Abstract

Adult working-class Americans spend on average 50% of their workday awake time at their jobs. The vast majority of these jobs involve mostly physically inactive tasks and frequent exposure to unhealthy food options. Traditionally, the workplace has been a challenging environment for cardiovascular prevention, where cardiovascular guidelines have had limited implementation. Despite the impact that unhealthy lifestyles at the workplace may have on the cardiovascular health of U.S. workers, there is currently no policy in place aimed at improving this. In this review, we discuss recent evidence on the prevalence of physical inactivity among Americans, with a special focus on the time spent at the workplace; and the invaluable opportunity that workplace-based lifestyle interventions may represent for improving the prevention of cardiovascular disease. We describe the current regulatory context, the key stakeholders involved, and present specific, guideline-inspired initiatives to be considered by both Congress and employers to improve the “cardiovascular safety” of US jobs. Additionally, we discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic has forever altered the workplace, and what lessons can be taken from this experience and applied to cardiovascular disease prevention in the new American workplace. For many Americans, long sitting hours at their job represent a risk to their cardiovascular health. We discuss how a paradigm shift in how we approach cardiovascular health, from focusing on leisure time to also focusing on work time, may help curtail the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in this country.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Diets, Job safety, Physical activity, Occupational health, Prevention, Workers

Abbreviations and acronyms

- ACA

Affordable Care Act

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- OSHA

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- PPHF

Prevention and Public Health Fund

1. Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) remains a leading cause of death in the US [1,2]. Despite breakthrough advances in the management of acute myocardial infarctions and strokes [3], an 80% increase in the use of statin therapy in the last two decades [4], and a reduction in the national average levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [5], cardiovascular deaths are now rising among working-age Americans [6]. These concerning trends may be explained by striking increases in the incidence and prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes across the country. As of 2019, 69% of US adults were overweight or obese [7], and more than 30 million had diabetes [8].

Physical inactivity and unhealthy diets are regarded key driving factors of the epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes [9,10], and are independently associated with premature mortality [11,12]. A number of recommendations were included in the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Primary Prevention Guidelines aimed at curbing these epidemics by increasing the levels of physical activity and improving the dietary choices of Americans [13,14]. However, the effectiveness of similar recommendations in the past was far from satisfactory.

This failure may have been in part due to the fact that while lifestyle recommendations, particularly those regarding physical activity, are typically understood as targeting leisure time, the average adult working-class American men and women spend at least 50% of their workday awake time at their jobs [15]. Moreover, more than 80% of jobs in the US involve mostly sedentary activities [16], which results in daily exposure to long sitting hours and a colossal work-related lifetime exposure to physically inactive behaviors. Also, from a dietary perspective, most workers have at least one daily meal at their workplace, where unhealthy drinks and food options are often widely available through vending machines and, in large companies, staff cafeterias.

Despite the impact that these occupational exposures have on the cardiovascular health of the general US workforce, there is currently no national policy in place aimed at improving them. In this review, we intend to provide an update and advance important prior studies and discussions. We discuss the invaluable opportunity that workplace-based lifestyle interventions provide for improving the prevention of ASCVD in the country. For this to happen, we describe the current regulatory context, outline the key stakeholders, and present specific, guideline-inspired initiatives to be considered by both Government and employers to improve the cardiovascular health of US workers. We discuss key challenges, current evidence gaps, and future directions in this important field. Finally, we discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the workplace and in doing so created a unique opportunity to enhance cardiovascular safety in the new American workplace.

2. Workday hours, physical inactivity, and opportunities for ASCVD prevention

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Americans sleep an average of 7 h/day. This allows for ~17 daily hours in which physically active tasks can occur. During workdays (Mondays to Fridays), there are three main types of activities during which exercise and physical activity can happen: leisure time, commute, and work.

2.1. Leisure time

Physical inactivity is pervasive during spare time in the US and is further increasing with the rise of “screen time.” [9] Television and video watching trends remain high but stable, while there has been a marked rise in time spent using computers and smartphones during leisure time. Although many Americans describe lack of time as a main barrier to be more active [17], no group averages less than 4.5 h/day of leisure time [18]; however, most of it is spent sitting rather than engaging in physically demanding tasks or exercise. Also, many social and family activities involve sitting and consuming snacks and drinks of low nutritional quality.

There is no question about the need for cardiovascular prevention interventions targeting leisure time. Nevertheless, the forces impacting it can be very challenging to counter—screen time and unhealthy food options are often easier, cheaper, and even more addictive than healthier ones. Moreover, even among individuals who exercise on a daily basis (which is associated with marked reductions in ASCVD risk), high daily amounts of sitting remain independently associated with adverse cardiovascular events, hospitalization, and death [11,12]. Therefore, interventions targeting leisure time alone will likely fall short of curbing the epidemics of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and ASCVD.

