Abstract

Objective

To estimate the incremental associations between the implementation of expanded Medicaid eligibility and prerelease Medicaid enrollment assistance on Medicaid enrollment for recently incarcerated adults.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Data include person‐level merged, longitudinal data from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections and the Wisconsin Medicaid program from 2013 to 2015.

Study Design

We use an interrupted time series design to estimate the association between each of two natural experiments and Medicaid enrollment for recently incarcerated adults. First, in April 2014 the Wisconsin Medicaid program expanded eligibility to include all adults with income at or below 100% of the federal poverty level. Second, in January 2015, the Wisconsin Department of Corrections implemented prerelease Medicaid enrollment assistance at all state correctional facilities.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

We collected Medicaid enrollment, and state prison administrative and risk assessment data for all nonelderly adults incarcerated by the state who were released between January 2013 and December 2015. The full sample includes 24 235 individuals. Adults with a history of substance use comprise our secondary sample. This sample includes 12 877 individuals. The primary study outcome is Medicaid enrollment within the month of release.

Principal Findings

Medicaid enrollment in the month of release from state prison grew from 8 percent of adults at baseline to 36 percent after the eligibility expansion (P‐value < .01) and to 61 percent (P‐value < .01) after the introduction of enrollment assistance. Results were similar for adults with a history of substance use. Black adults were 3.5 percentage points more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release than White adults (P‐value < .01).

Conclusions

Medicaid eligibility and prerelease enrollment assistance are associated with increased Medicaid enrollment upon release from prison. States should consider these two policies as potential tools for improving access to timely health care as individuals transition from prison to community.

Keywords: adult, health policy, Medicaid, prisoners, substance use disorders

What is already known on this topic

Eliminating financial barriers to health care, by increasing Medicaid coverage, is an important step in improving access to care during the transition from correctional facilities to the community.

Expanding Medicaid eligibility is a key strategy for increasing coverage in this population.

Medicaid enrollment assistance has been shown to increase the likelihood of coverage for adults with serious mental illness after leaving prison but has not been evaluated in large populations reentering the community from prison.

What this study adds

We used administrative data to evaluate sequential natural experiments in Wisconsin, a Medicaid eligibility expansion, and the introduction of prerelease, Medicaid enrollment assistance.

Medicaid enrollment in the month of release from state prison grew from 8 percent of adults at baseline to 36 percent postexpansion and to 61 percent after the introduction of enrollment assistance; results were similar for adults with a history of substance use.

Findings anticipate the potential effects of the 2018 SUPPORT Act's Medicaid Reentry Provision that encourages states to implement prerelease enrollment assistance.

1. INTRODUCTION

Formerly incarcerated adults bear a disproportionate burden of disease, including substance use disorders, 1 mental illness, 2 and HIV, 3 conditions that require timely and ongoing medical care. However, as they reenter the community from correctional facilities, the likelihood of receiving treatment for many chronic conditions declines relative to the incarceration period, 4 and they experience high rates of emergency department use, 4 , 5 , 6 substance use, 4 and elevated rates of mortality particularly due to drug overdose. 7 , 8

Improved access to health care in the reentry period has the potential to mitigate these relatively high rates of morbidity and mortality. 9 However, historically a key component of access, health insurance coverage, has been largely unavailable to this population. Before the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), 80% of adults who were recently incarcerated lacked health insurance in the 2‐3 months following release. 4 The implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansions, now operating in 37 states, increased the proportion of recently incarcerated adults who are eligible for Medicaid. Such expanded eligibility set the stage for the Medicaid program to play a larger role in facilitating better health outcomes for adults transitioning from correctional settings to the community.

Ensuring Medicaid coverage at the time of release from jails and prisons is a federal policy priority articulated in the 2018 Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act. 10 The SUPPORT Act aims to combat the opioid epidemic through multiple mechanisms. Among them, the Medicaid Reentry provision encourages Medicaid programs to test strategies that ensure Medicaid enrollment for eligible individuals before they exit the correctional setting. The underlying premise is that by reducing financial barriers to care, Medicaid coverage may improve access to treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) thereby reducing the risk of drug overdose and supporting recovery. Although motivated by a need to improve outcomes for adults with OUD, the Reentry provision is not limited to this subgroup. Thus, its potential to influence health care access for adults reentering the community from correctional settings extends beyond any one diagnostic subgroup.

The rate of Medicaid enrollment among adults upon release from correctional facilities is unknown. Initial projections estimated that 21%‐34% of adults released from prison were likely to gain Medicaid coverage because of ACA Medicaid expansions. 11 However, no published research has isolated the effect of Medicaid eligibility expansions on enrollment upon release. Two recent studies assessed the 1‐year impact of the ACA's implementation as a whole, including Medicaid expansions, on health insurance status among adults with justice‐involvement in the prior year. Using the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, they report a 5 to 8 percentage point increase in Medicaid coverage for the justice‐involved population overall 12 and the subset of that population with substance use disorders (SUDs). 13 What remains unclear is the magnitude of increase that results from Medicaid eligibility expansions specifically, and whether expanded eligibility increases coverage during the critical period of reentry to the community.

