Abstract

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a ubiquitous component in the manufacturing of plastic. It is commonly found in food and beverage containers. Because of its broad exposure and evidence that it may act as an estrogen-like molecule, many have studied its potential effects. Epidemiological studies have found an association between in utero BPA exposure and onset of childhood asthma. Our previous work suggested BPA treated mice induced asthma-like symptoms in both mothers and their in utero exposed pups. To better understand mechanisms and consequences of BPA exposure, we use a proteomics approach. Using both CD4+ T cells from a in vivo model of BPA exposure and an in vitro epithelial cell model, we identified activation of both innate and adaptive immune signaling in BPA. Furthermore our proteomic results from our multigenerational mouse model study implicates aberrant immune activation across several generations. We propose the following, BPA can active an innate viral immune response by upregulating ZDHHC1 and its binding partner, stimulator of interferon-gamma (STING). It also has additional histone epigenetic perturbations suggesting a role for epigenetic inheritance of these immune perturbations.

Introduction

Xenoestrogens, also referred to as environmental estrogens (EEs), and other endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs), are considered environmental toxicants that can have hormone disruptive effects 1. EEs, such as BPA, are widely used in the manufacture of many consumer products, such as food and beverage containers 2, and have been shown to act as ligands of the estrogen receptor in a variety of cell types 3. Early life exposure to EEs may lead to the development of innate and adaptive immune responses that foster asthma and other lung diseases 4. For, example, it was reported that intratracheal exposure to BPA during early development enhanced allergic inflammation of the airways and promoted T helper type 2 (Th2)-bias of the immune system with increased cytokines-interleukin (IL)-4, −5 and −13 and production of IgE, all of which are characteristics of allergic asthma 4d, 5.

In most cases, allergic asthma is developed in early childhood 6 and can continue into adulthood. We have previously shown that maternal exposure to BPA promoted the development of asthma-like symptoms in the offspring of mothers exposed to BPA during birth 7. This led us to wonder if BPA could affect multiple generations and whether epigenetic inheritance might play a critical role in transgenerational inheritance 8. Along these lines, it is interesting to note that an increase in the prevalence of asthma among children started in the 1970s, 20 years (approximately one generation) after large-scale BPA production had started in several industrialized regions of the world in 1950s 9.

Maternal exposure to EEs can also disrupt the early stages of egg production and development 10. Interestingly, some report that there may be inherited effects following exposure to EEs and other EDCs. These inherited effects can include genetic effects, such as altering DNA double strand break formation, as well as potential epigenetic changes resulting in developmental abnormalities 11. A classic example of this is diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure which can cause an increased risk of subfertility, birth defects, and tumor induction in the reproductive tract which can propagate for at least two subsequent generations 12. Perinatal exposure of mice to DES resulted in genital tract abnormalities and cancers in the first generation (F0) which were transmitted to the third generation 13. Much like other endocrine disruptors, BPA is suspected to play a role in the inheritance of an allergic asthma phenotype via epigenetic reprogramming but the mechanisms remain incompletely understood.

To further understand the effects of BPA exposure we use a proteomics approach. Proteomics has previously been used in testicular germ cells and spermatogonia 14, livers and sera 15, and in thyroid tissues 16 to show alterations in these tissues. To our knowledge, no proteomic studies on BPA-exposure and its effect on immune cells have been reported. In this paper, we report the use of both labeled and label-free proteomic approaches to characterize and better understand how BPA exposure induces an apparent immune response that can be heritable. Our findings suggest the effect of BPA exposure can elicit an innate viral immune response pathway by upregulating ZDHHC1, a protein involved in the normal innate immune activation to DNA viruses that can generate a type I interferon response 17. Among the perturbed pathways, innate and adaptive immune signaling, oxidative phosphorylation, and pathways involved in histone/chromatin modifications were upregulated. Furthermore, these pathways were observed through at least three generations of BPA-exposed mice.

Experimental Procedures

In vivo BPA exposure study

Female BALB/c mice were obtained from Harlan (Houston, TX) and housed in pathogenfree conditions in the animal research facility of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB; Galveston, TX). All experimentation was conducted under a protocol approved by the UTMB Institutional Review Board. The animals were treated humanely and with regard for alleviation of suffering. Mice were fed a casein-based diet (Research Diet, New Brunswick, NJ) to eliminate estrogenic effects in the typical, soy-based mouse diet for one week before BPA loading, and continued until the end of the study 18. We used animal cages made of polysulfone (Tecniplast, Buguggiate, Italy). We tested these cages for contamination with BPA by adding water to a cage and maintaining it for one week at room temperature. The concentration of BPA in the water was assayed with a highly sensitive GC-MS method (detection limit, 0.01 pg/mL). There were no detectable levels of BPA in the water. Female BALB/c mice were given 10 μg/mL BPA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 1% ethanol solution in their drinking water for seven weeks, throughout their pregnancy and lactation. All mice were given 1% ethanol solution in their drinking water for seven weeks until the study was completed. We chose the concentration of BPA to feed the female mice based on previous studies 7a, 19 in which total body burden of free BPA in the mothers and pups were similar to those described in human tissues and fluids. Only the F0 mothers and F1 mice were directly exposed to BPA, the mother fed directly and the F1 pups were exposed in utero.

Isolation of CD4+T cells from mouse spleens

CD4+T cells were isolated from splenic mononuclear cells using magnetic beads for CD4 negative selection (StemCell, Vancouver, BC Canada). The purity of separated cells was analyzed by Flow cytometry analyses using PE-anti-mouse CD3a and PE-Cy5-anti-CD4 (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). The purities of isolated CD4+T cells were normally above 75% (Figure S2).

Cell culture and BPA treatment

Caco-2 cells originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown in 100 x 17mm Nunclon™ Delta dishes (ThermoFisher Scientific, ca#150350) with Gibco® DMEM media (ThermoFisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA, ca#11965-092) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, ca#F2442500ML) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Corning Cellgro™, ThermoFisher Scientific, ca#30-004-CI) at 37 °C under 5% CO2, in a Galaxy 170R CO2 incubator (Eppendorf, Enfield, CT, USA).

CD4+ T cells enriched from human T lymphoblast CCL-119 cells, originally purchased from ATCC (>75% CD4+ determined by flow cytometry) were grown in T75 CELLSTAR TC Flasks (Phenix Research, Cander, NC, ca# TCG-658175) with RPMI 1640 media (ATCC, ca#30-2001) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution. After the cells were ~50% confluent, they were grown in phenol red free in RPMI with charcoalstripped fetal bovine serum from two days before treatments. Cells were treated with BPA (Sigma-Aldrich, ca#239658-50G) in DMSO, E2 (Sigma-Aldrich, ca#E8875), VD3 (1α, 25-dihydroxy Vitamin D3, EMD-Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA, ca#679101) in DMSO or their combination for 72 hrs. The variation of the final concentrations was indicated in the Results section. The stock solutions of BPA, E2, and VD3 were all 0.1 mM.

