Abstract

Introduction:

Major trauma is the leading cause of mortality in the world in patients younger than 40 years. However, the proportion of elderly people who suffer trauma has increased significantly. The purpose of this study is to assess the correlation of old age with mortality and other unfavorable outcomes.

Methods:

We assessed on one hand, anatomical criteria such as ISS values and the number of body regions affected, on the other hand, hemodynamic instability criteria, various shock indices, and Glasgow Coma Scale. Finally, we also evaluated biochemical parameters, such as lactate, BE, and pH values. We conducted a prospective and monocentric observational study of all the patients referred to the Emergency Department of the IRCCS Fondazione Policlinico S. Matteo in Pavia for major trauma in 13 consecutive months: January 1, 2018–January 30, 2019. We compared the elderly population (>75 years) and the younger population (≤75).

Results:

We included 501 patients, among which 10% were over the age of 75 years. The mortality rate was higher among the older patients than among the younger (4% vs. 1.33%; P = 0.050). Hemodynamic instability was more common in the older patients than in the younger (26% vs. 9%; P < 0.001). More older patients (44%) had an ISS >16, in comparison with 32% of younger patients (P = 0.01).

Conclusions:

The elderly showed worse outcomes in terms of mortality, hospitalization rate, hemodynamic instability criteria, and anatomical and biochemical parameters.

Keywords: Elderly patients, emergency room, major trauma, severe trauma, trauma center

INTRODUCTION

Major trauma is the leading cause of mortality in the world in patients younger than 40 years.[1] However, the proportion of elderly people who suffer trauma has increased significantly.[2] One reason is that older people today lead more active lives and therefore are more exposed to major trauma.[3] The dynamics of injury in older people are slightly less severe than in young people.[4] For this reason, among others, major trauma in elderly people is often unrecognized. Nevertheless, age is a serious risk factor for unfavorable outcomes.[5] The study of severe trauma in this growing population is of great importance today.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted a prospective, single-center, observational study of all patients referred to the Emergency Department of the IRCCS Fondazione Policlinico S. Matteo in Pavia, Italy, for major trauma during 13 consecutive months: January 1, 2018, to January 30, 2019. Our main goal was to determine whether the rates of mortality were worse in the population older than 75 years than in younger patients. We also wanted to determine whether older patients sustained more severe trauma. We assessed anatomical criteria such as Injury Severity Score (ISS) values and the number of body-regions affected, as well as criteria for hemodynamic instability, various shock indices, and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score. We also evaluated biochemical findings such as the values of lactate levels, base excess, and pH. We investigated whether worse outcomes depended in any way on the degree of bleeding or on other reasons related to age.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients referred to our emergency department and included in the hospital's major trauma registry were enrolled. The major trauma registry includes all patients in whom the protocol for major trauma was performed. “Major trauma” referred to an event that resulted in single or multiple injuries of such magnitude that it constitutes a danger to the person's life or health, and “trauma” was defined as severe when the patient's ISS value was >15.[6] ISS can be calculated only after the patient has undergone diagnostic investigations (carried out mainly in the hospital). To overcome this limitation, inasmuch as a potential major trauma must be recognized as soon as possible, and therefore before the patient reaches the hospital, triage criteria for major trauma[7] are used [Table 1].

Table 1.

Triage criteria for activating the severe trauma protocol in our trauma center

| Criteria | Injury |

|---|---|

| Mechanism | Ejection from the vehicle |

| Motorcyclist thrown from the vehicle | |

| Fatality in same vehicle | |

| Intruding of the cabin >30 cm | |

| Fall from height >2 m | |

| Pedestrian projected or rolled or hit at speed >10 km/h | |

| High-energy impact (speed >65 km/h) | |

| Vehicle coat | |

| Extrication time >20 min | |

| Anatomical | Penetrating injury to the head, neck, torso, or proximal limbs |

| Amputations above the wrist or ankle | |

| Chest trauma with flail chest | |

| Neurological injury with paralysis | |

| Fractures of 2 or more long bones | |

| Suspected unstable pelvis fracture | |

| Skull fracture | |

| Burn >20% body surface or involving airway/face | |

| Hemodynamic | Systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg |

| Respiratory or breathlessness rate <10 or>29 acts/min | |

| State of consciousness (GCS) <13 |

GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale

Study population

Eligible patients were identified in the electronic database through diagnosis codes at discharge corresponding to “polytrauma” or codes of acceptance to triage for “major trauma.” This was because in the emergency setting, contextual data collection could have taken time away from care.

