Abstract

Background

This study aimed to measure the levels of anxiety and burnout among healthcare workers, including attending physicians, residents, and nurses in intensive care units during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional survey analysis of healthcare workers in our institution. Data were collected on demographic variables, COVID-19 symptoms and test, disease status, anxiety level (assessed by the Beck Anxiety Inventory), and burnout level (measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory). Subscales of the burnout inventory were evaluated separately.

Results

A total of 104 participants completed the survey. Attending physicians, residents, and nurses constituted 25%, 33.7%, and 41.3% of the cohort, respectively. In comparison to untested participants, those tested for COVID-19 had a lower mean age (p = 0.02), higher emotional exhaustion and depersonalization scores (p = 0.001, 0.004, respectively), and lower personal accomplishment scores (p = 0.004). Furthermore, moderate to severe anxiety was observed more frequently in tested participants than untested ones (p = 0.022). Moderate or severe anxiety was seen in 23.1% of the attending physicians, 54.3% of the residents, and 48.8% of the nurses (p = 0.038). Emotional exhaustion, personal accomplishment, and depersonalization scores differed depending on the position of the healthcare workers (p = 0.034, 0.001, 0.004, respectively).

Conclusion

This study revealed higher levels of anxiety and burnout in younger healthcare workers and those tested for COVID-19, which mainly included residents and nurses. The reasons for these observations should be further investigated to protect their mental health.

Keywords: Anesthetist, Anxiety, Burnout syndrome, COVID-19, Intensive care unit

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first detected in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020.1 In Turkey, the first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed on March 10, 2020, and the first case of death due to this disease was reported on March 15, 2020.2

The rapidly growing numbers of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths have led to increased anxiety in people during the pandemic. Healthcare workers (HCWs) are one of the most affected groups as they give care to infected people directly.2 Stress and anxiety disorders in the general population and HCWs were expected to increase during the COVID-19 pandemic,3, 4, 5 as seen before during both the severe acute respiratory syndrome6, 7 and Middle East respiratory syndrome8 epidemics.

Stress disorders and burnout syndrome (BOS) have been more prevalent among anesthetists9, 10 and intensive care unit (ICU) nurses.11, 12 The huge number of critically ill patients admitted to ICUs during the pandemic has placed a substantial burden on HCWs, the consequences of which have not been studied extensively.

During the pandemic, the ICU of our institution has been operating with 31 beds for patients with COVID-19 and 21 beds for other patients as well as 35 attending physicians (each working 3 night shifts per month) and 35 residents (each doing 8 night shifts per month). The present study aimed to evaluate the levels of anxiety and burnout among attending physicians, residents, and nurses in the ICU of our institution.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional survey analysis of HCWs – consisting of attending physicians, residents, and nurses – in the tertiary ICUs of our institution. The study was approved by the local ethics committee on July 30, 2020 (No. 1577) and was performed between May 15, 2020, and May 25, 2020 (NCT04604119). All participants gave informed consent to take part in the survey, which was administered electronically.

The survey consisted of 3 distinct sections. In the first section, we asked for demographic information including age, sex, marital status (married vs. others), current position (attending, resident, or nurse), past medical history, and place of residence during the pandemic. Participants were also asked a multiple-choice question about what made them “feel well during the pandemic”, with the possible answers being “staying at home”, “cooking”, “caring for family and children”, “working”, “caring for patients”, “performing routine work”, “learning new things”, or “searching for information about COVID-19.”

There was no systematic screening policy for COVID-19 in HCWs across our country during the pandemic, even if they were in charge of giving care to patients with COVID-19. The test was performed only in case of having symptoms related to COVID-19 or unprotected close contact with a patient with COVID-19. Hence, participants were also required to provide personal details on the symptoms, test, and status of COVID-19.

