Abstract

BACKGROUND

Children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may have great difficulties when their routines change, and this may affect the psychological well-being of their parents. For this reason, it is important to examine studies that address the mental health of parents in order to adapt to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

AIM

To determine the mental health status of parents with children diagnosed with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS

The study, which is a systematic review, was conducted between December 15, 2020 and December 30, 2020 by scanning articles in English. The Scopus, Science Direct, PubMed, Cochrane, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases were used for scanning. The keywords COVID-19 AND (“autism” OR “autistic” OR “autism spectrum disorder”) AND parent AND (“mental health” OR “anxiety” OR “stress”) were used in the search process. The inclusion criteria in the study were findings regarding the mental health of parents with children diagnosed with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic, addressing their anxiety and stress situations, being a research article, and accessing the full text of the article.

RESULTS

In the study, a total of 6389 articles were reached, and the full texts of 173 articles were evaluated for eligibility. After the articles excluded by the full-text search were eliminated, 12 studies involving 7105 parents were included in the analysis. The findings obtained from the articles containing data on mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic of parents with children with autism spectrum disorder were discussed in three groups. These were findings on the experiences of parents with children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic regarding the areas where parents with children with ASD need support in the COVID-19 pandemic and methods of coping with the COVID-19 pandemic for parents with children with ASD. In the systematic review, it was determined that the anxiety and stress of the parents increased, they needed more support compared to the pre-pandemic period, and they had difficulty coping.

CONCLUSION

In this systematic review, it was concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the mental health of the parents of children with ASD.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, COVID-19, Mental health, Pandemic, Parents

Core Tip: Parents with a child diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may have a hard time explaining the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in routines and safety measures to their children in a comprehensible way. Parents may feel stressed and anxious as they have difficulty managing the process and need support in using effective coping methods. It is important to analyze the results of studies on the mental health of parents with children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic period. This is the first study to systematically examine the mental health status of the parents of children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic period.

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and disaster processes significantly adversely affect individuals with severe and chronic mental illness. Data on individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in the world, and their parents’ experiences in extraordinary conditions are still limited[1]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition defines autism as a pervasive developmental disorder characterized by disturbances in social interaction and communication (difficulty in social-emotional response, inability to use and understand non-verbal communication behaviors, inability to initiate and maintain communication appropriate to the level of development), limited and repetitive behaviors. The prevalence of autism, which causes limitations in performing the daily life functions of the individual with its early symptoms, continues to increase[2]. Autism begins in childhood and affects one in every 160 children in the world[3]. In a study conducted throughout the United States, it was reported that ASD was observed in one of every 54 children[4,5].

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 epidemic as a global pandemic on March 11, 2020[6]. With the announcement of the pandemic, some restrictions started to be applied in countries. Initiatives to reduce the rate of transmission include behavioral recommendations such as comprehensive and frequent hand washing, maintaining social distance, avoiding in-person contact and wearing a facemask[7]. Groups with special needs have faced bigger problems during the pandemic. Children with ASDs and their parents are among the groups adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic[8-10]. The pandemic that caused mental problems even in healthy individuals has caused much more distress in children with ASD, who are extremely sensitive to changes in their routine[11,12]. Children with ASD may present the psychosocial distress they experience due to the pandemic in the form of aggression, tantrums or refusing to participate in daily activities[8]. Furthermore, children with ASD may have difficulties without training in hand washing, avoiding eye contact, and especially wearing a facemask. The necessity to wear a mask is particularly disturbing for any child who has sensory sensitivity and does not understand the rationale for wearing a mask[13,14].

Parenting a child with ASD may be stressful[15]. Meeting the needs of these children may be more difficult for parents due to the seriousness of their condition and the chronic spectrum, mental health comorbidities, intense interventions that children need and the difficulty of getting services[16]. During the pandemic, disruption in daily routines, difficulty in accessing health services, inability to access private care and the increased anxiety of parents worsen the psychological wellbeing of children and increase their behavioral problems[17]. Parents have a difficult period in management of children with special needs during the pandemic where people are confined to homes. Normally, the burden of parents was shared with care centers, schools and special education centers. Social distancing is placed between caregivers who can support parents in the care process, and individuals who support these parents in care such as grandparents and parents are left alone due to the risk of COVID-19 transmission[18,19]. As the burden of parents increases, their coping capacity may decrease[20]. The parents of children with ASD, who had felt isolated before the COVID-19 pandemic, may feel more lonely and stressed during the pandemic with compulsory social distancing[21].

Parental health and well-being are directly related to the quality of care parents can provide to their children[21]. In the COVID-19 pandemic, international organizations such as WHO, the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund and the American Academy of Pediatrics have created guidelines to support parents in management of the pandemic and stress management[22-24]. Similarly, Narzisi[12] recommended the parents of children with ASD to explain what COVID-19 is to the child, structure their daily routines according to this process and maintain their connections with educational institutions so that they can have a healthy pandemic process. It is important for parents to be able to explain the pandemic process to their children so that they and their children feel safer. For this reason, parents should be supported in teaching their children social distancing rules[21]. It is very important that the parents of children with ASD receive social support and have access to professional health services in reducing their stress and improving their emotional wellbeing[16,25]. In the COVID-19 pandemic, anxiety and stress situations, needs and coping methods should be determined, as well as mental health conditions in parents with children with ASD.

This systematic review determined the mental health status of the parents of children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a systematic review. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses protocol was followed in preparation of the study and the report. In this systematic review, to reduce the risk of possible bias, the processes of literature review, article selection, data extraction and evaluation of article quality were carried out independently by two researchers, each stage was checked in a session with the third researcher, and a consensus was established. In a session where the three researchers were together for carrying out the process in appropriate form and quality, a pilot study was conducted including searching through the PubMed search engine with a keyword (COVID-19, autism, parent) within the scope of the study, selecting an article, extracting data with five research articles and evaluating the quality of the articles. The differences of opinion and information that emerged after the pilot study were resolved through discussion.

