Abstract

β-particle emitting radionuclides, such as 3H, 14C, 32P, 33P, and 35S, are important molecular labels due to their small size and the prevalence of these atoms in biomolecules but are challenging to selectively detect and quantify within aqueous biological samples and systems. Here, we present a core-shell nanoparticle-based scintillation proximity assay platform (nanoSPA) for the separation-free, selective detection of radiolabeled analytes. nanoSPA is prepared by incorporating scintillant fluorophores into polystyrene core particles and encapsulating the scintillant-doped cores within functionalized silica shells. The functionalized surface enables covalent attachment of specific binding moieties such as small molecules, proteins, or DNA that can be used for analyte-specific detection. nanoSPA was demonstrated for detection of 3H-labeled analytes, the most difficult biologically relevant β-emitter to measure due to the low energy β-particle emission, using three model assays that represent covalent and non-covalent binding systems that necessitate selectivity over competing 3H-labeled species. In each model, nmol quantities of target were detected directly in aqueous solution without separation from unbound 3H-labeled analyte. The nanoSPA platform facilitated measurement of 3H-labeled analytes directly in bulk aqueous samples without surfactants or other agents used to aid particle dispersal. Selectivity for bound 3H-analytes over unbound 3H analytes was enhanced up to 30-fold when the labeled species was covalently bound to nanoSPA, and 4- and 8-fold for two non-covalent binding assays using nanoSPA. The small size and enhanced selectivity of nanoSPA should enable new applications compared to the commonly used microSPA platform, including the potential for separation-free, analyte-specific cellular or intracellular detection.

Keywords: Scintillation proximity assay, core-shell nanoparticle, β-emission, radioisotope, composite nanomaterial

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Radionuclides are attractive molecular labels that do not significantly increase the size or mass of the labeled component compared to fluorescent or fluorogenic tags. Thus, radionuclides minimally affect binding, conformational changes, diffusion, and active transport. Lower background signals, and correspondingly higher sensitivity, are typically obtained for radioassays compared to fluorescence assays.1–3 Radioassays are broadly used to investigate biochemical pathways, enzyme activity4–5 and ligand-receptor binding events. Radioassays provide high sensitivity, thus enabling quantification at sub-pM concentrations.6–7 However, 3H, 14C, 33P, and 35S are challenging to quantify directly in aqueous media due to their low decay energies (Emax from 18.6 to 1,710 keV) and short β-particle penetration depths (from 4.3 μm to 7.9 mm at Emax).8–10

β-particle emission from radiolabeled analytes is commonly quantified using liquid scintillation counting techniques where aqueous samples are dispersed in liquid scintillation cocktails (LSC). LSCs are mixtures comprised of aromatic, light-absorbing hydrocarbons (e.g., toluene, diisopropylnaphthalene, alkylbenzenes), surfactants, and scintillant fluorophores that are used to disperse the analytes and shift the energy from the decay event into the UV or visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum via energy transfer.8, 11 While highly sensitive, LSC enables measurement only at a single time point for most biomolecular systems due to the high proportion of organic solvent. Solid scintillators, prepared from scintillant-doped polymers (e.g., polyvinyltoluene or polystyrene) or inorganic crystals (e.g., CdWO4, CeF3) and molded to form microwells or synthesized or ground into microparticle structures, can be used in place of LSC to enable aqueous measurement, though typically with lower sensitivity.8, 12–13 Porous scintillating polymer bead resins have been developed for the detection of β and α particles but these resins typically rely upon the extraction of radioactive metals using chelating ligands at the particle surface, limiting their use for biologically relevant β-emitters such as 3H, 35S, and 33P.14–17

In both liquid and solid scintillation measurements, the lack of inherent analyte selectivity presents a major drawback. Both approaches detect the β-decay event resulting from the isotope via the energy transferred through the matrix. Isotopes yield distinct decay energies, but the distribution of decay energies for a given isotope is indistinguishable when incorporated into different molecular species, limiting the selectivity. For example, substrates and products of an enzymatic reaction cannot be distinguished using LSC or solid scintillation approaches in a homogenous manner. Radioassays, therefore, often require pre-separation of the analyte mixture, which imparts significant limitations on the assay, particularly with respect to spatial and temporal resolution.

Scintillation proximity assays (SPA) were developed to overcome these limitations and prepare homogenous radioassays.8, 18 SPA is a derivative of solid scintillation counting, wherein specific binding of radiolabeled analyte to a solid scintillator surface serves to increase the probability of energy absorption by the scintillator (Figure 1) and thus detection of the decay event. When the decay event occurs near the scintillator surface, the detection probability is enhanced resulting in increased photon emission from the solid scintillator upon analyte binding.8, 18 SPA is particularly useful for low energy β-particles that exhibit low penetration depths, e.g. 3H (dp ≈ 0.5 μm in H2O).8 Consequently, SPA lends itself to monitoring binding kinetics under steady state conditions,18–22 as well as separation-free, selective quantification of radiolabeled analytes in complex mixtures.

Figure 1.

nanoSPA platform. a) Schematic illustrating the function of nanoSPA. When radioisotope decay occurs near the nanoSPA surface (right), enhanced photoemission is observed, compared to radioisotope decay in solution beyond the penetration depth of the β-particle (left). TEM images of nanoSPA particles with b) hydroxyl-functionalized silica shells, c) amine-functionalized silica shells, and d) thiol-functionalized silica shells.

Modern SPA particle formats utilize scintillant-doped polyvinyltoluene (PVT) or polystyrene (PS) particles, or yttrium silicate (YSi) or yttrium oxide (YOx) microparticles, to which receptors have been covalently attached.20, 23–26 SPA has been used to measure quantitative binding and/or binding kinetics of enkephalins, thyroxin, morphine, inositol phosphates, and many other analytes.19, 21, 27–34 These encouraging applications demonstrate the key advantages of SPA, including the ability to perform time-resolved analyte measurements, high selectivity, and separation-free assays. Current SPA platforms are limited by the large size of SPA particles (5–10 μm) which results in low surface area to volume ratios, as well as particle settling. Additionally, these sizes preclude the potential application of SPA for intracellular measurements under most circumstances. Thus, reduced SPA particle sizes may provide enhanced utility for SPA applications as well as enable new radioassay platforms to be developed and implemented for investigating biological systems.

