Abstract

Chromium (Cr) (VI) is a toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic water pollutant. The standard ion chromatography (IC) method for quantification of Cr (VI) in water samples is Environmental Protection Agency Method 218.7, which requires postcolumn derivatization with 1,5-diphenylcarbazide and UV-Vis spectroscopy detection. Method 218.7 is Cr (VI) specific; thus, it does not allow detection of co-occurring natural and anthropogenic anions in environmental media. In this study, we developed an isocratic IC method with suppressed conductivity detection, a Metrohm Metrosep A Supp 7 column, and sodium carbonate/acetonitrile as mobile phase for simultaneous quantification of Cr (VI), , As (V) as arsenate, Se (VI) as selenate, and the common anions F–, Cl–, , , and . The determination coefficient for every analyte was >0.99 and the method showed good accuracy in quantification. Cr (VI), As (V), Se (VI), and limit of detection and limit of quantification were 0.1–0.6 μg/L and 0.5–2.1 μg/L, respectively. Recovery of Cr (VI) in various aqueous samples (tap water, surface water, groundwater, and wastewater) was between 97.2% and 102.8%. Overall, most analytes showed acceptable recovery (80–120%) in the environmental samples tested. The IC method was applied to track Cr (VI) and other anion concentrations in laboratory batch microcosms experiments with soil, surface water, and anaerobic medium. The IC method developed in this study should prove useful to environmental practitioners, academic and research organizations, and industries for monitoring low concentrations of multiple anions in environmental media, helping to decrease the sample requirement, time, and cost of analysis.

Keywords: arsenate, chromate, Cr (VI), ion chromatography, perchlorate, selenate, suppressed conductivity

Introduction

Chromium (Cr) (VI) is a toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic water pollutant (Cohen et al., 1993; Costa, 1997; Salnikow and Zhitkovich, 2008). The World Health Organization (WHO) set a maximum allowable limit of 50 μg/L for Cr (VI) in groundwater and drinking water (WHO, 2003; El-Shahawi et al., 2011). In the United States, the drinking water maximum contaminant level (MCL) set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is 100 μg/L total Cr (US EPA, 2010). At the state level, the MCL can be even lower (e.g., 50 μg/L as total Cr in California) (California State Water Quality Control Board, 2020). The standard ion chromatography (IC) method for quantification of chromate ion (CrO42−), the most common Cr (VI) anion, in water samples is EPA Method 218.7 (Zaffiro et al., 2011). Method 218.7 involves the separation of CrO42− (referred henceforth as Cr [VI]) using a high-capacity anion exchange separator column, a postcolumn derivatization with Cr (VI)-specific reagent 1,5-diphenylcarbazide, and a UV-Vis detection of the colored complex at 530 nm (Zaffiro et al., 2011). The Cr (VI)-specific reagent diphenylcarbazide and UV-Vis detection allow sensitive quantification of Cr (VI) at low microgram per liter concentrations by avoiding interference from other anions like sulfate ion (). However, method 218.7 and methods using similar principles are Cr (VI) specific and do not quantify other analytes present in a given samples (Metrohm USA; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Rakhunde et al., 2012; Onchoke and Sasu, 2016).

Cr (VI) often co-occurs with one or more common inorganic anions such as chloride ion (Cl–), , and nitrate ion () in drinking water, industrial wastewater, surface waters, groundwater, acid mine drainage, soils, and sediments (Riley, 1992; Gandhi et al., 2002). In groundwater, acid mine drainage and other process waters, Cr (VI) is often a co-contaminant with other regulated anions such as arsenate ion () and selenate ion () (referred henceforth as As (V) and Se (VI), respectively) or perchlorate ion () (Pyrzyńska, 2002; Urbansky, 2002; Parker et al., 2008; Yoon et al., 2009; Zhitkovich, 2011; Wang et al., 2013; Steinmaus, 2016; Khamkhash et al., 2017; WHO, 2018). and Cr (VI) are frequently co-detected in drinking water systems across the world (Zhitkovich, 2011; Steinmaus, 2016). Most laboratories use IC with conductivity detection to simultaneously quantify Cl–, and using EPA Method 9056A (US EPA, 2007; Weiss, 2016). Separate IC methods with conductivity detection have been reported for quantification of (EPA Method 314.0) (Hautman et al., 1999), As (V) (Lee and Choi, 2002; Ike et al., 2008; Yeo and Choi, 2009; Bhandari et al., 2011), and (Se [VI]) (Karlson and Frankenberger Jr, 1986; Mehra and Frankenberger, 1988; Pyrzyńska, 2002). Thus, analysis of surface water, groundwater, acid mine drainage, and other environmental aqueous samples containing Cr (VI) and co-occurring anions requires multiple IC analytical methods with different anion exchange columns and eluent compositions. This requirement not only increases the sample volume demand but also the time and overall cost of analysis.

A limited numbers of studies achieved separation and detection of Cr (VI), As (V), and Se (VI) in the presence of common inorganic anions using anion exchange columns and conductivity detection (Bruzzoniti et al., 1999; Kończyk et al., 2018). However, linearity, precision, and accuracy of the co-detected analytes were not reported in these studies (Bruzzoniti et al., 1999; Kończyk et al., 2018), limiting the methods' applicability to environmental samples commonly analyzed in academic or other research-focused laboratories. In this work, we developed an isocratic IC analytical method with suppressed conductivity detection for simultaneous quantification of Cr (VI) and eight other environmentally relevant anions: fluoride ion (F–), Cl–, nitrite ion (), , , Se (VI), As (V), and . The method was validated by determining the linearity and accuracy (precision and trueness) for all the anion analytes. We used the method to evaluate recovery of Cr (VI) and the other analytes in tap water, surface water, groundwater, and industrial wastewater samples and to analyze Cr (VI), , and Cl– in laboratory microcosm experiments.

