Abstract

Knowing the patient's current cardiovascular disease (CVD) status, as well as the patient's current and future CVD risk, helps the clinician make more informed patient-centered management recommendations towards the goal of preventing future CVD events. Imaging tests that can assist the clinician with the diagnosis and prognosis of CVD include imaging studies of the heart and vascular system, as well as imaging studies of other body organs applicable to CVD risk. The American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) has published “Ten Things to Know About Ten Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors.” Similarly, this “ASPC Top Ten Imaging” summarizes ten things to know about ten imaging studies related to assessing CVD and CVD risk, listed in tabular form. The ten imaging studies herein include: (1) coronary artery calcium imaging (CAC), (2) coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), (3) cardiac ultrasound (echocardiography), (4) nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), (5) cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), (6) cardiac catheterization [with or without intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or coronary optical coherence tomography (OCT)], (7) dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) body composition, (8) hepatic imaging [ultrasound of liver, vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE), CT, MRI proton density fat fraction (PDFF), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)], (9) peripheral artery / endothelial function imaging (e.g., carotid ultrasound, peripheral doppler imaging, ultrasound flow-mediated dilation, other tests of endothelial function and peripheral vascular imaging) and (10) images of other body organs applicable to preventive cardiology (brain, kidney, ovary). Many cardiologists perform cardiovascular-related imaging. Many non-cardiologists perform applicable non-cardiovascular imaging. Cardiologists and non-cardiologists alike may benefit from a working knowledge of imaging studies applicable to the diagnosis and prognosis of CVD and CVD risk – both important in preventive cardiology.

Keywords: Coronary artery calcium imaging (CAC), Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), Cardiac ultrasound, Echocardiography, Nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), Cardiac catheterization, Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), Coronary optical coherence tomography (OCT)

What is already known about this subject?

-

•

The American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) has published “Ten Things to Know About Ten Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk Factors,” [1,2] which summarizes major CVD risk factors, accompanied by sentinel reviews or guidelines relative to ten important CVD risk factors.

-

•

Assessing existing CVD and CVD risk through imaging is commonly used to stratify CVD risk and influence CVD prevention management. Diagnostic and prognostic imaging studies of the heart and other body organs help clinicians with management decisions to prevent future CVD events.

What are the new findings in this manuscript?

-

•

The “ASPC Top Ten Imaging” summarizes ten things to know about ten important CVD-related imaging studies (listed in a tabular format).

-

•

Non-cardiologists (e.g., primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, gynecologists, endocrinologists, obesity medicine specialists, lipidologists, diabetologists etc.) may benefit from an overview of CVD-related imaging studies commonly performed by cardiologists. Cardiologists may benefit from an overview of imaging studies beyond the heart, but applicable to global preventive cardiology – which are imaging studies often performed by non-cardiologists.

-

•

In addition to the “Top Ten” things to know about CVD imaging studies, citations are listed in the applicable tables to provide the reader more in-depth resources (e.g., illustrative guidelines and other references) pertaining to each imaging category.

1. Introduction

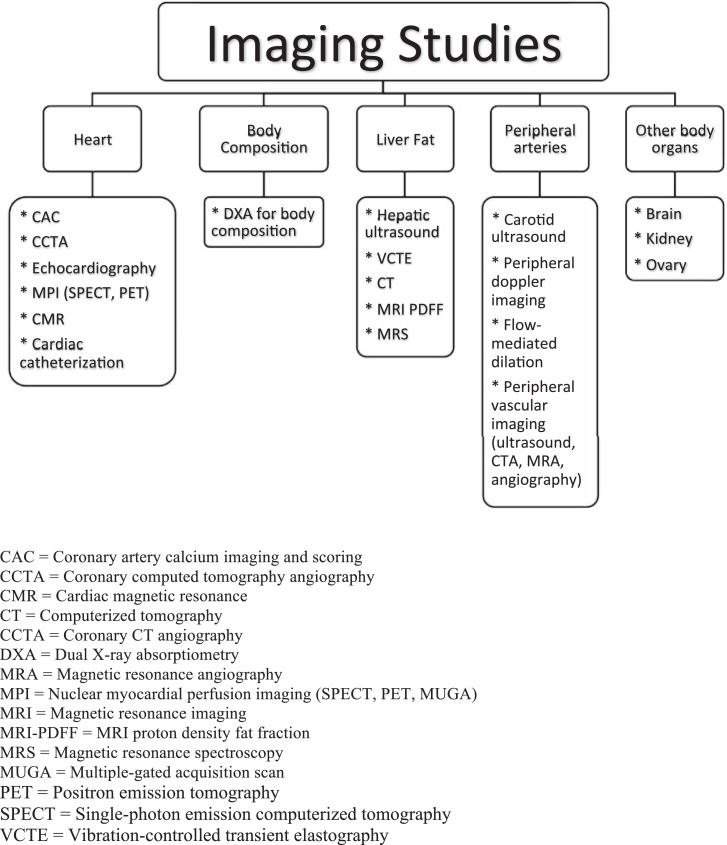

The intent of the “American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC) Top Ten Imaging” is to help primary care clinicians and cardiology specialists keep up with the ever-increasing pace of diagnostic and prognostic imaging studies applicable to preventive cardiology. Imaging studies focused on the heart are often performed by cardiologists and/or radiologists and help with diagnosis and prognosis. Other imaging studies may also help in CVD risk stratification, and include imaging studies of the peripheral vasculature, body fat, liver, brain, kidney, and ovary. The “ASPC Top Ten Imaging” summarizes ten things to know about ten CVD-related imaging studies, listed in tabular formats. These ten imaging studies include: (1) coronary artery calcium (CAC) imaging and scoring, (2) coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), (3) cardiac ultrasound (echocardiography), (4) nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), (5) cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), (6) cardiac catheterization [with or without intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or coronary optical coherence tomography (OCT)], (7) dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) body composition, (8) hepatic imaging [ultrasound of liver, vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE), CT, MRI proton density fat fraction (PDFF), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)], (9) peripheral artery / endothelial function imaging (e.g., carotid ultrasound, peripheral doppler imaging, ultrasound flow-mediated dilation, other tests of endothelial function and peripheral vascular imaging) and (10) images of other body organs applicable to preventive cardiology (brain, kidney, ovary). (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Cardiac and other organ imaging relevant to preventive cardiology.

The intent is not to create a comprehensive discussion of all imaging studies applicable to CVD assessment. Nor is this document intended to be a comprehensive discussion of each imaging study. Rather, the intent is to focus on common imaging studies having implications for preventive cardiology. For a more in-depth discussion of these CVD imaging studies, this “ASPC Top Ten Imaging” provides updated guidelines and other selected references in the applicable tables.

2. Purpose of cardiac imaging

-

•

Cardiac imaging helps assess the degree of CVD, which is important in stratifying current CVD risk and determining management strategies toward preventing future CVD events. CVD risk factor management is often more aggressive and often prioritized to patients most likely to benefit, which often includes those with diagnosed CVD or otherwise at increased CVD risk.

