Abstract

Background

Ethnic minority groups in Western countries face an increased risk of psychotic disorders. Causes of this long-standing public health inequality remain poorly understood. We investigated whether social disadvantage, linguistic distance and discrimination contributed to these patterns.

Methods

We used case–control data from the EUropean network of national schizophrenia networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) study, carried out in 16 centres in six countries. We recruited 1130 cases and 1497 population-based controls. Our main outcome measure was first-episode ICD-10 psychotic disorder (F20–F33), and exposures were ethnicity (white majority, black, mixed, Asian, North-African, white minority and other), generational status, social disadvantage, linguistic distance and discrimination. Age, sex, paternal age, cannabis use, childhood trauma and parental history of psychosis were included as a priori confounders. Exposures and confounders were added sequentially to multivariable logistic models, following multiple imputation for missing data.

Results

Participants from any ethnic minority background had crude excess odds of psychosis [odds ratio (OR) 2.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.69–2.43], which remained after adjustment for confounders (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.31–1.98). This was progressively attenuated following further adjustment for social disadvantage (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.22–1.89) and linguistic distance (OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.95–1.57), a pattern mirrored in several specific ethnic groups. Linguistic distance and social disadvantage had stronger effects for first- and later-generation groups, respectively.

Conclusion

Social disadvantage and linguistic distance, two potential markers of sociocultural exclusion, were associated with increased odds of psychotic disorder, and adjusting for these led to equivocal risk between several ethnic minority groups and the white majority.

Key words: Discrimination, epidemiology, ethnicity, psychotic disorders, social disadvantage

Introduction

People diagnosed with a psychotic disorder have a decreased life expectancy of 15 years compared with the general population (Hayes, Marston, Walters, King, & Osborn, 2017; Hjorthøj, Stürup, McGrath, & Nordentoft, 2017). The risk of developing such disorders inequitably affects migrants and their descendants in high-income countries (Selten, van der Ven, & Termorshuizen, 2020), making this a pressing public health concern, particularly in the context of accelerating global migration (Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2017). Despite almost a century of research (Ødegaard, 1932), the causes of increased rates of psychotic disorder in ethnic minority groups remain poorly understood. They are not an artefact of demography: differences persist after adjusting for age, sex (Jongsma et al., 2018) and socioeconomic status (SES) (Kirkbride, Hameed, Ankireddypalli, et al., 2017). Whilst disparities in pathways to care (Anderson, Flora, Archie, Morgan, & McKenzie, 2014) and outcomes (Morgan et al., 2017) exist by ethnicity, there is little evidence that this explains differential rates between ethnic groups. Over-diagnosis in ethnic minority groups is not supported by evidence from clinical practice (Hickling, McKenzie, Mullen, & R, 1999; Lewis, Croft-Jeffreys, & David, 1990), nor by epidemiological studies using culturally-sensitive diagnostic instruments (Zandi et al., 2010) or partially-blinded, consensus-based research criteria to ascertain diagnoses (Fearon et al., 2006). Excess rates are also not ‘inherent’ to any ethnic group; for instance, incidence in people of black Caribbean heritage in the UK is up to five times higher than for the white British population (Kirkbride et al., 2006), a pattern not observed in estimates of incidence rates in Caribbean countries (Bhugra et al., 1996; Hickling, 1995). Whilst pre-migratory circumstances, including adversities experienced by refugees, may exacerbate risk (Brandt et al., 2019), post-migratory factors are also implicated, given the persistence of elevated risk in second-generation migrants (Selten et al., 2019). Given this persistence of excess risk in migrants and their descendants, we focus our investigation on the social context in high-income countries and use the term ethnic minorities throughout.

The social gradient in health, where those who are worse off socio-economically have worse health, might provide an explanation for this excess psychosis risk in some ethnic minority groups (Fisher & Baum, 2010; Marmot, 2006; Marmot et al., 2010). Social gradients are strongly patterned by ethnic minority status (Savage et al., 2013; Statistics Netherlands, 2018). Seen through this lens, health disparities arise via a process of (psychosocial) disempowerment, which is defined as experiencing a lack of control over one's life (Marmot, 2015). Individuals without sufficient social, economic, political or cultural capital required to achieve autonomy and control over their environment are exposed to more risk factors for poor health outcomes including psychotic disorders. Risk factors include lower education, SES and social isolation (Marmot, 2006; Marmot et al., 2010; Public Health England & UCL Institute of Health Equity, 2017).

Here, we propose that excess risks of psychotic disorder in several ethnic minority groups may arise through such a process of psychosocial disempowerment, following greater exposure to social disadvantage (Savage et al., 2013; Statistics Netherlands, 2018) and exclusion based on cultural and ethnic identity (Akerlof & Kranton, 2011; Nazroo & Karlsen, 2003; Smaje, 1996), including language barriers and overt experiences of discrimination. To test this hypothesis empirically, we examined whether individual-level social disadvantage (an indication of the ethnic patterning of the social gradient in health), linguistic distance and experiences of discrimination differed between ethnic groups, and tested whether this accounted for differences in the risk of psychotic disorders by ethnicity and generational status. We used data from the six-country EUropean network of national schizophrenia networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI; work package 2) case–control study, which included these exposure measures in an ethnically- and culturally-diverse sample.

Methods

Study design and participants

Participants were recruited in 17 centres in England, the Netherlands, Spain, France, Italy and Brazil, between 2010 and 2015 (Jongsma et al., 2018). All persons aged 18–64 years who made contact with mental health services for a probable first-episode of psychosis (FEP) were invited to participate via their mental healthcare provider. Cases were included if they subsequently met International Classification of Disease (ICD)-10 criteria for a psychotic disorder (F20–33), ascertained using the Operational Criteria Checklist (OPCRIT) algorithm [detailed fully elsewhere (Jongsma et al., 2018)]. We included non-affective psychotic disorders (ICD-10 codes F20–25) and affective psychotic disorders (ICD-10 codes F30–F33) as secondary outcomes.

In each centre, we recruited controls from the population-at-risk (individuals who never had an FEP). We used random sampling methods (e.g. via general practice lists in the UK) and set quotas to ensure that our control sample was representative of the age–sex–ethnicity structure of the population-at-risk. Controls with a history of psychotic disorder, or taking anti-psychotic medication, were excluded. Some centres purposively over-sampled hard-to-reach groups to increase representativeness (online Supplementary Methods).

We excluded participants with insufficient exposure data to estimate linguistic distance, and cases for whom an OPCRIT diagnosis could not be completed. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving participants were approved by the following respective local ethics committees: South London and Maudsley and Institute of Psychiatry Research Ethics Committee; National Research Ethics Service Committee East of England–East Cambridge; Medisch-Ethische Toetsingscommissie van het Academisch Centrum te Amsterdam; Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica Hospital Gregorio Marañón; Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica del Hospital Clinic de Barcelona; Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica del Hospital Clinic Universitari de Valencia; Comité Ética de la Investigación Clínica del Principado de Asturias; Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica de Galicia; Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica del Hospital Virgen de la Luz de Cuenca; Comité de Protéction des Personnes–CPP Île de France IX; Comitato Etico Policlinico S Orsola Malpighi; Comitato Etico Azienda Ospedaleria Universitaria di Verona; Comitato Etico Palermo 1, Azienda Ospedaliera Policlinico ‘Paolo Giaccone’; and Research Ethics Committee of the clinical Hospital of Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo, Brazil. All participants gave written informed consent (Di Forti et al., 2019; Jongsma et al., 2018).

