Abstract

Adult pancreatoblastoma is an exceptionally rare malignant tumour of the pancreas that mimics other solid cellular neoplasms of the pancreas, which may pose diagnostic difficulties. Because of its rarity, little is known about its clinical and pathologic features. This article reviews the clinical and pathologic features of pancreatoblastoma in adults including differential diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Although pancreatoblastoma commonly occurs in childhood, there have now been more than 70 adult pancreatoblastomas described in the literature. There is a slight male predominance. There are no symptoms unique to pancreatoblastomas and adult patients are frequently symptomatic. The most common presenting symptom is abdominal pain. Grossly, the tumours are often large and well-circumscribed. Microscopically, pancreatoblastomas are composed of neoplastic cells with predominantly acinar differentiation and characteristic squamoid nests. These tumours are positive for trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase, and BCL10. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 11p is the most common molecular alteration in pancreatoblastomas. Adult pancreatoblastomas are aggressive tumours with frequent local invasion, recurrence, and distant metastasis. Treatment consists of surgical resection. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy may have a role in the treatment of recurrent, residual, unresectable, and metastatic disease. It is important to distinguish pancreatoblastomas from morphological mimics such as acinar cell carcinomas, solid pseudopapillary neoplasms, and pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms.

Keywords: Pancreas, Adult pancreatoblastoma, Pancreatic cancer, Solid pancreatic mass, Non-ductal pancreatic tumours

Core Tip: Adult pancreatoblastomas are extremely rare tumours of the pancreas. They are composed of neoplastic cells with multiple lines of differentiation and characteristic squamoid nests. They mimic other neoplasms of the pancreas, which may give rise to diagnostic difficulties. This article provides an up-to-date review of the clinical and pathologic features of pancreatoblastoma in adults, including differential diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatoblastoma is a malignant epithelial neoplasm of the pancreas composed of cells with predominantly acinar differentiation and characteristic squamoid nests. Neuroendocrine, ductal and less commonly, mesenchymal differentiation can be seen but are often less extensive[1-3]. Less than 1% of pancreatic neoplasms are pancreatoblastomas[4,5]. Pancreatoblastoma commonly occurs in childhood, accounting for 25% of pancreatic neoplasms occurring in the first decade of life, with a mean age of approximately 4 years[1].

Adult pancreatoblastoma is extremely rare. Hence, little is known about its clinical and pathologic features. Furthermore, pre-operative diagnosis can be quite challenging because of the considerable overlap with other cellular neoplasms of the pancreas.

This article provides an up-to-date review of the clinical and pathologic features of pancreatoblastoma in adults, including cytology, molecular pathology, differential diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Adult pancreatoblastomas are exceptionally rare. To date, only 74 adult pancreatoblastomas have been reported in the literature, mostly in the form of isolated case reports and small series[6-10]. The mean age at diagnosis is 41 years (range, 18-78 years). There is a slight male predilection, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.2:1.

AETIOLOGY

The aetiology is unknown. Although most tumours are sporadic[11-15], few adult pancreatoblastomas have been described in the setting of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)[8,9]. Rare cases in children have been associated with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome[16,17].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Most patients are symptomatic, with very few cases discovered incidentally during routine examination and imaging[4,10,11]. There are no symptoms unique to pancreatoblastomas. The most common presenting symptom is abdominal pain[2]. Other clinical features include abdominal mass, weight loss, nausea, jaundice, and diarrhoea[6,14,15,18,19]. Rarely, patients may present with upper gastrointestinal bleeding[12].

Most adult pancreatoblastomas arise in the head of the pancreas. Of the 74 adult pancreatoblastomas described in the literature, localization data were available in 69 cases. The head of the pancreas was involved in 52.1% of cases (36 patients); the tail in 30.4% of cases (21 patients); the body in 14.5% of cases (10 patients); the body and tail in 1.5% of cases (1 patient); and the ampulla of vater in 1.5% of cases (1 patient).

Elevated serum levels of CA19-9[14,15] as well as corticotropin releasing hormone secretion[20] rarely occurs in adult pancreatoblastomas. Serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) is elevated in some pancreatoblastomas[4,7,13,21,22]. In addition, AFP may be detected immunohistochemically in tumours associated with elevated serum levels of AFP[3,4,22]. Serum AFP is frequently elevated in children[4,10,13] with levels often in excess of 1000 μg/L[3]. In contrast, AFP is not consistently elevated in adults[2,7,10,13]. When present, elevated serum AFP has been used as a marker of tumour recurrence or disease progression because AFP levels should decrease or normalize with successful treatment[7,13,21].