The SUPPORT Act recognizes that eligibility alone is unlikely to secure enrollment among all eligible adults returning to the community from correctional facilities. Prerelease enrollment assistance aims to close this gap by facilitating completion of the application process before individuals leave the correctional setting. 14

The availability of prerelease enrollment assistance is growing but remains variable across and within states. 15 In 2018, prerelease enrollment assistance was available in prisons within 39 states and within at least some jails in 34 states. 16 Published estimates of the effects of enrollment assistance for incarcerated adults on Medicaid enrollment derive from studies of programs for adults with serious mental illness (SMI). 17 , 18 , 19 Wenzlow and colleagues found that Medicaid enrollment on the day of release increased by 15 percentage points for adults with SMI who were eligible for prerelease enrollment assistance relative to three similar comparison groups that were ineligible. 18 Morissey and colleagues compared the likelihood of Medicaid enrollment among adults with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia who were referred to an expedited enrollment program relative to a matched comparison group. 19 Medicaid enrollment upon release was 35 percentage points higher among the referred group relative to the comparison group.

In this study, we provide the first population‐based estimates of the association between expanded Medicaid eligibility and prerelease enrollment assistance, and Medicaid enrollment during the reentry period. We identify Medicaid enrollment status in the month of release from state correctional facilities by using a person‐level dataset that links Medicaid enrollment and corrections' data. We provide estimates for the population as a whole, and for adults with a history of substance use, a subgroup for whom prompt access to care postrelease can be lifesaving.

To accomplish this, we use a quasi‐experimental design that leverages two natural experiments to estimate the separate contributions of expanded eligibility and prerelease enrollment assistance on Medicaid coverage upon release. In this framework, the treatment assignment mechanism is the policy process that determined the implementation dates for expanded eligibility and enrollment assistance. This process is a strong approximation of an exogenous treatment assignment mechanism which mitigates the likelihood of bias from individual selection into Medicaid.

2. METHODS

2.1. Natural experiments

On April 1, 2014, the State of Wisconsin (WI) expanded Medicaid eligibility to all adults with income below 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL) notably including adults without dependent children. Before April 2014, parents with income below 100% FPL were already eligible for Medicaid. As a consequence of this expansion, we expect most adults released from WI state correctional facilities are eligible for Medicaid. 20 , 21 Funded at the state's standard matching rate rather than the enhanced match afforded ACA expansions, Wisconsin became the only “nonexpansion” state without a coverage gap between Medicaid and Marketplace subsidy eligibility.

Beginning in January 2015, the WI Department of Corrections (DOC) implemented prerelease Medicaid enrollment assistance. In the context of Wisconsin's policy to terminate, rather than suspend Medicaid coverage upon incarceration, enrollment assistance was offered to all individuals. The program served adults under the supervision of the state's Division of Adult Institutions (DAI) incarcerated within state correctional facilities; these include state prisons, correctional centers, and DAI‐contracted beds within county jails. Under the enrollment assistance program, individuals may apply for Medicaid as early as the 20th day of the month prior to their month of release which allows time for the Wisconsin Department of Health Services to send the individual's Medicaid card to their institution before release.

In all facilities, discharge planning staff provide guidance on how to apply for Medicaid, and individuals are given the opportunity to call an eligibility caseworker from the correctional facility to do so. Additionally, five facilities share three paralegal benefit specialists to assist with the enrollment process. The DOC selected these facilities based on the composition of their populations. The eligibility caseworkers who field all inmates' calls are employed by regional Income Maintenance Agencies. Typically, eligibility is determined during the initial call. The caseworker verifies information provided by the applicant using information exchanges, collects an electronic signature, determines eligibility, and notifies the applicant of the outcome. If deemed eligible, the Medicaid coverage is effective upon release.

2.2. Data

Using data accessed through data use agreements with relevant state agencies, we link DOC and Medicaid enrollment data at the person‐level in the Institute for Research on Poverty's Wisconsin Administrative Data Core in a secure data facility. 22 DOC prisoner records and Medicaid beneficiary enrollment records are matched to each other in the Data Core, using Social Security Numbers (last four digits), names, dates of birth, and other characteristics such as gender, race/ethnicity, and family relationships. The data match process for the Data Core uses probabilistic matching methods to account for name commonality, name variants, possible data entry errors, or other data quality issues.

2.3. Measures

From the DOC data, we obtain characteristics of the release facility, the incarceration episode, and the individual. Facility‐ and episode‐level characteristics include the security level (ie, jail, minimum, medium, medium/maximum, or maximum), the presence of a paralegal benefit specialist, admission and release dates, and the type of release (ie, supervised, unsupervised, other, death, out‐of‐state). Demographic characteristics include age, sex, education (ie, less than high school/GED, at least high school/GED), marital status (ie, married, single, other), race, and whether the county of conviction is part of a metropolitan statistical area. Race is measured in three categories: White, Black, and Other which includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, and Unknown. Following prior research, 23 county of conviction serves as a proxy for county of release which was inconsistently available in our data.

To explore the consequences of eligibility expansion and enrollment assistance for individuals with a history of substance use, we obtained self‐reported substance use history. During the study period, the DOC aimed to collect these data at least once during an individual's incarceration using a risk and needs assessment tool, the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS). 24 , 25 The COMPAS tool assesses individuals' history of substance use and past treatment for substance use. The COMPAS uses a proprietary algorithm to generate a score from the responses. This score is intended to reflect the need for treatment: unlikely, probable, or highly probable. 24 , 25 It is one factor that determines whether the DOC refers individuals to SUD treatment. Additional information about the COMPAS instrument and the substance use questions is provided in the appendix.