For each patient, personal and clinical data were extracted through the PIESSE digital platform and the medical record when drafted. The data were then examined individually to assess whether patients could be included in the study. The electronic folder for each patient contained the data collected and reported by the emergency physician, clinical reports by medical specialists, nursing diaries, and results and reports of laboratory and radiological examinations. Demographics, causes and dynamics of trauma, waiting times, process times, lengths of stay in the emergency department, time needed to perform the various instrumental examinations and reporting topics, vital signs, means of arrival, entry code, exit code, and hematochemical and blood gas measurements for all patients were collected. Hospitalization rate, the need for an operating room, time spent in the intensive care unit, and death rate were also assessed. All test results were viewed and evaluated, and all computed tomographic (CT) findings were thoroughly reviewed. All collected data were stored in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and subsequently used for the statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were calculated as medians and interquartile ranges because they were not normally distributed, and qualitative variables were calculated as numbers and percentages. The two age groups (patients aged 75 years and older and those younger than 75 years) were compared in a Mann–Whitney nonparametric test. Associations between qualitative variables were evaluated with the Fisher's exact test. To determine the correlation between the continuous variables of interest, the Rho co-efficient for Spearman ranks was calculated. All tests used are two tailed, with the level of significance for statistical tests at <0.05.

RESULTS

Study population

A total of 503 patients were seen in the emergency department for major trauma throughout 2018.

Patients with major trauma aged 75 years or older

This group included 51 patients (10% of the total): 18/51 (35%) women and 33/51 (65%) men. Among these patients, trauma was diagnosed according to the mechanism criteria in 89.8%, anatomical criteria in 18.4%, and hemodynamic criteria in 26.5%.

In this subpopulation, the average heart rate was 83 bpm; 8% of patients had a high heart rate (>110 bpm). The average systolic blood pressure was 139 mm Hg; 6% had systolic pressures of <90 mm Hg. The average differential pressure was 62 mm Hg; 6% had differential pressures of <20 mm Hg. The average oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 97%; in 6% of patients, SpO2 was <95%. Of patients in this subgroup, 54% had a GCS score of 14 or 15, 4% had a GCS score between 9 and 13, and 12% had a GCS score of <9.

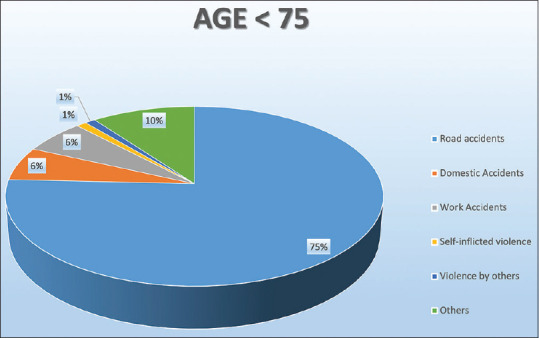

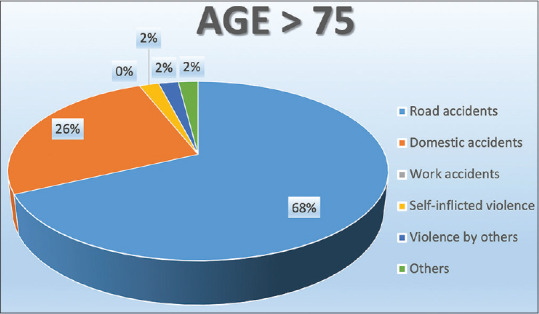

In the descending order, the causes of trauma were road accidents in 67% of cases, domestic accidents in 26%, self-inflicted violence in 2%, violence by others in 2%, and other causes in 3%; work accidents accounted for none of the cases [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Pie graph showing the most relevant causes of trauma in patients younger than 75 years old

With regard to transport to the emergency department, 6.25% of patients were transported by helicopter rescue, 21.21% by advanced rescue ambulance, and the remaining by basic rescue ambulance; no patients were transported by nursing rescue ambulance and no patients arrived on their own.

