Abstract

Purpose

Despite data showing breathlessness to be more prevalent in older adults, we have little detail about the severity or multidimensional characteristics of breathlessness and other self-reported measures (such as quality of life and other cardiorespiratory-related symptoms) in this group at the population level. We also know little about the relationship between multidimensional breathlessness, other symptoms, comorbidities and future clinical outcomes such as quality of life, hospitalisation and mortality. This paper reports the design and descriptive findings from the first two waves of a longitudinal prospective cohort study in older adults.

Participants

Between 2010 and 2011, 1900 men in a region in southern Sweden aged 65 years were invited to attend for VAScular and Chronic Obstructive Lung disease (VASCOL) baseline (Wave 1) assessments which included physiological measurements, blood sampling and a self-report survey of lifestyle and previous medical conditions. In 2019, follow-up postal survey data (Wave 2) were collected with additional self-report measures for breathlessness, other symptoms and quality of life. At each wave, data are cross-linked with nationwide Swedish registry data of diseases, treatment, hospitalisation and cause of death.

Findings to date

1302/1900 (68%) of invited men participated in Wave 1, which include 56% of all 65-year-old men in the region. 5% reported asthma, 2% chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 56% hypertension, 10% diabetes and 19% had airflow limitation. The VASCOL cohort had comparable characteristics to those of similarly aged men in Sweden. By 2019, 109/1302 (8.4%) had died. 907/1193 (76%) of the remainder participated in Wave 2. Internal data completeness of 95% or more was achieved for most Wave 2 measures.

Future plans

A third wave will be conducted within 4 years, and the cohort will be followed through repeated follow-ups planned every fourth year, as well as national registry data of diagnosis, treatments and cause of death.

Keywords: geriatric medicine, epidemiology, cardiac epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

More than half (57%) of all 65-year-old men in Blekinge participated in the VAScular and Chronic Obstructive Lung disease (VASCOL) baseline, of which approximately 70% also participated in the follow-up.

The VASCOL baseline, Wave 1 (n=1302), collected a wide range of data: physiological measurements, blood samples, survey of lifestyle and self-reported conditions.

The VASCOL follow-up study, Wave 2 (n=907), included an extensive set of validated self-report instruments of symptoms of cardiorespiratory diseases.

Cross-linkage of data with national registries allowed prospective study of morbidity, hospitalisation and mortality in this cohort.

Introduction

Cardiorespiratory diseases, such as ischaemic heart disease, heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), are major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 2 They often coexist with, and are worsened by, other conditions leading to poorer outcomes. Multimorbidity increases over the age of 65 years, particularly those with cardiorespiratory diseases.3–5

Cardiorespiratory diseases are associated with major adverse health effects including anxiety and depression, poorer quality of sleep and impaired physical capacity.6 7 Symptoms of cardiorespiratory diseases include chest pain, nausea and fatigue, with the major ‘cardinal’ symptom being chronic breathlessness.8 Breathlessness is also highly prevalent across the older population,9 and the risk of developing breathlessness affecting daily life increases markedly with age.10 People who are breathless often avoid physical activities,11 many becoming socially isolated.8 12 In COPD, breathlessness is a stronger predictor of mortality than the level of airflow limitation.13 Breathlessness is also associated with impaired quality of life (QoL), worse physical capacity and higher overall mortality in people with different underlying conditions.7 8 14

Few population-level studies have focused on breathlessness and its relationship with other self-reported outcomes. The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD),15 the PLATINO16 and the European Community Respiratory Heath Survey (ECRHS)17 studies assessed breathlessness mainly using the unidimensional modified Medical Research Council Scale, which thus only assesses the level of exertion required to induce breathlessness, and not the severity of the symptom per se.12 Breathlessness is a multidimensional symptom affecting all domains of a person’s life18 and the intensity of both physical and affective dimensions needs to be included in measurements.7 18 For multidimensional assessment of breathlessness, the instruments Dyspnoea-12 (D12)19 and Multidimensional Dyspnoea Profile20 (MDP) can be used. Recently, the minimal clinically important difference was determined for both D12 and MDP in cardiorespiratory disease.21

Some breathlessness data from older adults at the general population level regarding prevalence and clinical outcomes are published, but details including characteristics, and severity are relatively few. We also know little about other common symptoms and comorbidities affect clinical outcomes such as QoL, health service utilisation and survival in older adults. To date, no study has assessed the relationship between multidimensional breathlessness and clinical outcomes in older adults in the general population.