Sample preparation for mass spectrometry

The cell pellets were lysed in radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) supplemented with 1% Nonidet P40, PMSF (0.2 mM), and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, one tablet per 10 mL). After sonication with a probe sonicator (Qsonica, model CL-188; 3 x 30 bursts at 40 Hz amplitude) the cell suspensions were incubated in ice for 2h, and then they were centrifuged and the supernatant transferred into clean tubes. The protein concentration in the supernatant of each tube was determined by Bicinchoninic Acid Assay (BCA). An aliquot of supernatant containing 50-100 μg of protein was treated by the addition of 200 mM Tris (2-CarboxyEthyl) Phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) solution (Sigma-Aldrich) to a final concentration of 20 mM and then incubated in Vortex at 50 °C for 30 min, followed by carbamidomethylation with 25 mM iodoacetamide (final concentration) in the dark for 1h. Four volumes of pre-cooled acetone (−20 °C) was added to precipitate proteins at −20 °C overnight. The proteins were pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min and washed once with 1 mL pre-cooled (−20 °C) acetone. After being air-dried overnight, the proteins were resuspended in 25 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 7.8) and digested with an appropriate amount of trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, protein:enzyme = 25:1 (weight)) overnight. For LFQ experiments of CD4+T cells, the protein digests after acidification with 1% formic acid (FA) were directly subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis on the LTQ-Orbitrap Elite instrument. For TMT-10 labeling experiments of Caco-2 cells, to each digest, 0.8 mg of TMT-10 (ThermoFisher Scientific, ca#90110) reagent was added. Eight out of the ten labeling reagents were used: 127N and 127C were used to label the control samples; 128N and 128C were used to label the 100 nM BPA treated samples; 129N and 129C were used to label the 100 nM VD3 treated samples; and 130N and 130C were used to label the samples treated with both 100 nM BPA and 200 nM VD3. We treated the first pair of samples (the BPA-treated verse the control) as the first set of BPA experiment (BPA-1) and the second pair of samples (the BPA+VD3 co-treated verses VD3-treated which served as a second control sample) as the second set of BPA experiment (BPA-2). We did two preparations resulting in four BPA experiments: BPA1 and BPA2. After incubation with the TMT-10 reagents for 2hr, 20 μL of 5% hydroxylamine was added to stop the labeling reaction. After all the samples with different labeling in one preparation were combined, the solution was acidified and fractionated into six fractions with Thermo’s strong cation-exchange (SCX) spin-columns with a KCl gradient from 0 to 0.5 M in 20% acetonitrile (ACN). The last elution solution was 5% ammonia hydroxide. Next, the fractions were dried under vacuum to remove ACN and then desalted by Thermo spin-columns with Hypercarb™. The ammoniaeluted fraction was acidified by 1% FA before desalting, and 0.8 mL of 60% ACN was used to elute peptides from the desalting column, for each sample. The eluted peptides were vacuumdried, reconstituted in 30 μL of 0.1% FA, and then subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. Because the reporter ions generated from TMT-10-127C, −128C, 129C, and 130C labeled samples were not consistent with the Western-blot and qPCR data, we excluded these four and used TMT10Nlabeled samples (TMT-127N, −128N, −129N and −130N) for quantification. Accordingly, we described the relative mass tag quantification approach as TMT4N as only these channels were used in our analysis. Our overall experimental design strategy is illustrated in Figure S1.

LC-MS/MS operating conditions

HPLC:

Peptides were separated by a reverse-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) on the ThermoFisher EASY-nLC™ 1200 System, using two-column setup: a trap column (2 cm long C18, 100 μm i.d., Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) followed by a C18 analytical columns (ProteoPep II, 15 cm long, 75 μm i.d., 15 μm tip, 5 μm particle size, Thermo Scientific) with a 400 nL/min flow rate and 165 min gradient (solvent A, 0.1% FA in water; solvent B, 0.1% FA in ACN from 2-95% solvent B.

Mass Spectrometry:

The analysis of TMT4N labeling samples was carried out on the ThermoFisher’s QExactive mass spectrometer, which was set to acquire data at 35,000 resolution (FWHM) for the parent full-scan MS followed by data-dependent high collision energy dissociation (HCD) MS/MS for the top 15 most abundant ions acquired at 7500 resolution and low mass fixed at 80 Da. The analysis of the LFQ samples was carried out on the ThermoFisher’s hybrid linear ion trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Orbitrap Elite). The Orbitrap mass analyzer was set to acquire data at 60,000 resolution (FWHM) for the parent full-scan mass spectrum (scan range: m/z 350-1600) followed by collision-induced dissociation (CID) MS/MS spectra for the top 15 most abundant ions acquired at 15,000 resolutions. Other settings were generic and could be referred to our previous publications 20.

Protein search and quantification

Proteins were identified and quantified through the Proteome Discoverer 2.0 platform (Thermo), using Sequest HT (employing the Homo Sapiens Swiss-Prot database, release date 7/2015, containing 45,391 entries or mouse Swiss-Prot Homo database). For TMT4N analysis, the Sequest search parameters were: Carbamidomethylation of cysteine and TMT-10 modification of peptide N-terminus and lysine were set as fixed modifications and oxidation of methionine and deamination of asparagine and glutamine were set as variable modifications; trypsin was the protease selected, and up to two missed cleavages were allowed. Mass tolerance for the precursor ions was 10 ppm, and for the MS/MS, 0.01 Da. Only peptides with a minimum length of four amino acids were considered, and peptides were filtered for a maximum false discovery rate of 5%. At least one unique peptide with posterior error probability of less than 0.05 was accepted for quantification using the TMT4N reporter ions, and proteins were grouped. LFQ analysis was carried out using the PEAKS 8.5 software. Protein intensity was calculated as the sum of all peptide peak areas for a protein group. The criteria for searching proteins were the same as for the TMT4N analysis except for no inclusion of TMT-10 modifications. The TMT4N proteomic raw and processed data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE 21 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD014275.

Statistical and bioinformatics analyses

Protein intensities were log2 normalized and statistical analysis was performed in Perseus 1.6.0.7 22. For CD4+T cells enriched from the spleens of BALB/c mice, we pooled biological replicates (n = 2-4) as after sorting by FACS, much less sample is recovered. We performed three technical replicates and filtered out proteins that did not occur at least twice in both the treated and untreated groups. Then the missing values were imputed from a normal distribution using the default settings in Perseus (Width 0.3, Down shift 1.8). Fold change significance was determined used a moderated t test. Briefly, the s0 value was set to 0.6 which essentially acts as a “fold change cutoff” of 1.5. Formally this weights the T-score such that very small but otherwise statistically significant fold changes are penalized and thus less likely to be considered statistically significant. Multiple test correction was done using a permutation-based FDR method with 250 random samples and set to 5%. A similar approach was used for the TMT data for Caco-2 cells except we had 10 technical replicates and the second technical replicate was removed due to an excess of missing values. s0 was instead set to 0.4 and no imputation was performed. The STRING database was used to identify enriched Reactome pathways by uploading a list of statistically significant upregulated proteins. Heatmaps were also generated in Perseus with the default settings (Preprocessing with K-means followed by calculating Euclidean distance with average linkage) with Z-score normalized values (log2 protein intensities transformed to units of standard deviation from the mean). Volcano plots were plotted using PRISM 8.2.1. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) was used to identify protein upstream regulators using a fold change cutoff of greater than 1.5 or less than 0.5. This same approach was used for the STRING database generation of enriched pathways and their protein-protein interaction networks. Enriched pathways were selected with an FDR threshold of at least 5%, as reported by the STRING-db server.

WB analyses and antibodies

Cell lysates containing ~30 μg of total protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. These were then probed with specific first antibodies followed by appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (#929-70020) from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE, USA). The fluorescence signals were detected with a LI-COR Odyssey imaging system. Band intensities were quantified using Odyssey imaging software version 3.0. Antibodies used were targeted to: ZDHHC1 (Polyclonal, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA, ca# NBP152187), β-Actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, ca#sc-47778), and GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, ca#sc-59540). Individual targeted proteins and the control (β-Actin or GAPDH) were probed on the same membrane.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Protein co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) was performed using the Abcam on-line protocol (http://www.abcam.com/protocols/immunoprecipitation-protocol-1). Here, anti-ZDHHC1 (5 μL) and anti-STING (5 μL) were used as the primary antibodies to respectively precipitate ZDHHC1 or STING proteins with 60 μL protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA, ca#SC-2003). WB was then performed for ZDHHC1 and STING, in both Co-IP samples.

qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was extracted using acid guanidinium phenol extraction (Tri Reagent; Sigma). Briefly, 1 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed using SuperScript III in a 20 μL reaction mixture. The remainder of the procedures was performed by following the protocol provided by Sigma. Relative changes in gene expression were quantified using the ΔΔCT method using gene-specific primers (shown in the table below). Data shown were the fold-changes in mRNA abundance normalized to cyclophilin. All qRT-PCR data presented were the mean ± S.D. from n=3 experiments.

| Sequence (5’- 3’) | Sequence (5’- 3’) | |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Set |