From Medicaid data, we obtained our primary outcome, Medicaid coverage in the month of release. This binary variable is set equal to one if the individual is enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release and zero otherwise. We do not observe if an individual was enrolled on the day of release. However, we observe the Medicaid application date. Individuals obtain the eligibility decision on the day of application. Thus, if the application date occurs before the release date, and the individual is enrolled in the month of release, it is likely that the individual had coverage on the day of release. We examine a secondary outcome as a proxy measure of coverage on the day of release. It is a binary indicator that is set equal to one if the individual is enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release and the date of their Medicaid application occurred within 60 days before the release date. We selected a 60‐day prerelease window because the actual release date may occur later than originally planned, and the original release date triggers the application process.

2.4. Study sample

We constructed our sample from the population of adults ages 19‐64 who were incarcerated by the state and released between January 2013 and December 2015, a total of 27 542 adults from 56 facilities. We restricted the sample to individuals released within the state of Wisconsin after an incarceration of at least 30 days to increase the likelihood that they completed the discharge planning process. The sample includes 24 235 individuals released from 46 facilities (Table S1 in Appendix S1). Adults with a history of substance use comprise our second sample, individuals whom DOC identified as having a highly probable need for substance use treatment. This sample includes 12 877 individuals. For individuals who had more than one release during the study period, we include only the first.

2.5. Study design

We use an interrupted time series (ITS) design to estimate the association between each of two policy interventions and Medicaid enrollment: expanded Medicaid eligibility, and the introduction of Medicaid enrollment assistance. 26

The first intervention is the April 1, 2014, Medicaid eligibility expansion. The DOC introduced Medicaid enrollment assistance in January 2015 with full implementation reached in April 2015. Our time series is sufficiently long to identify the association of each intervention with the outcome. 26 , 27 Specifically, the design includes 33 months total, including 15 months during the baseline period of January 2013 to March 2014; 9 months during the first intervention period April 2014 to December 2014; and 9 months during the second intervention period April 2015 to December 2015. We consider the first quarter of 2015 to be a phase‐in period and omit those 3 months from the regression analyses.

The chief threat to identifying the associations of interest within the ITS design is bias resulting from a confounding concurrent event. In our context that would be an event that is associated with the policy implementation dates of April 1, 2014, or April 1, 2015, and is also causally related to Medicaid enrollment among recently incarcerated adults. We are not aware of any such event but acknowledge that we cannot rule out the possibility.

2.6. Statistical analyses

We describe and compare sample characteristics in the month of release across the three policy periods using a t test for binary and continuous measures and the chi‐square test for categorical measures. We plot average monthly Medicaid enrollment among adults released in the month over the study period.

We implement the ITS design using segmented linear regression with robust standard errors controlling for covariates described above. 27 We estimate the level and slope of the outcome for each policy period of interest: the baseline, the Medicaid eligibility expansion, and implementation of enrollment assistance. We implement our main regression models separately for the full sample and for individuals with a history of substance use. Additional details about the empirical model are provided in the Appendix. All analyses were conducted with Stata version 15.

We conducted several additional analyses to assess the robustness, and explore the potential heterogeneity, of our findings. We tested the sensitivity of our results to the exclusion of individuals who began their incarceration period on or after April 2014, when the state expanded Medicaid eligibility, because exposure to this policy pre‐incarceration may influence the probability of Medicaid enrollment upon release from prison. We re‐estimated our models with logit regression. We interacted race with the policy variables in our main models and predicted the race‐specific change in the outcome associated with each policy intervention from the regression coefficients. We assessed the variation in Medicaid enrollment across facilities by estimating the likelihood of Medicaid enrollment after both policies were in place, April 2015 to December 2015, adjusting for individual characteristics. With these estimates, we predicted the proportion of individuals enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release by facility, holding all other variables at their observed values.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive statistics

The characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Women comprised 8%‐10% of the sample across the three study periods. Approximately two‐thirds of the sample had a high school diploma or GED, and more than 86% were single. On average, subjects were approximately 35 years old. The majority of the sample was White with an increase over time from 53.9% to 57.6%. Among the full sample, 57.5% of individuals had a history of substance use in the first period which decreased to 54.6% in the last period of the study. The mean duration of incarceration was 24.1 months among subjects released during the baseline period and increased to 31.0 months among those released in the enrollment assistance period. In each period, <1% of individuals were released to the community from state‐contracted beds in county jails. After the enrollment assistance program was implemented, approximately one‐third of adults were released from a facility in which a paralegal benefits specialist was available to support the program. These staff were not present at facilities in the prior two periods.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of adults released from Wisconsin correctional facilities, January 2013 to December 2015

| Characteristic |

Baseline 1/2013‐3/2014 |

Medicaid eligibility expansion 4/2014‐12/2014 |

Enrollment assistance program & eligibility expansion 1/2015‐12/2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of individuals | 11 403 | 6035 | 6797 |