2.2. Commuting

Currently, only 3% of American workers bicycle or walk to work, while the vast majority use cars or public transportation [19]. Additionally, daily commutes to work are becoming progressively longer, with an average one-way commute of 27 min in 2018 – 5 more minutes each way than a decade ago [20]. Workers with longer commuting distances tend to be less physically active, which is associated with higher rates of obesity and hypertension [21]. Although interventions aimed at promoting and facilitating active commutes are warranted, long distances, adverse weather conditions, traffic volume and other contextual factors represent barriers which may ultimately limit their effectiveness.

2.3. Work

Since 1950, the contraction of the manufacturing industry, the expansion of automation, and the rise of service and technology industries have resulted in an 83% increase in physically inactive jobs [16]. Physically demanding occupations now make up less than 20% of the US workforce, down from nearly 50% of jobs in 1960 [16]. Thus, over the last 60 years, the American workforce collectively “sat down”: while in the 1960s many workers would meet ACC/AHA’s recommendations for daily physical activity just with the activities performed during workhours, as of 2020 the majority spend most of their 8.5 h/workday at work sitting [15]. Physically inactive jobs are associated with worse health outcomes—for every additional hour sitting above 5 hours, waist circumference is 2 cm greater, and ASCVD risk increases [21]. In addition, availability of low-quality foods and limited vending options in many workplaces often result in unhealthy food choices at work [22]. Of note, the latter correlate strongly with unhealthy eating habits outside of work as well [23].

Several recent studies have tried to identify jobs which are at particularly higher risk for the development of ASCVD. A national survey of long-haul truck drivers at 32 truck stops across 48 states found that obesity (69% versus 31%, p < 0.01) and current smoking (51% versus 19%, p < 0.01) were twice as prevalent in long-haul truck drivers as in the U.S. adult working population [24]. A recent study of the association between the twenty most common occupations and heart disease in women found that women who worked as social workers or as cashiers were 36% and 33%, respectively, more likely to have heart disease compared with other professions [25]. These studies identify specific populations of workers with a particularly high burden of CVD risk factors, with long periods of sitting being a common feature, and therefore at high risk for heart disease. Importantly, although these groups represent cohorts in which physical activity and healthy diet interventions would be particularly meaningful, the high rates of physical inactivity in most US workers call for the need to consider broader interventions in most US workplaces.

As described by Rose, interventions targeting entire populations or communities (in this setting, all workers) can shift the distribution of the target cardiovascular risk factors downwards, potentially resulting in dramatic reductions of ASCVD events [26]. Also, as demonstrated by Fuster and colleagues, lifestyle preventive interventions involving groups of peers are more effective than individual self-management approaches [27]. For these reasons, together with the large amount of daily hours spent at work by working-age Americans, preventive interventions within the workplace represent a promising, potentially powerful paradigm to enhance the primordial, primary, and secondary prevention of ASCVD in the country.

3. Regulatory context: protecting US workers from health hazards

With the 1970 Occupational Safety and Health Act, the US Congress created the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to ensure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women by setting and enforcing standards and by providing training, outreach, education and assistance. Aimed primarily at construction, agricultural, and maritime jobs, OSHA put into place regulations that required employers to provide their employees with an environment free from “recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious harm to their employees” [28].

This requirement, known as the General Duty Clause, is triggered by four criteria: 1) there must be a hazard; 2) the hazard must be a recognized hazard; 3) the hazard could cause or is likely to cause serious harm or death; and 4) the hazard must be correctable. These four criteria were met with the passage of the Mining Act of 1977, which led to a 33% decrease in fatalities in mining facilities. Focused mostly on physical and chemical hazards (Table 1), this and other Acts have dramatically improved occupational safety and saved countless lives [29]. Also, the OSHA Technical Manual outlines extensive guidelines aimed at avoiding specific “health hazards” such as heat stress, noise, back disorders and injuries [30]. Each of these clearly exist, can cause harm, and may be correctable, and consequently, there are guidelines available, for example, for noise control and the proper way to lift heavy objects to avoid back injury.

Table 1.

