Abstract

Background:

Suicides are among the leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults worldwide, including India. Suicide attempts are about 20 times more common than completed suicides. Teenagers and youth who attempt suicide belong to a heterogeneous group. Various biological and psychosocial factors, including family factors, contribute to such behavior. Quality of family functioning and relationships may act as an important contextual factor in deciding suicidal behavior. Hence, this study was done to explore the family factors contributing to suicide attempts.

Methods:

Qualitative exploratory study design and purposive sampling were used. Data were collected from 22 adolescents and young adults using an in-depth interview method. All audio recordings were transcribed in Malayalam, and then translated to English. Codes were developed using the qualitative data analysis software. Thematic analysis was done. Themes and relationships were identified and synthesized to a framework that represents the summary of the data.

Results:

Most of the participants perceived the home environment as hostile. Problems within the family included parental conflicts and separation, conflict with a sibling or other members of the family, and marital disharmony. Most of them perceived low family support. Socioeconomic factors such as financial issues, superstitious beliefs, disturbing neighborhoods, interpersonal issues, and the stigma of having a mental illness, in a family member, were also noted.

Conclusion:

Hostile family environment, faulty interactions between family members, and lack of perceived family support may contribute to suicidal behavior among adolescents and young adults. Hence, it is imperative to consider these factors while treating them or planning any suicide prevention program for them.

Keywords: Suicide attempts, adolescent, young adults, family factors

Key Messages:

Emotional distress due to faulty interactions with family members and other socioeconomic factors within the family may precipitate suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults. Early identification and family level intervention may help prevent such behavior

Globally, suicide is one of the leading causes of death and considered a public health and social issue. According to the World Health Organization, almost 800,000 people die from suicide every year; this roughly corresponds to one death every 40 seconds. These figures do not include suicide attempts, which can be more than 20 times frequent than completed acts. Worldwide, suicide is the second leading cause of death among those aged 15–29 years.1 India’s contribution to global suicide rates has increased over the years 1990–2016.2

According to the National Crime Records Bureau, the official agency responsible for suicide data collection in India, more than one lakh (139,123) persons committed suicide in the year 2019, and the National average was 10.4 per one lakh population. Kerala recorded a rate of 24.3 per one lakh population, which is more than twice the national average. Around 35.1 percent of suicide victims were youths in the age group of 18–30 years, and this was the main age group that committed suicide.3 In India, for suicide deaths at ages ≥15 years, Patel et al. estimated that 56% of women and 40% of men belong to the age group 15–29 years.4 Clinical studies have shown that the youth who attempt suicides belong to a heterogenous group in terms of gender, intent and lethality of attempt, impulsivity, previous attempts, presence of psychiatric disorders, family history of mental illness/suicide, and various other social factors.5–7

Suicidal behavior is a complex behavior. Its causes consists of a constellation of components that act together and include a variety of biological, psychological, and social factors, including familial and other contextual factors.6–9 Though suicide is regarded as a public health problem, it is a very personal decision that the individual makes. Hence, it is vital to understand the personal distress and the contextual factors. Perceived family functioning and relationships are important contextual factors deciding suicidal behavior among adolescents and young adults.10 Perceived criticisms from parents, invalidation from family members, and low levels of perceived family support may contribute to such behavior.11–13 Though many family factors have been identified, qualitative research is scanty in this area.

In Indian culture, family plays an important role in an individual’s life experiences and decisions. Though it largely acts as a protective factor providing vital support for the individual, sometimes it may act as a risk factor in precipitating suicide attempts.

Hence, a qualitative study was planned to explore the individual experiences and family factors that contribute to suicide attempts so that this will help us understand this complex phenomenon. It will also provide the clinician with a deeper understanding of the individual’s distress and help in making appropriate interventions at the family level. This study is part of a larger study conducted among adolescents and young adults in a tertiary care center in South India to assess the predictors of attempted suicide among them.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting

The study was conducted in the in-patient wards of a tertiary care medical hospital. The study was conducted in 2014, after clearance from the Human Ethics Committee.

Study Design

Qualitative exploratory study14 to explore the individual experiences and perceptions regarding the family factors associated with the suicide attempt among adolescents and young adults.