| Female, % | 8.02 | 8.24** | 10.30** |

| Age | 34.59 | 34.96** | 35.52** |

| Race**, % | |||

| White | 53.88 | 56.80 | 57.55 |

| Black | 41.65 | 38.01 | 37.18 |

| Other | 4.47 | 5.19 | 5.27 |

| Education**, % | |||

| < High school/GED | 30.78 | 29.41 | 29.78 |

| >= High school/GED | 63.38 | 66.59 | 66.07 |

| Missing | 5.84 | 3.99 | 4.15 |

| Marital status**, % | |||

| Single | 86.71 | 87.92 | 86.70 |

| Married/Partner | 9.94 | 9.79 | 10.45 |

| Other | 3.35 | 2.29 | 2.85 |

| Rurality of county of conviction**, % | |||

| Part of MSA | 82.37 | 79.83 | 79.93 |

| Not part of MSA | 16.94 | 19.11 | 19.23 |

| Missing | 0.68 | 1.06 | 0.84 |

| History of substance use | 57.52 | 55.49* | 54.60** |

| Months incarcerated | 24.12 | 27.93** | 31.02** |

| Type of release**, % | |||

| Supervision | 86.68 | 91.48 | 92.95 |

| No supervision | 4.31 | 3.07 | 2.56 |

| Other | 9.02 | 5.45 | 4.49 |

| Paralegal benefits specialist available at release facility, % | 0 | 0 | 33.69** |

| Release facility security level**, % | |||

| Minimum | 34.96 | 37.86 | 42.90 |

| Medium | 53.86 | 50.97 | 46.58 |

| Medium/Maximum | 2.63 | 3.25 | 3.41 |

| Maximum | 8.23 | 7.75 | 6.94 |

| Jail | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

t tests were implemented to test equality of binary and continuous variables in the eligibility expansion and enrollment assistance policy periods relative to the baseline period. Chi‐square tests were implemented to test equality of frequencies across the three policy periods. MSA refers to metropolitan statistical area.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Authors' analysis of Wisconsin Department of Corrections administrative and case management data.

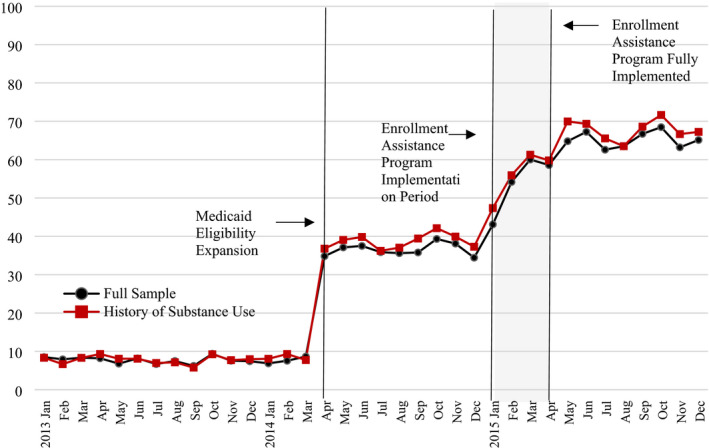

Figure 1 illustrates the unadjusted monthly trend in Medicaid enrollment in the month of release for the full sample and the subsample of adults with a history of substance use. The trends are nearly identical. During the baseline period, <10% of adults were enrolled in Medicaid within the month of their release. That figure increased abruptly in April 2014 with the introduction of expanded Medicaid eligibility to 35% for the full sample and 37% for adults with a history of substance use. After full implementation of the enrollment assistance program, 59% of all subjects and 60% of those with a history of substance use were enrolled in Medicaid within the month of release. At the conclusion of the study period, in December 2015, the percentage of all adults enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release was 65%; for adults with a history of substance use, it was 67%.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of adults released from a state correctional facility who are enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release. Source: Authors' analysis of Wisconsin Department of Corrections administrative and case management data and Wisconsin Medicaid enrollment data. Notes: The figure plots the unadjusted percentage of adults released in the month who are enrolled in Medicaid in that same month. The denominator is the number of adults released in each month, and the numerator is the number of individuals enrolled in Medicaid in that month

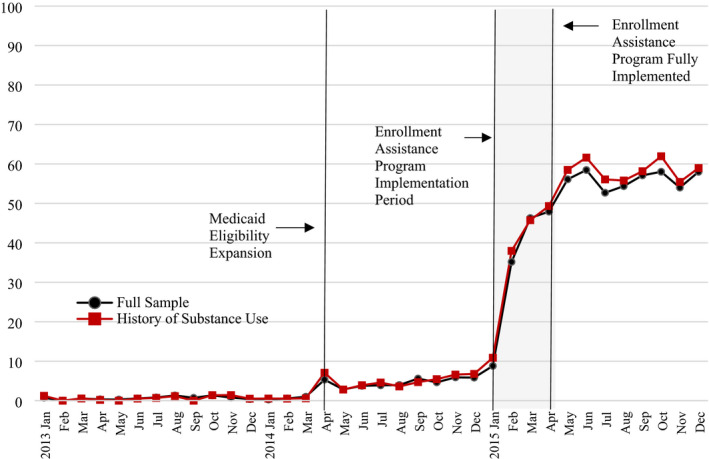

The percentage of adults released each month who also had a Medicaid application dated within 60 days before release is shown in Figure 2. During the baseline period, <1% of the full sample and 1% of those with a history of substance were enrolled in Medicaid and had completed the application in the 60 days before release. After the Medicaid expansion, those figures increased to approximately 5% and 7%, respectively. As of April 2015, the first month in which the enrollment assistance program was fully implemented, 48% of all adults and 49% of adults with a history of substance use were enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release and had an application dated within 60 days before release. By the end of the study period, December 2015, that figure increased to 58% of the full sample and 59% of the sample with a history of substance use.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of adults released from a state correctional facility who are enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release and had a Medicaid application within 60 d before the release date. Source: Authors' analysis of Wisconsin Department of Corrections administrative and case management data and Wisconsin Medicaid enrollment data. Notes: The figure plots the unadjusted percentage of adults released who were enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release and had a Medicaid application dated within 60 d before the release date

