Abstract

Background & purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted mental health in the general population. In this trial, our objective was to assess whether a 6-week expressive writing intervention improves resilience in a sample from the general population in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials & methods

This 6-week trial was conducted online. Eligible participants (n=63) were a sample of adults who self-identified as having been significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Primary outcome

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC).

Secondary outcomes

Perceived Stress Scale – 10-Item (PSS-10); Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale – Revised (CESD-R); Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI).

Results

Resilience measures (CD-RISC) increased from baseline (66.6 ± 14.9) to immediately post-intervention (73.0 ± 12.4; p=0.014; Cohen’s d =0.31), and at a 1- month follow-up (72.9 ± 13.6; p=0.024; Cohen’s d =0.28). Across the same timepoints, perceived stress scores (PSS-10) decreased from baseline (21.8 ± 6.6) to immediately post-intervention (18.3 ± 7.0; p=0.008; Cohen’s d =0.41), and at the 1- month follow-up to (16.8 ± 6.7; p=0.0002; Cohen’s d =0.56). Depression symptoms (CESD-R) decreased from baseline (23.3 ± 15.3) at 6 weeks (17.8 ± 15.4; p=0.058; Cohen’s d =0.22), and 10 weeks (15.5 ± 12.7; p=0.004; Cohen’s d =0.38). Posttraumatic growth (PTGI) increased from baseline (41.7 ± 23.4) at 6 weeks (55.8 ± 26.4; p=0.004; Cohen’s d =0.44), and at the 1-month follow-up (55.9 ± 29.3; p=0.008; Cohen’s d =0.49).

Conclusion

An online expressive writing intervention was effective at improving resilience in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

NCT#

Keywords: Expressive writing, Narrative medicine, COVID-19, Resilience, Integrative Medicine

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by the novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and has led to over 2.67 million deaths worldwide as of March 2021 [1,2]. COVID-19 is highly transmissible, and in order to mitigate community spread of COVID-19, countries around the world have implemented social distancing measures, mask wearing, and mass quarantine efforts to mitigate community spread [3,4]. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted people in many different ways, causing significant distress in the mental health of the general population [5]. Fear of contracting the virus, food insecurity, social isolation, job loss/transition, and loss of childcare are just a few of the circumstances surrounding COVID-19 that have negatively impacted mental health [6,7]. A global survey conducted between March 29, 2020 and April 14, 2020 observed that general psychological disturbance, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression worsened during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, with a 16 % increase in suicidal ideation [8]. As a growing number of individuals suffer from the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, there is a critical need to offer mental health interventions, support, and tools that are scalable and can be delivered in an effective manner.

Expressive writing is a well-established therapeutic intervention to improve emotional, psychological, and physiological health in those that have experienced one or more traumatic events [[9], [10], [11]]. We have previously shown that the Transform Your Health: Write to Heal program, an expansion of the Pennebaker Paradigm framework for expressive writing, improves perceived stress, depression symptoms, rumination, and resilience [12]. Resilience, an individual's capacity to recover and thrive in the face of adverse events, is inversely associated with negative mental health states and has been a primary focus to counteract stressors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic [13,14]. The present study builds upon our prior work by evaluating the feasibility of delivering a 6-week expressive writing intervention online to a larger number of participants. Few expressive writing studies have been successfully administered online [[15], [16], [17], [18]]. However, COVID-19 precipitated a shift towards internet-delivered health care services, and we sought to leverage this shift in the emphasis on technology to deliver an expressive writing intervention to the general population. We also aimed to determine whether adapting the Transform Your Health: Write to Heal program to explore emotions and perspectives in the COVID-19 pandemic improves resilience, perceived stress, depression symptoms, and post-traumatic growth in a sample from the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials & methods

-

a.

Study design

This interventional study applied a single-group non-randomized and non-blinded pre- and post-test clinical trial design. This study was fully approved by the Duke Health System Institutional Review Board in Durham, NC. All participants provided informed consent online at the start of enrollment. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04589104.

-

b.

