ABSTRACT

Background: COVID-19 deaths elevate the prevalence of prolonged grief and post-traumatic stress symptoms among the bereaved, yet few studies have examined potential positive outcomes. Moreover, how COVID-19 bereavement affects individual-level mental health outcomes is under-researched.

Objective: This is the first study to use latent profile analysis (LPA) to identify heterogeneous profiles of prolonged grief, post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth among people bereaved due to COVID-19 and to identify predictors of latent class membership.

Methods: Four hundred and twenty-two Chinese participants who were bereaved due to COVID-19 completed an online survey between September and October 2020. The survey included the International (ICD-11) Prolonged Grief Disorder Scale (IPGDS), the Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) and the Post-traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI). LPA was run in Mplus, and the 3-step auxiliary approach was used to test the predicting effects of potential predictors of latent class membership identified with chi-square tests and ANOVAs.

Results: Four latent profiles were identified: resilience (10.7%), growth (20.1%), moderate-combined (42.2%) and high-combined (27.0%). The bereaved who shared a close relationship with the deceased and identified COVID-19 as the fundamental cause of death were more likely to be in the high-combined group. A conflictful bereaved-deceased relationship reduces the chance of being in the growth group. Moreover, the death of a younger person and loss of a partner attributed to maladaptive outcomes.

Conclusions: Serious attention needs to be paid to the mental health issues of people bereaved due to COVID-19 because nearly 70% of this group would have a moderate-combined or high-combined symptom profile. Special care should be given to those who lost someone younger, lost a partner or shared a close relationship with the deceased. Grief therapies that work on the conflicts between the deceased and the bereaved and unfinished business can be applied to facilitate growth.

KEYWORDS: Prolonged grief, post-traumatic stress, post-traumatic growth, latent profile analysis, COVID-19

HIGHLIGHTS

Four latent profiles of prolonged grief, post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth were unveiled among 422 Chinese participants bereaved due to COVID-19 who were investigated online between September and October 2020: resilience, growth, moderate-combined and high-combined.

Short abstract

Antecedentes: Las muertes por COVID-19 elevan la prevalencia de síntomas de duelo prolongado y estrés postraumático entre las personas en duelo, sin embargo, pocos estudios han examinado los posibles resultados positivos. Además, la forma en que el duelo por COVID-19 afecta los resultados de salud mental a nivel individual está poco investigada.

Objetivo: Este es el primer estudio que utiliza el análisis de perfil latente (LPA) para identificar perfiles heterogéneos de duelo prolongado, estrés postraumático y crecimiento postraumático entre personas en duelo debido al COVID-19 y para identificar predictores de pertenencia a una clase latente.

Métodos: Cuatrocientos veintidós participantes chinos que estaban en duelo debido a COVID-19 completaron una encuesta en línea entre septiembre y octubre de 2020. La encuesta incluyó la Escala Internacional de Trastorno por Duelo Prolongado (ICD-11) (IPGDS), la Lista de verificación de trastornos por estrés para el DSM-5 (PCL-5) y el Inventario de crecimiento postraumático (PTGI). Se ejecutó LPA en Mplus y se usó el enfoque auxiliar de 3 pasos para probar los efectos de concordancia de posibles predictores de pertenencia a una clase latente identificados con pruebas de chi-cuadrado y ANOVA.

Resultados: Se identificaron cuatro perfiles latentes: resiliencia (10,7%), crecimiento (20,1%), combinado moderado (42,2%) y combinado alto (27,0%). Los deudos que compartían una relación cercana con el fallecido e identificaron al COVID-19 como la causa fundamental de muerte tenían más probabilidades de estar en el grupo de alta combinación. Una relación conflictiva con el fallecido reduce la posibilidad de estar en el grupo de crecimiento. Además, la muerte de una persona más joven y la pérdida de una pareja se asocian a resultados desadaptativos.

Conclusiones: Se debe prestar mucha atención a los problemas de salud mental de las personas en duelo debido a COVID-19 porque casi el 70% de este grupo tendría un perfil de síntomas combinados moderados o combinados altos. Se debe prestar especial atención a quienes perdieron a alguien más joven, perdieron a una pareja o tuvieron una relación cercana con el fallecido. Las terapias de duelo que trabajan en los conflictos entre el fallecido y los deudos y en temáticas no resueltas, se pueden aplicar para facilitar el crecimiento.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Duelo prolongado, Estrés postraumático, Crecimiento postraumático, Análisis de perfil latente, COVID-19

Short abstract

背景: COVID-19 死亡增加了丧亲者的延长哀伤和创伤后应激症状的流行率, 但很少有研究考查潜在的积极结果。此外, 对 COVID-19 丧亲如何影响个体层面心理健康结果的研究不足。

目的: 这是第一项使用潜在剖面分析 (LPA) 来确定因 COVID-19 丧亲者的延长哀伤, 创伤后应激和创伤后成长的异质剖面并确定潜在类别成员的预测因素的研究。

方法: 422 名因 COVID-19 丧亲的中国参与者在 2020 年 9 月至 10 月期间完成了一项在线调查。该调查包括国际 (ICD-11) 延长哀伤障碍量表 (IPGDS), DSM-5创伤后应激障碍检查表 (PCL-5) 和创伤后成长量表 (PTGI) 。在 Mplus 中运行LPA, 并使用 3 步辅助方法来检验通过卡方检验和方差分析确定的潜在类别成员的潜在预测因子的预测效果。

结果: 确定了四种潜在剖面:复原力(10.7%), 成长 (20.1%), 混合中等症状 (42.2%) 和混合高症状 (27.0%)。与死者关系亲密并确定 COVID-19 为根本死因的丧亲者更有可能属于混合高症状组。与死者有冲突会降低成为成长群体的几率。此外, 年轻人的死亡和丧失伴侣会增加适应不良的结果。

结论: 需要认真关注因 COVID-19 丧亲者的心理健康问题, 因为该群体中有近 70% 的人具有混合中等或混合高症状剖面。应该给那些丧失更年轻人, 伴侣或与死者关系亲密的人提供特别护理。处理死者与丧亲者之间的冲突和未完成事件的哀伤疗法可用于促进成长。

