Abstract

FOS, a subunit of the activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor, has been implicated in various cellular changes. In the human ovary, the expression of FOS and its heterodimeric binding partners JUN, JUNB, and JUND increases in periovulatory follicles. However, the specific role of the FOS/AP-1 remains elusive. The present study determined the regulatory mechanisms driving the expression of FOS and its partners and functions of FOS using primary human granulosa/lutein cells (hGLCs). Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) induced a biphasic increase in the expression of FOS, peaking at 1 to 3 hours and 12 hours. The levels of JUN proteins were also increased by hCG, with varying expression patterns. Coimmunoprecipitation analyses revealed that FOS is present as heterodimers with all JUN proteins. hCG immediately activated protein kinase A and p42/44MAPK signaling pathways, and inhibitors for these pathways abolished hCG-induced increases in the levels of FOS, JUN, and JUNB. To identify the genes regulated by FOS, high-throughput RNA sequencing was performed using hGLC treated with hCG ± T-5224 (FOS inhibitor). Sequencing data analysis revealed that FOS inhibition affects the expression of numerous genes, including a cluster of genes involved in the periovulatory process such as matrix remodeling, prostaglandin synthesis, glycolysis, and cholesterol biosynthesis. Quantitative PCR analysis verified hCG-induced, T-5224-regulated expression of a selection of genes involved in these processes. Consistently, hCG-induced increases in metabolic activities and cholesterol levels were suppressed by T-5224. This study unveiled potential downstream target genes of and a role for the FOS/AP-1 complex in metabolic changes and cholesterol biosynthesis in granulosa/lutein cells of human periovulatory follicles.

Keywords: FOS, JUN proteins, granulosa cells, ovulation, human

In response to the midcycle LH surge, the preovulatory follicles in the ovary undergo dramatic metabolic, hormonal, and structural changes required for ovulation and luteal transformation (reviewed in Duffy et al. (1)). To elicit these dynamic and essential periovulatory changes, LH-bound LHCGR triggers the activation of a cascade of multiple intracellular signaling cascades, which leads to the induction and activation of specific transcription factors (reviewed in Duffy et al. (1)). Notably, the transcription factors induced by the LH surge in dominant follicles have been shown to act as critical LH/LHCGR-downstream mediators necessary for successful ovulation and luteal formation. These transcription factors directly regulate the expression of a diverse array of genes that act on preovulatory follicles to bring about periovulatory changes. Such transcription factors include CCAAT enhancer-binding proteins, hypoxia-inducible factors, Runt-related transcription factors, and nuclear progesterone receptor (2–5). We have recently identified the induction of another group of transcription factors, FOS, and its heterodimeric binding partners JUN, JUNB, and JUND in periovulatory follicles obtained from normally cycling women after human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) administration (6).

FOS and JUN family proteins are members of the basic leucine zipper superfamily of transcription factors that binds target DNA duplex sites as homodimer or heterodimers (7,8). FOS typically heterodimerizes with JUN family proteins, forming a heterodimeric complex such as FOS/JUN, FOS/JUNB, and FOS/JUND (9). On the other hand, JUN family proteins can also form both homo- and heterodimers with each other (eg, JUN/JUN, JUN/JUNB, JUN/JUND) (9,10). However, FOS/JUN protein complexes are more stable and have stronger DNA-binding activity than the JUN/JUN complex (11). These complexes belong to the large family of dimeric transcription factors, called activating protein-1 (AP-1) that binds to a palindromic DNA motif (5′-TGA G/C TCA-3′) on their target genes (12). FOS and JUNs have been known as immediate-early genes because their expression or activity was transiently and rapidly induced, often within 15 minutes to 1 hour by a variety of extracellular stimuli, such as growth factors, hormones, cytokines, neurotransmitters, and oncogenic stimuli in various tissues (reviewed in (13,14)). Additionally, protein kinases A (PKA) and C and MAPKs have shown to increase the activity of FOS and JUN by posttranscriptional phosphorylation in various types of cells (15,16). The FOS/AP-1 transcription factor has shown to be involved in various cellular events, such as proliferation, differentiation, survival, metabolism, hypoxia, angiogenesis, steroidogenesis, and prostaglandin production (17–19). These events are also essential processes for normal ovarian functions, including follicular development, ovulation, and luteinization (20,21). Indeed, our previous study showed that FOS is involved in hCG-induced prostaglandin production in human granulosa cells (6). In Fos null mice, the follicular development was arrested at the secondary follicle stage; the ovaries were devoid of antral follicles and corpora lutea (CL) (22). Although this phenotype was explained by reduced levels of FSH and LH release from the pituitary (22), this study also described that Fos null mice failed to ovulate and form CL even when exogenous gonadotropin was administered. These findings indicated that the ovarian expression of Fos was necessary for successful ovulation and CL formation in mice. Despite the evidence showing the increases in the expression of FOS and JUN family proteins in human ovulatory follicles and the functional significance of these transcription factors in the periovulatory process, little is known about regulatory mechanisms by which the LH surge increases the expression of these transcription factors and their specific roles in human ovulatory follicles.

In the present study, we sought out to determine whether the expression of FOS and/or JUN family proteins is induced or activated in response to hCG in a time-specific manner and whether these increases are mediated by specific signaling pathways in human periovulatory granulosa cells. We also tested the hypothesis that the increased FOS/AP-1 complex regulates the expression of diverse genes that are involved in the periovulatory process by identifying downstream genes of FOS/AP-1 in human granulosa cells. Last, we assessed the potential impact of this transcription factor on specific aspects of metabolic changes occurring in granulosa cells of human periovulatory follicles.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Unless otherwise noted, all reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. or Thermo Fisher Scientific. Human chorionic gonadotropin was reconstituted in 1× PBS. T-5224 was purchased from ApexBio Technology and reconstituted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). H89 and SCH772984 were purchased from Cayman Chemical and reconstituted in 1× PBS.

Human granulosa/lutein cell cultures

Human granulosa/lutein cells (hGLCs) were obtained from follicular aspirates of women undergoing the standardized in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedure. To avoid any potential compounding impacts of reproductive etiologies, samples from patients diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome and endometriosis were not used. The collection protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Kentucky Office of Research Integrity. Ovarian hyperstimulation was induced by the administration of recombinant human FSH in individualized doses to patients at the Bluegrass Fertility Center (Lexington, KY). IVF patients were then administered with hCG (10 000U) on days 9 to 11, and dominant follicles were aspirated 36 hours later. The experiments with hGLC were carried out as described previously (23,24). Briefly, immediately after retrieval of cumulus-oocyte complexes, the remaining cells in aspirates were subjected to Percoll gradient centrifugations to remove red blood cells. The isolated cells were first examined under the microscope for their morphology and counted. If the cells isolated were of poor quality and insufficient numbers, these cells were discarded. Only the cells with normal morphology were then resuspended with OptiMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotic-antimycotic and then seeded onto culture plates (2.5 × 105 cells/mL). The cells were acclimatized for 6 days, changing media every 24 hours. At the end of acclimation, the hGLCs were treated with or without various reagents ± hCG (1 IU/mL) in OptiMEM media supplemented with antibiotic-antimycotic and further cultured for stated hours. When reagents were dissolved in DMSO, the same concentration of DMSO were added to medium for the control cells. The final concentration of DMSO was <0.2%.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from granulosa cells using an RNeasy mini kit. The synthesis of the first-strand cDNA was performed by reverse transcription of 500 ng total RNA using superscript III with Oligo(dT)20 primer. The levels of mRNA for genes examined were measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using Brilliant 3 Ultra-Fast SYBR green (Stratagene). Oligonucleotide primers corresponding to each gene were designed using Primer3 software (Supplementary Table 1 (23)). The relative abundance of the target transcript was normalized to RNA18S5 as previously described (24,25) and calculated according to the 2-ΔΔCT method (26).

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell lysates were isolated from cultured cells, denatured, run on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane as previously described (6,24). The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C in 5% skim milk or BSA/Tris-buffered saline including 0.1% Tween-20 solution containing primary antibodies against FOS, JUN, JUNB, JUND, phosphorylated AKT (pAKT), phosphorylated CREB (pCREB), pERK1/2, p-p38MAPK (Cell Signaling Technology), or ACTB (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) (Supplementary Table 2 (23)). The blots were incubated with the respective secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody for 1 hour. Peroxidase activity was visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce Chemical).

