Abstract

Background and Objectives: In this paper, we investigated the efficacy of statin therapy on cardiovascular disease (CVD) reduction in adults with no known underlying health conditions by undertaking a meta-analysis and systematic review of the current evidence. Materials and Methods: We performed a systematic search to identify Primary Prevention Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) that compared statins with a control group where CVD events or mortality were the primary end point. Identified RCTs were evaluated and classified into categories depending on relevance in order to determine which type of meta-analysis would be feasible. Results: No differences were observed between categories with the exception of relative risk for all CVD events combined which showed a 12% statistically significant difference favouring studies which were known to include participants without underlying health conditions. Strong negative correlations between number-need-to-treat (NNT) and LDL-C reduction were observed for all Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) outcomes combined and all CVD outcomes combined. Conclusions: This project highlights the need for further research on the effects of statins on participants who do not suffer from underlying health conditions, given that no such studies have been conducted.

Keywords: statins, cardiovascular disease and mortality, cholesterol, primary prevention

1. Introduction

People may be healthy while presenting hypercholesterolemia, and more specifically, increased Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) levels. We do not know what strategy to adopt to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) in these cases. The critical issue for such people is that the standard of care for the management of high LDL-C is statin treatment; a practice which has become increasingly controversial due to side effects [1], claims that they have failed to substantially reduce CVD outcomes [2], statistical misrepresentation of the benefits [2] and financial conflicts of interest as a source of bias [2].

In terms of the evidence, there are hundreds of published randomised-controlled trials (RCTs) and several meta-analyses favouring statins [3,4,5,6]. Despite this, there is scepticism within the scientific community on the efficacy of statins, backed by a large number of scientific studies and publications [7,8,9,10,11]. The question of whether cholesterol plays a causal role in CVD is essential for proposing optimal strategies, not only pharmaceutical, but also dietetic.

The primary focus of the present work will be an investigation into the evidence on the benefits of statins on “otherwise healthy” participants. The justification for this is that the current standard of care for the management of high LDL-C is the ubiquitous prescription of statins, including participants with no underlying health conditions and where high LDL-C is the only exhibited CVD risk marker.

The key outcome of the study will be a review of the evidence on the efficacy of statins in reducing CVD risk in people with no underlying health conditions. We hypothesise that the CVD risk reduction effect size of statins is lower in participants without underlying health conditions compared to those with underlying health conditions.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Protocol

MEDLINE, PubMed (1946–January 2020) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched. Relevant studies were identified by using a combination of MeSH terms, text words and search equations focussing on the following terms: statins, cardiovascular disease and mortality, cholesterol, primary prevention and randomised controlled trials. All RCTs, reviews and references were examined to identify studies potentially eligible for inclusion.

2.2. Study Selection

We shortlisted studies for further investigation if they met the following criteria:

Primary prevention;

Placebo-based statins RCT;

Mean follow-up of at least one year;

Reported all-cause mortality (ACM), Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) or CVD events as primary, secondary or tertiary outcomes;

Reported on known CVD risk confounding factors, such as LDL-C, age, sex, T2DM status, hypertension status and smoking status.

We designed a structured data abstraction form which included a comprehensive list of data points, and each study was categorised according to relevance (see Table 1). Titles and abstracts of all potentially eligible studies were then read in order to classify studies and where required papers were read in full. We also extracted information and assessed study quality using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.

Table 1.

Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) classification matrix.

| Category | Description | Meta-Analysis Feasibility |

|---|---|---|

| Not relevant | Not an RCT, not statins versus control, secondary prevention | Not feasible |

| Category 1 | Specifically studied participants with no underlying health conditions other than dyslipidaemia or hypercholesterolemia | Standard aggregate meta-analysis |

| Category 2 | Included a significant percentage of participants without underlying health conditions | Sub-group meta-analysis |

| Category 3 | Met all study eligibility criteria except that the specific focus was on participants with one or more underlying health conditions | Other statistical analyses |

2.3. Study Categorisation

All studies were evaluated to determine the type of outcome and population under investigation. Secondary prevention studies were not evaluated and categorised as they were not relevant to the research question. Primary prevention studies were classified into three categories as described in Table 1 with the objective of determining which type of meta-analysis would be feasible.

2.4. Meta-Analysis

No Category 1 studies were found, meaning a standard aggregate meta-analysis was not feasible. Several Category 2 studies were found; however, although all studies reported sub-group data, none were sufficiently reported to enable a meta-analysis on the sub-group relevant to the present study. For example, studies may report sub-group data for “no hypertension”, however, within those sub-group data, participants may be included with other underlying health conditions, such as T2DM. This finding meant that a standard aggregate meta-analysis was not feasible.

2.5. Secondary Statistical Analysis and Meta-Regression Analysis

Given that meta-analyses were not possible, we decided to undertake a statistical analysis on two further levels. First, we compared the pooled results from the Category 2 and 3 studies to determine whether there was any difference between the two groups for the three outcomes below. Second, we conducted a meta-regression analysis to examine the relationships between number-needed-to-treat (NNT) and various confounding factors.

2.6. Outcomes

We performed a statistical analysis on the following three outcomes:

Primary outcome: all-cause mortality;

Secondary outcome: all CHD events combined;

Tertiary outcome: all CVD events combined.

Some aggregation was required to determine the secondary and tertiary outcomes:

- Secondary outcome: All CHD events combined

-

−Non-fatal or fatal MI

-

−Death from coronary causes

-

−Cardiac sudden death

-

−Resuscitated cardiac arrest

-

−Heart failure

-

−Coronary angiography

-

−Coronary artery bypass graft

-

−Peripheral arterial surgery/angioplasty

-

−Transient ischaemic attack

-

−Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) or Coronary artery bypass grafting/Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CABG/PCI)

