Abstract

The musculoskeletal system is essential for maintaining posture, protecting organs, facilitating locomotion, and regulating various cellular and metabolic functions. Injury to this system due to trauma or wear is common, and severe damage may require surgery to restore function and prevent further harm. Autografts are the current gold standard for the replacement of lost or damaged tissues. However, these grafts are constrained by limited supply and donor site morbidity. Allografts, xenografts, and alloplastic materials represent viable alternatives, but each of these methods also has its own problems and limitations. Technological advances in three-dimensional (3D) printing and its biomedical adaptation, 3D bioprinting, have the potential to provide viable, autologous tissue-like constructs that can be used to repair musculoskeletal defects. Though bioprinting is currently unable to develop mature, implantable tissues, it can pattern cells in 3D constructs with features facilitating maturation and vascularization. Further advances in the field may enable the manufacture of constructs that can mimic native tissues in complexity, spatial heterogeneity, and ultimately, clinical utility. This review studies the use of 3D bioprinting for engineering bone, cartilage, muscle, tendon, ligament, and their interface tissues. Additionally, the current limitations and challenges in the field are discussed and the prospects for future progress are highlighted.

Keywords: Bone, 3D Bioprinting, Graft, Musculoskeletal, Tissue defects, Tissue Engineering

1. Introduction

The musculoskeletal system is very important for maintaining posture, providing protection for organs, providing anchor points for bipedal locomotion, and for supporting various cellular and metabolic functions. It is one of the most commonly affected systems by trauma [1, 2]. In many situations where musculoskeletal tissue is diseased or lost due to trauma or other pathologies, grafting is the only feasible option for restoring function. Autografts are the current gold standard and preferred method, but they unfortunately have a limited supply and often lead to donor site morbidity [3–6]. Allografts and xenografts represent viable alternatives, but these also suffer from issues involving immune-incompatibility, risk of rejection, and transmission of infectious agents [7, 8]. To solve these transplantation issues, alloplastic materials were developed. These alloplastic materials, however, are abiotic materials and likewise often fail to integrate into the transplantation site and can sometimes lead to infection [9].

Recent developments in tissue engineering allow for the fabrication of tissues using scaffolds that are subsequently seeded with cells [10, 11]. However, cells are rarely distributed in a homogenous manner leading to a failure in producing functional constructs that can be successfully integrated with host tissue [7, 12]. Additionally, the tissues’ lack of vascularization ultimately leads to the tissue failing in its function once implanted in vivo [12–14]. The advent of three-dimensional (3D) printing and its subsequent adaptation to 3D bioprinting present a solution to the issue of irregular cell distributions in scaffolds as constructs can now be created with a homogeneous cell distribution [15–17]. Recent advances now allow for the development of vascularized constructs in which endothelial cells are used [18]. Unfortunately, most available biomaterials suitable for 3D bioprinting can only support cells for 2–3 weeks. After this period, constructs lose their structural integrity and collapse [10, 17], making them unsuitable for clinically treating tissue defects. This is especially true in demanding tissues such as musculoskeletal structures like bone [17]. While biological materials are favored by cells (e.g. collagen possesses arginylglycylaspartic acid (RGD) sequence which is important for cell attachment, spreading, and function), they generally lack the mechanical properties required of a tissue for in vitro and in vivo applications [19]. Alternatively, synthetic materials can possess better mechanical properties and are able to be uniquely tuned to the material properties of a given construct. Unfortunately, synthetic materials are not as conducive to cell growth as biological materials. Thus, by integrating biological approaches and engineering methods, it is now possible to combine the properties of both biological and synthetic materials using new 3D printing techniques [20, 21]. For example, multimaterial 3D printing approaches have enabled the printing of hard and osteoconductive biomaterials, such as polycaprolactone (PCL) and tricalcium phosphate (TCP), in conjunction with cell-laden bioinks to provide the combination of mechanical strength and bioactivity in the printed constructs [11, 22, 23]. Additionally, coaxial 3D printing techniques have been developed for the simultaneous printing of two separate inks that can include acellular osteoconductive bioceramics and cell-laden hydrogels for osteogenic activity [24]. Moreover, different 3D printing techniques have been successfully combined to print materials of different properties including, cell-laden hydrogels and mechanically strong synthetic biomaterials for hard tissue engineering [25].

In this review, we look at studies involving the development of 3D bioprinting for bone, cartilage, muscle, tendon, and ligament in addition to studies demonstrating attempts to develop a combination of tissues such as osteochondral or muscle-tendon-bone attachment. Various limitations and current challenges are discussed and ideas for future development are highlighted (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the materials and techniques used for the bioprinting of musculoskeletal tissues and their interface. Polycaprolactone (PCL), poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), Poly(ethylene glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA), Bone marrow derived Mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs), Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Hyaluronic acid (HA), Mouse-derived stem cells (MDSC), Polyglycolide (PGA), Photosensitive polyurethane (PU), Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), Polylactide (PLA) , and Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS).

2. Three-Dimensional Bioprinting

2.1. General overview of 3D bioprinting methods

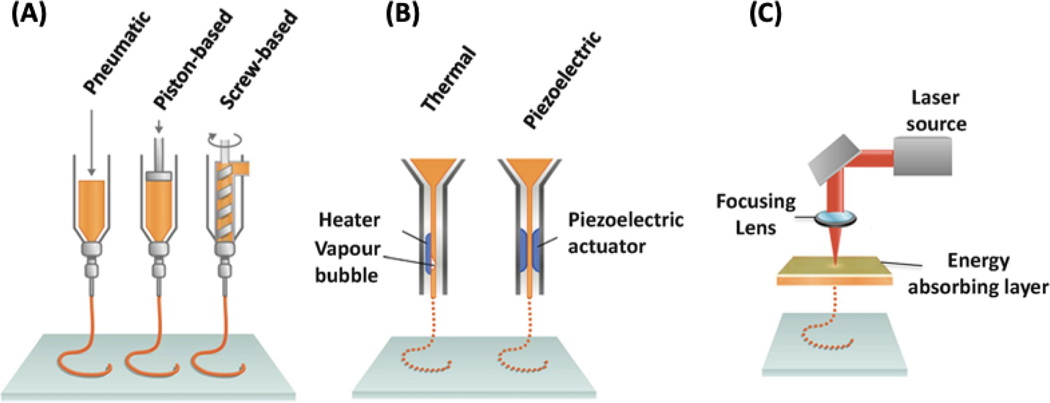

Bioprinting can be defined as the process by which living constructs are produced in a controlled fashion by using cellular-based bioinks [26]. Like standard 3D printing, the process begins with a computer designed file of the construct which is sliced into discrete layers. Despite similar up-front processes, several techniques have been developed to deposit the materials. The most notable of these techniques are extrusion-based, inkjet, and light-based printing (Figure 2) [15, 16, 27].

Figure 2.

The three most common 3D bioprinting techniques: (A) microextrusion (consisting of pneumatic, piston-based, and screw-based) (B) inkjet (consisting of thermal and piezoelectric), and (C) laser-assisted bioprinting. Adapted from Pountos et al. [28] with permission from Springer.

Extrusion-based 3D bioprinting is ubiquitously used for bioprinting and is implemented by most commercially available systems. These systems all rely upon applying pressure (mechanical or pneumatic) to a reservoir of bioink to force material out of a printhead (often a needle tip). The precision of extrusion printing has been improved by introducing microfluidic printheads in place of traditional reservoirs [29, 30]. Microfluidic heads allow better control over the material composition being used as well as the ability to crosslink the material while printing using core-shell fluid flows. In all cases of extrusion-based bioprinting, the result is the formation of a fiber of material that can be patterned by moving the printhead of the machine across the print area. After each layer is completed, the distance between the print surface and extrusion tip is increased and the subsequent layer begins printing [31]. Most hydrogels, particularly alginate, gelatin, chitosan, hyaluronic acid (HA), Pluronic F-127, and polyethylene glycol (PEG), can be printed with extrusion bioprinters. Additionally, these materials can contain high cell densities while maintaining printability and cell viability [26, 32].

Inkjet printing has a similar patterning methodology as the printhead moves laterally to pattern each layer and vertically to produce new layers. However, the expulsion of material occurs in discrete packets rather than in continuous fibers [33]. This 3D printing technology was the first developed 3D bioprinting technique as it is based on the same concept as conventional 2D inkjet printing [34]. First, cells and a hydrogel prepolymer solution are combined in an ink cartridge, which in turn is connected to a printhead. This printhead deposits the bioink material during the printing process. During the printing, printer heads are deformed by a piezoelectric actuator or a thermal process and squeezed to create droplets of varying sizes [35]. Thermal inkjet printers rely on rapid, local temperature changes near the emission tip to form bubbles and output precise droplets of bioink. Piezoelectric heads are composed of a special material that alters its shape when a voltage is applied to create uniform droplets of material for deposition. Finally, pressure-driven systems can achieve the same effect by intermittently applying pressure to the fluid reservoir. Few commercial systems use inkjet bioprinting; however, many systems have been developed in academia [36–38].

Light-based bioprinting encompasses a wide array of subcategories – all of which use light to deposit or solidify material. Most common among these is stereolithography (SLA). Stereolithographic bioprinting systems have only recently been developed in academia [39–42] and are now becoming commercially relevant as printers. These systems use laser light to crosslink polymer solutions and form the desired constructs. The light is used to crosslink the desired pattern onto each layer, fixing each layer to the previous one. This often results in the appearance of a solid printed construct being pulled out of a pool of solution. Another light-based method is laser-assisted printing. This technology eliminates direct contact between the dispenser and bioinks as it consists of a glass plate coated on one side with an energy absorbing layer and with bioinks on the other side [43]. The ink is deposited from the substrate where the laser hits the energy absorbing layer. With this technique, the resolution is limited by the uniformity of the bioink on the glass surface as aggregation can lead to undesirable heterogeneities. While light-based printing technologies have several desirable properties, the generation of clinical 3D constructs is time intensive and has limited the widespread adoption of this technology thus far [27, 44].

Overall, each bioprinting technique comes with its own advantages and drawbacks (see Table 1). Extrusion-based and inkjet printer techniques are often more rapid; however, they generally have lower resolution than laser-based methods. With respect to musculoskeletal tissue engineering, extrusion-based methods are widely adopted as the high pressure applied in these techniques can assist in the deposition of highly viscous biomaterials and creation of elongated fibers, which are a common structure within musculoskeletal tissues [45].

Table 1.