The VAScular and Chronic Obstructive Lung disease (VASCOL) study is an epidemiological, longitudinal, cohort study to describe the relationship between vascular diseases and COPD. Since its beginning in 2010, the scope has broaden to also focus on QoL, self-reported measures of breathlessness and other symptoms of cardiovascular diseases.

In this paper, we present the VASCOL study design, including future longitudinal data collection, describe the characteristics of participants from the first two waves, (Wave 1—baseline; Wave 2—first follow-up).

Study objectives

The overall objective of the VASCOL study is to evaluate the relationship between lifestyle variables, morbidity due to cardiorespiratory disease, multidimensional breathlessness, other symptoms of cardiovascular diseases and QoL in a population sample of men aged 65 years on cohort entry. We aim to evaluate:

How baseline factors (diseases, lung function, lifestyle, demographics) predict the outcomes of breathlessness, QoL, diagnosed diseases, hospitalisation and mortality.

The prevalence, characteristics and severity of multidimensional breathlessness and other symptoms such as anxiety, depression, pain, nausea and fatigue.

The relationship between self-reported QoL and symptom burden and functional limitations.

Contributing causes of breathlessness and other symptoms such as anxiety, depression, pain, nausea and fatigue.

How the presence and type of symptoms predicts future diseases.

Cohort description

The VASCOL study is an ongoing longitudinal epidemiological cohort study in Blekinge, Sweden. Blekinge is a county located in southern Sweden and has a total population of around 160 000, of which approximately 2300 were 65-year-old men in 2010–2011. Blekinge geographically covers both urban and rural areas with good public transportations, see figure 1.

Figure 1.

Location of Blekinge in Sweden, Blekinge’s municipalities and main cities.

In 2010–2011, 1900 men aged 65 years in Blekinge were invited to a screening campaign of abdominal aortic aneurysm at a health centre in the city of Karlshamn.

The men were informed about the VASCOL study and invited to give their informed written consent to participate in the Wave 1 examinations. A self-report survey (demography, lifestyle and previous diseases) was included with the invitation pack. Blekinge’s biggest municipality, Karlskrona, was not included in the screening campaign until 2011, resulting in approximately 80% (1900/2300) of all 65-year-old men living in Blekinge 2010–2011 were invited to participate in the VASCOL study. The inclusion criteria were: men, 65 years old, living in Blekinge (excluding Karlskrona in 2010), participating in the screening examinations and willing to give a written consent to participate in the Wave 1 examinations. There were no exclusion criteria based on any conditions. In 2019, a follow-up postal survey was sent out to the participants still alive and with a known address (Wave 2).

Wave 1: baseline data collection

At baseline, a clinical visit was performed, and data from the self-report survey collected. Nurses checked for survey data completeness, and those who omitted to bring their survey were also able to complete this during the visit. Physiological measurements and blood sampling were collected according to standard protocols by registered nurses. The blood samples were stored in a biobank for future analysis. Out of the 1900 men attending the screening, 1302 (68.5%) participated in the VASCOL baseline study. Normative values for Swedish men in the same age group were also collected from The Public Health Agency of Sweden, National Board of Health and Welfare and Statistics Sweden.

