Abstract

Purpose

Recently, our group found exosome-like extracellular vesicles (EVs) in Apis mellifera honey displaying strong antibacterial effects; however, the underlying mechanism is still not understood. Thus, the aim of this investigation was to characterize the molecular and nanomechanical properties of A. mellifera honey-derived EVs in order to elucidate the mechanisms behind their antibacterial effect, as well as to determine differential antibiofilm properties against relevant oral streptococci.

Methods

A. mellifera honey-derived EVs (HEc-EVs) isolated via ultracentrifugation were characterized with Western Blot and ELISA to determine the presence of specific exosomal markers and antibacterial cargo, and atomic force microscopy (AFM) was utilized to explore their ultrastructural and nanomechanical properties via non-destructive immobilization onto poly-L-lysine substrates. Furthermore, the effect of HEc-EVs on growth and biofilm inhibition of S. mutans was explored with microplate assays and compared to S. sanguinis. AFM was utilized to describe ultrastructural and nanomechanical alterations such as cell wall elasticity changes following HEc-EV exposure.

Results

Molecular characterization of HEc-EVs identified for the first time important conserved exosome markers such as CD63 and syntenin, and the antibacterial molecules MRJP1, defensin-1 and jellein-3 were found as intravesicular cargo. Nanomechanical characterization revealed that honey-derived EVs were mostly <150nm, with elastic modulus values in the low MPa range, comparable to EVs from other biological sources. Furthermore, incubating oral streptococci with EVs confirmed their antibacterial and antibiofilm capacities, displaying an increased effect on S. mutans compared to S. sanguinis. AFM nanocharacterization showed topographical and nanomechanical alterations consistent with membrane damage on S. mutans.

Conclusion

Honey is a promising new source of highly active EVs with exosomal origin, containing a number of antibacterial peptides as cargo molecules. Furthermore, the differential effect of HEC-EVs on S. mutans and S. sanguinis may serve as a novel biofilm-modulating strategy in dental caries.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy, honey, biofilms, dental caries

Introduction

Despite multiple efforts, dental caries continues to be a highly prevalent pathology across populations worldwide. Caries is considered a multifactorial disease with a strong microbiological component, associated to the dysregulation of resident microbiota within the dental biofilm.1 This dysregulation is mostly determined by the dominance of crucial acid-producing bacteria, such as Streptococcus mutans, over non-acidogenic species of oral streptococci.2,3 As a result, increased acidification of the dental biofilm can lead to the progressive demineralization of the underlying tooth surface resulting in cavitation and progression of the disease.4 On the other hand, the commensal Streptococcus sanguinis has been described as an important antagonistic species to S. mutans, and its prevalence within the biofilm is mostly associated to healthy conditions.5–7 Thus, current efforts to prevent and control dental caries are focused on finding novel approaches such as selectively targeting S. mutans over S. sanguinis and other non-acidogenic strains.

In recent years, Apis mellifera honeybee-derived products such as honey and royal jelly have shown promise as novel antibacterial agents against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Honey is a product generated by adult worker bees from flower nectar and different enzymes obtained from secretions of salivary glands, mainly the hypopharyngeal glands.8,9 In the past, the antibacterial effect of these substances has been mostly attributed to compounds such as methylglyoxal and peroxide, as well as factors such as pH and osmolarity.10,11 Recently, our group has demonstrated for the first time the presence of exosome-like extracellular vesicles (EVs) in A. mellifera products such as royal jelly, bee pollen and honey.8 These EVs were found to be in the size range <150nm and display interkingdom effects, such as influencing human mesenchymal stem cell migration, as well as antibacterial and antibiofilm effects on the model Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus.8 This promising antibacterial effect was also observed for bee-derived EVs released from type-I collagen matrixes, further displaying their potential as therapeutic agents for biofilm control.12 Despite demonstrating the presence of EVs in bee-derived products, and their effect on human and bacterial cells, questions remain regarding their specific cargo as well as the mechanisms behind their observed antibacterial and antibiofilm effect. Furthermore, their potential effect on other Gram-positive biofilm-forming bacteria such as S. mutans and S. sanguinis has not yet been explored. Overall, the use of honey-derived EVs against relevant oral streptococci strains may potentially aid in developing novel approaches for the prevention and treatment of dental caries.

Thus, the aim of this investigation was to characterize the molecular and nanomechanical properties of A. mellifera honey-derived EVs in order to elucidate the mechanisms behind their antibacterial effect, as well as to determine their antibiofilm properties against the relevant caries-associated S. mutans.

