Abstract

Background

The importance of specific serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) differs by age. Data on pneumococcal carriage in different age groups, along with data on serotype-specific invasiveness, could help explain these age-related patterns and their implications for vaccination.

Methods

Using pneumococcal carriage and disease data from Israel, we evaluated the association between serotype-specific IPD in adults and serotype-specific carriage prevalence among children in different age categories, while adjusting for serotype-specific invasiveness. We estimated carriage prevalence using different age groupings that were selected a priori. The Deviance Information Criterion was used to determine which age groupings of carriage data best fit the adult IPD data. Serotype-specific disease patterns were further evaluated by stratifying IPD data by comorbidity status.

Results

The relative frequency of serotypes causing IPD differed between adults and children, and also differed between older and younger adults and between adults with and without comorbidities. Serotypes overrepresented as causes of IPD in adults were more commonly carried in older children compared with younger children. In line with this, the serotype-specific frequency of carriage in older children, rather than infants, best correlated with serotype-specific IPD in adults.

Conclusions

These analyses demonstrate that the serotype patterns in carriage in older children, rather than infants, are best correlated with disease patterns in adults. This might suggest these older children are more influential for disease patterns in adults. These insights could help in optimizing vaccination strategies to reduce disease burden across all ages.

Keywords: pneumococcus, invasive pneumococcal disease, disease prediction, elderly, comorbidity

Serotype-specific rates of invasive pneumococcal disease in adults are better correlated with serotype-specific carriage patterns in older children than those in infants.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is a frequent colonizer of the upper respiratory tract of healthy children and is also a major cause of disease globally. The burden of pneumococcal disease disproportionally affects infants and the elderly and those with certain underlying comorbidities [1]. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) provide protection against 10 or 13 of the 90 or more immunologically distinct polysaccharide capsular types (serotypes), preventing disease and reducing colonization of the nasopharynx in vaccinated individuals. Since children who carry pneumococcus are the main source of exposure for adults [2–4], vaccinating children with PCVs has also resulted in the near elimination of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) caused by vaccine-targeted serotypes (VTs) among adults [5].

Even before the introduction of PCVs, there were important differences in the distribution of serotypes causing IPD between children and adults [6]. For instance, VTs caused a larger fraction of IPD in children. After introduction of PCVs, nonvaccine serotypes (NVTs) have increased in frequency among colonized children. This “serotype replacement” [7] has had a modest effect on IPD rates in children but has substantially reduced the indirect benefits for adults that result from vaccinating infants. Older adults and those with certain underlying diseases have proven particularly susceptible to disease caused by emerging NVTs [8–10]. In some countries, the increase in the incidence of NVTs in adults has offset declines in the incidence of VTs [11].

Variations in vaccine approach and schedule could have important implications for preventing IPD in adults. Currently, the number and timing of doses used in children differ between countries, as does the use of a booster dose. For instance, the United Kingdom recently decided to move to a reduced-dose schedule of PCVs in infants, where children receive a single priming dose and a single booster dose [12]. For such a strategy to be effective in maintaining indirect protection of unvaccinated individuals, it is important that vaccine-derived protection is maintained among the children responsible for transmission in the population. Thus, identifying those age groups driving transmission is critical. Moreover, these issues are increasingly important as new 15- and 20-valent conjugate vaccines move towards licensure.

It is generally assumed that most exposure to pneumococcus in adults results from contact with children [13]. However, children are not all equally likely to carry and transmit pneumococcus, and some groups of children (eg, preschoolers) might be more influential due to different contact patterns and intensity of carriage [13–16]. Recent work suggests that older children, rather than infants, transmit pneumococcus to adults [13–16].

In this study, we sought to understand the relationship between serotype-specific carriage patterns in different age groups of children and the distribution of serotypes causing IPD in different adult age and risk groups. These analyses could help in optimizing vaccine strategies to reduce pneumococcal disease across all age groups.

METHODS

Data Sources

PCV7 was introduced in Israel in July 2009 using a 2 + 1 schedule with a catch-up campaign for children younger than 24 months of age. PCV7 was replaced in the schedule by PCV13 starting in November 2010 (without a catch-up). Details of the carriage and IPD data used in this study have been previously described [14, 17, 18]. Briefly, the carriage data were collected from children visiting the emergency department (ED) at Soroka University Medical Center, the only ED in southern Israel. The first 4 Jewish and first 4 Bedouin children younger than 5 years of age visiting the ED each day for any complaint were enrolled in the study to obtain a nasopharyngeal swab. The IPD data were obtained from a nationwide surveillance system [17, 19].

