Abstract

Background

Primary urethral carcinoma (PUC) is a rare genitourinary malignancy with a relatively poor prognosis. The aim of this study was to examine the impact of surgery on survival of patients diagnosed with PUC.

Methods

A total of 1544 PUC patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2016 were identified based on the SEER database. The Kaplan-Meier estimate and the Fine and Gray competing risks analysis were performed to assess overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific mortality (CSM). The multivariate Cox regression model and competing risks regression model were used to identify independent risk factors of OS and cancer-specific survival (CSS).

Results

The 5-yr OS was significantly better in patients who received either local therapy (39.8%) or radical surgery (44.7%) compared to patients receiving no surgery of the primary site (21.5%) (p < 0.001). Both local therapy and radical surgery were each independently associated with decreased CSM, with predicted 5-yr cumulative incidence of 45.4 and 43.3%, respectively, compared to 64.7% for patients receiving no surgery of the primary site (p < 0.001). Multivariate analyses demonstrated that primary site surgery was independently associated with better OS (local therapy, p = 0.037; radical surgery, p < 0.001) and decreased CSM (p = 0.003). Similar results were noted regardless of age, sex, T stage, N stage, and AJCC prognostic groups based on subgroup analysis. However, patients with M1 disease who underwent primary site surgery did not exhibit any survival benefit.

Conclusion

Surgery for the primary tumor conferred a survival advantage in non-metastatic PUC patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-021-08603-z.

Keywords: Primary urethral carcinoma, Survival, SEER, Surgery

Background

Primary urethral carcinoma (PUC) is a rare genitourinary malignancy with a relatively poor prognosis [1–3]. In 2020, it was estimated that in the United States there are 3970 new diagnoses of cancer of the ureter and other urinary organs, and 1010 will die of these diseases [3]. The 5-yr overall survival rate in PUC patients is reported to be 42% [4, 5]. Disease management of PUC is based on tumor stage, patient sex and tumor location [2, 6, 7]. Surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy are standard treatment options for patients diagnosed with PUC [8–10]. Unfortunately, owing to its rare nature, there is a lack of large-scale investigations to support the treatment strategies. The aim of this study was to examine the impact of surgery on survival of patients diagnosed with PUC using a large population-based cancer database.

Methods

Selection of patient cohort

We searched Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) public-access database covering around 27.8% of the U.S. population from 2004 to 2016 and identified patients diagnosed with PUC based on the International Classification of Diseases-O-3 (ICD-O-3) codes C68.0. Only patients who met the following criteria were included: (1) urethra was the primary site; (2) survival time was ≥1 month; and (3) adequate tumor data were available. Data were extracted from the SEER database using SEER*Stat Software (version 8.3.6).

Data collection and variable definition

Parameters of interest included race, sex, age at diagnosis, the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging system, histology, tumor size, and grade. Therapy and follow-up information including type of surgical procedure, radiation, chemotherapy, survival months, and vital status were also collected. Surgical codes 30 (Simple/partial surgical removal of primary site), 40 (Total surgical removal of primary site; enucleation), 50 (Surgery stated to be “debulking”), and 60 (Radical surgery) for PUC were merged and collectively defined as “radical surgery”. Transurethral resection and other local tumor destruction or excision procedures (Surgical codes 10 and 20) were merged and collectively defined as “local therapy”. Surgical codes 00 (no surgery of primary site or autopsy only) was defined as “No surgery of primary site”. The overall survival (OS) months for PUC were defined as the time from diagnosis to any cause of death or last follow-up, with patients still alive censored at the last follow-up. For cancer-specific mortality (CSM), deaths not due to PUC were considered as competing risks.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s chi-square was applied to compare the distribution of categorical data. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were utilized to perform survival analysis. The Fine and Gray competing risk analysis was used to evaluate CSM [11, 12]. Multivariate Cox regression and competing risk regression analysis were utilized to identify independent risk factors to predict OS and cancer-specific survival (CSS) of PUC patients. All tests were two sided with a statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.2 (the R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of PUC patients

