Abstract

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a malignant soft tissue neoplasm with its origin in the skeletal muscle and is extremely rare in adults. By the World Health Organization (WHO), a new variant of RMS has been classified, i.e. the spindle cell (Sc) and sclerosing (S) RMS. While the Sc-RMS shows intersecting fascicles of nonpleomorphic spindle cells, the S-RMS is characterized by a marked hyalinization in a pseudovascular growth pattern associated with round-to-spindled tumour cells. According to the analysed data, the Sc/S-RMS variant has a worse outcome than other variants. The new classification of the Sc/S-RMS variant is valuable to the clinical practice. There are not many oral Sc/S-RMS cases reported. The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that an early diagnosis, an adequate treatment and a multidisciplinary approach have a positive effect on the prognosis of the patient. In this study, we analyse a new case of Sc-RMS variant in a young adult with an early diagnosis and a favourable outcome as a result of an appropriated multidisciplinary treatment: early surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy treatment.

Keywords: Rhabdomyosarcoma, Oral cancer, Spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma, Sarcoma

Introduction

Head and neck sarcomas are extremely rare tumours, so therapeutic algorithms are based on retrospective studies of the treatment of sarcomas from other locations. Its diagnosis might become really tough because of the clinical variability in its behaviour. In fact, the sarcomas count make up 2% of all the malignant head and neck tumours and 4–10% of all the adult sarcomas only [1].

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a malignant soft tissue neoplasm of skeletal muscle origin. It is the most common soft tissue tumour during childhood and responsible for approximately one-half of all soft tissue sarcomas in this age group [2]. However, RMS in adults is extremely rare [3].

Aetiology and risk factors are still unknown. Most cases of RMS seem to be sporadic, but the disease is associated with some familial syndromes such as neurofibromatosis, the Li-Fraumeni, Beckwith-Wiedemann, and Costello syndromes [4].

There are four categories of RMS: alveolar, embryonal, pleomorphic and spindle cell/sclerosing [5]. The last one was defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) and comprises between the 5% and the 13% of all the cases of RMS [6].

The treatment of RMS has changed over the past several decades. The cure rates increased due to the use of combined modality therapy trials, conducted by large international cooperative groups, such as the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group (IRSG), which is now known as the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group [7].

Due to the recent reclassification of the Sc/S-RMS variant, there are only few data on prognosis and clinical course. However, over 70% of the children, with localized RMS, can be cured due to the use of modern combined modality therapy [7, 8].

Hereunder, we present a new case of Sc-RMS of a young adult in the tongue with a long-term survival in the head and neck region.

Case Study

In this case study, we analyse a case of a 29-year-old man who presented an intra-lingual mass. The patient suffered no pain, no taste loss, no swallowing difficulties nor lingual numbness. The main complaint referred to the middle line of the lingual mass and some mild discomfort when exploring the patient. The lingual tumour measured approximately 7 × 9 mm and was localized in the anterior part of the tongue, affecting the middle line. A surgical treatment involving a complete exercise was proposed. Patient informed consent was obtained.

Due to the tumour size and the benignity signs, an excisional biopsy was performed (Fig. 1) under local anaesthesia. An intraoral approach was carried out by performing the initial incision with a 15-blade scalpel and chasing a blunt dissection, exposing the mass and preserving the tumour capsule at the anterior lingual midline level. In order to achieve a haemostasis, the electrocoagulation was used involving the surgical field and an absorbable 3/0 Vicryl was used to suture the incision as a direct closure.

Fig. 1.

Extracapsular biopsy of the tumour

From the macroscopical perspective, the tumour displayed a rounded morphology with well-defined limits and measured 10 × 8 mm. After cutting, it showed a yellowish colouration and a firm consistency. No foci of necrosis or bleeding were observed.