Measures

Our main exposures were indicator variables which operationalised the constructs of ethnicity, social disadvantage, linguistic distance and self-perceived discrimination, obtained from an amended version of the Medical Research Council Socioeconomic Schedule (MRC SDS) (Di Forti et al., 2019; Mallett, 1997). Ethnic group was coded by self-ascription to seven categories: white majority (reference category, i.e. in English sites, white British), black, mixed, Asian, north African, white minority and other (see online Supplementary Methods). We chose the white majority as our reference category, as in each country, this referred to the majority population. We also examined results by generational status (first- or later-generation), based on place of birth and ethnicity. We defined a set of indicators of social disadvantage (including social functioning) to include educational attainment (no qualifications; school qualifications; tertiary; vocational; undergraduate; postgraduate), lifetime relationship status [ever/never in a long-term (1 < year) relationship], lifetime living arrangements (lived with people other than parents; yes/no) and parental SES. This was based on the main breadwinner's highest occupation, categorised from the European Socio-economic Classification (Harrison & Rose, 2006) to six categories: professional (higher and lower grade), intermediate (intermediate occupations, small employers, self-employed), lower (supervisory, technician, services, sales, clerical and technical), routine, never worked (including long-term unemployed) and not classified (including students).

Linguistic distance was operationalised using two measures: language distance and fluency in the majority language (Candelo, Croson, & Li, 2017; Koczan, 2016; West & Graham, 2004). We estimated language distance by scoring each participant's first language as a function of distance on a language tree from the majority language in their country of residence (i.e. England, France, Spain, etc). Scores were rated from 0 (participant first language same as majority language in the country of residence) to 3 (participant first language from a different language family to majority language; see online Supplementary Methods and Fig. S1). The face validity of this approach was confirmed by an expert in linguistics (JvdW). Fluency in the majority language was a single, self-rated item and was rated on a 10-point scale. Due to skew on both measures (online Supplementary Figs S2 and S3), we created a binary linguistic distance variable: no linguistic distance (language distance = 0, fluency = 10) or some linguistic distance (language distance ⩾1 and/or fluency ⩽9). We measured all-cause self-perceived discrimination continuously, using a 12-item version of the Major Experiences of Discrimination questionnaire (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997) (online Supplementary Methods).

We also adjusted for sex, parental history of psychosis, lifetime cannabis use (all binary), age, paternal age and childhood trauma (all continuous) as a priori confounders. Age, sex and paternal age were derived from the MRC SDS. Parental history of psychosis was recorded using the Family Interview for Genetic Studies questionnaire (NIHM Center for Collaborative Genomics Research on Mental Disorders, 2017). Childhood trauma was operationalised as the total score on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein et al., 2003), and cannabis use was derived from the Cannabis Experience Questionnaire (Barkus, Stirling, Hopkins, & Lewis, 2006).

Missing data

Missing data were handled via multiple imputation (MI) by fully-conditional specification using chained equations (Little & Rubin, 2002; Sterne et al., 2009). Analyses were conducted post-imputation, combining estimates across 25 imputed data sets using Rubin's rule (White, Royston, & Wood, 2011). We included all covariates and several auxiliary variables in our MI algorithm (online Supplementary Methods).

Statistical analyses

We first presented descriptive statistics using χ2 tests and Mann–Whitney U tests (MWU), including investigating patterns of missingness by case–control status. We used polychoric correlations to describe associations between confounders and exposures in the control sample. We used multinomial regression to examine associations between ethnicity and other covariates. Following MI, we fitted sequential multilevel logistic regression models, with random intercepts at the centre level to account for the hierarchical nature of the dataset (individuals within centres), to investigate the association between ethnicity and case–control status, as follows:

-

•

Crude (univariable) association between case–control status and ethnicity

-

•

Model A: adjusted for a priori confounders (age, sex, paternal age, parental history of psychosis, cannabis use and childhood trauma)

-

•

Model B: Model A + social disadvantage (parental SES, education level, relationship status, living arrangements)

-

•

Model C: Model B + linguistic distance

-

•

Model D: Model C + self-perceived discrimination.

We re-ran our models substituting ethnicity for first- v. later-generation migrant status, and using our secondary outcomes. We performed sensitivity analyses on complete cases only for the primary outcome (using inverse probability weights to account for the sampling design, see online Supplementary Methods). We presented odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) where appropriate, and analysed data using Stata 14 (StataCorp, 2015).

The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) checklist (von Elm et al., 2007) and the original analysis plan, approved internally by the EU-GEI team in August 2016, are included in online Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

Results

We recruited 1130 cases and 1497 controls into the study (Di Forti et al., 2019). Following exclusion of participants with missing linguistic distance (N = 2 cases, 0.2%; N = 2 controls, 0.1%), cases from our Paris centre (where no controls were recruited, N = 36, 3.1%) and cases without OPCRIT (n = 4, 0.4%), the final sample size was 2583 (N = 1088 cases, N = 1495 controls; 98.3% of total recruited). A total of 761 (70.0%) cases presented with a non-affective psychotic disorder, and 306 (28.1%) with an affective psychotic disorder. A further 21 (1.9%) cases presented with psychosis not otherwise specified and were not included for secondary outcome analysis. Controls were broadly representative of the population-at-risk on sex and ethnic minority status, but were younger than the population-at-risk (online Supplementary Results and Supplementary Table S4).

Missing data

The proportion of missing covariate data was generally low (Table 1), ranging from two participants (0.1%) on age, to 301 (11.7%) on parental history of psychosis. Cases were more likely to be missing data on paternal age [n = 140 (12.9%) v. n = 55 (3.6%)], cannabis use [n = 29 (2.7%) v. n = 16 (1.1%)], childhood trauma [n = 89 (8.2%) v. n = 12 (0.8%)], relationship status [n = 10 (0.9%) v. n = 1 (0.1%)] and self-perceived discrimination [n = 87 (8.0%) v. n = 66 (4.4%)], but not on other covariates (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of exposures and covariates by case-control status.

| Variable | Controls n (%) | Cases n (%) | χ2; p-value/MWUa; p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Median (IQR) | 33 (26–47) | 29 (22–37) | MWU: 9.28, p < 0.0001 |

| Missing | 2 (0.1%) | – | ||

| Sex | Men | 705 (47.2%) | 671 (61.7%) | χ2: 53.30, p < 0.0001 |

| Women | 790 (52.8%) | 417 (38.3%) | ||

| Missing | – | – | ||

| Paternal age | Median (IQR) | 31 (27–35) | 31 (27–36) | MWU: −0.59, p = 0.56 |

| Missing (%) | 55 (3.6%) | 140 (12.9%) | ||

| Childhood trauma | Median (IQR) | 31 (27–38) | 39 (32–49) | MWU: −16.70, p < 0.0001 |

| Missing (%) | 12 (0.8%) | 89 (8.2%) | ||

| Cannabis use | Yes | 702(46.9%) | 683 (62.8%) | χ2: 79.76, p < 0.0001 |

| No | 777 (51.9%) | 376 (34.6%) | ||

| Missing | 16 (1.1%) | 29 (2.7%) | ||

| Parental history of psychosis | Yes | 23 (1.5%) | 68 (6.3%) | χ2: 43.67, p < 0.0001 |

| No | 1307 (87.4%) | 884 (81.3%) | ||

| Missing | 165 (11.0%) | 136 (12.6%) | ||

| Generational status | Not applicable (majority) | 1081 (72.3%) | 639 (58.2%) | χ2: 53.87, p < 0.0001 |

| First generation | 218 (15.6%) | 238 (21.8%) | ||

| Second generation | 196 (13.1%) | 215 (19.7%) | ||

| Missing | – | – | ||

| Ethnicity | White majority | 1084 (72.4%) | 634 (58.3%) | χ2: 70.99, p < 0.0001 |