Coimmunoprecipitation

Nuclear extracts were isolated from cultured cells as described in manufacturer’s instruction (Active Motif). Because phosphorylation regulates the activity of AP-1 proteins (27–29), a primary antibody against pFOS (Cell Signaling Technology; Supplementary Table 2 (23)) was selected to identify partners for functionally active FOS protein in hGLC. The nuclear extracts were incubated with anti-pFOS antibody overnight at 4°C, and then the protein A agarose/Salmon Sperm DNA (MilliporeSigma) was added and incubated for an hour. After at least 5-time repeats of centrifugation and rinse, samples were subjected to Western blot analyses using antibodies against JUN, JUNB, or JUND (Cell Signaling Technology) as mentioned previously.

cDNA library construction, RNA sequencing, and differential expression analysis

Primary hGLCs obtained from 4 IVF patients were treated with hCG (1 IU/mL) or hCG + T-5224 (20 µM (6), specific FOS inhibitor (30)). Total RNA was extracted from hGLCs using a RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN), treated with deoxyribonuclease I and run on a 1% agarose gel to verify its integrity. Library construction and RNA sequencing were conducted by the DNA service division of the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center at the University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign, IL). Briefly, the strand-specific RNA sequencing libraries for 8 individual samples were prepared using a TruSeq Stranded RNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina). These samples represent 4 independent experiments for each of the 2 conditions examined. Libraries were pooled in equimolar concentration, and the pool was quantitated by qPCR and sequenced on 3 lanes for 101 cycles on a HiSeq2500 (Illumina) using a HiSeq SBS sequencing kit version 2. The sequencing produced more than 166 million signaling reads of excellent quality. Fastq files were generated and demultiplexed with the bcl2fast1 v1.8.4 Conversion Software (Illumina). Adaptor sequences were trimmed from raw RNA sequencing reads. Trimmomatic (version 0.33) was used to trim any residual adapter content and low-quality bases, and trimmed data were qualified on the trimmed FASTQ files using FASTQC (version 0.11.4) software. Each set of RNA sequencing reads was aligned with the National Center for Biotechnology Information annotation of the human genome reference sequence (GRCh38.p6_genomic.fna) using the alignment software, STAR (version 2.5.0a). All gene counts were generated using featureCounts in the subread (version 1.5.0) package. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data were analyzed in R (version 3.3.1) packages as described in the following section. Briefly, the number of reads per genes was normalized using the trimmed mean of M-values normalization method in the edgeR package (version 3.15.0). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed for the clustering of the samples to determine whether there were overall treatment differences or batch effects. Next, statistical analysis was applied to the 13 539 genes left after filtering and performed to determine differential expression between the treatments using edgeR (version 3.15.0). A P value was adjusted a q value by the false discovery rate. The threshold for the significant differential expression was defined as a value of q < 0.01. RNA-seq data have been deposited in a National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number (GSE166443).

MTS assay

The cell metabolic activity was measured using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution MTS assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). Briefly, the cells cultured in 96-well plates were treated with or without hCG in the presence or absence of T-5224 (20 µM) for 24 hours. At the end of culture, 20 µL of MTS reagent was pipetted into each well and then further incubated for an additional 1 hour. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm in the Infinite F200 plate reader (Tecan USA) to determine the formazan concentration.

Seahorse glycolysis stress test and cell counting

Cellular glycolysis was monitored by the Seahorse XF Glycolysis Stress Test Kit (Agilent). The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cellular glycolysis activity was measured as the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) reached by a given cell after the addition of saturating amounts of glucose (10 mM). Once the Seahorse analysis was completed, an injection of membrane-permeable Hoechst 33 342 stained cell nuclei in situ. The fluorescently labeled nuclei were imaged and counted to measure cell numbers. Data were analyzed using the wave software (Agilent) and normalized using the number of cells in each well.

Lipid extraction and cholesterol measurement

Cholesterol in cell lysates was extracted using the methodology previously described by Folch et al. (31). Briefly, the cells collected at the end of cultures were mixed in 20 volumes of chloroform:methanol (2:1) solution and agitated for 15 minutes in an orbital shaker. The homogenate was washed with 0.2 volume of 0.9% NaCl and then centrifuged to divide aqueous and organic phases. The organic phase was collected and evaporated under a nitrogen stream. Extracted cholesterol was measured using a Cholesterol Fluorometric Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman). Extracts were added into 96-well plates and mixed with the reagents, including assay buffer, cholesterol detector, horseradish peroxidase, cholesterol oxidase, and cholesterol esterase. After incubation at 37ºC for 30 minutes, the fluorescence was read using excitation wavelength at 535 nm and emission wavelength at 590 nm.

Hormone assay

The concentration of progesterone was measured using an Immulite kit as described previously (24). Assay sensitivity for the Immulite was 0.02 ng/mL. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 7% and 12%, respectively.

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Sample values were tested for homogeneity of variance by Levene test, and log transformations were performed when appropriate. One- or 2-way ANOVA or paired t test was used to test differences in levels of mRNA, protein, MTS, ECAR, and cholesterol across time of culture or among treatments as appropriate. If the test revealed significant effects, the means were compared by Duncan test, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

