Abstract

This study assessed the effectiveness of a 3.5-h training session for general practitioners (GPs) in providing brief stop-smoking advice and compared two methods of giving advice – ABC versus 5As – on the rates of delivery of such advice and of recommendations of evidence-based smoking cessation treatment during routine consultations.

A pragmatic, two-arm cluster randomised controlled trial was carried out including a pre-/post-design for the analyses of the primary outcome in 52 GP practices in Germany. Practices were randomised (1:1) to receive a 3.5-h training session (ABC or 5As). In total, 1937 tobacco-smoking patients, who consulted trained GPs in these practices in the 6 weeks prior to or following the training, were included. The primary outcome was patient-reported rates of GP-delivered stop-smoking advice prior to and following the training, irrespective of the training method. Secondary outcomes were patient-reported receipt of recommendation/prescription of behavioural therapy, pharmacotherapy or combination therapy for smoking cessation, and the effectiveness of ABC versus 5As regarding all outcomes.

GP-delivered stop-smoking advice increased from 13.1% (n=136 out of 1039) to 33.1% (n=297 out of 898) following the training (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 3.25, 95% CI 2.34–4.51). Recommendation/prescription rates of evidence-based treatments were low (<2%) pre-training, but had all increased after training (e.g. behavioural support: aOR 7.15, 95% CI 4.02–12.74). Delivery of stop-smoking advice increased non-significantly (p=0.08) stronger in the ABC versus 5As group (aOR 1.71, 95% CI 0.94–3.12).

A single training session in stop-smoking advice was associated with a three-fold increase in rates of advice giving and a seven-fold increase in offer of support. The ABC method may lead to higher rates of GP-delivered advice during routine consultations.

Short abstract

A brief, single training session is effective in changing GP behaviour for providing stop-smoking advice and evidence-based cessation treatment. Training according to the very brief ABC method may lead to higher rates of such GP-delivered advice. https://bit.ly/2TciPSO

Introduction

National and international guidelines [1–4] on treating tobacco addiction strongly recommend that general practitioners (GPs) should routinely give brief stop-smoking advice to every smoking patient to increase abstinence rates. Ideally, this advice is combined with an offer of evidence-based behavioural or pharmacological (nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), varenicline or bupropion) smoking cessation therapy [5, 6]. The implementation of these recommendations in German general practice is poor [7], mainly due to the lack of training of GPs on how to provide stop-smoking advice [8–12]. Such training is not part of the medical education in Germany.

Article 14 of the World Health Organization (WHO)'s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) recommends that physicians should be trained to deliver stop-smoking advice effectively [13]. Few effectiveness trials have been conducted in general practice settings [14], but these studies show positive effects of training sessions with varying durations (40 min [15, 16] to several days [17]) on the rates of delivered advice [17, 18], referrals to cessation services [15], and on GP-reported knowledge and attitude in providing of such advice [17, 19]. Only one such trial has been conducted in Germany so far [20] but it does not allow conclusions on the unique effect of the training.

Two well-known methods to provide brief stop-smoking advice are the 5As [1] (ask for the smoking status, brief advice to quit, assess the motivation to quit, assist by providing evidence-based treatment, arrange follow-up), which includes an additional brief intervention to enhance the motivation to quit (the 5Rs [1]) in unmotivated smokers, and the much briefer ABC method [21] (ask, brief advice, cessation support). So far, no studies comparing the effectiveness of these methods on GPs’ performance have been published, and no recommendation can be made to favour one method. ABC may be more convenient for GPs to apply, since it does not include discussion of the smoker's motivation to quit, as recommended with the 5As [1]. As a consequence, the last two steps of 5As are only rarely applied [22, 23], although their association with abstinence is strongest [24]. According to ABC, every smoker would receive an offer of treatment and not only those motivated to quit at the time of consultation, which only applies to a few smokers [25, 26].

We aimed to identify a stop-smoking advice approach that could be both easily and effectively adopted by GPs. We developed and pilot-tested two 3.5-h training sessions for GPs in delivering stop-smoking advice during routine consultations: one based on 5As (including the 5Rs) and one based on ABC [27]. The objective of the present study was to assess whether the brief training is effective in increasing patient-reported rates of GP-delivered stop-smoking advice (primary outcome) and the recommendation/prescription rates for evidence-based smoking cessation treatment (secondary outcomes), and to compare the effectiveness of ABC and 5As against each other. By increasing advice rates, we expected a higher number of smokers to quit or intent to quit smoking [6, 28].

Methods

Study design

We conducted a pragmatic, two-arm cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT) with a pre-/post-design for the primary outcome and cluster randomisation for the comparison of the ABC and 5As methods against each other. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee at the Heinrich-Heine-University (HHU) Düsseldorf, Germany (5999R). All participants gave written informed consent. GP practices were recruited between June 22, 2017 and March 15, 2019. The study consisted of six cycles, defined as a period of 6 weeks pre-training data collection, group training (ABC or 5As) and 6 weeks post-training data collection [27].

Participants

GP practices

Practices were recruited by postal dispatch from the online medical register of the regional Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians North Rhine of the German federal state North Rhine-Westphalia, and from the practice network of the Institute of General Practice (HHU) [27]. All GPs were eligible, except for those specialised in treating substance abuse, or those who had been trained in providing smoking cessation support within the last 5 years [27]. Many GPs in Germany provide psychosomatic or psychotherapeutic care. Their patients were only recruited following routine GP consultation, never following psychotherapeutic consultation.

