Abstract

COVID-19 was first recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in December 2019 and declared a global pandemic in March 2020. Although COVID-19 primarily results in pulmonary symptoms, it is becoming apparent that it can lead to multisystemic manifestations. Liver damage with elevated AST and ALT is seen in patients with COVID-19. Although the etiology of liver damage is still debated, biliary damage is rarely seen. This case demonstrates a potential complication of COVID-19 in a previously healthy patient. The patient contracted COVID-19 in March 2020 and endured a complicated course including intubation, multiple readmissions, and chronic abdominal pain. He is now awaiting a liver transplant. Our case portrays biliary damage as an additional possible complication of COVID-19 and the importance of imaging in its diagnosis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Hepatobiliary, Cholangiopathy, Secondary sclerosing cholangitis

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome – Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO).1 In March 2020, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared a global pandemic with more than 2 million confirmed cases by April 16, 2020.2 SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the betacoronavirus family, like its predecessors Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and SARS-CoV.3 Since December of 2019, COVID-19 has become an unprecedented global health threat and challenge. According to the CDC there have been 33,395,620 cases of COVID-19 in the US with 600,086 associated deaths by 6/24/2021.1., 4. In March 2020, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared a global pandemic with more than 2 million confirmed cases by April 16, 2020.2 SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the betacoronavirus family, like its predecessors Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and SARS-CoV.3 Since December of 2019, COVID-19 has become an unprecedented global health threat and challenge. According to the CDC there have been 33,224,075 cases of COVID-19 in the US with 595,625 associated deaths by 6/10/2021.4

Up to this point, different clinical manifestations of this disease, including fever, cough, sore throat, diarrhea, loss of sense of taste or smell have been reported.2 80% of patients have a mild form of the disease while 5% become critically ill.2 Liver damage is seen in 7.6–39% of patients with COVID-19, with elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) greater than alanine aminotransferase (ALT), implicating the contribution of AST from sources outside the liver.5 There are multiple hypotheses about the cause of liver damage including direct viral damage, indirect inflammatory injury and drug related hepatotoxicity.2 Here we report a case of secondary sclerosing cholangitis likely due to COVID-19.

2. Clinical background

Patient is a 38-year-old previously healthy male (Fig. 1 ) who contracted COVID-19 pneumonia in March 2020. His three-month hospital course was complicated by hypoxic respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy and embolic stroke among others. He was treated with multiple experimental therapies for COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), including hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, and tocilizumab. He was eventually sent to acute rehab, where he improved and was discharged home. Liver function tests (LFTs) were within normal limits upon initial presentation: AST 30 U/L (normal range 10–40 U/L), ALT 34 U/L (normal range 10–45 U/L), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) 81 U/L (normal range 40–120 U/L), and total bilirubin (Tbili) 0.3 mg/dL (normal range 0.2–1.2 mg/dL). He had acute hepatocellular injury early in his hospital course (peak AST 539 U/L, peak ALT 456 U/L) attributed to ischemic hepatitis with rapid resolution. However, a few months later, during the same admission, he developed persistent and severe cholestasis with jaundice (peak ALP 3665 U/L peak Tbili 9.8 mg/dL). This prompted a CT of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast which showed mild intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation, periportal edema and a mildly dilated, hyper-enhancing common bile duct (Fig. 2 ). He had multiple subsequent hospitalizations for abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and persistent elevations in ALP and Tbili. Each time symptoms improved with supportive measures.