The effect of hCG on the expression of FOS and its binding partners

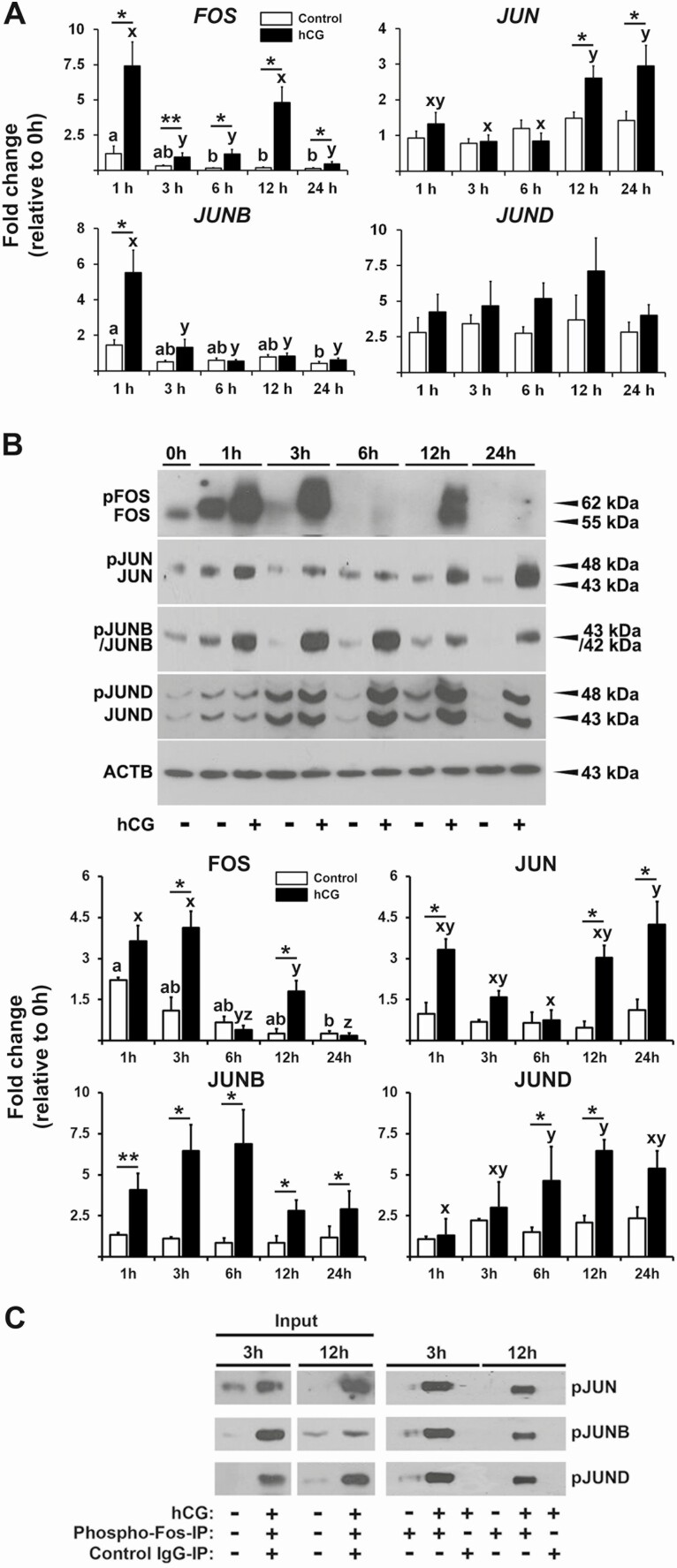

To determine whether hCG regulates the expression of FOS, JUN, JUNB, and JUND in human granulosa cells in a time-dependent manner, hGLCs were treated with or without hCG (1 IU/mL) and cultured for 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours. To determine whether hCG regulates the expression of FOS, JUN, JUNB, and JUND in human granulosa cells in a time-dependent manner, hGLCs were treated with or without hCG (1 IU/mL) and cultured for 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hours. As shown in Fig. 1A, hCG increased the levels of mRNA for FOS within 1 hour, but this increase quickly declined by 3 hours until rising again at 12 hours post-hCG. These biphasic and transient increases in mRNA levels were recapitulated in the profile of protein levels: the levels peaked at 1 through 3 hours and then again at 12 hours after hCG treatment (Fig. 1B). Among Jun proteins, only JUNB mRNA level showed a transient and immediate increase at 1 hour post-hCG with a corresponding increase in protein levels at the sample time point (Fig. 1A and 2B). However, unlike FOS, the maximal accumulation of JUNB protein was detected at 6 hours post-hCG, and the hCG-induced increase was sustained throughout the culture period (Fig. 1B). hCG also increased JUN expression, displaying unique U-shaped changes by hCG: an increase in protein levels at 1 hour and a rapid decline by 3 hours until a second rise at 12 hours, which continued to 24 hours post-hCG. For JUND, mRNA levels did not match with protein levels: hCG showed no effect on the levels of mRNA, whereas protein levels were increased by hCG at 6 and 12 h (Fig. 1A and 1B).

Figure 1.

The effect of hCG on the expression of FOS and Jun family members. Human granulosa/lutein cells (hGLCs) obtained from women undergoing a standardized IVF procedure were acclimated for 6 days and then cultured without (control) or with hCG (1 IU/mL) for 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, or 24 hours. (A) The levels of mRNA for FOS and Jun family members were measured by qPCR and normalized to the levels of RNA18S5 in each sample (n ≥ 4 independent experiments). (B) Representative Western blot images detecting FOS, JUN, JUNB, and JUND proteins (intact and phosphorylated forms). The levels of ACTB in each lane were used as a loading control. The band intensities for each protein were measured by ImageJ and normalized to the intensity of ACTB in the corresponding sample. The experiments were repeated at least three times with independent samples. (C) Nuclear extracts were immunoprecipitated with a phosphorylated FOS antibody (3 µg/mL) or normal rabbit IgG (3 µg/mL), and protein-antibody complexes were separately detected by Western blot analyses using antibodies for JUN, JUNB, or JUND. Bars with no common superscripts within each treatment group and (*) between treatments are significantly different (P < 0.05). **P = 0.052.

Figure 2.

The effect of hCG on intracellular signaling pathways. Primary hGLCs were cultured with or without hCG (1 IU/mL) for 0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 3 hours. (A) Western blot analyses were performed to measure the levels of protein for phosphorylated (p)CREB, pERK1/2, pAKT, and p-p38MAPK. The levels of ACTB protein were used as a loading control. (B) The band intensities for each protein were measured by ImageJ and normalized to the intensity of ACTB in the corresponding sample. The experiments were repeated at least 3 times with independent samples. Bars with no common superscripts within each treatment group and (*) between treatments are significantly different (P < 0.05). **P = 0.084; ***P = 0.07.

With the data showing time-specific increases in FOS and Jun family proteins by hCG, we assessed whether FOS heterodimerizes preferentially with specific Jun proteins. As shown in Fig. 1C, all Jun proteins were detected in pFOS antibody-isolated precipitates in the presence of hCG at 3 and 12 hours. This result indicated that all 3 forms of the FOS/AP-1 complex (eg, FOS/JUN, FOS/JUNB, FOS/JUND) were present in hGLCs.

hCG-activated intracellular signaling pathways involved in the expression of FOS and Jun family members

Binding of LH/hCG to its receptor, LHCGR, on the surface of granulosa cells is followed by the immediate activation of various intracellular signaling pathways. To identify which intracellular signaling pathway(s) is involved in the expression of hCG-induced FOS and Jun proteins in human granulosa cells, we first assessed changes in the levels of several signaling elements known to be activated by hCG in other systems (32,33). hCG rapidly increased the levels of pCREB (a final effector activated by the PKA signaling pathway) within 30 minutes, and this increase was attenuated by 3 hours (Fig. 2A and 2B). Upregulation of pERK1/2 (elements of the p42/44MAPK signaling pathway) by hCG was detected as early as 30 minutes and sustained up to 3 hours with a slight decrease (Fig. 2A and 2B). No significant change was detected in the levels of pAKT (a component of the PI3K signaling pathway) and p-p38MAPK (Fig. 2A and 2B) by hCG at least during the first 3 hours.

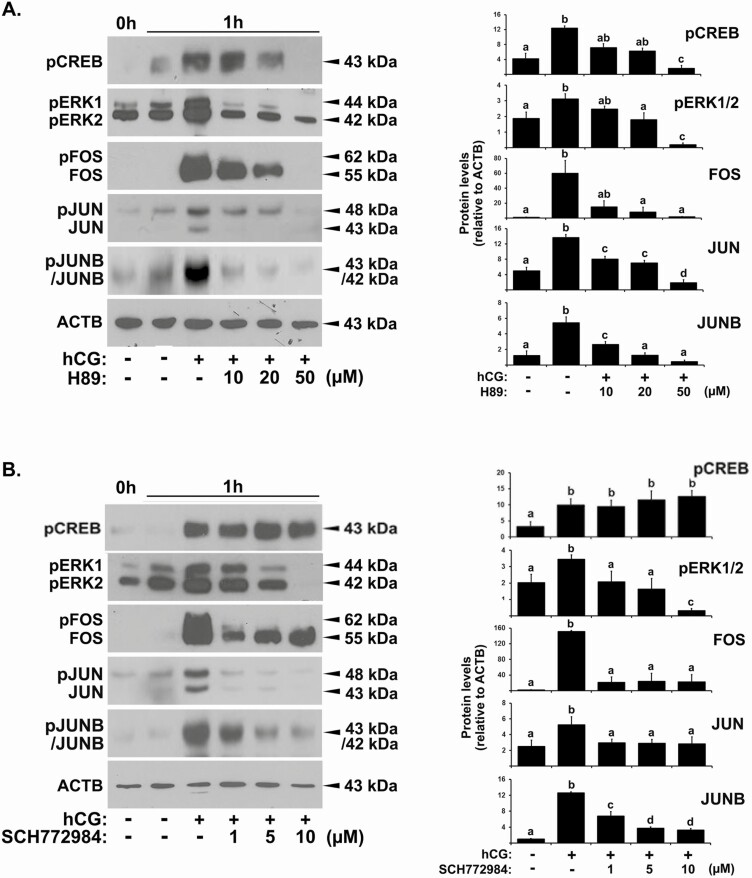

Given the immediate increases in pCREB and pERK1/2 levels by hCG, we examined whether PKA and MAPK signaling pathways were involved in the expression of hCG-stimulated FOS, JUN, and JUNB. Downregulation of pCREB levels by H89, an inhibitor of the PKA signaling pathway, was accompanied by a complete reduction of hCG-increased pERK1/2, FOS, JUN, and JUNB proteins at 1 hour post-hCG (Fig. 3A). Similarly, SCH772984, an inhibitor of the p42/44MAPK signaling pathway, reduced hCG-induced increases in the level of pERK1/2, FOS, JUN, and JUNB proteins but showed no effect on pCREB protein levels (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

The effect of blocking either the PKA or the MAPK signaling pathway on the expression of protein for FOS and Jun family members. Primary hGLCs were cultured without or with (A) hCG (1 IU/mL) ± H89 (an inhibitor of the PKA signaling pathway) or (B) hCG (1 IU/mL) ± SCH772984 (an inhibitor of the MAPK signaling pathway) for 1 hour. Representative Western blot images showed phosphorylated (p)CREB, pERK1/2, FOS, JUN, and JUNB proteins. ACTB in each lane was used as a loading control. Densitometric analyses were performed by ImageJ to measure the band intensities for each protein. Protein band intensities were normalized to the intensity of ACTB in the corresponding sample. The experiments were repeated at least 3 times with independent samples. Bars with no common superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

