Abstract

Introduction

This is a report of a systematic review of the safety and efficacy of naltrexone or naltrexone/bupropion on weight loss.

Material and methods

The databases Medline, PubMed, and Embase as well as the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register for randomized controlled trials were searched for studies published from January 1966 to January 2018. A meta-analysis, randomised controlled trials, controlled trials, uncontrolled trials, cohort studies and open-label studies were analysed.

Results

Of 191 articles, 14 fulfilled the inclusion criteria: 1 meta-analysis, 10 randomized controlled trials, and 3 studies without randomization were found. In these studies, the efficacy and safety of naltrexone/bupropion in obesity were analysed. In the majority of these studies, patients with at least 5% or 10% weight loss, as a primary outcome, were investigated. Generally, naltrexone/bupropion treatment can be a promising therapy for obese patients, including when combined with mental health treatment.

Conclusions

Based on these studies, it can be said that naltrexone/bupropion treatment is effective in the weight loss of overweight subjects. The naltrexone/bupropion treatment was well tolerated by the patients, and side effects were rarely reported.

Keywords: obesity, therapy, naltrexone, bupropion, systematic review

Introduction

In recent years, obesity in adults and children has been increasing and has started to become a leading cause of death. It is one of the greatest public health threats in Europe and the world [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) assessed that excessive weight is the cause of death of almost 3 million people and brings about disability amongst 35.8 million people annually [2]. In adults, obesity criteria include a body mass index (BMI) over 30 kg/m2 [3].

Obesity is a chronic and multifactorial disease involving the accumulation of subcutaneous and visceral fat, which gives rise to the development of many cardiometabolic diseases [4]. Diabetes, stroke and heart disease are associated with obesity. Unfortunately, many of the complications brought by obesity lead to death, which might be averted through a change in lifestyle. There are different theories about obesity’s mechanisms, such as inflammation, inflammasome activation, insulin resistance, adipokine balance, and abnormalities in lipid metabolism and endothelial function [4]. Some of the newest data have shown that obesity is characterized by low-grade chronic inflammation caused by increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines by the macrophages and adipocytes present in adipose tissue [5].

Almost all obese patients should have additional behavioural treatment. There are many programmes that focus on behavioural and lifestyle modifications such as the Diabetes Prevention Programme (DPP) run by the National Health Service (NHS) in the U.K. or the Look AHEAD Action for Health in Diabetes operated by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the U.S. [6]. However, lifestyle modification and weight loss alone are usually ineffectual [7].

Another factor responsible for weight gain of pharmacological action is blockage of 5HT2c serotonin receptors by several first-generation and the majority of second-generation antipsychotics. It is known that 5HT2c receptors are engaged in appetite regulation [8, 9].

Moreover, it was reported that an opioid receptor blocker blocked the central opioid receptors, thus decreasing the preference for toothsome foods [10].

In 2015, the first clinical practice guidelines for the pharmacologic management of obesity were published. These directives were created by the Endocrine Society (a task force of experts), the European Society of Endocrinology and the Obesity Society [11]. However, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has endorsed only a few medicaments for the treatment of obesity. One of the newest medications is the combination of bupropion and naltrexone [6].

Naltrexone is a μ-opioid receptor antagonist commonly used for treatment of opioid addiction and alcohol dependence [12]. Possibly, naltrexone reduces food consumption through the blockage of β-endorphin action at the μ-opioid receptor as well as preventing autoinhibition of pro-opiomelanocortin neurons [13]. The first pass of naltrexone’s metabolism is 5–40% oral bioavailability. Both primal naltrexone and the 6-β-naltrexol metabolite are active forms. Mostly, naltrexone is eliminated by the kidneys. Retrospectively, the elimination half-life of naltrexone and 6-β-naltrexol is long – 4–13 h [13–16].

In turn, bupropion is a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor which is currently prescribed for treatment of depression, seasonal affective disorder and also as support during smoking cessation [17]. Dopamine and noradrenaline stimulate pro-opiomelanocortin neurons in the hypothalamus. The mean elimination half-life of bupropion is very long – 21 ±9 h. It is metabolized by humans, resulting in three active metabolites: hydroxybupropion, threohydrobupropion and erythrohydrobupropion. Eighty-seven percent of bupropion is eliminated by the kidneys and 10% in faeces [14, 15, 18].

The effect of the combination of naltrexone and bupropion is not completely clear. There is a theory that naltrexone could have an influence on the neurological reward pathways in the brain, while bupropion suppresses the appetite [12].

The purpose of the current work was to systematically present the safety and effectiveness of naltrexone or a combination of naltrexone and bupropion for weight loss in patients with antipsychotic-associated obesity, in comparison with patients suffering from overweight without any antipsychotic treatment.

Material and methods

Study population

The study population consisted of adult patients undergoing naltrexone or naltrexone/bupropion treatment.