-

−Revascularizations

-

−Angina: unstable, stable or angina with evidence of ischemia

-

−Interventional procedure

-

−

- Tertiary outcome: All coronary and cardiovascular events combined

-

−All secondary outcome events +

-

−Fatal or nor fatal stroke

-

−Death from cardiovascular causes

-

−

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

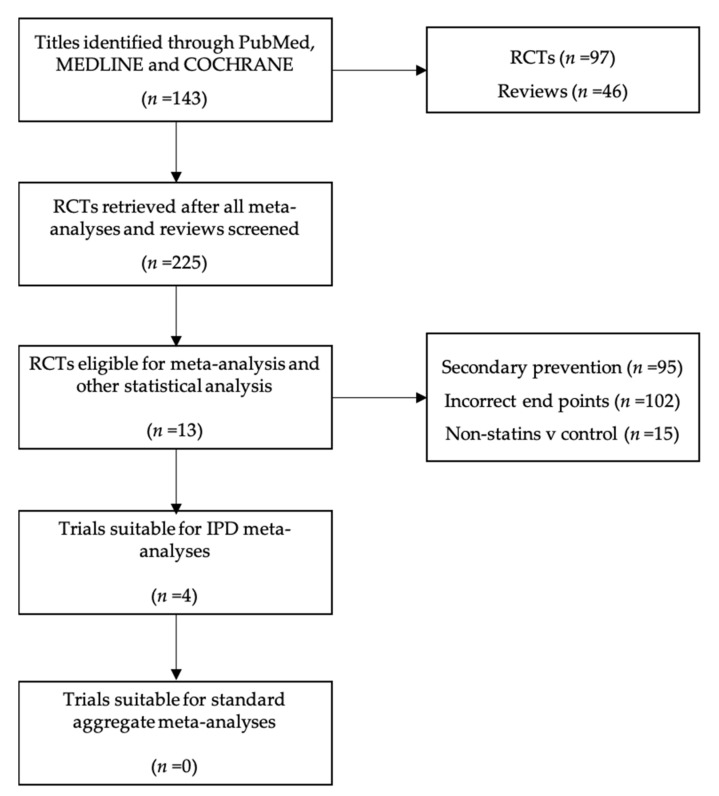

The search protocol identified a total of 143 relevant studies, with 97 RCTs and 46 reviews found. From the RCTs identified, 74 were disregarded as ineligible following a review of titles and abstracts, and 12 were duplicates. As such, 11 RCTs were deemed eligible for further, more comprehensive evaluation. A further 202 studies were found through a manual read-through of study references, reviews and meta-analyses. See Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 for further details. Figure 1 shows the logical flow used to classify RCTs identified through the search protocol.

Table 2.

Summary of search results.

| Database | Study Design | Studies Retrieved | Category 2 | Category 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE | Randomised Controlled Trial | 22 | 3 | 3 |

| PubMed | Randomised Controlled Trial | 75 | 3 | 2 |

| MEDLINE | Meta-analysis | 30 | - | - |

| PubMed | Meta-analysis | 11 | - | - |

| Cochrane | Meta-analysis | 5 | - | - |

| RCTs retrieved from search protocol for further evaluation | 23 | |||

| Incremental RCTs retrieved from manual read of all reviews | 202 | |||

| Total RCTs retrieved for further evaluation | 225 | |||

Table 3.

Summary of studies retrieved split by primary prevention, secondary prevention and categorised by exclusion category and population. Category 1—100% without underlying health conditions or reported in sub-groups; Category 2—A percentage of participants included without underlying health conditions; Category 3—Underlying health conditions in 100% of participants. † May include some studies which were mixed primary and secondary; such studies were categorised as primary prevention. ± CIMT, IMT, CAC, Calcium Volume Score, Atherosclerosis progression.

| Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of RCTs retrieved | 225 | - |

| Primary prevention † | 130 | 58% |

| Secondary Prevention | 95 | 42% |

| RCTs eligible for meta-analysis and other statistical analysis | 13 | 10% |

| Category 1 | 0 | 0% |

| Category 2 | 4 | 31% |

| Category 3 | 9 | 69% |

| Primary studies by exclusion category | 117 | 90% |

| Not statins v control | 15 | 13% |

| Incorrect outcome | 102 | 87% |

| Cholesterol levels | 74 | 63% |

| Atherosclerosis markers ± | 11 | 9% |

| Blood Pressure | 4 | 3% |

| Other biomarkers | 3 | 3% |

| CRP | 2 | 2% |

| QUALY | 1 | 1% |

| Bone mineral density | 1 | 1% |

| Ischemic episodes | 1 | 1% |

| Arterial inflammation | 1 | 1% |

| Erectile function | 1 | 1% |

| serum adiponectin levels | 1 | 1% |

| Ventricular Diastolic Function | 1 | 1% |

| Diabetic macular edema. | 1 | 1% |

Table 4.

Category 1, 2 & 3 studies by health condition studied.

| Health Condition Studied | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| None | 4 | 31% |

| T2DM | 3 | 23% |

| Hypertension | 2 | 15% |

| Kidney disease | 2 | 15% |

| Multiple comorbidities | 1 | 8% |

| Inflammation | 1 | 8% |

Table 5.

All primary studies by health condition studied.

| Health Condition Studied | 130 | Pct |

|---|---|---|

| Hypercholesterolemia/Dyslipidemia | 60 | 46% |

| T2DM | 11 | 8% |

| Hypercholesterolemia/Dyslipidemia + another condition | 7 | 5% |

| Multiple comorbidities | 7 | 5% |

| Hypertension | 6 | 5% |

| Hypertension and dyslipidemia | 6 | 5% |

| None | 4 | 3% |

| Diabetes | 3 | 2% |

| High CHD risk | 3 | 2% |

| Metabolic Syndrome | 3 | 2% |

| kidney disease | 2 | 2% |

| Stroke | 2 | 2% |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome | 1 | 1% |

| Arterial hypertension | 1 | 1% |

| Atherosclerotic progression | 1 | 1% |

| Bone mineral density | 1 | 1% |

| CAPD | 1 | 1% |

| Diabetic macular edema | 1 | 1% |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 1 | 1% |

| Familial Hypercholesterolemia | 1 | 1% |

| HIV | 1 | 1% |

| Inflammation | 1 | 1% |

| Microalbuminuria | 1 | 1% |

| Obesity | 1 | 1% |

| Refractory Nephrotic Syndrome | 1 | 1% |

| Stable angina pectoris. | 1 | 1% |

| Statins users | 1 | 1% |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | 1 | 1% |

Figure 1.

Trial workflow.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table 6 lists the RCTs included in the meta-analysis and further statistical analysis. This table includes relevant information pertaining to each study, including the type of statins studied, year of publication, mean follow-up and the number of participants included. In addition, this table includes data on potential confounding variables, such as average age, BMI, LDL-C at baseline, % LDL-C change, and smoking status as the percentage of participants with underlying health conditions, namely, hypertension and T2DM.