It is important to note that elevated AFP is not specific for pancreatoblastoma in a patient with a pancreatic mass. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas[23] and pancreatic acinar cell carcinomas[24,25] have been associated with elevated serum AFP. Furthermore, AFP is widely used as a tumour marker for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, the limitations of AFP in detecting HCC includes the poor sensitivity in detecting small tumours and elevated levels of AFP in patients with chronic liver disease without HCC. To overcome this limitation, the Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive AFP (AFP-L3) has been found to be highly specific and useful not only for early detection of HCC but also for predicting the risk of development of HCC in patients with chronic liver disease[26,27]. However, AFP-L3 or other isoforms of AFP are yet to be extensively studied in pancreatoblastomas.

Malignant behaviour is prominent in adult pancreatoblastomas. Approximately 59% of adult patients with pancreatoblastoma develop metastases at the time of diagnosis or afterwards in the course of the disease. The liver is the most common site of metastasis[2,12,15,28] followed by lymph nodes[4,5,29], and lung[4,5,7,15]. Chest wall[5], breast[15], bone[30], and brain metastases[31] are extremely rare. Tumours can invade adjacent structures such as the duodenum, spleen, common bile duct, portal vein, and superior mesenteric vessels[2,4,7,19,29].

IMAGING

There are no significant differences in the imaging findings of adult and paediatric patients[2,32]. Pancreatoblastomas are large well-defined heterogenous masses with low to intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Enhancement is a common feature on contrast-enhanced computed tomography images and may be present on magnetic resonance imaging. Calcifications when present may be rim-like or clustered[19,33]. On ultrasound, pancreatoblastomas are well-demarcated solid masses inseparable from the pancreas with mixed echogenicity[33].

CYTOLOGY

Fine needle aspiration specimens are composed of cellular singly dispersed and/or clustered polygonal cells. The cells have round to oval nuclei with fine chromatin pattern, small indistinct nucleoli, and moderate amounts of amphophilic or eosinophilic cytoplasm[3,9]. Squamoid nests or corpuscles are best appreciated in cell block preparations. They are composed of plump epithelioid cells with abundant cytoplasm[7,9].

PATHOLOGY

Grossly, the tumours are solitary, solid, well-circumscribed, and often encapsulated. Pancreatoblastomas are usually large, averaging 8 cm in diameter (range, 1.8–30 cm)[2,3,6]. On cut section, the tumours have yellow to tan fleshy lobules separated by dense fibrous bands. Foci of haemorrhage and necrosis may be present. Rarely, pancreatoblastomas may undergo cystic change or show gross extension into the adjacent peripancreatic soft tissue[4].