Study design

The researchers analysed the relevant meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled trials, uncontrolled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies. Studies with a population of fewer than 5 patients were excluded.

Intervention

As an intervention, we included therapy using naltrexone or a combination of naltrexone and bupropion.

Outcome measure

To assess the safety of the therapy, we analysed the number of patient discontinuations due to adverse events in the treatment group compared to those in the placebo or control group. We also analysed the number of significant adverse events reported in the studied groups.

Methodological quality

We assessed the quality of all articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. To evaluate the quality of RCTs, we used the Jadad scale, the impact factor of the journal in which the trial was published, and evidence of statistics using intention-to-treat analysis. The Jadad scale [19] contains two questions to determine appropriate randomization and study masking, along with questions that evaluate the reporting of withdrawals and dropouts that require a yes or no response. Five total points are possible on the scale, in which a higher score indicates superior quality. We also used the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool to assess the risk of bias of RCTs [20].

Categorizing evidence

We categorized evidence according to the study design, using a hierarchy of evidence in descending order according to quality [21] and reviewed the highest level of available evidence for each intervention in detail.

Literature search

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts for relevance. The search included four electronic databases, namely, Medline, PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for studies reporting meta-analyses, RCTs, controlled trials, uncontrolled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies for therapy of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). We restricted our search to studies published between January 1966 and January 2018. Only English-language articles were included. We searched for the following terms: ‘obesity’ OR ‘overweight’ AND ‘naltrexone/bupropion’.

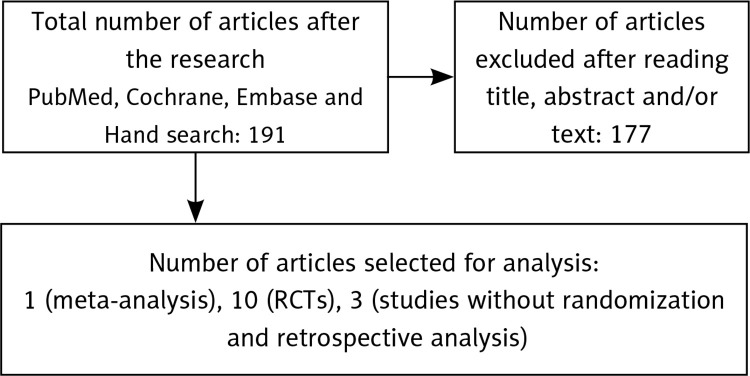

The search of PubMed, the Cochrane Database, and Embase produced 191 articles, most of which derived from PubMed and all of whose titles and abstracts we read. It was possible to exclude 177 articles, none of which fulfilled the search criteria. After reading the full texts, we considered 14 articles: 1 meta-analysis, 10 RCTs, 3 studies without randomization and retrospective analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for articles researching efficacy of naltrexone for weight loss in adult patients

RCTs – randomized controlled trials.

Publication bias

We performed data extraction for all 14 full texts, not blinded to author or journal, using a predefined extraction sheet (available upon request). The type of information extracted included first author, publication year, quality assessment of the manuscript, mean age of participants, sex proportion, characteristics of patient treatment, type of comparator, drug dose, number of participants in active and control groups, and outcome measure used to assess efficacy and safety.

Results

Meta-analysis

To date, only one meta-analysis was found analysing the efficacy of naltrexone in obesity [22]. In this study, naltrexone was one of five agents included in the meta-analysis. Generally, as a primary outcome, the studies found the proportion of patients with at least 5% weight loss and at least 10% weight loss, the magnitude of decrease in weight and discontinuation of therapy because of adverse events at 1 year. In this meta-analysis, participants had at least 5% weight loss, with 55% taking naltrexone/bupropion. Moreover, naltrexone/bupropion was associated with a significant amount of weight loss (5.0 kg) compared with the placebo (control group). However, compared with placebo, naltrexone/bupropion was associated with the highest odds of adverse event-related treatment discontinuation [22]. More specific information is included in Table I.

Table I.

Meta-analysis of efficacy of naltrexone for weight loss in adult patients

| Author (year), journal, title | Quality | No. of patients | Inclusion criteria | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome measure | Efficacy assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khera R et al. (2016) Journal: JAMA Title: Association of Pharmacological Treatments for Obesity With Weight Loss and Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis |

IF: 7.48 (2015) Category of evidence: Ia Jadad: – Cochrane risk of bias: – |

N = 29018 n = 2508 (naltrexone/bupropion studies) |

Database: MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane Central from inception to March 23, 2016; clinical trial registries Time frame: to March 23, 2016 |

Naltrexone/bupropion | Placebo | Proportions of patients with at least 5% weight loss and at least 10% weight loss Magnitude of decrease in weight Discontinuation of therapy due to adverse events at 1 year |