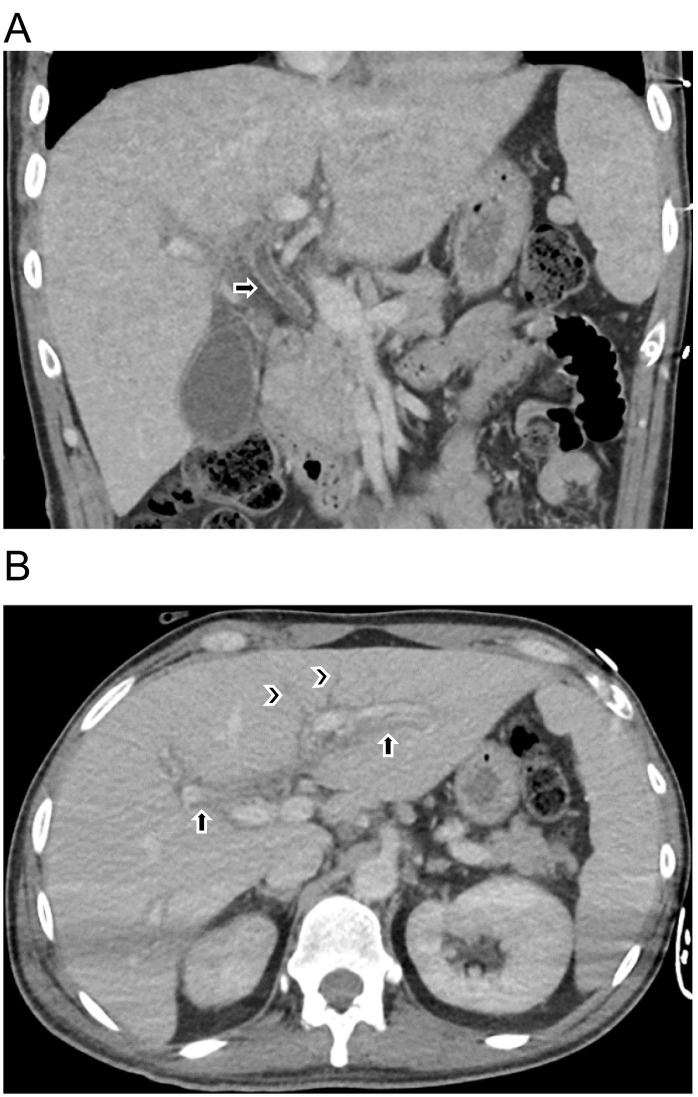

Fig. 1.

Baseline coronal (A) unenhanced CT images showing normal caliber common bile duct (arrow).

