Abstract

Background:

Women with signs and symptoms of ischemia, no obstructive coronary artery disease, and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction enrolled in the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study have an unexpectedly high rate of subsequent heart failure (HF) hospitalization. We sought to verify and characterize the HF hospitalizations.

Methods:

A retrospective chart review was preformed on 223 women with signs and symptoms of ischemia, undergoing coronary angiography for suspected coronary artery disease followed for 6± 2.6 years. Data were collected from a single site in the WISE study.

Results:

At the time of study enrollment, the women were 57 ± 11 years of age, all had preserved left ventricular ejection fraction, and 81 (36%) had obstructive CAD (defined as ≥50% stenosis in at least one epicardial artery). Among the 223 patients, 25 (11%) reported HF hospitalizations, of which 14/25 (56%) had recurrent HF hospitalizations (≥ 2 hospitalizations). Medical records were available in 13/25 (52%) women. Left ventricular ejection fraction was measured in all verified cases, and was found to be preserved in 12/13 (92%). HF hospitalization was not related to obstructive CAD.

Conclusion:

Among women with signs and symptoms of ischemia undergoing coronary angiography for suspected obstructive CAD, HF hospitalization at 6-year follow-up was predominantly characterized by a preserved ejection fraction, and not associated with obstructive CAD.

Keywords: Heart Failure, Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction, Coronary Microvascular Disease, Women, Coronary Artery Disease

Background

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes for hospital admission, especially in the aging population1, 2. The association between obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) and HF is well known but few studies have evaluated non-obstructive CAD and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), which is becoming more prevalent than HF with reduced ejection fraction3.

The National Heart Lung and Blood Institute sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study focused on the mechanisms, prognosis and management of ischemic heart disease in women4, 5. Based on this multicenter initiative, it is now clear that obstructive CAD is infrequent in women6-8, and that the majority of women with signs and symptoms of ischemia have coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD)8. It is also evident that women with signs and symptoms of ischemia without obstructive CAD have an elevated risk of major cardiovascular events, including HF,9-11 raising the question whether CMD is mechanistically linked with HFpEF12-14.

To verify and characterize the HF hospitalization in WISE, we performed a retrospective chart review. Given that the majority of patients with HFpEF are women15, 16, and the majority of non-obstructive CAD patients are women (7-8), we hypothesized that women WISE women would predominantly present with HFpEF.

Methods

A retrospective chart review for characterization of HF hospitalization was performed on a cohort of 223 women enrolled at a single site (University of Florida, Gainesville) in the NHLBI-sponsored WISE study and who were followed for a period of 6 years ± 2.6 years. Heart failure hospitalization was verified by a diagnosis of HF in the medical chart. Preserved EF was defined as ≥ 55%, or a clinician’s chart note of “normal” or “preserved” or “not reduced EF”. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria, along with detailed descriptions of each of the study endpoint measurements, have previously been published7, 11, 17. Briefly, the WISE subjects were all women with signs and symptoms of ischemia and objective evidence of ischemia on stress testing and who underwent coronary angiography. A WISE core laboratory (Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI, USA), blinded to clinical data, analyzed all angiograms to characterize the presence and extent of CAD11. Obstructive CAD was defined as ≥50% stenosis in any epicardial coronary artery, non-obstructive CAD was defined as ≥20 but <50%, and no CAD was <20%.

Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics to represent categorical and continuous variables with numbers and percentages or means and standard deviations. Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical analysis to compare the rate of HF among patients with obstructive CAD and non-obstructive CAD.

Results

Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. The average age of subjects at the time of enrollment was 57 ± 11 years, and all subjects had a normal EF (63 ± 11%). The majority of patients (66%) had a family history of CAD, 63% had a history of hypertension, 53% had dyslipidemia and 30% had a history of diabetes.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristicsa

| Characteristic | (n=223) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57 ± 11 |

| LVEF (%) | 63 ± 11 |

| Family history of CAD | 66% |

| Hypertension | 63% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30% |

| Dyslipidemia | 53% |

| Use of lipid lowering medications | 22% |

| Antihypertensive medication use | |

| ACE inhibitors | 30% |

| ARB | 2% |

| Diuretic | 27% |

| Vasodilator | 6% |

| Beta Blocker | 32% |

| Calcium Channel blocker | 13% |

| Aspirin use | 53% |

| Obstructive CAD | 36% |

| No or Non-obstructive CAD | 64% |

Abbreviations: LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction; ACE=angiotensin converting-enzyme; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; CAD=coronary artery disease.