关键词: 延长哀伤, 创伤后应激, 创伤后成长, 潜在剖面分析, COVID-19

1. Introduction

The outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has brought devastating and persistent influences all over the world. As reported by the World Health Organization (WHO), by 25 April 2021, there were nearly 3.1 million deaths globally due to the pandemic (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). Because approximately nine close relatives would be affected by one COVID-19 death (Verdery, Smith-Greenaway, Margolis, & Daw, 2020), the pandemic has affected nearly 28 million people globally so far. However, if considering the deaths of close friends and acquaintances, this number could be even larger. Besides deaths due to COVID-19, the dramatic decline in admissions to hospitals with medical emergencies and delayed treatment for life-threatening illnesses during the pandemic resulted in excess mortality in care homes, hospices and at home (Wu et al., 2020). Moreover, the social distancing interventions led to increased social isolation, decreased access to community and religious support and barriers to mental health treatment, which may increase the risk of suicide (Reger, Stanley, & Joiner, 2020). As the pandemic continues spreading worldwide, the number of COVID-19-related deaths will increase and the COVID-19- related bereaved population will become larger.

Except for the huge number of the COVID-19-bereaved population, the greatly changed circumstances of the deaths during the pandemic added to the complication of the grieving process. Due to the infectious nature of COVID-19, the patients are physically isolated without the presence of loved ones, depersonalized by protective clothing, masks and/or visors, and a body is also removed and identified from a distance after a sudden death (Stroebe & Schut, 2020). Funerals and/or burials are frequently curtailed, postponed or remotely held, and the bereaved are unable to say farewell face-to-face and/or in accustomed ways, or to grieve through cultural or religious mourning practices (Stroebe & Schut, 2020). For instance, in China, because of restrictions in social contact, after a person died from COVID-19, family members were usually not able to gather together to attend the wake preceding the funeral that may last several days, where family members are expected to keep an overnight vigil for at least one night in which the deceased’s photograph, flowers and candles are placed on the body and the family sits nearby. Similarly, most people cancelled the traditional practice to visit and sweep the tomb to memorialize the decedents during the Tsing Ming Festival in April 2020. Therefore, the grieving process of this COVID-19 bereaved group may be different from other types of bereavement, and these people may face more severe mental health difficulty.

1.1. Mental health outcomes among people bereaved due to COVID-19

Deaths due to COVID-19 often occur rapidly, and sudden death and/or unexpected death is associated with adverse mental health outcomes, including high prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Atwoli et al., 2017) and prolonged grief disorder (PGD) (Djelantik, Smid, Mroz, Kleber, & Boelen, 2020). PTSD may develop following exposure to an extremely threatening or horrific event, is characterized by re-experiencing the traumatic event, avoidance of thoughts and memories of the event, and persistent perceptions of heightened current threat, and this persists for at least several weeks (WHO, 2018). PGD is a newly included mental disorder associated with stress in the International Classification of Diseases 11th edition (ICD-11) (WHO, 2018) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition text revision (DSM-5-TR) (Prigerson, Boelen, Xu, Smith, & Maciejewski, 2021). In ICD-11, PGD is defined as a persistent and pervasive grief response characterized by longing for the deceased and/or persistent preoccupation with the deceased, accompanied by intense emotional pain, and persists for an atypical long period of time following the loss (more than 6 months at a minimum) (WHO, 2018). After the outbreak of COVID-19, researchers have consistently expressed concerns and/or predicted that mental health problems associated with COVID-19-related bereavement would increase, and one of the most frequently mentioned is PGD (Eisma, Boelen, & Lenferink, 2020; Gesi et al., 2020; Goveas & Shear, 2020; Johns, Blackburn, & McAuliffe, 2020; Kokou-Kpolou, Fernández-Alcántara, & Cénat, 2020; Masiero, Mazzocco, Harnois, Cropley, & Pravettoni, 2020; Mortazavi, Assari, Alimohamadi, Rafiee, & Shati, 2020; Wallace, Wladkowski, Gibson, & White, 2020; Zhai & Du, 2020).

Despite the rich theoretical discussion on the possible rise of grief during and/or after the pandemic, very little empirical evidence was gathered. Prevalence of PGD in the Chinese bereaved due to COVID-19 was as high as 37.8% (Tang & Xiang, 2021). One study that included 49 Dutch individuals bereaved due to COVID-19 showed that this group of bereaved people reported more severe grief than people bereaved due to natural deaths and an equivalent severity of grief with people bereaved due to unnatural deaths (Eisma, Tamminga, Smid, & Boelen, 2021). Another study established that 66.1% of American individuals whose significant person died from COVID-19 met the clinical threshold of dysfunctional grief (Breen, Lee, & Neimeyer, 2021), which accounted for 25% of the variance of functional impairment caused by a COVID-19 death.

Considering that death from COVID-19 may be perceived as a traumatic event by the bereaved person, researchers need to heed the post-traumatic stress symptoms. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms was 22% in the Chinese bereaved due to COVID-19 (Tang, Yu, Chen, Fan, & Eisma, 2021), and post-traumatic stress explained 13% of the variance of functional impairment among American individuals bereaved due to COVID-19 (Breen et al., 2021).

While many researchers focused on the negative mental health consequences of bereavement due to COVID-19, some pointed out that ‘people can and do manage’ even facing COVID-19-related stressors including loss of loved ones (Pfefferbaum & North, 2020). Another scholar emphasized the positive aspects by demonstrating how families could deal with pandemic-related losses by sharing belief systems in meaning-making processes, positive and hopeful outlook and active agency, and transcendent values and spiritual moorings for inspiration, transformation and positive growth (Walsh, 2020). Resilience and post-traumatic growth (PTG) can be used to understand the potential to develop salutogenic outcomes when facing the loss of a loved one. Resilience reflects the ability to maintain a stable equilibrium so that the bereaved individuals experience minimal or mild psychological distress (Bonanno, 2004). PTG refers to the experience of positive change that occurs as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life crises, including an increased appreciation of life and changed sense of priorities, more intimate relationships with others, a greater sense of personal strength, recognition of new possibilities or paths for one’s life, and spiritual development (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). To our knowledge, the existence of resilience and PTG after COVID-19 bereavement have not yet been verified by empirical evidence.