Carriage and disease data were divided into 4 equal time periods (early-PCV7: November 2009 to July 2011; early PCV13: August 2011 to February 2013; late-PCV13: March 2013 to October 2014; stable-post-PCV period: November 2014 to June 2016). The IPD data from 4304 individuals were stratified by age group and according to comorbidity status (no risk, at risk, or high risk of pneumococcal disease [19]) based on recommendations for receipt of PPV23. Risk-group analyses were conducted on individuals aged 18 years and older who had information on comorbidity status, serotype, and sample collection date. The stable-post-PCV period, for the subset of data with comorbidities, ended December 2015 (as compared with June 2016 for the full dataset).

The carriage data were stratified by both ethnicity (Jewish vs Bedouin) and according to the presence or absence of recorded complaints that could be caused by pneumococcus (bacteremia, conjunctivitis, influenza, lower respiratory infection, meningitis, otitis media, pneumonia, sepsis, upper respiratory infection) to confirm results were not sensitive to these factors.

Because the IPD data were predominantly from the Jewish population, we focused on the carriage and IPD data from Jewish children for the main analyses.

Modeling the Relationship Between Carriage in Children and Invasive Disease in Adults

The goal for these analyses was (1) to evaluate variations in serotype-specific IPD incidence by age and (2) to determine whether carriage data from specific age groups better correlated with IPD incidence among adults. To do this, we used a previously described Poisson regression model [20], which is described in detail in the Supplementary Material. For serotype i, and time period k,

This can be rearranged as

The outcome variable was the number of IPD cases caused by each serotype in the relevant age group and time period. The covariates in this model were the serotype-specific carriage prevalence in the corresponding time period in Jewish children younger than 5 years of age (log-transformed) and the serotype-specific invasiveness for children (log-transformed). The serotype-specific invasiveness estimate was calculated from the data across all study periods (see Supplementary Figure 1), supported by previous studies indicating that invasiveness is stable over space and time [21]. In addition, a serotype-specific random intercept was included to account for unexplained serotype-specific variations in IPD rates. This serotype-level random intercept can be interpreted as a log(rate ratio), which indicates how much more or less disease was caused by that serotype in adults based on the carriage prevalence in children and invasiveness patterns in children. Φ ik is an observation-level random intercept that captures overdispersion in the data. Analyses were stratified by age or by comorbidity status. To account for uncertainty in the predictors (serotype-specific carriage and invasiveness when sparse serotype-specific data iareavailable), we fit this model within a Bayesian framework. Further details on the model structure and the priors are reported in Weinberger et al [20] and described in the Supplementary Material. The models were fit using JAGS v4.2.0 [22] in RStudio v1.0.143 [23], using R v3.5.1 (https://www.r-project.org/).

Stratification of Carriage in Children by Age Group to Better Explain Adult Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Patterns

The goal for this analysis was to determine whether serotype-specific carriage prevalence in any particular age group better explained patterns of IPD observed in adults and in different risk groups. To accomplish this, the carriage data from Jewish children were further stratified by age category (≤12 months, <18 months, <24 months, <36 months, <48 months, 13–59 months, 18–59 months, 24–59 months, 36–59 months, and 48–59 months) (Table 1). The models of IPD described above were re-fit using these subsets of carriage prevalence data. The Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) was computed for each model [24]. This Bayesian model comparison metric accounts for the fit of the model to the data while penalizing more complex models. A lower DIC value for a model among a group of competitors indicates that it has an improved balance between model fit and complexity, with a difference of 10 points considered to be a notable improvement. As a simple descriptive analysis, we evaluated the Spearman’s correlation between serotype-specific IPD in different age groups and serotype-specific carriage in different groups of carriage (multiplied by invasiveness). This analysis was stratified by time period and by PCV13 and non-PCV13 serotypes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Pneumococcal Carriage Data Used in the Model

| Total Number of Swabs Collected | Number of Swabs Positive for Pneumococcus (%) | |