Materials and Methods

Honey Samples and Extracellular Vesicle Isolation

Apis mellifera monofloral honey from Eucryphia cordifolia (HEc) was obtained in crude, unprocessed form from controlled, organic beekeepers in Chile (Terra Andes, Chile). Honey samples were initially diluted 1:20 in particle-free phosphate-buffered saline (pf-PBS), and centrifuged at 500 x g, 1500 × g and 2500 × g for 15 min each. Subsequently, supernatants were filtered (0.2 µm) and ultra-centrifuged 100,000 × g for 60 min (Hanil 5 ultracentrifuge, Hanil). The final EV-containing pellet was resuspended in pf-PBS and stored at −80°C until experimentation (HEc-EVs, Figure 1A).

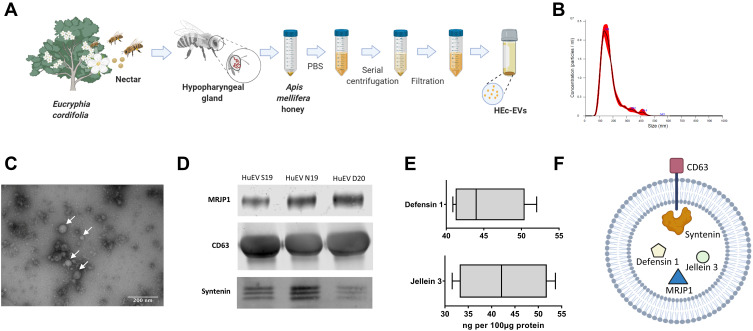

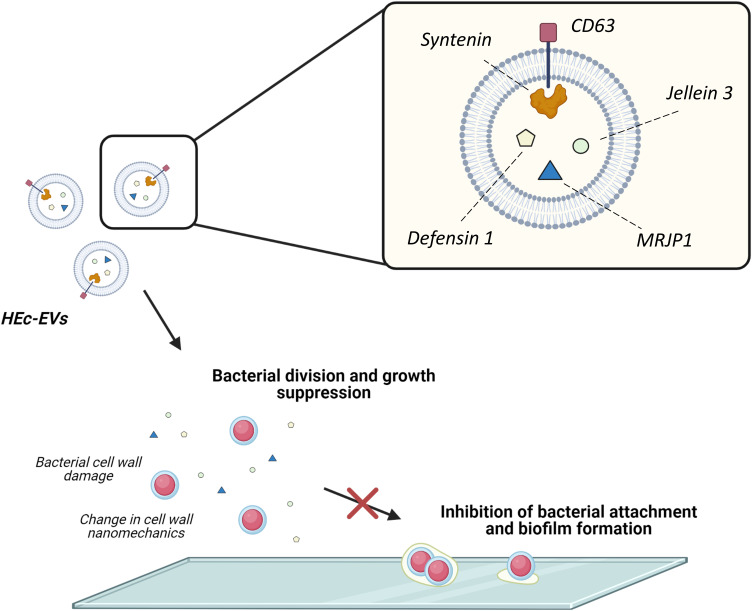

Figure 1.

Morphological and biochemical characterization of Apis mellifera HEc-EVs. (A) Schematic representation of HEc-EV extraction and isolation from monofloral A. mellifera honey utilizing ultracentrifugation (UC). Created with BioRender.com. (B) Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) demonstrating particle sizes mostly <150 nm, with a mode of 138 nm. (C) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of HEc-EVs confirming the presence of isolated vesicles. (D) Western blot analysis for Major Royal Jelly Protein-1 (MRJP1), CD63 and Syntenin obtained from three independent HEc-EV isolations, and (E) ELISA quantification for Defensin-1 and Jellein-3. (F) Diagrammatic depiction of the structure of HEc-EVs, including the antibacterial cargo molecules MRJP1, Defensin-1 and Jellein-3, and surface markers CD63 and Syntenin. Created with BioRender.com.

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Imaging of Isolated Honey-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

As a first step, isolated HEc-EVs were characterized for size distribution using nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA; NanoSight NS 3000, Malvern, UK). HEc-EVs were diluted 1:100 with pf-PBS and measured at 25°C (temperature controlled), at camera level 8 and detection threshold 3 for 30 seconds. Every sample was measured 5 times for 30 seconds.

To confirm vesicle presence, HEc-EVs were further visualized under a Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), using carbon-coated copper meshes and uranyl acetate counterstaining, as previously described.8

Analysis of Cell Surface Markers and Cargo Proteins

To determine MRJP1 cargo and to verify exosomal origin, HEc-EVs were analyzed for presence of tetraspanin CD63 and syntenin using Western Blot. For cargo analysis, HEc-EVs were sonicated for 15 min prior to analysis. Proteins were separated in reducing conditions (syntenin) and non-reducing conditions (CD63) utilizing a 10% polyacrylamide gel. After blotting onto nitrocellulose, membranes were blocked over night with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and subsequently incubated with respective antibodies (anti-CD63, 1:500, mouse monoclonal, Abcam; anti-syntenin, 1:1000, rabbit polyclonal, Abcam; anti-MRJP1, 1:1000, rabbit polyclonal, Cusabio) in 5% BSA overnight. Finally, membranes were thoroughly washed and incubated with secondary antibody (IR-Dye anti mouse, 1:15.000, LiCor; IR-Dye anti-rabbit, 1:15.000, LiCor), in 5% skim milk for 1 hour. For imaging, an Odyssey CLx imaging system was used, and results were analyzed with image studio lite version 5.2.5.