1.2. Hetergeneity of mental health outcomes

When looking into mental health outcomes brought about by COVID-19 deaths, identifying heterogeneous subgroups with various outcome patterns could deepen our understanding of these experiences, and unveiling predictors of class membership can inform prevention and intervention. To this end, person-centred analytic methods (Berlin, Williams, & Parra, 2014) should be employed; methods such as latent variable mixture modelling (LVMM) model with categorical latent variables that represent subpopulations defined by specific combinations of observed variables. As cases of LVMM, latent class analysis (LCA) and LPA are for binary and continuous observed variables, respectively (Mori, Krumholz, & Allore, 2020).

Recent years have seen growing applications of LCA and LPA in bereavement studies. Among 496 Dutch bereaved for 13.3 months (SD = 8.8) (Djelantik, Smid, Kleber, & Boelen, 2017), three subgroups with various profiles of PGD, PTSD and major depression disorder (MDD) were identified: a PGD class (47%), a combined PGD/PTSD class (27%), and a resilient class (25%). Focusing on the same symptoms, two similar analyses among participants at their acute grief stage also provided valuable insights. Seventy days after the confirmation of their loved ones’ death (SD = 102) due to the MH17 plane crash, a PGD class (41.8%), a combined class of high PGD, MDD, and PTSD symptoms (38.2%) and a resilient class (20.0%) were identified among 167 Ukrainians (Lenferink, de Keijser, Smid, Djelantik, & Boelen, 2017). Among 322 Dutch individuals bereaved no more than 6 months earlier, a high symptom class with high PGT, PTSD and depression scores (34.8%), a low symptom class (35.4%) and a predominantly PGD class (29.8%) were unveiled (Boelen & Lenferink, 2020). Moreover, LPA was applied to the general bereaved Australians for PGD-depression profiles 3.67 years after their loss (SD = 3.89) (Maccallum & Bryant, 2018a) and PGD-PTSD profiles 3.33 years after their loss (SD = 3.28) (Maccallum & Bryant, 2018b). It was also applied to 803 Sichuan Earthquake survivors in China for PTSD-complicated grief (CG) profiles 1 year after the disaster (Eisma, Lenferink, Chow, Chan, & Li, 2019).

Compared to negative consequences, positive outcomes were less involved in individual-oriented bereavement studies. Three studies in China covered the positive aspect. With depression, anxiety, PTSD, PGD, PTG and hope as observed variables, Zhang and Jia (2019) identified a ‘low mental disorder-high hope’ (23.3%) profile among 466 parents who lost their only child. Meanwhile, Zhou, Yu, Tang, Wang, and Killikelly (2018) found a ‘low PGD-high PTG’ (40%) subgroup among the general bereaved taking PGD and PTG measures. Both studies unveiled an encouraging subgroup that experiences bearable pains and achieves drastic gains after major losses in life. In a study by Li, Sun, Maccallum, and Chow (2020), 194 general bereaved Chinese reported their anxiety, depression and PTG, and a growth group with high PTG and low anxiety/depression accounted for 64.4% of the sample.

In the aforementioned studies, losing a child or spouse rather than others (Eisma et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2018), high attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance (Maccallum & Bryant, 2018a), lower social support (Li et al., 2020), sense of unrealness (Lenferink et al., 2017), negative cognitions about one’s grief (Djelantik et al., 2017) and negative self-related appraisals (Maccallum & Bryant, 2018a) were unveiled by multinomial logistic regressions as significant predictors of maladaptive classes. One disadvantage of multinomial logistic regression is that misclassification of cases in the preceding LVMM is neglected when testing the predicting effects of covariates (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014).

1.3. The present study

The present study focused on people bereaved from deaths due to COVID-19. Until then, existing studies on losses due to COVID-19 and other sudden and traumatic events have paid much less attention to positive outcomes than to negative ones. Heterogeneity of mental health outcomes had never been explored among COVID-19 bereaved persons. Moreover, multinomial logistic regressions were employed for the identification of predictors of latent group membership, the results of which could be distorted by misclassification in LVMM (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014).

To fill the aforementioned research gaps, the present study aimed to 1) use LPA to identify heterogeneous profiles of prolonged grief, post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth among people bereaved due to COVID-19; and 2) identify predictors of class membership while taking into consideration the misclassification in LPA.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedure

We conducted an online survey between September and October 2020 and recruited participants through social network websites and mobile applications. Participants aged 18 years or above and who had lost a close person due to the COVID-19 pandemic were eligible to participate in the survey. Before entering the formal survey, a consent page, including the purpose of the study, voluntariness of participation, confidentiality, data retention and two screening questions, was presented. Only when the participants indicated that they had experienced the loss in or after January 2020 and the death of the deceased person was due to COVID-19, and chose the option ‘I understand the information described above and agree to participate in this study’ could they access the questionnaire. After completing the questionnaire, grief support resources, including free hotlines specifically set up for the pandemic and free grief counselling provided by professional institutes during the pandemic, were presented to every participant. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Health Science Center, Shenzhen University prior to data collection (No. 2020024).

In total, 476 participants completed the survey. Fifty-four participants were removed from detailed data analysis because they finished the survey in less than 5 minutes (n = 21), provided inconsistent information about the deceased person (n = 15), were bereaved more than 9 months ago (n = 11) or had patterned responses (n = 8). Thus, the final sample comprised 422 participants. Since the participants were recruited through online social networks, the sample was not representative.

3. Measures

3.1. Demographic and loss-related information

The demographics included each participant’s gender, age, education, religious belief and marital status. Loss-related information included relationship with the deceased (i.e. partner, child, parent, grandparent, relative, friend, or other), gender and age of the deceased, time since loss in months, and cause of death (i.e. COVID-19 and COVID-19-related complication). Subjective experiences of the loss, including the unexpectedness of the death and perceived traumatic levels, were measured. Moreover, the quality of relationship with the deceased defined by both closeness and conflicts with the deceased (Bottomley, Smigelsky, Floyd, & Neimeyer, 2017) were also assessed. The latter four variables were all measured by single items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

3.2. International ICD-11 Prolonged Grief Disorder Scale (IPGDS) (Killikelly et al., 2020)

The standard scale of IPGDS is a 14-item self-report measure developed for assessing PGD symptoms in ICD-11. It contains 13 self-report items about yearning, preoccupation, emotional distress and functioning impairment after the death of a close person, and one cultural screening item. The cultural screening item asks participants to rate to what degree their grief would be considered worse (e.g. more intense, severe and/or of longer duration) than for others from their community or culture. Participants indicated how often they experienced these symptoms in the past month on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (always). A total score summed by all items excluding the cultural screening item represents the symptom levels of PGD, with higher scores indicating higher levels of symptoms. The IPGDS was validated in the Chinese bereaved people (Killikelly et al., 2020), and the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 in the current sample.

