Abstract

Surveillance for soil-transmitted helminths, strongyloidiasis, cryptosporidiosis, and giardiasis was conducted in Mississippi, USA. PCR performed on 224 fecal samples for all soil-transmitted helminths and on 370 samples for only Necator americanus and Strongyloides stercoralis identified 1 S. stercoralis infection. Seroprevalences were 8.8% for Toxocara, 27.4% for Cryptosporidium, 5.7% for Giardia, and 0.2% for Strongyloides parasites.

Keywords: Soil-transmitted helminths, Strongyloides, strongyloidiasis, Toxocara, toxocariasis, Cryptosporidium, cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis, parasites, pediatric, zoonoses, Mississippi, United States

Human populations in the state of Mississippi and the rest of the southeastern United States have historically been at risk for hookworm and other parasitic diseases (1,2). With improved sanitation and economic development, soil-transmitted helminths (STH), including the hookworms Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura, were presumed to have been eliminated. However, a recent report of continued hookworm and strongyloidiasis transmission in a community without access to proper sanitation in Alabama, USA, has challenged this assumption (3).

The Study

To investigate the current prevalence of these infections, we conducted a pilot study to identify STH and other potentially endemic parasitic infections in convenience samples of specimens collected from patients in Mississippi. We deidentified fresh fecal samples submitted for diagnostic testing from patients at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC; Jackson, Mississippi, USA) during March 30, 2017–February 22, 2018, and serum samples submitted during October 28, 2017–March 29, 2018. This study was approved by the UMMC Institutional Review Board; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was determined to be nonengaged and therefore did not undertake a separate institutional review board review.

We froze two 250-mg aliquots of feces for later DNA extraction. Where sample volume allowed, we performed microscopic examination using the saturated salt (specific gravity 1.2) passive flotation method as previously described (4). We extracted DNA by using the SurePrep Soil DNA isolation kit (ThermoFisher, https://www.thermofisher.com) after conducting initial bead beating for 3 minutes using zirconium beads. We stored DNA extracts at −80°C and sent them to the CDC for real-time PCR analysis. At CDC, each sample was initially tested for inhibition and poor DNA extraction by a real-time PCR assay targeting the human cytochrome B gene (5). Samples positive by this inhibition and extraction control were then tested by multiparallel real-time PCR for STH (6). A cycle threshold (Ct) <35 was considered to represent a positive result. Any positive PCR results were confirmed by duplicate testing.

We froze the deidentified serum samples at –80°C and sent them to CDC, where they were tested for antibodies to Toxocara spp., S. stercoralis, Cryptosporidium spp., and G. duodenalis using MAGPIX multiplex serology (ThermoFisher) (Appendix) to detect evidence of prior exposure. For statistical calculations, we used Excel (Microsoft, https://www.microsoft.com) and R version 3.3.1 (https://www.r-project.org).

A total of 650 fecal samples were obtained from UMMC patients. The median age of patients providing fecal samples for this analysis was 56 years (range 2–95 years). We obtained samples sufficient to perform saturated salt centrifugal flotation on 507 samples (80%). We found no samples to contain helminth eggs or larvae. Sufficient sample for DNA extraction was available for 631 (99.5%) samples. Of these fecal DNA extracts, a negative inhibition and extraction control excluded 37 samples. We tested 224 DNA extracts for Ancylostoma spp., N. americanus, S. stercoralis, A. lumbricoides, and T. trichiura by real-time PCR. (Table 1)

Table 1. Results of microscopic examination and real-time PCR testing for soil-transmitted helminth and Strongyloides stercoralis infection on postdiagnostic fecal samples from patients at University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA*.

| Method | Inhibition and extraction control | S. stercoralis | Necator americanus | Ascaris lumbricoides | Trichuris trichiura | Ancylostoma spp. | Other parasite species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated salt centrifugal flotation | NA | 0/507 (0) | 0/507 (0) | 0/507 (0) | 0/507 (0) | 0/507 (0) | 0/507 (0) |

| Real-time PCR |

594/631 (94.1) |

1/594 (0.2) |

0/594 (0) |

0/224 (0) |

0/224 (0) |

0/224 (0) |

NA |

| *Values are no. (%) unless indicated. NA, not applicable. | |||||||

Because prior work in Alabama (3) detected only N. americanus and S. stercoralis infections, we screened an additional 370 DNA extracts for these helminths only. Of these 370 samples, 2 DNA extracts yielded positive amplicons for S. stercoralis (Ct 29.57 and 30.48). The first of these samples (Ct 29.57) yielded no amplification curve on repeat testing and was interpreted as representing an initial false-positive result. The second sample (Ct 30.48) was positive upon confirmatory retesting (Ct 28.52 and 30.49). (Table 1)

