Abstract

We test the importance of information source on consumer choice in the context of sin goods, specifically electronic and tobacco cigarettes, among adult smokers. We proxy choice with intentions to vape and quit smoking in the next 30 days. We experimentally vary the information source: government, private companies, physicians, and no source. Our findings suggest that information source matters in the context of cigarettes choice for adult smokers. Private companies appear to be an important information source for cigarettes among adult smokers. However, our study may be underpowered, which implies higher chances of type II errors.

Keywords: Information, signaling, choice, sin goods, smoking, electronic cigarettes, experiments

JEL codes: D9, I1

1. Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (‘e-cigarettes’) are battery-operated devices that simulate smoking. The device heats a liquid, which often, but not in all products, contains nicotine – the addictive ingredient in tobacco cigarettes many other tobacco products – and flavors, into a vapor which is inhaled by the user (called ‘vaping’). These products were developed in 2003 (Riker, Lee, Darville, & Hahn, 2012) and are becoming increasingly popular worldwide. In the United States, the focus of our study, 4.7% of adults regularly used e-cigarettes in 2016, which implies nearly 11 million Americans used these products regularly in that year, and 22.1% of adults had ever used these products (Hu et al., 2019). U.S. e-cigarette sales totaled $3.4B in 2018 and are predicted to reach $6.6B in 2024 (Mordor Intelligence, 2019).

E-cigarette use has progressed in a largely unregulated environment and there is controversy regarding the health effects of these products. On the one hand, e-cigarettes are generally believed to be less detrimental to health than tobacco cigarettes for smokers and non-smokers, and may assist some smokers in quitting (Bullen et al., 2013; Hajek, Etter, Benowitz, Eissenberg, & McRobbie, 2014; Dinakar & O’Connor, 2016; Shahab et al., 2017; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2018; Hajek et al., 2019). Indeed, the U.S. Surgeon General has officially stated that while e-cigarettes are not harmless, these products generally contain fewer toxicants than tobacco cigarettes (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). The potential for harm reduction – that is addicted smokers who cannot quit tobacco products can consume nicotine in a less harmful manner – and cessation could be important. Indeed, despite numerous anti-smoking campaigns, tax increases, and use bans over several decades, 14% of U.S. adults continue to smoke (Wang et al., 2018) and 68% of smokers state that they wish to quit, but cannot (Babb, 2017). Alternatively, there are concerns among some public health advocates that e-cigarettes may re-normalize smoking, help smokers circumvent indoor smoking bans, that the health benefits of e-cigarettes are over-stated, and that e-cigarettes themselves are harmful (Zhong, Cao, Gong, Fei, & Wang, 2016; McKee & Capewell, 2015; Allen et al., 2016; Shi, Cummins, & Zhu, 2017; Scott et al., 2018; Reidel et al., 2018).

Faced with this controversy, governments in many countries are determining whether and how to establish e-cigarette policies and, in particular, communication strategies on the risks of e-cigarettes. At the state and municipality levels within the U.S., there are a range of policies applied to e-cigarette use, including taxation, prohibition for youth, banning their use in bars, restaurants, schools, and worksites (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Some localities have gone further. For example, in 2019 San Francisco became the first locality in the U.S. to fully ban the sale of e-cigarettes, interestingly tobacco cigarettes remain legal.1 At the federal level the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) expanded its ‘Real Cost’ youth anti-smoking campaign, initiated in 2014, to include e-cigarettes in 2018. However, some researchers criticize the FDA, and other public health agencies within the U.S., for acknowledging that tobacco products pose dissimilar health risks but not differentiating these risks in communication strategies and instead focusing on the risk of using any tobacco product (Kozlowski & Sweanor, 2016). Such researchers further contend that this approach leaves communication of risk differences between tobacco products to private agents. At the same time, e-cigarette companies spend millions of dollars each year advertising these products to consumers; e.g., in 2014 these companies spent over $115M on advertising and this number is escalating (Cantrell, Emelle, Ganz, Hair, & Vallone, 2016). Tobacco cigarette companies are increasingly entering the e-cigarette market (Kamerow, 2013; Tobacco Tactics.org, 2020) which suggests that advertising efforts may become even more aggressive in the future. Recent data show that an increasing proportion of U.S adults have misconceptions about the harmfulness of e-cigarettes and that risk perceptions are associated with product use (Viscusi, 2016; Czoli, Fong, Mays, & Hammond, 2017). This confluence of factors suggests that there is substantial scope for communication efforts, public or private, to shape the demand for e-cigarettes.

Understanding how consumers incorporate information related to cigarette risk is important to inform government policies related to these products, and to understand how advertising from private companies may influence consumer demand. Clinical research suggests that key reasons for quitting smoking and initiating vaping relate to consumer concerns that tobacco cigarettes are harmful to health and that e-cigarettes are the less harmful product (Hyland et al., 2004; Farsalinos, Romagna, Tsiapras, Kyrzopoulos, & Voudris, 2014). Further, theory suggests the source of information, independent of the content, plays a role in consumer decisions (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008; Oullier, Cialdini, Thaler, & Mullainathan, 2010; Dolan et al., 2012). This question is potentially of particular importance in markets in transition such as the tobacco product market. Thus, while we focus on a specific market, cigarettes, our findings may offer insight to other contexts characterized by uncertainty within the scientific community and aggressive advertising.

We provide the first evidence on whether and how information source affects adult smokers’ intentions to use e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes. Given the rapid growth of the e-cigarette market, the potential costs and benefits of increased e-cigarette use, and communication efforts by both public and private agents, studying this question is important from a policy, health, and economic perspective. We take an experimental approach in which we present adult smokers with cigarette health information. We vary the information source and compare 30-day intentions to use e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes in the various experimental arms. Our experimental approach ensures that treatment exposure is exogenous, which is difficult to credibly establish in observational data. We select three plausible information sources: government (which we proxy with the FDA, the federal agency with the authority to regulate tobacco products in the U.S.), private companies (which we proxy with a fictitious e-cigarette company), and physicians (an important source of health information generally and of smoking information specifically, which we proxy with a generic image of a group of physicians). We compare each to a no source control.

We elect to focus on intentions to vape and smoke, rather than actual tobacco product use behaviors as the latter construct is challenging to measure in our experimental data.2 Further, intentions capture the first step in a causal chain of tobacco product use; e.g., in theories of behavioral change (in particular tobacco product use), the consumer initially makes a decision to change their behavior – akin to the intentions that we measure in our work – and then, at a later time, makes a plan to change the behavior, changes the behavior, and then maintains the modified behavior and, in some cases, addresses relapse (Prochaska, DiClemente, Velicer, Ginpil, & Norcross, 1985; Prochaska, Velicer, DiClemente, & Fava, 1988; DiClemente et al., 1991). Therefore, intentions to use are important and interesting in their own right. Further, understanding the importance of information in the initial stages of behavior change is crucial for examining the role of information throughout the behavior change process. Given that we establish the importance of information at the initial stage in the note causal change, future work could explore the importance of information in later stages (e.g., planning, actual behavior change, maintenance, and relapse).

Our findings imply an important role for information source in how consumers incorporate information into decision making about cigarettes. Private companies appear to have a substantial influence on smokers’ intention to use e-cigarettes, but not tobacco cigarettes. Information from the government appears to be of limited importance.

2. Background

There is a large literature that crosses several scholarly disciplines on information and decision-making under uncertainty. We focus on health information uncertainty in our study. Consumers who receive health messages face some uncertainty regarding the quality of the message, and therefore whether and how to use this in decision-making about their health. Given the relative newness of e-cigarettes in tobacco markets and misconceptions regarding their risks (Viscusi, 2016), consumers may disproportionately rely on health messages. Some consumers may look to signals to help them discriminate between high and low quality health information. For instance, consumers can view the source of information as a signal of quality, independent of the information content. Indeed, numerous scholarly fields (e.g., communications, economics, finance, marketing, medicine, political science, and psychology) have examined the importance of information source. Sources that are viewed as trustworthy, likeable, an authority, or knowledgeable are presumed to provide higher quality information than other sources (Hovland & Weiss, 1951; Fragale & Heath, 2004; Pornpitakpan, 2004; Hovland & Weiss, 1951; Fragale & Heath, 2004; Pornpitakpan, 2004; Dolan et al., 2012). Further, the congruency between the information content and source is important (Becker-Olsen, Cudmore, & Hill, 2006). For example, if the consumer views the information and source to be a good ‘fit’ (e.g., a public health organization communicating a health-related message), the consumer is more likely to find the information credible and believable.

Karlan and List (2012), for example, document that charitable donations are larger when the donation solicitation is linked to a perceived authority figure (e.g., Bill and Melinda Gates, prominent U.S. philanthropists). Meer (2011) shows that university donations are larger when an alumni (which proxies for similarities in background) requests a donation than an otherwise comparable individual. Boddery and Yates (2014) document that shared political affiliation is important for individuals’ probability of agreeing with U.S. Supreme Court decisions. Readers are more likely to report concern about local crime after reading an article on this topic published in a more credible vs. less credible newspaper (Koomen, Visser, & Stapel, 2000). Finally, in a recent experimental study, economists are more likely to report that they agree with a policy-related statement when the source is a mainstream vs. non-mainstream (e.g., heterodox or Austrian school) economist (Javdani & Chang, 2019).

Of relevance to our work, a previous communications study examines the importance of information source within the context of smoking cessation products (not e-cigarettes or tobacco cigarettes per se). Byrne, Guillory, Mathios, Avery, and Hart (2012) show that smoking cessation advertisements where the source is a public health organization are viewed as more credible and more effective than the same advertisement where the source is a tobacco company. Further, while not capturing information source, we note that smokers believe that tobacco cigarettes labeled as ‘light’ are less harmful than tobacco cigarettes without such a label, although the clinical literature clearly establishes that there is no difference in health harms across the two products (Kozlowski et al., 1998; Wilson et al., 2009).