Sample Selection

Inclusion criteria: Participants were selected from adolescents and young adults (13–29 years of age) admitted with a suicide attempt. They were part of the larger quantitative study that looks at the predictors of attempted suicide among adolescents and young adults. Purposive sampling was used, allowing maximum variation in age, sex, geographical location, level of education, income, family history of suicide, and intent of the present attempt.

Exclusion criteria: Those with serious medical complications related to the attempt, those with known mental illness, and those not willing to give consent were excluded.

Data were collected from 22 subjects. After each interview, data analysis was done completely, and a decision about the subsequent interview was made by constant comparison method. This process continued until data saturation was reached, with no new themes coming from subsequent interviews.

Method

Patients admitted after suicide attempts and meeting the selection criteria were approached. In-depth face-to-face interviews were done after they became medically stable. Most of them were interviewed within one week of the attempt. Each interview lasted about 30 minutes and was conducted in Malayalam, the regional language. Sociodemographic data and relevant clinical details, such as family history and suicide intent, were collected. Suicide intent was assessed clinically, based on the person’s response to the questions on whether he/she wanted to die, the method of attempt, and the circumstances (whether rescue measures were taken or not).

Interviewer: The first author, a consultant lady psychiatrist with an MD degree in psychiatry, who has attended training workshops on qualitative research techniques, conducted the interviews. The interviewer has an interest in suicidology and public health and has been working with suicidal patients for the last 10 years. Possible assumptions/bias regarding the study topic was addressed by a constant discussion with other members of the team.

Relationship with participants: Rapport was established before the in-depth interviews. Details regarding the research and the interviewer were explained to the participants, and the participant information sheet was provided. Two patients were excluded as they did not want to participate. Informed consent was taken from young adults who agreed to participate in the study. Informed assent was taken from adolescent participants, and informed consent from their parents was also taken for the study. Privacy and confidentiality were ensured at all stages.

Data collection: Semistructured format was used, with open-ended questions initially, followed by questions focusing on the participant’s experiences and perception about the family environment and interaction, communication between the family members, decision-making and problem-solving within the families, and their socioeconomic background. The semistructured interview schedule was prepared by operationalizing the previous knowledge about family factors contributing to attempted suicide among adolescents and young adults. This preliminary interview schedule was pilot tested in four patients to confirm the coverage and relevance. Modifications were made accordingly, and the final interview schedule was formed. Probes and prompts were used when needed. An audio recording of the interviews was done. Field notes were made during and after the interview. All audio recordings were transcribed verbatim in Malayalam and translated to English. The transcripts were shown to six randomly selected participants for comments and corrections.

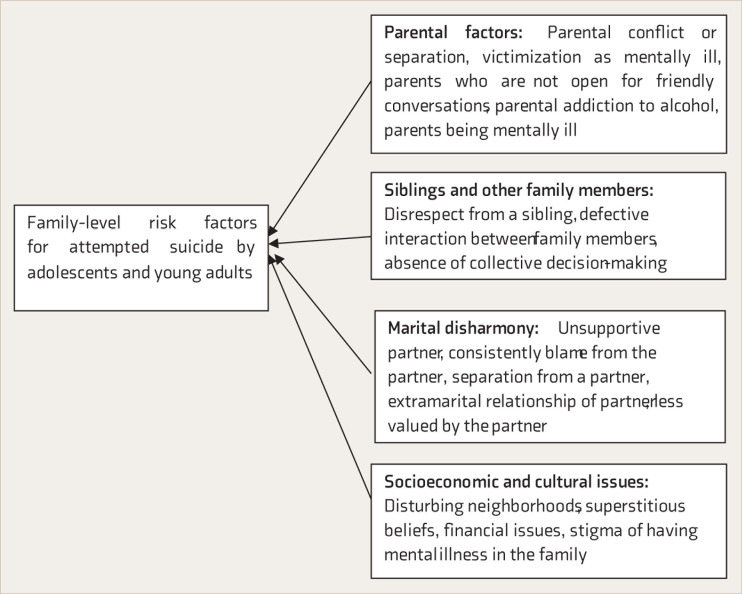

Figure 1. Framework Depicting Risk Factors.