Patients

Four trained researchers collected data study outcomes in tobacco-smoking patients consecutively consulting their GP, by means of questionnaire-guided, face-to-face interviews immediately following GP consultation (questionnaire: osf.io/7pmr5/, translated English version: osf.io/f2p7b/). Patients’ eligibility criteria were: ≥18 years old, cognitive and linguistic ability to provide informed consent, and meeting with their GP in person. Patients included during the pre-training data collection period were ineligible to participate during the post-training period.

Randomisation and masking

The training was delivered at the practice level. GPs had to register for at least two of the proposed training dates. Depending on how many GPs were available on these dates, two different randomisation methods were applied [27]:

≥8 GPs: computer-generated block randomisation with permuted blocks of sizes two or four, prepared by an independent statistician (WV).

<8 GPs: randomisation by virtue of the GPs temporal availability. The two dates with most registrations were selected and, in a random order between the study cycles, one was assigned to be an ABC, the other to be a 5As training.

GPs could not be fully blinded to their training allocation but did not receive information on the different training methods until the end of the pre-training data collection [27]. Patients were blinded to the purpose of the study until the end of the data collection [27]. Researchers who collected the data could not be blinded to the GPs’ group allocation, but they were not actively involved in the trainings, and were alternately assigned to the practices or depending on the travel distance between a practice and their private residence.

Procedures (intervention)

We developed and pilot-tested two standardised 3.5-h training sessions for GPs in delivering stop-smoking advice according to ABC [21] and 5As [1]. The “COM-B” behaviour change model [29] guided the design, and the Behaviour Change Techniques Taxonomy [30] was used to describe potentially active training components [27]. The process of the training development, the pilot study and the results of a process evaluation have been published together with the study protocol [27].

Training sessions were led by a senior researcher together with an experienced GP who both rotated between ABC and 5As trainings. Overall, three different researchers and four GPs served as trainers. A comprehensive training manual was used to standardise content and quality of each training. Each training session started with an introductory lecture on tobacco addiction, smoking cessation treatments and the respective method (ABC or 5As), followed by a discussion on GPs’ experience with the provision of stop-smoking advice and simulated roleplays (∼90 min) with professional actors trained in patients’ specific behaviour. GPs received handouts on the ABC/5As method, on evidence-based treatments, and a leaflet with outpatient programmes and quit smoking websites/hotlines to deliver to their patients [27].

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was defined as the number of patients prior to and following the training who report the receipt of brief stop-smoking advice during the GP consultation, irrespective of the training method, out of the total number of smoking patients who provided informed consent.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were defined as the number of smoking patients prior to and following the GP training who reported the receipt of prescription or recommendation of: individual or group behavioural counselling, NRT, varenicline or bupropion, any pharmacotherapy (NRT, varenicline or bupropion), or a combination therapy of behavioural counselling and pharmacotherapy. Moreover, we aimed to compare the effectiveness of the ABC versus 5As method regarding the primary and secondary outcomes.

Data on short-term training effects on GP-reported attitude (motivation) towards, opportunity, knowledge on and practical skills (capability) in the provision of stop-smoking advice, according to COM-B [29], were collected with a questionnaire prior to and immediately following the training.

Further secondary outcomes (e.g. quit attempts, cessation methods, abstinence) were measured at week 4, 12 and 26 following the GP consultation, but are not the subject of the present analysis.

Statistical analysis

The power calculation was informed by current rates of GP-delivered stop-smoking advice in Germany (∼18%) [7], and from projections of the pilot study [27], showing that recruitment of 48 GP practices would be feasible within 2 years. Training GPs was assumed to have a clinically relevant effect if it increases rates of advice by at least 10% (odds ratio of 1.77). A simulation study showed that a total of 16 patients per practice were needed to evaluate the primary outcome with a statistical power of at least 80%, and a total of 42 patients were needed to evaluate the interaction effect between the time (pre-/post-training) and the group variable ABC versus 5As (for which we assumed post-training percentages of 33% and 23%, respectively), resulting in a total sample size of 2016 patients (respectively 1008 prior to and 1008 following the training).

Analyses of primary and secondary outcomes

The analysis plan and statistical code had been published prior to the analyses: osf.io/36kpc/, osf.io/zurfq/. The code was written prior to the analyses and based on a blinded dataset, i.e. with the values of the outcome variables in a randomly shuffled order. Analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.1 [31].

Data were structured hierarchically in clusters (=practices), with patients within these clusters. Mixed-effects logistic regression models were used to analyse the primary outcome (received advice: yes/no), with a fixed effect for time (pre-/post-training) and random effects for the practices and the time effect. The same model was applied to the secondary outcomes. Models were adjusted for potential confounders: patients’ age, sex, level of education, time spent with, and strength of urges to smoke [32].

The group variable and its interaction with time (pre-/post-training) were added to the models as fixed effects for the ABC versus 5As comparison. The time effect and the interaction were analysed by means of Wald-type tests (level of significance 0.05).

All patients were included in an intention-to-treat analysis. Multiple imputation was used to impute missing data of potential confounders by chained equations (“mice-package” [33] with m=20 imputed datasets and 10 iterations for each dataset). Results across the imputation datasets were pooled using Rubin's rules [34]. An additional complete case analysis (sensitivity analysis) was performed for the primary outcome including the interaction effect.