In sum, the literature to date suggests the importance of information source, independent of message, for consumer choice. However, the effect of our selected information sources (the FDA, a fictitious e-cigarette company, and physicians), relative to a no-source control, is ex ante unclear. On the one hand, we hypothesize that information from the FDA will have a greater effect on consumer intention to use than information provided with no source as the FDA will be perceived as an authority figure. However, if the FDA is viewed as a direct arm of the government, rather than an independent scientific agency, this source may be viewed as less credible and thus have a muted effect on consumer choice. This behavior may be particularly important as, during our study period, there was a growing wave of anti-government and anti-science sentiment (American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2018). Of note, this sentiment has persisted to the time of writing in the U.S. and other countries.3 Further, because consumers will view these agents has having an agenda (selling e-cigarettes), information from an e-cigarette company will have no effect, relative to information provided with no source, on intentions to use tobacco products. However, this hypothesis may not hold if consumers view e-cigarette companies as offering addicted smokers an appealing and possibly effective cessation device. Finally, physicians are important sources of health information, in particular for tobacco product-related information (Hesse et al., 2005).

Given the ambiguity, we will test the empirical importance of these sources using an experimental design. Finally, because e-cigarettes are new and controversial products while tobacco cigarettes are established products with widely known health harms, we suspect that information source will be more important for e-cigarettes than for tobacco cigarettes.

3. Data, variables, and methods

3.1. Data

We focus on adult smokers as this is the group at at greatest risk for health problems associated with smoking and reducing smoking in this group is likely to have a substantial effect on public health (Levy et al., 2017). Data were collected through an online platform by the survey firm Qualtrics on adults 18 to 64 years who reported current smoking between April 6th, 2017 and May 26th, 2017. This survey platform is commonly used by economists to study health-related outcomes, including cigarettes (Bradford, Courtemanche, Heutel, McAlvanah, & Ruhm, 2017; Marti, Buckell, Maclean, & Sindelar, 2018; Buckell, Marti, & Sindelar, 2018; Buckell & Sindelar, 2019a; Elías, Lacetera, & Macis, 2019).

We constructed our sample to match a sample of adult smokers in the 2014 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). At the time of survey development, the 2014 BRFSS was the most recent year of this data set available. The BRFSS is a large national and state representative health survey conducted annually, and is used within economics to study smoking (Courtemanche & Zapata, 2014; Horn, Maclean, & Strain, 2017). We matched our sample to BRFSS on sex, age (18 to 34, 35 to 49, and 50 to 64 years), education (less than a college degree and a college degree or more), and region (New England, Mid-Atlantic, Midwest, South, Mountain, and Pacific). Our full survey instrument, including the exact wording of all items used in our analysis, is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

We conducted an experiment in which we varied the information source of cigarette risk information and then compared outcomes across the experimental arms. We included three information sources: the FDA, a fictitious e-cigarette company developed by the authors for the purposes of this study (called the ‘Ave’), and generic physicians. Cigarette risk information provided with no source served as the control group. We choose these sources as they are important economic agents in the e-cigarette market and/or common sources of health information. For instance, the FDA is the federal government agency within the U.S. that has the authority to regulate e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes while e-cigarette companies manufacture, sell, and market e-cigarettes. Physicians are a common source of health information for many consumers and plausibly discuss tobacco product use with patients who vape or smoke as office-based screening and consultation is recommended by many health organizations. For example, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force lists talking to adult smokers about cessation and recommended cessation products as a Grade A service: ‘The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial’ (Force, 2009; Siu, 2015). Ideally, we would have included a broader set of sources (e.g, medical organizations), but we were unable to secure permission from such organizations. Using a likeness without stated permission is illegal.4 We received permission from the FDA. We operationalized the information source with an image.