Table 6.

Study characteristics.

| WOSCOPS | AFCAPS | MEGA | HOPE-3 | 4D | ASPEN | CARDS | ASCOT-LLA | ALLHAT-LLT | PROSPER | AURORA | ALERT | JUPITER | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1995 | 1998 | 2006 | 2016 | 2005 | 2006 | 2004 | 2002 | 2002 | 2002 | 2005 | 2005 | 2008 |

| Statin | Pravastatin | Lovastatin | Pravastatin | Rosuvastatin | Atorvastatin | Atorvastatin | Atorvastatin | Atorvastatin | Pravastatin | Pravastatin | Rosuvastatin | Fluvastatin | Rosuvastatin |

| Number of participants | 6595 | 6605 | 7852 | 12705 | 1255 | 1905 | 2838 | 10305 | 10355 | 5804 | 2773 | 1652 | 17802 |

| Health condition(S) studied | None | None | None | None | T2DM | T2DM | T2DM | Hypertention | Hypertention | Multiple | Kidney disease | Kidney disease | Inflammation |

| Category of study | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Men (%) | 100% | 85% | 32% | 54% | 54% | 62% | 68% | 81% | 51% | 48% | 38% | 66% | 62% |

| Mean age at baseline (years) | 55.2 | 58.0 | 58.3 | 65.8 | 65.7 | 60.5 | 61.6 | 63.1 | 66.3 | 75.3 | 64.2 | 48.5 | 66.0 |

| Mean follow up (years) | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 3.93 | 4 | 3.95 | 3.3 | 4.8 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 6.7 | 1.9 |

| Mean BMI at baseline | 26.0 | 27.1 | 23.8 | 27.1 | 27.5 | 28.9 | 28.7 | 28.6 | 29.9 | 26.8 | 25.4 | 26.0 | 28.4 |

| LDL status | |||||||||||||

| Baseline (mg/dl) | 192 | 150 | 157 | 128 | 126 | 114 | 117 | 132 | 148 | 147 | 100 | 160 | 108 |

| % reduction | 26% | 27% | 15% | 26% | 38% | 30% | 33% | 28% | 17% | 31% | 41% | 32% | 50% |

| Reduction in mg/dl | 50 | 40 | 23 | 34 | 47 | 34 | 38 | 37 | 25 | 46 | 41 | 51 | 54 |

| Reduction in mmol/l | 1.29 | 1.03 | 0.60 | 0.88 | 1.23 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.65 | 1.19 | 1.06 | 1.31 | 1.40 |

| Smoking status | |||||||||||||

| Never smoked (%) | 22% | NR | 79% | 72% | 60% | NR | 35% | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Past smoked (%) | 34% | NR | NR | NR | 32% | NR | 43% | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Current smoker (%) | 44% | 12% | 21% | 28% | 9% | 13% | 22% | 33% | 23% | 27% | 15% | 17% | 16% |

| Hypertention (%) | 16% | 22% | 42% | 38% | NR | 52% | 84% | 100% | 100% | 62% | 33% | 75% | 57% |

| Diabetes (%) | 1% | 4% | 21% | 6% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 25% | 35% | 11% | 26% | 17% | TBC |

NR—Not reported.