Search strategy

The search processes for this systematic review were conducted between December 15, 2020 and December 30, 2020 and updated on 17 March 2021 to include the latest publications in the publication process. The search procedure was achieved by browsing the Web of Science, PubMed (including MEDLINE), Cochrane, Scopus, Science direct and Google Scholar databases using the keywords COVID-19 AND (“autism” OR “autistic” OR “autism spectrum disorder”) AND parent AND (“mental health” OR “anxiety” OR “stress”). The list of references of the included studies was reviewed to access additional studies.

Selection criteria and selection of studies

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: The articles in English, which could be accessed in full text without any limitation of publication year and country, were included in the study. The systematic review was created according to the PICOS strategy. Participants: the parents of children with ASD; Interventions: effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health; Comparators: the parents of children without ASD; Main outcomes: anxiety, stress, difficulty in coping, loneliness, inadequacy of support systems, social isolation, change in routines and financial difficulties; Additional outcomes: exercise at home, practicing yoga and meditation, reading newspapers, getting support from a therapist, cooking meals, talking to their loved ones on online platforms during the pandemic. These results have been reported in studies and included and presented in this systematic review.

Studies suitable for this systematic review were included based on the following inclusion criteria. In the COVID-19 pandemic, the findings related to the mental health of parents with children with ASD and the anxiety and stress situations they experienced were handled, being a research article, the publication language was English, and the full text of the article was available. Studies with an unknown method and those dealing with the experiences of children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic were excluded.

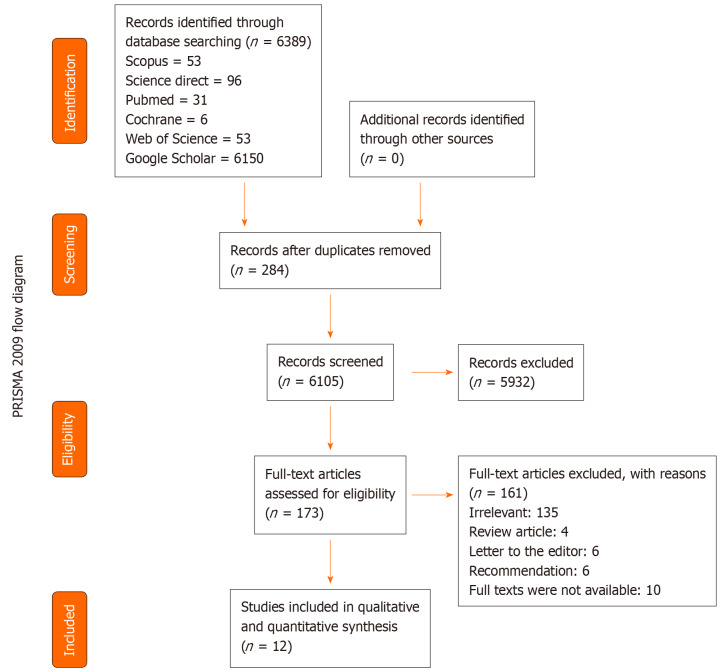

Identification and selection of the studies were achieved independently by two researchers (Yılmaz B, Azak M) in accordance with the inclusion criteria. After repetitive studies were removed from the search results, selection was made according to the title, abstract and full text, respectively. The selection process followed in the systematic review is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction

A data extraction tool developed by the researchers was used to obtain data in the study. With this data extraction tool, data about the authors of the studies and the publication year, research type, method, sample size, number of cases, the country in which the data were collected, the year the data were collected, the data collection instrument and the main results were obtained.

Evaluation of methodological quality

The methodological quality of the articles included in this systematic review was evaluated by one of the researchers and checked by the other two researchers. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement[26] was used to evaluate the quality of the observational (descriptive, cross-sectional and case-control) studies, and the “Critical Appraisal Skills Program: Quality Appraisal Criteria for a Qualitative research” (CASP) was used for qualitative research (https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf). The STROBE Statement is a checklist of 22 items that indicate the sections that should be written in the article during the preparation of observational research articles. CASP is a form consisting of 10 items that may be used to evaluate the quality of qualitative research.

Data analysis

The narrative synthesis method was used in the analysis of the data. Narrative synthesis is a method that may be used to synthesize both quantitative and qualitative studies, and it can be used when the findings of studies included in the systematic review are not similar enough for meta-analysis[27]. The pattern, data collection methods and data collection instruments of the studies examined in this systematic review were different. Therefore, the findings are presented with the narrative synthesis method.

Ethical aspect of research

In the study, the research articles included in the sample did not require ethics committee approval because they were obtained from accessible electronic databases and search engines. All stages of the study were carried out in accordance with the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

Scanning results

As a result of the search, 6389 records were initially reached. As a result of the examination made according to the title, abstract and full text, respectively, 173 articles were reached. Repetitive records were removed, and data extraction was performed with twelve studies after the examination according to the inclusion criteria. Explanations about the selection process of the articles are shown in Figure 1. In this review, twelve studies that met the inclusion criteria were analyzed, and Table 1 shows the country, type, sample characteristics, data collection instruments and main results of these studies. A total of 12 studies were included in a quantitative and qualitative design (cross-sectional descriptive: 8; comparative cross-sectional descriptive: 1; cohort study: 1; quasi-experimental design: 1; qualitative design: 1). A total of 7105 parents who have children with a diagnosis of ASD were enrolled in the studies that were included in this study. The included studies were carried out in United States, China, Spain, Italy, Saudi Arabia, Portugal and Turkey. While the quantitative research data included in the study were collected through online questionnaires, the qualitative research data were obtained by phone call via semi-structured forms.

Table 1.