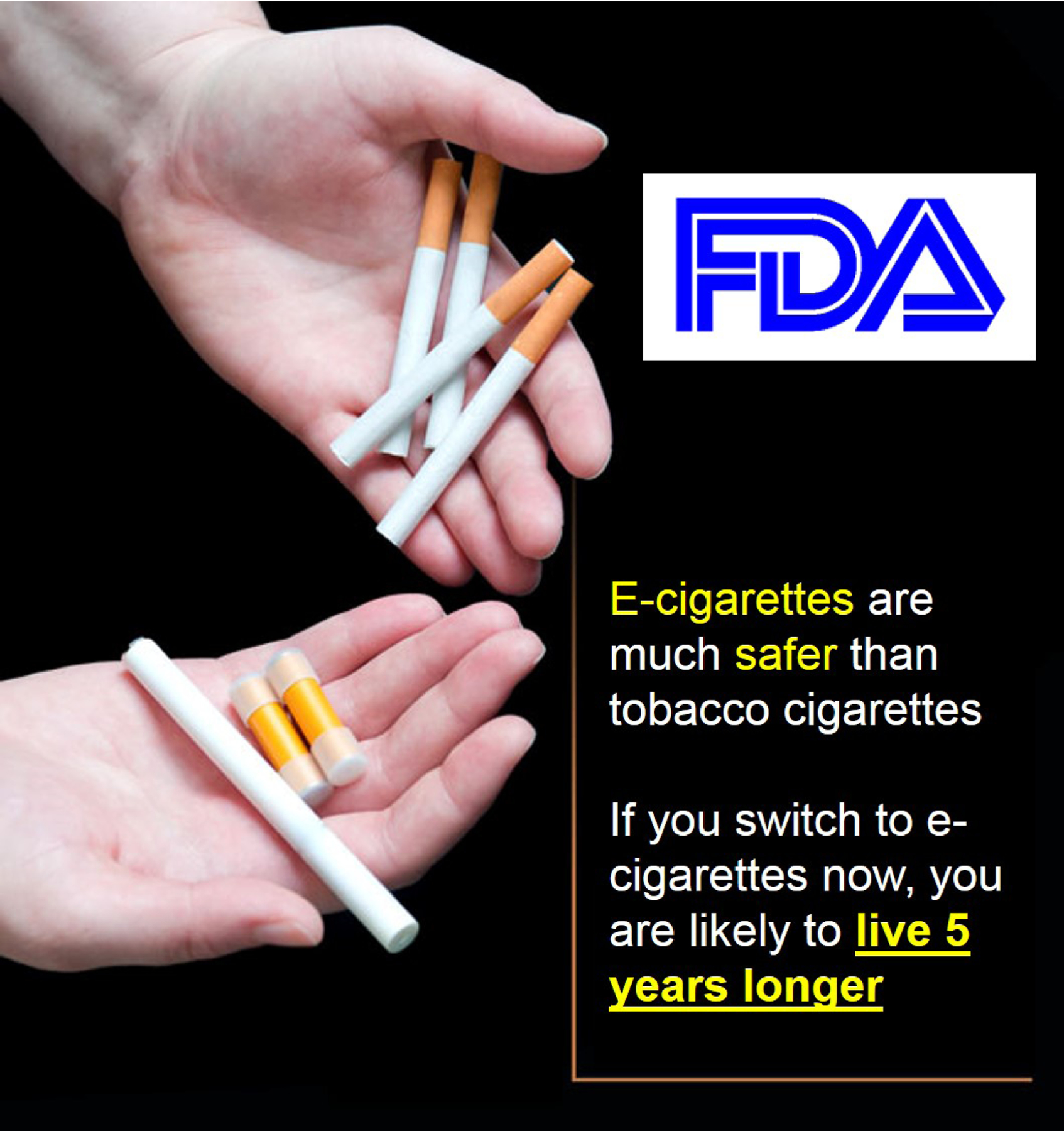

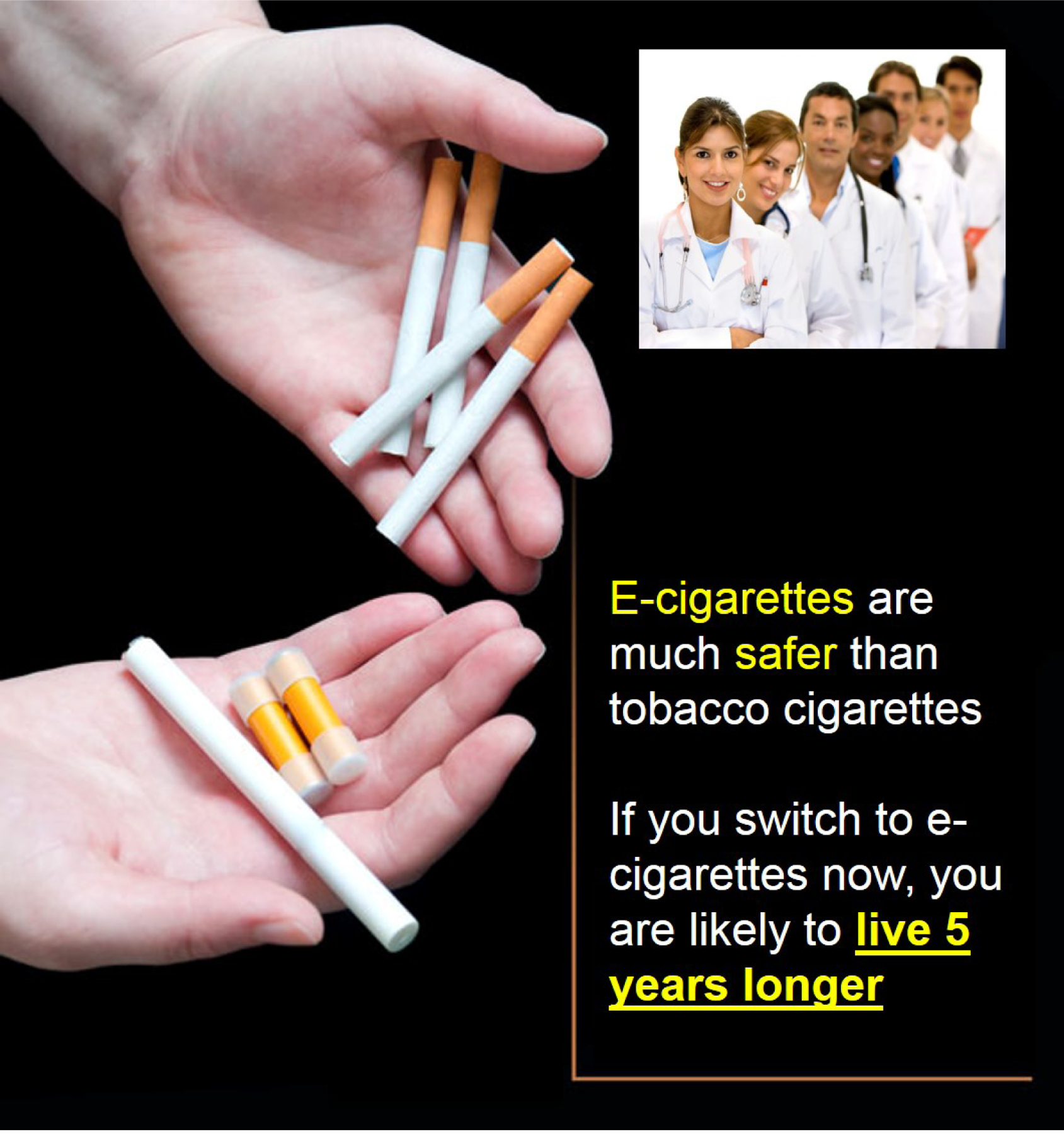

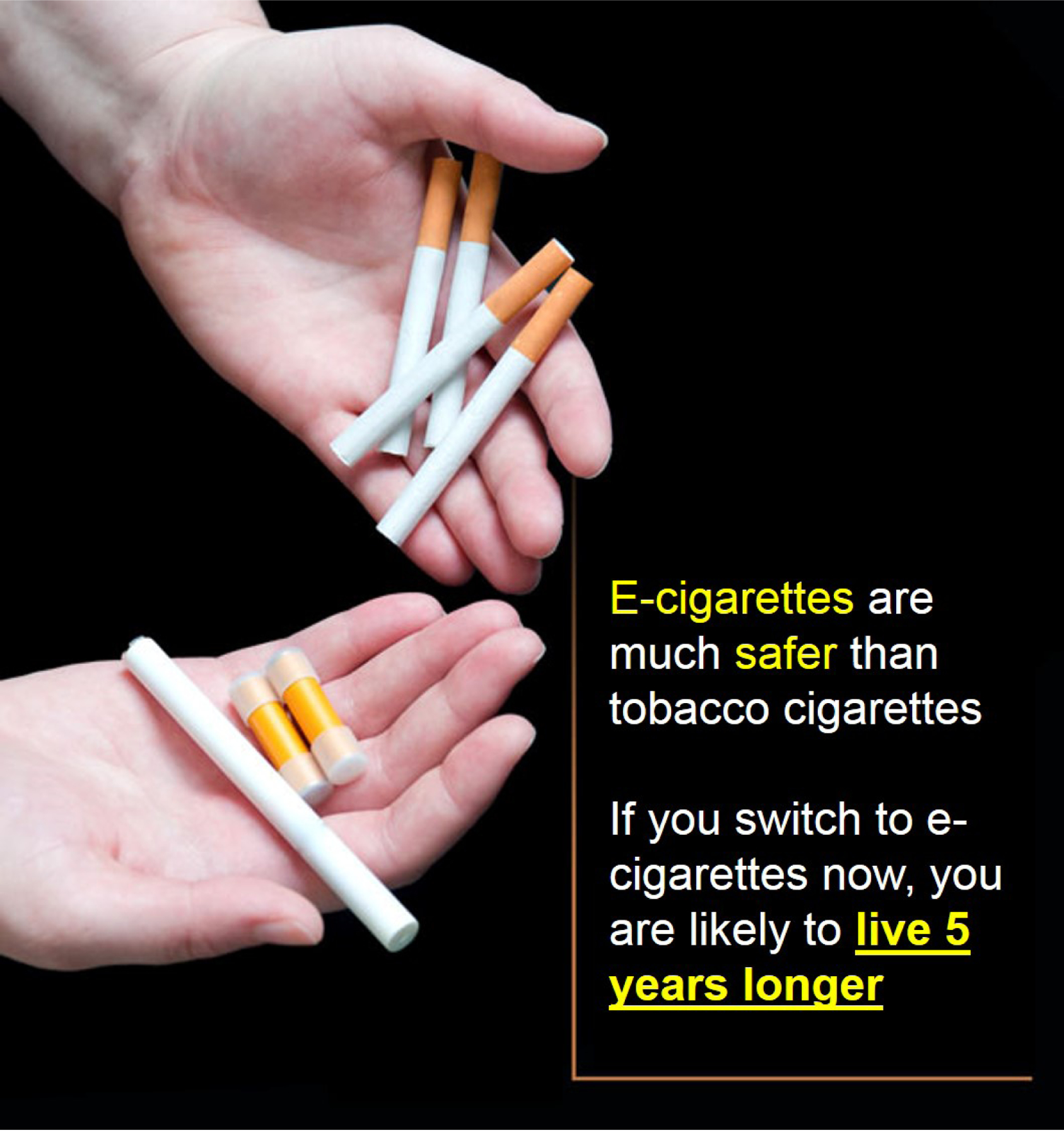

Respondents were randomized to one of four sources and were shown the corresponding image and were asked to view the image. The survey paused for 30 seconds to encourage viewing. Respondents could continue to view the image beyond this time period. Each picture had an image of two hands holding e-cigarettes in the right hand and tobacco cigarettes in the left hand. We altered the information source by using different logos. The source logo (e.g., FDA) was placed in the upper right hand corner of each image. The information conveyed to smokers related to the relative health harms of e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes: ‘E-cigarettes are much safer than tobacco cigarettes. If you switch to e-cigarettes now, you are likely to live five years longer’ or ‘Tobacco cigarettes are much more harmful than e-cigarettes. If you don’t switch to e-cigarettes now, you are likely to die five years earlier.’5 Figures 1 to 4 present the images shown to respondents with the change in health status associated with a transition to e-cigarettes as a health gain. We note that e-cigarettes – similar to many other products for sale in the marketplace – have changed over time in terms of structure and other attributes (Glantz & Bareham, 2018). However, the image that we use in our study is comparable to many e-cigarettes on the market and consumed by adults (the focus of our study) at the time of survey development (2016 to early 2017). Figure 5 depicts an e-cigarette from this time period. Further, this form of e-cigarette was included in the Surgeon General’s 2016 report on youth vaping (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016), see Figure 1.1 in the report.

Figure 1:

FDA as the information source

Figure 5:

E-cigarette at the time of survey

We selected life expectancy as this outcome is a relatively easy to understand and objective health metric, and is used within economics (Viscusi, 2016). Determining the changes in life expectancy associated with switching from tobacco cigarettes to e-cigarettes was not straightforward. There is general consensus that e-cigarettes are the safer product; as noted earlier in the manuscript the U.S. Surgeon General has officially stated that, while both products are harmful to health, e-cigarettes generally contain fewer toxicants than tobacco cigarettes (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). This official statement was made by the Surgeon General before our survey was implemented. Further, prior to our study a well-published report from Public Health England stated that e-cigarettes were 95% less harmful than tobacco cigarettes (Public Health England, 2015) and NHS Health Scotland released a consensus statement on e-cigarettes supported by numerous universities and healthcare professionals stating ‘E-cigarettes are definitely less harmful than smoking tobacco cigarettes’ (NHS Health Scotland, 2017). Supporting this argument, a recent systematic review finds conclusive evidence that fully switching from tobacco cigarettes to e-cigarettes reduces smokers’ exposure to numerous toxicants and carcinogens (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018). We selected a five year change in life expectancy as we deemed it plausible based on available clinical evidence at the time of our survey. For instance, cessation between ages 25 to 54 increases life-expectancy by six to ten years (Jha et al., 2013). However, we acknowledge that our measure is not ideal.

Prior to the survey, we conducted a 50-person pilot study. We asked respondents to note any issues related to the viewing the images and/or any other problems with the survey. Further, we had several research assistants complete the survey and report any problems, and had the survey reviewed by Qualtrics programmers. We incorporated feedback to improve our survey. In particular, no pilot respondent, research assistant, or Qualtrics programmer noted any issues with the life expectancy measure, and we specifically asked these individuals whether the life expectancy question was problematic. This survey was deemed not human subjects and thus exempt from IRB review by both Yale University and Temple University.

Our sample included 2,722 currently smoking adults 18 to 64 years. We excluded several respondents to improve data quality. We asked respondents ‘How hard did you find it to understand the image you viewed?’ Response categories were: not difficult at all, not very difficult, somewhat difficult, and extremely difficult. Respondents who found the image extremely difficult to understand were excluded. We placed an attention test in the middle of the survey: we asked respondents to select the number two (options one and two) with the two placed farthest to the right (Krosnick, 1991). Respondents who failed this attention test were excluded. We also excluded respondents who completed the survey in less than 1/3 of the median survey time. Qualtrics recommends this practice in all online surveys as this is an industry standard. Our analysis sample included 2,499 adults (or 92% of the full sample).6 This sample is large relative to other online experiments (Pesko, Kenkel, Wang, & Hughes, 2016; Bradford et al., 2017; Marti et al., 2018; Kenkel, Peng, Pesko, & Wang, 2017; Buckell et al., 2018; Buckell & Sindelar, 2019a).7 We conducted a post hoc power analysis. Our minimum detectable effect size at α=0.05 80% of the time is 6 ppts.