A total of 1544 PUC patients were identified. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient cohort are listed in Table 1. The majority of PUC patients were white (1164, 75.4%), male (971, 62.9%), with stage I (432, 28.2%) or IV (392, 25.6%) TNM stage, and III/ IV grade (833, 54.0%). Among 1544 PUC patients, 642 patients have precise tumor sizes, and the median size was 38.27 mm. Median age at diagnosis was 69.54 years. The pathological types comprised squamous cell carcinoma (437, 28.3%), transitional cell carcinoma (660, 42.7%), adenocarcinoma (252, 16.3%), and other pathological types (195, 12.6%). With regard to therapy, most patients underwent a surgical procedure (1114, 72.2%), and did not receive radiation (1141, 73.9%) or chemotherapy (1067, 69.1%).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of PUC patients

| Variable | Total (n = 1544) | Group A: No surgery of primary site (n = 403) | Group B: Local therapy (n = 532) | Group C: Radical surgery of primary site (n = 582) |

p value (A vs. B) |

p value (A vs. C) |

p value (B vs. C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 0.142 | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 69.54 (13.03) | 70.4 (13.52) | 73.02 (12.85) | 65.8 (11.89) | |||

| Race | 0.001* | 0.833 | 0.003* | ||||

| White | 1164 (75.4) | 288 (71.5) | 431 (81.0) | 422 (72.5) | |||

| Black | 290 (18.8) | 84 (20.8) | 81 (15.2) | 121 (20.8) | |||

| Other | 90 (5.8) | 31 (7.7) | 20 (3.8) | 39 (6.7) | |||

| Sex | <0.001* | 0.903 | <0.001* | ||||

| Male | 971 (62.9) | 233 (57.8) | 385 (72.4) | 333 (57.2) | |||

| Female | 573 (37.1) | 170 (42.2) | 147 (27.6) | 249 (42.8) | |||

| Grade | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||||

| I | 70 (5.1) | 25 (6.2) | 27 (5.1) | 26 (4.5) | |||

| II | 290 (18.8) | 70 (17.4) | 84 (15.8) | 130 (22.3) | |||

| III | 457 (29.6) | 123 (30.5) | 126 (23.7) | 203 (34.9) | |||

| IV | 376 (24.4) | 66 (16.4) | 168 (31.6) | 139 (23.9) | |||

| Unknown | 342 (22.2) | 119 (29.5) | 127 (23.9) | 84 (14.4) | |||

| Histology | <0.001* | 0.040* | <0.001* | ||||

| SCC | 437 (28.3) | 130 (32.2) | 95 (17.9) | 205 (35.2) | |||

| TCC | 660 (42.7) | 146 (36.2) | 305 (57.3) | 198 (34.0) | |||

| AC | 252 (16.3) | 59 (14.6) | 77 (14.5) | 111 (19.1) | |||

| Other | 195 (12.6) | 68 (16.9) | 55 (10.3) | 68 (11.7) | |||

| T stage | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||||

| T0/T1 | 521 (33.7) | 109 (27.0) | 274 (51.7) | 131 (22.5) | |||

| T2 | 315 (20.4) | 56 (13.9) | 110 (20.8) | 147 (25.3) | |||

| T3 | 318 (20.6) | 78 (19.4) | 54 (10.2) | 179 (30.8) | |||

| T4 | 180 (11.7) | 62 (15.4) | 35 (6.6) | 81 (13.9) | |||

| Tx | 207 (13.4) | 97 (24.1) | 57 (10.8) | 44 (7.6) | |||

| N stage | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||||

| N0 | 1040 (67.5) | 206 (51.2) | 416 (78.5) | 403 (69.2) | |||

| N1 | 149 (9.7) | 60 (14.9) | 23 (4.3) | 63 (10.8) | |||

| N2 | 154 (10.0) | 51 (12.7) | 33 (6.2) | 69 (11.9) | |||

| Nx | 198 (12.8) | 85 (21.1) | 58 (10.9) | 47 (8.1) | |||

| M stage | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.041* | ||||

| M0 | 1245 (80.8) | 258 (64.2) | 451 (85.1) | 517 (88.8) | |||

| M1 | 158 (10.3) | 96 (23.9) | 38 (7.2) | 22 (3.8) | |||

| Mx | 138 (9.0) | 48 (11.9) | 41 (7.7) | 43 (7.4) | |||

| AJCC stage groups | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||||

| I | 432 (28.2) | 68 (16.9) | 247 (47.0) | 111 (19.2) | |||

| II | 228 (14.9) | 38 (9.5) | 84 (16.0) | 104 (18.0) | |||

| III | 264 (17.2) | 48 (11.9) | 42 (8.0) | 170 (29.4) | |||

| IV | 392 (25.6) | 158 (39.3) | 84 (16.0) | 145 (25.1) | |||

| Unknown | 217 (14.2) | 90 (22.4) | 69 (13.1) | 48 (8.3) | |||

| Tumor size, mm (n = 642) | <0.001* | 0.041* | 0.007* | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 38.27 (24.31) | 44.30 (24.18) | 30.20 (19.82) | 38.88 (25.01) | |||

| Radiation | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.641 | ||||

| Yes | 403 (26.1) | 146 (36.2) | 113 (21.2) | 116 (19.9) | |||

| No/Unknown | 1141 (73.9) | 257 (63.8) | 419 (78.8) | 466 (80.1) | |||

| Chemotherapy | <0.001* | 0.006* | 0.011* | ||||

| Yes | 477 (30.9) | 161 (40.0) | 129 (24.2) | 182 (31.3) | |||

| No/Unknown | 1067 (69.1) | 242 (60.0) | 403 (75.8) | 400 (68.7) | |||

PUC Primary urethral carcinoma, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer

Survival analyses in the overall patient cohort stratified by surgical procedure

Among the 1544 PUC patients, 403 (26.1%) did not undergo any surgery to the primary tumor, 532 (34.5%) received local therapy (transurethral or transvaginal resection), and 582 (37.7%) underwent radical surgery (urethrectomy). Patient characteristics stratified by surgical procedure are also presented in Table 1. The 5-yr OS was significantly better in patients undergoing either local therapy (39.8%; 95% CI: 35.3–44.7) or radical surgery (44.7%; 95% CI: 40.1–49.7) compared to patients receiving no surgery of the primary site (21.5%; 95% CI: 17.4–26.7) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1 and Table 4). In addition, undergoing local therapy or radical surgery was each independently associated with decreased CSM, with predicted 5-yr cumulative incidence of 45.4 and 43.3%, respectively, compared to 64.7% for patients receiving no surgery of the primary site (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1 and Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves and risk tables of OS (a), cumulative incidence of CSM (b) in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure

Table 4.

Subset analyses of survival of PUC patients based on age at diagnosis, AJCC 8th M stage, AJCC 8th stage groups and tumor size and sex

| Overall cohort | n | Median Survival (month) | 3-yr OS, % | 5-yr OS, % | p value | CSM, % | ||

| 1-yr | 3-yr | 5-yr | ||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 403 | 16 (14–20) | 32.7 (28.2–38.0) | 21.5 (17.4–26.7) | <0.001* a | 35.2 | 55.4 | 64.7 |

| Local therapy | 532 | 39 (29–45) | 51.0 (46.7–55.7) | 39.8 (35.3–44.7) | 0.001* b | 20.4 | 38.9 | 45.4 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 582 | 49 (42–60) | 57.7 (53.4–62.3) | 44.7 (40.1–49.7) | <0.001* c | 12.0 | 33.5 | 43.3 |

| Age, yr | n | Median Survival (month) | 3-yr OS, % | 5-yr OS, % | p value | CSM, % | ||

| 1-yr | 3-yr | 5-yr | ||||||

| <70 | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 178 | 21 (16–36) | 40.9 (33.9–49.4) | 24.7 (18.3–33.4) | <0.001* | 27.6 | 53.6 | 68.9 |

| Local therapy | 184 | 105 (74-NA) | 69.3 (62.5–76.7) | 58.9 (51.4–67.4) | 0.465 | 11.8 | 26.4 | 32.8 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 354 | 84 (56–117) | 65.1 (59.9–70.8) | 53.8 (48.1–60.3) | <0.001* | 10.5 | 29.2 | 38.0 |

| ≥70 | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 225 | 12 (9–17) | 26.4 (20.9–33.3) | 19.2 (14.3–26.0) | <0.001* | 41.2 | 56.8 | 61.1 |

| Local therapy | 348 | 25 (21–30) | 41.6 (36.4–47.4) | 30.0 (25.0–35.9) | 0.059 | 24.8 | 45.3 | 51.9 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 228 | 32 (27–38) | 45.8 (39.1–53.7) | 30.1 (23.7–38.2) | <0.001* | 14.5 | 40.4 | 51.7 |

| AJCC 8th M stage | n | Median Survival (month) | 3-yr OS, % | 5-yr OS, % | p value | CSM, % | ||

| 1-yr | 3-yr | 5-yr | ||||||

| M0 | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 258 | 25 (20–31) | 42.2 (36.2–49.1) | 29.2 (23.5–36.2) | 0.001* | 23.8 | 46.2 | 57.4 |

| Local therapy | 451 | 44 (37–55) | 54.8 (50.2–59.9) | 42.7 (37.9–48.2) | 0.002* | 15.3 | 34.0 | 40.9 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 517 | 54 (47–63) | 61.0 (56.5–65.8) | 47.0 (42.2–52.4) | <0.001* | 9.0 | 30.0 | 40.3 |

| M1 | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 96 | 7 (5–9) | NA | NA | 0.539 | 66.3 | NA | NA |

