Abstract

The importance of posttranslational glycosylation in protein structure and function has gained significant clinical relevance recently. The latest developments in glycobiology, glycochemistry, and glycoproteomics have made the field more manageable and relevant to disease progression and immune-response signaling. Here, we summarize the current progress in glycoscience, including the new methodologies that have led to the introduction of programmable and automatic as well as large-scale enzymatic synthesis, and the development of glycan array, glycosylation probes and inhibitors of carbohydrate-associated enzymes or receptors. These novel methodologies and tools have facilitated our understanding of the significance of glycosylation and development of carbohydrate derived medicines that bring the field to the next level of scientific and medical significance.

Graphical Abstract

Together with DNA, proteins, and lipids, carbohydrates are one of the four major classes of biomolecules essential for living cells. Glycans in the form of glycoconjugates are displayed on cell surface as glycoproteins or glycolipids, and mediate a myriad of complex events, including pathogenic infections, cellular adhesion, migration and communication, organism development, cancer metastasis, blood-type determination, modulation of immunological responses and many other molecular recognition events.1 Being not encoded by the genome, glycan biosynthesis depends on a wide variety of enzymes, especially glycosyltransferases and glycosidases, leading to the tremendous structural diversity with glycosidic linkages assembled in a regio- and stereo-selective manner.2 Although the expression of enzymes involved in glycan synthesis is the key determinant, several conditions affect the enzyme reactions thus creating the glycans with diverse structures and heterogeneity.2c

Because of their highly heterogeneous nature in biological systems, glycans obtained by isolation or synthesis are often required for glycobiology studies. However, isolation of glycans in pure forms is extremely difficult and the major bottleneck in glycan synthesis is the regio- and stereo-selective glycosylation of specific hydroxyl groups among several between the two reacting sugar residues. Nevertheless, a variety of synthetic methods have been reported, including, (i) stereoselective glycosylation; (ii) design of orthogonal protecting groups for selective glycosylation and downstream manipulations; (iii) methods for protection and deprotection reactions.3 In addition, development of catalytic glycosylation,4 one-pot synthesis of glycans,5 and automated solid-phase oligosaccharide synthesis6 has been advanced to address major challenges in the field. To avoid the complexity of multistep chemical synthesis, robust chemo-enzymatic methods are often implemented for the synthesis of complex oligosaccharides and their conjugates that combine the flexibility of chemical synthesis and the reaction efficiency, site-selectivity, and substrate specificity of enzymes.7 Improvements in the methods of glycan synthesis and the tools for analysis provided rapid access to diverse, highly pure and well characterized structures for biological studies. Other discoveries that expanded our knowledge of carbohydrate-mediated recognition events in cancer, infection and immune response include, development of methods for glycoprotein expression and sequencing, use of glycoproteomics for glycan analysis, design of cell permeable probes for monitoring the glycosylation process, development of glycan arrays for efficient mapping of carbohydrate-protein interactions, development of glyco-enzymes inhibitors associated with disease progression, and in-vitro glycoremodeling for the optimization of therapeutic antibodies.8

In this Perspective, we outline the recent development of chemical and enzymatic synthesis of complex carbohydrates, glycan microarrays, and glycosylation probes, and highlight their applications in biomedical research and development, with particular focus on the study of viral infection. We also include recent progress of carbohydrate-based vaccines, homogeneous antibodies, anti-glycan antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and glyco-enzyme inhibitors with relevant examples in clinical or preclinical studies which are summarized in table S1 (SI). Other subjects regarding the impact of glycosylation on protein folding and the diseases caused by aberrant glycosylation and glycoprotein misfolding, the study of glycosylation associated with bacterial cell wall assembly, cancer progression, inflammation, lectin-mediated immune response and drug resistance can be found in other reviews.

1. Progress in synthesis of complex carbohydrates

The structural heterogeneity of glycans in Nature is originated by their complicated biosynthetic pathways, that vary among expression systems. Glycans are often synthesized without any template as non-linear, branched structures in which a monosaccharide is linked via α or β linkage to one of several hydroxyls on another saccharide to generate a substantial amount of structural complexity.2c In addition, some of the individual glycan moieties within an polysaccharide chain can be further phosphoryled, sulfated, methylated, or acylated at one or more hydroxyl groups to increase the diversity. Due to such a tremendous complexity, their chemical synthesis requires a proper retrosynthetic plan, including selection of protecting groups and glycosylation sequence and methods in addition to many other parameters such as solvent, temperature, etc. Achieving the desired stereoselectivity at the anomeric center is the main requirement for chemical synthesis. Accordingly, a vast majority of methods have been developed and utilized to achieve desired stereoselectivity in recent years.3

Protecting groups (PGs) possess a tremendous impact on the reactivity of donor and acceptor and ultimately modulate the stereochemistry of glycosylation.9 Generally, PGs are introduced as a temporary protection for functional groups (-OH, NH2) under strong experimental conditions and for control of reaction sequences.9a–b In addition to protecting the reactive functional groups, PGs can also tune the reactivity by direct or indirect participation, thus affecting the stereochemical outcome. For example, an acetyl protection at 2-O position favors 1,2-trans-glycosides with reduced reactivity whereas a 2-O-ether protection favors the formation of 1,2-cis-glycosides with enhanced reactivity, though often with compromised anomeric selectivity.9c–d

1.1. Stereo-control via direct participation of PGs.

A classic example of neighboring group participation (NGP) in carbohydrate chemistry is the acetyl group present at the C-2 position of a donor sugar to assist the departure of activated leaving group and stabilize the formation of oxocarbenium ion, causing the attack by acceptor from back side to form 1,2-tras glycosides.10 A tremendous amount of efforts has been made to find better participating groups at the positions other than C-2, to get the desired stereocontrol and to improve the reactivity of donor substrate as well. These protecting groups can be used to construct both 1,2-trans and 1,2-cis glycosides10b–c following the same mechanism by stabilizing the oxocarbenium-ion intermediate and drive the acceptors to attack only from one side.

The wide use of acyl groups to ensure 1,2-trans glycosylation generated lots of interests that resulted in the discovery of pivaloate,10b 4-acetoxy-2,2-dimethylbutanoyl (ADMB),11 and 3-(2-benzyloxyphenyl)-3,3-dimethylpropanoates 12 as improved protecting groups (Table 1). The base-labile but acid resistant participating protecting group, methylsulfonylethoxycarbonyl (Msc), was designed to provide an anchimeric assistance when situated at the 2-O position in Lewis acid-promoted glycosylations.13 In addition, another participating group, 2-nitrophenylacetyl (NPAc), which is orthogonal to a wide variety of PGs including TBDMS, Fmoc, Lev, PMB, Nap and Bz, was introduced by Fügedi and coworkers for the stereoselective synthesis of 1,2-trans glycosides.14 Recent introduction of the 2,2-dimethyl-2-(ortho-nitrophenyl) acetyl (DMNPA) PG improves the stability in basic conditions by replacing the two acidic protons in NPAc with methyl groups in DMNPA.15 This versatile protecting group plays an important role in the stereo-controlled synthesis of 1,2-trans and 1,2-cis glycosides through their neighboring as well as long-distance participation. Finally, the dialkyl phosphate group reported by Yamago et al.16 was used for the synthesis of 1,2-trans-glycosides.

Table 1.

Developments in protecting groups to control stereochemistry at anomeric center.

|

Ethers were introduced at C-2 position to enhance donor reactivity and also to control the stereoselectivity.17 The alkoxy methyl groups, including methoxymethyl (MOM),17 benzyloxymethyl (BOM),18a and 2-naphthylmethoxymethyl (NAPOM)18 are some of the notable examples of this series which are known to promote β-selectivity by blocking the α face via forming a cyclic intermediate. A similar effect was observed with the 2-picolinyl (Pic, pyridylmethyl) group when present at C-2 of donor sugar to form a six-membered ring for the stereoselective introduction of a 1,2-trans linkage.19 The picolinyl group was also been used to promote β selectivity via remote participation effect while masking the C-3 hydroxyl (Table 1). The Fairbanks group reported (thiophen‐2‐yl) methyl ether as a chiral and non-ester participating group to facilitate α-selectivity.20 Liu and coworkers showed that exclusive α or β selectivity can be achieved when a donor with 2-cynobenzyl ether reacted with acceptors of various reactivities.21 In case of electron rich acceptors, cis-nitrilium ion stabilizes the oxocarbenium intermediate leading to a nucleophilic attack from the β face. However, for electron poor acceptors, the 2-cyanobenzyl group participates via the H‐bond‐mediated aglycone delivery (HAD) mechanism to yield α selectivity. The TsNHbenzyl (TAB) ether present at C-2 position of glycosyl donors offers both α- and β-stereoselectivity by manipulating reaction conditions.22

