Abstract

Extracurricular involvement in the school-age years has widespread potential benefits for children’s subsequent socioemotional development, especially for low-income youth. However, there is a dearth of research on interventions aimed at increasing school-age extracurricular involvement in low-income youth. Thus, the present study aimed to test the collateral effect of a brief, family-focused intervention for low-income families, the Family Check-Up, on children’s school-age extracurricular involvement via improvements in maternal Positive Behavior Support in early childhood. The sample (n = 630, 50% female, 50% White, 28% Black/African American) represented a subsample of families from the Early Steps Multisite Study. At age 2, families were randomly assigned to the Family Check-Up or Women, Infants, and Children Nutritional Supplement Services as usual. Mother-child dyads participated in observed interaction tasks at child ages 2 and 3 that were subsequently coded to assess positive behavior support. Primary caregivers reported on children’s school-age extracurricular involvement at ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5. Results indicated that although there was not a direct path between intervention status and children’s school-age extracurricular involvement, a significant indirect path emerged from intervention group to changes in positive behavior support between ages 2 to 3 to children’s school-age extracurricular involvement. The results are discussed in terms of implications for designing preventive interventions in early childhood that promote extracurricular involvement at school-age, particularly for children at risk for maladaptive outcomes.

Keywords: early childhood, extracurricular, intervention, middle childhood, positive behavior support, supportive caregiving

Extracurricular activities have the potential to benefit youth development in an array of ways. Some benefits are specific to the type of activity, such as physical exercise from sports, creative expression from arts and music, and community engagement from religious or civic groups. More broadly, involvement in extracurricular activities has been proposed to assist with identity development through interactions with peers that permit youth to explore their own values and preferences, as well as to feel a sense of belonging to a group (Feldman & Matjasko, 2005). Extracurricular involvement also permits youth to develop non-academic skills, while providing a sense of mastery and enjoyment. Finally, after-school activities may provide children with opportunities to participate in prosocial activities led by adults who may serve as prosocial role models or mentors, decreasing opportunities for children to socialize with deviant peers and subsequently, engage in antisocial behaviors (Dishion et al., 2002).

Engaging in extracurricular activities may be especially critical for children from low-income families because of their limited access to resources compared to their more advantaged peers (Halpern, 1999; Weininger et al., 2015). After-school activities are believed to help with offsetting negative effects associated with poverty and related family distress in children’s lives, possibly by providing opportunities for participation in enrichment activities that would otherwise be out of reach because of financial constraints (Posner & Vandell, 1999). Furthermore, as children in low-income families are at the highest risk for negative socioemotional and health outcomes (Duncan et al., 2010; G. E. Miller & Chen, 2013), engagement in extracurricular activities may serve as an important protective factor for high-risk youth.

Empirical studies provide support for the benefits of extracurricular involvement on multiple child outcomes during the school-age and adolescent years. Higher levels of extracurricular involvement initiated at school-age have been associated with subsequent socioemotional and academic adjustment during the school-age years (Aumètre & Poulin, 2018; Denault & Déry, 2015; Oberle, Ji, Magee, et al., 2019) and in adolescence (Metsäpelto & Pulkkinen, 2012; Neely & Vaquera, 2017; Oberle, Ji, Guhn, et al., 2019; Vandell et al., 2018). These results also have been evident for adolescents from low-income households. For instance, in a sample of youth from low-income households who were receiving services for mental illness, higher levels of extracurricular involvement were concurrently associated with caregivers’ reports of lower internalizing problems and higher interpersonal strengths (Abraczinskas et al., 2016). In a sample of parents of middle- to late-school-age children in the UK, both working-class and middle-class parents (majority mothers) identified many similar benefits of extracurricular involvement for their children, including having fun, making friends, building self-esteem, and improving social skills (Holloway & Pimlott-Wilson, 2014). In addition, a larger proportion of working-class compared to middle-class parents identified playing in a safe environment as an important benefit of extracurricular activities. Furthermore, in a qualitative, longitudinal study of high-achieving female high school students from low-income backgrounds, all 9 participating students were highly involved in extracurricular activities (Reis & Díaz, 1999). Finally, in a large sample of high school students from low-income, single-parent families, participation in school-sponsored extracurricular activities was associated with longer school enrollment and lower school drop-out, as indicated by school records (Randolph et al., 2004).

Despite theory and evidence that low-income children’s involvement in extracurricular activities promotes their prosocial development, there is a dearth of research focused on identifying factors that would promote school-age children’s involvement in such activities beginning in early childhood. With the exception of studies linking socioeconomic factors to extracurricular involvement, no studies to our knowledge have assessed early childhood individual- or family-level predictors of extracurricular involvement for low-income youth. Furthermore, no studies to our knowledge have tested the direct or indirect effects of early interventions designed to promote children’s involvement in extracurricular activities, regardless of level of socioeconomic risk. The current study sought to help fill the void by examining the potential collateral effects of a family-based preventive intervention delivered in early childhood, the Family Check-Up, on children’s involvement in extracurricular activities during the school-age period within the context of a randomized controlled trial of low-income children living in geographically diverse communities across the United States.

Targeting Early Supportive Caregiving to Promote Higher Levels of Extracurricular Involvement in the Context of Poverty

Although research on early childhood predictors of youth’s extracurricular involvement is lacking, it is likely that early characteristics of the home environment, including early caregiving, contribute to children’s school-age extracurricular involvement. For instance, positive behavior support (PBS) is a parenting construct that comprises high levels of engagement, proactive parenting, warmth, sensitivity, and rewards for positive behaviors (Waller et al., 2015). Although PBS has not been specifically studied in relation to extracurricular involvement, a cross-sectional study of school-aged children found that children’s perceptions of broader supportive caregiving were associated with higher levels of extracurricular involvement (Anderson et al., 2003).

As children mature, mothers must adapt their caregiving behaviors to meet the emerging needs of their children. Although some behaviors remain appropriate over time (e.g., saying “I love you”), others become increasingly inappropriate (e.g., reading a bedtime story) or increasingly important (e.g., helping a child with homework). Thus, mothers high in PBS in early childhood would be expected to show heterotypic continuity in caregiving during the school-age years, adapting their supportive caregiving behaviors to meet the changing needs of the child. Specifically, parents high in PBS in early childhood may be more likely to proactively plan for where their children will spend time after school in the school-age years, avoiding long periods of times during which children would be unsupervised by adults. Furthermore, they may facilitate their children’s involvement in extracurricular activities to promote their social skills, academic competencies, and non-academic abilities. Finally, mothers high in PBS may also be more likely to seek support or otherwise access affordable extracurricular activities for their children. Accordingly, maternal sensitivity has been observed to be moderately stable during age-appropriate tasks at 54 months (e.g., playing with puppets), 1st grade (e.g., play a card game), 3rd grade (e.g., discussion about rules), and 5th grade (e.g., discussion about conflict) (Scott et al., 2018).