Here, we report a nanoparticle-based SPA format (referred to herein as nanoSPA, Figure 1a) based upon a recently reported core-shell, radioisotope-responsive nanomaterial.35 PS was selected as the core material due to its low cost and compatibility with scintillant fluorophores.36–38 The addition of silica shells to the scintillant fluorophore-doped PS particles makes the particles hydrophilic without using surfactants, which are often required for the dispersion of PVT and PS nano- and microparticles in aqueous samples, and facilitates the covalent attachment of binding receptors to the exterior nanoparticle surface. Furthermore, while the density of the core-shell nanoparticles allows the particles to remain dispersed in a sample, the core-shell nanoparticles can be easily recovered via centrifugation enabling sample enrichment and isolation as well as reuse of the particles if desired.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Styrene, alumina, p-terphenyl (pTP), and 1,4-bis(4-methyl-5-phenyl-2-oxazolyl)benzene (dimethyl POPOP) were purchased from Acros Organics (NJ). Tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS), (3-mercaptopropyl)trimethoxysilane (MPTS), (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AIBA), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDAC HCl), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), biotin-PEG-NHS (Mw = 3000) and Tween-20 were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dimethylsulfoxide was purchased from Fisher Chemical (Hampton, NH). PEG6–9-dimethylchlorosilane (90%) was purchased from Gelest (Morrisville, PA). Isopropyl alcohol (IPA), chloroform, aqueous ammonium hydroxide (28%) and acetonitrile were obtained from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Ethyl alcohol was purchased from Decon Laboratories (King of Prussia, PA). BioCount liquid scintillation cocktail was purchased from Research Products International (Mt. Prospect, IL). 3H-labeled sodium acetate (1.59 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA). NeutrAvidin was purchased from Pierce Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA), and Nanosep centrifugal devices with 3 kDa MWCO membranes were purchased from Sartorius (Göttingen, Germany). All chemicals except styrene were used as received. Inhibitor was removed from styrene by passing the monomer through a 0.5 cm diameter by 3 cm long alumina column immediately prior to use.

Acrydite-functionalized DNA oligomers 5’-/Acryd/AAA CCC TGT AAA CCC TGT AAA CCC TGT AAA-3’ and amine-functionalized DNA oligomers 5’-/5AmMC6/TTT ACA GGG TTT ACA GGG TTT ACA GGG TTT-3’ (complementary oligomer), 5’-/5AmMC6/TTT ACA GAG TTT AGA GGG TTG ACA GGG ATT (4-base mismatched oligomer), and 5’-/5AmMC6/AGC ACT GAG AGA AGA GTG TTG ACA CAT ATT-3’ (random-sequence 30-base oligomer) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA).

All scintillation measurements were performed using a Beckman LS 6000 IC scintillation counter.

Precautions

All radioactive materials should be handled and disposed according to federal, state, and local guidelines. Styrene is flammable, is an irritant, and is a health hazard. Ethyl acetate, ethyl alcohol, isopropyl alcohol, TEOS and AIBA and acetonitrile are flammable and are irritants. MTPS and pTP are irritants and hazardous to aquatic life. APTES is corrosive and an irritant. EDAC HCl and PEG6–9-dimethylchlorosilane are irritants. Chloroform exhibits acute toxicity and is a health hazard. Ammonium hydroxide solution is corrosive, an irritant, and hazardous to aquatic life.

Preparation of nanoSPA Particles

Scintillant fluorophore-doped PS core nanoparticles were prepared following the protocol described previously.35 Briefly, styrene (3 g, inhibitor-free) was added to 100 mL degassed H2O in an Ar-flushed 500 mL round-bottomed flask heated to 70 °C in an oil bath. Polymerization was initiated by adding 10 mg of AIBA dissolved in approximately 200 μL of H2O to the reaction flask. The H2O/styrene mixture was stirred rapidly for at least 6 h. Excess styrene and some H2O were removed from the nanoparticle solution under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator to reduce the total volume to approximately 100 mL. A 1–2 mL aliquot of the solution was removed and lyophilized to determine the mass-based concentration (mg/ml) of polystyrene core nanoparticles.

PS nanoparticles were doped with scintillant fluorophores by dissolving 53 mg (135 mmol) of dimethyl POPOP and 262 mg (1.14 mmol) of pTP in 20 mL of 1:9 isopropyl alcohol/chloroform (v:v). Scintillant fluorophores dissolved in solvent were added directly to the aqueous PS nanoparticle solution in a 500 mL round-bottomed flask. The nanoparticle solution was agitated using a bath sonicator for several minutes to disperse organic solvent droplets throughout the H2O and the solution was stirred rapidly for at least 1 h. Organic solvents were then removed under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator.

Silica shells were added to scintillant fluorophore-doped PS nanoparticles by dispersing 2 mL PS nanoparticle stock solution (approximately 56 mg nanoparticles) in 200 mL isopropyl alcohol with 38 mL H2O. For hydroxyl- or thiol- functionalized silica shells, 7.5 mL NH4OH was added to the flask. For amine functionalized shells, 5.0 mL NH4OH was added to the flask. The dispersion was stirred briskly for several minutes while either 2.0 mL of TEOS or a mixture containing 1.8 mL TEOS and 0.2 ml of either APTES or MPTS was added dropwise. Stirring was continued for 1 h before particles were collected by centrifugation and rinsed several times with H2O.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Transmission electron micrographs of nanoparticles were obtained by drying a 10 μL aliquot of nanoparticle solutions on carbon films deposited on copper grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield PA). Samples were observed using a Technai G2 Spirit transmission electron microscope at 100 kV accelerating voltage (FEI Company, Hillsboro OR).

