Abstract

Objective

Surgical management of condylar head is largely deferred due to the lack of appropriate armamentarium or instrumentation, restricted surgical access and risk of iatrogenic complications. Here we delineate open reduction internal fixation of condylar head fracture with various fixation modalities using specialized instrumentation for visualization and providing access for reduction with minimal complications.

Methods

A total of 21 patients were reported with condylar head fracture of mandible to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery from January 2017 to June 2018. Three patients had bilateral condylar head fracture, making it a total of 24 fractures. All patients had clinical symptoms including deranged occlusion, limited mouth opening, jaw deviation and restricted mandibular movements. The radiological findings were dislocated or displaced condylar head medially or laterally. All patients were treated by open reduction internal fixation using lag screws or standard long screws.

Results

Among condylar head fractures, 19 of the study population were male and 2 were female. Distribution of age among the condylar head fractures ranges from 19 years to 40 years with the mean being 22 years. At the end of three-month follow-up, all patients had satisfactory results, both clinically and radiologically. The functional outcome of this study was found to be superior.

Conclusion

We recommend open reduction internal fixation of condylar head for patients with high risk of ankylosis, and it is possible without complications due to the availability of minimally invasive surgical access system.

Keywords: Diacapitular fracture, Condylar head fracture, Lag screws, Long screws

Introduction

Management of condylar fracture has remained an enigma for the operating surgeon over the centuries [1].

Conservative approach such as closed reduction with intermaxillary fixation is the method of choice as a less invasive procedure for the management of the condylar head fracture [2, 3].

Condylar head or intracapsular fractures are managed conservatively though they were reported cases of osteomyelitis, aseptic necrosis, degenerative changes and even fibro-osseous ankylosis [4–6]. Surgical management of condylar head is largely deferred due to the lack of appropriate armamentarium or instrumentation [7].

The surgical access to the condylar head fracture is very restrictive, and the surgical outcome is not always successful [8]. It may be due to inability to achieve anatomic reduction, limited surgical access and difficulty in fixation [9]. In addition, the prolonged surgical procedure under general anesthesia and a perceptible extra oral scar may also contribute for the relatively lower surgical intervention [10].

Here, we delineate the open reduction internal fixation of condylar head fracture with various modalities of fixation using specialized instrumentation for visualization and providing access for reduction with minimal complications.

In our study, we planned for open reduction and internal fixation of patients with condylar head or diacapitular fracture who will potentially benefit from open surgical intervention.

Patients and Methods

A total of 50 patients were reported with condylar fracture of mandible to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery from Jan 2017 to June 2018.

Of the 50 patients, 21 patients had condylar head fracture, 5 patients had condylar neck fracture and 24 patients had subcondylar fracture. Of the 21 patients with condylar head fracture, 3 patients had bilateral fractures, making it a total of 24 fractures. 17 fractures were isolated condylar head fracture of which three patients had vertical split in the middle causing a diacapitular fracture, and 7 fractures were condylar head associated with symphysis and parasymphysis fracture.

All 21 patients had clinical symptoms including deranged occlusion, limited mouth opening and restricted mandibular movements. 15 patients presented with deviation of jaw. The radiological findings were dislocated or displaced condylar head medially or laterally. All patients were treated by open reduction internal fixation method using either lag screws or standard long screws. The mean duration between the time of trauma and the surgery is 5 days. Surgical approaches were determined based on the position of the fracture. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Clinical and radiological examination was done for all patients preoperatively. Measurements were made for clinical and radiological parameters. Clinical parameters were mouth opening, occlusal stability, mandibular protrusion and lateral movements. Radiological parameters were gap between the fractured segments of the condyle and the angulation of the condyle. Radiological parameters were assessed using computed tomography showing axial, coronal and 3-dimensional view (Fig. 1). A DICOM viewer was used to assess the 3-dimensional reconstruction images (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Arrow showing the bilateral head of the condyle fracture in coronal view of computed tomography. Measurements were made to determine the length of the lag screw for open reduction internal fixation

Fig. 2.