The participating (S)-(phenylthiomethyl) benzyl (chiral auxiliary) group at the C-2 position of a donor moiety was reported by Boons and coworkers.23 The nucleophilic group of the auxiliary forms an oxocarbenium intermediate through a cis- or a trans-decalin system depending on the configuration of chiral auxiliary. (Table 1).23a Because of steric repulsion between the phenyl group and the proton, the auxiliary with S stereochemistry would favor the formation of 1,2-cis glycosides via the trans-decalin intermediate, whereas the auxiliary with R stereochemistry favors 1,2-trans glycosides via the cis-decalin intermediate.23b–c

Because of its linear structure that influences the participation in glycosylation, the azido group has been used as an alternative for amino-functional group.24 Other N-protecting participating groups that are widely used in glycosylation reactions of glucosamine include 2,2,2-trichloroethoxycarbonyl (Troc) group, pthalamide, and N-dimethoxyphosphoryl group.3f, 25 In addition, C-2 protection using N-benzylidene derivatives has received great attentions due to its stereo-directing nature leading to the 1,2-cis glycoside formation.26

1.2. Stereocontrol via PG-mediated conformational constrain.

The size of PG can have great impact on the stereochemistry of glycosylations.5e For example, cyclic PGS such as benzylidene, carbonate, oxazolidinone, cyclic silyl groups etc. have gained considerable attention in stereoselective glycosylation by restricting the flexibility of sugar rings to favor a conformation that can be attacked from one face.3e, 5g Crich and coworkers developed an effective methodology to construct a β-mannosidic linkage by the in-situ formation of α-triflate intermediate.27 In this methodology, activation of the 4,6-O-benzylidene-protected mannosyl thioglycoside donor in the presence of promoters followed by addition of the acceptor. The α-mannosyl triflate27b intermediate undergoes nucleophilic attack by an acceptor to afford the desired β-mannoside with excellent yield and selectivity (Figure 1). Benzylidene protection was proposed to favor the formation of α-triflate intermediate instead of oxocarbenium ion that often leads to the SN1 displacement to form an anomeric mixture due to the torsional strain of the half-chair or boat-form intermediate.27d This α-triflate intermediate shields the α-face to favor SN2 substitution to form β-mannoside.27c The effect of bulky PGs at the C-3 hydroxyl of 2-O-benzyl-4,6-benzylidene mannosyl donors on β-mannosylation was also studied,28a and it was found that the bulky tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) group at C-3 gave a poor β selectivity compared to its C-3 benzylated counterpart. A combination of TBDMS and substituted/non substituted propargyl ethers were also introduced at C-2 or C-3 positions to tune the β selectivity.28b–d

Figure 1.

Developments of protecting groups that interfere with the conformation of glycosyl donor to control the stereoselectivity of chemical glycosylation.

Inspired by the success of β-mannosylation using benzylidene PG, the Crich group reported carbonates as conformationally constrained PG for making α or β-glucosides, wherein the electronic effect of carbonates is also a contributing factor.29 Reactions of glucopyranosyl donors having 2,3 O carbonates provided moderate to excellent β-selectivity via glucosyl triflate intermediate in the absence of neighboring group or solvent participation.29a In contrast, the donor with 3,4-O-carbonate protections yielded moderate to no stereoselectivity under the conditions employed.29a In another study, 3,4-O-carbonate protection was employed in the glycosylation of 2-deoxysugars and 2,6-dideoxysugars using thioglycosides donors to generate highly α selectivity. The approach allows a wide range of glycosyl acceptors and donors to be used with good to excellent α-selectivity.29b An oxazolidinone group, a non-participating group at C2 can facilitate the simultaneous differentiation of the 2-amino- and 3-hydroxyl groups from other hydroxyl groups via a conformationally constrained mechanism (Figure 1).30

Among the chemical glycosylation reactions, the stereocontrol in sialylation represents the most challenging, often giving low yield and poor stereoselectivity. However, the oxazolidinone protecting group was successfully introduced to improve the α-selectivity in sialylation reactions. Takahashi and co-workers31 disclosed an effective sialylation strategy using donors with 4,5-oxazolidinone and 7, 8-O-dichloroacetyl groups. The sialoside donor was further modified to improve the α selectivity; for example, the Crich group and the Wong group introduced the N-acetyl-5-N,4-O-carbonyl-protected thiosialoside32 and the N-acetyloxazolidinone-protected sialoside with a dibutylphosphate leaving group (LG)33 respectively (Figure 1).

Over the years, various new and orthogonal protecting groups have been developed to allow the stereoselective formation of both 1,2-cis and 1,2-trans glycosides. Given the growing value of complex and well-defined oligosaccharides for biological studies, it is anticipated that the development of new protecting groups and protection/deprotection strategies will continue to be a major theme in carbohydrate chemistry.

2. Programmable one pot synthesis.

The huge database generated from numerous glycosylation reactions over the years has led to the development of more efficient glycosylation methods, including most notably the one-pot and computer-based programmable one-pot methods, and the solid-phase as well as liquid-phase automated methods. The one-pot synthesis was first reported by Kahne34a and Fraser-Reid34b using the qualitative concept of differential electronic effect on protecting groups and leaving groups, and further advanced by Ley’s quantitative assessment of the protecting group effect34c and Hung’s design of optimal combination of protecting groups.5d,34d The one-pot synthesis approach allows multiple reactions taking place efficiently in the same reaction flask without isolation and purification of intermediates using properly protected substrates with orthogonal leaving groups.34

The one-pot synthesis strategy was further developed into the programmable method which can be operated and guided by a computer software program to select the building blocks from a library of building blocks with well-defined reactivity relative to peracetyl thiomannoside as reference.5a, 5c The software “Optimer” contains the information on the relative reactivity values (RRVs) of glycosyl donors building blocks that can be used sequentially in the one-pot chemical reaction.5e The programmable one-pot synthesis has been used for the preparation of therapeutically important glycans, including heparin pentasaccharides, LacNAc oligomers, the cancer antigens Ley, sLex, fucosyl GM1, Globo H and SSEA-4, and the embryonic stem cell surface carbohydrates Lc4, and IV2Fuc-Lc4.3g,8,35

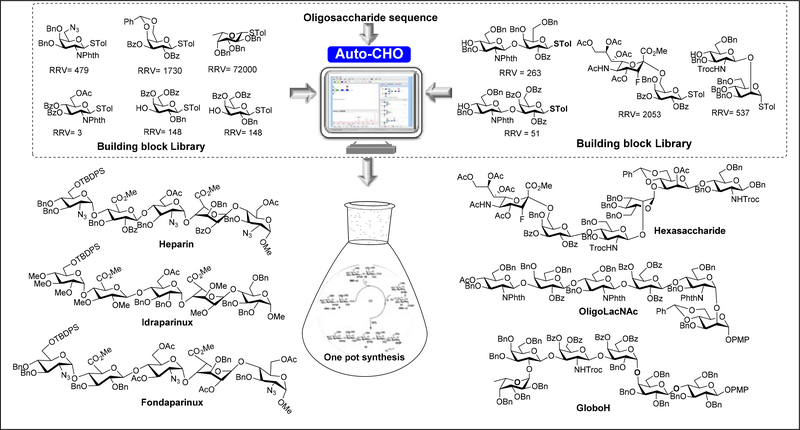

In 2018, the program was upgraded to “Auto-CHO” which brought together carbohydrate chemistry, artificial intelligence, and machine learning to solve a long-standing problem in carbohydrate synthesis (Figure 2).36 Based on the 150 building blocks with well-defined RRVs, 50,000 building blocks with predicted RRVs were generated through machine learning and added to the building block database of the Auto-CHO program. It also contains the RRVs of oligosaccharide fragments as donors for the assembly of polysaccharides.

Figure 2.

The workflow of Auto-CHO program. Auto-CHO allows users to input a desired glycan sequence and the program returns with one-pot glycan synthesis strategy from a set of selected building blocks with well-defined relative reactivity. List of selected important oligosaccharides prepared by programmable one-pot synthesis is presented.