Direct Attachment of 3H-Sodium Acetate to nanoSPA

3H-labeled succinimidyl acetate was synthesized by reacting 3H-labeled sodium acetate (300 nmol, 45 μL of 1 μCi/mL, 150 mCi/mmol) with EDAC HCl (767 μmol) and NHS (800 μmol) in 100 μL H2O. After 1.5 h reaction time, increasing volumes of the mixture (1–10 μL) were added to 0.1 mg amine-functionalized nanoSPA in 150 μL 25 mM borate buffer, pH 8.0. As a control, equivalent activities of 3H-labeled sodium acetate (not treated with EDAC HCl and NHS) was added to amine-functionalized nanoSPA. After 30 min reaction time, 145 μL of the reaction mixture was diluted with 10 mL H2O immediately prior to measurement with the scintillation counter.

nanoSPA Functionalization with Biotin and PEG

Amine-functionalized nanoSPA particles (200 mg) was suspended in 10 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (0.1 M sodium phosphate, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.40). Biotin-PEG-NHS (23 mg, Mw = 3000) was added into the particle solution and allowed to react overnight (>12 h) with mixing. The particles were washed with PBS three times, and then resuspended in PBS to make a 20 mg/mL particle solution. A 100 mg sample of biotinylated nanoSPA was collected by centrifugation at 1,600 × g for 10 min and then washed with acetonitrile three times. The particles were resuspended in 5 mL solution of 2% PEG6–9-dimethylchlorosilane in dry acetonitrile (v/v) and allowed to react, with mixing overnight. The particles were then washed successively three times with acetonitrile, three times with ethanol, and three times with water. The particles were finally suspended in water (20 mg/mL). Another sample of non-passivated particles were prepared using biotin-PEG-NHS but were not treated with PEG6–9-dimethylchlorosilane. A third set of particles was not biotinylated but was passivated with treatment of PEG6–9-dimethylchlorosilane for comparison.

Radiolabeling of NeutrAvidin

NeutrAvidin was tritiated by conjugating to 3H-labeled sodium acetate using EDAC/NHS coupling chemistry. 3H-labeled sodium acetate (390 nmol, corresponding to 600 μCi activity) was reacted with EDAC HCl (200 μmol), and NHS (200 μmol) in 100 μL DMSO at 25 °C for 1 h. Protein (6.0 mg NeutrAvidin) was dissolved in 1 mL PBS and added to the 3H-labeled sodium acetate/EDAC HCl/NHS mixture and allowed to react at room temperature overnight. 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin was then purified from other tritiated species using a molecular weight cut off centrifugal filter (3 kDa for NeutrAvidin) and resuspended in PBS.

Biotin/NeutrAvidin nanoSPA

Biotin-functionalized nanoSPA (1.5 mg) was dispersed in 1 mL PBS with increasing activities of 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin (0.25 nmol/μL protein solution with 334 nCi/μL activity and 1.33 Ci/mmol specific activity). As a control for non-proximity effects, equal activities of 3H-labeled sodium acetate were added in place of labeled protein. All samples were prepared in triplicate.

nanoSPA Functionalization with ssDNA

Thiol-functionalized nanoSPA (50 mg) was dispersed in 1 mL 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and was reacted with 80 nmol acrydite-functionalized 30-mer ssDNA for 72 h at room temperature with brisk stirring. Particles were rinsed several times with PBS and resuspended in the same buffer. Control nanoSPA was prepared using the same procedure by omitting the ssDNA from the reaction mixture.

Radiolabeling of ssDNA

Complementary and random sequence ssDNA were tritiated via conjugation to 3H-labeled sodium acetate using EDAC/NHS coupling chemistry. 3H-labeled sodium acetate (100 nmol corresponding to 154 μCi activity) was reacted with EDAC HCl (10 μmol) and NHS (10 μmol) in 30 μL dimethylformamide (DMF) by stirring the solution for 3 h at 25 °C. Amine-functionalized oligonucleotide (100 nmol) was dissolved in 90 μL 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 9.5 and mixed with 3H-labeled sodium acetate/EDAC HCl/NHS solution. The mixture was stirred briskly for 3 h at room temperature and then separated using a Sephadex G-50 column (packed bed volume approximately 3 mL). Column fractions were subjected to scintillation counting and specific activity of radiolabeled ssDNA was estimated by dividing the area of the labeled ssDNA peak by total peak area and multiplying by 154 μCi/100 nmol.

ssDNA Hybridization nanoSPA

ssDNA-functionalized nanoSPA (5 mg) were dispersed in 5 mL annealing buffer (100 mM phosphate, 50 mM NaCl and 10 mM EDTA; pH 7.4) containing 0.1% Tween-20 in a 7 mL-scintillation vial. nanoSPA samples were then titrated with increasing amounts of 3H-labeled complementary ssDNA (i.e. 0, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 nmol). DNA was hybridized by heating the samples at 70 °C for 5 min and allowed to cool to room temperature for 40 min while shaking at 300 rpm prior to each scintillation measurement. As a control, non-functionalized core-shell nanoparticles were also subjected to similar hybridization procedure. All samples were prepared in triplicate and measured three times each.

The affinity of immobilized ssDNA to three different 30-mer ssDNA strands (complementary ssDNA oligomer, 4-base mismatch oligomer, and random-sequence oligomer) was also tested by binding inhibition. 5 mg of ssDNA-functionalized nanoSPA were saturated with 3H-labeled complementary ssDNA (approximately 6 nmol) and titrated with increasing amounts of unlabeled complementary, 4-base mismatch, or random-sequence strands (i.e. 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 nmol). Prior to each scintillation measurement, samples were heated at 70 °C for 5 min and allowed to cool to room temperature for 40 min while being shaken at 300 rpm.