| Black | 132 (8.3%) | 168 (15.4%) | ||

| Mixed | 96 (6.4%) | 107 (9.8%) | ||

| Asian | 33 (2.2%) | 33 (3.1%) | ||

| North African | 25 (1.7%) | 45 (4.1%) | ||

| Other | 25 (1.7% | 29 (2.8%) | ||

| White otherb | 100 (6.7%) | 72 (6.8%) | ||

| Missing | – | – | ||

| Parental SES | Professional | 440 (29.4%) | 242 (22.2%) | χ2: 45.16, p < 0.0001 |

| Intermediate | 315 (21.1%) | 209 (19.2%) | ||

| Lower | 386 (25.8%) | 287 (26.4%) | ||

| Routine | 2226 (15.1%) | 186 (17.1%) | ||

| Never worked | 3 (0.2%) | 15 (1.4%) | ||

| Not classified | 60 (4.0%) | 64 (2.9%) | ||

| Missing | 65 (4.4%) | 85 (7.8%) | ||

| Level of education | Postgraduate | 209 (14.0%) | 52 (4.8%) | χ2: 251.45, p < 0.0001 |

| Undergraduate | 343 (22.9%) | 122 (11.2%) | ||

| Vocational | 236 (15.8%) | 192 (17.6%) | ||

| Tertiary | 431 (28.8%) | 254 (23.3%) | ||

| School qualifications | 197 (13.2%) | 280 (25.7%) | ||

| School, no qualifications | 72 (4.8%) | 177 (16.3%) | ||

| Missing | 7 (0.5%) | 11 (1.0%) | ||

| Relationship status | Yes | 1333 (89.0%) | 733 (67.4%) | χ2: 189.09, p < 0.0001 |

| No | 161 (10.8%) | 345 (31.7%) | ||

| Missing | 1 (0.2%) | 10 (0.9%) | ||

| Living arrangements | Yes | 1218 (81.5%) | 742 (68.1%) | χ2: 60.70, p < 0.0001 |

| No | 257 (17.2%) | 323 (29.7%) | ||

| Missing | 20 (1.3%) | 23 (2.0%) | ||

| Linguistic distance | Yes | 144 (9.6%) | 186 (17.1%) | χ2: 31.48, p < 0.0001 |

| No | 1351 (90.4%) | 902 (82.9%) | ||

| Missing | – | – | ||

| Discrimination | Median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | MWU: −4.76, p < 0.0001 |

| Missing | 66 (4.4%) | 87 (8.0%) | ||

MWU: Mann–Whitney U test used to test for differences in median value between cases and controls.

White other refers to white minority participants (see Supplemental Table 1).

Demographic characteristics

Cases were more likely than controls to be black, mixed, North African or of ‘other’ ethnicity (χ2 71.0, p < 0.01; Table 1). Controls had higher education (χ2 251.5, p < 0.01), were more likely to have ever been in a relationship (χ2 189.1, p < 0.01) and to have lived with someone other than their parents (χ2 60.7, p < 0.01). Cases reported greater linguistic distance (χ2 31.5, p < 0.01) and discrimination (MWU −4.8, p < 0.01), were younger (MWU 9.3, p < 0.01), more likely to be male (χ2 53.3, p < 0.01), to have smoked cannabis (χ2 79.8, p < 0.01), to have a parental history of psychosis (χ2 43.7, p < 0.01), to have experienced childhood trauma (MWU −16.7, p < 0.01) and to have lower parental SES (χ2 45.2, p < 0.01) than controls. We found no difference in paternal age (MWU −0.6, p = 0.56). Correlations between exposures and confounders in the control sample were generally very weak, and are detailed in online Supplementary Table S5.

Multinomial regression using the white majority as the reference category revealed that all ethnic minority groups reported greater linguistic distance and discrimination than the white majority (Table 2), being highest in North African (ORlinguistic distance 5.41, 95% CI 4.72–6.10) and ‘other’ ethnic minority groups (ORdiscrimination 1.59, 95% CI 1.40–1.82). The distribution of linguistic distance by ethnic group and generational status can be found in online Supplementary Figs 4 and 5. Findings for social disadvantage were more mixed. Participants from black, mixed and North African ethnic backgrounds had lower parental SES than the white majority, in contrast to participants from Asian, white minority and ‘other’ ethnicities. Similar patterns were apparent for education and relationship status (Table 2). While most ethnic minority groups reported more childhood trauma than the white majority, there was no evidence of higher lifetime cannabis use in any ethnic minority group; further, only participants of black ethnicity reported a greater parental history of psychosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multinomial regression of ethnicity on other covariates

| Ethnic minority group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | Mixed | Asian | North African | Other | White minority | |

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Discrimination (0–12) | 1.51 (1.40–1.62) | 1.18 (1.06–1.32) | 1.28 (1.09–1.51) | 1.50 (1.32–1.71) | 1.59 (1.40–1.82) | 1.27 (1.14–1.42) |

| Linguistic distance | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 2.45 (2.92–3.97) | 1.64 (0.87–2.39) | 4.86 (4.19–5.53) | 5.41 (4.72–6.10) | 4.61 (3.95–5.33) | 4.96 (4.41–5.51) |

| Parental SES | ||||||

| Professional | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Intermediate | 0.97 (0.67–1.41) | 1.21 (0.71–2.07) | 0.81 (0.45–1.46) | 2.55 (1.08–6.03) | 1.13 (0.54–2.34) | 0.81 (0.53–1.27) |

| Lower | 0.87 (0.62–1.24) | 1.92 (1.21–3.05) | 0.22 (0.09–0.56) | 2.66 (1.18–604) | 0.73 (0.34–1.56) | 0.71 (0.47–1.08) |

| Routine | 1.48 (1.02–2.15) | 4.42 (2.78–7.02) | 0.51 (0.22–1.20) | 4.64 (2.00–10.76) | 1.09 (0.47–2.49) | 0.68 (0.40–1.15) |

| Never worked | 1.86 (0.53–7.26) | 5.22 (1.35–20.19) | n/a | 11.63 (2.17–62.46) | n/a | 0.90 (0.11–7.09) |

| Not classified | 1.20 (0.65–2.16) | 2.50 (1.26–5.00) | n/a | 0.69 (0.09–5.51) | 0.68 (0.15–3.05) | 0.69 (0.30–1.57) |

| Level of education | ||||||

| Postgraduate | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Undergraduate | 1.90 (1.01–3.61) | 1.48 (0.61–3.57) | 0.51 (0.24–1.10) | 0.80 (0.22–2.88) | 0.46 (0.18–1.16) | 0.67 (0.22–0.62) |

| Vocational | 2.74 (1.46–5.15) | 1.95 (0.82–1.65) | 0.44 (0.19–1.01) | 2.80 (0.93–8.40) | 0.80 (0.34–1.85) | 0.36 (0.20–0.62) |

| Tertiary | 2.09 (1.13–3.86) | 2.69 (1.20–6.04) | 0.34 (0.17–0.73) | 1.40 (0.46–4.25) | 0.33 (0.13–0.82) | 0.41 (0.26–0.66) |

| School qualifications | 2.43 (1.29–4.57) | 4.51 (2.01–10.13) | 0.49 (0.22–1.08) | 2.30 (0.76–6.99) | 0.57 (0.23–1.40) | 0.39 (0.23–0.67) |

| No qualifications | 5.43 (2.82–40.42) | 9.41 (4.11–21.52) | 0.30 (0.08–1.08) | 3.55 (1.09–11.56) | 0.71 (0.24–2.12) | 0.45 (0.22–0.89) |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 0.67 (0.49–0.89) | 0.67 (0.48–0.95) | 0.76 (0.42–1.36) | 0.45 (0.27–0.76) | 0.74 (0.39–1.38) | 1.64 (1.01–2.67) |