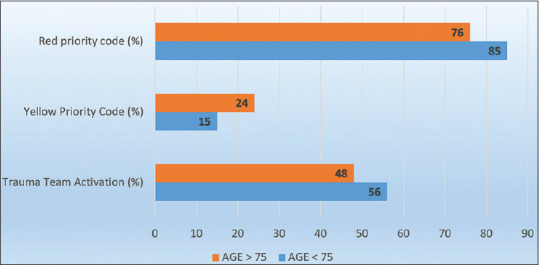

The priority code assigned at the time of triage was red in 78% of cases and yellow in 22% of cases; no cases were assigned a green code [Figure 2]. There are five levels of priority code for the medical examination in our ED:

Figure 2.

Bar graph showing the priority codes distribution and trauma team activation

Red code: Immediate entry into the shock room (high-intensity area). It is assigned to patients with severe impairment of vital signs or consciousness

Yellow code with medium care intensity: immediate or at least within 40 min, entry to the average intensity care area

Yellow code, low care intensity: immediate entry, or at least within 40 min, to the low intensity care area

Green code: Assigned to deferred urgency or minor emergencies with a wait of a few hours and entry to the low intensity of care area

White code: Nonurgent cases with a wait of a few hours and entry to the low intensity of care area.

The trauma team was activated completely for 42% of patients and partially for 6%.

With regard to the affected part of the body, head trauma was the most frequent (in 62% of cases), followed, in order of frequency, by chest trauma (52%), spine trauma (36%), pelvis trauma (26%), lower limb trauma (24%), abdominal trauma (22%), and upper limb trauma (14%). In 30% of cases, only one part of the body was affected; in 26%, two were affected; in 20%, three were affected; and in 16% of cases, four or more were affected.

Extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (E-FAST) showed free fluid in the abdomen in 2% of cases and pneumothorax or hemothorax in 4%. No patient was found to have free fluid in the pericardium.

The results of whole-body computed tomography (CT) scans were positive for hemorrhages in 68% of cases.

Patients with major trauma younger than 75 years

This group included 449 patients (rounds to 89% of the total); 27% were women and 73% were men. Trauma was diagnosed according to mechanism, anatomical, and hemodynamic criteria in 92%, 15%, and 9% of the total number of patients, respectively. The average heart rate in this subpopulation was 86 bpm; 7.3% of patients had a high heart rate (>110 bpm). The average systolic blood pressure was 129 mm Hg; 2.9% of patients had a systolic pressure of <90 mm Hg. The average differential pressure was 53 mm Hg; 0.66% had a differential pressure of <20 mm Hg. The average SpO2 was 98%; in 7.55% of patients, SpO2 was <95%. Of the patients in this subgroup, 95% had a GCS score of 14 or 15, 2% had a GCS score between 9 and 13, and 3% had a GCS score of <9.

In the descending order, the causes of trauma were road accidents in 76% of cases, domestic accidents in 6%, self-inflicted violence in 3%, work accidents in 7%, violence by others in 0.5%, and other causes in 7.5% [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Pie graph showing the most relevant causes of trauma in patients older than 75 years old

Regarding transport to the emergency department, 4% of patients were transported by helicopter, 29% by advanced rescue ambulance, and the remaining by basic rescue ambulance. No patients were transported by nursing rescue ambulance, and no patients arrived on their own.

The priority code assigned at the time of triage was red in 85% of cases and yellow in 15%; no cases were assigned a green code. The trauma team was activated completely for 46% of cases and partially for 10% [Figure 2].

Regarding affected areas of the body, chest trauma was the most frequent in 45% of cases, followed, in the order of frequency, by head trauma (44%), spine trauma (34%), lower limb trauma (26%), upper limb trauma (25%), abdominal trauma (14%), and pelvis trauma (13%). In 35% of cases, only one area of the body was affected; in 31%, two areas; in 16%, three areas; and in 12% of cases, four or more areas.

E-FAST showed free fluid in the abdomen in 1.1% of patients and in the pericardium in <0.2%; pneumothorax or hemothorax was observed in 1.8% of cases.

The results of whole-body CT scans were positive in 74.7% of cases.