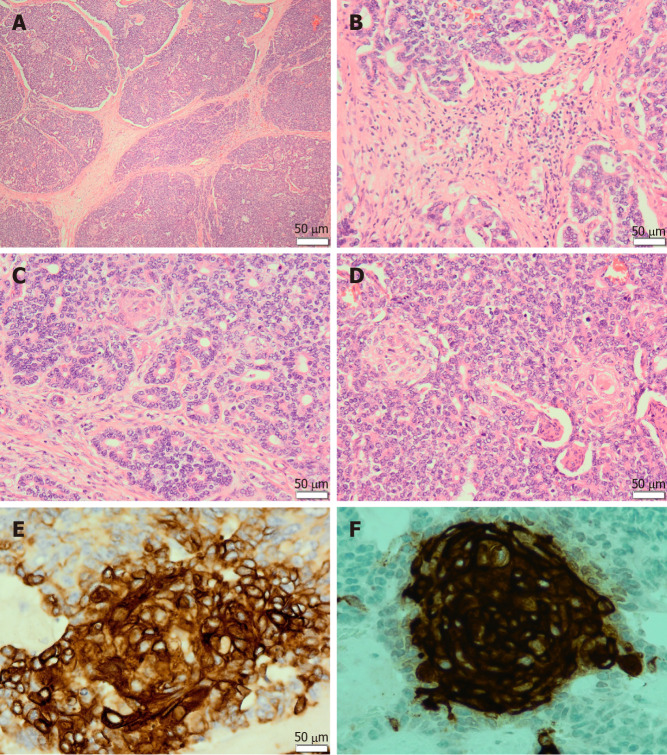

Microscopically, pancreatoblastomas are composed of cellular well-delineated lobules separated by dense fibrous bands, often imparting a geographic low power appearance (Figure 1A). The dense fibrous bands between the lobules are composed of spindled cells with varying amounts of collagen (Figure 1B). Tumours predominantly show acinar differentiation; however, ductal, neuroendocrine and less commonly, mesenchymal differentiation may be present[1-3]. Solid areas with sheets of cells often alternate with areas with acinar differentiation. The acinar units comprise small cells with granular cytoplasm arranged around central lumina (Figure 1C). The cells have round to oval nuclei with single prominent nucleoli[1,3,4].

Figure 1.

Pancreatoblastoma. A: The tumour is composed of lobules separated by dense fibrous bands, imparting a geographic low power appearance [Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, 40 ×]; B: The dense fibrous bands between the lobules are composed of spindled cells with varying amounts of collagen (H&E staining, 200 ×); C: The tumour predominantly shows acinar differentiation. The acinar units are composed of neoplastic cells arranged around central lumina (H&E staining, 200 ×); D: The tumour shows characteristic squamoid nests. Squamoid nests are large islands of plump epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (H&E staining, 200 ×); E: The squamoid nests are immunoreactive for AE1/AE3 (400 ×); F: The tumour shows immunolabeling for CD10 limited to the squamoid nests (400 ×).

The defining histological feature of pancreatoblastoma is the squamoid nests. Squamoid nests vary from large islands of plump epithelioid cells to whorled nests of spindled cells showing mild to frank keratinization. The cells of the squamoid nests are often distinct from surrounding acinar cells. They are larger than surrounding cells with abundant eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm and without cytological atypia (Figure 1D). The amount of squamoid nests can vary both within and between tumours.

Pancreatoblastomas typically express trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase, and BCL10. The granules are periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive and resistant to diastase (PASD)[3,4]. Focal expression of chromogranin A and synaptophysin may be present. Squamoid nests may be positive for EMA, AE1/AE3 (Figure 1E) or CD10 (Figure 1F). In addition, patchy nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin may be seen.

The staging of pancreatoblastoma follows the TNM classification of carcinoma of the exocrine pancreas[3].

MOLECULAR PATHOLOGY

Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 11p is the most common molecular alteration in pancreatoblastomas, occurring in 86% of cases. Molecular alterations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)/β-catenin signalling pathway have also been identified in 67% of pancreatoblastomas, including biallelic inactivation of the APC gene and activating mutations of CTNNB1 (β-catenin) gene. Biallelic inactivation of the APC gene has been identified in a patient with pancreatoblastoma arising in the setting of FAP[8]. Interestingly, aberrations in the APC/β-catenin pathway have been implicated in the development of hepatoblastoma, a tumour associated with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome[8,34].

Recent RNA sequencing studies have identified molecular aberrations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) signalling pathway. These include somatic FGFR1 mutation, FGFR2 gene rearrangement, and a high mRNA expression of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors 1, 3 and 4 as well as of their ligands, FGF3 and FGF4[18].

The most frequent recurrent molecular alterations identified in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, including mutations in KRAS, TP53, and CDKN2A/p16 genes, are typically lacking in pancreatoblastomas, suggesting that pancreatoblastomas are genetically distinct from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas[8]. Loss of SMAD4/DPC4 expression is rare in pancreatoblastomas[8,35].

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Pancreatoblastomas are distinct from the more common pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, and it is generally easy to differentiate them on the basis of morphology. The differential diagnosis of pancreatoblastoma includes solid cellular neoplasms of the pancreas such as acinar cell carcinomas, solid pseudopapillary neoplasms, and pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs).

There are a number of clinical and morphological similarities between acinar cell carcinomas and pancreatoblastomas. Acinar cell carcinomas are rare, accounting for 1%-2% of pancreatic neoplasms in adults and about 15% in children[1]. Acinar cell carcinomas have a poor prognosis, with a mean survival of 18-24 mo and a 3-year survival rate of 26%[36,37]. Both acinar cell carcinomas and pancreatoblastomas present with non-specific clinical symptoms such as abdominal pain, abdominal mass, and weight loss. In addition, both tumours are cellular neoplasms with acinar differentiation. Neoplastic cells are often polarized around central lumina. The cells contain PASD-positive cytoplasmic granules. Furthermore, acinar cell carcinomas and pancreatoblastomas are typically immunoreactive for trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase, and BCL10. However, the distinguishing feature is the characteristic squamoid nests seen in pancreatoblastomas.