| Living arrangements | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.30 (0.96–1.75) | 1.51 (1.04–2.19) | 1.14 (0.63–2.05) | 1.23 (0.68–2.19) | 2.07 (0.97–4.41) | 3.50 (2.03–6.01) |

| Age | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.97 (0.95–0.98) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.98 (0.95–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Male | 1.07 (0.83–1.36) | 0.85 (0.63–1.14) | 1.14 (0.70–1.87) | 1.95 (1.17–3.26) | 1.19 (0.70 −2.04) | 0.97 (0.71–1.33) |

| Paternal age | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) |

| Childhood trauma | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) |

| Cannabis use | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 0.89 (0.69–1.13) | 0.64 (0.48–0.85) | 0.87 (0.57–1.43) | 1.10 (0.38–1.79) | 1.27 (0.73–2.20) | 1.25 (0.90–1.73) |

| Parental psychosis | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 1.85 (1.07–3.19) | 1.18 (0.58–2.42) | – | 0.40 (0.05–2.87) | 0.73 (0.11–4.72) | 1.18 (0.51–2.77) |

Odds ratios are relative to the White majority group.

Odds ratios in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Multivariable modelling

In unadjusted models, ethnic minority status was associated with increased odds of psychotic disorders (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.69–2.43), being highest for North African (OR 3.72, 95% CI 2.18–6.34) and black participants (OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.88–3.28) (Table 3). Greater social disadvantage, linguistic distance (OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.52–2.48) and self-perceived discrimination (OR per unit increase: 1.20, 95% CI 1.12–1.27) also showed strong univariable associations with psychosis risk (Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds of psychotic disorders by exposure status following incremental covariate adjustment

| Model | Crude | Model Aa | Model Bb | Model Cc | Model Dd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White native | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| All minorities | 2.03 (1.69–2.43) | 1.62 (1.32–1.98) | 1.54 (1.24–1.92) | 1.23 (0.96–1.59) | 1.21 (0.94–1.56) |

| Black | 2.49 (1.88–3.28) | 1.85 (1.36–2.52) | 1.53 (1.10–2.13) | 1.32 (0.94–1.85) | 1.29 (0.92–1.82) |

| Mixed | 2.29 (1.67–3.15) | 1.74 (1.23–2.45) | 1.41 (0.97–2.05) | 1.34 (0.92–1.96) | 1.32 (0.91–1.93) |

| Asian | 1.74 (1.05–2.88) | 1.64 (0.95–2.81) | 2.03 (1.13–3.65) | 1.44 (0.77–2.68) | 1.42 (0.76–2.65) |

| North-African | 3.72 (2.18–6.34) | 3.12 (1.73–5.61) | 2.58 (1.38–4.84) | 1.69 (0.86–3.33) | 1.65 (0.84–3.26) |

| Other | 1.88 (1.08–3.30) | 1.34 (0.73–2.46) | 1.51 (0.79–2.89) | 1.10 (0.56–2.18) | 1.06 (0.54–2.11) |

| White other | 1.24 (0.89–1.72) | 1.13 (0.79–1.62) | 1.35 (0.92–1.99) | 0.93 (0.60–1.44) | 0.93 (0.60–1.44) |

| Parental SES | n/a | ||||

| Professional | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Intermediate | 1.24 (1.00–1.62) | 1.07 (0.81–1.41) | 1.08 (0.82–1.43) | 1.08 (0.82–1.43) | |

| Lower | 1.49 (1.18–1.88) | 1.11 (0.84–1.46) | 1.12 (0.85–1.48) | 1.12 (0.85–1.48) | |

| Routine | 1.74 (1.33–2.27) | 0.94 (0.69–1.29) | 0.97 (0.71–1.34) | 0.97 (0.71–1.34) | |

| Never worked | 8.37 (2.38–29.43) | 3.20 (0.83–12.39) | 3.31 (0.84–13.14) | 3.33 (0.84–13.26) | |

| Not classified | 2.35 (1.57–3.53) | 2.10 (1.32–3.34) | 2.11 (1.33–3.36) | 2.11 (1.33–3.36) | |

| Level of education | n/a | ||||

| Postgraduate | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Undergraduate | 1.59 (1.05–2.23) | 1.42 (0.95–2.13) | 1.42 (0.95–2.1) | 1.43 (0.95–2.14) | |

| Vocational | 3.49 (2.42–5.06) | 2.96 (1.73–3.89) | 2.59 (1.73–3.89) | 2.57 (1.71–3.86) | |

| Tertiary | 2.92 (2.04–4.18) | 1.86 (1.26–2.75) | 1.86 (1.26–2.76) | 1.86 (1.26–2.75) | |

| School qualifications | 7.05 (4.87–10.20) | 4.77 (3.18–7.15) | 4.81 (3.20–7.22) | 4.81 (3.20–7.22) | |

| No qualifications | 13.04 (8.46–20.09) | 8.24 (5.07–13.37) | 8.15 (5.02–13.25) | 8.17 (5.03–13.28) | |

| Relationship status | n/a | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.26 (0.21–0.32) | 0.34 (0.27–0.44) | 0.34 (0.26–0.44) | 0.34 (0.26–0.44) | |

| Living arrangements | n/a | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.47 (0.39–0.58) | 0.83 (0.64–1.06) | 0.81 (0.62–1.04) | 0.80 (0.62–1.03) | |

| Linguistic distance | n/a | n/a | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.94 (1.52–2.48) | 1.91 (1.33–2.76) | 1.89 (1.31–2.73) | ||

| Discrimination (0–12) | 1.20 (1.12–1.27) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1.04 (0.97–1.12) |

Odds ratios in bold are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Model A is adjusted for covariates (age, sex, their interaction, paternal age, childhood trauma, cannabis use, parental history of psychosis).

Model B is further adjusted for indicators of social disadvantage (paternal SES, level of education, relationship status and living arrangements).

Model C is further adjusted for linguistic distance.

Model D is further adjusted for discrimination.

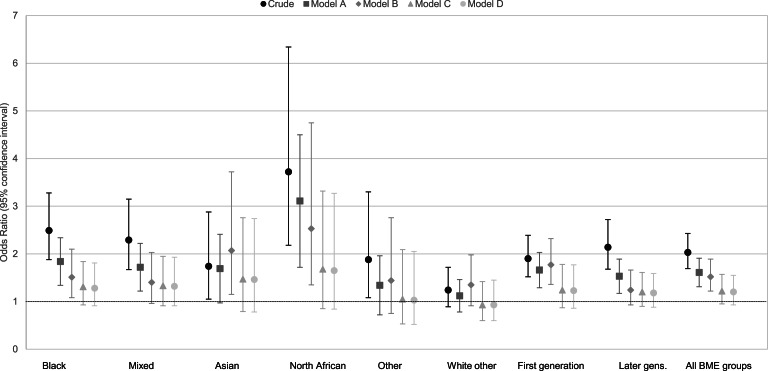

Adjustment for a priori confounders (Model A, Table 3 and Fig. 1) led to some attenuation in psychosis risk in the overall ethnic minority group (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.32–1.98), though excess odds remained for participants of North African (OR 3.12, 95% CI 1.73–5.61), black (OR 1.85, 95% CI 1.36–2.52) and mixed (OR 1.74, 95% CI 1.23–2.45) ethnicities, principally driven by childhood trauma (data available from authors). Adjustment for social disadvantage (Model B, Table 3) led to further attenuation in risk for all ethnic minority groups (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.24–1.92), but negatively confounded the association between Asian ethnicity and psychosis to increase the risk (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.13–3.65). Additional adjustment for linguistic distance (Model C, Table 3), which remained strongly associated with psychosis risk (OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.33–2.76), further attenuated psychosis risk in all ethnic minority groups (OR 1.23, 95% CI 0.96–1.59), such that for any specific ethnic minority group, we were unable to reject the null hypothesis. The addition of self-perceived discrimination did not alter ORs, and discrimination itself was no longer associated with psychosis risk in a multivariable model (Model D: OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.97–1.142).

