ABSTRACT

The opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa can utilize unusual carbon sources, like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and alkanes. Whereas the initiating enzymatic steps of the corresponding degradation pathways have been characterized in detail, the oxidation of the emerging long-chain alcohols has received little attention. Recently, the genes for the Lao (long-chain-alcohol/aldehyde oxidation) system were discovered to be involved in the oxidation of long-chain alcohols derived from SDS and alkane degradation. In the Lao system, LaoA is predicted to be an alcohol dehydrogenase/oxidase; however, according to genetic studies, efficient long-chain-alcohol oxidation additionally required the Tat-dependent protein LaoB. In the present study, the Lao system was further characterized. In vivo analysis revealed that the Lao system complements the substrate spectrum of the well-described Exa system, which is required for growth with ethanol and other short-chain alcohols. Mutational analysis revealed that the Tat site of LaoB was required for long-chain-alcohol oxidation activity, strongly suggesting a periplasmic localization of the complex. Purified LaoA was fully active only when copurified with LaoB. Interestingly, in vitro activity of the purified LaoAB complex also depended on the presence of the Tat site. The copurified LaoAB complex contained a flavin cofactor and preferentially oxidized a range of saturated, unbranched primary alcohols. Furthermore, the LaoAB complex could reduce cytochrome c550-type redox carriers like ExaB, a subunit of the Exa alcohol dehydrogenase system. LaoAB complex activity was stimulated by rhamnolipids in vitro. In summary, LaoAB constitutes an unprecedented protein complex with specific properties apparently required for oxidizing long-chain alcohols.

IMPORTANCE Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a major threat to public health. Its ability to thrive in clinical settings, water distribution systems, or even jet fuel tanks is linked to detoxification and degradation of diverse hydrophobic substrates that are metabolized via alcohol intermediates. Our study illustrates a novel flavoprotein long-chain-alcohol dehydrogenase consisting of a facultative two-subunit complex, which is unique among related enzymes, while the homologs of the corresponding genes are found in numerous bacterial genomes. Understanding the catalytic and compartmentalization processes involved is of great interest for biotechnological and hygiene research, as it may be a potential starting point for rationally designing novel antibacterial substances with high specificity against this opportunistic pathogen.

KEYWORDS: long-chain-alcohol oxidation, flavin-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase, protein complex, hitchhiker mechanism, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, cytochrome c, rhamnolipids, SDS degradation, Tat system, alcohol dehydrogenase, flavoenzymes

INTRODUCTION

Survival and growth of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hostile anthropogenic environments, such as hand soap or jet fuel tanks (1, 2), is significantly supported by its ability to utilize a multitude of unusual carbon sources. These include alkanes and the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), the degradation of which is initiated by monooxygenases and an alkylsulfatase, respectively (3–6). Apart from the metabolic pathways, there are also cellular adaptations required for utilizing alkanes and SDS. In particular, alkanes can be solubilized by secreted biosurfactants, such as rhamnolipids (7–9), and the utilization of the toxic SDS requires energy-dependent resistance mechanisms, including cell aggregation (10).

Whereas enzymes involved in the initial steps of SDS or alkane degradation are well investigated (4, 6), the enzymes responsible for the metabolization of the emerging long-chain alcohols are less well elucidated. As the principal metabolic route to β-oxidation is obvious, the respective alcohol oxidation systems have not received much attention, on the assumption that they might not differ very much from well-studied alcohol dehydrogenases involved in the utilization of short-chain alcohols like ethanol (11). However, long-chain alcohols have strongly reduced water solubility and are therefore likely to demand different properties of the respective dehydrogenases. In general, long-chain alcohols are widespread in the environment and occur, e.g., as part of wax esters produced by animals, plants, and bacteria for numerous purposes, such as energy storage, protection, thermal insulation or prevention of desiccation (12, 13). Long-chain alcohols are also commercially used for the production of surfactants, food, cosmetics, and industrial solvents (14). Despite their widespread distribution, an enzymatic system for the oxidation of long-chain alcohols derived from alkanes and SDS was only recently discovered in P. aeruginosa and consists of proteins encoded by the laoCBA operon, which is induced by derepression of the TetR-type regulator LaoR with coenzyme A (CoA) esters of long-chain fatty acids as ligands (15, 16).

According to the phenotype of the respective deletion mutants, LaoA (PA0364; 57.8 kDa) and LaoB (PA0365; 19.6 kDa) are both required for long-chain-alcohol oxidation, while the aldehyde dehydrogenase LaoC is not required and can be replaced by alternative enzymes (15). LaoA classifies as glucose-methanol-choline (GMC)-type oxidoreductase but shows only limited similarity to characterized members of this enzyme family. Among the most similar enzymes is a long-chain-alcohol oxidase of Lotus japonicus with 18% identity and 31% similarity (17), which does not, however, depend on an accessory protein, as seems to be the case for LaoA. LaoB is a confirmed Tat substrate (18). Homologs (identity > 50%) of LaoB are widely found among different bacteria, none of which have been functionally characterized or exhibit any resemblance to existing protein structures. However, a Tat export leader peptide is predicted in almost all entries. The only functionally characterized protein with appreciable similarity to LaoB (30% similarity/18% identity) was found to be subunit III of gluconate 2-dehydrogenase of Erwinia cypripedii ATCC 29267 (19). Gluconate 2-dehydrogenase is a membrane-bound enzyme comprising three closely interacting subunits (20). While LaoA shares similarity with subunit I (17%/29% identity), no equivalent of subunit II is found. The N-terminal region of LaoB, moreover, has some similarity to dye-decolorizing peroxidases in which heme-dependent electron transfer is observed (pfam identifier pfam04261).

Apart from the Lao system, the well-studied Exa system (21) was also induced in SDS-grown cells (22). The Exa system comprises ExaA, a pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ)-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase, and ExaB, a cytochrome c550 electron shuttle subunit. ExaA and orthologs exhibit broad substrate specificity (23, 24). However, the Exa system is dispensable for growth with alkanes or SDS and can only partly compensate for the loss of the Lao system (15). This observation indicates that, while the mere oxidation of the hydroxyl group may be a trivial reaction, the detailed action of specific long-chain-alcohol oxidation systems goes beyond redox chemistry and calls attention to specific properties of LaoA and LaoB for coping with the hydrophobicity of the substrates. These properties could relate to the substrate spectrum, localization, and electron transfer, as well as to potential factors supporting the activity of LaoA and LaoB. The goal of our study was to elucidate these properties of the Lao system both in vivo and in vitro, with purified proteins, also addressing the individual functions of LaoA and LaoB.

RESULTS

The Lao system serves as a medium- to long-chain-alcohol oxidation system.

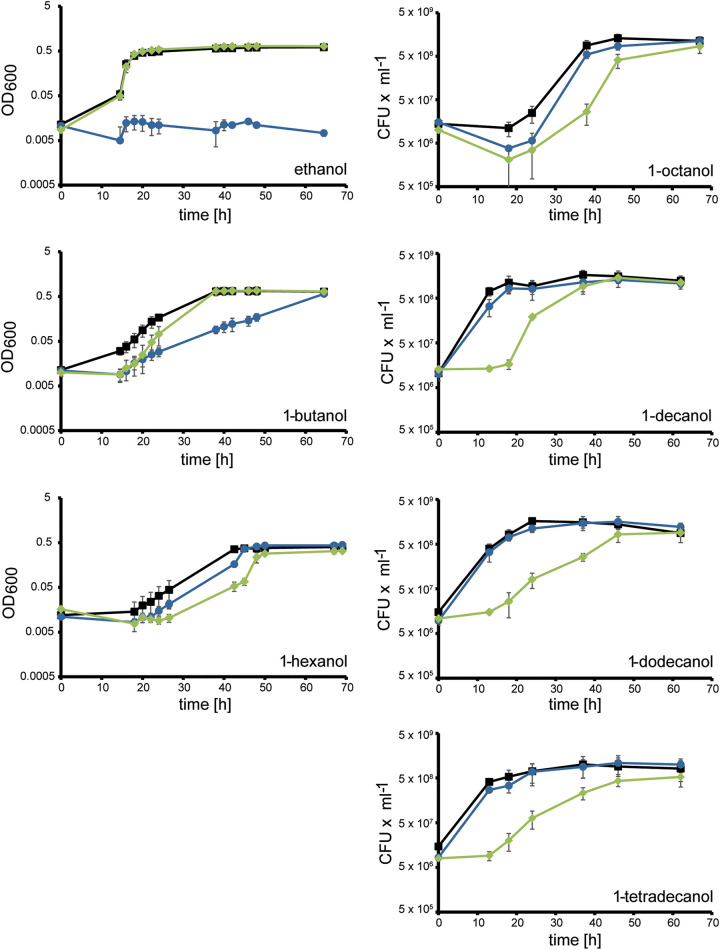

For investigating the functions of the Lao and Exa systems for the degradation of alcohols with different chain lengths in vivo, the growth of wild-type strain PAO1 and alcohol dehydrogenase deletion strains PAO1ΔexaA and PAO1ΔlaoA with primary alcohols as carbon and energy sources were analyzed (Fig. 1). Deletion of exaA led to lack of growth with ethanol, delayed growth with 1-butanol up to 1-octanol, and no phenotypic difference in growth with 1-decanol up to 1-tetradecanol. In contrast, deletion of laoA did not alter growth with ethanol. Delayed growth was monitored from 1-hexanol to 1-octanol, and a severely delayed onset of growth was observed with 1-decanol up to 1-tetradecanol. These results indicate complementary roles of the two alcohol oxidation systems, with the Exa system ranging from essential to important in short-chain-alcohol metabolism and the Lao system being required for a quick onset of growth and a high growth rate with long-chain alcohols. In contrast to prolonged lag phase and decreased growth rates, the final optical densities and maximal viable counts of strain PAO1ΔlaoA did not differ from those of the wild type with long-chain alcohols; this confirmed our previous observation that the Lao system can be complemented by the Exa system and potentially also by other so-far-unknown alcohol dehydrogenases, although with lower efficiency (15).