Advantages and limitations of different bioprinting techniques. Reproduced from Heinrich et al. [46] with permission from Wiley, Murphy and Atala [26] with permission from Nature Publishing Group, and Ashammakhi et al. [17] with permission from Wiley.

| 3D bioprinting technique | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Extrusion‐based bioprinting | – Comparatively simple bioprinting process – Applicability of multimaterial bioprinting – Printability of highly viscous bioinks (30–6 × 107 mPa s−1) – Printability of high cell densities (including cell spheroids) -Relatively low printing cost |

– Low to medium resolution highly dependent on setup – Moderate cell viability (40–80%) dependent on setup – Low printing speed |

| Inkjet bioprinting | – Simple bioprinting method – Applicability of multimaterial bioprinting – High resolution (≈30 µm) – High cell viability (80–90%) -High printing speed – Low cost |

– Limited to bioinks with viscosity of 3.5– 12 mPa s−1 – Limited to low cell density (<106 cells mL−1) |

| Laser‐assisted bioprinting | – Variety of printable bioinks with viscosity of 1–300 mPa s−1 – Applicability of micropatterning of cells and biomolecules due to high printing resolution – High cell viability (>95%) –Medium to fast printing speed |

– Complex system – Limited to low cell density (<106 cells mL−1) – Comparatively high costs |

| Stereolithography | – Simultaneous crosslinking of the entire 2D layer avoids need of X‐Y movement – Applicability of multimaterial bioprinting – High variety of printable bioinks from low to high viscosities – High resolution of bioprinting (≈1 µm) – High cell viability (>85%) – High printing speed |

– Comparatively complex system – Crosslinking requires transparent and photosensitive bioink, limiting choice of additives and cell density (108 cells mL−1) -High printing cost |

2.2. Bioinks

In general, hydrogels for bioprinting can be categorized into two groups, naturally-derived biomaterials (collagen, gelatin, fibrin, HA, silk proteins, chitosan, alginate) and synthetic polymers (polylactide (PLA), poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), and PEG diacrylate (PEGDA)) [47]. Naturally-derived biomaterials possess biochemical and biophysical properties similar to extracellular matrix (ECM). These similarities lead to naturally derived biomaterials having strong biocompatibility as they support cell adhesion, proliferation, migration, and differentiation. Despite these advantages, natural biomaterials face drawbacks in generally being mechanically weak and being difficult to consistently manufacture [19, 48]. Synthetic materials, however, can be reliably produced with little variation and be tailored to account for properties ranging from degradation rate, mechanical strength, general structure, and cell adhesion [49]. Unfortunately, synthetic polymers are often neither biocompatible nor conducive to cellular proliferation. However, synthetic polymers can be chemically modified with cell adhesive peptides such as RGD to increase cell adhesion and mimic chemical and physical elements characteristic to the ECM onto the substrates [50]. Similarly, synthetic modification to materials, such as alginate, can create a more realistic microenvironment in which cells are able to enzymatically degrade implanted modified alginate hydrogels [51]. For bioinks, hydrogel biomaterials are usually used to contain cells and any additive elements. Hydrogel bioinks are typically selected because of their highly viscous shear thinning and their properties of rapid crosslinkability [52]. Among them, gelatin has been used in fugitive and direct-write bioinks [53, 54]. Gelatin reversibly forms an alpha helix structure at temperatures below 30°C and can begin physical crosslinking in aqueous materials above 40°C [19, 55]. Moreover, gelatin possesses natural integrin-binding motifs, such as vitronectin, fibronectin, and vimentin, which promote cell attachment [19]. In particular, gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) is employed widely as a bioink due to its rapid crosslinking with the photoinitiator Irgacure 2959 through UV-light (360–480 nm) [54]. GelMA is also often combined with other materials or customized to form novel bioinks. For instance, Kolesky et al. fabricated a vascular-embedded tissue by using GelMA (15 wt%) and Pluronic F127 (40 wt%) hydrogel. In this study, GelMA was printed at temperatures below 23°C and helped to both form engineered ECM and carry cells [7]. Additionally, composite bioinks are often used to create specifically tailored bioinks possessing desired properties and recapitulating the complexity of native microenvironments. Composite bioinks can possess bioactive factors while also providing added mechanical strength through the coordination of multiple polymer or nanoparticle components in the bioink [56].

Alginate hydrogels are commonly used as a bioink because of their high viscosity, biocompatibility, and instant crosslinkability using multivalent cations (Ca2+ or Ba2+) [57]. However, alginate has a major drawback in that it has low biological activity [17]. Lately, alginate bioinks have been used to form a temporary bioprinted scaffold structure during the tissue formation time span of the bioprinted construct. Jia et al. developed a combination of alginate with PEG-tetra-acrylate (PEGTA) using a multilayered tri-axial nozzle system [32]. Here, the PEGTA increased the mechanical strength by increasing the crosslinking density (the 4-armed tetravalent structures provided multiple active crosslinking sites). After completing printing and ultraviolet (UV) crosslinking, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was used to dissolve the ionically crosslinked alginate.

In addition to biomaterial components, bioinks are also composed of cells and possible additive components such as growth factors. These cells are typically sourced from existing cell lineages [23], harvested from native tissues [58], or derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) or embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [59, 60]. Unfortunately, growth factors typically lack an appropriate controlled release system, leading to burst release of loaded growth factor and its rapid clearance from the delivery site [61]. To overcome this problem, growth factors can be loaded into a tuned matrix that can protect them from hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation and enable their controlled and sustained release. For instance, Poldervaart et al. showed that encapsulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in gelatin micro-particles achieved controlled growth factor delivery for three weeks and enhanced angiogenesis in the 3D printed scaffold [62]. In other studies, gradients of growth factors have been built into 3D bioprinted constructs to guide the growth of osteogenic and endothelial cells [10]. Likewise, bioinks present a unique opportunity to incorporate additional components, such as growth factors, that may influence the growth and differentiation of cells in the printed constructs. In the following sections, details of 3D bioprinted studies in relation to each tissue type will be discussed.

2.3. Print files from patients

A major benefit of bioprinting is the ability to customize the shape and size of the printed products to best suit the needs of individual patients. With this capability, methods for accurately and precisely mapping tissue defects to ensure proper fit are needed. The leading method for mapping soft tissue is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and X-ray and computed tomography (CT) [26]. In many cases, it is essential to quantify both the shape and density of the damaged tissue, as both have implications for the success of an implanted 3D bioprinted construct. High-resolution MRI is currently being integrated with clinical practice. The enhanced resolution and sensitivity that high resolution MRI provides will help to facilitate the bioprinting of personalized tissue constructs for orthopedic and craniofacial surgery [26, 63, 64].

3. Bone

3.1. Background

Every year approximately two million surgical procedures involving bone excision, bone grafting, and fracture repair are performed in the United States alone, making bone tissues the second most frequent tissue for transplantations [65]. Repairing a bone defect or fracture is a complex process as it requires the coordination of a variety of cells interacting with the ECM in addition to chemokines and/or cytokines found at the fracture site. The success of this process is imperative as it provides mechanical stability for the eventual development of a bone callus [66, 67]. Likewise, potential graft materials must provide adequate structural support to aid in healing bone defects or fractures. A variety of materials are currently available for forming grafts including polymers [68], cements, metallic materials [69], biocomposites [14], and bioceramics [70–72]. To be an ideal material for forming bone grafts, a given material must be biocompatible, fully resorbable, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive. Moreover, the material must also utilize an architecture resembling the native bone, be similar to the native bone in mechanical stability and osteogenic ability, while also being thermally nonconductive, sterilizable, and inexpensive to produce [8]. Thus, there exist stringent requirements to create expendable bone graft materials that are both functional and feasible for clinical applications. Currently, no material has been developed that is capable of fully satisfying these mentioned requirements for healing bone related injuries.

3.2. Bone 3D bioprinting

Bioprinting of hydrogel-based bone tissue engineering has been intensively investigated due to its tunability and the capability of encapsulating cells and biomolecules. Kim et al. developed a bioink consisting of gelatin and a poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) solution to engineer hard tissue-like scaffolds for bone repair at low temperature [73]. Increased mechanical strength was obtained by the addition of PVA into the gelatin scaffold. Various composition ratios of gelatin/PVA were tested to optimize bioprintability while also maintaining the porous structure. Ultimately, a scaffold ratio of 5:5 was determined to be most conducive to high cell viability and osteogenic differentiation. Lee et al. engineered a collagen-based silk-fibroin scaffold which exhibited ECM-like properties with a nanoporous structure using 3D bioprinting [74]. Because of highly concentrated ECM-like properties, the printed construct provided an extremely favorable environment for osteoblast differentiation during in vitro testing. However, the printed construct’s mechanical strength and compressive modulus were significantly weaker compared to human cancellous bone tissue. Using co-axial printing technology, Zhai et al. 3D bioprinted an osteoblast-laden PEGDA/HA scaffold containing nanoclay/nanocomposites [75]. The osteoblast-laden PEGDA/HA/nanoclay construct showed higher than 95% cell viability with an excellent osteogenic differentiation due to the release of silicon and magnesium ions within the scaffold. The osteogenic differentiation ability promoted both short and long-term in vitro culture, demonstrating the printed scaffold to be a suitable microenvironment for bone tissue regeneration. Moreover, Demirtas et al. also demonstrated successful 3D bioprinting of a bone tissue construct consisting of osteoblast-laden chitosan/HA hydrogels that showed the highest level of osteogenic differentiation compared to various hydrogels, such as alginate, chitosan and HA constructs [76]. The elastic modulus of the chitosan/HA construct was approximately 15 kPa (significantly softer than the elastic modulus of cancellous bone).

Inkjet bioprinting was used by Gao et al. to 3D bioprint bone constructs by co-printing acrylated peptides and acrylated PEG with marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [77]. After differentiation, the bioprinted bone niche demonstrated significantly high amounts of calcified mineralized matrix as well as possessing promising mechanical properties required for bone constructs. Additionally, the mechanical stiffness and complex structure of the bioprinted hydrogels showed a direct differentiation of MSCs toward osteogenic lineages [77, 78]. A multi-head tissue-organ building system (MtoBS) was developed for the fabrication of 3D heterogeneous bone and osteochondral tissue [79]. Here, the thermoplastic biomaterial polycaprolactone (PCL) was utilized to increase the mechanical strength of the bioprinted construct. Osteoblasts-laden alginate hydrogel solutions were infused into the bioprinted PCL framework, which demonstrated a development of bone tissues in multicellular arrangements. Additionally, composite bioinks have been proposed for use in bone bioprinting as they recapitulate a microenvironment conducive to the formation of a mineralized matrix. Ojansivu et al. worked to develop a wood-derived cellulose nanofibril composite bioink for extrusion-based bone 3D bioprinting. In their study, Ojansivu et al. determined that cellulose-based bioinks allowed for better flow controllability and ultimately resulted in enhanced printing resolution [80]. In another composite bioink study, Xavier et al. investigated the use of nanosilicate composites for bone tissue engineering applications. Although not a bioprinting study, the work of Xavier et al. served to study the mechanical and osteogenic properties of nanosilicate composite hydrogels. Ultimately, Xavier et al. found the nanosilicate hydrogel to have a compressive modulus four times greater than that of collagen-based hydrogels and also promoted osteogenic differentiation [81]. Likewise, this 3D printing study is useful for improving the mechanical properties of 3D bioprinted constructs.