Adherence to the protocol

All planned analyses are reported in the study protocol [27] and in the analysis plan. We did not adjust the analyses as planned for motivation to stop smoking since motivation was assessed following the GP consultation and might thus have been influenced by the GPs’ behaviour. Although not planned, we did not impute data for the primary outcome because missing data were very rare (four cases). Missing data of potential confounders were imputed to reduce the potential for bias compared to a complete case analysis.

Since usage of stop-smoking medication is very low in Germany [35], and combination therapy is recommended [3], two additional secondary outcomes were assessed: an aggregate variable of GP-delivered recommendations for pharmacotherapy (NRT, varenicline or bupropion) and the receipt of a combination therapy (pharmacological and behavioural).

We ran explorative subgroup analyses for the primary outcome with patient (sex, education, and number of cigarettes smoked per day) and GP data (sex, number of years in clinical practice, practice type, smoking status). Results are reported if the interaction effect (subgroup variable by exposure variable) was statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

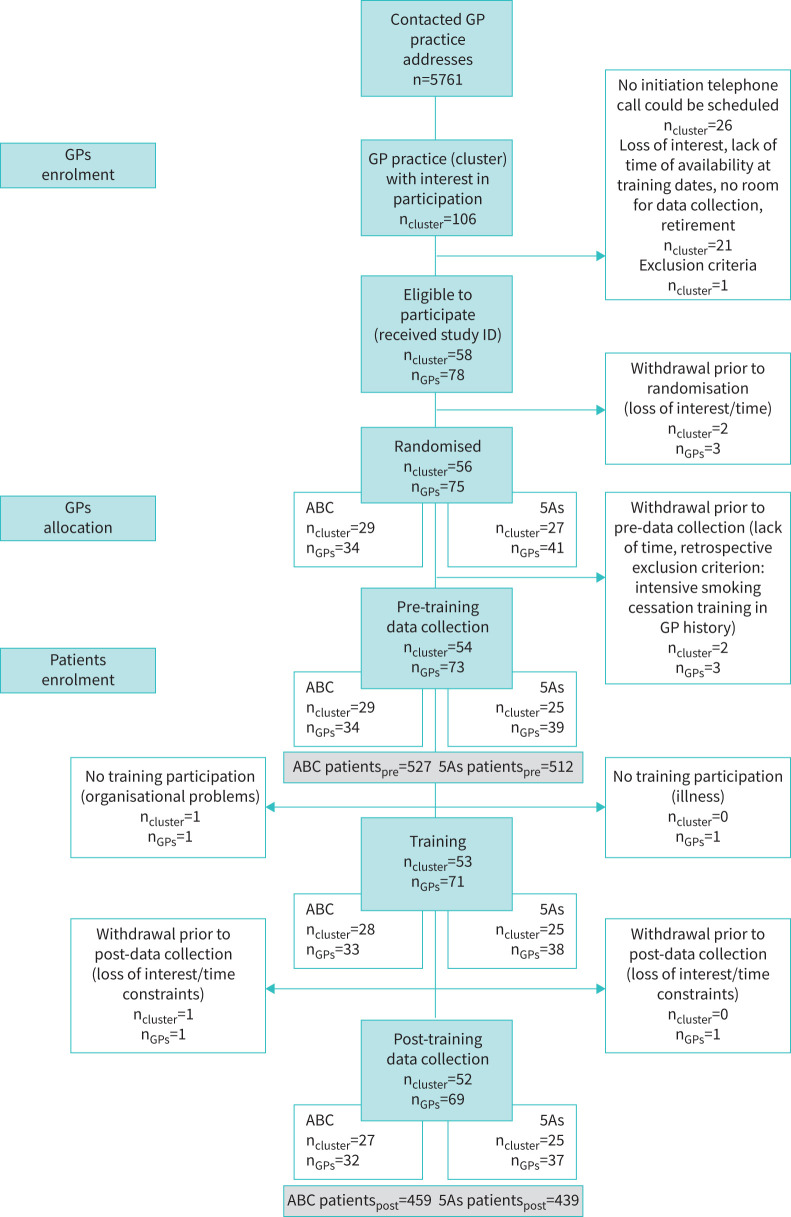

Figure 1 shows the trial flow. Fifty-eight practices with 78 GPs provided informed consent. Two practices (3 GPs) withdrew before randomisation. Fifty-six practices were randomised to either an ABC or 5As training. Following randomisation, two practices per study arm had to be excluded because the GPs were not able to participate in the training or the data collection (illness, organisational difficulties, still met an exclusion criterion) (figure 1). Hence, 52 practices (69 GPs) were included in the analyses. Table 1 presents sociodemographic and professional characteristics of these GPs.