Wave 2: follow-up survey

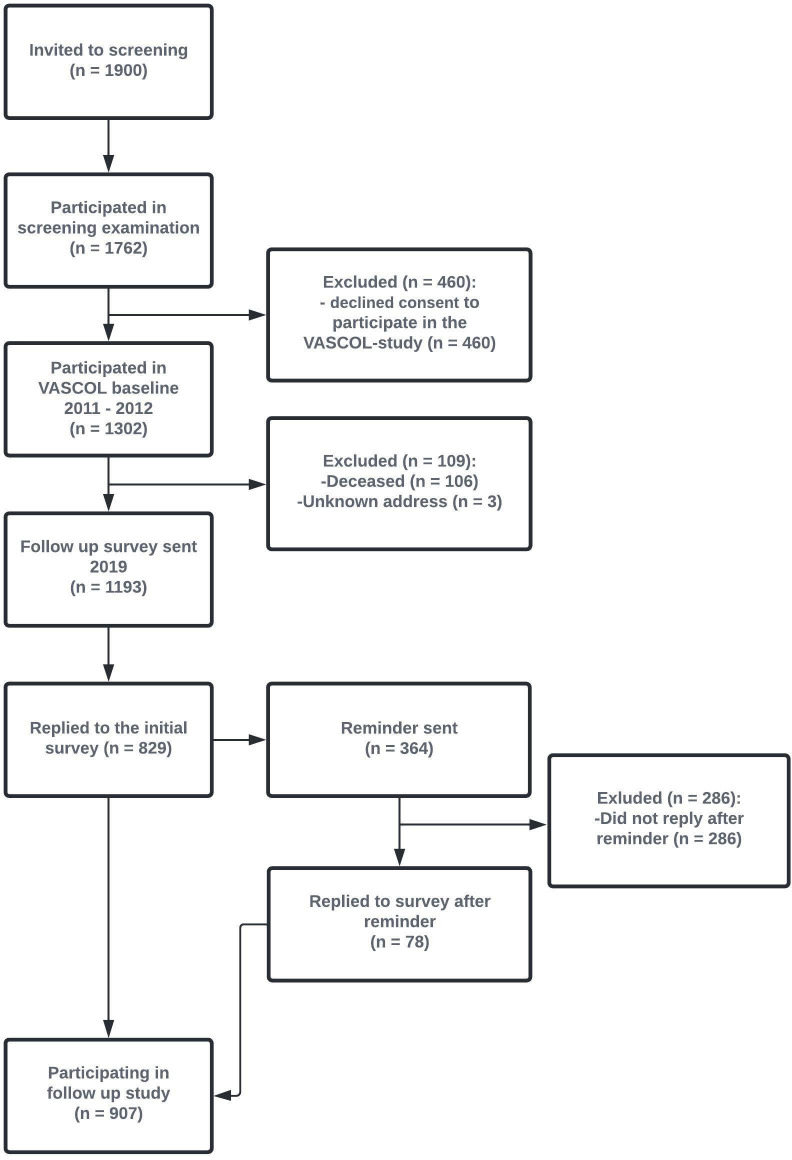

In 2019, the Blekinge county demographic registers were used to identify all participants who were alive with a known address (n=1193). A new survey was sent out to all these participants. At Wave 2, 829 of the men replied to the initial survey within 2 weeks, and additional 78 men replied after a reminder, leading to 907/1193 (76%) of men participated in Wave 2. See figure 2 for detailed information about data collection procedure. The postal survey consisted of questions and validated instruments regarding breathing, other cardiorespiratory-related symptoms, QoL, lifestyle, new medical conditions and any treatments for breathlessness. Most questions and instruments pertained to the experiences during the last 2 weeks.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the recruitment for the VASCOL study. VASCOL, VAScular and Chronic Obstructive Lung disease.

Planned data collection

Repeated waves will be conducted at four yearly intervals, to enable examination of the change in participants’ breathlessness, other symptoms and QoL. Wave 3 data collection will be conducted within 4 years, and the procedure and survey instruments will be similar to the first two waves. To broaden the VASCOL study and reach a bigger sample size, future data collections should also invite women to participate. Collected data will be cross-linked with nationwide Swedish registry data: Cause of Death Registry, Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry and National Patient Registry (see table 1). The Swedish registry databases have high coverage and completeness, but are limited in that they are not including any (or very limited) physiological variables and no symptoms or other patient reported outcomes. The VASCOL study and the registry databases will therefore complete each other.

Table 1.

Planned cross-linkage with national registries

| Data | Source | Timeframe of the data |

| Inpatient care including diagnoses, date for diagnoses, treatment, date for treatment and treatment time | Swedish National Patient Registry for Inpatient Care | 1987 to today |

| Outpatient care, diagnosis, date for diagnosis, treatment, date for treatment and treatment time | Swedish National Patient Registry for Outpatient Care | 2001 to today |

| Place, date and cause(s) of death | Causes of Death Registry | Baseline to today |

| Dispensed prescribed medications | Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry | July 2005 to today |

Patient and public involvement

The follow-up survey was piloted on 10 people of similar age to the VASCOL study participants before the final survey was revised and administered. The pilot participants had the opportunity to add areas of research that they thought were relevant. Pilot participants also gave feedback on the layout and length of the survey as well as how the questions were asked. Minor linguistically and layout changes were done to the survey questions to fit the specific study participants.