Fig. 1.

Odds of psychotic disorders, by ethnic group following incremental covariate adjustment. Model A: adjusted for covariates (age, sex, their interaction, paternal age, childhood trauma, cannabis use, parental history of psychosis). Model B: Model A+adjustment for indicators of social disadvantage (parental SES, level of education, relationship status and living arrangements). Model C: Model B+adjustment for linguistic distance. Model D: Model C+adjustment for discrimination.

Risk in first- v. later-generation migrant groups

In crude models, first- and later-generation ethnic minority groups were at similarly elevated risk of psychotic disorder (online Supplementary Table S6), which persisted after adjustment for a priori confounders. Incremental adjustment for other covariates suggested that later-generation groups were no longer at increased odds of psychosis after adjustment for social disadvantage (Model B: OR 1.24; 95% CI 0.93–1.66), but the risk remained elevated for first-generation migrants (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.39–2.38) until further adjustment for linguistic distance (Model C: OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.89–1.83; online Supplementary Table S6 and Fig. S1).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes followed a similar pattern to our primary outcome, with crude excess odds observed in the overall ethnic minority group for both non-affective (OR 2.08, 95% CI 1.70–2.57; online Supplementary Table S7) and affective psychotic disorders (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.40–2.42, online Supplementary Table S8). These associations were attenuated following adjustment for a priori confounders and social disadvantage, and were no longer increased following adjustment for linguistic distance (OR non-affective disorders: 1.17, 95% CI 0.87–1.58; OR affective disorders: 1.22, 95% CI 0.85–1.74). Due to the smaller sample sizes for each outcome, these estimates were accompanied by less precision, particularly for affective psychotic disorders.

Sensitivity analyses

Model building (Models A–D) was repeated on the weighted complete-case sample for all psychotic disorders; results were similar to imputed analyses (online Supplementary Table S9).

Discussion

We showed that a greater frequency of psychotic disorders typically observed in several ethnic minority groups (Selten et al., 2020) may be attributable to markers of social disadvantage and linguistic distance. The latter appeared to have stronger effects in first-generation migrants, while the former had greater magnitude amongst second- and later-generation ethnic minority groups. These findings were independent of several other putative confounders included in our models and were replicated across dichotomised diagnostic categories.

Strengths and limitations

Our data were taken from a large, international case–control study with well-characterised socio-environmental exposures, using population-based control samples. Although missing data were generally low, we used MI to minimise the loss of precision or selection biases, which may have been introduced in complete-case analyses. We took a multilevel modelling approach to accurately estimate standard errors in nested data across sites, and an a priori modelling approach to reduce the plausibility of type I error.

Controls were broadly representative of the population-at-risk by sex and minority status, but were – on average – younger. Weighted complete-case sensitivity analyses, however, did not alter the interpretation of our results. We were unable to investigate representativeness for other covariates such as SES, as these were not available for the population-at-risk consistently across all six countries. We used the same validated instruments across settings, and standardised data-entry to minimise other forms of differential measurement bias. To minimise recall bias, we operationalised covariates broadly, or used well-validated measures. While we cannot exclude the possibility of differential recall between cases and controls, we have no reason to believe this would have differed by ethnicity. We acknowledge likely within-group heterogeneity inherent to our definition of ethnicity. Narrower definitions of ethnicity (e.g. black Caribbean) were unfeasible due to small sample sizes resulting from country-specific minority groups. Nevertheless, the consistency of our findings across each broad ethnic group increases the validity of our observations.

The association between linguistic distance and psychosis was novel, but needs considering in light of limitations, including the validity of this measure; linguistic distance showed apparent validity, being greater amongst all ethnic minority groups (with the exception of people from mixed ethnic backgrounds) than the majority population. Treating linguistic distance as a binary variable may have led to some residual confounding, but was necessary because of substantial skew in the underlying two items capturing linguistic distance. We also acknowledge that our measure may not have captured all aspects of cultural distance, including outsider status, and will not provide a complete account of the excess risk of psychotic disorders observed in second- and later-generation migrants (Bourque, van der Ven, & Malla, 2011; Selten et al., 2020), because one would expect little linguistic distance from the majority population. Indeed, our findings suggested that social disadvantage was a bigger driver of excess odds of psychosis in this group. Nonetheless, our results suggest further development and validation of measures which capture this construct is warranted. We also suggest that acculturative experiences, which are partly shaped by both social disadvantage and linguistic distance, should be studied in suitable longitudinal cohorts. Such designs would also minimise further limitations of this study, including the issue of non-collapsibility of ORs, a statistical property of ORs which might preclude interpreting them as risks. Nevertheless, given that the rare disease assumption is likely satisfied in our study, we do not believe non-collapsibility will have affected our results (Burgess, 2017; Vanderweele, 2016). Longitudinal research will also provide prospectively collected data to disentangle the potential role of reverse causality, particularly around social disadvantage and psychosis.

Comparison with existing literature

Increased odds of psychotic disorders in ethnic minority groups are consistent with existing literature (Anderson, Cheng, Susser, McKenzie, & Kurdyak, 2015; Bourque et al., 2011; Kirkbride et al., 2012; Selten et al., 2020), particularly for people with black and mixed ethnic backgrounds (Kirkbride et al., 2012; Kirkbride, Hameed, Ioannidis, et al., 2017; Selten et al., 2019). Literature on the North African group is mixed, with strong evidence of increased incidence in Moroccan groups in the Netherlands (Veling et al., 2006), although not France (Tortelli et al., 2014). Our finding of excess odds of psychotic disorder in Asian groups in Europe supports some previous findings (Coid et al., 2008; Kirkbride et al., 2012; Kirkbride, Hameed, Ioannidis, et al., 2017), but, as for all ethnicities, will mask considerable heterogeneity within this group. No evidence of excess risk was found amongst white minority groups, in line with some (Bourque et al., 2011; Kirkbride, Hameed, Ioannidis, et al., 2017) but not all studies (Dykxhoorn et al., 2018). Such differences highlight the importance of investigating variability in minority group experiences in different contexts in future studies.

Previous studies have suggested that increased psychosis risk in ethnic minority groups is only partially attenuated by current SES (Kirkbride et al., 2008; Kirkbride, Hameed, Ioannidis, et al., 2017), consistent with our results. Here, social disadvantage had pernicious effects on psychosis risk, consistent with the previous work on this issue (Morgan et al., 2008), and our results are consistent with a socio-developmental model of psychosis in minorities (Morgan, Charalambides, Hutchinson, & Murray, 2010); our work suggests that psychosocial and cultural factors may be integral to such models. In our study, discrimination was strongly associated with the odds of psychotic disorder, and was more common amongst all ethnic minority groups. However, after adjusting for other markers of psychosocial disempowerment, no direct effect of discrimination remained. This partially accords with evidence from a previous study which found that whilst discrimination was associated with excess psychosis risk in ethnic minorities (Veling et al., 2007), it did not fully explain an account for it, while a further case–control study found no association (Veling, Hoek, & Mackenbach, 2008). Previous studies have reported that a greater proportion of people from one's own ethnic group in a given community attenuate psychosis risk for individuals from an ethnic minority background (Bécares, Nazroo, & Stafford, 2009). This so-called ‘ethnic density’ effect is thought to operate through social support garnered from one's own ethnocultural group (Bécares et al., 2009), but was not the focus of our study. However, our results suggest that in addition to such a mechanism, social and linguistic barriers which could limit people's capability to participate fully in the society may also be associated with psychosis risk. Neither mechanism needs to be mutually exclusive, and we require theoretical models which recognise the realistic complexity through which different contextual factors affect psychosis risk.

