Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 2

Unpaired t-test has been used to compare the data. Percentages have been added to table 2. Data analysis was done using Microsoft Excel 2016 with data analysis add-in and epidemiology & biostatistics calculator available on www.openepi.com.

Abstract

Background: Research on the psychosocial toll of the COVID-19 pandemic is being conducted in various countries. This study aimed to examine stress levels and causal stressors for perceived stress and generalized anxiety in the Indian population related to the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: A total of 300 adults were invited to participate in the online study via snowball and virtual snowball sampling. They were requested to complete electronic survey forms for assessing perceived stress and anxiety, and questions related to psychosocial stressors. Frequency and percentage were used for categorical variables. Unpaired t-test was applied to compare responses based on gender, level of education, employment, and place of residence. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result: In total, 257 out of the 300 invited, responded and completed the survey. Men accounted for 58% (n=149) of the respondents. Overall, 84% (n=217) of participants had moderate to severe levels of perceived stress and 88% (n=228) had moderate to severe levels of anxiety. Women, as well as those not employed, reported significantly higher perceived stress and anxiety, urban residents reported higher perceived stress, while level of education had no difference in terms of perceived stress as well as anxiety. Fear of contracting COVID-19 was the highest stressor followed by difficulties in executing a routine exercise schedule and worry about the future.

Conclusion: The psychosocial impact of the nationwide lockdown on the Indian population has been high. Vulnerable groups for increased stress and anxiety include women, younger ages, and the unemployed. The stressors recognized include fear of contracting COVID-19, inability to execute a routine exercise schedule and worry about the future.

Keywords: COVID-19, lockdown, perceived stress, anxiety, stressors, India, PSS-10, GAD-7

Introduction

Since the beginning of 2020, humanity has been confronted with a pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 1. The government of India declared a 21-day nationwide ‘lockdown’ from 25 th March 2020, which was subsequently extended in phases till 31 st May 2020, to break the cycle of spread of infection. The lockdown was in tune with the initiatives taken by many countries across the globe against this pandemic 2, 3.

‘Lockdown’ is an emergency protocol and is a means of preventing the public from moving from one place to the other. This led to shutting down of all activities except those considered ‘essential services’, which included healthcare, police, sanitation, grocery shops, petrol stations and fire stations. All educational institutions, offices, factories, shopping malls, religious places, and public transport, including buses, railways and aeroplanes, were completely shut down, and sports, religious ceremonies, family functions and all outdoor activities were strictly prohibited.

While isolation and lockdown are recognized as effective strategies of social distancing to stop the spread of COVID-19, the reduced access to family, friends, and other social support systems causes loneliness, increasing mental health issues like anxiety and depression 4– 6 .

Researchers, in the past and during this present crisis, have tried to address the psychological stress in healthcare providers 7– 9 and the general population 2, 3, 10. The present study, conducted during the fourth phase of nationwide lockdown, from 18 th to 31 st May 2020, attempts to examine levels of perceived stress and generalized anxiety disorders and causal stressors among the Indian population related to the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent lockdown.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted an online survey wherein 300 participants were invited via snowball and virtual snowball sampling; the sample size was decided on the basis of logistics and time availability for the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the ABV Government Medical College, Vidisha, MP, India (reference no. 21(b)/IEC/ABV GMC/Vidisha/2020).

A link to the electronic survey forms ( Extended data 11) was posted on Facebook, and was sent via WhatsApp by the authors to multiple contacts, including colleagues and acquaintances that were from a wide section of society. Consent to participate was implied if the participant completed the questionnaire. The items for the questionnaire were derived from previous study on the topic 12.

Inclusion criteria of participants were: a) aged >18 years; b) have an internet connection and Facebook or WhatsApp installed on their mobile phone. Those unwilling to participate or did not provide consent and those <18 years of age were excluded because the psychometric measures utilized in the study were designed for adults only.

Data collection and survey

Data was collected from 18 th to 25 th May 2020.

The survey questionnaire, based on the perceived stress scale (PSS-10) 12 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) 7 instruments, explored the psychosocial stressors among the respondents. For each potential stressor, the frequency of occurrence was classified as never, almost never, sometimes, often, and very often, and these were scored as 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. While PSS measures perception of stress over the last month GAD measures anxiety for the last 2 weeks; both these instruments have been used in previous studies on this subject 7, 10, 12.

Data analysis

The data collected were tabulated and analysed using Microsoft Excel 2016 with data analysis add-in and epidemiology & biostatistics calculator available on www.openepi.com. Frequency and percentage were used for categorical variables. Unpaired t-test was applied to compare responses based on gender, age, level of education, and place of residence. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We used the STROBE cross sectional checklist when writing our report 13.