3.2. Regression analyses

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results from our segmented regression models. All reported changes are statistically significant at a P‐value of <.05. In Table 2, columns A & C present the estimated association between expanded eligibility and enrollment assistance, and Medicaid enrollment in the month of release. For the full sample shown in column A, 7.88% of adults were enrolled in Medicaid within the month of release at baseline. The implementation of the Medicaid eligibility expansion was associated with a 28.67 percentage point increase in the percentage of adults enrolled in Medicaid within the month of release. After full implementation of the enrollment assistance program, that grew by an additional 25.09 percentage points. As shown in column C, at baseline, 7.93% of adults with a history of substance use were enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release. The increases in enrollment associated with expanded eligibility and the enrollment assistance program were 29.75 and 23.75 percentage points, respectively. There was no significant change in the monthly trend in enrollment across periods.

TABLE 2.

Association of implementation of Medicaid eligibility expansion and prerelease enrollment assistance on Medicaid enrollment in the month of release, and a Medicaid application within 60 days before release, 2013‐2015

| Full sample | Adults with a history of substance use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Medicaid enrollment | (B) Medicaid enrollment and prerelease application | (C ) Medicaid enrollment | (D) Medicaid enrollment and prerelease application | |

| Baseline | ||||

| Predicted percentage at baseline | 7.88** | 0.84** | 7.93** | 0.95** |

| Change in monthly outcome trend | −0.03 | 0.005 | 0.004 | −0.005 |

| Medicaid eligibility expansion | ||||

| Change in level of outcome | 28.67** | 2.85** | 29.75** | 3.63** |

| Change in monthly outcome trend | 0.15 | 0.23* | 0.28 | 0.19 |

| Enrollment assistance program | ||||

| Change in level of outcome | 25.09** | 45.68** | 23.75** | 47.91** |

| Change in monthly outcome trend | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.14 | 0.33 |

| Age | 0.21** | 0.07** | 0.25** | 0.10** |

| Female | 15.15** | 3.38** | 15.04** | 2.54* |

| Race | ||||

| White (reference) | ||||

| Black | 3.53** | −0.68 | 2.84** | −0.81 |

| Other | −6.19** | −6.45** | −7.52** | −6.72** |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single (reference) | ||||

| Married/Partnered | −3.87** | −1.90** | −2.05 | −0.24 |

| Other | 1.20 | −1.45 | 4.62 | −0.63 |

| Education | ||||

| < High school/GED (reference) | ||||

| >= High school/GED | −0.09 | 0.14 | 1.10 | 0.31 |

| Missing | −1.09 | −1.71 | 1.68 | 0.19 |

| Rurality of county of conviction | ||||

| Part of MSA (reference) | ||||

| Not part of MSA | 0.98 | 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.67 |

| Missing | −2.07 | −2.03 | −7.00 | −8.39* |

| Incarceration episode | ||||

| Months incarcerated | −0.03** | −0.02** | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| Type of release | ||||

| Supervision (reference) | ||||

| No supervision | −1.67 | −1.73* | −2.86 | −1.75 |

| Other | 0.406 | −6.14** | 0.34 | −6.84** |

| Release facility security level | ||||

| Minimum (reference) | ||||

| Medium | 3.86** | 1.65** | 3.65** | 1.17* |

| Medium/Maximum | 0.10 | 1.12 | −3.12 | −0.30 |

| Maximum | 1.14 | −0.247 | 1.85 | 0.05 |

| Jail | −10.50** | −5.25 | −11.61** | −3.00 |

| Paralegal benefits specialist available at release facility | 0.50 | 1.35 | 0.55 | 1.54 |

| Observations | 22 502 | 22 502 | 11 956 | 11 956 |

| R 2 | .274 | .419 | .290 | .434 |

Columns A and C present results for our first outcome, Medicaid enrollment in the month of release. Columns B and D present results for our second outcome, Medicaid enrollment in the month of release and an application dated within 60 days before release. These results were generated from an interrupted time series model using ordinary least squares and robust standard errors. We predict the percentage of adults with the outcome at baseline by setting the time and policy variables to zero and holding all other variables at their observed values. For each independent variable, we present the percentage point change in the outcome associated with a 1‐unit change in the independent variable (ie, the model coefficient multiplied by 100). MSA refers to metropolitan statistical area.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Authors' analysis of Wisconsin Department of Corrections administrative and case management data and Wisconsin Medicaid enrollment data.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the association of Medicaid eligibility expansion and prerelease enrollment assistance on Medicaid enrollment in the month of release, and a Medicaid application within 60 days before release across race, 2013‐2015

| Full sample, N = 22 502 | History of substance use, N = 11 956 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | Other | White | Black | Other | |