Forward | Reverse |

| ZDHHC1 | CAAGCCCTCCAACAAGACG | CCAAAGCCGATCACAGCAAAG |

| hPPIA (Control) | CCCACCGTGTTCTTCGACATT | GGACCCGTATGCTTTAGGATGA |

Results

1. BPA-perturbed proteome of isolated CD4+T cells from mice

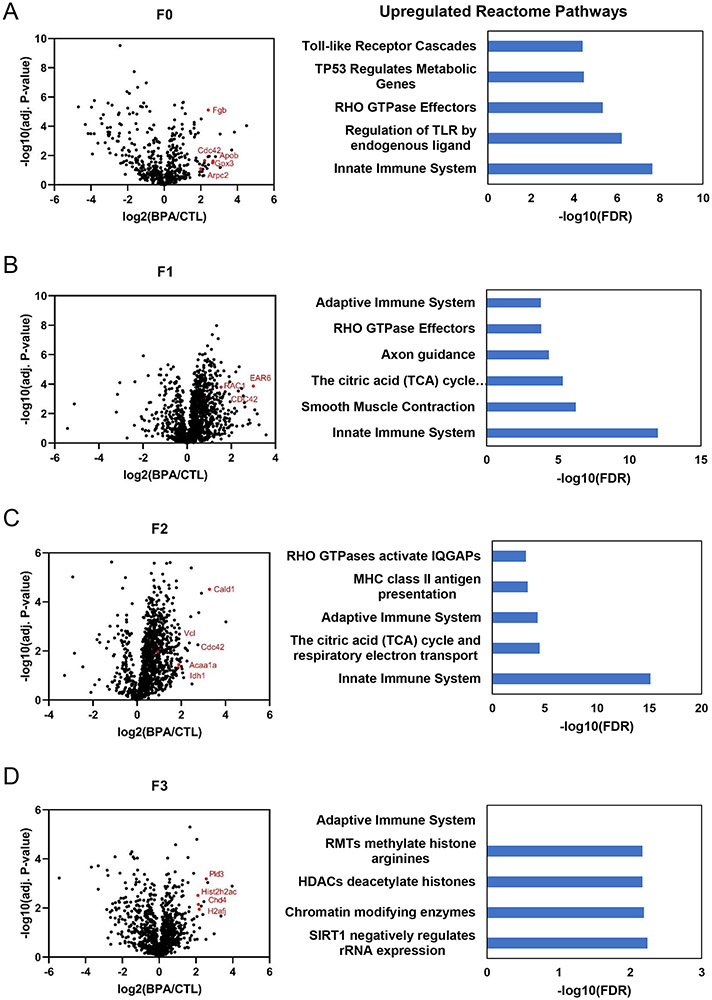

Our previous findings have suggested BPA exposure can result in anallergic asthma phenotype 7. To determine if these effects could be inherited over several generations, we performed a proteomic analysis of protein expression of CD4+T cells isolated from BPA exposed mice. Proteins in the whole cell lysates of CD4+T cells were used to compare protein expression in BPA-exposed mice versus protein expression in non-BPA exposed mice within the same generation, for up to three generations. The only generation directly given BPA were dams (F0) while their pups (F1) were exposed in utero. However, generations F2 and F3 were otherwise not exposed to BPA as the half-life of BPA is on the order of hours to days23 . Figure 1 shows the volcano plots of proteins quantified (Table S1). Proteins with statistically significant increased expression were submitted to STRING to identify enriched Reactome and (Table S2). We find that toll-like receptors, the innate immune system, and pathways related to an activated immune system (RHO GTPase effectors) in mothers given BPA are upregulated (Figure 1A). In subsequent generations we see consistent upregulation of the innate immune system or pathways related to migration of immune cells (RhoA) including proteins such as Rac1 and Cdc42. Interestingly, we see beginning in the F1 generation activation of the adaptive immune pathway which is observed out until the second generation (Figure 1B & C).

Figure 1. BPA activates innate and adaptive immune system and other transgenerational effects in vivo.

CD4+T cells isolated from BPA exposed mice were analyzed by label free proteomics and pathway analysis. Differential expression is displayed as a volcano plot using log2(fold change) of BPA treated mothers (F0) by giving 10ug/ml BPA in 1% ethanol drinking water versus control (1% ethanol drinking water) out to three generations (F1-F3).

Next we used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) for prediction of upstream activators (Figure S3, Table S6-S8). Upstream regulators such as IL5, CD38, Cell division cycle 42 (Cdc42) and Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) were activated with Z-score larger than 2 in mice directly exposed to BPA (F0). These cytokines and proteins are implicated in immune cell motility as well as Th2 skewing believed to be a major factor in the development of allergic asthma as well as BPA exposure24. Pathway analysis also indicated that antigen presentation, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative phosphorylation, phagosome maturation, remodeling of epithelial adherent junctions, and sirtuin signaling were enriched pathways, following BPA exposure of F0 mice (Figure S4-5, Table S5). For the pups and subsequent generations (F1-F3), upstream activators included CD38/ADP-Ribosyl Cyclase 1, Cdc42, IL-4, IL-5, retinoblastoma 1 (RB1), insulin receptor (INSR), serum response factor (SRF), estrogen related receptor alpha (Esrra) and Myc (Fig S3C-D). Among these regulators, IL-4 and IL-5 are highly expressed in eosinophils 25. Interestingly, a majority of the predicted upstream regulators have been reported to be associated with Th2 cells and other markers of asthma markers 26. Upstream regulators predicted to be downregulated, included the histone H3K4 trimethylation demethylase, KDM5A. KDM5A was consistently identified in BPA exposed animals F1-F3 to be downregulated suggesting H3K4 trimethylation may be elevated (Figure S3B-D). STRING analysis of protein-protein interaction networks show pathways such as oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis, focal adhesion, and phagosome are enriched (Figure S6). In addition, the top ten overrepresented canonical pathways identified by IPA similarly showed oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondria dysfunction, sirtuin signaling, and phagosome maturation, were over-represented BPA exposed F1-F3 mice (Figure S7).

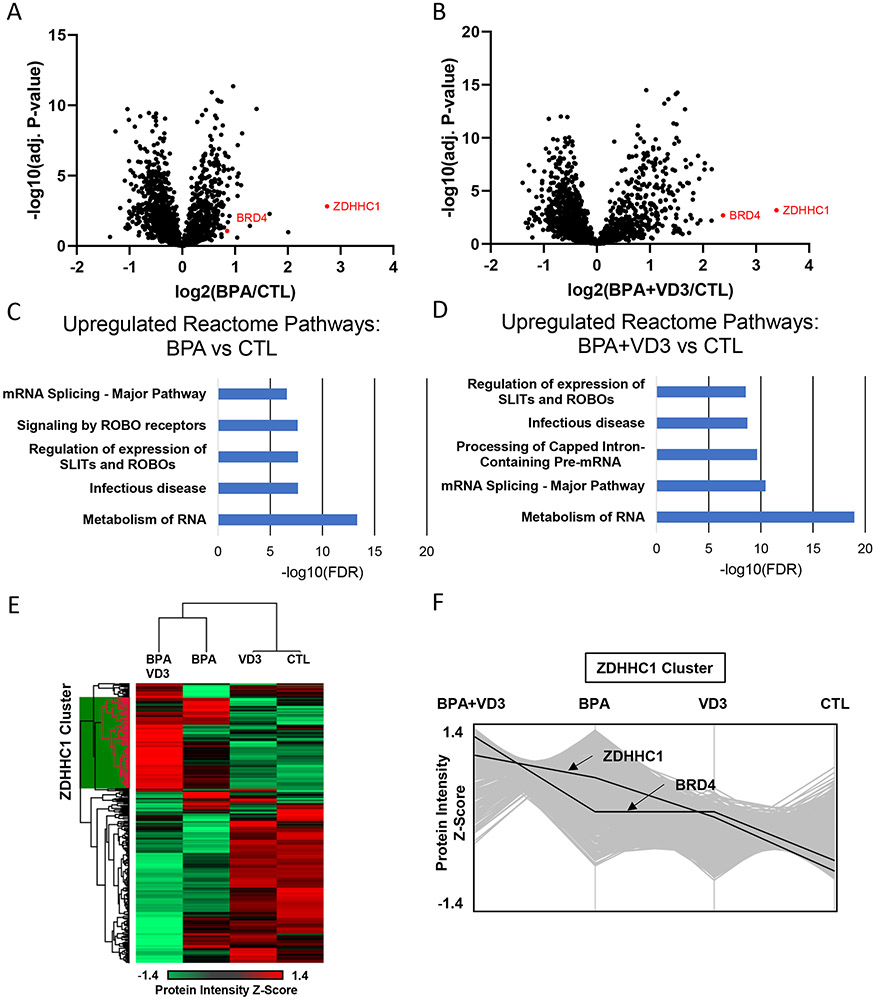

2. BPA-perturbed proteome of human Caco-2 cells determined by isobaric labeling mass spectrometry

To gain a deeper understanding of the physiologic and proteomic effects of BPA exposure we performed tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling with cation-exchanging fractionation proteomics of Caco-2 cells (Figure 2). Cells were treated either with vehicle or control which was dimethyl sulfoxide (127N), 100 nM BPA (128N isobaric tag), 100 nM VD3 alone (129N), 100 nM BPA and 100 nM VD3 (130N). Proteins in the whole cell extract were quantified by the reporter ion ratios using Proteome Discoverer as described in the Methods. In this experiment, more than 2,000 proteins were quantified (Table S15).