Summary of the studies included in this systematic review

|

Ref.

|

Country

|

Research type

|

Data collection instrument

|

Sample

|

Main results

|

Critical appraisal toll

|

| Alhuzimi[28], 2021 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional descriptive | Demographic Form | 150 parents of children with ASD | While 94% of the parents reported that their stress levels increased in the COVID-19 pandemic, 78.7% of them reported that the pandemic negatively affected their emotional well-being. The parents stated that the support they received from their relatives during this process reduced their stress levels, fatigue and improved emotional their wellbeing | 19/22 STROBE |

| The Parent Stress Index-Short Form | ||||||

| The General Health Questionnaire | ||||||

| Althiabi[34], 2021 | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional descriptive | Demographic Form | 211 parents of children with ASD | The parents reported that, in the COVID-19 pandemic, they had difficulty calming their children due to changes in routine and experienced fear and anxiety. They reported that they had difficulties in finding activities and games to keep their children entertained at home. During this process, the parents reported that they sought help from their friends, teachers, doctors and psychologists | 21/22 STROBE |

| The General Health Questionnaire | ||||||

| The Hospital Anxiety and DepressionScale | ||||||

| The Family Impact Questionnaire | ||||||

| Amorim et al[29], 2020 | Portugal | Comparative, cross-sectional descriptive | Questionnaire form created by researchers | 43 parents of children with ASD and 56 control group participants (parents of children without neurodevelopmental problems) | In the study, it was determined that the parents of children with ASD had higher anxiety levels than those with healthy children. The parents reported that they felt tired during the pandemic as they had to spend extra time on their children with ASD. In the study, 55.8% of the parents of children with ASD and 29.6% of the control group reported that the pandemic had a negative effect on emotion management. Social isolation, inability to spend time outside, sudden changes in routines, boredom and distance education practices were reported as the most difficult areas for parents. The parents stated that they frequently talked to their families, close friends, colleagues, and some parents received support from a therapist | 17/22 STROBE |

| Bent et al[31], 2020 | China | Qualitative | Interview formcreated byresearchers | 15 parentsofchildren withASD | The parents had trouble explaining COVID-19 and safety measures to their children. Sudden changes in routines increased children’s crying spells and aggression. The parents had difficulty coping with these behavioral problems and adapting to e-learning. The participants reported that they exercised, practiced yoga, meditation, prayed, read newspapers and talked with their close friends online during this period. | 9/10 CASP |

| Colizzi et al[30], 2020 | Italy | Cross-sectional descriptive | 40-question questionnaire created by researchers | 527 parents of children with ASD | The parents reported that having a single child, the inability of the child with ASD to speak, the male gender of the child and a single parent having the child's responsibility were among the factors increasing their stress during the pandemic. 19.1% of the parents reported that they received support from a neuropsychiatrist due to the onset of new behavioral problems in their children and due to feeling helpless. The sudden curfew restrictions caused stress for the parents and their children. 47.4% of the participants stated that they needed more health services during the pandemic, 30% needed to strengthen their home support systems, and 16.8% needed more state support in quarantine | 18/22 STROBE |

| Liu et al[36], 2021 | China | Quasi-experimental | The Self-rating Anxiety Scale | 125 mothers having children with ASD | With web-based support, it was found that the mothers' stress and anxiety levels decreased in the COVID-19 pandemic period. The parents reported feeling relaxed as the program facilitated parent-child interaction | 20/22 STROBE |

| The Self-rating Depression Scale | ||||||

| The Parenting Stress Index-Short Form | ||||||

| The Herth Hope Index | ||||||

| Lugo-Marín et al[33], 2021 | Spain | Cross-sectional descriptive | The Child Behavior Checklist | 104 children with ASD, their parents and caregivers | In the data collected 8 wk after the lockdown onset, it was observed that there was an increase in somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and psychoticism in the parents | 21/22 STROBE |

| The Symptom Checklist 90 Revised | ||||||

| Manning et al[32], 2020 | The United States of America | Cross-sectional descriptive | Questionnaire form created by researchers | 474 parents of children with ASD | It was determined that the children with ASD and their parents experienced high levels of stress and fear during the pandemic. The children who had to spend a long time at home exhibited aggressive and problematic behaviors, causing more stress in their parents and making it difficult to cope. 54.5% of the participants stated that they were worried about their children being at home all the time, 52.1% were afraid that they or their children could be infected with COVID-19, and 30.7% stated that they experienced stress due to economic problems. The parents reported that they received the most support from family, friends, school guidance, therapy center and parent support group, respectively, during the pandemic. | 18/22 STROBE |

| Mumbardo-Adam et al[35], 2021 | Spain | Cross-sectional descriptive | A semi-structured online survey | 47 individuals with ASD and parents | The parents reported that they developed new strategies to better manage quarantine with their children with ASD. During this period, 36.2% of the parents reported that they communicated with their relatives online, and 23.4% received online psychological support | 20/22 STROBE |

| Mutluer et al[17], 2020 | Turkey | Cross-sectional descriptive | Sociodemographic FormThe Beck Anxiety | 87 individuals with ASD and parents | The parents reported that children with ASD felt under house arrest because they had difficulty obeying social distancing rules and did not want to wear masks. The participants stated that their children's sleep patterns were disturbed during the pandemic, and they also had sleep problems. The majority of the parents said they could not continue distance education and needed support in this regard. It was determined that 25% of the parents had minimal anxiety, 29% had mild anxiety, 21% had moderate anxiety, and 25% had severe anxiety. The parents reported that they provided each other rest breaks when there was more than one adult at home who could take care of the child with ASD | 17/22 STROBE |

| Inventory (for parents) | ||||||

| The Aberrant Behavior | ||||||

| Checklist (for children) | ||||||

| The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (for children) | ||||||

| Wang et al[37], 2021 | China | Cross-sectional descriptive | Sociodemographic Form | 1764 parents of children with ASD and 4962 parents of typically developing children | It was found that the parents of children with ASD had more deterioration in their diet, less physical exercise, less social support, higher levels of psychological stress, anxiety and depression, and worse coping strategies than the parents of children with normal development | 22/22 STROBE |

| The COVID-19 Questionnaire | ||||||

| The Connor-Davidson Resilience ScaleThe Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire | ||||||

| The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale | ||||||

| White et al[38], 2021 | The United States of America | Cohort study | Brief Family Distress Scale | 3502 parents of children with ASD | 80% of the parents reported disruptions in their children's special education. 64% of them stated that these disruptions had severely or moderately impacted their children’s ASD symptoms, behaviors or challenges. Increasing distress and stress negatively affected their lives | 22/22 STROBE |

ASD: Autism spectrum disorder; COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019.