3.3. Meta-Analyses Comparing Category 2 and 3 Studies

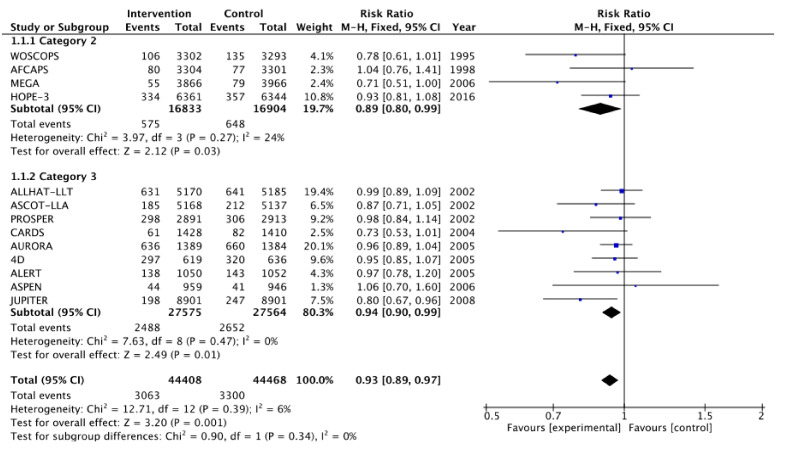

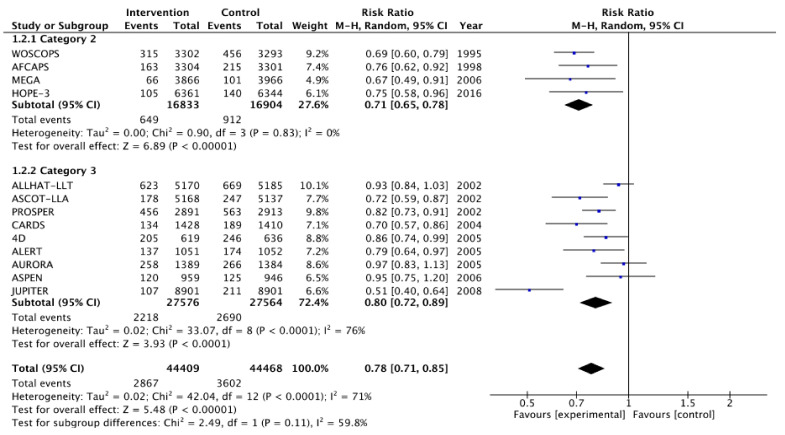

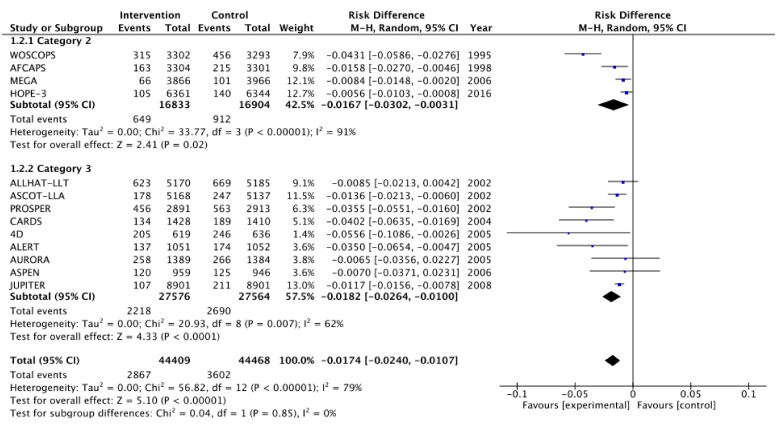

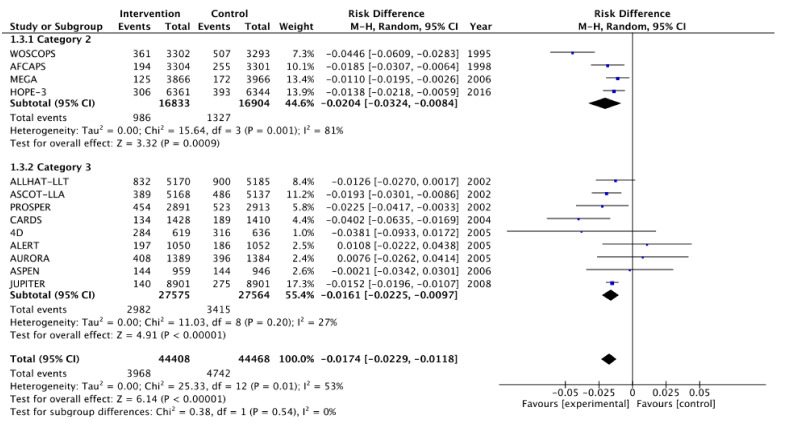

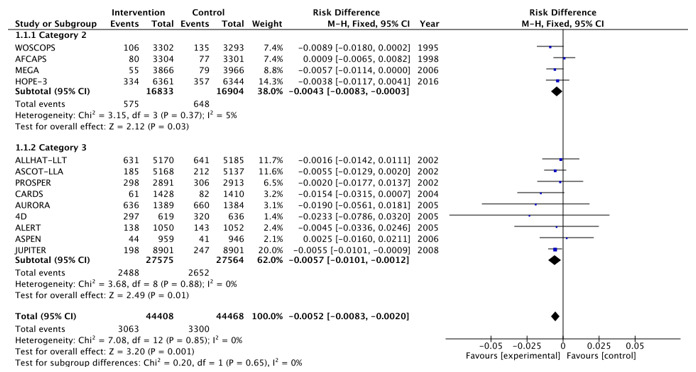

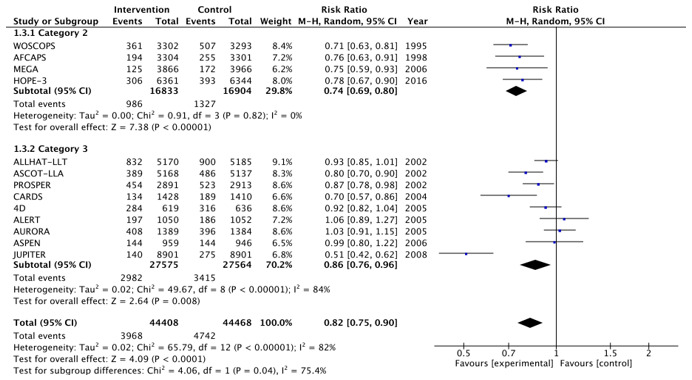

Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show relative risk ratios and absolute risk differences across Category 2 and 3 studies for the primary, secondary and tertiary outcomes. Stain therapy favoured control in both categories of study in terms of relative risk and risk difference for all outcomes (See Table 7 for effect sizes and statistical significance). No differences were observed between Category 2 and 3 studies with the exception of relative risk for all CVD events combined, which showed a 12% statistically significant difference favouring Category 2 studies, X2 (1, N = 88,877) = 4.06, p < 0.05 (Table 7, Figure 6).

Figure 2.

Relative risk across Category 2 and 3 studies for the primary outcome of all-cause mortality. Heterogeneity across studies was low, so fixed effects were used for the meta-analysis (Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 12.71, p = 0.39, I2 = 6%).

Figure 3.

Risk difference across Category 2 and 3 studies for the primary outcome of all-cause mortality. Heterogeneity across studies was low, so fixed effects were used for the meta-analysis (Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 7.08, p = 0.85, I2 = 0%).

Figure 4.

Relative risk across Category 2 and 3 studies for the secondary outcome of all CHD events combined. Heterogeneity across studies was high, so random effects were sed for the meta-analysis (Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 42.04, p < 0.001, I2 = 71%).

Figure 5.

Risk difference across Category 2 and 3 studies for the secondary outcome of all CHD events combined. Heterogeneity across studies was high, so random effects were used for the meta-analysis (Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 56.82, p < 0.001, I2 = 79%).

Figure 6.

Relative risk across Category 2 and 3 studies for the tertiary outcome of all CVD events combined. Heterogeneity across studies was high, so random effects were used for the meta-analysis (Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 65.79, p < 0.001, I2 = 82%).

Figure 7.

Risk difference across Category 2 and 3 studies for the tertiary outcome of all CVD events combined. Heterogeneity across studies was high, so random effects were used for the meta-analysis (Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 25.33, p < 0.05, I2 = 53%).

Table 7.

Relative Risk Reduction (RRD), Absolute Risk Difference (ARD) and Number Needed to Treat (NNT)/year in the trials for all of the present study’s outcomes. * Significant to p ≤ 0.05; ** significant to p ≥ 0.01.