Within the context of limited financial resources, the family stress model posits that the distress associated with receiving low levels of income negatively impacts parenting practices and, in turn, child adjustment (Masarik & Conger, 2017). Therefore, children from low-SES backgrounds may face even more obstacles in enrolling in extracurricular activities than higher-SES peers because of limited financial and community resources coupled with lower levels of supportive caregiving that would promote extracurricular involvement. However, PBS has not been assessed as an early childhood predictor or intervention target to increase children’s school-age extracurricular involvement, including for children from low-SES backgrounds.

In general, maternal parenting interventions for low-income families have been associated with a wide array of positive youth outcomes, including higher academic achievement and lower levels of behavior problems from the preschool years (Landry, Smith, Swank, & Guttentag, 2008; Mendelsohn et al., 2018; review: Sandler, Schoenfelder, Wolchik, & MacKinnon, 2011; Weisleder et al., 2016), through school-age (Sanders et al., 2007; Sandler et al., 2011), and adolescence (Long et al., 1994; Sandler et al., 2011). However, despite a number of studies linking improvements in positive parenting during early childhood to children’s positive outcomes, none to our knowledge have examined intervention effects of PBS or related constructs on children’s extracurricular involvement at school-age.

The Family Check-Up Intervention

The Family Check-Up (FCU) is a family-focused intervention that utilizes motivational interviewing and parent management techniques to promote positive development (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007). Following its original use for families with at-risk adolescents (Dishion et al., 2003; Stormshak et al., 2009), the FCU was adapted for use in early childhood, reflecting its optimal utilization during times of developmental (Shaw et al., 2006). Used primarily with families from low-income backgrounds, the early childhood version of the FCU has been found to be associated with improvements in a number of child outcomes from the preschool period through adolescence (Brennan et al., 2013; Connell et al., 2019; Shaw et al., 2016, 2019). One of the primary mediators of these direct and indirect effects has been through improving primary caregiver PBS in toddlerhood which, in turn, has been linked to a wide variety of later child outcomes. These include indirect effects of the FCU via maternal PBS on self-regulation at ages 4 (Shelleby et al., 2012) and 5 (Chang et al., 2015), better academic skills in the preschool and school-age years (Brennan et al., 2013), inhibitory control and language development in the preschool years (Lunkenheimer et al., 2008), lower body mass index in the preschool and school-age years (Smith et al., 2015), and lower problem behaviors across the preschool and school-age years (Dishion et al., 2008, 2014). However, it remains to be seen whether the FCU would be directly related to increases in children’s extracurricular involvement at school-age, or indirectly linked via improvements in PBS between child ages 2 and 3. As extracurricular involvement is itself a positive youth outcome, and may contribute to further positive youth development, it is important to assess if and how the FCU promotes extracurricular involvement in at-risk, low-income youth.

The Current Study

The current study used a randomized controlled trial to test the collateral impact of the FCU (Dishion et al., 2008) on children’s school-age extracurricular involvement. We hypothesized that, similar to other positive school-age outcomes associated with the FCU in the current cohort, intervention effects would be indirect, mediated by improvements in PBS between child ages 2 and 3 (Dishion et al., 2008). These hypotheses were tested on a sample of low-income families who were randomly assigned at age 2 to receive either the FCU or Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) services as usual. We utilized data from direct observations of maternal PBS (ages 2 and 3) and primary caregivers’ reports of youth extracurricular involvement (ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5) to examine these issues.

Method

Participants

Children (n = 630) were drawn from the larger cohort of the Early Steps Multisite study (N = 731). The Early Steps Multisite study is a randomized controlled trial designed to test the effectiveness of the Family Check-Up (FCU) intervention for those using Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Nutritional Supplement centers (Dishion et al., 2008). In 2002 and 2003, families with a child between ages 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months were approached at WIC sites and screened for participation in three diverse communities: Pittsburgh, PA; Eugene, OR; and Charlottesville, VA (Dishion et al., 2008). Families were invited to participate if they scored at or above one standard deviation on measures of at least two out of three of the following domains: child behavior (conduct problems, high-conflict relationships with adults), family problems (maternal depressive symptoms, parenting challenges, parental substance use problems, or teen parent status), and/or low socioeconomic status (i.e., low income and educational attainment). To increase parents’ motivation for intervention, if eligibility criteria were not met for child behavior, scores above the normative mean were required on the Eyberg Inventory for Intensity or Problem factors (Eyberg & Pincus, 1999). A total of 1666 families were approached at WIC centers across the three study sites, 879 subsequently met the eligibility criteria, and 731 agreed to participate in the study. After recruitment, families were randomly assigned to receive the FCU intervention or WIC services as usual (control group). Participants (n = 630) were selected for the current study’s analytic subsample if the child’s mother participated as a primary caregiver at ages 2 and 3.

For the current study’s analytic subsample, the majority of mothers who participated at ages 2 and 3 were biological parents (n = 606, 96%). In addition, half of the children in the current study’s subsample were female (n = 316, 50%). The race and ethnicity of participants in the analytic subsample are presented in Table 1. Chi-square and independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare the analytic subsample to those excluded from the current study. Tests indicated that there were no significant differences in intervention group status, extracurricular involvement (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), child externalizing problems (age 2), household income (age 2 or averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), maternal education (age 2), study site, child gender, child race, or child ethnicity between the included and excluded groups.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables for Treatment and Control Groups

| Variable | Age(s) | n | Mean (SD) | ||

| FCU | Control | FCU | Control | ||

| Positive Behavior Support | 2 | 317 | 313 | −.04 (.62) | .00 (.00) |

| 3 | 317 | 313 | .07 (.81) | .00 (.00) | |

| Extracurricular involvement | 7.5, 8.5, 9.5 | 281 | 288 | 2.43 (1.31) | 2.29 (1.38) |

| Externalizing problems | 2 | 317 | 312 | 20.65 (7.35) | 20.49 (6.95) |

| Household income | 2 1 | 313 | 309 | $20,014 ($11,147) | $19,594 ($12,062) |

| 7.5, 8.5, 9.5 | 280 | 286 | $28,440 ($17,782) | $28,492 ($15,362) | |

| Variable | Group | n (%) | |||

| FCU | Control | ||||

| Study site | Charlottesville, VA | 85 (27%) | 83 (27%) | ||

| Eugene, OR | 116 (37%) | 114 (36%) | |||

| Pittsburgh, PA | 116 (37%) | 116 (37%) | |||

| Child race | White | 157 (50%) | 157 (50%) | ||

| Black/African American | 89 (28%) | 85 (27%) | |||

| Biracial | 43 (14%) | 44 (14%) | |||

| Other | 24 (8%) | 25 (8%) | |||

| Child ethnicity | Hispanic/Latinx | 44 (14%) | 42 (13%) | ||

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 263 (84%) | 266 (85%) | |||

| Unknown | 8 (3%) | 5 (2%) | |||

| Maternal education (age 2) | Did not complete high school | 69 (22%) | 77 (25%) | ||

| High school or GED | 141 (45%) | 118 (38%) | |||

| Partial college/special training | 71 (22%) | 84 (27%) | |||

| 2- or 4-year college degree | 36 (11%) | 34 (11%) | |||

Note. All differences between the FCU and control groups on study variables were not significant.