The effect of blocking the FOS/AP-1’s action on granulosa cell gene expression

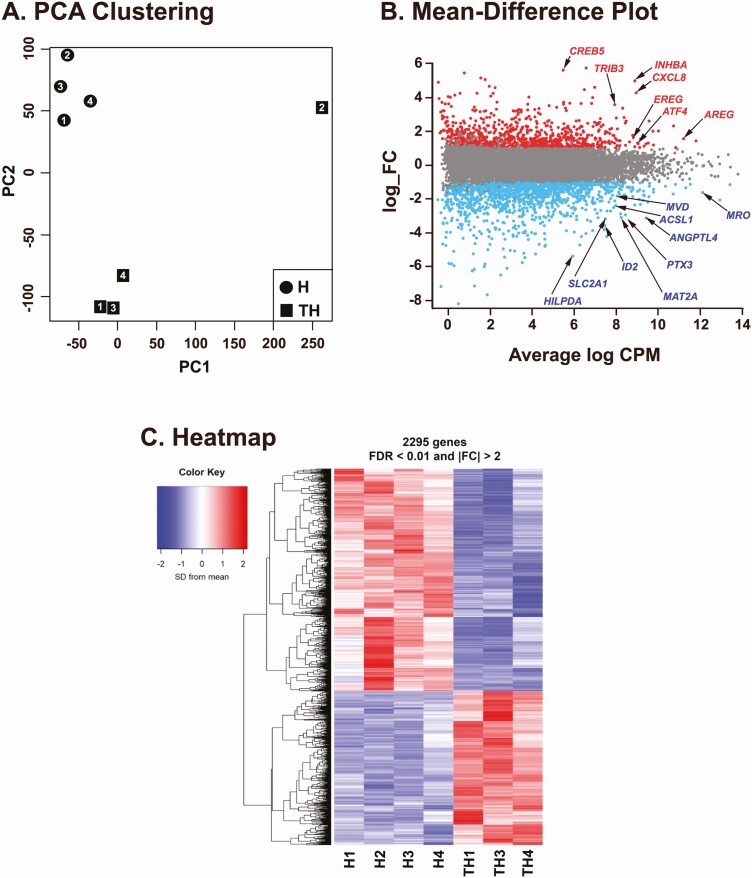

To determine the function of FOS/AP-1 in human granulosa cells, primary hGLCs were treated with hCG (1 IU/mL) in the absence or presence of T-5224 (20 µM, FOS inhibitor) and cultured for 12 hours. Total RNA samples isolated from 2 treatment groups (hCG, H; hCG+T-5224, TH) were subjected to RNA-seq (n = 4 individual IVF patients/treatment). The complete dataset was submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession GSE166443). PCA was performed after normalizing to the number of reads per million of the effective library sizes (trimmed mean of M-value normalization). It showed differences between treatments H and TH on PCA and revealed 1 outlier (eg, TH2, the number represents individual patient; Fig. 4A). Thus, the outlier was excluded for subsequent analyses. After filtering genes with no/low expression, 13 539 genes were subjected to differential expression analysis. With selection criteria logCPM > 3, false discovery rate < 0.01, and |fold change| > 2 in TH- vs H-treated cells, a total of 1311 genes were listed to be differentially expressed between 2 treatments (Supplementary Table 3 (23)). Of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), 799 and 512 genes were lower and higher, respectively, in TH- compared with H-treated hGLCs (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Table 3 (23)). A heatmap showed similarity and repeatability in the gene expression of each treatment group and stark differences between treatments (Fig. 4C). To narrow the list of potential target genes of the FOS/AP-1, we decided to focus on genes that are highly upregulated in granulosa cells of periovulatory follicles in vivo. The list of our DEGs was checked against the published dataset that reported a list of genes upregulated after hCG administration in granulosa cells collected at the time of IVF procedures compared with the cells collected before hCG (Supplementary Table III in (34)). A total of 93 DEGs in our RNA-seq data was found to be upregulated after hCG administration in the microarray dataset (34). Among them, 68 and 25 genes were downregulated and upregulated by T-5224, respectively, and listed in Table 1. To further determine whether these genes were upregulated by hCG in our hGLC model and to verify the effect of T-5224, the cells were treated with or without hCG (1 IU/mL) ± T-5224 (20 µM) for 12 hours. Among the most highly downregulated genes by T-5224 were included CD24, HAS2, RASD1, ID2, CRISPLD2, FGF12, FKBP5, PTX3, and ARHGAP20. As shown in Fig. 5, hCG markedly increased the levels of mRNA for these genes, but their hCG-induced increases were reduced by the addition of T-5224, a specific FOS inhibitor.

Figure 4.

RNA-seq analyses using hGLCs treated with hCG or hCG+T-5224. High-throughput RNA-seq analysis was performed using hGLCs obtained from 4 patients (the numbers 1-4 represent individual patient). The cells were cultured with hCG (I IU/mL, H) or hCG+T-5224 (20 μM, TH) for 12 hours. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) clustering was conducted after normalization to determine whether there are overall treatment differences or batch effects. (B) Mean-difference (MD) plot displays gene-wise log2-fold changes (log_FCs) against average expression values together with a plot of sample expression. Dots in red, gray, and blue mean genes that show increases, no changes, or decreases in expression values by the addition of T-5224, respectively. Arrows point to an array of genes that are increased or decreased by T-5224. (C) Heatmap indicates the group difference of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between H- and TH-treated hGLCs and the repeatability within each group. Thresholds used in MD plot and heatmap were FDR < 0.01 and |log_FC| > 1 to select DEGs in between groups.

Table 1.

Representative genes up-regulated by hCG and changed by T-5224

| Entrez identification | Symbol | Gene name | Fold-change by T-5224 | Fold-change by hCG in vivo (34) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100133941 | CD24 | CD24 molecule | -44.3 | 80.1 |

| 3037 | HAS2 | Hyaluronan synthase 2 | -33.8 | 10.8 |

| 51655 | RASD1 | RAS, dexamethasone-induced 1 | -16.6 | 4.5 |

| 8600 | TNFSF11 | Tumor necrosis factor superfamily member 11 | -16.2 | 6.5 |

| 3398 | ID2 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 2, HLH protein | -11.8 | 5.4 |

| 83716 | CRISPLD2 | Cysteine rich secretory protein LCCL domain containing 2 | -10.5 | 10.3 |

| 2152 | F3 | Coagulation factor III, tissue factor | -10 | 4.5 |

| 2257 | FGF12 | Fibroblast growth factor 12 | -8.6 | 6.4 |

| 117178 | SSX2IP | Synovial sarcoma, X breakpoint 2 interacting protein | -8.1 | 6.2 |

| 2289 | FKBP5 | FK506 binding protein 5 | -7.6 | 11.3 |

| 627 | BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor | -7.6 | 4.1 |

| 5806 | PTX3 | Pentraxin 3 | -7.4 | 15.6 |

| 57569 | ARHGAP20 | Rho GTPase activating protein 20 | -7.2 | 8.1 |

| 147040 | KCTD11 | Potassium channel tetramerization domain containing 11 | -6.8 | 2.5 |

| 202 | AIM1 | Absent in melanoma 1 | -6.2 | 18.5 |

| 54674 | LRRN3 | Leucine rich repeat neuronal 3 | -5.6 | 9.3 |

| 5638 | PRRG1 | Proline rich Gla (G-carboxyglutamic acid) 1 | -5.4 | 8.9 |

| 395 | ARHGAP6 | Rho GTPase activating protein 6 | -5.3 | 4.7 |

| 2180 | ACSL1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 1 | -5.3 | 7.9 |

| 6594 | SMARCA1 | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 1 | -5 | 2.9 |

| 55907 | CMAS | Cytidine monophosphate N-acetylneuraminic acid synthetase | -4.6 | 4.7 |

| 55696 | RBM22 | RNA binding motif protein 22 | -4.5 | 3.6 |

| 57713 | SFMBT2 | Scm-like with four mbt domains 2 | -4.5 | 2.1 |

| 56999 | ADAMTS9 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 9 | -4.4 | 20.8 |

| 6578 | SLCO2A1 | Solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 2A1 | -4.3 | 27.2 |

| 7145 | TNS1 | Tensin 1 | -4.2 | 3.2 |

| 64840 | PORCN | Porcupine homolog (Drosophila) | -4 | 7.8 |

| 29995 | LMCD1 | LIM and cysteine rich domains 1 | -4 | 5.8 |

| 7980 | TFPI2 | Tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 | -4 | 19.4 |

| 9510 | ADAMTS1 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 1 | -3.9 | 20.6 |

| 84187 | TMEM164 | Transmembrane protein 164 | -3.8 | 4.7 |

| 23635 | SSBP2 | Single-stranded DNA binding protein 2 | -3.8 | 6.9 |

| 210 | ALAD | Aminolevulinate dehydratase | -3.8 | 4.2 |

| 1368 | CPM | Carboxypeptidase M | -3.8 | 11 |

| 5127 | CDK16 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 16 | -3.4 | 2.8 |