The second section of the survey comprised of the validated Turkish version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),13, 14 which included 21 questions about the somatic symptoms of anxiety. Participants indicated to what extent they had been bothered by each symptom in the past week by selecting 0 (not at all), 1 (mildly), 2 (moderately), or 3 (severely); thus, the total anxiety score could range between 0 and 63. Participants were categorized as having no or mild anxiety if the total BAI score was 0–16, and moderate to severe anxiety if it was over 16.15

In the last section, we used the validated Turkish version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) to evaluate BOS components.16, 17 The MBI contains 9 items about emotional exhaustion (EE), 5 items about depersonalization (DP), and 8 items about personal accomplishment (PA), each of which is rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale. Higher scores on the EE and DP subscales and lower scores on the PA subscale imply higher levels of burnout.18 Unlike the original MBI, the Turkish version has 5-point questions that are scored from 0 to 4. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for EE, PA, and DP were found to be 0.83, 0.67, and 0.72, respectively, in the validation study of the Turkish version of the MBI19 and 0.904, 0.819, and 0.805, respectively, in our study.

BAI and MBI scores were compared in relation to age, gender, marital status, presence of chronic illness, HCW position, and history of experiencing COVID-19 symptoms, testing for COVID-19, and contracting the disease.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation if distributed normally and as median (interquartile range) if distributed abnormally. Qualitative variables were presented as percentages. Comparison of normally distributed data was performed by the independent samples t-test or analysis of variance. Abnormally distributed data were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. The chi-square test was employed to compare categorical variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used for correlation assessment when groups were distributed normally; otherwise, Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted. Differences were considered statistically significant for p-values less than 0.05.

Results

A total of 104 participants completed the survey, of whom 25% (n = 26) were attending physicians, 33.7% (n = 35) residents, and 41.3% (n = 43) nurses (Table 1). The most common activity that made HCWs feel well during the pandemic was staying at home (75.2%), whereas the least common ones were working (8.9%) and searching for information about COVID-19 (8.9%). The total BAI score for the entire cohort was 17.5 (8–25). Moderate to severe anxiety was noticed in 44.2% of all participants. EE, PA, and DP scores were 22 (15–28.7), 23 (17–26), and 6 (3–9), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic details and details for COVID-19 related parameters, Beck anxiety inventory, and Maslach burnout inventory for all participants.

| Parameter | All cohort |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 29 (27–36) |

| Female (%) | 70.2 |

| Married (%) | 46.2 |

| Chronic disease, positive (%) | 11.5 |

| Accommodation during pandemic | |

| Self-home (%) | 90.4 |

| Another home (%) | 3.8 |

| The others, e.g., hotel, dormitory (%) | 5.8 |

| Position (%) | |

| Attending physician | 25 |

| Resident doctor | 33.7 |

| Nurse | 41.3 |

| History of COVID-19 symptom, positive (%) | 50.0 |

| History of COVID-19 test, positive (%) | 71.2 |

| History of COVID-19 disease, positive (%) | 7.7 |

| Which activity makes you feel well? (%) | |

| Staying at home | 75.2 |

| Cooking | 29.7 |

| Caring for family and children | 25.7 |

| Working | 8.9 |

| Having attention to inpatients | 11.9 |

| Performing routine work | 21.8 |

| Learning new things | 28.7 |

| Searching for COVID-19 | 8.9 |

| Beck anxiety inventory (%) | |

| No or mild anxiety | 55.8 |

| Moderate to severe anxiety | 44.2 |

| Maslach burnout inventory | |

| Emotional exhaustion, median (IQR) | 22 (15–28.7) |

| Personal accomplishment, median (IQR) | 23 (17–26) |

| Depersonalization, median (IQR) | 6 (3–9) |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, IQR: interquartile range.

Parameters in the first section of the survey were compared with the BAI and MBI. History of COVID-19 symptoms was found to be significantly associated with BAI categories (p = 0.018), and age was correlated with the EE score (r = -0.197, p = 0.045). The DP score was 5 (2–8) in married HCWs and 7 (4.2–10) in others (p = 0.021). HCWs with a COVID-19 history had a DP score of 9 (8.2–10.7), whereas it was 6 (3–9) in those without a COVID-19 history (p = 0.037).

COVID-19 test status and position of the HCWs were caused significant differences in Beck anxiety categories and all subscales of MBI. They are separately given below.