| Local therapy | 38 | 7 (5–11) | NA | NA | 0.007* | 71.1 | NA | NA |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 22 | 10 (6–31) | NA | NA | 0.040* | 52.2 | NA | NA |

| AJCC stage groups | n | Median Survival (month) | 3-yr OS, % | 5-yr OS, % | p value | CSM, % | ||

| 1-yr | 3-yr | 5-yr | ||||||

| I/ II | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 106 | 30 (21–61) | 48.4 (39.5–59.3) | 39.6 (30.8–51.0) | 0.392 | 19.4 | 35.9 | 42.0 |

| Local therapy | 331 | 52 (43–65) | 57.9 (52.6–63.8) | 46.1 (40.5–52.5) | <0.001* | 13.3 | 29.5 | 35.6 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 215 | 102 (76-NA) | 74.8 (68.7–81.6) | 62.5 (55.2–70.6) | <0.001* | 2.0 | 14.7 | 24.7 |

| III /IV | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 206 | 14 (12–16) | 25.2 (19.5–36.7) | 12.9 (8.3–19.9) | 0.053 | 44.6 | 68.1 | 79.7 |

| Local therapy | 126 | 16 (11–23) | 31.8 (24.0–42.0) | 21.7 (17.4–32.0) | <0.001* | 38.6 | 62.1 | 69.7 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 315 | 35 (28–45) | 48.3 (42.5–54.8) | 34.3 (28.5–41.4) | <0.001* | 16.7 | 43.6 | 53.6 |

| Tumor size, mm | n | Median Survival (month) | 3-yr OS, % | 5-yr OS, % | p value | CSM, % | ||

| 1-yr | 3-yr | 5-yr | ||||||

| <30 | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 32 | 44 (28-NA) | 60.4 (44.2–82.4) | 34.5 (16.8–70.6) | 0.340 | 19.5 | 35.5 | 61.4 |

| Local therapy | 60 | 69 (35-NA) | 61.9 (49.6–77.2) | 52.7 (40.2–69.2) | 0.086 | 9.1 | 26.2 | 30.8 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 136 | NA | 71.3 (63.2–80.4) | 58.8 (49.4–70.1) | 0.032* | 3.9 | 19.3 | 30.1 |

| ≥30 | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 92 | 16 (12–25) | 29.7 (21.1–41.8) | 18.7 (11.4–30.5) | 0.366 | 39.3 | 62.7 | 72.1 |

| Local therapy | 62 | 19 (12–38) | 36.4 (25.4–52.3) | 21.9 (12.6–37.9) | 0.005* | 30.8 | 53.2 | 60.5 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 252 | 37 (30–48) | 50.0 (43.7–57.3) | 37.7 (31.2–45.4) | <0.001* | 16.8 | 42.5 | 52.2 |

| Sex | n | Median Survival (month) | 3-yr OS, % | 5-yr OS, % | p value | CSM, % | ||

| 1-yr | 3-yr | 5-yr | ||||||

| Male | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 233 | 16 (12–20) | 32.7 (26.8–39.8) | 23.2 (17.8–30.2) | <0.001* | 39.3 | 56.6 | 63.5 |

| Local therapy | 385 | 38 (28–46) | 51.1 (46.1–56.6) | 39.1 (34.0–45.0) | 0.025* | 21.4 | 38.8 | 45.0 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 333 | 46 (37–60) | 55.8 (50.1–62.1) | 42.5 (36.5–49.5) | <0.001* | 13.1 | 33.4 | 42.8 |

| Female | ||||||||

| No surgery of primary site | 170 | 16 (15–25) | 32.8 (26.1–41.2) | 19.0 (13.2–27.5) | <0.001* | 29.7 | 53.8 | 66.7 |

| Local therapy | 147 | 39 (25–76) | 50.7 (42.5–60.5) | 41.3 (33.1–51.6) | 0.045* | 17.6 | 39.4 | 46.8 |

| Radical surgery of primary site | 249 | 52 (44–84) | 60.1 (53.9–67.1) | 47.5 (40.9–55.1) | <0.001* | 10.6 | 33.6 | 43.7 |

PUC Primary urethral carcinoma, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer, OS Overall survival, CSM Cancer-specific mortality

a comparing survival of patients with no surgery of primary site to patients with local therapy

b comparing survival of patients with local therapy to patients with radical surgery

c comparing survival of patients with no surgery of primary site to patients with radical surgery

Multivariate cox regression analysis and multivariable competing risks regression analysis