Methodological quality assessment results

When the reporting quality of the observational studies was evaluated over 22 points with the 22-item STROBE, the mean score was found to be 19.54 (range: 17-22). In the evaluation of qualitative research using CASP, it was found that the quality score was 9.0 (Table 1). While disasters and epidemics affect the whole society negatively, they affect individuals with ASD in the disadvantaged group and their parents mentally. In the systematic review, the results obtained from the articles containing data on the mental health of parents with children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic were discussed in three groups. These were results regarding the experiences of parents with children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic, results regarding the areas where parents with children with ASD need support in the COVID-19 pandemic and methods of coping with the COVID-19 pandemic for parents with children with ASD.

Results on the experiences of parents of children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic affected the parents of children with ASD mentally. In the study conducted in Saudi Arabia, 94% of the parents reported that their stress levels increased, while 78.7% stated that the pandemic affected their emotional wellbeing negatively[28]. Amorim et al[29] found that parents with children with ASD had higher anxiety levels than those with healthy children. Colizzi et al[30] reported that having a single child, the child with ASD not being able to speak, the child with ASD being male and a single parent having the child's responsibility were among factors that increased stress in the parents. Curfew restrictions that emerged suddenly during the pandemic caused stress in parents and children. Bent et al[31] stated that parents had difficulty explaining the restrictions and security measures to their children. The parents reported that their children had difficulty in obeying the social distancing rules, they could not take their children to the market, etc. because they did not want to wear a mask and felt under house arrest[17,31]. In the study by Manning et al[32], 54.5% of the participants stated that they were worried about their children being at home all the time, 52.1% were afraid that they or their children could be infected with COVID-19, and 30.7% reported that they had stress due to economic difficulties. In Spain, it was observed that there was an increase in somatization, obsessive behavior, depression, anxiety, hostile behavior, paranoid ideas, phobic anxiety and aggression in the parents according to the data collected 8 wk after the start of the lockdown[33].

For individuals with ASDs, changes in their routine may be very disturbing and challenging. It was reported that this situation led to serious behavioral disorders such as crying episodes, increase in aggression and rejection of transition[31]. In the study by Amorim et al[29] the mean anxiety score (8.75 ± 0.96) of parents with a child with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic was found to be significantly higher than the mean score of parents with healthy children (5.36 ± 2.71). Althiabi[34] also reported that the stress levels of parents increased, and they had difficulty in maintaining their mental wellbeing. Children's adaptation levels affect the parents’ anxiety. It was determined that children who could continue their routines (7.72 ± 1.84) had significantly higher levels of adaptation than those who could not (5.25 ± 2.75). In the same study, the parents reported that they felt helpless because there was not enough time to change routines. In the study, some parents reported that their children adapted to the situation without any major problems and thought of this process as a school holiday. The majority of parents, on the other hand, stated that other children had to continue their education in the home environment due to the pandemic, and they were tired of housework. One of the changing routines during the pandemic is that e-learning has been placed at the center of life. Parents reported that they felt tired as they had to spend extra time on their children with ASD during the pandemic. Parents revealed that they felt lonely and bored as they had to assume the role of educators during the pandemic. Some participants stated that their children who spent more time at home during the pandemic felt better as they took more responsibility in housework. In another study, 40.4% of the parents reported that they could spend more time with their ASD-diagnosed children, and 31.9% calmed their children by creating school-related activities[35]. In the study by Mutluer et al[17] parents stated that their children’s sleep patterns were disturbed during the pandemic, and they also had sleep problems. In the study by Amorim et al[29], 55.8% of the parents of children with ASD and 29.6% of the control group reported that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative effect on emotion management. The most difficult areas for parents were expressed as social isolation (41.4%), not being able to spend time outside (13.1%), sudden changes in routines (11.1%), boredom (9.1%) and distance education practices (7.1%). In the quasi-experimental study by Liu et al[36] in two sessions per week for 12 wk, relaxation-muscle exercises, home activities with the child, protection strategies, emotional management, parental stress coping strategies and psychological counseling strategies to cope with the pandemic situation were used. With web-based support, it was found that mothers' stress and anxiety levels decreased in the COVID-19 pandemic period. The parents reported feeling relaxed as the program facilitated the parent-child interaction. In a study conducted in China, it was found that the parents of children with ASD had more deterioration in their diet, less physical exercise, less social support, higher levels of psychological stress, anxiety and depression, and worse coping strategies than the parents of children with normal development[37].

Results regarding the areas where parents of children with ASD need support in the COVID-19 pandemic

Parents stated that they had difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic due to deficiencies in support systems[30]. In the study conducted in Italy, it was reported that parents with children with ASD needed local health service support, supportive training for e-learning and decrease in quarantine restrictions during the COVID-19[30]. In the study conducted in Saudi Arabia, it was found that the support that parents received from their relatives reduced parental stress, fatigue and contributed to improving emotional wellbeing[28]. In the study conducted in Turkey, the majority of parents reported that they could not continue distance education and needed support. In the same study, it was determined that 25% of the parents had minimal anxiety, 29% had mild anxiety, 21% had moderate anxiety, and 25% had severe anxiety according to the Beck Anxiety Inventory[17].