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas is a low-grade malignant neoplasm characterized by cells with solid and pseudopapillary growth patterns. Approximately 1%-2% of pancreatic neoplasms are solid pseudopapillary neoplasms, and they frequently occur in girls and young women[3]. Microscopically, solid pseudopapillary neoplasms are composed of poorly cohesive monomorphic epithelial cells arranged around hyalinized fibrovascular stalks, forming solid and pseudopapillary structures. The nuclei frequently show indentations, clefts, and grooves. Typically, these tumours contain scattered PASD-positive hyaline globules, foamy histiocytes, cholesterol clefts, and foreign body giant cells[1]. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms are positive for nuclear and/or cytoplasmic β-catenin, CD56, CD10, vimentin, and cyclin D1. Unlike pancreatoblastomas, the prognosis of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas is excellent.

PanNENs constitute about 2%-5% of pancreatic neoplasms[3]. They are architecturally diverse and can be confused with pancreatoblastomas. In addition, pancreatoblastomas can focally express neuroendocrine markers. In contrast, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours are composed of cells with amphophilic to eosinophilic cytoplasm and the nuclei have characteristic salt and pepper chromatin. Typically, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours strongly express synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and CD56. Features that favour a diagnosis of pancreatoblastoma include predominant acinar differentiation, squamoid nests, PASD-positive cytoplasmic granules, and expression of trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase, and BCL10.

OUTCOME

There are no established treatment guidelines for pancreatoblastoma. Treatment consists of surgical resection with a variable combination of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Treatment and outcome of adult pancreatoblastoma

|

Ref.

|

Treatment

|

Follow-up (mo)

|

Outcome

|

| Charlton-Ouw et al[39], 2008 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT | 60 | NED |

| Levey and Banner[40], 1996 | Surgical resection | 4 | DOD |

| Palosaari et al[29], 1986 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT | 15 | AWD |

| Rajpal et al[13], 2006 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy | 17 | DOD |

| Dunn and Longnecker[41], 1995 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy | 11 | DFUD |

| Zhu et al[42], 2005 | Chemotherapy | 9 | AWD |

| Du et al[14], 2003 | Surgical resection | 6 | NED |

| Hoorens et al[43], 1994 | Surgical resection | 30 | NED |

| Robin et al[44], 1997 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy | 7 | DOD |

| Gruppioni et al[45], 2002 | Surgical resection | 10 | NED |

| Benoist et al[12], 2001 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy | 36 | NED |

| Mumme et al[46], 2001 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT | 9 | DOD |

| Salman et al[5], 2013 | Surgical resection | 30 | NED |

| Salman et al[5], 2013 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT | 41 | NED |

| Salman et al[5], 2013 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, ablation of liver mets | 51 | DOD |

| Hayasaki et al[47], 1999 | Surgical resection | 15 | NED |

| Sheng et al[48], 2005 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT, TACE | 26 | DOD |

| Balasundaram et al[15], 2012 | Chemotherapy | 1 | DFUD |

| Klimstra et al[4], 1995 | Surgical resection | 5 | NED |

| Klimstra et al[4], 1995 | None | 5 | DOD |

| Klimstra et al[4], 1995 | Surgical resection | 10 | DOD |

| Klimstra et al[4], 1995 | Surgical resection | 15 | NED |

| Klimstra et al[4], 1995 | Chemotherapy, RT | 38 | DOD |

| Rosebrook et al[32], 2005 | Surgical resection | NA | NA |

| Montemarano et al[19], 2000 | Surgical resection | NA | NA |

| Abraham et al[8], 2001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Abraham et al[8], 2001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Boix et al[20], 2010 | Surgical resection | 3 | DOD |

| Pitman and Faquin[7], 2004 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT | 108 | AWD |

| Savastano et al[49], 2009 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT | NA | NED |

| Cavallini et al[10], 2009 | Surgical resection | 51 | NED |

| Cavallini et al[10], 2009 | Surgical resection | 15 | NED |

| Hammer and Owens[28], 2013 | Surgical resection | NA | NA |

| Zhang et al[50], 2015 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy | NA | NED |

