Abstract

BACKGROUND

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused major public panic in China. Pregnant women may be more vulnerable to stress, which may cause them to have psychological problems.

AIM

To explore the effects of perceived family support on psychological distress in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS

A total of 2232 subjects were recruited from three cities in China. Through the online surveys, information on demographic data and health status during pregnancy were collected. Insomnia severity index, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale, patient health questionnaire-9, somatization subscale of the symptom check list 90 scale, and posttraumatic stress disorder checklist were used to assess the psychological distress.

RESULTS

A total of 1015 (45.4%) women reported having at least one psychological distress. The women who reported having inadequate family support were more likely to suffer from multiple psychological distress (≥ 2 psychological distress) than women who received adequate family support. Among the women who reported less family support, 41.8% reported depression, 31.1% reported anxiety, 8.2% reported insomnia, 13.3% reported somatization and 8.9% reported posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which were significantly higher than those who received strong family support. Perceived family support level was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (r = -0.118, P < 0.001), anxiety symptoms (r = -0.111, P < 0.001), and PTSD symptoms (r = -0.155, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION

Family support plays an important part on pregnant women’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Better family support can help improve the mental health of pregnant women.

Keywords: Pregnant women, Perceived family support, Coronavirus, Psychological distress

Core Tip: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused major public panic in China. Pregnant women may be more vulnerable to stress, which may cause them to have psychological problems. The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of perceived family support on psychological distress in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that family support plays an important part on pregnant women’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Better family support can help improve the mental health of pregnant women.

INTRODUCTION

The outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global health threat[1] and is listed by World Health Organization (WHO) as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). According to WHO data, there were 72546247 confirmed cases and 1614014 deaths worldwide[2]. In China, there are more than 90000 confirmed cases, with deaths exceeding 4758[2]. Corona viruses mainly cause respiratory diseases, ranging from the common cold to severe respiratory diseases, with a fatality rate of around 1%[3].

The COVID-19 pandemic seriously threatens people’s physical health and can trigger various psychological crises. COVID-19 was associated with increased psychological distress not only in the general population[4], but also in clinical samples[5]. Importantly, women are more vulnerable to psychological distress, when experiencing disasters or traumatic events, compared to men[6]. During the outbreak of COVID-19, approximate 35% of the 52730 people in China experienced psychological distress[7]. Another online survey showed that during the COVID-19 outbreak, among the general Chinese population, 31.3% of participants had depressive symptoms and 36.4% of participants experienced anxiety[8]. In both studies, women showed higher levels of stress, anxiety and depression[7,8]. The impact of the epidemic on women's mental health is significantly higher compared to men[7,8].

As the changes in the level and function of the endocrine system during pregnancy, pregnant women often experience great mood swings and even mental disorders, such as anxiety[9], depression[10]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, pregnant women may suffer extra psychological stress for worrying about the adverse effects on their offspring caused by 2019-nCoV. A recent study reported that after the announcement of the COVID-19 epidemic, the prevalence of depressive symptoms among pregnant women was spiked as to before the announcement[11].

In Wuhan city, a total of 50340 have been confirmed of COVID-19, making it the worst-hit area in China. Wuhan was cordoned off 3 wk after the outbreak. To prevent infection, most all of Wuhan residents had to stay at home and isolated from society. Loss of income was the following stress for them. As a result, most Wuhan residents may not only suffer from the epidemic, but also suffer from isolation, stress and the loss of income[12].

Women who have supportive networks of friends and family may experience less stress and have better mental health conditions. Conversely, poor family relationships and social support might be associated with depressive symptoms[13]. A longitudinal study in pregnancy has found that partnership tension was the only predictor of women’s transient and chronic anxiety during pregnancy or postpartum period[14].The active support of the partner is a critical factor affecting the mental health of pregnant and postpartum women, and the support of the extended family is also important for the mental health conditions of pregnant women[14].