In the study conducted in Portugal, 13% of the parents stated that they took their children to a specialist psychologist, and 1.5% of them visited emergency health services at the moment of their children's tantrums[29]. In the study conducted in Saudi Arabia, parents reported that their children with ASD mostly experienced problems in maintaining their care skills, coping with tantrums, controlling their negative behaviors and maintaining communication with their children. Additionally, the parents stated that they needed psychological and financial support the most, respectively[34]. In the study conducted in the United States, it was observed that tele-health services were insufficient in meeting the education and treatment needs of the children of parents. In the study, most of the parents of children with ASD stated that they had difficulty coping with the increasing negative behaviors of their children, and distress and stress negatively affected their lives[37].

In the study conducted in Italy, it was found that 19.1% of parents visited a neuropsychiatrist due to the onset of new behavioral problems in their children and feeling helpless[30]. It was stated by 47.4% of the participants that they needed more health services during the pandemic, 30% needed to strengthen their home support systems, and 16.8% needed more state support in quarantine. It was stated by 25% of the parents that one of the parents had to quit their job (26.1% of mothers, 27.5% of fathers) to take care of their children with ASD. The majority of the participants (94%) stated that this situation was financially difficult for them. During the pandemic, only 27.7% of the parents reported that they could get support from local health services. It was specified by 23% of the parents that they had difficulties in regulating the eating behaviors of their children, 31% had difficulties in providing authority to their children, 78.1% had difficulties in making use of spare time, and 75.7% had difficulties in having their children do homework[30].

The coping methods of parents with children with ASD with the COVID-19 pandemic

The parents of children with ASD resorted to various coping methods in the COVID-19 pandemic process. In the study by Bent et al[31], it was found that parents exercised at home, practiced yoga and meditation, read newspapers, cooked meals, talked to their loved ones on online platforms and spent time (bathing, nail care and online shopping) during the pandemic. In the study of Mutluer et al[17], it was reported that parents provided each other with rest breaks when there was more than one adult at home who could take care of the child with ASD. In the study by Amorim et al[29], it was determined that parents frequently talked to their family, friends and colleagues by video, and some of them received support from a therapist. In another study, it was observed that parents received the most support from their families, friends, school guidance services, therapy centers and parent support groups, respectively, during the pandemic process[32]. In the study conducted in Saudi Arabia, most parents reported that they received online counseling and guidance services to deal with the child's behavior at home and tantrums[34]. In another study, 36.2% of parents stated that they communicated with their relatives online, 23.4% received online psychological support, and 6.4% occasionally walked with their children[37].

DISCUSSION

This study is the first systematic review aimed at determining the mental health status of the parents of children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic. The systematic review showed that the difficulties associated with the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affect the mental health of the parents of children with ASD. Restriction of face-to-face education, social activities, and child monitoring during the pandemic process threaten the physical and mental health of children. Parents worldwide are concerned about how to support their children best under these difficult conditions[8-10]. The distinctive features of the diagnosis of ASD put children with ASD and their parents at risk of more adverse effects from the COVID-19 pandemic. Since these children may have difficulties in social communication, they can develop when they are in environments that support their social interactions[38]. Although regular physical activity may provide a calming and regulating effect on children, they lack this opportunity due to the pandemic[8]. Considering all of these effects on children diagnosed with ASD, the inability of parents, who are deprived of support during the pandemic process, to maintain their mental health becomes prominent. Parents often experience mental distress as they postpone their own needs for their children with ASD and their families[21]. Disruption in healthcare support or services is an additional stressor on families with a child or dependent with ASD during an already stressful time because of the COVID-19 pandemic[39]. Restrictive social and economic regulations, discomfort caused by COVID-19, fear of transmission, isolated family life, closure of schools, lack of support programs for parents, loss of loved ones, work from home and the resulting increase in full-time childcare and home responsibility, as well as financial difficulties, are the main problems that parents experience in this process[8,17,28-32,39,40]. There has been a consensus on this issue in the studies included in this systematic review[17,28-37,39].

Sleep problems significantly affect children with ASD[41]. Studies on children with ASD reported that sleep problems lead to symptoms such as social withdrawal, anxiety and depression and behavioral problems such as self-aggression, hyperactivity, aggression and high levels of irritability during the day[42,43]. Another study noted that disruption in the circadian sleep rhythm increased the symptoms of ASD[44]. All of these effects of sleep problems negatively influence parents, causing an increase in the burden of these parents and an increase in their stress levels. In a study, it was determined that the situation of being home during the pandemic process caused sleep problems in children with ASD, and this situation increased the severity of ASD symptoms[45]. In the study conducted in Italy, it was reported that more behavioral problems were observed during the COVID-19 pandemic process, and these problems were associated with sleep[17]. The occurrence of these problems creates a sense of loss of control in parents and increases their stress[45]. All of these changes in the lives of parents and children also hinder the physical and cognitive development of the child. Therefore, it is clear that there is also an increase in parental stress levels during a pandemic that directly affects children's quality of life[46]. In a study, it was reported that, during the COVID-19 pandemic process, the parents of children with ASD experienced higher levels of anxiety about themselves and their children in comparison to the parents of children without neurobehavioral disorders[29,37]. Similarly, in the study by Alhuzimi[28] it was emphasized that the parents of children with ASD have higher stress levels and lower welfare levels. Manning et al[32] stated that children with ASD and their parents experienced high levels of stress during the pandemic process and reported that there were disruptions in their daily life routines. In this process, the issues regarding which they experienced the most stress were related to illness, isolation and materiality[32]. The fear of getting infected in the event of a pandemic is significant in the parents of children with ASD, and this fear increases stress significantly[47]. This was supported by the findings of the study by Manning et al[32] on the COVID-19 pandemic. Although staying at home during the isolation process and the obligation to quarantine are measures taken to reduce the transmission of COVID-19, harmful effects of social isolation on the mental health of children and parents may be observed[48]. This may further increase stress in children diagnosed with ASD and their parents[29,30,32]. Lugo-Marín et al[33] reported that there was an increase in somatization, obsessive behavior, depression, anxiety, hostile behavior, paranoid ideas, phobic anxiety and aggression in parents in 2 mo after the lockdown onset. Interruptions in the care process are an important need in the parents of children with ASD[49] and have an important role in reducing stress for the parents of children with ASD[50]. However, the decrease in the support received from caregivers during the isolation process and the fact that parents have taken on the entirety of the care burden have made it difficult for these parents to cope. Parents had difficulties in regulating their children's eating behaviors, providing authority to their children, making use of spare time and finding activities, and having their children do homework, and they felt lonely[30,34,35]. In the studies included in the systematic review, it was reported that, in order to cope with this situation, parents had rest breaks when there was another adult at home who could take care of their children with ASD[17,31].