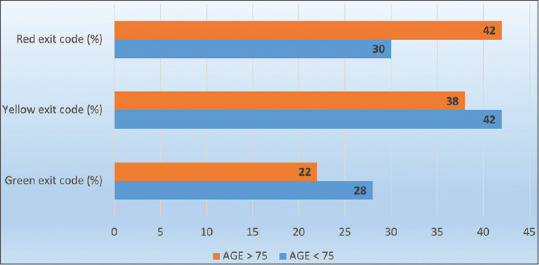

The comparison of exit codes distribution for patients younger and older than 75 years old is reported in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Bar graph showing the exit codes distribution

Outcomes

Mortality

The mortality rate was higher among the older patients (4%) than among the younger patients [1.33%; P = 0.050; Table 2].

Table 2.

Outcomes

| Age <75 | Age >75 | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical instability parameters | ||

| Mortality (%) | 1.33 | 4 |

| Hemodynamic instability (%) | 9.19 | 26.53 |

| SI >1.4 (%) | 1 | 6 |

| MSI >1.3 (%) | 6 | 10 |

| Age SI >65 (%) | 1 | 16 |

| Anatomic parameters | ||

| GCS <9 (%) | 3 | 12 |

| ISS >16 (%) | 32 | 44 |

| Biochemical parameters | ||

| BE <-6 (%) | 1.00 | 6.00 |

| Lac >1.9 (%) | 13.20 | 12.00 |

| Bleeding evaluation | ||

| Hemotransfusion need (%) | 3.78 | 2 |

| Trauma coagulopathy prevalence (%) | 36.2 | 38 |

| pH <7.35 (%) | 8.6 | 0 |

GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale, ISS: Injury Severity Score, SI: Shock Index, MSI: Modified SI, BE: Base Excess Level

Hemodynamic outcomes

Hemodynamic instability from trauma was more common in the older patients (26%) than in the younger patients [9%; P < 0.001; Table 2].

A shock index of >1.4 was more common in the older patients (6%) than in the younger patients (1.3%; P = 0.04). Older patients also more commonly had a modified shock index of >1.3 (10.8% vs. 6.9%; P = 0.13) and an age shock index of >65 [16% vs. 1.3%; P < 0.0001; Table 2].

A higher proportion of older patients (12%) also had GCS scores of <9 than did the younger patients [3%; P = 0.004; Table 2].

Anatomic and biochemical outcomes

The average ISS was 18 (10–75) for patients aged 75 years and older and 13.5 for younger patients; 44% of older patients also had an ISS >16, in comparison with 32% of younger patients [P = 0.01; Table 2]. The proportion of older patients with high lactate levels (>1.9 mmol/L) was similar to that of younger patients [12% vs. 13.20%; P = 0.83; Table 2]. A larger percentage of older patients (6%) had a base excess level of <6 than younger patients [1%; P = 0.036; Table 2].

Bleeding outcomes

Older patients needed less hemotransfusion support (blood transfusion rates were, in fact, 2% vs. 3.77%; P = 1), and the trauma-related coagulopathy rates in older and younger patients were similar [38% vs. 36.2%, respectively; P = 0.97; Table 2].

Older people have a lower rate of acidosis, defined by pH <7.35 [0% vs. 8.6%; P = 0.040; Table 2].

DISCUSSION

The mortality rate was significantly higher among older patients. This had already been reported in the 2016 Stop the Bleeding guidelines,[8] in which older patients were identified as a fragile population with regard to trauma. In that document, as well as in other reports,[9] it was also suggested that advanced age was one of the factors in mortality, along with some other pathological processes predisposing to unfavorable outcomes and with diagnoses according to the mechanism, anatomical, and hemodynamic criteria.[10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]

We found that trauma severity indices indicated significantly more impairment in elderly patients, as evidenced by the higher ISS value and shock indices. This was also reflected by a longer length of stay in the intensive care unit, which is also associated with severity of trauma. Our hypothesis, like those in other previous studies,[4,19,20,21] was that these findings were related mainly to the reduced functional reserve of elderly patients. The reduction in functional reserve not only reduces adaptability of the respiratory[22] and circulatory systems to stress conditions but also reduces the ability of tissues to respond properly to kinetic energy. This decrease in functional reserve is reflected by reduced muscular trophism, increased osteoporosis, and therefore, also reduced bone density.[23] In our opinion, this issue remains independent from bleeding.

Our hypothesis was supported by the fact that in our study, there is no correlation between age and the presence of trauma-related coagulopathy. E-FAST examination revealed lower rates of abdominal bleeding in elderly patients, who also required less hemotransfusion. They also had a lower rate of acidosis, which is known to be a factor in bleeding.