Peptides defensin-1 and jellein-3 were quantified with direct ELISA. HEc-EVs were sonicated for 15 min and protein concentration measured with BCA assay (Pierce, US). One microgram of HEc-EV protein as well as defensin-1 and jellein-3 peptides (standard: 1µg/mL to 7.8ng/mL, GeneCust, France) and negative controls (pre-bleed serum 1:1000, human mesenchymal stem cell protein 30 µg) were incubated overnight on a high binding 96-well polystyrene plate (R&D systems, US). Subsequently, plates were washed and blocked with 5% BSA for 2 hours. Plates were incubated with respective detection antibodies diluted in reagent diluent (R&D systems) (anti Apis mellifera defensin-1, 50 ng/mL; rabbit polyclonal, GeneCust; anti Apis mellifera jellein 3; 50 ng/mL, rabbit polyclonal, GeneCust) for 2 hours. HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody was used at a dilution of 1:1000 (Cell signalling, UK), and developed for 10 min using substrate solution (R&D systems). After addition of 2N H2SO4, plates were measured in a microplate reader (Tecan Sunrise,Tecan, Austria) at 450nm.

Non-Destructive Immobilization of Honey-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Bacteria for Atomic Force Microscopy Experiments

For AFM-based experiments, freshly cleaved 12-mm diameter mica discs (Electron Microscopy Sciences, US) were coated with 50 µL of a 0.1 M solution of poly-L-lysine (PLL, Sigma) for 5 minutes, washed 3x with ultrapure H2O and dried under a gentle stream of N2. Subsequently, a 50μL droplet of either HEc-EVs solution or bacterial suspension was incubated on the PLL-coated mica for 30 minutes at room temperature. Substrates were then washed 3x with ultrapure H2O, and experiments were carried out on the AFM immediately after sample preparation.

Atomic Force Microscopy Imaging and Nanomechanics of Honey-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

For all AFM imaging, an Asylum MFP 3D-SA AFM (Asylum Research, US) was utilized in intermittent contact mode (AC mode) with TAP300GD-G cantilevers (BudgetSensors, Bulgaria), obtaining height, amplitude, and phase channel images of substrates in air. For HEc-EV nanomechanical analysis, individually calibrated MNSL-10 cantilevers (0.1N/m, Bruker, US) were employed to obtain force-distance curves on the surface of selected EVs in buffer, with a soft loading force of 0.5nN and a 2µm/s rate. HEc-EVs from three independent sample preparations were utilized for all AFM-based experiments.

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

For all experiments and assays, Streptococcus mutans UA159 (ATCC® 700610) and Streptococcus sanguinis SK 36 were grown on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar (BD, USA) and Columbia agar supplemented with 5% blood respectively at a temperature of 37°C and 5% CO2.

Bacterial Growth and Biofilm Inhibition by Honey-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

To determine the effect of HEc-EVs on growth and biofilm inhibition, we utilized an adaptation of a previously published approach.8 Briefly, 5×104 colony forming units (CFU) of either S. mutans or S. sanguinis were inoculated into a 96-well plate with HEc-EVs at ratios of 5:1, 1:1, 0.5:1 and 0.1:1 vesicles per CFU, in a total volume of 100 µL per well (in BHI supplemented with 1% sucrose). Bacteria were then incubated in a multimodal microplate reader (Synergy HT, Biotek, USA) for 24 hours at 37°C, and hourly measurements of absorbance at OD630 were utilized for growth curve tabulation. For determining the antibiofilm effect of HEc-EVs, 24-hour-old biofilms in 96-well plates were gently washed with 1xPBS to eliminate unbound cells, dried, stained with a crystal violet solution (0.1% in dH2O) for 1 h, and washed with dH2O.8 Subsequently, after a 30-minute wash with 95% ethanol, supernatants were transferred to a fresh 96-well plate and biofilm biomass was determined by absorption at 570 nm.

Nanoscale Bacterial Characterization After Honey-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Exposure

Similar to HEc-EV AFM experiments, control and HEc-EV-treated bacterial cells were initially imaged in intermittent contact mode, obtaining 3×3 µm scans of immobilized S. mutans and S. sanguinis. From resulting scans, bacterial cell and septum roughness (RMS) calculations were carried out with Gwyddion v2.56 software. Furthermore, for S. mutans, force-distance curves were obtained on the surface of individualized bacterial cells with calibrated TAP300GD-G cantilevers, with a loading force of 3nN and a 2µm/s rate.