An increase in the severity of ASD symptoms in children has an important role in affecting the stress and wellbeing levels of parents[51-54]. The COVID-19 pandemic process have caused more intense and more frequent behavioral problems in children with ASD[30]. In the study by Manning et al[32] one of the studies included in the systematic review, it was reported that the increasing severity in the symptoms of children with ASD along with the pandemic caused an increase in the stress reported by parents. Children who are confined at home exhibit aggressive and problematic behaviors, causing more stress for their parents and making it difficult to cope. In other studies supporting these results, the pandemic and the increasing behavioral changes in children with ASD were found to play a significant role in the increase of stress in parents[17,30]. Parental stress also reportedly had an effect on emotional well-being[28]. In this sense, there has been a consensus that there is a lack of support for children and parents.

The positive attitude of parents during the COVID-19 pandemic is necessary for them to manage their stress and also control their children's behavior at home[34]. Pottie and Ingram[55] pointed out the importance of social support in helping a parent with a child with ASD cope with stress and raise their mood. All kinds of support from the community and from parents who experience similar situations facilitate the home care processes of children with ASD and their parents[56]. For this reason, during the pandemic, it is necessary to maintain contact in online environments with all individuals and institutions that parents can receive support from such as other parents, teachers, therapists and health professionals who experience similar situations[12]. In a qualitative study, parents stated that, although they could not get together with other parents who were in the same situation during the pandemic, they supported each other in home care through groups established via online messaging applications and mentioned how this helped them[57]. Similarly, in the studies included in the systematic review, parents reported that they frequently made video calls with their families and friends[29,31]. Althiabi[34] found that parents sought support from teachers, family members and therapists to take care of their children with ASD during the pandemic outbreak. Bent et al[31] stated in their study that it is important to seek help from friends, family, co-workers, therapists and healthcare professionals, as parents must remain strong for their families and children. With the closure of schools, parents are struggling to find different activities at home to support the development of their children with ASD and prevent their symptoms from appearing[57]. In the studies included in the systematic review[30,31,34,35], in accordance with the literature, parents stated that they sought daily activities and events that their children enjoyed. All family members including parents who leave their jobs or work from home due to the pandemic and children whose schools are closed are at home all together. In this process, the support of all family members for each other in the care of the child with ASD also provides a significant reduction in their burden of care[57].

Children diagnosed with ASD can only survive the pandemic with healthy parents. Therefore, parents should take care of their health, both for themselves and their children. Firstly, parents should not disrupt their physical care with adequate nutrition and rest and accept the emotional burden they experience. They should practice spiritual self-care by planning an activity they enjoy. Parents should be encouraged to plan activities they can do with their children in the home environment. Moreover, they should be encouraged to seek help from healthcare professionals when they feel they have mental problems that they cannot cope with[21]. Consistent with the literature, Bent et al[31] reported that parents spend time with activities such as bathing, nail care and online shopping as a method of coping with stress. In the qualitative study, the parents stated that they used methods such as walking, cycling, yoga, meditation, reading a newspaper and praying to cope with stress during the COVID-19 pandemic[31]. With the web-based support program prepared by Liu et al[36] relaxation-muscle exercises, home activities with the child, protection strategies, emotional management, parental stress coping strategies and psychological counseling strategies to cope with the pandemic situation were implemented. Their study stated that mothers' stress and anxiety levels decreased, and parents reported feeling relaxed as the program facilitated parent-child interaction.

Limitations

The limitations of this study were that studies whose full texts were not available and those published in languages other than the English language were not included in the systematic review, 12 databases were searched, and the gray literature was not screened. Since the pandemic has only the last year, studies in the field are limited. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, as the systematic review was performed with a limited number of descriptive studies (twelve articles) with lower levels of evidence.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected the mental health of children with ASD and their parents. While many factors play a role in increasing the stress levels of parents, stress may also lead to different problems. In this case, it is possible for children with ASD to continue their lives in a healthy way with mentally healthy parents. In the systematic review, it was concluded that parents with children with ASD had difficulty with their children being at home all day long and financial difficulties as they had to quit their jobs. The parents were also able to devote less time to themselves during this process, and their stress and anxiety levels increased. During the pandemic where face-to-face services are interrupted, governments and relevant institutions should provide support for parents with children with ASD, and institutions that provide support should also work to improve the quality of the support they provide. In this process, it may be recommended to research new ways such as online health monitoring, online diagnosis systems, support groups for children and parents, increased tele-health services, tele-therapies and e-health support. Additionally, after the restrictions imposed by the pandemic are removed, it is important to support children with ASD and their parents while they are getting used to their social lives. Support services, such as counseling and helplines, may be created to help parents share their concerns and receive assistance in dealing with specific situations. Parents should be evaluated in terms of mental health, and professional help should be provided for individuals who need support.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Although staying at home prevents the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), this poses a number of challenges, especially for children with special needs such as autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and their parents. The parents of children with ASD participate in special education practices that involve physical activity in order to cope with the behavioral, cognitive and mental problems of their children. However, during COVID-19 pandemic, this process was disrupted, and the mental health of the parents was affected.