Materials and Methods

Instrumentation

All analyses were performed using a Metrohm AG 930 compact IC flex system (Herisau, Switzerland). The IC was equipped with a chemical suppressor (Metrohm suppressor module [MSM]) and a conductivity detector. An 800 dosino regeneration system was used to deliver the chemical suppressor solution to the MSM. The Metrohm CO2 Suppressor removed the carbonate (as CO2) produced during the chemical suppression reaction in the MSM. The anions were separated using a Metrosep A Supp 7 analytical column (250 × 4 mm; Metrohm) and a Metrosep A Supp 5 Guard column (5 × 4 mm; Metrohm). A Metrohm AG 919 IC autosampler plus was used for sample injection. The volume of the sample injection loop was 1000 μL. The data acquisition and processing were performed with the MagIC Net 3.2 Metrodata software.

Chemicals and reagents

Reagent water, LC-MS Ultra CHROMASOLV (Honeywell, Charlotte, NC), was used to prepare the standards and for the sample dilutions. Cr (VI) standards were prepared using K2CrO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). As (V) and Se (VI) standards were prepared using Na2HAsO4 • 7H2O (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ) and Na2SeO4 (ACROS Organics, Geel, Belgium). standards (Metrohm; cat. no. REAIC1023) and mixed anion standard (Metrohm; cat. no. REAIC1035) were used to generate the calibration curves for , F–, Cl–, , , and .

The eluent and the MSM suppressor solutions were prepared using deionized and purified water using a PURELAB Ultra (ELGA LabWater, United Kingdom) with a specific resistance ≥18.2 MΏ-cm. The eluent (mobile phase) contained 10.8 mM Na2CO3 (3% [v/v] of Metrohm's A Supp 7 eluent 100 × concentrate) and 35% (v/v) gradient grade acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich) in deionized water. The pH of the eluent as prepared was 11.9 ± 0.02. The MSM suppressor solution contained 500 mM H2SO4 in deionized water.

The 10% (v/v) H2SO4 and 10% (v/v) H3PO4 solutions for colorimetric determination of Cr (VI) were prepared from concentrated H2SO4 (95–98% solution; VWR, Randor, PA) and concentrated H3PO4 (85% solution; Alfa Aesar, Haverhill, MA), respectively. The complexing reagent contained 5 g/L of 1,5-diphenylcarbazide (Sigma-Aldrich) in acetone.

Analytical methods

The IC method used a constant eluent flow rate of 0.8 mL/min and a constant column/oven temperature of 55°C. The MSM stepping interval was 10 min and the conductivity detector was set at 2.3% per °C. At these conditions, the back pressure was 12 ± 0.4 MPa. The pump start-up time was at 45–60 min during the equilibration of the instrument. Calibrations for the anion analytes were established by injecting quadruplicates of 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 μg/L standard mixture. The upper limit of quantification (LOQ) for Cl–, , , , and Cr (VI) was 10,000 μg/L (10 mg/L). For other analytes, the upper LOQ was in the range of 1000–9000 μg/L.

EPA Method 7196A was used to quantify Cr (VI) in a contaminated surface water sample and compare the concentrations obtained by the IC method. Cr (VI) concentration was determined colorimetrically at 540 nm using the diphenylcarbazide method (US EPA, 1992). In brief, 0.1 mL of sample or standard was added to a 10 mL test tube followed by addition of 1 mL each of 10% H2SO4 and 10% H3PO4. Then, 0.1 mL of 5 g/L diphenylcarbazide in acetone was added to the test tube. The mixture was then vortexed and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Absorbance of the magenta color was analyzed using a Varian Cary 50 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent, Santa Clare, CA) at 540 nm. The spectrophotometer was calibrated using the standard Cr (VI) solution. The calibration range for the colorimetry method was 0.5–75 mg/L Cr (VI) and the detection limit was 0.25 mg/L.

Resolution, limit of detection, LOQ, and accuracy

Resolution of two peaks (R), defined as the ratio of the difference in retention times between two peaks and the average baseline width of two peaks (Harris, 2010), was determined using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where TR1 and TR2 are the retention times of adjacent peaks (analyte 1 elutes before analyte 2) and wb1 and wb2 are the widths of the peaks at baseline.

The limit of detection (LOD), defined as the lowest concentration of analyte in a sample that can be readily distinguished from the absence of that analyte (a blank value) (McNaught and Wilkinson, 1997; Inczedy et al., 1998; Allegrini and Olivieri, 2014), was determined using Eq. (2):

| (2) |

The LOQ, defined as the smallest concentration of analyte in a sample that can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy, was determined using Eq. (3):

| (3) |

In Eqs. (2) and (3), Sa is the standard deviation of the response estimated by the standard error of y-intercepts of the regression lines and b is the slope of the calibration curve (Shrivastava and Gupta, 2011). A calibration curve with concentrations between 0.3 and 25 μg/L was used to obtain LOD and LOQ of all analytes.