Determination of Detection Limits and Selectivity

The limits of detection (LOD) for the direct attachment of 3H-labeled sodium acetate, and for the binding of 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin to biotin-functionalized nanoSPA, were calculated using the equation LOD = ksblk/m, where k = 3 and sblk is the standard deviation of the measurements of the blank samples, and m is slope of the least-squares fit line for data points at increasing analyte concentrations. For the direct attachment of 3H-labeled sodium acetate, the first 6 data points were used for least-squares fitting, omitting the data point at 6 nmol. For the binding of 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin, the data points from 0 to 0.5 nmol were used in the calculation. For these model assays, selectivity at the highest activity was calculated as the ratio of the magnitude of the SPA response divided by the magnitude of the non-specific binding response.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

nanoSPA particles were prepared using a core-shell architecture to maximize dispersion and aqueous compatibility yet retain an environment suitable for β-decay stimulated scintillation. The silica shell increases compatibility with aqueous solutions, reduces aggregation typically seen with PS particles and serves as a platform for further surface modification whereas the PS core enables dispersion of scintillant fluorophores in a hydrophobic environment that serves as an energy transfer matrix. SPA efficiency is partly dependent upon the efficiency with which energy from radioactive decay is absorbed, which in turn is related to the pathlength of β-particles through the absorbing medium,8 thus smaller PS core nanoparticles might lead to severely reduced absorption and insufficient signal during measurement in commercially available liquid scintillation counters. Conversely, enhanced energy absorption efficiency leads to greater signal, but may also result in larger non-proximity signal, making signal differentiation difficult or impossible. The proximity signal to non-proximity signal ratio is also dependent upon radionuclide activity, Emax, and particle concentration. Thus, nanoSPA particles were designed with PS cores large enough to absorb adequate energy and provide sufficient signal at nCi activities, but small enough to reduce non-proximity signals, remain easily dispersible in solution and maximize the surface area to volume ratio.

The PS cores of nanoSPA particles were prepared in a surfactant-free emulsion polymerization, into which scintillant fluorophores were incorporated after polymerization via solvent-induced swelling.39–41 For initial nanoSPA experiments p-terphenyl (pTP) was used as a primary scintillant fluorophore, and 4-bis(4-methyl-5-phenyl-2-oxyzolyl)benzene (dimethyl POPOP) was used as a wavelength-shifting, secondary scintillant fluorophore. Previously, we reported silanol terminated silica shell deposition.35 Here, we have expanded the range of surface functionalities by combining 10% functional silane (3-(aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) or 3-mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane (MPTS) with tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) during shell synthesis to make amine- or thiol- functionalized silica shells on the scintillant-doped cores. Functionalization in this manner is simple and significantly expands the surface functionalization capabilities by providing the necessary surface functionality for widely used linkers, including N-hydroxy succinimidyl esters and maleimides. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Figure 1) show 150–200 nm scintillant-loaded PS core nanoparticles (PS core nanoparticles) surrounded by denser silica shells 25–50 nm thick. Whereas the scintillant-loaded PS cores appear smooth, irrespective of silane modification, the morphology of the silica shell varies dependent upon the silane functionality. For both TEOS and APTES modified silica shells, a smooth surface was observed (Figure 1b–1c) compared to MPTS, where a rough surface was observed (Figure 1d). Thus, the surface morphology and roughness of silica shells on core-shell nanoparticles depend on reaction pH and the rates of silica sol nucleation and growth, similar to the observations of Lu et al.42

Initially, the surface charge characteristics of nanoSPA particles were examined by measuring zeta potential in 100 mM NaCl solutions of varying pH, from 3 to 10 (Figure S-1a, Supporting Information) to determine the stability of an aqueous nanoSPA dispersions.43–46 The zeta potential of nanoSPA particles with amine-functionalized shells decreased significantly with increasing pH, approaching −8.0 mV at pH 10. This trend can be attributed to protonation of the amine at low pH, and a combination of deprotonation and hydrolysis at high pH.47–48 The zeta potential of nanoSPA particles with hydroxyl- or thiol-functionalized shells was ≤ −5 mV at pH 4 or lower, and decreased slightly to −11 mV and −7 mV, respectively, at pH 5. These suggest that nanoSPA particles with hydroxyl or thiol functionalized shells may aggregate in very acidic samples, and nanoSPA particles with amine-functionalized shells may aggregate at very alkaline pH. However, biological samples are unlikely to have such extreme pH conditions. Furthermore, no change in particle size was indicated by light scattering or turbidimetry measurements acquired over a period of 10 days (Figure S-1b–d, Supporting Information), demonstrating that nanoSPA particles with hydroxyl, amine, and thiol functionalized shells are readily dispersed in aqueous media.

The amine and thiol functional groups on the silica shells were subsequently used for covalent attachment of binding elements to nanoSPA to demonstrate proof-of-concept nanoSPA-based radioassays. Three model nanoSPAs were utilized: 1) 3H-labeled sodium acetate was covalently bound to the nanoSPA particle surface using N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDAC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) coupling, 2) biotin-functionalized nanoSPA particles were used to measure 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin, and 3) ssDNA-functionalized nanoSPA was used to bind the complementary ssDNA oligomer. These assays were chosen to demonstrate selectivity, sensitivity, and maximum enhancement efficiency.