Interpretation of findings

One possible explanation of our findings is that social disadvantage and linguistic distance increase psychosis risk in some ethnic minority groups via mechanisms such as psychosocial disempowerment (Marmot, 2015) or social defeat (Selten & Cantor-Graae, 2005). Multiple disadvantage is disproportionately concentrated in minority groups (Wilson, 2010) and in concert with cultural factors (Smaje, 1996) may act to disenfranchise and distance minority groups from the majority population who often hold a disproportionate balance of power to achieve desirable economic, social, health or other outcomes. Marmot has suggested that such disempowerment processes may account for several strong social gradients in health and disease (Marmot, 2006; Marmot, 2015), including for mental health disorders(Williams, Costa, & Leavell, 2017); through this lens, ethnic disparities in psychosis risk could arise as a function of being exposed to greater social or cultural barriers in achieving autonomy and control over one's environment (Marmot, 2006; Marmot, 2015; Public Health England & UCL Institute of Health Equity, 2017).

In reality, we expect a complex interplay of such factors will contribute to such psychosocial disempowerment processes, and further observational and experimental studies are required to replicate our findings, investigate potential psychosocial mechanisms and understand if they are associated with neurobiological signatures relevant to psychosis (Howes & Kapur, 2014). There is already some evidence that outsider status [as indexed via migrant status (Egerton et al., 2017), childhood trauma (Egerton et al., 2016; Oswald et al., 2014) or hearing impairment (Gevonden et al., 2014)] is associated with increased dopamine sensitisation in healthy individuals (Selten, Booij, Buwalda, & Meyer-Lindenberg, 2017); a mechanism important in pathogenesis of psychotic disorders, and is particularly sensitive to environmental insults (Howes & Kapur, 2009). If proven, our results would have import for the aetiology of psychotic disorders.

Our results also have the potential to inform public mental health strategies to prevent psychosis, by identifying individual and societal factors amenable to intervention. This may include universal strategies aimed at reducing structural inequalities in health, and selected strategies to protect vulnerable populations from experiencing exposure to factors which lead to psychosocial disempowerment (Arango et al., 2018). Our results are amongst the first to provide traction on factors which may drive excess rates of psychotic disorders in minority ethnic groups and, if replicated, potentially provide vital clues about ameliorable risk factors for intervention.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Jenneke van der Wal (JvdW; Leiden University) for her advice on the appropriateness of the method of approximating linguistic distance. We would also like to thank Professor Jean-Paul Selten (Maastricht University/Rivierduinen Institute for Mental Health Care) for his critique of earlier versions of this manuscript.

Group members

The European Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) WP2 Group members include Ulrich Reininghaus, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands, and Department of Health Service and Population Research, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, England; Kathryn Hubbard, MSc, Department of Health Service and Population Research, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, England; Stephanie Beards, PhD, Department of Health Service and Population Research, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, England; Simona A. Stilo, MSc, Department of Health Service and Population Research, and Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, England; Giada Tripoli, MSc, Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London, England, and Department of Experimental Biomedicine and Clinical Neuroscience, Section of Psychiatry, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy; Mara Parellada, MD, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Pedro Cuadrado, MD, Villa de Vallecas Mental Health Department, Villa de Vallecas Mental Health Centre, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor/Hospital Virgen de la Torre, Madrid, Spain; José Juan Rodríguez Solano, MD, Puente de Vallecas Mental Health Department, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor/Hospital Virgen de la Torre, Centro de Salud Mental Puente de Vallecas, Madrid, Spain; Angel Carracedo, MD, PhD, Fundación Pública Galega de Medicina Xenómica, Hospital Clínico Universitario, Santiago de Compostela, Spain; Enrique García Bernardo, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Laura Roldán, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Gonzalo López, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Bibiana Cabrera, MSc, PhD, Barcelona Clinic Schizophrenia Unit, Neuroscience Institute, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona. Barcelona. Spain. CIBERSAM, Spain; Esther Lorente-Rovira, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Universidad de Valencia, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental, Valencia, Spain; Paz Garcia-Portilla, MD, PhD, Department of Medicine, Psychiatry Area, School of Medicine, Universidad de Oviedo, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental, Oviedo, Spain; Javier Costas, PhD, Fundación Pública Galega de Medicina Xenómica, Hospital Clínico Universitario, Santiago de Compostela, Spain; Estela Jiménez-López, MSc, Department of Psychiatry, Servicio de Psiquiatría Hospital ‘Virgen de la Luz’, Cuenca, Spain; Mario Matteis, MD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Marta Rapado, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Emiliano González, PhD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Covadonga Martínez, MD, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Emilio Sánchez, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Mª Soledad Olmeda, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, School of Medicine, Universidad Complutense, Investigación Sanitaria del Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental), Madrid, Spain; Nathalie Franke, MSc, Department of Psychiatry, Early Psychosis Section, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Jean-Paul Selten, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands, and Rivierduinen Institute for Mental Health Care, Leiden, the Netherlands; Fabian Termorshuizen, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, the Netherlands, and Rivierduinen Centre for Mental Health, Leiden, the Netherlands; Daniella van Dam, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Early Psychosis Section, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Elles Messchaart, MSc, Rivierduinen Centre for Mental Health, Leiden, the Netherlands; Marion Leboyer, MD, PhD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor’, Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; Franck Schürhoff, MD, PhD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor’, Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; Stéphane Jamain, PhD, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; Flora Frijda, MSc, Etablissement Public de Santé Maison Blanche, Paris, France; Grégoire Baudin, MSc, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor’, Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France; Aziz Ferchiou, MD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor’, Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France; Baptiste Pignon, MD, AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier ‘Mondor’, Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; Jean-Romain Richard, MSc, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U955, Créteil, France, and Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France; Thomas Charpeaud, MD, Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France, CMP B CHU, Clermont Ferrand, France, and Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France; Anne-Marie Tronche, MD, Fondation Fondamental, Créteil, France, CMP B CHU, Clermont Ferrand, France, and Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France; Pierre-Michel Llorca MD, PhD, EA 7280 Npsydo, Université Clermont Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France; Daniele La Barbera, MD, PhD, Department of Experimental Biomedicine and Clinical Neuroscience, Section of Psychiatry, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy; Giovanna Marrazzo, MD, PhD, Unit of Psychiatry, ‘P. Giaccone’ General Hospital, Palermo, Italy; Lucia Sideli, PhD, Department of Experimental Biomedicine and Clinical Neuroscience, Section of Psychiatry, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy; Crocettarachele Sartorio, PhD, Unit of Psychiatry, ‘P. Giaccone’ General Hospital, Palermo, Italy; Laura Ferraro, PhD, Department of Experimental Biomedicine and Clinical Neuroscience, Section of Psychiatry, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy; Fabio Seminerio, MSc, Department of Experimental Biomedicine and Clinical Neuroscience, Section of Psychiatry, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy; Cristina-Marta Del-Ben, MD, PhD, Division of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience and Behaviour, Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; Camila Marcelino Loureiro, MD, Departamento de Neurociências e Ciencias do Comportamento, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, and Núcleo de Pesquina em Saúde Mental Populacional, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil; Rosana Shuhama, PhD, Departamento de Neurociências e Ciencias do Comportamento, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, and Núcleo de Pesquina em Saúde Mental Populacional, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil; Federico Suprani, MD, Transcultural Psychosomatic Tream (BoTPT), Department of Surgical and Medical Sciences, Bologna University, Bologna, Italy; Mirella Ruggeri, MD, PhD, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; Sarah Tosato, MD, PhD, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; Chiara Bonetto, PhD, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; and Doriana Cristofalo, MA, Section of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement, University of Verona, Verona, Italy.