-

•

Cardiac imaging may help further stratify patients at intermediate CVD risk, as otherwise determined by coronary heart disease (CHD) risk scores [1,3].

-

•

Cardiac imaging results may help decide who to treat, what to treat, and when to treat, as well as how aggressively to treat atherosclerotic lesions (e.g., revascularization) and/or CVD risk factors (e.g., dyslipidemia, hypertension, hyperglycemia) – all for the purpose of helping prevent future CVD events.

-

•

Extracardiac images of other body organs such as body composition (android and visceral fat) liver (hepatic fat), brain (cerebral vascular disease), kidney (vascular abnormalities), ovary (polycystic ovarian syndrome) and peripheral vasculature (endothelial dysfunction) can also provide insight regarding other CVD risk factors and need for potential treatment of these CVD risk factors.

3. Appropriate use [4,5]

-

•

The choice of cardiac imaging studies should be based upon established “Appropriate Use” criteria, [4,5] and individual patient presentation.

-

•

Appropriate imaging studies are those where the clinical benefits and value in an individual patient exceed the risk (Reference Chart 1) and cost, through providing clinically meaningful information about CVD and CVD risk, beyond clinical judgment alone.

-

•

Appropriate use of imaging studies includes procedures most likely to provide safe and definitive answers to the diagnostic questions raised, and least likely to prompt further imaging studies and invasive downstream procedures, irrespective of the initial imaging study results. In other words, in the interest of limiting the risks and costs of multiple imaging procedures, the choice of cardiac imaging procedure should focus on which procedure is likely to provide the greatest amount of actionable information applicable to the individual patient, in the safest manner possible.

-

•

Clinicians should be cautious and judicious in cardiac imaging studies in patients at low CVD risk, especially for imaging studies that have low specificity in patients at low CVD risk. Low specificity cardiac imaging in low CVD risk patients may often lead to false positive results. False positive findings on cardiac imaging may needlessly prompt more invasive, more costly, and potentially unnecessary additional testing and/or procedures, resulting in more health risk than benefit.

-

•

Selecting the most appropriate imaging test should take into consideration whether the patient is symptomatic or asymptomatic. Performing cardiac imaging studies with low selectivity in asymptomatic patients at low CVD risk has a higher risk of false positive findings than cardiac imaging studies with high selectivity in symptomatic patients at high CVD risk (Reference Chart 2).

-

•

Procedures having the most robust evidence to support use in screening for coronary artery disease in asymptomatic individuals include family history assessment for premature CVD, CVD risk factor assessment, and CVD and CHD risk scores. [1,24] Additional diagnostic procedures having evidenced-based support in screening asymptomatic individuals include CAC scoring, with some suggestion that carotid artery ultrasound can assist with CVD risk stratification. [24] Little evidence supports the routine clinical use of cardiac resting or stress imaging testing in asymptomatic patients. Possible exceptions (albeit with lower level evidence as noted per guidelines) include coronary CTA among selected, asymptomatic individuals at high CVD risk, or stress electrocardiogram in physically inactive patients at higher CVD risk who plan to start a rigorous physical exercise program. [24]

-

•

The selection of the most appropriate imaging test should be based upon the patient presentation. A common clinical scenario that directly impacts management directed at CVD prevention is the evaluation of chest pain, which typically involves various disease endotypes: (1) angina due to obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) with fractional flow reserve ≤0.80; (2) microvascular angina with coronary flow reserve <2.0 and/or index of microvascular resistance >25); (3) microvascular angina due to small vessel spasm (which can be assessed by intracoronary acetylcholine administration); (4) vasospastic angina due to epicardial coronary spasm (which can be assessed by intracoronary acetylcholine administration); and (5) noncoronary etiology (i.e., patients found to have normal coronary anatomy and normal function via cardiac imaging). [6]

-

•

While “ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery” (INOCA) disease can be assessed by the invasive coronary reactivity tests described above, common noninvasive cardiac imaging studies applicable to coronary microvascular disease include PET, CMR, and echocardiography, with invasive imaging studies including coronary flow reserve via coronary angiography. [7] Similarly, causes of “myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries” (MINOCA) include cardiac microvascular disease (i.e., microvascular plaque, thrombosis), coronary vasospasm, and coronary artery dissection. [8] Imaging studies to assess MINOCA include coronary angiography with or without intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography, as well as possibly intracoronary acetylcholine if coronary spasm is suspected. [9,8,10] Yet other cardiac imaging studies to help assess MINOCA include echocardiography, [10] with PET and CMR useful to assess coronary microvascular dysfunction. [11,12]

-

•Most instances of coronary artery disease involve macrovascular disease leading to obstruction and often clinically manifest by angina and myocardial infarction. Even among patients with coronary microvascular disease, most such patients also have macrovessel atherosclerosis. [7] However, a sole focus on coronary macrovascular disease may underdiagnose cardiac disease in patients with coronary microvascular disease as often occurs in women. [7] Therefore, selecting the most appropriate imaging study is best determined by the patient presentation, and the information reasonably derived by the imaging study performed on an individual patient.

-

•

CAC added to SPECT or PET may help further identify coronary artery plaque and better stratify risk [25,26]

-

•

CCTA added to CAC scoring may help improve the assessment of total plaque burden and better discriminate risk of death and/or myocardial infarction among symptomatic patients with suspected coronary artery disease. [27,28]

-

•

Although it may have low specificity, CAC scoring is illustrative of a cardiac imaging study of high sensitivity, limited invasiveness, and low radiation exposure (Reference Charts 1 & 2). CAC is often performed in asymptomatic patients to help stratify CVD risk (see Section 1 and Table 1 below). [10,7]

Reference Chart 1.

Invasiveness and patient radiation exposure regarding various imaging procedures. Radiation exposure for some procedures may be less than listed via use of ultra-low dose radiation protocols involving stress-only imaging. Some common diagnostic procedures are listed at the bottom of the table for reference/illustrative purposes. [37, 38].