Findings to date

Baseline characteristics of the VASCOL study are shown in table 2. The majority of the participants had hypertension (56%), and approximately one fifth had airflow limitation (forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) <0.7). Only a small proportion had self-reported asthma (5%) or COPD (2%). One tenth (10%) reported diabetes. Also, approximately one tenth of the participants (13%) were everyday smokers, and the majority (54%) were former smokers. Around half of the participants were overweight (52%) and around one third (28%) obese. Participants in the VASCOL cohort had proportions similar to Swedish reference of normative values for similarly aged men concerning everyday smokers, height, FEV1/FVC and civil status. BMI values, educational level and proportion of former smokers were higher than the reference values.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | All participants, overall (n=1302) |

Non-missing observations, overall (%) | Participated in follow-up (n=907) |

Did not participate in follow (n=395) |

Reference for Swedish 65-year-old men |

| Self-reported data | |||||

| Married | 863 (71%) | 1210 (93) | 621 (73%) | 242 (66%) | 61% |

| Smoking status | 1302 (100) | ||||

| Current smoker | 168 (13%) | 91 (10%) | 77 (19%) | 13% | |

| Former smoker | 707 (54%) | 514 (57%) | 193 (49%) | 36% | |

| Never smoker | 427 (33%) | 302 (33%) | 125 (32%) | 51% | |

| Pack-years of smoking | 15.1±19.2 | 1276 (98) | 13.7±17.4 | 18.4±22.6 | |

| University/college or professional school education | 520 (42%) | 1218 (93) | 381 (44%) | 139 (38%) | 25% |

| Hypertension | 725 (56%) | 1294 (99) | 507 (56%) | 218 (55%) | |

| Diabetes | 132 (10%) | 1295 (99) | 79 (9%) | 53 (13%) | |

| Asthma | 71 (5%) | 1285 (99) | 47 (5%) | 24 (6%) | 9%* |

| COPD | 29 (2%) | 1205 (92) | 13 (1%) | 16 (4%) | |

| Measured data by staff | |||||

| Height | 179±6.3 | 1285 (99) | 179±6.1 | 179±7 | 178 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.2±4.1 | 1275 (98) | 28.1±4.0 | 28.5±4.4 | 26* |

| Underweight, BMI <18.5 | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.6%* | |

| Normal weight, BMI 18.5–24.9 | 260 (20%) | 184 (21%) | 76 (20%) | 39%* | |

| Overweight, BMI 25–29.9 | 661 (52%) | 470 (53%) | 191 (50%) | 46%* | |

| Obesity, BMI >=30 | 352 (28%) | 234 (26%) | 118 (31%) | 14%* | |

| FEV1, % of predicted | 87.2±15.1 | 1278 (98) | 88.5±14.7 | 84.3±15.8 | |

| FVC, % of predicted | 85.4±13.1 | 1278 (98) | 86.3±13.0 | 83.4±13.1 | |

| FEV1/FVC < 0.7 | 242 (19%) | 1295 (99) | 157 (17%) | 85 (22%) | 18.2%† |

Data are presented as mean±SD or frequency (rounded percentage). Normative values were collected from the publicly available databases of The Public Health Agency of Sweden (www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se), and Statistics Sweden (www.scb.se). The following variables are collected but not included in the table. Self-reported: exercise habits, alcohol consumption, tiredness, blood pressure medication, myocardial infarction, stroke, tia, angina pectoris, apnoea, snoring, osteoporosis, fractures, back pain, femur, radius, glaucoma, cataract, intermittent claudication. Measured by staff: blood pressure, pulse, weight, waist, swab measure, number of teeth, aortic diameter. Blood sample: Hb, HbA1C (% and later mmol), P-cystatin C, p-glucose, PT-GFR (CC estimate), S-CA, S-Na, S-K, S-creatinine, S-total cholesterol, ApoA1, ApoB.