Data Analysis

After each interview, data were entered and analyzed completely using the Web Embedding Fonts Tool Qualitative Data Analysis (Weft QDA 1.0.1)software. The decision regarding the next interview was made based on this. Data collection ended when data saturation was reached with no new themes coming from subsequent interviews.

Two data coders, familiar with the process, independently did the data analysis. After the first three interviews, they discussed the codes and revised when needed. This process of discussion and revision was done in between, using random transcripts. Participant feedback was taken in between.

From the available narratives, codes were developed using Weft QDA 1.0.1 software. Thematic analysis was done.15 Themes and relationships were identified. Themes were derived inductively from the data, using the process of open coding, creating categories and finding the inner meaning. Data were synthesized to form a framework that represents the summary of the data (Figure1).

Results

A total of 22 participants were interviewed. The characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. The perceived home environment was hostile for most of the study participants. This was due to many factors within the family, like parental conflicts, conflict with a sibling or other members of family, unsupportive spouse, or difference of opinions between the family members living in the same home. Socioeconomic and cultural factors, like financial issues, superstitious beliefs, the stigma of having a family member with mental illness, and disturbing neighborhoods also contributed to suicidal behavior. Themes, subthemes, and illustrative quotes are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n = 22)

| Characteristics |

Adolescents (13–19 Years) n = 7 |

Young Adults (20–29 Years) n = 15 |

|||

| Frequency | Percentage (%) |

Frequency | Percentage (%) |

||

| Sex |

Male | 3 | 13.6 | 8 | 36.4 |

| Female | 4 | 18.2 | 7 | 31.8 | |

| Marital status |

Married | 0 | 0 | 6 | 27.3 |

| Single | 7 | 31.8 | 9 | 40.9 | |

| Geographical location |

Urban | 3 | 13.6 | 4 | 18.2 |

| Semi-urban | 0 | 0 | 3 | 13.6 | |

| Rural | 4 | 18.2 | 8 | 36.4 | |

| Education |

School | 5 | 22.7 | 9 | 40.9 |

| College | 1 | 4.5 | 6 | 27.3 | |

| Drop out | 1 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Family history of mental illness/suicide | Present | 4 | 18.2 | 10 | 45.5 |

| Absent | 3 | 13.6 | 5 | 22.7 | |

| Suicide intent | Low | 5 | 22.7 | 9 | 40.9 |

| High | 2 | 9.1 | 6 | 27.3 | |

Table 2.

Summary of Study Findings

| Theme: Parental Issues | ||

| S. No. | Subthemesa | Quotesb |

| 1 | Parental conflict (4) | “Quarrels happen at home for no reason…. They last 5–6 days. Sometimes father speaks ill of our grandmother, which my mother dislikes.” (Participant number 12 [P12]) |

| 2 | Parental separation (2) | I felt that if Vaapachi (father) were around, he would have understood me. But he had left us when I was seven years old because of Ummachi’s bad temper and arguing nature. I did not have anywhere else to go. So I thought I would end it all….” (P15) |

| 3 | Victimization as mentally ill (2) | “But, in between, when papa (father) told that it is because of me papa’s family went away, he lost his house, and because of me he had to spend a lot of money, I felt very sad. Initially, amma (mother) used to tell such things while she was angry. At times, she tells me that I am mad. After listening to this repeatedly, I feel bad. Usually, I try to console myself that amma said that out of anger. When I heard the same from papa’s mouth all of a sudden, I could not control, I felt angry and wanted to kill myself. Nobody loves me.” (P8) |

| 4 | Parents who are not open for friendly conversations (5) | “Ummachi (mother) loses her temper very quickly, so I was waiting for her to be in a good mood to tell that I received the mobile phone from my boyfriend. But she found it under my pillow and she got very angry and asked me to leave the house. I did not know what to do. I could not tell her the truth at that time….” (P15) |

| 5 | Parental addiction to alcohol (3) | “I knew things would go wrong that day because father was drunk…. He speaks bad things about all of us when drunk.” (P5) |

| 6 | Parents being mentally ill (1) | “Always scolding and fighting, maybe because of her illness. I was tired of living in this situation and I thought at least I will go.” (P6) |