| Procedure | Invasiveness | Patient radiation exposure* |

|---|---|---|

| Contemporary coronary artery calcium CT (CAC) | Noninvasive, no contrast | ~ 1 mSv [39, 40, 41] |

| Contemporary coronary CT angiography (CCTA) | Requires injection of contrast material (i.e., iodine) | 1.0 - 5 mSv⁎⁎ [42, 43, 44, 45] |

| Cardiac ultrasound / echocardiogram | Noninvasive. If unable to physically exercise, then dobutamine may be injected to mimic exercise. May include contrast (i.e., agitated saline or commercial ultrasound contrast agents). [46] | 0.00 mSv (no radiation) |

| Nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) | ||

| • SPECT perfusion imaging | Intravenous administration of nuclear contrast with imaging at rest, followed by walking on a treadmill with another injection afterwards of nuclear contrast. If unable to physically exercise, then an A2A adenosine receptor agonists (i.e., regadenoson coronary vasodilator for cardiolite stress test) can be injected to mimic exercise | 10 -15 mSv with technetium-99 [48]25 – 30 mSv with thallium-201 [48] (seldom used in current clinical practice) |

| • PET perfusion imaging | Requires injection of radiotracer (e.g., 50 mCi of 82rubidium or 20 mCi of 13ammonia for rest and stress perfusion). [47] If unable to physically exercise, then pharmacologic stress testing can be achieved via the vasodilators regadenoson, adenosine, dipyridamole, or inotropic/chronotropic agents such as dobutamine with or without atropine | 4 mSv with 82rubidium or 13ammonia [49] (older reports suggest higher radiation exposure) [48, 47] |

| • MUGA ventricular imaging (seldom use in current clinical practice) | Requires injection of radiotracer | 5 – 10 mSv with technetium-99m-pertechnetate [50] |

| CMR | Most cardiac protocols involve injection of contrast (i.e., gadolinium) | 0.00 mSv (no radiation) |

| Cardiac catheterization | Cardiac catheterization involves insertion of a catheter tube into the artery or vein in the groin, neck, or arm, which is then threaded into the heart. | 2 – 7 mSv for diagnostic cardiac catheterization [51]10 mSv or higher for interventional catheterization [52, 52] |

| DXA total body composition scan | Noninvasive | ≤ 0.001mSv for typical body composition (minimal radiation; technicians not required to wear garments to protect from radiation) |

| Hepatic imaging• Ultrasound of liver• VCTE/fibroscan• CT• MRI-PDFF• MRS |

NoninvasiveNoninvasiveMay involve injection of contrast (e.g., iohexol)May involve injection of contrast (i.e., gadolinium)May involve injection of contrast (i.e., gadolinium) |

0.00 mSv (no radiation)0.00 mSv (no radiation)3.0 mSv0.00 mSv (no radiation)0.00 mSv (no radiation) |

| Carotid ultrasound, peripheral doppler imaging, ultrasound flow-mediated dilation, and pulse amplitude tonometry Fingertip infrared light transmission photoplethysmograpy for endothelial function | Noninvasive | 0.00 mSv (no radiation) |

| Daily background radiation | 0.007 mSv | |

| Yearly background radiation | 3.0 mSv | |

| Roundtrip Transatlantic Flight | 0.100 mSv | |

| Chest X-ray | 0.02 – 0.1 mSv | |

| Mammogram | 0.40 mSv | |

| DXA AP spine scan | 0.001 – 0.004 mSv | |

| Older body PET / CT scans | 15 - 25.0 mSv | |

| Older whole body CT scans | 10 - 20 mSv | |

The standard measure of radiation is Sievert (Sv) or millisievert (mSv) or microsievert (uSv) units where 1 Sv = 1000 mSv = 1,000,000 uSv. Humans have natural daily radiation exposure of about 0.007 mSv from soil, rocks, radon, and outer space.

Quality CCTA images with ~ 1 mSv radiation exposure can sometimes be obtained in younger patients without overweight/obesity, or when utilizing low-dose CCTA protocols. [42, 43, 53]

CMR = Cardiac magnetic resonance,

CT = computerized tomography,

DXA = Dual x-ray absorptiometry,

FFR = Fractional flow reserve,

IVUS = Intravascular ultrasound,

MRI = Magnetic resonance imaging,

MRI-PDFF = MRI proton density fat fraction,

MRS = Magnetic resonance spectroscopy,

MUGA = Multiple-gated acquisition scan,

OCT = Optical coherence tomography,

PET = Positron emission tomography,

SPECT = Single-photon emission computerized tomography,

VCTE = Vibration-controlled transient elastography.

Reference Chart 2.

| Imaging Test | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomically significant coronary artery disease* | ||

| Coronary Calcium Imaging/Score | 98% | 40% |

| Exercise electrocardiogram | 58% | 62% |

| Stress echocardiogram (Echo) | 85% | 82% |

| Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) | 96% | 82% |

| Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) | 87% | 70% |

| Positron emission tomography (PET) | 90% | 85% |

| Stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) | 90% | 80% |

| Functionally significant coronary artery disease⁎⁎ | ||

| Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) | 93% | 53% |

| CCTA with fractional flow reserve (FFR) | 85% | 78% |

| Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) | 73% | 83% |

| Positron emission tomography (PET) | 89% | 85% |

| Stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) | 89% | 87% |

Anatomically significant CAD is sometimes defined as > 50% stenosis of the left main coronary artery, 70% stenosis of any major coronary vessel, or 30 – 70% stenosis with fractional flow reserve of ≤ 0.8. [56]

Heart function imaging involves assessing blood flow within coronary arteries. The significance of a coronary artery obstruction can be assessed by measuring (directly or virtually) the pressure differential before and after a coronary artery stenosis (fractional flow reserve). The cut-off point for functionally significant CAD is often reported as ≤ 0.8, with other flow coronary blood flow metrics being dependent on the individual imaging technique. [56, 57, 42].

Table 1.

Ten things to know about computerized tomography coronary artery calcium (CAC) measurements.

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2021 National Lipid Association Scientific Statement on Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring [60]2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol [64]2018 Coronary Calcium Score and Cardiovascular Risk [41]2020 Coronary Calcium StatPearls [58]2018 Coronary Artery Calcium: If Measuring Once Is Good, Is Twice Better? [69] |

*CHD = coronary heart disease (e.g., myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease)

*ASCVD = Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is often defined as acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, stable or unstable angina, coronary or other arterial revascularization, stroke, transient ischemic attack, peripheral artery disease, and aortic aneurysm – all of atherosclerotic origin [64].

4. Cardiac exercise stress testing

Preventive cardiology incorporates both primary and secondary CVD prevention. Understanding the extent of CVD disease in both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients helps the clinician better recommend therapeutic interventions towards the goal of preventing future CVD events. Non-invasive cardiac imaging studies in patients with stable coronary obstructive symptoms (stable ischemic heart disease or “chronic coronary syndrome”) can help diagnose ischemic heart disease and are often performed prior to cardiac catherization. [29] In most cases, the use of imaging studies to diagnose ischemia is performed with exercise testing, such as through use of a treadmill or bicycle. Imaging with exercise testing can enhance accuracy of the stress testing, especially in patients with non-interpretable electrocardiograms. The purpose of physical exercise coupled with imaging studies is to evoke coronary (macro and micro) blood flow, and promote other functional cardiovascular responses, during times of greater oxygen and nutrient demands of the heart (i.e., during times of “stress” such as via exercise).