*Reference based on available self-reported data for men 65 years or older.

†Reference based on available data for men 40 years or older.22

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Overall, the internal data completeness in the follow-up was high, with most instruments having 95% completion or more (table 3). Men participating in Wave 2 had an overall better health, healthier lifestyle and higher education at baseline than those who did not participate in the follow-up (table 2). Wave 2 participants had a lower proportion of current smokers and a lower average number of pack-years. Those providing data for Wave 2 had fewer comorbidities than those who did not, but who were still alive, other than hypertension which was equally prevalent.

Table 3.

Follow-up survey data collected

| Description | Non-missing observations, % | |

| Measurements and analyses | ||

| Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) breathlessness scale23 | Functional impact of breathlessness (yes or no at each item) | 97 |

| mMRC-scale | Intensity of functional impact of breathlessness (0–10 at each item) | 97 |

| Dyspnoea-12 (D-12)24 | Multidimensional breathlessness | 95 |

| Multidimensional Dyspnoea Profile (MDP) total20 | Multidimensional breathlessness | 77 |

| MDP A1 unpleasantness | Breathing unpleasantness | 91 |

| MDP perception score | MDP A1 and five perception descriptors | 79 |

| MDP emotional response score | Five emotional descriptors | 89 |

| Short form 12 item (version 2) Health survey14 | Quality of life | 98 |

| Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, Revised (ESAS-r)25 | Associated symptoms | 98 |

| FACIT-Fatigue26 | Pathological tiredness | 98 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)27 | Anxiety and depression | 94 |

| WHO Performance Status 0–428 | Performance status | 97 |

| Custom items | ||

| Global impression of change (GIC)29 in breathlessness since baseline | Seven categories from very much better to very much worse | 99 |

| Global impression of change (GIC)29 in health since baseline | Seven categories from very much better to very much worse | 98 |

| Activities given up because of breathlessness | What activities have the participant giving up doe to breathlessness | 91 |

| Breathlessness unpleasantness | Likert scale, four categories from mild to severe | 93 |

| Breathlessness duration | How many years the participant have experience breathlessness | 89 |

| Proportion of awake time experiencing breathlessness | Five categories from none to whole time awake | 91 |

| Experiences temporary worsening breathlessness (how often, how long, when, causative factors). | 4–6 categories at each question | 94 |

| Self-reported treatments of breathlessness | Eight different possible treatments for breathlessness, and free text | 89 |

| Smoking status | Four categories (everyday, sometimes, former and never smoker) | 98 |

| Smoking frequency | Years of smoking, and number of cigarettes per day | 92 |

| Alcohol use | Amount of wine, beer and strong spirit a week | 84 |

| Quality and duration of sleep | Quality: 5 categories. Duration: 7 categories | 99 |

| Physical activity frequency | Four categories, from daily to never | 99 |

| Physical activity intensity | Four categories, from sedentary to intensity | 97 |

| Self-reported conditions | Nineteen different possible diseases and conditions | 95 |

| Self-reported height and weight now | cm and kg | 99 |

| Recall of height and weight at the age of 20 | cm and kg | 92 |

Statistical methodology

A detailed statistical analysis plan will be prepared before each analysis. Relevant characteristics for each studies objective will be tabulated and compared using standard descriptive methods. Associations will be evaluated using regression models including logistic regression for categorical outcomes, and linear regression for continuous outcomes. Kaplan-Meier, Cox proportional hazards regression and Fine-Grey regression (accounting for competing events) will be used for time-to-event analyses.

Sample size/power

The participants in the first follow-up of the VASCOL study (Wave 2) cover 45% of the population of men in the age group (n=2013) in Blekinge in 2019. Statistical power will be specified for each analysis.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the VASCOL study include that it covers a large proportion of the eligible men in Blekinge. Over half (1302/2300) of all 65-year-old men in Blekinge county participated in the VASCOL baseline. The quality of the data was good, with a high-data completeness. The cohort is similar to men aged 65 in Sweden as a whole, which gives confidence regarding generalisability for men. However, a limitation is that we cannot generalise for women or younger men and future data collections should therefore include these groups. A limitation is the fact that nearly one-quarters (30%) of the participants did not participate in the follow-up (Wave 2). However, all participants in VASCOL baseline can be followed through the national registries, which can give some insight about the participants who did not participate in the follow-up (Wave 2). Participants in the follow-up study (Wave 2) was overall healthier at baseline than those not participating which might be explained by lower motivation to participate in studies among those with poorer health or that less healthy participants have deceased between the baseline and follow-up study.

