Abstract

Septal reduction techniques can reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy who was a poor candidate for surgical myectomy and alcohol septal ablation, endocardial radiofrequency ablation of septal hypertrophy provided durable reduction in left ventricular outflow tract gradients and symptomatic improvement. (Level of Difficulty: Intermediate.)

Key Words: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, radiofrequency ablation

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ASA, alcohol septal ablation; ERASH, endocardial radiofrequency ablation of septal hypertrophy; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; ICE, intracardiac echocardiogram; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; RF, radiofrequency; SAM, systolic anterior motion; SM, surgical myectomy; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram

Graphical abstract

Septal reduction techniques can reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. In a patient with hypertrophic…

A 69-year-old man with a history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) presented with progressive dyspnea on exertion and lightheadedness. The patient’s symptoms were refractory to optimal medical therapy with diuretics and beta-blockers.

Learning Objectives

-

•

Case study: A patient with HCM presented with symptoms of heart failure that were refractory to medical therapy.

-

•

To learn that in patients with HCM who are poor surgical candidates, and do not have appropriate septal perforators for ASA, ERASH is an alternative treatment for LVOT obstruction.

-

•

To understand that during ERASH procedures, integrated electroanatomic mapping and intracardiac ultrasound allow operators to annotate the location of conduction system structures onto the intracardiac echocardiogram.

-

•

To establish that when using ICE to guide ablation of septal hypertrophy, conduction system structures can be visualized in a superimposed fashion and precisely avoided.

Past Medical History

The patient was diagnosed with HCM 4 years earlier when hospitalized for dyspnea. His past medical history also included 2 liver transplants for alcoholic cirrhosis, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease. He had no known family history of cardiomyopathy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis included progressive heart failure symptoms from left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, worsening left ventricular function, and symptoms attributable to atrial fibrillation.

Investigations

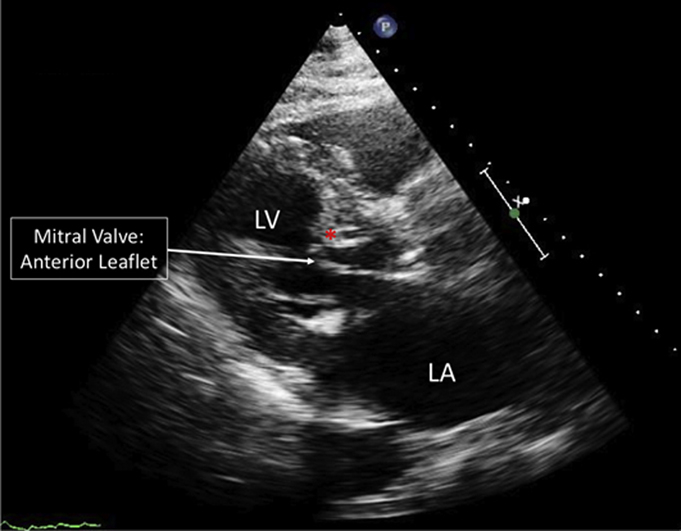

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed an ejection fraction of 66%, with LVOT gradients by spectral Doppler of 52 mm Hg at rest and 144 mm Hg with Valsalva. Moderate systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the anterior mitral valve leaflet was observed (Figure 1, Video 1). A transesophageal echocardiogram also demonstrated severe basal septal hypertrophy with SAM of the anterior mitral leaflet, and mild mitral regurgitation caused by HCM (Video 2). Despite cardioversion to normal sinus rhythm and up-titration of medications, the patient continued to have significant dyspnea, suggesting his symptoms were attributable to LVOT obstruction. Because he was deemed a poor surgical candidate due to multiple medical comorbidities, he was referred for alcohol septal ablation (ASA).

Figure 1.

Pre-Operative Transthoracic Echocardiogram

Parasternal long-axis view of a pre-operative transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrating severe basal septal hypertrophy and systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve. ∗Hypertrophied basal septum. LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle.

Online Video 1.

Apical 4-chamber view of a transthoracic echocardiogram obtained prior to the procedure while patient is in a ventricular-paced rhythm which demonstrates severe basal septal hypertrophy and systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve causing left ventricular outflow tract obstruction.

Online Video 2.

