Abstract

Aim

Analysing Level of Evidence (LOE) provides an insight to evidence-based medicine (EBM). The aim of our study was to evaluate and analyse trends in Levels of Evidence (LOE) in Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery (MAOS) since inception, i.e. December 2009 along with categorization into subtopics.

Methodology

LOE for each article was determined according to modified American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) scale and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Evidence Hierarchy.

Results

A total of 1264 articles were included in the final analysis, out of which high-quality evidence (Level A) accounted for 7% of the journal. The percentage of Level I/II (Level A) has increased from 2.09% in 2009/2010 to 12.74% in 2019/2020, representing a promising trend toward higher-quality research in just 10 years. Case reports and narrative reviews with Level of Evidence value “D” account the highest number (36%) of all the published articles. The majority of articles fell under Class 2 (Maxillofacial pathology) classification (35%) highlighting myriad of articles covering pathologies and various reconstruction methods, followed by trauma (16%).

Conclusion

The status of LOE and categorizing of published articles are the first step to audit and quantify the nature of literature published by JMOS and may further help in refining the quality of research jointly by the researchers and the editorial board.

Keywords: Level of Evidence (LOE), Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery (MAOS), Evidence-based medicine (EBM)

Introduction

Bibliometrics is the discipline where quantitative approaches are applied mainly to scientific fields and are based principally on various aspects of written articles like subject, author, citation, title, etc. [1]. It is beneficial for monitoring growth of the literature and pattern of research in a journal [2] .

Evidence-based Medical practice (EBM) is the mainstay for any diagnostic, therapeutics, prognostic, medical or surgical decision making for the patient care. Predominant backbone of EBM is the ability to codify any study based on Level of Evidence (LOE). Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (OMFS) is an evolving speciality requiring training in both medicine and dentistry and is specially rooted in experimentation and innovation. Scientific journals are excellent platforms for two-way communication of research findings, latest discoveries and developments, and future research prospects, thus having a pivotal role in amalgamating EBM in any clinical speciality.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which have been the gold standard for unbiased evidence, have found a limited role in surgical specialities, due to lack of understanding of RCTs, epidemiological and statistical training in the surgical community. Ethical considerations like Sham surgeries (placebo surgeries), lack of funding, surgical learning curve and lack of feasibility of blinding of surgeons, lack of long-term follow-ups of outcomes are few of the other major challenges in conducting high-level RCTs. In defiance of all these odds, OMFS as a speciality is trying to evolve leaps and bounds from a field driven by anecdotal evidence and expert opinions to embrace evidence-based medicine.

Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery (MAOS) is a quarterly, official peer-reviewed publication of the Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons of India (AOMSI). MAOS got PubMed indexed in December 2009, since then it has played a very crucial role in complete spectrum of academics, disseminative, contemporary, scholarly, technical, cutting-edge innovations, diagnostic works and future trends related to extensive field of OMFS. It focuses on publishing original articles, review articles, editorials, letter to the editor, case reports, technical notes, mini reviews and commentaries.

Refining of research quality published in OMFS journals is an uphill task where assessing the trends of LOEs in a journal is the first and critical step. The aim of our study was to evaluate and analyse trends in Levels of Evidence (LOE) in Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery(MAOS) since inception, i.e. December 2009. A secondary purpose was to describe the current publication pattern in terms of LOE and sub-categories.