Data and Statistical Analysis

All data was tabulated and analyzed utilizing GraphPad Prism 9. After outlier detection and normality determination, statistical significance was assessed with either t-test or ANOVA tests, considering a significance value of p<0.05. Young´s modulus were calculated from resulting data utilizing the Derjaguin, Muller, and Toporov (DMT) model in proprietary Asylum Research AFM software (v. 16.10.211). AFM image visualization was performed in the Gwyddion v2.56 software.

Results and Discussion

Honey-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Contain Antibacterial Cargo and Specific Exosomal Markers

Recent reports from our group have demonstrated the presence of EVs in Apis mellifera bee-derived products such as royal jelly and honey.8,12 In the present study, EVs from a monofloral source of honey such as Eucryphia cordifolia (Ec) were isolated employing a similar ultracentrifugation-based approach (HEc-EVs). These vesicles were found to be mostly in the size range of <150nm, with a mode of 138nm (Figure 1B), consistent with previous reports of exosome-like EVs derived from bee products.8 TEM imaging confirmed the vesicle morphology of isolated particles with sizes mostly in the <100nm range (Figure 1C), which was also confirmed by AFM intermittent-contact mode.

To date, there are no reports verifying the exosomal origin of honey-derived extracellular vesicles. Typical exosomal markers are tetraspanins (eg, CD63, CD81, CD9) and molecules associated to biogenesis of exosomes (eg, Alix, syntenin, clathrins). However, most exosome markers have been defined for mammalian cells, and with the field of insect exosomes just recently being discovered, exosomal markers that may also be conserved in honeybee cells have not been defined yet. Differences between the mammalian and insect kingdom have to be considered in the search for kingdom-specific exosomal markers, since for example honeybees are lacking the tetraspanin CD81.13 We were able to identify two conserved exosome markers in honeybees: CD63 and syntenin (KEGG: exosome: Apis mellifera; entry 552721 CD63; entry 551650 syntenin) and could verify their presence in HEc-EVs (Figure 1D). CD63 and syntenin are an important part of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery, with syntenin recruiting CD63 in early endosome formation,14,15 demonstrating the exosomal origin of the isolated HEc-EVs.

As cargo proteins we were able to identify MRJP1, defensin-1 and jellein-3 (Figure 1D and E). MRJP1 is the most abundant protein in honey and plays an important role in honeybee development, and has demonstrated a number of interesting characteristics in regenerative medicine including wound healing, anti-cancer effects and immune modulation.16 Recent reports have also demonstrated its antibacterial properties against a range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.16,17 It is believed that the antibacterial effect of MRJP1 is due to its ability to alter cell permeability and induce bacterial membrane lysis.18 Furthermore, jellein-3 is a well-described short antimicrobial peptide (AMP) of 9 amino acid residues19 that has shown an important antibacterial effect on Gram-positive cocci.19 We also found defensin-1, another important bee-derived peptide with antibacterial properties, as cargo in HEc-EVs20,21 (Figure 1F). Several mechanisms are believed to explain the action of AMPs, the most important of these being a direct effect due to membrane disruption of bacterial cells via pore formation, stiffening, or reorganization of the membrane amongst other mechanisms (reviewed by22,23).

Atomic Force Microscopy Characterization of Honey-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Their Nanomechanical Properties

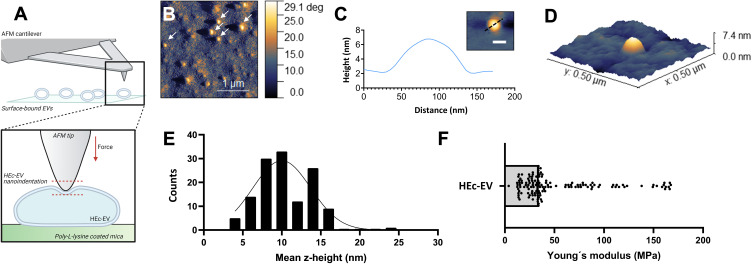

Following microscale and molecular analysis, the nanoscale topographical and mechanical properties of HEc-EVs were explored with AFM (Figure 2A). For this, individualized HEc-EVs were effectively immobilized onto PLL-coated mica surfaces throughout experimentation for both AFM imaging and nanoindentation (Figure 2B). HEc-EVs were found to display a similar morphology and size (<100nm diameter) to EVs from other sources,24 with a stretched out half-spherical shape due to the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged PLL and EVs (Figure 2C and D). Due to this stretching out effect, the mean height for immobilized vesicles was found to be 10.34 ± 3.3nm (Figure 2E), which is consistent with previous reports for EVs.24

Figure 2.