Participants

Participants were recruited through an email sent out to the Duke Integrative Medicine email list in May 2020. This email list targeted a general population interested in integrative approaches to health and wellness. Eligible participants were ≥18 years of age, able to read and type/write in English, cognitively able to provide informed consent, and self-identified as having been directly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. “Affected by the COVID-19 pandemic” was defined broadly, and included a wide range of experiences: some participants had lost loved ones to COVID-19, some continued to work as frontline workers, some had lost employment or access to health care, and others’ impact was primarily the experience of social isolation. Prior diagnosis of mental health concerns was not part of our exclusion criteria, but all participants were provided a list of mental health resources at the beginning of the study and encouraged to let the study coordinator know if additional support was needed at any time during the study. At baseline, no participant had been diagnosed with COVID-19, and by the completion of the study, two participants had been officially diagnosed with COVID-19. Although the 6-week program was offered at no cost to participants, no additional compensation was provided. Participants were represented by 13 states and 3 countries. Baseline demographics are provided in Table 1 .

-

c.

Procedure

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of participants (n = 63).

| Variable | Number or Mean | % or SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 57.3 | 15.18 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 6 | 9.52 % |

| Female | 56 | 88.89 % |

| Nonbinary | 1 | 1.59 % |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 55 | 87.30 % |

| African American or Black | 4 | 6.35 % |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4 | 6.35 % |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 1 | 1.59 % |

| Not Hispanic | 53 | 84.13 |

| Other/Not reported | 9 | 14.29 % |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 35 | 55.56 |

| Separated | 2 | 3.17 % |

| Divorced | 9 | 14.29 % |

| Partnered | 4 | 6.35 % |

| Single | 9 | 14.29 % |

| Other/Prefer not to say | 4 | 6.35 % |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full time | 19 | 30.16 % |

| Part time | 11 | 17.46 % |

| Retired | 18 | 25.57 % |

| Unemployed | 11 | 17.46 % |

| Other | 4 | 6.35 % |

| Formal Education | ||

| Some college | 4 | 6.35 % |

| College degree | 14 | 22.22 |

| Partial master's degree | 6 | 9.52 % |

| Full master's degree | 26 | 41.27 % |

| Partial doctorate degree | 3 | 4.76 % |

| Doctorate degree | 10 | 15.87 % |

| Household Income | ||

| $0-$24,999 | 3 | 4.76 % |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 9 | 14.29 % |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 11 | 17.46 % |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 8 | 12.70 % |

| $100,000-$150,000 | 15 | 23.81 % |

| $150,000 or more | 12 | 19.05 % |

| Prefer not to say | 5 | 7.94 % |

| Geographic Location | ||

| North Carolina | 46 | 73.02 % |

| Other US (CT, FL, MI, NJ, NY, OH, PA, TN, TX, VA, WA, Washington DC) | 15 | 23.81 % |

| West Indies | 1 | 1.59 % |

| Canada | 1 | 1.59 % |

Interested participants received a link to an electronic consent and set of baseline surveys to complete online via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). Baseline assessments included measures of resilience, perceived stress, depressive symptoms, post-traumatic growth, and personal COVID-19 impact. Participants then participated in a weekly writing class delivered virtually via Zoom for 6 weeks in June and July 2020. After the final writing session and one month post-intervention, participants were asked to complete assessments of resilience, perceived stress, depression symptoms, and post-traumatic growth.

-

d.Intervention

-

i.Framework

-

i.

Our 6-week writing intervention was adapted from the Transform Your Health: Write to Heal program, a publicly available expressive writing program offered at Duke Integrative Medicine. The adapted Transform Your Health: Write to Heal program drew heavily from evidence-based resilience-building techniques of positive psychology that were delivered through writing prompts [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]. Prompts were developed to address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. A summary of the full intervention's themes and homework assignments can be found in Supplementa l Table 1.