Financial support

The European Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) Project was funded by grant agreement Health-F2-2010-241909 (Project EU-GEI) from the European Community's Seventh Framework programme. The Brazilian study was funded by grant 2012-0417-0 from the São Paulo Research Foundation. Dr Jongsma is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant ES/S011714/1). Dr Kirkbride is funded by the Wellcome Trust and Royal Society (Grant 101272/Z/13/Z). Dr Jongsma and Professor Jones are funded by the National Institute of Health Research Collaboration of Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care East of England. Professor Rutten is funded by the Netherlands Scientific Organisation (VIDI award number 91718336). Dr Jongsma and Dr Kirkbride are supported by the National Institute for Health Research, University College London Hospital, Biomedical Research Centre. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000029X.

click here to view supplementary material

Conflict of interest

Dr Arango has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants from Acadia, Ambrosseti, Gedeon Richter, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Merck, Otsuka, Roche, Servier, Shire, Schering Plough, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Sunovion and Takeda. Professor Jones has received honoraria from Janssen and Ricordati. Professor Sir Robin Murray is the UK editor of Psychological Medicine. All remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Akerlof, G., & Kranton, R. (2011). Identity economics: How our identities shape our work, wages and well-being. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K. K, Cheng, J., Susser, E., McKenzie, K. J., & Kurdyak, P. (2015). Incidence of psychotic disorders among first-generation immigrants and refugees in Ontario. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187(9), E279–E286. 10.1503/cmaj.150494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K. K, Flora, N., Archie, S., Morgan, C., & McKenzie, K. (2014). A meta-analysis of ethnic differences in pathways to care at the first episode of psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 130, 257–268. 10.1111/acps.12254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango, C., Díaz-Caneja, C. M., McGorry, P. D., Rapoport, J., Sommer, I. E., Vorstman, J. A., … Carpenter, W. (2018). Preventive strategies for mental health. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 5, 591–604. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkus, E. J., Stirling, J., Hopkins, R. S., & Lewis, S. (2006). Cannabis-induced psychosis-like experiences are associated with high schizotypy. Psychopathology, 39, 175–178. 10.1159/000092678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bécares, L., Nazroo, J., & Stafford, M. (2009). The buffering effects of ethnic density on experienced racism and health. Health & Place, 15, 700–708. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., … Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra, D., Hilwig, M., Hossein, B., Marceau, H., Neehall, J., Leff, J., … Der, G. (1996). First-contact incidence rates of schizophrenia in Trinidad and one-year follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry, 169(5), 587–592. 10.1192/bjp.169.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque, F., van der Ven, E., & Malla, A. (2011). A meta-analysis of the risk for psychotic disorders among first- and second-generation immigrants. Psychological Medicine, 41(5), 897–910. 10.1017/S0033291710001406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, L., Henssler, J., Müller, M., Wall, S., Gabel, D., & Heinz, A. (2019). Risk of psychosis among refugees. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(11), 1133–1140. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, S. (2017). Estimating and contextualizing the attenuation of odds ratios due to non collapsibility estimating and contextualizing the attenuation of odds ratios due to non collapsibility. Communications in Statistics – Theory and Methods, 46(2), 786–804. 10.1080/03610926.2015.1006778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Candelo, N., Croson, R. T. A., & Li, S. X. (2017). Identity and social exclusion: An experiment with Hispanic immigrants in the U.S. Experimental Economics, 20, 460–480. 10.1007/s10683-016-9492-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coid, J. W., Kirkbride, J. B., Barker, D., Cowden, F., Stamps, R., Yang, M., & Jones, P. B. (2008). Raised incidence rates of all psychoses among migrant groups: Findings from the East London First Episode Psychosis Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(11), 1250–1258. 10.1001/archpsyc.65.11.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2017). International migration report 2017. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/migreport.asp.

- Di Forti, M., Quattrone, D., Freeman, T. P., Tripoli, G., Gayer-Anderson, C., Quigley, H., … Murray, R. M. (2019). The contribution of cannabis use to variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe (EU-GEI): A multicentre case-control study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(5), 427–436. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30048-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykxhoorn, J., Hollander, A.-C., Lewis, G., Magnusson, C., Dalman, C., & Kirkbride, J. B. (2019). Risk of schizophrenia, schizoaffective, and bipolar disorders by migrant status, region of origin, and age-at-migration: A national cohort study of 1.8 million people. Psychological Medicine, 49(11) 2354–2363. 10.1017/S0033291718003227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerton, A., Howes, O. D., Houle, S., Mckenzie, K., Valmaggia, L. R., Bagby, M. R., … Mizrahi, R. (2017). Elevated striatal dopamine function in immigrants and their children: A risk mechanism for psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(2), 293–301. 10.1093/schbul/sbw181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerton, A., Valmaggia, L. R., Howes, O. D., Day, F., Chaddock, C. A., Allen, P., … McGuire, P. (2016). Adversity in childhood linked to elevated striatal dopamine function in adulthood. Schizophrenia Research, 176(2–3), 171–176. 10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon, P., Kirkbride, J. B., Morgan, C., Dazzan, P., Morgan, K., Lloyd, T., … Murray, R. M. (2006). Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in ethnic minority groups: Results from the MRC AESOP Study. Psychological Medicine, 36(11), 1541–1550. 10.1017/S0033291706008774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M., & Baum, F. (2010). The social determinants of mental health: Implications for research and health promotion. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44(January), 1057–1063. 10.3109/00048674.2010.509311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gevonden, M., Booij, J., van den Brink, W., Heijtel, D., van Os, J., & Selten, J.-P. (2014). Increased release of dopamine in the striata of young adults with hearing impairment and its relevance for the social defeat hypothesis of schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(12), 1364–1372. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, E., & Rose, D. (2006). The European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC) User Guide. Colchester, Essex.