Results

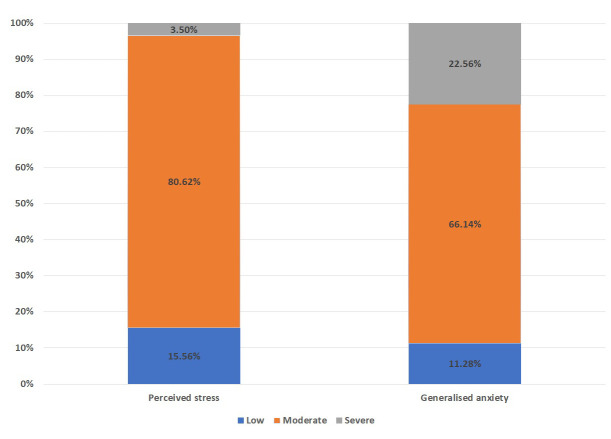

A total of 257, out of the 300 participants who were sent the survey, responded and completed the survey. They belonged to central, north and western India. The mean age of the participants was 25 years. Men constituted 58% (n=149) of the respondents. Overall, 84% (n=217) of participants had moderate to severe levels of perceived stress and 88% (n=228) had moderate to severe levels of anxiety ( Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of perceived stress & generalized anxiety stress in Indian population grouped as low, moderate and severe as per scoring guides of PSS-10 and GAD-7.

Table 1 shows the PSS-10 and GAD-7 scores of the study participants as stratified by gender, age, level of education, and place of residence. Women as well as those not employed reported significantly higher perceived stress and anxiety, urban residents reported higher perceived stress while the level of education had no difference in terms of perceived stress as well as anxiety. The psychosocial impact of the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic is shown in Table 2. Fear of contracting COVID-19 was the highest stressor followed by difficulties in executing routine exercise schedule and worry about the future.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants showing perceived stress score and generalized anxiety disorder scale score.

| Characteristics | Number

(%) |

Perceived Stress Scale

(PSS-10) |

Generalised Anxiety

Disorder (GAD-7) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score

(Mean±SD) |

p –value * | Score

(Mean±SD) |

p –value * | |||

| Gender | Male | 149 (58) | 17.28±5.25 | 0.0028 | 11.92±3.974 | 0.0176 |

| Female | 108 (42) | 19.11±4.44 | 12.93±2.80 | |||

| Employed | No | 176 (68.48) | 18.83±4.32 | 0.0009 | 13.18±2.93 | 0.000000722 |

| Yes | 81 (31.51) | 16.34±5.91 | 10.53±4.10 | |||

| Education | University | 220 (85.6) | 18.19±5.03 | 0.246 | 12.46±3.59 | 0.190 |

| School | 37 (14.39) | 17.18±4.818 | 11.67±3.31 | |||

| Place of

residence |

Urban | 178 (69.26) | 18.76±4.69 | 0.001 | 12.26±3.50 | 0.57 |

| Rural | 79 (30.73) | 16.44±5.33 | 12.54±3.70 | |||

(SD: standard deviation; * by using unpaired t-test)

Table 2. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 (rated on a Likert scale).

| Statements | Frequency of occurrence (N) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Never / almost

never |

Sometimes | Often / very

often |

|

| How often do you face financial strain during the lockdown period? | 110 (42.8%) | 84 (32.7%) | 63 (24.5%) |

| How often do you worry about the future? | 81 (31.5%) | 94 (36.6%) | 82 (31.9%) |

| How often do you fear contracting COVID-19? | 35 (13.6%) | 57 (22.2%) | 165 (64.2%) |

| How often do you feel stress due to inability to socialize? | 123 (47.9%) | 81 (31.5%) | 53 (20.6%) |

| How often do you face difficulties in executing your routine exercise

schedule during the lockdown period? |

100 (38.9%) | 72 (28%) | 85 (33.1%) |

| How often do you face sleeping difficulties during the lockdown

period? |

165 (64.2%) | 48 (18.7%) | 44 (17.1%) |

Discussion

The levels of stress and anxiety reported in the present study are similar to those reported by researchers from other countries 2, 3, 5, 14. The present study is in agreement with previous studies from other parts of the world where women and those with lower incomes are prone to higher levels of stress and anxiety 2, 3, 5, 15, 16; this was in contrast to a study from Pakistan where men reported a higher degree of stress during the current crisis 17. This could be attributed to cultural factors, which need further evaluation for clearer understanding.