Methodology

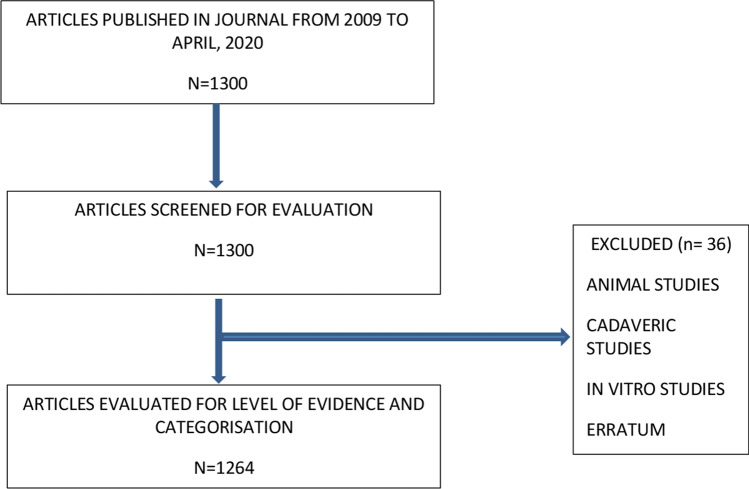

A search team including three authors (AK, AP and RT) screened and reviewed all the articles of MAOS since December 2009–April 2020. The team worked in pairs so that two authors separately screen each article and any discord was settled by consulting senior author KC and RB. An explicit data extraction sheet was prepared categorizing all the articles based on LOE and themes and all the articles published in MAOS from 2009 (Volume 8 Issue 1) to 2020 (Volume 19 Issue 2). Cataloguing the LOE was done as per Table 1 that was prepared, objectified and simplified according to modified American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) scale [3] and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Evidence Hierarchy [4]. Articles were further classified by reviewers according to the study design: (1) systematic review, (2) RCT, (3) prospective cohort studies, (4) meta-analysis, (5) case–control study, (6) retrospective study, (7) analytical cross-sectional study, (8) descriptive cross-sectional study, (9) case series, (10) case reports, (11) narrative reviews, (12) expert opinions, (13) editorials/letter to editor, (14) perspectives, (15) technical notes. Published articles on basic sciences, in vitro studies, animal studies, cadaveric studies, instructional course lectures and conference proceedings were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, each article was assigned an LOE by the reviewers according to Table 1 with any discrepancy settled by consensus. Highest quality evidence is produced from randomized controlled trails or systemic reviews/meta-analysis of the RCTs, thus given Level A. The lowest Level of Evidence (Level E) was given to articles of limited study designs like editorials, expert opinions or technical notes. Smaller LOE values (i.e. closer to A) indicate research that presents higher-quality evidence. The articles were simultaneously categorized according to the subspeciality as shown in Tables 1 and 2. The flowchart of methodology was as depicted in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Level of Evidence (LOE) distribution according to modified American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) scale [3] and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Evidence Hierarchy [4]

| LOE name | LOE value |

|---|---|

| Level I/II | |

| Prospective RCT’s | A |

| Prospective cohort studies | |

| Systematic review of RCT’s, | |

| Cohort studies | |

| Meta-analysis | |

| Level III | |

| Case–control study | B |

| Retrospective study | |

| Systematic review of case control | |

| Studies | |

| Analytical cross-sectional studies | |

| Level IV | |

| Case series | C |

| Descriptive cross sectional | |

| Systematic review of cross | |

| Sectional or case series | |

| Level V | |

| Case reports | D |

| Narrative reviews | |

| Expert opinion | |

| Editorials/letter to editor | E |

| Perspectives | |

| Technical notes | |

| Excluded | |

| Animal studies, cadaveric studies, | X |

| In vitro studies, erratum, | |

| Conference proceedings | |

Table 2.

Categorical distribution of the articles

| Category name | Category value | Category name | Category value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Minor oral surgery Exodontia Impaction Endodontic surgery Pre-prosthetic surgery Orthodontic/paediatric Tooth exposure |

1 |

Trauma Dentoalveolar fracture Maxillary fracture Mandibular fracture NOE fracture Orbito-zygomatic fracture Naso-orbito-ethmoid fracture Frontal fracture Pan facial fracture Soft tissue injuries Ballistic injuries |

5 |

|

Maxillofacial pathology Cysts of the oral cavity Odontogenic and Nonodontogenic tumours Oral cancer Head and neck tumours Salivary gland pathologies Maxillary sinus pathologies Premalignant lesions Vascular lesions Reconstructive surgery and Tissue engineering |