For family-centered Chinese culture, family support is probably the most important sources of social support[15]. Chinese women pay more attention to the family and are more susceptible to family relationships, compared with western women[16]. However, in the context of COVID-19 pandemic, it is unknown whether good family support can still benefit the psychological status of women. Therefore, after the announcement of the coronavirus epidemic in China, we conducted a mental health survey for pregnant women in different provinces of China, including Wuhan (Confirmed COVID-19 case > 60000), Beijing (Confirmed COVID-19 case: 581) and Lanzhou (Confirmed COVID-19 case: 24) in China. In addition, economic loss caused by COVID-19, characteristics related to pregnancy was investigated. The hypothesis of the study is that perceived family support is more important for the mental health of women during pregnancy than the economic loss caused by COVID-19 and the severity of the COVID-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A cross-sectional survey was performed in this study after the Chinese government announced the coronavirus epidemic (from February 1 to April 28, 2020). The women during pregnancy were invited electronically to complete an anonymous online questionnaire in Wuhan, Beijing and Lanzhou by social media app WeChat (WeChat, Tencent Inc, China), since the Chinese government demanded the public staying at home. The questionnaire was disseminated through notifications from the maternal and child health hospitals. As a result, a total of 2232 valid responses were received from Wuhan (34.8%), Beijing (40.2%) and Lanzhou (25.0%).

The protocol of the study was approved by the ethics committee of the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All participants provided the informed consent before participating in the study.

Questionnaire survey

A structured questionnaire was used to collect personal data, including socio-demographic variables, information of pregnancy, information of psychological distress, information about COVID-19 and the perceived family support in pregnancy. The socio-demographic variables included age, nationality, marital status, occupation, and education. The information of pregnancy included gestational age, parity, period and pregnancy complications. The information of psychological distress of the participants was assessed by the Chinese version of 5 international validity scales, include insomnia severity index (ISI), generalized anxiety disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), somatization subscale of the symptom check list 90 scale (SCL-90) and posttraumatic stress disorder checklist (PCL-5). Information about COVID-19 included income loss caused by COVID-19 and whether or not their relatives or friends were infected with COVID-19.

ISI is a 7-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the severity and impact of insomnia[17]. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale (0 = no problem; 4 = very severe problem), with a total score ranging from 0 to 28. The total score is interpreted as follows: No insomnia (0-7); sub-threshold insomnia (8-14); moderate insomnia (15-21); and severe insomnia (22-28)[18]. Participants with a total score ≥ 15 were rated as having insomnia in this study. GAD-7 is a tool for assessing the severity of generalized anxiety. The 7 items are rated on a 3-point Likert scale, with a total score ranging from 0 to 21 (0–4: Normal; 5–9: Mild anxiety; 10–14: Moderate anxiety and 15–21: Severe anxiety). Clinically significant anxiety can be detected when the total score reaches 5 or above[19,20]. PHQ-9 is a 9-item instrument for assessing the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 specially includes 9-item diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV), on which the clinical diagnosis of depressive disorder is based[21]. Each item is rated on a 3-point scale (0 = no symptom; 3 = presence of symptom almost every day), with a total score ranging from 0 to 27(0–4: Normal; 5–9: Mild depression; 10–14: Moderate depression, 15–19: Moderately severe depression, and 20-27 severe depression)[21]. In this study, participants with a total score ≥ 5 were rated as suffering from depression. SCL-90[22] somatization subscale was used to assess the severity of somatization symptoms. The responses to these 12 items can be scored from 0 (none) to 4 (too much) on a Likert scale, with a total score ranging from 12 to 60. Participants with a total score ≥ 24 were rated as having somatic symptoms in this study. PCL-5[23] was used to assess the presence and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. This is a 20-item self-report scale. Respondents were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) to indicate how much troubled they have been in the past month according to PCL-5. The recommended PCL-5 cut-off score for the diagnosis of PTSD is 33[24]. In this study, participants with a total score ≥ 33 were rated as suffering from PTSD.

The perceived family support level was measured with the items of objective support from family numbers (husband, parents, parents-in-law, sisters ⁄ brothers, children and other family members) of Social Support Rating Scale (Chinese version)[25]. Participants rated on a 4-point scales (1 = none, 2 = rarely, 3 = some support ⁄ care, 4 = strong support/care)[15].