3.2. Variables

Our outcome variables were measured immediately following image viewing, and included questions on intentions to use e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes. These variables are established proxies for cigarette use and are grounded in the theory of behavior change (Prochaska et al., 1985, 1988; Ajzen, 1991; DiClemente et al., 1991; Godin & Kok, 1996; Harakeh, Scholte, Vermulst, de Vries, & Engels, 2004; Rise, Kovac, Kraft, & Moan, 2008; Kleinjan et al., 2009; Czoli et al., 2017). We asked respondents about their perceived likelihood of using e-cigarettes in the following 30 days. We constructed an indicator for reporting being extremely or somewhat likely to use e-cigarettes in the next 30 days, and zero otherwise. Analogously, we constructed an indicator for the likelihood of quitting tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days. These two variables proxy intentions to use e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes, but we note that these measures do not capture actual use of these products. We explicitly chose to study intentions, rather than use, as tracking respondents over a sufficient time period that would capture changes in use in a highly addictive product (e.g., six months or a year) is challenging when using the Qualtrics research panel as panel members cycle in and out of the panel. Further, before examining actual changes in behavior, our goal was to study the ‘first stage’ in the causal change from information to actual behavioral change: intentions. We view our study as the first in a potential series of studies that examine the role of information. Thus, testing the importance of information in the initial stage of change is necessary and independently important and interesting.

We elected to focus on measures of any e-cigarette use, rather than intensity of use, for simplicity as the point of our study was to test whether information matters in the context of cigarettes. Further, one can view our measures as the first link in a chain of events leading from information receipt to potential change in vaping and/or smoking. We adopted a forced response approach (Carson et al., 1994).

3.3. Methods

As we randomized respondents to treatments, we can compare outcome proportions across arms. However, we apply a linear probability model (LPM) that controls for personal characteristics to allow us to reduce residual variation in our outcomes and increase statistical power (Angrist & Pischke, 2009). Equation 1 outlines our regression model:

| (1) |

Ci,s is a cigarette outcome for respondent i assigned to information source s. We include fixed effects for the source; no source is the reference. Xi,s is a vector of demographic variables based on information we collected in a post-experiment survey. More specifically, sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, region, family size, political affiliation, survey duration (this variable measures the entire time between survey initiation and completion; some respondents did not complete the survey in one sitting), reporting that the image was somewhat hard to understand,8 excellent or very good self-assessed health, daily smoking, nicotine addiction (proxied by the number of minutes between waking up and first tobacco cigarette (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991); this measure pertains to smoking, not vaping, and all respondents in the sample, regardless of vaping status, smoke tobacco cigarettes at the time of the survey, and current vaping. We also control for whether or not the respondent was exposed to the gain frame (vs. loss frame) message. We impute the mean/mode for observations with missing control variable information and include indicators for missingness to maximize statistical power.

µi,s is the error term. Heteroscedasticity robust standard errors are reported. We randomize our treatment across respondents, thus we follow recent literature and do not cluster at the treatment level (Abadie, Athey, Imbens, & Wooldridge, 2017).

4. Results

4.1. Summary statistics

Table 1 reports summary statistics. We assess balance across arms following Kruskal and Wallis (1952). We reject the null hypothesis of no difference in mean rank across arms (p<0.05) in two of twenty-six variables (8.3%): Pacific region (p-value = 0.0038) and South region (p-value = 0.0258). However, the magnitudes of these differences are small.

Table 1:

Summary statistics

| Source: | All | FDA | Doctor | Ave | No source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 34 years | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.40 |

| 35 to 49 years | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.30 |

| 50 to 64 years | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.30 |

| Male | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.55 |

| Female | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.45 |

| No college | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.58 |

| College | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.42 |

| Mid Atlantic | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| Midwest | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| Mountain | 0.064 | 0.057 | 0.064 | 0.056 | 0.080 |

| New England | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.038 |

| Pacific | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.098 | 0.096 |

| South | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.42 |

| White | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.83 |

| African American | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.100 | 0.093 |

| Other race | 0.082 | 0.092 | 0.074 | 0.085 | 0.077 |

| Hispanic | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.089 |

| Family size | 3.05 | 3.02 | 3.02 | 3.04 | 3.12 |

| Democrat | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.53 |

| Survey duration | 14311.5 | 18775.5 | 12162.7 | 10243.6 | 15989.7 |

| Image somewhat hard to understand | 0.068 | 0.073 | 0.077 | 0.064 | 0.056 |

| Excellent/very good health | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| Daily smoker | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.86 |

| Addicted smoker | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.32 |

| Vaper | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.22 |

| Gain (vs. loss) | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Observations | 2,499 | 630 | 622 | 621 | 626 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. Image difficulty = Respondent reports some trouble understanding the image. SAH = Respondent assesses her health as excellent or very good. Addicted smoker = Respondent smokes her first tobacco cigarette within five minutes of waking up.

We asked respondents questions related to knowledge of our sources (Table 2). 96% report that they are familiar with the FDA, 18% report that they have heard of the fictitious e-cigarette company, and 80% report having a doctor. There are more than 460 unique e-cigarette companies operating in the U.S. with eleven new companies emerging each month (Zhu et al., 2014). Familiarity with the fictitious e-cigarette company is not surprising, consumers are potentially mistaking our fictitious company with a real company. Familiarity with the sources is balanced across experimental arms (p-value < 0.05).

Table 2:

Familiarity with information sources

| Source | All | FDA | Doctor | Ave | No source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heard of FDA | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

| Heard of Ave | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Have a doctor | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| Observations | 2,499 | 630 | 622 | 621 | 626 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study.