3.3. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015)

The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses the presence and severity of PTSD symptoms in DSM-5. The participants rated how bothered they had been by each item in the past month on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The guidance of this scale indicated that ‘the stressful experience’ in each item referred to their experience of losing a loved one due to COVID-19. All items were summed to provide a total score, with higher scores suggesting more severe PTSD symptoms. The PCL-5 was validated in Chinese healthcare workers during the outbreak of COVID-19 (Cheng et al., 2020), and the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94 in the current sample.

3.4. Post-traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996)

The PTGI is a 21-item self-report measure designed for assessing positive outcomes reported by people who have experienced adverse life events including bereavement. Participants reported to what extent things have changed because of their loss on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (I did not experience this change as a result of my loss) to 5 (I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my loss). A higher sum score of all items suggests greater positive changes after the loss. The Chinese version of the PTGI demonstrated good psychometric properties (Wang, Chen, Wang, & Liu, 2011), and the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93 in the current sample.

3.5. Statistical analyses

Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2014) was used to conduct LPA, and SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, 2017) was applied to complete initial analysis and between-profile comparisons in observable variables. First, descriptive analyses were run among the cases on demographic and loss-related information, and means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s αs were calculated for IPCGS, PCL-5, and PTGI total scores.

After that, LPA with unconditional models was conducted using all item scores in IPCGS, PCL-5 and PTGI scales as observed responses to examine and identify the patterns that individuals respond on the items. The number of latent profiles was determined by criteria including smaller Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and sample-size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (aBIC), the smallest profile with a size of no less than 1% of the total sample, higher entropy (near 1), higher posterior probabilities (0.8 or larger), significant Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted Likelihood Ratio test (LMR-LRT) and Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) results (Geiser, 2012), as well as theoretical considerations.

With the selected model, detailed analyses of each profile and between-profile comparisons were conducted to reflect the characteristics of discovered latent profiles. Next, variables regarding demographics and loss-related information were tested one by one for their relationships with latent class membership, and chi-square tests and ANOVAs were used for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Significant variables in individual tests were joined as potential predictors of LPA in the 3-step auxiliary approach (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014). The method could allow for the misclassification in LVMM while running regressions. The variables were tested one by one in separate logistic regressions initially and were then joined together in one regression.

4. Results

4.1. Sample characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographic and loss-related characteristics of the sample. The sample was relatively young (32.73 ±9.31), with 55.5% being men. Most of the participants had received higher education (79.4%), had no religious belief (93.6%), and were married (73.0%). Participants who had lost their partner accounted for 32.9% of the sample, followed by those who lost a parent (23.0%), a grandparent (16.4%), a friend (15.2%) or a relative (5.2%), and they were bereaved on average 5.10 ±1.72 months ago. At the time of death, the average age of the deceased was 47.81 (Range: 1–103, SD = 21.55) years. For the bereaved, they were quite close to the deceased (Range: 1–5, M = 4.15, SD = .86), there was not much tension in the relationship (Range: 1–5, M = 1.76, SD = 1.11), and the death was quite unexpected (Range: 1–5, M = 3.67, SD = 1.23). On average, the participants’ total score on IPGDS, PCL-5, and PTGI was 44.62 (Range: 19–65, SD = 10.40, Cronbach’s = .896), 38.36 (Range: 4–70, SD = 16.22, Cronbach’s = .946), and 66.81 (Range: 10–95, SD = 16.71, Cronbach’s = .931), respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and loss-related information of participants (N = 422)a–d

| Variable | M/n | SD/% |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.73 | 9.31 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 234 | 55.5% |

| Female | 188 | 44.5% |

| Education | ||

| Junior secondary school and/or below | 21 | 5.0% |

| Senior secondary school | 66 | 15.6% |

| College | 320 | 75.8% |

| Postgraduate and/or above | 15 | 3.6% |

| Religious belief | ||

| No | 395 | 93.6% |

| Yesa | 27 | 6.4% |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 107 | 25.4% |

| Married | 308 | 73.0% |

| Divorced | 7 | 1.7% |

| Role of deceased | ||

| Partner | 139 | 32.9% |

| Child | 24 | 5.7% |

| Parent | 97 | 23.0% |

| Grandparent | 69 | 16.4% |

| Relativeb | 22 | 5.2% |

| Friend | 64 | 15.2% |

| Otherc | 7 | 1.7% |

| Age of deceased | 47.81 | 21.55 |

| Gender of deceased | ||

| Male | 207 | 49.1% |

| Female | 215 | 50.9% |

| Time since loss in months | 5.10 | 1.72 |

| Cause of death | ||

| COVID-19 | 408 | 96.7% |

| COVID-19 related complicationd | 14 | 3.3% |

| Unexpectedness of death | 3.67 | 1.23 |

| Traumatic level of loss | 3.86 | 0.97 |

| Closeness with deceased | 4.15 | 0.88 |

| Conflict with deceased | 1.76 | 1.11 |

M: Mean; SD: Standard Deviation.

aReligious belief included Buddhism (n = 17), Taoism (n = 3), Catholicism (n = 3), Christianism (n = 3), and Islamism (n = 1).

bRelative included uncle (n = 5), aunt (n = 4), cousin (n = 4), grandaunt (n = 3), granduncle (n = 1), great grandmother (n = 1), and not specified (n = 4).

cOther relationship included colleagues (n = 4), acquaintance (n = 2), and not specified (n = 1).

dCOVID-19 related complication included heart disease (n = 2), fever (n = 2), acute respiratory distress syndrome (n = 1), asthma (n = 1), cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (n = 1), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 1), diabetes (n = 1), high blood pressure (n = 1), liver cancer (n = 1), lung cancer (n = 1), obesity (n = 1), and respiratory failure (n = 1).