The VASCOL study is to our knowledge, the most detailed prospective population-based study of breathlessness and other symptoms of cardiorespiratory diseases linked to registries with key information regarding health service utilisation and survival. Also, there are, to our knowledge, few population studies of older men’s symptoms and QoL. The VASCOL data are rich and consist of physiological measurements, blood samples and extensive survey data which make it possible to study many aspects of different symptoms and conditions. Sweden has a rich set of health-related registry data that can be cross-linked with the VASCOL data, and the variables collected in the VASCOL study can be studied as risk factors for outcomes such as morbidity, hospitalisation and mortality. The set of variables of the VASCOL data also enables studies of different conditions, long-term effect on breathlessness and other symptoms. The symptom data mostly consist of validated instruments, which enables comparison with other studies.

A limitation of the collected data is that former workplaces were not recorded, and pollution from dusty workplaces could possibly be a confounder of breathlessness. Also, cough was not measured, which is a common symptom of COPD. We therefore plan to include questions about former workplaces and cough in future follow-ups. Breathlessness was not assessed at baseline so the Global impression of change of breathlessness was used in Wave 2. This introduces the risk of recall bias in studies of changed breathlessness between Waves 1 and 2, and an inherently unknown baseline measurement error, but nevertheless is accepted as a valid approach. Further, for future VASCOL waves, the repeated self-report breathlessness measures will enable longitudinal examination from Wave 2.

Cardiorespiratory diseases, as well as breathlessness are common in the older population,3 9 and we believe that the VASCOL study can add valuable knowledge of the symptoms in the population. We will add knowledge regarding which symptoms predict worse clinical outcomes to identify people with a higher risk of mortality and morbidity, and as a potential therapeutic target.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank associate professor Kerstin Ström who initiated and led the VASCOL baseline study, the nurses and staff that performed the assessments and all participants who contributed to this research.

Footnotes

Collaborators: We welcome researchers from different disciplines and fields for collaboration over the collected data from the VASCOL study, including suggested additional data collection. Interested researchers should submit a study proposal to the corresponding author. All study proposals will be reviewed by the VASCOL research group. All additional objectives not included in this paper must also be approved by the Sweden’s national ethical review board.

Contributors: MPE was responsible for the conceptualisation of the wave 2 study and will take the role as principal investigator. Kerstin Ström was responsible for the wave 1 data collection. MPE and MO conducted wave 2 data collection and will collect the data for wave 3 as well as cross-linking data with national registries. MO, MPE wrote the first draft of this cohort profile. GE, DCC, MJ and JS contributed with their research experience and medical knowledge in interpretation of the findings, review and revision of the manuscript draft. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: The VASCOL baseline study was funded by the Research Council of Blekinge. MO and MPE was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Swedish Research Council (reference number: 2019-02081).

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The VASCOL research group will consider requests for using de-identified data from the VASCOL study by external collaborators. Also, all requests must be approved by the Sweden’s national ethical review board.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The baseline study was approved by the regional ethical review board at Lund University (reference number: 2008/676). The first follow-up study and the registry data cross-linkage was approved by the national ethical review board (reference number: 2019-00134).