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables, and χ2 test were used for categorical variables. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationship between perceived family support level and the five types of maternal psychological distress. Multiple linear regression was performed to examine the linear relationship between the scores of ISI, GAD-7, PHQ-9, SCL-90, PCL-5 and family support levels. In addition, a binary logistic regression analysis was conducted to estimate the association between perceived family support and psychological distresses by calculating odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). All tests were two-tailed, and the statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Women with a history of mental illness were not excluded from this study due to the small proportion (13 women).Significant differences were found between the women with and without psychological distress in terms of age (χ2 = 2.16, P = 0.031), region (χ2 = 89.7, P < 0.001), educational level (χ2 = 13.61, P = 0.001), annual household income (χ2 = 10.23, P = 0.017), income loss caused by COVID-19 (χ2 = 13.83, P = 0.003) and perceived family support (χ2 = 13.57, P = 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of responded women

|

Characteristics

|

n

(%)

|

Psychological distress

|

No psychological distress

|

F/χ2

|

P

value

|

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 30.25 ± 3.99 | 30.05 ± 3.99 | 30.42 ± 3.98 | 2.16 | 0.031 |

| Region, n (%)1 | 89.71 | < 0.001 | |||

| Wuhan | 777 (34.8) | 382 (49.2) | 395 (50.8) | ||

| Peking | 897 (40.2) | 306 (34.1) | 591 (65.9) | ||

| Lanzhou | 558 (25.0) | 327 (58.6) | 231 (41.4) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | 3.70 | 0.069 | |||

| married | 2179 (97.6) | 984 (45.2) | 1195 (54.8) | ||

| Single, separated, divorced or widowed | 53 (2.4) | 31 (58.5) | 22 (41.5) | ||

| Educational level, n (%) | 13.67 | 0.001 | |||

| < 14 yr | 1016 (45.6) | 504 (49.6) | 512 (50.4) | ||

| ≥ 14 yr | 1216 (43.7) | 511 (42.1) | 705 (57.9) | ||

| Annual household income (CNY), n (%) | 10.23 | 0.017 | |||

| < 80000 | 706 (31.6) | 350 (49.6) | 356 (50.4) | ||

| 80000 | 1255 (56.2) | 552 (43.9) | 703 (56.1) | ||

| ≥ 300000 | 273 (12.2) | 113 (41.4) | 160 (58.6) | ||

| Income loss caused by COVID-19(CNY), n (%) | 13.83 | 0.003 | |||

| < 20000 | 862 (38.7) | 331 (38.8) | 522 (61.2) | ||

| ≥ 20000 | 1362 (61.3) | 673 (50.7) | 692 (49.3) | ||

| Employment status, n (%) | 0.01 | 0.999 | |||

| Employed | 1496 (67.1) | 681 (45.5) | 815 (54.5) | ||

| Housewife | 736 (32.9) | 334 (45.4) | 402 (54.6) | ||

| Perceived family support level, n (%) | 13.57 | 0.001 | |||

| Less2 | 134 (6.0) | 71 (53.0) | 63 (47.0) | ||

| Some | 466 (20.9) | 246 (52.8) | 220 (47.2) | ||

| Strong | 1632 (73.1) | 706 (43.3) | 926 (56.7) | ||

Confirmed COVID-19 cases in participating city: Wuhan: > 50000 cases; Beijing: 581 cases; Lanzhou: 24 cases.

Participants rated on “none” and “rarely” scale.