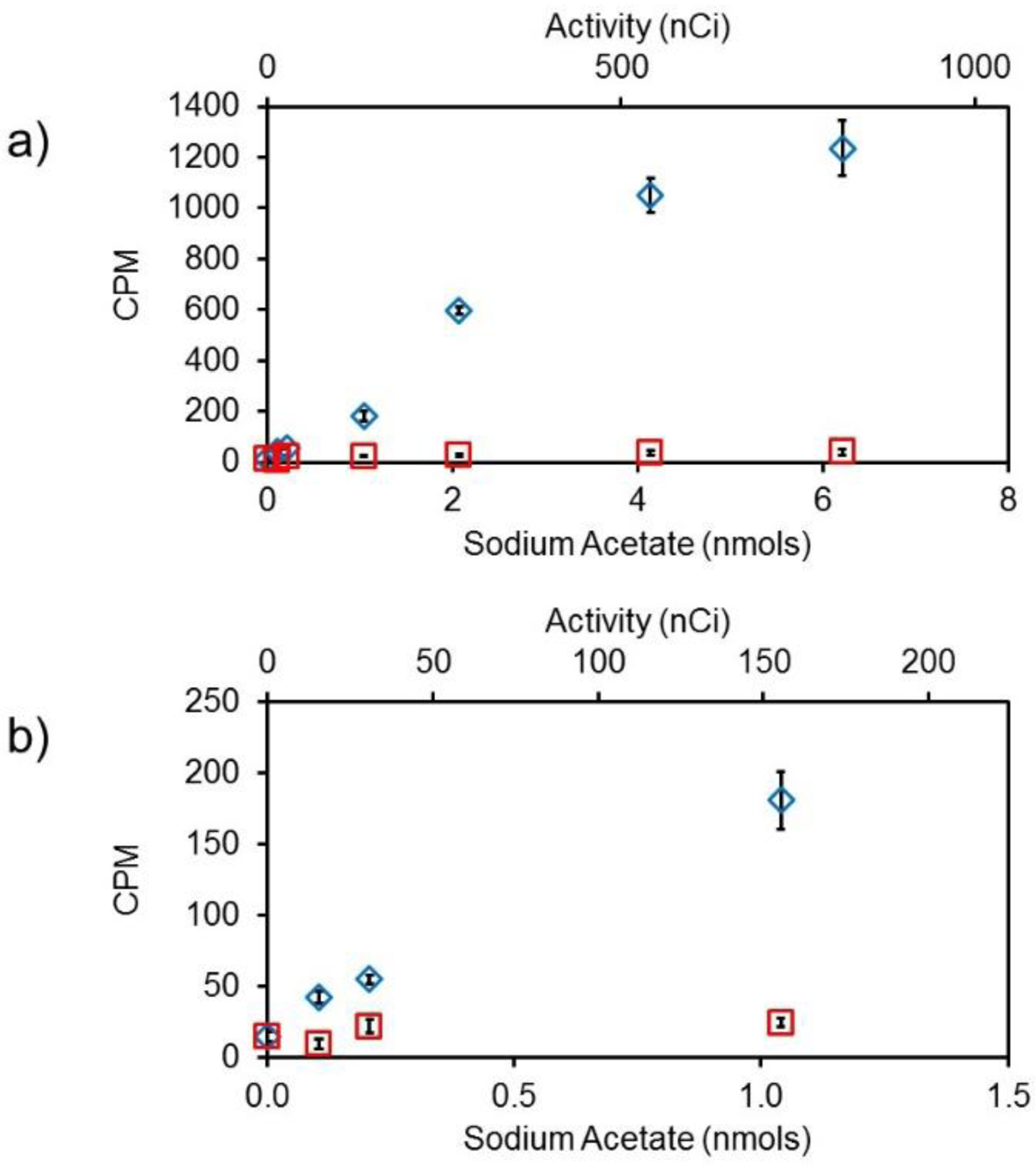

To validate the function of nanoSPA, 3H-sodium acetate was covalently attached to the nanoSPA particle surface to determine if signal due to β-particles emitted by bound 3H (proximity) could be distinguished from signal due to β-particles emitted by unbound 3H which has a longer mean distance from the nanoSPA core (non-proximity). Non-proximity derived signal, which represents the normal background signal for all SPA applications, must be significantly lower than proximity derived signals for useful SPA measurements. Figure 2 shows the non-proximity and proximity responses for nanoSPA upon addition of increasing 3H activity. The proximity signal was ca. 30× greater than the non-proximity signal at 6.2 nmol (930 nCi) of 3H. At lower activity, an enhancement greater than 4× was observed for 0.1 nmol (15.5 nCi) 3H activity (42 CPM vs 9.4 CPM). The limit of detection for this assay was 6.0 nCi 3H, corresponding to approximately 0.04 nmol, or 280 nM. While the ratio of proximity to non-proximity signals is dependent on several factors including nanoSPA concentration, analyte concentration, Emax, and specific activity, this experiment clearly demonstrates the feasibility of nanoSPA measurements that are analogous to those performed using slab-style SPA scintillators, such as microwell plates, with similar sensitivity.

Figure 2.

Proximity-dependent signal enhancement. a) Scintillation response of 3H-labeled sodium acetate (blue diamonds) covalently linked to nanoSPA particle surface compared to unlinked 3H-labeled sodium acetate in free solution (red squares). b) The same data expanded to show the scintillation response at low activities.

nanoSPA was then compared to SPA particles with diameters > 5μm, referred to as microSPA, which are commonly used for SPA measurements (Figure S-2, Supporting Information). A comparison of the scintillation response of nanoSPA and microSPA particles (Supporting Information) shows that while the large SPA particles demonstrate a ca. 3x greater absolute scintillation response (Figure S-3, Supporting Information), the net enhancement, determined from the ratio of proximity-derived signal to non-proximity-derived signal, is equivalent, if not better, for nanoSPA compared to microSPA at 0.5 μCi/mL (Figure S-3, Supporting Information). Though, on a per decay event basis, larger particles are expected to give a larger absolute signal due to the closer match to the β-particle path length and greater absorption of energy, nanoSPA provides similar enhancements, likely due to higher surface area available for binding and better dispersion of nanoSPA.49–51

Following the assessment of sensitivity, we prepared biotin-functionalized nanoSPA to demonstrate the specificity of the nanoSPA radioassay sensor platform. Briefly, nanoSPA particles with amine-functionalized silica shells were further modified with PEG6–9-dimethylchlorosilane with either 0 or 4% biotin-PEG-NHS ester (Mw = 3,000). nanoSPA particles were then used to measure 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin directly in pH 7.4 phosphate buffer. Figure 3 shows the response of nanoSPA particles as a function of increasing NeutrAvidin. When 3H-labeled sodium acetate was used as a non-proximity marker, the observed background was low, measuring ≤ 130 CPM at the highest 3H activity. The specificity was evaluated using PEG6–9-coated nanoSPA particles that contained or lacked PEG-biotin.

Figure 3.

Response of biotin-functionalized nanoSPA as a function of 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin (blue circles) compared to non-specific adsorption of 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin to nanoSPA lacking biotin (green triangles) and non-proximity effects of 3H-labeled sodium acetate added to biotinylated nanoSPA (red diamonds).