Since sialic acid is usually found at the terminal position of oligosaccharides and it is the least reactive and most difficult to control for α-glycosylation. Sialic acid is usually linked to galactose or N-acetylgalactosamine in α−2,3- or 2,6-linkage, or to another sialic acid in α−2,8-, or α−2,9-linkage. So, sialylgalactose disaccharides with different protecting groups are prepared and used as building blocks because the reactivities of which are determined by the galactose residue. Using the Auto-CHO program, carbohydrate chemist can search for suitable building blocks from the library of 150 monosaccharides and fragments with validated RRVs and 50,000 virtual building blocks with predicted RRV for the one-pot synthesis of a target oligosaccharide.37 Guided by Auto-CHO, recently we have reported the synthesis of sialylated complex-type bi-antennary N-glycan (SCT) modified with 3Fax-Neu5Ac and its biological evaluation when present at the antibody Fc-region.37c We developed a programmable [2 + 2 + 2] one-pot strategy for the synthesis of hexasaccharide (Figure 2), by mixing the 3Fax-Neu5Ac-α2,6-Gal-STol donor (RRV = 2053) with the less reactive GlcNAc-β1,2-Man-OAllyl acceptor (RRV = 537) at −40 °C, followed by reaction of the disaccharide acceptor (RRV= 0) to afford the desired hexasaccharide in 26% overall yield. The one pot synthesis strategy was further implemented to the synthesis of protected heparin pentasaccharide,37b Idraparinux,37d and Fondaparinux37e using thioglycoside building blocks with predefined RRVs to allow the selective deprotection and preparation of regiodefined sulfate derivatives.

Depending on the availability of the building blocks and the experience in the chemist’s laboratory, one can decide the best option for the one-pot synthesis of the target of interest. This software program is now available to the research community free of charge.

3. Automated solid-phase oligosaccharides synthesis

Automated solid-phase synthesis of carbohydrates is much more challenging as compared to the synthesis of oligonucleotides and polypeptides because of their branched structure, presence of several -OH groups, and the necessity of regio-and stereoselectivity in glycosylation.6b–c This strategy requires numbers of steps, including the attachment of acceptor (nucleophile) to the solid support equipped with a linker, successive coupling of the monosaccharide building blocks, selective removal of temporary protecting group on resin bound oligomeric chain to allow next coupling cycle with orthogonally protected building blocks. The oligosaccharide is then released from the solid support, followed by deprotection and purification of the final product (Figure 3).38 This automated solid-phase method has been successfully demonstrated in the synthesis of complex glycans, including the record synthesis of a polymannose structure with more than 100 mannose units.6g This solid-phase method has received a great deal of attention since its introduction in 2001 and further improvement has been reported, though some drawbacks were also reported, such as requirement of excessive donor and, as in other methods, low coupling yields with less stereoselectivity in β-mannosylation and α-sialylation.6f

Figure 3.

Automated glycan assembly of oligosaccharides requires the use of appropriate orthogonal protecting groups and linker strategies for automated synthesis of diverse oligosaccharides of different origins on a solid support.

Improvements in automated glycan synthesis has originated a great number of technologies including the “selective leaving group activation-based one-pot solution-phase synthesis by Quest-210”.39 The solid-phase method originated by the Seeberger group was based on a modified peptide synthesizer.40 The design of the synthesizer has been further improved and the first fully automated solid-phase oligosaccharide synthesizer, Glyconeer 2.1 was reported in 2012 by the Seeberger group. Around the same time, alternative automation platforms, including the fluorous-tag-assisted synthesis by the Pohl group,41 the HPLC assisted oligosaccharide synthesis by the Demchenko-Stine group42 and automated electrochemical synthesis by the Nokami group were reported.43 Overall, the solid-phase automated synthesis increased the speed of oligosaccharide synthesis and was successfully applied to the synthesis of numerous notable targets including Ley, Lex antigens, short glycopeptides, glucosaminoglycan oligosaccharides, glycans of mammalian and plant origins, and GPI glycolipids.44

Automated glycan syntheses require proper selection of a compatible set of orthogonally protected monosaccharide building blocks and linker functionalized solid support. The nature of leaving group and protecting groups on donors and acceptors influence the reactivity and stereochemistry of glycosylation.45 The commonly used leaving group-promoter pairs in automated synthesis includes thioglycoside-NIS/TFOH, phosphate, and imidate-TMSOTf.44,46 The stereo-selectivity at the anomeric center can be controlled by a proper selection of participating protecting groups in donor substrates whereas the regioselectivity can be managed by temporary protecting groups to mask the hydroxyl groups that participate in the glycosidic bond formation (Figure 3). Orthogonal temporary protecting groups can also be used for construction of branched glycans. The concept of “approved building block” minimizes the number of PGs that are used during automated glycan assembly.46 Permanent non-participating group such as benzyl, azido, etc. and participating groups such as acetyl, benzoyl, trichloroacetyl, Piv, etc. have been used to direct the stereochemistry (Figure 3).44b–c Temporary protecting groups used to control the regioselectivity include Fmoc, napthyl, p-methoxy benzyl etc. Another important component in automated glycan syntheses is the linker that attaches the glycan to the solid support.45,47 The linker has to be stable throughout the acidic glycosylation and basic deprotection reaction sequences and also has to be effectively cleaved at the end to render the glycan reducing end in a useful form.45a Accordingly, metathesis-labile, base-labile, and photocleavable linkers have been developed and used in automated synthesis.45,48 In addition, the photocleavable-traceless linker was also explored to obtained the glycan with free reducing end.4

4. Chemo-enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharides.

Enzymatic synthesis of carbohydrates is stereoselective, can be conducted at ambient temperature without protecting groups, and has been recognized as an effective way to overcome the problem of large-scale synthesis.7e In nature, glycans are biosynthesized by various enzymes such as glycosyltransferases (GTs), glycosidases, phosphorylases, sulfotransferases, and others.7a–c In addition to glycosyltransferases, many glycosidases have been manipulated to run in reverse reaction as glycosylation catalyst through site directed mutagenesis. The major obstacle in enzymatic synthesis is the limitation of enzyme availability and substrate specificity. Nevertheless, the number of carbohydrate-synthesis enzymes is expanding and the techniques such as directed evolution and genome editing for altering the efficiency and specificity of enzymes are available.49

GTs catalyze the transfer of sugar from a nucleoside-mono or diphosphate sugar donor including UDP-Glc, UDP-Gal, UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-GalNAc, UDP-Xyl, UDP-GlcA, GDP-Man, GDP-Fuc, and CMP-sialic acid to an acceptor.50 The acceptor substrates of these enzymes range from a simple monosaccharide, an oligosaccharide or a complex glycoconjugate containing multiple glycosidic linkages to the hydroxy group of an amino acid on a protein. The use of bacterial GTs is generally more convenient and efficient compared to their mammalian counterparts, because: (i) they are more stable and easier to express in bacterial systems and are more soluble than the membrane-bound mammalian GTs which are often expressed as the soluble domain; (ii) the production cost is less than that of mammalian GTs expressed in eukaryotic or insect cell lines; (iii) many bacterial GTs have been isolated and well studied.

The substrate specificity of many wild-type GTs can be further enhanced or altered by rational design and directed evolution. In addition, an increasing number of crystal structures of GTs in complex with donor or acceptor is available and has provided valuable information on their catalytic mechanism and facilitated the rational engineering of GTs with desired functions.7g

Early attempts to use GTs for synthesis are limited by the high cost of sugar nucleotides and the feed-back inhibition caused by the nucleoside phosphate by-product generated in the reaction (Figure 4A).51a However, these problems have been solved by Whitesides and coworkers as demonstrated by the large-scale preparation of N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc) in a multi enzyme system with in-situ regeneration of sugar nucleotide donor.51 Since then, multienzymatic approach with sugar nucleotide regeneration has been adopted and utilized for making clinically important glycans including sLex, sialyl-T antigen, disialyllacto-N-tetraose, heparin oligosaccharides, hyaluronic acid and other complex carbohydrates.7a–c,52 Recently, this efficient recycling strategy was demonstrated for the large-scale synthesis of the tumor associated carbohydrates antigens GloboH and SSEA4 for the development of vaccines against breast cancer.7d, 53

Figure 4.

Chemoenzymatic synthesis of carbohydrates and homogeneous glycoproteins. (A) Enzymatic synthesis of glycans with sugar-nucleotide regeneration systems. (B) Evolution of glycosidase to glycosynthase for glycan remodeling.

Glycosidases (GHs) are another class of enzymes which have been utilized for industrial processing. Depending on the site of glycosidic bond cleavage, GHs are classified into two categories, namely endoglycosidases which cleave an internal glycosidic bond, and exoglycosidases which cleave terminal sugars at non-reducing end.54 Glycosidases comprise of over 130 different families having diverse structures with a conserved active site that facilitates the hydrolysis of specific glycosides to produce hydrolyzed products with inversion or retention at the anomeric center. In the active site of glycosidase, two proximal carboxyl side-chains played a key role in the catalytic mechanism.55a Structural variations within the binding site control the position of glycosidic bond cleavage. Glycosidases are widely available, highly robust and tolerance to organic solvents. However, for routine practice in glycan synthesis, there are limitations such as, poor regioselectivity, undesired side-reactions of self-condensation, and low yields due to competing hydrolysis.