| Jewish children | 4454 | 1898 (43) |

| <12 months | 1862 | 717 (39) |

| <18 months | 2491 | 1006 (44) |

| <24 months | 3082 | 1295 (43) |

| <36 months | 3757 | 1611 (43) |

| <48 months | 4208 | 1799 (43) |

| 13–59 months | 2593 | 1181 (46) |

| 18–59 months | 1964 | 892 (45) |

| 24–59 months | 1373 | 603 (44) |

| 36–59 months | 698 | 287 (41) |

| 48–59 months | 247 | 99 (40) |

| Respiratory complaint | 4275 | 2192 (51) |

| Without respiratory complaint | 6108 | 2761 (45) |

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Data

Nasopharyngeal swabs from 10 383 individuals younger than 5 years of age were collected between November 2009 and June 2016. Of these, 48% tested positive for pneumococcal carriage. Prevalence was higher among those presenting with a complaint that could potentially have been caused by pneumococcus (eg, otitis media, pneumonia) (Table 1). Carriage prevalence increased through the first year of life, then stabilized, and declining slightly after 48 months of age. More swabs were collected from younger than older children (see Supplementary Figure 2). The serotype distribution (see Supplementary Figure 3) was broadly similar in pneumococcal-positive swabs obtained from children with respiratory complaints and those obtained from children without respiratory complaints (see Supplementary Figure 4). As a comparison, we also looked at carriage patterns in Bedouin children, who have higher carriage prevalence overall, with some notable differences in the age distribution and serotype distribution compared with the Jewish children (see Supplementary Figures 5 and 6).

There were 4303 cases of IPD: 1180 cases in children under 5 years of age and 3123 cases in individuals older than 5 years of age (5–17 years, n = 299; 18–39 years, n = 407; 40–64 years, n = 943; 65–79 years, n = 816; >80 years, n = 658). (See Supplementary Figure 7 for serotype distribution.)

Of those aged 18 years and older, 2347 individuals had recorded data on comorbidity status (no risk, at risk, or high risk of pneumococcal disease [19]) based on recommendations for receipt of PPV23.