Upon addition of NeutrAvidin, the scintillation response for the biotinylated nanoSPA increased while the signal for nanoSPA lacking biotin remained equivalent to the non-proximity signal observed for biotin null particles. Amine-functionalized silica is susceptible to non-specific protein adsorption,52–54 thus addition of PEG to the nanoSPA surface served to minimize the signal due to non-specific adsorption. Compared to the non-proximity signal, an 8-fold increase in signal response was observed for non-optimized biotin-functionalized particles at 1.5 nmol NeutrAvidin, which is comparable to commercial microparticle SPA assays, that exhibit 3× to 15× enhancement.19–20, 23–24, 27 Based on these data, the limit of detection for this assay is 9 pmol of 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin which is more than 10 times lower than non-specific adsorption of 3H-labeled NeutrAvidin. These results demonstrate that functionalized nanoSPA can be used to selectively detect 3H-labeled protein.

The NeutrAvidin used in these experiments was labeled using EDAC/NHS coupling of 3H-labeled sodium acetate, demonstrating that nanoSPA could be used for protein analytes (e.g. project-specific mutants) for which there is no commercially available 3H-labeled material. In addition, the data shown in Figure 3 demonstrate that nanoSPA can be used to obtain sub-nmol detection limits, though this may be improved by increasing the 3H-labeling efficiency, which for these experiments was 20%. While many protein labeling protocols for reactive fluorescein and rhodamine tags recommend limiting reagent concentrations to yield 2–6 fluorophores per protein to prevent quenching,55–57 3H can incorporated into proteins using chemical or metabolic labeling techniques without concern of quenching.58–60 In addition, small molecules can be synthesized with several 3H per molecule, making greater sensitivity possible for radioassays.

Finally, nanoSPA was evaluated for specificity using a DNA-binding interaction. nanoSPA particles were functionalized with a 30-base ssDNA oligomer to which the complimentary, 3H-labeled strand (57 nCi/nmol), was hybridized. As expected, the measured signal increased with increasing 3H-labeled complementary strand due to hybridization with the ssDNA oligomer immobilized on the nanoSPA surface (Figure 4a). The sigmoidal shape of the curve observed in Figure 4a may be due to both a decreased probability of binding during the set annealing time at low ssDNA (less than 1 nmol) concentration and surface saturation at high ssDNA concentrations (5 nmol and greater), as only 8 nmol of ssDNA was used for nanoSPA functionalization.

Figure 4.

nanoSPA response to DNA hybridization. a) ssDNA-functionalized (blue circles) and unfunctionalized nanoSPA particles (red squares) were incubated with increasing concentrations of 3H-labeled complementary ssDNA oligomers. b) Competitive radioassay for 3H-labeled DNA. ssDNA-functionalized nanoSPA were incubated in the presence of 6 nmol 3H-labeled complementary ssDNA with addition of the indicated concentration of 30-base unlabeled complementary (orange circles), 4-base mismatch (gray triangles) and random (violet diamonds) DNA sequences. c) Percent signal saturation for the competitive radioassay at 6 nmol ssDNA where *and ** represent p < 0.005 and p < 0.001, respectively, in a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

The utility and selectivity of nanoSPA was further evaluated by performing a competitive binding assay in which unlabeled ssDNA was added to nanoSPA previously saturated with 6 nmol of 3H-labeled complementary ssDNA. The nanoSPA samples were then subjected to the same heating and cooling cycles used for hybridization of the 3H-labeled complementary ssDNA strand. Under these conditions, the unlabeled complementary ssDNA was expected to replace a proportional amount of 3H-labeled complementary ssDNA at the nanoSPA surface. As predicted, the measured signal at nanoSPA saturation with 3H-labeled ssDNA complementary strand decreases with increasing unlabeled complementary ssDNA by up to 64% over the range from 0 to 6 nmol, but only by 36% when treated with an unlabeled ssDNA with 4 mismatched bases. Furthermore, the saturated nanoSPA signal decreased by only 16% when treated with an unlabeled random-sequence 30-base ssDNA oligomer. The minimum 3H-labeled complementary strand detected was 1 nmol. The detection limit for the competitive assay is estimated to be 1.4 nmol of unlabeled complementary ssDNA, with ca. 2× and 4× selectivity for the complementary versus 4-base mismatch and the complementary versus random sequences respectively. Despite the similarity between the complementary and the 4-base mismatch oligomers, ssDNA functionalized nanoSPA can be used to differentiate between the two sequences. Overall, data from these three model assays support the selectivity of the nanoSPA platform and demonstrate a wide potential applicability for homogenous radioassays, with signal enhancements equivalent to existing microparticle SPA platforms but with substantially improved dispersability.

CONCLUSIONS

nanoSPA particles provide selectivity and enhanced sensitivity for radiolabeled analytes in an easily dispersible and readily functionalized nanoparticle geometry. Selective and sensitive detection can be performed directly in aqueous samples without the need for LSC which may lead to denaturation and other deleterious processes and thus hinder the analysis. As such, nanoSPA can potentially be used for temporally resolved measurements in biological samples where sample volume is limited and/or where larger particles are more likely to settle during the time course of the measurment. While the absolute signal for nanoSPA particle is lower than that observed for similarly prepared microparticles due to the smaller signal generation pathlength in nanoSPA, the signal enhancement for proximity versus non-proximity signals were comparable between the two particle size scales. Furthermore, the silica surface provides a more easily modified substrate for attachment of recognition elements compared to common polymer microSPA beads enabling versatile, separation-free analysis using SPA. Due to the small diameter of nanoSPA and the previously demonstrated bioinert nature of silica nanoparticles,61–64 future applications of nanoSPA may prove useful for application to complex biological systems that cannot be assessed using current radioisotope detection technologies..