Based on the univariate and multivariate Cox regression model; older age, advanced T stage, lymph node involvement, metastatic disease, and larger tumor size were identified as independent risk factors associated with poorer OS (Table 2). Using a multivariable competing risks regression model, the factors independently associated with increased CSM for PUC patients were identified, included; older age, metastatic disease, advanced AJCC stage groups, and larger tumor size (Table 3). Notably, surgery of the primary site was independently associated with better OS (local therapy, p = 0.037; radical surgery, p < 0.001) and decreased CSM (p = 0.003).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis for predicting OS of PUC

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | p value | HR | 95%CI | p value | |

| Age | ||||||

| <70 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| ≥ 70 | 1.906 | 1.667–2.179 | <0.001* | 1.948 | 1.693–2.242 | <0.001* |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Ref | |||||

| Female | 0.919 | 0.803–1.051 | 0.281 | |||

| Race | ||||||

| White | Ref | |||||

| Black | 1.102 | 0.937–1.297 | 0.241 | |||

| Other | 1.050 | 0.786–1.404 | 0.741 | |||

| Grade | ||||||

| I | Ref | Ref | ||||

| II | 1.192 | 0.847–1.678 | 0.313 | 1.207 | 0.893–1.632 | 0.220 |

| III | 1.407 | 1.014–1.953 | 0.041* | 1.156 | 0.862–1.550 | 0.334 |

| IV | 1.342 | 0.961–1.874 | 0.085 | 1.214 | 0.895–1.646 | 0.213 |

| Histology | ||||||

| SCC | Ref | |||||

| TCC | 1.122 | 0.957–1.314 | 0.155 | 0.899 | 0.749–1.079 | 0.251 |

| AC | 0.906 | 0.737–1.114 | 0.301 | 0.765 | 0.619–0.946 | 0.014* |

| Other | 1.289 | 1.037–1.601 | 0.022* | 0.898 | 0.717–1.126 | 0.352 |

| T stage | ||||||

| T0/T1 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| T2 | 1.105 | 0.913–1.337 | 0.307 | 1.125 | 0.773–1.636 | 0.539 |

| T3 | 1.577 | 1.313–1.894 | <0.001* | 1.444 | 1.059–1.969 | 0.020* |

| T4 | 2.144 | 1.738–2.646 | <0.001* | 1.788 | 1.273–2.512 | <0.001* |

| N stage | ||||||

| N0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| N1 | 1.530 | 1.239–1.891 | <0.001* | 1.057 | 0.837–1.333 | 0.643 |

| N2 | 1.810 | 1.464–2.238 | <0.001* | 1.413 | 1.073–1.862 | 0.014* |

| M stage of BC | ||||||

| M0 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| M1 | 4.646 | 3.845–5.615 | <0.001* | 3.080 | 2.377–3.990 | <0.001* |

| AJCC stage groups | ||||||

| I | Ref | Ref | ||||

| II | 1.075 | 0.859–1.345 | 0.528 | 1.015 | 0.661–1.558 | 0.947 |

| III | 1.271 | 1.030–1.570 | 0.026* | 1.037 | 0.722–1.490 | 0.843 |

| IV | 2.685 | 2.247–3.209 | <0.001* | 0.973 | 0.658–1.438 | 0.891 |

| Tumor size, mm | ||||||

| <30 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| ≥ 30 | 1.662 | 1.307–2.115 | <0.001* | 1.369 | 1.176–1.594 | <0.001* |

| Surgery | ||||||

| No surgery | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Local therapy | 0.599 | 0.511–0.701 | <0.001* | 0.832 | 0.700–0.989 | 0.037* |

| Radical therapy | 0.458 | 0.389–0.539 | <0.001* | 0.626 | 0.524–0.746 | <0.001* |

| Radiation | ||||||

| No/Unknown | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 1.003 | 0.866–1.162 | 0.966 | |||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No/Unknown | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 0.984 | 0.855–1.134 | 0.826 | |||

OS Overall survival, PUC Primary urethral carcinoma, HR Hazard ratio, CI Confidence interval, Ref Reference, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer

Grade: Grade I (Well differentiated); Grade II (Moderately differentiated); Grade III (Poorly differentiated); Grade IV (Undifferentiated)

Table 3.