4.2. Latent classes

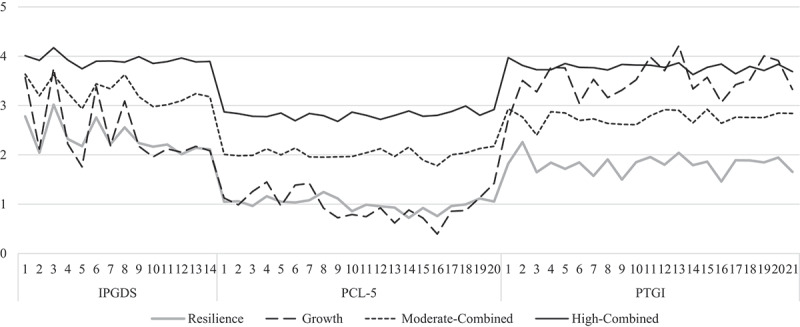

The results of LPA models with 1 to 5 classes are shown in Table 2. According to the statistics, models with both 3 and 4 classes are eligible because they fit the data significantly better than the 2-class model and had satisfying posterior probabilities. Moreover, the 5-class model is not ideal for the smallest groups (n = 14) and has less than 5% of the total sample size. Eventually, the model with 4 classes (Figure 1) was chosen as it has higher entropy, and is more reasonable theoretically. The number of participants in 1–4 classes was 45 (10.7%), 85 (20.1%), 178 (42.2%) and 114 (27.0%), respectively.

Table 2.

Parameters of LPA models with 1 to 5 classesa,b

| N of classes | AICa | aBICa | C1a | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | Entropy | Posterior probabilities | LMR-LRTa,b | BLRTa,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 73557.268 | 73653.153 | 422 | ||||||||

| 2 | 68969.593 | 69114.292 | 220 | 202 | 0.957 | .992, .986 | *** | *** | |||

| 3 | 67294.915 | 67488.428 | 106 | 191 | 125 | 0.960 | .995, .975, .982 | * | *** | ||

| 4 | 66118.083 | 66360.410 | 45 | 85 | 178 | 114 | 0.969 | .985, .988, .980, .989 | *** | ||

| 5 | 65481.315 | 65772.456 | 77 | 44 | 173 | 14 | 114 | 0.971 | .984, .986, .983, .998, .982 | *** |

aAIC: Akaike Information Criteria; aBIC: sample-size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria; Cn: size of the nth group; LMR-LRT: Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted LRT test; BLRT: Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test.

b*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Figure 1.

Symptom profiles in the 4-class model

IPGDS: International Prolonged Grief Disorder Scale; PCL-5: PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PTGI: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory.

The differences between classes in IPGDS, PCL-C and PTGI scores are shown in Table 3. According to the scores, Class 1 was named ‘resilience’ for it had the lowest scores in both positive (PTGI) and negative (IPGDS and PCL-C) aspects. Since Class 2 was lowest in IPGDS and PCL-C but high in PTGI scores, it was named ‘growth’. Class 3 and Class 4 had moderate to high scores in both positive and negative aspects. According to their differences, they were named ‘moderate-combined’, and ‘high-combined’, respectively.

Table 3.

Between class differences in prolonged grief, post-traumatic stress, and post-traumatic growtha

| IPGDS | PCL-5 | PTGI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | 32.71 (7.65) | 19.84 (8.90) | 38.09 (12.25) |

| Class 2 | 34.67 (8.36) | 19.57 (8.04) | 73.78 (10.73) |

| Class 3 | 45.72 (6.42) | 40.43 (8.33) | 57.91 (11.28) |

| Class 4 | 55.02 (4.69) | 56.43 (7.34) | 79.47 (7.75) |

| Fa | 208.86*** | 462.15*** | 219.91*** |

| Post hoc tests | 1 = 2 < 3 < 4 | 1 = 2 < 3 < 4 | 1 < 3 < 2 < 4 |

IPGDS: International Prolonged Grief Disorder Scale; PCL-5: PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PTGI: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory.

a*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

4.3. Predictors of latent class membership

Comparing potential predictors between classes, chi-square tests detected no significant differences in sex ( = 2.251, df = 3, p = .522), occupation ( = 10.519, df = 12, p = .571), religion ( = 7.559, df = 3, p = .056), education ( = 10.697, df = 9, p = .297), marital status of the bereaved ( = 9.470, df = 6, p = .149) or sex of the deceased ( = .628, df = 3, p = .890). However, significant differences were found in the cause of death ( = 19.577, df = 3, p .001) and the relationship between the participant and the deceased ( = 44.002, df = 18, p = .001). More detailed analysis reavealed that the proportion of the deceased’s partners varied significantly across classes ( = 19.742, df = 3, p .001). Moreover, in ANOVAs, the four classes did not differ in age of the participant (F = .340, df = 3, p = .796), time since bereavement (F = 7.257, df = 3, p = .062), or how unexpected the death was for the participant (F = 2.100, df = 3, p = .100). Significant differences lay in the age of the deceased (F = 5.898, df = 3, p = .001), closeness with the deceased (F = 8.088, df = 3, p .001) and conflicts with the deceased (F = 11.022, df = 3, p .001).

Age of the deceased, whether the participant was the partner of the deceased (1 = yes, 0 = no), the closeness and conflicts between the participant and the deceased, and the cause of death (1 = COVID-19, 0 = complications) were added into the 3-step auxiliary approach as predictors. They were first tested one by one and then combined in the regression.

The results are shown in Table 4. Those who were bereaved of an older loved one were more likely to be in the growth group rather than the moderate-combined group. The bereaved who were close to the deceased tended to show the high-combined symptom pattern rather than the other three, and the moderate-combined pattern rather than the resilience one. Being a partner of the deceased significantly predicted membership in the moderate-combined and high-combined group rather than the resilience group. Meanwhile, conflicts in the relationship brought lower possibility of being in the growth group, and it also predicted membership in the high-combined rather than the moderate-combined group. Lastly, if the deceased died from COVID-19 directly, the bereaved were more likely to be in the high-combined group. They were also more likely to be in the moderate-combined rather than the growth group.

Table 4.