Data expressed as mean ± SD or percentage

Consistent with previous reports from other WISE investigations6,10,11,15, 11% (n=25) of our cohort were hospitalized for HF; 56% (n=14) of whom reported recurrent hospitalization visits (≥ 2 hospitalizations). Medical records were available for 13 of the 25 patients hospitalized for HF, with information on 17 separate hospital admissions. HF hospitalization was verified for all patients. Ejection fraction measured during hospitalization was preserved in 12/13 (92%) patients.

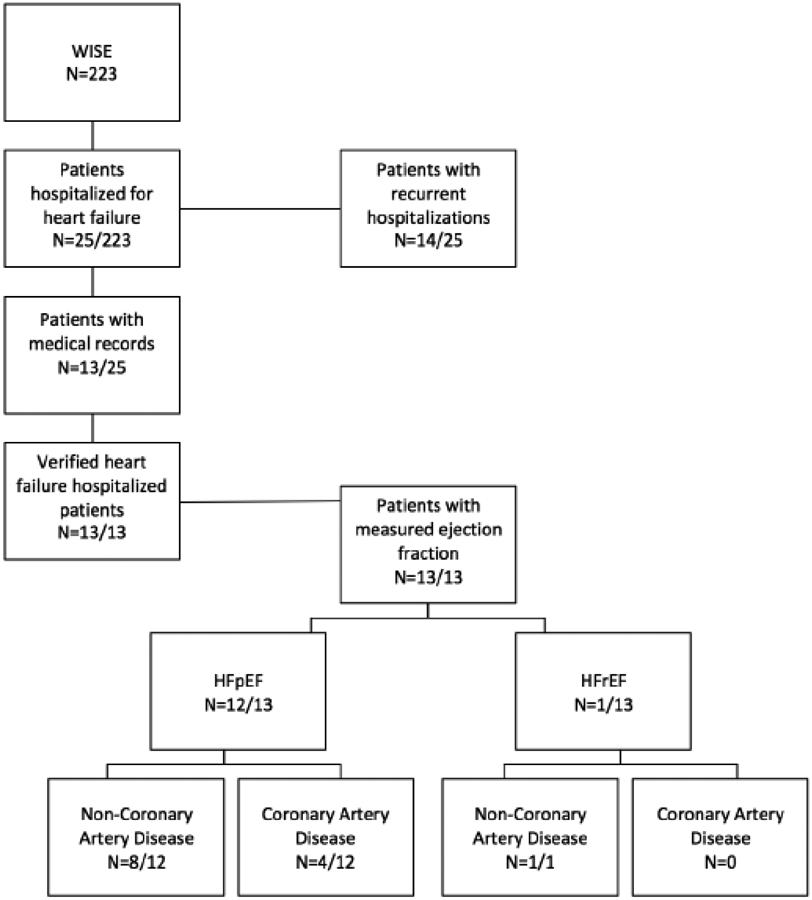

To address whether HF hospitalization was related to obstructive CAD, we stratified the HF hospitalizations by the presence of obstructive CAD. Among the 13 subjects with HF verified hospitalizations, HF hospitalization was not related to obstructive CAD vs non-obstructive CAD (4/13 [31%] vs 9/13 [69%] respectively, p= ns). The distribution of HFpEF and HFrEF according to obstructive, non-obstructive and no CAD is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: HF hospitalization flow chart.

Flow chart of the number of reported HF hospitalizations, the number of verified HF hospitalizations, and the number of EF measures related stratified by CAD status.

Discussion

We previously observed that women with signs and symptoms of ischemia and preserved ejection fraction had an unexpectedly high incidence of HF hospitalization10. Verification of HF and the type of HF (i.e. HFrEF vs. HFpEF) in this cohort was not been well characterized. The current study results verify the hospitalizations as HF, and find that the majority (92%) of verified HF hospitalization were HFpEF, consistent with our hypothesis.

Consistent with our original publication10, we show a similar prevalence of HF (11% vs. 6%, respectively). That the majority of verified HF hospitalization were classified as no or non-obstructive CAD (69%), is also consistent with this prior investigation10. We now extend this previous work by demonstrating that the majority of HF cases are characterized as having a preserved EF. Taken together, the data allow us to speculate that women with ischemic heart disease, non-obstructive CAD and preserved ejection fraction are at increased risk for developing HFpEF.