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials chart showing trial flow of general practitioner (GP) practices (cluster) with their GPs and participating smoking patients by pre-training and post-training data collection period and by training group allocation of the GP. ID: identifier; n: number.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of general practitioners (GPs), stratified by training method (n=69 GPs from 52 practices)

| ABC training | 5As training | Total sample | |

| Subjects n | 32 | 37 | 69 |

| Age years (mean±sd) | 51.5±7.5 | 52.8±8.0 | 52.2±7.7 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 56.3 (18) | 48.7 (18) | 52.2 (36) |

| Male | 43.8 (14) | 51.4 (19) | 47.8 (33) |

| Years since becoming physician (mean±sd) | 22.6±8.0 | 23.7±9.0 | 26.1±24.2 |

| Years since established in practice (mean±sd) | 11.4±8.6 | 13.5±9.2 | 12.5±8.9 |

| Type of GP practice | |||

| Single practice | 37.5 (12) | 21.6 (8) | 29.0 (20) |

| Any type of group practice | 62.5 (20) | 78.4 (29) | 31.0 (49) |

| Area where GP practice is located | |||

| Rural area (<20 000 inhabitants) | 3.1 (1) | 5.4 (2) | 4.4 (3) |

| Small city (>20 000 inhabitants) | 3.1 (1) | 5.4 (2) | 4.4 (3) |

| City (<100 000 inhabitants) | 31.3 (10) | 13.5 (5) | 21.7 (15) |

| Large city (>100 000 inhabitants) | 62.5 (20) | 75.7 (28) | 69.6 (48) |

| Ever participated in training on delivering smoking cessation before=Yes | 25.0 (8) | 21.6 (8) | 23.2 (16) |

| Current smoking status of GP | |||

| Daily smoker | 3.1 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 1.5 (1) |

| Occasional smoker | 15.6 (5) | 5.4 (2) | 10.1 (7) |

| Ex-smoker | 21.9 (7) | 32.4 (12) | 27.5 (19) |

| Never-smoker | 59.4 (19) | 62.2 (23) | 60.9 (42) |

Data are presented as percentage (n), unless stated otherwise.

Table 2 presents sociodemographic data of all 1937 smoking patients who participated in the study: 1039 were interviewed prior to and 898 following the GP training. The latter figure was slightly lower than intended because some patients visited their GP multiple times during the study period, reducing the possibility to select unique patients.

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics of all tobacco-smoking patients, stratified by pre-/post-data collection period and by training method of the general practitioner they had consulted (n=1937)

| Pre-training | Post-training | ABC training | 5As training | Total sample | |

| Subjects n | 1039 | 898 | 986 | 951 | 1937 |

| Age years (mean±sd) | 46.1±16.1 | 46.0±15.7 | 46.2±16.0 | 45.9±15.8 | 46.1±15.9 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 52.4 (544) | 52.1 (468) | 56.0 (552) | 48.4 (460) | 52.3 (1012) |

| Male | 47.5 (493) | 47.7 (428) | 44.0 (434) | 51.2 (487) | 47.6 (921) |

| Level of education# | |||||

| High school equivalent | 21.6 (224) | 22.8 (205) | 22.4 (221) | 21.9 (208) | 22.2 (429) |

| Advanced technical college equivalent | 14.9 (155) | 13.2 (118) | 16.2 (160) | 11.9 (113) | 14.1 (273) |

| Secondary school equivalent | 29.7 (309) | 28.1 (252) | 29.3 (289) | 28.6 (272) | 29.0 (561) |

| Junior high school equivalent | 30.5 (317) | 32.3 (290) | 29.1 (287) | 33.7 (320) | 31.3 (607) |

| No qualification | 3.2 (33) | 3.6 (32) | 2.7 (27) | 4.0 (38) | 3.4 (65) |

| Cigarettes per day (mean±sd) | 14.0±9.3 | 13.6±9.4 | 13.2±9.2 | 14.5±9.4 | 13.8±9.3 |

| Time spent with urges to smoke [32]¶ (mean±sd) | 2.9±1.5 | 3.0±1.5 | 3.0±1.5 | 2.9±1.6 | 2.9±1.5 |

| Strength of urges to smoke [32]¶ (mean±sd) | 2.0±0.9 | 2.1±1.0 | 2.0±0.9 | 2.1±0.9 | 2.0±0.9 |

| Motivation to stop smoking [25] (mean±sd) | 3.3±1.8 | 3.3±1.9 | 3.4±1.8 | 3.1±1.8 | 3.3±1.8 |

| Satisfaction with conversation on smoking with GP (if so)+ | 2.0±0.9 | 2.0±0.9 | 2.0±0.9 | 2.0±0.9 | 2.0±0.9 |

Data are presented as percentage (n), unless stated otherwise. Differences when calculating the total percentage can be explained by missing data on the respective variables. #: German equivalents to education levels listed in table from highest to lowest: high school equivalent (“Allgemeine Hochschulreife”), advanced technical college equivalent (“Fachhochschulreife”), secondary school equivalent (“Realschulabschluss”), junior high school equivalent (“Hauptschulabschluss”), or no qualification. ¶: both items of the Strength of Urges to Smoke Scale (SUTS) with values ranging from 0=lowest to 6=highest urges. +: asked only in smoking patients who had a conversation on smoking with their GP (n=542) independently of whether the patient reported the receipt of one of the outcomes; satisfaction was operationalised by ratings on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1=“very satisfied” to 6=“very dissatisfied”.

Primary outcome

The patient-reported rates of GP-delivered stop-smoking advice increased from 13.1% (n=136) prior to the training to 33.1% (n=297) following the training (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 3.25, 95% CI 2.34–4.51, p<0.001) (table 3). This result remained stable when using complete case data (aOR 3.28, 95% CI 2.35–4.59), excluding patients with missing data on potential confounders (age: n=2 (0.1%), education: n=2 (0.1%), time spend with: n=118 (6.1%) and strength of urges to smoke [32]: n=122 (6.3%)).