3.3. Functional properties and outcome

Native bone tissue has an elastic modulus between 10.4–20.7 GPa [82]. Moreover cancellous bone has a compressive modulus of 344 ± 2 MPa [83]. Unfortunately, no bioprinting method can currently create structures capable of satisfying these stated mechanical values and provide the rigidity required of bone tissue. This is demonstrated as Kim et al. only achieved a compressive modulus of 209.2 ± 1.3 kPa in addition to Demirtas et al. achieving an elastic modulus of 15 kPa [73, 76]. Although bioprinted bone constructs do not currently meet the mechanical properties of native bone, many of the aforementioned studies have demonstrated an improvement in mechanical properties while also maintaining high cell viability and osteogenic differentiation.

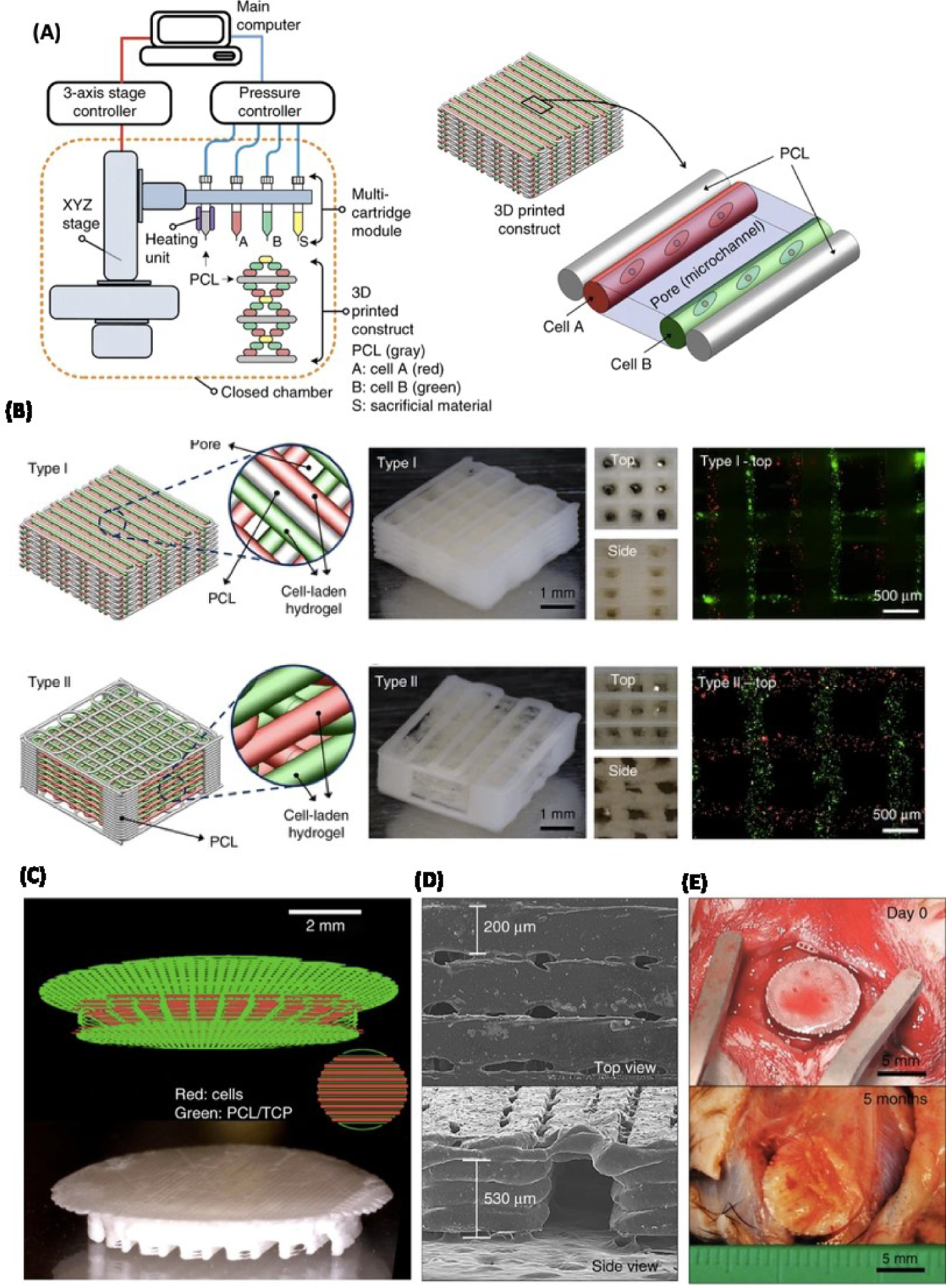

To demonstrate 3D bioprinted bone-like structures in vivo, Kang et al. developed an integrated tissue-organ printer that deposits cell-laden polymer constructs [11]. Kang et al. first bioprinted PCL/TCP with human amniotic fluid-derived stem cells (hAFSCs) discs in a loaded hydrogel composed of gelatin, fibrinogen, HA and glycerol and printed with temporary sacrificial support (Figure 3). These 8 mm diameter and 1.2 mm thick bioprinted discs were then implanted into calvarial bone defects in rats. Five months after implantation, the implantation site was analyzed, and the 3D bioprinted constructs showed widespread newly formed vascularized bone tissue to the center of the implanted scaffold. However, the untreated defects and scaffold-only control exhibited little bone tissue formation [11]. This in vivo study is significant as it demonstrates a 3D bioprinting technology that solves the issue of vascularization and is ultimately able to create new bone tissue that is viable over an extended time frame.

Figure 3. Integrated tissue-organ printer (ITOP) for bone construct:

A) Schematic illustration of ITOP system and patterning of 3D structure consisting of multiple cell-laden hydrogels and PCL polymer. B) Three different images and visualizations of the two types of constructs created. Moving from left to right: a computer visualization of the printed construct, images taken of the printed construct from varying perspectives, and a fluorescent image (3T3’s were labeled with a red and green dye respectively). C) Computer visualization of printing pattern for 3D printing a calvarial bone construct (top). Image of printed calvarial bone construct (bottom). D) Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) image of calvarial bone construct. E) Image of calvarial printed construct day 0 (top) and five months after implantation (bottom). Reproduced from Kang et al. [11] with permission from Nature Publishing Group.

Regardless of advanced developments on tissue construct scaffolds, vascularization remains one of the biggest challenges in bone tissue engineering [17, 18]. In natural tissues, cell viability greatly depends on vascular networks delivering oxygen and nutrients as well as removing metabolic byproducts. In the case of 3D bioprinted tissue constructs that do not contain vascular networks, their thickness may not exceed 1 mm due to diffusional limitations [84]. In an attempt to improve transplant tissue integration and increase cellular viability, vascularized heterogeneous tissue constructs have recently been developed using endothelial cells and fibroblasts [7]. Li et al. demonstrated the importance of a co-culture system of endothelial and osteogenic cells for osteogenic study where endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and MSCs were co-cultured in Matrigel. The study found EPCs and MSCs enhance each other as EPCs increased the rate of MSCs osteogenic differentiation, while MSCs supported EPC proliferation and creation of vascular networks [85]. Furthermore, several vascularized bone-like tissue constructs utilizing co-culture of ECs and hMSCs have been engineered using extrusion-based bioprinting technology in GelMA hydrogel [8, 9]. For instance, to combine bone and vascular tissues in one construct, Byambaa et al. bioprinted a cell-laden GelMA fiber construct that contained various nanocomposites with gradient growth factors (i.e. silicate nanoplatelets for osteogenesis and conjugated VEGF for angiogenesis) [10]. The 3D bioprinted constructs were stable for 21 days in vitro culture and developed perfusable vascular channels within the printed construct, which eventually formed a lumen structure within seven days in static culture. The medium perfusion through this hollow vessel within the bioprinted construct significantly improved mineralization of the bone-like matrix and promoted formation as well as maturation of the tissue construct.

Even after successfully creating vascularized constructs, engineered vasculature must be integrated into the native vasculature at the transplant site (anastomosis). Achieving anastomosis to native bone vasculature will be an important progression for successful transplantation and integration of bioprinted bone tissues into injury sites. A bone recapitulation study by Tang et al. discusses the importance and necessity of gradual weight loading for bone tissue for the development and maturation of the tissue in a healthy manner. This is because the synthesis of mineralized ECM mainly depends on the load size that is applied to the developing tissue [14]. Thus, additional in vivo studies are expected to develop methods for investigating ways to gradually load developing 3D bioprinted bone constructs and to integrate tissue vasculature into host vasculature. These developments will be essential for integrating implanted bioprinted bone tissue to injury sites [12, 14].

4. Cartilage

4.1. Background

Cartilage is found throughout the body and carries out varying functions depending on the specialization of the given cartilage tissue. Cartilage is primarily composed of chondrocytes, a specialized cell type that secrete ECM proteins, and collagen. Cartilage can be classified as either hyaline, elastic, or fibrocartilage. Cartilage injuries are typically caused by lesions to the cartilage tissue and rarely heal independent of surgical intervention due to the avascular nature of cartilage [86, 87]. Similar to other musculoskeletal tissue types, cartilage lesions and subsequently injuries result due to age, trauma, athletic injuries, and degenerative joint diseases [87–89]. Cartilage injuries are a pervasive issue with a large market for repair techniques, as 27 million Americans experience cartilage disrupting injuries of some sort [88].

Unfortunately, current surgical techniques achieve limited success. This limited surgical success is problematic as cartilage lesions cause both pain and reduced function at the injury site [87]. Current techniques such as autologous chondrocyte implantation and matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation often demonstrate promising results, yet they often encounter complications such as delamination, graft failure, and periosteal hypertrophy [87, 89–91]. To solve these challenges, tissue engineering approaches have long focused on cartilage regeneration as an alternative to available surgical approaches. The most commonly utilized biomaterials for cartilage repair include PLGA, fibrin glue, hydrogel, collagen, tissue membrane, polyglycolide (PGA), and alginate, no one biomaterial is currently accepted as an ideal scaffold for regenerating cartilage [92–97]. Additionally, HA is an important natural material to consider for cartilage biofabrication as it promotes cell migration and viability in addition to causing chondrogenic differentiation of undifferentiated MSCs [86].