2 | Dental implants | 6 |

|

Dentofacial deformity and aesthetics Orthognathic surgery Distraction Osteogenesis Aesthetic Surgery/Procedures Hair Transplant Sleep Apnoea procedures Orofacial cleft |

3 |

Space infection and systemic infectious Diseases Head & Neck Space Infections Osteomyelitis, Osteoradionecrosis, Osteochemonecrosis Systemic manifestations of infectious diseases |

7 |

|

TMJ and orofacial pain Orofacial neuropathy and Neurological disorders TMJ disorders, TMD Myofascial pain All neuralgias |

4 |

Miscellaneous Armamentarium Diagnostics Sterilization and disinfection Suturing materials and techniques Haemorrhage and shock Wound care Local anaesthesia General anaesthesia Medically compromised patients Medical emergencies and their Management Burns |

8 |

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the methodology of the study

Statistical Analysis

The descriptive statistics of the number of articles published according to the year, Level of Evidence and category of the topic were done to evaluate the percentages of each variable. Chi-square test was done to evaluate the distribution of number of articles according to the year, Level of Evidence and category of the topic. The variations in the publication of different levels of evidence were analysed using the bar charts. All statistical tests were done using the SPSS software version 21, and the P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

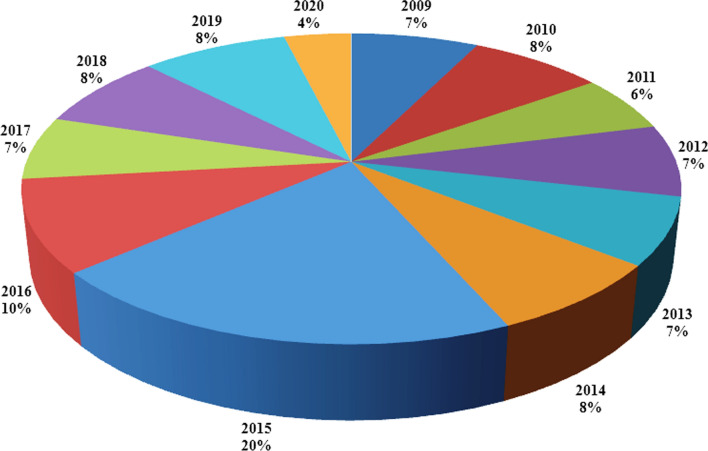

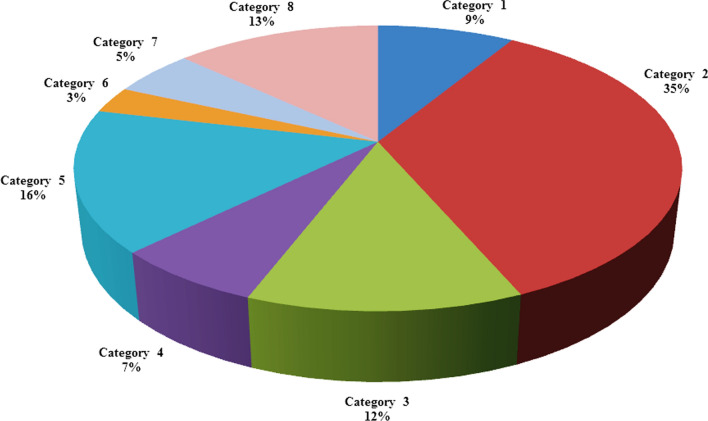

The descriptive statistics of the number of articles published according to the year, Level of Evidence and category of the topic are presented in Figs. 2, 3 and 4, respectively. Maximum of the articles (20%) were published during the year 2015. Case reports and narrative reviews with Level of Evidence value “D” account the highest number (36%) of all the published articles from 2009 to 2020. Maxillofacial pathology category ranks the highest number of publications (35%) from 2009 to 2020.