Overall, 71.2% of the cohort reported having tested for COVID-19. Demographic variables were compared between tested and untested HCWs (Table 2). The median age of tested HCWs was 28 (27–31) years, while untested HCWs had a median age of 35 (27–43) (p = 0.02). COVID-19 symptoms were observed in 58.1% and 30% of the tested and untested participants, respectively (p = 0.009).

Table 2.

Comparison of various parameters with status of COVID-19 test history.

| Parameter | Status of COVID-19 test history |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 28 (27-31) | 35 (27-43) | 0.02 |

| Female (%) | 73 | 63.3 | 0.330 |

| Married (%) | 41.9 | 56.7 | 0.171 |

| Chronic disease, positive (%) | 10.8 | 13.3 | 0.715 |

| Accommodation during pandemic (%) | 0.432 | ||

| Self-home | 89.2 | 93.3 | |

| Another home | 5.4 | - | |

| The others, e.g., hotel, dormitory | 5.4 | 6.7 | |

| History of COVID-19 symptom, positive (%) | 58.1 | 30 | 0.009 |

| Position (%) | 0.000 | ||

| Attending physician | 14.9 | 50 | |

| Resident doctor | 45.9 | 3.3 | |

| Nurse | 39.2 | 46.7 | |

COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range.

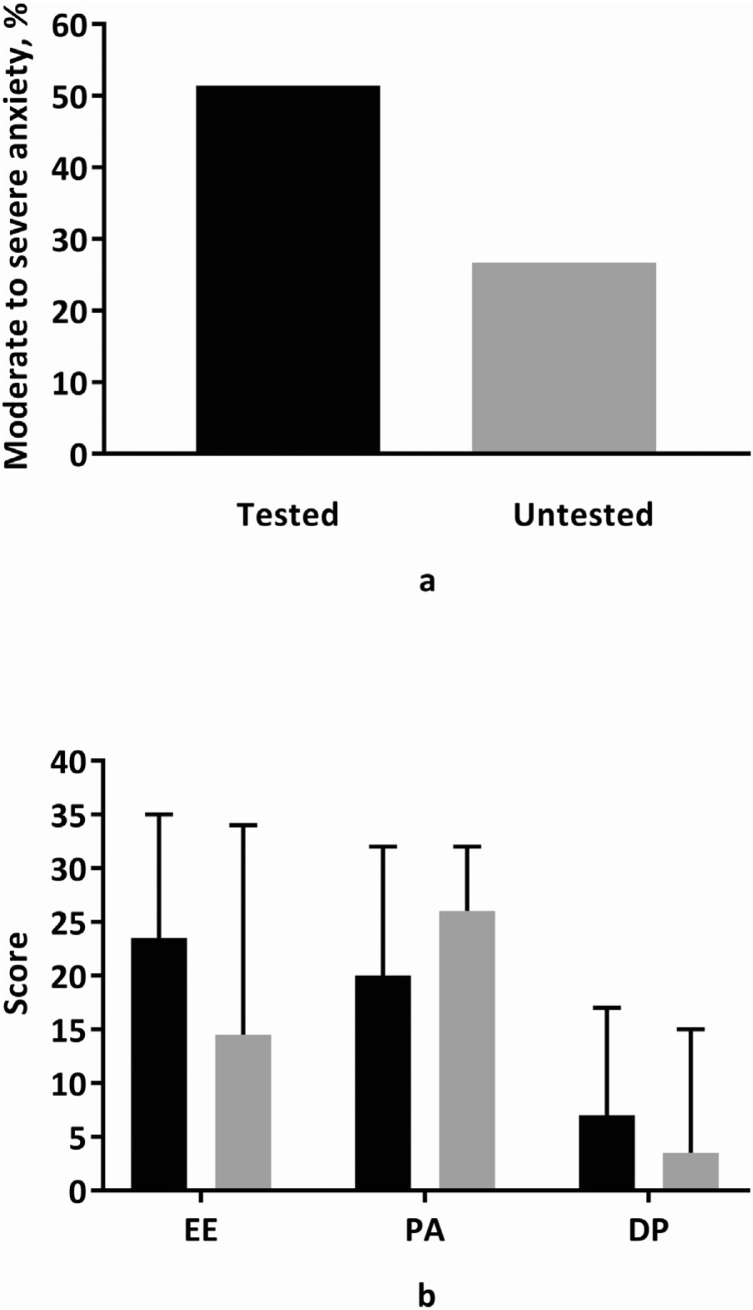

Moderate to severe anxiety was present in 51.4% of the tested participants and 26.7% of untested ones (p = 0.022; Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Comparison of healthcare workers’ COVID-19 test history with moderate to severe anxiety frequency (p = 0.022) (Fig. 1a) and emotional exhaustion (p = 0.001), personal accomplishment (p = 0.004), depersonalization (p = 0.004) scores (Fig. 1b). DP, depersonalization; EE, emotional exhaustion; PA, personal accomplishment. The black bar represents for healthcare workers with COVID-19 test history and gray bar represents for healthcare workers without it.

Tested HCWs had an EE score of 23.5 (17–29), while this score was 14.5 (11–26.7) in untested ones (p = 0.001; Fig. 1b). The PA score was 20 (17–26) in the tested group and 26 (22.5–28) in the untested group (p = 0.004). DP scores in the tested and untested groups were 7 (3–10) and 3.5 (0.75–7), respectively (p = 0.004).