FIG 1.

Growth of P. aeruginosa PAO1 wild type (squares) and the deletion mutants PAO1ΔexaA (circles) and PAO1ΔlaoA (diamonds) with the primary alcohols (C2 to C14) indicated in the individual panels. Alcohols were provided at carbon amounts equivalent to 3.5 mM 1-dodecanol as sole carbon and energy sources. Results of one representative of three independent experiments are shown. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3).

Tat-dependent processing is required for long-chain-alcohol oxidation activity.

As LaoB is a confirmed Tat substrate (18), a plausible function for long-chain-alcohol oxidation could be the translocation of LaoA across the cytoplasmic membrane. Therefore, we investigated the influence of the Tat translocation on the activity of the Lao system in vivo by constructing a mutant, LaoB*, devoid of the highly conserved Tat signal twin-arginine motif (R13G, R14G). This exchange is assumed to prohibit the Tat-dependent translocation of the protein (25–29). A LaoB deletion strain, PAO1ΔlaoB, was complemented with laoB* [PAO1ΔlaoB(pUCP18::laoB*)] or the native laoB [PAO1ΔlaoB(pUCP18::laoB)], and all strains, including an empty vector control, were analyzed in growth experiments with the substrates 1-dodecanol and SDS (Fig. 2A and B). Whereas 1-dodecanol is a primary substrate of the Lao system, SDS was chosen due to its solubility and the availability of a facile quantification procedure. SDS quantification and growth with 1-dodecanol as the sole carbon and energy source clearly showed that strain PAO1ΔlaoB(pUCP18::laoB*) behaved similarly to the deletion strain PAO1ΔlaoB, indicating that Tat transport is essential for full functionality of the Lao system in vivo.

FIG 2.

Analysis of the Tat motif of LaoB with P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 (filled circles), PAO1ΔlaoB (filled triangles), PAO1ΔlaoB(pUCP18::laoB) (open circles), and PAO1ΔlaoB(pUCP18::laoB*) (open triangles). (A) Growth of strains with 3.5 mM 1-dodecanol as the sole carbon and energy source. (B) SDS quantification of supernatants from cultures grown with 3.5 mM SDS as the sole carbon and energy source. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3).

Copurification of LaoA and LaoB indicates physical interaction.

For analyzing the functions of LaoA and LaoB in more detail, we attempted to purify the proteins. LaoA was purified by means of Strep-Tactin affinity chromatography. The heterologously produced protein showed a characteristic flavoprotein spectrum (data not shown) and was stable in various buffers at a concentration of 1 mg ml−1, showing no precipitation after 24 h at 4°C. However, neither oxidase nor dehydrogenase activity could be detected (for assay conditions, see Materials and Methods). This lack of activity raised the question of whether LaoB not only is required for transport but also may be important for the enzymatic activity. We therefore attempted to overexpress and purify LaoB from recombinant Escherichia coli by means of C-terminal His or streptavidin (Strep) tag affinity chromatography. However, neither soluble nor membrane-bound protein could be obtained regardless of tag placement and cultivation conditions. In a third approach, we coexpressed C-terminally Strep-tagged LaoA and untagged LaoB, followed by Strep-Tactin affinity chromatography. Interestingly, this coexpression eventually led to catalytically active protein, using 1-octanol as the substrate and phenazine methosulfate (PMS) and dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) as the electron acceptor pair. As LaoA could be purified in the absence of LaoB, we concluded that either LaoA is activated by LaoB in vivo by a yet-unknown mechanism or both proteins form a complex that is nonobligatory for the stability of LaoA but required for its enzymatic activity. SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A) revealed LaoA (55 kDa) with minor amounts of LaoB (21 kDa) in the purified fraction. We concluded that LaoA and LaoB form a complex of unknown stoichiometry, in which LaoA is stable, but not active, in the absence of LaoB, whereas LaoB requires LaoA for stability.

FIG 3.

In vitro characterization of the LaoAB complex. In all experiments, LaoA and LaoB were coexpressed in E. coli Rosetta; in all panels, LaoA-containing signals are indicated by black triangles, while signals containing LaoB only are indicated by white triangles. (A) SDS-PAGE (12.5%) of purified LaoA-Strep coexpressed with untagged LaoB (2). (B) Activity staining. Lane 1, LaoA-Strep catalyzed 1-dodecanol oxidation activity bands in native PAGE (6%). Lanes 2 to 4, Western blot of LaoA-Strep separated in a native PAGE gel (6%) and blotted with HRP-conjugated Strep-tag antibody. (C) Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of purified LaoA-Strep comprising native PAGE (6%, activity-stained for reference) followed by SDS-PAGE and detection of LaoA-Strep and LaoB by silver staining. (D) Western blot analysis with HRP-conjugated Strep or His tag antibody of purified LaoA-Strep and LaoB-His fractions (10 μg protein each) after separation by SDS-PAGE. Strep, streptavidin-purified fraction; His, Ni-NTA-purified fraction.

For analyzing whether LaoB could indeed influence catalytic activity, we performed native gel electrophoresis coupled to in-gel activity staining (Fig. 3B). Strep-purified LaoAB showed two bands with catalytic activity (Fig. 3B, lane 1), indicating that at least two productive protein species exist. Western blotting and immunodetection revealed the presence of LaoA-Strep in both bands (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 to 4). To analyze the occurrence and co-occurrence of LaoA and LaoB within these active bands, we performed a two-dimensional separation of the purified fraction with native electrophoresis as the first and SDS-PAGE as the second dimension (Fig. 3C). The silver-stained gel illustrates that LaoA migrated in various conformations, not all of which exhibited catalytic activity in the native PAGE. Remarkably, the upper activity band contains mainly LaoA. In contrast, LaoB migrated as a singular band to a position correlating with the lower-migrating activity band. The concentration of LaoA, as well as the total protein concentration at this position, is very low. Hence, it is valid to conclude that the lower-migrating activity band corresponds to a highly active species comprising LaoA and LaoB. In contrast, the upper activity band was probably caused by a low-activity LaoA species. The low-activity species might have been artificially formed as a result of overexpression in the heterologous host or nonnative in vitro conditions.

The observation of a high-activity species comprising LaoA and LaoB (Fig. 3A and C) raised the question of whether a stable physical interaction between both proteins exists. To this end, we coexpressed C-terminally Strep-tagged LaoA (LaoA-Strep) and His-tagged LaoB (LaoB-His). Following copurification with either Strep-Tactin column chromatography or immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC), we analyzed elution fractions by Western blotting and immunodetection. Substantial amounts of LaoA-Strep were detected in the elution fraction of the IMAC chromatography, and conversely, LaoB-His was detected in Strep-Tactin chromatography fractions, which confirmed copurification of both proteins (Fig. 3D) mediated by protein-protein interaction. Moreover, LaoB-His was found to occur in two forms, the larger of which probably lacked the Tat signal peptidase-dependent truncation.

Taken together, these results indicate that LaoA and LaoB do apparently form a stable protein complex of unknown stoichiometry. This complex is required for the enzymatic activity of alcohol oxidation and is referred to here as the LaoAB complex.

Additionally, we coexpressed laoB* and laoA-Strep in E. coli and purified the proteins as described above. Unexpectedly, while LaoAB* was likewise accessible to affinity purification, the variant showed only a fraction of wild-type catalytic activity, indicating that the Tat signal, or signal peptidase processing, may also be important for the enzymatic activity of LaoAB (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Activity staining with purified proteins. Oxidation of 1-dodecanol by 10 μg purified LaoA-Strep (lane 1), LaoA-Strep coexpressed with LaoB* (lane 2), or LaoA-Strep coexpressed with LaoB (lane 3) in native PAGE (6%).