Fig. 2.

Pie chart showing % distribution of the article’s yearwise from 2009 to 2020

Fig. 3.

Pie chart showing % distribution of the article’s Level of Evidence (LOE) from 2009 to 2020 with major contribution by Level D studies

Fig. 4.

Pie chart showing % distribution of the article’s sub-topic categorization from 2009 to 2020 with major contribution by Category 2 studies

The distribution of year of publication and Level of Evidence of the published articles from 2009 to 2020 are presented in Fig. 5. The Chi-square test showed significant difference (P = 0.000) in the distribution of articles from 2009 to 2020 according to different Level of Evidence values (Table 3). The distribution of year of publication and category of the topic of the published articles are shown in Fig. 4. The Chi-square test showed significant difference (P = 0.009) in the distribution of articles from 2009 to 2020 according to categories of the topics published (Table 4). The distribution of articles published according to different levels of evidence and category of the topics are presented in Fig. 5. The Chi-square test showed significant difference (P = 0.000) in the distribution of articles according to different levels of evidence and different categories of the topics published (Table 5). The variations in the publication of articles with different levels of evidence are presented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Histogram showing yearly distribution of the article’s Level of Evidence (LOE) from 2009 to 2020

Table 3.

Distribution of year of publication and Level of Evidence of the published articles

| Number of articles published in each Level of Evidence (percentages) | Total number of articles published | Chi-square value | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | |||||

| Year of publication | 2009 | 3 (3) | 43 (46) | 3 (3) | 35 (38) | 9 (10) | 93 (100) | 198.345a | 0.000* |

| 2010 | 1 (1) | 33 (34) | 3 (3) | 48 (49) | 13 (13) | 98 (100) | |||

| 2011 | 4 (5) | 20 (27) | 6 (8) | 34 (45) | 11 (15) | 75 (100) | |||

| 2012 | 2 (2) | 41 (43) | 10 (11) | 35 (37) | 7 (7) | 95 (100) | |||

| 2013 | 11 (12) | 22 (25) | 17 (20) | 24 (27) | 14 (16) | 88 (100) | |||

| 2014 | 12 (12) | 20 (20) | 34 (35) | 21 (22) | 11 (11) | 98 (100) | |||

| 2015 | 25 (10) | 35 (14) | 41 (16) | 32 (51) | 24 (9) | 257 (100) | |||

| 2016 | 7 (6) | 30 (25) | 12 (10) | 52 (43) | 20 (16) | 121 (100) | |||

| 2017 | 6 (7) | 37 (32) | 24 (22) | 15 (18) | 17 (21) | 83 (100) | |||

| 2018 | 6 (6) | 37 (38) | 24 (24) | 18 (18) | 14 (14) | 99 (100) | |||

| 2019 | 11 (10) | 34 (32) | 24 (22) | 23 (21) | 16 (15) | 108 (100) | |||

| 2020 | 5 (10) | 12 (25) | 13 (26) | 12 (25) | 7 (14) | 49 (100) | |||

| Total | 93 (7) | 354 (28) | 205 (16) | 449 (36) | 163 (13) | 1264 (100) | |||

The values in the tables were presented as percentages of total number of articles published

Chi-square test was used to analyse the significant difference between the year and Level of Evidence values of the published articles

*P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant

Table 4.

Distribution of year of publication and category of the topic of the published articles

| Number of articles in each category of the topic (percentage) | Total number of articles published | Chi-square value | P value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||

| Year of publication | 2009 | 8 (9) | 34 (37) | 11 (12) | 4 (4) | 18 (19) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 13 (14) | 93 (100) | 109.584a | 0.009* |

| 2010 | 4 (4) | 42 (43) | 11 (11) | 5 (5) | 20 (21) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 12 (12) | 98 (100) | |||

| 2011 | 8 (11) | 29 (39) | 9 (12) | 1 (1) | 14 (19) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 13 (17) | 75 (100) | |||