Proportion of patients with at least 5% and at least 10% weight loss: naltrexone/bupropion with an OR of 3.96 (95% CrI: 3.03–5.11) Weight loss in excess of placebo naltrexone/bupropion, 5.0 kg (95% CrI: –5.94 to –3.96 kg) Probability of achieving at least 5%weight loss naltrexone/bupropion (SUCRA, 0.60) Naltrexone/bupropion (OR = 2.64; 95% CrI: 2.10–3.35; SUCRA, 0.23) was associated with the highest odds of being discontinued because of adverse events |

Randomized controlled trials

We included ten RCTs. One article focused on major adverse cardiovascular events in overweight and obese patients [23]. In this study, the time to the first confirmed occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) occurred in 90 (2.0%) in the naltrexone/bupropion group. The components of the primary composite outcome included occurrence of cardiovascular death in 17 naltrexone/bupropion-treated patients. Adverse events occurred in 543 patients (5.2%) [23].

Four studies [24–27], as a primary outcome, presented percent weight change at week 56 and proportion achieving ≥ 5% weight loss at week 56 [24–27]. Generally, in these studies, naltrexone/bupropion resulted in significantly greater weight change at week 56 and a greater proportion of patients achieving ≥ 5% weight loss compared with the placebo [24–27].

In the newest paper, from 2017 [28], the authors presented, as a primary outcome, the percent change in body weight from baseline (day 1) to week 26. They used the standard dose of naltrexone/bupropion connected with comprehensive lifestyle intervention (CLI), a programme containing diet and exercise education. The results were promising. Subjects lost significantly more weight (8.52%) compared to the control group.

One author investigated the cortisol response to naltrexone (cortisol levels at 3 PM and 4 PM on the naltrexone day were higher) and nausea responses to naltrexone. It was found that more patients reported experiencing nausea on the naltrexone day) [29]. The changes at 56 weeks in the quality of life were measured by the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite) questionnaire [30]. This instrument showed that improvements in IWQOL-Lite Total Score were more significant in subjects treated with naltrexone/bupropion [30].

From the psychiatric point of view, two RCTs [31, 32] were significant. These studies focused on the effect of naltrexone on body weight in patients with anti-psychotic treatment. In one, the patients in the naltrexone/bupropion group had significant weight loss (–3.40 kg) compared with weight gain (+1.37 kg) in the patients in the placebo group [31]. In the second study, there was no significant change in BMI. However, it showed that the olanzapine + naltrexone group displayed a significant decrease in fat and increase in fat-free mass, which suggests that the addition of naltrexone to olanzapine may attenuate olanzapine-induced body fat mass gain [32]. More details are included in Table II.

Table II.

Randomized controlled trials of efficacy of naltrexone for weight loss in adult patients

| Author (year), journal, title | Quality | No. of patients | Inclusion criteria | Intervention Comparator | Active N Age % female | Primary outcome | Efficacy assessment Effect size – ES (95% CI) | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halseth A et al. (2017) Journal: Obesity Title: Method of use study of naltrexone sustained release (SR)/bupropion SR on body weight in individuals with obesity |

IF: 3.873 (2015) Category of evidence: Ib Jadad: 4/5 Cochrane risk of bias: low risk of bias |

N = 242 | Adult male and female subjects, aged 18 to 60 years, had either obesity (body mass index [BMI] 30–45 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI 27–45 kg/m2) with dyslipidaemia and/or controlled hypertension |

Naltrexone/bupropion (NB) 32 mg/day / 360 mg/day for 26 weeks and commercially available comprehensive lifestyle intervention (CLI) programme Usual care (diet and exercise education and recommendations from the study site) |

N = 153 Age = 46.1 ±9.66 Female = 81.7% |

Percent change in body weight from baseline (day 1) to week 26 |

At week 26 NB + CLI subjects lost significantly more weight than usual care subjects (8.52% difference; p < 0.0001) | The most frequent adverse events (AEs) that led to discontinuation of NB for the two groups combined included nausea (7.0%), anxiety (2.1%), headache (1.7%), dizziness (1.2%), and insomnia (1.2%) |

| Nissen SE et al. (2016) Journal: JAMA Title: Effect of Naltrexone-Bupropion on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Overweight and Obese Patients With Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Randomized Clinical Trial |

IF: 7.48 (2015) Category of evidence: Ib Jadad: 4/5 Cochrane risk of bias: low risk of bias |

N = 8910 | Patients aged 50 years or older (women) or 45 years or older (men), BMI 27–50 kg/m2, and having a waist circumference of 88 cm or more (women) or 102 cm or more (men) |

Naltrexone/bupropion 32 mg/day / 360 mg/day Placebo |

N = 4456 Age = 61.1 ±7.27 Female = 54.7% |

Time from treatment randomization to the first confirmed occurrence of: major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) |