TABLE 3.

Patient-reported receipt of brief stop-smoking advice (primary outcome) and of recommendations/prescriptions of evidence-based treatment to quit smoking (secondary outcomes) delivered by their general practitioner (GP), stratified by pre-/post-data collection period and by training method of the GP they had consulted; and associations of these outcomes with training (pre versus post) and with the interaction of training by training method (ABC/5As by pre/post) (n=1937 smoking patients)

| Outcome (patient-reported) | Pre-training | Post-training | aORimputed post versus pre (95% CI)# | aORimputed ABC versus 5As# by post versus pre (95% CI) | ||||

| PreABC | Pre5As | Pretotal | PostABC | Post5As | Posttotal | |||

| Subjects n | 527 | 512 | 1039 | 459 | 439 | 898 | ||

| Brief stop-smoking advice (primary outcome) | 11.8 (62) | 14.5 (74) | 13.1 (136) | 35.7 (164) | 30.3 (133) | 33.1 (297) | 3.25 (2.34–4.51)*** | 1.71 (0.94–3.12) |

| Behavioural counselling (individual, group) | 1.5 (8) | 1.6 (8) | 1.5 (16) | 13.3 (61) | 3.9 (17) | 8.7 (78) | 7.15 (4.02–12.74)*** | 4.59 (1.40–14.98)* |

| Nicotine replacement therapy | 0.6 (3) | 0.4 (2) | 0.5 (5) | 3.3 (15) | 7.1 (31) | 5.12 (46) | 15.45 (5.67–42.10)*** | 0.21 (0.03–1.55) |

| Varenicline or bupropion | 0 (0) | 1.4 (7) | 0.7 (7) | 3.1 (14) | 1.6 (7) | 2.3 (21) | 3.10 (1.27–7.53)*** | ¶ |

| Any pharmacotherapy | 0.6 (3) | 1.8 (9) | 1.2 (12) | 6.3 (29) | 8.7 (38) | 7.5 (67) | 7.99 (4.11–15.52)*** | 1.81 (0.42–7.78) |

| Combination of behavioural counselling and pharmacotherapy | 1.9 (10) | 1.8 (9) | 1.8 (19) | 7.6 (35) | 5.2 (23) | 6.5 (58) | 4.36 (2.46–7.73)*** | 1.42 (0.45–4.44) |

Data are presented as percentage (n), unless stated otherwise. Data are presented as adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) around aOR. #: logistic regression models with a fixed effect for time (pre- versus post-training) and random effects for the practices and the time effect, for the ABC versus 5As comparison: the group variable (5As or ABC training) and its interaction with time were added to the models as fixed effects; both models were adjusted for patients’ sex, age, level of education, time spent with urges to smoke and strength of urges to smoke (SUTS [32]). ¶: model could not be fitted due to perfect separation (prior to the training, no (0%) such recommendation was ever provided in the ABC group, increasing to 3.1% after the training, while the pre- and post-training percentages remained relatively stable at 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively, in the 5As group). *: p<0.05; ***: p<0.001.

Secondary outcomes

Patient-reported rates of GP-delivered recommendation/prescription of evidence-based smoking cessation treatment were low prior to the training (<2%) but increased significantly for all types of treatment after the training, including the combination of behavioural counselling and pharmacotherapy (table 3).

A higher post-training increase in the rates of delivered stop-smoking advice was observed in GPs trained according to the ABC versus the 5As method (aOR 1.71, 95% CI 0.94–3.12), although not statistically significant (p=0.08) (table 3). This result remained stable when using complete case patient data (aOR 1.69, 95% CI 0.91–3.12). The increase of GP-delivered recommendations/prescriptions for behavioural support following the training was significantly higher in the ABC versus 5As group. No such difference could be observed regarding the recommendation/prescription rates of stop-smoking medication or for the combination therapy (table 3).

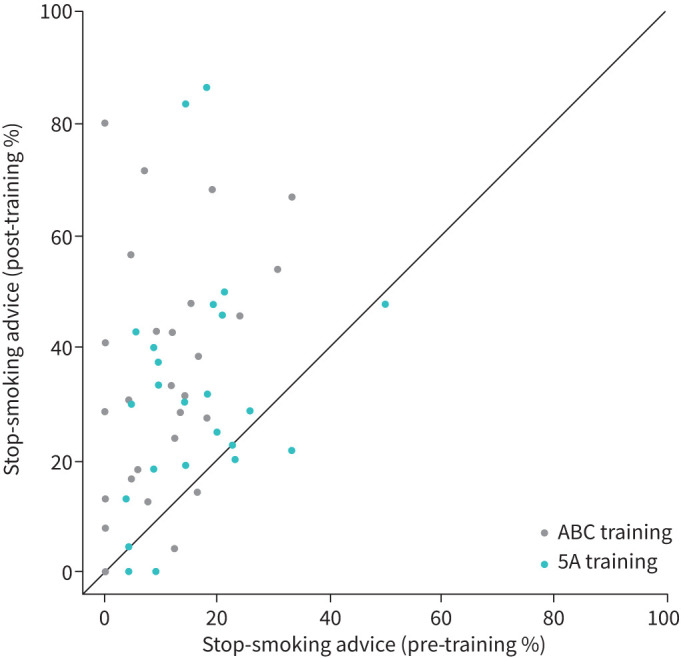

A scatter plot (figure 2) shows the association between the percentages of patients who reported the receipt of stop-smoking advice prior to and following the training by group allocation of the GP.