Results (unstandardized beta) of logistic regressions using the 3-step procedurea

| Model | Age of the deceaseda | Closenessa | Partnera | Conflictsa | Cause of Deatha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models with one predictor | n | 422 | 422 | 422 | 422 | 422 |

| Reference: Resilience | ||||||

| Growth | .009 | .373 | .571 | −.624** | −.949 | |

| Moderate-combined | .009 | .58** | 1.371** | .087 | 1.023 | |

| High-combined | .009 | .941*** | 1.615** | .299 | 18.668*** | |

| Reference: Growth | ||||||

| Moderate-combined | −.022*** | .207 | .799* | .711*** | 1.972** | |

| High-combined | −.025*** | .568** | 1.043** | .923*** | 19.617*** | |

| Reference: Moderate-combined | ||||||

| High-combined | −.003 | .361* | .244 | .211* | 17.645*** | |

| Models with all predictors | n | 422 | 422 | 422 | 422 | 422 |

| Reference: Resilience | ||||||

| Growth | .011 | .288 | .9 | −.674** | −1.314 | |

| Moderate-combined | −.005 | .47** | 1.055* | .044 | .401 | |

| High-combined | −.004 | .837*** | 1.086* | .263 | 17.596*** | |

| Reference: Growth | ||||||

| Moderate-combined | −.015* | .182 | .155 | .718** | 1.715* | |

| High-combined | −.015 | .549** | .185 | .937*** | 18.91*** | |

| Reference: Moderate-combined | ||||||

| High-combined | .001 | .367* | .031 | .219* | 17.195*** | |

a*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

5. Discussion

5.1. Principal results

In the present study, four profiles of prolonged grief, post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth were identified among the 422 Chinese people bereaved due to COVID-19 after one to nine months of the death: the resilience group (10.7%) with low PGD, PTSD and PTG scores; the growth group (20.1%) with low PGD and PTSD but high PTG; the moderate-combined group (42.2%) with moderate scores across all scales; and the high-combined group (27.0%). These patterns, especially the growth group with high PTG and low emotional disorders, echo the findings from previous studies among the general bereaved Chinese and those who lost their only child (Li et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2018). The smaller growth group in the present study (20.1% vs. 40% and 64.4%) could be partially attributed to the differences in observed variables. In the study by Li et al. (2020), indicators of negative bereavement outcomes are less prominent ones like depression and anxiety rather than pathological grief, which could lead to the underestimation of maladaptive subgroups. Moreover, the COVID-19 context could make growth after bereavement harder. The missed chances of saying the last goodbye, the thought that loved ones died lonely, the impossibility of attending funerals ‘as usual’, the unavailable social support (Stroebe & Schut, 2020) and the fact that the pandemic is far from over and is even getting worse could all compound the suffering. However, even under such circumstances, the high-combined group with more than 1/4 of the participants demonstrated the idea of ‘no pain, no gain’ (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

Predictors of latent class membership bring insights. In terms of quality of the relationship, both closeness and conflicts with the deceased (Bottomley et al., 2017; Shear et al., 2007) were significant predictors of latent class membership. A closer relationship perceived by the bereaved increases the likelihood of being in the high-combined group rather than the other three since a loss closer to one’s heart naturally brings more impacts in every aspect. Meanwhile, conflicts in the relationship decreases the chance of ending up in the most adaptive group of growth. Conflicts between the bereaved and the deceased may indicate problematic attachment styles, such as attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, which contribute to maladaptive bereavement outcomes (Maccallum & Bryant, 2018a). Moreover, there might be unfinished business after the end of a turbulent relationship, which imposes risk of chronic and severe grief reactions (Klingspon, Holland, Neimeyer, & Lichtenthal, 2015). Interestingly, after controlling the quality of the relationship, losing a partner is still a significant predictor of being in the moderate-combined and the high-combined group rather than the resilience group. This can be explained by the interdependence between the partners. Bereavement brings not only emotional pains but also challenges in daily life without the help of the deceased (Stroebe & Schut, 2010), and the latter can be reflected by the objective relationship. In the case of partner loss, additional difficulties in life adaptation increase the overall impacts of bereavement (Shimizu, 2020). In an early study on victims of the 2004 South-East Asian Tsunami, losing a partner significantly increased the risks of CG 2 years after the incident (Kristensen, Weisaeth, & Heir, 2010).

The death of a younger person is more likely to cause a moderate-combined than a growth profile. When losing someone young, especially a child, the family is left with an overwhelming sense of grief for not only the passing of their life but also the death of hope (Kochen et al., 2020). Meanwhile, those who attributed death to COVID-19 directly are more likely to be in the high-combined group than those who thought their loved ones died of a pre-existing disease intensified due to COVID-19. Caution needs to be taken when evaluating such a finding since the present study only involved 14 participants (out of 422) with the latter attribution. The finding may be explained by proximity; an early study among mass university shooting victims showed that higher proximity predicted more intense post-traumatic symptoms as well as more PTG (Wozniak, Caudle, Harding, Vieselmeyer, & Mezulis, 2020). Accordingly, those who believed that COVID-19 was the fundamental cause of death of their loved ones may have higher emotional proximity towards COVID-19, so that they had experienced higher symptoms and growth.

It is worth noticing that time since bereavement and unexpectedness of the death were not significant predictors of latent class membership, both of which are deeply rooted in the COVID-19 context. Following unnatural deaths caused by natural disaster, suicide and intentional killing, the prevalence of PGD among survivors decreases with time since the loss (Djelantik et al., 2020). What differs in the COVID-19 case is that the passage of time did not bring peace but ever-increasing exposure to loss-related information. The news headlines and social media posts kept reminding the deceased of the loss and new deaths due to the exact same cause every day. Under such circumstances, the curing power of time was mitigated. Meanwhile, whether or not the bereaved had foreseen the death several days before it took place, the idea that a pandemic that was not even known to the world before 2020 would cause their loved one’s death was beyond anyone’s imagination. Since the unexpectedness at a much more general level had drastically shaped bereavement experiences due to COVID-19, the predictability around the specific death event may not be able to make much of a difference.

5.2. Clinical implications

The aforementioned findings could inform clinical practice. Firstly, serious attention needs to be paid to the mental health issues of people bereaved due to COVID-19 because nearly 70% of this group would have a moderate-combined or high-combined symptom profile. Aiming for more tailored interventions, a heterogeneous perspective is necessary: special care should be given to those who lost someone younger, lost a life partner, or shared a close relationship with the deceased to help release emotional pains. Grief therapies that work on conflicts and unfinished business between the bereaved and the deceased can be applied to facilitate growth. Due to the social restrictions caused by COVID-19, special efforts should be made to implement methods that can be widely applied without face-to-face interactions, such as web-based bereavement care (Birgit, Nicole, Laura, & Ulrike, 2020).