Research motivation

Although there were many studies on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in the literature search, it was observed that there was very limited information on mental health effects on the parents of children with ASD, and there was no systematic review on this topic.

Research objectives

In this systematic review, it is aimed to determine the mental health status of the parents of children with ASD in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research methods

Articles in English, which could be accessed in full text without any limitation of publication year and country, were included in the study. The systematic review was conducted according to the PICOS strategy (Participants: The parents of children with ASD; Interventions: Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health; Comparators: The parents of children without ASD; Main outcomes: Anxiety, stress, difficulty in coping, loneliness, inadequacy of support systems, social isolation, change in routines and financial difficulties; Additional outcomes: Exercise at home, practicing yoga and meditation, reading newspapers, receiving support from a therapist, cooking meals, talking to their loved ones on online platforms during the pandemic. These results have been reported in studies and included and presented in this systematic review. Study design: Quantitative/qualitative studies). The search results were reached by browsing the Web of Science, PubMed (including MEDLINE), Cochrane, Scopus, Science direct and Google Scholar databases using the keywords COVID-19 AND (“autism” OR “autistic” OR “autism spectrum disorder”) AND parent AND (“mental health” OR “anxiety” OR “stress”). The list of the references of the included studies was reviewed to access additional studies.

Research results

The systematic review was conducted according to the PICOS strategy, and a total of 12 studies were included in a quantitative and qualitative design. The studies have revealed that parents are negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. It was reported that the parents of children with ASD had increased anxiety and stress during the pandemic, children became aggressive as their routines changed, and the parents had difficulty coping with this process. During the pandemic, the parents met with their friends via online platforms, practiced yoga and meditation, the spouses provided rest breaks to each other and received support from therapists.

Research conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected the mental health of children with ASD and their parents. It may be recommended to plan more interventions that will positively affect the mental health of parents and support them.

Research perspectives

Given the uncertainty of how long the COVID-19 pandemic will last, it is important to conduct a large number of descriptive and interventional studies on the mental health of parents with children who have ASD. In this systematic review, it was revealed that the number of studies on this topic is quite limited. It is thought that this systematic review will form the basis for future studies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: February 7, 2021

First decision: March 16, 2021

Article in press: June 3, 2021

Specialty type: Psychology

Country/Territory of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Afzal MS, Saad K S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LYT

Contributor Information

Büşra Yılmaz, Department of Women's Health and Gynecologic Nursing, Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Istanbul 34381, Turkey.

Merve Azak, Department of Pediatric Nursing, Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Istanbul University- Cerrahpasa, Istanbul 34381, Turkey. merve.azak@iuc.edu.tr.

Nevin Şahin, Department of Women's Health and Gynecologic Nursing, Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa, Istanbul 34381, Turkey.

References

- 1.Druss BG. Addressing the COVID-19 Pandemic in Populations With Serious Mental Illness. JAMA Psychiatry . 2020;77:891–892. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Autism spectrum disorders. 2019. [cited 20 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders .

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. 2020. [cited 26 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html .

- 5.James CV, Moonesinghe R, Wilson-Frederick SM, Hall JE, Penman-Aguilar A, Bouye K. Racial/Ethnic Health Disparities Among Rural Adults-United States, 2012-2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2017; 66: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. 2020 May 11. [cited 23 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-may-2020 .

- 7.Güner R, Hasanoğlu I, Aktaş F. COVID-19: Prevention and control measures in community. Turk J Med Sci . 2020;50:571–577. doi: 10.3906/sag-2004-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellomo TR, Prasad S, Munzer T, Laventhal N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with autism spectrum disorders. J Pediatr Rehabil Med . 2020;13:349–354. doi: 10.3233/PRM-200740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.den Houting J. Stepping Out of Isolation: Autistic People and COVID-19. Autism in Adulthood . 2020;2:1–3. doi: 10.1089/aut.2020.29012.jdh. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu JJ, Bao Y, Huang X, Shi J, Lu L. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health . 2020;4:347–349. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, Huang Y, Miao J, Yang X, Zhu G. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord . 2020;275:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narzisi A. Handle the Autism Spectrum Condition During Coronavirus (COVID-19) Stay At Home period: Ten Tips for Helping Parents and Caregivers of Young Children. Brain Sci . 2020;10:1–4. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10040207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puts NA, Wodka EL, Tommerdahl M, Mostofsky SH, Edden RA. Impaired tactile processing in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Neurophysiol . 2014;111:1803–1811. doi: 10.1152/jn.00890.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sivaraman M, Virues-Ortega J, Roeyers H. Telehealth mask wearing training for children with autism during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Appl Behav Anal . 2021;54:70–86. doi: 10.1002/jaba.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonis S. Stress and Parents of Children with Autism: A Review of Literature. Issues Ment Health Nurs . 2016;37:153–163. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1116030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U, St Peter C. Access to services, quality of care, and family impact for children with autism, other developmental disabilities, and other mental health conditions. Autism . 2014;18:815–826. doi: 10.1177/1362361313512902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mutluer T, Doenyas C, Aslan Genc H. Behavioral Implications of the Covid-19 Process for Autism Spectrum Disorder, and Individuals' Comprehension of and Reactions to the Pandemic Conditions. Front Psychiatry . 2020;11:561882. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.561882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akçay E, Başgül ŞS. Pandemic and Children with Special Needs/At Risk. Turkiye Klinikleri . 2020:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juneja M, Gupta A. Managing Children with Special Needs in COVID-19 Times. Indian Pediatr . 2020;57:971. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-2009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiraoka D, Tomoda A. Relationship between parenting stress and school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci . 2020;74:497–498. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim T, Tan MY, Aishworiya R, Kang YQ. Autism Spectrum Disorder and COVID-19: Helping Caregivers Navigate the Pandemic. Ann Acad Med Singap . 2020;49:384–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP Offers Parent Tips and Resources for Dealing With Covid-19 and Its Stresses. 2020. [cited 26 January 2021]. Available from: https://services.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2020/aap-offers-parent-tips-and-resources-for-dealing-with-covid-19-and-its-stresses/

- 23.United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund. Explore the parenting tips. 2020. [cited 25 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/coronavirus/covid-19-parenting-tips .