Age 2 household income was estimated based on a .5 to 10 coding scale, where .5 represented ≤ $4999 and 10 represented ≥ $90,000. A 1-point increase in household income represented a $9999 increase in annual income.

Within the analytic subsample, characteristics of families who contributed data about extracurricular participation at ages 7.5, 8.5, and/or 9.5 (n = 568) were compared to those who did not provide outcome data (n = 62). There were no significant differences in intervention group status, child externalizing problems (age 2), household income (age 2), maternal education (age 2), child gender, child race, child ethnicity, or maternal Positive Behavior Support (ages 2 or 3) between the included and excluded groups. However, families who did not contribute extracurricular involvement data at ages 7.5, 8.5, and/or 9.5 were more likely to live in Charlottesville, VA and less likely to live in Eugene, OR than families who did contribute data for at least one of these ages, χ2(2) = 7.46, p < .05. Furthermore, intervention-by-attrition analyses were conducted to assess for treatment group (i.e., control vs. FCU) differences in rates of attrition. Attrition rates did not significantly differ for the following variables for the intervention versus control groups: child externalizing problems (age 2), household income (age 2 and averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), maternal education (age 2), child gender, child race, or study site.

Procedure

Assessments.

Children and their caregivers were assessed 7 times between child ages 2 and 9.5. The study started at age 2, which is both a challenging time for many parents (e.g., Fagot & Kavanagh, 1993) and period of enhanced malleability for child problem behavior (Shaw & Gross, 2008). For the present study, data from the ages 2, 3, 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5 assessments were used. At ages 2 and 3, mothers participated in 2.5-hour home visits, during which they completed 50 to 55 minutes of videotaped parent-child interactions, demographic interviews, and questionnaires about family functioning (Dishion et al., 2008). Evidence of reliability and construct validity for the early childhood caregiving measures can be found in previous literature (Caldwell & Bradley, 1984; Jabson et al., 2004). Home examiners also completed ratings of parental involvement at ages 2 and 3. At age 2, families were assessed prior randomization (i.e., baseline). Thus, by assessing changes in caregiving across ages 2 to 3, we could assess the impact of the FCU in relation to changes in early caregiving when the underlying behaviors of PBS would be most similar to prior to the intervention (i.e., rather than at later ages). At ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5, families participated in 2- to 3-hour home visits, during which primary caregivers (n = 494, 96% mothers at age 7.5; n = 475, 95% mothers at age 8.5; and n = 483, 94% mothers at age 9.5) completed demographic interviews and questionnaires about their children’s extracurricular involvement. We chose to assess extracurricular involvement in the late school-age years because of the rapidly increasing salience of peer relationships after the preschool years (Rubin et al., 2015). Furthermore, as much of the research on extracurricular involvement with children from low-income backgrounds focuses on adolescence (e.g., Randolph et al., 2004; Reis & Díaz, 1999), we hoped to further our understanding of extracurricular involvement prior to adolescence in high-risk youth.

The Family Check-Up.

The FCU was offered repeatedly through age 10.5 (8 occasions). As described in Lunkenheimer et al. (2008), families randomly assigned to the intervention condition were scheduled to meet with a parent consultant for two or more sessions, depending on the family’s preference. The FCU is a brief, three-session intervention based on motivational interviewing and modeled after the Drinker’s Check-Up (W. R. Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Typically, the three meetings include an initial contact session, an assessment session, and a feedback session (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003). However, to optimize the internal validity of the study (i.e., to prevent differential dropout for intervention and control conditions), the assessments were completed before random assignment results were known to either the research staff or the family. Thus, for the purposes of research only, the sequence of contacts was an assessment (as described earlier), randomization, an initial interview, a feedback session, and potential follow-up sessions. For completing the FCU at the end of the feedback session, families were given a $25 gift certificate that could be used at local stores.

After the initial assessment session, families in the intervention group participated in a “get to know you” meeting during which the FCU consultant explored caregivers’ concerns, focusing on family issues that were currently the most critical to the well-being of the target child. The third meeting involved a feedback session during which the consultant used motivational interviewing strategies to summarize the results of the assessment. An essential objective of the feedback session was to explore the caregiver’s willingness to change problematic caregiving practices, to support existing caregiving strengths, and to identify services appropriate to the family’s needs. At the feedback, the caregiver was offered the choice to engage in follow-up sessions that were focused on caregiving practices, other family management issues (e.g., co-parenting), and contextual issues (e.g., child care resources, marital adjustment, housing, and vocational training). Although FCU consultants recommended appropriate community services according to the particular needs of the family, follow-up sessions most often consisted of ongoing in-person or phone sessions with the consultant.

Measures

Maternal positive behavior support.

Positive behavior support (PBS) scores were created separately for ages 2 and 3 from four separate measurements (Lunkenheimer et al., 2008). The measures were as follows:

1. Maternal involvement.

The involvement section of the Infant/Toddler Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Inventory (Caldwell & Bradley, 1984) was used to capture maternal involvement. The HOME was completed by an experimenter at the end of the in-home assessments at ages 2 and 3. The involvement section comprised three items that were either observed or not observed, resulting in a score of 0 (“none present”) to 3 (“all present”): whether the mother supervised the child closely, talked to the child during daily non-play activities, and provided a layout for the child’s playtime. The three items were summed to create a maternal involvement score, ranging from 0 to 3. The maternal involvement scale demonstrated weak internal consistency at ages 2 (α = .46) and 3 (α = .55) in the analytic subsample, likely due to the few number of items included in the sum score (i.e., only 3 items were based on observation and used). In the present study’s analytic subsample, maternal involvement scores were not significantly different at ages 2 (M = 2.21, SD = .89, range = 0–3) and 3 (M = 2.13, SD = .97, range = 0–3), t(613) = 1.72, p = ns.