Preoperative transesophageal echocardiogram with (right) and without (left) Doppler demonstrating severe left ventricular outflow tract obstruction as a result of systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve and the hypertrophied basal septum.

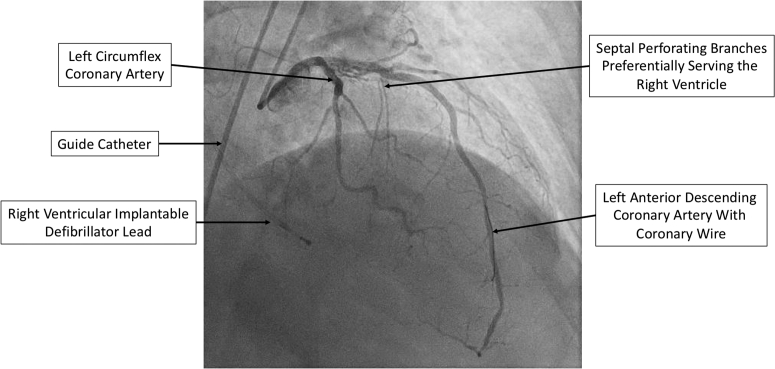

Coronary angiography revealed that the first 2 septal perforating branches of the left anterior descending had significant right ventricular involvement, and did not supply the hypertrophied basal septum (Figure 2). For this reason, ASA was aborted. The patient was then referred for endocardial radiofrequency ablation of septal hypertrophy (ERASH) guided by intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) and electroanatomic mapping.

Figure 2.

Right Anterior Oblique Coronary Angiogram

Right anterior oblique coronary angiogram demonstrating significant right ventricular involvement of the first 2 septal perforating branches of the left anterior descending coronary artery.

Management

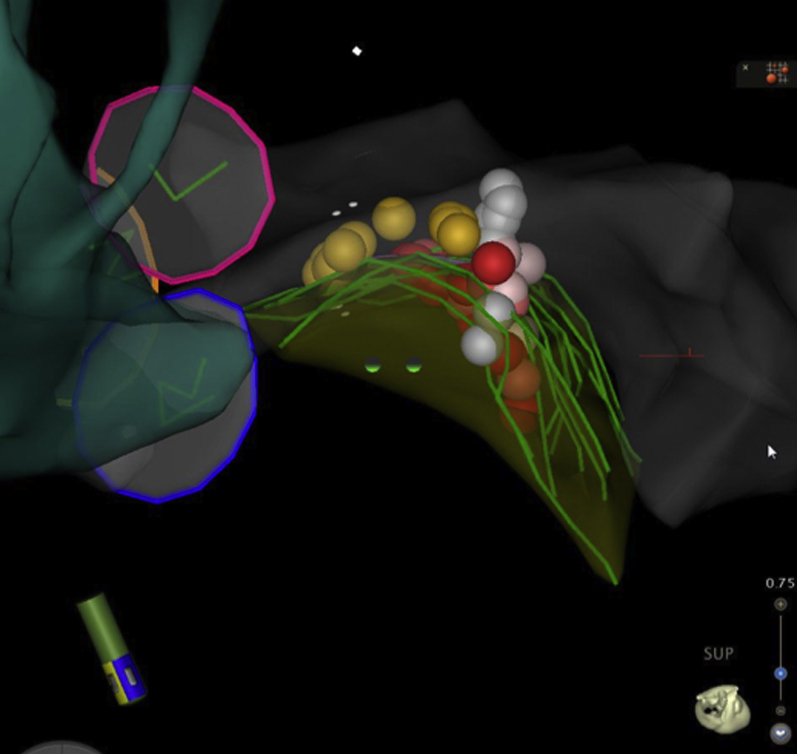

After administration of general anesthesia, invasive hemodynamics measured using an angled pigtail catheter in the apical left ventricle and a 30-cm long 8-F sheath (Brite Tip, Cordis, Hialeah, Florida) in the descending aorta revealed a post-premature ventricular contraction gradient of 100 mm Hg (Figure 3). Intravenous heparin was administered with an activated clotting time goal of >300 s while catheters were in the left ventricle. An electroanatomic map was created with an 8-F, phased-array ICE catheter (SoundStar, Biosense Webster, Irvine, California) placed in the right atrium and an irrigated-electrode radiofrequency ablation catheter (Thermocool SF, Biosense Webster) inserted into left ventricle via retrograde approach (Video 3). Using image integration between the ICE images and the 3-dimensional mapping system (CARTO Sound, Biosense Webster), the area of maximal contact between the basal septum and mitral valve was identified (Figure 4, Video 4). Recordings from the His bundle and left bundle branch were also tagged to prevent injury during ablation (Figure 4, Video 4).