Nanoscale characterization of the morphology and nanomechanical properties of HEc-EVs with atomic force microscopy (AFM). (A) Diagrammatic representation of HEc-EV immobilization onto poly-L-lysine (PLL) coated mica surfaces, and subsequent nanoindentation with AFM. Created with BioRender.com. (B) Phase contrast image, (C) surface profile and (D) 3D reconstruction (from height image) of immobilized HEc-EVs on PLL-coated mica surfaces. (E) Histogram of the mean z-height of immobilized HEc-EVs (curve represents Gaussian fit) showing average height to be ~10 nm. (F) Young’s modulus of nanoindented HEc-EVs, obtained by applying the Derjaguin, Muller, and Toporov (DMT) model, demonstrating elasticity values mostly below 100 MPa.

Subsequently, AFM nanoindentation was utilized to determine the elastic properties of immobilized HEc-EVs. A reduced loading force of 0.5nN was utilized in order to preserve the structural integrity of EVs and avoid rupture of vesicles during experimentation. Overall, the majority of immobilized HEc-EVs were found to have Young´s modulus values <50MPa, with a median of 34.19MPa (Figure 2F). This is the first report to characterize the elasticity of honey-derived EVs, but comparisons can be made with the elasticity of EVs from other sources in literature. For example, Whitehead et al demonstrated that the elastic modulus of human malignant bladder cell-derived EVs were mostly in the ~95–280 MPa range.25 Furthermore, Zhang et al found elasticity values for human-derived EVs to be in the range of 25–400 MPa, with a subpopulation of large-exosome vesicles (mean diameter = 147.8 nm) ranging from ~26–73 MPa.24 Interestingly, elasticity of HEc-EVs ranged between ~3–165 MPa with the majority of vesicles falling in the ~25–75 MPa range. This observation suggests that HEc-EVs (size mode 138 nm) share remarkably similar nanomechanical properties to human EVs in the same particle size range, and could potentially explain previous observations that honey-derived EVs have a functional effect on human cells such as increased migration.8 This is strengthened by recent observations that nanoparticle elasticity influences cellular uptake, and it is believed that this property remains true for EV internalization into cells.26,27 Overall, the present study probes into the nanometrology of bee-derived EVs and suggests that EVs across different kingdoms and species conserve similar topographical and nanomechanical properties at the nanoscale.

Honey-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Show Selective Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Properties Against Relevant Oral Streptococcal Strains

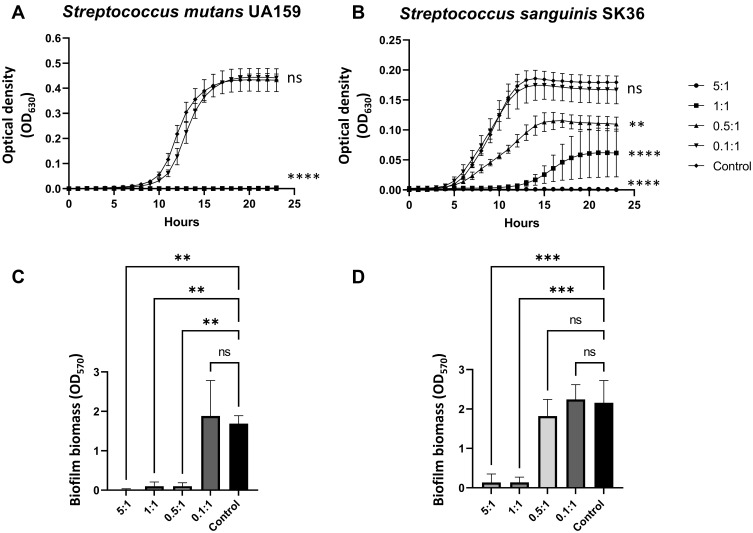

As previously mentioned, the bee-derived molecules MRJP1, jellein-3 and defensin-1 were found contained as cargo within HEc-EVs, all of which are known to exert important antimicrobial properties.17,19,20 Thus, to assess the effect of isolated HEc-EVs on the bacterial growth of relevant oral streptococci, Streptococcus mutans UA159 and Streptococcus sanguinis SK36 were grown in the presence of increasing concentrations of EVs. Both of these species are crucial tooth surface colonizers within the pathogenesis of dental caries, where the predominance of S. mutans over S. sanguinis is vital for disease progression.1 For experiments, a previously published approach was utilized to standardize EV concentrations as a ratio between EVs and bacteria.8 Thus, streptococci were grown in BHI in ratios of either 5, 1, 0.5 or 0.1 HEc-EVs per bacterial cell (Figure 3A and B). For S. mutans UA159, ratios of 5:1, 1:1 and 0.5:1 were found to completely inhibit bacterial growth after a 24-hour incubation period. However, for S. sanguinis SK36, only the higher 5:1 ratio of HEc-EVs was found to impede growth, as the 0.1:1, 0.5:1 and 1:1 ratios showed varying bacterial growth after 24-hour incubation times (Figure 3B). Previous work showed a growth inhibitory effect of honey-derived EVs against another gram-positive species, Staphylococcus aureus, at a ~1:1 ratio and biofilm growth inhibition at a 10:1 ratio,8 suggesting that honey-derived EVs have an antibacterial effect on several strains of Gram-positive bacteria.8 Most importantly, the present data demonstrates that despite displaying an antibacterial effect on both strains of oral streptococci, HEc-EVs have a pronounced activity against S. mutans compared to S. sanguinis.