The mechanism for HF hospitalization remains incompletely understood. Taqueti et al18 previously demonstrated that low coronary flow reserve (CFR) was associated with increased rates of adverse clinical events including cardiovascular death or HF admission. We have consistently found that as many as 50% of women with signs and symptoms of ischemia, but not obstructive CAD, have coronary microvascular dysfunction. Given the small number of event rates in the present investigation, we were not adequately powered to test this specific question. Future studies in a larger population are need to determine the relationship between coronary microvascular dysfunction and heart failure hospitalization – particularly those presenting with preserved ejection fraction.

Our results are limited by record availability only in a slight majority (52%) of HF hospitalizations. Furthermore, the WISE cohort by design includes only women, and may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusions

Among women with signs and symptoms of ischemia, no obstructive CAD and preserved ejection fraction at enrollment, HF hospitalizations are most often HFpEF. Further work is needed to determine the mechanistic relationship between ischemic heart disease in women and the development of HFpEF.

Disclosures/Acknowledgments:

Bakir: none; Nelson: none; Sharif: none; Jones: none; De La Cruz: none; Li: none; Wei: none; Mehta: Gilead; Shufelt: Gilead;Rogatko: none Spotko: none Pepine: NIH Study Section of Cardiovascular Sciences Small Business Activities 2RG1 CVS-K-10, Lilly/Cleveland Clinic DSMB Member for a Phase 2 Efficacy and Safety Study of Ly2484595, Medtelligence, NHLBI Study Section for Progenitor Cell Biology Consortium, NHLBI DSMB Chair for Freedom Trial; Gilead Sciences, Inc , Pfizer, Park-Davis, Sanofi-Aventis, Fujisawa HealthCare Inc, Baxter, Brigham & Women's Hospital, AstraZeneca, NIH/NHLBI, Amorcyte/Neostem, Cytori, InfraReDx, NHLBI/NCRR CTSA grant 1UL1RR029890, AHA; Berman: Spectrum Dynamics, Cedars Sinai Medical Center -software royalties, Lantheus, Siemens, Astellas, GE/Amersham, Cardium Therapeutics Inc; Handberg: Gilead, AstraZeneca, Daiiehi Sankyo, Amarin, Daiichi, Mesoblast, ISIS Pharmaceuticals, EsperionTherapeudics, Vessex, Genentech, Cytori, Daiichi-Sankyo, Medtronic, Baxter, United Therapeudics, Sanofi/Aventis, Amgen, Catabasis; Bairey Merz: Research Triangle Institute International, UCSF, Kaiser, Gilead (grant review committee), Garden State AHA, Allegheny General Hospital, PCNA, Mayo Foundation (lectures; symposiums), Bryn Mawr Hospital, Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute (Australia, Duke (Consulting, Japanese Circ Society , U of New Mexico, Emory, Practice Pont Communications (lectures), Vox Media (lectures), WISE CVD, FAMRI, RWISE, Normal Control, Microvascular, NIH-SEP.

This work was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institutes nos. N01-HV-68161, N01-HV-68162, N01-HV-68163, N01-HV-68164, grants U0164829, U01HL649141, U01 HL649241, K23HL105787, T32HL69751, T32HL116273, R01 HL090957, 1R03AG032631 from the National Institute on Aging, GCRC grant MO1-RR00425 from the National Center for Research Resources, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1TR000124 and UL1TR000064, and grants from the Gustavus and Louis Pfeiffer Research Foundation, Danville, NJ, The Women’s Guild of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, The Ladies Hospital Aid Society of Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, PA, and QMED, Inc., Laurence Harbor, NJ, the Edythe L. Broad and the Constance Austin Women’s Heart Research Fellowships, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, the Barbra Streisand Women’s Cardiovascular Research and Education Program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, The Society for Women’s Health Research (SWHR), Washington, D.C., The Linda Joy Pollin Women’s Heart Health Program, and the Erika Glazer Women’s Heart Health Project, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, the American Heart Association (16SDG27260115) and the Harry S. Moss Heart Trust.