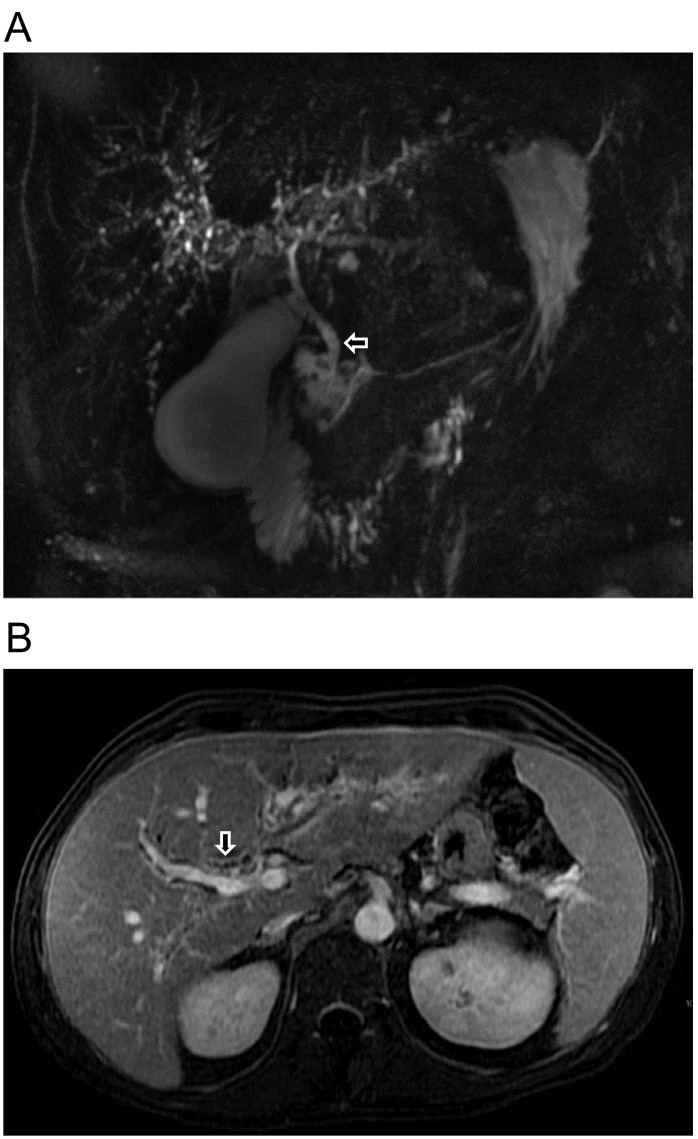

Fig. 2.

(A) Coronal contrast-enhanced CT showing common bile duct dilatation to 8 mm with hyperenhancing wall. (B) Axial contrast-enhanced CT showing intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation (arrowheads) and periportal edema (arrows).

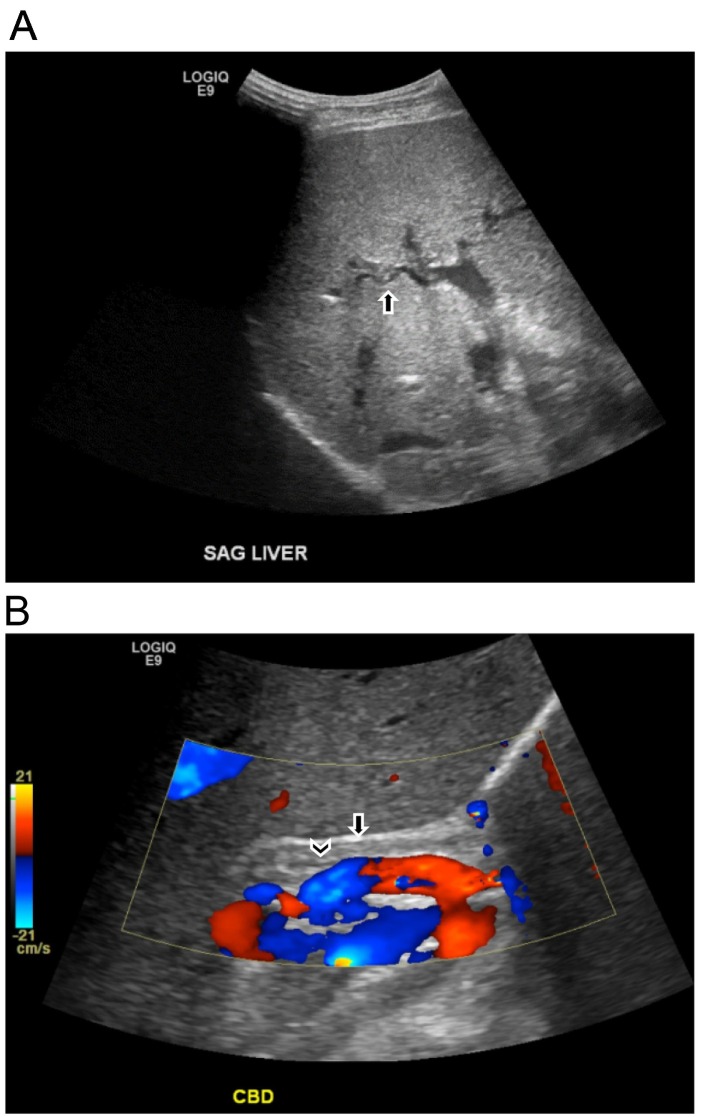

On a subsequent hospitalization in August, the patient underwent MRCP demonstrating normal liver morphology with diffuse mild intrahepatic biliary distention, marked beading and irregularity, as well as mild irregularity of the extra hepatic common bile duct. Diffuse periductal enhancement was also noted (Fig. 3 ). He underwent liver biopsy demonstrating cholestatic hepatitis with cholangiocyte injury, bile ductular proliferation, canalicular cholestasis, a bile lake and disrupted architecture in the form of focal bridging fibrosis. A possible diagnosis of secondary sclerosing cholangitis was made and the patient was discharged home with supportive care.