Time to first MACE, occurred in 192 patients, 102 (2.3%) in the placebo group and 90 (2.0%) in the naltrexone/bupropion group (HR = 0.88; 99.7% CI: 0.57–1.34) |

Adverse event occurred in 543 patients (5.2%) |

| Defined as cardiovascular death |

The components of the primary composite outcome included cardiovascular death in 34 placebo-treated patients (0.8%) and 17 naltrexone/bupropion-treated patients (0.4%; HR = 0.50; 99.7% CI: 0.21–1.19) |

|||||||

| Nonfat stroke | Nonfatal stroke occurred in 19 patients (0.4%) in the placebo group and 21 (0.5%) in the naltrexone/bupropion group (HR = 1.10; 99.7% CI: 0.44–2.78) |

|||||||

| Nonfat myocardial infarction |

Nonfatal myocardial infarction occurred in 54 patients (1.2%) in the placebo group and 54 (1.2%) in the naltrexone/bupropion group (HR = 1.00; 99.7% CI: 0.57–1.75) |

|||||||

| Kolotkin RL et al. (2015) Journal: Clinical Obesity Title: Patient-reported quality of life in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone/bupropion for obesity |

IF: no data (2015) Category of evidence: Ib Jadad: 4/5 Cochrane risk of bias: unclear risk of bias |

N = 3362 | Patients with BMI 30–45 kg/m2, or a BMI 27–45 kg/m2 and controlled hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia | Naltrexone/bupropion 32 mg/day / 360 mg/day Placebo |

N = 2043 Age = 46 ±11 Female = 81% |

Changes at 56 weeks in quality of life, measured by the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite) questionnaire | Improvements in IWQOL-Lite Total Score were greater in subjects treated with NB32 (11.9 points [SE = 0.3]) vs. placebo (8.2 points [SE = 0.3]; p < 0.001), corresponding to weight reductions of 7.0% (SE = 0.2) and 2.3% (SE = 0.2) | Adverse events: the most frequently reported being nausea, constipation, headache and vomiting |

| Mason AE et al. (2015) Journal: Apetite Title: Acute responses to opioidergic blockade as a biomarker of hedonic eating among obese women enrolled in a mindfulness-based weight loss intervention trial |

IF: 1.47 (2016) Category of evidence: Ib Jadad: 2/5 Cochrane risk of bias: unclear risk of bias |

N = 88 | BMI of 30–45.9 kg/m2, abdominal obesity (female waist circumference > 88 cm), and age 18 or older | All participants ingested the placebo and the 50 mg naltrexone |

N = 88 Age = 46.7 ±13.2 Female = 100% |

Cortisol responses | Cortisol levels at 1 PM on the placebo day (median = 4.35) and naltrexone day (median = 3.70) were not statistically significantly different, Z = –1.29, p = 0.20 Cortisol levels at 3 PM on the naltrexone day (median = 3.87) were higher than those on the placebo day (median = 2.19), Z = 4.25, p < 0.001 Similarly, cortisol levels at 4 PM on the naltrexone day (median = 4.63) were higher than those on the placebo day (median = 1.95), Z = 5.70, p < 0.001 |

Adverse event: nausea |

| Nausea responses | Significantly more women reported experiencing nausea on the naltrexone day (n = 38, 43.2%) than on the placebo day (n = 15, 17.0%; p < 0.001) |

|||||||

| Tek C et al. (2014) Journal: J Clin Psychopharmacol Title: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of naltrexone to counteract antipsychotic-associated weight gain: proof of concept |

IF: 2.38 (2014) Category of evidence: Ib Jadad: 3/5 Cochrane risk of bias: unclear risk of bias |

N = 24 | Overweight women between the ages of 18–70 who met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, based on SCID | Naltrexone (NTX) 25 mg/day Placebo |

N = 11 Age = 50.0 ±9.6 Female = 100% |

Change in body weight from baseline | Patients in the NTX group had significant weight loss (–3.40 kg) compared with weight gain (+1.37 kg) in the patients in the placebo group The subjects assigned to NTX had a significant reduction in BMI (–1.37; CI: –2.054 to –0.68; F = 15.86; p = 0.001) vs. that of PLA (0.57; CI: –0.79 to –1.22) after the intervention |

The medication did not produce any adverse change in psychiatric symptoms and was well tolerated |

| Taveira TH et al. (2014) Journal: J Psychopharmacol Title: The effect of naltrexone on body fat mass in olanzapine-treated schizophrenic or schizoaffective patients: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study |

IF: 2.79 (2015) Category of evidence: Ib Jadad: 3/5 Cochrane risk of bias: unclear risk of bias |

N = 30 | Patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder on a stable dose of olanzapine (OLZ) (≥ 5 mg/day and ≤ 30 mg/day), BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 plus one symptom of metabolic syndrome (i.e. hypertension, dyslipidaemia or fasting blood) glucose > 125 mg/dl | Naltrexone (50 mg/day) Placebo |