References

- 1.Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1–25. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yazdanyar A, Newman AB. The burden of cardiovascular disease in the elderly: morbidity, mortality, and costs. Clin Geriatr Med 2009;25:563–77. 10.1016/j.cger.2009.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380:37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter P, Lagan J, Fortune C, et al. Association of cardiovascular disease with respiratory disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2166–77. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandberg J, Ekström M, Börjesson M, et al. Underlying contributing conditions to breathlessness among middle-aged individuals in the general population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open Respir Res 2020;7:e000643. 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zambroski CH, Moser DK, Bhat G, et al. Impact of symptom prevalence and symptom burden on quality of life in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005;4:198–206. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laviolette L, Laveneziana P, Faculty E, ERS Research Seminar Faculty . Dyspnoea: a multidimensional and multidisciplinary approach. Eur Respir J 2014;43:1750–62. 10.1183/09031936.00092613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson MJ, Yorke J, Hansen-Flaschen J, et al. Towards an expert consensus to delineate a clinical syndrome of chronic breathlessness. Eur Respir J 2017;49. 10.1183/13993003.02277-2016. [Epub ahead of print: 25 05 2017]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith AK, Currow DC, Abernethy AP, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of breathlessness in older adults: a national population study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:2035–41. 10.1111/jgs.14313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grønseth R, Vollmer WM, Hardie JA, et al. Predictors of dyspnoea prevalence: results from the BOLD study. Eur Respir J 2014;43:1610–20. 10.1183/09031936.00036813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kochovska S, Chang S, Morgan DD, et al. Activities Forgone because of chronic breathlessness: a cross-sectional population prevalence study. Palliat Med Rep 2020;1:166–70. 10.1089/pmr.2020.0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, et al. An official American thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:435–52. 10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishimura K, Izumi T, Tsukino M, et al. Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest 2002;121:1434–40. 10.1378/chest.121.5.1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Currow DC, Dal Grande E, Ferreira D, et al. Chronic breathlessness associated with poorer physical and mental health-related quality of life (SF-12) across all adult age groups. Thorax 2017;72:1151–3. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007;370:741–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menezes AMB, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JRB, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence study. Lancet 2005;366:1875–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67632-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinrich J, Richter K, Frye C, et al. [European Community Respiratory Health Survey in Adults (ECRHS)]. Pneumologie 2002;56:297–303. 10.1055/s-2002-30699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchinson A, Barclay-Klingle N, Galvin K, et al. Living with breathlessness: a systematic literature review and qualitative synthesis. Eur Respir J 2018;51. 10.1183/13993003.01477-2017. [Epub ahead of print: 21 02 2018]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sundh J, Ekström M. Dyspnoea-12: a translation and linguistic validation study in a Swedish setting. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014490. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekström M, Bornefalk H, Sköld M, et al. Validation of the Swedish multidimensional dyspnea profile (MDP) in outpatients with cardiorespiratory disease. BMJ Open Respir Res 2019;6:e000381. 10.1136/bmjresp-2018-000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekström MP, Bornefalk H, Sköld CM, et al. Minimal clinically important differences and feasibility of Dyspnea-12 and the multidimensional dyspnea profile in cardiorespiratory disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:968–75. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danielsson P, Ólafsdóttir IS, Benediktsdóttir B, et al. The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Uppsala, Sweden--the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study: cross-sectional population-based study. Clin Respir J 2012;6:120–7. 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2011.00257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ekström M, Chang S, Johnson MJ, et al. Low agreement between mMRC rated by patients and clinicians: implications for practice. Eur Respir J 2019;54. 10.1183/13993003.01517-2019. [Epub ahead of print: 19 12 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yorke J, Moosavi SH, Shuldham C, et al. Quantification of dyspnoea using descriptors: development and initial testing of the Dyspnoea-12. Thorax 2010;65:21–6. 10.1136/thx.2009.118521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hannon B, Dyck M, Pope A, et al. Modified Edmonton symptom assessment system including constipation and sleep: validation in outpatients with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:945–52. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-shair K, Muellerova H, Yorke J, et al. Examining fatigue in COPD: development, validity and reliability of a modified version of FACIT-F scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:100. 10.1186/1477-7525-10-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nowak C, Sievi NA, Clarenbach CF, et al. Accuracy of the hospital anxiety and depression scale for identifying depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Pulm Med 2014;2014:1–7. 10.1155/2014/973858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young J, Badgery-Parker T, Dobbins T, et al. Comparison of ECOG/WHO performance status and ASA score as a measure of functional status. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:258–64. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurst H, Bolton J. Assessing the clinical significance of change scores recorded on subjective outcome measures. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004;27:26–35. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2003.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The VASCOL research group will consider requests for using de-identified data from the VASCOL study by external collaborators. Also, all requests must be approved by the Sweden’s national ethical review board.