The LaoAB complex is not associated with membranes.

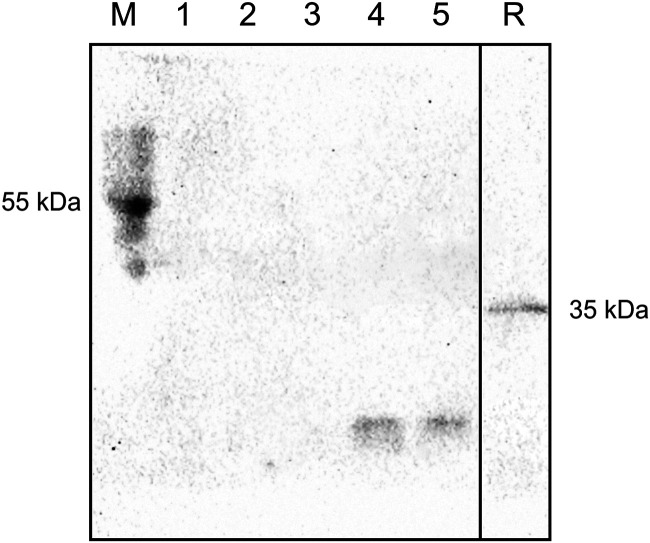

As a substrate for the Tat translocation system, LaoB may be either fully or partly transported across the cytoplasmic membrane; in the latter case, LaoB would be integrated into the cytoplasmic membrane. To resolve this question, we expressed an allele of laoAB in which a StrepII sequence was fused to the C terminus of LaoB in P. aeruginosa ΔlaoB and prepared membrane and soluble fractions. Western blot analysis showed that LaoB-Strep was absent in the membrane fraction (Fig. 5). Upon enrichment by Strep-Tactin chromatography, LaoB-Strep could be detected in clarified cell extracts from which membranes had been removed by ultracentrifugation. LaoB could also be concentrated from uncleared cell lysates to a similar extent, suggesting that, despite plasmid-based expression, the protein is produced at a low concentration (or underlies rapid degradation) and is found exclusively in the soluble fraction of the cell extract. In conclusion, the results of the experiments regarding Tat dependency and the coexpression analysis together with this localization experiment strongly suggested that LaoAB is a soluble complex of the periplasmic compartment.

FIG 5.

Localization of LaoB in the soluble cell fraction, as determined by Western blotting and immunodetection. Cells of P. aeruginosa PAO1ΔlaoB(pME6032::laoAB-Strep) (expression strain) and PAO1ΔlaoB(pME6032) (vector control) were disrupted (cell extract) and cleared of debris before the membrane fraction was separated from the soluble fraction by ultracentrifugation. Lanes contain membrane fraction (lane 1) and membrane-free soluble fraction (lane 2) of the expression strain without enrichment by affinity chromatography, and cell extract of vector control (lane 3), cell extract (lane 4), and membrane-free cell soluble fraction of the production strain (lane 5) after enrichment by affinity chromatography. The recombinantly expressed and purified protein Strep-PqsD (20 ng, 35 kDa; lane R) of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (our unpublished data) served as a reference for the staining. Complex samples were loaded at 50 μg per lane. The prestained PAGE ruler, which features a StrepII epitope in the 55-kDa band, was used as a marker and transfer control (M).

LaoAB complex is an FAD-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase.

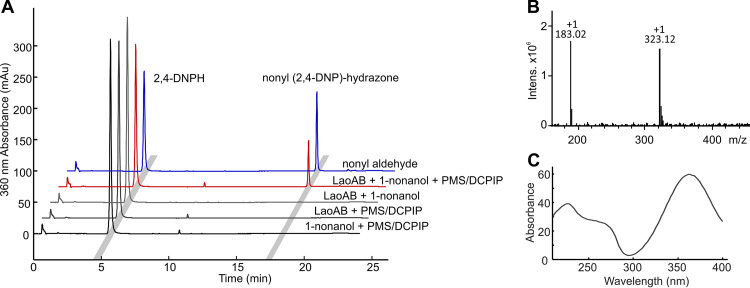

In the next step, the cofactor and electron acceptor preferences of the LaoAB complex were analyzed. FAD, corresponding to a mass of 784.32 Da (m/z = [M-H]−), was identified by mass spectrometry as the sole flavin species copurified with the LaoAB complex (data not shown). Cofactor occupancy was almost 100%, as estimated from UV–visible-spectrum (Vis) spectroscopy. Oxidase activity was assayed by scavenging hydrogen peroxide, which would result from an oxidase-like reaction, with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and 2,2′-azino-bis 3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) (30). Despite testing different substrates and buffer conditions, no hydrogen peroxide production of the LaoAB complex was detected, which excludes an oxidase-type reaction. As indicated above, the electron acceptor couples PMS-NBT (phenazine methosulfate and nitroblue tetrazolium chloride) for in-gel staining (15), and PMS-DCPIP for spectrophotometric measurement could be employed for the LaoAB complex activity assays, which strongly indicates a dehydrogenase-type reaction. The formation of fatty aldehydes as the reaction product of catalysis was verified by derivatization with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine. With 1-nonanol as the reference substrate in liquid-phase assays, we detected the nonyl-dinitrophenylhydrazone by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with LaoAB only when the electron acceptors PMS and DCPIP were present (Fig. 6A). The identity of the reaction product was verified by its mass and UV spectra (Fig. 6B and C, respectively) in comparison with authentic nonyl aldehyde.

FIG 6.

Verification of nonyl aldehyde as reaction product of LaoAB with 1-nonanol. Recombinant LaoAB (1 μM) was incubated with 50 μM 1-nonanol, the most efficient substrate of the reaction in solution, and an excess of PMS and DCPIP as electron acceptors. (A) Aldehydes formed were derivatized with 2,4-DNPH (2 mM) and analyzed by HPLC (red trace) coupled to electrospray ionization with MS (ESI-MS). Identity of the putative nonyl-2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone was confirmed with authentic nonyl aldehyde (blue trace) and suitable controls (black traces). (B) The mass spectrum obtained between 18.4 and 18.5 min shows the nonyl adduct (322 m/z), as well as a 2,4-dinitrophenyl azan fragmentation product (182 m/z). (C) The UV spectrum of the compound is characteristic of DNPH adducts, with an absorption maximum at 360 nm.

Cytochrome c-like electron acceptors are reduced by the LaoAB complex.

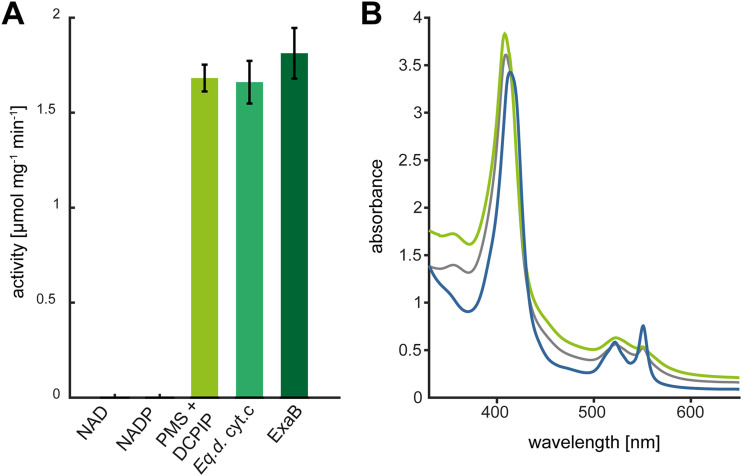

In search of the physiological electron acceptor, we tested NAD+, NADP+, and commercially available horse heart cytochrome c for their capability to support alcohol oxidation by LaoAB. While no activity was detected with NAD+ and NADP+, reduction of oxidized horse heart cytochrome c could be measured spectrophotometrically at 550 nm upon addition of the model substrate 1-nonanol, which is indicative of reduction of the cytochrome-internal heme iron (31). The detected activity was comparable to the activity measured with PMS-DCPIP (Fig. 7A).

FIG 7.

Evaluation of electron acceptors for the LaoAB complex in vitro. (A) Catalytic activity of purified LaoAB complex with 800 μM 1-nonanol in the presence of different electron acceptors. Horse heart cytochrome c (Eq.d. cyt.c) and ExaB reductions were calculated based on differential extinction coefficient of cytochrome c. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). (B) Spectroscopic analysis of ExaB reduction by the LaoAB complex. The gray trace corresponds to ExaB as isolated (30 μM), and the green trace shows ExaB after oxidation with ammonium persulfate. Reduction of ExaB with the LaoAB complex and 1-nonanol led to the blue spectrum.