4.2. Main results

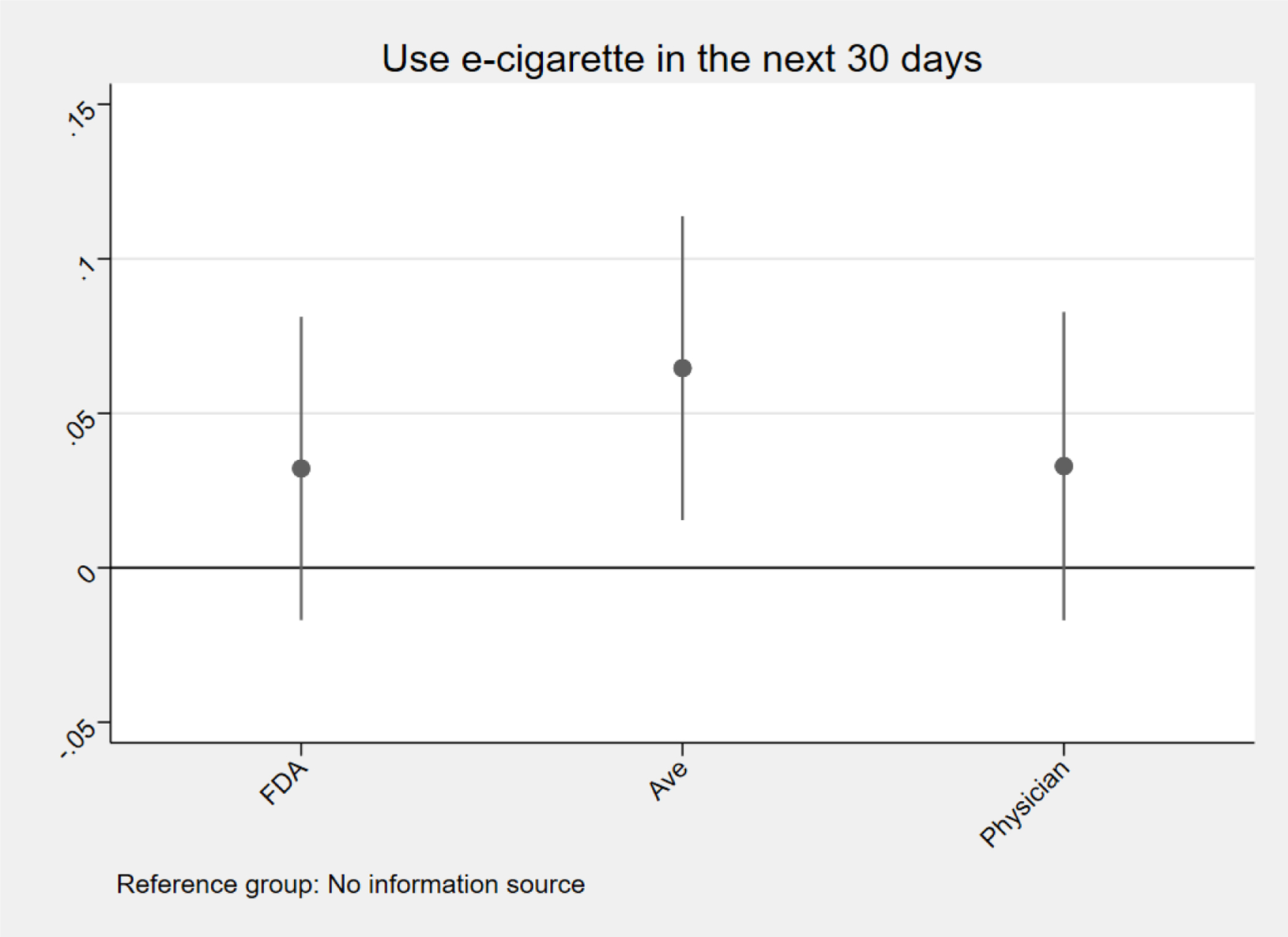

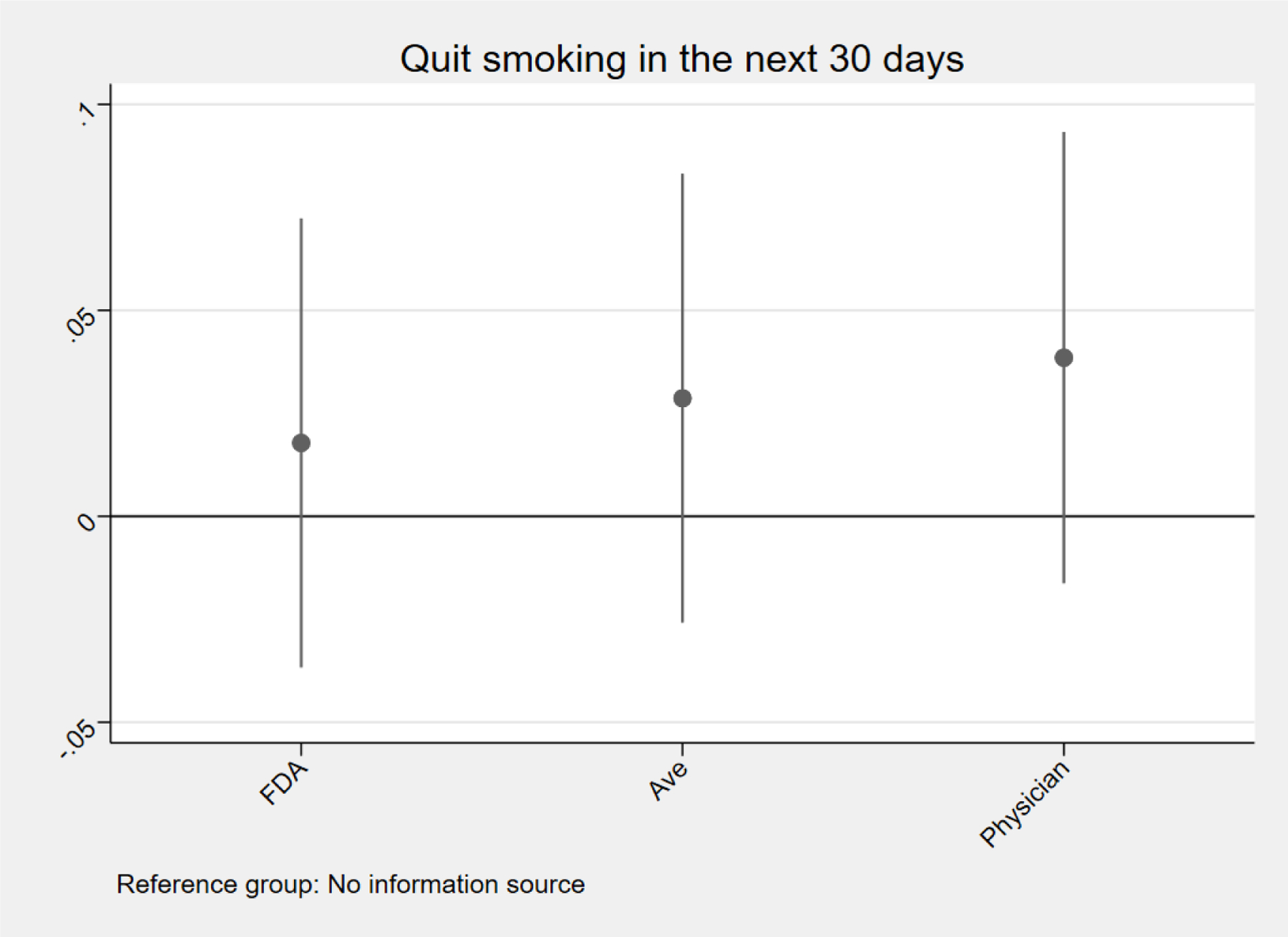

Results for the effects of information source on intentions to use cigarettes and risk perceptions are reported in Tables 3. We report unadjusted (top panel) and adjusted (bottom panel) regression results. In addition, the adjusted regression results are reported graphically in Figures 6 and 7.

Table 3:

Effect of information sources on e-cigarette and tobacco cigarette use

| Outcome variable: | Use e-cigarette in next 30 days | Quit tobacco cigarettes in next 30 days |

|---|---|---|

| Sample proportion: | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| No controls | ||

| FDA | 0.032 (0.028) |

0.024 (0.028) |

| Ave | 0.080*** (0.028) |

0.038 (0.028) |

| Physician | 0.026 (0.028) |

0.042 (0.028) |

| Controls | ||

| FDA | 0.032 (0.025) |

0.018 (0.028) |

| Ave | 0.065** (0.025) |

0.029 (0.028) |

| Physician | 0.033 (0.025) |

0.039 (0.028) |

| Observations | 2,499 | 2,499 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM. Outcome variables coded one if the respondent reports being extremely likely or somewhat likely to use an e-cigarette/quit tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days, and zero otherwise. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

Figure 6:

Effect of information sources on e-cigarette use

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM. Outcome variables coded one if the respondent reports being extremely likely or somewhat likely to use an e-cigarette/quit tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days, and zero otherwise. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Circles reflect the coefficient estimate and vertical lines reflect 95% confidence intervals based on heteroskedasticy robust standard errors.

Figure 7:

Effect of information sources on tobacco cigarette use

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM. Outcome variables coded one if the respondent reports being extremely likely or somewhat likely to use an e-cigarette/quit tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days, and zero otherwise. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Circles reflect the coefficient estimate and vertical lines reflect 95% confidence intervals based on heteroskedasticy robust standard errors.

52% of the sample plans to use an e-cigarette and 54% plans to quit tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days. We observe that receiving information from the fictitious e-cigarette company increases the probability of reporting an intention to use e-cigarettes in the next 30 days. In particular, we observe that information from the fictitious e-cigarette company raises intentions to use e-cigarettes by 8.0 percentage points (ppts) in the unadjusted model and 6.5 ppts in the adjusted model. Relative the sample proportion these estimates imply a 15% and 13% increase in intentions to use e-cigarettes (all relative effects are calculated compared to the relevant sample proportions throughout the manuscript). We observe no other statistically significant relationships. We suspect that the null findings for use of tobacco cigarettes are due to the fact that these products are not new to the U.S. market and their health harms are well known to smokers, on the other hand e-cigarettes are relatively new products and the literature on the harms of these products is heavily debated within the public health community (Viscusi, 2016).

For brevity, we report covariate-adjusted results only for the remainder of the paper. Unadjusted results are similar and available on request.

4.3. Relevance of the study

Our experiment was conducted in Spring 2017 and the U.S. tobacco product market has changed since that time. Thus, a reasonable question is whether our findings remain informative given these changes. We contend that our findings are relevant for several reasons. We discuss the relevance of our broader research question first and, second, the relevance for the specific question of cigarettes.

First, while we focus on cigarettes (electronic and tobacco) our primary research question is ‘Does information source, independent of the specific message, matter for consumer choice in the context of sin goods?’ This question, we contend, is useful in its own right and we provide evidence that source does appear to matter. We fully acknowledge that the specific source that is salient to consumers likely varies across sin goods (e.g., tobacco products, alcohol, food, illicit drugs). Further, the salient source may vary across populations within product (e.g, youth vs. adults) and for different margins of choice (e.g., initiation vs. cessation). Indeed, we believe that this heterogeneity is likely given differences in markets, products, consumers, and so forth. Our study addresses a dearth in the literature. We hope that our study leads to future studies that explore this question in different settings.

Second, and specific to cigarettes, we argue that our findings remain informative for the importance of consumer choice of e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes. We review several important concepts to assess whether changes may have occurred that would imply that our findings are no longer relevant.

(1) Perceptions of the relative health risks among adult smokers and vapers, the focus of our study, have been relatively stable since the time of our study and the current time period (Huang et al., 2019; Nyman, Huang, Weaver, & Eriksen, 2019). The health risks of tobacco cigarettes have been well-established for decades (US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1964). Further, the share of adults using e-cigarettes has been stable. Between 2016 and 2018, the rate of e-cigarette use among adults ages 18 and older was 3.2% (2016), 2.8% (2017), and 3.2% (2018) (Dai & Leventhal, 2019), suggesting that there has not been substantial compositional shift. Thus, we see no reason to believe that our findings should not be informative for the current cohort of adult smokers and vapers.

(2) A particularly important population in relation to e-cigarettes is youth. We note that between the time of our survey and the time of writing that youth vaping has increased to a nontrivial degree (Gentzke et al., 2019). Further, vaping rates have been higher among youth than other group since vaping has been recorded in U.S. surveys (Dai & Leventhal, 2019; Gentzke et al., 2019). Public health concerns regarding e-cigarette use among youth were known at the time of our survey as they are at the time of writing. For instance, in 2016 the U.S. Surgeon General, the leading health authority in the U.S., released a well-published report explicitly on the dangers of youth vaping (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Thus, youth vaping has been a major concern before, during, and after our study period. We see no reason why a continued trend in youth vaping and common knowledge that youth vaping is a major health concern should render our findings irrelevant. We fully acknowledge that, if we were focusing on youth, the increases in vaping within this population would be a major concern for the relevance of our study, but we do not study youth in our analysis, our sample includes those 18 to 64 years of age. To dig more deeply into this question, we exclude the youngest members of our sample (those less than 22 years of age) and re-estimate Equation 1. Results (reported in Table 4) are not appreciably different from our main findings.