- Hayes, J. F., Marston, L., Walters, K., King, M. B., & Osborn, D. P. (2017). Mortality gap for people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: UK-based cohort study 2000–2014. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 211(3), 175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickling, F. W. (1995). The incidence of first-contact schizophrenia in Jamaica. British Journal of Psychiatry, 167(December 1992), 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickling, F. W., McKenzie, K., Mullen, R., & Murray, R.M. (1999). A Jamaican psychiatrist evaluates diagnoses at a London psychiatric hospital. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 283–285. Retrieved from http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/bjprcpsych/175/3/283.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorthøj, C., Stürup, A. E., McGrath, J. J., & Nordentoft, M. (2017). Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(4), 295–301. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes, O. D., & Kapur, S. (2009). The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: Version III – The final common pathway. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 35(3), 549–562. 10.1093/schbul/sbp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes, O. D., & Kapur, S. (2014). A neurobiological hypothesis for the classification of schizophrenia: Type a (hyperdopaminergic) and type b (normodopaminergic). British Journal of Psychiatry, 205(1), 1–3. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.138578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongsma, H. E., Gayer-Anderson, C., Lasalvia, A., Quattrone, D., Mulè, A., Szöke, A., … Kirkbride, J. B. (2018). Treated incidence of psychotic disorders in the multinational EU-GEI Study. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(1), 36-46. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride, J. B., Barker, D., Cowden, F., Stamps, R., Yang, M., Jones, P. B., & Coid, J. W. (2008). Psychoses, ethnicity and socio-economic status. British Journal of Psychiatry, 193(1), 18–24. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.041566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride, J. B., Errazuriz, A., Croudace, T. J., Morgan, C., Jackson, D., Boydell, J., … Jackson, D. (2012). Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in England, 1950–2009: A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE, 7(3), e31660. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride, J. B., Fearon, P., Morgan, C., Dazzan, P., Morgan, K., Tarrant, J., … Jones, P. B. (2006). Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: Findings from the 3-center AeSOP study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(3), 250–258. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride, J. B., Hameed, Y., Ankireddypalli, G., Ioannidis, K., Crane, C. M., Nasir, M., … Jones, P. B. (2017). The epidemiology of first-episode psychosis in early intervention in psychosis services: Findings from the Social Epidemiology of Psychoses in East Anglia [SEPEA] study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(2), 143–153. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkbride, J. B., Hameed, Y., Ioannidis, K., Ankireddypalli, G., Crane, C. M., Nasir, M., … Jones, P. B. (2017). Ethnic minority status, age-at-immigration and psychosis risk in rural environments: Evidence from the SEPEA Study. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(6), 1251–1261. 10.1093/schbul/sbx010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczan, Z. (2016). Does identity matter? Migration Studies, 4(1), 116–145. 10.1093/migration/mnv021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G., Croft-Jeffreys, C., & David, A. (1990). Are British psychiatrists racist? British Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 410–415. Retrieved from http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/bjprcpsych/157/3/410.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little, R., & Rubin, D. (2002). Statistical analyses with missing data (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett, R. (1997). MRC sociodemographic schedule. London: Institute of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. (2015). The health gap. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. G. (2006). Status syndrome. JAMA, 295(11), 1304. 10.1001/jama.295.11.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Goldblatt, P., Boyce, T., McNeish, D., Grady, M., & Geddes, I.. (2010). Fair Society, Healthy Lives.. London, UK: Institute of Health Equity. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, C, Charalambides, M., Hutchinson, G., & Murray, R. M. (2010). Migration, ethnicity, and psychosis: Toward a sociodevelopmental model. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(4), 655–664. 10.1093/schbul/sbq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, C, Fearon, P., Lappin, J., Heslin, M., Donoghue, K., Lomas, B., … Dazzan, P. (2017). Ethnicity and long-term course and outcome of psychotic disorders in a UK sample: The ÆSOP-10 study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 211(2), 88–94. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.193342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, C., Kirkbride, J., Hutchinson, G., Craig, T., Morgan, K., Dazzan, P., … Fearon, P. (2008). Cumulative social disadvantage, ethnicity and first-episode psychosis: A case-control study. Psychological Medicine, 38(12), 1701. 10.1017/S0033291708004534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazroo, J., & Karlsen, S. (2003). Patterns of identity among ethnic minority people: Diversity and commonality. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 26(5), 902–930. [Google Scholar]

- NIHM Center for Collaborative Genomics Research on Mental Disorders (2017). NIMH genetics – FIGS. Retrieved July 21, 2017, from NIHM Repository and Genomics Resource website: https://www.nimhgenetics.org/interviews/figs/.

- Ødegaard, Ø (1932). Emigration and insanity. Acta Psychiatrica Neurologica Scandinavica (Suppl.), 4, 1–206. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald, L. M., Wand, G. S., Kuwabara, H., Wong, D. F., Zhu, S., & Brasic, J. R. (2014). History of childhood adversity is positively associated with ventral striatal dopamine responses to amphetamine NIH public access. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 231(12), 2417–2433. 10.1007/s00213-013-3407-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England, & UCL Institute of Health Equity (2017). Psychosocial pathways and health outcomes: Informing action on health inequalities. Retrieved from www.gov.uk/phe.

- Savage, M., Devine, F., Cunningham, N., Taylor, M., Li, Y., Hjellbrekke, J., … Miles, A. (2013). A new model of social class? Findings from the BBC's Great British Class Survey Experiment. Sociology, 47(2), 219–250. 10.1177/0038038513481128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selten, J.-P., Booij, J., Buwalda, B., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2017). Biological mechanisms whereby social exclusion may contribute to the etiology of psychosis: A narrative review. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(2), 287–292. 10.1093/schbul/sbw180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten, J.-P., & Cantor-Graae, E. (2005). Social defeat: Risk factor for schizophrenia? British Journal of Psychiatry, 187, 101–102. Retrieved from http://mighealth.net/nl/images/c/c4/Stelt2.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten, J.-P., van der Ven, E., & Termorshuizen, F. (2020). Migration and psychosis: A meta-analysis of incidence studies. Psychological Medicine, 50(2), 303–313. 10.1017/S0033291719000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaje, C. (1996). The ethnic patterning of health: New directions for theory and research. Sociology of Health & Illness, 18(2), 141–9889. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/1467-9566.ep10934605. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp (2015). Stata statistical software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Netherlands (2018). StatLine – Welvaart van particuliere huishoudens; kerncijfers. Retrieved July 30, 2018, from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83739NED/table?ts=1532517736257.

- Sterne, J. A. C., White, I. R., Carlin, J. B., Spratt, M., Royston, P., Kenward, M. G., … Carpenter, J. R. (2009). Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ, 338. 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortelli, A., Morgan, C., Szöke, A., Nascimento, A., Skurnik, N., Monduit De Caussade, E., … Murray, R. M. (2014). Different rates of first admissions for psychosis in migrant groups in Paris. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology., 49(7), 1109. 10.1007/s00127-013-0795-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderweele, T. J. (2016). Mediation analysis: A practitioner's guide. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veling, W., Hoek, H. W., & Mackenbach, J. P. (2008). Perceived discrimination and the risk of schizophrenia in ethnic minorities. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(12), 953–959. 10.1007/s00127-008-0381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veling, W., Selten, J. P., Susser, E., Laan, W., Mackenbach, J. P., & Hoek, H. W. (2007). Discrimination and the incidence of psychotic disorders among ethnic minorities in The Netherlands. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(4), 761–768. 10.1093/ije/dym085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veling, W., Selten, J. P., Veen, N., Laan, W., Blom, J. D., & Hoek, H. W. (2006). Incidence of schizophrenia among ethnic minorities in the Netherlands: A four-year first-contact study. Schizophrenia Research, 86(1–3), 189–193. 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E., Altman, D., Egger, M., Pocock, S., Gøtzsche, P., Vandenbrouke, J., & STROBE Initiative. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet, 370(9596), 1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West, J., & Graham, J. L. (2004). A linguistic-based measure of cultural distance and its relationship to managerial values. Management International Review; Third Quarter, 44(443), 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- White, I. R., Royston, P., & Wood, A. M. (2011). Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine, 30(4), 377–399. 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. R., Costa, M., & Leavell, J. P. (2017). Race and mental health: Patterns and challenges. In Scheid T. L. & Brown T. N. (Eds.), A handbook for the study of mental health (2nd ed., pp. 268–290). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. R., Yu, Y., Jackson, J. S., & Anderson, N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, W. J. (2010). More than just race: Being black and poor in the inner city. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zandi, T., Havenaar, J. M., Smits, M., Limburg-Okken, A. G., van Es, H., Cahn, W., … van den Brink, W. (2010). First contact incidence of psychotic disorders among native Dutch and Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands: Influence of diagnostic bias. Schizophrenia Research, 119(1–3), 27–33. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172000029X.

click here to view supplementary material