Workplace exposures that have met the OSHA hazard criteria since 1970.

| Year | Regulation |

|---|---|

| 1972 | Toxic and Hazardous Substances |

| 1974 | Exposure to Vinyl Chloride Standard |

| 1976 | Coke Oven Emissions Standard |

| 1977 | Commercial Diving Operations |

| 1978 | Cotton Dust Standard |

| 1978 | Lead Standard |

| 1981 | Hearing Conservation Standard |

| 1984 | Ethylene Oxide Standard |

| 1987 | Farm Workers Standard |

| 1988 | Meat Workers Standard |

| 1990 | Laboratory Safety Standard |

| 1993 | Confined Spaces Standard |

| 1996 | Construction Scaffold Safety |

| 1997 | Marine Terminals Standard |

| 2001 | Protecting Healthcare Workers |

| 2004 | Fire Protection in Shipyard Standard |

| 2010 | Falls in General Industry Standard |

Abbreviations: OSHA = Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) in its creation of the Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF) attempted to make disease prevention a priority to employers [31]. It included three pillars of workplace disease prevention: waiving of cost sharing for preventive services, providing new funding for community preventive services, and new funding for workplace wellness programs [32]. Unfortunately, the funding for PPHF has remained in jeopardy since its inception, limiting its effectiveness.

4. Proposed high-level actions to improve long-term cardiovascular safety in the workplace.

4.1. The Occupational Health and Safety Administration

Although OSHA was created to ensure both workplace health and safety, currently the emphasis is primarily on the latter. We believe that physical inactivity and unhealthy diets both meet the four criteria of a workplace “hazard” set by the General Duty Clause, and that the OSHA Manual could include specific sections on the importance of physical inactivity and unhealthy diets as key risk exposures at the workplace that lead to the development of cardiovascular disease.

Legislation in this area, which started with the Affordable Care Act and its financial support of wellness programs, is still in its early stages. Building on this important work, it is important that future public health programs and interventions have a foundation in the scientific method and target high-risk populations first followed by broad adoption of successful programs that aim to reduce ASCVD risk in the majority of the U.S. working population that is obese or overweight and physically inactive for too long on a daily basis. Initiatives should empower rather than blame and provide financial incentives for employers to always choose the healthier option. We propose that OSHA prioritize cardiovascular health, starting in specific industries and workplace environments. While OSHA sanctions may be effective in preventing accidents and promoting workplace safety in the agricultural and industrial workplace, we do not believe that the traditional OSHA model of sanctioning an employer into compliance is the proper approach to promoting workplace health. A system of sanctions for cardiovascular health infractions would likely be difficult to implement or monitor, and by creating a system of blame rather than responsibility and self-ownership it would run counter to accepted behavioral modification approaches. Instead, OSHA could develop guidelines, recommendations, and educational materials, with the assistance of professional societies (e.g., American Heart Association), business owners, and health economists, that target specific populations or work environments first. Lessons learned from the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of these interventions can then be applied more broadly across industries. In doing so, OSHA can evolve from a sanctioning body focused on accidents and safety into a public health partner that supports employers in their financial goals and employees in their health goals.

4.2. The CDC

A number of initiatives have been developed by the CDC aimed at improving the health of the US workforce, including some programs specifically aimed at the long-term prevention of ASCVD and other chronic diseases. Particularly noteworthy is the CDC Worksite Health ScoreCard, which allows employers to assess their adherence to a number of recommended health promotion interventions, including physical activity and weight loss [33]. However, implementation of these strategies is currently not mandatory, and their dissemination has so far been limited. To foster adherence, we propose a more aggressive communication of these programs to employers, employees, and the general public. Also, while these initiatives demonstrate that the Government recognizes physical inactivity and unhealthy diets as major hazards, they could now be used as roadmap to update OSHA guidelines and develop additional policies.

4.3. Scientific societies

The leadership of cardiovascular scientific societies will be also key for a cardiovascular-healthier workplace paradigm to become reality. The AHA already uses the “Workplace Health Achievement Index” to recognize companies prioritizing the cardiovascular health of their employees [34]. Also, programs such as the AHA’s Workplace Walking Program Kit [35] provide employers and employees with a variety of resources to increase walking and other healthy lifestyles at the workplace. Once again, these initiatives are not well known, even among the cardiovascular community, and further efforts should be made to improve their dissemination and implementation. Of note, OSHA and AHA have a partnership focused on workplace training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. We propose that this partnership expand to incorporate a more comprehensive and directed emphasis upon preserving cardiovascular health.

4.3. Employers

Besides legislation and accreditation, additional approaches to further engage employers will need to be explored. Productivity and employee health are not mutually exclusive but, in fact, are synergistic. Healthy workers are generally more productive workers, have lower health related costs, fewer health-related work restrictions, higher retention, and lower absentee rates [36]. Over the long term, publicly traded companies that are awarded health achievement awards outperform Standard and Poor’s index year after year [37]. Dissemination efforts should be made to effectively communicate to employers that investing in a worker’s cardiovascular health is, in turn, an investment in the business itself. Employers who demonstrate the success of these health promotion efforts could be rewarded fiscally by government incentives and health insurance providers.