Attending physicians had a median age of 43 (39–49) years; residents, 29 (28–31) years; and nurses, 27 (25–28) years (p = 0.000; Table 3). When binary comparisons were performed, the median ages were statistically different between attending physicians and nurses, attending physicians and residents, and residents and nurses (p = 0.000 for all; Table 4). Attending physicians had a higher marriage rate (84.6%) than residents (37.1%, p = 0.000) and nurses (30.2%, p = 0.000).

Table 3.

Comparison of various parameters with position of the healthcare worker.

| Parameter | Position |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attending physician | Resident | Nurse | p | |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 43 (39–49) | 29 (28–31) | 27 (25–28) | 0.000 |

| Female (%) | 73.1 | 65.7 | 72.1 | 0.774 |

| Married (%) | 84.6 | 37.1 | 30.2 | 0.000 |

| Chronic disease, positive (%) | 3.8 | 11.4 | 16.3 | 0.293 |

| Accommodation during pandemic (%) | 0.029 | |||

| Self-home | 100 | 82.9 | 90.7 | |

| Another home | - | 11.4 | - | |

| The others, e.g. hotel, dormitory | - | 5.4 | 9.3 | |

| History of COVID-19 symptom, positive (%) | 42.3 | 54.3 | 51.2 | 0.639 |

| History of COVID-19 test, positive (%) | 42.3 | 97.1 | 67.4 | 0.000 |

| History of COVID-19 disease, positive (%) | - | 20 | 2.3 | 0.003 |

COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range.

Table 4.

Binary comparison of healthcare worker’s position with age, marital status, accommodation, COVID-19 test and disease history.

| Parameter | Attending physician-resident | Attending physician-nurse | Resident-Nurse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (p) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Marital status (p) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.520 |

| Accommodation during pandemic (p) | 0.084 | 0.109 | 0.068 |

| History of COVID-19 test (p) | 0.000 | 0.04 | 0.001 |

| History of COVID-19 disease (p) | 0.015 | 0.433 | 0.01 |

COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019.

Among residents, 97.1% reported having undergone a COVID-19 test, which was significantly greater than the test exposure rate among attending physicians (42.3%, p = 0.004) and nurses (67.4%, p = 0.001). Although reported in none of the attending physicians, COVID-19 was diagnosed in 20% of the residents and 2.3% of the nurses (p = 0.003). The disease was more prevalent in residents than attending physicians and nurses (p = 0.015 and 0.01, respectively).