In the present study, older respondents reported lower levels of stress. This could suggest the struggle and hardships of daily life which the younger generation is under 18; also, the younger generation tends to obtain a large amount of information from social media, which can easily trigger stress 3, 10. We found significant difference in the levels of perceived stress reported between urban and rural residents, while no such difference was noted in generalised anxiety scores.

In the present study, we found no difference in the levels of stress when considering the level of education of the respondents. Vallejo et al. 19 found those with a lower level of education to be reporting higher stress. Other studies found that those who were highly educated had a higher risk of depression; it is presumed that highly educated and professional people are forced to stay at home and delve into other aspects of family life leading to higher levels of perceived stress 5, 10.

When considering the psychosocial impact of COVID-19, fear of contracting COVID-19 was the highest stressor, which was consistent with other studies 17, 20. This was followed by difficulties in executing your routine exercise schedule and worry about the future ( Table 2).

Limitations

This being a cross-sectional study, the selection of participants was non-random, and it is impossible to make unbiased estimates from snowball samples so the results of this study need to be interpreted with due caution. However, this was the best available method of data collection in the current circumstances. The study was also limited by the lack of other socio-demographic and cross-cultural comparison groups.

Conclusions

The psychosocial impact of the nationwide lockdown on the Indian population has been high. The vulnerable groups for stress and anxiety include women, those of a younger age, and the unemployed. The stressors recognized include fear of contracting COVID-19, inability to execute routine exercise schedule and worry about the future.

Data availability

Underlying data

Figshare: Raw data PSS_GAD Psychosocial impact of lockdown.csv, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12860060.v2 11.

Extended data

Figshare: Raw data PSS_GAD Psychosocial impact of lockdown.csv, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12860060.v2 11.

This project contains the following extended data:

-

-

Online questionnaire.

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 3; peer review: 3 approved]

References

- 1.Ebeid FSE: COVID-19 effect on clinical research: Single-site risk management experience. Perspect Clin Res. 2020;11(3):106–110. 10.4103/picr.PICR_119_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horesh D, Lev-Ari RK, Hasson-Ohayon I: Risk factors for psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: Loneliness, age, gender, and health status play an important role. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25(4):925–933. 10.1111/bjhp.12455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, et al. : A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2):e100213. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau H, Khosrawipour V, Kocbach P, et al. : The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Travel Med. 2020;27(3):taaa037. 10.1093/jtm/taaa037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Di Y, Ye J, et al. : Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychol Health Med. 2020;26(1):13–22. 10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou X, Snoswell CL, Harding LE, et al. : The Role of Telehealth in Reducing the Mental Health Burden from COVID-19. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(4):377–379. 10.1089/tmj.2020.0068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Rabiaah A, Temsah MH, Al-Eyadhy AA, et al. : Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Corona Virus (MERS-CoV) associated stress among medical students at a university teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(5):687–691. 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nanjundaswamy MH, Pathak H, Chaturvedi SK: Perceived stress and anxiety during COVID-19 among psychiatry trainees. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102282. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Podder I, Agarwal K, Datta S: Comparative analysis of perceived stress in dermatologists and other physicians during national lock-down and COVID-19 pandemic with exploration of possible risk factors: A web-based cross-sectional study from Eastern India. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4):e13788. 10.1111/dth.13788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedrozo-Pupo JC, Pedrozo-Cortés MJ, Campo-Arias A: Perceived stress associated with COVID-19 epidemic in Colombia: an online survey. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(5):e00090520. 10.1590/0102-311x00090520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakode N, Wakode S, Santoshi J: Raw data PSS_GAD Psychosocial impact of lockdown.csv. figshare. Dataset.2020. 10.6084/m9.figshare.12860060.v2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah M, Hasan S, Malik S, et al. : Perceived stress, sources and severity of stress among medical undergraduates in a Pakistani medical school. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:2. 10.1186/1472-6920-10-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. : The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, et al. : Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):228–229. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iqbal S, Gupta S, Venkatarao E: Stress, anxiety and depression among medical undergraduate students and their socio-demographic correlates. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141(3):354–357. 10.4103/0971-5916.156571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein EM, Brähler E, Dreier M, et al. : The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale - psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:159. 10.1186/s12888-016-0875-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balkhi F, Nasir A, Zehra A, et al. : Psychological and Behavioral Response to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e7923. 10.7759/cureus.7923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aneshensel CS: Toward Explaining Mental Health Disparities. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(4):377–394. 10.1177/002214650905000401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vallejo MA, Vallejo-Slocker L, Fernández-Abascal EG, et al. : Determining Factors for Stress Perception Assessed with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) in Spanish and Other European Samples. Front Psychol. 2018;9:37. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, et al. : Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5):779–788. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]