The interest in driving the glycosidase activity toward glycosidic bond formation has led to the development of effective methodologies and conditions to minimize the hydrolysis of final product and increase the synthetic yield, and among the methods, the most effective one is the mutational engineering of GHs active site by site directed mutagenesis combined with substrate engineering.55 Both glycosyl fluoride56a and sugar oxazolines56b have been designed and efficiently used in glycosidase-catalysed synthesis because their structures are either close mimic of the high energy intermediate or the transition state of the enzymatic reactions.

Another way to address the hydrolyzing property of glycosidase is to create a new class of enzyme termed glycosynthase (GS) by site directed mutagenesis of a nucleophilic aspartyl residue of the catalytic site to a non-nucleophilic one (such as alanine, Ala) to prevent the hydrolysis of newly formed glycosidic linkage.57 The resultant GH-mutant can transfer the activated sugar donors in the form of oxazoline or fluoride to a suitable acceptor with increased yield.57b

Currently, endoglycosidases have been used for the deglycosylation of heterogeneously N-glycans at Asn-297 of IgG-Fc to leave a single GlcNAc as acceptor for the subsequent enzymatic transfer of a preassembled glycan en-block in the form of oxazoline using a glycosidase mutant to form a homogeneous glycoforms (Figure 4B).58 This approach resulted in the first in-vitro glycoengineering of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, Rituximab to enter the clinical trial for the treatment of B-cell lymphoma.58b, 58d

The method of chemo-enzymatic synthesis of glycoproteins is currently limited to the synthesis of proteins with one or two glycosylation sites. To synthesize homogeneous glycoproteins with multiple glycosites, it still depends on other methods,59 including, for example total chemical synthesis,59a native chemical ligation,59b intein-mediated ligation,59c–d sugar-assisted glycopeptide ligation59e glycosylation pathway engineering59f, and chemoselective peptide ligations.59g However, these methods are complicated and more efficient methods have to be developed to address the role of glycosylation in post-translational modification.

5. Development of glycan microarray

Early efforts to investigate carbohydrate-protein interactions involved indirect methods such as hemagglutination inhibition and inhibition of precipitation assays.60a Later, solid phase binding assays were introduced by which glycan binding proteins can be directly radio-labeled and the binding was determined using thin-layer chromatography (TLC).60 However, these methods were limited by the requirement of large quantities of both the glycan and its binding protein partner. Because of structural microheterogeneity and complexity, the glycans cannot be easily obtained by isolation and purification from natural sources.60b Moreover, the diversity of the N-glycan structures is estimated to exceed 20,000 structures in human as glycoconjugates. All of these factors contributed to the demand for a microarray platform that mimics the cell surface to provide a multivalent presentation of structurally diverse glycans.

An array of neoglycolipids was first reported by Ten Feizi, where glycans were extracted from natural sources as a mixture of glycolipids;60c however, the issues of purity and location of well-defined structures on the array may complicate the study. In 2002, four research groups reported new versions of glycan microarrays with well-defined structures and location on the array. These include a polysaccharide and glycoconjugate microarray,61 monosaccharide chips,62 arrays of natural and synthetic neoglycolipids,63 and arrays of synthetic oligosaccharides in microtiter plates.64 Since then, carbohydrate microarrays have become powerful tools to study the binding interaction of carbohydrates with a wide variety of biomolecules including proteins, nucleic acids, whole viruses, and cells in a high-throughput manner.66, 67 Glycan microarrays were also used to study the binding specificity and inhibition of protein-glycan interactions,67a–b glycoenzyme reactions,67c–e epitope mapping of lectins and antibodies,67f and identification of biomarkers (Figure 5A).67g–h

Figure 5.

development of glycan microarrays. (A) Glycan array platform. (B) Linker strategies and coupling chemistries for covalent and non-covalent arrays on different surfaces, (C) Glycan arrays on aluminum oxide coated glass slide (ACG-slide) for hetero-glycan binding specificity of HIV-1 antibodies.

Novel methods of array fabrication have contributed much to the progress of glycan microarray technology.68 Depending on the method of immobilization, the array fabrication can be classified into two categories: covalent and non-covalent arrays (Figure 5B). Non-covalent glycan arrays involve adsorption of free or modified carbohydrates or glycoconjugates on the surface of a solid support such as nitrocellulose61 or oxidized polystyrene.69 These methodologies are easy to operate and do not require complicated glycan derivatization; however, the glycans may not sustain on the array during washing steps. New methods were therefore developed to overcome this issue, including the array of neoglycolipids on hydrophobic surface,70 thioglycosides on gold62, alkyl derivatized glycans on the polystyrene surface of microtiter plates64 and biotinated glycans on streptavidin coated surface.66f Moving further, Pohl’s group introduced selective immobilization of fluorous (C8F17) tagged monosaccharides to the fluoroalkylsilane coated glass slides that resist washing with detergent.71 The strong noncovalent fluorous–fluorous interaction resulted in the development of a fluoride-based array that allowed the convenient characterization of enzyme kinetics by MALDI mass spectrometry without matrix.72

In covalent arrays, glycans are usually functionalized with a linker that reacts with an activated surface to form a covalent bond.68 The most commonly used functional groups of spacers are maleimide, amine, thiol, epoxide, and cyclopentadiene that form a covalent attachment to the modified surface (Figure 5B).66e, 73 However, the robust technology developed by Blixt et al. with amine-terminated glycans and commercially available NHS-ester activated slides74 has been utilized by a number of groups to array various glycans, including heparin glycans,75a N-linked glycans,67f cancer related carbohydrates,67h, 75b and sialosides.75c The condensation reactions between amines, hydrazides, and oxyamines with aldehydes have also been used for direct immobilization of free reducing glycans with the slide grafted with these functional groups.76 Apart from the thiol-maleimide coupling and the amide-bond formation, cycloaddition reactions also served as a basis for glycan array preparation.77a Houseman and colleagues reported the use of Diels-Alder reaction to immobilize a library of monosaccharides to a self-assembled monolayer,77b while the triazole-forming click reaction was also employed to array a diverse set of di, tri-, and tetrasaccharides in microtiter plates.77c In addition, photoreactive groups have been used for immobilization of underivatized glycans. For examples, commercially available aryl-trifluoromethyldiazirine dextran modified slides have been used to immobilize plant xyloglucans as well as various bacterial polysaccharides, mammalian glycoproteins, and even whole cell extracts.78

An alternative and efficient immobilization strategy was recently reported by Wong at al. where the phosphonic acid linked glycans were printed onto the aluminum oxide-coated glass slide (ACG) to form the phosphonate linkage spontaneously to permit a high control of glycan density and distribution and produce a homogeneous array with improved signal-to-noise ratio.79 A heterogeneous mixture of glycans on array surface with controlled density and spatial arrangement that mimics the local epitope environment of cell surface was created for the study of heteroligand interactions with proteins or antibodies (Figure 5C). Accordingly, the ACG arrays have been used to immobilize heteroglycans to study the hetero-ligand binding specificities of recently isolated HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies.80 In additions, protocols for the quantification of the carbohydrate–protein interactions and determination of the multivalent dissociation constant (KD, surf), solution dissociation constant (KD) and Ki have been developed.81

Another important aspect of glycan array technology is the issues of sensitivity and dynamics. Some of the recent development in detection methods includes 1) fluorescence-based measurement to improve the sensitivity of detection;67h 2) use of surface plasmon resonance for the real time measurement of dissociation and association constants on the array in a label free format;82 3) MALDI-TOF mass spectrometric analysis of glycan sequence, activity of glycosyl transferase, and glycan composition using photocleavable linkers;83 4) nanoparticle-based assay that can reach the sub-attomolar detection level and has the advantage of photocleavable stability over fluorescent dye.84 With this overwhelming number of different chemistries and technologies developed in array fabrication to ensure the desired stability and control of glycan presentation, a remaining major challenge is the comparison of different binding data generated from different array platforms, and the issue of whether the glycan array is a true mimic of the cell-surface display of glycans. Nevertheless, based on the substantive advantages and biological insights that have originated from the glycan array technology to date, further refinements will only increase the quality of this robust platforms.