Psychological distress in different perceived family support levels

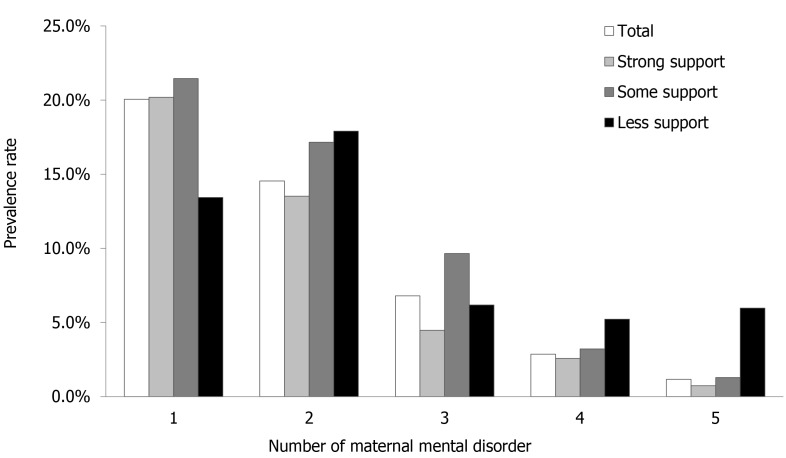

A total of 1015 (45.4%) women reported at least one instance of psychological distress. As shown in Figure 1, more women with less or some family support reported suffering multiple instances of psychological distress (≥ 2 type of psychological distress) than those with strong family support. A total of 5.2% of women with less family support reported having four types of psychological distress and 5.9% of them had five types of psychological distress, which was significantly higher than those with some family support (3.2%,1.3%) or those with strong family support (2.6%, 0.7%).

Figure 1.

Frequency for self-reported multiple psychological distresses in different perceived family support level. 1: Report one type of psychological distress; 2: Report two type of psychological distress; 3: Report three type of psychological distress; 4: Report four type of psychological distress; 5: Report five type of psychological distress.

Women with less or some family support reported significantly higher rates of psychological distress than women with strong family support (all P < 0.05). Among women with less family support, 41.8% reported depression, 31.1% reported anxiety, 8.2% reported insomnia, 13.3% reported somatization and 8.9% reported PTSD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Self-reported psychological distresses of pregnant women with different perceived family support level, n (%)

|

|

Total

|

Less PFS

|

Some PFS

|

Strong PFS

|

F/χ2

|

P

value

|

| Depression | 795 (35.6) | 56 (41.8) | 207 (44.4) | 532 (32.6) | 24.15 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety | 491 (22.0) | 42 (31.1) | 128 (27.5) | 321 (19.6) | 19.79 | < 0.001 |

| Insomnia | 77 (3.4) | 11 (8.2) | 15 (3.2) | 51 (3.1) | 9.72 | 0.008 |

| Somatization | 180 (8.1) | 18 (13.3) | 41(8.8) | 121(7.4) | 6.34 | 0.042 |

| PTSD | 52 (2.3) | 12 (8.9) | 14 (3.0) | 26 (1.6) | 30.41 | < 0.001 |

PFS: Progress-free survival; PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Association between family support and psychological distress

The perceived family support levels negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score, r = -0.118, P < 0.001), anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 scores, r = -0.111, P < 0.001), and PTSD symptoms (PCL-5 score r = -0.155, P < 0.001). Logistic regression results showed there was a significant association between perceived family support and psychological distress of pregnant women (Table 3). After adjusting for age, marital status, region, educational level, annual household income, and income loss caused by COVID-19, less perceived family support displayed a significant association with anxiety (GAD-7 score ≥ 5, OR = 1.98, 95%CI: 1.32-2.96, P < 0.01), insomnia (ISI score ≥ 15, OR = 3.47, 95%CI: 1.68-7.16, P < 0.01), and PTSD (PCL-5 score ≥ 33, OR = 6.69, 95%CI: 3.07-14.55, P < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between perceived family support [n (%)] and self-reported maternal psychological distresses

|

|

Depression

|

Anxiety

|

Insomnia

|

Somatization

|

PTSD

|

| Spearman correlation coefficient, r | |||||

| -0.118b | -0.111b | -0.025 | -0.038 | -0.155b | |

| Multiple linear regression, β | |||||

| -0.973b | -0.638b | -0.195 | -0.418 | -2.238b | |

| Logistic regression analysis, OR (95%CI) | |||||

| Strong support | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Some support | 1.56 (1.26-1.94)b | 1.69 (1.24-2.04)b | 1.13 (0.62-2.04) | 1.02 (0.65-1.45) | 1.91 (0.96-3.79) |

| Less support | 1.33 (0.90-1.92) | 1.98 (1.32-2.96)b | 3.47 (1.68-7.16)b | 1.41 (0.80-2.48) | 6.69 (3.07-14.55)b |

OR and 95%CI were estimated using binary logistic regression and adjusted for age, marital status, region place of residence, educational level, annual household income, income loss caused by COVID-19.