| 9727 | RAB11FIP3 | RAB11 family interacting protein 3 (class II) | -3.4 | 2.3 |

| 4616 | GADD45B | Growth arrest and DNA damage inducible beta | -3.3 | 5.5 |

| 9124 | PDLIM1 | PDZ and LIM domain 1 | -3.2 | 12.2 |

| 861 | RUNX1 | Runt related transcription factor 1 | -3.1 | 3.2 |

| 1432 | MAPK14 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | -3.1 | 3.4 |

| 2185 | PTK2B | Protein tyrosine kinase 2 beta | -3 | 2.6 |

| 50506 | DUOX2 | Dual oxidase 2 | -2.9 | 7.3 |

| 7360 | UGP2 | UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2 | -2.9 | 3.1 |

| 56255 | TMX4 | Thioredoxin related transmembrane protein 4 | -2.8 | 2.7 |

| 5552 | SRGN | Serglycin | -2.8 | 10.3 |

| 166336 | PRICKLE2 | Prickle planar cell polarity protein 2 | -2.7 | 3.5 |

| 25841 | ABTB2 | Ankyrin repeat and BTB domain containing 2 | -2.7 | 4.2 |

| 54566 | EPB41L4B | Erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1 like 4B | -2.5 | 3.3 |

| 8450 | CUL4B | Cullin 4B | -2.5 | 4.8 |

| 5997 | RGS2 | Regulator of G-protein signaling 2 | -2.5 | 7.8 |

| 84923 | FAM104A | Family with sequence similarity 104 member A | -2.5 | 3 |

| 23768 | FLRT2 | Fibronectin leucine rich transmembrane protein 2 | -2.4 | 21.8 |

| 131870 | NUDT16 | Nudix hydrolase 16 | -2.4 | 2.4 |

| 2997 | GYS1 | Glycogen synthase 1 | -2.4 | 2.3 |

| 10371 | SEMA3A | Semaphorin 3A | -2.4 | 13.6 |

| 8237 | USP11 | Ubiquitin specific peptidase 11 | -2.2 | 2.1 |

| 51440 | HPCAL4 | Hippocalcin like 4 | -2.2 | 6.8 |

| 5825 | ABCD3 | ATP binding cassette subfamily D member 3 | -2.2 | 2.3 |

| 9536 | PTGES | Prostaglandin E synthase | -2.2 | 3.6 |

| 23303 | KIF13B | Kinesin family member 13B | -2.2 | 6.7 |

| 9467 | SH3BP5 | SH3-domain binding protein 5 | -2.2 | 2.5 |

| 55198 | APPL2 | Adaptor protein, phosphotyrosine interaction, PH domain and leucine zipper containing 2 | -2.2 | 2.7 |

| 154810 | AMOTL1 | Angiomotin like 1 | -2.1 | 8.4 |

| 54521 | WDR44 | WD repeat domain 44 | -2.1 | 4.2 |

| 5613 | PRKX | Protein kinase, X-linked | -2.1 | 13.5 |

| 23097 | CDK19 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 19 | -2 | 2.5 |

| 2947 | GSTM3 | Glutathione S-transferase mu 3 (brain) | -2 | 6.9 |

| 10529 | NEBL | Nebulette | -2 | 3.2 |

| 837 | CASP4 | Caspase 4 | 2 | 2.2 |

| 3725 | JUN | Jun proto-oncogene | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| 26151 | NAT9 | N-acetyltransferase 9 (putative) | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| 10346 | TRIM22 | Tripartite motif containing 22 | 2.2 | 5.8 |

| 7439 | BEST1 | Bestrophin 1 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| 84919 | PPP1R15B | Protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 15B | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| 11259 | FILIP1L | Filamin A interacting protein 1-like | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| 3428 | IFI16 | Interferon, gamma-inducible protein 16 | 2.5 | 4.3 |

| 10221 | TRIB1 | Tribbles pseudokinase 1 | 2.6 | 3.9 |

| 158219 | TTC39B | Tetratricopeptide repeat domain 39B | 2.7 | 2.4 |

| 8660 | IRS2 | Insulin receptor substrate 2 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| 9462 | RASAL2 | RAS protein activator like 2 | 2.9 | 2.6 |

| 9021 | SOCS3 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| 374 | AREG | Amphiregulin | 2.9 | 21.6 |

| 65059 | RAPH1 | Ras association (RalGDS/AF-6) and pleckstrin homology domains 1 | 3 | 3.2 |

| 5743 | PTGS2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | 3.2 | 13.4 |

| 80315 | CPEB4 | Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 4 | 3.7 | 5.8 |

| 5784 | PTPN14 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 14 | 3.9 | 2.4 |

| 22822 | PHLDA1 | Pleckstrin homology like domain family A member 1 | 4.1 | 6.9 |

| 1958 | EGR1 | Early growth response 1 | 4.3 | 5.5 |

| 116496 | FAM129A | Family with sequence similarity 129 member A | 4.7 | 3.2 |

| 84159 | ARID5B | AT-rich interaction domain 5B | 4.9 | 4.1 |

| 27242 | TNFRSF21 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 21 | 5 | 3.1 |

| 1848 | DUSP6 | Dual specificity phosphatase 6 | 5.4 | 8.5 |

| 9975 | NR1D2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 2 | 12.7 | 2 |

Selection criteria for DEGs: log2CPM > 3, FDR < 0.01, and |fold change| > 2 in hCG+T-5224 compared with hCG-treated hGLCs. Fold changes were calculated by comparing the average values for hCG-treated sample vs hCG +T-5224 treated sample. Lower expression in hCG+T-5224 is given as -2 rather than 0.5. The list of genes met the selection criteria (1311 genes) were then surveyed for hCG-inducibility by screening the list of genes that were previously identified to be up-regulated by hCG in granulosa cells during the ovulatory period in vivo (32). Only the genes that were up-regulated by hCG and down-regulated by T-5224 are listed in Table 1.

DEG, differentially expressed gene; FDR, false discovery rate; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin.

Figure 5.

Validation of RNA-seq data by qPCR analysis. Most highly downregulated genes (9 genes) were selected from the list of DEGs by hCG+T-5224 treatment compared with hCG in hGLCs. The cells were cultured without (control) or with hCG (1 IU/mL) ± T-5224 (20 µM) for 12 hours. qPCR analysis was performed to measure the levels of mRNA for 9 selected DEGs. The levels of mRNA for each gene were normalized to the levels of RNA18S5 in each sample (n = 5-6 independent batches). Bars with no common superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

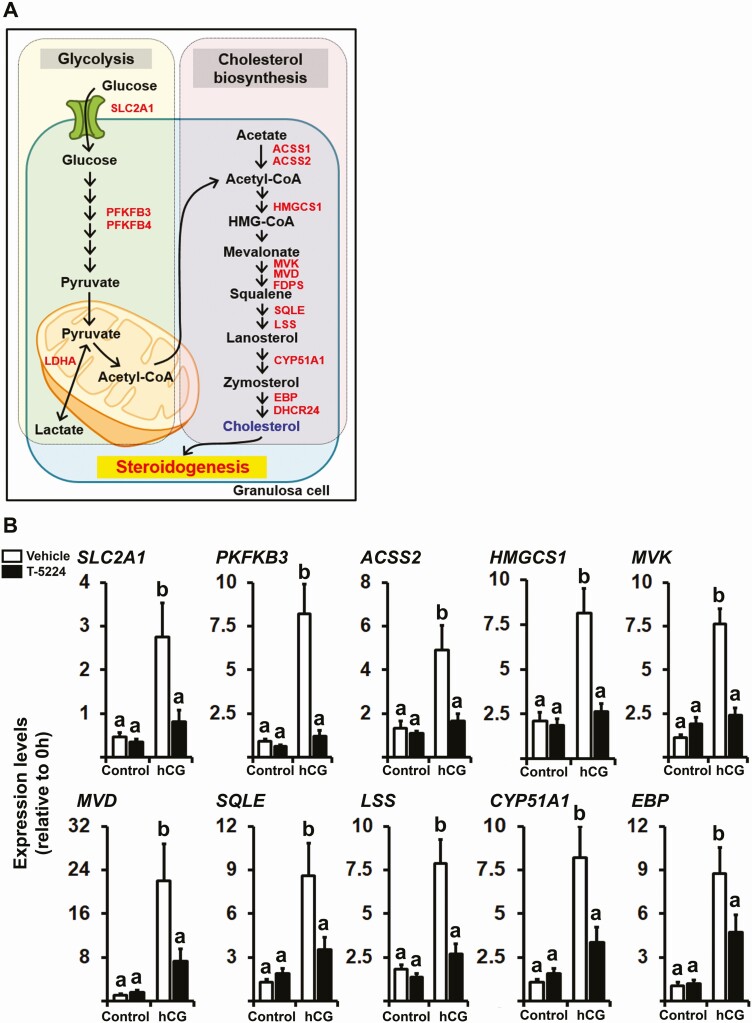

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes mapping of T-5224- downregulated DEGs in glycolysis and cholesterol de novo biosynthesis pathways