The first week of the intervention guided participants through the Pennebaker Paradigm [25]. The Pennebaker Paradigm leads writers through four prompts: prompts 1 and 2 dive into the emotional experience of a trauma, while prompts 3 and 4 encourage an exploration of new perspectives. Subsequent weeks each focused on a different theme designed to support participants in cultivating resilience. Themes followed an intentional progression designed to help participants move from expressing difficult emotions about COVID-19 to intentionally cultivating insight, perspective, and growth about the experience of living through the pandemic. Themes included compassion for self and others, forgiveness, gratitude, personal strengths, silver linings, exploring lessons learned, and imagining positive future outcomes. As an example, one prompt invited participants to savor positive moments: “Consider an event, moment, or series of moments in the past few weeks that felt positive or joyful for you, and for the next 20 min, write about your experience in a way that draws out the goodness of it.” At all times, participants were encouraged to respond to the prompts in an emotionally honest way, even if that meant veering from the suggested focus.

Across the 6 weeks, participants engaged in expressive writing (focusing on direct emotional expression); transactional writing (letter-writing); poetic writing (response to and writing of poetry); affirmative writing (focus on acknowledging gifts, strengths, and hoped-for outcomes); legacy writing (naming lessons learned); and mindful writing (writing with mindful awareness of the present moment). After each writing prompt, participants were asked to complete a post-writing survey. The post-writing survey encouraged mindful reflection on the process of writing and the writer's inner emotional experience.

Each week, the final prompt of the session invited participants to engage in “mindful writing.” Mindful writing encourages writers to cultivate a state of compassionate, open-hearted awareness of the present moment, inviting them to describe their experience without judgment. After weeks 1–5, participants were also given the option to complete a brief homework assignment to complement each week's thematic focus, such as a brief mindfulness or gratitude practice.

-

ii.

Logistics

All study activities were conducted virtually via email, REDCap, and Zoom. The study coordinator recorded attendance at each Zoom session. Participants were encouraged to use video during the beginning of each session and in between each writing prompt to promote a sense of being in the virtual “room” together, as well as to provide the facilitator with a visual cue as to participants' progress with the writing exercises. Writing sessions were not recorded. Each week's prompts were sent out via email after the session so that participants who could not make the live virtual session could complete the assignments on their own before the next session.

-

iii.

Facilitator role and qualifications

The program facilitator for the trial has nearly 40 years of experience in designing, teaching, and facilitating expressive writing in academic, clinical, and research settings. He holds a Master of Arts in Teaching (English), a Master of Arts (English), and a Doctorate of Education with post-doctoral specialization in curriculum and instruction for post-secondary writing and literature. In addition, he has studied mindfulness and authored five books, including Wellness & Writing Connections and Expressive Writing: Words that Heal, co-authored with James Pennebaker, PhD [25]. During the intervention, the facilitator's role was to guide participants through the writing prompts and post-writing surveys, and to manage session time-keeping. In a few of the sessions, when time permitted, the facilitator guided a brief discussion at the end of all of the writing prompts, inviting participants to reflect on their writing experience.

-

e.

Measures

Primary outcome: resilience. The primary outcome was assessed with the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), a validated 25-item scale to measure resilience assessed in numerous populations [26].

2.1. Secondary outcomes

Depressive symptoms. Depression symptoms were assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale – Revised (CESD-R), a common screening tool to assess self-reported depressive feelings and behaviors within the past week [27].

Perceived stress. Perceived stress was assessed with the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), a commonly used questionnaire to evaluate responders’ perceptions about their level of stress and their ability to cope with stress over the past month. Using a 4-point Likert-type scale, participants selected the degree to which each item best reflects their thoughts and feelings within the past month. Results from this questionnaire have demonstrated acceptable levels of validity and reliability [28].

Post-traumatic growth. Post-traumatic growth was evaluated with the 21-item Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PGTI), an instrument for assessing positive outcomes reported by individuals who have experienced traumatic events. The PTGI includes factors such as New Possibilities, Relating to Others, Personal Strength, Spiritual Change, and Appreciation of Life [29].

-

f.