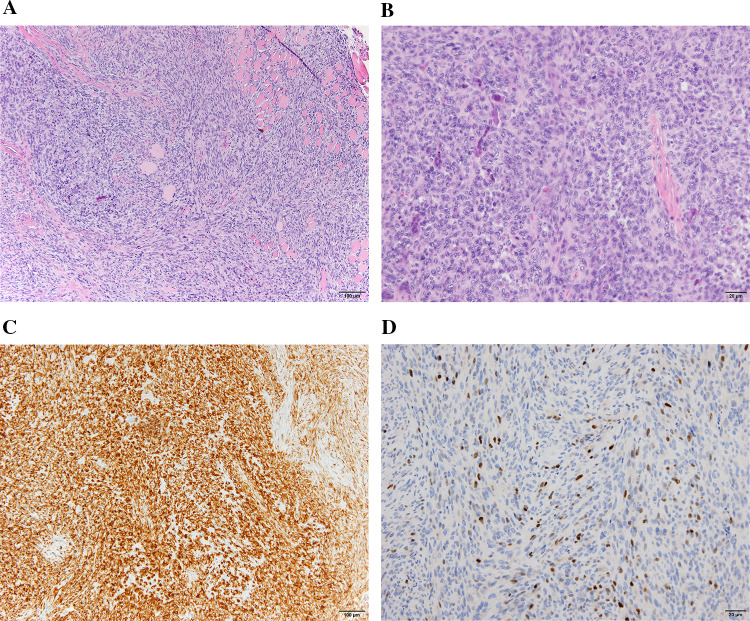

From the microscopically perspective, it was a spindle cell tumour with high cell density, markedly infiltrative edges and focally collagenous stroma. The spindle cells presented a pale eosinophilic cytoplasm with an oval and sometimes vesicular nucleus and showed moderate–severe cell atypia with a mitotic index of 5–7 mitosis per 10 high-magnification fields. Along with these cells, which made up the majority in the neoplasia, other cells with less spindle cell morphology, a large eosinophilic cytoplasm and peripheral nucleus were observed. In addition, multinucleated giant cells were found. A microscopic examination revealed a Sc-RMS according to the new classification variant [5] (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Spindle cell varaint RMS. a Spindly sarcomatous cells disposed in fascicles. Hematoxilina and Eosina (H and E) × 10. b Sarcomatous cells with rhabdomyoblastic cells. H and E × 20. c Diffuse desmin positivity × 10. d Diffuse MyoD1 positivity. DAB × 20

The immunohistochemistry revealed a positive result of vimentin, desmin (Fig. 2b), myogenin and smooth muscle actin and being negative results for CK AE1-AE3, beta-catenin, CD34, EMA, S100, STAT6 and HerpesVirusVIII. Focally, there an intense nuclear positivity for myogenin was shown (Fig. 2c). The proliferation index measured with Ki67 was high at approximately 35%.

After the pathological anatomy result, the case was discussed by a multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncological Committee of a tertiary Spanish Hospital which decided to enlarge the resection borders and perform an extension study with Body Computed Tomography due to the histopathological characteristics of the RMS and the actual guidelines of this pathology.

The first step afterwards was to carry out a Body Computed Tomography (Body-CT) in order to exclude regional or distant dissemination. The CT scan showed no signs of linfogenous or haematogenous spreading and no lingual mass remaining. The multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncological Committee decided not to perform a cervical lymph node dissection but to control the patient closely, by carrying out Body-CTs every 6 months. This decision was based on the initial size of the tumour, the lack of regional or distal dissemination, and the histopathological characteristics.

The second step consisted in performing a middle line glossectomy that included the anterior lingual scar resulted from the first surgery. The surgery was done this time under general anaesthesia due to the discomfort involved in handling the tongue and in order to facilitate the correct exploration of the tissues, to remove precisely the remaining fibrous tissue from the previous surgery and because of the diameters needed as oncological margins. The lingual dissection depth covered the entire fibrotic tissue. Again, the incision was directly closed using absorbable 3/0 Vicryl. The postoperative period was without sequels, and neither wound dehiscence. Figure 3 shows the patient 2 months after the surgery.

Fig. 3.

Two months after surgery patient image. The patient hasn’t sequels after surgery

The results regarding the partial glossectomy piece of 30 × 20 × 15 mm, showed a new neoplastic centre of one millimetre and signs of fibrosis and chronical inflammation. The margins were widely respected.

One month later, the patient started with a chemotherapy consisting of four sessions (Ifosfamide, Vincristine and Adriamicine scheme), every 21 days. He presented neutrophilia after the fourth month and needed hospitalization without any further complication. Afterwards, he completed the treatment with radiotherapy, obtaining a 5000 cGy total dose at the surgical location only.