2. Positive reinforcement.

A team of 24 undergraduate students coded videotaped family interaction tasks by using the Relationship Process Code (RPC; Jabson, Dishion, Gardner, & Burton, 2004). Coders were trained to a kappa criterion of .70, and coder drift was addressed through regular, random reliability checks. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The positive reinforcement score was derived as the proportional duration of time in seconds that the mother spent prompting and reinforcing her child’s positive behavior, across all observed tasks. The final variable consisted of a summary of the following RPC codes: (a) positive verbal, indicated by verbal support, endearment, or empathy (e.g., “Good job!” “I like your drawing,” “I love you”); (b) positive physical (e.g., hugging, kissing, patting on the back affectionately, giving high fives); (c) verbal suggestions and strategic prompts of positive or constructive activities for the child (e.g., “Why don’t you take a look at that new truck?”), including nonverbal strategies (e.g., mother carries child and sits child amongst researcher’s toys); and (d) positive structure, indicated by direct encouragement or guidance of the child’s task-related behavior such as providing explicit choices in a request for behavior change (e.g., “Do you want to put the cars away first or the dinosaurs first?”) or using imaginative or playful teaching strategies (e.g., singing a clean-up song). Possible positive reinforcement scores range from 0 to 1. In the present study’s analytic subsample, positive reinforcement scores were not significantly different at ages 2 (M = .12, SD = .09, range = 0-.58) and 3 (M = .12, SD = .10, range = 0-.59), t(604) = −.845, p = ns.

3. Engaged interaction.

A second score from the RPC (Jabson et al., 2004) reflected the mother’s neutral but engaged interaction with the child. Engaged interaction captured conversation that maintained interaction and engagement by means of questions, answers, and explanations about routine (i.e., unrelated to task) matters, conversation about the past or present, verbal acknowledgment of another’s statement, agreements or disagreements with another’s statement, good-natured jokes and teasing, and teaching unrelated to the task. Engaged interaction also included physical contact that was helpful, neutral, and nonintrusive, such as holding a child back to ensure the child’s safety or holding a child’s arm to assist the child with an activity. The final engaged interaction score was the proportional duration of time in seconds that the mother spent in engaged, neutral conversation or physical interaction across all the family interaction tasks combined (possible range = 0 to 1). In the present study’s analytic subsample, engaged interaction scores were significantly lower at age 2 (M = .36, SD = .12, range = .01-.68) compared to age 3 (M = .39, SD = .13, range = .09-.88), t(604) = −4.43, p < .001.

4. Proactive parenting.

Proactive parenting was assessed using the Coder Impressions Inventory (Dishion et al., 2004), adapted from the Oregon Social Learning Center Impression Inventory. After microcoding of each videotaped family interaction was completed, coders gave an overall rating on a scale of 1 (“not at all”) to 9 (“very much”) of the mother’s tendency to anticipate potential problems and to provide prompts or structured changes to prevent the child from becoming upset or involved in problem behavior. The following six items were used: parent gives child choices for behavior change whenever possible; parent communicates to the child in calm, simple, and clear terms; parent gives understandable, age-appropriate reasons for behavior change; parent adjusts or defines the situation to ensure the child’s interest, success, and comfort; parent redirects the child to more appropriate behavior if the child is off-task or misbehaves; and parent uses verbal structuring to make the task manageable. The proactive parenting scale demonstrated good internal consistency at ages 2 (α = .84) and 3 (α = .87) in the analytic subsample. In the analytic subsample, proactive parenting scores were significantly lower at age 2 (M = 5.87, SD = 1.46, range = 1.33–9.00) compared to age 3 (M = 6.22, SD = 1.52, range = 1.50–9.00), t(550) = −5.50, p < .001.

School-age extracurricular involvement.

At child ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5, primary caregivers completed the Parent Aftercare Survey (PAS), a 69-item detailed assessment of children’s after-school care. The PAS is adapted from measures used in the Promising After-School Practices Study (Rosenthal & Vandell, 1996). For the present study, the caregiver’s responses on questions regarding whether or not their child participated in various extracurricular activities (e.g., team sports, tutoring, and private lessons) in the past year were used. Thus, school-age extracurricular involvement represented the total score of extracurricular activities the child engaged in during the past year, averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5. If data were missing for one or two of those ages, scores from the non-missing ages were utilized. The proportions of children participating in different types of activities across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5 are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participation in Types of Extracurricular Activities Across Ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5

| Activity Type | n (%) Involved |

|---|---|

| Informal after school care | 415 (73%) |

| Religious classes or services | 365 (64%) |

| Organized sports team | 299 (53%) |

| Extra classes or formal tutoring | 257 (45%) |

| Private or group lessons (e.g., music, dance, art, karate) | 251 (44%) |

| Formal day care | 198 (35%) |

| Boy/Girl Scouts, Girls Inc., 4H, YMCA/YWCA, or PAL Center | 164 (29%) |

| Other club or organization | 121 (21%) |

| Boys and Girls Club | 85 (15%) |

| Activity with Big Brother or Big Sister | 50 (9%) |

Covariates.

Child externalizing problems (age 2), household income (age 2), maternal education (age 2), and study site were entered as covariates in multivariate analyses. At age 2, the mother’s report of broad-band Externalizing behaviors on the Child Behavior Checklist/1½- 5 (CBCL 1½−5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) was included as a covariate in the model. In addition, annual household income was reported by mothers at age 2 and was coded on a scale from .5 to 10 where .5 represented ≤ $4999 and 10 represented ≥ $90,000. A 1-point increase in annual income represented a $9999 increase. Average household income at ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5 was considered as a covariate, but was not significantly associated with average extracurricular involvement at these ages, r = .03, ns. Mothers also reported on their level of education acquired at child age 2. Maternal education was coded on a scale from 1 (no formal schooling) to 9 (graduate degree). Finally, study site was dummy coded such that Pittsburgh, PA was the reference group.

Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of study variables were computed in SPSS Version 25. Structural equation modeling was conducted in Mplus Version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2020) to assess the hypotheses in a multivariate framework. Full-information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used to estimate missing data (n = 21, 3%) (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). A latent factor for maternal Positive Behavior Support was estimated at ages 2 and 3 using the following variables at each age: maternal involvement, positive reinforcement, engaged interaction, and proactive parenting. Measurement invariance was assessed for the PBS latent factors at ages 2 and 3. Direct pathways between intervention group status (0 = control, 1 = FCU), maternal Positive Behavior Support (ages 2 and 3), and child extracurricular involvement (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5) were estimated. An indirect pathway from intervention group status to extracurricular involvement, via age 3 Positive Behavior Support, was also estimated. The significance of the indirect effect was tested using the delta method (MacKinnon, 2008). Mothers’ reports of children’s early externalizing behaviors, household income, maternal education, and study site were entered as covariates. Prior to analyses, all variables were assessed and confirmed to meet required standards for normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity. Model fit was assessed using the Chi-square ratio (χ2/df = 1 to 3), comparative fit index (CFI > .90), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .05 for good fit, RMSEA < .08 for acceptable fit) (McDonald & Ho, 2002). Satorra-Bentler Chi-square difference tests (p < .05) were used to compare model fit between the models used to test for measurement invariance (Satorra & Bentler, 2010). Correlations between Positive Behavior Support latent factors and other study variables were assessed in Mplus Version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2019).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Descriptive statistics of study variables by treatment status (i.e., FCU or control) are presented in Table 1. Characteristics of families who were randomly assigned to receive the FCU (n = 317, 50%) were compared to those who were randomly assigned to the control group (n = 313, 50%). Chi-square and independent samples t-tests revealed that there were no significant differences in maternal Positive Behavior Support (ages 2 or 3), extracurricular involvement (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), child externalizing problems (age 2), household income (age 2 or averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, and 9.5), maternal education (age 2), study site, child gender, child race, or child ethnicity between the control and intervention groups.