| Theme: Problems with Siblings and Other Family Members | ||

| 1 | Disrespect from a sibling (3) | “I and my younger sister…we hate each other. She doesn’t give me the respect due to an elder sister. She respects all others and calls them “chichi” (elder sister) but doesn’t call me that. We quarreled that day…. And she told me ‘Why don’t you go and die?’ I thought I would just show her that.” (P19) |

| 2 | Defective interaction between family members (6) | “Ours is a joint family. There’s no peace at home. Others keep arguing and fighting, to prove they’re right. The worst is between my mother and her brother. They never stop….” (P7) |

| 3 | Absence of collective decision making (4) | “Usually nobody asks for my decision at home…even for my marriage, it was that way.” (P3) |

| Theme: Marital Disharmony | ||

| 1 | Unsupportive spouse (5) | “She’s supposed to support me…. She’s my wife…. But she’s not willing to do so. She doesn’t even listen.” (P17) |

| 2 | Consistently blaming partner (4) | “We bought this house two years back, which led to all these debts. My wife forced me to borrow and buy it. Now, everything is on my head. She keeps blaming me every day. I’m fed up with this.” (P4) |

| 3 | Separation from a partner (2) | “…wish we were closer. He comes home for leave only once in three years.” (P10) |

| 4 | Extramarital relationship of partner (2) | “I saw their chat on his mobile. When I confronted, he denied but is still continuing the relationship.” (P20) |

| 5 | Less valued by the spouse (4) | “My husband neglects me and makes use of every chance to insult me.” (P1) |

| 6 | Insecurity about children (1) | “My children are small girls. My husband invites his friends home and drinks. I am afraid whether his friends will abuse my children. I am scared and so I don’t leave home.” (P20) |

| Theme: Socioeconomic and Cultural Issues | ||

| 1 | Financial issues (5) |

“Once the money is lost, everything is lost. Now I have no business, no friends, no support from family. No point in living this way.” (P9) |

| 2 | Superstitious beliefs (3) | “They do black magic because they are jealous of our fortune and development.” (P11) |

| 3 | Disturbing neighborhoods (1) | “We stay in a locality where there are lots of drunkards. They get drunk, come back home, and call out bad words. Sometimes, the police have to intervene.” (P11) |

| 4 | Stigma of having mental illness in the family (1) | “My uncle is mentally ill; he gets admitted in that psychiatry hospital and our neighbors call him mad. I don’t want to be called that.” (P16) |

aNumber within the bracket shows the frequency with which it was reported. bSource of illustrative quote, as participant number, P within Parentheses.

Parental Issues

Parental factors included parental conflicts or separation, victimization as mentally ill, parents who are not open for friendly conversations, paternal addiction to alcohol, and a parent being mentally ill.

Parental conflicts disturbing the home environment was reported by many participants. Narrative from a young lady, aged 20 years (Participant number 12 [P12]], about her family environment is included in Table 2. Another participant, a 15-year-old girl [P8], expressed that her mother frequently called her “mad,” and she was used to it. But, when her father said the same for the first time, she could not control her thoughts (Table 2). The critical comments from her parents (being addressed as “mad”) caused sadness, impulsive anger, and, finally, suicidal thoughts. Her perception, “nobody loves me,” was echoed by many of the participants, which makes it clear that the dynamic interaction between family factors and the individual factors (how the individual perceives, interprets, and reacts) are important in determining the suicidal attempt. Among adolescents, a teenage girl (16 years, P15) had a relationship with a boy that raised issues at home, leading to suicidal attempt. Although she was open to her mother, her mother often become angry and critical towards her, and this prevented her from admitting the truth that she had received a mobile phone from her boyfriend. Her mother’s critical comments made her feel helpless, and the perceived lack of family support led to the attempt. Illustrative quotes are included in Table 2. Another participant, a 26-year-old lady (P6), had a family history of mental illness in her mother who was taking treatment from the same hospital. The participant eloped with a man whom she married later on, but then, after delivering a female baby, she came to know that he is in a relationship with another woman. This made her leave him and stay with her mentally ill mother and grandmother who always fight with each other. She had never enjoyed parental affection and now feels that she and her child are a burden to her ill mother. Hostile family environment, lack of perceived family support, and probably, her inability to handle the stressful situation may have led to the attempt (Table 2).