Since that, we carry out a long-term control every 2 months. In addition, the patient is being followed up by the Medical Oncology and Radiation Oncology Departments. From the first surgery, more than 4 years have passed and the patient is disease-free (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forty eight months after the surgery. The patient is disease-free

Discussion

The herein described case of a Sc-RMS of the tongue is very rare. The particular interest in this case is the patient's overall survival of 48 months since the primary diagnosis, which is the longest disease-free survival of an adult patient suffering a Sc-RMS in the tongue reported so far in the literature.

RMSs can occur in all parts of the body [9]. Of all soft tissue sarcomas, 35–40% occur in the head and neck [10] and only 10% of these occur in the oral cavity [11]. The RMS of the tongue is rare and only a few cases are reported in the literature [12]. Sarcomas represent approximately 7% of all malignant tumours in young adults, while RMS is the most prevalent tumour [13, 14]. The poorer prognosis of adult Sc-RMS is in significant contrast to the prognosis of childhood Sc-RMS, which could be attributable to the fact older patients are less tolerant of chemotherapy and their tumours are less chemosensitive [15].

The Sc-RMS variant shows a predilection for the testicle region, followed by head and neck [16]. In contrast, the Indian study [17] found out that 50% of the cases were located in the head and neck area. Since the new classification of the WHO deals with the Sc/S-RMS variant as a single entity, the number of cases published in the oral cavity increases from 16. We added a new case in this classification with a good prognosis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Oral spindle cell and sclerosing RMS cases published in the English literature

| Case | Author | Age | Sex | Location | Histology | Treatment | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Owosho et al. [6] | 34 years | Female | Masticator space | Sclerosing RMS | Surgery + Chemotherapy + radiotherapy |

Distant recurrence Dead for disease |

| 2 | Owosho et al. [6] | 17 years | Female | Masticator space | Sclerosing RMS | Surgery + Chemotherapy + radiotherapy |

Alive No recurrence |

| 3 | Owosho et al. [6] | 28 years | Male | Masticator space | Sclerosing RMS | Chemotherapy + Radioherapy | Dead for disease |

| 4 | Owosho et al. [6] | 33 years | Male | Soft tissue mandible | Sclerosing RMS | Surgery + Chemotherapy + radiotherapy |

Local and distant recurrence Dead for disease |

| 5 | Owosho et al. [6] | 14 years | Male | Tongue | Spindle cell | Surgery | Not known |

| 6 | Owosho et al. [6] | 41 years | Male | Soft tissue mandible | Spindle cell | Surgery + radiotherapy | Alive. No recurrence |

| 7 | Owosho et al. [6] | 33 years | Male | Tongue | Spindle cell | Surgery + Chemotherapy | Alive. No recurrence |

| 8 | Yasui et al. [18] | 23 years | Female | Tongue | Spindle cell | Chemotherapy |

Distant recurrence Dead for disease |

| 9 | Rekhi et al. [17] | 19 years | Male | Oral cavity | Spindle cell | Surgery + Chemotherapy + radiotherapy |

Local recurrence Allive with disease (12 months) |

| 10 | Rekhi et al. [17] | 11 years | Male | Maxilla | Sclerosing/Spindle cell RMS | Surgery + Chemotherapy |

Local and distant recurrence Alive with disease (22 months) |

| 11 | Rekhi et al. [17] | 31 years | Female | Cheek | Sclerosing RMS | Surgery + radiotherapy |

Recurrence Dead for disease (16 months) |

| 12 | Rekhi et al. [17] | 2 years | Male | Palate | Spindle cell | Surgery | Not known |

| 13 | Smith et al. [20] | 24 years | Male | Hard palate | Spindle cell | Surgery + Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | No recurrence in 4 years |

| 14 | Smith et al. [20] | 39 years | Male | Buccal mucosa | Spindle cell | Surgery + Chemotherapy | Recurrence in 1,5 years |

| 15 | Smith et al. [20] | 22 years | Male | Gingiva | Spindle cell | Chemotherapy + Radioherapy | No response. Dead for disease |

| 16 | Gupta et al. [21] | 3 months | Female | Tongue | Spindle cell | Chemotherapy + Brachytherapy | 3 months; residual tumour |

| 17 | Our case | 29 years | Male | Tongue | Spindle cell | Surgery + Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | Alive. No recurrence |

Histopathogeneis, is still unclear but, however, the most accepted hypothesis with regard to RMS comes from the proliferation of the mesenchymal embryonic tissue. The spindle cell variant is similar to the sclerosing variant due to its clinical, histopathological and genetic aspects which are separated from the other three categories [6].