This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or National Institutes of Health

Abbreviations:

- HF

heart failure

- EF

ejection fraction

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- CAD

coronary arterial disease

- CMD

coronary microvascular dysfunction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Farmakis D, Parissis J, Lekakis J, Filippatos G Acute heart failure: Epidemiology, risk factors, and prevention. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition). 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottdiener JS, Arnold AM, Aurigemma GP, Polak JF, Tracy RP, Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Rutledge JE, Boineau RC Predictors of congestive heart failure in the elderly: The cardiovascular health study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000;35:1628–1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam CS, Donal E, Kraigher-Krainer E, Vasan RS Epidemiology and clinical course of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. European journal of heart failure. 2011;13:18–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw LJ, Merz CNB, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kip KE, Kelsey SF, Olson M, Johnson BD, Mankad S The economic burden of angina in women with suspected ischemic heart disease results from the national institutes of health–national heart, lung, and blood institute–sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation. Circulation. 2006;114:894–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merz CNB, Kelsey SF, Pepine CJ, Reichek N, Reis SE, Rogers WJ, Sharaf BL, Sopko G The women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (wise) study: Protocol design, methodology and feasibility report. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999;33:1453–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson BD, Kip KE, Marroquin OC, Ridker PM, Kelsey SF, Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, Sharaf B, Merz CNB, Sopko G Serum amyloid a as a predictor of coronary artery disease and cardiovascular outcome in women the national heart, lung, and blood institute–sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (wise). Circulation. 2004;109:726–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw LJ, Merz CNB, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kelsey SF, Olson M, Johnson BD, Mankad S, Sharaf BL Insights from the nhlbi-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (wise) study: Part i: Gender differences in traditional and novel risk factors, symptom evaluation, and gender-optimized diagnostic strategies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47:S4–S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merz CNB, Shaw LJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kelsey SF, Olson M, Johnson BD, Pepine CJ, Mankad S, Sharaf BL Insights from the nhlbi-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (wise) study: Part ii: Gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47:S21–S29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;62:263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulati M, Cooper-DeHoff RM, McClure C, Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Handberg EM, Zineh I, Kelsey SF, Arnsdorf MF, Black HR Adverse cardiovascular outcomes in women with nonobstructive coronary artery disease: A report from the women's ischemia syndrome evaluation study and the st james women take heart project. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169:843–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharaf BL, Pepine CJ, Kerensky RA, Reis SE, Reichek N, Rogers WJ, Sopko G, Kelsey SF, Holubkov R, Olson M Detailed angiographic analysis of women with suspected ischemic chest pain (pilot phase data from the nhlbi-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation [wise] study angiographic core laboratory). The American journal of cardiology. 2001;87:937–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pepine CJ, Anderson RD, Sharaf BL, Reis SE, Smith KM, Handberg EM, Johnson BD, Sopko G, Merz CNB Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia: Results from the national heart, lung and blood institute wise (women's ischemia syndrome evaluation) study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;55:2825–2832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer S, Brouwers FP, Voors AA, Hillege HL, de Boer RA, Gansevoort RT, van der Harst P, Rienstra M, van Gelder IC, van Veldhuisen DJ Sex differences in new-onset heart failure. Clinical Research in Cardiology. 2014:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merz CNB, Eslick GD, Kaski JC Chest pain with normal coronary arteries: Future directions. Chest pain with normal coronary arteries. Springer; 2013:343–345. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pepine CJ, Petersen JW, Merz CNB A microvascular-myocardial diastolic dysfunctional state and risk for mental stress ischemia: A revised concept of ischemia during daily life*. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2014;7:362–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho JE, Gona P, Pencina MJ, Tu JV, Austin PC, Vasan RS, Kannel WB, D'Agostino RB, Lee DS, Levy D Discriminating clinical features of heart failure with preserved vs. Reduced ejection fraction in the community. European heart journal. 2012;33:1734–1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei J, Mehta PK, Johnson BD, Samuels B, Kar S, Anderson RD, Azarbal B, Petersen J, Sharaf B, Handberg E Safety of coronary reactivity testing in women with no obstructive coronary artery disease: Results from the nhlbi-sponsored wise (women's ischemia syndrome evaluation) study. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2012;5:646–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taqueti VR, Hachamovitch R, Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Hainer J, Dorbala S, Blankstein R, Di Carli MF Global coronary flow reserve is associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of luminal angiographic severity and modifies the effect of early revascularization. Circulation. 2015;131:19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]