5. Proposed specific interventions

Interventions at the workplace aimed at curbing the epidemics of obesity, diabetes and ASCVD should combine actions aimed at promoting and facilitating regular physical activity and preventing long sitting periods with others aimed at improving the quality of available foods. There is conclusive evidence that small reductions in physical inactivity are associated with reductions in risk of premature death, and cardiovascular-healthy diets reduce premature mortality [38]. A summary of key proposed interventions is presented in Table 2, and Table 3 displays the 2019 ACC/AHA recommendations [14] that inspire these approaches. The ultimate goal is to maximize the opportunities to implement lifestyle guideline recommendations, specifically in workplace environments, by adapting them to their contextual characteristics and using the tools available (Fig. 1). As advocated by Rose [26], we have prioritized interventions that promote and facilitate healthy habits while maximizing their respect to individuals’ informed choices. Additional proposed interventions are included in relevant CDC and AHA published materials [33,35].

Table 2.

Key goals and examples of associated interventions aimed at reducing physical inactivity and improving the dietary quality of meals at the workplace.

| Goals | Actions aimed at promoting and facilitating each of them |

|

|---|---|---|

| Specific | General | |

| Reducing physical inactivity | ||

| Standing work stints | Provide standing work stations | Provide frequent trainings, use health messaging Create a culture of health and promotion of physical activity at the workplace Employee champions Awards |

| Standing/walking calls | Provide hands-free devices | |

| Standing/walking meetings | Create walkable spaces | |

| Walk breaks | ||

| Use stairs | Increase visibility, promote use | |

| Active commute | Infrastructures: make bicycle parking lots available; provide bicycles to employees | |

| Self-monitoring and informal competitions | Provide step counters; gamification of physical activity at the workplace | |

| Formal competitions | Host periodic sports events | |

| Active day breaks | Host periodic retreats including sports and exercise | |

| Improving the dietary quality of meals at the workplace | ||

| Cardiovascular healthy choices for meals at the workplace | Make healthy foods available at vending machines and staff cafeterias at affordable cost | Provide frequent trainings, use health messaging Create a culture of healthy eating and drinking at the workplace Limit availability of unhealthy options |

| Reduce intake of unhealthy snacks and sugary beverages | Make healthy options available at vending machines | |

| Make mineral water easily available | ||

| Active day breaks | Host periodic retreats including healthy cooking activities | |

Table 3.

Recommendations included in the 2019 ACC/AHA Primary Prevention Guidelines relevant to the recommendations included in this document.

| 2019 ACC/AHA Primary Prevention Guidelines |

Specific potential intervention at the workplace to which applies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation | COR | LOE | |

| Adults should be routinely counseled in healthcare visits to optimize a physically active lifestyle | I | B-R | Periodic trainings, promotion of physical activity |

| For adults unable to meet the minimum physical activity recommendations (at least 150 min per week of accumulated moderate-intensity or 75 min per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity), engaging in some moderate- or vigorous-intensity physical activity, even if less than this recommended amount, can be beneficial to reduce ASCVD risk | IIa | B-NR | Walk breaks, walking calls, walking meetings, active commute, active day breaks and retreats involving exercise |

| Decreasing sedentary behavior in adults may be reasonable to reduce ASCVD risk; sedentary behavior defined as any waking behavior characterized by an energy expenditure ≤1.5 METs while in a sitting, reclining, or lying posture. Standing is a sedentary activity in that it involves ≤1.5 METs, but it is not considered a component of sedentary behavior | IIb | C-LD | Standing work stints, standing calls, standing meetings |

| Exercise and physical activity: In addition to the prescription of exercise, neighborhood environment and access to facilities for physical activity should be assessed | N/A | N/A | Provide standing work stations, hands-free devices, infrastructures facilitating active commute, create walkable spaces |

| A diet emphasizing intake of vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, whole grains, and fish is recommended to decrease ASCVD risk factors | I | B-R | Make healthy foods and snacks available at cafeterias and vending machines, mineral water easily available |

| Replacement of saturated fat with dietary monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats can be beneficial to reduce ASCVD risk | IIa | B-NR | |

| A diet containing reduced amounts of cholesterol and sodium can be beneficial to decrease ASCVD risk | IIa | B-NR | |

| As a part of a healthy diet, it is reasonable to minimize the intake of processed meats, refined carbohydrates, and sweetened beverages to reduce ASCVD risk | IIa | B-NR | |

| As a part of a healthy diet, the intake of trans fats should be avoided to reduce risk | III | B-NR | |

| Adults with overweight and obesity: Counseling and comprehensive lifestyle interventions, including calorie restriction, are recommended for achieving and maintaining weight loss | I | B-R | All |

Abbreviations: ACC/AHA = American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; B-R = B randomized; B-NR = B non-randomized; C-LD = C limited data; COR = class of recommendation; LOE = level of evidence; MET(s) = metabolic equivalent(s); N/A = not applicable.

