Abstract

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a collagenosis characterized by excessive deposition of collagen in the skin and viscera, in a background of immune disorder. The immunological profile of SSc often shows elevated levels of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs). However, many authors have identified cases of SSc having normal ANA levels, framed as paraneoplastic SSc. Among patients with negative ANAs in our group, we did not identify any neoplastic process that could support this hypothesis. The extended detection of autoantibodies is extremely useful in establishing the subset of SSc. Thus, anti-Scl70 antibodies are specific for the diffuse subset of SSc, while anticentromere antibodies (ACAs) have specificity for a limited subset. However, studies have shown the existence of cases of diffuse SSc having high titers of ACAs and cases of limited SSc with high titers of anti-Scl70 antibodies. This indicates an inconsistent association between the disease subset and the autoantibodies specific to each subset. Our study found a more balanced consistency between disease subsets and autoantibodies specific for each subset. Therefore, the percentages of patients having an immunological profile inconsistent with the subset of SSc, are lower than those found by other authors. This observation opens the perspective of larger studies on the immunological profile in SSc.

Keywords: systemic sclerosis, antinuclear antibodies, immunological profile, anti-Scl70, anticentromere, paraneoplastic

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a connective tissue disease manifested through an altered microvascularization which is then followed by cutaneous and visceral fibrosis, in the context of autoimmune alteration (1). The etiopathogenesis of this autoimmune disease burdened by skin damage and a high degree of viscera involvement is yet insufficiently known (2-9). Despite numerous studies, the therapeutic management remains unsatisfactory (6,9-17).

Jacobsen et al highlight the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) in 86% of the patients diagnosed with SSc (18). Fabri and Hunzelmann reported positive ANAs in a higher number of patients, more specifically 90% (19). In a review, Haustein revealed that 85% of SSc cases had a positive immunological profile, and a dynamic autoimmune evaluation identified the presence of autoantibodies in up to 98% of patients with SSc (1). In another study, Steen et al identified negativity for ANAs in 53% of the enrolled patients (20). Normal ANA titers do not rule out the disease's presence (1,21). Monfort et al (22,23) and other authors (24-26) identified an association between the cases of SSc with normal levels of ANAs and neoplastic pathology in their studies in recent years (22-26). Consequently, they consider SSc cases presenting with normal ANA levels as paraneoplastic SSc (22,23). Depending on the extent of the skin involvement, there are two subsets of SSc: Limited and diffuse (27). Each of the two subsets of this disease has a characteristic immunological profile. Thus, anticentromere antibodies (ACAs) are known to be characteristic of the limited SSc subset and anti-Scl70 antibodies have specificity for diffuse SSc (1). Anti-Scl70 antibodies are present in diffuse SSc and are associated with an increased risk for interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, without having increased renal involvement, a trait which is found in other immunological models (19). Statistics have shown that these autoantibodies are more common in Japanese and Thai patients and less likely in the African-American population (19). The presence of ACAs is associated with a better prognosis and with higher survival rates, by also taking into account the lower risk of impaired lung and kidney function; this is in direct opposition to the presence of anti-Scl70 antibodies that aggravate the prognosis (19). Each of these types of autoantibodies can be found only singularly, and not in combination (1). Haustein notes that ACAs and anti-Scl70 antibodies are useful predictors for the two subsets of SSc and directs the diagnosis to a specific subset from an early stage (1). However, in a study conducted by the University of Pittsburgh on a group of 397 patients, Steen and colleagues found normal ACA titers in 57% of patients with limited SSc and elevated titers of anti-Scl70 antibodies in only 33% of patients with diffuse SSc (20). These observations indicate an inconsistent correlation between the immunological profile and the SSc subset (28).

Patients and methods

We conducted an observational study on a group of 37 patients diagnosed with SSc according to the criteria developed and reviewed in 2013 by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) (29).

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Medical University of Iași (24.06.2017), as well as from the Ethics Council of the ‘Sf. Maria’ Clinical Hospital in Bucharest (5213/04.04.2019). Patients were hospitalized between February 2019 and March 2020, in the Internal Medicine and Rheumatology Departments of the ‘Sf. Maria’ Clinical Hospital in Bucharest, Romania.