FIGURE 2.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between the percentages of patients who reported the receipt of stop-smoking advice delivered by their general practitioner (GP) prior to the training (x-axis) and following the training (y-axis) by training group allocation of the GP.

Subgroup analyses

Explorative subgroup analyses for the primary outcome showed a higher increase (from 11.3% to 36.1%) of GP-delivered stop-smoking advice following the training in patients who had visited a GP with less working experience (below group median number of years (≤12 years), OR 4.63, 95% CI 2.93–7.33) compared to those who had visited a GP with more working experience (above group median (>12 years), from 15.0% to 30.3%, OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.49–3.64). The mean difference between both groups prior to the training was not statistically significant (z-score: 1.388; p=0.165).

GP-reported training effects

GP-reported capability (knowledge and practical skills) and opportunity in the provision of stop-smoking advice significantly improved following the training (all effect sizes between 0.58 and 2.84, supplementary table S1). No such effect was observed for attitude (motivation), which was already high prior to the training. Following the training, 91% (n=63) of the GPs agreed to implement stop-smoking advice more frequently in their daily practice, and the majority (78%, n=55) estimated their learning growth to be high or very high (supplementary table S2).

Discussion

In this cRCT, GPs’ participation in a 3.5-h training session in giving brief stop-smoking advice according to the ABC or 5As method was associated with a patient-reported three-fold increase of advice-giving and a seven-fold increase in offer of support. The increase of delivered advice was non-significantly higher in GPs trained according to ABC compared to 5As. Although the effects of the training on quit attempts and success rates in patients still need to be explored, evidence is strong that physician advice on smoking cessation significantly increases the rates of quitting [28].

Strengths of this study include its “real-life” setting, the face-to-face data collection with low risk for missing data and recall bias, and that data were assessed by means of patient reports, because memory for medical information is important for adherence to recommended treatment [36]. All analyses were planned and published in advance, and the statistical code was written on a dataset blinded for study arms and pre–post allocation.

Until now, only few studies assessed the effectiveness of training GPs on their performance to deliver stop-smoking advice. Verbiest et al. [18] showed that a 1-h 5As group training session increased the GP, but not the patient-reported delivery rates of such advice, and no effect was observed regarding the provision of pharmacotherapy. Only the pilot study of Girvalaki et al. [17] used a behaviour change theory to guide the intervention design, as we did in the present study, and found a full-day group training with two refresher trainings to be effective in increasing patient- and GP-reported advice rates and prescriptions of medication. However, the analyses were not adjusted for relevant patient characteristics, and training duration may lower the GPs’ motivation to participate. The studies of Unrod [16] and McRobbie et al. [15] showed that even a 4- min individual or group 5As training session might be effective in improving GPs’ implementation of the 5As [16]. These studies did not analyse prescriptions of smoking cessation treatment but referral rates to cessation services [15, 16]. In Germany, clinics providing behavioural therapy are rare, and specialists’ cessation services [37] do not exist, which is why GPs play a central role in initiating effective treatment.

This study is the first comparing the effectiveness of a training session in the ABC versus 5As method on GPs’ delivery of stop-smoking advice. Higher rates of recommended or prescribed behavioural support were observed in the ABC group. Apart from the introduction of the respective method, the training sessions were standardised. It can thus be hypothesised that GPs from the ABC group more often deliver “cessation support”. This effect was not observed for pharmacotherapy, probably because costs for pharmacotherapy are not reimbursed by health insurance schemes in Germany, whereas costs for behavioural support are at least partly reimbursed (50–75%). In addition, the situation in Germany is unusual in that GPs are generally rather unwilling to recommend stop-smoking medication. Worries about the side-effects or the lack of skills to inform smokers on the need and effectiveness of cessation medication could have also affected the tendency to prescribe behavioural support over pharmacotherapy. This might not have been adequately addressed by the training.

Limitations

A major limitation of the study is that only short-term intervention effects were studied. Second, trial practices may not be representative for all GP practices across Germany, although North Rhine-Westphalia is the most populous German state, with a broad socioeconomic variability, and practices were located in urban and rural areas. Third, observation of GP consultations was not feasible, thus it remains unclear whether GPs had effectively implemented the respective method. Fourth, it was not possible to fully blind the researchers who conducted the data collection, since GPs talked to them about the training they participated in. Strategies were applied to reduce contamination [27]. Fifth, we did not control analyses for smokers’ motivation to quit. Those highly motivated might have initiated a conversation on smoking cessation with the GP. However, the risk for such bias is assumed to be equally distributed between pre- and post-training data assessment and between the training groups. Sixth, previous smoking cessation training within the last 5 years was an exclusion criterion for GPs. However, it might be possible that self-reports of some GPs on that were influenced by a recall bias. Finally, our study was not designed to compare the effectiveness of both training methods directly but indirectly through training. A direct comparison could only be done if the methods are implemented 1:1 in a (non-pragmatic, rather artificial) study of perfectly trained GPs, which was not our approach.