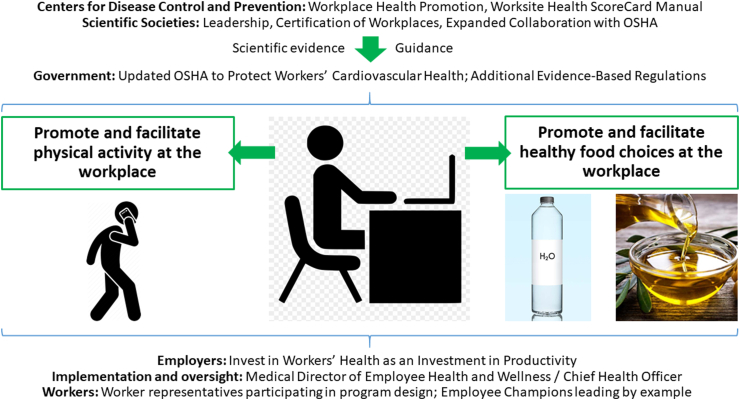

Fig. 1.

Stakeholders in the long-term “cardiovascular safety” of jobs in the US.

Cardiovascular disease prevention in the workplace will require specific actions by all key stakeholders. Government agencies, primarily OSHA, could partner further with cardiovascular societies to promote workplace certificates of cardiovascular safety. Employers could promote physical activity in the workplace and invest in worksite cardiovascular preventive measures, led by Chief Health Officers.

Abbreviations: OSHA = Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

5.1. Promoting and facilitating physical activity

Training sessions, detailed health information, and frequent messaging on the hazards of long sitting hours and the benefits of physical activity could be provided to workers. These can improve nutritional habits, physical activity, and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors [39,40]. Also, although the evidence on the health benefits of wearable activity monitoring systems is currently mixed, provision of these to employees in combination with other initiatives may increase their knowledge about their daily physical activity, ultimately triggering healthy lifestyle change.

Employers could invest in modeling the workplace to facilitate walk breaks (e.g., making safe walking paths available), and standing/walking meetings and calls, which represent key opportunities to increase physical activity taking advantage of tasks during which use of screens is often not needed. Active commutes could be facilitated by making the necessary infrastructures available (e.g., bicycle racks). Additionally, companies could make gyms available at or close to the workplace and facilitate access and membership. Corporate recreational activities could be promoted based on sports as an extension of work.

5.2. Improving dietary choices

While not all jobs are logistically able to facilitate physical activity, many have vending machines, most large companies have staff cafeterias, and all have a lunch break. Training sessions and information on healthy dietary and cooking options could be provided on a regular basis to all workers. Cardiovascular-healthy foods and snacks could be made available at competitive prices and encouraged on expense reports. In staff cafeterias, smaller portions could be served, and salad bars made more prominent. Also, water could be provided free of charge and made easy to access throughout the day.

6. Workplace leadership

The role of a Chief Safety Officer is well established, responsible for monitoring workplace activities to ensure that employees comply with company policies and safety regulations. Some large companies also have a chief physician who leads their employee health and well-being strategy. However, too often these priorities are abdicated to health insurance companies, who address individual health rather than the organization’s programs and initiatives. To inform, implement, and oversee the health promotion interventions described above, we propose to further expand the current Chief Safety Officer and physician roles to also focus on the long-term prevention of chronic diseases among workers, particularly ASCVD and cancer as the current major killers in the US [1,2]. In the largest companies, these tasks could be assigned to a novel role—the “Chief Health Officer”. Indeed, the CDC recommends the existence of a “paid health promotion coordinator”, and of “active, diverse health promotion committees.” [33].

Participation of worker representatives in the design of any health promotion initiatives at the workplace will also be crucial, as means to further engage employees and adequately adapt the interventions to their values, priorities, resources and needs. “Employee champions” may also enhance adherence as they lead by example [33].

7. Challenges

Novel ASCVD prevention efforts at the workplace come with important challenges. A crucial one is to ensure that healthy habits are promoted and facilitated while respecting individual informed choices—workers should not be forced to implement changes that they are not genuinely willing to make. In our current obesogenic environments, there is a pervasive cultural promotion of unhealthy habits, thus one of the main goals of health promotion at the workplace should be to counteract that by providing high quality information and frequent reminders of the benefits of healthy habits [26]. Also, labeling should be avoided, and workers’ privacy regarding medical diagnoses should be protected. In general, efforts should be made to ensure that a culture of health and health promotion does not lead to a medicalization of the work environment.

Incentives to workers (e.g., economic) represent a potentially powerful approach to increase their adherence to lifestyle recommendations. However, their potential downsides will need to be considered carefully. For example, some workers with chronic diseases or very high body mass indices may be unable to meet specific physical activity goals, which would penalize them when compared to their healthier peers. Participation of worker representatives when defining incentives and personalization of goals to each individual worker may help maximize potential benefits and minimize downsides.