Variations in Serotype-specific Disease Patterns by Age and Comorbidity Group

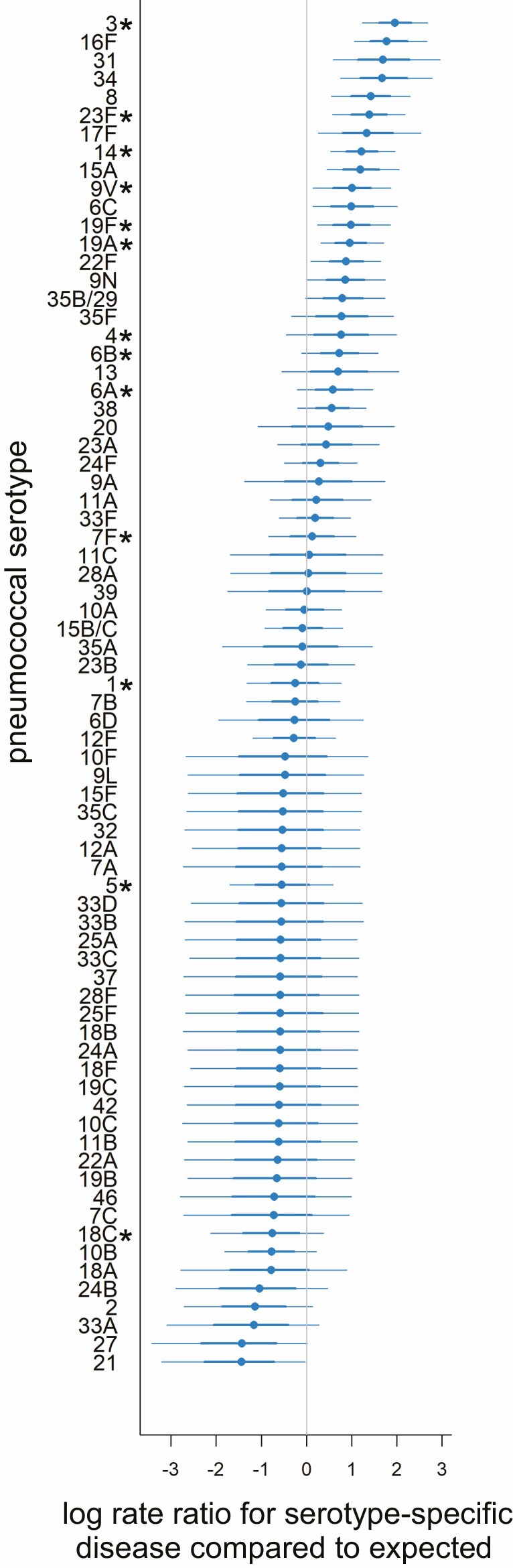

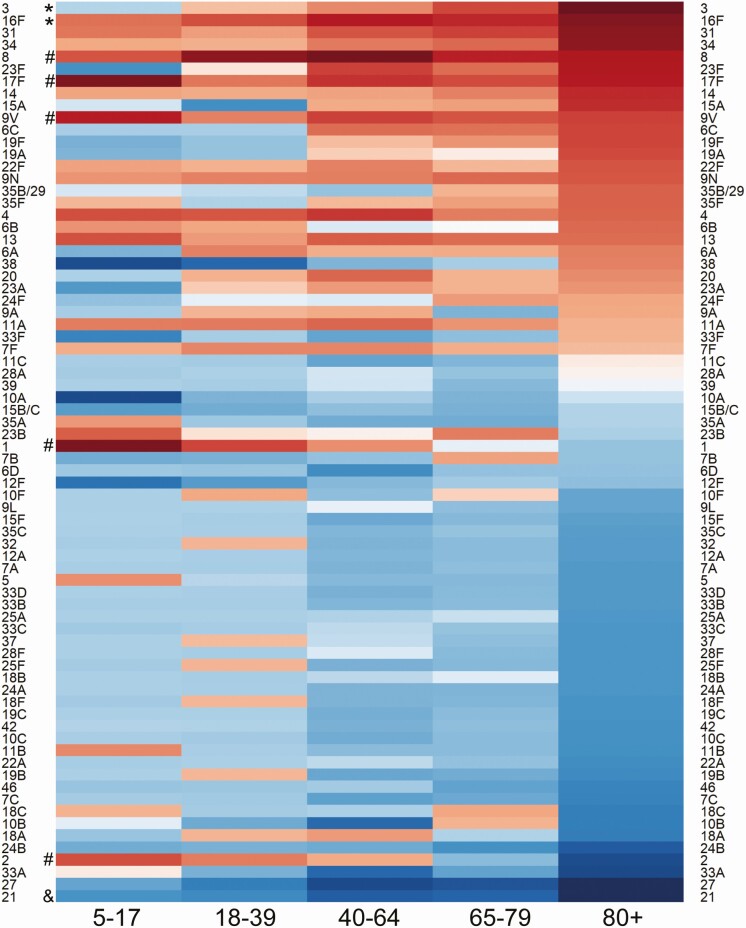

For most serotypes, the observed IPD incidence in adults was similar to what would be expected based on the carriage prevalence and invasiveness estimates from children younger than 5 years of age (random intercept close to zero) (Figure 1, results for adults aged 80 years and older; see Supplementary Figure 8, results for all age groups). Some serotypes, however, caused more disease in certain age groups compared with what would be expected based on carriage patterns in children (random intercepts above zero). This was notable for serotype 1, which was most overrepresented among 5- to 17-year-olds (with similar patterns observed for serotypes 2 and 17F), and serotype 8, which was most represented among 18- to 39-year-olds (Figure 2). Both serotypes demonstrated declining gradients with older age, where the number of IPD cases in older age groups was closer to the expected level. In contrast, serotypes 3, 6C, 15A, and 31 were overrepresented as causes of IPD more among older adults than among younger adults. Conversely, serotypes 21 and 27 were underrepresented as causes of disease in all adults older than 40 years of age.

Figure 1.

Serotypes causing IPD in adults over 80 years of age. Each point denotes a serotype-specific random intercept (x-axis) from a model fit to IPD data from adults aged ≥80 years old in Israel, with the serotype indicated on the y-axis. Values above zero indicate that the serotype is overrepresented as a cause of IPD in this age group based on how frequently they are carried in Jewish children younger than 5 years of age and their invasiveness in children younger than 5 years. Values below zero indicate the serotype is underrepresented in IPD. For each serotype, the 95% (thinner line) and 68% (thicker line) credible intervals are shown. PCV13 vaccine serotypes are denoted by an asterisk (*). Abbreviations: IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; PCV13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Figure 2.

Serotypes causing IPD in different age groups. Heatmap constructed to visualize the serotype-specific random intercepts from a model fit to IPD data from individuals aged ≥5 years in Israel. Darker red represents serotypes in that age strata overrepresented as causes of IPD based on how frequently they are carried in children younger than 5 years of age and their invasiveness in children younger than 5 years. Darker blue indicates serotypes underrepresented as causes of IPD in that age group. Symbols on the left highlight age-related patterns for certain serotypes. Those denoted by “*” become increasingly overrepresented with increasing host age, those denoted by “&” became increasingly underrepresented with increasing host age, and serotypes denoted by “#” are more overrepresented in younger individuals. Abbreviation: IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease.

Similar patterns were seen when stratifying by comorbidity status (see Supplementary Figures 9 and 10). For instance, serotypes 3 and 8 were overrepresented in adults with and without comorbidities, but the effect was more dramatic in those with comorbid conditions. Likewise, serotype 8 was most notable among those without comorbid conditions. We also considered whether the age or comorbidity patterns were confounding each other. Even after stratifying by comorbidity and by age, some serotypes, and particularly serotype 3, were still overrepresented among older adults (see Supplementary Figure 11).