Accuracy, defined as the closeness between a measured value and either a true or accepted value, was evaluated from precision and trueness values of each analyte (Munch et al., 2005). The precision was determined by calculating the relative standard deviation (RSD) using Eq. (4). Trueness was determined by calculating the recovery using Eq. (5).

| (4) |

| (5) |

Environmental samples

Tap water from the city of Tempe and reverse osmosis grade water (US Water Systems, Indianapolis, IN) were collected at the Biodesign Institute, Arizona State University (Tempe, AZ). Tap water from the City of Mesa was collected from a domicile in Mesa, AZ. Three groundwater samples were obtained for testing. One groundwater sample was from Phoenix Goodyear Airport-North Superfund site (AZ) (Rangan et al., 2020). The other samples were collected from two confidential sites in the Southwestern United States. Cr (VI) contaminated surface water was collected from Tamil Nadu Chromates and Chemicals Ltd. (TCCL), an abandoned chromate manufacturing facility in Ranipet, Tamil Nadu, India. The wastewater samples used in this study were received from a power station in the Eastern United States and from the Northwest Water Reclamation Plant (Mesa, AZ).

Laboratory microcosm experiments

The developed IC method was applied to monitor anions in soil and culture-only batch microcosms. Soil laboratory microcosms (Ziv-El et al., 2011; Rangan et al., 2020; Joshi et al., 2021) focused on abiotic and microbiological Cr (VI) reduction were established in 160 mL glass serum bottles with 25 g of Cr (VI)-contaminated soil and 100 mL anaerobic mineral medium as described elsewhere (Delgado et al., 2012, 2017). The soil was collected from 0 to 0.25 m depth at the TCCL site, India, and was homogenized in the anaerobic glove chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc., Grass Lake, MI) under 3.5% H2 and 96.5% N2 atmosphere. Two grams per liter yeast extract and 10 mM lactate (870 mg/L) were added to the microcosms as electrons and carbon sources for the microorganisms. The initial Cr (VI) concentration in the soil microcosms was ∼90 mg/L.

Culture-only microcosms (Delgado et al., 2014, 2016) focused on microbiological Cr (VI) reduction were established in 160 mL serum bottles containing 100 mL anaerobic mineral medium as used in soil microcosms. The inoculum (4% v/v) was a mixed culture grown on Cr (VI) and lactate. The culture-only microcosms were amended with 1 g/L yeast extract and 3 mM lactate (∼260 mg/L). The initial concentration of Cr (VI) was 15 mg/L. All (soil and culture-only) microcosms were established in triplicates, were incubated in the dark at 30°C, and were shaken on a platform shaker at 125 rpm. Liquid samples from the soil microcosms were collected for IC analysis during the experiment at 0.2, 3.7, and 8.2 h. Liquid samples from the culture-only microcosms were collected at 0, 2, 7, 10, 11, 14, and 17 days. The liquid samples were filtered using 0.2 μm syringe filters (mdi Membrane Technologies, Inc., Harrisburg, PA) and analyzed for anions by IC.

Results and Discussion

In this study, we report an isocratic IC method with suppressed conductivity detection for simultaneous quantification of Cr (VI), F–, Cl–, , , , Se (VI), As (V), and . A typical chromatogram of the analytes (50 μg/L each in DI water) is given in Fig. 1. Most analytes showed good separation (defined as R > 1.5 [Harris, 2010]). All analytes were eluted within 20 min of sample injection (Fig. 1). Table 1 compiles the resolution of the peaks, linear regression equation, determination coefficient, LOD, and LOQ for the analytes. The determination coefficient of every analyte was >0.99 and the LOD was in the range of 0.1–7.5 μg/L (Table 1). These data demonstrate the capability of the method to quantify trace concentrations of the analytes. For Cr (VI), the LOD and LOQ were 0.2 and 0.6 μg/L, respectively, which are three orders of magnitude lower than EPA's current MCL of 100 μg/L Cr.

FIG. 1.

IC chromatogram of a mixture of 50 μg/L each of Cr (VI), , and other anions spiked to DI water with a Metrohm Metrosep A Supp 7 analytical column and mobile phase containing 10.8 mM Na2CO3 eluent and 35% (v/v) acetonitrile. Cr, chromium; DI, deionized; IC, ion chromatography.

Table 1.

Resolution, Regression Equation, Determination Coefficient, Quantification Range, Limit of Quantification, and Limit of Detection of Nine Analytes Using the Method from This Study

| Elution order | Analyte | Resolution (R) | Regression equation | R2 | Quantification range (μg/L) | LOD (μg/L) | LOQ (μg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F– | 3.05 | Y = 0.0071X + 0.1517 | 0.9986 | 24.9–1000 | 7.5 | 24.9 |

| 2 | Cl– | 1.03 | Y = 0.0083X + 0.0541 | 0.9984 | 14.4–10,000 | 4.3 | 14.4 |

| 3 | 2.92 | Y = 0.002X + 0.0082 | 0.9979 | 1.5–5000 | 0.4 | 1.5 | |

| 4 | 5.51 | Y = 0.0122X + 0.0009 | 0.9981 | 1.9–10,000 | 0.6 | 1.9 | |

| 5 | 2.45 | Y = 0.0067X + 0.0903 | 0.9983 | 9.5–10,000 | 2.9 | 9.5 | |

| 6 | Se (VI) | 1.55 | Y = 0.0066X + 0.0024 | 0.9999 | 0.5–9000 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| 7 | As (V) | 2.51 | Y = 0.0023X − 0.009 | 0.9988 | 2.1–7000 | 0.6 | 2.1 |

| 8 | 3.71 | Y = 0.0025X − 0.0045 | 0.9992 | 0.5–10,000 | 0.1 | 0.5 | |

| 9 | Cr (VI) | NA | Y = 0.0041X + 0.0046 | 0.9998 | 0.6–10,000 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

R values >1.5 are baseline resolutions.