P < 0.01.

PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder.

DISCUSSION

To our best knowledge, this is the first study to explore the relationship between perceived family support and psychological distress in pregnant women during major life-threatening public health events. In this study, we had 3 main findings: (1) A significant proportion (45.4%) of pregnant women reported at least one psychological distress during COVID-19 pandemic; (2) The risk of insomnia, anxiety and PTSD in women with less family support was 3.46 times, 1.97 times and 6.69 times higher than that in women with strong perceived family support, respectively; and (3) Depression symptoms (PHQ-9 score), anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 score) and PTSD symptoms (PCL-5 score) were significantly negatively associated with perceived family support.

It is speculated that residents living in Wuhan suffered from higher levels of psychological distress, because this place was most affected by the epidemic[7] in mainland China. This may also increase the risk of psychological distress in pregnant women[11]. Interestingly, our study did not find an increase in the rate of maternal psychological distress amongst women in Wuhan. On the contrary, more women living in Lanzhou reported suffering from psychological distress, though it was only 24 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Lanzhou. That may be due to the fact that more women living in Lanzhou reported insufficient support from family numbers than women living in Beijing and Wuhan. The results showed that depression (35.6%) and anxiety (22.0%) were the most common disorders reported by pregnant women. In addition, at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic, the pregnant women also suffered from somatization (8.1%), insomnia (3.4%) and PTSD (2.3%). The findings were similar to those of previous studies, indicating that pregnant women may be more vulnerable to depression in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic. A recent study reported that during the COVID-19 epidemic, the depression rate amongst Chinese pregnant women rose to 29.6%[11]. Another study showed that 28.8% of Danish women had anxiety/depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic[26].

There is extensive evidence that psychological distress during pregnancy are thought to increase the risk of developing psychological dysfunction in the offspring[27]. Pregnancy are very special periods for women. Affected by changes in the level and function of the endocrine system during pregnancy, mothers often experience huge mood swings and even mental disorders, such as anxiety[9], depression[10], and sleep disturbance[28]. The prevalence of depression in pregnant and postpartum women was estimated to be between 7% and 25%[10,26,27], and the prevalence of anxiety disorders is estimated to be between 4% and 39%[29]. However, our results showed that with different levels of family support, there were significant differences in the proportion of women with mental disorders during pregnancy. Women with inadequate family support were more likely to suffer from multiple psychological distresses. The strengthening of family support, the reporting rate of maternal psychological distress reduced. These findings highlight the essential role of adequate family support in mental health of pregnant women through major life-threatening public health events.

Social support, including supports from family members, colleagues, friends, neighbors, professionals, and organizations, is important for maternal mental health[15]. Due to the sudden outbreak, features and clinic symptoms of the COVID-19 are still unclear during the peak of the epidemic. The Chinese government intensified its management of the pandemic through public health interventions, such as strengthening some blockades, demand of staying at home. Hospitals had to terminate health care services for pregnant women to prevent infection, and most of them were trapped at home and isolated themselves from society. The confinement conditions have made the support of family members the only source of social support. In the general population, social support is widely regarded as a key factor in relieving perinatal depression[30]. A large number of studies have confirmed that family support has a positive effect on the level of perceived psychological stress[6,31-33]. According to Cohen[34], the relationship between perceived family support and life satisfaction was very strong.

Perceived family support makes a person feel cared for, loved, and dependent on family numbers when needed[33]. The levels of perceived family support can affect the way people deal with and adapt to stressful events, thereby reducing the negative effects on mental and physical health[6]. Therefore, adequate family support can alleviate the pressure caused by the COVID-19 outbreak. However, although physical care for pregnant women has been greatly improved in China in the past few decades, little attention has been paid to emotional care[15]. The findings of this study emphasized the importance of emotional care for pregnant women. The role and mechanism of family support in alleviating the negative psychological effects of adverse events have not been clearly or fully explained. Further research is needed to understand the role and mechanism of this factor in order to utilize family support to help pregnant women in major life-threatening public health events.