| Panel A: Medicaid enrollment | ||||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Predicted percentage at baseline | 6.58 | 9.65** | 8.80 | 7.56 | 8.61 | 9.28 |

| Change in monthly outcome trend | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.18 | −0.04 | 0.12 | −0.22 |

| Medicaid eligibility expansion | ||||||

| Change in level of outcome | 28.41 | 29.9 | 21.69 | 29.22 | 33.07 | 16.75 |

| Change in monthly outcome trend | 0.26 | −0.10 | 0.80 | 0.50 | −0.48 | 2.07 |

| Enrollment assistance program | ||||||

| Change in level of outcome | 26.17 | 25.49 | 8.73 | 24.79 | 25.64 | 1.76 |

| Change in monthly outcome trend | 0.12 | 0.67 | −0.29 | −0.09 | 1.05 | −2.06 |

| Panel B: Medicaid enrollment and prerelease application | ||||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Predicted percentage at baseline | 0.6 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 0.84 | 1.06 | 0.91 |

| Change in monthly outcome trend | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.005 |

| Medicaid eligibility expansion | ||||||

| Change in level of outcome | 2.97 | 2.52 | 3.37 | 3.59 | 3.94 | 2.27 |

| Change in monthly outcome trend | 0.36 | 0.10 | −0.41 | 0.37 | −0.18 | −0.20 |

| Enrollment assistance program | ||||||

| Change in level of outcome | 46.63 | 45.08 | 38.06 | 47.64 | 50.74 | 37.50 |

| Change in monthly outcome trend | 0.09 | 0.86 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.87 | −0.10 |

Panel A includes results for our first outcome, Medicaid enrollment in the month of release. Panel B presents results for our second outcome, Medicaid enrollment in the month of release and an application dated within 60 d before release. Other race includes American Indian/Alaskan Native; Asian or Pacific Islander; and Unknown. These results were generated from an interrupted time series model using ordinary least squares including all covariates shown in Table 2 and robust standard errors. Each policy variable is interacted with race; White race is the reference category. We predict the percentage of adults with the outcome at baseline by setting the time and policy variables to zero, and the race variable to the identified category, holding all other variables at their observed values. For each independent variable, we use the regression coefficients to predict the race‐specific change in outcome. The table displays the prediction multiplied by 100 to yield the percentage point change in the outcome associated with a 1‐unit change in the independent variable. We test the equivalence of the predicted change relative to the change observed for the White reference category.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Authors' analysis of Wisconsin Department of Corrections administrative and case management data and Wisconsin Medicaid enrollment data.

In columns B and D of Table 2, we present the results for our second outcome, Medicaid enrollment in the month of release with a Medicaid application dated within 60 days before release. For the full sample in column B, at baseline, 0.84% of adults were enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release and had a Medicaid application date within 60 days before release. After implementation of the Medicaid eligibility expansion, an additional 2.85% of adults released were enrolled in Medicaid in the release month with a Medicaid application within 60 days before the release. The full implementation of enrollment assistance was associated with an additional 45.68 percentage point increase. Among the sample of adults with a history of substance use presented in column D, 0.95% at baseline were enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release and had a Medicaid application date within 60 days before release. The increase in this outcome associated with expanded eligibility and the enrollment assistance program was 3.63 and 47.91 percentage points, respectively. The monthly trend in Medicaid enrollment in the release month after a Medicaid application dated within 60 days before release increased for the full sample by 0.23 percentage points.

Women were 15 percentage points more likely than men to be enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release (Table 2, column A). On average, Black adults were 3.5 percentage points more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release than White adults. Adults of other races were 6 percentage points less likely to be enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release than White adults. Relative to those released from minimum security facilities, individuals released from medium security facilities were 3.9 percentage points more likely, and those released from county jails were 10.5 percentage points less likely, to be enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release.

Table 3 presents results from our regression models in which the policy variables were interacted with race. We tested the equivalence of the predicted change associated with each policy intervention for Black adults and adults of other races to the predicted change among White adults. The only statistically significant difference in findings across the racial subgroups is the baseline percentage of Black adults enrolled in Medicaid within the month of release (9.56%) relative to White adults (6.58%). This difference is consistent with the main results noted above in which Black adults were more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid than White adults. While the point estimates for adults of other races are substantially lower than those among White adults, we interpret these findings with caution because the confidence intervals are very wide (results not shown).

The main results were robust to the exclusion of individuals incarcerated after April 2014 and to estimation using logit regression (Tables S2‐S4 in Appendix S1). There was considerable variation in Medicaid enrollment within the month of release across facilities, after both policies were in place (ie, April 2015 to December 2015). The point estimates range from 1% to 79% with wide confidence intervals in many instances due to relatively small sample sizes at some facilities (Figure S1 in Appendix S1).

4. DISCUSSION

We examined the separate contributions of two policies to the likelihood of Medicaid coverage for adults released from state correctional facilities: expanded Medicaid eligibility and prerelease enrollment assistance. There are three key findings. First, each policy was associated with substantially increased Medicaid enrollment in the month of release. Second, prerelease enrollment assistance was associated with a higher likelihood that individuals applied for Medicaid before their release date. Third, the increases in Medicaid coverage associated with eligibility expansion and enrollment assistance were generally the same for the full sample and for those with a history of substance use.