| 2012 | 7 (7) | 35 (37) | 11 (12) | 4 (4) | 20 (21) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 14 (15) | 95 (100) | |||

| 2013 | 14 (16) | 22 (25) | 13 (15) | 6 (7) | 9 (10) | 2 (2) | 6 (7) | 16 (18) | 88 (100) | |||

| 2014 | 5 (5) | 28 (29) | 15 (16) | 8 (8) | 12 (12) | 6 (6) | 8 (8) | 16 (16) | 98 (100) | |||

| 2015 | 20 (8) | 110 (43) | 24 (9) | 18 (7) | 42 (16) | 7 (3) | 18 (7) | 18 (7) | 257 (100) | |||

| 2016 | 11 (9) | 41 (34) | 21 (17) | 6 (5) | 19 (16) | 5 (4) | 4 (3) | 14 (12) | 121 (100) | |||

| 2017 | 10 (12) | 28 (34) | 10 (12) | 9 (11) | 9 (11) | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | 11 (13) | 83 (100) | |||

| 2018 | 10 (10) | 25 (26) | 13 (13) | 9 (9) | 23 (23) | 2 (2) | 4 (4) | 13 (13) | 99 (100) | |||

| 2019 | 12 (13) | 33 (31) | 14 (13) | 10 (9) | 11 (10) | 3 (3) | 9 (8) | 15 (14) | 108 (100) | |||

| 2020 | 0 (0) | 13 (26) | 4 (8) | 6 (13) | 6 (12) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 10 (21) | 49 (100) | |||

| Total | 110 (9) | 440 (35) | 156 (12) | 86 (7) | 203 (16) | 38 (3) | 66 (5) | 165 (13) | 1264 (100) | |||

The values in the tables were presented as percentages of total number of articles published

Chi-square test was used to analyse the significant difference between the year and Level of Evidence values of the published articles

*P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant

Table 5.

Distribution of Level of Evidence and category of the topic of the published articles

| Number of articles in each category of the topic (Percentage) | Total number of articles published | Chi-square value | P value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||

| Level of Evidence | A | 34 (36) | 7 (7) | 8 (9) | 8 (9) | 21 (23) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 12 (13) | 93 (100) | 387.019a | 0.000* |

| B | 49 (14) | 87 (25) | 54 (15) | 27 (8) | 83 (23) | 14 (4) | 11 (3) | 29 (8) | 354 (100) | |||

| C | 11 (5) | 47 (23) | 33 (16) | 22 (11) | 36 (18) | 9 (4) | 16 (8) | 31 (15) | 205 (100) | |||

| D | 9 (2) | 260 (58) | 44 (10) | 18 (4) | 43 (10) | 6 (1) | 34 (7) | 35 (8) | 449 (100) | |||

| E | 7 (4) | 39 (24) | 17 (11) | 11 (7) | 20 (12) | 7 (4) | 4 (2) | 58 (36) | 163 (100) | |||

| Total | 110 (9) | 440 (35) | 156 (12) | 86 (7) | 203 (16) | 38 (3) | 66 (5) | 165 (13) | 1264 (100) | |||

The values in the tables were presented as percentages of total number of articles published

Chi-square test was used to analyse the significant difference between the year and Level of Evidence values of the published articles

*P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant

Discussion

Bibliometrics is a set of statistical methods to analyse academic literature quantitatively and its changes over time. However, subfield of bibliometric, i.e. restricted to analysis of scientific publications, is called scientometrics. The term “bibliometrie” was coined by Paul Otlet in 1934 [5]. Peer-reviewed publication is primary mode of communication and recorded for scientific research which forms the basis of LOE and EBM. Individual studies can be judged for its quality if it is peer-reviewed publication, if it has followed reporting guidelines and its citation indices for healthcare stimulation research.