Multivariable competing risks regression analysis for predicting CSS of PUC

| Multivariable competing risks regression analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| SHR | 95%CI | p value | |

| Age | |||

| <70 | Ref | ||

| ≥ 70 | 1.456 | 1.249–1.698 | <0.001* |

| Grade | |||

| I/ II | Ref | ||

| III /IV | 1.116 | 0.939–1.327 | 0.213 |

| Histology | |||

| SCC/TCC/AC | Ref | ||

| Other | 1.008 | 0.795–1.276 | 0.950 |

| T stage | |||

| T0/T1/T2 | Ref | ||

| T3/T4 | 1.076 | 0.811–1.427 | 0.613 |

| N stage | |||

| N0 | Ref | ||

| N1/N2 | 1.264 | 0.997–1.603 | 0.053 |

| M stage | |||

| M0 | Ref | ||

| M1 | 2.556 | 1.986–3.290 | <0.001* |

| AJCC stage groups | |||

| I/ II | Ref | ||

| III /IV | 1.469 | 1.059–2.039 | 0.021* |

| Tumor size, mm | |||

| <30 | Ref | ||

| ≥ 30 | 1.311 | 1.095–1.568 | 0.003* |

| Surgery | |||

| No surgery | Ref | ||

| Local/Radical therapy | 0.760 | 0.636–0.908 | 0.003* |

CSS Cancer-specific survival, PUC Primary urethral carcinoma, SHR Subdistribution hazard ratio

CI Confidence interval, Ref Reference, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer

Subgroup survival analyses based on the risk factors

Subgroup analyses were performed to further evaluate survival benefit of surgery for PUC patients among groups based on age (< 70 vs ≥ 70 years), tumor size (< 30 vs ≥ 30 mm) or sex. Patients who underwent surgery of the primary site showed significant survival advantage in both age subgroups (Supplementary Figure 1 and Table 4). The benefit of surgery was more marked in patients aged < 70 years, with median survival months of 105 and 84 for local therapy and radical surgery, respectively, compared to 21 for patients receiving no surgery of the primary site. Patients who underwent radical surgery exhibited higher OS and decreased CSM regardless of tumor size (Supplementary Figure 2 and Table 4). In contrast there were no significant differences in survival between patients who received local therapy or no surgery of the primary site in either tumor size subgroup. Subset analyses based on sex also revealed that surgery of the primary site brought significant survival benefit regardless of sex (Supplementary Figure 3 and Table 4). To determine whether higher cancer stage affected survival among surgery groups, subset analyses were also performed based on AJCC stage groups. Patients who underwent radical surgery exhibited higher OS and decreased CSM regardless of stage groups (Supplementary Figure 4 and Table 4). Local therapy did not result in significantly greater OS compared to no surgery of the primary site in the I/II stage (p = 0.392) or the III/IV stage group (p = 0.053), but did result in longer median survival (52 months) compared to no surgery (30 months) in the I/II stage group. Patients who underwent surgery of the primary site showed significant survival advantage in M0 disease, but did not exhibit any benefit in M1 disease (Supplementary Figure 5 and Table 4).

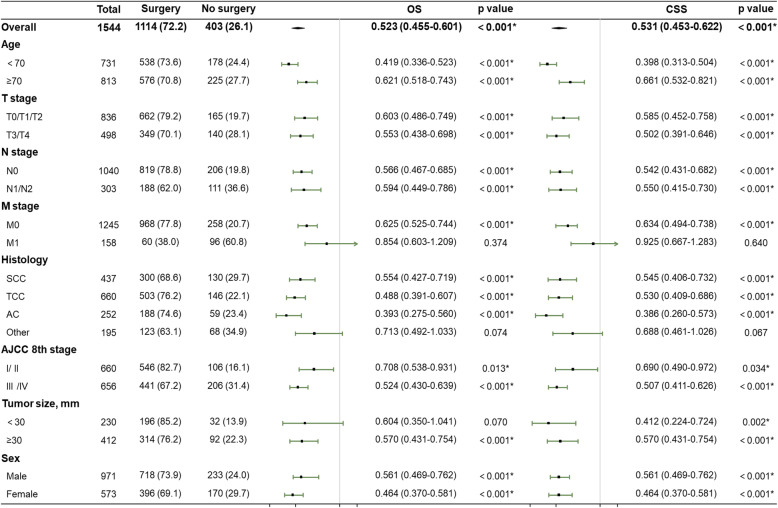

Cox’s and competing risks’ proportional hazard analyses

Finally, Cox’s and competing risks’ proportional hazard analyses were performed to assess the prognostic value of surgery in PUC patients (Fig. 2). Surgery of the primary site independently predicted statistically significantly higher OS and CSS in both age group (< 70 years, OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001; ≥ 70 years, OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001), both AJCC T stages (T0/T1/T2, OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001; T3/T4, OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001), both AJCC N stages (N0, OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001; N1/N2, OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001), both AJCC stage groups (I/ II, OS: p = 0.013, CSS: p < 0.001; III /IV, OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p = 0.034), both sexes (male, OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001; female, OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001), the larger tumor size group (OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001), and the M0 group (OS: p < 0.001, CSS: p < 0.001), but surgery of the primary site was not an independent risk factor in the M1 group (OS: p = 0.374, CSS: p = 0.640) or the other histology group (OS: p = 0.074, CSS: p = 0.067). Notably, surgery of the primary site was an independent risk factor in the smaller tumor size group based only on the competing risks’ proportional hazard analyses (p = 0.002).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots summarizing the HRs and 95% CIs of OS and CSS in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure

Discussion

PUC is an aggressive and rare carcinoma, comprising < 1% of all genitourinary malignancies [7, 13]. The disease management of PUC requires multimodal therapy to improve functional outcome and quality of life. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines, partial urethrectomy or urethra-sparing surgery is a valid treatment option for localized distal tumors (I/II stage), and Ta-Tis-T1 PUC can also be treated with a repeat transurethral or transvaginal resection. For patients with locally advanced disease (III/IV stage), multimodal treatment strategies are needed to optimize local control and prognosis. Chemotherapy followed by surgery or radiation therapy and concurrent chemoradiation with or without surgery have been shown to lead to an improvement in survival [2, 7, 14, 15]. However, given the rarity of PUC, there are few prospective multi-institutional studies to compare the effectiveness of various multimodal therapies, and the role of surgery in the management of PUC remains contentious.

To our knowledge, this is the first large population-based study to investigate the benefit of surgery for PUC patients. Our results demonstrated that PUC patients who underwent radical surgery or local therapy had a higher 5-yr OS and decreased CSM compared with patients who did not receive surgery of the primary site. Subgroup analysis based on TNM stage also demonstrated that survival of PUC patients who underwent surgery of the primary site was improved regardless of T stage, N stage, or AJCC prognostic group. In terms of M stage, PUC patients with metastatic disease were less likely to benefit from surgery. Notably, PUC patients with early TNM stage (I/II) who received radical surgery showed a more marked survival benefit, indicating that these patients were optimal candidates for urethrectomy.

We noted that factors independently associated with poor OS and increased CSM in PUC patients other than advanced TNM stage included age ≥ 70 years and tumor size ≥30 mm. Subset analyses revealed that patients < 70 years and tumor size ≥30 mm had a notably better survival benefit from surgery. Nevertheless, surgery of the primary site independently predicted significantly better prognosis in both age subgroups. Several studies have demonstrated anatomic differences between male and female PUC patients that contribute to variations in clinicopathological characteristics, including tumor location and histology [10, 16, 17]. In contrast we did not observe any difference in survival between males and females, and surgery of the primary site independently predicted statistically significantly higher OS and decreased CSM in both male and female PUC patients. SCC, TCC and AC together comprised approximately 90% of the histological types of PUC, and previous studies have demonstrated poorer survival in rare PUC pathological types [2, 18]. Subset analyses in our study demonstrated that PUC patients with the predominant histological types who underwent surgery of the primary site showed a significant survival advantage, while PUC patients with rare histological types were less likely to benefit from surgery. The results underscore the continued importance of improved guidelines for management of patients with rare PUC pathological types.

Despite several promising results, this registry-based study has unavoidable limitations. First, limitations of SEER-based studies included the absence of detail with regard to individual information about chemotherapy regimen and radiotherapy doses/fields. Thus, it was not possible to examine the effects of combined surgery and chemotherapy or radiotherapy on patient survival. Second, SEER also lacked information regarding the location of PUC, a significant prognostic factor that undoubtedly influences the treatment strategy. Moreover, this study is a retrospective analysis, and selection bias could not be completely avoided.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations of this study, our results suggest that surgery for the primary tumor conferred a survival advantage in non-metastatic PUC patients regardless of sex, age, T stage, and N stage. Furthermore, the surgical benefit was more marked in patients with early TNM stage (I/II) disease, patients < 70 years, and those with tumor size ≥30 mm.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and age. (a) Patients aged < 70 years, (b) patients aged ≥70 years.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure 2. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and tumor size. (a) Tumor size < 30 mm, (b) tumor size ≥30 mm.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Figure 3. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and sex. (a) Male, (b) female.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Figure 4. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and AJCC stage groups. (a) I/II stage, (b) III/IV stage.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Figure 5. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and M stage. (a) Stage M0, (b) stage M1.

Acknowledgements

We sincerest thank the editor and reviewers for careful review and valuable comments. The manuscript has certainly benefited from these insightful revision suggestions.