Medicaid enrollment increased by 28 percentage points in the month of release after the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to adults with income at or below 100% FPL, resulting in 36% of recently incarcerated adults having coverage in the month of release. For Medicaid expansion states, this estimate can inform policy discussion about the relative need for, and value of, additional intervention(s) to increase coverage during the reentry period. For nonexpansion states, it provides an estimate of what they may anticipate, in terms of Medicaid coverage rates, following an eligibility expansion that applies to this highly vulnerable group. Nonexpansion states continue to debate the merits of Medicaid expansion. 28 This finding contributes to a more comprehensive valuation of a Medicaid expansion for the state's population and policy priorities.

Among the sample as a whole, implementation of the enrollment assistance program was associated with an additional 25 percentage point increase in enrollment in the month of release. The sharp increase in the likelihood of applying for Medicaid before release after its implementation suggests a possible explanation as there was no such change after implementation of the eligibility expansion. Reducing the transaction costs of enrolling in Medicaid (eg, travel and time) is associated with higher rates of enrollment in other populations. 29 , 30 Providing enrollment assistance on‐site before individuals face the many practical challenges of reentering the community from prison may be a means of doing so for this population. The large magnitude of change in enrollment associated with the assistance program also reinforces the potential impact of the SUPPORT Act's Reentry Provision that encourages states to implement enrollment assistance for adults leaving correctional facilities. An important next research step is to assess the degree to which Medicaid coverage upon release improves health care access and outcomes.

At the conclusion of this study, approximately one‐third of individuals released were not enrolled in Medicaid. Several explanations may account for this incomplete enrollment. According to the WI DOC, roughly 10% of the incarcerated population are income ineligible for Medicaid. Additionally, individual preferences and priorities may play a role. There may also be opportunities for program modification. For example, we observe relatively higher rates of enrollment among individuals released from medium security facilities relative to minimum security facilities. Additionally, the variation across facilities in the proportion of adults enrolled in Medicaid in the month of release after both policies were in place suggests an avenue for further inquiry (Figure S1 in Appendix S1). Other states have engaged peers as resources 31 and health insurance navigators in their enrollment assistance programs. 32 The increasing availability of prerelease enrollment assistance programs, and the variation in their designs, creates a timely opportunity to identify the features that are most effective.

Medicaid coverage upon release is critical for individuals that may require health care in the immediate days postrelease such as individuals with substance use disorders, particularly opioid use disorder. Thus, it is important to determine the extent to which enrollment assistance programs are effective for this population. These programs are critical whether they support new enrollment or activation of suspended enrollment. While we could not identify individuals with OUD specifically, we found that the expansion of Medicaid eligibility and implementation of enrollment assistance was associated with similar gains in Medicaid enrollment for those with a history of substance use. This finding suggests that a relatively low‐intensity intervention may work equally well for a population that is increasingly at the center of enrollment and care transition initiatives nationwide. 33

Our study has limitations. Our definition of a history of substance use derives from the COMPAS tool's substance use treatment need score. This score has not been validated relative to a clinical or diagnostic tool. However, the prevalence of history of substance use that we observe in our sample is consistent with published estimates within state prison populations suggesting reasonable face validity. 34 We required an incarceration duration of at least 30 days; thus, our results may not generalize to individuals who have less opportunity to participate in the discharge process. Additionally, this study's results may understate the impact of an ACA Medicaid expansion on Medicaid enrollment for recently incarcerated adults. Medicaid expansions under the ACA have an income eligibility threshold of 138% FPL; however, the Wisconsin expansion limited eligibility to adults with income below 100% FPL. Thus, in the states operating ACA expansions, we might expect higher Medicaid enrollment.

5. CONCLUSIONS

States are increasingly exploring strategies to connect individuals leaving prisons and jails with needed health care services. 33 Ensuring Medicaid enrollment upon reentry to the community is a foundational step in that process. Adults leaving correctional facilities face different enrollment opportunities depending on the Medicaid expansion status of their state, and the availability and type of enrollment assistance at their correctional facility. Without effective enrollment strategies in place, coverage rates for recently incarcerated adults will likely remain low. For states and jurisdictions that seek to ensure coverage for recently incarcerated adults, our findings demonstrate the promise of two available strategies to do so.

Supporting information

Author matrix

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: We gratefully acknowledge the excellent data analytical support that Krista Bryz‐Gornia, Natalia Serna Borrero, and Karla Hernandez Romero provided to this study, and funding for this research from the Wisconsin Partnership Program and the NIDA (3UG3DA044826‐02S). The authors of this article are solely responsible for the content therein. The authors would like to thank the Wisconsin Department of Corrections and Department of Health Services, for the use of data for this analysis, but these agencies do not certify the accuracy of the analyses presented.