The Sc-RMS shows intersecting fascicles of nonpleomorphic spindle cells, reminiscent of leiomyosarcoma or fibrosarcoma, in contrast to S-RMSs which are defined by marked hyalinization in a pseudovascular growth pattern associated with round-to-spindled tumour cells [18], assimilating to entities such as osteosarcoma, angiosarcoma or alveolar RMS [19]. The cells contain an oblong nucleus with chromatin and a light cytoplasm. The defining histological characteristics, indicated above, are also shown in our case.

RMS is characterized by a typical immunohistochemistry. While desmin and vimentin are found in most of the cases, such as also in our case, mioglobin, myogenin, SMA MSA and Myo-D1 are found irregularly only [20]. However, RMS is negative for melanoma, vascular and neuroendocrine markers, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and paraqueratins [21].

In spite of an uniform morphology of the Sc/s-RMS, the head and neck areas has specific characteristic. During the childhood exists an alteration of NCOA2 or either VGLL2 genes exist, which are involved in muscle development. These mutations are related to a positive outcome and no distant metastasis [6]. However, the same does not apply to MYOD1 mutations which are often developed in older children and young adults [21]. These tumours have a preference for the sclerosing variety and are associated with poor prognosis and early distant metastasis. The patient described herein underwent molecular studies for MYOD1 mutations.

The new classification of soft tissue tumours was changed, by the WHO, defined the Sc/S-RMS was reclassified as a stand-alone entity. Both spindle cell and sclerosing variants involve the head and neck frequently [22, 23] and according to the literature, children and adults are affected [22]. However, there are no many cases of oral Sc/S-RMS in English literature (Table 1).

Head and neck sarcomas are extremely rare tumours, so the therapeutic algorithms are based on retrospective case studies based on the treatment of sarcomas from other body locations. The most cases of RMS are treated with a combination of surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy [20]. The multidisciplinary approach is critical for these patients. The chemotherapy agents used in most cases of rabdomyosarcomas are actinomycin D, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, cyclophosphamide, etoposide or vincristine [24]. Due to the lack of randomized studies for the Sc/S-RMS, we opted to treat our patient with those chemotherapy agents which are typically used in RMS. There are Ifosfamide, Vincristine and Adriamicine followed by radiotherapy [24]. Recurrence and progression are common despite a multimodal treatment [20]. Nevertheless, distant metastasis is less relevant than locoregional recurrence. Thus, an aggressive local surgery combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy should improve the prognosis as we show in our case.

Our case is one of the first cases published in the literature with a favourable outcome after more than 4 years after surgery and it is the first case published in Spain, as far as we know. This outcome is suggested by an early diagnosis without linfogenous or haematogenous spreading at the time of diagnosis. This characteristic is one of the most important ones in order to get a favourable outcome.

Conclusion

The new classification of the Sc/S-RMS variant is valuable to the clinical practice and the literature. Although Sc/S-RMS is very rare in adults and often is associated with a poor prognosis, we have provided a favourable new case of tongue Sc/S-RMS to the medical literature. In the present case, it is important to emphasize the early diagnosis, the radical surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment according to the guidelines of rhabdomyosarcoma management in order to improve the outcome for the patient. Previous multidisciplinary treatment plays an important role for a positive prognosis.

Funding

There is no founding source.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest in the present paper.