| All-Cause Mortality | All CHD Events Combined | All CVD Events Combined | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | % RRR | %ARD | NNT/year | % RRR | %ARD | NNT/year | % RRR | %ARD | NNT/year |

| WOSCOPS [12] | 22% * | 0.89% | 551 | 31% * | 4.31% ** | 114 | 29% | 4.46% ** | 110 |

| AFCAPS [13] | −4% | −0.09% | −5864 | 24% | 1.58% ** | 329 | 24% | 1.85% ** | 281 |

| MEGA [14] | 29% | 0.57% | 931 | 33% | 0.84% | 631 | 25% | 1.10% ** | 480 |

| HOPE-3 [15] | 7% | 0.38% | 1487 | 25% | 0.56% | 1007 | 22% | 1.38% ** | 405 |

| 4D [16] | 5% | 2.33% | 168 | 7% ** | 0.85% ** | 71 | 7% | 1.26% | 103 |

| ASPEN [17] | −3% | 0.45% | −1574 | 28% | 1.36% ** | 571 | 20% | 1.93% ** | 1938 |

| CARDS [18] | 1% | 0.16% | 256 | 18% | 3.55% | 209 | 13% | 2.25% * | 98 |

| ASCOT-LLA [19] | 13% | 0.55% | 603 | 30% | 1.89% | 242 | 30% | 4.02% ** | 171 |

| ALLHAT-LLT [20] | −6% | −0.25% | 3047 | 14% | 5.56% | 563 | 8% | 3.81% | 379 |

| PROSPER [21] | 4% | 1.90% | 1626 | 21% | 3.50% | 90 | 13% | −1.08% | 142 |

| AURORA [22] | 27% | 1.54% | 200 | 3% * | 0.65% | 589 | −3% | −0.76% | −499 |

| ALERT [23] | 20% | 0.55% | 1133 | 5% | 0.70% ** | 146 | 1% | 0.21% | −472 |

| JUPITER [24] | 2% * | 0.20% | 345 | 49% | 1.17% ** | 163 | 49% | 1.52% ** | 125 |

| CAT 2 POOLED | 11% * | 0.43% ** | 233 | 29% ** | 1.67% ** | 60 | 26% ** | 2.04% ** | 49 |

| CAT 3 POOLED | 6% ** | 0.60% * | 167 | 20% ** | 1.82% ** | 55 | 14% ** | 1.61% ** | 62 |

3.4. Meta-Regression Analysis

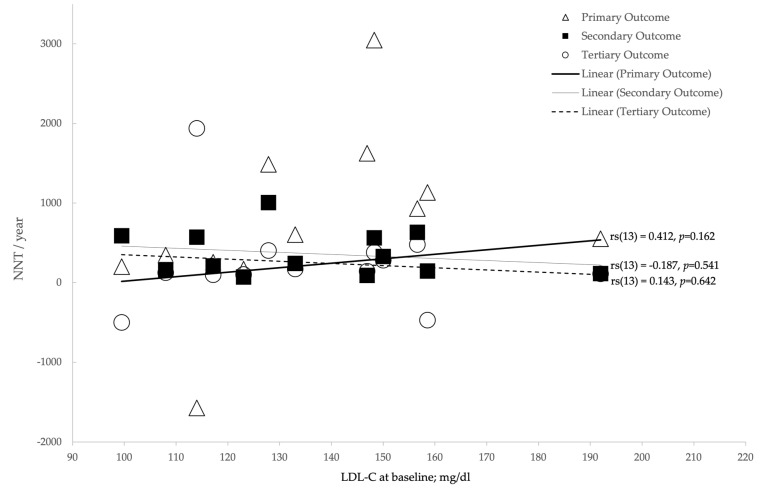

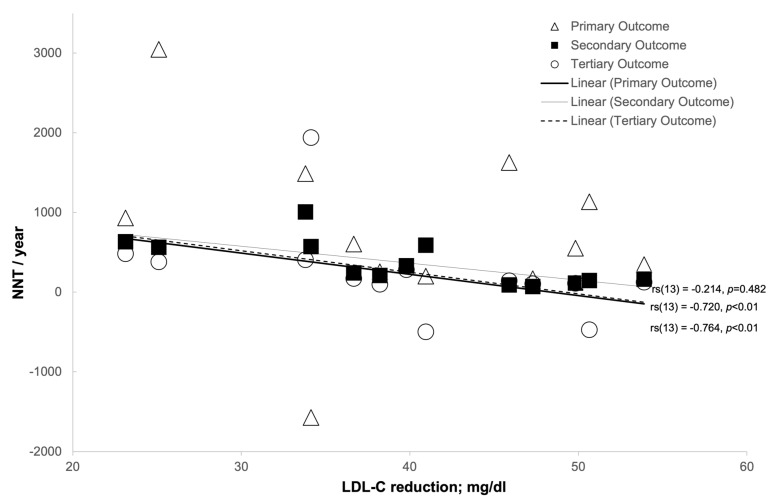

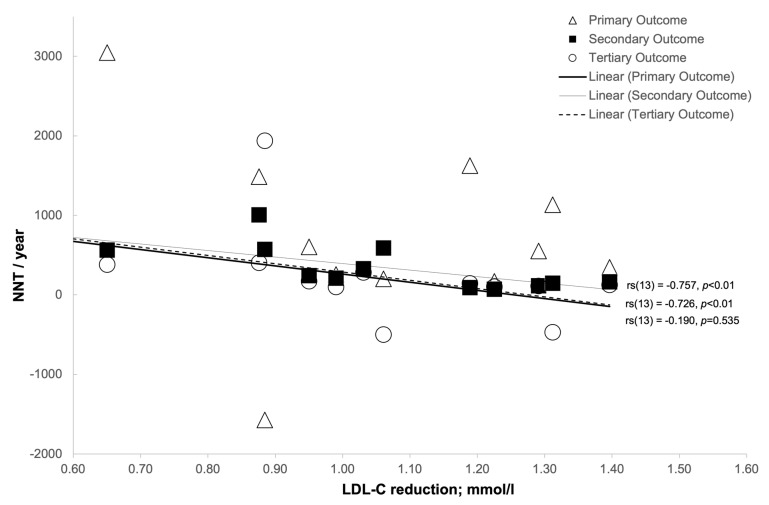

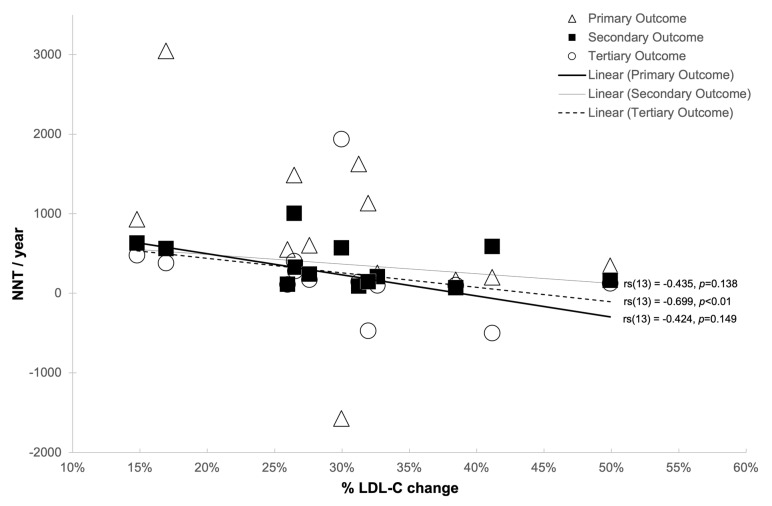

Analysis was undertaken to examine the relationship between NNT and various confounding factors (Table 8). In order to achieve this, Spearman’s rank-order correlation was used, the results of which can be seen in Table 8 and in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Table 8.