Cr, chromium; LOD, limit of detection; LOQ, limit of quantification; NA, not applicable (Cr [VI] was the last analyte in the method run; X, concentration (μg/L); Y, peak area ([μS/cm] × min).

A comparison of published IC methods for measurement of Cr (VI) in aqueous samples is given in Table 2. The contribution of our method over previously published IC methods for Cr (VI) quantification is that can also be quantified. We validated our method by demonstrating linearity, precision, and accuracy for simultaneous quantification of all the anion analytes, which was not reported previously by other IC methods (Bruzzoniti et al., 1999; Kończyk et al., 2018). The LOD and LOQ for Cr (VI) determined in this study was lowest among IC methods with suppressed conductivity detection (Table 2). We were able to achieve this low LOD and LOQ for Cr (VI) using a 1000 μL injection loop, which is used in the EPA Method for trace analysis of in drinking water (Hautman et al., 1999). Methods that use UV-Vis spectroscopy, chemiluminescence, and thermal lens spectroscopy detection systems can achieve lower LOD for Cr (VI) but cannot quantify other anions.

Table 2.

Comparison of Various Ion Chromatography Methods for Chromium (VI) Quantification in Aqueous Samples

| Detection system | Postcolumn derivatization | LOD (μg/L) | LOQ (μg/L) | Sample injection volume (μL) | Simultaneous detection of other anions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis spectroscopy | Yes | a0.01 | a0.036 | a1250 | No | U.S. EPA method 218.7 Zaffiro et al. (2011) |

| Chemiluminescence detection | Yes | 0.09 | NR | 50 | No | Gammelgaard et al. (1997) |

| Thermal lens spectrometry | Yes | 0.1 | NR | 200 | No | bŠikovec et al. (2001) |

| Direct UV detection | No | 0.2 | 1.2 | 100 | No | Michalski (2003) |

| Suppressed conductivity | No | 13.5 | 44.7 | 10 | Cyanide, thiocyanate, cyanate | (Destanoğlu and Gümüş Yılmaz (2016) |

| Suppressed conductivity | No | 2 | NR | 200 | Cl–, , , Se (IV), Se (VI), W (VI), As (V), Mo (VI) | bBruzzoniti et al. (1999) |

| Suppressed conductivity | No | NR | NR | 100 | F–, Cl–, Br–, , , | bKończyk et al. (2018) |

| Suppressed conductivity | No | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1000 | F–, Cl–, , , , Se (VI), As (V), | This study |

Values from carbonate/bicarbonate eluent system.

Linear regression equation, precision, and trueness were not reported.

EPA, Environmental Protection Agency; NR, not reported.

is among the most abundant anions in many environmental media (Miao et al., 2012). In our analytical method, As (V) and Se (VI) elute within 3 min after (Fig. 1). Thus, high concentrations could potentially interfere with quantification of As (V) and Se (VI) through this method. In such cases, samples would require dilution, making it challenging for trace analysis of the analytes using a conductivity detector. Alternatively, pretreatment of the sample matrix to remove can be employed using pretreatment cartridges, but these can severely affect the recovery of other analytes like Cr (VI) (Thermo Scientific, 2013). To elucidate interference, we evaluated the effect of concentration (up to 500 mg/L) on recovery of co-analytes. concentration had no effect on recovery of F–, Cl–, , and as these analytes eluted before in our method (Fig. 1). Se (VI) and As (V) recovery was <80% when concentration was >10 mg/L (data not shown). A recovery of 80% or greater is an acceptable criterion for quantification of chemical analytes (Hautman et al., 1999; US EPA, 2007). Hence, Se (VI) and As (V) cannot be quantified with accuracy in samples containing at concentrations >10 mg/L. Cr (VI) and recovery was ≥85% in the presence of up to 500 mg/L (Fig. 2). These data demonstrate that the method can be used to quantify low concentrations of Cr (VI) and in matrices with a high concentration of without requiring pretreatment or dilution of the sample.

FIG. 2.

Effect of concentration on recovery of Cr (VI) and .

We evaluated the analytical accuracy (precision and trueness) for quantification of the anions at three concentration levels (2, 10, and 100 μg/L) using the developed IC method. In reagent water or DI water, US EPA's acceptance criterion for RSD is ≤10%. The acceptance criterion for recovery is 80–120% for mid-level check standards (US EPA, 1996; Hautman et al., 1999). The acceptance criterion for recovery is 50–150% at concentrations close to the LOD of the analyte (low-level check standard) (US EPA, 1996). Table 3 documents the recovery of all anion analytes. At 100 μg/L, all analytes were quantified with RSD <2.3% and the recovery was in the range of 96.2–107.9%, showing precision and trueness (accuracy) for quantification (Table 3). At 10 μg/L, the RSD and recovery for F– and Cl– were substantially affected (RSD values >10% and recovery of 47.5–90.6% [Table 3]). These results are expected as 10 μg/L is within a factor of 3 from the LOD of F– and Cl– (US EPA, 1996). All other analytes were quantified with RSD <7.4% and recovery of 92.6–105.3% using 10 μg/L standard (Table 3). At 2 μg/L concentration, all analytes except were quantified with RSD <6% and recovery in the range of 95.8–106.4% (Table 3). Overall, the method accomplished accuracy in quantification of , Se (VI), As (V), , and Cr (VI) at concentrations as low as 2 μg/L. At 100 μg/L, the RSD and recovery for all analytes are well within the acceptance accuracy criteria (Hautman et al., 1999; Munch et al., 2005).

Table 3.