- 24.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: Advocacy. 2020. [cited 26 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/healthy-parenting .

- 25.Mackintosh VH, Goin-Kochel RP, Myers BJ. “What do you like/dislike about the treatments you’re currently using? Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl . 2012;27:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg . 2014;12:1495–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojtkova M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil . 2012;4:409–429. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alhuzimi T. Stress and emotional wellbeing of parents due to change in routine for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) at home during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Res Dev Disabil . 2021;108:103822. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amorim R, Catarino S, Miragaia P, Ferreras C, Viana V, Guardiano M. The impact of COVID-19 on children with autism spectrum disorder. Rev Neurol . 2020;71:285–291. doi: 10.33588/rn.7108.2020381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colizzi M, Sironi E, Antonini F, Ciceri ML, Bovo C, Zoccante L. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in Autism Spectrum Disorder: An online parent survey. Brain Sci . 2020;10:341–357. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10060341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bent S, Hossain B, Chen Y, Widjaja F, Breard M, Hendren R. The experience of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis. 2020 Preprint. Available from: Research square.

- 32.Manning J, Billian J, Matson J, Allen C, Soares N. Perceptions of families of individuals with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 crisis. J Autism Dev Disord . 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04760-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lugo-Marín J, Gisbert-Gustemps L, Setien-Ramos I, Español-Martín G, Ibañez-Jimenez P, Forner-Puntonet M, Arteaga-Henríquez G, Soriano-Día A, Duque-Yemail JD, Ramos-Quiroga JA. COVID-19 pandemic effects in people with Autism Spectrum Disorder and their caregivers: Evaluation of social distancing and lockdown impact on mental health and general status. Res Autism Spectr Disord . 2021;83:101757. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Althiabi Y. Attitude, anxiety and perceived mental health care needs among parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19 pandemic. Res Dev Disabil . 2021;111:103873. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mumbardó-Adam C, Barnet-López S, Balboni G. How have youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder managed quarantine derived from COVID-19 pandemic? Res Dev Disabil . 2021;110:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu G, Wang S, Liao J, Ou P, Huang L, Xie N, He Y, Lin J, He HG, Hu R. The efficacy of WeChat-Based parenting training on the psychological well-being of mothers with children with autism during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Quasi-experimental study. JMIR Ment Health . 2021;8:e23917. doi: 10.2196/23917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L, Li D, Pan S, Zhai J, Xia W, Sun C, Zou M. The relationship between 2019-nCoV and psychological distress among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Global Health . 2021;17:23–37. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00674-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM. Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics 2020; 145: e20193447. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White LC, Law JK, Daniels AM, Toroney J, Vernoia B, Xiao S SPARK Consortium. Feliciano P, Chung WK. Brief Report: Impact of COVID-19 on individuals with ASD and their caregivers: A perspective from the SPARK cohort. J Autism Dev Disord . 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04816-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang G, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Zhang J, Jiang F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet . 2020;395:945–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sivertsen B, Posserud MB, Gillberg C, Lundervold AJ, Hysing M. Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum problems: a longitudinal population-based study. Autism . 2012;16:139–150. doi: 10.1177/1362361311404255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henderson JA, Barry TD, Bader SH, Jordan SS. The relation among sleep, routines, and externalizing behavior in children with an autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord . 2011;5:758–767. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson CR. Sleep problems in children with mental retardation and autism. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am . 1996;5:673–684. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carmassi C, Palagini L, Caruso D, Masci I, Nobili L, Vita A, Dell'Osso L. Systematic review of sleep disturbances and circadian sleep desynchronization in autism spectrum disorder: toward an integrative model of a self-reinforcing loop. Front Psychiatry . 2019;10:366–401. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Türkoğlu S, Uçar HN, Çetin FH, Güler HA, Tezcan ME. The relationship between chronotype, sleep, and autism symptom severity in children with ASD in COVID-19 home confinement period. Chronobiol Int . 2020;37:1207–1213. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1792485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2020;17:1–25. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiss JA, Wingsiong A, Lunsky Y. Defining crisis in families of individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Autism . 2014;18:985–995. doi: 10.1177/1362361313508024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, Turner V, Turnbull S, Valtorta N, Caan W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health . 2017;152:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindly OJ, Chavez AE, Zuckerman KE. Unmet health services needs among US children with developmental disabilities: Associations with family impact and child functioning. J Dev Behav Pediatr . 2016;37:712–723. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harper A, Taylor Dyches T, Harper J, Olsen Roper S, South M. Respite care, marital quality, and stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord . 2013;43:2604–2616. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osborne LA, Reed P. The relationship between parenting stress and behavior problems of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Except Child . 2009;76:54–73. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall HR, Graff JC. The relationships among adaptive behaviors of children with autism, family support, parenting stress, and coping. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs . 2011;34:4–25. doi: 10.3109/01460862.2011.555270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ingersoll B, Hambrick DZ. The relationship between the broader autism phenotype, child severity, and stress and depression in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord . 2011;5:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rivard M, Terroux A, Parent-Boursier C, Mercier C. Determinants of stress in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord . 2014;44:1609–1620. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-2028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pottie CG, Ingram KM. Daily stress, coping, and well-being in parents of children with autism: a multilevel modeling approach. J Fam Psychol . 2008;22:855–864. doi: 10.1037/a0013604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arora T. Elective home education and special educational needs. J Res Spec Educ Needs . 2006;6:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Majoko T, Dudu A. Parents’ strategies for home educating their children with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 period in Zimbabwe. Int J Dev Disabil . 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2020.1803025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]