Abbreviations

- PUC

Primary urethral carcinoma

- OS

Overall survival

- CSM

Cancer-specific mortality

- CSS

Cancer-specific survival

- SEER

The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database

- ICD-O-3

The International Classification of Diseases-O-3

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- Ref

Reference

Authors’ contributions

JW performed all statistical analyses and was a major contributor in manuscript writing. Y-CW conducted the data collection and was involved in the manuscript writing. W-JL and BD were involved in the manuscript editing. D-WY and Y-PZ conceived and designed the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The funding body did not play any roles in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project 81772706).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database of the National Cancer Institute.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jie Wu and Yu-Chen Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Ding-Wei Ye, Email: dwyeli@yahoo.com.cn.

Yi-Ping Zhu, Email: fudanzhuyiping@163.com.

References

- 1.Amin MB, Young RH. Primary carcinomas of the urethra. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1997;14(2):147–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dayyani F, Hoffman K, Eifel P, Guo C, Vikram R, Pagliaro LC, Pettaway C. Management of advanced primary urethral carcinomas. BJU Int. 2014;114(1):25–31. doi: 10.1111/bju.12630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grigsby PW. Carcinoma of the urethra in women. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41(3):535–541. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(97)00773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalbagni G, Zhang ZF, Lacombe L, Herr HW. Male urethral carcinoma: analysis of treatment outcome. Urology. 1999;53(6):1126–1132. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00659-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sui W, RoyChoudhury A, Wenske S, Decastro GJ, McKiernan JM, Anderson CB. Outcomes and prognostic factors of primary urethral Cancer. Urology. 2017;100:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gakis G, Bruins HM, Cathomas R, Comperat EM, Cowan NC, van der Heijden AG, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on primary urethral Carcinoma-2020 update. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3(4):424-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Dimarco DS, Dimarco CS, Zincke H, Webb MJ, Bass SE, Slezak JM, et al. Surgical treatment for local control of female urethral carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2004;22(5):404–409. doi: 10.1016/S1078-1439(03)00174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen MS, Triaca V, Billmeyer B, Hanley RS, Girshovich L, Shuster T, Oberfield RA, Zinman L. Coordinated chemoradiation therapy with genital preservation for the treatment of primary invasive carcinoma of the male urethra. J Urol. 2008;179(2):536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei Y, Wu YP, Xu N, Li XD, Chen SH, Cai H, Zheng QS, Xue XY. Sex-related differences in clinicopathological features and survival of patients with primary urethral carcinoma: a population-based study. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:3381–3389. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S139252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scrucca L, Santucci A, Aversa F. Competing risk analysis using R: an easy guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40(4):381–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuk D, Varadhan R. Model selection in competing risks regression. Stat Med. 2013;32(18):3077–3088. doi: 10.1002/sim.5762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swartz MA, Porter MP, Lin DW, Weiss NS. Incidence of primary urethral carcinoma in the United States. Urology. 2006;68(6):1164–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dayyani F, Pettaway CA, Kamat AM, Munsell MF, Sircar K, Pagliaro LC. Retrospective analysis of survival outcomes and the role of cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with urethral carcinomas referred to medical oncologists. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(7):1171–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gakis G, Schubert T, Morgan TM, Daneshmand S, Keegan KA, Mischinger J, et al. The prognostic effect of salvage surgery and radiotherapy in patients with recurrent primary urethral carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2018;36(1):10 e7–10 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derksen JW, Visser O, de la Riviere GB, Meuleman EJ, Heldeweg EA, Lagerveld BW. Primary urethral carcinoma in females: an epidemiologic study on demographical factors, histological types, tumour stage and survival. World J Urol. 2013;31(1):147–153. doi: 10.1007/s00345-012-0882-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gakis G, Morgan TM, Efstathiou JA, Keegan KA, Mischinger J, Todenhoefer T, Schubert T, Zaid HB, Hrbacek J, Ali-el-Dein B, Clayman RH, Galland S, Olugbade K, Jr, Rink M, Fritsche HM, Burger M, Chang SS, Babjuk M, Thalmann GN, Stenzl A, Daneshmand S. Prognostic factors and outcomes in primary urethral cancer: results from the international collaboration on primary urethral carcinoma. World J Urol. 2016;34(1):97–103. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1583-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abudurexiti M, Wang J, Shao N, Wan FN, Zhu Y, Dai B, Ye DW. Prognosis of rare pathological primary urethral carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:6815–6822. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S184197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and age. (a) Patients aged < 70 years, (b) patients aged ≥70 years.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure 2. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and tumor size. (a) Tumor size < 30 mm, (b) tumor size ≥30 mm.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Figure 3. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and sex. (a) Male, (b) female.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Figure 4. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and AJCC stage groups. (a) I/II stage, (b) III/IV stage.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Figure 5. OS and CSM in PUC patients stratified by surgical procedure and M stage. (a) Stage M0, (b) stage M1.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database of the National Cancer Institute.