Analyte Accuracy of Quantification Using the Method From This Study

| Elution order | Analyte | Spiked concentration, 2 μg/L (n = 6) |

Spiked concentration, 10 μg/L (n = 6) |

Spiked concentration, 100 μg/L (n = 6) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision (RSD [%]) | Trueness (recovery [%]) | Precision (RSD [%]) | Trueness (recovery [%]) | Precision (RSD [%]) | Trueness (recovery [%]) | ||

| 1 | F– | NA | NA | 20.3 | 47.5 | 2.2 | 99.5 |

| 2 | Cl– | NA | NA | 12.2 | 90.6 | 0.9 | 96.2 |

| 3 | 0.0 | 95.8 | 2.4 | 97.2 | 1.3 | 97.6 | |

| 4 | 60.7 | 42.6 | 3.1 | 99.1 | 0.9 | 96.3 | |

| 5 | NA | NA | 7.3 | 92.6 | 1.5 | 101.0 | |

| 6 | Se (VI) | 3.2 | 106.4 | 1.3 | 100.8 | 0.8 | 102.2 |

| 7 | As (V) | 0.0 | 102.2 | 0.0 | 101.7 | 0.7 | 107.9 |

| 8 | 0.0 | 104.6 | 1.6 | 105.3 | 0.7 | 103.1 | |

| 9 | Cr (VI) | 5.2 | 98.3 | 1.7 | 100.1 | 0.7 | 98.7 |

NA, not applicable (concentration below limit of detection); RSD, relative standard deviation.

To test the applicability of the developed IC method on environmental aqueous samples, we evaluated the recovery of all analytes in deionized water, tap water, surface water, groundwater, and wastewater. The US EPA's acceptance criteria for recovery of analytes in environmental samples is 80–120% (Hautman et al., 1999). As given in Table 4, the recovery of Cr (VI) in all environmental samples tested was in the range of 97.2–102.8%. The recovery of the other analytes was within the acceptable recovery criterion in most environmental samples (Table 4). These data support the applicability of this method for simultaneous quantification of the analytes in environmental aqueous samples.

Table 4.

Recovery of All Anion Analytes in Environmental Samples

| Samples | Cr (VI) recovery (%) | F– recovery (%) | Cl– recovery (%) | recovery (%) | recovery (%) | recovery (%) | Se (VI) recovery (%) | As (V) recovery (%) | recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DI water | 100.9 ± 0.5 | 94.5 ± 1.2 | 93.5 ± 0.8 | 98.1 ± 1.3 | 96.5 ± 0.6 | 102.1 ± 1.5 | 104.3 ± 0.9 | 103.2 ± 0.7 | 103.3 ± 0.6 |

| RO water (Tempe, AZ) | 100.1 ± 0.3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Tap water (Tempe, AZ) | 102.1 ± 0.3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Tap water (Mesa, AZ) | 100.5 ± 0.6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Groundwater (Goodyear, AZ) | 97.6 ± 0.3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Groundwater (confidential site 1) | 100.2 ± 0.0 | 107.8 ± 7.0 | 101.5 ± 3.0 | 92.7 ± 2.3 | 109.2 ± 6.1 | 104.2 ± 2.8 | 94.3 ± 2.6 | 84.9 ± 4.9 | 95.9 ± 0.5 |

| Groundwater (confidential site 2) | 99.7 ± 0.6 | 82.6 ± 3.6 | 100.3 ± 2.5 | 85.0 ± 0.7 | 109.7 ± 1.9 | 111.8 ± 3.1 | 89.1 ± 0.2 | 71.0 ± 4.9 | 93.2 ± 0.4 |

| Surface water (Tamil Nadu, India) | 102.8 ± 0.6 | 86.1 ± 4.6 | 95.5 ± 0.4 | 92.5 ± 2.1 | 90.7 ± 2.7 | 89.5 ± 1.4 | 108.8 ± 0.2 | 98.7 ± 7.2 | 92.3 ± 0.6 |

| Wastewater (confidential site 3, Eastern United States) | 99.5 ± 0.3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Wastewater (Water Reclamation Plant, Mesa, AZ) | 97.2 ± 0.2 | 107.8 ± 3.7 | 108.8 ± 5.2 | 76.1 ± 2.4 | 103.7 ± 2.9 | 84.2 ± 0.3 | 97.0 ± 0.8 | 97.0 ± 0.5 | 101.2 ± 0.4 |

The data are averages with standard deviation of triplicates. The spiking concentration for all anions was 100 μg/L.

ND, not determined; RO, reverse osmosis.

We evaluated the trueness of Cr (VI) concentration in the surface water sample measured with our IC method by comparing it with the measured value using the EPA method 7196A (diphenylcarbazide-based colorimetry method). The concentration of Cr (VI) in the surface water was 20.6 ± 0.2 mg/L using the diphenylcarbazide method (EPA Method 7196A). Assuming this was the true Cr (VI) concentration, the recovery of Cr (VI) concentration using the IC method was 100.2 ± 3.4% (data not shown), demonstrating trueness for Cr (VI) quantification in the surface water sample. For Cr (VI) quantification using the IC method, the surface water was diluted 1000 times with reagent water to fit the Cr (VI) concentration within the calibration range.