Data collection and analysis

Enrollment, retention, and adherence data were tracked by the study coordinator using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Other study data were collected directly from the participants via surveys administered in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, web-based electronic research data capture tool hosted by Duke University [30]. Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio Version 1.2.1335. Two-tailed paired-sample t-tests were used to assess change over time while the level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 (p < 0.05). Effect sizes are presented using Cohen's d. Cohen's d values suggested that d = 0.2 be considered a small effect size, 0.5 represents a medium effect size, and 0.8 a large effect size.

3. Results

-

a.

Sociodemographics

The study participants (n = 63) were predominantly white (87.3 %) and female (88.9 %) ( Table 1 ). 31.7 % of participants had obtained a bachelor's degree, and 57.2 % held a master's or doctorate-level graduate degree. 19.1 % of participants reported annual household income less than $50,000 per year, 30.2 % reported an income of $50,000-$99,999 per year, and 42.8 % reported annual household income of over $100,000 per year.

-

b.

Enrollment and retention

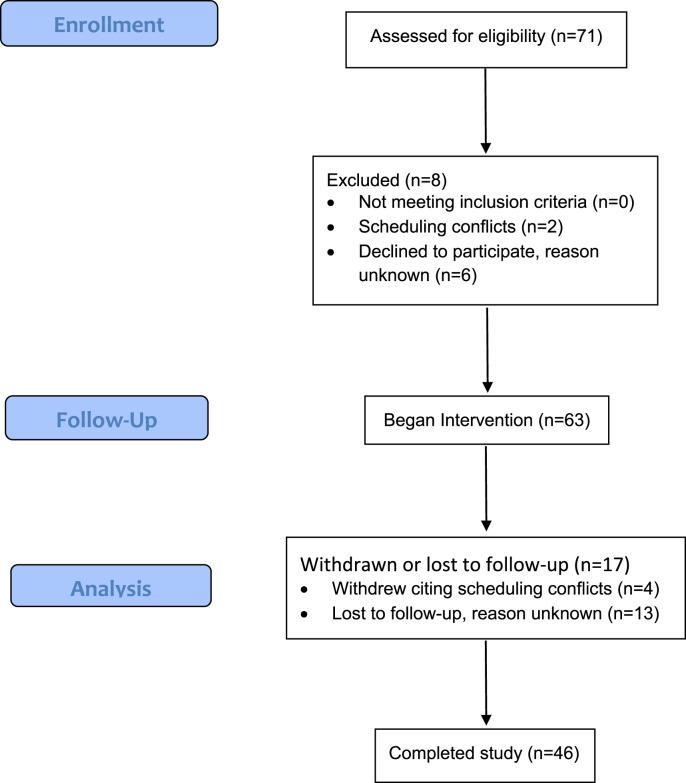

123 participants responded to the study recruitment email, and 71 completed full baseline screening measures. The majority of individuals who chose not to participate cited scheduling conflicts. 63 participants began the intervention and were included in the baseline analysis. 4 individuals withdrew from the intervention shortly after it began due to scheduling conflicts, and 13 were considered lost to follow-up. 46 individuals were considered to have completed the study. See Fig. 1 for CONSORT flow diagram.

-

c.

Adherence

Fig. 1.

CONSORT 2010 flow diagram.

Adherence to the intervention was defined by participants' completion of the writing prompts as indicated by (1) attendance of the live writing sessions and (2) completion of the post-writing surveys. If a participant either attended a writing session via Zoom and/or sent in completed post-writing survey forms for that session (even if they were unable to make the session live), they were considered to have participated in that session. Writing sessions were not recorded in order to protect participants’ privacy.

A participant was considered adherent if they completed at least 5 out of the 6 writing sessions. 63 participants completed at least 1 writing session, and 43 (68.3 %) were considered adherent to the intervention.

-

d.

Acceptability

No adverse events were reported. Participant responses to the question, “to what degree was the writing meaningful and valuable for you” averaged 8.0 on a 0- to 10-point scale for all types of writing. See Table 2 for scores on specific types of writing. Participants also shared their reflections on the writing activities, expressing their satisfaction, emotions, and feelings during the intervention. Sample comments from participants are reported in Table 3 as an informal demonstration of the acceptability of the intervention.