With regard to the coinduction of the Lao and the Exa systems during growth with SDS (22), we hypothesized that ExaB, the cytochrome component of the ExaAB alcohol dehydrogenase, could serve as a physiological electron acceptor for LaoAB. For in vitro testing, we purified ExaB as a Strep-tagged fusion protein from overexpressing E. coli cells. Despite low overall yields, the characteristic Soret and beta bands of the ExaB heme cofactor could be clearly identified (Fig. 7B). ExaB was purified in a partially reduced state and therefore required oxidation by ammonium persulfate. Oxidized ExaB was then desalted and used as the electron acceptor with LaoAB and 1-nonanol. Assays revealed that maximum initial velocity of heme reduction by LaoAB was achieved at a concentration of 30 μM ExaB, indicating an efficient electron transfer (Fig. 7A). However, experiments with an exaB deletion revealed that it was not essential for growth with SDS (data not shown), indicating that it is not an essential electron acceptor for LaoAB.

LaoAB complex oxidizes a broad range of hydrophobic alcohols.

In the next step, we investigated the potential of LaoAB for oxidation of different alcohols. As spectrophotometric assays are limited by substrate solubility, alcohols with more than 10 C atoms were assayed by in-gel activity staining (Table 1). Long-chain alcohols up to a chain length of C16 could be proven to be converted by LaoAB (Table 1). LaoAB also oxidized olefinic long-chain alcohols, branched-chain alcohols, and, albeit with lower efficiency, aryl-substituted primary alcohols such as cinnamyl alcohol. In addition, low catalytic activity for secondary alcohols such as 2-heptanol could be detected. Polar substituents, such as hydroxyl groups, and positive charge, e.g., amine groups, greatly diminished activity. Among saturated aliphatic primary alcohols, Km values decreased with increasing chain length, underlining the preference of the LaoAB complex for more hydrophobic substrates (Table 1). Strikingly, Vmax values decreased likewise, which probably reflects a higher-energy barrier for release of the increasingly hydrophobic aldehydes. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the long-chain aldehyde 1-nonanal showed a Ki which is only 20-fold higher than the Km for 1-nonanol.

TABLE 1.

Substrate specificity of LaoAB

| Substrate group | Compound | Conversion | Km | Vmax (μmol mg−1 min−1) | Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aliphatic | 1-Butanol | + | —a | —a | NAb |

| 1-Hexanol | + | 6.7 ± 0.4 mM | 4.4 ± 0.4 | NA | |

| 1-Heptanol | + | 1.7 ± 0.3 mM | 2.2 ± 0.2 | NA | |

| 1-Octanol | + | 350 ± 28 μM | 2.0 ± 0.2 | NA | |

| 1-Nonanol | + | 2.2 ± 0.1 μM | 1.6 ± 0.1 | NA | |

| 1-Decanol | + | <0.5 μMc | ≈1c | NA | |

| 1-Dodecanol | + | —c | —c | NA | |

| 1-Tetradecanol | + | —c | —c | NA | |

| 1-Hexadecanol | + | —c | —c | NA | |

| 6-Amino-1-hexanol | + | —c | —c | NA | |

| Olefinic | 3-Hexen-1-ol | + | 4.3 ± 0.6 mM | 1.3 ± 0.3 | NA |

| 4-Penten-1-ol | + | —c | —c | NA | |

| Branched chain | Citronellol | + | 511 ± 23 μM | 1.3 ± 0.2 | NA |

| Geraniol | + | 962 ± 72 μM | 0.7 ± 0.2 | NA | |

| Phytol | + | —c | —c | NA | |

| Isoprenol | + | —c | —c | NA | |

| Secondary alcohols | 2-Heptanol | + | 8.1 ± 0.6 mM | 0.6 ± 0.2 | NA |

| 2-octanol | + | —c | —c | NA | |

| Diols | 1,7-Heptandiol | + | 35 ± 11 mM | 0.2 ± 0.1 | NA |

| Aromatic | Cinnamyl alcohol | + | 20 ± 8 mM | 0.3 ± 0.1 | NA |

| Benzyl alcohol | − | NA | NA | NA | |

| Aldehydes | Nonanal | NA | NA | NA | 44 |

| Dodecanal | NA | NA | NA | ≈0.2c |

Protein was unstable.

NA, not applicable.

Insufficient data for reliable fitting.

The LaoAB complex activity is supported by glycolipids.

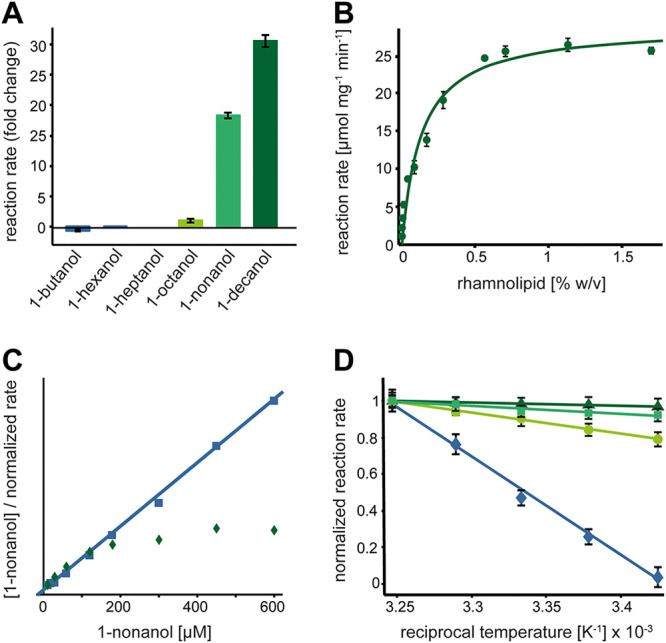

To solubilize the hydrophobic substrates for use in spectrophotometric assays, we screened different detergents for their effect on the LaoAB complex activity. While nonionic detergents like Triton X-100 and Brij 58 led to a slight decrease in activity, an increase in activity was observed when glycolipid-type detergents such as n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside or n-nonyl-β-d-glucopyranoside were added (data not shown). A strong stimulation of the LaoAB complex activity with the highly hydrophobic alcohols 1-nonanol and 1-decanol was observed upon addition of rhamnolipids (Fig. 8A). This stimulating effect was not observed with less-hydrophobic alcohol substrates and did not occur when LaoA or LaoAB* was used in the assays (data not shown).

FIG 8.

Influence of rhamnolipids on catalytic activity of the LaoAB complex. (A) Influence of 0.8% rhamnolipids. Substrate concentrations used for the assay were kept below the respective solubility limits, eliminating the influence on substrate solubilization by rhamnolipids (1-butanol, 10 mM; 1-hexanol, 5 mM; 1-heptanol, 2 mM; 1-octanol, 1 mM; 1-nonanol, 800 μM; 1-decanol, 100 μM). (B) Reaction rates as a function of rhamnolipid concentration at 800 μM 1-nonanol. A hyperbolic function can be used to fit the data, resulting in an EC50 of 0.16% (wt/vol). (C) Hanes-Woolf representation of LaoAB complex substrate dependency in the absence (squares) and presence (diamonds) of rhamnolipids. Addition of 0.3% rhamnolipids leads to a non-Michaelis-Menten characteristic of the reaction. In the absence of rhamnolipids, LaoAB complex catalysis corresponds to a typical Michaelis-Menten model (solid line). (D) Arrhenius plot illustrating the temperature dependency of the LaoAB complex at different concentrations of rhamnolipids (0% [diamonds], 0.2% [circles], 0.5% [squares], and 0.8% [triangles]). Slopes of the linear fits correspond to activation energies of the reaction under the respective conditions.

As the concentration of 1-nonanol (800 μM) was below its solubility limit of 930 μM (32), a solubilizing effect of the rhamnolipids on the substrate is unlikely. Rhamnolipids are biological detergents produced by P. aeruginosa (33), thus calling attention to a potentially specific stimulation mechanism. To investigate this possibility, we performed kinetic analyses of the influence of rhamnolipids on the LaoAB reaction with 1-nonanol as the substrate. Its oxidation depended on rhamnolipid concentration with a 50% effective concentration (EC50) of approximately 0.16% (wt/vol) (Fig. 8B). At first glance, these results suggested a participation of rhamnolipids in the reaction by, e.g., facilitating substrate access to the active center. However, the LaoAB complex activity deviated from a typical Michaelis-Menten characteristic when measured at different 1-nonanol concentrations in the presence of a fixed rhamnolipid concentration (Fig. 8C). Hyperbolic distribution of data points within the Hanes-Woolf linearization indicated that at low substrate concentrations, reaction rates were lower than expected for a given Km, whereas at higher substrate concentrations, the reaction was faster. The fact that no clear decrease in Km was observed argues against a beneficial partitioning effect by rhamnolipids, in which substrate-loaded micelles would enhance substrate affinity.