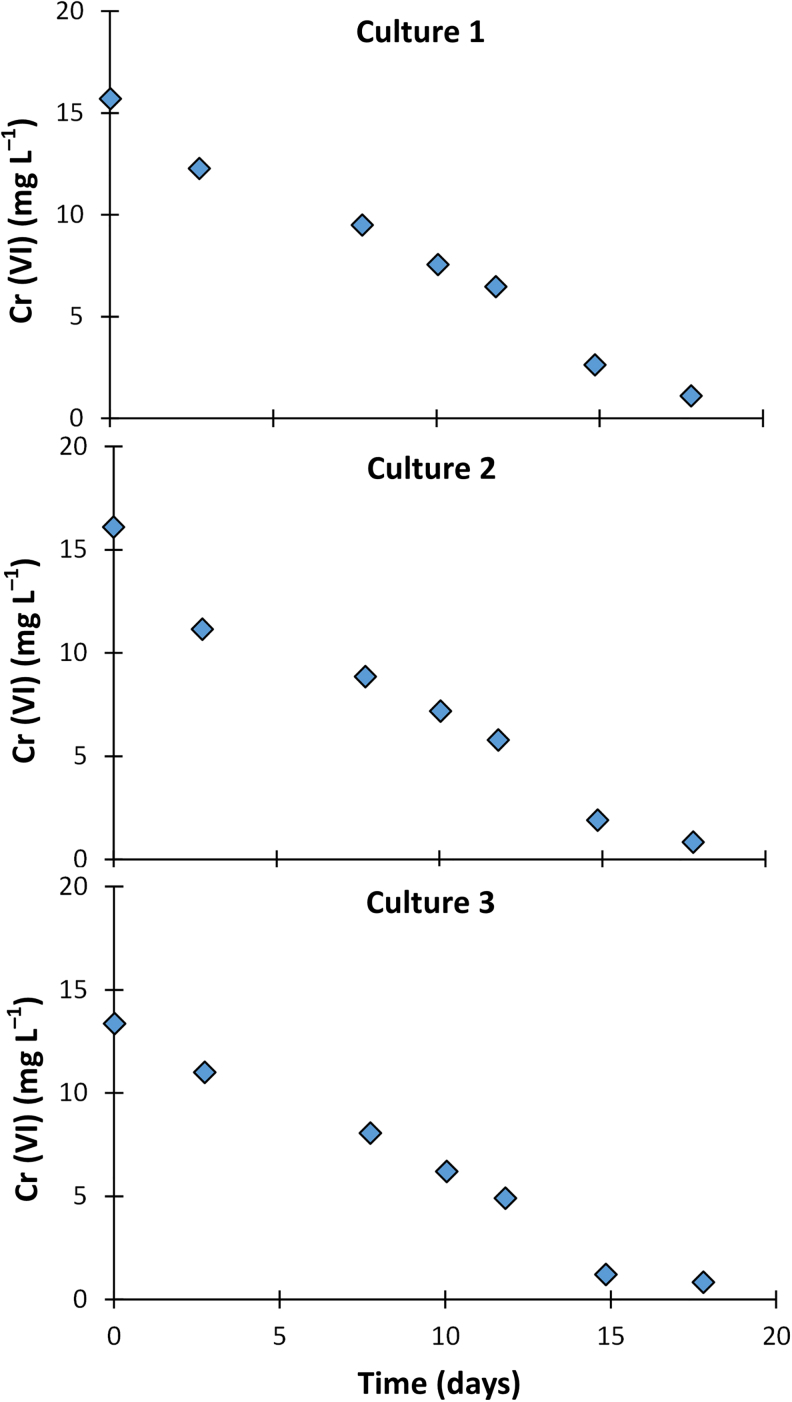

We further applied the IC analytical method to simultaneously track concentrations of anions in typical batch microcosms used commonly in laboratory settings. The microcosms in this study were focused on abiotic and microbiological Cr (VI) reduction. Figure 3 shows the time course concentrations of Cr (VI) (naturally present and spiked) and , , and Cl– (naturally present anions in the soil matrix). The concentration of Cr (VI) decreased from 90 mg/L to below detection limit in ∼8 h, likely from abiotic reduction by reducing agents in the soil such as sulfide and iron bearing minerals and/or microbial reduction to Cr (III) (Chen and Hao, 1998; Kim et al., 2001; Joe-Wong et al., 2017). The concentrations of and Cl– did not change significantly during the incubation time in the soil microcosms (Fig. 3). Figure 4 tracks concentrations of Cr (VI) in culture-only microcosms focused on microbial reduction of Cr (VI) using a mixed culture. Cr (VI) concentration was reduced from ∼15 to <1 mg/L in ∼18 days. Data from Figs. 3 and 4 highlight the applicability of the IC method in laboratory experiments using both complex matrices containing multiple analytes and simple matrices focused only on Cr (VI).

FIG. 3.

Concentrations of Cr (VI), ,and Cl– during incubation in replicate soil microcosms. Note that Cl– is plotted on the secondary y-axis.

FIG. 4.

Concentrations of Cr (VI) during incubation in replicate culture-only microcosms.

Owing to the capability of quantifying several anions simultaneously, the IC method developed in this study is useful to environmental practitioners, academic and research organizations, and other industries that routinely measure Cr (VI) and co-occurring anions. An ion chromatograph equipped with a suppressed conductivity detector is a common instrumentation that many laboratories possess for quantification of common inorganic anions (e.g., Cl–, , and ) by EPA Method 9056A. Thus, the method developed can be easily adapted by laboratories that use the most common IC instrument. Our study shows that Cr (VI), As (V), Se (VI), and in the low microgram per liter concentration range can be measured without pretreatment of the sample or postcolumn derivatization. The IC method from this work was shown to be reliable, precise, accurate, and suitable for monitoring important anions in environmental aqueous media, industrial wastewaters, and laboratory experiments.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ibrahim Ibrahim and Anton Sachs for their assistance in conducting the laboratory microcosm experiments.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under NSF CA no. EEC-1449501. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NSF.