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation under grant number 1807343, the National Institutes of Health via the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering under grant number R21EB019133 and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences under grant number 1R01GM116946. The transmission electron microscope used in this study was purchased by the Life Science North Imaging Facility at the University of Arizona with funding from the National Institutes of Health, under grant number 1S10OD011981-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsors.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aubin J, Autofluorescence of Viable Cultured Mammalian Cells. J. Histochem. Cytochem 1979, 27, 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson H; Baechi T; Hoechl M; Richter C, Autofluorescence of Living Cells. J. Microsc 1998, 191, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monici M, Cell and Tissue Autofluorescence Research and Diagnostic Applications. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev 2005, 11, 227–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermeir M; Vanstapel F; Blanckaert N, Radioassay of UDP-Glucuronyltransferase-Catalyzed Formation of Bilirubin Monoglucuronides and Bilirubin Diglucuronide in Liver Microsomes. Biochem. J 1984, 223, 455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rohatgi P; Ryan J, Simple Radioassay for Measuring Serum Activity of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme in Sarcoidosis. Chest 1980, 78, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yalow R, Radioimmunoassay. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Bioeng 1980, 9, 327–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlett A; Lloyd-Jones J; Rance M; Flockhart I; Dockray G; Bennett M; Moore R, The Radioimmunoassay of Buprenorphine. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol 1980, 18, 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis. 3rd ed.; L’Annunziata M Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flammersfeld A, Eine Beziehung Zwischen Energie Unde Reichweite Fur Beta-Strahlen Kleiner Und Mittlerer Energie. Naturewissenschaften 1947, 33, 280–281. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knop G; Paul W, Interactions of Electrons and α-Particles with Matter In Alpha-, Beta-, and Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy, 1 ed.; Siegbahn K, Ed. North-Holland Publishing Company: New York, 1968; pp 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks F, Development of Organic Scintillators. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 1979, 162, 477–505. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutherford E; Chadwick J; Ellis C, Radiations from Radioactive Substances. Cambridge University Press: London, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derenzo S; Weber M; Bourret-Courchesne E; Klintenberg M, The Quest for the Ideal Inorganic Scintillator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 2003, 505, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeVol T; Egorov O; Roane J; Paulanova A; Grate J, Extractive Scintillating Resin for 99Tc Quantification in Aqueous Solutions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem 2001, 249, 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egorov O.; Fiskum S; O’Hara M; Grate J, Radionuclide Sensors Based on Chemically Selective Scintillating Microspheres: Renewable Column Sensor for Analysis of 99Tc in Water. Anal. Chem 1999, 71, 5420–5429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeVol T; Roane J; Williamson J; Duffey J; Harvey J, Development of Scintillation Extraction Media for Separation and Measurement of Charged-Particle-Emitting Radionuclide in Aqueous Solutions. Radioact. Radiochem 2000, 11, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roane J; DeVol T, Simultaneous Separation and Detection of Actinides in Acid Solutions Using an Extractive Scintillating Resin. Anal. Chem 2002, 74, 5629–5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart H; Greenwald E, Scintillation Proximity Assay (SPA)- a New Method of Immunoassay Direct and Inhibition Mode Detection with Human Albuminand Rabbit Antihuman Albumin. Mol. Immunol 1979, 16, 265–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Udenfriend S; Gerber L; Brink L; Spector S, Scinitillation Proximity Radioimmunoassay Utilizing 125I-Labeled Ligands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 1985, 82, 8672–8676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heise C; Sullivan S; Crowe P, Scintillation Proximity Assay as a High-Throughput Method to Indentify Slowly Dissociating Nonpeptide Ligand Binding to the GnRH Receptor. J. Biomol. Screen 2007, 12, 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alderton W; Boyhan A; Lowe P, Nitroarginine and Tetrahydrobiopterin Binding to the Haem Domain of Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase Using a Scintillation Proximity Assay. Biochem. J 1998, 332, 195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia L; de Vries H; IJzerman A; Heitman L, Scintillation Proximity Assay (SPA) as a New Approach to Determine a Ligand’s Kinetic Profile. A Case in Point for the Adenosine A1 Receptor. Purinergic Signal. 2016, 12, 115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun S; Almaden J; Carlson T; Barker J; Gehring M, Assay Development and Data Analysis of Receptor-Ligand Binding Based on Scintillation Proximity Assay. Metab. Eng 2005, 7, 38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nare B; Allocco J; Kuningas R; Galuska S; Myers R; Bednarek M; Schmatz D, Devlopment of a Scintillation Proximity Assay for Histone Deacetylase Using a Biotinylated Peptide Derived from Histone-H4. Anal. Biochem 1999, 267, 390–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu S; Liu B, Application of Scintillation Proximity Assay in Drug Discovery. Biodrugs 2005, 19, 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosworth N; Towers P, Scintillation Proximity Assay. Nature 1989, 341, 167–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hart H; Greenwald E, Scintillation Proximity Assay of Antigen-Antibody Binding Kinetics: Concise Communication. J. Nucl. Med 1979, 20, 1062–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udenfriend S; Gerber L; Nelson N, Scintillation Proximity Assay: A Sensitive and Continuous Isotopic Method for Monitoring Ligand/Receptor and Antigen/Antibody Interactions. Anal. Biochem 1987, 161, 494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook N, Scintillation Proximity Assay: A Versatile High-Throughput Screening Technology. Reviews 1996, 1, 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brandish P; Hill L; Zheng W; Scolnick E, Scintillation Proximity Assay of Inositol Phosphates in Cell Extracts: High-Thoughput Measurement of G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Activition. Anal. Biochem 2003, 313, 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J; Hartman D; Bostwick J, An Immobilized Metal Ion Affinity Adosrption and Scintillation Proximity Assay for Receptor-Stimulated Phosphoinositide Hydrolysis. Anal. Biochem 2003, 318, 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green E; Coleman J; Gouaux E, Thermostabilization of the Human Serotonin Transporter in an Antidepressant-Bound Conformation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navratna V; Tosh D; Jacobson K; Gouaux E, Thermostabilization and Purification of the Human Dopamine Transporter (Hdat) in an Inhibitor and Allosteric Bound Conformation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glickman J; Schmid A; Ferrand S, Scintillation Proximity Assays in High Throughput Screening. Assay and Drug Dev. Technol 2008, 6, 433–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janczak C; Calderon I; Mokhtari Z; Aspinwall C, Polystyrene-Core Silica-Shell Scintillant Nanoparticles for Low-Energy Radionuclide Quantification in Aqueous Media. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 4953–4960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Destruel P; Taufer M; D’Ambrosio C; Da Via C; Fabre J; Kirkby J; Leutz H, A New Plastic Scintillator with Large Stokes Shift. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 1989, 276, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barashkova I; Ivanov V, The Comparison of Radiation and Photochemical Stability of Luminophores in Polystyrene Scintillators. Polym. Degrad. Stab 1998, 60, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niese S, The Discovery of Organic Solid and Liquid Scintillators by H. Kallman and L. Hereforth 50 Years Ago. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem 1999, 241, 499–501. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J; Gomez I; Sitterle V; Meredith J, Dye-Labeled Polystyrene Latex Microspheres Prepared Via a Combined Swelling-Diffusion Technique. J. Colloid Sci 2011, 363, 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Behnke T, Würth C; Hoffmann K; Hübner M; Panne U; Resch-Genger U, Encapsulation of Hydrophobic Dyes in Polystyrene Micro and Nanoparticles Via Swelling Procedures. J. Fluoresc 2011, 21, 937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Q; Han Y; Wang W; Zhang L; Chang J, Preparation of Fluorescent Polystyrene Microspheres by Gradual Solvent Evaporation Method. Eur. Polymer J 2009, 45, 550–556. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu Y; McLellan J; Xia Y, Synthesis and Crystallization of Hybrid Sperical Colloids Composed of Polystyrene Cores and Silica Shells. Langmuir 2004, 20, 3464–3470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Derjaguin B, Main Factors Affecting the Stability of Colloids. Pure and Appl. Chem 1976, 48, 387–392. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fritz G; Schadler V; Willenbacher N; Wagner N, Electrosteric Stabilization of Colloidal Dispersions. Langmuir 2002, 18, 6381–6390. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi M; Juillerat F; Galletto P; Bowen P; Borkovec M, Aggregation and Charging of Colloidal Silica Particles: Effect of Particle Size. Langmuir 2005, 21, 5761–5769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ortega-Vinuesa J; Martin-Rodriguez A; Hidalgo-Alvarez R, Colloidal Stability of Polymer Colloids with Different Interfacial Properties: Mechanisms. J. Colloid and Interface Sci 1996, 184, 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liz-Marzán L; Giersig M; Mulvaney P, Synthesis of Nanosized Gold-Silica Core-Shell Particles. Langmuir 1996, 12, 4329–4335. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye J; Van de Broek B; De Palma R; Libaers W; Clays K; Roy W; Borghs G; Maes G, Surface Morphology Changes on Silica-Coated Gold Colloids. Colloids Surf., A 2008, 322, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu D; Jay M, Aqueous Polystyrene-Fluor Nanosuspensions for Quantifying α and β- Radiation. Nanotechnology 2007, 18, 225502–225508. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tarancón A; Garcia J; Rauret G, Mixed Waste Reduction in Radioactivity Determination by Using Plastic Scintillators. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 463, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tarancón A; Garcia J; Rauret G, Reusability of Plastic Scintillators Used in Beta Emitter Activity Determination. Appl. Radiat. Isot 2003, 59, 373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larsericsdotter H; Oscarsson S; Buijs J, Thermodynamic Analysis of Proteins Adsorbed on Silica Particles: Electrostatic Effects. J. Colloid and Interface Sci 2001, 237, 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nezu T; Masuyama T; Sasaki K; Saitoh S; Taira M; Araki Y, Effect of PH and Addition of Salt on the Adsorption of Lysozyme on Gold, Silica, and Titania Surfaces. Dent. Mater. J 2008, 27, 573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meissner J; Prause A; Bharti B; Findenegg G, Characterization of Protein Adsorption onto Silica Nanoparticles: Influence of pH and Ionic Strength. Colloid Polym. Sci 2015, 293, 3381–3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banks P; Paquette D, Comparison of Three Common Amine Reactive Fluorescent Probes Used for Conjugation to Biomolecules by Capillary Zone Electrophoresis. Bioconjugate Chem. 1995, 6, 447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brinkley M, A Brief Survey of Methods for Preparing Protein Conjugates with Dyes, Haptens and Cross-Linking Reagents. Bioconjugate Chem. 1992, 3, 2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holmes K; Lantz L, Protein Labeling with Fluorescent Probes. In Methods in Cell Biology 3rd ed.; Darzynkiewicz Z; Crissman HA; Robinson JP, Eds. Academic Press: 2001; Vol. 63, pp 185–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kelman Z; Naktinis V; O’Donnell M, Radiolabeling of Proteins for Biochemical Studies. Methods in Enzymol. 1995, 262, 430–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schumacher T; Tsomides T, In Vitro Radiolabeling of Peptides and Proteins. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci 1995, 00, 3.3.1–3.3.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Montelaro R: Rueckert R, Radiolabing of Proteins and Viruses in Vitro by Acetylation with Radioactive Acetic Anhydride. J. Biol. Chem 1975, 250, 1413–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li Q; Hu H; Jiang L; Zou Y; Duan J; Sun Z, Cytotoxicity and Autophagy Dysfunction Induced by Different Sizes of Silica Particles in Human Bronchial Epithelial Beas-2b Cells. Toxicol. Res 2016, 5, 1216–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Y; Sun L; Jin M; Du Z; Liu X; Guo C; Li Y; Huang P, Size-Dependent Cytotoxicity of Amorphous Silica Nanoparticles in Human Hepatoma hepG2 Cells. Toxicology in Vitro 2011, 25, 1343–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McCarthy J; Inkielewicz-Stępniak I; Corbalan JJ; Radomski M, Mechanisms of Toxicity of Amorphous Silica Nanoparticles on Human Lung Submucosal Cells in Vitro: Protective Effects of Fisetin. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2012, 25, 2227–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Napierska D; Thomassen L; Rabolli V; Lison D; Gonzalez L; Kirsch-Volders M; Martens J; Hoet P, Size-Dependent Cytotoxicity of Monodisperse Silica Nanoparticles in Human Endothelial Cells. Small 2009, 5, 846–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.