However, several limitations have to be considered when interpreting these findings. Firstly, the data obtained from online surveys and maternal psychological distress relied on self-reported measurements. Women may inaccurately report the presence or absence of psychological distress. Secondly, although internationally valid and reliable questionnaires were utilized in this study, these questionnaires did not provide a diagnosis of mental disorders. Thirdly, the evaluation of family support used the subjective feelings of women rather than the social support rating scale. This may make our results less precise. Fourthly, other influencing factors such as family relationship, family conflict, and family resources are also important variables that affect the psychological well-being of pregnant and postpartum women, which were not taken into account in this study. Finally, a cross-sectional analysis of this study suggests that there is an association between maternal psychological distress and family support, rather than a causal relationship. Future research may focus on a longitudinal study to confirm causality.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has a negative impact on the mental health of Chinese pregnant women. Family support was significantly negatively correlated with psychological distress. Compared with women with strong family support, women with insufficient family support were more associated with the risk of anxiety, insomnia, depression and PTSD. This study shows that in major life-threatening public health events, family support has a positive impact on the mental health of pregnant women. However, cross-sectional nature limits the interpretation of the causal relationship between family support and mental health. Further longitudinal studies about the causal relationship between family support and mental health will be an essential area of future research, which may help to identify appropriate and effective interventions for pregnant and postpartum women to prevent from the mental health problems.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Pregnant women may be more vulnerable to psychological distress during major life-threatening public health events. The spread of the corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is likely to cause greater psychological stress, which may cause extra psychological problems for pregnant women.

Research motivation

The spread of the COVID-19 may cause extra psychological problems for pregnant women. Women who have better supportive networks of family may experience less psychological stress. However, the literatures on the role of family support in maternal psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic was limited.

Research objectives

This study aimed to clarify the potential role of family support on psychological distress for women during pregnancy stages at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic.

Research methods

The authors retrospectively collected socio-demographic variables, information of pregnancy, and information of psychological distress and the perceived family support of pregnant women in China.

Research results

Among 2232 pregnant women, 45.4% women reported having at least one psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. The women who reported having inadequate family support were more likely to suffer from multiple psychological distress than women received adequate family support. Perceived family support was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and PTSD symptoms.

Research conclusions

Family support was significantly negatively correlated with psychological distress. Adequate family support has a positive impact on the mental health of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research perspectives

Adequate family support is important for maternal mental health. Further research is needed to understand the role and mechanism of this factor in order to utilize family support to help pregnant women in major life-threatening public health events.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The protocol of the study was approved by the ethics committee of the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Informed consent statement: All participants provided the informed consent before participating in the study.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: February 10, 2021

First decision: May 5, 2021

Article in press: June 17, 2021

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Janiri D S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Yan-Ni Wang, Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health, School of Public Health, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China.

Zhao-Jing Yuan, Qingdao Mental Health Center, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266000, Shandong Province, China.

Wan-Chun Leng, Qingdao Mental Health Center, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266000, Shandong Province, China.

Lu-Yao Xia, CAS Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 10000, China.

Ruo-Xi Wang, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430070, Hubei Province, China.

Ze-Zhi Li, Department of Neurology, Ren Ji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200127, China.

Yong-Jie Zhou, Department of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Shenzhen Kangning Hospital, Shenzhen 510810, Guangdong Province, China.