Figure 3.

Antibacterial and antibiofilm properties of HEc-EVs against Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis. 24-hour growth curves for (A) Streptococcus mutans UA 159 and (B) Streptococcus sanguinis SK 36 in the presence of increasing ratios of HEc-EVs. Ratios represent HEc-EVs: CFU (Colony Forming Units). Results expressed as mean ± SEM (**p<0.01, ****p<0.0001, compared to control; two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; n=3, 3 technical replicates per group). Biofilm biomass assays for 24-hour growth for (C) S. mutans UA 159 and (D) S. sanguinis SK 36. Overall, results show a differential effect of HEc-EVs against both oral streptococci, with a pronounced inhibition of S. mutans UA 159 growth and biofilm formation compared to S. sanguinis (results shown as mean ± SD, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; n=3, 3 technical replicates per group).

Furthermore, as dental caries is a biofilm-mediated disease, it is important to not only assess the inhibitory effect of HEc-EVs on bacterial growth but also their potential antibiofilm capacity. Thus, the effect of HEc-EVs on S. mutans UA159 and S. sanguinis SK36 biofilm establishment after 24-hour incubation times was also assessed. For S. mutans, biofilm formation was only observed at the 0.1:1 ratio (Figure 3C), which is consistent with the growth data seen in Figure 3A. S. sanguinis, on the other hand, displayed biofilm formation in the presence of 0.1:1 and 0.5:1 ratios that was comparable to the positive control. This suggests that despite showing some level of growth inhibition, S. sanguinis can still adhere to the surface and establish an early biofilm when exposed to lower concentrations of HEc-EVs (Figure 3B and D). However, although allowing some growth of S. sanguinis in solution, increased ratios of 1:1 EV: CFU completely inhibit its ability to form biofilm on the surface. Overall, this effect of HEc-EVs on S. mutans could potentially aid in the development of novel approaches against dental caries. Similar investigations are already being performed for other antibacterial compounds such as D-cysteine and other free D-amino acids.5,28 Future work in this field should focus on exploring the impact of honey-derived EVs on dual or multispecies biofilm formation, in order to confirm the differential effect observed between S. mutans and S. sanguinis within the context of caries biofilm formation.

Nanoscale Honey-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Induced Alterations on S. mutans and S. sanguinis

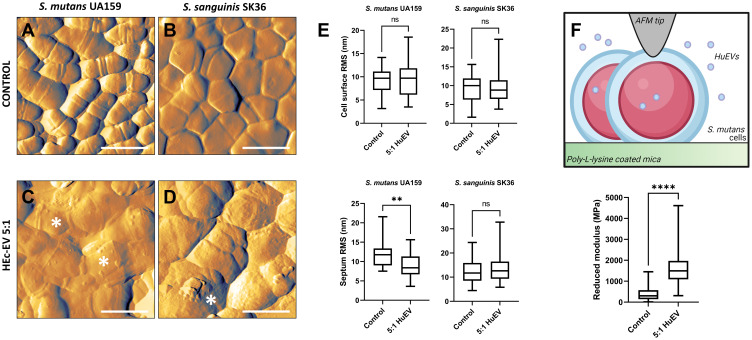

Finally, the effect of HEc-EVs on oral streptococci was also assessed at the nanoscale, by employing AFM-based approaches. Following incubation with a 5:1 ratio of HEc-EV, both S. mutans and S. sanguinis were immobilized onto PLL-coated mica and imaged with intermittent contact mode to avoid damaging the bacterial surface or dislodging cells due to strong lateral scanning forces. For both strains, control bacteria were observed with a very defined morphology and marked division features, such as septa (Figure 4A and B). On the other hand, bacteria treated with HEc-EVs displayed an altered and irregular morphology, where cells appear enlarged, with a less pronounced division septa and the presence of wrinkling and other features consistent with cell damage and surface disorganization (Figure 4C and D, asterisks). These nanomorphological changes are consistent with the membrane disruption effect expected from AMPs observed with AFM in previous reports.29 Furthermore, Orasmo et al analysed the effect of the antibacterial triclosan on S. mutans with AFM, reporting similar nanoscale morphological alterations including cell wrinkling and irregular surface morphology.30 As one of the main mechanisms behind the antimicrobial effect of triclosan is bacterial membrane disruption, our AFM observations suggest that HEc-EVs may generate direct membrane damage on S. mutans cells. Similar AFM morphological observations reported by Cross et al when analyzing S. mutans cells defective in glucosyltransferases (Gtfs) also showed flattening of cells and loss of division septa as main cellular changes.31

Figure 4.