Conclusions and policy implications

Our theory-based, 3.5-h training session offers a highly effective strategy to improve the delivery of evidence-based stop-smoking advice in general practice. Training according to ABC may lead to higher GP-delivered rates of such advice during routine consultations. This procedure may require more intense knowledge on the effectiveness of evidence-based cessation treatment, and skills on how to initiate such treatment. Efforts should be made to educate physicians on these simple counselling methods early on during professional training, and policy makers should be encouraged to implement the FCTC recommendations regarding the provision of counselling opportunities for smokers.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

TABLE S1 Changes in capability, opportunity and motivation to deliver brief stop-smoking advice to smoking patients from prior to following the training reported by 69 general practitioners (GPs) of 52 GP practices. 00621-2020.tableS1 (76KB, pdf)

TABLE S2 Relevance of the training content and learning curve reported by general practitioners (GPs) directly following the training (N=69 GPs from 52 practices). 00621-2020.tableS2 (11.7KB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all trial patients and general practitioners. In particular, we thank our general practitioner peer trainers at the Institute of General Practice of the HHU Duesseldorf who were intensively involved in the development and provision of the training: Olaf Reddemann, Inken Blank, Detlef Maurer and Elisabeth Gummersbach. We also thank our student assistants who contributed to the data entry and follow-up data collection: Esther Scholz, Sarah Fullenkamp and Laura Schrobildgen. Stefanie Otten, trainer of the standardised patients, and her team (Brigitte Keldenich-Bergstein, Michael Hoch and Georg Hoeren) are thanked for their professional and motivated assistance with the roleplays in preparation of and during the training.

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com.

This study is registered at www.drks.de with identifier number DRKS00012786. The data underlying this study are third-party data (de-identified participant data) and are available to researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author (sabrina.kastaun@med.uni-duesseldorf.de). All proposals requesting data access will need to specify how it is planned to use the data, and all proposals will need approval of the trial investigator team before data release. The study protocol, the statistical analysis plan and code have been published at the Open Science Framework (osf.io/36kpc/, osf.io/zurfq/).

Participant consent for publication: All participants (patients and GPs) gave written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the medical ethics committee at the Heinrich-Heine-University (HHU) Düsseldorf, Germany (5999R).

Author contributions: D. Kotz conceived the study and acquired funding for the current study together with S. Kastaun and V. Leve, and co-wrote this manuscript. S. Kastaun, V. Leve and D. Kotz developed and conducted the general practitioner training. S. Kastaun coordinated all study processes and wrote the first draft of the current manuscript. W. Viechtbauer, statistician, conducted a simulation study for the sample size calculation of the study and prepared the randomisation sequence. He also prepared the statistical analysis code, and advised on statistical analysis plans together with D. Kotz and S. Kastaun, who conducted all analyses and interpreted the data. J. Hildebrandt, D. Lubisch, S. Klosterhalfen and C. Funke were significantly involved in all study processes including recruitment, data collection, data entry and cleaning. O. Reddemann, general practitioner and peer trainer, was mainly involved in the final evaluation of the training manual and the didactic methods. S. Wilm, R. West, T. Raupach and H. McRobbie gave valuable feedback at the time of designing the trial, and commented on and added to the present manuscript. All named authors contributed substantially to the manuscript and agreed on its final version. S. Kastaun and D. Kotz are the guarantors. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Conflict of interest: S. Kastaun has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: V. Leve has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Hildebrandt has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Funke has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Klosterhalfen has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Lubisch has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: O. Reddemann has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H. McRobbie reports honoraria for speaking at smoking cessation meetings and attending advisory board meetings from Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: T. Raupach reports personal fees from Pfizer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca and Roche as a speaker in activities related to continuing medical education, and grants from Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: R. West reports grants and personal fees from Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson and GlaxoSmithKline, and personal fees from acting as an advisor to the UK's National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: S. Wilm has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: W. Viechtbauer has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Kotz has nothing to disclose.

Support statement: The study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health (grant number ZMVI1-2516DSM221, Daniel Kotz). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. . A Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update – A US Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med 2008; 35: 158–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) . Smoking: acute, maternity and mental health services, Guidance PH48. 2013. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph48 Date last accessed: 17 June, 2020.

- 3.Association of the Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) [Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF)] . S3 Guideline “Screening, Diagnostics, and Treatment of Harmful and Addictive Tobacco Use” [S3-Leitlinie “Screening, Diagnostik und Behandlung des schädlichen und abhängigen Tabakkonsums”]. AWMF-Register Nr. 076-006 2015. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/076-006.html Date last accessed: 7 June, 2020.