Figure 3.

Invasive Hemodynamic Measurements

A left ventricular outflow tract gradient of 100 mm Hg is observed before ablation. PVC = premature ventricular contraction.

Online Video 3.

Intracardiac echocardiogram demonstrating the irrigated-electrode radiofrequency ablation catheter (Thermocool SF, Biosense Webster) being advanced into the left ventricle via retrograde approach and approaching the hypertrophied basal septum.

Figure 4.

Three-Dimensional Electroanatomic Map During Septal Ablation

The aortic cusps are shown as 3 circular rings (pink = left; blue = right; orange = noncoronary), and part of the left ventricular shell in grey. The green curved lines denote the hypertrophied basal septum as outlined on intracardiac echocardiogram images, and the pink plane denotes the area of maximal contact between the anterior mitral leaflet and the septum. The yellow and blue dots denote areas with fascicular/left bundle potentials. The white, pink, and red dots indicate ablation lesions delivered, and are color coded according to impedance drop (<5 ohms, white; 5 to 10 ohms, pink; >10 ohms, red).

Online Video 4.

Integrated electroanatomic mapping and intracardiac echocardiography (CARTO-Sound, Biosense Webster, Irvine, CA) images during ablation. The aortic cusps are seen as 3 circular rings (pink: left; blue: right; orange: non-coronary), and part of the left ventricular shell is in grey. The pink plane indicates the basal septum in greatest contact with the mitral valve apparatus during systole. The yellow and blue dots denote areas with fascicular/left bundle potentials. The white, pink and red dots indicate ablation lesions delivered, and are color coded according to impedance drop (<5 ohms: white; 5-10 ohms: pink; >5 ohms: red). In the bottom right ICE image, the tip of the ablation catheter is seen outlined in green.

The portion of the septum in greatest contact with the anterior mitral valve was targeted for ablation via retrograde approach with 9 radiofrequency (RF) lesions. RF ablation was delivered primarily using 50 W for 60 s to a target of 10 ohm impedance drop, while avoiding His and bundle branch potentials (Figure 4, Video 4). Because of difficulty achieving optimal electrode-tissue contact during ablation via the retrograde approach, an 8.5-F deflectable sheath (Agilis, Abbott, Chicago, Illinois) and RF-powered transseptal needle (Baylis, Toronto, Canada) were used for transseptal catheterization and 16 additional RF lesions were delivered via transseptal approach (Figure 5). The endpoint for each ablation was adequate modification of the area of maximal contact as demonstrated by electroanatomic mapping and ICE. The mean contact force per ablation was 14 ± 8.5 g and total ablation time was 23.4 min with 55.2 min of fluoroscopy.

Figure 5.

Final Lesions Set

Superior view looking “down” on the hypertrophied basal septum. The shell of the aorta is seen in blue-green, the aortic cusps as 3 circular rings (pink = left; blue = right; orange = noncoronary), and part of the left ventricular shell in grey. The green curved lines denote the hypertrophied basal septum as outlined on intracardiac echocardiography. The yellow dots denote areas with fascicular/left bundle potentials. The white, pink, and red dots indicate ablation lesions delivered, and are color coded according to impedance drop (<5 ohms, white; 5 to 10 ohms, pink; >10 ohms, red).

Post-ablation, the invasive post–premature ventricular contraction gradient was 0 mm Hg (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Invasive Hemodynamic Measurements

A left ventricular outflow tract gradient of 0 mm Hg is observed following ablation. PVC = premature ventricular contraction.

Discussion

HCM is a genetic condition that can cause variable symptoms of congestive heart failure because of LVOT obstruction (1). Approximately 70% of patients with HCM develop obstruction to antegrade flow caused by SAM of the mitral valve making contact with the hypertrophied septum (2). If LVOT gradients are persistently >30 mm Hg, patients are at increased risk for progressive heart failure and death (1,3).

Surgical septal myectomy (SM) is the gold standard for operative treatment of LVOT obstruction. For inoperable patients, such as the elderly or those with extensive medical comorbidities, percutaneous treatment options are available (3).