Serotype Prevalence in Carriage Differs Between Younger and Older Children

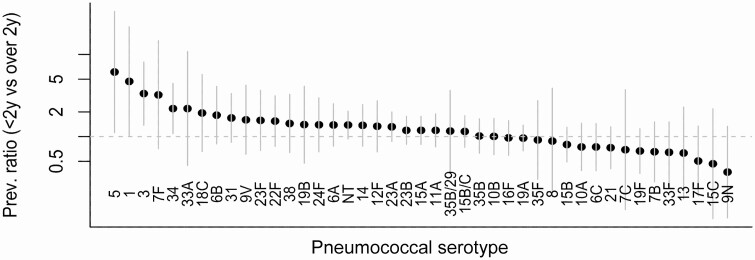

We next compared the prevalence of serotypes colonizing children younger than 24 months of age versus those carried by children 24–59 months of age (Figure 3). Serotypes 5, 1, 7F, 3, 27, 33A, 6D, 35A, 23F, 14, 34, 18C, 22F, 12A, 24A, 37, 4, 20, 31, and 19A were all at least 50% more prevalent in children 24–59 months of age than in those younger than 24 months of age. In contrast, serotypes 6A, 10A, 13, 19F, and 21 were at least 25% less prevalent in the children aged 24–35 months. We compared our findings with data from carriage studies conducted in Massachusetts (United States) [25], South Africa [26], Iceland [26], The Gambia [26], and Central Israel [27] and observed a similar distribution (see Supplementary Figure 12).

Figure 3.

Ratio of serotype-specific carriage prevalence in children aged 24–59 months compared with children aged under 24 months. Confidence intervals are shown in gray. Abbreviations: Prev., prevalence; y, years.

Comparing the serotypes that were more prevalent in carriage in older versus younger children with the serotypes that were overrepresented as causes of IPD in adults, several serotypes at the extremes stand out (Supplementary Figure 13). In particular, serotype 1 was carried more in the older children than in the younger children and was also among the most overrepresented serotypes causing IPD among the 5- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 39-year-old adults. Likewise, serotype 3 was more common in carriage among older children and was overrepresented as a cause of disease among adults 40 years of age and older.

Serotype-specific Patterns of Carriage in Older Children Best Correlate With Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in Adults