N = 14 Age = 43.6 ±11.2 Female = 37.5% |

The change in BMI at 12 weeks | No significant change in BMI. However, the OLZ + NTX group displayed a significant decrease in fat and increase in fat-free mass. The group-by-time interaction showed a significant increase in fat-free mass in the NTX group over time (p = 0.03) without significant group (p = 0.22) or time effects (p = 0.20) | No participants reported that they discontinued the study due to adverse side effects |

| Hollander P et al. (2013) Journal: Diabetes Care Title: Effects of naltrexone sustained-release/bupropion sustained-release combination therapy on body weight and glycaemic parameters in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes |

IF: 5.00 (2013) Category of evidence: Ib Jadad: 4/5 Cochrane risk of bias: low risk of bias |

N = 505 | Smoking or non-smoking men and women with type 2 diabetes, aged 18–70 years, with a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 and ≤ 45 kg/m2, HbA1c between 7% (53 mmol/mol) and 10% (86 mmol/mol), and fasting blood glucose < 270 mg/dl | Naltrexone/bupropion 32 mg/day / 360 mg/day Placebo |

N = 335 Age = 54.0 ±9.1 Female = 58.2% |

Percent change in body weight from baseline to week 56 compared with placebo | NB resulted in significantly greater weight reduction (–5.0 vs. –1.8%; p < 0.001) and compared with placebo | Adverse events: nausea (withdrawal 9.6%), constipation, vomiting, diarrhoea Incidence of serious adverse events was low (3.9% for NB and 4.7% for placebo) |

| Percentage of participants achieving ≥ 5% reduction in body weight from baseline to week 56 compared with placebo | NB resulted in significantly greater weight proportion of patients achieving ≥ 5% weight loss (44.5 vs. 18.9%, p < 0.001) | |||||||

| Apovian CM et al. (2013) Journal: Obesity (Silver Spring) Title: A Randomized, Phase 3 Trial of Naltrexone SR/Bupropion SR on Weight and Obesity-related Risk Factors (COR-II) |

IF: 5.18 (2013) Category of evidence: Ib Jadad: 5/5 Cochrane risk of bias: low risk of bias |

N = 1496 | Patients with BMI 30–45 kg/m2, or a BMI 27–45 kg/m2 and controlled hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia | 32 mg/day naltrexone SR + 360 mg/day bupropion SR (NB32) Placebo |

N=1001 Age= 44.3 ±11.2 Female = 84.6% |

Percent weight change | Significantly (p < 0.001) greater weight loss was observed with NB32 versus placebo at week 28 (–6.5% vs. –1.9%) and week 56 (–6.4% vs. –1.2%) |

Most common adverse event: nausea Discontinuations in both groups during the first 8 weeks of the study, with more discontinuations, particularly because of AEs, occurring with NB |

| Proportion achieving ≥ 5% weight loss at week 28 | More NB32-treated participants (p < 0.001) experienced ≥5% weight loss versus placebo at week 28 (55.6% vs. 17.5%) and week 56 (50.5% vs. 17.1%) | |||||||

| Wadden TA et al. (2011) Journal: Obesity (Silver Spring) Title: Weight loss with naltrexone SR/bupropion SR combination therapy as an adjunct to behaviour modification: the COR-BMOD trial |

IF: 4.41 (2011) Category of evidence : Ib Jadad: 5/5 Cochrane risk of bias: low risk of bias |

N = 793 | Patients 18–65 years of age who had a BMI of 30–45 kg/m2, or a BMI of 27–45 kg/m2 in the presence of controlled hypertension and/or dyslipidaemia | 32 mg/day naltrexone SR + 360 mg/day bupropion SR (NB32) Placebo |

N = 591 Age = 45.9 ±10.4 Female = 89.3% |

Percent weight change at week 56 | At week 56, participants treated with placebo + behavior modification (BMOD) lost 5.1 ±0.6% of initial weight, compared with a significantly (p < 0.001) greater 9.3 ±0.4% for those who received NB32 + BMOD | Presents AEs that occurred in ≥ 5% of participants in either treatment group and with greater incidence in NB32 + BMOD than in placebo + BMOD Nausea in 34.1% of participants treated by NB32 + BMOD reporting at least one event, compared to 10.5% for placebo + BMOD (p < 0.001) Others: constipation, dizziness, dry mouth, tremor, abdominal pain, and tinnitus occurred more often in the NB32 + BMOD group than in placebo + BMOD |

| Proportion achieving ≥ 5% weight loss at week 56 | The proportions of participants who achieved ≥ 5%, ≥ 10%, and ≥ 15% reductions in baseline weight were greater with NB32 + BMOD than with placebo + BMOD (p < 0.001) | |||||||

| Greenway FL et al. (2011) Journal: Lancet Title: Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial |

IF = 8.56 (2010) Category of evidence: Ib Jadad: 5/5 Cochrane risk of bias: low risk of bias |

N = 1742 | Men and women aged 18–65 years who had a BMI of 30–45 kg/m2 and uncomplicated obesity or BMI 27–45 kg/m2 with dyslipidaemia or hypertension | 32 mg/day naltrexone SR + 360 mg/day bupropion SR (NB32) 16 mg/day naltrexone SR + 360 mg/day bupropion SR (NB32) Placebo |

n = 583 Age = 44.4 ±11.3 Female = 85% n = 578 Age = 44.4 ±11.1 Female = 85% |

Percent weight change at week 56 | Mean change in body weight was –1.3% (SE = 0.3) in the placebo group, –6.1% (0.3) in the naltrexone 32 mg plus bupropion group (p < 0.0001 vs. placebo) and –5.0% (0.3) in the naltrexone 16 mg plus bupropion group (p < 0.0001 vs. placebo) | Nausea (naltrexone 32 mg plus bupropion, 171 participants [29.8%]; naltrexone 16 mg plus bupropion, 155 [27.2%]; placebo, 30 [5.3%]) Headache, constipation, dizziness, vomiting, dry mouth were also more frequent in the naltrexone plus bupropion groups than placebo |

| Proportion achieving ≥ 5% weight loss at week 56 | 84 (16%) participants in placebo had a decrease in body weight of 5% or more compared with 226 (48%) assigned to naltrexone 32 mg plus bupropion (p < 0.0001 vs. placebo) and 186 (39%) assigned to naltrexone 16 mg plus bupropion (p < 0.0001 vs. placebo) |

Studies without randomization and retrospective analysis

Three studies without randomization investigating the effectiveness of naltrexone were found. [33–35]. In one study [33], the Reward-Based Eating Drive (RED) scale (non-significant associations with naltrexone) and food-craving intensity (non-significant difference between naltrexone and placebo) were investigated as a primary outcome. Another study investigated the cortisol responses to naltrexone (increased on the naltrexone day) and nausea responses to naltrexone (mean level of nausea severity was 1.23 ±1.3) [34]. The third article focused only as a secondary outcome on the percent change from baseline in body weight (increased slightly in continuous abstainers) [35]. In all three studies, the most common adverse event was nausea [33–35]. More details are included in Table III.

Table III.

Non-randomized studies of efficacy of naltrexone for weight loss in adult patients

| Author (year), journal, title | Quality | No. of patients | Inclusion criteria | Intervention comparator | Active N Age % female | Primary outcome | Efficacy assessment Effect size − ES (95% CI) | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mason AE et al. (2015) Journal: Eating Behaviors Title: Putting the brakes on the “drive to eat”: Pilot effects of naltrexone and reward-based eating on food cravings among obese women |

IF: 2.23 (2015) Category of evidence: IIa Jadad: 0/5 |

N = 44 | Female sex, overweight status (30 ≤ body mass index [BMI] ≤ 40 kg/m2), and age of 20–45 years | Placebo 50 mg naltrexone 25 mg naltrexone 1:00 PM (after lunch) on days 1 (placebo), 4 (25 mg naltrexone), 7 (placebo), 10 (50 mg naltrexone), and 4 weeks after day 10 (50 mg naltrexone) |

N = 44 Age: 32.7 ±7.6 Female: 100% |

Reward-Based Eating Drive (RED) scale | Significant positive associations between RED and craving intensity on each placebo day (p = 0.017, p = 0.034) and non-significant associations on naltrexone days |

Adverse event: nausea |

| Food-craving intensity | Placebo, 25 mg, and 50 mg doses did not differentially impact craving intensity Revealed a dose RED interaction such that the association between RED and craving intensity differed between the placebo and 50 mg doses [b = –0.06, SE(b) = 0.02, 95% CI: –0.099, –0.012, p = 0.012] The association between RED and craving intensity did not significantly differ between the placebo and 25 mg doses |

|||||||

| Daubenmier J et al. (2014) Journal: Appetite Title: A new biomarker of hedonic eating? A preliminary investigation of cortisol and nausea responses to acute opioid blockade |

IF: 0.34 (2014) Category of evidence: IIa Jadad: 0/5 |

N = 33 | Female with BMI between 25 and 40 kg/m2; pre-menopausal; no history of diabetes or cardiovascular disease, or active endocrinologic disorder |

Naltrexone (50 mg) |

N = 33 Age = 40.9 ±8.0 Female = 100% |

Cortisol responses to naltrexone | Cortisol decreased by 3.6 ±2.2 nmol/l between 1 PM and 4 PM on the control days (95% CI: 2.8–4.4; t(32) = 9.4, p < 0.001) and increased on the naltrexone day by 8.0 ±17.4 nmol/l (95% CI: 1.5–14.5; t(29) = 2.53, p = 0.02) between 1 PM and 4 PM |