Bivariate correlations among study variables for the full sample are presented in Table 3. Higher mother-reported externalizing problems and lower household income and maternal education at age 2 were significantly associated with lower levels of maternal Positive Behavior Support (PBS) at ages 2 and 3. In addition, mothers in Charlottesville, VA exhibited significantly lower levels of PBS at ages 2 and 3 than mothers in Eugene, OR or Pittsburgh, PA, whereas mothers in Eugene, OR exhibited higher levels of PBS at ages 2 and 3 than mothers in the other two sites.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations of Study Variables

| Variable (Age[s]) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Behavior Support (Age 2) | -- | |||||||

| 2. Group = FCU | −.06 | |||||||

| 3. Externalizing problems (Age 2) | −.20*** | .01 | ||||||

| 4. Income (Age 2) | .13** | .02 | −.10* | |||||

| 5. Maternal education (Age 2) | .37*** | .00 | −.11** | .19*** | ||||

| 6. Site = Charlottesville, VA | −.11* | .00 | −.08 | .01 | −.15*** | |||

| 7. Site = Eugene, OR | .27*** | .00 | −.01* | .03 | .04 | −.46*** | ||

| 8. Positive Behavior Support (age 3) | .79*** | .08 | −.12 | .22*** | .35*** | −.16** | .34*** | |

| 9. Extracurricular involvement (averaged across ages 7.5, 8.5, 9.5) | .16*** | .05 | −.03 | −.06 | .26*** | .07 | −.07 | .21*** |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Contrary to study hypotheses, intervention group status was not significantly correlated with levels of maternal PBS at age 3. However, PBS was strongly correlated across ages 2 and 3. Furthermore, children in the intervention group were not involved in a significantly greater number of extracurricular activities at school-age than those in the control group. However, in line with our hypotheses, higher levels of maternal PBS at ages 2 and 3 were both associated with children’s greater school-age extracurricular involvement.

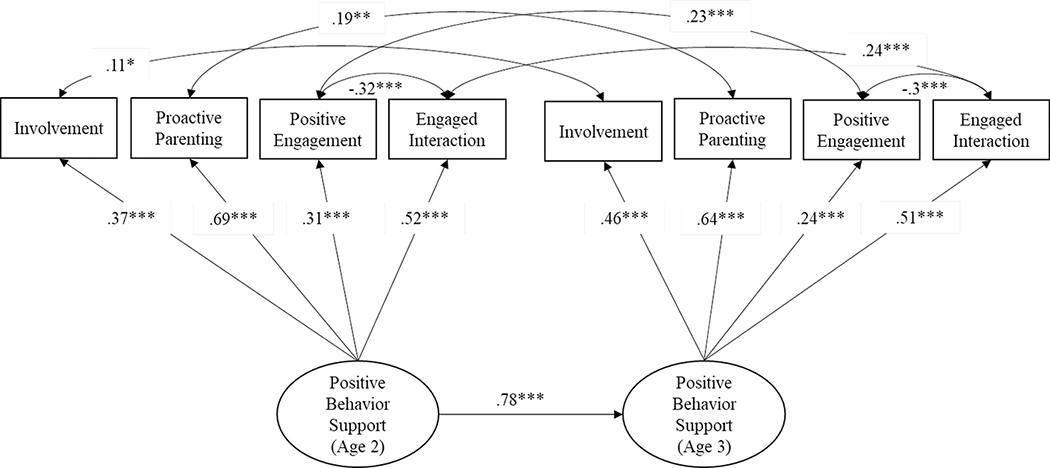

Generating Measurement Model for Positive Behavior Support

Before conducting multivariate analyses related to the study’s primary goals, as described in Dishion et al. (2008), latent factors for PBS at ages 2 and 3 were estimated. Within each latent factor, each variable was not weighted and therefore contributed equally (i.e., 25%) to the estimation of PBS at ages 2 and 3. Both factors demonstrated excellent model fit at ages 2 (χ2/df = .84; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI = .00 to .10); CFI = 1.00) and 3 (χ2/df = 1.46; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI = .00 to .12); CFI = 1.00). All factor loadings were significant and positive. Next, a measurement model was estimated to assess relations between the age 2 and 3 PBS latent factors (Figure 1). Age 2 and 3 measures were covaried within each separate variable. Furthermore, as positive engagement and engaged interaction were derived from the same coding scheme, they were correlated within ages 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Measurement model of maternal Positive Behavior Support (PBS) at ages 2 and 3. Fit statistics: χ2/df = .89; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI = .00 to .04); CFI = 1.00. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Measurement invariance was assessed to determine if PBS was measured similarly at ages 2 and 3. First, factor loadings were estimated freely for PBS at ages 2 and 3 (configural invariance). The model had adequate model fit: χ2/df = .89; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI = .00 to .04); CFI = 1.00. All factor loadings for both of the PBS latent factors were significant and each component was significantly correlated across ages 2 and 3. Thus, configural invariance was established. In addition, proactive engagement and engaged interaction were inversely related at ages 2 and 3. Finally, PBS at age 2 was significantly associated with PBS at age 3. Next, factor loadings were constrained to equality for PBS at ages 2 and 3 (metric invariance). This model demonstrated excellent fit: χ2/df = 1.02; RMSEA = .01 (90% CI = .00 to .04); CFI = 1.00. Furthermore, the model fit for the metric invariance model was not significantly different from the fit of the configural invariance model: Satorra-Bentler Δχ2 (3) = .13, p > .99. Finally, all factor loadings and intercepts were constrained to equality for PBS at ages 2 and 3 (scalar invariance). This model demonstrated adequate fit: χ2/df = 3.53; RMSEA = .06 (90% CI = .05 to .08); CFI = .92. The model fit of the scalar invariance model was not significantly different from the fit of metric invariance model: Satorra-Bentler Δχ2 (4) = .20, p > .99. Thus, scalar measurement invariance was demonstrated for PBS across ages 2 and 3.