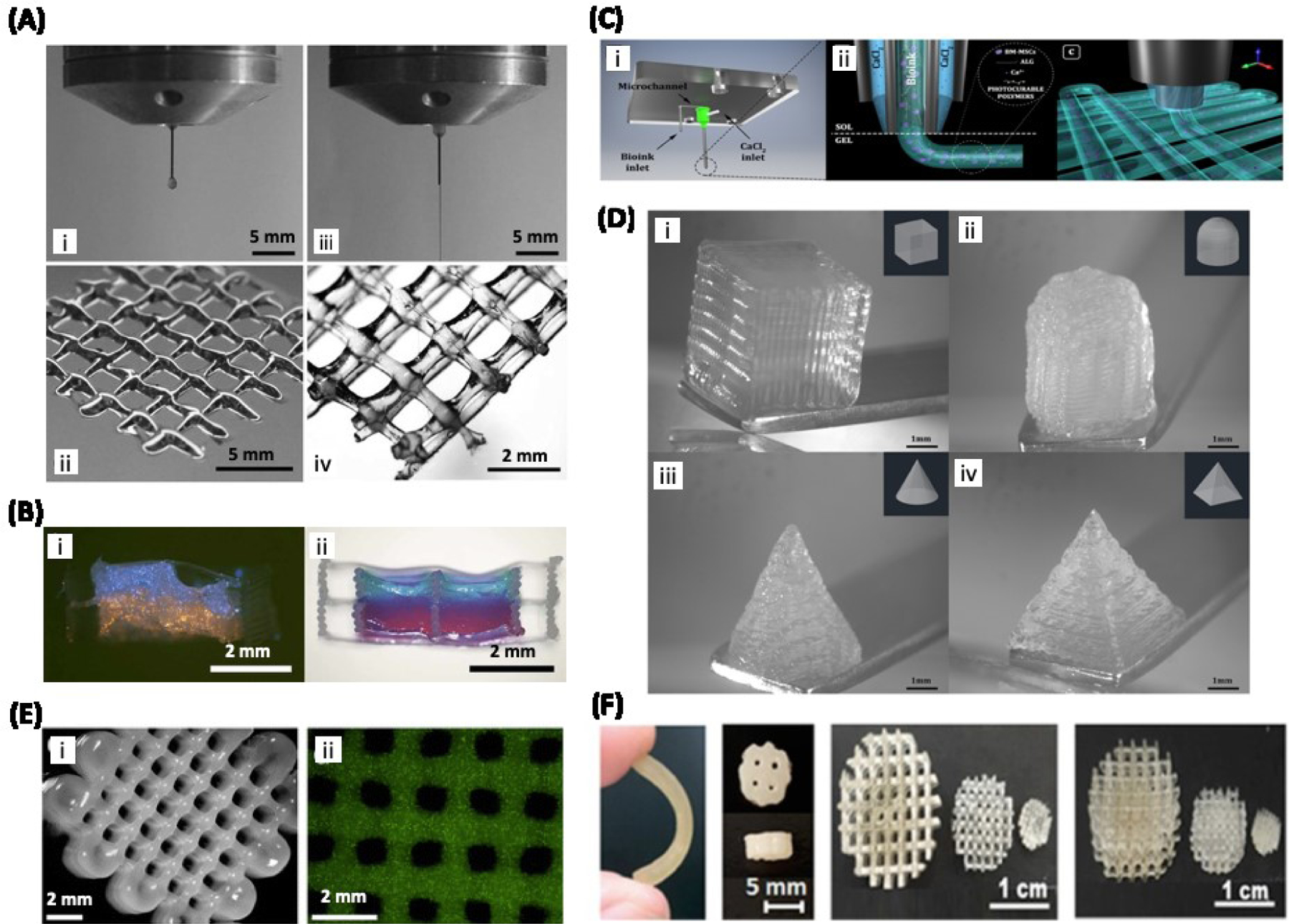

4.2. Cartilage 3D bioprinting

Despite the previously mentioned advantages of using HA as a biomaterial, HA creates relatively unstable bioscaffolds and must be combined with other materials to create a bioink capable of forming structures that can withstand the mechanical strain cartilage undergoes. Pescosolido et al. investigated a bioink that combines HA with a dextran-based semi-interpenetrating network [98]. Ultimately, the 3D bioprinted scaffold demonstrated that the HA dextran-based hydrogels possessed mechanical properties similar to natural tissue in their ability to handle shear and compressive stresses while also being biocompatible as high cell viability was observed for up to three days in vitro [98]. Abbadessa et al. took a different approach to improving the mechanical strength of HA scaffolds and worked to develop a synthetic hydrogel possessing thermosensitive characteristics and consisting of a base triblock methacrylated polyHPMA-lac-PEG copolymer while also exploring the potential of methacrylated hyaluronic acid (HAMA) as a potential material to increase mechanical strength (Figure 4E) [99]. Their study revealed that the addition of HAMA and methacrylated chondroitin sulfate (CSMA) helped to slightly improve mechanical stability (Young’s modulus of unaltered hydrogel 13.7 ± 1.1, compared to 16.0 ± 1.4 and 16.0 ± 1.9 kPa for CSMA and HAMA supplement hydrogels). Moreover, the addition of HAMA and CSMA also helped to drastically decrease the rate of the hydrogel degradation in comparison to the unaltered hydrogel. Beyond mechanical properties advancements, Abbadessa’s synthetic hydrogel also demonstrated promise in proliferation of chondrogenic cells in vitro as cell viabilities remained between 85 and 90 percent seven days after printing.

Figure 4.

3D bioprinting of cartilage: A) Bioprinting of chondrocyte-laden GelMA with (iii and iv) or without (i ad ii) HA. Addition of HA resulted in the continuous flow of bioink that allowed for the printing of a multi-layered structure (iv). B) Hybrid bioprinting of GelMA/HA resulted in the formation of two distinct phases of hydrogels labeled in blue and orange. Adapted from Schuurman et al. [100] with permission from Wiley-VCH. C) Schematic illustration of a coaxial printhead screwed to the 3D-Bioplotter. D) Optical images of MSC-loaded Alginate/GelMA/CS-AEMA/HAMA composite hydrogels printed using the coaxial system. Adapted from Costantini et al. [101] with permission from IOP Publishing. E) 3D printed structures based on chondrocyte-laden methacrylated polyHPMA-lac-PEG and HAMA hydrogels. Adapted from Abbadessa et al. [99] with permission from American Chemical Society. F) Images showing articular cartilage scaffolds based on MSC-loaded photosensitive PU and HAp printed using DLP technique. Reproduced from Shie et al. [86], with permission from MDPI.

Another study, conducted by Schuurman et al., determined that a bioink composition of 20% GelMA and 2.4% HA was required to maintain ideal viscosity to print well defined hydrogel constructs (i.e. GelMA and HA) (Figure 4A and B) [100]. Although this composition is achievable, a high concentration of GelMA creates an environment that is detrimental for chondrocytes to form new ECM and subsequently creates a microenvironment not conducive to forming healthy cartilage as new ECM must be formed to generate healthy cartilage [100, 102]. To address this issue, Schuurman et al. utilized the thermoplastic material PCL to provide mechanical support so that the bioink could be composed of 10% GelMA, as opposed to 20% GelMA, while still possessing the mechanical rigidity required of cartilage. Furthermore, the 10% GelMA and HA bioink maintained high cell viability. Most importantly, the bioscaffold possessed collagen type II and glycosaminoglycans, both markers of cartilage tissue, ultimately demonstrating the printed tissue’s differentiation into cartilage and exhibition of a cartilage phenotype [100]. Costantini et al., investigated the use of a bioink combining ECM derived materials, alginate, and MSCs (derived from bone marrow) in conjunction with a novel articular cartilage bioprinting technique (Figure 4C and D) [101]. These ECM derived biomaterials included GelMA, chondroitin sulphate amino ethyl methacrylate (CS-AEMA), and HAMA. Costantini’s research ultimately determined that the bioink composed of alginate, GelMA, and CS-AEMA most successfully promoted neocartilage formation, making it the most advantageous bioink composition for articular cartilage bioprinting. Moreover, the research also determined that including HAMA in the bioink caused the MSCs to differentiate into hypertrophic cartilage rather than articular cartilage. Likewise, this research is noteworthy as the bone marrow derived MSCs Costantini et al. used are much easier to obtain than chondrocytes [101].

The aforementioned hybrid bioink techniques are unique because they solve issues experienced in bioprinting by combining multiple strategies. Although these individual techniques and approaches are not individually novel and have in some aspects failed in forming functional cartilage tissue, the combination of hybrid technologies presents novel techniques capable of forming healthy cartilage. Thus, these studies are noteworthy as the investigators were able to repurpose and refine existing technologies previously unsuited for cartilage bioprinting to ultimately create new hybrid printing methods for successfully bioprinting cartilage tissues.

4.3. Functional properties and outcome

As discussed in section 4.2, there have been some attempts to improve the mechanical properties of biomaterials used for cartilage bioprinting; however, the mechanical properties obtained in these studies are still far from those for native cartilage tissue. Native articular cartilage has been reported to have a Young’s modulus, compressive modulus, and compressive strength in the range of ~5–25 MPa, 0.24–0.85 MPa, and 20–40 MPa, respectively [104, 105]. Reported values for 3D bioprinted cartilage are far lower with a Young’s modulus of 48 kPa [99] and a compressive modulus of 160 kPa [98]. Biomaterials that are mechanically strong are generally unable to support 3D cell growth and proliferation for bioprinting applications. Shie et al. developed a water based technique for 3D printing hybrid scaffolds based on photosensitive polyurethane (PU) and hydroxyapatite (HAp) (Figure 4F) [86]. Although the hybrid bioink provided the robust mechanical strength required of cartilage, the high temperature involved in the preparation of printing did not allow for cell encapsulation, and the cells were only seeded on the engineered constructs after they were printed.

Despite numerous studies that have advanced aspects of cartilage bioprinting, there have been very few in vivo trials. One such in vivo trial, conducted by Apelgren et al., involved testing the integration and proliferation of bioprinted cartilage constructs into the implantation site [103]. They first 3D bioprinted scaffolds (using an extrusion bioprinter) that were 5×5×1.2 millimeters respectively and composed of nanofibrillated cellulose, alginate, human MSCs (hMSCs), and human nasal chondrocytes (hNC). From the study, they determined that chondrocyte proliferation occurred in the scaffolds and concluded that a co-culture method of hMSCs and chondrocytes was most advantageous for chondrocyte proliferation. Despite the success of demonstrating in vivo chondrocyte proliferation, additional research must still be conducted to study the mechanical strength of the scaffold and the long term effects of scaffold implantation beyond the sixty day observation time frame in this study [103].

5. Muscle

5.1. Background

There are three distinct types of muscle tissue in the body: skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle. This section will focus on skeletal muscle as it plays a primary role in maintaining the structure and movement of the body. Skeletal muscle is responsible for locomotion and forms the musculoskeletal frame that protects internal organs from external damage. Trauma and/or tumor ablation can result in muscle damage and compromise the function of the musculoskeletal system [106–108]. Following severe muscle damage in the upper or lower limbs, surgery is often required to restore function (e.g. musculo-tendinous transfer) [106–108]. This procedure causes morbidity at the harvest site and often leads to suboptimal results [109, 110]. There is an increasing need to supply meaningful volumes of biocompatible muscle tissue that mimic the structure and function of the native counterpart for the treatment of muscle injuries occurring due to sports, aging, and disease like myosarcoma or degenerative muscle diseases. Volumetric muscle loss (VML) is a significant orthopedic problem due to traumatic or surgical loss of skeletal muscle which results in functional impairment [111]. Treatment options for VML are free muscle transfers, which show limited efficacy. Bioengineering options combined with bio- and 3D-printing could help in engineering functional tissue for VML [112]. Thus, creating a highly vascularized and innervated artificial muscle, much like the natural counterpart, is a major challenge. 3D bioprinting has the potential to close the gap between the clinical need and the supply of anatomically and physiologically relevant muscle tissue [113].