Additionally, the costs of the above interventions should be weighed against their potential benefits to both worker health and worker productivity. The finanical return of wellness programs has been mixed at best and therefore the financial incentives for employers to invest in wellness initiatives may be lacking. If individual employers cannot be expected to implement effective change in this area, the need for national leadership and policy coupled with financial incetives, in the form of rewards or cost sharing, becomes paramount.

Efforts to promote health in the workplace have thus far led to mixed results, highlighting many of the challenges that large employers face in this area and the need to further enhance and enrich cardiovascular health protection and promotion at the workplace. A recent randomized trial involving 32,975 warehouse employees at a large U.S. retail company found that worksites with a wellness program had an 8.3% higher rate of employees who reported engaging in regular exercise and a 13.6% higher rate of employees who reported actively managing their health. There were, however, no significant differences in clinical health measures, healthcare spending, or employment outcomes at 18 months of follow up [41]. The authors note, and we would agree, that health, spending, and employment outcomes may significantly lag engagement outcomes and 18 months may not capture the long-term impact of these programs. Additionally, if the rise in regular exercise and active health management seen in this study occurred at a national scale the reduction in ASCVD events could be significant.

The recent Illinois Workplace Wellness Study investigated the effects of workplace wellness programs on employee medical spending, productivity, and well-being [42]. Over 12,000 university employees were randomized to join a wellness program that included financial incentives and paid time off for annual on-site biometric screenings, annual health risk assessments, and ongoing wellness activities (physical activity, smoking cessation, and disease management). After 24 months, the wellness programs led to no significant difference in health outcomes or healthcare utilization, but did increase the proportion of employees that reported having a primary care physician. Similar to the prior study, 24 months may not be enough time to see meaningful results in hard cardiovascular endpoints in overall healthy populations.

Prior randomized trials have looked at the effect of workplace wellness programs on weight loss and smoking cessation with some success [43,44]. Findings of these studies stress the need to further enhance our ability to design effective, meaningful, long-lasting interventions at the workplace, which most likely will need to combine multiple interventions simultaneously, adapt them over time, and further engage workers and their leaders in the design of the intervention.

8. Future directions

Further research is needed to build on this work and to better understand the efficacy of specific interventions (e.g., standing tables, wearable technologies) for improving long-term habits and ASCVD risk, their cost-effectiveness (many of the proposed interventions are costly), and their impact on productivity. Workers should be encouraged by their employers to see their primary care physicians regularly and undergo periodic 10-year ASCVD risk assessment as recommended by the ACC/AHA guidelines. Further research is needed to better understand whether physically inactive or sitting hours or even screen time, which are becoming major risk factors in the U.S., should be either included as independent predictors in future ASCVD risk assessment tools, and/or considered “risk enhancing factors” in future primary prevention guidelines. Furthermore, cost-benefit analyses will be key to determining which interventions are worth the investments required by businesses, particularly those to be considered by small- and medium-sized businesses.

Prevention and health promotion clinics could be developed at large workplaces, aimed at providing personalized, individual-level preventive counseling. Also, elective, basic periodic health check-ups could be widely offered (e.g., measurement of body mass index, blood glucose and lipid levels, and blood pressure) as is currently done in a number of companies. A number of other cardiovascular risk factors have a strong presence at the workplace, work-related stress being a ubiquitous one [45]. Therefore, mental health promotion and stress management programs, and interventions aimed at developing a culture of interpersonal respect at the workplace could be considered not only for their intrinsic benefits but also as means to further enhance the cardiovascular safety of jobs in the 21st Century.

Finally, the initiatives discussed in this review should be considered not only in the US but worldwide, as physical inactivity continues to expand in most countries, and diabetes, obesity and ASCVD represent global pandemics. In some European and Asian countries, local public health agencies develop cardiovascular health promotion initiatives in public workplaces, such as the promotion of stair use. Promotion of physical activity at the workplace was also recently advocated by the European Society of Cardiology [46].

9. Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed “the workplace” in America. For a large portion of the workforce, that workplace is now their home, and it will remain so for the foreseeable future made possible by tele-conferencing technologies. But the vast majority of workers will soon return to a workplace unrecognizable in many ways from the way they left it. Workers will encounter temperature checks and symptom screening upon arrival. Social distancing rules will require a redesign of the workspace, with fewer workers filling larger spaces. In-person meetings may, for many companies, become a relic of the past.