AFM-based nanocharacterization of oral streptococci after HEc-EV exposure. (A and B) Control and (C and D) HEc-EV-exposed (5:1 ratio) S. sanguinis and S. mutans cells, respectively, immobilized to PLL-coated mica surfaces and imaged with intermittent contact AFM (1 µm scale bars). Images show clear markers for bacterial wall disruption such as flattening, swelling, loss of dividing septa, and surface disorganization (asterisks). (E) Nano-roughness analysis (RMS) of the cell surface and dividing septa regions, confirming a significative reduction of septa roughness following HEc-EV exposure for S. mutans UA 159 (**p<0.01; Mann–Whitney test, 30 cells per group). (F) Diagrammatic representation of AFM nanoindentation of PLL immobilized S. mutans cells, demonstrating a significative increase in elastic modulus following incubation with a 5:1 ratio of HEc-EVs (****p<0.0001; Mann–Whitney test, 150 force-curves per group). Created with BioRender.com.

To further characterize bacterial topographical changes, nanoroughness measurements on the surface of individualized bacterial cells was performed, confirming reduced roughness values for the septa of HEc-EV-treated S. mutans (8.39 nm) compared to controls (11.75 nm; p<0.01, Mann–Whitney test), but not for S. sanguinis. A reduced roughness in the septal region potentially suggests that HEc-EV exposure may decrease cell division in S. mutans (Figure 4E), and further confirms an increased susceptibility of S. mutans to HEc-EVs compared to S. sanguinis. Subsequently, nanomechanical changes in S. mutans following HEc-EV treatment were determined by indenting surface-bound cells with 3nN loading forces (Figure 4F). Results showed that HEc-EV treated S. mutans was found to have a significant increase in Young´s modulus compared to control bacteria (p<0.0001, Mann–Whitney test), further supporting the hypothesis that HEc-EV exposure significantly alters cell wall morphology and properties in S. mutans (Figure 5). Previous research has demonstrated that AMP exposure can increase stiffness of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial membranes,32,33 but further research is necessary to elucidate the particular effect of honey-derived EVs on streptococcal elastic properties.

Figure 5.

Proposed effect of HEc-EVs on oral streptococci. Schematic representation of the effect of HEc-EVs including growth suppression and inhibition of bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation onto surfaces. Created with BioRender.com.