Thus, stable patients suspected of myocardial ischemia who are able to exercise, and who have interpretable ECG/s, are best “stressed” via physical exercise (i.e., treadmill or bicycle). Incorporating exercise in a cardiac “stress test” allows for non-imaging assessment of hemodynamic response (i.e., heart rate, blood pressure), ST- segment analysis, and onset of dysrhythmias. Stress electrocardiography alone is reported to have sensitivity and specificity of 50 – 80%, depending on the source and patient population studied. [30,29] (Reference Chart 2) In patients with ECG abnormalities (e.g., left bundle branch block, changes consistent with left ventricular hypertrophy, ST-T wave changes), the addition of heart imaging (e.g., echocardiography or MPI such as SPECT or PET) to exercise cardiac stress testing may help identify and quantify cardiac dysfunction and/or ischemia.

A patient at low to intermediate CVD risk with a negative cardiac stress test [i.e., demonstrating no chest pain and no electrocardiographic evidence of ischemia after undergoing standard exercise protocols and achieving ten metabolic equivalents (METS)] is at low risk for future CVD events and or CVD mortality. [31] However, among patients with exercise treadmil stress tests suggesting possible ischemia, then depending on CVD risk, only 39% may subsequently have positive imaging/angiogram evidence of atherosclerosis. [32] Thus, among patients presenting with intermediate likelihood of CVD, exercise cardiac stress testing (i.e., treadmill or bicycle) plus cardiac imaging (e.g., echocardiogram, MPI, or PET) is more specific than an exercise stress test alone. Furthermore, in patients with uninterpretable ECG's, or in patients unable to exercise, and/or who undergo pharmacologic cardiac stress testing, concomitant heart imaging studies are often required.

Patients unable to undergo adequate exercise stress testing (e.g., relative immobility due to deconditioning, frailty, obesity, stroke, orthopedic impairments, neuropathy, lung disease) may require pharmacologic stress testing. Examples of pharmacologic stress agents include regadenoson (A2a receptor agonist), adenosine (nonselective adenosine receptor agonist), dipyridamole (nonselective vasodilator and antiplatelet agent that raises adenosine levels), and dobutamine (sympathomimetic). Regadenoson is the most common pharmacologic vasodilator used for pharmacological SPECT stress testing. [33,34]

5. Imaging studies

Safety considerations of imaging studies include the degree of their invasiveness and amount of radiation exposure (Reference Chart 1). [35] Invasiveness is defined here as access to the body via inserting a diagnostic device or injecting imaging media through incision or percutaneous puncture. Potential radiation exposure may be especially important in cardio-oncology. [36]

The most invasive CVD imaging study is cardiac catheterization. (Reference Chart 1) Cardiac catheterization remains the initial imaging procedure of choice for patients whose history, signs, symptoms and/or CVD imaging test results suggest high risk for myocardial dysfunction (e.g., high CVD risk features on a cardiac exercise stress test). This is especially true if it is anticipated the cardiac catheterization may be accompanied by a therapeutic intervention (i.e., PCI, thrombectomy, atherectomy). Complications of cardiac catheterization include bruising/bleeding at the catheter insertion site, myocardial infarction, stroke and other thrombotic complications, vascular injury, cardiac dysrhythmias, infection, contrast induced nephropathy, or allergic reaction to the contrast dye (i.e., iodine).

The invasiveness, radiation exposure, and cost associated with cardiac catheterization have prompted development of alternative noninvasive imaging procedures, many having limited radiation exposure. Radiation exposure is important because ionizing radiation contributes to cell death, cellular injury, or cell mutation potentially leading to cancer. (Non-ionizing radiation includes electric and magnetic fields, radio waves, microwaves, infrared, ultraviolet, and visible radiation, which have insufficient energy to ionize atoms or molecules.) The degree of radiation exposure is dependent on the dose of tracer infused, length of the imaging procedure, and the number of times the procedure is performed. Examples of CVD imaging studies with limited invasiveness include CAC, CCTA, & MPI. CVD imaging studies with limited invasiveness and no or minimal radiation exposure include CMR and ultrasound. (See Reference Chart 1)

5.1. Computerized tomography (CT) coronary artery calcium (CAC) [58]

A coronary artery calcium (CAC) score utilizes CT to assess the amount of calcium found in coronary arteries. Arterial calcium reflects vascular injury, inflammation, and repair. Coronary calcium is a marker of plaque burden. It is not a measure of plaque vulnerability to rupture or degree of coronary stenosis. Due to vessel remodeling early in atherosclerosis, enlargement of coronary arteries may occur, mitigating signs or symptoms of stenosis, despite substantial plaque burden. This pathogenic clinical scenario is often clarified by CAC. Other cardiac imaging (i.e., with exercise stress testing) are more appropriate for patients with angina and/or obstructive CAD. However, CAC is a non-invasive cardiac procedure that can assess plaque burden, that is best used in asymptomatic patients to help guide the need for further cardiac evaluation or help determine the timing and degree of aggressiveness in managing existing CVD risk factors. [29]

CAC scores may be increased with older age, men versus women for same age, metabolic syndrome, high blood glucose, high blood pressure, increased atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol burden, cigarette smoking, chronic kidney disease, and elevated C-reactive protein levels. [58] Assessment of coronary artery calcium is most often performed by multidetector computed tomography (MDCT); CAC does not require contrast. [41] The Agatston score reflects the total area of calcium deposits in coronary arteries, and the density of the calcium.

CAC Agatston Unit (AU) scores and coronary plaque burden can be categorized as: [59]

-

•

0: No identifiable calcified coronary atherosclerosis

-

•

1–100: Calcification suggestive of mild coronary atherosclerosis

-

•

100 to 400: Calcification suggestive of moderate coronary atherosclerosis

-

•

400 or above: Calcification suggestive of severe coronary atherosclerosis

-

•

1000 or above: Calcification suggestive of extreme coronary atherosclerosis

In a Scientific Statement from the National Lipid Association, CAC scoring: [60]

-

•

Informs ASCVD risk discrimination and reclassification

-

•

Aids in ASCVD risk prediction, regardless of race, gender, or ethnicity

-

•

Aids the clinician to allocate statin therapy based on ASCVD risk

-

•

May inform decision-making about add-on therapies to statins, especially if CAC scores are very high

-

•

Aids decision-making about aspirin and anti-hypertensive therapy

Reference Chart 1 describes the relative radiation exposure with CAC. Table 1 lists ten things to know about computerized tomography coronary artery calcium (CAC) measurements.

5.2. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA)

Atherosclerotic progression begins with early reversible subendothelial lipid accumulation, early inflammation, and minimal fibrosis. Further atherosclerotic progression may lead to lipid plaque, chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and perivascular adipose tissue remodeling – which if untreated, may ultimately become irreversible. [78] CCTA can measure lipid rich plaque, [79] as well as perivascular fat and inflammation. [80,81]

Clinically, CCTA is a cardiac imaging study utilizing CT that is often used to quantify coronary atherosclerotic burden. When combined with FFR, CCTA can help determine the functional significance of stenotic lesions. With use of an iodine intravenous contrast agent, CCTA can visualize the coronary artery lumen. CCTA is sensitive for anatomically significant CAD (e.g., obstructive CAD and nonobstructive calcified plaques) and reasonably sensitive for functionally significant CAD. However, CCTA is not specific for functionally significant CHD. (Reference Chart 2) [29] Reference Chart 1 describes the relative radiation exposure with CCTA. Table 2 lists ten things to know about coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA).