To determine whether the FOS/AP-1-mediated expression of specific genes affects certain pathways or functions in ovulatory follicles, the list of downregulated DEGs (799 genes) was subjected to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) mapping tool “Search Pathway” (www.genome.jp/kegg/tool/map_pathway1.html). KEGG pathway analysis mapped 303 genes in the list of downregulated DEGs into various pathways including glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, fructose and mannose metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, and steroid biosynthesis (Supplementary Table 4 (23)). We have further sorted the list of genes that are mapped to glycolysis, terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, and steroid biosynthesis and reorganized them to glycolysis and cholesterol synthesis pathways as depicted in Fig. 6A. Furthermore, using the cells treated with or without hCG (1 IU/mL) in the absence or presence of T-5224 (20 µM) for 12 hours, we found that hCG increased the levels of mRNA for glucose transporter (SLC2A1), glycolysis activator (PFKFB3), and genes encoding enzymes involved in cholesterol de novo biosynthesis such as ACSS2, HMGCS1, MVK, MVD, SQLE, LSS, CYP51A1, and EBP (Fig. 6B). As expected, the hCG-induced expression of these genes was significantly inhibited by T-5224.

Figure 6.

The effect of T-5224 on the expression of genes involved in glycolysis and cholesterol de novo biosynthesis. (A) A schematic diagram depicts selected DEGs involved in glycolysis (SLC2A1, PFKFB3, PKFKB4, and LDHA) and cholesterol de novo biosynthesis (ACSS1, ACSS2, HMGCS1, MVK, MVD, FDPS, SQLE, LSS, CYP51A1, EBP, and DHCR24). (B) The levels of 10 selected DEGs depicted were measured by qPCR analysis and normalized to the levels of RNA18S5 in each sample (n = 5-6 independent batches). Bars with no common superscripts are significantly different (P < 0.05).

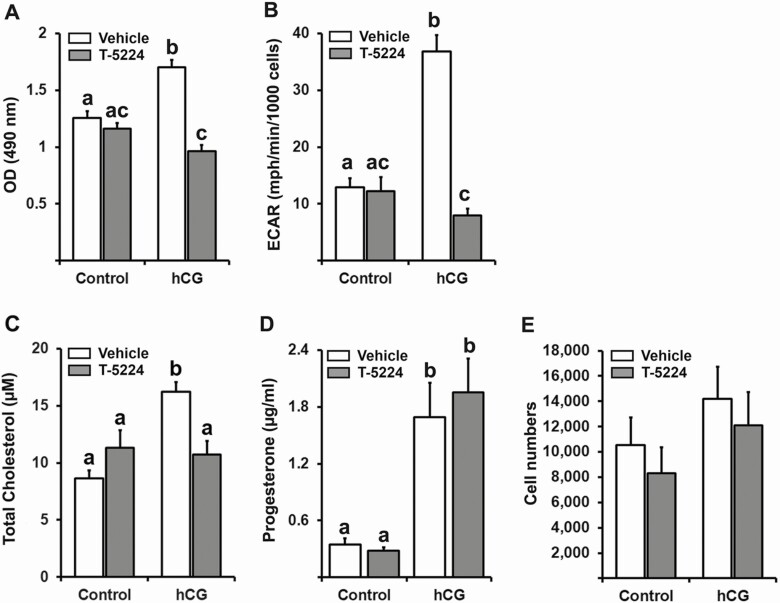

The effect of T-5224 on cell metabolism, glycolysis, and de novo cholesterol biosynthesis

To determine whether the alteration in gene expression profile by T-5224 resulted in functional changes, cell metabolic activity, glycolysis, and cholesterol biosynthesis were assessed in hGLC treated with or without hCG (1 IU/mL) in the absence or presence of T-5224 (20 µM). The metabolic activity of hGLC was evaluated using the MTS assay. As shown in Fig. 7A, MTS values were increased by hCG, but the increase was inhibited by T-5224. The Seahorse glycolytic stress test was used to examine the cellular glycolytic activity by measuring the rate of extracellular acidification resulting from glycolysis (ECAR). The result showed that the hCG-induced drastic increases in glycolytic stress were suppressed by T-5224 (Fig. 7B). Cholesterol levels in hGLCs were increased in response to hCG; T-5224 reduced the hCG-induced increase in cholesterol levels (Fig. 7C). As expected, hCG increased progesterone levels in conditioned media, but T-5224 had no effects on hCG-induced increases in progesterone levels (Fig. 7D). The number of cells in the culture was also measured to normalize ECAR values and were found to be unaltered by the treatment of hCG or T-5224 (Fig. 7E), indicating that the effects on the metabolism observed were not associated with the number of cells in culture.

Figure 7.

The effect of T-5224 on granulosa cell metabolic changes. Primary hGLCs were cultured without (control) or with hCG (1 IU/mL) ± T-5224 (20 µM) for 24 hours. (A) Cell metabolic activity was assessed by recording the absorbance at 490 nm using MTS assays. The experiments were repeated in 10 independent batches which had 4 replicates per batch. OD, optical density. (B) Seahorse XF glycolysis stress tests were performed to measure glycolytic function in cells by directly measuring the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR). The experiments were repeated in 4 independent batches with at least 4 replicates per batches. (C) Cholesterol levels in hGLC lysates were measured by cholesterol fluorescence assay. The fluorescence was read using excitation wavelength at 535 nm and emission wavelength at 590 nm. The experiments were repeated in 4 independent batches. (D) The concentration of progesterone was measured in condition media. The experiments were repeated in 4 independent patient samples. (E) Numbers of cells per treatment were assessed by in situ counting nuclei fluorescently labeled with Hoechst 33 342 in 4 independent patient samples, each with 4 replicates. Bars with no common superscripts were significantly different (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The present study revealed that in human granulosa cells, the expression of FOS and each member of the Jun family exhibited distinctive temporal changes and relationship between mRNA and protein levels in response to hCG stimulation. For instance, FOS mRNA profile showed 2 rapid and transient increases, the first one immediately after hCG treatment and the second at 12 hours, each with the corresponding transient accumulation in protein. Meanwhile, among Jun proteins, only JUNB mRNA levels showed a rapid and transient increase immediately after hCG stimulation, which followed by protein accumulation and stabilization lasted for several hours. hCG also increased JUN and JUND protein levels, although a discrepancy between mRNA and protein profile was observed for JUND. Collectively, these data unveiled FOS, JUN, and JUNB as immediate response proteins upregulated by hCG, whereas the upregulation of JUND was more gradual and sustained in human granulosa cells. In addition, the present data showing the evidence of FOS binding to all 3 members of the Jun family indicated that FOS exists as multiple forms (eg, FOS/JUN, FOS/JUNB, FOS/JUND), although the ratio of each FOS/AP-1 complex is likely different at early and later time points depending on the availability of different Jun proteins present at those time points.

With the finding showing a rapid rise in FOS, JUN, and JUNB expression by hCG, the next logical question was then what the cellular mechanism was driving these acute responses. It is well known that the LH surge/hCG activates adenylate cyclase, which increases intracellular cAMP, leading to the activation of PKA as the primary signaling pathway, and subsequently causing the activation of multiple downstream kinase pathways (32,33,35,36). Herein, our data indicated that cAMP-PKA-p42/44MAPK was a primary, immediate signaling pathway activated by hCG in our primary human granulosa cell cultures. Furthermore, studies using inhibitors for both PKA (H89) and p42/44MAPK (SCH772984) demonstrated that hCG-activated PKA and p42/44MAPK pathways are responsible for rapid increases in FOS, JUN, and JUNB expression in hGLC. Consistent with our findings, in rat granulosa cells, (Bu)2cAMP (an activator of the PKA pathway) induced a rapid and transient increase in Fos and Jun mRNA levels (37). The involvement of the PKA and p42/44MAPK pathways in the up-regulation of Fos and Jun family members has also been reported in nonovarian cells (reviewed in (38)). For instance, the activated PKA or p42/44MAPK has been shown to phosphorylate CREB that, in turn, acts directly on the promoter region of these genes to regulate their expressions (39–43). Therefore, it is plausible that hCG-induced rapid increases in FOS, JUN, and JUNB expression could have been, in part, mediated by cAMP-PKA-CREB or cAMP-PKA-p42/44MAPK pathways in human granulosa cells during the early ovulatory period.