Meta-regression analysis showing the relationships between NNT/year and confounding factors.

| Mean Age at Baseline | Mean BMI at Baseline | Mean LDL-C at Baseline | Mean LDL-C Change (mg/dL) | Mean LDL-C Change (mmol/L) | Mean LDL-C Change (%) | Pct Male | Pct Smokers | Pct with Hypertension | Pct with Diabetes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NNT Primary Outcome | Correlation Coefficient | 0.379 | −0.071 | 0.412088 | −0.214 | −0.190 | −0.424 | −0.353 | 0.703 ** | 0.452 | −0.232 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.201 | 0.817 | 0.162 | 0.482 | 0.535 | 0.149 | 0.237 | 0.007 | 0.140 | 0.467 | |

| N | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 | |

| NNT Secondary Outcome | Correlation Coefficient | −0.022 | −0.022 | −0.186813 | −0.764 ** | −0.757 ** | −0.435 | −0.361 | 0.011 | −0.210 | −0.007 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.943 | 0.943 | 0.541 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.138 | 0.226 | 0.972 | 0.512 | 0.983 | |

| N | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 | |

| NNT Tertiary Outcome | Correlation Coefficient | 0.110 | 0.297 | 0.142857 | −0.720 ** | −0.726 ** | −0.699 ** | −0.163 | 0.110 | −0.014 | −0.063 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.721 | 0.325 | 0.642 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.596 | 0.721 | 0.966 | 0.845 | |

| N | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Figure 8.

The relationship between LDL-C at baseline (mg/dL) and number-needed-to-treat (NNT)/year.

Figure 9.

The relationship between LDL-C reduction (mg/dL) and number-needed-to-treat (NNT)/year.

Figure 10.

The relationship between LDL-C reduction (mmol/L) and number-needed-to-treat (NNT)/year.

Figure 11.

The relationship between LDL-C reduction % and number-needed-to-treat (NNT)/year.

3.5. Primary Outcome

In terms of the primary outcome of all-cause mortality, no statistically significant correlations were observed between NNT and any LDL-C metrics (Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11). There was a strong positive correlation between the percentage of smokers and NNT per year with regard to all-cause mortality (rs(13) = 0.703, p < 0.01) [Table 8].

3.6. Secondary Outcome

There was a strong negative correlation between the NNT per year for the secondary outcome of all CHD events combined and mean LDL-C reduction (mg/dL: rs(13) = 0.764, p < 0.01; mmol/L: rs(13) = 0.757, p < 0.01) [Figure 9 and Figure 10, respectively].

3.7. Tertiary Outcome

There was a strong negative correlation between the NNT tertiary outcome per year of all CVD events combined and the mean LDL-C reduction (mg/dL: rs(13) = 0.720, p < 0.01; mmol/L: rs(13) = 0.726, p < 0.01) and mean LDL-C % reduction (rs(13) = 0.699, p < 0.01) [Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, respectively].

4. Discussion

Through a meta-analysis of primary prevention studies, this study is not able to confirm any difference in statins efficacy between RCTs which included participants with and without underlying health conditions. This was with the exception of a 12% relative risk difference in the tertiary outcome of all CVD events combined favouring studies with the highest number of “otherwise healthy” participants. Should our hypothesis be true, we may have expected to see reduced efficacy in Category 2 studies, given that they did not primarily focus on participants with underlying health conditions. However, it is extremely difficult to draw conclusions from this result given that the percentage of “otherwise healthy” participants in each study is unknown and all studies included a significant percentage of participants exhibiting known heart disease risk factors. For example, 44% of participants in the WOSCOPS trial were smokers, and only 22% were reported as never having been smokers [12]. Similarly, 38% of HOPE-3 participants were reported as being hypertensive [15], and 21% of participants in MEGA were reported as having T2DM [14].

Meta-regression analysis showed an absence of an association between LDL-C reduction and NNT for the primary outcome of all-cause mortality. However, statistically significant negative associations between LDL-C reduction and NNT in the secondary and tertiary outcomes support a number of other meta-analyses that suggest that lowering LDL-C has a positive effect on reducing the risk of CHD and CVD events [3,4,5,25,26,27]. Correlation, however, does not prove causation, so such associations should be interpreted with significant caution. This is particularly pertinent to the results of statins trials, given the complexity associated with heart disease and the constantly evolving science. Central to this evolution is the emerging theory that LDL-C in its own right may not be as significant in the heart disease story as previously thought. For example, a wide range of potential heart disease risk markers are now considered to be more important than LDL-C, such as inflammation [28,29,30,31], LDL particle size [32,33,34], Apolipoprotein B [35] and LDL particle number [36], Lipoprotein(a) [37], lipoprotein ratios [38] and the ratio between triglycerides and HDL [39]. Inflammation specifically needs a special mention, as it has been the cause of much controversy in statins trials. For example, JUPITER reported statins as deriving a 20% RRD in all-cause mortality and almost 50% RRD in heart attacks and strokes. However, although an association with CRP reduction was shown, an important inflammation marker, no association was observed for LDL-C [31].

Conversely, it cannot be neglected that both naturally randomized genetic studies and randomized intervention trials have consistently shown that lowering plasma LDL particle concentration should reduce the risk of CVD events. This suggests that, through different approaches, LDL reduction lowers CVD risk, even though the effect of LDL increase has not been formally tested [25,26,27].

Our research contributes to the evidence that the results from statins trials may have been misrepresented. Most trials report either relative risk or hazard ratios and conclude that statins have significantly positive effects on CVD outcomes. However, although relative risk is one of a number of appropriate ways to present results, it can result in an overestimation of effect size, given that the underlying absolute risk is concealed [40]. JUPITER, for instance, reported that “rosuvastatin significantly reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events”. As a specific example, the hazard ratio reported for myocardial infarction (MI) was 0.46, which could be interpreted as rosuvastatin reducing heart attacks by 54% compared to the control. This was based on 31 and 68 MIs in the intervention and control groups, respectively, unquestionably showing more than double the number of MIs in the control group.