Figure 2. BPA activates an innate viral immune pathway in vitro.

TMT labeled proteomics of Caco-2 cells treated with BPA, VD3, or a combination.

A-B. Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes between BPA treated and control (vehicle/DMSO) as well as BPA plus VD3 versus control.

C-D. Enriched Reactome pathways using differentially expressed proteins in BPA versus Control and BPA plus VD3 versus control

E Hierarchical clustering of median average technical replicates of the four conditions (BPA+VD3, BPA, VD3, Control) represented as a heatmap. A large cluster of proteins increases in expression in BPA treated and particularly in BPA plus VD3 treatment. This cluster is referred to as the ZDHHC1 cluster.

F. A plot of the ZDHHC1 protein cluster identified in E. The Y-axis represents the Z-score, a relative measure of protein expression to its mean and standard deviation across all samples. This shows the trend of the proteins in the ZDHHC1 cluster tend to increase with BPA and BPA plus VD3 treatment, especially ZDHHC1 and BRD4.

We used Caco-2 cells as they are transformed colon epithelia and most BPA exposure is through it ingestion either in contaminated food products or drinking water 27. We identified that BPA exposure could affect the proteome of splenic CD4+ T cells but we were interested to see if BPA had any effect on colon epithelial-like cells as these would be the cells and tissues first exposed to BPA. As shown in Figure 2, ZDHHC1 was identified as the most upregulated protein in BPA-treated Caco-2 cells. Interestingly, BRD4 was also upregulated and both more so by treatment with activated Vitamin D3 (VD3) and BPA. ZDHHC1 and BRD4 are both known to be involved in the innate viral immune response to DNA and RNA viruses 17a, 28. Somewhat surprisingly, VD3 alone had a modest effect on the proteome as demonstrated by the heatmap and plotting of the relative protein intensity (Figure 2E & 2F). However, the combination of BPA and VD3 appears to have a mutual effect where they increase a large cluster of proteins already upregulated by BPA, including ZDHHC1 and BRD4 (Figure 2F). Overall, these findings are consistent with our in vivo data as we again see a similar activation of immune related pathways such as “infectious disease” and SLIT/Robo signaling which is important in the activation of leukocyte migration 29 (Figure 2C & 2D).

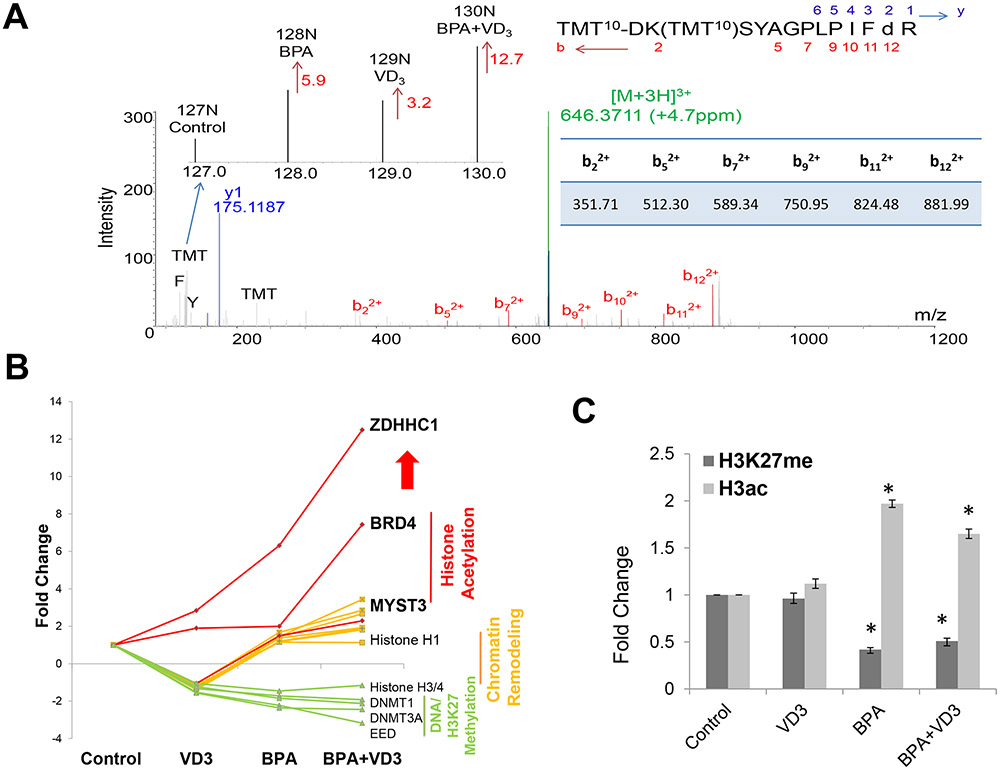

Given as an example, the MS/MS spectrum of the precursor ion at m/z 646.3711 (triply-charged) perfectly matched with a unique peptide of ZDHHC1 with the sequence of DKSYAGPLPIFDR in which doubly charged b ions were dominated (Figure 3A), aspartic acid (D) was deaminated and both the lysine ε-NH2 and the N-terminal NH2 were modified with the TMT tags; and the observation of the immonium ions of phenylalanine (F) at m/z 120.081 and tyrosine (Y) at m/z 136.076 further reinforced the assignment of the above ZDHHC1 peptide sequence. Isobaric labeling allows for the simultaneous relative quantification of this unique peptide. The ratio of the intensity of reporter ion 128N over the intensity of reporter ion 127N was 5.9 representing the fold change of ZDHHC1 expression induced by BPA; the ratio of the intensity of reporter ion 129N over the intensity of reporter ion 127N was 3.2, representing the fold change of ZDHHC1 expression induced by VD3; and the ratio of the intensity of reporter ion 130N over the intensity of reporter ion 127N was 12.7 representing the fold change of ZDHHC1 expression additively induced by both BPA and VD3.

Figure 3. Expression of ZDHHC1 and chromatin proteins in BPA in-vitro treated human Caco-2 cells.

A. MS/MS spectrum of a ZDHHC1 specific peptide detected in Caco-2 cells. The ratios of reporter ions represented the changes of protein expression induced by BPA, VD3 or their combination (BPA+VD3).

B. Fold change of ZDHHC1 and chromatin proteins regulated by BPA, VD3, and BPA+VD3.

C. Histone H3K18/23 diacetylation and H3K27 trimethylation measured by Parallel-Reaction-Monitoring (PRM).

Following a similar trend to that of ZDHHC1, histone acetyltransferases, BRD4 and MYST3, were upregulated by BPA and increasingly upregulated by BPA and VD3, while DNMT1, DNMT3A, EED, and histone H3/H4 were all downregulated (Figure 3B and Figure S8). DNMT1 and DNMT3A are DNA maintenance and de novo methyltransferases; EED is an essential component of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) that also includes histone H3K27 methyltransferases, the enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), and suppressor of zeste 12 (SUZ12). Downregulation of these methyltransferases would suggest a global reduction of histone H3K27 trimethylation and an increase in histone acetylation. To confirm protein expression changes to histone modifying enzymes would affect histone post-translationalmodifications, we employed our parallel-reaction-monitoring mass spectrometric method. Indeed we measured a significant reduction in H3K27 trimethylation and an overall increase in histone acetylation 30 (Figure 3C and Figure S9). In addition the two isoenzymes, 17β-HSD1 and 17β-HSD2, that exclusively catalyze the interconversion between sex steroids estrone (E1) and estradiol (E2) respectively, were differentially regulated by BPA, VD3 and their combination (Figure S9) 31. This may potentially explain how VD3 in combination with BPA or E2 can have a synergistic effect as metabolism of the active Estrogen receptor ligand, E2, is also affected.