Direct and Indirect Pathways

To test the direct pathway between intervention group and children’s school-age extracurricular activities and the indirect pathway from intervention group to extracurricular activities via changes in PBS from child ages 2 to 3, a structural model was estimated (Figure 2). Age 2 externalizing problems, age 2 household income, age 2 maternal education, and study site were included as covariates. Furthermore, the following non-significant associations were fixed to 0: intervention group with study site, age 2 household income, and age 2 externalizing problems; and study site with age 2 household income and age 2 externalizing problems. The model demonstrated excellent model fit: χ2/df = 1.09; RMSEA = .01 (90% CI = .00 to .03); CFI = .99. As reported previously (Dishion et al., 2008), mothers in the intervention group exhibited larger increases in PBS from ages 2 to 3 than mothers in the control group. Furthermore, as hypothesized, maternal PBS at age 3 was significantly associated with higher school-age extracurricular involvement. As reported earlier, there was not a direct effect of intervention group status on extracurricular activities. However, a significant indirect pathway was evident, such that mothers in the intervention group exhibited higher levels of PBS at age 3 which, in turn, was associated with higher levels of children’s school-age extracurricular involvement, β = .03, SE = .01, p = .04.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal relations between intervention group status, maternal Positive Behavior Support (PBS) at ages 2 and 3, and children’s average school-age extracurricular involvement. Covariates included child externalizing problems (age 2), household income (age 2), maternal education (age 2), and study site (Pittsburgh, PA as reference group). All estimated pathways are displayed. The significant indirect pathway is in bold and red. Standardized beta values are reported. Fit statistics: χ2/df = 1.09; RMSEA = .01 (90% CI = .00 to .03); CFI = .99. ns indicates p ≥ .05. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Discussion

It is important to identify early childhood factors that may be leveraged to promote school-age involvement in extracurricular activities, as involvement in extracurricular activities has the potential for a wide array of benefits, especially for low-income youth (Posner & Vandell, 1999). One important precursor is positive parenting, including caregiving characterized by both being responsive and proactive in supporting children’s needs. Positive parenting, operationalized as Positive Behavior Support (PBS) in the current study through nearly an hour of observations of mother-child interaction, has previously been found to improve in response to a brief intervention for low-income families, the Family Check-Up (FCU). In several previous studies using the current sample, intervention effects of the FCU on multiple child outcomes at preschool and school-age have been mediated by improvements in PBS (e.g., Brennan et al., 2013; Dishion et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2015). Following in the footsteps of prior work on the FCU, the current study aimed to test longitudinal relations between random assignment to the FCU and children’s school-age extracurricular involvement, and whether such associations might be mediated by improvements in maternal PBS between child ages 2 and 3. First, as reported previously (Dishion et al., 2008), random assignment to the FCU was associated with improvements in maternal PBS. Second, as hypothesized, we found support for direct associations between maternal PBS in the preschool years and higher levels of children’s school-age extracurricular involvement. Finally, although FCU group status was not directly associated with children’s extracurricular involvement, a significant indirect path was found from FCU group status to higher levels of children’s school-age extracurricular involvement via improvements in toddler-age maternal PBS. The indirect path was significant in the context of multiple important covariates, including maternal education and family income. Furthermore, enrolling the target child in extracurricular activities was not a primary focus in early childhood but was increasingly emphasized starting at age 7.5.

Indirect Effect of FCU on Extracurricular Involvement via Improvements in PBS

Support was found for indirect, but not direct, associations between the FCU and children’s level of engagement in extracurricular activities at school age, via toddler-age maternal PBS. As noted above, the lack of direct relations between the FCU and extracurricular activity engagement is consistent with several previous child outcomes using the FCU in the current sample, including indirect effects via maternal PBS on children’s conduct problems, language development, inhibitory control, and emotion regulation during the preschool period (Dishion et al., 2008; Lunkenheimer et al., 2008; Shelleby et al., 2012), and children’s academic achievement, body mass index, and peer acceptance at school-age (Brennan et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2015). Thus, we expected the FCU to be associated with higher levels of children’s school-age extracurricular involvement via improvements in maternal PBS, rather than a direct impact. Furthermore, to our knowledge the current study is the first of its kind to assess associations between an early family intervention and school-age extracurricular involvement via maternal PBS.

It is important to note that the lack of direct relations between the FCU and extracurricular involvement was not consistent with Leijten et al.’s (2015) finding that caregivers randomly assigned to the FCU at child age 2 were more likely to seek services (e.g., counseling, religious groups) for their child in the early school-age years (i.e., direct effect). Exploratory analyses revealed that random assignment to the FCU was not directly associated with children’s school-age extracurricular involvement, even when maternal PBS at age 3 was removed from the model. However, because of the nature of the services included in Leijten et al. (2015) compared to extracurricular activity involvement, it is likely that different mechanisms link the FCU with service usage versus extracurricular activity engagement. Namely, improving parent’s PBS may lead to higher levels of interpersonal sensitivity, such as the ability to both identify and negotiate opportunities for after-school socialization and non-academic skill development (i.e., in the context of parental employment in the afternoon and/or challenges in providing transportation). Conversely, PBS may be less important for meeting children’s more basic needs and identifying appropriate resources, such as when a child is ill or exhibiting severe behavior problems. In these circumstances, a broader understanding of available resources for meeting children’s more visibly obvious needs may be required, which may be provided by the FCU regardless of level of maternal PBS. It is important to note that only direct relations were assessed in Leijten et al. (2015), and thus it is unknown if maternal PBS or other maternal caregiving factors underlie the direct associations between the FCU and school-age service usage.

Limitations and Future Directions

Strengths of the current study include the use of a randomized, controlled design for a large sample of at-risk, diverse families of low-income backgrounds followed longitudinally from early childhood into the school-age years after accounting for family income, maternal education, and early child conduct problems. The present study contributes to the broader literature documenting associations between supportive maternal caregiving and a broad range of positive outcomes in childhood. However, future studies should assess how specific dimensions of parenting that might be more theoretically linked to extracurricular activity engagement, such as maternal involvement and monitoring during the toddler period, relate to children’s school-age extracurricular involvement. Furthermore, we assessed the collateral impact of the FCU based on random assignment (i.e., intention-to-treat), rather than by level of engagement in the FCU. Thus, the present findings are likely a conservative estimate of effects. However, it remains unknown what dose of the FCU may be associated with higher levels of children’s extracurricular involvement via improvements in maternal PBS. However, the study also had several limitations. The first of these is the measurement of extracurricular activity engagement. Namely, children were involved in a wide variety of activities (e.g., after school care, sports teams, lessons, and tutoring), typically engaging in multiple activities throughout the week. However, because of the nature of our measure (i.e., a summation representing the breadth of activities endorsed by a primary caregiver), we were unable to assess the collateral impact of the FCU on engagement in different types of extracurricular activities. Similarly, we did not measure the nature of the extracurricular activities more broadly, such as who initiated the child’s involvement in the activity, what the reasons were for involvement, and how much time the child spent in each activity. By including more detailed assessments of children’s extracurricular activity involvement, future studies may be able to determine how brief interventions, such as the FCU, may encourage caregivers to enroll their children in extracurricular activities based on their perceptions of their children’s needs, including after-school supervision, skill-building, and socialization. In addition, the present study did not assess outcomes in adolescence (e.g., externalizing problems, substance use), thus preventing us from drawing conclusions about potential positive developmental outcomes in adolescence associated with the improvements in maternal PBS from the FCU and subsequent increased school-age extracurricular involvement. The lack of adolescent outcomes in the present study represents an important direction for future research on positive developmental cascades spanning from early childhood into adolescence.