Fig. 3.

(A) MRCP image showing diffuse intrahepatic ductal beading and irregularity of the common bile duct (arrow). (B) Axial contrast-enhanced fat-saturated T1 image showing intrahepatic ductal beading (arrow).

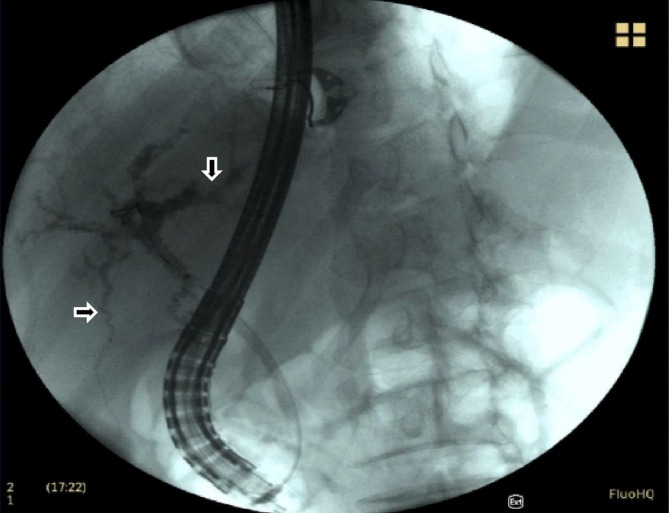

He returned one week later with similar symptoms. The patient underwent an ultrasound showing intrahepatic biliary ductal irregularity and a markedly thickened common bile duct (Fig. 4 ). An ERCP was then performed revealing tortuous and attenuated intrahepatic bile ducts with normal caliber extrahepatic ducts (Fig. 5 ). The patient then began evaluation for liver transplantation.

Fig. 4.

(A) Grayscale ultrasound image showing irregularity of the intrahepatic bile ducts. (B) Color Doppler ultrasound image showing markedly thickened common bile duct wall (arrow) with small-caliber lumen (arrowhead).

Fig. 5.

ERCP image showing tortuous and attenuated intrahepatic bile ducts (arrows) with nondilated extrahepatic ducts.

3. Discussion

COVID-19 is a global pandemic that has spread to many countries beginning early December 2019. Three phases of COVID-19 infection have been described. The initial phase causes mild symptoms that could be mistaken for the common cold or flu. The second phase is the pulmonary phase when respiratory symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath and pneumonia are predominant. Also, hypercoagulability with blood clotting can be seen in Phase 2. The third phase, the hyperinflammatory phase, is when the body damages its own tissues due to the dysregulation of immune responses.5., 6., 7. This maladaptive immune response can result in extensive multi-organ injury.5., 6., 7., 8. The respiratory system is most frequently affected but complications from the SARS-CoV-2 virus can be seen in almost every other organ system.9 The liver is the second most common organ to be damaged by COVID-19.10 This is more common in men and increases with older age.

The exact cause of organ injury is not completely understood and is likely multifactorial. Mild liver disease is manifested in greater than one-third of infected patients. This mild liver dysfunction usually has no clinical symptoms. Rather, mildly elevated AST, ALT and GGT and mild fluctuation of total bilirubin levels are reported.11 The abnormal liver functions tests do not indicate intrahepatic cholestasis and are transient in this early period.

For SARS-CoV-2 to enter a target call and replicate, it needs to bind to the Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. It is thought that viral particles in the bowel lumen may reach the liver via the portal venous system but this deserves further investigation.2 As there is low expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors in hepatocytes, it is thought that damage to liver cells is mainly secondary to immune-related injury from cytokine release. Additionally, in more severe disease, microthrombosis/altered coagulation, hypoxia, sepsis-related abnormalities, damage to adjacent cholangiocytes and drug hepatotoxicity (antiviral drugs and antibiotics) play a role in hepatic injury.12 Patients with underlying liver disease are also at risk for COVID-19 and its complications, including liver injury, as well as progression of their pre-existing liver disorder.4 This includes hepatic steatosis which is an independent risk factor for the more severe form of COVID-19 infection.13