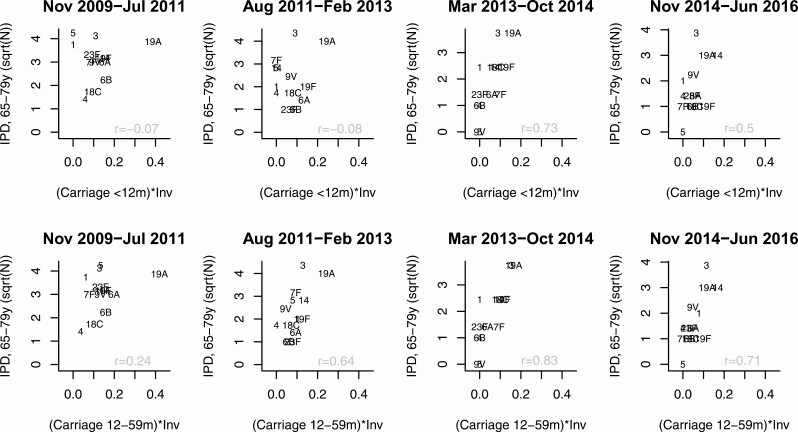

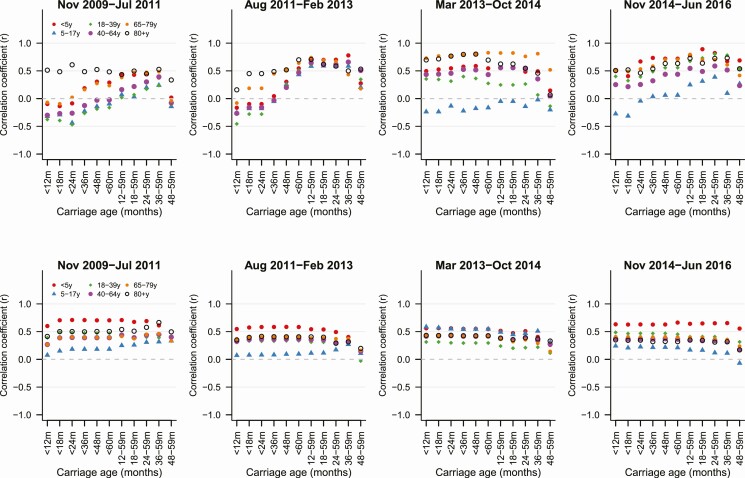

We considered whether IPD in adults better correlated with carriage prevalence in certain groups of children, after adjusting for invasiveness. We first evaluated simple correlations for VTs and NVTs. For PCV13 serotypes, there were clear differences in the strength of the correlations depending on which ages were included in the carriage variable. In the first 2 time periods (early-post-PCV7 and early-post-PCV13), the correlation was generally weakest when the carriage variable included data from children younger than 12 months old (Figures 4 and 5). In the last 2 time periods, once the prevalence of PCV13 serotypes had stabilized, the correlation was similar regardless of whether the carriage variable included data from children younger than 12 months. For non-PCV13 serotypes, the correlations were similar regardless of which age bins were included in the carriage variable, and this did not change over time (Figure 5, bottom panels).

Figure 4.

Serotype-specific IPD cases for the PCV13 serotypes among 65- to 79-year-old adults compared with carriage prevalence in children younger than 12 months old (multiplied by invasiveness) or 12- to 59-month-old children (multiplied by invasiveness). Abbreviations: Aug, August; Feb, February; Inv, invasiveness; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; Jul, July; Jun, June; m, months; Nov, November; Oct, October; PCV13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; sqrt, square root; y, years.

Figure 5.

Correlation coefficient between IPD in different age groups and carriage prevalence (multiplied by invasiveness) in different age categories. The top panels show PCV13 serotypes; the bottom panels show non-PCV13 serotypes. Each column shows a different postvaccine time period. Each color/shape represents a different age group for IPD, as indicated in the legend. Abbreviations: Aug, August; Feb, February; IPD, invasive pneumococcal disease; Jul, July; Jun, June; m, months; Nov, November; Oct, October; PCV13, 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; y, years.

Refitting the regression models with serotype-specific carriage prevalence data yielded a similar conclusion about the stronger association with carriage data from older children. In particular, the serotype prevalence in carriage among children aged 36 months and older provided the best fit to the IPD data for all ages (Supplementary Table 1). Patterns were consistent when stratifying by those with or without respiratory complaints.

DISCUSSION

While the serotypes colonizing children are broadly similar around the world, the serotypes causing disease in children and adults vary between age groups and settings [6, 28]. Although children younger than 5 years of age are often considered as a single homogenous group when evaluating carriage patterns, our analyses demonstrate that serotype prevalence differs by age. Among the Jewish population in Israel, serotype-specific carriage patterns differ between children younger than 24 months of age and those 24–59 months of age, and the patterns in older children better correlated with patterns of IPD in adults. This finding, along with recent work evaluating the postvaccine trajectories of carriage and IPD [14, 16], suggests that preschoolers might play a more important role in transmission to adults than infants and toddlers. This has important implications when considering the possible public health impact of different dosing schedules and the timing of booster doses. If older children are important for transmission, then it is critical to ensure that they are protected adequately against colonization.

Importantly, these results highlight that serotype-specific IPD patterns in adults do not always reflect carriage patterns in children (considered the reservoir of pneumococcus in the population). For example, the current high rates of IPD in adults that started in 2015/2016 caused by serotypes 8 and 12F were not predicted by carriage surveillance in children in England and Wales [11], nor in the Netherlands [29]. For any strategy aiming to prevent pneumococcal disease, the presence of a large pneumococcal reservoir in older children or adults is an essential factor to consider. Carriage-based surveillance should be designed to address this possibility and to include older children or adults when the goal is to understand or predict indirect effects of PCVs. Further work is needed to understand the implications of these serotype/age patterns for vaccination strategies.

While we did not have adult carriage data from Israel, previous studies from the Netherlands have collected carriage data from both children [30] and adults [31]. Notably, there was a correlation between the serotypes that were overrepresented as causes of IPD in adults in Israel and the serotypes that were more common among adult carriers compared with pediatric carriers in the Netherlands (see Supplementary Figure 14). In addition, serotypes that were overrepresented as causes of IPD in adults in Israel were also those overrepresented as causes of IPD in adults in the Netherlands (as compared with children <5 years old) [10], both prior to and following PCV implementation.

