P Wetterneck TB, Cartmill R, et al. Characterising the complexity of medication safety using a human factors approach: an observational study in two intensive care units. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23(1):56–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cullen DJ, Sweitzer BJ , Bates DW, Burdick E , Edmondson A, Leape LL. Preventable adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: A comparative study of intensive care and general care units. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(8):1289–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Netica–Bayesian network software [computer program]. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Norsys Software Corp;2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stultz JS, Nahata MC. Preventability of voluntarily reported or trigger tool-identified medication errors in a pediatric institution by information technology: a retrospective cohort study. Drug Saf. 2015;38(7):661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slight SP, Eguale T, Amato MG, et al. The vulnerabilities of computerized physician order entry systems: a qualitative study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(2):311–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wetterneck TB, Walker JM, Blosky MA, et al. Factors contributing to an increase in duplicate medication order errors after CPOE implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(6):774–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh H, Sittig DF. Measuring and improving patient safety through health information technology: the health IT safety framework. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;0:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Castro GM, Buczkowski L, Hafner JM. The contribution of sociotechnical factors to health information technology–related sentinel events. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42(2):70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carayon P, Hundt AS, Karsh B-T, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(suppl I):i50–i58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, et al. Human factors systems approach to healthcare quality and patient safety. Appl Ergon. 2014;45(1):14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker JM. Using health IT to improve health care and patient safety. In: Carayon P, ed. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2012:305–320. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salahuddin L, Ismail Z. Classification of antecedents towards safety use of health information technology: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clegg CW. Sociotechnical principles for system design. Appl Ergon. 2000;31(5):463–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coiera E. Technology, cognition and error. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(7):417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carayon P Human factors of complex sociotechnical systems. Appl Ergon. 2006;37(4):525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]