Table 2.

Ten things to know about coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) [29].

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2021 Epicardial fat and coronary artery disease: Role of cardiac imaging [81]2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: Recommendations for cardiovascular imaging [29]2018 Coronary CT Angiography and 5-Year Risk of Myocardial Infarction [84]2015 Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease [87]2015 Cardiac CT vs. Stress Testing in Patients with Suspected Coronary Artery Disease: Review and Expert Recommendations [88] |

5.3. Cardiac ultrasound (echocardiography)

Echocardiography utilizes ultrasound waves (sound wave range beyond that audible by humans) to provide hemodynamic information about heart function. When accompanied by stress testing, echocardiography is often used to assess myocardial ischemia (i.e., coronary artery atherosclerosis), left ventricular function (i.e. heart failure, cardiomyopathy) and structural heart disease (i.e., valvulopathy, congenital heart disease, aneurysm, cardiac tumor, pericarditis, endocarditis, aortic dissection, heart chamber thrombosis). [89] Approaches to echocardiography include transthoracic chest wall approach or transesophageal approach. Types of echocardiography include: [90,89]

-

•

M-mode: “Motion mode” generates tracing images rather than picture images.

-

•

Doppler (previously known as B or “Brightness-mode”): Assesses blood flow and can be characterized as continuous-wave, pulsed-wave or color-flow. Continuous and pulse wave doppler echocardiography images allow for calculated flow velocity, as well as estimates for volume and pressure gradients across heart valves.

-

•

2-D (two-dimensional) echocardiography: Provides cross-sectional real-time motion images of the heart

-

•

3-D (three-dimensional) echocardiography: Able to view real-time motion of the heart via 3-D images

Stress echocardiography is reasonably sensitive and specific for diagnosing coronary artery disease in symptomatic patients. (Reference Chart 2). However, despite its noninvasive safety, “routine” echocardiograms should not be performed in asymptomatic patients (“inappropriate use”), as this may lead to false positive or equivocal findings, resulting in unnecessary downstream consultations and procedures. [91] Reference Chart 1 describes how cardiac ultrasound results in no radiation exposure. Table 3 lists ten things to know about echocardiography.

Table 3.

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2021 Novelties in 3D Transthoracic Echocardiography [97]2021 Usefulness of Stress Echocardiography in the Management of Patients Treated with Anticancer Drugs [98]2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: Recommendations for cardiovascular imaging [29]2020 Echocardiography update for primary care physicians: a review [89]2004 Understanding the echocardiogram [90] |

5.4. Nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) [29]

Nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging through Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) utilizes small amounts of nuclear tracer (i.e., the isotope technetium-99 or thallium-201) injected into the blood to assess myocardial segments that do not take up the tracer (i.e., damaged myocardium) or areas with delayed uptake of the tracer (i.e., ischemic myocardium). SPECT can also help assess the patency of grafted blood vessels after coronary bypass. Techetium-99 is a radiotracer often attached to a small protein (sestamibi). Thallium-201 is typically supplied as thallous chloride. Technetium-99 has lower radiation exposure and is preferred; Thallium-201 is rarely used in current clinical practice. (Reference Chart 1) The radiotracers are generally injected into the blood with imaging occurring at rest, or with exercise (e.g., “nuclear stress test,” “exercise thallium scan,” “exercise technetium-99 sestamibe scan”), or both. For patients unable to physically exercise, then an A2A adenosine receptor agonist (i.e., regadenoson coronary vasodilator for cardiolite stress test) can be injected as an alternative to exercise.

A positron emission tomography (PET) scan of the heart utilizes a radiotracer (i.e., often 82rubidium or 13ammonia for rest and stress perfusion). [47] Uptake of the radiotracer by the myocardium is proportional to myocardial blood flow. Thus, coronary flow reserve can be added to PET to improve CVD risk assessment. Strengths of PET MPI include high diagnostic accuracy, safety with low radiation exposure (lower than SPECT), efficient with 5-min image acquisition times (may take only 30 minutes to perform), ability to accommodate ill or higher-risk patients, ability to assess patients with large body habitus, and ability to assess non-obstructive coronary microvascular dysfunction. [99] PET is often used as a noninvasive imaging test to assess coronary flow reserve (Table 5), that may assist with diagnosis, prognosis, and management of patients with a range of ASCVD, including both multivessel obstructive CAD and diffuse coronary microvascular dysfunction. Cardiac microvascular dysfunction may be especially clinically relevant in women, patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, cardio-oncologic complications, and inflammatory-related disease. [100,101] Patients with stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD) vary in their cardiac anatomy and function. In addition to obstructive coronary lesions, it is estimated that 3 – 4 million men and women in the US have symptoms of myocardial ischemia with no evidence of obstructive CAD. [102] Along with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, other cardiac conditions that may occur more often in women include Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, cerebral small-vessel disease, preeclampsia, pulmonary arterial hypertension, endothelial dysfunction in diabetes, diabetes cardiomyopathy, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis, and small vessel cardiac disease – which suggests a common etiologic linkage of these cardiac conditions. [103] An illustrative strategy that may help balance safety and diagnostic yield would be to employ ultra-low dose radiation protocols involving stress-only imaging, with SPECT or PET used when possible for patients undergoing MPI. [104]

Table 5.

Ten things to know about cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR).

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2021 Cardiovascular Imaging in Obesity [121]2020 Standardized cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) protocols: 2020 update [132]2020 Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) Position Paper on clinical indications for cardiovascular magnetic resonance [133]2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: Recommendations for cardiovascular imaging [29] |

A multiple-gated acquisition (MUGA) scan involves utilizes a radiotracer (e.g., technetium-99m-pertechnetate) attached to red blood cells to evaluate the size of the chamber of the heart. MUGA was historically among the most common cardiac imaging studies for measuring left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) MUGA scans are currently seldom used in favor of other imaging studies such as echocardiography and CMR.

Reference Charts 1 & 2 describe the radiation exposure using MPI techniques, as well as their sensitivity and selectivity. Table 4 lists ten things to know about nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging.

Table 4.

Ten things to know about nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI).