| Ohike et al[51], 2008 | Surgical resection | 108 | NED |

| Chen et al[52], 2018 | Hepatic transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) | 48 | DOD |

| Yamaguchi et al[53], 2018 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy | 13 | DOD |

| Nunes et al[54], 2018 | Palliative care | 3 | DOD |

| Vilaverde et al[55], 2016 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy | 12 | DOD |

| Zouros et al[30], 2015 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT | 13 | DOD |

| Kuxhaus et al[56], 2005 | NA | NA | NA |

| Comper et al[57], 2009 | Surgical resection | NA | NA |

| Comper et al[57], 2009 | Surgical resection | NA | NA |

| Gringeri et al[58], 2012 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, stereotactic RT | 44 | NED |

| Redelman et al[59], 2014 | Surgical resection | NA | NA |

| Tabusso et al[6], 2017 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT | 10 | AWD |

| Tabusso et al[6], 2017 | Surgical resection | 15 | NED |

| Liu et al[60], 2020 | Surgical resection | 24 | NED |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 72.2 | DOD |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 17.9 | AWD |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 3.6 | DOD |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 85 | DOD |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 143.7 | DOD |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 13.6 | NED |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 0.8 | DOD |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 6.5 | NED |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 348 | AWD |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 88 | AWD |

| Reid et al[9], 2019 | NA | 91 | AWD |

| Terino et al[61], 2018 | Chemotherapy | NA | NA |

| Morrissey et al[62], 2020 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy | 2 | NED |

| Berger et al[8], 2020 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy | 18 | DOD |

| Berger et al[8], 2020 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, RT, splenectomy | 24 | DOD |

| Berger et al[8], 2020 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, RT | 17 | DOD |

| Berger et al[8], 2020 | Chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy | 15 | DOD |

| Zhang et al[11], 2020 | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang et al[11], 2020 | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang et al[11], 2020 | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang et al[11], 2020 | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang et al[11], 2020 | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang et al[11], 2020 | NA | NA | NA |

| Zhang et al[11], 2020 | NA | NA | NA |

| Elghawy et al[31], 2021 | Chemotherapy, autologous hematopoetic cell transplantation | 57 | AWD |

| Snyder et al[63], 2020 | Surgical resection, chemotherapy, GKRS | 63 | NED |

RT: Radiotherapy; GKRS: Gamma knife radiosurgery; DOD: Died of disease; AWD: Alive with disease; DFUD: Died from unrelated disease; NED: No evidence of disease; NA: Not available.

Of the 74 cases of adult pancreatoblastomas described in the literature, outcome data were available in 57 cases. The mean follow-up time was 36 mo (range, 0.8-348 mo). Forty-two percent (24 cases) of patients died of the disease at a mean interval of 27 mo (range, 0.8-143.7 mo); 4% (2 cases) of patients died from unrelated causes (cerebral haemorrhage and pulmonary artery embolus); 16% (9 cases) of patients were alive with disease; and 38% (22 cases) of patients had no evidence of disease (Table 1).

Although long-term survival has been observed in some adults, the prognosis of pancreatoblastoma in children may be more favourable than in adults[1,4,13,14]. Poor prognostic factors include the presence of metastases and unresectable disease[3]. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy may have a role in the treatment of recurrent, residual, unresectable and metastatic disease[3,38]. Because of the tendency for recurrence and metastasis, long-term follow-up is advised for these patients[38].

CONCLUSION

In summary, adult pancreatoblastomas are extremely rare. Although these tumours typically occur in children, pancreatoblastomas should be considered in the differential diagnosis of solid pancreatic tumours in adults. An appreciation of distinctive squamoid nests, predominant acinar differentiation, and expression of trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase, and BCL10 are important for the accurate diagnosis of pancreatoblastomas. These tumours are aggressive with frequent local invasion, recurrence, and distant metastasis. They must be distinguished from morphological mimics. There is a need for further research to better understand the molecular drivers of pancreatoblastomas, identify druggable molecular targets, and, most importantly, improve patient care.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The author declares no conflict of interest for this article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: January 30, 2021.