-

e.

Preliminary efficacy

Table 2.

Acceptability Ratings: Meaningfulness and Value of the Writing Exercises. Participants used a scale of 0–10 to answer, “To what degree was the writing meaningful and valuable for you?”.

| Intervention Week | Week 1: Pennebaker Paradigm | Week 2: Releasing & Integrating Difficult Emotions | Week 3: Nurturing Gratitude | Week 4: Embracing Strengths & Resources | Week 5: Cultivating Positive Meaning & Savoring Goodness | Week 6: Inviting Insight, Perspective, & Growth | Overall Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Rating (SD) | 7.7 (2.04) | 8.3 (1.74) | 8.1 (2.17) | 7.8 (2.15) | 8.0 (1.73) | 8.1 (1.78) | 8 (1.94) |

| Mean N | 50.5 | 41.7 | 39.3 | 39.3 | 38 | 35.7 | 40.8 |

*Mean N refers to the mean number of post-writing surveys that were turned in by participants each week.

Table 3.

Representative participant comments.

| Intervention Week | Participant Comments |

|---|---|

| Week 1: Writing to express difficult emotions |

|

| Week 2: Writing to release & integrate difficult emotions |

|

| Week 3: Writing to nurture gratitude |

|

| Week 4: Writing to invite enhance strengths & resources |

|

| Week 5: Writing to cultivate positive meaning & savor goodness |

|

| Week 6: Writing to invite insight, perspective, & growth |

|

We hypothesized that (a) participants’ resilience and post-traumatic growth scores will increase and (b) perceived stress and depression symptoms scores will decrease immediately after the 6-week intervention and at one-month follow-up. See Table 4 for instruments to measure primary and secondary psychological outcomes.

-

I.

Primary outcome: resilience

Table 4.

Primary and secondary outcomes.

| Outcome | Measure | # of Items | Scale | Range | High Score Means | Time Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | CD-RISC | 25 | 0 (Not true at all) to 4 (True nearly all of the time) | 0–100 | Greater resilience | T1, T2, T3 |

| Depression Symptoms | CESD-R | 20 (4 reverse- score items) | 0 (Not at all or less than one day) to 4 (Nearly every day for 2 weeks) | 0–60 | ≥16 = risk for clinical depression | T1, T2, T3 |

| Perceived Stress | PSS-10 | 10 (4 reverse-score items) | 0 (Never) to 4 (Very often) | 0–40 | Higher perceived stress | T1, T2, T3 |

| Post-traumatic Growth | PTGI | 21 (5 factors: Relating to others; New possibilities; Personal strength; Spiritual change; Appreciation of life) | 0 (I did not experience this change as a result of my crisis) to 5 (I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my crisis) | 0–105 | Higher level of PTG | T1, T2, T3 |

CD-RISC scores increased from baseline (66.6 ± 14.9) to immediately post-intervention (73.0 ± 12.4; p = 0.014), and were maintained at a one-month follow-up (72.9 ± 13.6, p = 0.024). The effect size immediately post-intervention (6 weeks) was small (Cohen's d = 0.31) as well as at one-month follow-up (10-weeks; Cohen's d = 0.28).

-

II.

Secondary outcomes

Perceived stress: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) scores decreased from baseline (21.8 ± 6.6) to immediately post-intervention at 6 weeks (18.3 ± 7.0; p = 0.008), and decreased further at the 1-month follow-up (16.8 ± 6.7; p = 0.0002). The effect size immediately post-intervention at 6-weeks was small (Cohen's d = 0.41), and became medium at 1-month follow-up (10-weeks; Cohen's d = 0.56).

Depression symptoms: Depression symptoms (CESD-R) descriptively decreased from baseline (23.3 ± 15.3) at follow-up timepoints 6 weeks (17.8 ± 15.4; p = 0.058), and 1 month post-intervention (15.5 ± 12.7; p = 0.004). The effect size immediately post-intervention at 6 weeks was small (Cohen's d = 0.22), as well as at 1-month follow-up (10-weeks; Cohen's d = 0.38).