5.2. Muscle 3D bioprinting

Materials like PEG, collagen, HA, gelatin, alginate, fibrin and PCL have been proposed suitable for muscle bioprinting [114]. Recently, research has focused on using biological or synthetic materials along with bioprinting technologies to engineer muscle-like microenvironments [34]. In this section we highlight the materials used in 3D bioprinting and 3D printing to create muscle microenvironments and muscle-like constructs. Phillippi et al. created a bioprinter to extrude recombinant human BMP-2 bioink labeled with cyanine 3 (Cy3) to induce differentiation of mouse-derived stem cells (MDSC) into myoblasts [38]. Additionally, Choi et al. [115] used a bioink based on decellularized skeletal muscle ECM to create skeletal muscle, and Costantini et al. [30] used an aligned PEG-fibrinogen bioink to promote muscle precursor cells (C2C12) to merge and form multinucleated myotubes.

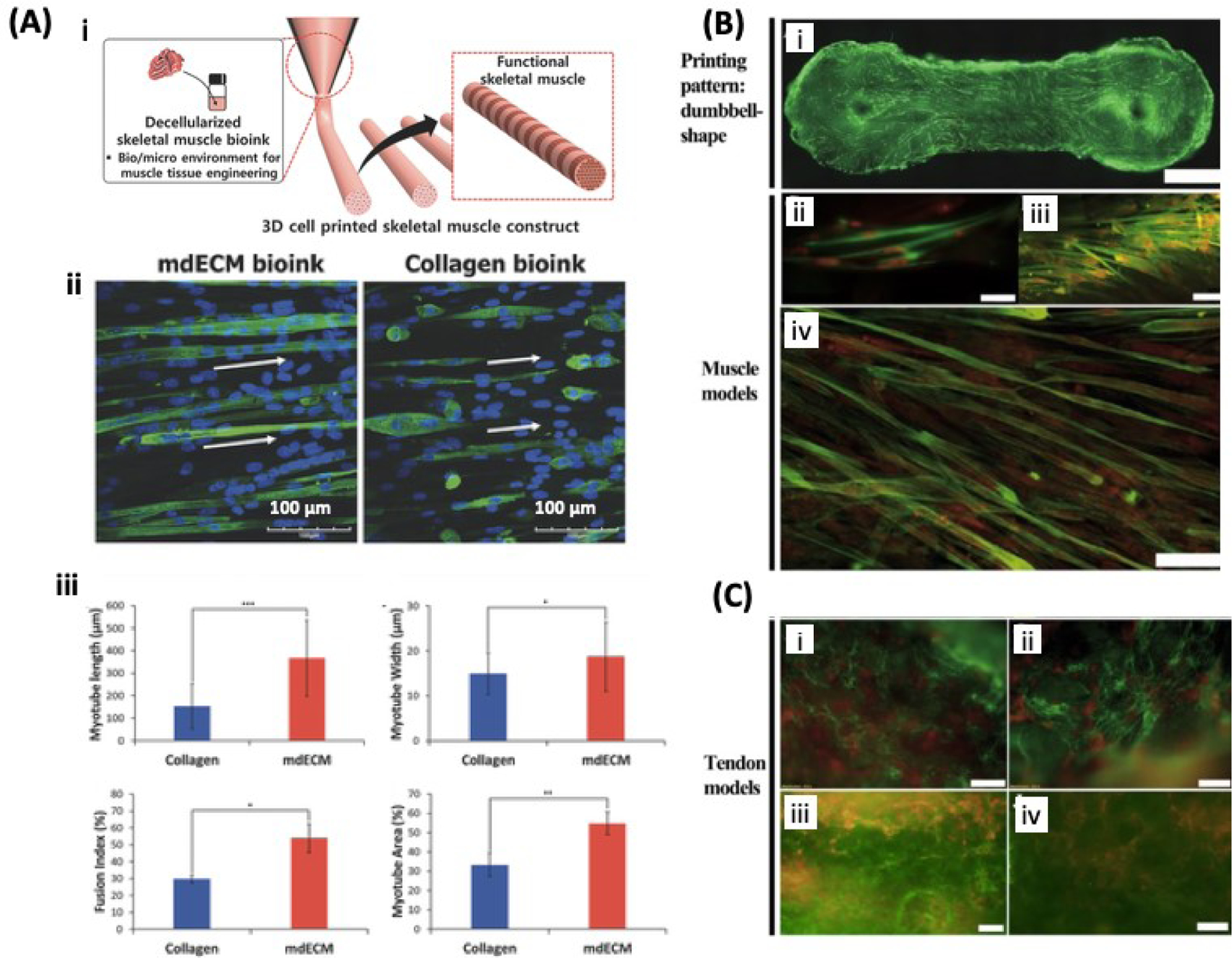

Three-dimensional bioprinting of muscle tissue has a unique advantage over other biofabrication techniques as this technique possesses the ability to control fiber alignment and orientation to produce highly ordered bioscaffolds. Skeletal muscle is an anisotropic material that allows unidirectional force transduction along the long axis of the fiber during contraction and relaxation. With this design parameter in mind, Choi et al. created functional skeletal muscle fibrils using decellularized skeletal muscle ECM (mdECM) as a bioink and a 3D cell-printing system with six printing heads to extrude six different biomaterials [115]. This bioprinting technique created constructs having excellent myoblast viability of up to 14 days in culture with highly aligned cytoskeleton orientation along the fibrils and the presence of myotubules in the muscle constructs (Figure 5). García-Lizarribar et al. utilized extrusion bioprinting through a 200-μm nozzle to create muscle-like fibrils using modified GelMA as a bioink for engineering skeletal muscle tissue [116]. Three photocrosslinkable composite materials (GelMA-alginate-methacrylate [GelMAAlgMA], GelMA-carboxymethyl cellulose-methacrylate [GelMACMCMA], and GelMA-PEGDA) were fabricated as reinforced GelMA fibrils and tested for murine myoblast biocompatibility, myoblast alignment, and myotube formation. The authors reported that GelMA-CMCMA and GelMA-AlgMA bioinks were more durable structures than GelMA alone to create stable and well-aligned muscle-like fibers. Another recent study on 3D skeletal muscle printing by Laternser et al. tested two bioinks, GelMA-PEGDMA-based ink (with 5% GelMA and 5% PEGDMA) and pure GelMA with 5% GelMA w/v [116]. The bioinks were extruded to obtain a 300-μm resolution and printed between polystyrene post to form dumbbell-shaped constructs. Primary human skeletal-muscle-derived cells (SkMDCs) were seeded on top of the constructs and cultured for 22 days. The authors showed evidence of myotube formation after 14 days of culture, and increased expression of myotube-specific genes like myogenin, and structural muscle genes like myosin heavy chain (MYH2) and α-actin 2 (ACTN2). Additionally, these muscle-like constructs showed Ca2+-dependent response upon electrical pulse stimulation of 1 ms, and early formation of myotubes (7 days) when myocytes and tenocytes were co-cultured [117].

Figure 5. Bioprinting of muscle and tendon:

A) Schematic showing the 3D printing of muscle construct using myoblast-laden mdECM bioink (i). Immunofluorescent images of 3D printed myotubes, MHC is stained in green and the nuclei are stained in blue. The white arrows indicate alignment of muscle fibers (ii). Morphometric analysis of myotubes including, length, myotube width, fusion index, and myotube area (iii). Adapted from Choi et al. [115] with permission from Wiley-VCH. B) 3D printed muscle model based on GelMA/PEGDMA hydrogel loaded with SkMDCs. MHC staining confirms the myogenic activity of SkMDCs cultured for 9 days. MHC is stained in green and the cell nuclei in red. C) Tendon model based on tenocyte-laden GelMA/PEGDMA hydrogel stained for collagen type I (I and ii) or III (iii and iv) on day 9 of culture. Collagen type I and III are stained in green and cell nuclei in red. Reproduced from Laternser et al. [117] with permission from Society for Laboratory Automation and Screening.

5.3. Functional properties and outcome

Native skeletal muscle has an elastic modulus and shear modulus between 5–170 kPa [82]. Important design requirements of 3D bioprinted functional muscle dictate that the bioprinted tissue must respond to neurotransmitters and electrical stimulation. Choi et al. showed evidence of acetylcholine receptors (AChR) in the muscle, indicating the potential of the mdECM bioink-printed muscle construct to respond to neurotransmitters [115]. The mdECM construct showed an ultimate strain of 15% and ultimate stress of 4 kPa after 7 days of culture, and ultimate stress of 3.5 kPa and ultimate elastic modulus of 12 kPa after 14 days of in vitro culture. Kang et al. also created a functional 15 mm × 5 mm × 1 mm skeletal muscle constructs by 3D bioprinting cell-laden biodegradable polymeric hydrogels (GelMA-polyethyleneglycol, dimethacrylate, (GelMA-PEGDMA)-based ink, or GelMA) in an integrated fashion which were then anchored to sacrificial hydrogels [11]. This bioprinted construct exhibited AchR and was innervated two weeks after subcutaneous implantation in a mouse model. The 3D bioprinted skeletal muscle was fabricated using an integrated tissue-organ printer (ITOP) to obtain a PCL scaffold encapsulated in a gelatin-fibrinogen hydrogel. This 3D bioprinted skeletal muscle was vascularized after two weeks of subcutaneous implantation and the presence of neovascularization was confirmed by vWF immunostaining. Additionally, this muscle-like tissue was able to respond to in vivo electrical stimulation to evoke a muscle action potential of 3.6 mV. This was compared to the control muscle potential of 10.7 mV of the gastrocnemius muscle [11]. More in vivo studies must be conducted to continue to advance muscle bioprinting and to improve the efficacy of technologies designed for repairing damaged muscle tissue.

6. Tendon

6.1. Background

Although minor tendon fiber ruptures have the ability to repair themselves, greater damage requires surgery to implant autografts and allografts [3, 6]. Even after repair with autologous or donor tissue, the tendon is often weak and can easily rupture again; in many cases, patients require revision surgery to repair the defects [118, 119]. Advances in regenerative therapeutics have yielded an array of techniques, biomaterials, and cell therapies to replace the use of tendon autografts and allografts and reduce the occurrence of surgical complications [120–122]. Despite significant advances, the fabrication of reliable tendons with mechanical properties similar to that of native tissue has yet to be achieved [123]. Here, we review the contributions of bioprinting and 3D printing to the development of robust, mechanically tough tendons for orthopedic surgery.