A DICOM viewer showing the three-dimensional reconstruction images with medially dislocated head of the condyle fracture bilaterally

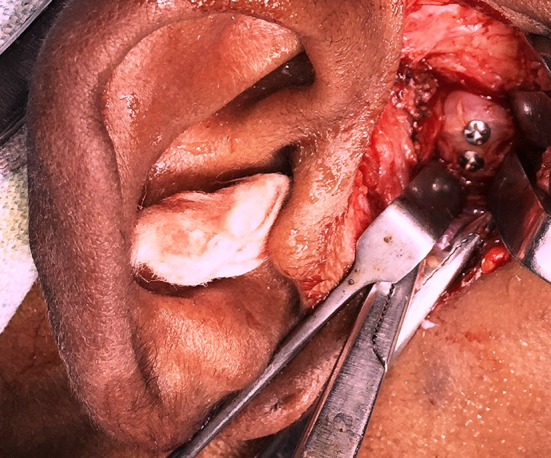

Intraoperatively, Erich’s arch bars were placed for all the fractures after the induction of General Anesthesia, patient preparation and patient draping. All fractures were approached extra orally. Proper skin preparation and markings were done. Layer-wise dissection done exposing the condyle and the fractured segment (Fig. 3). A specialized instrument called Modified Juniper retractor was used to distract the condylar stump from the glenoid fossa to increase the joint space and accessibility. With the created space, the fractured condyle is retrieved using positional screws. 10-mm screw is inserted into the fractured condylar head segment for its retrieval. The medial portion of fractured condyle is pushed outward with the help of the screw and restored in position to achieve the ramus height. Then, the fractured segments were fixed using lag screws or standard long screws perpendicular to the fracture line (Fig. 4). Standardized titanium long screws of 2.0 mm and lag screws of 2.0 mm, of length 14 mm to 16 mm were used. Fixation was done in intermaxillary fixation after achieving stable occlusion. Positional screw was maintained until fixation for absolute anatomic reduction and removed after the stable fixation. Layer-wise closure done using 3-0 Vicryl and 4-0 Ethilon sutures. Patient extubated and recovery were uneventful.

Fig. 3.

Arrow indicating the exposure of the fractured condylar head and the stump of the condyle on right side

Fig. 4.

Open reduction internal fixation of the condylar head using two bicortical screws

All patients were followed up for a period of minimum 6 months. The intervals of the follow-up were immediate post-op, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and 1-year post-op. Both clinical and radiological parameters were analyzed during the post-treatment period. All the patients were on long-term follow-up.

Results

Among the condylar head fracture, 19 of the study population were males and 2 were females. Distribution of age among the condylar head fractures ranges from 19 to 40 years with the mean being 22 years.

The surgical approaches for the patients under open reduction group were preauricular approach (56.25%), postauricular approach (12.5%) and retromandibular approach (31.25%). Transient facial nerve weakness was observed in only one patient. At the end of 3-month postoperative review, the recovery of facial nerve function was evident.

In the fixation modalities, we used either lag screws or long bicortical screws. Most of our patients had only one screw placed to secure the fragment with that of the stable fragment. Our results showed similar results for lag screw fixation and standard long screw fixation in terms of stability. At the end of follow-up period, none of the patients had screw loosening or secondary displacement of the fractured segment.