Post-traumatic growth: Post-traumatic growth (PTGI) increased from baseline (41.7 ± 23.4) to immediately post-intervention (55.8 ± 26.4; p = 0.004), and the increase was maintained at the 1-month follow-up (55.9 ± 29.3; p = 0.008). The effect size immediately post-intervention at 6 weeks was small (Cohen's d = 0.44), as well as at 1-month follow-up (10-weeks; Cohen's d = 0.49).

COVID-19 impact: At baseline, 23.8 % of participants reported having had a close family member with COVID-19, 36.5 % had lost income or work since the beginning of the pandemic, and 55.6 % had experienced significant changes in work arrangements. 9.5 % of participants had experienced the loss of a loved one due to COVID-19, and 19.0 % reported having lost access to health care or mental health care. 50.8 % of participants reported other serious pandemic-related disruptions, such as caring for elderly family members, significant social isolation, fear of contracting COVID-19, and secondary trauma due to working on the front lines of mental health care.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of a 6-week expressive writing intervention to improve resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results demonstrate that the intervention increased resilience and post-traumatic growth while decreasing depression symptoms and perceived stress, results which were maintained at a 1-month follow-up after completion of the intervention. 68.3 % of participants were considered adherent to the intervention and responded to follow-up surveys at the 6- week and 1-month post-intervention time points. The use of a virtual conferencing platform (Zoom) to deliver the expressive writing intervention was successful and well-accepted by participants. Some participants experienced technical challenges with the Zoom interface at the beginning of the study, but the issues were resolved quickly and no further issues persisted. Overall, participants reported that the writing exercises were valuable and meaningful to them in post-writing surveys, which is consistent with our prior in-person study of expressive writing [12]. Thus, these results suggest that expressive writing based on the Transform Your Health: Write to Heal program and adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic can be feasibly and effectively delivered using an online virtual platform.

The COVID-19 pandemic is associated with worsening mental health, increasing the prevalence of depression and anxiety [31]. The mean baseline depression score for our participants was above the threshold for risk of clinical depression [32] and the mean baseline resilience score was comparable to that of trauma survivors [12]. During the first 2 weeks of our expressive writing intervention participants were encouraged to write about difficult or negative emotions related to the pandemic. Expressive writing about challenging events has been found to be more effective at easing negative dimensions of mental health than emotionally neutral fact-based writing and is correlated with post-traumatic growth [10,33]. Weeks 3 through 6 of our intervention guided participants through writing prompts that focused on nurturing resilience and positive emotions. Evidence-based positive psychology techniques such as savoring positive moments, reflecting on gratitude, and practicing optimism were adapted to our expressive writing prompts [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24],34].

In post-writing surveys, participants reported that the writing prompts helped them to express deeply held emotions and to thoughtfully examine their perspectives on current events. To date, much of the research on interventions for trauma resilience has focused on adverse events that happened in the past, such as adverse childhood events, sexual assault, or wartime combat. Those studies primarily focus on the role of positive rumination about past experiences, which can lead to meaning-making and post-traumatic growth [35]. On the other hand, our findings offer insight into the impact of expressive writing on resilience during an ongoing trauma. The results of our study are consistent with the findings of similar studies that tested the effects of expressive writing interventions for participants experiencing ongoing trauma. For example, La Marca, Maniscalco [36] reported that expressive writing successfully decreased the psychiatric symptoms and alexithymia (i.e., loss of abilities identifying or describing emotions) and increased health-related quality of life of first-time cancer diagnosis patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Future studies can apply expressive writing interventions to broader populations and test their effectiveness in diverse situations.