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2021 Nuclear cardiology: state of the art [111]2021 Nuclear Medicine SPECT Scan Cardiovascular Assessment, Protocols, and Assessment [112]2020 Review of cardiovascular imaging in the Journal of Nuclear Cardiology 2019: Positron emission tomography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance [113]2020 Noninvasive Imaging of Ischemic Heart Disease and Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Women. [114]2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: Recommendations for cardiovascular imaging [29] |

5.5. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR)

CMR is an imaging study that utilizes magnetic, radio frequency waves (not ionizing radiation) to create cross sectional/2-dimentional, 3-dimentional, and even 4-dimentional images. CMR can help assess valvular heart disease, ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathies, congenital heart disease, cardiac tumors, and pericardial disease (pericarditis). [115,116,117] CMR can also measure subendocardial and subepicardial perfusion to assess for potential coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease. [118] Determination of the value of CMR for imaging of cardiac anatomy such as MINOCA is evolving. [119] Among examples where stress CMR may be cost effective include patients with stable ischemic heart disease and non-diagnostic coronary CT angiography. [120] Utilization of CMR for cardiac anatomic disease may be more limited in the US relative to other countries.

Reference Chart 1 describes how CMR results in no radiation exposure. Stress CMR has a high sensitivity for detecting anatomically and functionally significant CAD (e.g., obstructive CAD) (Reference Chart 2), but is less specific for anatomically significant CHD (Reference Chart 2). In general, CMR is commonly used to evauate cardiomyopathy, and occasionally as an alternative myocardial perfusion tool in the setting of a stress test.

Table 5 lists ten things to know about CMR.

5.6. Cardiac catheterization [with or without intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or coronary optical coherence tomography (OCT)]

Cardiac catheterization is an invasive procedure that involves inserting a catheter into an artery or vein in the groin, neck, or arm, which is then threaded into the heart. Contrast (e.g., iodine or gadolinium) dye is injected into the heart and vessels to assess narrowing or blockages of coronary arteries and assess cardiac structure (e.g., heart valves, left ventricular function). In addition to the imaging part of the procedure, catheterization may also allow for therapeutic PCI, repairing of septal defects, balloon valvuloplasty, or heart biopsy. Reference Chart 1 describes the invasiveness and relative radiation exposure of cardiac catheterization.

Fractional flow reserve (FFR) is often obtained via cardiac catheterization and represents the pressure differential before and after a coronary artery stenosis. As noted in Reference Chart 2, the cut-off point for functionally significant CAD is often reported as < 0.8. [30] Thus, anatomically significant CAD is sometimes defined as > 50% stenosis of the left main coronary artery, 70% stenosis of any major coronary vessel, or 30–70% stenosis with fractional flow reserve of < 0.8. [30]

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) is an imaging technique that may be conducted during cardiac catheterization that utilizes sound waves to assess both intramural (impinging on the coronary lumen) and extramural (ectatic) atherosclerotic plaque. It is performed using a dedicated catheter with ultrasound-based technology to provide a cross sectional image with a 360° view of the vessel. [134] Coronary optical coherence tomography (OCT) is an intracoronary artery diagnostic imaging study that can be performed during cardiac catheterization. Coronary OCT can help visualize the microstructure of normal and diseased arteries and can identify calcified plaque and neointima formation after stent placement. [135]

While OCT may provide better image resolution of the coronary arteries, IVUS has greater imaging penetration than OCT, where large lipid-rich plaques may impair the ability to image the vessel border with OCT. [136] OCT requires contrast (often iodine-based), [137]which increases the risk of contrast induced nephropathy. Alternative OCT contrasts such as dextran may help avoid acute kidney injury. [138] Contrast induced nephropathy [136] is a poor prognostic factor that often delays hospital discharge and increases costs. [139] In short, OCT may be superior to IVUS in assessing the cause of stent failure, calcific coronary disease, and MINOCA. Conversely, [139] IVUS may be superior in patients with left main coronary artery disease, renal dysfunction, aorto-coronary ostial lesions, and chronic total occlusion. [139]

Another example of an intra-coronary imaging study includes near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). [140] Other functional intra-coronary measures that can be obtained during cardiac catheterization intra-coronary include instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR), [141] index of microvascular resistance (IMR), [142] and minimal luminal area (MLA). [143]

Table 6 lists ten things to know about cardiac catheterization [with or without intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or coronary optical coherence tomography (OCT)].

Table 6.

Ten things to know about cardiac catheterization.

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2020 Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease [146]2020 Intravascular Ultrasound StatPearls. [134]2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: Recommendations for cardiovascular imaging [29]2019 Safety and Risk of Major Complications with Diagnostic Cardiac Catheterization [148]2018 Coronary Optical Coherence Tomography [135] |

5.7. Dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) body composition

DXA is commonly used to assess bone mineral density (BMD) in patients at risk for osteoporosis. In women, trabecular volumetric BMD may be independently and inversely related to CAC scores, [149] while cortical volumetric BMD may be independently and directly related to CAC scores. [150] While not often done clinically, emerging research suggests that DXA can assess abdominal aortic calcification, which is a risk factor for ASCVD. [151] Increased abdominal aortic calcification is associated with increased risk for osteoporosis [152].

DXA is also a “gold standard” to assess body composition. Many DXA scanners can assess percent body fat, android fat, visceral fat, lean body mass, and bone mass. DXA scans also provide the clinician and patient colorful images with detailed descriptions of personalized information regarding body composition. Reference Chart 1 describes the invasiveness and relative radiation exposure of DXA. The risk of radiation exposure is often about 5% of a standard chest X-ray, about the same as an intercontinental flight; technicians do not have to wear radiation protective garments.

Patients with increased android fat (i.e., abdominal and visceral adiposity) are at increased CVD risk. DXA assessment of body composition can be obtained for a cross-sectional assessment at a point in time, and for longitudinal assessment after implementation of healthful nutrition, physical activity, anti-obesity pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery. These longitudinal DXA assessments in patients at higher CVD risk are not influenced by treatments such as statins. Table 7 lists ten things to know about dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) body composition.

Table 7.

Ten things to know about dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) body composition.

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2021 Obesity Medicine Association Obesity Algorithm [101]2017 Visceral fat reference values derived from healthy European men and women. [155]2015 Does Visceral Fat Estimated by DXA Independently Predict Cardiometabolic Risk in Adults? [156]2014 Imaging Body Fat: Techniques and Cardiometabolic Implications [157] |

5.8. Hepatic imaging for NAFLD

As with obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a factor associated with increased CVD risk. [158] (1) NAFLD encompasses the spectrum of fatty liver not related to alcohol consumption (e.g., fatty liver and hepatosteatitis). While NAFLD can be cause by genetics, infectious diseases, and various medications, NAFLD is most often associated with, or caused by CVD risk factors such as obesity/adiposopathy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and sleep disorders. While insulin resistance may be a contributing mechanism to each of these CVD risk factors, it is not the only mechanism. In one example, while obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is often associated with insulin resistance, OSA can also contribute to NAFLD due to hypoxia, inflammation, endotoxemia, and gut barrier dysfunction. [159]

Nonalcoholic fatty liver is commonly defined as ≥ 5% liver fat (hepatosteatosis) without hepatocellular injury. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is the presence of ≥ 5% hepatosteotosis, lobular inflammation, plus hepatocellular injury (hepatocyte ballooning with or without fibrosis). Hepatosteatosis alone rarely progresses to cirrhosis and liver failure. Conversely, patients with NASH are at increased risk of cirrhosis and liver failure. Diagnosis of NAFLD may include use or measurement of aspartate transaminase / alanine transaminase (AST/ALT) ratio index, various serum biomarkers, NAFLD Fibrosis score, Fibrosis 4 calculator, enhanced liver fibrosis score, fibrometer, fibrotest, and hepatascore. Hepatic imaging may include liver ultrasound, vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE or Fibroscan), CT of the liver, MRI proton density fat fraction, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Table 8 lists ten things to know about hepatic imaging for NAFLD.