There are several important lessons that can be taken from the response to the COVID-19 pandemic specifically at the workplace and applied to enhance ASCVD safety in the workplace. First, it has been made evident that the workplace can be redesigned and reimagined in response to a health challenge. The same efforts that have created a socially distanced workplace, with glass dividers between cubicles and arrows on hallway floors to direct traffic, could be applied to adopting standing desks, healthy snacks, and workplace exercise programs. Second, now is the time to make these important changes. With entire office buildings currently empty there is no better time to redesign the workplace, and with employees at home awaiting a safe return, there will be no disruptions caused by the infrastructure upgrades required. Third, workers do not always need to be sitting at a desk in an office to be productive. Companies across the legal, financial, and technology sectors remain as productive and competitive with their workforce at home. This shift away from the workplace as defined by offices, desks, and chairs, opens the door for innovation in how workers engage with their work. This innovation can be directed at productivity, but it could also be directed at health promotion in the workplace.

10. Conclusions

As of 2020, ASCVD remains a major killer in the US. With the American workforce spending half their waking life at work, cumulative exposure to long sitting hours and unhealthy dietary choices at the workplace are likely key contributors to the current epidemics of diabetes, obesity and ASCVD. In this context, workplace health promotion interventions represent a promising opportunity for curbing ASCVD in this country. The aim of OSHA and the Occupational Safety and Health Act is “to preserve our human resources.” We make a call to update the Act by addressing two key lifestyle exposures within the American workforce, and in doing so, fulfill the dual aim to provide workers with a workplace environment that is both safe and healthy. Given the large potential public health benefits, and the unique opportunity created by the COVID-19 pandemic, this novel paradigm shift should be considered a national priority.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Virani S.S., Alonso A., Benjamin E.J., Bittencourt M.S., Callaway C.W., Carson A.P., Chamberlain A.M., Chang A.R., Cheng S., Delling F.N., Djousse L., Elkind M.S.V., Ferguson J.F., Fornage M., Khan S.S., Kissela B.M., Knutson K.L., Kwan T.W., Lackland D.T., Lewis T.T., Lichtman J.H., Longenecker C.T., Loop M.S., Lutsey P.L., Martin S.S., Matsushita K., Moran A.E., Mussolino M.E., Perak A.M., Rosamond W.D., Roth G.A., Sampson U.K.A., Satou G.M., Schroeder E.B., Shah S.H., Shay C.M., Spartano N.L., Stokes A., Tirschwell D.L., VanWagner L.B., Tsao C.W. American heart association council on epidemiology and prevention statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2020 Mar 3;141(9):e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. Epub 2020 Jan 29. PMID: 31992061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Heart Association Center for health metrics and evaluation. Total cardiovascular disease mortality in the United States (1999-2016) https://healthmetrics.heart.org/total-cardiovascular-disease-mortality-in-the-united-states-1999-2016/ Available online at: (Accessed 8 January 2020)

- 3.Kayani W.T., Ballantyne C.M. Improving outcomes after myocardial infarction in the US population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.008407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salami J.A., Warraich H., Valero-Elizondo J. National trends in statin use and expenditures in the US adult population from 2002 to 2013: insights from the medical expenditure panel survey. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:56–65. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vega G.L., Grundy S.M. Current trends in non-HDL cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels in adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13:563–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtin S. Trends in cancer and heart disease death rates among adults aged 45–64: United States, 1999–2017. The Centers for disease control and prevention. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward Z.J., Bleich S.N., Cradock A.L. Projected U.S. State-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2440–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1909301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diabetes. Data & statistics. National diabetes statistics report. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics/statistics-report.html Available online at: (Accessed 8 January 2020)

- 9.Yang L., Cao C., Kantor E.D. Trends in sedentary behavior among the US population, 2001-2016. J Am Med Assoc. 2019;321:1587–1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patterson R., McNamara E., Tainio M. Sedentary behavior and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33:811–829. doi: 10.1007/s10654-018-0380-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biswas A., Oh P.I., Faulkner G.E. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:123–132. doi: 10.7326/M14-1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandey A., Salahuddin U., Garg S. Continuous dose-response association between sedentary time and risk for cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:575–583. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piercy K.L., Troiano R.P., Ballard R.M. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. J Am Med Assoc. 2018;320:2020–2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnett D.K., Blumenthal R.S., Albert M.A. ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e596–e646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Department of Labor Bureau of labor statistics. News release. American time survey – 2018 results. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/atus.pdf Available online at:

- 16.Church T.S., Thomas D.M., Tudor-Locke C. Trends over 5 decades in U.S. occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PloS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavie C.J., Ozemek C., Carbone S., Katzmarzyk P.T., Blair S.N. Sedentary behavior, exercise, and cardiovascular health. Circ Res. 2019;124:799–815. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sturm R., Cohen D.A. Free time and physical activity among Americans 15 Years or older: cross-sectional analysis of the American time use survey. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E133. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.190017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomer Adie. Brookings Series; 9 Feb. 2018. America’s commuting choices: 5 major takeaways from 2016 census data.www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2017/10/03/americans-commuting-choices-5-major-takeaways-from-2016-census-data/ Available online at: [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Census Bureaus American community survey (ACS) https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/ Available online at:

- 21.Tigbe W.W., Granat M.H., Sattar N., Lean M.E.J. Time spent in sedentary posture is associated with waist circumference and cardiovascular risk. Int J Obes. 2017;41:689–696. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Onufrak S.J., Zaganjor H., Pan L. Foods and beverages obtained at worksites in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119:999–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCurley J.L., Levy D.E., Rimm E.B. Association of worksite food purchases and employees’ overall dietary quality and health. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sieber W.K., Robinson C.F., Birdsey J., Chen G.X., Hitchcock E.M., Lincoln J.E., Nakata A., Sweeney M.H. Obesity and other risk factors: the national survey of U.S. long-haul truck driver health and injury. Am J Ind Med. 2014 Jun;57(6):615–626. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22293. Epub 2014 Jan 4. PMID: 24390804; PMCID: PMC4511102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nriagu B, Ako A, Wang C, Roos AD, Wallace RB, Allison MA, Seguin R, Nassir R, Michael Y. Occupations associated with poor cardiovascular health in women. Circulation. Prevention, Health and Wellness Session. Originally published 11 November 2019. Abstract 140:A11410.

- 26.Rose Geoffrey. Oxford University Press; 1992. The strategy of preventive medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gómez-Pardo E., Fernández-Alvira J.M., Vilanova M. A comprehensive lifestyle peer group-based intervention on cardiovascular risk factors: the randomized controlled fifty-fifty program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:476–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.United States Department of Labor Occupational safety and health administration. Law and regulations. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs Available online at:

- 29.Centers for Disease Control Morbidity and mortality weekly report. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4822a1.htm June 11, 1999. Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: Improvements in Workplace Safety -- United States, 1900-1999. Available online at:

- 30.United States Department of Labor Occupational safety and health administration. https://www.osha.gov/dts/osta/otm/otm_vii/otm_vii_1.html#5 OSHA Technical Manual. Section VII: [Chapter 1]. Back Disorders and Injuries. Available online at:

- 31.The affordable care act and the prevention and public health Fund report to congress for FY2013. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/open/prevention/fy-2013-aca-pphf-report-to-congress.pdf Available online at:

- 32.Anderko L., Roffenbender J.S., Goetzel R.Z. Promoting prevention through the affordable care act: workplace wellness. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E175. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Workplace health promotion. Worksite health ScoreCard. https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/initiatives/healthscorecard/index.html Available online at:

- 34.American Heart Association Workplace health achievement recognitions. https://www.heart.org/en/professional/workplace-health/workplace-health-achievement-index/workplace-health-achievement-recognitions Available online at:

- 35.American Heart Association The American heart association’s workplace walking program Kit. https://cpr.heart.org/en/training-programs/workforce-training/osha-and-aha-alliancehttp://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/WorkplaceWellness/WorkplaceWellnessResources/The-American-Heart-Associations-Worksite-Wellness-Kit_UCM_460433_Article.jsp#.Xh8hlTNKiUl Available online at:

- 36.Osondu C.U., Aneni E.C., Valero-Elizondo J. Favorable cardiovascular health is associated with lower health care expenditures and resource utilization in a large US employee population: the baptist health south Florida employee study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;S0025–6196(17) doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.12.026. 30088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fabius R., Loeppke R.R., Hohn T. Tracking the market performance of companies that integrate a culture of health and safety: an assessment of corporate health achievement award applicants. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58:3–8. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Estruch R., Ros E., Salas-Salvadó J. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:e34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aldana S.G., Greenlaw R., Diehl H.A., Englert H., Jackson R. Impact of the coronary health improvement project (CHIP) on several employee populations. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:831–839. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldana S.G., Greenlaw R.L., Diehl H.A. The effects of a worksite chronic disease prevention program. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(6):558–564. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000165743.18570.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song Z., Baicker K. Effect of a workplace wellness program on employee health and economic outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2019;321(15):1491–1501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reif J., Chan D., Jones D., Payne L., Molitor D. Effects of a workplace wellness program on employee health, health beliefs, and medical use: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):952–960. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volpp K.G., John L.K., Troxel A.B., Norton L., Fassbender J., Loewenstein G. Financial incentive–based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300(22):2631–2637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halpern S.D., French B., Small D.S. Randomized trial of four financial-incentive programs for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(22):2108–2117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kivimäki M., Nyberg S.T., Batty G.D. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2012;380:1491–1497. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60994-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piepoli M.F., Abreu A., Albus C. Update on cardiovascular prevention in clinical practice: a position paper of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27:181–205. doi: 10.1177/2047487319893035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]