Tendon is the collagenous tissue that connects skeletal muscle and bone in the body. It requires high tensile strength as it is responsible for the transfer of mechanical forces from contracting and relaxing skeletal muscles to bones [123]. Tendon is an anisotropic structure and it derives its properties from the unidirectional orientation of its constituent fibril-forming collagen type I molecule [124, 125]. Creating a tissue possessing the high mechanical strength required for proper in vivo performance remains the primary challenge in engineering tendon.

The current gold standard for the treatment of tendon injuries is the implantation of tendon autografts to replace and repair the damaged tissue [5, 126–129]. Despite having similar biological function, tendons differ from other connective tissue types in their mechanical properties and metabolic activity. Because of these differences, implantable materials that specifically mimic tendons are needed. 3D bioprinting has the potential to produce these tissues due to its excellent in vivo biocompatibility, cell cytoskeleton alignment along the long axis of the tendon graft, upregulation of tendon biomarkers in cells seeded on the graft, and mechanical properties to match those of the native counterpart.

6.2. Tendon 3D bioprinting

One study, conducted by Laternser et al., involved 3D printing dumbbell-shaped GelMA structures and subsequently seeding the constructs with primary rat tail tenocytes [117]. After 14 days in culture, the cells showed increased expression of tenomodulin, a tendon-specific gene. Despite the favorable gene expression, the tenocytes failed to show the required uniaxial cytoskeletal orientation along the long axis of the 3D printed construct. Additionally, some studies have used synthetic polymers, such as PCL and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), to enhance the material properties [130]. PCL can be used to fabricate a biocompatible tendon scaffold using electrohydrodynamic jet printing (E-jetting). Human tenocytes were seeded on the PCL tendon scaffold and after seven days of culture, results showed high viability and cytoskeletal alignment along the long axis of the scaffold. Despite the favorable cell properties, the mechanical properties of the scaffold were far too weak compared to native human tendons, making them unsuitable for pre-clinical evaluation [130]. In another study, Mozdzen et al. developed a composite tendon construct using 3D printed ABS fibers embedded in a collagen-glycosaminoglycan sponge [131]. The product was a composite structure with a core of mechanically resilient ABS fibers, and a shell of bioactive collagen. ABS fibers were functionalized with bovine serum albumin and platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) to further enhance tissue maturation [131]. Similar to the PCL-based material, the major drawback of this platform was its weak mechanical properties compared to native tendon; the mechanical insufficiencies ultimately hindered its application in tendon injury animal models [132].

All previously mentioned studies have been 3D printing studies in which scaffolds were printed then seeded with cells. Alternatively, a recently published 3D bioprinting approach integrated dual printing of a polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) frame with the shape of the rotator cuff tendon and a collagen-fibrin hydrogel encapsulating human adipose-derived MSCs [133]. Mechanical properties showed that this composite construct had an elastic stiffness of 60 N/mm and an ultimate failure force of 17 N. Cells were viable and differentiated into tenocytes when cultured in tendon differentiation medium, with upregulation of scleraxis, tenomodulin, tenascin and collagen type III genes. Despite there being numerous studies investigating tendon 3D printing, there have been few tendon 3D bioprinting studies [133, 134]. Additional research must be conducted in tendon 3D bioprinting that leverages the advances of the mentioned 3D printing studies. Moreover, this tendon bioprinting section did not include a subsection devoted to functional properties and outcome. This can be attributed to tendon 3D bioprinting being less developed compared to bone or cartilage bioprinting.

7. Ligament

7.1. Background

Ligaments are specialized tissue that are defined as dense fibers of connective tissue that span a joint and attach to the bone on either end [135]. They are composed of fibroblasts responsible for the composition and repair of the ECM [135]. People of all ages and activity levels can suffer ligamentous injuries extending from athletes to the elderly. These injuries can cause joint instability and are accompanied by pain, disability, and the progression of degenerative diseases. Ligamentous injuries can be broadly classified as sprains (no joint laxity), partial ruptures (moderate joint laxity) and complete ruptures [136]. Following injury, viscoelastic properties of the healed ligament do not fully recover and the ligament is less efficient in maintaining loads compared to normal uninjured ligament [137]. In addition, scarred ligaments are less stiff, absorb less energy and are weaker than normal ligament [138, 139]. Often they heel in laxity causing impingement and preventing normal movement of the joint [140, 141].

The available reconstruction strategies vary significantly between different ligaments in the body. Such interventions include the direct repair of ligaments or their reconstruction with grafts. These grafts can be autologous (tendons or ligaments), allografts or synthetic materials (like artificial ligaments, meshes, suture tapes and others) [142–146]. These options demonstrate good patient outcomes but have been associated with donor site morbidity, graft rejection, joint stiffness or laxity, postoperative pain, and poor osteointegration [147, 148]. These limitations have prompted research into tissue engineering of ligaments. Tissue engineering has urged a better expansion of our understanding of ligament healing biology and brought into light several approaches to upregulate the healing of the ligaments with the use of cells, growth factors, or gene therapy [147, 149]. Different ECMs and scaffolds have been tested [147, 149, 150]. More recently, with the development of 3D bioprinting, on demand ligament fabrications have been tested as a viable alternative to the aforementioned options.

7.2. Ligament 3D bioprinting

There are currently very few studies on ligament 3D bioprinting [151–154]. Raveendran et al. optimized 3D bioprinting parameters for reconstruction of the periodontal ligaments [151]. The authors used human primary periodontal ligament cells and GelMA hydrogels and analyzed the effect of adaptations for fabricating homogenous and continuous strands. Such parameters included the printing pressure, nozzle inner diameter, collector speed, polymer concentration, photoinitiator type/concentration, temperature, printing offset and viscosity of the bioink. Although exclusively using GelMA as a printing material for microextrusion often leads to poor printability, Raveendran et al. found that implementing changes to the previously mentioned parameters can enhance the printability without greatly affecting the cytocompatibility of the material [151]. For example, the authors demonstrated that a low concentration of lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate combined with short UV-exposure was not toxic for the cells. Xu et al. in a feasibility study using polycaprolactone and periodontal ligament stem cells showed the ability to successfully print a 3D structure with a self-defined shape, size, and high levels of cell viability [152].

Current literature only offers feasibility data on 3D bioprinting of ligaments and lacks functional outcome results from either in vitro or in vivo studies. Likewise, this ligament section does not include a subsection devoted to functional properties and outcome as ligament 3D bioprinting is not as developed as other musculoskeletal tissues. Additional research must be conducted in ligament bioprinting and in vivo studies.

8. Interfaces of Musculoskeletal Tissues

8.1. Background

A major barrier in the development of bioprinted interfacial musculoskeletal tissue is the need to satisfy microenvironment conditions for multiple cell types and varying or gradient-like mechanical properties [155]. Bioprinting muscle and tendon remains a complicated task and it is still in experimental process. Studies are focusing on finding the best bioink formulation and cellular response to polymers or external stimuli. Due to the forces applied to these tissues, mechanical properties constitute a major concern in engineering musculoskeletal tissues, and it is even more complicated when it comes to engineering their interfaces [38, 156, 157].

8.2. Musculoskeletal tissue interface 3D bioprinting

8.2.1. Osteochondral unit

Osteochondral defects and arthritis are a leading cause of pain and disability in today’s aging population. Although all joints are susceptible to such injuries, large joints such as knee and hip joints are most often affected [158]. Osteochondral defects can occur as the outcome of trauma or wear and tear. Because of the poor regenerative capacity of the body’s osteochondral tissues, the extent of symptoms are variable and influenced by the degree and location of the defect to the cartilage and the subchondral bone [159].