Table 8.

Ten things to know about hepatic imaging for NAFLD.

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2018 Current guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review with comparative analysis [162]2018 The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. [163]2017 Imaging evaluation of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: focused on quantification. [164]2016 A comparison of liver fat content as determined by magnetic resonance imaging-proton density fat fraction and MRS versus liver histology in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Acta Radiol. [165]2021 Obesity Medicine Association Obesity Algorithm [101] |

5.9. Carotid ultrasound, peripheral Doppler imaging, ultrasound flow-mediated dilation, other tests of endothelial function, and peripheral vascular imaging

Carotid plaques are atherosclerotic lesions located in the carotid arteries that increase the risk of stroke. Imaging studies to evaluate carotid artery atherosclerotic lesions include CT and MRI. [166] Another imaging technique includes carotid ultrasound, which utilizes sound waves to evaluate the anatomy of carotid arteries. Carotid ultrasound is a procedure that also usually includes doppler assessment of carotid blood flow. [167] Decades ago, it was commonplace in lipid-altering drug development that B-mode ultrasound carotid intima medial-media thickness (CIMT) imaging studies would be conducted in the interim between shorter-term lipid efficacy clinical trials (e.g., often 12 week trials) and CVD outcomes studies (e.g., 2–5 years). The rationale was to demonstrate potential lack of atherosclerosis disease progression in the carotid arteries, or perhaps regression with lipid-altering therapy. Such imaging results could be reported after lipid efficacy publications and before CVD outcome result publications. Largely because of the lack of acceptance of CIMT studies by regulatory agencies in the drug development process, minimal improvement in predicting CVD risk beyond established CVD risk scores, and because of misinterpretation and/or mischaracterization of CIMT results, [168] CIMT studies are less commonly performed now in CVD prevention pharmacotherapy development programs (i.e., lipid-altering drugs). [169] However, international guidelines do support the presence of plaque on CIMT as identifying patients at higher CVD risk. [158]

The correlation of peripheral vascular disease with CAD is a justification why an ankle brachial index (ABI) of < 0.9 is considered an atherosclerotic CHD risk-enhancing factor. [64] ABI is measured via doppler-aided blood pressure differential assessments, but typically does not involve imaging. Plethysmography is the measured changes in volume of an organ or body, as in air displacement plethysmography (BOD POD). [101] Plethysmography to assess venous flow (e.g., evaluation of possible deep vein thrombosis) can be performed via impedance, ultrasonography or air plethsmography. [170] Peripheral doppler imaging (e.g., B-mode doppler ultrasound and duplex ultrasound) can assess both peripheral venous and arterial disease. [170] Emerging doppler techniques include pulse wave velocity, vascular optical tomographic (i.e., cross-sectional) imaging, and polymer-based sensors (i.e., hemodynamic monitor or HeMo). [170]

Endothelial dysfunction may be consequence and predictor of atherosclerosis. An ultrasound flow-mediated dilation imaging study of the brachial artery is a noninvasive tool utilized to assess endothelial function and can be used to predict future CVD events. [171] While flow mediated dilation may improve on risk scores (i.e., Framingham risk score) in predicting CHD, when adjusted for confounders, the association of brachial flow mediated dilation with CHD may no longer be significant, and may not improve discrimination and classification of CVD risk within intermediate risk individuals. [172]

Other imaging studies that can assess endothelial function include invasive atomic force microscopy, myographs, and before and after images of invasive intra-arterial administration of vasoactive substances. Non-invasive imaging studies of endothelial function include enclosed zone flow mediated dilation, digital (finger) pulse amplitude tonometry, digital photoplethsmography, arterial pulse wave analysis, and others. [173,174,175,176] From a cardiac standpoint, among the more common historic techniques to assess endothelial function include coronary epicardial vasoreactivity via quantitative coronary angiography, coronary microvascular function via Doppler, flow mediated dilation, venous occlusive plethysmography and finger plethysmography. [177] While the non-research, clinical utility of endothelial function assessment remains unclear, monitoring of endothelial function has the theoretical potential to provide information on vascular health, predictor of future adverse cardiovascular events, and assessment of the effectiveness of stent placement and medications such as statins, beta-blockers, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. [178]

Peripheral vascular imaging is often considered for patients with suspected limb ischemia having noncompressible arteries (ABI > 1.4) or objectively measured obstruction (ABI ≤ 0.9). Even if ABI is within the normal or borderline range, a nonhealing wound or gangrene of the extremities might suggest the need for additional diagnostic procedures. Perfusion assessments include toe-brachial index, transcutaneous oxygen pressure, and skin perfusion pressure. If the totality of this diagnostic evidence supports limb ischemia, then imaging studies to consider include duplex ultrasound, computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or invasive angiography. [179] Table 9 lists ten things to know about carotid ultrasound, peripheral doppler imaging, ultrasound flow-mediated dilation, other tests of endothelial function, and peripheral vascular imaging.

Table 9.

Ten things to know about carotid ultrasound, peripheral doppler imaging, ultrasound flow-mediated dilation, other tests of endothelial function, and peripheral vascular imaging.

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2019 Global perspective on carotid intima-media thickness and plaque: should the current measurement guidelines be revisited? [169]2018 Peripheral vascular disease assessment in the lower limb: a review of current and emerging non-invasive diagnostic methods. [170]2018 Endothelial Function: A Short Guide for the Interventional Cardiologist [178]2017 Flow Mediated Dilation as a Biomarker in Vascular Surgery Research [180]2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. [179] |

5.10. Imaging other body organs applicable to preventive cardiology (brain, kidney, and ovary)

In addition to heart and peripheral vasculature, body composition, and evaluation of hepatic fat, assessment of other organs may have applicability to preventive cardiology, such as the brain, kidney, and ovaries.