- 4.Van Schayck OCP, Williams S, Barchilon V, et al. . Treating tobacco dependence: guidance for primary care on life-saving interventions. Position statement of the IPCRG. NPJ Prim Care Respir 2017; 27: 38. doi: 10.1038/s41533-017-0039-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, et al. . Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 10: CD008286. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartmann-Boyce J, Hong B, Livingstone-Banks J, et al. . Additional behavioural support as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; 6: CD009670. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009670.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kastaun S, Kotz D. Brief medical advice on smoking cessation – Results of the DEBRA study [Ärztliche Kurzberatung zur Tabakentwöhnung – Ergebnisse der DEBRA Studie]. Journal of Addiction Research and Practice [SUCHT] 2019; 65: 34–41. doi: 10.1024/0939-5911/a000574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strobel L, Schneider NK, Krampe H, et al. . German medical students lack knowledge of how to treat smoking and problem drinking. Addiction 2012; 107: 1878–1882. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03907.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Twardella D, Brenner H. Lack of training as a central barrier to the promotion of smoking cessation: a survey among general practitioners in Germany. Eur J Public Health 2005; 15: 140–145. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoch E, Franke A, Sonntag H, et al. . Smoking cessation in primary medical care - chance or fiction? Results of the “Smoking and Nicotine Dependence Awareness and Screening (SNICAS)” study [Raucherentwöhnung in der primärärztlichen Versorgung – Chance oder Fiktion? Ergebnisse der “Smoking and Nicotine Dependence Awareness and Screening (SNICAS)”-Studie]. Addiction Medicine in Research and Practice [Suchtmedizin in Forschung und Praxis] 2004; 6: 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raupach T, Merker J, Hasenfuss G, et al. . Knowledge gaps about smoking cessation in hospitalized patients and their doctors. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2011; 18: 334–341. doi: 10.1177/1741826710389370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancer Research UK . Smoking Cessation in Primary Care: A cross-sectional survey of primary care health practitioners in the UK and the use of Very Brief Advice. 2019. www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/tobacco_pc_report_to_publish_-_full12.pdf Date last accessed: 2 June 2020.

- 13.Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Article 14 Guidelines. 2010. www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/adopted/article_14/en/ Date last accessed: 28 June 2020.

- 14.Carson KV, Verbiest MEA, Crone MR, et al. . Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 5: CD000214. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000214.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McRobbie H, Hajek P, Feder G, et al. . A cluster-randomised controlled trial of a brief training session to facilitate general practitioner referral to smoking cessation treatment. Tob Control 2008; 17: 173–176. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.024802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unrod M, Smith M, Spring B, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of a computer-based, tailored intervention to increase smoking cessation counseling by primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22: 478–484. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0069-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girvalaki C, Papadakis S, Vardavas C, et al. . Training general practitioners in evidence-based tobacco treatment: an evaluation of the Tobacco Treatment Training Network in Crete (TiTAN-Crete) Intervention. Health Educ Behav 2018; 45: 888–897. doi: 10.1177/1090198118775481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verbiest ME, Crone MR, Scharloo M, et al. . One-hour training for general practitioners in reducing the implementation gap of smoking cessation care: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res 2014; 16: 1–10. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bobak A, Raupach T. Effect of a short smoking cessation training session on smoking cessation behaviour and its determinants among GP trainees in England. Nicotine Tob Res 2017; 20: 1525–1528. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twardella D, Brenner H. Effects of practitioner education, practitioner payment and reimbursement of patients’ drug costs on smoking cessation in primary care: a cluster randomised trial. Tob Control 2007; 16: 15–21. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.016253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health . The New Zealand Guidelines for Helping People to Stop Smoking. 2014. www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-zealand-guidelines-helping-people-stop-smoking Date last accessed: 6 June 2020.

- 22.Martinez C, Castellano Y, Andres A, et al. . Factors associated with implementation of the 5A's smoking cessation model. Tob Induc Dis 2017; 15: 41. doi: 10.1186/s12971-017-0146-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartsch AL, Harter M, Niedrich J, et al. . A systematic literature review of self-reported smoking cessation counseling by primary care physicians. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0168482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park ER, Gareen IF, Japuntich S, et al. . Primary care provider-delivered smoking cessation interventions and smoking cessation among participants in the national lung screening trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175: 1509–1516. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotz D, Brown J, West R. Predictive validity of the Motivation To Stop Scale (MTSS): a single-item measure of motivation to stop smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013; 128: 15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hummel K, Brown J, Willemsen MC, et al. . External validation of the Motivation To Stop Scale (MTSS): findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Netherlands Survey. Eur J Public Health 2017; 27: 129–134. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kastaun S, Leve V, Hildebrandt J, et al. . Effectiveness of training general practitioners to improve the implementation of brief stop-smoking advice in German primary care: study protocol of a pragmatic, 2-arm cluster randomised controlled trial (the ABCII trial). BMC Fam Prac 2019; 20: 107. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-0986-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, et al. . Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 2013: CD000165. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011; 6: 42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. . The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behavl Med 2013; 46: 81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Foundation for Statistical Computing . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 3.6.1 version. Vienna, Austria, R Core Team, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fidler JA, Shahab L, West R. Strength of urges to smoke as a measure of severity of cigarette dependence: comparison with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and its components. Addiction 2011; 106: 631–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Buuren S. Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011; 45: 1–67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotz D, Batra A, Kastaun S. Smoking cessation attempts and common strategies employed. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2020; 117: 7–13. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessels RPC. Patients’ memory for medical information. J R Soc Med 2003; 96: 219–222. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.5.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray RL, McNeill A. Reducing the social gradient in smoking: initiatives in the United Kingdom. Drug Alcohol Rev 2012; 31: 693–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00447.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

TABLE S1 Changes in capability, opportunity and motivation to deliver brief stop-smoking advice to smoking patients from prior to following the training reported by 69 general practitioners (GPs) of 52 GP practices. 00621-2020.tableS1 (76KB, pdf)

TABLE S2 Relevance of the training content and learning curve reported by general practitioners (GPs) directly following the training (N=69 GPs from 52 practices). 00621-2020.tableS2 (11.7KB, pdf)