6. Glycosylation probes.

Mammalian cell surface glycosylation is one of the most important post-translational modifications of proteins. The glycans are main determinants of many biological events such as cell growth, cell-cell communications, host-pathogen interactions, immune response, and cellular signaling. In addition, a unique set of glycans can be found on tumor cells that acts as indicators of tumor onset and progression. Thus, development of methods to control the cellular glycan expression may contribute to the understanding of glycan-mediated recognition events and correlation of glycan sequence with manipulation of glycosyltransferase (GTs) activity has been used to control the glycan profile; however, the complex nature of glycan biosynthesis pathway and GTs activity may limit the utility of this approach.85 Although advances in glyco-proteomics enabled the glycan structure-function studies in-vitro using lysed cell or tissue samples, such methods cannot offer the real-time information of glycan-related biological events.86 Moreover, such kind of samples may have unpredictable loss of glycan information during the preparation. So, chemical strategies to manipulate cell surface glycosylation provide a valuable alternative to genetic approaches.87

Various strategies have been developed for tracing the pathway of glycosylation through glycan labeling and analysis, including lectin-based analysis, selective chemical conjugation, and metabolic oligosaccharide engineering (MOE). Lectins that specifically bind to the glycans have been used in the form of nanoprobes (nanoparticles of quantum dots) for analysis of cellular glycans.88 Chemical covalent conjugation allows selective labeling of cell surface glycan through mild periodate or enzyme-based oxidation of polyhydroxyls into aldehydes which can be ligated with probes containing aminooxy or hydrazine groups.89a Boronic acid-based nanoclusters have been used to form tight and reversible complex with adjacent hydroxyl group of cell surface sialic acid for selective labeling and detection.89b

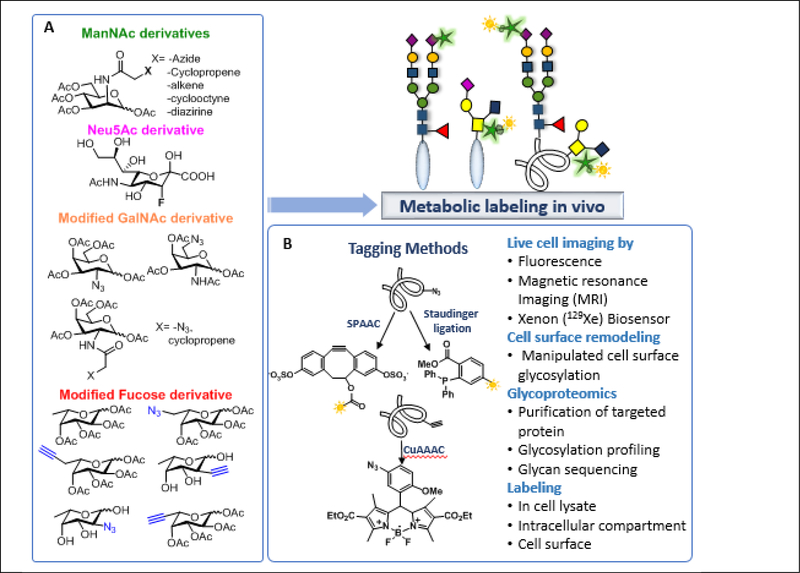

Metabolic oligosaccharide engineering (MOE) allows the incorporation of biorthogonal chemical reporters into target biomolecules using host-cell glycosylation machinery.90 These reactive chemical reporters do not cause significant structural changes of substrates and can be tolerated by various enzymes involved in the glycosylation pathway (Figure 6A). Various types of chemical reporters have been designed and used as substrates of glycosyltransferases for incorporation into the glycoconjugates that can be further coupled with fluorescent tags or affinity probes to enable detection, imaging, and purification of specific sets of glycoconjugates.91 Such reporters should be small in size, accepted by glycosyltransferases and the sugar nucleotide synthesis enzymes, inert toward nucleophiles or other enzymes inside the cell, and selective in reaction orthogonally with another reporter to form an adduct for imaging. When labeling a desired sugar residue such as fucose or sialic acid, both being highly expressed in cancer cells, the respective reporters are used. Mammalian cells can convert the ManNAc analogs to the corresponding sialic acid analogs, provided that the analog does not interfere with enzymatic activity.92 However, the use of modified sugars in free forms is limited by their cell permeability, therefore peracetylated probes are used to cross cell membrane and are transformed into the free forms via deacetylation by intracellular esterase.92 Some of the well-known chemistries to label the reporter-tagged biomolecules include Staudinger ligation,90b,91a Cu-assisted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC),93 and the recently famed strain promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC).94 In addition, photo-induced electron transfer probes such Azido-BODIPY 95 and dibenzocyclooctynol dyes have been developed recently to reduce background interference (Figure 6B).91d, 94c Metabolic labeling offers highly selective reaction between the modified glycan and the labeling agent through various chemistries and can be applied to live-cell imaging, glycoprotein labeling, cell surface glyco-remodeling, and glycoproteomic analysis for identification of novel glycans on diseased cells.

Figure 6.

Glycosylation probes for selective glycan labeling. (A) Examples of modified sugars for incorporation into the glycoconjugates through glycan biosynthetic pathway. (B) Tagging methods and coupling strategies.

Despite great promise, the probes currently used still suffer from insufficient selectivity and slow kinetics, and thus are difficult to reflect the real-time process of glycosylation, though they are useful for identification of disease-specific glycans. For example, the probes used to date for fucose are not accepted by all the 13 human fucosyltransferases thus generating a bias result and that the orthogonal reaction may not be fast enough to represent the real dynamics of the glycosylation reactions. Development of new probes which can be fully accepted by the same class of enzymes and can be imaged rapidly to probe the dynamics of the glycosylation process in real time will facilitate our understanding of the complex glycosylation process in life.

Use of modified sugar analogues to interfere with the glycosylation pathway and to enrich certain glycoforms of interest has been used for a long time. Among them, α-mannosidase-I inhibitors, imminocyclitols, deoxymannojirimycin and kifunensin have been utilized for the production glycoproteins containing high-mannose type glycans.87 In addition, a panel of fluorinated or alkynyl derivatives of fucose were used to deplete GDP-fucose, the substrate used by fucosyltransferases and its incorporation into the glycoproteins.85 The inhibitors were used to produce fucose-deficient antibodies in CHO cells to enhance antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity activities.96 However, recent development in CRISPR-based gene editing technologies in cell culture provided a better control of glycosylation for the preparation of glycoproteins such as antibodies which are enriched with certain glycoforms.97

7. Role of carbohydrate in pathogenic infection.

The frequent emergence of infectious diseases, particularly those caused by deadly viruses, often cause a huge threat to human health and create immense challenge to the healthcare system worldwide. A large number of viruses have evolved to take advantage of host-cell glycosylation processes by decorating the cell surface proteins with glycan moieties.98 The first step in viral infection is attachment to the surface receptor on host cells. Therefore, the viral surface glycoproteins are major determinants of host specificity, pathogenicity, and transmissibility of viruses. Various cell surface carbohydrates99 such as sialic acid-terminated glycans,99a glycosaminoglycans,99b blood group antigens99c and immune-cell lectins serve as host-cell receptor to facilitate viral attachment and entry. Although many cell surface proteins of viruses are glycosylated, the glycosylation is highly variable and it is largely dependent on the location of viral entry and host cell glycosylation machinery during the infection (Figure 7).98c However, irrespective of their glycosylation profile, most of the viral glycoproteins played a vital role in the entry and virus replication process.

Figure 7.

Glycosylated viral glycoproteins. (A) Structure of fully glycosylated trimeric hemagglutinin (HA). Glycans are in green: N-27 glycosylation is essential for folding and N-142 glycosylation is essential for receptor binding specificity (B) 3D structure of SARS-CoV-2 trimeric spike (S) glycoprotein side view. Each monomer has 1,273 amino acids with 22 N-glycosites and 2 O-glycosites. According to GISAID, there are more than 60,000 S protein variants and 800 sites of mutation in July 2020. Color codes: Red, mutation sites; Yellow, RBD region; Gray, S1 domain; Dark Gray, S2 domain; Green: N-glycosites; Blue, O-glycosites.

The role of surface glycosylation in the virus life cycle and immune evasion has been exploited for envelope glycoproteins, including the gp120 of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1),100 influenza virus glycoprotein hemagglutinin (HA),101 spike glycoprotein (S) of coronaviruses,102 glycoprotein (gp) of Ebola virus,103 and envelope (E) glycoprotein of Dengue, Zika, and other flaviviruses.104 Most viruses typically utilize the N- and O-linked glycosylation to decorate their surface proteins. The N-linked glycosylation has become an area of intense research in recent years because of their implications in several glycan-mediated processes essential for viral survival. HIV 100d and influenza viruses 101b rely on the expression of specific oligosaccharides to escape from host immune response. Additionally, the other viruses such as SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, MERS, Hendra, hepatitis, and West Nile utilize N-linked glycosylation for important events such as entry, proteolytic processing, maturation, and trafficking.102, 104 Understanding the role of cell surface glycosylation in the life cycle of viruses would pave the way for development of next generation vaccines and anti-viral agents.