To further elucidate the mechanism by which the observed increase in Vmax is mediated, we measured whether rhamnolipids have a direct influence on the reaction’s activation energy or whether an unidentified indirect effect is involved with no influence on reaction energetics. As shown in the Arrhenius plot, shallower slopes of the line fits are observed at increasing concentrations of rhamnolipids, which corresponds to decreasing activation energies (Fig. 8D). The relative change of approximately 4-fold at 0.8% (wt/vol) rhamnolipids in the assay is substantial and can explain the severalfold increase in activity described above.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to investigate the role and the functionality of the Lao system both in vivo and in vitro. We found that the proteins LaoA and LaoB form an enzyme complex of unknown stoichiometry important for the quick onset of growth and high growth rates with hydrophobic long-chain alcohols. The LaoAB complex constitutes an alcohol dehydrogenase that contains FAD and can use ExaB, and likely other c-type cytochromes, as an electron acceptor. The existence of a stable complex is strongly supported by the observations that LaoB could be neither produced nor purified without coexpression of laoA and that LaoA could not be purified in an active state without coexpression of laoB. LaoAB and its orthologs thus represent a new, two-subunit architecture among GMC-family oxidoreductases.

While flavin-containing LaoA likely harbors the catalytic center of the complex, the function of LaoB with its Tat-specific signal peptide sequence is apparently more complex. On the one hand, LaoB had an essential function for the Tat-dependent translocation and indicated a periplasmic translocation of the LaoAB complex. We demonstrated that LaoB is unlikely to be inserted into the cytoplasmic membrane but rather resides in the soluble fraction of the periplasmic compartment. Hence, we propose that the proteins LaoA and LaoB assemble in a heterocomplex prior to LaoB-mediated translocation to the periplasm. This so-called “hitchhiker mechanism” has not been demonstrated in P. aeruginosa so far but has been reported for Tat-dependent processes in Escherichia coli (34–38). Remarkably, not only was the intact LaoB Tat signal sequence necessary for in vivo functionality, but it also strongly increased the catalytic activity of the LaoAB complex in vitro. Although protein maturation by signal peptidase cleavage is required for certain translocated protein substrates (reviewed in reference 39), we are not aware of any example in the prokaryotic domains where signal peptidase cleavage induces catalytic activity. The periplasmic localization of LaoAB fits perfectly with the postulated extracellular generation of 1-dodecanol from SDS by SdsA1 (4). However, primary long-chain alcohols derived from alkane hydroxylation are typically localized at the cytoplasmic site of the inner membrane in pseudomonads (40). To account for this apparent contradiction, it can be speculated that in the case of alkane degradation, the long-chain alcohols flip back into the periplasm for further oxidation.

Although LaoB has similarity to a conserved domain found within heme-dependent peroxidases with no canonical heme binding domain, a direct involvement in electron transfer is unlikely, because LaoAB* activity was strongly reduced regardless of whether a heme-containing redox protein or a small molecule electron acceptor was supplied to the reaction. An essential function in catalysis is also unlikely, because analysis of purified LaoAB by activity staining and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis revealed, in addition to a high-activity species comprising LaoA and LaoB, an activity band probably caused by a low-activity LaoA species, as no LaoB could be detected in the second dimension. The high-activity species probably constituted the native complex, as a band migrating to the same position was also found in extracts of alkane-metabolizing P. aeruginosa cells (15). Minor activity within the upper band may be either an artifact of crowding within the gel matrix or a result of minute occurrence of LaoB at the position, e.g., complexes smearing or diffusion within the gel matrix over time.

As neither LaoA nor LaoAB* was stimulated by rhamnolipids, the activating effect of LaoB on LaoA must be different from that exerted by these glycolipid-like detergents, which presumably have a role in substrate provision and/or product abstraction. We therefore hypothesize a function for LaoB in inducing a catalytically active conformation in LaoA by structural support or by an unknown mechanism.

The dissociation of hydrophobic products from enzymes is energetically highly disfavored (41, 42). Accordingly, in vitro activity of the LaoAB complex is diminished by product inhibition with, e.g., 1-nonanal. The stimulation of LaoAB complex activity by rhamnolipids in vitro is intriguing because rhamnolipids are endogenous biosurfactants of P. aeruginosa known to stimulate alkane degradation (9, 43–46). Due to the rhamnolipids' low critical micellar concentration of 5 to 380 mg/liter (R90 product data sheet; Sigma-Aldrich), these compounds have a strong tendency to form micelles, thereby encasing hydrophobic substrates in hydrophilic environments. From these properties, it would have been reasonable to suspect that rhamnolipids decrease the LaoAB complex activity in vitro due to lowering overall substrate availability or, alternatively, increase Km due to binding of both substrate and product molecules. The observation that the LaoAB complex activity instead was strongly stimulated by rhamnolipids and other glycolipid-type detergents in vitro, whereas other nonionic detergents did not, supports the hypothesis of a specific mechanism or recognition of rhamnolipids or, alternatively, other unknown amphiphilic glycosylated compounds. Since a decrease in activation energy of the reaction was observed when rhamnolipids were present, we suggest that the dissociation of the hydrophobic aldehyde out of the catalytic site is facilitated by rhamnolipids, turning a high-energy-barrier protein-to-solution transition of the product into a low-energy-barrier protein-to-micelle-transition. However, the biosynthesis of rhamnolipids is not always induced in alkane- or SDS-degrading P. aeruginosa strains, which excludes an essential role of rhamnolipids for the LaoAB complex activity (22, 47). This is supported by the fact that a rhlR mutant did not differ from the wild type (WT) during growth with 1-dodecanol (data not shown). The limiting step of product release from the LaoAB complex might in vivo also be compensated for by rapid elimination of the aldehyde product by cytoplasmic aldehyde dehydrogenases like LaoC and CoA activation of the resulting long-chain fatty acid in the cytoplasm by a so-far-unknown acyl-CoA ligase (15).

The purified LaoAB complex showed a broad substrate spectrum with increasing activities observed for increasingly hydrophobic alcohols. Besides saturated long-chain alcohols, conversion of olefinic fatty and branched-chain alcohols, alcohols with aryl substituents, diols, and secondary alcohols was detected. These properties signify that the LaoAB complex is a well-adapted enzyme system for passing very hydrophobic substrates into the further metabolic pathways for breakdown. Generally, long-chain alcohols have toxic effects (48); this could explain the low growth yields observed for the C8 to C14 alcohols. To this end, LaoAB can also act as a detoxification system. Considering the occurrence of long-chain alcohols in industrial settings and the prevalence of P. aeruginosa in locations associated with human activity (49), the utilization of such substrates might be among the key properties for growth and survival of this opportunistic pathogen in anthropogenic environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth experiments.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 2. Cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or in M9 mineral medium (50, 51) with various carbon and energy sources (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The water-insoluble and solid substrates were weighed into sterile tubes and treated with UV light for 20 min for sterilization. Bacterial strains were maintained on LB agar plates (1.5% [wt/vol]). Escherichia coli strains harboring plasmids were maintained and selected on LB agar plates (1.5% [wt/vol]) with 100 μg ml−1 carbenicillin (Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany) or 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin (Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany). For E. coli, ST18 media were supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 5-aminolevulinic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Plasmid-harboring P. aeruginosa strains were maintained and selected on LB agar plates (1.5% [wt/vol]) with 200 μg ml−1 carbenicillin or 100 μg ml−1 tetracycline. For growth experiments in liquid M9 medium, the concentration was decreased to 50 μg ml−1. Growth was measured as the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) with a UV-mini 1240 photometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) or, for growth experiments in test tubes, with the Camspec M107 photometer (Spectronic Camspec, United Kingdom). As cultures in growth experiments with test tubes could not be diluted, OD600 values above 0.4 are underestimated, which could explain the relatively low final values observed in cultures with ethanol, 1-butanol, and 1-hexanol (Fig. 2). With water-insoluble C sources, growth was measured as CFU as described previously (52).