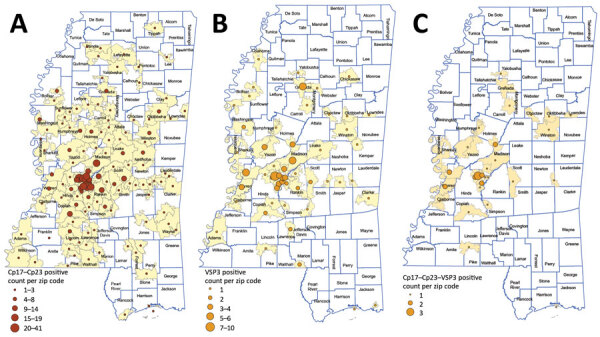

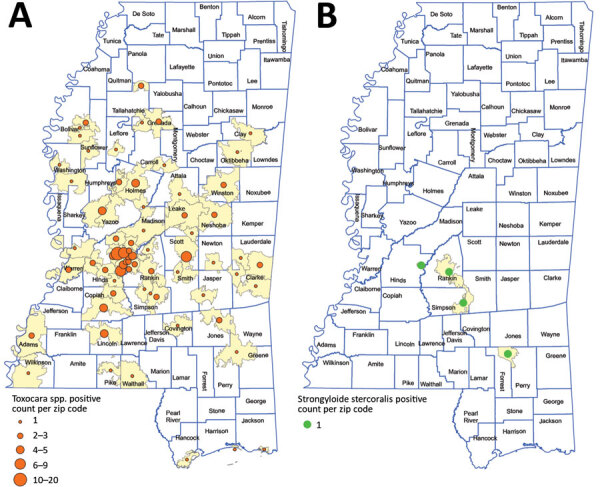

A total of 1,960 postdiagnostic serum samples from Mississippi residents were available for multiplex serologic testing. The median age of patients providing serum samples for this analysis was 38 years (range 0–94 years). Of the 1,960 samples, 646 (33.0%) reacted with the Cp17 antigen of C. parvum (range 87–48,448 mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]), and 1,076 (54.9%) reacted with Cp23 (range 377–56,727 MFI). Of those samples, 538 (27.4%) reacted with both C. parvum antigens (Figure 1, panel A), suggesting prior Cryptosporidium species infection. A total of 111 samples (5.7%) reacted with the G. duodenalis VSP3 antigen (range 84–48,547 MFI) (Figure 1, panel B). A total of 38 (1.9%) samples contained antibodies to the Cp17, Cp23 and VSP3 antigens (Figure 1, panel C), demonstrating prior exposure to both Cryptosporidium and G. duodenalis infections. A total of 172 (8.8%) samples contained antibodies to Toxocara spp. Tc-CTL-1 antigen (range 23.2–33,814 MFI) (Table 2; Figure 2, panel A). When Toxocara-seropositive participants <6 years of age were excluded, 167/1,814 (9.2%) of UMMC patient samples were seropositive. A total of 9 (0.4%) samples contained antibodies reacting with the recombinant S. stercoralis NIE-1 antigen (range 16.2–11248 MFI) in MAGPIX serologic testing, of which 4 (0.2%) were positive in the confirmatory S. stercoralis CrAg-ELISA (range 9.94–57.7 IU/mL) (Figure 2, panel B).

Figure 1.

Places of residence of participants with antibody levels suggesting prior exposure to Cryptosporidium spp. Cp17 and Cp23 (n = 538) (A), Giardia duodenalis VSP3 (n = 111) (B), and Cryptosporidium spp. Cp17 and Cp23 and Giardia duodenalis VSP3 (combined) (n = 38) (C), Mississippi, USA. All serologic assays were performed using MAGPIX multiplex recombinant antigen beads (ThermoFisher, https://www.thermofisher.com) on convenience serum samples collected at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (Jackson, MS, USA) during October 28, 2017–March 29, 2018. Only those samples confirmed by a subsequent S. stercoralis crude L3 larval antigen (CrAg) ELISA are included.

Table 2. Results of multiplex serologic testing for antibodies suggesting prior exposure to Toxocara spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Cryptosporidium spp. on 1,960 postdiagnostic serum samples from patients at University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA*.

| Parasite antigen used | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Toxocara spp. Tc-CTL-1 |

S. stercoralis rSs-NIE-1 plus CrAg-ELISA† |

G. duodenalis

VSP3 |

C. parvum Cp17 |

C. parvum Cp23 |

C. parvum Cp17 + Cp23‡ |

C. parvum Cp17 + Cp23 and G. duodenalis VSP3 |

| 172 (8.8) | 4 (0.2) | 111 (5.7) | 646 (33.0) | 1,076 (54.9) | 538 (27.4) | 38 (1.9) |

*All values are no. (%). †8 samples were found to be positive by the rSs-NIE-1 MAGPIX multiplex serologic assay (ThermoFisher, https://www.thermofisher.com), but only 4 reacted in the confirmatory S. stercoralis crude L3 larval antigen (CrAg) ELISA. ‡Only samples reactive to both Cp17 and Cp23 were considered positive for Cryptosporidium spp. exposure.

Figure 2.