The N-linked glycan biosynthesis involves the transfer of Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 from its dolichol derivative to the Asn residue of Asn-X-Ser/Thr sequon of a nascent polypeptide chain, where X is any amino acid except proline, by oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).2a After removal of terminal glucose moieties by glucosidases, the glycoprotein is then translocated from ER to the Golgi apparatus, where other processing enzymes such as glycosidases are involved to further trim down the glycan which is subsequently built up by glycosyltransferases to generate mature glycans with vast heterogeneity, including oligomannose, hybrid, and complex-type glycans.2c

Recent studies on cell-surface glycosylation revealed the new specificity of OST toward an aromatic pentapeptide sequon105a–b and the interplay between GlcNAc transferases and fucosyltransferases 105c that control the structures of N-linked glycans. The mucin-type O-linked glycans usually are formed by covalent attachment of GalNAc to the serine, threonine or tyrosine residue by polypeptide-N-acetylgalactosamine transferases (ppGalNAcT).106a There are a total of 8 mucin-type O-glycan cores, each of which can be processed further as proteins pass through the Golgi apparatus. The structural heterogeneous nature of O-linked glycosylation constitutes a major challenge in the study of glycan structure and function. A number of viral glycoproteins that contain mucin-like domains with high proportions of serine or threonine residues modified with mucin-type-O-linked glycans include, Ebola glycoprotein, herpes simplex virus gp protein, and respiratory syncytial virus G protein.106b–c

The extraordinary complexity in structure and diversity presented a great challenge to characterize the N- and O-linked glycans formed by various glyco-enzymes in the ER and Golgi compartments. To this end, the advances in mass spectrometry (MS) and chromatography, and the availability of various glycosidases have facilitated the structural characterization of glycans and glycopeptides.102d–e The new developments in matrix assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) and electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry allow systematic characterization of viral glycome, including the exact glycan structure presented at individual glycosylation sites on surface glycoproteins.107

7.1. HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (gp120)

Trimeric gp120 is a surface glycoprotein of HIV-1 envelope, which facilitates virus entry into the host cell and plays a central role in HIV infection.108 To infect the cell and release the viral genome into the host cell, HIV gp120 binds to the primary cellular receptor CD4 on T cells and then to the co-receptors, CXCR4/CCR5, while gp41 facilitates viral and host cell membrane fusion. Interestingly, ∼25 glycosylation sites are known on the surface gp120, of which ∼7–8 are situated in the V1/V2 and V3 variable loops and the others in the remaining core gp120 region.109 The glycans on gp120 are not only important for the proper folding of gp120 and viral infection but also shielded the virus from host immune attack.100a It has been demonstrated that the mutations at several glycosylation sites significantly affect viral infectivity and bindings towards neutralizing antibodies.110

It is however noted that glycosylation is cell specific and most of the studies on the effect of glycosylation are based on the gp120 expressed from different cells instead of human T cells. The outer domain of the gp120 is an important vaccine target because it contains the conserved peptide epitopes or glycans as targets for various recently isolated broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), such as PG9, PG16, VRC01, VRC-PG04, NIH45–46, 3BNC60, b12, PGT series antibodies, and 2G12.111,100c–d However, the virus has evolved to evade neutralizing antibody responses through a high mutation rate, conformational flexibility, and extensive glycosylation of conserved epitope.100d In addition, as described above, the bNAbs isolated from the HIV positive patients that target the gp120 glycans have been analyzed with different glycan array formats, and different results were produced. A typical example is the study of PG9 binding on glycan array; in one study, the ligand was shown to be a mixture of Man5 and a complex type glycan80, while in another study, the ligand was suggested to be a hybrid-type glycan67f. In addition, the best glycan recognized by 2G12 in the glycan analysis was used for the design of vaccine; however, the elicited antibodies only recognized oligomannose but not gp120100c,d. These results suggest that the true glycan antigens on gp120 expressed in human T cells may be different from those expressed in other cells and that the high-affinity glycans obtain from a glycan array analysis may not represent the true ligands for the antibodies isolated from HIV patients. Another challenge is that the immunization studies using recombinant gp120 as immunogens generated antibodies which are able to recognize the epitopes in variable loops but the resulting sera generally have low neutralization ability.110 Nevertheless, it is apparent that the bNAbs have great potential to be developed as therapeutic antibodies against the infection and lower the viral load though they may not be able to clear the virus completely.

HIV vaccine development may be the ultimate solution but is the most challenging, in part due to its ability of mutation to resist immune responses. However, a great number of advances have been developed, including the discovery of more potent bNAbs, the structural information on bNAb-gp120 complex, the design of better immunogens based on improved understanding, and the development of right animal models to understand the mechanism in details.

7.2. Influenza hemagglutinin (HA)

There are four types of influenza viruses, A, B, C, and D, and types A and B viruses cause seasonal flu. Type A viruses are classified by subtypes based on the surface hemagglutinin (H or HA) and neuraminidase (N) proteins into 18 H and 11 N subtypes. Since the 1918 Spanish H1N1 pandemic, there have been only three influenza subtypes namely H1N1, H2N2, and H3N2 that infect and transmit efficiently in humans. A new strain of influenza A H1N1 virus was emerged in 2009 resulting in another pandemic. The influenza surface HA glycoprotein is expressed as a trimer consisting of receptor binding HA1 domain and membrane-fusion mediating HA2 subunit.101d HA is a class I viral fusion protein that mediates viral entry by binding to host sialoside receptors via the receptor binding domain (RBD) on HA1. As the main target for immune response, the HA glycoprotein mutates more frequently compared to the other influenza viral proteins. 101b

The HA protein undergoes posttranslational glycosylation resulting in the expression of highly diverse N-glycans of high mannose, hybrid and complex types.101a Some of the N-glycans on HA surface can be sulfated as further structural modifications. HA glycosylation plays an important role in folding, so deglycosylation may result in improper protein folding which is further degraded or accumulated in the Golgi complex.112 However, not all of the 6 N-glycosylation sites of each monomer are crucial for HA folding and transport; for example N27 is essential for retaining the structural integrity of HA and N142 is essential for receptor binding specificity113 while the other glycosites have no significant effect on the virus life cycle (Figure 7A).

To transmit among humans and avoid antibody recognition from host immune response, influenza virus mutates rapidly at the globular domain of HA with increasing glycosylation and circulates seasonally,114 though the mutation rate of glycosylation site is lower than those that are exposed for immune recognition114a. Another issue is that the structures of HA receptors expressed on the cell surface of the respiratory track have not been fully elucidated114b so the binding specificity of HA is still limited to the sialylgalactose disaccharide with alpha 2,3- or alpha 2,6-linkage114c to the LacNAc unit or its repeats114d for avian and human influenza HA, respectively. The specificity toward the internal part of the glycan receptors is not well understood and requires access to the cell surface glycans in the respiratory track, probably in the array format.

Despite tremendous research has been devoted to develop a universal vaccine that can elicit a broadly protective immune response against types A and B influenza viruses and their subtypes, the goal has not been realized yet and the flu vaccine is still produced by traditional method based on the virus strain predicted to be the circulated one and renewed annually. The traditional egg-based flu vaccines are the most common and provide satisfactory outcome. However, in the past two decades a great advancement in the field was observed, including the discovery of broadly neutralizing antibodies such as F10, CR9114 and 6261, C179, and FI6, isolated from either human B cells or vaccinated mice.115 These bNAbs mostly target the stem region of type A HA near the HA2 fusion peptide and neutralize different influenza sub-types in vitro, while some have cross-reactivity against type B viruses.115a Further improvement of the antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and other effector functions by Fc-glycan engineering of FI6 has been reported58b, providing a new opportunity for the development of universal antibodies against influenza viruses. The sequence alignment of HAs from various influenza strains and the highly conserved epitopes recognized by bNAbs have provided information for the design of consensus sequences for universal vaccine development.113a,116 However, the most conserved amino acid sequences are found in the interior of HA, and the outer domain of HA that is the target of neutralizing antibodies is less conserved and often mutated through antigenic drifts and shifts, causing a challenge in universal vaccine design.116a

Because the HA sequence near the glycosylation sites is highly conserved, removal of the outer part of glycans to generate mono-glycosylated HA with retention of the trimeric structure was found to be an alternative vaccine design to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies. The vaccine served the purpose of exposing the conserved sequences that are covered by large glycans for induction of more antibodies including those with broadly neutralizing activities.116 This approach has been further applied to the design of a monoglycosylated chimeric HA vaccine with the head group from the consensus H5 sequence and the stem from the consensus H1 sequence. Immunization of the resulting chimeric HA construct with the glycolipid adjuvant C34 elicited a broadly protective immune responses against the H1, H3, H5, H7 and H9 subtypes. 116c