Different study designs based on the research questions have found use in different conditions. For therapeutic, RCTs are the best form of study and for prognostics well-designed cohorts are the best form of study. Former is the highest form in interventional studies and later being in observational study. Depending on the quality of study conducted and type of research question sometimes LOE may vary. For example, cigarette smoking association with oral cancer cannot be assessed with RCT; here, depending on this research question, well-designed cohort will form the Level 1 evidence. Levels I and II were combined in our study to minimize subjectivity in high- and low-quality RCT. In vitro, animal studies and pilot studies are the building blocks and finally pave way for future clinical research formed 3% of the journal publications. The animal studies may not necessarily be able to reliably predict the safety and efficacy of an intervention when trailed in humans [6]. They were excluded from the LOE as guidelines and were given Level X [3].

There has been a growth in levels A, B and C evidence, with a reduction in the publication in lower-quality evidence. In total, high-quality evidence (Level A) accounted for 7% of the journal which is much lower than orthopaedic literature (21.6%) [7], neurosurgical (10.3%) [8] but higher than the previously published maxillofacial research in 2007 showing 0% articles in Level I evidence and 2% for Level II evidence [9] and plastic surgery having 2% Level I evidence in 2018 [10]. This finding corresponds well to the field of surgery, because it is difficult to conduct a standard RCT in a surgery. The major difficulties include the feasibility of randomization and compliance with random allocations. Moreover, it is difficult to persuade a patient to comply with newer drugs or surgery based on hypothesis of animal studies.

However, there has been rapid expansion in technology and heightened awareness of RCTs, and the quality of the articles is improving with time. In this study, evaluating LOE of over 1264 articles over the last decade, analysis showed that the percentage of Level I/II (Level A) has increased from 2% in 2009/2010 to 12.74% in 2019/2020, representing a significant and promising trend toward higher-quality research in just 10 years.

Case series are the backbone of surgical research as they comprise of similar group of patients with a common intervention. No doubt, the absence of control group has shifted its value to quite a lower level, but its value is special in surgery. Level C which includes case series forms 16% of the literature. Case reports are important although they cannot be regarded as clinical evidence and forms the bulk of the journal (36%). Further, there were two supplemental issues in the year 2015 and 2016 of case reports only; lower Level of Evidence was seen in these two years. As it is said never judge a book by its cover, and the same is true for case reports. Most of the time, the large-scale and extensive clinical trials are planned on the basis of results of a single case report. Editorials, expert opinions and technical notes form a total of 13% of all articles, having similar advantage as of a case report. They were excluded from the LOE as guidelines in spite of that we computed and were found as capitulations/submissions in Level E [3].

Also, the majority of articles fell under Class 2 (Maxillofacial pathology) classification (35%) highlighting myriad of articles covering pathologies and various reconstruction methods, followed by trauma (16%). Both these categories form major bulk due to emphasis placed during training in these aspects. However, there is still long way to go in the field of dental implants forming only 3% of the literature.

Even though bibliographic studies are a hefty job, still our analysis has several limitations. Mostly bibliometric analysis is computing citation index which was not calculated in our study. Citation index though important may be erroneous as usually narrative reviews, and case reports which form lowest step in LOE pyramid usually have high citation. It has been found many articles downloaded, discussed but not cited, thus skewing citation index as a wide criterion for evaluating a study. This bibliometric study has just quantified all the articles based on type of study. No attempt was made to assess the quality of each article using any tool or software. Our results lack critical appraisal of each article’s methodology, bias and power [3]. There is a critical distinction between a study LOE and its inherent quality, exemplified by the fact that even RCTs are susceptible to flaws in design and may suffer from poor Jadad scores, which are used to quantify the strength of the trial design [11]. Thus, in this study articles have been quantified for the LOE; individual articles have not been assessed for their quality.