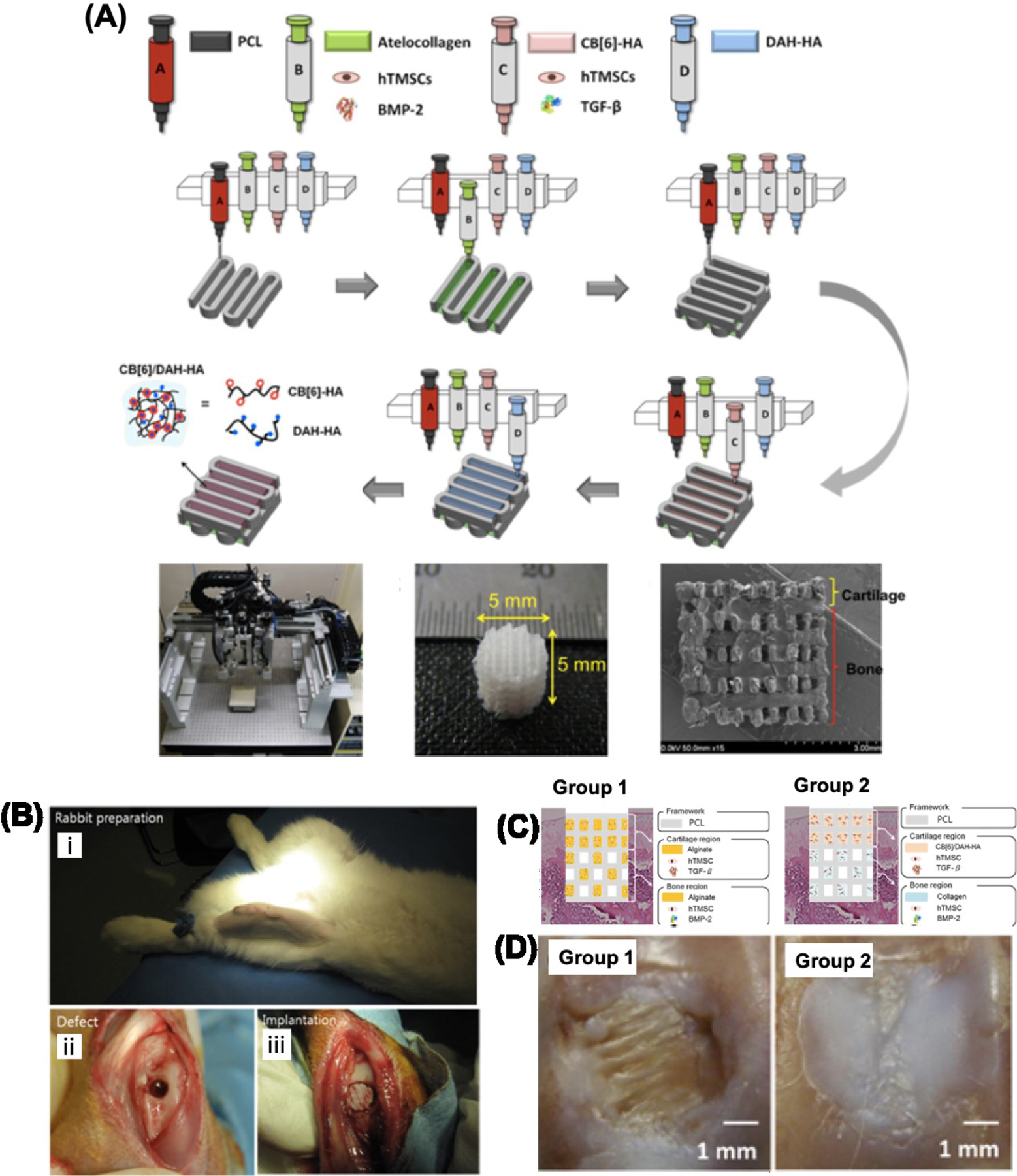

Osteochondral 3D bioprinting is less developed than bone and cartilage bioprinting and subsequently has fewer studies than the respective individual tissues types. In one study, Kilian et al. developed a multi-layered full thickness construct with the use of a bioink composed of primary chondrocytes combined with pasty calcium phosphate cement for bony elements and also a bioink composed of alginate-methylcellulose for the cartilaginous layers [160]. During in vitro testing the authors reported that the majority of encapsulated cells survived the 3D bioprinting process and underwent redifferentiation into their respective bone or cartilage environment in a 3-week period after bioprinting. Another study by Shim et al. tested a fabricated PCL/HA/atelocollagen cell-laden scaffold in vivo in an injured rabbit knee joint (Figure 6) [22]. Their scaffolds also incorporated growth factors (bone morphogenic protein (BMP)-2, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β) in the hydrogel portions of the construct. They first printed the PCL frame and followed with human turbinate-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (hTMSCs) with rhBMP-2 to favor formation of atelocollagen subchondral bone tissue. Next, the HA cartilage layer was printed using hTMSCs and TGF-β. Shim et al. reported that no inflammatory response was initiated and the transplanted construct overall integrated well into the injury site over the eight week in vivo trial [22]. In contrast to that, Gao et al. engineered a highly stiff hydrogel-based scaffold with a gradient structure using extrusion based direct bioprinting technology [161].The gradient structure of this in vivo rat trial provided an excellent environment for osteogenic/chondrogenic differentiation and inducing bone formation and cartilage repair.

Figure 6.

Images from bioprinted osteochondral construct and rabbit in vivo trial. A) Schematic illustration of the multi head tissue/organ building system (MtoBS) used for 3D printing of MSCs loaded ECM/PCL composite hydrogels resulting in the fabrication of multilayered 3D construct for regeneration of osteochondral tissue. B) Image of rabbit prior to simulating osteochondral injury (i), simulated osteochondral defect in rabbit knee joint (ii), and implantation of 3D Bioprinted osteochondral construct (iii). C) Schematic illustration of experimental groups for the in vivo experiment. D) Images showing bone (group 1) and cartilage (group 2) like tissue regeneration in the samples after implantation for 8 weeks. Reproduced from Shim et al. with permission from IOP Publishing.

8.2.2. Muscle bone unit

Bone and muscle are separated by the perimysium and attached on their extremities by tendons. Myoblasts (muscle cells) and osteoblasts cells (bone cells) constantly communicate through the secretion of proteins and both cell types are responsive to different stimuli such as electrical signals, secreted factors, or soluble metabolites [182]. Engineering the bone-muscle interface is a major challenge that has recently gained interest, largely due to the advent of 3D bioprinting and will pose exciting opportunities as an interface tissue.

8.2.3. Muscle tendon unit

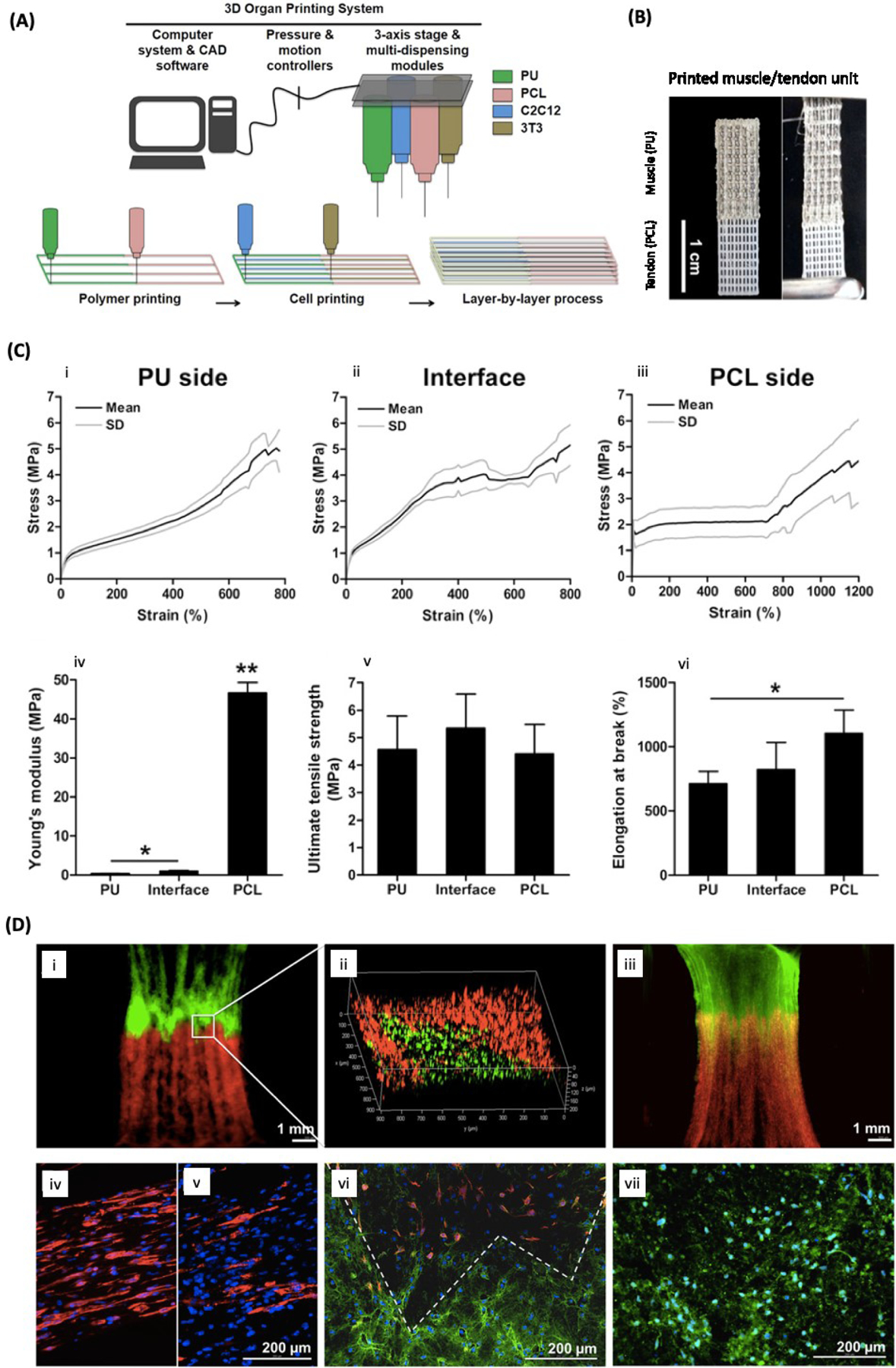

Unfortunately, it is still challenging to create muscle-like constructs using 3D-printing. When creating artificial muscle, the contractile forces need to be transferred to tendon and then to bone in order to maintain movement of the skeletal body frame. With this in mind, Merceron et al. used thermoplastic polyurethane (PU) as the muscle matrix and poly PCL as the tendon matrix, to 3D bioprint a complex muscle-to-tendon interface [23]. The PU layer was co-printed with C2C12 cell-laden hydrogel (HA, gelatin, and fibrinogen in calcium-free high-glucose DMEM). The PCL layer was co-printed with a mouse fibroblast (NIH/3T3) cell-laden hydrogel (composed of same components as other hydrogel). The engineered construct provided a gradient structure with PU, PU/PCL, and PCL sides each showing strain-stress curves characteristic of elastomeric, elastomeric/plastic, and plastic materials, respectively, to mimic the structure of muscle/tendon interface (Figure 7c). Moreover, the bioprinted construct demonstrated high cell viability and cellular differentiation (Figure 7) [23]. In the previous muscle and tendon sections, a study by Laternser et al. was discussed. In addition to working to individually print muscle tissue and tendon tissue, a muscle tendon coculture was bioprinted around a custom post insert for an in vitro trial. With this study, the researchers were able to successfully show the interface of the muscle and tendon into a muscle tendon unit through myosin heavy chain (MHC) staining of the muscle and collagen type I staining of the tendon. Although this model was for in vitro testing of musculoskeletal disease, the model and ability to form a muscle tendon unit is notable as a starting point for in vivo applications [117].

Figure 7. Bioprinting of muscle/tendon interface tissue:

A) Schematic illustration of 3D integrated organ printing (IOP). B) 3D printed muscle/tendon unit using IOP system. C) Tensile properties of the bioprinted muscle/tendon unit. Representative tensile-strain curves (i-iii), Young’s modulus (iv), tensile strength (v), and failure strain (vi). D) Fluorescence images (i-iii) of C2C12 and 3T3 cells labeled with DiO (green) and DiI (red), respectively, on day 7 of culture. Yellow shows the interface between green and red fluorescence. Immunofluorescence staining of 3D printed muscle/tendon units (iv-vii) on the muscle side (iv nd v) showing highly aligned myotubes, at the interface (vi), and on the tendon side (vii) showing the secretion of collagen type I. Desmin (iv, vi) and MHC (v) were stain in red. Collagen type I was stained in green and the cell nuclei in blue. Reproduced from Merceron et al. [23] with permission from IOP publishing.

8.2.4. Tendon bone unit

Park et al. utilized 3D printing to engineer a composite biomaterial to enhance the tendon-bone interface in a rabbit ACL injury models [162]. The composite 3D printed scaffold sleeve consisted of PCL, PLGA, and β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP). PCL and PLGA were incorporated to mimic the soft tendon and hyaline cartilage while β-TCP corresponded to the rigid bone component of the system. The study aimed to implant these constructs to accelerate osteointegration of the ACL to the tibia. MSCs were directly seeded on the 3D printed sleeve and its performance as an ACL graft was evaluated after 12 weeks. Immunohistochemical staining of type II collagen in the implanted grafts showed increased deposition of neocartilage in MSC-laden bioprinted sleeves when compared to cell-free sleeves. Additionally, the 3D printed sleeves showed improved osteointegration between tendon and bone in the ACL reconstruction model [162].

8.3. Functional properties and outcome

There are far fewer cited studies and information regarding 3D bioprinted musculoskeletal interface tissues compared to other sections of this paper. This can largely be explained as there are numerous challenges mentioned earlier such as creating a tissue construct capable of successfully imitating microenvironment conditions for multiple cell types while also being able to withstand varying mechanical demands [155]. Moreover, there exist developed methods for characterizing varying mechanical properties over a spatial gradient such as an interface tissue [163–165]. These characterization methods are crucial for ensuring that 3D bioprinted tissues satisfy the variable mechanical properties required of musculoskeletal interface tissues. Although it may be more prudent to first engineer working bone, muscle, or cartilage tissues rather than interface tissues, there still exists an exciting opportunity in engineering musculoskeletal interfaces to ultimately create tissues that more accurately reflect the complexity of native tissues.