7.3. Coronavirus spike protein (S)

The outbreak of a novel pathogenic coronavirus in 2019, called SARS-CoV-2, that caused a global pandemic is highly infectious with more than 14 million cases and 500,000 deaths in July 2020. The virus infects human airway epithelial cells through the interaction of human ACE2 receptor with the viral transmembrane spike (S) glycoprotein. The S glycoprotein of coronavirus (CoV-2 S protein) forms a homotrimer for attachment to cell surface receptor and fusion with host cell.102a–b As a sole antigen on the virus surface, CoV-2 S protein is the main target of neutralizing antibodies and a main focus of vaccine development. CoV-2 S protein is synthesized as a single-chain precursor of 1,273 amino acids and trimerizes after folding. It is composed of an N-terminal S1 subunit, the receptor-binding domain (RBD), and a C-terminal S2 subunit, driving membrane fusion. Activation of CoV S proteins takes place upon uptake of virion by host cell followed by cleavage at S2’ site, so that they can subsequently transition to the post fusion conformations.102c CoV S proteins are extensively glycosylated, with SARS-CoV and MERS viruses both encoding 69 N-linked glycosylation sites per trimeric spike, and the trimeric SARS-CoV-2 S protein containing 6 O-glycosites and 66 N-glycosites102d–e where each monomeric RBD domain having two N-glycosites and two O-glycosites (Figure 7B).

The role of glycosylation in the S protein in the virus life cycle is not well understood and it is noted that these glycosites were determined from the SARS-CoV-2 S protein expressed from the kidney Vero-E6 cells instead of the epithelial cells of the primary infection site in the respiratory track. Nevertheless, these extensive post-translational modifications are often required for protein folding and functions and for masking the immunogenic protein epitopes from the host immune system by occluding them with host-derived glycans.102a

A site-specific analysis of N-linked glycosylation on soluble SARS, MERS and HKU1 CoV S glycoproteins expressed in HEK293F cells revealed extensive heterogeneity.117 The glycan structures range from unprocessed high-mannose-type to complex-type glycans. Glycan analysis studies of trimeric S proteins revealed the presence of oligomannose patches at specific regions of high glycan density on MERS-CoV S. The S proteins of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV have an amino-acid sequence identity of around 77%.118 Such a high degree of sequence similarity raises the possibility that cross-reactive epitopes may exist. However, SARS-CoV RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies do not have appreciable binding to SARS-CoV-2 S, suggesting that antibody cross-reactivity may be limited between the two virus RBDs.119 As mentioned, the host cell line used to produce the glycoprotein has a strong influence on the glycosylation pattern and compositions because different host systems may express glycosylation enzymes and transporters differentially that contributes to the different profiles of glycosylation and heterogeneity.

There are currently no vaccines that can cure or prevent SARS-CoV-2 infections or the resulting illness, COVID-19. Researchers around the world are working on the development of rapid testing methods and effective therapies as well as preventive vaccines against COVID-19. In any event, vaccination is considered to be the most effective mean to terminate the spread of the pandemic and recent efforts in vaccine development have shown promising results. However, according to the database from GISAID in July 2020, there were more than 60,000 sequences of S protein variants reported with mutations at more than 800 sites. This broad scope of mutation and glycosylation represents a big challenge in the development of effective vaccines or therapeutic antibodies with broadly protective activity against the virus infection, and it also indicates the importance of alternative treatments.

Conclusion

This perspective outlines some of the pioneering innovations in the field of carbohydrate synthesis with the goal of understanding the functional role of carbohydrates in various biological events in order to translate the knowledge into therapeutic developments. Advances in methodologies for the production of complex carbohydrates in sufficient quantities coupled with key technologies such as glycan microarray and glycosylation probes, as well as glycoproteomic analysis methods have facilitated our understanding of carbohydrates in biology at the molecular level. Moreover, the development of chemoenzymatic glycan synthesis methods, in vitro glycoremodeling techniques, glycosylation pathway engineering, glycoconjugation strategies, glycosylation-enzyme inhibitors, and glycan sequencing methods, fueled a great enthusiasm for the design of homogenous antibodies and glycoproteins, and antibody-drug conjugates. In fact, several drug candidates originated from these technologies have been advanced to clinical trials, though a number of areas in the field are still not well understood, which will undoubtedly be the focus of future research activities.

In summary, the analysis and structure-function study of glycosylation is expanded from abundant glycans to minute ones conjugated to other biomolecules, from cell surface to intracellular compartments, from monosaccharides to oligosaccharides, from in vitro to in vivo study, and from cells to tissues. However, considering the efficiency, sensitivity and significance of these advances, further research is necessary to improve the tools and methods used for the study of biological glycosylation. Nevertheless, the development of better synthetic and analytical methods as well as novel labeling and detecting technologies for the imaging, diagnosis and treatment of glycan-mediated diseases has not only facilitated a better understanding of biological glycosylation, but also catalyzed the development of carbohydrate-based medicines, making the field of glycoscience advanced to the next level of scientific and medical significance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our work related to carbohydrate-based technologies was generously supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI130227) and the National Science Foundation (CHE-1954031). Authors gratefully ackoweldge all the glycoscience community worldwide who have contributed to transforming glycoscience to the next level of biomedical research. We would also like to thank Dr. Cheng-Wei Cheng of Academia Sinica for his help to prepare the image of the S protein in Figure 7 and all other scientific collaborators and cherished collegues at Scripps Research and Academia Sinica.

Biographies

Sachin S. Shivatare obtained his Ph.D. in Carbohydrate Chemistry (2013) from Genomic Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, involved in the development of chemo-enzymatic synthesis of complex carbohydrates, glycan microarrays, and glyco-conjugate vaccines. In 2013, he joined CHO Pharma Inc. Taiwan, where he worked on the glyco-engineering of therapeutic antibodies and development of carbohydrate-based therapeutic agents. Currently, he is a Research Associate at The Scripps Research Institute, California.

Sachin S. Shivatare obtained his Ph.D. in Carbohydrate Chemistry (2013) from Genomic Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, involved in the development of chemo-enzymatic synthesis of complex carbohydrates, glycan microarrays, and glyco-conjugate vaccines. In 2013, he joined CHO Pharma Inc. Taiwan, where he worked on the glyco-engineering of therapeutic antibodies and development of carbohydrate-based therapeutic agents. Currently, he is a Research Associate at The Scripps Research Institute, California.

Dr. Wong is currently the Scripps Family Chair Professor of Chemistry at the Scripps Research Institute. His research interests include the development of new methods to study biological glycosylation and related disease progression.

Dr. Wong is currently the Scripps Family Chair Professor of Chemistry at the Scripps Research Institute. His research interests include the development of new methods to study biological glycosylation and related disease progression.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information (Recent progress of carbohydrate-based therapeutic agents with relevant examples in clinical or preclinical studies are summarized)

REFERENCES

- (1) (a).Varki A Biological roles of oligosaccharides: all of the theories are correct. Glycobiology 1993, 3, 97–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Haltiwanger RS; Lowe JB Role of glycosylation in development. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2004, 73, 491–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Varki A Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 3–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rudd PM; Elliott T; Cresswell P; Wilson IA; Dwek RA Glycosylation and the immune system. Science 2001, 291, 2370–2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2) (a).Jones J; Krag SS; Betenbaugh MJ Controlling N-linked glycan site occupancy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1726, 121–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Spiro RG Protein glycosylation: nature, distribution, enzymatic formation, and disease implications of glycopeptide bonds. Glycobiology 2002, 12, 43R–56R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kornfeld R; Kornfeld S Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu. Rev. Biochem 1985, 54, 631–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3) (a).Bertozzi CR; Kiessling LL Chemical glycobiology. Science 2001, 291, 2357–2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Smoot JT; Demchenko AV Oligosaccharide synthesis: from conventional methods to modern expeditious strategies. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem 2009, 62, 161–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Boltje TJ; Buskas T; Boons GJ Opportunities and challenges in synthetic oligosaccharide and glycoconjugate research. Nat. Chem 2009, 1, 611–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ling J; Bennett CS Recent Developments in Stereoselective Chemical Glycosylation. Asian J. Org. Chem 2019, 6, 802–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Agoston K; Streicher H; Fügedi P Orthogonal protecting group strategies in carbohydrate chemistry. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2016, 27, 707–728. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kulkarni SS; Wang CC; Sabbavarapu NM; Podilapu AR; Liao PH; Hung SC One-Pot protection, glycosylation, and protection-glycosylation strategies of carbohydrates. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 8025–8104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4) (a).Li X; Zhu J Glycosylation via Transition‐Metal Catalysis: Challenges and Opportunities. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2016, 28, 4724–4767. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mckay MK; Nguyen HM Recent Advances in Transition Metal-Catalyzed Glycosylation. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 8, 1563–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yu B Gold (I) - catalyzed glycosylation with glycosyl oalkynylbenzoates as donors. Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) cNielsen MM; Pedersen CM Catalytic glycosylations in oligosaccharide synthesis. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 8285–8358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5) (a).Koeller KM; Wong CH Complex carbohydrate synthesis tools for glycobiologists: enzyme-based approach and programmable one-pot strategies. Glycobiology 2000, 10, 1157–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang YH; Ye XS; Zhang LH Oligosaccharide assembly by one-pot multistep strategy. Org. Biomol. Chem 2007, 5, 2189–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu CY; Wong CH Programmable one-pot glycosylation. Top Curr. Chem 2011, 301, 223–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang CC; Lee JC; Luo SY; Kulkarni SS; Huang YW; Lee CC; Chang KL; Hung SC Regioselective one-pot protection of carbohydrates. Nature. 2007, 446, 896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang Z; Ollmann IR; Ye XS; Wischnat R; Baasov T; Wong CH Programmable One-Pot Oligosaccharide Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 734–753. [Google Scholar]