Ethical Approval

The Declaration of Helsinki was followed in the present study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Potter BO, Sturgis EM. Sarcomas of the head and neck. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12(2):379–417. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3207(03)00005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr FG, Womer RB, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma. In: Orkin SH, Fisher DE, Look AT, et al., editors. Oncology of infancy and childhood. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. pp. 743–781. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari A, Dileo P, Casanova M, Bertulli R, Meazza C, Gandola L, Navarria P, Collini P, Gronchi A, Olmi P, Fossati-Bellani F, Casali PG. Rhabdomyosarcoma in adults. A retrospective analysis of 171 patients treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2003;98(3):571–580. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li FP, Fraumeni JF., Jr Soft-tissue sarcomas, breast cancer, and other neoplasms. A familial syndrome? Ann Intern Med. 1969;71(4):747–752. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-71-4-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parham DM, Barr FG, Montgomery E, Nascimento AF. Skeletal muscle tumors. In: Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F, editors. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owosho AA, Huang SC, Chen S, Kashikar S, Estilo CL, Wolden SL, Wexler LH, Huryn JM, Antonescu CR. A clinicopathologic study of head and neck rhabdomyosarcomas showing FOXO1 fusion-positive alveolar and MYOD1-mutant sclerosing are associated with unfavorable outcome. Oral Oncol. 2016;61:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Punyko JA, Mertens AC, Baker KS, Ness KK, Robison LL, Gurney JG. Long-term survival probabilities for childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. A population-based evaluation. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1475–1483. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crist W, Gehan EA, Ragab AH, Dickman PS, Donaldson SS, Fryer C, Hammond D, Hays DM, Herrmann J, Heyn R, et al. The third intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(3):610–630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malempati S, Hawkins DS. Rhabdomyosarcoma: review of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Soft-Tissue Sarcoma Committee experience and rationale for current COG studies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(1):5–10. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanzkowsky P. Rhabdomyosarcoma and other soft-tissue sarcomas. Manual of pediatric hematology and oncology. Oxford: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 561–584. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fatusi OA, Ajike SO, Olateju SO, Adebayo AT, Gbolahan OO, Ogunmuyiwa SA. Clinico-epidemiological analysis of orofacial rhabdomyosarcoma in a Nigerian population. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38(3):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekhar MS, Desai S, Kumar GS. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma involving the jaws: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:1062–1065. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.8754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ognjanovic S, Linabery AM, Charbonneau B, Ross JA. Trends in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma incidence and survival in the United States, 1975–2005. Cancer. 2009;115(18):4218–4226. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordón-Núñez MA, Piva MR, Dos Anjos ED, Freitas RA. Orofacial rhabdomyosarcoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:765–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little DJ, Ballo MT, Zagars GK, Pisters PW, Patel SR, El-Naggar AK, Garden AS, Benjamin RS. Adult rhabdomyosarcoma: outcome following multimodality treatment. Cancer. 2002;95(2):377–388. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nascimento AF, Fletcher CD. Spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma in adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(8):1106–1113. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000158396.57566.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rekhi B, Singhvi T. Histopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular cytogenetic analysis of 21 spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcomas. APMIS. 2014;122(11):1144–1152. doi: 10.1111/apm.12272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasui N, Yoshida A, Kawamoto H, Yonemori K, Hosono A, Kawai A. Clinicopathologic analysis of spindle cell/sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(6):1011–1016. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folpe AL, McKenney JK, Bridge JA, Weiss SW. Sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma in adults: report of four cases of a hyalinizing, matrix-rich variant of rhabdomyosarcoma that may be confused with osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1175–1183. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith MH, Atherton D, Reith JD, Islam NM, Bhattacharyya I, Cohen DM. Rhabdomyosarcoma, spindle cell/sclerosing variant: a clinical and histopathological examination of this rare variant with three new cases from the oral cavity. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(4):494–500. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0818-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta A, Maddalozzo J, Win Htin T, Shah A, Chou PM. Spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma of the tongue in an infant: a case report with emphasis on differential diagnosis of childhood spindle cell lesions. Pathol Res Pract. 2004;200(7–8):537–543. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll SJ, Nodit L. Spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma: a brief diagnostic review and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137(8):1155–1158. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0465-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson JC, Richardson MS, Neville BW, Day TA, Chi AC. Sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma: report of a case arising in the head and neck of an adult and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7(2):193–202. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0398-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konieczny P, Sułkowski M, Badyra B, Kijowski J, Majka M. Suicide gene therapy of rhabdomyosarcoma. Int J Oncol. 2017;50(2):597–605. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]