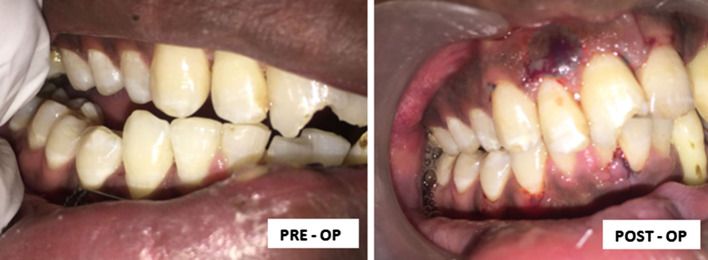

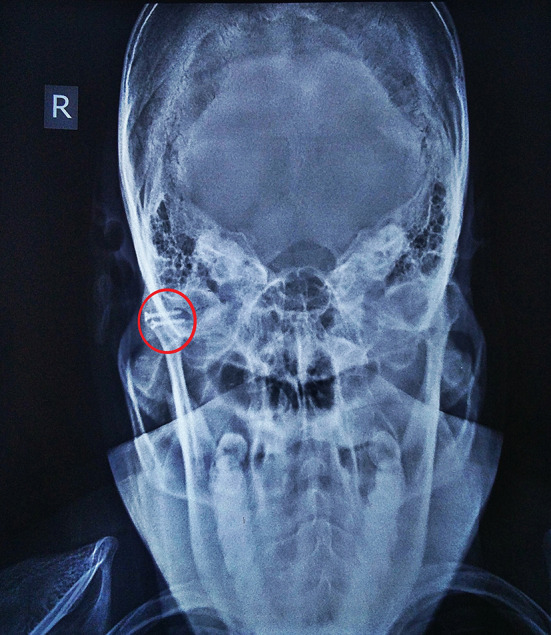

At the end of 3-month follow-up, all patients had good mouth opening and mandibular movements with satisfactory improvement in jaw deviation. None of the patients had occlusal derangement (Fig. 5). Healing was good for all patients, which were confirmed by postoperative radiographs (Fig. 6). The outcome of this study was found to be superior both clinically and radiologically.

Fig. 5.

Preoperative and postoperative occlusion

Fig. 6.

Post-op Towne’s view on the follow-up of 6 months showing reduction in fractured segments

Discussion

Incidence of maxillofacial injury varies according to the demographic distribution. Road traffic accidents and interpersonal violence have been reported as the most common cause of trauma [11]. The other etiologies of maxillofacial injuries are fall, penetrating injuries, sports injuries, fire arm injury and animal bite [12, 13].

The pattern of fracture depends on the mechanism of injury. Indirect forces are the common causative factor for the condylar fractures [14]. The direction of force toward the angle of the mandible will tend to fracture condylar head, the direction of force toward chin and body of the mandible might result in condylar neck and subcondylar fractures [15].

Wassmund’s classification in the early 20th century is considered as the first documented classification based on the direction of the forces acting onto the condyle [16]. There are numerous classifications for the head of the condyle fracture [17, 18]. But the exact management protocol is inappropriately described for the diacapitular or condylar head fracture.

Management of condylar fracture has long been reminded as an enigma with proponents for both open and closed reduction approaches [19, 20]. Surgical management of the condylar head fracture still remains a rarity. Though a consensus is still elusive, proponents of open reduction claim a superior long-term functional result [18, 21, 22].

In functional therapy, muscle component and dental component remodels the shape and the pattern of the condyle which aids in proper functioning of the jaw. However, functional therapy in displaced condyle may cause chronic pain, shortening of ramus with facial asymmetry, occlusal discrepancy, bigonial plane alteration, ankylosis and degenerative changes [23]. In these conditions, it is desirable to reposition the condylar fragment by open method. In our study, all patients had displaced or dislocated condylar head with occlusal derangement. Here, the repositioning of condyle cannot be achieved by non-surgical means.

In the follow-up period, the preexisting anatomic relationship was restored using stable fixation which was evident in radiographic documentation. Complete functional re-establishment including mouth opening and jaw movements were achieved postoperatively. These absolute clinical and radiological re-establishments may not be possible in closed method. Therefore, open method is superior over conservative or functional therapy in dislocated head of the condyle fractures with deranged occlusion and limited functional movements.

Difficulties encountered in open reduction and internal fixation of condylar head is two holed. One is the access to the fractured part of the condyle head and mandibular stump. Second is the reduction and retrieval of the fractured segment. Considering the difficulties associated with the management of head of the condyle fractures, a modified juniper retractor was used. It consists of two horns which helps to distract the stump of the condyle from the glenoid fossa which increases the join space enabling the retrieval of the fracture fragment of the condylar head (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Modified juniper retractor

The surgical approaches for the patients with condylar head fracture play a very significant role as an appropriate approach should minimize the potential risk of iatrogenic injury to the facial nerve while providing adequate exposure for fracture reduction and fixation.

In pursuit of identifying the ideal surgical approach, preauricular approach in our study provided good access with the maximum visualization of medially dislocated head of the condyle fractures. Only one patient had had transient facial nerve weakness. The recovery of facial nerve function was complete at the 3rd month of postoperative review.

Intermaxillary guiding elastics were used for all patients who underwent open surgical intervention for a period between 1 to 3 weeks. However, at the end of follow-up period, all patients had good mouth opening, stable occlusion and mandibular movements.