Despite the fact that most of the psychological variables we measured improved across the program, the effect sizes were relatively small [28]. Nonetheless, our Cohen's effect sizes for resilience, depression, stress, and post-traumatic growth are consistent with prior expressive writing studies [12,37]. It is possible that a more homogeneous patient population, as observed in our prior study in trauma patients, may be more amenable to large effect sizes, and that broadening the patient population to a more general population decreases this effect [12]. Different effect sizes may also be due to heterogeneity in gender differences, timing of assessment, and differences in the severity of traumatic events. The homogeneity of participants may help delivering more tailored, situationally appropriate interventions to the target group. For example, participants may feel more comfortable writing in a group with similar traumatic experiences. Additional studies of expressive writing in more homogeneous patient populations are warranted to evaluate this discrepancy. We may also conduct future studies with participants having a similar baseline level of resilience or other psychosocial functions and test the effects of the online expressive writing intervention.

Several expressive writing studies have been conducted during COVID-19 with the aim to improve response to stress [38,39]. The results of those expressive writing studies during the COVID-19 pandemic have been mixed. One study on expressive writing for health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic found that participants who received a writing intervention showed higher improvements in PTSD, depression, and global psychopathology symptoms than participants assigned to a neutral writing control group [40]. On the other hand, one randomized study reported increased stress with expressive writing compared to treatment as usual, suggesting that expressive writing may at times lead to less than favorable outcomes [38]. Our study may have had different results because our intervention differs from other intervention programs in several aspects, including the expressive writing approach, study duration, and outcomes assessments. Thus, a longer study duration, larger sample size, and multi-center approach combined with the Transform Your Health: Write to Heal program structure may provide a more rigorous and effective study design. Further research should be conducted to develop an optimized expressive writing intervention tailored to the unique needs of people who are influenced by the multidimensional challenges of COVID-19.

4.1. Limitations

Limitations include a patient sample that was relatively homogenous in terms of race and gender: our cohort was mostly white, mostly female, and highly educated, and results may not necessarily be generalizable to a wider population. Our inclusion criteria were broad, as we did not specify how participants had to have been affected by the pandemic in order to participate, and this may have limited the homogeneity of our sample. Many participants expressed unsettled feelings by the racial protests in the aftermath of George Floyd's murder in late May 2020, which may have added an unexpected confounding variable of stress throughout the study period. There was no control group and no randomization, given the preliminary nature of this work. As we used a one-group pretest-posttest design, we cannot guarantee that the quality of the intervention maintained to our usual face-to-face program or that the impacts of this intervention were perceived in the same way by participants. Finally, participants were a self-selected group of individuals who were likely already interested in expressive writing and complementary approaches to health and well-being, potentially adding bias and confounding to our results.