Xiang-Yang Zhang, CAS Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China. zhangxy@psych.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Available from: https://www.who.int/

- 3.Rasmussen SA, Smulian JC, Lednicky JA, Wen TS, Jamieson DJ. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and pregnancy: what obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moccia L, Janiri D, Giuseppin G, Agrifoglio B, Monti L, Mazza M, Caroppo E, Fiorillo A, Sani G, Di Nicola M, Janiri L. Reduced Hedonic Tone and Emotion Dysregulation Predict Depressive Symptoms Severity during the COVID-19 Outbreak: An Observational Study on the Italian General Population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Nicola M, Dattoli L, Moccia L, Pepe M, Janiri D, Fiorillo A, Janiri L, Sani G. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and psychological distress symptoms in patients with affective disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;122:104869. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren JH, Chiang CL, Jiang XL, Luo BR, Liu XH, Pang MC. Mental disorders of pregnant and postpartum women after earthquakes: a systematic review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2014;8:315–325. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2014.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33:e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang YT, Yao Y, Dou J, Guo X, Li SY, Zhao CN, Han HZ, Li B. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Maternal Anxiety in Late Pregnancy in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13 doi: 10.3390/ijerph13050468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asaye MM, Muche HA, Zelalem ED. Prevalence and Predictors of Postpartum Depression: Northwest Ethiopia. Psychiatry J. 2020;2020:9565678. doi: 10.1155/2020/9565678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu H, Duan C, Li C, Fan J, Li H, Chen L, Xu H, Li X, Guo Y, Wang Y, Li J, Zhang T, You Y, Yang S, Tao X, Xu Y, Lao H, Wen M, Zhou Y, Wang J, Chen Y, Meng D, Zhai J, Ye Y, Zhong Q, Yang X, Zhang D, Zhang J, Wu X, Chen W, Dennis CL, Huang HF. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020; 223: 240.e1-240. :e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horton R. Offline: 2019-nCoV-"A desperate plea". Lancet. 2020;395:400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30299-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau Y, Yin L, Wang Y. Antenatal depressive symptomatology, family conflict and social support among Chengdu Chinese women. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:1416–1426. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0699-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Kuo CP, Hsiao CY, Lu YC, Hsu MY, Kuo PC, Lee MS, Lee MC. Development of a Chinese childbearing attitude questionnaire for infertile women receiving in vitro fertilization treatment. J Transcult Nurs. 2013;24:127–133. doi: 10.1177/1043659612472060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie RH, Yang J, Liao S, Xie H, Walker M, Wen SW. Prenatal family support, postnatal family support and postpartum depression. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:340–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu Y, Wang Y, Wen S, Guo X, Xu L, Chen B, Chen P, Xu X. Association between social and family support and antenatal depression: a hospital-based study in Chengdu, China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:420. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2510-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601–608. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choueiry N, Salamoun T, Jabbour H, El Osta N, Hajj A, Rabbaa Khabbaz L. Insomnia and Relationship with Anxiety in University Students: A Cross-Sectional Designed Study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale--preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1973;9:13–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibrahim H, Ertl V, Catani C, Ismail AA, Neuner F. The validity of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) as screening instrument with Kurdish and Arab displaced populations living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:259. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1839-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang XD, MaH . Social Support Rating Scale. Beijing: Chinese Mental Health Publishing House, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aktar E, Qu J, Lawrence PJ, Tollenaar MS, Elzinga BM, Bögels SM. Fetal and Infant Outcomes in the Offspring of Parents With Perinatal Mental Disorders: Earliest Influences. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:391. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krawczak EM, Minuzzi L, Simpson W, Hidalgo MP, Frey BN. Sleep, daily activity rhythms and postpartum mood: A longitudinal study across the perinatal period. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33:791–801. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2016.1167077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Heyningen T, Honikman S, Myer L, Onah MN, Field S, Tomlinson M. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety disorders amongst low-income pregnant women in urban South Africa: a cross-sectional study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20:765–775. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0768-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mann JR, Mannan J, Quiñones LA, Palmer AA, Torres M. Religion, spirituality, social support, and perceived stress in pregnant and postpartum Hispanic women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39:645–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isobel S, Goodyear M, Foster K. Psychological Trauma in the Context of Familial Relationships: A Concept Analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2019;20:549–559. doi: 10.1177/1524838017726424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campos B, Ullman JB, Aguilera A, Dunkel Schetter C. Familism and psychological health: the intervening role of closeness and social support. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2014;20:191–201. doi: 10.1037/a0034094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]