The intensity of transmission might also influence the age distribution of serotypes in carriage, and subsequently, in disease. This study focused on the Jewish population in Israel, a population with relatively low transmission of pneumococcus. In this population, the older children attending daycare or preschool have more opportunities for transmission than those at home in isolation (predominantly infants) [13, 15]. The situation could differ in populations with higher intensity transmission [32]. Populations with higher intensity transmission tend to have a higher residual burden of VTs [32], as reported for serotypes 1 and 7F in a recent meta-analysis [33]. Higher intensity transmission would lead to earlier first-carriage episodes and more frequent exposure, as has previously been observed in Bedouin versus Jewish children in Israel [34]. An earlier age distribution of carriage in a high transmission setting leads to stronger immunity against the dominant strains (negative frequency-dependent selection [35]), potentially allowing the weaker serotypes to colonize older children who are more important for transmission. Conversely, in a low transmission setting, the immunity against the dominant serotypes might be lower, meaning that weaker serotypes are pushed to a later age when general immunity against pneumococcus is high, effectively restraining them within the population. The introduction of vaccines against the dominant serotypes can shift the age distribution of subdominant serotypes, influencing disease patterns in adults.

In conclusion, we identified age-related differences in serotype-specific disease, with certain serotypes over- or underrepresented in different age groups but also by comorbidity status. These differences are likely explained by differences in susceptibility or exposure to specific serotypes; enhanced carriage data from older children or adults and elderly individuals would help to further understand these patterns. These findings hold importance for those considering new vaccination strategies for infants and for the next generation of adult-specific pneumococcal vaccinations. This issue will gain urgency as current VTs continue to decline and NVTs increase as a cause of disease in adults.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. R. D. and D. M. W. conceived the study. G. R.-Y., N. G.-L., R. D., and D. M. W. managed the study and collected the data. A. L. W., J. L. W., G. R.-Y., and D. M. W. performed the analyses and interpreted the data. A. L. W. and D. M. W. drafted the manuscript. All authors amended and commented on the final manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Disclaimer. The funding agencies were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant numbers R01-AI123208, R01-AI137093; to D. M. W.) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number OPP1176267; to D. M. W.).