First decision: March 6, 2021

Article in press: June 22, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kankaria J, Sergi C S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

References

- 1.Klimstra DS. Nonductal neoplasms of the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20 Suppl 1:S94–S112. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omiyale AO. Clinicopathological review of pancreatoblastoma in adults. Gland Surg. 2015;4:322–328. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2015.04.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carneiro F, Chan JKC, Cheung NYA. (Eds): WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System. 5th edition. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klimstra DS, Wenig BM, Adair CF, Heffess CS. Pancreatoblastoma. A clinicopathologic study and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1371–1389. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salman B, Brat G, Yoon YS, Hruban RH, Singhi AD, Fishman EK, Herman JM, Wolfgang CL. The diagnosis and surgical treatment of pancreatoblastoma in adults: a case series and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:2153–2161. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabusso FY, Placencia RMF, Figueroa ER. Two cases of adult pancreatoblastoma: an infrequent differential diagnosis. JOP 2017. [cited 10 January 2021]. Available from: https://pancreas.imedpub.com/two-cases-of-adult-pancreatoblastoma-an-infrequent-differential-diagnosis.php?aid=19308 .

- 7.Pitman MB, Faquin WC. The fine-needle aspiration biopsy cytology of pancreatoblastoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:402–406. doi: 10.1002/dc.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham SC, Wu TT, Klimstra DS, Finn LS, Lee JH, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Hruban RH. Distinctive molecular genetic alterations in sporadic and familial adenomatous polyposis-associated pancreatoblastomas : frequent alterations in the APC/beta-catenin pathway and chromosome 11p. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1619–1627. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid MD, Bhattarai S, Graham RP, Pehlivanoglu B, Sigel CS, Shi J, Saqi A, Shirazi M, Xue Y, Basturk O, Adsay V. Pancreatoblastoma: Cytologic and histologic analysis of 12 adult cases reveals helpful criteria in their diagnosis and distinction from common mimics. Cancer Cytopathol. 2019;127:708–719. doi: 10.1002/cncy.22187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavallini A, Falconi M, Bortesi L, Crippa S, Barugola G, Butturini G. Pancreatoblastoma in adults: a review of the literature. Pancreatology. 2009;9:73–80. doi: 10.1159/000178877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Ni SJ, Wang XH, Huang D, Tang W. Adult pancreatoblastoma: clinical features and Imaging findings. Sci Rep. 2020;10:11285. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benoist S, Penna C, Julié C, Malafosse R, Rougier P, Nordlinger B. Prolonged survival after resection of pancreatoblastoma and synchronous liver metastases in an adult. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1340–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajpal S, Warren RS, Alexander M, Yeh BM, Grenert JP, Hintzen S, Ljung BM, Bergsland EK. Pancreatoblastoma in an adult: case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du E, Katz M, Weidner N, Yoder S, Moossa AR, Shabaik A. Ampullary pancreatoblastoma in an elderly patient: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1501–1505. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-1501-APIAEP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balasundaram C, Luthra M, Chavalitdhamrong D, Chow J, Khan H, Endres PJ. Pancreatoblastoma: a rare tumor still evolving in clinical presentation and histology. JOP. 2012;13:301–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh TH, Cooper JE, Newman CL, Walker TM, Kiely EM, Hoffmann EB. Pancreatoblastoma in a neonate with Wiedemann-Beckwith syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 1986;145:435–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00439255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drut R, Jones MC. Congenital pancreatoblastoma in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: an emerging association. Pediatr Pathol. 1988;8:331–339. doi: 10.3109/15513818809042976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger AK, Mughal SS, Allgäuer M, Springfeld C, Hackert T, Weber TF, Naumann P, Hutter B, Horak P, Jahn A, Schröck E, Haag GM, Apostolidis L, Jäger D, Stenzinger A, Fröhling S, Glimm H, Heining C. Metastatic adult pancreatoblastoma: Multimodal treatment and molecular characterization of a very rare disease. Pancreatology. 2020;20:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2020.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montemarano H, Lonergan GJ, Bulas DI, Selby DM. Pancreatoblastoma: imaging findings in 10 patients and review of the literature. Radiology. 2000;214:476–482. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.2.r00fe36476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boix E, Yuste A, Meana A, Alcaraz E, Payá A, Arnold C, Picó A, Lluis F. Corticotropin-releasing hormone-secreting pancreatoblastoma in an adult patient. Pancreas. 2010;39:938–939. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181d36444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y, Yang W, Hu J, Zhu Z, Qin H, Han W, Wang H. Diagnosis and treatment of pancreatoblastoma in children: a retrospective study in a single pediatric center. Pediatr Surg Int. 2019;35:1231–1238. doi: 10.1007/s00383-019-04524-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Défachelles AS, Martin De Lassalle E, Boutard P, Nelken B, Schneider P, Patte C. Pancreatoblastoma in childhood: clinical course and therapeutic management of seven patients. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37:47–52. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheithauer W, Chott A, Knoflach P. Alpha-fetoprotein-positive adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Int J Pancreatol. 1989;4:99–103. doi: 10.1007/BF02924151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinagawa T, Tadokoro M, Maeyama S, Maeda C, Yamaguchi S, Morohoshi T, Ishikawa E. Alpha fetoprotein-producing acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas showing multiple lines of differentiation. Virchows Arch. 1995;426:419–423. doi: 10.1007/BF00191352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolb-van Harten P, Rosien U, Klöppel G, Layer P. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma with excessive alpha-fetoprotein expression. Pancreatology. 2007;7:370–372. doi: 10.1159/000107397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanaoka T, Sato S, Tobita H, Miyake T, Ishihara S, Akagi S, Amano Y, Kinoshita Y. Clinical significance of the highly sensitive fucosylated fraction of α-fetoprotein in patients with chronic liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:739–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egashira Y, Suganuma M, Kataoka Y, Higa Y, Ide N, Morishita K, Kamada Y, Gu J, Fukagawa K, Miyoshi E. Establishment and characterization of a fucosylated α-fetoprotein-specific monoclonal antibody: a potential application for clinical research. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12359. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48821-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammer ST, Owens SR. Pancreatoblastoma: a rare, adult pancreatic tumor with many faces. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:1224–1226. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0272-CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palosaari D, Clayton F, Seaman J. Pancreatoblastoma in an adult. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:650–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zouros E, Manatakis DK, Delis SG, Agalianos C, Triantopoulou C, Dervenis C. Adult pancreatoblastoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:2293–2298. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elghawy O, Wang JS, Whitehair RM, Grosh W, Kindwall-Keller TL. Successful treatment of metastatic pancreatoblastoma in an adult with autologous hematopoietic cell transplant. Pancreatology. 2021;21:188–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2020.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosebrook JL, Glickman JN, Mortele KJ. Pancreatoblastoma in an adult woman: sonography, CT, and dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MRI features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:S78–S81. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.3_supplement.01840s78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JY, Kim IO, Kim WS, Kim CW, Yeon KM. CT and US findings of pancreatoblastoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20:370–374. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199605000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bläker H, Hofmann WJ, Rieker RJ, Penzel R, Graf M, Otto HF. Beta-catenin accumulation and mutation of the CTNNB1 gene in hepatoblastoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1999;25:399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiao Y, Yonescu R, Offerhaus GJ, Klimstra DS, Maitra A, Eshleman JR, Herman JG, Poh W, Pelosof L, Wolfgang CL, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Hruban RH, Papadopoulos N, Wood LD. Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic neoplasms with acinar differentiation. J Pathol. 2014;232:428–435. doi: 10.1002/path.4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klimstra DS, Heffess CS, Oertel JE, Rosai J. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:815–837. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.La Rosa S, Adsay V, Albarello L, Asioli S, Casnedi S, Franzi F, Marando A, Notohara K, Sessa F, Vanoli A, Zhang L, Capella C. Clinicopathologic study of 62 acinar cell carcinomas of the pancreas: insights into the morphology and immunophenotype and search for prognostic markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1782–1795. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318263209d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glick RD, Pashankar FD, Pappo A, Laquaglia MP. Management of pancreatoblastoma in children and young adults. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34 Suppl 2:S47–S50. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31824e3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlton-Ouw KM, Kaiser CL, Tong GX, Allendorf JD, Chabot JA. Revisiting metastatic adult pancreatoblastoma. A case and review of the literature. JOP. 2008;9:733–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levey JM, Banner BF. Adult pancreatoblastoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1841–1844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dunn JL, Longnecker DS. Pancreatoblastoma in an older adult. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:547–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu LC, Sidhu GS, Cassai ND, Yang GC. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of pancreatoblastoma in a young woman: report of a case and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;33:258–262. doi: 10.1002/dc.20355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoorens A, Gebhard F, Kraft K, Lemoine NR, Klöppel G. Pancreatoblastoma in an adult: its separation from acinar cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 1994;424:485–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00191433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robin E, Terris B, Valverde A, Molas G, Belghiti J, Bernades P, Ruszniewski P. [Pancreatoblastoma in adults] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1997;21:880–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gruppioni F, Casadei R, Fusco F, Calculli L, Marrano D, Gavelli G. Adult pancreatoblastoma. A case report. Radiol Med. 2002;103:119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mumme T, Büttner R, Peiper C, Schumpelick V. [Pancreatoblastoma: a rare malignant neoplasm in early adulthood] Chirurg. 2001;72:806–811. doi: 10.1007/s001040170108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayasaki N, Miyake N, Takahashi H, Nakamura E, Yamagishi S, Kuno Y, Mori N, Shinoda M, Kimura M, Suzuki T, Tashiro K. [A case of pancreatoblastoma in an adult] Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1999;96:558–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheng L, Weixia Z, Longhai Y, Jinming Y. Clinical and biologic analysis of pancreatoblastoma. Pancreas. 2005;30:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Savastano S, d'Amore ES, Zuccarotto D, Banzato O, Beghetto M, Famengo B. Pancreatoblastoma in an adult patient. A case report. JOP. 2009;10:192–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang D, Tang N, Liu Y, Wang EH. Pancreatoblastoma in an adult. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2015;58:93–95. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.151199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohike N, Yamochi T, Shiokawa A, Yoshida T, Yamazaki T, Date Y, Morohoshi T. A peculiar variant of pancreatoblastoma in an adult. Pancreas. 2008;36:320–322. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31815842c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen M, Zhang H, Hu Y, Liu K, Deng Y, Yu Y, Wu Y, Qi A, Li Y, Wen G. Adult pancreatoblastoma: A case report and clinicopathological review of the literature. Clin Imaging. 2018;50:324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamaguchi S, Fujii T, Izumi Y, Fukumura Y, Han M, Yamaguchi H, Akita T, Yamashita C, Kato S, Sekiya T. Identification and characterization of a novel adenomatous polyposis coli mutation in adult pancreatoblastoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9:10818–10827. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nunes G, Coelho H, Patita M, Barosa R, Pinto Marques P, Roque Ramos L, Brito MJ, Tomaz A, Fonseca J. Pancreatoblastoma: an unusual diagnosis in an adult patient. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018;11:161–166. doi: 10.1007/s12328-017-0812-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vilaverde F, Reis A, Rodrigues P, Carvalho A, Scigliano H. Adult pancreatoblastoma - Case report and review of literature. J Radiol Case Rep. 2016;10:28–38. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v10i8.2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuxhaus L, Swayne LC, Chevinsky A, Samli B. Adult metastatic pancreaticoblastoma detected with Tc-99m MDP bone scan. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:577–578. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000170228.87136.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Comper F, Antonello D, Beghelli S, Gobbo S, Montagna L, Pederzoli P, Chilosi M, Scarpa A. Expression pattern of claudins 5 and 7 distinguishes solid-pseudopapillary from pancreatoblastoma, acinar cell and endocrine tumors of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:768–774. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181957bc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gringeri E, Polacco M, D'Amico FE, Bassi D, Boetto R, Tuci F, Bonsignore P, Noaro G, D'Amico F, Vitale A, Feltracco P, Barbieri S, Neri D, Zanus G, Cillo U. Liver autotransplantation for the treatment of unresectable hepatic metastasis: an uncommon indication-a case report. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:1930–1933. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Redelman M, Cramer HM, Wu HH. Pancreatic fine-needle aspiration cytology in patients < 35-years of age: a retrospective review of 174 cases spanning a 17-year period. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:297–301. doi: 10.1002/dc.23070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu ET, Liu C, Wang HL, Sun TT, Wang SX. Adult Pancreatoblastoma With Liver Metastasis Diagnosed by 18F-FDG PET/CT and 2 Years' Postoperative Follow-up. Clin Nucl Med. 2020;45:e24–e28. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Terino M, Plotkin E, Karagozian R. Pancreatoblastoma: an Atypical Presentation and a Literature Review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2018;49:361–364. doi: 10.1007/s12029-017-9925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morrissey G, Cohen P, Julve M. Rare case of adult pancreatoblastoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-233884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Snyder MH, Ampie L, Mandell JW, Helm GA, Syed HR. A Rare Case of Pancreatoblastoma with Intracranial Seeding. World Neurosurg. 2020;142:334–338. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.06.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]