Places of residence of participants with antibody levels suggesting prior exposure to Toxocara spp. Tc-CTL-1 (n = 172) (A) and Strongyloides stercoralis Ss-NIE-1 (n = 4) (B) , Mississippi, USA. All serologic assays were performed using MAGPIX multiplex recombinant antigen beads (ThermoFisher, https://www.thermofisher.com) on convenience serum samples collected at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (Jackson, MS, USA) during October 28, 2017–March 29, 2018. Only those samples confirmed by a subsequent S. stercoralis crude L3 larval antigen (CrAg) ELISA are included.

Conclusions

The results of this limited pilot study suggest a low prevalence of STH infections in Mississippi but that rare infections with S. stercoralis might be found in Mississippi residents. The single case confirmed by real-time PCR tests likely represents active infection. Because >80% of patients with strongyloidiasis serorevert within 18 months after successful treatment (7), the 4 confirmed antibody-positive serum samples also likely represent active cases of strongyloidiasis. No linked immigration or travel history data on patients providing these samples were available, so whether these infections were acquired within the United States is unknown. Combined with the recent finding of strongyloidiasis in a rural community from Alabama (3), these data should encourage more focused sampling of areas with poor sanitation and hygiene, high levels of poverty, and poor access to healthcare for potential residual foci of endemic STH and strongyloidiasis transmission in Mississippi and the wider southeastern United States.

The total Toxocara spp. seroprevalence in all participants in this study was 8.8%, which is higher than the average prevalence reported by the most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey study (8). Although these results are not directly comparable because of different sampling methods, the potentially high Toxocara spp. seroprevalence in Mississippi warrants further investigation.

The seroprevalence results of this study suggest that prior exposure to Cryptosporidium spp. is common in Mississippi. Only 5.7% of the postdiagnostic serum samples were found to have serologic evidence of prior exposure to G. duodenalis infection. A small number of samples (1.9%) contained antibodies reacting with the 3 antigens Cp17, Cp23, and VSP3, indicating prior exposure to Cryptosporidium spp. and G. duodenalis infection. Further investigation of the epidemiology of waterborne protozoan infection in Mississippi, including determination of the actual prevalence and distribution using systematic sampling and determination of the species and subtypes infecting persons, is warranted.

The absence of any positive findings by microscopic examination or PCR for the STH suggests that such infections are uncommon in the general Mississippi population. We found high seroprevalence of antibodies to Toxocara spp. in Mississippi. Although this finding could indicate increased exposure to this infectious agent compared with the national average, our data do not enable determination of the sources of increased infection or overall annual incidence of disease. Further studies on the epidemiology and prevalence of parasitic diseases in the state of Mississippi are indicated.

In conclusion, this convenience sampling study did not find evidence of high STH prevalence in Mississippi. However, we did identify several likely current cases of strongyloidiasis and relatively high rates of Toxocara exposure. We recommend further investigation with larger sample sizes to more clearly define the true extent of STH infection in this region.

Additional information about parasitic disease surveillance, Mississippi, USA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Silvia D. Dimitrova for providing coupled beads, buffers, and reagents, as well as critically reviewing this manuscript.

This work was funded by the University of Mississippi Medical Center and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Biography

Dr. Bradbury is a senior lecturer in microbiology and molecular biology at Federation University in Berwick, Victoria, Australia, and is a microbiologist with expertise in laboratory diagnostics and parasitic diseases. His research interests include strongyloidiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, zoonoses, and emerging parasitic diseases. Dr. Hobbs is a professor of pediatric infectious disease and attending physician at Children’s of Mississippi, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA. Her research interests include parasitic diseases in children in resource-limited settings.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Bradbury RS, Lane M, Arguello I, Handali S, Cooley G, Pilotte N, et al. Parasitic disease surveillance, Mississippi, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Aug [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2708.204318

These authors contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Elman C, McGuire RA, Wittman B. Extending public health: the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission and hookworm in the American South. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:47–58. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiles CW. Report upon the prevalence and geographic distribution of hookworm disease (uncinariasis or anchylostomiasis) in the United States. Washington: US Government Printing Office; 1903.

- 3.McKenna ML, McAtee S, Bryan PE, Jeun R, Ward T, Kraus J, et al. Human intestinal parasite burden and poor sanitation in rural Alabama. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:1623–8. 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillespie S, Bradbury RS. A survey of intestinal parasites of domestic dogs in central Queensland. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2017;2:60. 10.3390/tropicalmed2040060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradbury RS, Arguello I, Lane M, Cooley G, Handali S, Dimitrova SD, et al. Parasitic infection surveillance in Mississippi Delta children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:1150–3. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilotte N, Papaiakovou M, Grant JR, Bierwert LA, Llewellyn S, McCarthy JS, et al. Improved PCR-based detection of soil transmitted helminth infections using a next-generation sequencing approach to assay design. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004578. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearns TM, Currie BJ, Cheng AC, McCarthy J, Carapetis JR, Holt DC, et al. Strongyloides seroprevalence before and after an ivermectin mass drug administration in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005607. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu EW, Chastain HM, Shin SH, Wiegand RE, Kruszon-Moran D, Handali S, et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies to Toxocara species in the United States and associated risk factors, 2011–2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:206–12. 10.1093/cid/cix784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional information about parasitic disease surveillance, Mississippi, USA.