During the third phase of COVID-19, cytokine release directly contributes to the extrapulmonary manifestations as stated above.9 Additionally, cells with increased ACE2 receptor expression are vulnerable to direct viral damage.14 This includes the cholangiocyte, the cell that lines the biliary tree. The cholangiocyte's primary function is to modify hepatocyte derived bile acid. The tight junction formed between adjacent cholangiocytes is essential for bile acid collection and excretion. SARS-CoV-2 can bind to the ACE2 cell receptor directly on the cholangiocyte, as a result disrupting this barrier and bile acid transportation through gene dysregulation. This injury causes bile acid accumulation (cholestasis) and consequent liver damage, which is severe and prolonged.15., 16.

Our patient was previously healthy prior to contracting COVID-19. This is documented with CT imaging performed in 2010 for renal colic. At that time, the liver was normal in size and appearance without biliary pathology (Fig. 1). Early in the course of his COVID-19 infection, our patient had mild hepatocellular injury resulting in elevated LFTs. This was diagnosed clinically as hepatitis and resolved rapidly. Heterogeneous liver parenchyma and periportal edema may be seen on imaging as signs of hepatitis. During our patient's initial markedly prolonged hospitalization which was complicated by lung, heart, kidney and brain manifestations of COVID-19, he developed severe and persistent cholestasis with jaundice. The alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin showed marked elevation. The patient's liver disease changed from an initial hepatocyte injury to a later cholangiocyte injury. CT findings revealed mild biliary dilatation with ductal/periductal enhancement/edema (Fig. 2). MRCP showed irregular intrahepatic ducts with beading and attenuated segments and mild irregularity of the extrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 3). This was followed by an ERCP which removed sludge and imaged similar findings of the intrahepatic ducts and a normal caliber extrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 5). Findings on these above studies suggested a diagnosis of sclerosing cholangitis. Liver biopsy diagnosed cholestatic hepatitis with cholangiocyte injury. The findings were not consistent with primary sclerosing cholangitis or primary biliary cholangitis. Features were not indicative of biliary obstruction. Additionally, hepatocytes were without swelling, and there was no significant lobular inflammation. Steatosis was not seen. Of note, viral inclusions were not seen and immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization for SARS-CoV-2 were both negative. A final pathology report of secondary biliary cirrhosis was issued suggesting a possible COVID-19 etiology. At the time of this publication, the patient was undergoing pre-liver transplantation evaluation.

It is important to further develop an understanding of the patient medications and other confounding factors that may cause cholangiocyte injury in this patient. The patient's medications included azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine and tocilizumab. Azithromycin, like other macrolides, has been linked to a low rate of acute, transient, and asymptomatic elevation of serum aminotransferases, seen in 1–2% of patients treated for short periods.17 In rare situations, it is also linked to symptomatic liver injury. In patients with liver injury, pathology demonstrates bile duct loss which can result in chronic cholestatic liver failure if severe. Additionally, hydroxychloroquine was commonly used in combination with azithromycin for the treatment of COVID-19; however, hydroxychloroquine has not been shown to be a cause of significant liver enzyme abnormalities.18., 19. Tocilizumab, which is also used in COVID-19 treatment, can infrequently cause hepatotoxicity with mild to moderate transaminase elevation. Severe drug-induced liver injury is exceedingly unusual.20., 21.

Our patient's long hospital course in the intensive care unit (ICU) also must be addressed as a plausible cause of the pathologic diagnosis of secondary sclerosing cholangitis. Mechanisms of injury are related to cholestasis of critical illness and hypoxic liver/biliary injury due to circulatory and respiratory impairment requiring ventilatory support.22., 23., 24. This ischemic insult can lead to histopathological abnormalities including cholangiocyte injury.