Last few decades have shown a surge in publications of various qualities which may be attributed to multitude of reasons including widespread use of Internet facility, faster dissemination, current publish and perish culture in academia. All of this has led to an explosion of scientific publications that has overwhelmed the publication system and has made it impossible either for the traditional, and generally effective, peer-reviewed system to work or for the scientific community to evaluate a lot of scientific research. Efforts to improve the reproducibility and integrity of science are needed as the published results are unreliable due to growing problems with research and publication practices [12].

To improve the quality of research, we should invest sufficient time for strategic research and should be able to identify the barriers in the implementation of the methods. Also, research methodology courses should be made mandatory for the trainees to fill the lacunae left behind in the undergraduate days and to avoid research misconduct. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) should be the motto for every thesis topic or project allotted to postgraduate students and researchers [13] .

Conclusion

Seglenonce said, “Science deserves to be judged by its contents, not by its wrapping,” which remains true for characterization of individual papers and scientists [14]. The LOE of MAOS literature has increased over time, as demonstrated by increased proportion of Level I/II evidence. The main critic remains the readers which should judge on the basis of quality. Thus, a bibliometric study like this would help us to gauze the status of LOE of published MAOS articles, thus paving way for improving the quality of research conduction by researchers and acceptance by the editors.

Authors’ Contributions

Dr. Rishi Bali (RB) and Dr. Kirti Chaudhry (KC) helped in study conception and design. Dr. Amanjot Kaur (AK), Dr. Arun K. Patnana (AP) and Dr. Rahul VC Tiwari (RT) acquired the data. AP and AK analysed and interpreted the data. KC and AK drafted the manuscript. KC and RB critically revised.

Funding

No funding was taken for this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kirti Chaudhry, Email: chaudhry_kirti@yahoo.com.

Rishi Kumar Bali, Email: rshbali@yahoo.co.in.

Amanjot Kaur, Email: amanjotkaur1992@yahoo.com.

Rahul V. C. Tiwari, Email: drrahulvctiwari@gmail.com

Arun K. Patnana, Email: arun0550@gmail.com

References

- 1.Hussain A, Fatima N, Kumar D. Bibliometric analysis of the ’Electronic Library’ journal (2000–2010) Webology. 2011;8(1):87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs D (2001) A bibliometric study of the publication patterns of scientists in South Africa 1992–96, with special reference to gender difference. In: Proceedings of the 8th international conference on scientometrics and informetrics, 275–85

- 3.Burns PB, Rohrich RJ, Chung KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):305–310. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHMRC levels of evidence. 2008–09NHMRC additional levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines. www.nhmrc.gov.au

- 5.Dutta B (2020) The journey from librametry to altmetrics: a look, Available at: http://eprints.rclis.org/23665/2/BDutta-JU-Golden-Jubilee-Paper.pdf (Accessed on 23 June)

- 6.Pound P, Ritskes-Hoitinga M. Can prospective systematic reviews of animal studies improve clinical translation? J Transl Med. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-02205-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Little Z, Newman S, Dodds A, et al. Increase in quality and quantity of orthopaedic studies from 2002 to 2012. J OrthopSurg (Hong Kong) 2015;23:375–378. doi: 10.1177/230949901502300325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yarascavitch BA, Chuback JE, Almenawer SA, Reddy K, Bhandari M. Levels of evidence in the neurosurgical literature: more tribulations than trials. Neurosurgery. 2012;71(6):1131–1138. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318271bc99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau SL, Samman N. Levels of evidence and journal impact factor in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugrue CM, Joyce CW, Carroll SM. Levels of evidence in plastic and reconstructive surgery research: Have we improved over the past 10 years? Plastic Reconstr Surg Global Open. 2019;7(9):e2408. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanelli D. Is science really facing a reproducibility crisis? Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(11):2628–2631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708272114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panse N, Sahasrabudhe P, Khade S. The levels of evidence of articles published by Indian authors in Indian journal of plastic surgery. Indian J Plast Surg. 2015;48(2):218–220. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.163072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seglen PO. Causal relationship between article citedness and journal impact. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 1994;45(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199401)45:1<1::AID-ASI1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]