Table 4:

Effect of information sources on e-cigarette and tobacco cigarette use: Drop respondents under age 22

| Outcome variable: | Use e-cigarette in next 30 days | Quit tobacco cigarettes in next 30 days |

|---|---|---|

| Sample proportion: | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| FDA | 0.017 (0.026) |

0.019 (0.029) |

| Ave | 0.056** (0.026) |

0.024 (0.029) |

| Physician | 0.029 (0.026) |

0.047 (0.029) |

| Observations | 2,330 | 2,330 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM. Outcome variables coded one if the respondent reports being extremely likely or somewhat likely to use an e-cigarette/quit tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days, and zero otherwise. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

(3) There have been no changes in the importance of the FDA or physicians of which we are aware. For example, the FDA was the federal administration with the authority to regulate e-cigarettes at the time of our survey and remains so today. Physicians where an important source of tobacco product health information at the time of our survey and this continues. For instance, the United States Preventive Task Services has listed tobacco product counseling by physicians in healthcare appointments as a Grade A service since the 2000s (Force, 2009; Siu, 2015) and there has been no meaningful change in the share of Americans 18 years and older with a healthcare professional visit in the past year between 2017 and 2018 (National Health Interview Survey, 2020).9

(4) Another possible concern is that there have been changes in the supply side of the e-cigarette market. An important aspect of the supply side is the participation of Big Tobacco (large tobacco cigarette manufacturing companies). However, all of the large American tobacco companies (Altria, Lorillard, and Reynolds) had entered the U.S. market by 2014 (Kamerow, 2013; Tobacco Tactics.org, 2020). While Big Tobacco has continued to expand its presence in the U.S. e-cigarette market (e.g., in 2018 Altria acquired a 35% stake in JUUL, the current market leader), this trend began before our study period and has continued since that time should not influence the usefulness of our findings.

(5) One may be concerned that the e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) outbreak that occurred in the U.S. in 2019 may have raised concerns about the safety of e-cigarettes among adult smokers and vapers. At the time of writing, there have been 2,807 cases of EVALI reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with 68 confirmed deaths, mainly among adults (King, Jones, Baldwin, & Briss, 2020). However, this specific increase in concerns regarding the safety of e-cigarettes was short-lived as the public health community and media quickly reported that EVALI deaths were largely related to improper use of the product or tampering of the product, in particular users adding tetrahydrocannabinol and/or vitamin E acetate to the product, which is not recommended by commercial manufacturers (Blount et al., 2020; Chidambaram et al., 2020; Rao et al., 2020). Both the CDC and the FDA recommend against using vaping products that contain tetrahydrocannabinol and/or vitamin E acetate as a precaution to avoid EVALI.10. Further, un-tampered products may appear relatively safe by comparison. A recent study by Dave, Dench, Kenkel, Mathios, and Wang (2020) supports the short duration of a change in perceptions of safety and the relative appeal of correctly used products. Thus, we do not see any evidence that EVALI, which can be viewed as short period of mis-information regarding the health harms of e-cigarettes for adult users, should impact the relevance of our work.11

In sum, while we acknowledge that there have been changes over the time period since our survey was deployed, given the central question we are asking and the population we study, we contend that our findings are relevant. Finally, we note that using non-real time data is the norm within health economic studies that investigate e-cigarette use, see, for example, Buckell and Sindelar (2019b) and Pesko, Courtemanche, and Maclean (2020).

4.4. Robustness checking

Our results are broadly stable across several different robustness checks. Reassuringly the coefficient estimate are extremely stable in terms of sign, magnitude, and statistical significance across all specifications. For brevity, we summarize our analysis.

We apply linear probability models in our main analysis. Our outcome variables are binary and therefore arguably more appropriately modeled with a specification that respects the non-continuous nature of these variables. We estimate logit models and report average marginal effects (Table 5). In our main analysis we impute the mean and mode for observations with missing information. We exclude observations with any missing information on the control variables; n=121. Results are reported in Table 5.

Table 5:

Effect of information sources on e-cigarette and tobacco cigarette use: Alternative specifications and samples

| Outcome variable: | Use e-cigarette in next 30 days | Quit tobacco cigarettes in next 30 days |

|---|---|---|

| Use a logit model | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| FDA | 0.031 (0.025) |

0.018 (0.028) |

| Ave | 0.063** (0.025) |

0.029 (0.027) |

| Physician | 0.033 (0.025) |

0.039 (0.028) |

| Observations | 2,499 | 2,499 |

| Exclude observations with missing controls | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.53 | 0.54 |

| FDA | 0.035 (0.026) |

0.015 (0.029) |

| Ave | 0.061** (0.026) |

0.025 (0.028) |

| Physician | 0.030 (0.026) |

0.027 (0.029) |

| Observations | 2,378 | 2,378 |

| Exclude observations reporting that they have heard of the Ave | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.47 | 0.51 |

| FDA | 0.042 (0.028) |

0.033 (0.031) |

| Ave | 0.069** (0.027) |

0.043 (0.031) |

| Physician | 0.041 (0.028) |

0.064** (0.031) |

| Observations | 2,053 | 2,053 |

| Control for information source familiarity | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.47 | 0.51 |

| FDA | 0.027 (0.025) |

0.008 (0.028) |

| Ave | 0.063** (0.025) |

0.029 (0.028) |

| Physician | 0.030 (0.025) |

0.033 (0.028) |

| Observations | 2,499 | 2,499 |

| Exclude respondents who find the Ave somewhat or very trustworthy | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.36 | 0.45 |

| FDA | 0.042 (0.029) |

0.034 (0.035) |

| Ave | 0.088*** (0.030) |

0.043 (0.035) |

| Physician | 0.030 (0.030) |

0.060* (0.035) |

| Observations | 1,577 | 1,577 |

| Exclude respondents with extreme survey duration | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| FDA | 0.039 (0.027) |

0.014 (0.030) |

| Ave | 0.070*** (0.026) |

0.029 (0.029) |

| Physician | 0.045* (0.027) |

0.048 (0.029) |

| Observations | 2,253 | 2,253 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM unless otherwise noted. Average marginal effects reported in logit model. Extreme survey duration = duration < 5th percentile or > 95th percentile of the distribution. Outcome variables coded one if the respondent reports being extremely likely or somewhat likely to use an e-cigarette/quit tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days, and zero25 otherwise. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

We drop 446 respondents (18%) from the sample who report having heard of the fictitious e-cigarette company (Table 5). In this sample, we observe that receiving information from physicians (vs. no source) increases the probability of intended to quit smoking in the next 30 days by 6.4 ppts (13%). We control for source familiarity (Table 5). We drop all respondents who report that they find the fictitious e-cigarette company somewhat or very trustworthy, n=922, and report results in Table 5. In this sample, receiving information from physicians (vs. no source) increases the probability of intending to quit smoking in the next 30 days by 6.4 ppts (13%). We note that excluding respondents who are familiar with the fictitious e-cigarette company and/or find this source trustworthy reveals a stronger role for physicians. While clearly conjecture, we note the possibility that such respondents may distrust the medical community. Future work could explore this hypothesis more formally. We exclude respondents with survey duration below the 5th percentile and above the 95th percentile of the empirical distribution. Results are listed in Table 5.

4.5. Extensions

We next use more information contained in our outcomes to better understand the importance of information. That is we leverage the fact that we have four possible responses and we re-estimate Equation 1 using an ordered logit model. Results are reported in Tables A1 and A2. We convert beta coefficients to average marginal effects. The general pattern of results that we observed in our main specifications holds when we use an ordered logit. In particular, receiving information from the fictitious e-cigarette company appears to shift intentions to use e-cigarettes from the two bottom categories toward the two top categories, this pattern of results is fully in line with our main findings.

Given the importance of the fictitious e-cigarette company in our study, we wish to dig deeper into the type of respondent who finds the fictitious e-cigarette company a credible information source. As we noted earlier in the manuscript, there are over 460 e-cigarette companies operating in the U.S. (Zhu et al., 2014) and respondents in our sample who report familiarity with the fictitious company may simply be mistaking it with another (real) e-cigarette company. We separate respondents into those who report finding the fictitious e-cigarette company somewhat or very trustworthy and those who do not. We then examine demographics for these groups. Results are reported in Table A3. Members of these groups appear to be broadly similar across age, gender, education, region, race, ethnicity, family size, political affiliation, and smoking. For instance, 57% of the group that finds the fictitious e-cigarette company somewhat or very trustworthy is male and 55% of the group that does not find the fictitious e-cigarette company trustworthy is male. There are non-trivial differences across groups in terms of survey duration, difficulty viewing the image, self-assessed health, and vaping. Average survey duration is 9,716 seconds, 9% have some difficulty viewing the image, 32% report their health as excellent or very good, and 35% are current vapers among those who find the fictitious e-cigarette company somewhat or very trustworthy. In the sample that does not find the fictitious e-cigarette company trustworthy these values are 16,998 seconds, 5.5%, 24%, and 16%. In unreported analysis, we conducted two-tailed t-tests for continuous variables and differences in proportion tests for binary variables. Differences between the two groups are often statistically different from zero (available on request).

We next assess two potential mechanisms. We expect that information source, if consumers view source as a proxy for information quality, to be correlated with accuracy. We proxy accuracy with two questions posed to respondents after viewing the images: (i) ‘How trustworthy do you find the image? By trustworthy, we mean do you trust that the information in this image is accurate?’ and (ii) ‘To what extent is the image in the interest of Americans’ health?’ We constructed two binary indicators for finding the image somewhat or very (i) trustworthy and (ii) in the interest of American’s health. Results are reported in Table A4. We observe that information from the fictitious e-cigarette company is more likely to be viewed as somewhat/very trustworthy (6.6 ppts or 11%). We find no evidence that any other source (relative to no source) had an impact on our proxies for quality.

One interpretation of these results is that those who reported that they found the fictitious e-cigarette company trustworthy had more difficulty with the survey and spent less time answering questions. Because we had various research assistants and programmers at Qualtrics complete our survey, conducted a pilot study, and excluded those respondents who had a great deal of difficulty with the image, failed our attention test, or spent very little time completing the survey, we do not suspect that a problematic survey can fully explain our findings. We note, in real-world markets, that many individuals exposed to information do not spend adequate time focusing on the communicated information and have difficulty understanding information (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Such consumers may be particularly influenced by communication efforts by private companies. Alternatively, those who reported finding the fictitious e-cigarette company trustworthy were more likely to vape (35% vs. 16%). Vapers plausibly find e-cigarettes a valuable product, as evidenced by their consumption of the product, and view all e-cigarette manufacturers favorably. Further, our finding that information received from the fictitious e-cigarette company is viewed as more trustworthy (relative to no source) supports the concept that our sample of smokers (and vapers) find e-cigarette companies a helpful source of information in this context.