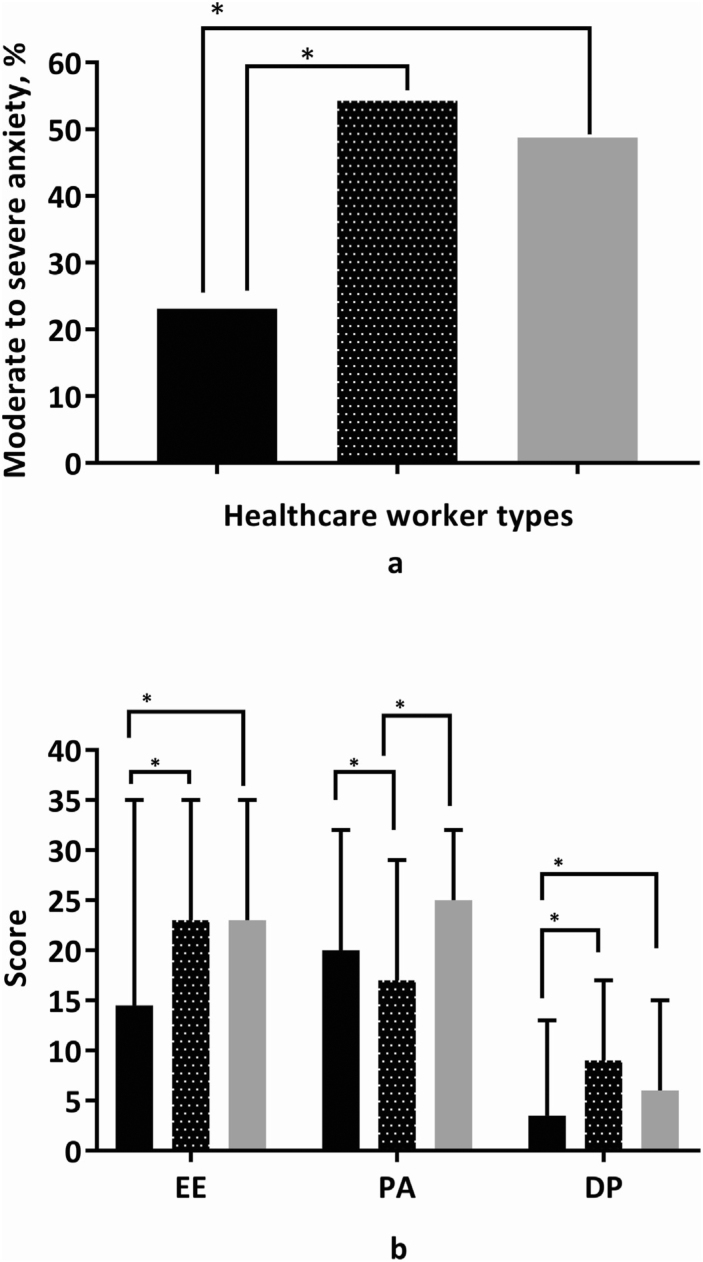

Moderate or severe anxiety was seen in 23.1% of the attending physicians, 54.3% of the residents, and 48.8% of the nurses (p = 0.038; Fig. 2a). A smaller proportion of attending physicians had moderate or severe anxiety compared to residents (p = 0.014) and nurses (p = 0.034).

Figure 2.

Comparison of healthcare workers’ position with moderate to severe anxiety frequency (p = 0.038) (Fig. 2a) and emotional exhaustion (p = 0.023), personal accomplishment (p = 0.000), depersonalization (p = 0.000) scores (Fig. 2b). DP, depersonalization; EE, emotional exhaustion; PA, personal accomplishment.

The black bar represents for attending physicians, dotted bar represents for resident doctors and gray bar represents for nurses.

*p-value is less than 0.05.

The distributions of EE, PA, DP scores were significantly different among HCWs (p = 0.023, 0.000, and 0.000, respectively; Fig. 2b). Residents and nurses had almost the same EE scores (p = 0.872), both of which turned out to be higher than that for attending physicians (p = 0.007 and 0.003, respectively; Fig. 2b). The PA score for residents was lower than that for attending physicians (p = 0.039) and nurses (p = 0.000). Attending physicians and nurses had a significantly lower DP score compared to residents (p = 0.000 and 0.006, respectively).

Discussion

This study evaluated anxiety and burnout among HCWs working in the ICU during the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 test status and HCW position were identified as factors affecting both of the aforementioned parameters.