Elderly patients seem to have worse outcomes after severe trauma, regardless of bleeding. This finding is related in part not only to the greater fragility of these patients but also to a higher rate of comorbidities. Similar findings have been noted with other pathological conditions, most commonly oncological and neurovascular disorders.[24,25,26,27,28,29] With regard to the criteria for diagnosing trauma, the distribution of this diagnosis in elderly patients is very different from that in the younger population. In fact, elderly patients have lower rates of road trauma and work-related trauma and higher rates of domestic accidents and violence by other people.

In view of even minor dynamics, the reduced functional reserve of the elderly, in our opinion, results in impairment of a wider range of physiological parameters than in younger patients. A slowing of reflexes in elderly people can also result in unprotected falls and a consequent increased prevalence of head trauma.[50,51,52,53] This may also partly explain why greater severity of injury and mortality were more common in older patients. Young people have a greater reserve, and therefore, with the same trauma, could exhibit only minor clinical and physiological problems.

We also noted a relative reduction in proportion of elderly men who suffered severe trauma. The explanation may be that young men tend to be more prone to trauma both at work and because of lifestyle. The prevalence of domestic accidents to which men and women are equally exposed also increases as people age. In our patient population, the trauma team was less frequently activated for older patients, although the difference was not statistically significant. Moreover, the number of red codes for the medical examination was lower for older patients. We suggest a higher rate of consideration for trauma team activation in this population; since they may have more severe trauma, despite slightly lower trauma dynamics, as already suggested in previous studies.[9]

Data analysis also shows that older people are often undervalued, with fewer triage measures and fewer urgent medical priority codes.[54,55,56]

CONCLUSIONS

Older patients showed worse outcomes with regard to mortality, hospitalization rates, hemodynamic instability, and anatomical and biochemical data. We believe that these worse outcomes may be attributed to the reduced functional reserve of elderly patients and not to a higher rate of bleeding. Elderly patients are most often subjected to undertriage.