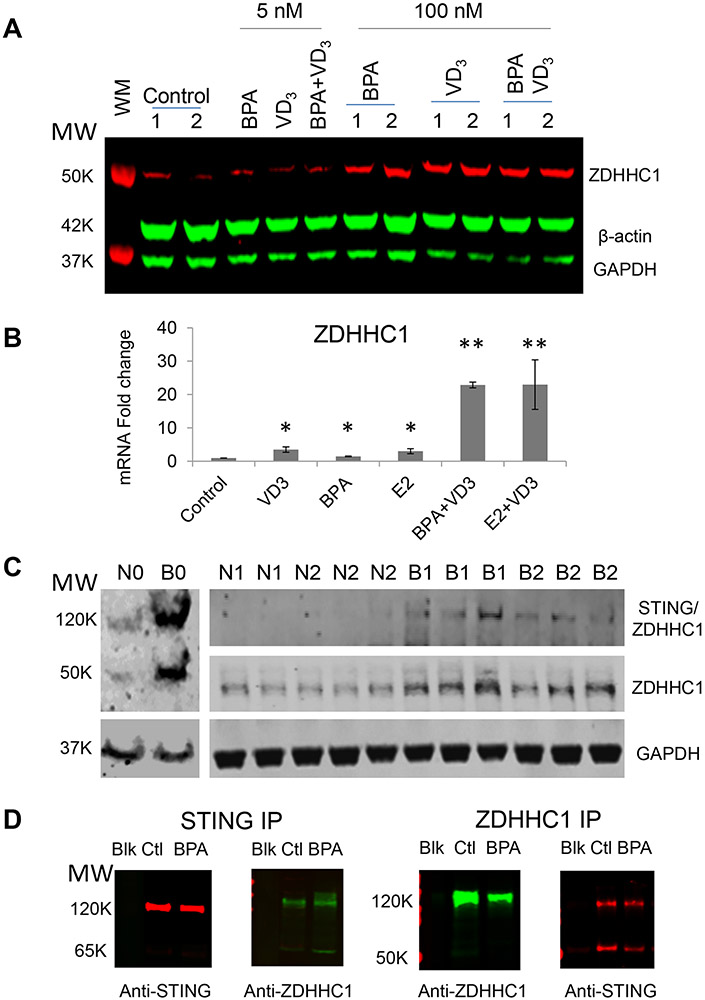

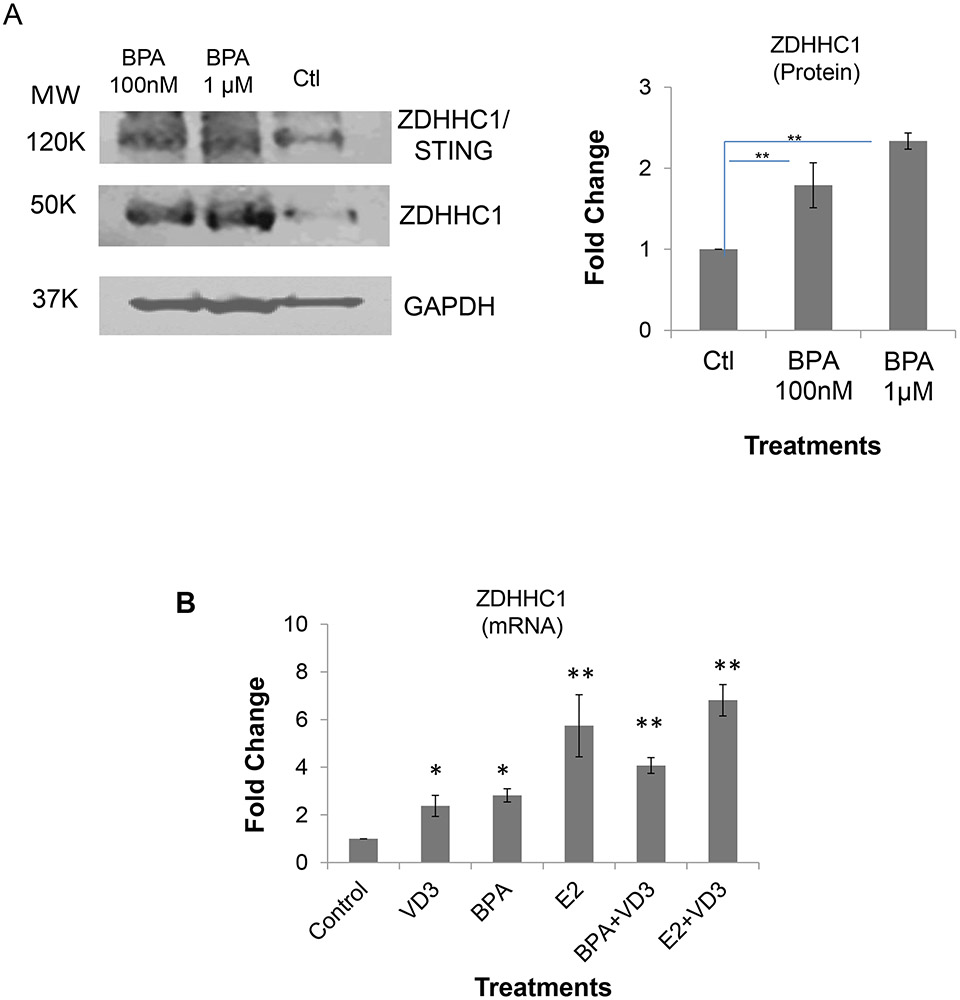

3. Validation of ZDHHC1 expression due to BPA exposure

To further support the mass spectrometric results, we performed western blots for ZDHHC1. As shown in Figure 4A, ZDHHC1 expression was increased 72 hours after BPA treatment in Caco-2 cells. In order to further confirm ZDHHC1 upregulation and to determine whether the expression of ZDHHC1 was also transcriptionally upregulated, we did qPCR analysis of mRNA levels in Caco-2 cells (Figure 4B). In our qPCR studies we also included additional positive controls with Estradiol (E2), the endogenous ligand for the Estrogen receptor to probe if binding to ERα may be responsible for the transcriptional expression of ZDHHC1. E2 and BPA both significantly upregulated ZDHHC1 expression by western blot and qPCR (Figure 4A & 4B). Consistent with our proteomic studies, cells treated with VD3 together with BPA, as well as E2, had further upregulated ZDHHC1 expression as compared to any individual treatment.

Figure 4. ZDHHC1 expression in BPA-treated human Caco-2 cells (in-vitro) and CD4+T cells (in vivo) isolated from BPA-exposed mouse spleens.

A. ZDHHC1 protein expression measured by WB in Caco-2 cells. β-actin and GAPDH were used as loading controls. Replicates shown are technical replicates.

B. ZDHHC1 gene expression measured by qPCR in Caco-2 cells.

C. ZDHHC1 protein expression measured by WB in CD4+T cells isolated from mouse spleens. “N” refers to untreated and “B” for BPA-fed mice while the numbers represent different generations of mice from the pups of the BPA-fed mice (F1) all the way to F3. The replicates shown are biological replicates.

D. Co-immunoprecipitation of STING and ZDHHC1 in U937 lymphoma T cells. WB analysis of STING (left) and ZDHHC1 (right) proteins in an anti-STING immunopreciptate of U937 cell lysates. WB analysis of ZDHHC1 (left) and STING (right) proteins in anti-ZDHHC1 immunoprecipitate of U937 cell lysates.

Although ZDHHC1 was detected in our in vitro proteomic studies of Caco-2 cells, it was not seen in our initial LFQ proteomic study of mouse CD4+ T cells. To determine if ZDHHC1 was nonetheless increased, we probed the protein lysates for ZDHHC1 protein expression with western blots. Figure 4C demonstrates BPA exposed mice from F0, F1, and F2 all expressed ZDHHC1 while untreated control mice did not. Furthermore, we identified a larger ~120kDa band present when probing with anti-ZDHHC1. We suspected this may be the dimer between ZDHHC1’s known binding partner STING/MITA, or Stimulator of Interferon Gamma17a.. Using a Co-IP analysis we confirmed this 120kDa bind is the ZDHHC1:STING complex (Figure 4D).