References

- Allegrini, F., and Olivieri, A.C. (2014). IUPAC-consistent approach to the limit of detection in partial least-squares calibration. Anal. Chem. 86, 7858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, N., Reeder, R.J., and Strongin, D.R. (2011). Photoinduced oxidation of arsenite to arsenate on ferrihydrite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzoniti, M.C., Mentasti, E., and Sarzanini, C. (1999). Simultaneous determination of inorganic anions and metal ions by suppressed ion chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 382, 291 [Google Scholar]

- California State Water Quality Control Board, 2020. Chromium-6 drinking water MCL. Available at: https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/drinking_water/certlic/drinkingwater/Chromium6.html (accessed May20, 2021)

- Chen, J.M., and Hao, O.J. (1998). Microbial chromium (VI) reduction. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 28, 219 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.D., Kargacin, B., Klein, C.B., and Costa, M. (1993). Mechanisms of chromium carcinogenicity and toxicity. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 23, 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M. (1997). Toxicity and carcinogenicity of Cr (VI) in animal models and humans. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 27, 431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A.G., Fajardo-Williams, D., Bondank, E., Esquivel-Elizondo, S., and Krajmalnik-Brown, R. (2017). Coupling bioflocculation of Dehalococcoides mccartyi to high-rate reductive dehalogenation of chlorinated ethenes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 11297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A.G., Fajardo-Williams, D., Kegerreis, K.L., Parameswaran, P., and Krajmalnik-Brown, R. (2016). Impact of ammonium on syntrophic organohalide-respiring and fermenting microbial communities. Msphere 1, e00053-00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A.G., Kang, D.-W., Nelson, K.G., Fajardo-Williams, D., Miceli, III, J.F., Done, H.Y., Popat, S.C., and Krajmalnik-Brown, R. (2014). Selective enrichment yields robust ethene-producing dechlorinating cultures from microcosms stalled at cis-dichloroethene. PLoS One 9, e100654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A.G., Parameswaran, P., Fajardo-Williams, D., Halden, R.U., and Krajmalnik-Brown, R. (2012). Role of bicarbonate as a pH buffer and electron sink in microbial dechlorination of chloroethenes. Microb. Cell Fact. 11, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destanoğlu, O., and Gümüş Yılmaz, G. (2016). Determination of cyanide, thiocyanate, cyanate, hexavalent chromium, and metal cyanide complexes in various mixtures by ion chromatography with conductivity detection. J. Liquid Chromatogr. Related Technol. 39, 465 [Google Scholar]

- El-Shahawi, M., Bashammakh, A., and Abdelmageed, M. (2011). Chemical speciation of chromium (III) and (VI) using phosphonium cation impregnated polyurethane foams prior to their spectrometric determination. Anal. Sci. 27, 757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammelgaard, B., Liao, Y.-P., and Jøns, O. (1997). Improvement on simultaneous determination of chromium species in aqueous solution by ion chromatography and chemiluminescence detection. Anal. Chim. Acta. 354, 107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, S., Oh, B.-T., Schnoor, J.L., and Alvarez, P.J. (2002). Degradation of TCE, Cr (VI), sulfate, and nitrate mixtures by granular iron in flow-through columns under different microbial conditions. Water Res. 36, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.C. (2010). Quantitative Chemical Analysis , 8th ed. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company [Google Scholar]

- Hautman, D.P., Munch, D.J., Eaton Andrew, D., and Haghani Ali, W.. (1999). EPA Method 314.0: Determination of perchlorate in drinking water using ion chromatography. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.397.9773&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed May20, 2021)

- Ike, M., Miyazaki, T., Yamamoto, N., Sei, K., and Soda, S. (2008). Removal of arsenic from groundwater by arsenite-oxidizing bacteria. Water Sci. Technol. 58, 1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inczedy, J., Lengyel, T., Ure, A.M., Gelencsér, A., and Hulanicki, A. (1998). Compendium of Analytical Nomenclature. Hoboken: Blackwell Science [Google Scholar]

- Joe-Wong, C., Brown, Jr, G.E., and Maher, K. (2017). Kinetics and products of chromium (VI) reduction by iron (II/III)-bearing clay minerals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 9817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, S., Robles, A., Aguiar, S., and Delgado, A.G. (2021). The occurrence and ecology of microbial chain elongation of carboxylates in soils. ISME J. DOI: 10.1038/s41396-021-00893-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlson, U., and Frankenberger Jr, W. (1986). Determination of selenate by single-column ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 368, 153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khamkhash, A., Srivastava, V., Ghosh, T., Akdogan, G., Ganguli, R., and Aggarwal, S. (2017). Mining-related selenium contamination in Alaska, and the state of current knowledge. Minerals 7, 46 [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C., Zhou, Q., Deng, B., Thornton, E.C., and Xu, H. (2001). Chromium (VI) reduction by hydrogen sulfide in aqueous media: Stoichiometry and kinetics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kończyk, J., Muntean, E., and Michalski, R. (2018). Simultaneous determination of chromate and common inorganic anions using suppressed ion chromatography. Chem. Environ. Biotechnol. 21, 11 [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H., and Choi, W. (2002). Photocatalytic oxidation of arsenite in TiO2 suspension: Kinetics and mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 3872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaught, A.D., and Wilkinson, A. (1997). Compendium of Chemical Terminology. Oxford: Blackwell Science [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, H., and Frankenberger, W. (1988). Simultaneous analysis of selenate and selenite by single-column ion chromatography. Chromatographia 25, 585 [Google Scholar]