5.3. Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted with caution because of the following limitations. Firstly, convenience sampling was adopted to recruit participants for the online survey, which hampered the representativeness of the bereaved sample. For example, the current sample is relatively younger and with fewer mental health problems. Self-selection bias may exist; hence, bereaved people with more severe mental health problems were less likely to complete the questionnaire as they may experience higher psychological distress during the process and quit the survey more easily. Secondly, the present study mainly involved participants in the acute phase of grief, and how the impacts of such a life-changing incident could unfold in the long run remains unexplored. Moreover, the cross-sectional design was unable to examine how different mental health outcome patterns affect the physical and social functioning of the bereaved individuals. Thirdly, the characteristics of COVID-19 bereavement situations, such as circumstances around the death, funeral practices and farewell rituals, physical and social isolation, and access to physical and social support were not included as predictive factors of mental health outcome patterns. Future studies can recruit a more representative sample with community-based sampling strategies, design longitudinal surveys and include features of COVID-19 bereavement as predictive factors of mental health patterns.

5.4. Significance

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate adaptation in bereavement following deaths from COVID-19 from a heterogenetic and person-centred perspective by adopting LPA. It is also the first study to provide empirical evidence on positive process and growth among people bereaved due to COVID-19 deaths. Moreover, discarding multinomial logistic regression analyses used by previous studies, this study adopted a more rigorous method (i.e. 3-step auxiliary approach in LVMM) to identify predictive factors of different patterns of mental health outcomes, which is rare among bereavement studies.

5.5. Future studies

Follow-up investigations on COVID-19-related bereaved people can be conducted at the time the pandemic ends to explore how much the grieving process has been affected by the pandemic when comparing with bereavement in other circumstances, such as daily life, accidents and natural disasters. Moreover, since bereavement is an ongoing process, positive coping might be more noticeable after a longer period of time. Given the robust individual differences revealed in this study, indicated intervention needs to be developed and channelled for individuals with various characteristics, and the feasibility and effectiveness of such intervention should be examined.

6. Conclusions

LPA identified four latent profiles among 422 Chinese bereaved people due to COVID-19: resilience (10.7%), growth (20.1%), moderate-combined (42.2%) and high-combined (27.0%). The bereaved who shared a close relationship with the deceased and perceived COVID-19 as the fundamental cause of death were more likely to be in the high-combined group. Conflicts between the bereaved and the deceased decreases the chance of being in the growth group. Moreover, the death of a younger person and losing a partner attributed to maladaptive outcomes. Serious attention needs to be paid to the mental health issues of people bereaved due to COVID-19, and a heterogeneous perspective should be taken to enable more tailored support.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Guangdong Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Science [grant number GD20YSH06], and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant number 2242021S20002].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, S. T. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–12. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.915181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atwoli, L., Stein, D. J., King, A., Petukhova, M., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., & Kessler, R. C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder associated with unexpected death of a loved one: Cross-national findings from the world mental health surveys. Depression and Anxiety, 34(4), 315–326. doi: 10.1002/da.22579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, K. S., Williams, N. A., & Parra, G. R. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (Part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(2), 174. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birgit, W., Nicole, R., Laura, H., & Ulrike, M. (2020, June 1). Web-based bereavement care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. PMID: edsdoj.0ec258d85f44c87b93af7320c7ab58e. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen, P. A., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2020). Symptoms of prolonged grief, posttraumatic stress, and depression in recently bereaved people: Symptom profiles, predictive value, and cognitive behavioural correlates. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(6), PMID: 31535165, 765–777. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01776-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? The American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottomley, J. S., Smigelsky, M. A., Floyd, R. G., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2017). Closeness and conflict with the deceased: Exploring the factor structure of the quality of relationships inventory in a bereaved student sample. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 79(4), 377–393. doi: 10.1177/0030222817718959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen, L. J., Lee, S. A., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2021). Psychological risk factors of functional impairment after COVID-19 deaths. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 61(4), e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P., Xu, L.-Z., Zheng, W.-H., Ng, R. M. K., Zhang, L., Li, L.-J., & Li, W.-H. (2020). Psychometric property study of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) in Chinese healthcare workers during the outbreak of corona virus disease 2019, Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djelantik, A., Smid, G. E., Mroz, A., Kleber, R. J., & Boelen, P. A. (2020, March 15). The prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in bereaved individuals following unnatural losses: Systematic review and meta regression analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 146–156. PMID: 32090736. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djelantik, A. A. A. M. J., Smid, G. E., Kleber, R. J., & Boelen, P. A. (2017). Symptoms of prolonged grief, post-traumatic stress, and depression after loss in a Dutch community sample: A latent class analysis, Psychiatry Research, 247, 276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma, M. C., Boelen, P. A., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2020). Prolonged grief disorder following the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, Psychiatry Research, 288, 113031. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma, M. C., Lenferink, L. I. M., Chow, A. Y. M., Chan, C. L. W., & Li, J. (2019, January 1). Complicated grief and post-traumatic stress symptom profiles in bereaved earthquake survivors: A latent class analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1558707. PMID: WOS:000455812900001. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018.1558707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisma, M. C., Tamminga, A., Smid, G. E., & Boelen, P. A. (2021). Acute grief after deaths due to COVID-19, natural causes and unnatural causes: An empirical comparison, Journal of Affective Disorders, 278, 54–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser, C. (2012). Data analysis with Mplus. New York: Guilford Press. (ISBN: 1462507840). [Google Scholar]