TABLE 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ||

| PAO1 | PAO1 Nottingham wild-type strain | Holloway collection |

| PAO1ΔexaA | exaA deletion mutant | 15 |

| PAO1ΔlaoB | laoB deletion mutant | 15 |

| PAO1ΔlaoB(pUCP18::laoB) | laoB deletion mutant complementation of laoB | 15 |

| PAO1ΔlaoB(pUCP18::laoB*) | laoB deletion mutant complementation of mutated laoB (R13G, R14G) | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | recA1 endA1 hsdR17 thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 deoR Δ(lacZYA-argF)U196 (ϕ80lacZΔM15) | 55 |

| ST18 | pro thi hsdR+ Tpr Smr; chromosome::RP4-2 Tc::Mu-Kan::Tn7/λpir ΔhemA | 56 |

| Rosetta 2(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) pRARE2 (Camr) | Merck |

| Rosetta 2(pET27bmod[laoA]) | LaoA-Strep overexpression | This study |

| Rosetta 2(pET27bmod[laoB]) | LaoB-Strep overexpression | This study |

| Rosetta 2(pET28a[laoBtrunc]) | Strep-LaoBtrunc overexpression | This study |

| Rosetta 2(pET23a[laoB]) | LaoB-His overexpression | This study |

| Rosetta 2(pET27bmod[laoA], pUCP18[laoB]) | LaoA-Strep overexpression in presence of LaoB | This study |

| Rosetta 2(pET27bmod[laoA], pET23a[laoB]) | LaoA-Strep overexpression in presence of LaoB-His | This study |

| Rosetta 2(pET27bmod[exaB]) | ExaB-Strep overexpression | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX18Ap | Gene replacement vector; Apr, sacB | 57 |

| pUCP18 | Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vector, Apr | 58 |

| pME6032 | Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vector, Tetr | 59 |

| pME6032::laoAB-strep | Expression of laoA and laoB Strep in P. aeruginosa | This study |

| pET27bmod | Overexpression vector; Kanr; C-terminal twin-Strep tag | 60 |

| pET23a | Overexpression vector; Apr; C-terminal His tag | Merck |

| pET28amod | Overexpression vector; Kanr; N-terminal twin-Strep tag | Merck |

| pET27bmod[laoA] | Vector with laoA-Strep for purification | This study |

| pET27bmod[laoB] | Vector with laoB-Strep for purification | This study |

| pET28a[laoBtrunc] | Vector with Strep-laoBtrunc (without Tat signal sequence) for purification | This study |

| pET23a[laoB] | Vector with laoB-His for purification/detection | This study |

| pET27bmod[exaB] | Vector with exaB-Strep for purification | This study |

For overnight precultures, 10-ml test tubes with 3 ml M9 medium with 10 mM succinate were inoculated from LB agar plates and incubated for 10 to 16 h in a rotary shaker at 30°C and 200 rpm (Minitron; INFORS HT GmbH, Bottmingen, Switzerland). Cells from precultures were centrifuged for 1.5 min at 10,000 × g and resuspended in M9 medium without a C source. Growth experiments were performed in 10-ml tubes with 3 ml liquid medium inoculated with prepared cell suspensions to an OD600 of 0.01 and cultivated at 30°C and 200 rpm (Minitron; INFORS HT GmbH, Bottmingen, Switzerland). Generally, three independent growth experiments with biological triplicates were performed. For growth experiments with SDS, 75 ml M9 medium in 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks without baffles was used; flasks were inoculated and incubated as described above. Samples for substrate quantification were collected, treated as previously described (15), and run in duplicate. For pME6032-dependent gene expression in P. aeruginosa, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added for induction, and 10 μM 1-dodecanol were added, intended to stabilize the produced LaoAB protein.

Construction of plasmids and strains.

For complementation of strains, laoB was amplified from genomic DNA of strain PAO1 (primers 1 and 2 [Table 3]) and cloned into the vector pUCP18 (Table 3) with XbaI and HindIII restriction sites. For purification and further analysis, LaoA was C-terminally tagged with a twin-Strep tag, LaoB was N- and C-terminally tagged with a twin-Strep tag and C-terminally tagged with a hexahistidine tag (His tag), and ExaB was C-terminally tagged with a twin-Strep tag. laoA, laoB, and exaB were amplified from genomic DNA of strain PAO1 (primers 3 to 10 [Table 3]) and cloned restriction-free into the modified vector pET27bmod or pET28a (Table 3), and transformed strains were checked with colony PCR (primers 19 and 20 [Table 3]). For the C-terminal His tag, laoB was amplified from genomic DNA of strain PAO1 (primers 11 and 12 [Table 3]) and cloned into vector pET23a (Table 3) with NdeI and HindIII restriction sites. Complementation plasmids or overexpression plasmids were transferred into the respective strains by transformation, and transformed strains were checked with colony PCR amplifying the multiple cloning site of the vector (primers 13 to 20 [Table 3]).

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| No. | Description | Sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | laoB*_fw | tatatctagaATGAGCGACACCACCCTTGAAAGCGCCGGCCTGTCCGGAGGCAG |

| 2 | laoB*_rev | tataaagcttTCAAGCGATCTTCGGCGG |

| 3 | laoA-Strep_fw | AACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATACCATGCCTGTACCCGATCTGTTCGCCGAGG |

| 4 | laoA-Strep_rev | CAAACTGCGGGTGACTCCATGCAGAGGCCCTGGCCAGGCGTTCGG |

| 5 | laoB-Strep_fw | AACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATACCATGAGCGACACCACCCTTGAAAGCGCCG |

| 6 | laoB-Strep_rev | CAAACTGCGGGTGACTCCATGCAGAAGCGATCTTCGGCGGTCCGGGGTAG |

| 7 | exaB-Strep_fw | ACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATACCATGAACAAGAACAACGTCTTGCGCGGCC |

| 8 | exaB-Strep_rev | CAAACTGCGGGTGACTCCATGCAGACTCGTCGACGTGCACGCTTTCCAG |

| 9 | Strep-laoB_fw | ACCCGCAGTTCGAAAAGGGTGCCGGCGTCACCGCCAGCCTCACCGGCT |

| 10 | Strep-laoB_rev | TCAGCGGTGGCAGCAGCCAACTCAAGCGATCTTCGGCGGTCCGGGGT |

| 11 | laoB-His_fw | tatacatatgAGCGACACCACCCTTGAAAG |

| 12 | laoB-His_rev | tataaagcttAGCGATCTTCGGCGGTCCG |

| 13 | pUCP18_fw | GAGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGG |

| 14 | pUCP18_rev | AGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGACGTT |

| 15 | pET23a_fw | GGAGACCACAACGGTTTCCC |

| 16 | pET23a_rev | TTGTTAGCAGCCGGATCTCA |

| 17 | pET28a_fw | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG |

| 18 | pET28a_rev | CTTTCAGCAAAAAACCCCTC |

| 19 | pET27b_fw | TATACACTATAGGGGAATTGTGAG |

| 20 | pET27b_rev | TATATCTTCCGGGGCGAGTTCTGG |

| 21 | laoB_f | ATGAGCGACACCACCCTTGA |

| 22 | laoA_r | TCAGGCCCTGGCCAGGC |

| 23 | strep_B_r | CCCTTCTCGaactgcgggtggctccaagcgatcttcggcggtccg |

| 24 | strep_A_f | cacccgcagttcgagaagggcagctgaGCCGCCCCCGGAACAATAC |

| 25 | laoBA_GA_f | caatttcacacaggaaacagATGAGCGACACCACCCTTGAAAGCG |

| 26 | laoBA_GA_r | tgatccgctagtccgaggccTCAGGCCCTGGCCAGGCG |

Restriction sites or nucleotides complementary to a vector are underlined; lowercase letters indicate bases that are not complementary to the respective genome or vector sequence; nucleotide exchanges are marked in bold.

For construction of pME6032::laoAB-Strep, laoA and laoB were amplified and the sequence of the StrepII tag was fused to the 3′ end of the laoB gene by PCR. Cloning primers featured adaptor sequences for hybridization (primers 21 to 26). The fragments were then cloned into a NcoI/XhoI-digested pME6032 plasmid with the NEbuilder Gibson assembly kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA).

All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing prior to transformation.

Purification of proteins.

For heterologous protein production in E. coli, strain BL21 Rosetta 2 (Merck) was transformed with the respective pET- and/or pUCP-based plasmids containing expression cassettes with laoA, laoB, and exaB. Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.6 in LB or 2-fold yeast extract-tryptone medium (2YT; 16 g/liter peptone, 10 g/liter yeast extract, 5 g/liter NaCl, pH 7.3), cooled from 37°C to 20°C, and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside. After overnight growth, cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 10 min), and pellets were stored at −80°C until further use.

For purification of LaoAB, cells were resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, and a 0.05% concentration of the nonionic detergent Nonidet P-40. Lysis was performed by rapid pressure relief (French press capillary; 20,000 lb/in2, 4°C). Cell debris was removed (25,000 × g, 40 min, 4°C), followed by sedimentation of membranes by ultracentrifugation (90 min, 140,000 × g, 4°C). Cleared lysates were subsequently filtered through a 0.45-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) syringe filter and subjected to automated column chromatography (GE Äkta Prime Plus). Strep-Tactin (IBA, Göttingen, Germany) and IMAC (GE) chromatography was performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Protein-containing fractions were pooled and concentrated by centrifugal diafiltration to 2 mg ml−1. The concentrates were centrifuged for removal of particles, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

For tandem purification of LaoAB (N-Strep-LaoA and C-His-LaoB), cell extracts were passed over a 1-ml nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) column, which was mounted directly in front of a 1-ml Strep-Tactin column. After lysate loading and an initial wash, columns were separated, and proteins were eluted according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cofactor analysis.