- (6) (a).Sears P; Wong CH Toward automated synthesis of oligosaccharides and glycoproteins. Science. 2001, 291, 2344–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Plante OJ; Palmacci ER; Seeberger PH Automated solid-phase synthesis of oligosaccharides. Science. 2001, 291(5508), 1523–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Seeberger PH Automated oligosaccharide synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2008, 37(1), 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Plante OJ; Palmacci ER; Seeberger PH Development of an automated oligosaccharide synthesizer. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem 2003, 58, 35–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Seeberger PH Automated carbohydrate synthesis to drive chemical glycomics. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2003, 10, 1115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Panza M; Pistorio SG; Stine KJ; Demchenko AV Automated Chemical Oligosaccharide Synthesis: Novel Approach to Traditional Challenges. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118(17), 8105–8150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Joseph AA, Pardo-Vargas A, Seeberger PH. Total Synthesis of Polysaccharides by Automated Glycan Assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 8561–8564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7) (a).Muthana S; Cao H; Chen X Recent progress in chemical and chemoenzymatic synthesis of carbohydrates. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 573–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu H; Chen X One-pot multienzyme (OPME) systems for chemoenzymatic synthesis of carbohydrates. Org. Biomol. Chem 2016, 14(10), 2809–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li W; McArthur JB; Chen X Strategies for chemoenzymatic synthesis of carbohydrates. Carbohydrate Research, 2019, 472, 86–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tsai TI; Lee HY; Chang SH; Wang CH; Tu YC; Lin YC; Hwang DR; Wu CY; Wong CH Effective sugar nucleotide regeneration for the large-scale enzymatic synthesis of Globo H and SSEA4. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 14831–14839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Schmaltz RM; Hanson SR; Wong CH Enzymes in the synthesis of glycoconjugates. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 4259–4307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Cai L Recent progress in enzymatic synthesis of sugar nucleotides. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2012, 31, 535–552. [Google Scholar]; (g) McArthur JB, Chen X. Glycosyltransferase engineering for carbohydrate synthesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans 2016, 44(1), 129–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8) (a).Krasnova L; Wong CH Oligosaccharide synthesis and translational innovation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 3735–3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mastrangeli R; Palinsky W; Bierau H Glycoengineered antibodies: towards the next-generation of immunotherapeutic. Glycobiology. 2019, 29(3), 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Krasnova L; Wong CH Exploring human glycosylation for better therapies. Mol. Aspects. Med 2016, 51, 125–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Krasnova L; Wong CH Understanding the Chemistry and Biology of Glycosylation with Glycan Synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2016, 85, 599–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hsu CH; Hung SC; Wu CY; Wong CH Toward automated oligosaccharide synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 11872–11923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9) (a).Kim JH; Yang H; Park J; Boons GJ A general strategy for stereoselective glycosylations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 12090–12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ranade SC; Demchenko AV Mechanism of chemical glycosylation: focus on the mode of activation and departure of anomeric leaving groups. J. Carbohydr. Chem 2013, 32, 1–43. [Google Scholar]; (c) Handbook of Chemical Glycosylation: Advances in Stereoselectivity and Therapeutic Relevance; Demchenko AV, Ed.; Wiley,V. C. H: Weinheim, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]; (d) Goodman L Neighboring-Group Participation in Sugars. In Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry; Wolfrom ML, Tipson RS, Eds.; Academic Press: 1967; 22, 109–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10) (a).Zhu XM; Schmidt RR New principles for glycoside-bond formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 1900–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zeng Y; Ning J; Kong F Remote control of α- or β-stereoselectivity in (1→3)- glucosylations in the presence of a C-2 ester capable of neighboring-group participation. Carbohydr. Res 2003, 338, 307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zeng Y; Ning J; Kong F Pure α-linked products can be obtained in high yields in glycosylation with glucosyl trichloroacetimidate donors with a C2 ester capable of neighboring group participation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 3729–3733. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Yu H; Williams DL; Ensley HE 4-Acetoxy-2,2-dimethylbutanoate: a useful carbohydrate protecting group for the selective formation of β-(1→3)-D-glucans. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 3417–3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Crich D; Cai F Stereocontrolled glycoside and glycosyl ester synthesis. Neighboring group participation and hydrogenolysis of 3-(2’-Benzyloxyphenyl)-3,3-dimethylpropanoates. Org. Lett 2007, 9, 1613–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ali A; van den Berg R; Overkleeft HS; Filippov DV; van der Marel GA; Codee J Methylsulfonylethoxycarbonyl (Msc) and fluorous propylsulfonylethoxycarbonyl (Fpsc) as hydroxy-protecting groups in carbohydrate chemistry. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 2185–2188. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Daragics K;Fügedi, P. (2-Nitrophenyl) acetyl: A New, Selectively Removable Hydroxyl Protecting Group. Org. Lett 2010, 9, 2076–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Liu H; Zhou SY; Wen GE; Liu XX; Liu DY; Zhang QJ; Schmidt RR; Sun JS The 2,2-Dimethyl-2-(ortho-nitrophenyl) acetyl(DMNPA) Group: A Novel Protecting Group in Carbohydrate Chemistry. Org. Lett 2019, 19, 8049–8052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Yamada T; Takemura K; Yoshida J; Yamago S Dialkylphosphates as stereodirecting protecting groups in oligosaccharide synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2006, 45, 7575–7578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Karak M; Joh Y; Suenaga M; Oishi T; Torikai K 1,2-transGlycosylation via Neighboring Group Participation of 2-O-Alkoxymethyl Groups: Application to One-Pot Oligosaccharide Synthesis. Org. Lett 2019, 4, 1221–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18) (a).Sato T; Joh Y; Oishi T; Torikai K 1-Naphthylmethyl and 1-naphthyl methoxy methyl protecting groups: New members of the benzyl-and benzyloxymethyl-type family. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 23, 2178–2181. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sato T; Oishi T; Torikai K 2-Naphthylmethoxymethyl as a Mildly Introducible and Oxidatively Removable Benzyloxymethyl-Type Protecting Group. Org. Lett 2015, 12, 3110–3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Yasomanee JP; Demchenko AV Effect of remote picolinyl and picoloyl substituents on the stereoselectivity of chemical glycosylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 20097–20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Watson AJA; Alexander SR; Cox DJ; Fairbanks AJ Protecting Group Dependence of Stereochemical Outcome of Glycosylation of 2-O-(Thiophen-2-yl) methyl Ether Protected Glycosyl Donors, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2016, 71, 1520–1532. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hoang KM; Liu XW The intriguing dual-directing effect of 2-cyanobenzyl ether for a highly stereospecific glycosylation reaction. Nat. Commun 2014, 5, 5051.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ding F; Ishiwata A; Ito Y Bimodal Glycosyl Donors Protected by 2-O- (ortho Tosyl -amido) benzyl Group. Org. Lett 2018, 14, 4384–4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23) (a).Kim JH; Yang H; Boons GJ Stereoselective glycosylation reactions with chiral auxiliaries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 947–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Demchenko AV; Rousson E; Boons GJ Stereoselective 1,2-cis-galactosylation assisted by remote neighboring group participation and solvent effects. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 6523–6526. [Google Scholar]; (c) Demchenko AV; Rousson E; Boons GJ Stereoselective 1,2-cis-galactosylation assisted by remote neighboring group participation and solvent effects. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 6523–6526. [Google Scholar]