Conclusions

Summarizing, our findings confirm the presence of extracellular vesicles in a Chilean monofloral honey derived from Eucryphia cordifolia. These extracellular vesicles contained cargo molecules unique to the honeybee origin and with known antibacterial properties, which displayed a pronounced effect on S. mutans and could be associated to nanomechanical alterations consistent with membrane damage. We would like to highlight that this is the first study reporting the exosomal origin of honey-derived EVs by identifying the conserved exosome markers CD63 and syntenin. Overall, the use of isolated honey-derived EVs may serve as a novel approach for modulating the microbiological aspect behind the onset of dental caries and other biofilm-mediated diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by FONDECYT Iniciacion grants #11180101 (SA) and #11180406 (CS), and by the Millennium Nucleus ICM-P10-035F (NPB). Authors would also like to thank the Pharmacology and Toxicology Laboratory, School of Dentistry, UNICAMP (Brazil) for providing the S. sanguinis SK 36 strain. Figures were created with BioRender.com.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD, et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3(1):17030. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loesche WJ. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50(4):353–380. doi: 10.1039/b801747f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsh PD. Microbial ecology of dental plaque and its significance in health and disease. Adv Dent Res. 1994;8(2):263–271. doi: 10.1177/08959374940080022001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemos JA, Palmer SR, Zeng L, et al. The biology of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7(1):10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0051-2018. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0051-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo X, Liu S, Zhou X, et al. Effect of D-cysteine on dual-species biofilms of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6689. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43081-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu B, Macleod LC, Kitten T, Xu P. Streptococcus sanguinis biofilm formation & interaction with oral pathogens. Future Microbiol. 2018;13(8):915–932. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2018-0043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng L, Itzek A, Chen Z, Kreth J. Oxygen dependent pyruvate oxidase expression and production in Streptococcus sanguinis. Int J Oral Sci. 2011;3(2):82–89. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuh CMAP, Aguayo S, Zavala G, Khoury M. Exosome-like vesicles in Apis mellifera bee pollen, honey and royal jelly contribute to their antibacterial and pro-regenerative activity. J Exp Biol. 2019;222:jeb208702. doi: 10.1242/jeb.208702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Sherif AA, Mazeed AM, Ewis MA, Nafea EA, Hagag ESE, Kamel AA. Activity of salivary glands in secreting honey-elaborating enzymes in two subspecies of honeybee (Apis mellifera L). Physiol Entomol. 2017;42(4):397–403. doi: 10.1111/phen.12213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Easton-Calabria A, Demary KC, Oner NJ. Beyond pollination: honey bees (Apis mellifera) as zootherapy keystone species. Front Ecol Evol. 2019;6(February). doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montenegro G, Mejías E. Biological applications of honeys produced by Apis mellifera. Biol Res. 2013;46(4):341–345. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602013000400005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramírez OJ, Alvarez S, Contreras-Kallens P, Barrera NP, Aguayo S, Schuh CMAP. Type I collagen hydrogels as a delivery matrix for royal jelly derived extracellular vesicles. Drug Deliv. 2020;27(1):1308–1318. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2020.1818880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang S, Yuan S, Dong M, et al. The phylogenetic analysis of tetraspanins projects the evolution of cell-cell interactions from unicellular to multicellular organisms. Genomics. 2005;86(6):674–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoorvogel W. Resolving sorting mechanisms into exosomes. Cell Res. 2015;25(5):531–532. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.David G, Zimmermann P. Heparanase tailors syndecan for exosome production. Mol Cell Oncol. 2016;3(3):e1047556. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2015.1047556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian W, Li M, Guo H, et al. Architecture of the native major royal jelly protein 1 oligomer. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1). doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05619-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brudzynski K, Sjaarda C, Lannigan R. MRJP1-containing glycoproteins isolated from honey, a novel antibacterial drug candidate with broad spectrum activity against multi-drug resistant clinical isolates. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:711. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brudzynski K, Sjaarda C. Honey glycoproteins containing antimicrobial peptides, jelleins of the major royal jelly protein 1, are responsible for the cell wall lytic and bactericidal activities of honey. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fontana R, Mendes MA, de Souza BM, et al. Jelleines: a family of antimicrobial peptides from the royal jelly of honeybees (Apis mellifera). Peptides. 2004;25(6):919–928. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bucekova M, Sojka M, Valachova I, et al. Bee-derived antibacterial peptide, defensin-1, promotes wound re-epithelialisation in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7340. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07494-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ilyasov R, Gaifullina L, Saltykova E, Poskryakov A, Nikolenko A. Review of the expression of antimicrobial peptide defensin in honey bees Apis mellifera L. J Apic Sci. 2012;56(1):115–124. doi: 10.2478/v10289-012-0013-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar P, Kizhakkedathu JN, Straus SK. Antimicrobial peptides: diversity, mechanism of action and strategies to improve the activity and biocompatibility in vivo. Biomolecules. 2018;8(1):4. doi: 10.3390/biom8010004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teixeira V, Feio MJ, Bastos M. Role of lipids in the interaction of antimicrobial peptides with membranes. Prog Lipid Res. 2012;51(2):149–177. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Freitas D, Kim HS, et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(3):332–343. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0040-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitehead B, Wu L, Hvam ML, et al. Tumour exosomes display differential mechanical and complement activation properties dependent on malignant state: implications in endothelial leakiness. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4(1):29685. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.29685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LeClaire M, Gimzewski J, Sharma S. A review of the biomechanical properties of single extracellular vesicles. Nano Sel. 2021;2(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/nano.202000129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anselmo AC, Mitragotri S. Impact of particle elasticity on particle-based drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;108:51–67. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong Z, Zhang L, Ling J, Jian Y, Huang L, Deng D. An in vitro study on the effect of free amino acids alone or in combination with nisin on biofilms as well as on planktonic bacteria of Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang C-H, Chen Y-C, Peng S-Y, et al. An engineered arginine-rich α-helical antimicrobial peptide exhibits broad-spectrum bactericidal activity against pathogenic bacteria and reduces bacterial infections in mice. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14602. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32981-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orasmo EAC, Miyakawa W, Otani C, Khouri S. In vitro AFM evaluation of Streptococcus mutans membrane exposed to two mouthwashes. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2013;3(9):024–028. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cross SE, Kreth J, Zhu L, et al. Atomic force microscopy study of the structure–function relationships of the biofilm-forming bacterium Streptococcus mutans. Nanotechnology. 2006;17(4):S1–S7. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/17/4/001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumagai A, Dupuy FG, Arsov Z, et al. Elastic behavior of model membranes with antimicrobial peptides depends on lipid specificity and d-enantiomers. Soft Matter. 2019;15(8):1860–1868. doi: 10.1039/C8SM02180E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang W-F, Chen S-H, Chen Y-F. Correlation of an antimicrobial peptide’s potency and its influences on membrane elasticity. Phys Rev E. 2018;98(4):42408. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.98.042408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]