For LaoAB cofactor analysis, the purified protein was denatured with 4 M guanidine hydrochloride (Merck) and precipitated with 4 volumes of acetone. After centrifugation (20,000 × g, 10 min) the supernatant was transferred to a new vial, dried in vacuo, and rehydrated in water. Flavin species were identified by HPLC with mass spectrometry (MS) according to a procedure described previously (53).

Native PAGE and dehydrogenase activity.

Dehydrogenase activity was detected by in-gel activity staining as described previously (15). Alcohols were used in a saturated amount of 10 mM in 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.8), sonicated, and than incubated for several hours at 37°C and 200 rpm to emulsify the water-insoluble substrate.

Immunodetection of Strep-tagged LaoB.

Western blotting and immunodetection of recombinant proteins produced in E. coli were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using nitrocellulose membranes, monoclonal antibodies against penta-His and StrepII epitopes fused to horseradish peroxidase (IBA, Göttingen, Germany), and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Physiological localization of LaoB was analyzed in a P. aeruginosa PAO1ΔlaoB(pME6032::laoAB-Strep) strain and the respective PAO1ΔlaoB(pME6032) control. Cultures were grown as described above for growth experiments and harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 10,000 × g. Five grams of cells was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.8) and 150 mM NaCl, and suspensions were disrupted with a French press (20,000 lb/in2). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation for 30 min at 16,000 × g at 4°C. Subsequently, membranes were prepared by ultracentrifugation for 1 h at 100,000 × g at 4°C. Supernatants were collected, and membranes were emulsified in the above-mentioned buffer using a piston homogenizer. For enrichment of Strep-tagged proteins, samples of 50 mg of protein were passed through a 0.2-ml Strep-Tactin gravity flow column, which was then washed with 10 column volumes of buffer. Following elution with 50 mM biotin, protein concentrations were determined spectroscopically (1 A280 unit = 1 mg ml−1 protein). The obtained samples were then used for SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Western blots of P. aeruginosa samples were performed using PVDF membranes (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) on which the equivalent of 50 μg protein mixture per lane was transferred from a 12.5% SDS-acrylamide gel. Membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline plus 0.2% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h before a monoclonal antibody against the StrepII epitope (IBA, Göttingen, Germany) was added and incubated overnight. Following three washing steps with TBST, a secondary epitope against mouse Ig coupled to alkaline phosphatase (AP; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was applied and incubated for 2 h. Following washing steps and buffer exchange to AP buffer, immune detection was performed using a ready-to-use CDPstar substrate (Roche).

Aldehyde detection.

The aldehyde reaction product of LaoAB with 1-nonanol, nonyl aldehyde, was detected by derivatization with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) and LC-MS according to established protocols (54). Reaction mixtures and controls were mixed with 10% (vol/vol) of a 20 mM DNPH solution (in 2 M HCl) and incubated at 70°C for 30 min. Samples were subsequently centrifuged for 5 min at 20,000 × g, filtered, and analyzed with an HPLC program comprising a 25-min gradient at 0.6 ml min−1 from 50% to 95% acetonitrile (ACN) (aqueous phase was 10 mM formic acid). Chromatography was performed at 35°C, using a 150/3 mm Knauer Eurospher II 3-μm-particle-size C18 column. MS was performed with a Bruker Amazon Speed ion trap spectrometer with a flow rate of 10 μl min−1. The ion source was parameterized to a capillary voltage of 2,500 V and a capillary temperature of 200°C.

Spectroscopic assays.

Oxidase activity was assayed by release of hydrogen peroxide in the presence of typical substrates of LaoAB. H2O2 was detected by horseradish peroxidase, which oxidizes ABTS to form a stable radical, which can be detected spectroscopically at 405 nm, as described previously (30).

Quantitative measurement of alcohol dehydrogenase activity was performed using PMS as the electron mediator and DCPIP as the electron acceptor of the dehydrogenation reaction. Reduction of DCPIP, equivalent to enzyme turnover, was detected spectroscopically at 605 nm using Jasco V-550 or V-750 spectrophotometers (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan). All assays were performed in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) in the presence of 50 μM DCPIP and the respective substrates and additives. LaoAB complex and 200 μM PMS were added directly to the cuvette to start the reaction. If not otherwise stated, reactions were run at ambient temperature (22°C). When temperature dependence was assayed, reaction buffer, additives, and protein were equilibrated at the respective temperature and measurement was performed with an Evolution 200 spectrometer fitted with a cuvette holder with a Peltier thermostat (Thermo Scientific). If indicated, reactions were supplemented with various concentrations of n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside, n-nonyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, Triton X-100, Brij 58 (all Sigma-Aldrich), or rhamnolipids (extract, 95% purity; Sigma-Aldrich) from 5% stock solutions.

SDS quantification.

SDS was quantified with a modified Stains-all assay as previously described (15).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Philip Röhe and Karin Niermann for experimental support.

This work was funded by grants from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) through its Central Innovation Program for SMEs (ZIM; grant 16KNO13527 PakuNaS) and from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; grant INST 211/646-1 FUGG) to B.P.

Contributor Information

Bodo Philipp, Email: bodo.philipp@uni-muenster.de.