Tested HCWs were younger than untested ones. This can be attributed to the low test exposure rate among attending physicians, who were older than residents and nurses. The position of tested HCWs was different from that of untested ones. While residents were the most frequently tested HCWs, attending physicians represented the least frequently tested ones.

This study was conducted in the tertiary ICU of a teaching hospital, where services such as invasive procedures, daily physical examinations, and patient care were mostly offered by residents under the supervision of attending physicians. Nurses performed their routine nursing tasks and helped residents when necessary. Therefore, residents and nurses inevitably had more contact with patients with COVID-19 than did attending physicians, thus needing to undergo more frequent COVID-19 tests. The majority of the residents tested for COVID-19 even though only approximately half of them reported COVID-19 symptoms, which suggests that residents had more unprotected close contact with patients with COVID-19. This probably explains why COVID-19 was most frequently observed in residents. Another reason for this finding might be the fact that procedures with a high risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission (e.g., endotracheal intubation) were more often performed by residents, as shown by El-Boghdadly et al.20

Lee et al., who used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, found that 30.7% of HCWs (including anesthetists and ICU nurses) experienced at least moderate anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.21 Que et al. measured anxiety level during this pandemic by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and found moderate to severe anxiety in 11.98% of physicians, 8.98% of residents, and 14.9% of nurses.22 These proportions are lower than those observed in our study, which might be due to the scale used, differences in the target population, and national and local precautions taken to control the pandemic and improve mental health of HCWs. Our findings showed that tested HCWs were more anxious, probably due to the fear of becoming infected. Residents and nurses had the same level of anxiety and were more anxious than attending physicians, which is attributable to increased close contact with patients with COVID-19.

There are multiple ways to define BOS. Despite various definitions,18 the use of cut-off values for subscales has not been advised since 2016.23 Moreover, the Turkish MBI has not been evaluated in terms of cut-off values, and due to the difference in the number of possible responses to each question (i.e., 5 instead of 7), it would not be right to use categorization methods practiced for 7-point questions. These reasons prevented us from comparing our results head-to-head with those of similar studies from other countries. Notwithstanding this limitation, we acquired valuable information regarding BOS.

Anesthesia department and ICUs were places known with high BOS frequency both for anesthetists9 and nurses.11 In our study, attending physicians were found to be the least affected group with regard to the DP subscale, and residents were the worst group in the EE, PA, and DP subscales. The reason for this finding could be related to factors already known before the pandemic. Chiron et al. investigated BOS in 193 anesthetists in France and reported that the incidence of high EE decreased with age.24 Vargas et al. demonstrated that working in the ICU and being younger than 40 years old were independent risk factors for BOS in an Italian cohort.25 Additionally, Nyssen et al. showed that BOS was more prevalent among younger doctors.9 In our study, residents were the youngest group of HCWs, which may be one of the underlying causes of poor MBI scores in this group. With the increase of age, attending physicians may have learned to cope well with stress. Residents might have been unsupervised or empowered inadequately by their seniors, therefore failing to develop the ability to cope with stressful conditions. Besides, the inequality in the number of night shifts per month between residents and attending physicians might have contributed to this finding. The pandemic itself might also have given rise to some concerns such as fear of getting infected and dying, undefined quarantine length, excessive workload, inadequate protective personal equipment, and fear of exclusion.3, 26 Residents had longer close contact with patients with COVID-19, performed most of the invasive procedures themselves, were more frequently affected by the disease, and underwent more COVID-19 tests. It could be speculated that these factors, too, accounted for the poor MBI scores in residents.

COVID-19 has affected people all over the world, so many countries have taken national and local actions to protect mental health of HWCs.26, 27, 28 The Turkish Ministry of Health has developed a mobile application for HCWs to use during the pandemic.29 However, it was downloaded only more than a thousand times until October 17, which seems quite infrequently given the number of HCWs in Turkey (over 1 million). Reduced workload has been shown to serve as the most important factor in reducing BOS,10 so additional measures should be taken to lighten the workload for HCWs, especially residents. There are many other possible steps to improve their mental health without interrupting their education process.30, 31

There are some limitations to the current study. Demographics and other variables were not detailed to limit the time required to fill the survey for a better participation rate. Furthermore, total weekly working hours were not separately calculated for different HCW groups, which might be less in attending physicians and more in the other groups due to the presence of more attending physicians and fewer residents in our institution.