Problems with Siblings and Other Family Members

Many of them had difficulty interacting with siblings and others in the family. There was an adolescent girl, 14 years old (P19), who complained about her younger sister. She was talking of sibling rivalry, which led to disrespect, miscommunication, and the suicide attempt (Table 2).

Family dysfunction owing to frequent quarrels, poor communication, and lack of collective decision-making was evident from some excerpts. Illustrative quotes from a 16-year-old boy (P7) and 20-year-old young lady (P3) are given in Table 2.

Marital Disharmony

Marital dysfunction due to alcohol abuse of the spouse, insecurity about children, or the spouse being manipulative and unsupportive was evident among young adults. Consistent blaming by the partner, feeling less valued by the partner and separation from a partner were also observed in young adults with marital disharmony (Table 2).

Socioeconomic and Cultural Issues

Financial issues, superstitious beliefs, disturbing neighborhoods, and the stigma of having a mental health issue, in a family member, were also noted.

Families of many of them have bank loans and debts, which contributed to conflicts and dissatisfaction within the family. One of the participants, a 26-year-old male (P9), who had sustained a failure in business, felt helpless and suicidal when the financial resources were lost (Table 2) Another participant (18-year-old boy, P11) was consistently complaining about the neighborhoods as disturbing. Disturbances were caused by drunkards, the filthy language used by neighbors, and frequent interference by police. He also feels that these neighbors cause all their misfortunes through black magic (Table 2). The stigma of having a mental illness in a family member was evident from few excerpts. Appropriate quote from a 14-year-old boy is included in Table 2. Among the few who feel that their home was peaceful, both their parents were employed, and in most of the cases, it was their father who was the decision-maker. In other cases, it was the mother or own spouse who was the decision-maker. There was only one study subject who mentioned that decisions were taken by both parents. Except in a couple of instances where the family members collectively solved the problems, it was the mother who used to try to solve the problems within the family.

Discussion

Our study looked into the family context of adolescents and young adults belonging to the age group of 13–29 years. Family-level factors like a negative relationship with either or both the parents, family discord, whether the parents are living together or not, parental substance abuse, parental psychiatric disorder, and singleparent households are proven factors for suicidal risk among adolescents and young adults across the globe.5,16 Female gender, not attending school or college, lack of independent decision-making, physical abuse at home, psychological distress, and probable common mental disorders were associated with suicidal behavior in Indian youth.17,18

The decision to attempt suicide is a highly personal one, largely influenced by the individual’s perception of his/her environment, relationships, and sociocultural milieu.19 Studies have shown that perceived family factors such as hostile family environment, critical comments and invalidation from parents, and lack of emotional support from family members influence suicidal behavior among adolescents and young adults.10–13 All these family-level risk factors emerged in this study as well.

Though nuclear families have increased, Indian culture still holds the tradition of joint families. An interesting finding that came from this study was that adolescents and young adults are at risk when cordial relationships and integration are absent between members of a joint family. This appears to limit and complicate the information-sharing space available for adolescents and young adults and, thus, results in a lack of collective decision-making and a problem-solving environment at home.

Other factors affecting adolescents and young adults, as found in the literature, are socioeconomic status or financial loss, education, relationships, status within the family, childhood adversities, a recent change in family roles, infertility, and family stability.20,21 In this study, young adult men attempted suicide due to factors like socioeconomic status and status in the family, whereas young adult women were more concerned about family roles and stability. As per the strain theory of suicide, sources of psychological strain are differential value conflicts, discrepancies between aspirations and reality, relative deprivation, and lack of coping skills. It is safe to assume that young adults would have experienced more sources of a psychological strain than adolescents.22

Parenting styles influence suicidal behavior. Studies have shown that “affectionless control,” yielding to low levels of emotional warmth and high levels of parental control or overprotection, is associated with a threefold increase in the risk of suicide attempts.23

It is widely acknowledged that the stigma associated with mental health issues prevents people from disclosing their problems to others.24 This was evident from this study, as there were subjects who had a family history of mental illness. These family members did not receive proper treatment and follow-up care, and this might have led to inadequate family support in those who attempted suicide, when compared to others.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the study are that the in-depth interviews were conducted by a consultant psychiatrist, ensuring privacy, confidentiality, comfort, and support to the patient. Purposive sampling helped to select persons with diverse sociodemographic and clinical variables. Credibility was ensured by prolonged engagement and persistent observation by the researcher. Coding analysis and interpretations were done and verified by two researchers. A member check was done by feeding back data and findings to some participants. Transferability was ensured by describing the individual’s experiences and context. Attempts were made to describe the research steps transparently, to improve dependability and confirmability.