- Gesi, C., Carmassi, C., Cerveri, G., Carpita, B., Cremone, I. M., & Dell’Osso, L. (2020). Complicated grief: What to expect after the coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11(489). doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goveas, J. S., & Shear, M. K. (2020). Grief and the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(10), 1119–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp . (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for Macintosh (25th ed.). Armonk, NY: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, L., Blackburn, P., & McAuliffe, D. (2020). COVID-19, prolonged grief disorder and the role of social work. International Social Work, 63(5), 660–664. doi: 10.1177/0020872820941032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killikelly, C., Zhou, N., Merzhvynska, M., Stelzer, E.-M., Dotschung, T., Rohner, S., … Maercker, A. (2020). Development of the international prolonged grief disorder scale for the ICD-11: Measurement of core symptoms and culture items adapted for Chinese and German-speaking samples, Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 568–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingspon, K. L., Holland, J. M., Neimeyer, R. A., & Lichtenthal, W. G. (2015). Unfinished business in bereavement. Death Studies, 39(7), 387–398. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2015.1029143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochen, E. M., Jenken, F., Boelen, P. A., Deben, L. M. A., Fahner, J. C., Van Den Hoogen, A., & Kars, M. C. (2020). When a child dies: A systematic review of well-defined parent-focused bereavement interventions and their alignment with grief- and loss theories. BMC Palliative Care, 19(1). PMID: edssjs.40C981CA. doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-0529-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Fernández-Alcántara, M., & Cénat, J. M. (2020). Prolonged grief related to COVID-19 deaths: Do we have to fear a steep rise in traumatic and disenfranchised griefs? Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S94–S5. doi: 10.1037/tra0000798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, P., Weisaeth, L., & Heir, T. (2010). Predictors of complicated grief after a natural disaster: A population study two years after the 2004 South-East Asian Tsunami. Death Studies, 34(2), PMID: WOS:000273721900002, 137–150. doi: 10.1080/07481180903492455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenferink, L. I. M., de Keijser, J., Smid, G. E., Djelantik, A. A. A. M. J., & Boelen, P. A. (2017). Prolonged grief, depression, and posttraumatic stress in disaster-bereaved individuals: Latent class analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1298311. PMID: WOS:000396170800001. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1298311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Sun, Y., Maccallum, F., & Chow, A. Y. (2020). Depression, anxiety and post-traumatic growth among bereaved adults: A latent class analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575311. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.575311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccallum, F., & Bryant, R. A. (2018a). Prolonged grief and attachment security: A latent class analysis, Psychiatry Research, 268, 297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccallum, F., & Bryant, R. A. (2018b). Symptoms of prolonged grief and posttraumatic stress following loss: A latent class analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(1), 59–67. doi: 10.1177/0004867418768429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masiero, M., Mazzocco, K., Harnois, C., Cropley, M., & Pravettoni, G. (2020). From individual to social trauma: Sources of everyday trauma in Italy, The US and UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 21(5), 513–519. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2020.1787296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori, M., Krumholz, H. M., & Allore, H. G. (2020, August 18). Using latent class analysis to identify hidden clinical phenotypes. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association, 324(7), 700–701. PMID: WOS:000564288700015. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi, S. S., Assari, S., Alimohamadi, A., Rafiee, M., & Shati, M. (2020, March–April). Fear, loss, social isolation, and incomplete grief due to COVID-19: A recipe for a psychiatric pandemic. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience Journal, 11(2), 225–232. PMID: 32855782. doi: 10.32598/bcn.11.covid19.2549.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2014). Mplus (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. S. (2020). Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), PMID: 32283003, 510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson, H. G., Boelen, P. A., Xu, J., Smith, K. V., & Maciejewski, P. K. (2021). Validation of the new DSM-5-TR criteria for prolonged grief disorder and the PG-13-revised (PG-13-R) scale. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 20(1), 96–106. doi: 10.1002/wps.20823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger, M. A., Stanley, I. H., & Joiner, T. E. (2020). Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019—A perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry, 77(11), 1093. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear, K., Monk, T., Houck, P., Melhem, N., Frank, E., Reynolds, C., & Sillowash, R. (2007). An attachment-based model of complicated grief including the role of avoidance. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 257(8), 453–461. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0745-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, K. (2020). Risk factors of severe prolonged grief disorder among individuals experiencing late-life bereavement in Japan: A qualitative study. Death Studies, 1–9. PMID: WOS:000514508200001. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1728427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2010). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: A decade on. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 61(4), 273–289. doi: 10.2190/OM.61.4.b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2020). Bereavement in times of COVID-19: A review and theoretical framework. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 82(3), 500–522. doi: 10.1177/0030222820966928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S., & Xiang, Z. (2021). Who suffered most after deaths due to COVID-19? Prevalence and correlates of prolonged grief disorder in COVID-19 related bereaved adults. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 19. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00669-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S., Yu, Y., Chen, Q., Fan, M., & Eisma, M. C. (2021). Correlates of mental health after COVID-19 bereavement in Mainland China. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 61(6), e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Target article: “Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence”. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verdery, A. M., Smith-Greenaway, E., Margolis, R., & Daw, J. (2020). Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(30), 17695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007476117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, C. L., Wladkowski, S. P., Gibson, A., & White, P. (2020). Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: Considerations for palliative care providers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1), e70–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. (2020). Loss and resilience in the time of COVID-19: Meaning making, hope, and transcendence. Family Process, 59(3), 898–911. doi: 10.1111/famp.12588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Chen, Y., Wang, Y., & Liu, X. (2011). Revision of the posttraumatic growth inventory and testing its reliability and validity. Journal of Nursing Science (Surgery Edition), 26(14), 26–28. doi: 10.3870/hlxzz.2011.14.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2018). International classification of diseases (Vol. 2018, 11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2021). WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Retrieved from https://covid19.who.int/

- Wozniak, J. D., Caudle, H. E., Harding, K., Vieselmeyer, J., & Mezulis, A. H. (2020, March). The effect of trauma proximity and ruminative response styles on posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth following a university shooting. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(3), 227–234. PMID: WOS:000516543700002. doi: 10.1037/tra0000505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., Malfam, M., Mamas, M., Rashid, M., Kontopantelis, E., Deanfield, J. E., … Gale, C. P. (2020). Place and underlying cause of death during the COVID19 pandemic: Retrospective cohort study of 3.5 million deaths in England and Wales, 2014 to 2020. medRxiv. 2020/08/14/:2020.08.12.20173302. doi: 10.1101/2020.08.12.20173302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Y., & Du, X. (2020). Loss and grief amidst COVID-19: A path to adaptation and resilience. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 80–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D., & Jia, X. (2019). Mental health status of the shiduers: Based on latent profile analysis (In Chinese). Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(2), 362–366. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.02.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, N., Yu, W., Tang, S., Wang, J., & Killikelly, C. (2018). Prolonged grief and post-traumatic growth after loss: Latent class analysis, Psychiatry Research, 267, 221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, S. T. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.