As another approach to gauge the extent to which source of information may influence consumer choice, we examine four additional variables that may capture smokers’ risk perceptions of e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes, and preferences regarding government intervention in tobacco markets to reduce use of e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes. In particular, we develop indicator variables that are coded one (and zero otherwise) for strongly agreeing or agreeing with the following four statements: (i) e-cigarettes are healthier than tobacco cigarettes, (ii) people who switch from tobacco cigarettes to e-cigarettes are healthier, (iii) the government should encourage people to switch from using tobacco cigarettes to using e-cigarettes, and (iv) the government should ban the sale of e-cigarettes. In our sample 62% agree that e-cigarettes are healthier than tobacco cigarettes, 58% agree that switching to e-cigarettes from tobacco cigarettes will improve health, 47% agree that the government should promote switching to e-cigarettes, and 20% agree that the government should ban e-cigarettes. We observe that receiving information from the fictitious e-cigarette company has a statistically significant effect on the probability of agreeing with our risk perception variables. In particular, information from the fictitious e-cigarette company (vs. no source) increases the probability of agreeing that e-cigarettes are healthier than tobacco cigarettes by 7.1 ppts (11%) and increases the probability of agreeing that switching to e-cigarettes will improve health by 5.2 ppts (9%), and decreases the probability of agreeing that the government should ban e-cigarettes by 4.3 ppts (22%) (Table A5). No other coefficient estimates are statistically different from zero.

Finally, we explore heterogeneity in our estimated treatment effects. To this end, we stratify the sample along several variables and estimate Equation 1 in the sub-samples. In particular, we consider heterogeneity by vaping status (vaper vs. non-vaper), age (18 to 39 years vs. 40 to 64 years), and frame (gain vs. loss frame). Results are reported in Tables A6 (vaping status), A7 (age), and A8 (frame). The propensity to report likely use of an e-cigarette in the next 30 days is greater among both vapers and non-vapers if this information is received from the fictitious e-cigarette company relative to no source, while the absolute effect sizes are similar (6.3 ppts among vapers and 6.0 ppts among non-vapers) the relative effect sizes are more substantial among non-vapers (15%) than vapers (7%) given baseline differences in the proportion that intends to use e-cigarettes in the next 30 days (40% of non-vapers and 92% of vapers). Our full sample effects appear to be driven by younger adults (18 to 39 years): coefficient estimates are only statistically distinguishable from zero in that sample. Further, receiving information from the fictitious e-cigarette company (vs. no source) increases the propensity to use e-cigarettes and to quit smoking (8.9 ppts or 15% and 9.6 ppts or 17% respectively) within this sample. We also see that among younger adults, receiving information from the FDA increases the probability of intending to use an e-cigarette by 6.0 ppts (10%). Stratifying the sample by gain vs. loss framing shows that information received from the fictitious e-cigarette company (vs. no source) increases the probability of using an e-cigarette in the next 30 days in both samples: 6.3 ppts (12%) in the gain frame sample and 6.9 ppts (13%) in the loss sample. Interestingly, within the loss frame sample, other sources of information appear to be empirically important for intentions to vape and smoke in the next 30 days (relative to no source): receiving information from the FDA leads to a 7.1 ppt (14%) increase in 30-day intention to vape and an 8.2 ppt (15%) increase in the 30-day intention to quit smoking.

5. Discussion

We provide experimental evidence on the importance of information source to consumers in influencing intention to use e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to study this question. While we focus on one product, cigarettes, our findings may apply to other settings where there is a new product (such as e-cigarettes) and/or the entry of a related good may change demand for an existing good (such as the case of tobacco cigarettes). In particular, our findings may offer insight when there is uncertainty within the scientific community regarding the health risks associated with a new product.

Theory suggests a role for information and our findings provide strong support for this prediction in the context of cigarettes. In particular, private companies, proxied in our study by a fictitious e-cigarette company, appear to be important information sources for adult smokers. On the other hand, information provided by government agencies does not have a discernible effect on intentions to use and risk perceptions versus a no information source control. These findings have important implications for governments attempting to develop communication strategies related to cigarettes and other products in which there is uncertainty regarding the products and aggressive advertising of the product by private agents. In addition to developing the message of the campaign, the selection of the information source, the conveyer of the information, is potentially important.

The generally null findings for a government agency (the FDA) and physicians as information sources run counter to our hypotheses. In particular, ex ante we expected that information received from these sources – who we hypothesized would be viewed as authorities able to provide credible information by respondents – would influence consumers’ intentions to use cigarettes and risk perceptions relative to a no source control. In general, our findings did not support these hypotheses. We suspect that some respondents may not have interpreted the associated image as capturing physicians, and instead viewed the image as representing healthcare workers generally who may, as a group, not be viewed as authorities in the context of the relative risk of e-cigarettes and tobacco cigarettes, diluting effects. As noted, we were not able to secure permission to use the logo of a medical organization in the U.S. for our survey and using a logo without permission is illegal.

The importance of a fictitious e-cigarette company that we document deserves some discussion. While we cannot test the reasons why this information source appears to be important for adult smokers we can propose possible explanations. First, congruence between the information source (an e-cigarette company) and the follow-up questions (intentions to use cigarettes and risk perceptions of these products) may play a role (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006). Respondents may expect cigarette questions after viewing an image of an e-cigarette company but may not have this expectation if they are presented with a different image. Second, respondents may simply have found the fictitious e-cigarette company image appealing, credible, or important for other intangible reasons. Finally, there are hundreds of unique e-cigarette companies in the U.S. tobacco product market (Zhu et al., 2014) and smokers in our sample may simply confuse the fictitious company for another, real, company.

We note that, while the studies apply different identification strategies, our findings are in line with Dave, Dench, Grossman, Kenkel, and Saffer (2018) who find no evidence that e-cigarette magazine advertising influences quitting behavior among U.S. adult smokers. The authors do provide evidence that exposure to television e-cigarette advertising may prompt some smokers to quit smoking. However, we believe the images in our experiment are more reflective of a magazine advertising campaign rather than a television advertising campaign.

Our study has limitations. We use an online sample and the generalizability of our findings to other populations is unclear. We do not study product use and rely on proxies. We are not able to study all relevant factors that are important for consumer cigarette choices in a single experiment. Similarly, we likely do not capture all important sources of information for adult smokers. We use a fictitious e-cigarette company, findings may differ if we had used an established producer of e-cigarettes, future work could consider this question. Some of our observed effect sizes are smaller in magnitude than our minimum detectable effect based on a power analysis. We do not study youth, which is clearly an economically and policy relevant group.

These findings suggest that subtle differences in message presentation can lead to different outcomes. As has been documented in the context of tobacco cigarettes (Avery, Kenkel, Lillard, & Mathios, 2007), our results suggest an important role for private companies in shaping the trajectory of e-cigarette use. Future work could consider the importance of information source in the context of other sin goods such as alcohol and unhealthy foods, and potentially re-visit this question in a future time period to assess whether effects change.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2:

The fictitious e-cigarette company (the Ave) as the information source

Figure 3:

Physicians as the source

Figure 4:

No information source

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number P50DA036151 from the NIDA and FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration. We thank Paul Allison, Andrew Barnes, Stefan Boes, Laura Gibson, Robert Hornik, Melissa Oney, Kurt Petschke, Jody Sindelar, Janice Vincent, and Douglas Webber, and especially Joachim Marti for helpful feedback. All errors are our own.

Appendix

Table A1:

Effect of information sources on intentions to use e-cigarettes using an ordered logit model

| Outcome variable: | Not very likely at all | Not very likely | Somewhat likely | Extremely likely |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample proportion: | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.17 |

| FDA | −0.025 (0.019) |

−0.003 (0.003) |

0.013 (0.010) |

0.015 (0.011) |

| Ave | −0.040** (0.019) |

−0.005** (0.003) |

0.022** (0.010) |

0.024** (0.012) |

| Physician | −0.013 (0.019) |

−0.002 (0.003) |

0.007 (0.010) |

0.008 (0.011) |

| Observations | 2,499 | 2,499 | 2,499 | 2,499 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an ordered logit model. Average marginal effects reported. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

Table A2:

Effect of information sources on intentions to quit tobacco cigarettes using an ordered logit model

| Outcome variable: | Not very likely at all | Not very likely | Somewhat likely | Extremely likely |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample proportion: | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.16 |

| FDA | −0.020 (0.015) |

−0.012 (0.009) |

0.014 (0.010) |

0.018 (0.013) |

| Ave | −0.009 (0.016) |

−0.005 (0.009) |

0.006 (0.011) |

0.008 (0.014) |

| Physician | −0.019 (0.016) |

−0.011 (0.009) |

0.013 (0.011) |

0.017 (0.014) |

| Observations | 2,499 | 2,499 | 2,499 | 2,499 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an ordered logit model. Average marginal effects reported. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

Table A3:

Characteristics of respondents who find the fictitious e-cigarette company somewhat or extremely trustworthy and respondents who do not

| Sample: | Find the Ave trustworthy | Do not find the Ave trustworthy |

|---|---|---|

| 18 to 34 years | 0.37 | 0.37 |

| 35 to 49 years | 0.33 | 0.28 |

| 50 to 64 years | 0.30 | 0.34 |

| Male | 0.57 | 0.55 |

| Female | 0.43 | 0.45 |

| No college | 0.57 | 0.59 |

| College | 0.43 | 0.41 |

| Mid Atlantic | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| Midwest | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| Mountain | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| New England | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Pacific | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| South | 0.42 | 0.40 |

| White | 0.79 | 0.83 |

| African American | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| Other race | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Hispanic | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Family size | 3.10 | 3.02 |

| Democrat-leaning | 0.55 | 0.53 |

| Survey duration | 9,716 | 16,998 |

| Image difficulty | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| SAH | 0.32 | 0.24 |

| Daily smoker | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| Addicted smoker | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| Vaper | 0.35 | 0.16 |

| Gain | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Observations | 922 | 1,577 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. Image difficulty = Respondent reports some trouble understanding the image. SAH = Respondent assesses her health as excellent or very good. Addicted smoker = Respondent smokes her first tobacco cigarette within five minutes of waking up.