In conclusion, our aim was to emphasize the importance of open reduction and internal fixation of head of the condyle fracture for patients who will potentially benefit from open surgical intervention. We recommend open reduction internal fixation of condylar head for patients with higher risk of ankylosis, and it is possible without complications due to the availability of minimally invasive surgical access system and superior fixation system.

This study should encourage further research in ideal instrumentation both to improve visualization and to achieve a reliable, stable fixation in patients with condylar head fracture.

Funding

No source of funding.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Valiati R, Ibrahim D, Abreu MER. The treatment of condylar fractures: To open or not to open? A critical review of this controversy. Int J Med Sci. 2008;5(6):313–318. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutges JPHJ, Kruizinga EHW, Rosenberg A, et al. Functional results after treatment of fractures of the mandibular condyle. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller W. The therapy of condylar fractures: clinical study for the evaluation of various modes of treatment. Zahn MundKieferheilkd Zentralbl. 1976;64(5):496–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xanders B, McKelvy B, Adams D. Aseptic osteomyelitis and necrosis of the mandibular condylar head after intracapsular fracture. J Oral Surg. 1977;43(5):665–670. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He D, Ellis E, Zhang Y. Etiology of temporomandibular joint ankylosis secondary to condylar fractures: the role of concomitant mandibular fractures. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo-lin X, Xing L, Mo-hong D, et al. A retrospective study of temporomandibular joint ankylosis secondary to surgical treatment of mandibular condylar fractures. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52(3):270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckelt U, Schneider M, Erasmus F, et al. Open versus closed treatment of fractures of the mandibular condylar process–a prospective randomized multi-centre study. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2006;34:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi B-H, Yi C-K, Yoo J-H. MRI examination of the TMJ after surgical treatment of condylar fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30(4):296–299. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perumal Jayavelu R, Riaz A, Tariq Salam R, et al. Difficulties encountered in preauricular approach over retromandibular approach in condylar fracture. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(1):S175–S178. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.191953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidal Molina C, Obsen Moreno R, Badilo Coloba O, et al. Development and management of complications condylar fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42(10):1236. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subashraj K, Nandakumar N, Ravindran C. Review of maxillofacial injuries in Chennai, India: a study of 2748 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:637–639. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo S, Li B, Long X, et al. Surgical treatment of sagittal fracture of mandibular condyle using long screw osteosynthesis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:1988–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montovani JC, Campos LM, Gomes MA, et al. Etiology and incidence of facial fracture in children and adults. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;72:235. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuna EB, Dündar A, Çankaya AB, et al. Conservative approach to unilateral condylar fracture in a growing patient: a 2.5-year follow up. Open Dentistry J. 2012;6:1–4. doi: 10.2174/1874210601206010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inada M, Konuma T, Shimada J, et al. Biomechanical study on the mechanism of the mandibular condylar fracture. Nihon Ago Kansetsu Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;1(1):89–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wassmund M. Fractures and dislocation of the facial skull, taking into account the complications of the brain damage. Berlin: Meusser 3–18, 255–260

- 17.Loukota RA, Neff A, Rasse M. Nomenclature/classification of fractures of the mandibular condylar head. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;48:477–478. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He D, Yang C, Chen M, et al. Intracapsular condylar fracture of the mandible: our classification and open treatment experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1672–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi K-Y, Yang J-D, Chung H-Y, et al. Current concepts in the mandibular condyle fracture management part II: open reduction versus closed reduction. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39(4):301–308. doi: 10.5999/aps.2012.39.4.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Riu G, Gamba U, Anghinoni M, et al. A comparison of open and closed treatment of condylar fractures: a change in philosophy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30(5):384–389. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones SD, Sugar AW, Mommaerts MY. Retrieval of the displaced condylar fragment with a screw: simple method of reduction and stabilisation of high and intracapsular condylar fractures. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;49:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang WH, Deng JY, Zhu J, et al. Computer-assisted virtual technology in intracapsular condylar fracture with two resorbable long-screws. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Moraissi EA, Ellis E. Surgical treatment of adult mandibular condylar fractures provides better outcomes than closed treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:482–493. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]