5. Conclusions

This is one of the earliest trials of expressive writing conducted for resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. While previous research on expressive writing for resilience to a trauma has largely focused on incidents that happened in the past, our study sheds light on the prospective impact of expressive writing on mental well-being in the midst of an ongoing trauma. Study participants significantly improved their resilience, depression symptoms, perceived stress, and post-traumatic growth over the course of 6 weeks that was maintained one month after the intervention. Our findings also affirm the feasibility of administering an expressive writing intervention online, which has valuable implications in the context of pandemic-related physical distancing guidelines. Expressive writing is an accessible, scalable, low-burden, and cost-effective intervention that may have wide relevance to the general population throughout the extended COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Further studies are warranted to examine the impact of expressive writing in the context of COVID-19 in more racially diverse samples and in sub-populations such as frontline health care workers or COVID-19 survivors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Elizabeth Bechard: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Project administration. John Evans: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Eunji Cho: Writing – review & editing. Yufen Lin: Writing – review & editing. Arthi Kozhumam: Writing – review & editing. Jill Jones: Writing – review & editing. Sydney Grob: Writing – review & editing. Oliver Glass: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded internally by Duke Integrative Medicine in Durham, North Carolina. We would like to acknowledge the participants of this study, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101460.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Huang C., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. 10223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization . 2021. W.H. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.https://covid19.who.int [cited 2021 March 18]; Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong R.A., Kane A.D., Cook T.M. Outcomes from intensive care in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(10):1340–1349. doi: 10.1111/anae.15201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coperchini F., et al. The cytokine storm in COVID-19: an overview of the involvement of the chemokine/chemokine-receptor system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020;53:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serafini G., et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM. 2020;113(8):531–537. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfefferbaum B., North C.S. Mental health and the covid-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(6):510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu J., et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2) doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gobbi S., et al. Worsening of preexisting psychiatric conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatr. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.581426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrington S.J., Morrison O.P., Pascual-Leone A. Emotional processing in an expressive writing task on trauma. Compl. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018;32:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smyth J.M., Hockemeyer J.R., Tulloch H. Expressive writing and post-traumatic stress disorder: effects on trauma symptoms, mood states, and cortisol reactivity. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2008;13(Pt 1):85–93. doi: 10.1348/135910707X250866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirai M., et al. An investigation of the efficacy of online expressive writing for trauma-related psychological distress in Hispanic individuals. Behav. Ther. 2012;43(4):812–824. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glass O., et al. Expressive writing to improve resilience to trauma: a clinical feasibility trial. Compl. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019;34:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Southwick S.M., et al. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014:5. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santarone K., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Preserving mental health and resilience in frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020;38(7):1530–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayer N.A., et al. Randomized controlled trial of online expressive writing to address readjustment difficulties among U.S. Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans. J. Trauma Stress. 2015;28(5):381–390. doi: 10.1002/jts.22047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherman K.A., et al. Reducing body image-related Distress in women with breast cancer Using a structured online writing exercise: results From the my changed body randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36(19):1930–1940. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halpert A., Rybin D., Doros G. Expressive writing is a promising therapeutic modality for the management of IBS: a pilot study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010;105(11):2440–2448. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirai M., et al. An investigation of the efficacy of online expressive writing for trauma-related psychological distress in hispanic individuals. Behav. Ther. 2012;43(4):812–824. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant F.B., Veroff J. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. Savoring: A New Model of Positive Experience. [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Leary K., Dockray S. The effects of two novel gratitude and mindfulness interventions on well-being. J. Alternative Compl. Med. 2015;21(4):243–245. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seligman M. Atria Books; New York: 2012. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pennebaker J.W., Chung C.K. In: Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. Friedman H.S., editor. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2009. Expressive writing and its links to mental and physical health. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seligman M. Vintage Books; , New York: 2011. Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rendon J. Touchstone<x>; , New York: 2015. Upside: the New Science of Post-Traumatic Growth. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pennebaker J. New Harbinger Publications, Inc; Oakland, CA: 2004. Writing to Heal. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connor K.M., Davidson J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) Depress. Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eaton W., Ybarra C.S.M., Muntaner C., Tien A., Maruish M., Mahwah N.J. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2004. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment: Instruments for Adults. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and Revision (CESD and CESD-R) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tedeschi R.G., Calhoun L.G. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris P.A., et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiong J., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niles A.N., et al. Randomized controlled trial of expressive writing for psychological and physical health: the moderating role of emotional expressivity. Hist. Philos. Logic. 2014;27(1):1–17. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.802308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakhssi F., et al. The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatr. 2018;18(1):211. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1739-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roepke A.M., et al. Randomized controlled trial of SecondStory, an intervention targeting posttraumatic growth, with bereaved adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2018;86(6):518–532. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.La Marca L., et al. Efficacy of Pennebaker's expressive writing intervention in reducing psychiatric symptoms among patients with first-time cancer diagnosis: a randomized clinical trial. Support Care Canc. 2019;27(5):1801–1809. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4438-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frisina P.G., Borod J.C., Lepore S.J. A meta-analysis of the effects of written emotional disclosure on the health outcomes of clinical populations. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2004;192(9):629–634. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000138317.30764.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vukcevic Markovic M., Bjekic J., Priebe S. Effectiveness of expressive writing in the reduction of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.587282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikocka-Walus A., et al. Expressive writing to combat distress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in people with inflammatory bowel disease (WriteForIBD): a trial protocol. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020;139 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Procaccia R., et al. Benefits of expressive writing on healthcare workers' psychological adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021:12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.624176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.