Adverse event: nausea |

| Nausea responses to naltrexone | The mean level of nausea severity was 1.23 ±1.3 | |||||||

| Wilcox CS et al. (2010) Journal: Addict Behav Title: An open-label study of naltrexone and bupropion combination therapy for smoking cessation in overweight and obese subjects |

IF: 3.13 (2010) Category of evidence: IIb Jadad: 0/5 |

N = 30 | 18 to 65 years of age; BMI ≥ 27 and ≤ 45 kg/m2; smoking an average of ≥ 10 cigarettes/day in the preceding year with < 3 months of total abstinence; an expired CO concentration > 10 ppm; self-reported motivation to stop smoking of ≥ 7 on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 defined as highest motivation; at least moderate concern about gaining weight after quitting smoking (on a scale of 1–10, where a score of 5 indicates moderate weight gain is defined as at least 10 lbs); systolic blood pressure ≤ 140 mmHg; diastolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mmHg (a stable regimen of antihypertensive medications was allowed) | Naltrexone SR (8 mg)/bupropion SR (90 mg), with final daily doses of 32 mg/day naltrexone SR and 360 mg/day bupropion SR |

N = 30 Age = 42.5 ±11.3 Female = 53.3% |

As a secondary endpoint: percent change from baseline in body weight | Body weight did not significantly change in the entire population (0.4 ±3.0%, p = 0.555), but increased slightly in continuous abstainers (1.3 ±3.3%, p = 0.148) | Treatment-emergent adverse events with frequency ≥ 10% The combination of naltrexone and bupropion was generally well tolerated; the most common adverse events were nausea, insomnia, and constipation |

Discussion

Nowadays, obesity treatment goals include body weight reduction and weight maintenance after weight loss [36]. The basic strategy consists of an energy-reduced diet (of 500 kcal/day), introduction of physical activity, behavioural modifications or pharmacological treatment [36]. Moreover, it is probable that the gene therapy-based strategy in modulating metabolism and treating metabolic disorders will be the future of obesity treatment [37].

As a treatment option for obesity, naltrexone/bupropion has proved efficacious and safe. As a treatment for body weight in patients with antipsychotic treatment, this combination of medicaments is a subject with limited high-quality research (only two were found) [31, 32]. However, the results of the thirteen articles are promising for intervention with obese subjects after longitudinal treatment. Moreover, naltrexone/bupropion had an influence on cortisol increases [29]. Patients with higher cortisol levels may have greater reductions in food addiction symptoms [29]. This might be useful in the treatment of this group of patients.

In these evaluated studies, we noted enormous heterogeneity, including study protocol, population groups, the period of treatment and the main outcomes. Despite this fact, the heterogeneity might complicate the extrapolation of findings to obese subjects with antipsychotic treatment (only two from thirteen studies used mental health patients as a population) [31, 32]. The authors of the current study decided to include different studies to widen the point of view on the obesity problem. This may contribute to the deepening of the problem of obesity in patients with antipsychotic-associated weight gain in future research projects.

Naltrexone/bupropion treatment can be a promising therapy for obese patients and also for mental health treatment. Based on the above-mentioned studies, naltrexone/bupropion therapy also appears to be safe. Generally, the toleration of naltrexone/bupropion was good. The most common side effect was nausea. However, based on all of the studies, this choice of therapy should be individual, given entity sensitivity (adverse events caused dropouts).

Moreover, another study [38] showed that naltrexone/bupropion might be useful in reducing binge-eating symptoms related to major depressive disorder and obesity. The authors of that study investigated the relationship between change in eating behaviour and changes in weight, control of eating, and depressive signs. Improvement in eating symptoms was observed between 4 and 24 weeks.

However, another author demonstrated that naltrexone as an opioid-receptor antagonist influences pain tolerance. Also, he showed that naltrexone-induced changes in pain were correlated with depression scores [39].