We appreciated the extension of skin induration, as being limited to the hands, face and feet or extended to the trunk and abdomen (30), according to the Le Roy criteria; a characteristic on which the patients were placed into SSc subsets: Limited and diffuse forms (30). Blood samples were obtained for autoantibody detection after each patient signed an informed consent. Correlations were made between the autoantibody profile and the limited and diffuse SSc clinical type. The enrolled patients were evaluated clinically, biologically and with imaging studies in order to identify the existence of a possible neoplasm. All of the procedures in this study were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The results were introduced in an Excel file with statistical analysis processing, followed by the use of Microsoft Excel, SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp.). The results were presented as a table. The quantitative data were characterized through descriptive statistics; the qualitative data were characterized through frequency distributions and contingency tables, and comparisons between samples were made using the Chi-squared test. All P-values were two-tailed; a P-value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

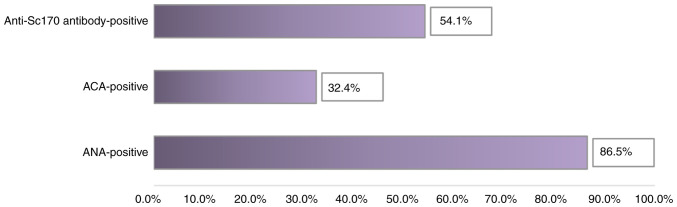

We conducted an observational study on a group of 37 patients with SSc from the southeastern region of Romania. Following the analysis of the immune profile, we observed that most patients diagnosed with SSc (86.5% of them) had elevated ANA levels. Of these, the majority (54.1%) had high titers of anti-Scl70 antibodies specific to diffuse SSc (Table I and Fig. 1).

Table I.

The immunological profile of SSc: Frequency distributions of the total group and by subsets.

| SSc limited | SSc diffuse | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased autoantibodies | n | % | n | % | n | % | Chi-square | P-value |

| ANAs | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 7.1 | 4 | 17.4 | 5 | 13.5 | 0.782 | 0.362 (NS) |

| Yes | 13 | 92.9 | 19 | 82.6 | 32 | 86.5 | ||

| ACAs | ||||||||

| No | 4 | 28.6 | 21 | 91.3 | 25 | 67.6 | 15.629 | 0.000 (SS) |

| Yes | 10 | 71.4 | 2 | 8.7 | 12 | 32.4 | ||

| Anti-Scl70 antibodies | ||||||||

| No | 11 | 78.6 | 6 | 26.1 | 17 | 45.9 | 9.653 | 0.002 (SS) |

| Yes | 3 | 21.4 | 17 | 73.9 | 20 | 54.1 | ||

| Total | 14 | 100.0 | 23 | 100.0 | 37 | 100.0 | ||

SSc, systemic sclerosis; ANAs, antinuclear antibodies; ACAs, anticentromere antibodies. NS, not significant; SS, statistically significant (in bold print).

Figure 1.

Autoantibodies: Frequency distributions for the total group of SSc patients. SSc, systemic sclerosis; ANA, antinuclear antibody; ACA, anticentromere antibody.

The distribution of SSc cases with positive ANAs did not register significant differences between the diffuse and limited subset of SSc. Therefore, the percentage of patients with limited SSc who had positive ANAs (92.9%) was slightly higher than that of the patients with diffuse SSc with only 82.6%. Relative to the entire group, we noted that almost 2/3 of the patients with positive ANA levels were part of the subset with diffuse SSc. Of the patients with normal ANA titers, the majority (17.4%) were from the diffuse subset of SSc (Table I). This result suggests that the proportion of patients without elevations in the ANA titer is low and is more common in the diffuse subset of SSc.

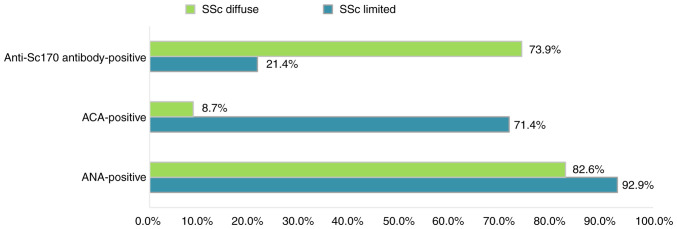

ACAs, known to be specific for the limited type of SSc (1), were identified in 32.4% of the patients from the investigated group. Of these, most patients (71.4%) belonged to the limited subset. Within the subgroup with limited SSc, increased ACA titers were present in a significant percentage of patients (71.4%). Contrary to expectations, more than 1/4 of the patients from the subset with limited SSc had normal ACA titers (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Autoantibodies: Frequency distributions by subset of SSc. SSc, systemic sclerosis; ANA, antinuclear antibody; ACA, anticentromere antibody.