However, in terms of absolute risk, the difference between groups was only 0.42%, given the large sample size of almost 9000 in each study arm. Thus, whilst the study authors are technically accurate in reporting a significant difference between groups, the hazard ratio is potentially misleading without the context of absolute risk. In real-world terms, only 0.35% and 0.76% of participants suffered myocardial infarctions in the rosuvastatin and control groups, respectively, which is a miniscule effect size compared to that presented through a hazard ratio. In another example, HOPE-3 reported “a significant reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events with the use of rosuvastatin”. This was on the back of a hazard ratio of 0.76 for the coprimary outcome of a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke. The absolute risk difference for the same endpoint was 1.10%, deriving an NNT of 91. This common method of reporting has been highlighted in many critiques of statins trials, and is one of the factors which compounds statin scepticism [2,41,42,43,44].

This type of selective reporting may, in fact, be at least partially attributed to bias. Although all studies were found to be at low risk of bias after assessment using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool, it must be acknowledged that there may be a risk of bias given that the majority of studies were funded by the pharmaceutical companies manufacturing the drugs under examination [45,46].

In conclusion, the efficacy of statins in reducing CVD risk in people with no underlying health conditions cannot be directly quantified. Our study has highlighted a significant gap in the literature regarding the efficacy of statins therapy on healthy adults with no underlying health conditions. It appears that the majority of RCTs conducted to date have focussed on participants exhibiting multiple heart disease risk factors, such as smoking, hypertension, obesity and diabetes. Although the majority of these studies paved the way for the current guidelines on statins therapy, none seem to have adequately isolated LDL-C as a standalone risk factor. From the studies that we identified as potentially having included a significant percentage of participants without underlying health conditions, none adequately reported this cohort in sub-group analyses to enable the present study to execute the intended aggregate meta-analysis. Given the evolving research on the relationship between LDL-C and heart disease risk, a review of the current guidelines is highly recommended. Statins clearly demonstrate benefits in terms of reducing CVD risk, that is, when the cardiovascular risk is high as a whole, but whether this is due to LDL reduction, or whether the statins are acting on other heart disease risk factors is not sufficiently understood.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author Contributions