In conclusion, our systematic review suggests that naltrexone/bupropion treatment is effective in the accomplishment of weight loss amongst overweight subjects. The naltrexone/bupropion treatment was well tolerated by the patients, and side effects were rarely reported.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dibaise JK, Foxx-Orenstein AE. Role of the gastroenterologist in managing obesity. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7:439–51. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2013.811061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Health Observatory . Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization; 2017. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/overweight/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Flegal KM. Changes in terminology for childhood overweight and obesity. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;25:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovren F, Teoh H, Verma S. Obesity and atherosclerosis: mechanistic insights. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sliwinska A, Kasinska MA, Drzewoski J. MicroRNAs and metabolic disorders – where are we heading? Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:885–96. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2017.65229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Look AHEAD Research Group The look AHEAD study: A description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity. 2006;14:737–52. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders KH, Kumar RH, Igel LI, Aronne LJ. Pharmacologic approaches to weight management: recent gains and shortfalls in combating obesity. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2016;18:36. doi: 10.1007/s11883-016-0589-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casey DE, Zorn SH. The pharmacology of weight gain with antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 7):4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marston OJ, Heisler LK. Targeting the serotonin 2C receptor for the treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:252–3. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeomans MR, Gray RW. Opioid peptides and the control of human ingestive behaviour. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:713–28. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al. Pharmacological management of obesity: an endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:342–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pucci A, Finer N. New medications for treatment of obesity: metabolic and cardiovascular effects. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:142–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenway FL, Whitehouse MJ, Guttadauria M, et al. Rational design of a combination medication for the treatment of obesity. Obesity. 2009;17:30–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenway FL, Dunayevich E, Tollefson G, et al. Comparison of combined bupropion and naltrexone therapy for obesity with monotherapy and placebo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4898–906. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith SR, Fujioka K, Gupta AK, et al. Combination therapy with naltrexone and bupropion for obesity reduces total and visceral adiposity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:863–6. doi: 10.1111/dom.12095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christou GA, Kiortsis DN. The efficacy and safety of the naltrexone/bupropion combination for the treatment of obesity: an update. Hormones. 2015;14:370–5. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gadde KM, Xiong GL. Bupropion for weight reduction. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:17–24. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verpeut JL, Bello NT. Drug safety evaluation of naltrexone/bupropion for the treatment of obesity. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:831–41. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.909405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available at: http://handbook.cochrane.org/ (accessed: September 15, 2015)

- 21.Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: developing guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:593–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7183.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khera R, Murad MH, Chandar AK, et al. Association of pharmacological treatments for obesity with weight loss and adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315:2424–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nissen SE, Wolski KE, Prcela L, et al. Effect of naltrexone-bupropion on major adverse cardiovascular events in overweight and obese patients with cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:990–1004. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollander P, Gupta AK, Plodkowski R, et al. Effects of naltrexone sustained-release/bupropion sustained-release combination therapy on body weight and glycemic parameters in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:4022–9. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, et al. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity-related risk factors (COR-II) Obesity. 2013;21:935–43. doi: 10.1002/oby.20309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wadden TA, Foreyt JP, Foster GD, et al. Weight loss with naltrexone SR/bupropion SR combination therapy as an adjunct to behavior modification: the COR-BMOD trial. Obesity. 2011;19:110–20. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:595–605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60888-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halseth A, Shan K, Walsh B, Gilder K, Fujioka K. Method of use study of naltrexone sustained release (SR)/bupropion SR on body weight in individuals with obesity. Obesity. 2017;5:338–45. doi: 10.1002/oby.21726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason AE, Lustig RH, Brown RR, et al. Acute responses to opioidergic blockade as a biomarker of hedonic eating among obese women enrolled in a mindfulness-based weight loss intervention trial. Appetite. 2015;91:311–20. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolotkin RL, Chen S, Klassen P, Gilder K, Greenway FL. Patient-reported quality of life in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone/bupropion for obesity. Clin Obes. 2015;5:237–44. doi: 10.1111/cob.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tek C, Ratliff J, Reutenauer E, Ganguli R, O’Malley SS. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of naltrexone to counteract antipsychotic-associated weight gaIn: proof of concept. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34:608–12. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taveira TH, Wu WC, Tschibelu E, et al. The effect of naltrexone on body fat mass in olanzapine-treated schizophrenic or schizoaffective patients: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:395–400. doi: 10.1177/0269881113509904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason AE, Laraia B, Daubenmier J, et al. Putting the brakes on the “drive to eat”: pilot effects of naltrexone and reward-based eating on food cravings among obese women. Eat Behav. 2015;19:53–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daubenmier J, Lustig RH, Hecht FM, et al. A new biomarker of hedonic eating? A preliminary investigation of cortisol and nausea responses to acute opioid blockade. Appetite. 2014;74:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilcox CS, Oskooilar N, Erickson JS, et al. An open-label study of naltrexone and bupropion combination therapy for smoking cessation in overweight and obese subjects. Addict Behav. 2010;35:229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blüher M. Conservative obesity treatment – when and how? Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2015;140:24–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-100426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao M, Liu D. Gene therapy for obesity: progress and prospects. Discov Med. 2014;17:319–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guerdjikova AI, Walsh B, Shan K, Halseth AE, Dunayevich E, McElroy SL. Concurrent improvement in both binge eating and depressive symptoms with naltrexone/bupropion therapy in overweight or obese subjects with major depressive disorder in an open-label, uncontrolled study. Adv Ther. 2017;34:2307–15. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0613-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price RC, Christou NV, Backman SB, Stone L, Schweinhardt P. Opioid-receptor antagonism increases pain and decreases pleasure in obese and non-obese individuals. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:3869–79. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]