Research quality and ethics statement

This study was approved by the Internal Review Board of Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy. PROT N 20180059069; PROC N: 20180017957. The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network (http://www.equator-network.org/) guidelines during the conduct of this research project.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Soreide K. Epidemiology of major trauma. Br J Surg. 2009;96:697–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehoe A, Smith JE, Edwards A, Yates D, Lecky F. The changing face of major trauma in the UK. Emerg Med J. 2015;32:911–5. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2015-205265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaway DW, Wolfe R. Geriatric trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25:837–60. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atinga A, Shekkeris A, Fertleman M, Batrick N, Kashef E, Dick E. Trauma in the elderly patient. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20170739. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perdue PW, Watts DD, Kaufmann CR, Trask AL. Differences in mortality between elderly and younger adult trauma patients: Geriatric status increases risk of delayed death. J Trauma. 1998;45:805–10. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199810000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dick WF, Baskett PJ. Recommendations for uniform reporting of data following major trauma – The Utstein style. A report of a working party of the International Trauma Anaesthesia and Critical Care Society (ITACCS) Resuscitation. 1999;42:81–100. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(99)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trauma, A.C.o.S.C.o. ATLS®. Saint Clair Street Chicago: IL; 2018. advanced trauma life support student course manual; American College of Surgeons: 633 N; pp. 60611–3211. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossaint R, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Coats TJ, Duranteau J, Fernández-Mondéjar E, et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: Fourth edition. Crit Care. 2016;20:100. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1265-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demetriades D, Sava J, Alo K, Newton E, Velmahos GC, Murray JA, et al. Old age as a criterion for trauma team activation. J Trauma. 2001;51:754–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200110000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millimaggi DF, Norcia VD, Luzzi S, Alfiero T, Galzio RJ, Ricci A. minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with percutaneous bilateral pedicle screw fixation for lumbosacral spine degenerative diseases. A retrospective database of 40 consecutive cases and literature review. Turk Neurosurg. 2018;28:454–61. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.19479-16.0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsawaf Y, Anetsberger S, Luzzi S, Elbabaa SK. Early decompressive craniectomy as management for severe TBI in the pediatric population: A comprehensive literature review. World Neurosurg. 2020;138:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnaout MM, Luzzi S, Galzio R, Aziz K. Supraorbital keyhole approach: Pure endoscopic and endoscope-assisted perspective. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019;189:105623. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savioli G, Ceresa IF, Macedonio S, Gerosa S, Belliato M, Iotti GA, et al. Trauma Coagulopathy and Its Outcomes. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020;56:205. doi: 10.3390/medicina56040205. doi: 10.3390/medicina56040205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savioli G, Ceresa IF, Luzzi S, Gragnaniello C, Giotta Lucifero A, Del Maestro M, et al. Rates of Intracranial Hemorrhage in Mild Head Trauma Patients Presenting to Emergency Department and Their Management: A Comparison of Direct Oral Anticoagulant Drugs with Vitamin K Antagonists. Medicina (Kaunas)? 2020;56:308. doi: 10.3390/medicina56060308. doi: 10.3390/medicina56060308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savioli G, Ceresa IF, Ciceri L, Sciutti F, Belliato M, Iotti GA, et al. Mild head trauma in elderly patients: experience of an emergency department. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04226. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04226. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holleran RS. Elderly trauma. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2015;38:298–311. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hruska K, Ruge T. The tragically hip: Trauma in elderly patients. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2018;36:219–35. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reske-Nielsen C, Medzon R. Geriatric Trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2016;34:483–500. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yildiz M, Bozdemir MN, Kiliçaslan I, Ateşçelik M, Gürbüz S, Mutlu B, et al. Elderly trauma: The two years experience of a university-affiliated emergency department. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(Suppl 1):62–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banks SE, Lewis MC. Trauma in the elderly: Considerations for anesthetic management. Anesthesiol Clin. 2013;31:127–39. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhne CA, Ruchholtz S, Kaiser GM, Nast-Kolb D. Working Group on Multiple Trauma of the German Society of T. Mortality in severely injured elderly trauma patients – When does age become a risk factor? World J Surg. 2005;29:1476–82. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7796-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaugg M, Lucchinetti E. Respiratory function in the elderly. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 2000;18:47–58, vi. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(05)70148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pudelek B. Geriatric trauma: Special needs for a special population. AACN Clin Issues. 2002;13:61–72. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricci A, Di Vitantonio H, De Paulis D, Del Maestro M, Raysi SD, Murrone D, et al. Cortical aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery: A review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:117. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_50_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luzzi S, Crovace AM, Del Maestro M, Lucifero AG, Elbabaa SK, Cinque B, et al. The cell-based approach in neurosurgery: Ongoing trends and future perspectives. Heliyon. 2019;5:e02818. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luzzi S, Giotta Lucifero A, Del Maestro M, Marfia G, Navone SE, Baldoncini M, et al. Anterolateral approach for retrostyloid superior parapharyngeal space schwannomas involving the jugular foramen area: A 20-year experience. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:e40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sterling DA, O’Connor JA, Bonadies J. Geriatric falls: Injury severity is high and disproportionate to mechanism. J Trauma. 