Burns ME, Cook ST, Brown L, Tyska S, Westergaard RP. Increasing Medicaid enrollment among formerly incarcerated adults. Health Serv Res. 2021;56:643–654. 10.1111/1475-6773.13634

REFERENCES

- 1. Fazel S, Yoon IA, Hayes AJ. Substance use disorders in prisoners: an updated systematic review and meta‐regression analysis in recently incarcerated men and women. Addiction. 2017;112(10):1725‐1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bronson J, Berzofsky M.Indicators of mental health problems reported by prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2017. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/imhprpji1112.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Westergaard RP, Spaulding AC, Flanigan TP. HIV among persons incarcerated in the USA: a review of evolving concepts in testing, treatment, and linkage to community care. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26(1):10‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mallik‐Kane K, Visher CA. Health and Prisoner Reentry: How Physical, Mental, and Substance Abuse Conditions Shape the Process of Reintegration. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, Perkins T, Richie BE. Coming home from jail: the social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9 Suppl):S191‐S202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frank JW, Andrews CM, Green TC, Samuels AM, Trinh TT, Friedman PD. Emergency department utilization among recently released prisoners: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2013;13:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):592‐600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lim S, Seligson AL, Parvez FM, et al. Risks of drug‐related death, suicide, and homicide during the immediate post‐release period among people released from New York city jails, 2001–2005. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(6):519‐526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang EA, Clemens HS, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kessell E, Kushel MB. Engaging individuals recently released from prison into primary care: a randomized trial. Am J Pub Health. 2012;102(9):e22‐e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Substance Use‐Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115–217, 132 Stat. 3894 (October 24, 2018).

- 11. Cuellar AE, Cheema J. As roughly 700,000 prisoners are released annually, about half will gain health coverage and care under federal laws. Health Aff. 2012;31(5):931‐938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Winkelman TN, Kieffer EC, Goold SD, Morenoff JD, Cross K, Ayanian JZ. Health insurance trends and access to behavioral healthcare among justice‐involved individuals‐United States, 2008–2014. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(12):1523‐1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saloner B, Bandara SN, McGinty EE, Barry CL. Justice‐involved adults with substance use disorders: coverage increased but rates of treatment did not in 2014. Health Aff. 2016;35(6):1058‐1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beck A.Medicaid enrollment programs offer hope to formerly incarcerated individuals and savings for states. 2020. February 2020. In: Health Affairs Blog; [Internet]. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200218.910350/full/. Accessed February 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bandara SN, Huskamp HA, Riedel LE, et al. Leveraging the affordable care act to enroll justice‐involved populations in medicaid: state and local efforts. Health Aff. 2015;34(12):2044‐2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gifford E, Foster EM. Provider‐level effects on psychiatric inpatient length of stay for youth with mental health and substance abuse disorders. Med Care. 2008;46(3):240‐246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Establishing and maintaining Medicaid eligibility upon release from public institutions. Rockville, MD; 2010. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 10–4545. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wenzlow AT, Ireys HT, Mann B, Irvin C, Teich JL. Effects of a discharge planning program on Medicaid coverage of state prisoners with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(1):73‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morrissey JP, Domino ME, Cuddeback GS. Expedited Medicaid enrollment, mental health service use, and criminal recidivism among released prisoners with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(8):842‐849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Looney A, Turner N. Work and opportunity before and after incarceration. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution; 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/research/work‐and‐opportunity‐before‐and‐after‐incarceration/. Accessed June 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Western B, Smith N. Formerly incarcerated parents and their children. Demography. 2018;55(3):823‐847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown PR, Thornton K. Technical report on lessons learned in the development of the institute for research on Poverty's Wisconsin Administrative Data Core. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; 2020. https://www.irp.wisc.edu/wp/wp‐content/uploads/2020/08/TechnicalReport_DataCoreLessons2020.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang CS. Local labor markets and criminal recidivism. Jrnl Public Econ. 2017;147:16‐29. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Northpointe Institute for Public Management Inc . Measurement & treatment implications of COMPAS core scales. March 30, 2009. https://www.michigan.gov/documents/corrections/Timothy_Brenne_Ph.D._Meaning_and_Treatment_Implications_of_COMPA_Core_Scales_297495_7.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2020.

- 25. Northpointe Inc . Practitioner's guide to COMPAS core. 2019. http://www.northpointeinc.com/files/technical_documents/FieldGuide2_081412.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2020.

- 26. Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and Quasi‐Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross‐Degnan D. Segmented regression analysisof interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Therapeutics. 2002;27:299‐309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gifford K, Ellis E, Coulter EB, et al. States Focus on Quality and Outcomes: Results from a 50‐State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jia LY, Yuan BB, Huang F, Lu Y, Garner P, Meng QY. Strategies for expanding health insurance coverage in vulnerable populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD008194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wolfe B, Scrivner S. The devil may be in the details: how the characteristics of SCHIP programs affect take‐up. J Policy Anal Manage. 2005;24(3):499‐522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Janetta J, Wishner JB, Peters R. Ohio's Medicaid pre‐release enrollment program: Medicaid areas of flexibility to provide covrage and care to justice‐involved populations. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2017. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/88051/ohio_medicaid_1.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wishner JB, Janetta J. Connecting criminal justice‐involved people with medicaid coverage and services: innovative strategies from Arizona. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2018. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/97036/connecting_criminal_justice‐involved_people_with_medicaid_coverage_and_services_innovative_strategies_from_arizona.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. State Health Access Data Assistance Center . Targeting justice‐involved populations through 1115 Medicaid waiver initiatives: implementation experiences of three states. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota School of Public Health; 2019. https://www.shadac.org/publications/justice‐involved‐1115‐Waiver‐Initiatives. Accessed January 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bronson J, Zimmer S, Berzofksy M.Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007–2009. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics of the U.S. Department of Justice; 2017. Contract No.: NCJ 250546. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/duadaspji0709.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Author matrix

Appendix S1