10. Challenges and future perspectives

Despite numerous developments in the 3D bioprinting of musculoskeletal tissues, there still exist significant challenges and ongoing limitations that ultimately handicap the success of printed constructs in vivo and also in their translation to applicable models [120]. One such challenge includes the improvement of biomaterials for their use in bioprinting. In bioinks composed of naturally derived materials, the variability and inconsistencies between printed samples has limited their efficacy. Additionally, natural polymer materials do not possess the mechanical strength required to mimic the in vivo environment of native musculoskeletal tissues [19]. However, by combining stronger biocompatible materials, such as PLGA, PLA, and PCL with natural inks, this issue can be addressed [155, 166].

Another major challenge consists of developing mature tissues with desirable cell phenotypes and intricate vascular structures [17, 18, 167]. Biomaterials inevitably influence the function of cells and it is currently unclear which material is definitively ideal for each type of tissue. It is also unclear which additives and phenotype inducers, for example growth factors or chemokines, are required for the maturation of each type of tissue. Poor vasculature also inhibits the formation of mature tissue by limiting the transport of essential nutrients and waste to and from cells. Several approaches have been explored, including the use of computers to generate vascular trees [18]. However, mechanically stable and integrated vessels have yet to be developed [168]. One of the approaches of producing vascularized tissue is to build vasculature during the bioprinting process [169]. Another approach to forming a vascular system is to use angiogenic factors to facilitate self-assembly, an intricate and slow process requiring immense control. Despite progress in vascularization [170], building a functional vascular network remains a major obstacle in bioprinting [171].

These challenges together compose the paramount problem in musculoskeletal bioprinting as bioprinted constructs face difficulty integrating into native tissues when transplanted. This challenge will require concurrent advances in vascularization, degradation, biocompatibility, and mechanical strength of printed constructs to mimic native architectures. Work has already begun in developing this as evidenced by the number of studies mentioned earlier who have tested and are working with in vivo models of 3D bioprinted constructs [10, 11, 22, 85, 103, 115, 162]. Regardless, as translation is a major goal for 3D bioprinted musculoskeletal constructs, more in vivo research must be undertaken to better understand how to incorporate printed tissues into the native in vivo microenvironment.

In order to ensure the long term success of 3D bioprinting, regulatory concerns, such as the sourcing of cells and suitable/allowed biomaterials will also need to be addressed [172]. Thus far, there are no clear regulations for 3D bioprinting by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in the US FDA or UK [173]. While the technology may not currently be ready for clinical application, the regulatory foundations should be laid in the near future to facilitate a rapid and smooth transition from the laboratory to the clinic.

Moving forward, bioprinting presents an exciting opportunity for engineering and creating individual musculoskeletal tissues and interface structures consisting of multiple tissue types. Indeed, bioprinting’s strengths in precisely controlling material and cell placement make it well suited for the creation of musculoskeletal tissues with homogenous cell distributions [15–17]. This degree of control is especially important for interface tissues in which multiple cell types and materials work together in unison to create a functional tissue. Despite the advantages in material and cell placement, musculoskeletal tissues generated by bioprinting face a dichotomy between using materials conducive to cellular proliferation and creating tissues capable of satisfying the stringent mechanical properties required of musculoskeletal tissues [19, 49, 98, 123, 174]. Likewise, additional research must be conducted in exploring materials and printing techniques capable of providing the robust mechanical strength required of musculoskeletal tissues, while also still creating a microenvironment conducive to cellular proliferation. As previously mentioned, hybrid printing techniques and the repurposing/combination of current printing methods presents an intriguing opportunity for musculoskeletal 3D bioprinting development. Studies employing this technique have been relatively successful [86, 98, 100, 175], and subsequently justify future exploration of hybrid printing techniques.

11. Conclusions

Three-dimensional bioprinting holds great promise to facilitate the creation of viable musculoskeletal tissues. Decades of research and advancements in bioprinting have yielded great progress in tissue engineering through the development of new materials, identification of cell sources, and improvement in the manufacturing methods and equipment. In comparison to other tissue engineering approaches, bioprinting offers the ability to precisely pattern multiple biomaterials and cell types to mimic the organization of native tissues. Despite the progress in the field, the primary challenges that have yet to be overcome are the development of suitable materials, incorporation of vasculature and innervation, and maturation of tissue to become functional. Moving forward, it is imperative that we continue to develop a deep understanding of the physiology and biology of the tissues and cellular microenvironments in parallel with the technology to recreate it. Achieving the goal of printing implantable musculoskeletal tissue will require a multidisciplinary collaboration involving chemists, biologists, engineers, clinicians, and policymakers; though great challenges lie ahead, these collaborations will be essential in the translation of musculoskeletal bioprinting from the lab bench to the operating room.

Table 2.

Summary of bone 3D bioprinting and 3D printing studies, in which different types of cells were used such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), osteoblasts (OSB), chondrocytes (CHD), sarcoma osteogenic (Saos-2), osteosarcoma (MG63), mouse osteoblast precursor (MC3T3-E1), human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC), and human amniotic fluid stem cells (hAFSC). Matrix materials used include polycaprolactone (PCL), polyethylene glycol (PEG), poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), extracellular matrix (ECM), poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), hyaluronic acid (HA), gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA). Printing methods used included multi-head tissue/organ building system (MtoBS).

| Study | Printing Method | Material | Cell Type | Mechanical Properties | In vivo/in vitro Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gao et al. [77] | Inkjet | Acrylated peptides, acrylated PEG | MSC | PEG: 60 kPa Compressive Modulus PEG-Peptide: 70 kPa Compressive Modulus (after 21 days in culture differentiated towards osteogenic lineage) | Differentiation to osteogenic lineage, high amounts of calcified mineralized matrix |

| Shim et al. [79] | MtoBS | PCL, alginate | OSB, CHD | Not reported | Developed bone tissue |

| Ojansivu et al. [80] | Extrusion | Wood-derived cellulose nanofibril, alginate, gelatin | Saos-2 | Storage Modulus: 10,000 G’ | N/A |

| Kim et al. [73] | Extrusion | Gelatin, PVA | MG63 | Compressive Modulus: 209.2 ± 1.3 kPa (for gelatin/PVA 5:5)), did not meet target compressive modulus of 344 ± 2 MPa for cancellous bone | Gelatin/PVA (5:5) high cell proliferation and differentiation |

| Lee et al. [74] | Extrusion | Collagen, decellularized ECM, silk-fibroin | MC3T3-E1 | Compressive Modulus: 0.3 ± .004 MPa | Favorable environment for differentiation to osteoblasts |

| Zhai et al. [75] | Extrusion (Two channel) | PEGDA, HA, Nanoclay/nanocomposite | SaOS‐2 | Compressive Modulus: 0.096 MPa (20%PEG4K) Compressive Modulus: 0.332 MPa (20%PEG10K) | High cell viability, expression of osteogenic phenotype, create microenvironment conducive to bone repair |

| Demirtas et al. [76] | Extrusion | Chitosan/HA | MC3T3-E1 | Elastic Modulus: 15 kPa (significantly softer than cancellous bone) | Differentiation to osteogenic phenotype |

| Byambaa et al. [10] | Extrusion-base Direct-write | Silicate nanoplatelets, 5% GelMA | HUVEC, MSC | Compressive Modulus: 5.7 kPa | Stability for 21 days in vitro culture, osteogenesis and angiogenesis occurred |

| Kang et al. [11] | Integrated tissue-organ printer | PCL/tricalciu m phosphate, gelatin, fibrinogen, HA, and glycerol | hAFSC | Not Reported | Newly formed vascularized bone tissue at the implantation site |

Table 3.

Summary of cartilage 3D bioprinting and 3D printing studies, in which different cells such as human Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells (hWJMSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), chondrocytes (CHD), and human nasal chondrocytes (hNC). Matrix materials used include hydroxyethyl-methacrylate-derivatized dextran (dex-HEMA), polycaprolactone (PCL), polyethylene glycol (PEG), poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), hyaluronic acid (HA), gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), poly[N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide mono/dilactate] (polyHPMA), chondroitin sulphate amino ethyl methacrylate (CS-AEMA), HA methacrylate (HAMA), methacrylated chondroitin sulfate (CSMA), photosensitive polyurethane (PU), and hydroxyapatite (HAp).

| Study | Printing Method | Material | Cell Type | Mechanical properties | In vivo/in vitro outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pescosolido et al. [98] |

Extrusion | HA, dex-HEMA | CHD | G’ ≈ 10 kPa E ≈ 26 kPa Compressive Modulus: 100–160 kPa depending on HA content |

High cell viability after 3 days in vitro |

| Schuurman et al. [100] | Extrusion | GelMA, HA, PCL | CHD | Compressive Modulus: 36 kPa (10% GelMA), 199 kPa (20% GelMA) | Scaffold possessed cartilage markers (collagen type II and glycosaminoglycans), high cell viability in 10% GelMA and HA bioink |

| Costantini et al. [101] | Extrusion | GelMA, CS-AEMA, HAMA, alginate | MSCs | Compressive Modulus: 59.7 ± 5.4 kPA | Alginate, GelMA, and CS-AEMA bioink led to neocartilage formation |

| Shie et al. [86] | DLP (scaffold 3D printed then seeded with cells) | PU, HAp | hWJMSCs | Young’s Modulus: ~40 MPa (meets mechanical requirements of cartilage) | High biocompatibility and differentiation to chondrogenic phenotype |

| Abbadessa et al. [99] | Extrusion | methacrylated polyHPMA-lac-PEG, HAMA, CSMA | CHD | Young’s modulus: 16.0 kPA | Chondrocytes proliferated in vitro and had high viabilities over seven days in culture, high cartilage production occured |

| Apelgren et al. [103] | Extrusion | Nanofibrillated cellulose, alginate | MSCs, hNC | Not reported | Co-culture of MSCs and chondrocytes advantageous for chondrocyte proliferation |

Table 4.

Summary of muscle 3D bioprinting and 3D printing studies, in which different types of cells were used such as immortalized mouse myoblast (C2C12) and primary human skeletal-muscle-derived cells (SkMDCs). Matrix materials used include extracellular matrix (ECM), polycaprolactone (PCL), polyethylene glycol (PEG), poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), hyaluronic acid (HA), gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA). Printing methods used included integrated organ printer (ITOP).

| Study | Printing Method | Material | Cell Type | Mechanical properties | In vivo/in vitro outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi et al. [115] | Integrated Composite tissue/organ building system | Decellularized muscle ECM | C2C12 | Elastic Modulus: 12 ± 3 kPa | Formed functional and aligned skeletal muscle in vitro |

| Costantini et al. [30] | Extrusion (microfluidic) | PEG-fibrinogen | C2C12 | Young’s Modulus: 48 kPa | Myoblasts migrated, fused, and formed multinucleated myotubes; in vivo create organized muscle |