Other limitations concern the sample and data collection. As children and families were screened for high levels of psychosocial risk, findings of this study may not generalize to children and families from higher socioeconomic status backgrounds or similarly low-income backgrounds, with lower levels of early childhood risk factors. Also, the majority of children in the present study were White or Black/African American and not Hispanic/Latinx, which raises concerns about generalizability to children from other racial and ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, the children in this sample are now approaching early adulthood and it is unclear in the rapidly changing context of American society whether these findings would be sustained if the study were initiated today. Thus, it is important for findings to be replicated in current samples of children with varying levels of familial and individual risk factors. Finally, we did not control for family structure variables (e.g., single parent, number of siblings) which may also impact family resources and maternal time and energy that can be allocated to supporting children’s extracurricular activities. Future studies on promoting youth extracurricular involvement would benefit from including such variables.

Despite these limitations, the current study provides support for a collateral, indirect association between the FCU and children’s school-age extracurricular involvement, via improvements in maternal PBS. If replicated, this finding has important implications for broadening the scope of positive outcomes supported by parenting interventions for low-income families, suggesting that it is possible to promote school-age extracurricular involvement as early as toddlerhood by improving early maternal supportiveness and responsiveness. As promoting extracurricular involvement was not the primary goal of the Early Steps Multisite study (Dishion et al., 2008), future work should take a more tailored approach using the results of the current study in conjunction with early childhood caregiving interventions (e.g., the FCU, the Incredible Years (Webster-Stratton, 2011), or PCIT (Sheila Eyberg, 1988)) to specifically target youth extracurricular involvement via improvements in maternal supportive caregiving. Furthermore, it is important for future studies to include measures of positive youth outcomes that have been proposed to relate to extracurricular involvement, including identity development, friendships, and relationships with mentors. Specifically, it is possible that the present findings represent a positive cascade that starts with positive experiences with caregivers in early childhood, leading to engagement in extracurricular activities at school-age, and resulting in positive developmental outcomes in adolescence. Finally, the present findings may also have important benefits for caregivers (e.g., increased parenting efficacy, increased time for work or school) which may, in turn, give caregivers the time, opportunity, and motivation to seek out additional resources that may further benefit their families.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by grant to authors Shaw and Wilson from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) under Grant DA016110. We also would like to extend our thanks to staff of the Early Steps Multisite Study and the families who have participated in the project over the past two decades.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JSF, upon reasonable request.

References

- Abraczinskas M, Kilmer R, Haber M, Cook J, & Zarrett N (2016). Effects of extracurricular participation on the internalizing problems and intrapersonal strengths of youth in a system of care. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(3–4), 308–319. 10.1002/ajcp.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Funk JB, Elliott R, & Smith PH (2003). Parental support and pressure and children’s extracurricular activities: Relationships with amount of involvement and affective experience of participation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24(2), 241–257. 10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00046-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aumètre F, & Poulin F (2018). Academic and behavioral outcomes associated with organized activity participation trajectories during childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 54, 33–41. 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan LM, Shelleby EC, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Dishion TJ, & Wilson M (2013). Indirect effects of the family check-up on school-age academic achievement through improvements in parenting in early childhood. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 762–773. 10.1037/a0032096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell BM, & Bradley RH (1984). Home observation for measurement of the environment. University of Arkansas at Little Rock. [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, & Wilson MN (2015). proactive parenting and children’s effortful control: mediating role of language and indirect intervention effects: Parenting, language, and effortful control. Social Development, 24(1), 206–223. 10.1111/sode.12069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Shaw D, Wilson M, Danzo S, Weaver-Krug C, Lemery-Chalfant K, & Dishion TJ (2019). Indirect effects of the early childhood Family Check-Up on adolescent suicide risk: The mediating role of inhibitory control. Development and Psychopathology, 1–10. 10.1017/S0954579419000877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denault A-S, & Déry M (2015). Participation in organized activities and conduct problems in elementary school: The mediating effect of social skills. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 23(3), 167–179. 10.1177/1063426614543950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Brennan LM, Shaw DS, McEachern AD, Wilson MN, & Jo B (2014). Prevention of problem behavior through annual family check-ups in early childhood: intervention effects from home to early elementary school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(3), 343–354. 10.1007/s10802-013-9768-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Bullock BM, & Granic I (2002). Pragmatism in modeling peer influence: dynamics, outcomes, and change processes. Development and Psychopathology, 14(04), 969–981. 10.1017/S0954579402004169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Hogansen J, Winter C, & Jabson JM (2004). The coder impressions inventory [Unpublished coding manual].

- Dishion TJ, & Kavanagh K (2003). Intervening in adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, & Kavanagh K (2003). The family check-up with high-risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring. Behavior Therapy, 34(4), 553–571. 10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80035-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, & Wilson M (2008). The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development, 79(5), 1395–1414. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Stormshak EA (2007). Intervening in children’s lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Ziol-Guest KM, & Kalil A (2010). Early-childhood poverty and adult attainment, behavior, and health. Child Development, 81(1), 306–325. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C, & Bandalos D (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(3), 430–457. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg S, & Pincus D (1999). Eyberg child behavior inventory & Sutter-Eyberg student behavior inventory-revised: Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg Sheila. (1988). Parent-child interaction therapy: Integration of traditional and behavioral concerns. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 10(1), 33–46. 10.1300/J019v10n01_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot BI, & Kavanagh K (1993). Parenting during the second year: Effects of children’s age, sex, and attachment classification. Child Development, 64(1), 258–271. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AF, & Matjasko JL (2005). The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development: A comprehensive review and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 75(2), 159–210. 10.3102/00346543075002159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern R (1999). After-school programs for low-income children: Promise and challenges. The Future of Children, 9(2), 81. 10.2307/1602708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway SL, & Pimlott-Wilson H (2014). Enriching children, institutionalizing childhood? Geographies of play, extracurricular activities, and parenting in England. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104(3), 613–627. 10.1080/00045608.2013.846167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jabson JM, Dishion TJ, Gardner F, & Burton J (2004). Relationship Process Code v-2.0. Training manual: A system for coding relationship interactions [Unpublished coding manual].

- Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR, & Guttentag C (2008). A responsive parenting intervention: The optimal timing across early childhood for impacting maternal behaviors and child outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1335–1353. 10.1037/a0013030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leijten P, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Wilson MN, Matthys W, & Dishion TJ (2015). The Family Check-Up and service use in high-risk families of young children: a prevention strategy with a bridge to community-based treatment. Prevention Science, 16(3), 397–406. 10.1007/s11121-014-0479-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long P, Forehand R, Wierson M, & Morgan A (1994). Does parent training with young noncompliant children have long-term effects? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32(1), 101–107. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90088-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell AM, Gardner F, Wilson MN, & Skuban EM (2008). Collateral benefits of the Family Check-Up on early childhood school readiness: Indirect effects of parents’ positive behavior support. Developmental Psychology, 44(6), 1737–1752. 10.1037/a0013858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP (2008). Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Masarik AS, & Conger RD (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the Family Stress Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 85–90. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, & Ho M-HR (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64–82. 10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn AL, Cates CB, Weisleder A, Berkule Johnson S, Seery AM, Canfield CF, Huberman HS, & Dreyer BP (2018). Reading aloud, play, and social-emotional development. Pediatrics, 141(5), e20173393. 10.1542/peds.2017-3393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metsäpelto R-L, & Pulkkinen L (2012). Socioemotional behavior and school achievement in relation to extracurricular activity participation in middle childhood. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(2), 167–182. 10.1080/00313831.2011.581681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, & Chen E (2013). The biological residue of childhood poverty. Child Development Perspectives, 7(2), 67–73. 10.1111/cdep.12021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2020).. Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neely SR, & Vaquera E (2017). Making it count: Breadth and intensity of extracurricular engagement and high school dropout. Sociological Perspectives, 60(6), 1039–1062. 10.1177/0731121417700114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oberle E, Ji XR, Guhn M, Schonert-Reichl KA, & Gadermann AM (2019). Benefits of extracurricular participation in early adolescence: Associations with peer belonging and mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(11), 2255–2270. 10.1007/s10964-019-01110-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberle E, Ji XR, Magee C, Guhn M, Schonert-Reichl KA, & Gadermann AM (2019). Extracurricular activity profiles and wellbeing in middle childhood: A population-level study. PLOS ONE, 14(7), e0218488. 10.1371/journal.pone.0218488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner JK, & Vandell DL (1999). After-school activities and the development of low-income urban children: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 868–879. 10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph KA, Fraser MW, & Orthner DK (2004). Educational resilience among youth at risk. Substance Use & Misuse, 39(5), 747–767. 10.1081/JA-120034014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis SM, & Díaz E (1999). Economically disadvantaged urban female students who achieve in schools. The Urban Review, 31(1), 31–54. 10.1023/A:1023244315236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, & Vandell DL (1996). Quality of care at school-aged child-care programs: Regulatable features, observed experiences, child perspectives, and parent perspectives. Child Development, 67(5), 2434–2445. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01866.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Chen X, Bowker JC, McDonald KL, & Heverly-Fitt S (2015). Peer relationships. In Bornstein MH & Lamb ME (Eds.), Developmental Science: An Advanced Textbook (7th ed., pp. 587–644). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, Bor W, & Morawska A (2007). Maintenance of treatment gains: A comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(6), 983–998. 10.1007/s10802-007-9148-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Schoenfelder EN, Wolchik SA, & MacKinnon DP (2011). Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 299–329. 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, & Bentler PM (2010). Ensuring positiveness of the scaled difference chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika, 75(2), 243–248. PubMed. 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JK, Nelson JA, & Dix T (2018). Interdependence among mothers, fathers, and children from early to middle childhood: Parents’ sensitivity and children’s externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 54(8), 1528–1541. 10.1037/dev0000525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, & Arnds K (2006). Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-year effects of the Family Check-Up in early childhood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 1–9. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Galán CA, Lemery-Chalfant K, Dishion TJ, Elam KK, Wilson MN, & Gardner F (2019). Trajectories and predictors of children’s early-starting conduct problems: Child, family, genetic, and intervention effects. Development and Psychopathology, 1(5), 1911–1921. 10.1017/S0954579419000828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, & Gross HE (2008). What we have learned about early childhood and the development of delinquency. In Liberman AM (Ed.), The Long View of Crime: A Synthesis of Longitudinal Research (pp. 79–127). Springer; New York. 10.1007/978-0-387-71165-2_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Sitnick SL, Brennan LM, Choe DE, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, & Gardner F (2016). The long-term effectiveness of the Family Check-Up on school-age conduct problems: Moderation by neighborhood deprivation. Development and Psychopathology, 28(4pt2), 1471–1486. 10.1017/S0954579415001212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelleby EC, Shaw DS, Cheong J, Chang H, Gardner F, Dishion TJ, & Wilson MN (2012). Behavioral Control in at-risk toddlers: The Influence of the Family Check-up. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41(3), 288–301. 10.1080/15374416.2012.664814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Montaño Z, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, & Wilson MN (2015). Preventing weight gain and obesity: Indirect effects of the Family Check-Up in early childhood. Prevention Science, 16(3), 408–419. 10.1007/s11121-014-0505-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Connell A, & Dishion TJ (2009). An adaptive approach to family-centered intervention in schools: Linking intervention engagement to academic outcomes in middle and high school. Prevention Science, 10(3), 221–235. 10.1007/s11121-009-0131-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandell DL, Lee KTH, Whitaker AA, & Pierce KM (2018). Cumulative and differential effects of early child care and middle childhood out-of-school time on adolescent functioning. Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.13136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Dishion T, Sitnick SL, Shaw DS, Winter CE, & Wilson M (2015). Early parental positive behavior support and childhood adjustment: Addressing enduring questions with new methods. Social Development, 24(2), 304–322. 10.1111/sode.12103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C (2011). The Incredible Years: Parents, teachers, and children’s training series. Incredible Years. [Google Scholar]

- Weininger EB, Lareau A, & Conley D (2015). What money doesn’t buy: Class resources and children’s participation in organized extracurricular activities. Social Forces, 94(2), 479–503. 10.1093/sf/sov071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weisleder A, Cates CB, Dreyer BP, Berkule Johnson S, Huberman HS, Seery AM, Canfield CF, & Mendelsohn AL (2016). Promotion of positive parenting and prevention of socioemotional disparities. Pediatrics, 137(2), e20153239–e20153239. 10.1542/peds.2015-3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, JSF, upon reasonable request.