The current findings revealed the transient increase in FOS expression after hCG stimulation at 2 different time points. These data implicate a role for this transcription factor at 2 different ovulatory time windows, 1 immediate after hCG and another later in the ovulatory period. Initially, RNA-seq analysis was performed on the cells collected at 3 hours after hCG ± T-5224 (FOS inhibitor) treatment when the first peak of FOS was observed. To our surprise, only 12 DEGs (3 downregulated and 9 upregulated by T-5224) were identified in 3-hour samples (n = 3 independent samples/treatment, hCG vs hCG+T5224; Supplementary Fig. 1 (23)). When examined whether any of these 12 genes are regulated by hCG using existing in vivo (34) or in vitro (our pilot RNA-seq data generated for the unrelated experiment) datasets, we found that only 2 genes, MT1M (3.6-fold) and MT1E (2.6-fold) were upregulated by hCG in vivo and in vitro, respectively. The levels of mRNA for these genes were further increased by T-5224 (~2-fold), suggesting that the FOS/AP-1 may have an inhibitory function in the hCG-induced expression of these genes. Both MT1M and MT1E encode members of the metallothionein superfamily. The function of these proteins has not been well defined, but suggested to be involved in suppressing metabolic/oxidative stress during the ovulatory process (44,45). At present, we do not have a clear explanation for the lack of T-5224’s effect at 3 hours, but one possibility might be a time-delay between the peak expression of FOS and its downstream target genes, although this possibility needs to be explored in future studies. In contrast, in 12-hour samples, numerous genes were found to be differentially regulated in the cells treated with hCG+T-5224 compared with hCG alone, indicating that the FOS/AP-1 is involved directly or indirectly in regulating the expression of these genes. To pinpoint the potential target genes of FOS/AP-1 that are relevant to physiological changes associated with the ovulatory process, we decided to focus on genes that were previously reported to be highly upregulated after ovulatory hCG administration in vivo, but found to be downregulated by T-5224 in our DEG analysis. The rationale for this approach was to identify the genes to which the FOS/AP-1 complex acts as a positive transcriptional regulator in human ovulatory follicles. The selected genes listed in Table 1 included many ovulatory genes known to be involved in matrix remodeling (eg, HAS2, PTX3, F3, ADAMTS1, ADAMTS9, TFPI2), prostaglandin synthesis and transport (eg, CD24, SLCO2A1, PTGES), transcription factors (eg, RUNX1, ID2), and cell signaling molecules (eg, MAPK14, RGS2) (3,24,46–57). These data highlighted that FOS/AP-1 is involved in regulating diverse, yet crucial aspects of the ovulatory process from cellular signaling to matrix remodeling. Noteworthy is also the presence of many genes in Table 1 that have not been yet studied in human ovulatory follicles, providing an important list of potential target genes of the FOS/AP-1 and possible impact(s) of these genes on the ovulatory process in humans.

In addition to these genes, the analysis of downregulated DEGs using a basic online pathway mapping tool (eg, KEGG) unveiled the impact of FOS inhibition on various aspects of cell metabolism (Supplementary Table 4 (23)). Of particular interest was the genes involved in glucose uptake/glycolysis (SLC2A1 and 2, PFKFP3 and 4, ACSS1 and 2) and cholesterol biosynthesis (HMGCS1, MVK, MVD, FDPS, SQLE, LSS, CYP51A1, EBP, DHCR24; see Fig. 6A) because these processes are associated with the hCG-induced luteal transformation (58,59). Indeed, not only did hCG increase the expression of these genes, but also stimulated metabolic activity, glycolysis, and cholesterol biosynthesis in cultured human granulosa cells (Fig. 7). These increases were reduced by the FOS inhibitor, providing strong support for the role of FOS/AP-1 in hCG-induced metabolic changes associated with luteinization. Interestingly, the reduction in cholesterol levels by T-5224 was not translated into changes in progesterone levels at 24 hours in cultures. The discoordination between cholesterol and progesterone levels might be explained by following findings: (1) T-5224 had no effects on the expression of genes involved in the conversion of cholesterol to progesterone (eg, no changes in levels of mRNA for CYP11A1, HSD3B1, and STAR) and (2) hGLC contained high levels of cholesterol even in the T-5224-inhibited condition (~1 µM), indicating the presence of sufficient substrate for progesterone synthesis. In agreement with this notion, Endresen et al. (60) reported that blocking the de novo cholesterol synthesis did not affect immediate progesterone production in cultured human granulosa cells, and this was in part because of a large store of cholesteryl esters in preovulatory human granulosa cells. Therefore, it still remains to be determined whether the importance of de novo synthesis of cholesterol can be detectable only when the cells were cultured for longer periods after depleting its cholesterol storage. Nonetheless, the present data showed that FOS/AP-1 affects the expression of genes involved in specific metabolic changes (eg, glycolysis, cholesterol synthesis) in human granulosa/lutein cells.

In summary, we found that the expression of FOS was immediately upregulated in response to hCG stimulation, but this increase was short-lived and followed by a second transient rise at a later time point. All 3 members of the Jun family were also increased by hCG and were able to form a complex with FOS, indicating that at least 3 different forms of the FOS/AP-1 complex were present in human granulosa/lutein cells. This study identified the list of potential target genes of FOS/AP-1, among which included clusters of known ovulatory genes involved in matrix remodeling, prostaglandin synthesis and transport, transcription factors, and cell signaling molecules. In addition, the current study revealed the impact of FOS inhibition on the expression of an array of genes involved in glucose uptake/glycolysis and cholesterol biosynthesis, both of which are hallmarks of luteinization. It is important to note, though, that it remains to be determined which of these genes are direct transcription targets of the FOS/AP-1 complex and whether the FOS/AP-1 acts on different sets of target genes during 2 different ovulatory windows. In conclusion, the present study provided novel insights into the cellular mechanisms controlling the expression of FOS and Jun proteins and the role of the FOS/AP-1 complex in regulating the expression of diverse, yet critical, genes required for ovulation and luteinization in the human ovary.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Patrick Hannon and Ketan Shrestha for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the Lalor Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (Y.C.), the National Institutes of Health grants, P01HD71875 (M.J. and T.E.C.), R03HD095098 (M.J.), and R01HD096077 (M.J.). The seahorse glycolytic stress test was supported by the Redox Metabolism Shared Facility of the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center (P30CA177558).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AP-1

activating protein-1

- CL

corpora lutea

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ECAR

extracellular acidification rate

- hCG

human chorionic gonadotropin

- hGLC

human granulosa/lutein cell

- IVF

in vitro fertilization

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- pAKT

phosphorylated AKT

- PCA

principal component analysis

- pCREB

phosphorylated CREB

- PKA

protein kinase A

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- RNA-seq

RNA-sequencing

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repository listed in References.