4. Conclusion

Cholangiocyte injury is a potential late extrapulmonary manifestation of COVID-19. As stated previously, the liver and biliary damage in COVID-19 infection is reasonably thought to be multifactorial in origin. Our case suggests the possibility of direct viral insult to cholangiocytes. Other etiologies are also considered and may have contributed to our patient's cholangiopathy including drug induced liver injury, COVID-19 related inflammatory response and manifestation of extended ICU stay. Biliary disease from COVID-19 infection should be considered when imaging reveals biliary abnormalities in the setting of clinical jaundice, elevated LFTs and cholestasis. We present a case of secondary sclerosing cholangitis diagnosed status post severe COVID-19 infection requiring liver transplantation.

References

- 1.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su T.H., Kao J.H. The clinical manifestations and management of COVID-19-related liver injury. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119(6) doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H., Liu S.M., Yu X.H., Tang S.L., Tang C.K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): current status and future perspectives. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC . June 10, 2021. United States COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Laboratory Testing (NAATs) by State, Territory, and Jurisdiction. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days.https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days Published. [Google Scholar]

- 5.P Zhong J Xu D Yang et al COVID-19-associated Gastrointestinal and Liver Injury: Clinical Features and Potential Mechanisms. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-00373-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Chau A.S., Weber A.G., Maria N.I., et al. The longitudinal immune response to coronavirus disease 2019: chasing the cytokine storm. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(1) doi: 10.1002/art.41526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romagnoli S., Peris A., de Gaudio A.R., Geppetti P. SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: from the bench to the bedside. Physiol Rev. 2020;100(4) doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L.Y.C., Quach T.T.T. COVID-19 cytokine storm syndrome: a threshold concept. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2(2):e49–e50. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30223-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revzin M.v., Raza S., Warshawsky R., et al. Multisystem imaging manifestations of covid-19, part 1: viral pathogenesis and pulmonary and vascular system complications. Radiographics. 2020;40(6) doi: 10.1148/rg.2020200149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Portincasa P., Krawczyk M., Machill A., Lammert F., di Ciaula A. Hepatic consequences of COVID-19 infection. Lapping or biting? Eur J Intern Med. 2020;77 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C., Shi L., Wang F.S. Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5) doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boeckmans J., Rodrigues R.M., Demuyser T., Piérard D., Vanhaecke T., Rogiers V. COVID-19 and drug-induced liver injury: a problem of plenty or a petty point? Arch Toxicol. 2020;94(4) doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02734-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palomar-Lever A., Barraza G., Galicia-Alba J., et al. Hepatic steatosis as an independent risk factor for severe disease in patients with COVID-19: a computed tomography study. JGH Open. 2020;4(6) doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chai X., Hu L., Zhang Y., et al. 2020. Specific ACE2 Expression in Cholangiocytes May Cause Liver Damage After 2019-nCoV Infection. Published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao B., Ni C., Gao R., et al. Recapitulation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and cholangiocyte damage with human liver ductal organoids. Protein Cell. 2020;11(10) doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4) doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bethesda . 2017. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yapali S. What hepatologists need to know about COVID-19? Hepatology Forum. 2020 doi: 10.14744/hf.2020.2020.0011. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda (MD): 2012. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548738/ Hydroxychloroquine. [Updated 2021 Apr 15]. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muhovic D., Bojovic J., Bulatovic A., et al. First case of drug-induced liver injury associated with the use of tocilizumab in a patient with COVID-19. Liver Int. 2020;40(8) doi: 10.1111/liv.14516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatti M., Fusaroli M., Caraceni P., Poluzzi E., de Ponti F., Raschi E. Serious adverse events with tocilizumab: pharmacovigilance as an aid to prioritize monitoring in COVID-19. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87(3) doi: 10.1111/bcp.14459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel K., Zaman S., Chang F., Wilkinson M. Rare case of severe cholangiopathy following critical illness. Case Reports. 2014;2014(sep30 1) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y., Xiao S. Hepatic involvement in COVID-19 patients: pathology, pathogenesis, and clinical implications. J Med Virol. 2020;92(9) doi: 10.1002/jmv.25973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelbmann C.M., Rümmele P., Wimmer M., et al. Ischemic-like cholangiopathy with secondary sclerosing cholangitis in critically ill patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(6) doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]