Next, we tested whether ZDHHC1 could be upregulated by BPA in human CD4+Tcells in vitro. CD4+T cells that were enriched by cell sorting with anti-CD4 antibody from human T lymphoblast CCL-119 cells treated with 100 nM and 1.0 μM BPA for three days. Whole cell lysates from three separate preparations were analyzed by WB. As shown in Figure 5A and Figure S10, ZDHHC1 expression, relative to GAPDH, was upregulated by 1.8 and 2.3 fold at two respective BPA concentrations. This demonstrated that BPA upregulated ZDHHC1 expression in human CD4+T cells. Again, we did qPCR analysis of ZDHHC1 gene expression and achieved similar results (Figure 5B), demonstrating that BPA and E2 both transcriptionally upregulated ZDHHC1 expression both in vitro using human epithelial-like and CD4+ T cells as well as in vivo from CD4+T cells of mice.

Figure 5. ZDHHC1 expression in human CCL119 CD4+T-enriched cells.

A. Fold changes of ZDHHC1 protein expression relative to the controls (Ctl) of vehicle-treated cells. Left: A representative Western-blot picture; Right the calculation based on three replicates.

B. Fold changes of ZDHHC1 gene expression measured by qPCR relative to Ctl. Significance *: p < 0.05; **: p<0.01

Discussion

We analyzed the proteome of CD4+T cells in mice that were exposed to BPA and identified a transgenerational effect on the immune system as determined by enriched immune-related pathways and proteins such as Rac1 and CDC42. Although the initial F0 mice were directly exposed to BPA, and their F1 pups were exposed in utero, F2 and F3 pups had no BPA treatment whatsoever. Surprisingly, we find that chromatin modifying enzymes and innate viral immune response proteins are upregulated in the F2 and F3 mice. We identified an upregulated protein ZDHHC1, a probable protein palmitoyltransferase, that is involved in the activation of innate viral immune response to DNA viruses. We confirmed increased expression of ZDHHC1 both in vitro and in vivo using qPCR, western blot, and mass spectrometry.

Using immunoprecipitation, we further validated ZDHHC1 was both upregulated and bound to STING, likely indicating that the STING pathway is activated by BPA exposure. This is consistent with other studies showing that BPA can cause a Type 1 Interferon response which is activated downstream of the STING pathway32. These authors also demonstrated E2, through ERα, also resulted in a Type 1 interferon response. Type 1 Interferon responses are implicated generally in autoimmune diseases, as they upregulate a number of factors, including IFNα and IFNβ, that can stimulate inflammation and cell death. Consistent with ERα being important in the activation of an innate viral immune response, E2 also increased ZDHHC1 expression. However, VD3 to some degree also increased ZDHHC1 (Figure 5B). While VD3 treatment alone had only a modest effect on Caco-2 cells, together with BPA seemed to have an additive effect (Figure 2). Together this suggests that previous conflicting reports that VD3 may have either pro or anti-inflammatory effects may strongly depend on additional factors such as sex and other endocrine related factors although it is unclear how VD3 contributes to ZDHHC1 expression33. We speculate VD3 can alter endogenous estrogen metabolism (Figure S9); it can also be explained by co-activation of estrogen and VD3 since ZDHHCA has both ERα and VDR binding elements in the upstream of its promoter (Supplemental Information S_003).

Studies of diethylstilbestrol (DES) and Estradiol (E2) have been shown to induce a cascade of intracellular phosphorylation signaling through a membrane form of alpha subunit of the estrogen receptor (ERα). This results in downstream phosphorylation of EZH2, inactivating it, which leads to a subsequent reduction of the histone epigenetic marker, H3K27 trimethylation 34. Indeed, we found BPA treated Caco-2 cells had reduced H3K27 trimethylation (Fig 3C). This suggests BPA, like other, estrogen receptor ligands can mediate downstream epigenetic modifications. In support of this BRD4, a histone acetyltransferase that is also involved in the innate RNA viral immune response, was upregulated in Caco-2 cells28 (Figure 2A & 2B). BRD4 is believed to regulate ERα-induced gene expression by acting as an enhancer35. This suggests there is a link between ERα activation, innate immune responses, and their coupling to chromatin modifications. Along with BRD4, MYST3 another histone acetyltransferase was upregulated by BPA (Figure 4B & 4C). In line with this, we find increased histone H3 acetylation and decreased H3K27 trimethylation which would be associated with euchromatin and increased transcription (Figure 4C & S9).

Continual BPA exposure could constitutively activate both ZDHHC1/STING and BRD4 related innate immune responses. While this might explain BPA directly activating these pathways, it is unclear how BPA induces transgenerational activation of similar or related immune signaling in subsequent generations. Although we do not fully understand the mechanism by which this would be passed down from generation to generation even after BPA is no longer present, it suggests the epigenetic reprogramming measured herein is heritable and primes the immune response of subsequent generations. Perhaps this may explain the transgenerational effects of BPA induced allergic asthma as the initial responses from direct exposure become “hard coded” into the epigenetic code which is then passed onto subsequent generations. This causes them to elicit an undesired hyperactive immune response even in the absence of a stimulant.

In summary, our current proteomic studies identified ZDHHC1 as a potentially key BPA-upregulated protein that is known to be involved in activating innate viral immune pathways and a Type 1 Interferon response. Furthermore the upregulation of BRD4 in vitro and ZDHHC1 upregulation by qPCR and western blot in response to E2 all point to ERα mediated signaling that leads to the global changes in H3 acetylation and H3K27 trimethylation. Lastly, we demonstrate that immune activation is apparent to at least the F2 mice who had no BPA exposure and even F3 mice had upregulated chromatin modifying pathways. Altogether this suggests BPA via activating ERα and an innate viral immune response can propagate this cellular response over several generations by altering the heritable epigenetic phenotype. Moreover, the current proteomic findings reveal further necessary biological studies on the mechanism of epigenetic inheritance and its relationship to multigenerational allergic asthma.

Supplementary Material

Protein list reprocessed by Perseus from of LFQ (Analyzed by PEAKS) of CD4+T cells from F0, F1-F3 mice

Upregulated reactome pathways from STRING analysis of F0, F1-F3 mice

Protein list of LFQ of CD4+T cells from F0 mice

Upstream activators of BPA predicted from IPA for F0-mice

KEGG enrichment pathways perturbed by BPA in CD4+T cells of F0-mice

Protein list of LFQ of CD4+T cells from F1-mice

Protein list of LFQ of CD4+T cells from F2-mice

Protein list of LFQ of CD4+T cells from F3-mice

Upstream activators of BPA predicted from IPA for F2-mice

Upstream activators of BPA predicted from IPA for F3-mice

Upstream activators of BPA predicted from IPA for F1-mice

KEGG enrichment pathways perturbed by BPA in CD4+T cells of F1-mice

KEGG enrichment pathways perturbed by BPA in CD4+T cells of F2-mice

KEGG enrichment pathways perturbed by BPA in CD4+T cells of F3-mice

List of proteins with significant expression changes reprocessed by Perseus

Upregulated Reactome pathways from STRING analysis of Caco-2 cells treated with BPA and VD3

Figure S1. Experimental design for proteomics

Figure S2. The purities of mouse splenic CD4+T cells involved in this study

Figure S3. Prediction of upstream activities

Figure S4. KEGG pathways revealed by STRING analysis of the proteins with significant changes of expression in F0 mice

Figure S5. Canonical pathways revealed by IPA of the proteins with significant changes of expression in F0 mice

Figure S6. KEGG pathways revealed by STRING analysis of the proteins with significant changes of expression in F1-F3 mice

Figure S7. Canonical pathways revealed by IPA of the proteins with significant changes of expression in F1-F3 mice

Figure S8. Protein expression of 17β-HSD1, 17β-HSD2, DNMT1, DNMT3A, and EED regulated by BPA, VD3, and BPA+VD3 in caco-2 cells

Figure S9. Global histone H3K27 methylation in BPA (100 nM) or VD3 (100 nM) treated Caco2 cells analyzed by PRM

Figure S10. Original Western blot picture and band intensities of ZDHHC1 expression in human CCL119 CD4+T-enriched cells

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Environmental Science (Midoro-Horiuti, R21 ES025406).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information:

The following supporting information is available free of charge at ACS website http://pubs.acs.org:

SI_003: Promoter of hZDHHC1_ERE_VD3

References

- 1.(a) Annamalai J; Namasivayam V, Endocrine disrupting chemicals in the atmosphere: Their effects on humans and wildlife. Environment international 2015, 76, 78–97; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Degen GH; Bolt HM, Endocrine disruptors: update on xenoestrogens. International archives of occupational and environmental health 2000, 73 (7), 433–41; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Vinas R; Jeng YJ; Watson CS, Non-genomic effects of xenoestrogen mixtures. International journal of environmental research and public health 2012, 9 (8), 2694–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le HH; Carlson EM; Chua JP; Belcher SM, Bisphenol A is released from polycarbonate drinking bottles and mimics the neurotoxic actions of estrogen in developing cerebellar neurons. Toxicology letters 2008, 176 (2), 149–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Rubin BS, Bisphenol A: an endocrine disruptor with widespread exposure and multiple effects. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 2011, 127 (1-2), 27–34; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schug TT; Janesick A; Blumberg B; Heindel JJ, Endocrine disrupting chemicals and disease susceptibility. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 2011, 127 (3-5), 204–15; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Takeuchi T; Tsutsumi O; Ikezuki Y; Takai Y; Taketani Y, Positive relationship between androgen and the endocrine disruptor, bisphenol A, in normal women and women with ovarian dysfunction. Endocrine journal 2004, 51 (2), 165–9; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wetherill YB; Akingbemi BT; Kanno J; McLachlan JA; Nadal A; Sonnenschein C; Watson CS; Zoeller RT; Belcher SM, In vitro molecular mechanisms of bisphenol A action. Reproductive toxicology 2007, 24 (2), 178–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Comhair SA; Erzurum SC, Redox control of asthma: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2010, 12 (1), 93–124; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Donohue KM; Miller RL; Perzanowski MS; Just AC; Hoepner LA; Arunajadai S; Canfield S; Resnick D; Calafat AM; Perera FP; Whyatt RM, Prenatal and postnatal bisphenol A exposure and asthma development among inner-city children. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2013, 131 (3), 736–42; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gascon M; Casas M; Morales E; Valvi D; Ballesteros-Gomez A; Luque N; Rubio S; Monfort N; Ventura R; Martinez D; Sunyer J; Vrijheid M, Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A and phthalates and childhood respiratory tract infections and allergy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2015, 135 (2), 370–8; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Humbert M; Corrigan CJ; Kimmitt P; Till SJ; Kay AB; Durham SR, Relationship between IL-4 and IL-5 mRNA expression and disease severity in atopic asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 1997, 156 (3 Pt 1), 704–8; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Robinson DS; Bentley AM; Hartnell A; Kay AB; Durham SR, Activated memory T helper cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with atopic asthma: relation to asthma symptoms, lung function, and bronchial responsiveness. Thorax 1993, 48 (1), 26–32; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Spanier AJ; Kahn RS; Kunselman AR; Schaefer EW; Hornung R; Xu Y; Calafat AM; Lanphear BP, Bisphenol a exposure and the development of wheeze and lung function in children through age 5 years. JAMA pediatrics 2014, 168 (12), 1131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koike E; Yanagisawa R; Win-Shwe TT; Takano H, Exposure to low-dose bisphenol A during the juvenile period of development disrupts the immune system and aggravates allergic airway inflammation in mice. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology 2018, 32, 2058738418774897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gern JE; Lemanske R. Fv Jr.; Busse WW, Early life origins of asthma. The Journal of clinical investigation 1999, 104 (7), 837–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Midoro-Horiuti T; Tiwari R; Watson CS; Goldblum RM, Maternal bisphenol a exposure promotes the development of experimental asthma in mouse pups. Environmental health perspectives 2010, 118 (2), 273–7; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nakajima Y; Goldblum RM; Midoro-Horiuti T, Fetal exposure to bisphenol A as a risk factor for the development of childhood asthma: an animal model study. Environmental health : a global access science source 2012, 11, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skinner MK; Manikkam M; Guerrero-Bosagna C, Epigenetic transgenerational actions of endocrine disruptors. Reproductive toxicology 2011, 31 (3), 337–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vollmer WM; Osborne ML; Buist AS, 20-year trends in the prevalence of asthma and chronic airflow obstruction in an HMO. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 1998, 157 (4 Pt 1), 1079–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Caserta D; Di Segni N; Mallozzi M; Giovanale V; Mantovani A; Marci R; Moscarini M, Bisphenol A and the female reproductive tract: an overview of recent laboratory evidence and epidemiological studies. Reproductive biology and endocrinology : RB&E 2014, 12, 37; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hunt PA; Lawson C; Gieske M; Murdoch B; Smith H; Marre A; Hassold T; VandeVoort CA, Bisphenol A alters early oogenesis and follicle formation in the fetal ovary of the rhesus monkey. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012, 109 (43), 17525–30; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Newbold RR; Jefferson WN; Padilla-Banks E, Long-term adverse effects of neonatal exposure to bisphenol A on the murine female reproductive tract. Reproductive toxicology 2007, 24 (2), 253–8; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Soto AM; Vandenberg LN; Maffini MV; Sonnenschein C, Does breast cancer start in the womb? Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology 2008, 102 (2), 125–33; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Susiarjo M; Hassold TJ; Freeman E; Hunt PA, Bisphenol A exposure in utero disrupts early oogenesis in the mouse. PLoS genetics 2007, 3 (1), e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Brieno-Enriquez MA; Reig-Viader R; Cabero L; Toran N; Martinez F; Roig I; Garcia Caldes M, Gene expression is altered after bisphenol A exposure in human fetal oocytes in vitro. Molecular human reproduction 2012, 18 (4), 171–83; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Skinner MK, Environmental epigenetic transgenerational inheritance and somatic epigenetic mitotic stability. Epigenetics 2011, 6 (7), 838–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veurink M; Koster M; Berg LT, The history of DES, lessons to be learned. Pharmacy world & science : PWS 2005, 27 (3), 139–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newbold RR; Hanson RB; Jefferson WN; Bullock BC; Haseman J; McLachlan JA, Proliferative lesions and reproductive tract tumors in male descendants of mice exposed developmentally to diethylstilbestrol. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21 (7), 1355–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karmakar PC; Kang HG; Kim YH; Jung SE; Rahman MS; Lee HS; Kim YH; Pang MG; Ryu BY, Bisphenol A Affects on the Functional Properties and Proteome of Testicular Germ Cells and Spermatogonial Stem Cells in vitro Culture Model. Scientific reports 2017, 7 (1), 11858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Betancourt A; Mobley JA; Wang J; Jenkins S; Chen D; Kojima K; Russo J; Lamartiniere CA, Alterations in the rat serum proteome induced by prepubertal exposure to bisphenol a and genistein. Journal of proteome research 2014, 13 (3), 1502–14; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vahdati Hassani F; Abnous K; Mehri S; Jafarian A; Birner-Gruenberger R; Yazdian Robati R; Hosseinzadeh H, Proteomics and phosphoproteomics analysis of liver in male rats exposed to bisphenol A: Mechanism of hepatotoxicity and biomarker discovery. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association 2018, 112, 26–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HS; Kang Y; Tae K; Bae GU; Park JY; Cho YH; Yang M, Proteomic Biomarkers for Bisphenol A-Early Exposure and Women's Thyroid Cancer. Cancer research and treatment : official journal of Korean Cancer Association 2018, 50 (1), 111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Zhou Q; Lin H; Wang S; Wang S; Ran Y; Liu Y; Ye W; Xiong X; Zhong B; Shu HB; Wang YY, The ER-associated protein ZDHHC1 is a positive regulator of DNA virus-triggered, MITA/STING-dependent innate immune signaling. Cell host & microbe 2014, 16 (4), 450–61; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu X; Li M; Wu Z; Wang H; Wang L; Huang K; Liu X; Hou Q; Lin G; Hu C, Endoplasmic Reticulum Transmembrane Proteins ZDHHC1 and STING Both Act as Direct Adaptors for IRF3 Activation in Teleost. Journal of immunology 2017, 199 (10), 3623–3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curran EM; Judy BM; Newton LG; Lubahn DB; Rottinghaus GE; Macdonald RS; Franklin C; Estes DM, Dietary soy phytoestrogens and ERalpha signalling modulate interferon gamma production in response to bacterial infection. Clinical and experimental immunology 2004, 135 (2), 219–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabuto H; Amakawa M; Shishibori T, Exposure to bisphenol A during embryonic/fetal life and infancy increases oxidative injury and causes underdevelopment of the brain and testis in mice. Life sciences 2004, 74 (24), 2931–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang K; Xu P; Sowers JL; Machuca DF; Mirfattah B; Herring J; Tang H; Chen Y; Tian B; Brasier AR; Sowers LC, Proteome Analysis of Hypoxic Glioblastoma Cells Reveals Sequential Metabolic Adaptation of One-Carbon Metabolic Pathways. Molecular & cellular proteomlcs : MCP 2017, 16(11), 1906–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vizcaino JA; Csordas A; Del-Toro N; Dianes JA; Griss J; Lavidas I; Mayer G; Perez-Riverol Y; Reisinger F; Ternent T; Xu QW; Wang R; Hermjakob H, 2016 update of the PRIDE database and its related tools. Nucleic acids research 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tyanova S; Temu T; Sinitcyn P; Carlson A; Hein MY; Geiger T; Mann M; Cox J, The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat Methods 2016, 13 (9), 731–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stahlhut RW; Welshons WV; Swan SH, Bisphenol A data in NHANES suggest longer than expected half-life, substantial nonfood exposure, or both. Environmental health perspectives 2009, 117 (5), 784–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Bonds RS; Midoro-Horiuti T, Estrogen effects in allergy and asthma. Current opinion In allergy and clinical immunology 2013, 13 (1), 92–9; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nishizawa H; Imanishi S; Manabe N, Effects of exposure in utero to bisphenol a on the expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor, related factors, and xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes in murine embryos. The Journal of reproduction and development 2005, 51 (5), 593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnes PJ, Th2 cytokines and asthma: an introduction. Respiratory research 2001, 2 (2), 64–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Keselman A; Heller N, Estrogen Signaling Modulates Allergic Inflammation and Contributes to Sex Differences in Asthma. Frontiers in immunology 2015, 6, 568; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chevigny M; Guerin-Montpetit K; Vargas A; Lefebvre-Lavoie J; Lavoie JP, Contribution of SRF, Elk-1, and myocardin to airway smooth muscle remodeling in heaves, an asthma-like disease of horses. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2015, 309 (1), L37–45; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Singh S; Prakash YS; Linneberg A; Agrawal A, Insulin and the lung: connecting asthma and metabolic syndrome. Journal of allergy 2013, 2013, 627384; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Greenfeder S; Umland SP; Cuss FM; Chapman RW; Egan RW, Th2 cytokines and asthma. The role of interleukin-5 in allergic eosinophilic disease. Respiratory research 2001, 2 (2), 71–9; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Guedes AG; Deshpande DA; Dileepan M; Walseth TF; Panettieri RA Jr.; Subramanian S; Kannan MS, CD38 and airway hyper-responsiveness: studies on human airway smooth muscle cells and mouse models. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology 2015, 93 (2), 145–53; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Deshpande DA; Guedes AGP; Lund FE; Subramanian S; Walseth TF; Kannan MS, CD38 in the pathogenesis of allergic airway disease: Potential therapeutic targets. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2017, 172, 116–126; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Volckaert T; Campbell A; De Langhe S, c-Myc regulates proliferation and Fgf10 expression in airway smooth muscle after airway epithelial injury in mouse. PloS one 2013, 8 (8), e71426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vandenberg LN; Chahoud I; Heindel JJ; Padmanabhan V; Paumgartten FJ; Schoenfelder G, Urinary, circulating, and tissue biomonitoring studies indicate widespread exposure to bisphenol A. Environmental health perspectives 2010, 118 (8), 1055–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian B; Yang J; Zhao Y; Ivanciuc T; Sun H; Garofalo RP; Brasier AR, BRD4 Couples NF-kappaB/RelA with Airway Inflammation and the IRF-RIG-I Amplification Loop in Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. J Virol 2017, 91 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu JY; Feng L; Park HT; Havlioglu N; Wen L; Tang H; Bacon KB; Jiang Z; Zhang X; Rao Y, The neuronal repellent Slit inhibits leukocyte chemotaxis induced by chemotactic factors. Nature 2001, 410 (6831), 948–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Sowers JL; Mirfattah B; Xu P; Tang H; Park IY; Walker C; Wu P; Laezza F; Sowers LC; Zhang K, Quantification of histone modifications by parallel-reaction monitoring: a method validation. Anal Chem 2015, 87 (19), 10006–14; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tang H; Fang H; Yin E; Brasier AR; Sowers LC; Zhang K, Multiplexed parallel reaction monitoring targeting histone modifications on the QExactive mass spectrometer. Anal Chem 2014, 86 (11), 5526–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miettinen MM; Mustonen MV; Poutanen MH; Isomaa VV; Vihko RK, Human 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and type 2 isoenzymes have opposite activities in cultured cells and characteristic cell- and tissue-specific expression. The Biochemical journal 1996, 314 ( Pt3), 839–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panchanathan R; Liu H; Leung YK; Ho SM; Choubey D, Bisphenol A (BPA) stimulates the interferon signaling and activates the inflammasome activity in myeloid cells. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 2015, 415, 45–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali NS; Nanji K, A Review on the Role of Vitamin D in Asthma. Cureus 2017, 9 (5), e1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Bredfeldt TG; Greathouse KL; Safe SH; Hung MC; Bedford MT; Walker CL, Xenoestrogen-induced regulation of EZH2 and histone methylation via estrogen receptor signaling to PI3K/AKT. Molecular endocrinology 2010, 24 (5), 993–1006; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Greathouse KL; Bredfeldt T; Everitt JI; Lin K; Berry T; Kannan K; Mittelstadt ML; Ho SM; Walker CL, Environmental estrogens differentially engage the histone methyltransferase EZH2 to increase risk of uterine tumorigenesis. Molecular cancer research : MCR 2012, 10 (4), 546–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagarajan S; Hossan T; Alawi M; Najafova Z; Indenbirken D; Bedi U; Taipaleenmaki H; Ben-Batalla I; Scheller M; Loges S; Knapp S; Hesse E; Chiang CM; Grundhoff A; Johnsen SA, Bromodomain protein BRD4 is required for estrogen receptor-dependent enhancer activation and gene transcription. Cell reports 2014, 8 (2), 460–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Protein list reprocessed by Perseus from of LFQ (Analyzed by PEAKS) of CD4+T cells from F0, F1-F3 mice