References

- 1. Duffy DM, Ko C, Jo M, Brannstrom M, Curry TE. Ovulation: parallels with inflammatory processes. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(2):369-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fan HY, Liu Z, Johnson PF, Richards JS. CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBP)-alpha and -beta are essential for ovulation, luteinization, and the expression of key target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(2):253-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robker RL, Russell DL, Espey LL, Lydon JP, O’Malley BW, Richards JS. Progesterone-regulated genes in the ovulation process: ADAMTS-1 and cathepsin L proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(9):4689-4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim J, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK. Signaling by hypoxia-inducible factors is critical for ovulation in mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150(7):3392-3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee-Thacker S, Jeon H, Choi Y, et al. Core binding factors are essential for ovulation, luteinization, and female fertility in mice. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):9921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choi Y, Rosewell KL, Brännström M, Akin JW, Curry TE Jr, Jo M. FOS, a critical downstream mediator of PGR and EGF signaling necessary for ovulatory prostaglandins in the human ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(11):4241-4252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glover JN, Harrison SC. Crystal structure of the heterodimeric bZIP transcription factor c-Fos-c-Jun bound to DNA. Nature. 1995;373(6511):257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kouzarides T, Ziff E. The role of the leucine zipper in the fos-jun interaction. Nature. 1988;336(6200):646-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mechta-Grigoriou F, Gerald D, Yaniv M. The mammalian Jun proteins: redundancy and specificity. Oncogene. 2001;20(19):2378-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakabeppu Y, Ryder K, Nathans D. DNA binding activities of three murine Jun proteins: stimulation by Fos. Cell. 1988;55(5):907-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Halazonetis TD, Georgopoulos K, Greenberg ME, Leder P. c-Jun dimerizes with itself and with c-Fos, forming complexes of different DNA binding affinities. Cell. 1988;55(5):917-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Angel P, Imagawa M, Chiu R, et al. Phorbol ester-inducible genes contain a common cis element recognized by a TPA-modulated trans-acting factor. Cell. 1987;49(6):729-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Piechaczyk M, Blanchard JM. c-fos proto-oncogene regulation and function. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1994;17(2):93-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hess J, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M. AP-1 subunits: quarrel and harmony among siblings. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 25):5965-5973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abate C, Marshak DR, Curran T. Fos is phosphorylated by p34cdc2, cAMP-dependent protein kinase and protein kinase C at multiple sites clustered within regulatory regions. Oncogene. 1991;6(12):2179-2185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tanos T, Marinissen MJ, Leskow FC, et al. Phosphorylation of c-Fos by members of the p38 MAPK family. Role in the AP-1 response to UV light. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(19):18842-18852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ohki M, Ohki Y, Ishihara M, et al. Tissue type plasminogen activator regulates myeloid-cell dependent neoangiogenesis during tissue regeneration. Blood. 2010;115(21):4302-4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li H, Zhou J, Wei X, et al. miR-144 and targets, c-fos and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2), modulate synthesis of PGE2 in the amnion during pregnancy and labor. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Angel P, Karin M. The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell-proliferation and transformation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1072(2-3):129-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richards JS, Russell DL, Ochsner S, Espey LL. Ovulation: new dimensions and new regulators of the inflammatory-like response. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:69-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stocco C, Telleria C, Gibori G. The molecular control of corpus luteum formation, function, and regression. Endocr Rev. 2007;28(1):117-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xie C, Jonak CR, Kauffman AS, Coss D. Gonadotropin and kisspeptin gene expression, but not GnRH, are impaired in cFOS deficient mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;411:223-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Choi Y, Jeon H, Akin J, Curry TE, Jo M. Supplementary data from: the FOS/AP-1 regulates metabolic activity, glycolysis, and cholesterol synthesis in human periovulatory granulosa cells. Figshare Digital Repository. Deposited February 27, 2021. http://figshare.com/s/226561696041890ea18d.

- 24. Choi Y, Wilson K, Hannon PR, et al. Coordinated regulation among progesterone, prostaglandins, and EGF-like factors in human ovulatory follicles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(6):1971-1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Al-Alem L, Puttabyatappa M, Rosewell K, et al. Chemokine ligand 20: a signal for leukocyte recruitment during human ovulation? Endocrinology. 2015;156(9):3358-3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen RH, Abate C, Blenis J. Phosphorylation of the c-Fos transrepression domain by mitogen-activated protein kinase and 90-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(23):10952-10956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gazon H, Barbeau B, Mesnard JM, Peloponese JM Jr. Hijacking of the AP-1 signaling pathway during development of ATL. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Karin M, Liu Zg, Zandi E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9(2):240-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ye N, Ding Y, Wild C, Shen Q, Zhou J. Small molecule inhibitors targeting activator protein 1 (AP-1). J Med Chem. 2014;57(16):6930-6948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226(1):497-509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shu Q, Li W, Li J, Wang W, Liu C, Sun K. Cross-talk between cAMP and MAPK pathways in HSD11B2 induction by hCG in placental trophoblasts. Plos One. 2014;9(9):e107938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Riccetti L, Yvinec R, Klett D, et al. Human luteinizing hormone and chorionic gonadotropin display biased agonism at the LH and LH/CG receptors. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wissing ML, Kristensen SG, Andersen CY, et al. Identification of new ovulation-related genes in humans by comparing the transcriptome of granulosa cells before and after ovulation triggering in the same controlled ovarian stimulation cycle. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(5):997-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Casarini L, Lispi M, Longobardi S, et al. LH and hCG action on the same receptor results in quantitatively and qualitatively different intracellular signalling. Plos One. 2012;7(10):e46682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Choi J, Smitz J. Luteinizing hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin: origins of difference. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;383(1-2):203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ness JM, Kasson BG. Gonadotropin regulation of c-fos and c-jun messenger ribonucleic acids in cultured rat granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1992;90(1):17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Herdegen T, Leah JD. Inducible and constitutive transcription factors in the mammalian nervous system: control of gene expression by Jun, Fos and Krox, and CREB/ATF proteins. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;28(3):370-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ofir R, Dwarki VJ, Rashid D, Verma IM. CREB represses transcription of fos promoter: role of phosphorylation. Gene Expr. 1991;1(1):55-60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lamph WW, Dwarki VJ, Ofir R, Montminy M, Verma IM. Negative and positive regulation by transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein is modulated by phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(11):4320-4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cha-Molstad H, Keller DM, Yochum GS, Impey S, Goodman RH. Cell-type-specific binding of the transcription factor CREB to the cAMP-response element. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(37):13572-13577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de Groot RP, Auwerx J, Karperien M, Staels B, Kruijer W. Activation of junB by PKC and PKA signal transduction through a novel cis-acting element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19(4):775-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Costes S, Broca C, Bertrand G, et al. ERK1/2 control phosphorylation and protein level of cAMP-responsive element-binding protein: a key role in glucose-mediated pancreatic beta-cell survival. Diabetes. 2006;55(8):2220-2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Nejdl L, Gumulec J, et al. The role of metallothionein in oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(3):6044-6066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Si M, Lang J. The roles of metallothioneins in carcinogenesis. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Varani S, Elvin JA, Yan C, et al. Knockout of pentraxin 3, a downstream target of growth differentiation factor-9, causes female subfertility. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(6):1154-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Salustri A, Garlanda C, Hirsch E, et al. PTX3 plays a key role in the organization of the cumulus oophorus extracellular matrix and in in vivo fertilization. Development. 2004;131(7):1577-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blaha M, Nemcova L, Kepkova KV, Vodicka P, Prochazka R. Gene expression analysis of pig cumulus-oocyte complexes stimulated in vitro with follicle stimulating hormone or epidermal growth factor-like peptides. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Carletti MZ, Christenson LK. Rapid effects of LH on gene expression in the mural granulosa cells of mouse periovulatory follicles. Reproduction. 2009;137(5):843-855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shimada H, Kasakura S, Shiotani M, et al. Hypocoagulable state of human preovulatory ovarian follicular fluid: role of sulfated proteoglycan and tissue factor pathway inhibitor in the fluid. Biol Reprod. 2001;64(6):1739-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Puttabyatappa M, Al-Alem LF, Zakerkish F, Rosewell KL, Brännström M, Curry TE Jr. Induction of tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 by hCG regulates periovulatory gene expression and plasmin activity. Endocrinology. 2017;158(1):109-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rosewell KL, Al-Alem L, Zakerkish F, et al. Induction of proteinases in the human preovulatory follicle of the menstrual cycle by human chorionic gonadotropin. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(3):826-833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dong JP, Dai ZH, Jiang ZX, et al. CD24: a marker of granulosa cell subpopulation and a mediator of ovulation. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(11):791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jo M, Curry TE Jr. Luteinizing hormone-induced RUNX1 regulates the expression of genes in granulosa cells of rat periovulatory follicles. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(9):2156-2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Johnson AL, Haugen MJ, Woods DC. Role for inhibitor of differentiation/deoxyribonucleic acid-binding (Id) proteins in granulosa cell differentiation. Endocrinology. 2008;149(6):3187-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu Z, Fan HY, Wang Y, Richards JS. Targeted disruption of Mapk14 (p38MAPKalpha) in granulosa cells and cumulus cells causes cell-specific changes in gene expression profiles that rescue COC expansion and maintain fertility. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(9):1794-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sayasith K, Sirois J, Lussier JG. Expression and regulation of regulator of G-protein signaling protein-2 (RGS2) in equine and bovine follicles prior to ovulation: molecular characterization of RGS2 transactivation in bovine granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 2014;91(6):139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stocco DM, Clark BJ. Regulation of the acute production of steroids in steroidogenic cells. Endocr Rev. 1996;17(3):221-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brogan RS, MacGibeny M, Mix S, et al. Dynamics of intra-follicular glucose during luteinization of macaque ovarian follicles. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;332(1-2):189-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Endresen MJ, Haug E, Abyholm T, Henriksen T. The source of cholesterol for progesterone synthesis in cultured preovulatory human granulosa cells. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1990;123(3):359-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repository listed in References.