Table A4:

Effect of information sources on proxies for source accuracy

| Outcome variable: | Trustworthy | Interest of Americans’ health | Hard to understand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample proportion: | 0.58 | 0.73 | 0.07 |

| FDA | 0.043 (0.028) |

0.026 (0.025) |

0.017 (0.014) |

| Ave | 0.066** (0.028) |

0.023 (0.025) |

0.009 (0.013) |

| Physician | 0.031 (0.028) |

0.006 (0.025) |

0.021 (0.014) |

| Observations | 2,499 | 2,499 | 2,499 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM. Average marginal effects reported. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

Table A5:

Effect of information sources on e-cigarette and tobacco cigarette risk perceptions

| Outcome variable: | E-cigarettes healthier than tobacco cigarettes | Switching from tobacco cigarettes to e-cigarettes improves health | Government should promote switching to e-cigarettes | Government should ban e-cigarettes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample proportion: | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.20 |

| FDA | 0.039 (0.027) |

0.043 (0.027) |

0.033 (0.027) |

−0.011 (0.023) |

| Ave | 0.071*** (0.027) |

0.052* (0.027) |

0.019 (0.027) |

−0.043* (0.022) |

| Physician | 0.008 (0.027) |

0.020 (0.027) |

0.014 (0.027) |

−0.007 (0.023) |

| Observations | 2,499 | 2,499 | 2,499 | 2,499 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM. Outcome variable is coded one if the respondent reports agreeing strongly or agreeing with the particular cigarette belief question, and zero otherwise. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

Table A6:

Effect of information sources on e-cigarette and tobacco cigarette use: Heterogeneity by vaping status

| Outcome variable: | Use e-cigarette in next 30 days | Quit tobacco cigarettes in next 30 days |

|---|---|---|

| Vapers | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.92 | 0.63 |

| FDA | −0.002 (0.036) |

0.001 (0.060) |

| Ave | 0.063* (0.033) |

0.065 (0.058) |

| Physician | −0.002 (0.038) |

−0.007 (0.061) |

| Observations | 573 | 573 |

| Non-vapers | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.40 | 0.51 |

| FDA | 0.035 (0.031) |

0.018 (0.032) |

| Ave | 0.060* (0.031) |

0.015 (0.032) |

| Physician | 0.042 (0.031) |

0.052 (0.032) |

| Observations | 1,926 | 1,926 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM. Outcome variables coded one if the respondent reports being extremely likely or somewhat likely to use an e-cigarette/quit tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days, and zero otherwise. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

Table A7:

Effect of information sources on e-cigarette and tobacco cigarette use: Heterogeneity by age

| Outcome variable: | Use e-cigarette in next 30 days | Quit tobacco cigarettes in next 30 days |

|---|---|---|

| 18 to 39 years | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.58 | 0.57 |

| FDA | 0.060* (0.036) |

0.048 (0.039) |

| Ave | 0.089** (0.035) |

0.096** (0.039) |

| Physician | 0.037 (0.036) |

0.055 (0.039) |

| Observations | 1,258 | 1,258 |

| 40 to 64 years | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| FDA | 0.007 (0.035) |

−0.007 (0.040) |

| Ave | 0.038 (0.036) |

−0.038 (0.040) |

| Physician | 0.024 (0.036) |

0.021 (0.040) |

| Observations | 1,241 | 1,241 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM. Outcome variables coded one if the respondent reports being extremely likely or somewhat likely to use an e-cigarette/quit tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days, and zero otherwise. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

Table A8:

Effect of information sources on e-cigarette and tobacco cigarette use: Heterogeneity by gain vs. loss frame

| Outcome variable: | Use e-cigarette in next 30 days | Quit tobacco cigarettes in next 30 days |

|---|---|---|

| Gain frame | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| FDA | −0.006 (0.036) |

−0.050 (0.039) |

| Ave | 0.063* (0.037) |

−0.035 (0.040) |

| Physician | 0.016 (0.037) |

0.016 (0.040) |

| Observations | 1,253 | 1,253 |

| Loss frame | ||

| Sample proportion: | 0.52 | 0.55 |

| FDA | 0.071** (0.036) |

0.082** (0.040) |

| Ave | 0.069** (0.035) |

0.092** (0.039) |

| Physician | 0.051 (0.035) |

0.060 (0.039) |

| Observations | 1,246 | 1,246 |

Notes: The Ave is the fictitious e-cigarette company created by the authors for the purposes of this study. All models estimated with an LPM. Outcome variables coded one if the respondent reports being extremely likely or somewhat likely to use an e-cigarette/quit tobacco cigarettes in the next 30 days, and zero otherwise. Controls include personal characteristics listed in Table 1. Reference category is no source. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

= statistically different from zero at the 1%,5%,10% level.

Footnotes

Please see https://www.cnbc.com/2019/06/25/san-francisco-bans-e-cigarette-sales-becoming-the-first-city-to-do-so.html (last accessed June 3rd, 2020).

In particular, as we note later in the manuscript, we rely on experimental data from the survey firm Qualtrics. Members of the Qualtrics research panel rotate in and out of the survey at a high rate, thus tracking the same respondents over time is challenging. Full details available on request.

For instance, please see the following news stories (all last accessed on June 3rd, 2020): https://www.physiciansweekly.com/the-growth-in-magic-anti-science-behavior-is-on-the-rise-gaining-ground/; https://www.rawstory.com/2020/01/veteran-newsman-dan-rather-nails-republicans-for-being-anti-science-while-a-global-health-crisis-looms/; https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/16/nyregion/nj-vaccinations-religious-exemption.html; and https://qz.com/1706261/the-anti-vax-movement-is-reversing-decades-of-scientific-progress/.

We confirmed this fact with a lawyer who works in the area of intellectual property rights. Because we could not secure permission to use a professional medical organization as our physician source, we relied on a generic image of physicians.

We selected the verb ‘switch’ as the definition of this word in all major dictionaries of which we are aware is clear: transiting from one action to another. See for example: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/switch (last accessed June 3rd, 2020). Thus, we expect that respondents interpreted ‘switch’ to imply quitting tobacco cigarettes and initiating e-cigarette use (or for dual users in our sample, continuing to use only e-cigarettes). However, we note that, as is the case in any survey, some respondents could have interpreted this term differently.

In unreported analysis (available on request) we find no evidence of differences across survey arms in terms of respondents who were and where not excluded from the sample for finding the image difficult to view, failing the attention test, or speeding through the survey.

We acknowledge that the e-cigarette regulation landscape in the U.S. has changed to some extent since the time of our survey. For example, as of 2018, all e-cigarettes that contain nicotine must include a warning that the product contains this ingredient and that nicotine is harmful to health. Such changes would be common across all four arms of our experiment and thus should not lead to bias. Further, not all e-cigarettes contain nicotine. More broadly, it is generally not feasible to conduct economic studies in real time and there is a large tradition in empirical economics to leverage ‘historical’, i.e. not real time, data to test economic predictions and inform policy. While we acknowledge that exactly mimicking the current regulatory landscape is ideal in any setting, we do not believe that there is any evidence that changes that have occurred after our study was fielded would influence our ability to study the importance of information source, which is the point of our study. Finally, to the best of our knowledge, the generalizability of any experiment to the real-world is somewhat unclear due to the, by design, artificial experimental setting.

Recall that we exclude respondents who report that the image was very hard to understand.

Authors’ analysis of the National Center for Health Statistics Data, more recent data are not available at the time of writing.

Please see the CDC website (https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html) and the FDA website (https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/lung-injuries-associated-use-vaping-products). Both websites were last accessed on June 3rd, 2020.

Further, any of the noted changes in adult use, youth use, companies supplying e-cigarettes, and EVALI should impact all four arms equally. We know of no reason why these changes should interact with our sources of information (FDA, fictitious e-cigarette company, physicians, and no source).

Contributor Information

Johanna Catherine Maclean, Department of Economics, Temple University, & NBER & IZA, 1301 Cecil B. Moore Avenue, Ritter Annex 869, Philadelphia PA, USA.

John Buckell, Health Economics Research Centre, Nuffield Department of Population Health and Health Behaviours, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, University of Oxford.

References

- Abadie A, Athey S, Imbens GW, & Wooldridge J (2017). When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? (Tech. Rep. No. 24003). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JG, Flanigan SS, LeBlanc M, Vallarino J, MacNaughton P, Stewart JH, & Christiani DC (2016). Flavoring chemicals in e-cigarettes: diacetyl, 2, 3-pentanedione, and acetoin in a sample of 51 products, including fruit-, candy-, and cocktail-flavored e-cigarettes. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(6), 733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences. (2018). The Public Face of Science: Perceptions of Science in America (Tech. Rep.) American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved from https://www.amacad.org/content/publications/publication.aspx?d=43055 [Google Scholar]

- Angrist JD, & Pischke J-S (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Avery R, Kenkel D, Lillard DR, & Mathios A (2007). Private profits and public health: Does advertising of smoking cessation products encourage smokers to quit? Journal of Political Economy, 115(3), 447–481. [Google Scholar]

- Babb S (2017). Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Olsen KL, Cudmore BA, & Hill RP (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, Morel-Espinosa M, Valentin-Blasini L, Gardner M, … others (2020). Vitamin e acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with evali. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(8), 697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddery SS, & Yates J (2014). Do policy messengers matter? Majority opinion writers as policy cues in public agreement with Supreme Court decisions. Political Research Quarterly, 67(4), 851–863. [Google Scholar]