Maia Kivisaar, University of Tartu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clarke P. 1982. The metabolic versatility of pseudomonads. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 48:105–130. 10.1007/BF00405197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunasekera TS, Striebich RC, Mueller SS, Strobel EM, Ruiz ON. 2013. Transcriptional profiling suggests that multiple metabolic adaptations are required for effective proliferation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in jet fuel. Environ Sci Technol 47:13449–13458. 10.1021/es403163k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas OR, White GF. 1989. Metabolic pathway for the biodegradation of sodium dodecyl sulfate by Pseudomonas sp. C12B. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 11:318–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagelueken G, Adams TM, Wiehlmann L, Widow U, Kolmar H, Tümmler B, Heinz DW, Schubert W-D. 2006. The crystal structure of SdsA1, an alkylsulfatase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, defines a third class of sulfatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:7631–7636. 10.1073/pnas.0510501103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rojo F. 2009. Degradation of alkanes by bacteria. Environ Microbiol 11:2477–2490. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smits THM, Witholt B, van Beilen JB. 2003. Functional characterization of genes involved in alkane oxidation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 84:193–200. 10.1023/A:1026000622765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel-Mawgoud AM, Lépine F, Déziel E. 2010. Rhamnolipids: diversity of structures, microbial origins and roles. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 86:1323–1336. 10.1007/s00253-010-2498-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noordman WH, Janssen DB. 2002. Rhamnolipid stimulates uptake of hydrophobic compounds by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:4502–4508. 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4502-4508.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Miller RM. 1995. Effect of rhamnolipid (biosurfactant) structure on solubilization and biodegradation of n-alkanes. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:2247–2251. 10.1128/AEM.61.6.2247-2251.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klebensberger J, Lautenschlager K, Bressler D, Wingender J, Philipp B. 2007. Detergent-induced cell aggregation in subpopulations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a preadaptive survival strategy. Environ Microbiol 9:2247–2259. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Görisch H. 2003. The ethanol oxidation system and its regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim Biophys Acta 1647:98–102. 10.1016/S1570-9639(03)00066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sargent JR, Gatten RR, McIntosh R. 1977. Wax esters in the marine environment—their occurrence, formation, transformation and ultimate fates. Mar Chem 5:573–584. 10.1016/0304-4203(77)90043-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mudge S. 2005. Fatty alcohols—a review of their natural synthesis and environmental distribution. Soap and Detergent Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noweck K, Grafahrend W. 2006. Fatty alcohols, p 117–139. In Ullman F (ed), Ullmann’s encyclopedia of industrial chemistry, 6th ed. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany. 10.1002/14356007.a10_277.pub2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panasia G, Philipp B. 2018. LaoABCR, a novel system for oxidation of long-chain alcohols derived from SDS and alkane degradation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e00626-18. 10.1128/AEM.00626-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panasia G, Oetermann S, Steinbüchel A, Philipp B. 2019. Sulfate ester detergent degradation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is subject to both positive and negative regulation. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e01352-19. 10.1128/AEM.01352-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao S, Lin Z, Luo D, Ma W, Cheng Q. 2008. Cloning and characterization of long-chain fatty alcohol oxidase LjFAO1 in Lotus japonicus. Biotechnol Prog 24:773–779. 10.1021/bp0703533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gimenez MR, Chandra G, Van Overvelt P, Voulhoux R, Bleves S, Ize B. 2018. Genome wide identification and experimental validation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Tat substrates. Sci Rep 8:11950. 10.1038/s41598-018-30393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yum DY, Lee YP, Pan JG. 1997. Cloning and expression of a gene cluster encoding three subunits of membrane-bound gluconate dehydrogenase from Erwinia cypripedii ATCC 29267 in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 179:6566–6572. 10.1128/jb.179.21.6566-6572.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyama H, Furuya N, Saichana I, Ano Y, Adachi O, Matsushita K. 2007. Membrane-bound, 2-keto-D-gluconate-yielding D-gluconate dehydrogenase from “Gluconobacter dioxyacetonicus” IFO 3271: molecular properties and gene disruption. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:6551–6556. 10.1128/AEM.00493-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rupp M, Görisch H. 1988. Purification, crystallisation and characterization of quinoprotein ethanol dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 369:431–440. 10.1515/bchm3.1988.369.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klebensberger J, Birkenmaier A, Geffers R, Kjelleberg S, Philipp B. 2009. SiaA and SiaD are essential for inducing autoaggregation as a specific response to detergent stress in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol 11:3073–3086. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chattopadhyay A, Förster-Fromme K, Jendrossek D. 2010. PQQ-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase (QEDH) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is involved in catabolism of acyclic terpenes. J Basic Microbiol 50:119–124. 10.1002/jobm.200900178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wehrmann M, Billard P, Martin-Meriadec A, Zegeye A, Klebensberger J. 2017. Functional role of lanthanides in enzymatic activity and transcriptional regulation of pyrroloquinoline quinone-dependent alcohol dehydrogenases in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. mBio 8:e00570-17. 10.1128/mBio.00570-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berks BC. 1996. A common export pathway for proteins binding complex redox cofactors? Mol Microbiol 22:393–404. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dreusch A, Burgisser DM, Heizmann CW, Zumft WG. 1997. Lack of copper insertion into unprocessed cytoplasmic nitrous oxide reductase generated by an R20D substitution in the arginine consensus motif of the signal peptide. Biochim Biophys Acta 1319:311–318. 10.1016/s0005-2728(96)00174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanley NR, Palmer T, Berks BC. 2000. The twin arginine consensus motif of Tat signal peptides is involved in Sec-independent protein targeting in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 275:11591–11596. 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halbig D, Wiegert T, Blaudeck N, Freudl R, Sprenger GA. 1999. The efficient export of NADP-containing glucose-fructose oxidoreductase to the periplasm of Zymomonas mobilis depends both on an intact twin-arginine motif in the signal peptide and on the generation of a structural export signal induced by cofactor binding. Eur J Biochem 263:543–551. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sargent F, Berks BC, Palmer T. 2006. Pathfinders and trailblazers: a prokaryotic targeting system for transport of folded proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett 254:198–207. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallati H. 1979. Horseradish peroxidase: a study of the kinetics and the determination of optimal reaction conditions, using hydrogen peroxide and 2,2’-azinobis 3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) as substrates. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem 17:1–7. (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Margoliash E, Frohwirt N. 1959. Spectrum of horse-heart cytochrome c. Biochem J 71:570–572. 10.1042/bj0710570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yalkowsky SH, He Y. 2003. Handbook of aqueous solubility data. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wittgens A, Kovacic F, Müller MM, Gerlitzki M, Santiago-Schübel B, Hofmann D, Tiso T, Blank LM, Henkel M, Hausmann R, Syldatk C, Wilhelm S, Rosenau F. 2017. Novel insights into biosynthesis and uptake of rhamnolipids and their precursors. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:2865–2878. 10.1007/s00253-016-8041-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer T, Berks BC. 2012. The twin-arginine translocation (Tat) protein export pathway. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:483–496. 10.1038/nrmicro2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee H-C, Portnoff AD, Rocco MA, DeLisa MP. 2014. An engineered genetic selection for ternary protein complexes inspired by a natural three-component hitchhiker mechanism. Sci Rep 4:7570. 10.1038/srep07570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodrigue A, Chanal A, Beck K, Müller M, Wu LF. 1999. Co-translocation of a periplasmic enzyme complex by a hitchhiker mechanism through the bacterial tat pathway. J Biol Chem 274:13223–13228. 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sauvé V, Bruno S, Berks BC, Hemmings AM. 2007. The SoxYZ complex carries sulfur cycle intermediates on a peptide swinging arm. J Biol Chem 282:23194–23204. 10.1074/jbc.M701602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanley NR, Sargent F, Buchanan G, Shi J, Stewart V, Palmer T, Berks BC. 2002. Behaviour of topological marker proteins targeted to the Tat protein transport pathway. Mol Microbiol 43:1005–1021. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Auclair SM, Bhanu MK, Kendall DA. 2012. Signal peptidase I: cleaving the way to mature proteins. Protein Sci 21:13–25. 10.1002/pro.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Beilen JB, Penninga D, Witholt B. 1992. Topology of the membrane-bound alkane hydroxylase of Pseudomonas oleovorans. J Biol Chem 267:9194–92001. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)50407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin SF, Clements JH. 2013. Correlating structure and energetics in protein-ligand interactions: paradigms and paradoxes. Annu Rev Biochem 82:267–293. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060410-105819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dill KA, Truskett TM, Vlachy V, Hribar-Lee B. 2005. Modeling water, the hydrophobic effect, and ion solvation. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 34:173–199. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jarvis FG, Johnson MJ. 1949. A Glyco-lipide produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Chem Soc 71:4124–4126. 10.1021/ja01180a073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koch AK, Käppeli O, Fiechter A, Reiser J. 1991. Hydrocarbon assimilation and biosurfactant production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. J Bacteriol 173:4212–4219. 10.1128/jb.173.13.4212-4219.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Miller RM. 1994. Effect of a Pseudomonas rhamnolipid biosurfactant on cell hydrophobicity and biodegradation of octadecane. Appl Environ Microbiol 60:2101–2106. 10.1128/aem.60.6.2101-2106.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soberón-Chávez G, Lépine F, Déziel E. 2005. Production of rhamnolipids by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 68:718–725. 10.1007/s00253-005-0150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grady SL, Malfatti SA, Gunasekera TS, Dalley BK, Lyman MG, Striebich RC, Mayhew MB, Zhou CL, Ruiz ON, Dugan LC. 2017. A comprehensive multi-omics approach uncovers adaptations for growth and survival of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on n-alkanes. BMC Genomics 18:1–19. 10.1186/s12864-017-3708-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kabelitz N, Santos PM, Heipieper HJ. 2003. Effect of aliphatic alcohols on growth and degree of saturation of membrane lipids in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. FEMS Lett 220:223–227. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crone S, Vives-Flórez M, Kvich L, Saunders AM, Malone M, Nicolaisen MH, Martínez-García E, Rojas-Acosta C, Gomez-Puerto MC, Calum H, Whiteley M, Kolter R, Bjarnsholt T. 2020. The environmental occurrence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. APMIS 128:220–231. 10.1111/apm.13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harb Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klebensberger J, Rui O, Fritz E, Schink B, Philipp B. 2006. Cell aggregation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO1 as an energy-dependent stress response during growth with sodium dodecyl sulfate. Arch Microbiol 185:417–427. 10.1007/s00203-006-0111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jagmann N, Brachvogel HP, Philipp B. 2010. Parasitic growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in co-culture with the chitinolytic bacterium Aeromonas hydrophila. Env Microbiol 12:1787–1802. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drees SL, Ernst S, Belviso BD, Jagmann N, Hennecke U, Fetzner S. 2018. PqsL uses reduced flavin to produce 2-hydroxylaminobenzoylacetate, a preferred PqsBC substrate in alkyl quinolone biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem 293:9345–9357.51. 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stafiej A, Pyrzynska K, Ranz A, Lankmayr E. 2006. Screening and optimization of derivatization in heating block for the determination of aliphatic aldehydes by HPLC. J Biochem Biophys Methods 69:15–24. 10.1016/j.jbbm.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thoma S, Schobert M. 2009. An improved Escherichia coli donor strain for diparental mating. FEMS Microbiol Lett 294:127–132. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77–86. 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.West SE, Schweizer HP, Dall C, Sample AK, Runyen-Janecky LJ. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 148:81–86. 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heeb S, Blumer C, Haas D. 2002. Regulatory RNA as mediator in GacA/RsmA-dependent global control of exoproduct formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. J Bacteriol 184:1046–1056. 10.1128/jb.184.4.1046-1056.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Völlmecke C, Kötting C, Gerwert K, Lübben M. 2009. Spectroscopic investigation of the reaction mechanism of CopB-B, the catalytic fragment from an archaeal thermophilic ATP-driven heavy metal transporter. FEBS J 276:6172–6186. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]