Anti-Scl70 antibodies that are specific for the diffuse forms of SSc (1) were found in 54.1% of patients in the entire analyzed group, and in 73.9% of patients with diffuse SSc. We noted that a fairly large share (26.1%) of patients with diffuse SSc did not show increases in anti-Scl70 antibodies. Surprisingly, in the subgroup of patients with limited SSc, several isolated cases with anti-Scl70-positive antibodies were identified. Similar observations were made by Steen et al (20) but our study identified smaller discrepancies between the subset of SSc and the autoantibodies specific to each subset, as compared to Steen et al American study which enrolled a very large number of patients with SSc (20).

Discussion

Following the patient group analysis from the south-eastern region of Romania, most of the SSc patients enrolled in this study had high ANA titers; however a low percentage of SSc cases with normal ANA values was also identified, suggesting that a normal ANA titer does not rule out presence of the disease. Our results are similar to those of other authors who revealed the existence of a small percentage of SSc cases with normal ANA levels (12-14). Haustein also observed ANA positivity during the course of the disease in a large group of patients in an American clinic. At the start of the study, ANAs were positive in 85% of the enrolled patients and in dynamics, ANA tested positive in up to 96% of the patients studied (1). Starting from Haustein's observation of ANA positivization following disease progression in a patient with present SSc criteria, it can be stated that the immunological profile could be negative in the early stages of immunopathy.

Given the results of our study and by analyzing the results of other authors, it can be appreciated that the immunological profile of SSc is not always associated with the extent of skin damage reflected by the subset of SSc, as noted by Steen et al (20). This finding suggests the need to study the levels of ANAs during the disease progression in order to discover a possible increase. Monfort and his collaborators classified ScS with normal ANA titers as cases of paraneoplastic SSc (22,23). Among patients with negative ANA in our group, we did not identify any neoplastic process that could support this hypothesis. Referring to the type of ANA identified, the present study recorded high levels of ACAs in almost 3/4 of patients with limited SSc, but we also identified some limited SSc with elevated titers of anti-Scl70 antibodies, with the knowledge that these autoantibodies are characteristic of diffuse SSc (1). Similarly, in the subset of patients diagnosed with diffuse SSc, 3/4 of them had high titers of anti-Scl70 antibodies, while a small number of cases had elevated ACA levels, which are known to be characteristic of the limited SSc subset (1).

As a peculiarity of our study, the percentage of patients having an immunological profile inconsistent with the subset of SSc, was lower than that found by other authors (12). Thus, only a few isolated cases of patients with diffuse SSc showed positive ACAs and cases of limited SSc with positive anti-Scl70 antibodies were also reported as isolated cases. Therefore, our study found a more balanced consistency between the disease subset and the autoantibodies specific for each subset.

In conclusion, the necessity for other studies regarding SSc cases with negative ANAs and on subsets of SSc with an atypical immunological profile remains high.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The analyzed data sets generated during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