Conclusion

The present study indicated that younger HCWs, especially residents and nurses, who work in ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic should be further supported and encouraged physically and mentally. Moreover, working conditions of residents – including the number of night shifts and scope of their responsibilities – should be revised. This could diminish the incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder likely to occur as a result of the pandemic.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic 2020 [cited 19.10.2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 2.Di Tella M., Romeo A., Benfante A., et al. Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26:1583–1587. doi: 10.1111/jep.13444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Si M.Y., Su X.Y., Jiang Y., et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:113. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Tan B.Y.Q., et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chong M.Y., Wang W.C., Hsieh W.C., et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:127–133. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tam C.W., Pang E.P., Lam L.C., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1197–1204. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S.M., Kang W.S., Cho A.R., et al. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;87:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyssen A.S., Hansez I., Baele P., et al. Occupational stress and burnout in anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:333–337. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kluger M.T., Townend K., Laidlaw T. Job satisfaction, stress and burnout in Australian specialist anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:339–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poncet M.C., Toullic P., Papazian L., et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:698–704. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mealer M.L., Shelton A., Berg B., et al. Increased Prevalence of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Critical Care Nurses. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2007;175:693–697. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-735OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck A.T., Epstein N., Brown G., et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulusoy M., Sahin N.H., Erkmen H. Turkish Version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory: Psychometric Properties. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1998;12:163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Julian L.J. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63 Suppl 11:S467–72. doi: 10.1002/acr.20561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maslach C., Jackson S.E., Schwab R.L. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto: 1986. Maslach burnout inventory: manual. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ergin C. Maslach tükenmişlik ölçeğinin Türkiye sağlık personeli normları. Psikiyatri Psikoloji Psikofarmakoloji (3P) Dergisi. 1996;4:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doulougeri K., Georganta K., Montgomery A. “Diagnosing” burnout among healthcare professionals: Can we find consensus? Cogent Medicine. 2016;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.M C. Maslach Tükenmişlik Ölçeği Sağlık Personeli Türkiye Normlarının Silahlı Kuvvetler Sağlık Personeli Tükenmişlik Puanları İle Karşılaştırılmalı Olarak İncelenmesi. Toplum ve Hekim. 2002;17:212–216. [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Boghdadly K., Wong D.J.N., Owen R., et al. Risks to healthcare workers following tracheal intubation of patients with COVID-19: a prospective international multicentre cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:1437–1447. doi: 10.1111/anae.15170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee M.C.C., Thampi S., Chan H.P., et al. Psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic amongst anaesthesiologists and nurses. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e384–e386. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Que J., Shi L., Deng J., et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Problem with Cut Offs for the Maslach Burnout Inventory 2018 [cited 15.10.2020]. Available from: https://www.mindgarden.com/documents/MBI-Cutoff-Caveat.pdf.

- 24.Chiron B., Michinov E., Olivier-Chiron E., et al. Job satisfaction, life satisfaction and burnout in French anaesthetists. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:948–958. doi: 10.1177/1359105309360072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vargas M., Spinelli G., Buonanno P., et al. Burnout Among Anesthesiologists and Intensive Care Physicians: Results From an Italian National Survey. Inquiry. 2020;57 doi: 10.1177/0046958020919263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang L., Li Y., Hu S., et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7 doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Q., Liang M., Li Y., et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chirico F., Nucera G., Magnavita N. Protecting the mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 emergency. BJPsych International. 2021;18:E1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruh Sağlığı Destek Sistemi 2020 [cited 15.10.2020]. Available from: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=tr.gov.saglik.ruhsad&hl=en_US.

- 30.Sneyd J.R., Mathoulin S.E., O’Sullivan E.P., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on anaesthesia trainees and their training. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roycroft M., Wilkes D., Pattani S., et al. Limiting moral injury in healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Occupational Medicine. 2020;70:312–314. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]