2001;50:116–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200101000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.St John AE, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Arbabi S, Bulger EM. Role of trauma team activation in poor outcomes of elderly patients. J Surg Res. 2016;203:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun G, Xue J, Zhang Y, Gao X, Guo F. Short-and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery in elderly patients with rectal cancer. J BUON. 2018;23:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Q, Zou C, Wu C, Zhang S, Huang Z. Risk factors of outcomes in elderly patients with acute ischemic stroke in China. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28:705–11. doi: 10.1007/s40520-015-0478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexiou KI, Roushias A, Varitimidis SE, Malizos KN. Quality of life and psychological consequences in elderly patients after a hip fracture: A review. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:143–50. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S150067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoller N, Limacher A, Mean M, Baumgartner C, Tritschler T, Righini M, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes in elderly patients with symptomatic isolated subsegmental pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2019;184:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin LS, Rozell JC, Pulos N. Distal radius fractures in the elderly. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:179–87. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Righi E, Merelli M, Bassetti M. Elderly versus non-elderly patients with intra-abdominal candidiasis in the ICU. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017;83:1126–36. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.17.11528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee MS, Shlofmitz E, Lluri G, Shlofmitz RA. Outcomes in elderly patients with severely calcified coronary lesions undergoing orbital atherectomy. J Interv Cardiol. 2017;30:134–8. doi: 10.1111/joic.12362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamato Y, Hasegawa T, Togawa D, Yoshida G, Banno T, Arima H, et al. Rigorous correction of sagittal vertical axis is correlated with better ODI outcomes after extensive corrective fusion in elderly or extremely elderly patients with spinal deformity. Spine Deform. 2019;7:610–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan SP, Ip KY, Irwin MG. Peri-operative optimisation of elderly and frail patients: A narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(Suppl 1):80–9. doi: 10.1111/anae.14512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh S, Patel PS, Doley PK, Sharma SS, Iqbal M, Agarwal A, et al. Outcomes of hospital-acquired acute kidney injury in elderly patients: A single-centre study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2019;51:875–83. doi: 10.1007/s11255-019-02130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yokota Y, Tomimaru Y, Noguchi K, Noda T, Hatano H, Nagase H, et al. Surgical outcomes of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in elderly patients. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2019;12:157–61. doi: 10.1111/ases.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liao JC, Chen WJ. Surgical outcomes in the elderly with degenerative spondylolisthesis: Comparative study between patients over 80 years of age and under 80 years-a gender-, diagnosis-, and surgical method-matched two-cohort analyses. Spine J. 2018;18:734–9. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.08.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daud MY, Awan MS, Khan M, Hayat U, Tuyyab F. Procedural outcomes of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in elderly patients with stemi. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2018;30:585–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rupp K, Dushi I. Accounting for the process of disablement and longitudinal outcomes among the near elderly and elderly. Res Aging. 2017;39:190–221. doi: 10.1177/0164027516656141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grammatica A, Piazza C, Paderno A, Taglietti V, Marengoni A, Nicolai P. Free flaps in head and neck reconstruction after oncologic surgery: Expected outcomes in the elderly. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:796–802. doi: 10.1177/0194599815576905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aratani K, Sakuramoto S, Chuman M, Kasuya M, Wakata M, Miyawaki Y, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer in elderly patients: Surgical outcomes and prognosis. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:1721–5. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joyce MF, Gupta A, Azocar RJ. Acute trauma and multiple injuries in the elderly population. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28:145–50. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee JJ, Lien CY, Huang CR, Tsai NW, Chang CC, Lu CH, et al. Clinical characteristics and therapeutic outcomes of postneurosurgical bacterial meningitis in elderly patients over 65: A hospital-based study. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2017;26:144–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hennessy D, Juzwishin K, Yergens D, Noseworthy T, Doig C. Outcomes of elderly survivors of intensive care: A review of the literature. Chest. 2005;127:1764–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lim WX, Kwek EB. Outcomes of an accelerated nonsurgical management protocol for hip fractures in the elderly. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2018;26 doi: 10.1177/2309499018803408. 2309499018803408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ekerstad N, Karlsson T, Soderqvist S, Karlson BW. Hospitalized frail elderly patients – Atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation and 12 months' outcomes. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:749–56. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S159373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dixon J.R, Lecky F, Bouamra O, Dixon P, Wilson F, Edwards A, et al. Age and the distribution of major injury across a national trauma system. Age Ageing. 2020;49:218–226. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz151. doi:10.1093/ageing/afz151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gowing R, Jain MK. Injury patterns and outcomes associated with elderly trauma victims in Kingston, Ontario. Can J Surg. 2007;50:437–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ng W, Fujishima S, Suzuki M, Yamaguchi K, Aoki K, Hori S, et al. Characteristics of elderly patients presenting to the emergency department with injury. Keio J Med. 2002;51:11–6. doi: 10.2302/kjm.51.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gioffre-Florio M, Murabito LM, Visalli C, Pergolizzi FP, Fama F. Trauma in elderly patients: A study of prevalence, comorbidities and gender differences. G Chir. 2018;39:35–40. doi: 10.11138/gchir/2018.39.1.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiang H, Wheeler KK, Groner JI, Shi J, Haley KJ. Undertriage of major trauma patients in the US emergency departments. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:997–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang DC, Bass RR, Cornwell EE, Mackenzie EJ. Undertriage of elderly trauma patients to state-designated trauma centers. Arch Surg. 2008;143:776–81. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.8.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Staudenmayer KL, Hsia RY, Mann NC, Spain DA, Newgard CD. Triage of elderly trauma patients: A population-based perspective. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:569–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]