Through the direct injection of ethanol into a septal perforating artery, ASA leads to reduction in septal thickness, causing a reduction in LVOT gradient, and has been used as an alternative to SM with similar rates of symptom improvement and survival benefit (1,2,4). Importantly, ASA may not always be anatomically feasible, because the septal perforating arteries may not supply the hypertrophied septum (3).

For patients with HCM who are not candidates for SM or ASA, ERASH has emerged as a viable treatment option that has been shown noninvasively to reduce intracavitary gradients and improve symptoms (5, 6, 7, 8). It is now possible to precisely locate the areas of greatest contact between the mitral valve and hypertrophied septum on ICE and tag them to electroanatomic maps to guide catheter ablation. Furthermore, this integrated mapping allows for the native conduction system to be tagged and avoided during ablation, representing a potential benefit over ASA (9,10).

Although ERASH has previously been reported, this is the first case to document efficacy via invasive hemodynamics before and after RF ablation guided by integration between electroanatomic mapping and ICE. The potential mechanisms for gradient reduction include a focal reduction in the myocardial tissue in contact with the mitral valve, reduced myocardial motion of the hypertrophied septum, or development of a new left bundle branch block.

Follow-Up

Immediately following the procedure, the patient had improvement in dyspnea and an increase in exercise tolerance. On TTE 4 months post-procedure, his peak LVOT gradient was 4 mm Hg with mild chordal SAM (Video 5). The patient’s basal septal wall thickness decreased from 2.07 cm on his pre-procedure TTE to 1.80 cm on TTE 4 months post-procedure (Figure 7). Serial electrocardiograms have revealed no conduction abnormalities.

Online Video 5.

Apical 4-chamber view of a transthoracic echocardiogram obtained 4 months post-procedure while the patient is in a ventricular-paced rhythm demonstrating improvement in the interaction between the anterior mitral valve leaflet and hypertrophied basal septum, with a left ventricular outflow tract gradient of 4mmHg.

Figure 7.

Parasternal Long-Axis Views

Parasternal long-axis views of transthoracic echocardiograms obtained pre-procedure (A) and 4 months post-procedure (B) demonstrating a reduction in basal septal wall thickness from 2.07 cm to 1.8 cm.

Conclusions

ERASH is an alternative for treatment of LVOT obstruction from HCM when SM and ASA are not feasible. By allowing for targeted ablation of hypertrophied septum while avoiding the conduction system, ERASH may be associated with fewer conduction disturbances, and a smaller, more targeted area of ablated septum. Larger studies are needed to further validate this approach and determine long-term efficacy.

Footnotes

Northwestern University has received fellowship support from Medtronic, Inc. Dr. Knight has received honoraria for consulting and speaking from Medtronic Inc. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Case Reportsauthor instructions page.

Appendix

For supplemental videos, please see the online version of this paper.

References

- 1.Maron B.J., Maron M.S. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2013;381:242–255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron B.J. Clinical course and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:655–668. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1710575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gersh B.J., Maron B.J., Bonow R.O. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e212–e260. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorajja P., Ommen S.R., Holmes D.R., Jr. Survival after alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2012;126:2374–2380. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.076257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrenz T., Kuhn H. Endocardial radiofrequency ablation of septal hypertrophy. A new catheter-based modality of gradient reduction in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Z Kardiol. 2004;93:493–499. doi: 10.1007/s00392-004-0097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riedlbauchova L., Janousek J., Veselka J. Ablation of hypertrophic septum using radiofrequency energy: an alternative for gradient reduction in patient with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy? J Invasive Cardiol. 2013;25:E128–E132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelke A.B., Menon R., Kapadiya A. A novel approach in the use of radiofrequency catheter ablation of septal hypertrophy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Indian Heart J. 2016;68:618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crossen K., Jones M., Erikson C. Radiofrequency septal reduction in symptomatic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:1885–1890. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper R.M., Shahzad A., Hasleton J. Radiofrequency ablation of the interventricular septum to treat outflow tract gradients in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a novel use of CARTOSound(R) technology to guide ablation. Europace. 2016;18:113–120. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrenz T., Borchert B., Leuner C. Endocardial radiofrequency ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: acute results and 6 months' follow-up in 19 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:572–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]