Limitations include the restricted generalizability of the study findings to other contexts or settings. Method and data triangulation was not attempted. Non-assessment of temperament/personality attributes and coping skills is another limitation.

Conclusion

This study explored the family factors that contribute to suicidal attempts among adolescents and young adults. The findings suggest that perceived family context, including disruptive family environment, faulty interactions between family members, and lack of perceived family support, plays an important role in determining suicidal behavior among adolescents and young adults. Hence, it is imperative to explore these factors in clinical practice while treating a person with a recent suicide attempt and while planning any suicide prevention strategies for them. Context-specific understanding of the individual distress, early identification of youth at risk, and family interventions involving multidisciplinary teams may help prevent suicide attempts.

Future research may include quantitative studies to systematically look at these risk factors and find the effectiveness of family-level intervention strategies. Further steps may include incorporating such successful interventions in suicide prevention programs for adolescents and young adults.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Suicide data, https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/ (2019, accessed March12, 2020).

- 2.India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Suicide Collaborators Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2016. Lancet Public Health, 2018; 3(10): e478–e489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Crime Records Bureau Accidental deaths and suicides in India. Report, Ministry of Home Affairs. New Delhi: Government of India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel V, Ramasundarahettige C, Vijayakumar L, et al. Suicide mortality in India: a nationally representative survey. Lancet, 2012; 379(9834): 2343–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, and Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 2006; 47 372–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilsen J. Suicide and youth: Risk factors. Front Psychiatry, 2018; 9: 540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT. Risk factors for serious suicide attempts among youths aged 13 through 24 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 1996; 35(9): 1174–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turecki G and Brent DA. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Lancet, 2016; 387(10024): 1227–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Posner K, Melvin GA, Stanley B, et al. Factors in the assessment of suicidality in youth. CNS Spectr, 2007; 12(2): 156–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams DM, Overholser JC, and Lehnert KL. Perceived family functioning and adolescent suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 1994; 33(4): 498–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagan CR and Joiner TE. The indirect effect of perceived criticism on suicide ideation and attempts. Arch Suicide Res, 2017; 21(3): 438–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macalli M, Tournier M, Galéra C, et al. Perceived parental support in childhood and adolescence and suicidal ideation in young adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the i-Share study. BMC Psychiatry, 2018; 18(1): 373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yen S, Kuehn K, Tezanos K, et al. Perceived family and peer invalidation as predictors of adolescent suicidal behaviors and self-mutilation. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol, 2015; 25(2):124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiter B. Theory and methodology of exploratory social science research. Int J Sci Res Methodol, 2017; 5(4): 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun V and Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol, 2006; 3(2): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Björkenstam C, Kosidou K, and Björkenstam E. Childhood adversity and risk of suicide: a cohort study of 548721 adolescents and young adults in Sweden. BMJ, 2017; 357: doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1334 (Published 19 April 2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radhakrishnan R and Andrade C. Suicide: An Indian perspective. Indian J Psychiatry, 2012; 54(4): 304–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pillai A, Andrews T and Patel V. Violence, psychological distress, and the risk of suicidal behavior in young people in India. Int J Epidemiol, 2009; 38 459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasrado RA, Chantler K, Jasani R, et al. Structuring roles and gender identities within families explaining suicidal behavior in South India. Crisis, 2016; 37(3): 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao S and Zhang J. Suicide risk among adolescents and young adults in rural China. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2015; 12(1): 131–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vijayakumar L, John S, Pirkis J, et al. Suicide in developing countries (2): Risk factors. Crisis, 2005; 26 112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Wieczorek WF, Conwell Y, et al. Psychological strains and youth suicide in rural China. Soc Sci Med, 2011, 72 2003–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin G and Waite S. Parental bonding and vulnerability to adolescent suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 1994; 89 246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization Preventing suicide: A global imperative, https://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/ (2014, accessed March12, 2020).