- Metrohm USA. Determination of hexavalent chromium (Cr +6) by US EPA method 218.7. Available at: https://www.metrohm.com/en-us/applications/AN-U-US-001 (accessed May20, 2021)

- Miao, Z., Brusseau, M.L., Carroll, K.C., Carreón-Diazconti, C., and Johnson, B. (2012). Sulfate reduction in groundwater: Characterization and applications for remediation. Environ. Geochem. Health. 34, 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalski, R. (2003). Ion chromatography method for the determination of trace levels of chromium (VI) in water. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 13, 73 [Google Scholar]

- Munch, D.J., Wasko, M., Flynt, E., Wendelken, S.C., Scifres, J., Mario, J.R., Hunt, M., Gregg, D., Schaeffer, T., and Clarage, M.. (2005). Validation and peer review of US Environmental Protection Agency chemical methods of analysis. Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.544.7378&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed May20, 2021)

- Onchoke, K.K., and Sasu, S.A. (2016). Determination of Hexavalent Chromium (Cr (VI)) concentrations via ion chromatography and UV-Vis spectrophotometry in samples collected from nacogdoches wastewater treatment plant, East Texas (USA). Adv. Environ. Chem. 2016, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Parker, D.R., Seyfferth, A.L., and Reese, B.K. (2008). Perchlorate in groundwater: A synoptic survey of “pristine” sites in the coterminous United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrzyńska, K. (2002). Determination of selenium species in environmental samples. Microchim. Acta. 140, 55 [Google Scholar]

- Rakhunde, R., Deshpande, L., and Juneja, H. (2012). Chemical speciation of chromium in water: A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 776 [Google Scholar]

- Rangan, S.M., Mouti, A., LaPat-Polasko, L., Lowry, G.V., Krajmalnik-Brown, R., and Delgado, A.G. (2020). Synergistic zerovalent Iron (Fe0) and microbiological trichloroethene and perchlorate reductions are determined by the concentration and speciation of Fe. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 14422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley, R.G. (1992). Chemical Contaminants on DOE Lands and Selection of Contaminant Mixtures for Subsurface Science Research. Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, Office of Energy Research, Subsurface Science Program [Google Scholar]

- Salnikow, K., and Zhitkovich, A. (2008). Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in metal carcinogenesis and cocarcinogenesis: Nickel, arsenic, and chromium. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, A., and Gupta, V.B. (2011). Methods for the determination of limit of detection and limit of quantitation of the analytical methods. Chron. Young Sci. 2, 21 [Google Scholar]

- Šikovec, M., Franko, M., Novič, M., and Veber, M. (2001). Effect of organic solvents in the on-line thermal lens spectrometric detection of chromium (III) and chromium (VI) after ion chromatographic separation. J. Chromatogr. A 920, 119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmaus, C.M. (2016). Perchlorate in water supplies: Sources, exposures, and health effects. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 3, 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. Sensitive Determination of Hexavalent Chromium in Drinking Water. Sunnyvale, CA: Thermo Fisher Scientific [Google Scholar]

- Thermo Scientific. (2013). Dionex Onguard II Cartridges Product Manual. Waltham, MA: Thermo Scientific [Google Scholar]

- Urbansky, E.T. (2002). Perchlorate as an environmental contaminant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 9, 187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US EPA. (1992). Method 7196A: Chromium, Hexavalent (Colorimetric). Cincinnati, OH: United States Environmental Protection Agency. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-12/documents/7196a.pdf

- US EPA. (1996). DBP/ICR Analytical Methods Manual. Cincinnati, OH: United States Environmental Protection Agency [Google Scholar]

- US EPA. (2007). Method 9056A: Determination of Inorganic Anions by Ion Chromatography. Cincinnati, OH: United States Environmental Protection Agency. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-12/documents/9056a.pdf

- US EPA. (2010). Chromium in drinking water. Available at: https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/chromium-drinking-water (accessed January26, 2021)

- Wang, Z., Bush, R.T., Sullivan, L.A., and Liu, J. (2013). Simultaneous redox conversion of chromium (VI) and arsenic (III) under acidic conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 6486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, J. (2016). Handbook of Ion Chromatography , 3 Volume Set. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2003). Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality | Chromium. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549950

- WHO. (2018). Arsenic—Fact sheets. World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/arsenic (accessed August3, 2020)

- Yeo, J., and Choi, W. (2009). Iodide-mediated photooxidation of arsenite under 254 nm irradiation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J., Amy, ssG., Chung, J., Sohn, J., and Yoon, Y. (2009). Removal of toxic ions (chromate, arsenate, and perchlorate) using reverse osmosis, nanofiltration, and ultrafiltration membranes. Chemosphere 77, 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffiro, A., Zimmerman, M., Wendelken, S., Smith, G., and Munch, D. (2011). METHOD 218.7: Determination of Hexavalent Chromium in Drinking Water by Ion Chromatography with Post-Column Derivatization and UV-Visible Spectroscopic Detection. Cincinnati, OH: United States Environmental Protection Agency [Google Scholar]

- Zhitkovich, A. (2011). Chromium in drinking water: Sources, metabolism, and cancer risks. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 24, 1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv-El, M., Delgado, A.G., Yao, Y., Kang, D.-W., Nelson, K.G., Halden, R.U., and Krajmalnik-Brown, R. (2011). Development and characterization of DehaloR^2, a novel anaerobic microbial consortium performing rapid dechlorination of TCE to ethene. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 92, 1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]