CB, EN, AIH, MLD and MC were involved in the conception of the study and had major contribution in the writing and revising of the manuscript. LGS, IAP, CO, SC and ML assisted in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committees of the Medical University of Iași (24.06.2017) and of the Ethics Council of the Clinical Hospital ‘St. Maria’ in Bucharest (5213/04.04.2019) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided informed consent and approved the publication of data.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Haustein UF. Systemic sclerosis-scleroderma. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juche A, Siegert E, Mueller-Ladner U, Riemekesten G, Günther C, Kötter I, Henes J, Blank N, Voll RE, Ehrchen J, et al. Reality of inpatient vasoactive treatment with prostacyclin derivatives in patients with acral circulation disorders due to systemic sclerosis in Germany. Z Rheumatol. 2020;79:1057–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00393-019-00743-9. (In German) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bobeica C, Niculet E, Craescu M, Halip AI, Popescu IA, Draganescu ML, Onisor C, Stefanescu B, Gheuca-Solovastru L. Etiological factors of systemic sclerosis in the southeast region of Romania. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21(79) doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gheorghe I, Tatu AL, Lupu I, Thamer O, Cotar AI, Pircalabioru GG, Popa M, Cristea VC, Lazar V, Chifiriuc MC. Molecular characterization of virulence and resistance features in Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains isolated from cutaneous lesions in patients with drug adverse reactions. Rom Biotechnol Lett. 2017;22:12321–12327. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tatu AL, Cristea VC. Unilateral blepharitis with fine follicular scaling. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21(442) doi: 10.1177/1203475417711124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horodinschi RN, Stanescu AMA, Bratu OG, Pantea Stoian A, Radavoi DG, Diaconu CC. Treatment with statines in elderly patients. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55(721) doi: 10.3390/medicina55110721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatu AL, Nwabudike LC. Reply to: Kubiak K et al. Endosymbiosis and its significance in dermatology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e346–e347. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gheorghe G, Toth PP, Bungau S, Behl T, Ilie M, Pantea Stoian A, Bratu OG, Bacalbasa N, Rus M, Diaconu CC. Cardiovascular risk and statin therapy considerations in women. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10(483) doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10070483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bobeică C, Tatu AL, Crăescu M, Solovăstru L. Dinamics of digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20:61–67. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazilu L, Stanculescu DL, Gheorghe AD, Suceveanu AP, Parepa IR, Stoian AP, Pop CS, Bratu O, Suceveanu AI. Chemotherapy and other factors affecting quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Rev Chim. 2019;70:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nwabudike LC, Tatu AL. Magistral prescription with silver nitrate and peru balsam in difficult-to-heal diabetic foot ulcers. Am J Ther. 2018;25:e679–e680. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tatu AL, Clatici VG, Nwabudike LC. Rosacea-like demodicosis (but not primary demodicosis) and papulopustular rosacea may be two phenotypes of the same disease-a microbioma, therapeutic and diagnostic tools perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:e46–e47. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crismaru I, Pantea Stoian A, Bratu OG, Gaman MA, Stanescu AMA, Bacalbasa N, Diaconu CC. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering treatment: The current approach. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19(85) doi: 10.1186/s12944-020-01275-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tatu AL, Elisei AM, Chioncel V, Miulescu M, Nwabudike LC. Immunologic adverse reactions of β-blockers and the skin. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:955–959. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buzia OD, Fasie V, Mardare N, Diaconu C, Gurau G, Tatu AL. Formulation, preparation, physico-chimical analysis, microbiological peculiarities and therapeutic challenges of extractive solution of Kombucha. Rev Chim. 2018;69:720–724. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatu AL, Ionescu MA, Nwabudike LC. Contact allergy to topical mometasone furoate confirmed by rechallenge and patch test. Am J Ther. 2018;25:e497–e498. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nwabudike LC, Miulescu M, Tatu AL. Case series of an alternative therapy for generalised lichen planus: Four case studies. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:943–948. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobsen S, Halberg P, Ullman S, Van Venrooij WJ, Høier-Madsen M, Wiik A, Petersen J. Clinical features and serum antinuclear antibodies in 230 Danish patients with systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:39–45. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabri M, Hunzelmann N. Differential diagnosis of scleroderma and pseudoscleroderma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:977–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06311.x. (In English, German) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steen VD, Powell DL, Medsger TA Jr. Clinical correlations and prognosis based on serum autoantibodies in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:196–203. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bobeica C, Niculet E, Craescu M, Onisor C, Bujoreanu F, Draganescu ML, Halip IA, Gheuca-Solovastru L. Epidemiological profile of systemic sclerosis in the southeast region of Romania. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21(77) doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monfort JB, Mathian A, Amoura Z, Francès C, Barbaud A, Senet P. Cancers associated with systemic sclerosis involving anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2018;145:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2017.08.005. (In French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monfort JB, Lazareth I, Priollet P. Paraneoplastic systemic sclerosis: About 3 cases and review of literature. J Mal Vasc. 2016;41:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jmv.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nwabudike LC, Tatu AL. Response to-chronic exposure to tetracyclines and subsequent diagnosis for non-melanoma skin cancer in a large Mid-Western US population. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(e159) doi: 10.1111/jdv.14657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tatu AL, Nwabudike LC. The treatment options of male genital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus short title for a running head: Treatments of genital lichen sclerosus conference: 14th National Congress of Urogynecology (Urogyn) Location: Eforie, Romania Date: SEP 07-09, 2017. Proceedings of the 14th National Congress of Urogynecology and the National Conference of the Romania Association for the Study of Pain, pp262-264, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nwabudike LC, Elisei AM, Buzia OD, Miulescu M, Tatu AL. Statins. A review on structural perspectives, adverse reactions and relations with son-melanoma skin cancer. Rev Chim. 2018;69:2557–2562. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steen VD, Medsger TA Jr. The value of the health assessment questionnaire and special patient-generated scales to demonstrate change in systemic sclerosis patients over time. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1984–1991. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denton CP. Advances in pathogenesis and treatment of systemic sclerosis. Clin Med (Lond) 2016;16:55–60. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-1-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masi AT, Medsger TA Jr. Progress in the evolution of systemic sclerosis classification criteria and recommendation for additional comparative specificity studies. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:8–10. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, Medsger TA Jr, Rowell N, Wollheim F. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): Classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The analyzed data sets generated during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.