Upregulated reactome pathways from STRING analysis of F0, F1-F3 mice

Protein list of LFQ of CD4+T cells from F0 mice

Upstream activators of BPA predicted from IPA for F0-mice

KEGG enrichment pathways perturbed by BPA in CD4+T cells of F0-mice

Protein list of LFQ of CD4+T cells from F1-mice

Protein list of LFQ of CD4+T cells from F2-mice

Protein list of LFQ of CD4+T cells from F3-mice

Upstream activators of BPA predicted from IPA for F2-mice

Upstream activators of BPA predicted from IPA for F3-mice

Upstream activators of BPA predicted from IPA for F1-mice

KEGG enrichment pathways perturbed by BPA in CD4+T cells of F1-mice

KEGG enrichment pathways perturbed by BPA in CD4+T cells of F2-mice

KEGG enrichment pathways perturbed by BPA in CD4+T cells of F3-mice

List of proteins with significant expression changes reprocessed by Perseus

Upregulated Reactome pathways from STRING analysis of Caco-2 cells treated with BPA and VD3

Figure S1. Experimental design for proteomics

Figure S2. The purities of mouse splenic CD4+T cells involved in this study

Figure S3. Prediction of upstream activities

Figure S4. KEGG pathways revealed by STRING analysis of the proteins with significant changes of expression in F0 mice

Figure S5. Canonical pathways revealed by IPA of the proteins with significant changes of expression in F0 mice

Figure S6. KEGG pathways revealed by STRING analysis of the proteins with significant changes of expression in F1-F3 mice

Figure S7. Canonical pathways revealed by IPA of the proteins with significant changes of expression in F1-F3 mice

Figure S8. Protein expression of 17β-HSD1, 17β-HSD2, DNMT1, DNMT3A, and EED regulated by BPA, VD3, and BPA+VD3 in caco-2 cells

Figure S9. Global histone H3K27 methylation in BPA (100 nM) or VD3 (100 nM) treated Caco2 cells analyzed by PRM

Figure S10. Original Western blot picture and band intensities of ZDHHC1 expression in human CCL119 CD4+T-enriched cells