Potential conflicts of interest. A. L. W. has received research funding through grants from Pfizer and the National Basketball Association to Yale and has received consulting fees for participation in advisory boards for Pfizer. G. R.-Y. has received consulting fees and research funding from Pfizer and research support from GSK. R. D. has received consulting fees from Pfizer, MSD, and MeMed; research grants from Pfizer and MSD; and speaker fees from Pfizer. D. M. W. has received consulting fees from Pfizer, Merck, GSK, and Affinivax and has received research funding through grants from Pfizer to Yale. N. G.-L. reports grants from Pfizer and MSD, outside the submitted work. J. L. W. reports no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Jansen AG, Rodenburg GD, van der Ende A, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease among adults: associations among serotypes, disease characteristics, and outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:e23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wyllie AL, Rümke LW, Arp K, et al. Molecular surveillance on Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in non-elderly adults; little evidence for pneumococcal circulation independent from the reservoir in children. Sci Rep 2016; 6:34888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Simell B, Auranen K, Käyhty H, Goldblatt D, Dagan R, O’Brien KL; Pneumococcal Carriage Group . The fundamental link between pneumococcal carriage and disease. Expert Rev Vaccines 2012; 11:841–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Auranen K, Mehtälä J, Tanskanen A, S Kaltoft M. Between-strain competition in acquisition and clearance of pneumococcal carriage–epidemiologic evidence from a longitudinal study of day-care children. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 171:169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feikin DR, Kagucia EW, Loo JD, et al. ; Serotype Replacement Study Group . Serotype-specific changes in invasive pneumococcal disease after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction: a pooled analysis of multiple surveillance sites. PLoS Med 2013; 10:e1001517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hausdorff WP, Feikin DR, Klugman KP. Epidemiological differences among pneumococcal serotypes. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weinberger DM, Malley R, Lipsitch M. Serotype replacement in disease after pneumococcal vaccination. Lancet 2011; 378:1962–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scott JR, Millar EV, Lipsitch M, et al. Impact of more than a decade of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use on carriage and invasive potential in Native American communities. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:280–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wagenvoort GHJ, Sanders EAM, Vlaminckx BJ, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease: clinical outcomes and patient characteristics 2–6 years after introduction of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared to the pre-vaccine period, the Netherlands. Vaccine 2016; 34:1077–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Deursen AM, van Mens SP, Sanders EA, et al. ; Invasive Pneumococcal Disease Sentinel Surveillance Laboratory Group . Invasive pneumococcal disease and 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18:1729–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ladhani SN, Collins S, Djennad A, et al. Rapid increase in non-vaccine serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales, 2000-17: a prospective national observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flasche S, Van Hoek AJ, Goldblatt D, et al. The potential for reducing the number of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine doses while sustaining herd immunity in high-income countries. PLoS Med 2015; 12:e1001839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nurhonen M, Cheng AC, Auranen K. Pneumococcal transmission and disease in silico: a microsimulation model of the indirect effects of vaccination. PLoS One 2013; 8:e56079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weinberger DM, Pitzer VE, Regev-Yochay G, Givon-Lavi N, Dagan R. Association between the decline in pneumococcal disease in unimmunized adults and vaccine-derived protection against colonization in toddlers and preschool-aged children. Am J Epidemiol 2019; 188:160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Althouse BM, Hammitt LL, Grant L, et al. Identifying transmission routes of Streptococcus pneumoniae and sources of acquisitions in high transmission communities. Epidemiol Infect 2017; 145:2750–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Flasche S, Lipsitch M, Ojal J, Pinsent A. Estimating the contribution of different age strata to vaccine serotype pneumococcal transmission in the pre vaccine era: a modelling study. BMC Med 2020; 18:129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Regev-Yochay G, Paran Y, Bishara J, et al. ; IAIPD Group . Early impact of PCV7/PCV13 sequential introduction to the national pediatric immunization plan, on adult invasive pneumococcal disease: a nationwide surveillance study. Vaccine 2015; 33:1135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ben-Shimol S, Givon-Lavi N, Greenberg D, Dagan R. Pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage in children <5 years of age visiting the pediatric emergency room in relation to PCV7 and PCV13 introduction in southern Israel. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016; 12:268–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Regev-Yochay G, Katzir M, Strahilevitz J, et al. ; IAIPD Group . The herd effects of infant PCV7/PCV13 sequential implementation on adult invasive pneumococcal disease, six years post implementation; a nationwide study in Israel. Vaccine 2017; 35:2449–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weinberger DM, Grant LR, Weatherholtz RC, Warren JL, O’Brien KL, Hammitt LL. Relating pneumococcal carriage among children to disease rates among adults before and after the introduction of conjugate vaccines. Am J Epidemiol 2016; 183:1055–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brueggemann AB, Peto TEA, Crook DW, Butler JC, Kristinsson KG, Spratt BG. Temporal and geographic stability of the serogroup-specific invasive disease potential of Streptococcus pneumoniae in children. J Infect Dis 2004; 190:1203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Plummer M, Stukalov A, Denwood M JAGS: a program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using gibbs sampling. In Proc. 3rd International Workshop on Distributed Statistical Comptuting. DSC, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23. RStudio-Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, PBC. Available at: http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, van der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J R Stat Soc Ser B 2002; 64:583–639. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Croucher NJ, Finkelstein JA, Pelton SI, et al. Population genomics of post-vaccine changes in pneumococcal epidemiology. Nat Genet 2013; 45:656–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gladstone RA, Lo SW, Lees JA, et al. ; Global Pneumococcal Sequencing Consortium . International genomic definition of pneumococcal lineages, to contextualise disease, antibiotic resistance and vaccine impact. EBioMedicine 2019; 43:338–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abu Seir R, Azmi K, Hamdan A, et al. Comparison of early effects of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: PCV7, PCV10 and PCV13 on Streptococcus pneumoniae nasopharyngeal carriage in a population based study: the Palestinian-Israeli Collaborative Research (PICR). PLoS One 2018; 13:e0206927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hausdorff WP, Bryant J, Paradiso PR, Siber GR. Which pneumococcal serogroups cause the most invasive disease: implications for conjugate vaccine formulation and use, part I. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 30:100–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vissers M, Wijmenga-Monsuur AJ, Knol MJ, et al. Increased carriage of non-vaccine serotypes with low invasive disease potential four years after switching to the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in The Netherlands. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0194823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wyllie AL, Wijmenga-Monsuur AJ, van Houten MA, et al. Molecular surveillance of nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in children vaccinated with conjugated polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccines. Sci Rep 2016; 6:23809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krone CL, Wyllie AL, van Beek J, et al. Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in aged adults with influenza-like-illness. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0119875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lourenço J, Obolski U, Swarthout TD, et al. Determinants of high residual post-PCV13 pneumococcal vaccine-type carriage in Blantyre, Malawi: a modelling study. BMC Med 2019; 17: 219. Available at: 10.1186/s12916-019-1450-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Balsells E, Dagan R, Yildirim I, et al. The relative invasive disease potential of Streptococcus pneumoniae among children after PCV introduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2018; 77:368–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lewnard JA, Huppert A, Givon-Lavi N, et al. Density, serotype diversity, and fitness of streptococcus pneumoniae in upper respiratory tract cocolonization with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:1411–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Corander J, Fraser C, Gutmann MU, et al. Frequency-dependent selection in vaccine-associated pneumococcal population dynamics. Nat Ecol Evol 2017; 1:1950–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.