L.S. designed the study under the supervision of P.F., collected the data, did the analyses and interpreted these with P.F., drafted the text which was reviewed by P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are included in the article.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Golomb B.A., Evans M.A. Statin adverse effects: A review of the literature and evidence for a mitochondrial mechanism. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs. 2008;8:373–418. doi: 10.2165/0129784-200808060-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamond D.M., Ravnskov U. How statistical deception created the appearance that statins are safe and effective in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014;8:201–210. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2015.1012494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung B.M.Y., Lauder I.J., Lau C.-P., Kumana C.R. Meta-analysis of large randomized controlled trials to evaluate the impact of statins on cardiovascular outcomes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004;57:640–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2003.02060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baigent C., Keech A., Kearney P.M., Blackwell L., Buck G., Pollicino C., Kirby A., Sourjina T., Peto R., Collins R., et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: Prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 partic-ipants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugts J.J., Yetgin T., Hoeks S.E., Gotto A.M., Shepherd J., Westendorp R.G.J., de Craen A.J.M., Knopp R.H., Nakamura H., Ridker P., et al. The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;339:36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2009;302:1993–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravnskov U. A hypothesis out-of-date: The diet-heart idea. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2002;55:1057–1063. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinckney E.R., Pinckney C. The Cholesterol Controversy. Sherbourne Press; Los Angeles, CA, USA: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith R.L. The Cholesterol Conspiracy. Warren, H. Green; St. Louis, MO, USA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendrick M. The Great Cholesterol Con: The Truth About What Really Causes Heart Disease and How to Avoid It. John Blake; London, UK: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosch P.J., Harcombe Z., Kendrick M., Ravnskov U., Kummerow F.A., Okuyama H., Langsjoen P.H., Langsjoen A.M., Ohara N., Diamond D.M. Fat and Cholesterol Don’t Cause Heart Attacks and Statins Are Not the Solution. Columbus Publishing; Cwmbran, UK: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul M., Ridker M.D., Eleanor Danielson M.I.A., Francisco A.H., Fonseca M.D., Jacques Genest M.D., Antonio M., Gotto M.D., Jr., John J.P., Kastelein M.D., et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. Atheroscler. Suppl. 2004;5:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downs J.R., Clearfield M., Weis S., Whitney E., Shapiro D.R., Beere P.A., Langendorfer A., Stein E.A., Kruyer W., Gotto A.M., Jr., et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: Results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1998;279:1615–1622. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura H., Arakawa K., Itakura H., Kitabatake A., Goto Y., Toyota T., Nakaya N., Nishimoto S., Muranaka M., Yamamoto A., et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with pravastatin in Japan (MEGA Study): A prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yusuf S., Lonn E., Pais P., Bosch J., López-Jaramillo P., Zhu J., Xavier D., Avezum A., Leiter L.A., Piegas L.S., et al. Cholesterol lowering in intermediate-risk persons without car-diovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:2021–2031. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanner C., Krane V., März W., Olschewski M., Mann J.F., Ruf G., Ritz E. Atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus undergoing dialysis (2) (multiple letters) N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1858–1860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knopp R.H., d’Emden M., Smilde J.G., Pocock S.J., On behalf of the ASPEN Study Group Efficacy and Safety of Atorvastatin in the Prevention of Cardiovascular End Points in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes: The Atorvastatin Study for Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease Endpoints in Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus (ASPEN) Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1478–1485. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colhoun H.M., Betteridge D.J., Durrington P.N., Hitman G.A., Neil H.A., Livingstone S.J., Thomason M.J., Mackness M.I., Charlton-Menys V., Fuller J.H., et al. Primary prevention of cardio-vascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): Multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:685–696. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sever P.S., Dahlof B., Poulter N.R., Wedel H., Beevers G., Caulfield M., Collins R., Kjeldsen S.E., Kristinsson A., McInnes G.T., et al. Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial—Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Drugs. 2004;64(Suppl. S2):43–60. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464002-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trial H.A. Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs usual care. [(accessed on 13 June 2020)];JAMA. 2002 288:2998–3007. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2998. Available online: http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/288/23/2998.short. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shepherd J., Blauw G.J., Murphy M., Bollen E.L., Buckley B.M., Cobbe S.M., Ford I., Gaw A., Hyland M., Jukema J.W., et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1623–1630. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11600-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fellstrom B.C., Jardine A.G., Schmieder R.E., Holdaas H., Bannister K., Beutler J., Chae D.-W., Chevaile A., Cobbe S.M., Grönhagen-Riska C., et al. Rosuvastatin and Cardiovascular Events in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:1450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holdaas H., Fellström B., Jardine A.G., Holme I., Nyberg G., Fauchald P., Grönhagen-Riska C., Madsen S., Neumayer H.H., Cole E., et al. Effect of fluvastatin on cardiac outcomes in renal transplant recipients: A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2024–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridker P.M., Danielson E., Fonseca F.A., Genest J., Gotto A.M., Jr., Kastelein J.J., Koenig W., Libby P., Lorenzatti A.J., MacFadyen J.G., et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:2195–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins R., Reith C., Emberson J., Armitage J., Baigent C., Blackwell L., Blumenthal R., Danesh J., Smith G.D., de Mets D., et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388:2532–2561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman M.G., Ference B.A., Im K., Wiviott S.D., Giugliano R.P., Grundy S.M., Braunwald E., Sabatine M.S. Association between lowering LDL-C and cardiovascular risk reduction among different therapeutic interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. [(accessed on 28 June 2020)];JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016 316:1289–1297. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13985. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ference B.A., Ginsberg H.N., Graham I., Ray K.K., Packard C.J., Bruckert E., Hegele R.A., Krauss R.M., Raal F.J., Schunkert H., et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur. Heart J. 2017;38:2459–2472. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez-Candales A., Hernández-Burgos P.M., Hernandez-Suarez D.F., Harris D. Linking Chronic Inflammation with Cardio-vascular Disease: From Normal Aging to the Metabolic Syndrome. [(accessed on 5 July 2020)];J. Nat. Sci. 2017 3:70–78. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28670620. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welsh P., Grassia G., Botha S., Sattar N., Maffia P. Targeting inflammation to reduce cardiovascular disease risk: A realistic clinical prospect? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017;174:3898–3913. doi: 10.1111/bph.13818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willerson J.T., Ridker P.M. Inflammation as a cardiovascular risk factor. [(accessed on 5 July 2020)];Circulation. 2004 109:II2–II10. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129535.04194.38. Available online: http://www.circulationaha.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridker P.M. Moving beyond JUPITER: Will inhibiting inflammation reduce vascular event rates? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2012;15:295. doi: 10.1007/s11883-012-0295-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivanova E.A., Myasoedova V.A., Melnichenko A.A., Grechko A.V., Orekhov A.N. Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein as Bi-omarker for Atherosclerotic Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1273042. doi: 10.1155/2017/1273042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rizzo M., Berneis K. Low-density lipoprotein size and cardiovascular risk assessment. [(accessed on 4 July 2020)];QJM. 2006 99:1–14. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci154. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/qjmed/article-abstract/99/1/1/1523832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Packard C.J. Small dense low-density lipoprotein and its role as an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease. [(accessed on 28 June 2020)];Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2006 17:412–417. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000236367.42755.c1. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16832165/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryoo J.-H., Ha E.-H., Kim S.-G., Ryu S., Lee D.-W. Apolipoprotein B is Highly Associated with the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease as Estimated by the Framingham Risk Score in Healthy Korean Men. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2011;26:631–636. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.5.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cromwell W.C., Otvos J.D., Keyes M.J., Pencina M.J., Sullivan L., Vasan R.S., Wilson P.W., d’Agostino R.B. LDL particle number and risk of future cardio-vascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Study-Implications for LDL management. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2007;1:583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malaguarnera M., Vacante M., Russo C., Malaguarnera G., Antic T., Malaguarnera L., Bella R., Pennisi G., Galvano F., Frigiola A. Lipoprotein(a) in Cardiovascular Diseases. BioMed Res. Int. 2012;2013:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/650989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Millán J., Pintó X., Muñoz A., Zúñiga M., Rubiés-Prat J., Pallardo L.F., Masana L., Mangas A., Hernández-Mijares A., González-Santos P., et al. Vascular Health and Risk Management Lipoprotein ratios: Physiological significance and clinical usefulness in cardiovascular prevention. [(accessed on 8 April 2019)];Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2009 5:757–765. Available online: www.dovepress.com. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Da Luz P.L., Favarato D., Faria-Neto J.R., Lemos P., Chagas A.C.P. High ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol predicts extensive coronary disease. Clinics. 2008;63:427–432. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322008000400003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noordzij M., van Diepen M., Caskey F.C., Jager K.J. Relative risk versus absolute risk: One cannot be interpreted without the other. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017;32:ii13–ii18. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ravnskov U., de Lorgeril M., Diamond D.M., Hama R., Hamazaki T., Hammarskjöld B., Hynes N., Kendrick M., Langsjoen P.H., Mascitelli L., et al. LDL-C does not cause cardiovascular disease: A comprehensive review of the current literature. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018;11:959–970. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2018.1519391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curtiss F.R., Fairman K.A. Tough Questions About the Value of Statin Therapy for Primary Prevention: Did JUPITER Miss the Moon? J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2010;16:417–423. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.6.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bajpai A., Goyal A., Sperling L. Should We Measure C-reactive Protein on Earth or Just on JUPITER? Clin. Cardiol. 2010;33:190–198. doi: 10.1002/clc.20681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.López A., Wright J.M. Rosuvastatin and the JUPITER trial: Critical appraisal of a lifeless planet in the galaxy of primary pre-vention. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health. 2012;18:70–78. doi: 10.1179/1077352512Z.0000000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lundh A., Lexchin J., Mintzes B., Schroll J.B., Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. [(accessed on 13 September 2019)];Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017 2:MR000033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3. Available online: www.cochranelibrary.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grammer T., Maerz W. Are statins really useless in “primary prevention”? Recent Cochrane meta-analysis revisited. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;49:293–296. doi: 10.5414/CPP49293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are included in the article.