Imaging of the brain can be achieved by multiple different techniques, such as PET, MRI, MRS, and others. In persons without symptomatic cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or peripheral vascular disease, CVD risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and cigarette smoking are independently associated with brain imaging changes before the clinical manifestation of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease. Types of structural brain changes associated with one or more of these CVD risk factors include reduction in whole-brain volume, white matter changes, and functional brain changes such as reduced cerebral blood flow. Identification of brain changes due to CVD risk factors represents an opportunity to intervene before irreversible deleterious brain damage occurs. [181]

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at increased risk for CAD, with the risk for CVD increasing with worsening kidney function. [1] Most cases of adult-onset CKD are due to the major CVD risk factors of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, with obesity, cigarette smoking, and older age also risk factors for both CKD and CVD. [182] Patients with CKD are at increased risk for complications related to revascularization, and long-term results are less favorable compared to individuals with normal kidney function. [183] Examples of the adverse CVD consequences of CKD progression include non-atherosclerotic CVD, left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac dysthymias, sudden cardiac death, diffuse arterial calcification, mitral annular and aortic valve calcification, [184] hemorrhagic stroke, and increased risk for mortality after a CVD event. [185] Currently, kidney imaging techniques (e.g., ultrasound, CT, and MRI) assess kidney size and density, nephrolithiasis, and crude markers of parenchymal damage (e.g., gross anatomic defects such as systemic disease, malignancies, and obstructive nephropathy). Newer imaging methods may enhance non-invasive detection of structural, functional, and molecular kidney changes, such as dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) and blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) MRI, and the use of novel contrast agents, such as microbubbles and nanoparticles. [186] Regarding cardiac imaging in patients with CKD, the choice of cardiac imaging should be based on the clinical presentation, matching the desired information to the most appropriate imaging test, and the imaging procedure that avoids use of potentially nephrotoxic agents.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is among the most common endocrine disorder in women of reproductive age and occurs due to an imbalance of reproductive hormones in pre-menopausal women (with some metabolic abnormalities potentially extending into perimenopause). [187] The presence of polycystic ovaries alone may not be associated with increased CVD risk. [188] However, PCOS is often associated with CVD risk factors such as insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia (increased triglycerides and decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol), metabolic syndrome, increased C-reactive protein, increased CAC scores, increased carotid intima-medial thickness, endothelial dysfunction, and sleep apnea. [1,2,101,189] Table 10 lists ten things to know about imaging of other body organs applicable to preventive cardiology (brain, kidney, and ovary).

Table 10.

Ten things to know about imaging of other body organs applicable to preventive cardiology (brain, kidney, and ovary).

|

| Sentinel Guidelines and References2020 Cardiac imaging for Coronary Heart Disease Risk Stratification in Chronic Kidney Disease [183]2019 Chronic Kidney Disease and Coronary Heart Disease [185]2018 Recent advances in renal imaging. [186]2018 International evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. [199]2014 Brain imaging changes associated with risk factors for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease in asymptomatic patients [181] |

6. Conclusion

The “ASPC Top Ten Imaging 2021” is intended to be complementary to the “ASPC Top Ten CVD Risk Factors,” and summarizes ten things to know about ten imaging studies related to CVD prevention. The “ASPC Top Ten Imaging 2021” represents a starting point for those interested in CVD evaluation and CVD risk assessment. Knowledge of CVD cardiac and non-cardiac imaging can help guide preventive cardiology management and treatment. Just as the practice of preventive cardiology is a whole-body discipline, so should clinicians engaged in preventive cardiology understand multi-organ imaging modalities that might assist in assessing CVD risk. Such imaging methods naturally include evaluation of the heart. But imaging relative to cardiovascular disease prevention also includes dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) body composition, hepatic imaging, peripheral artery / endothelial function imaging, and images of other body organs applicable to preventive cardiology (brain, kidney, ovary). Many cardiologists engaged in preventive cardiology routinely perform heart-centered imaging. Many non-cardiologists engaged in preventive cardiology routinely perform non-heart centered imaging applicable to preventive cardiology. Cardiologists and non-cardiologists alike may benefit from a basic working knowledge of imaging studies applicable to preventive cardiology.

Funding

None.

Author contribution

All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the submission and approved responses to AJPC reviewer comments. Harold Bays MD served as medical writer, wrote the preliminary draft outline, incorporated author and reviewer edits, and submitted the manuscript.

Disclosures

Harold Edward Bays’ research site has received research grants from 89Bio, Acasti, Akcea, Allergan, Alon Medtech/Epitomee, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Axsome, Boehringer Ingelheim, Civi, Eli Lilly, Esperion, Evidera, Gan and Lee, Home Access, Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, Lexicon, Matinas, Merck, Metavant, Novartis, NovoNordisk, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Selecta, TIMI, and Urovant. Dr. Harold Bays has served as a consultant/advisor for 89Bio, Amarin, Esperion, Matinas, and Gelesis, and speaker for Esperion. Amit Khera has no disclosures. Michael J. Blaha reports grants from NIH, FDA, AHA, Aetna Foundation, Amgen and the following advisory boards: Amgen, Sanofi, Regeneron, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, Akcea, Kaleido, 89Bio, and consulting with Kowa, Inozyme. Matthew J Budoff has received research grants from Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Amgen, Amarin and Boehringer Ingleheim. Dr Budoff has received honoraria from Amgen, Boehringer Ingleheim, Lilly, Amarin and Astra Zeneca. Peter P. Toth has served as a consultant for Amarin, Amgen, bio89, Kowa, Novartis, Resverlogix, Theravance; and speaker for Amarin, Amgen, Esperion, Merck, Novo-Nordisk.

Contributor Information

Harold E. Bays, Email: hbaysmd@outlook.com.

Amit Khera, Email: Amit.Khera@UTSouthwestern.edu.

Michael J. Blaha, Email: mblaha1@jhmi.edu.

Matthew J Budoff, Email: mbudoff@lundquist.org.

Peter P. Toth, Email: Peter.toth@cghmc.com.

References

- 1.Bays HE, Taub PR, Epstein E, Michos ED, Ferraro RA, Bailey AL. Ten things to know about ten cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am J Prevent Cardiol. 2021;5 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2021.100149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bays HE. Ten things to know about ten cardiovascular disease risk factors (“ASPC Top Ten –2020”) Am J Prevent Cardiol. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2020.100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaha MJ, Whelton SP, Al Rifai M, Dardari Z, Shaw LJ, Al-Mallah MH. Comparing risk scores in the prediction of coronary and cardiovascular deaths. JACC: Cardiovas Imaging. 2020:3302. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolk MJ, Bailey SR, Doherty JU, Douglas PS, Hendel RC, Kramer CM. ACCF/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2013 multimodality appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American college of cardiology foundation appropriate use criteria task force, American heart association, american society of echocardiography, American society of nuclear cardiology, heart failure society of America, heart rhythm society, society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, society of cardiovascular computed tomography, society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance, and society of thoracic surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:380–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladapo JA, Blecker S, O'Donnell M, Jumkhawala SA, Douglas PS. Appropriate use of cardiac stress testing with imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161153. e0161153-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sidik NP, McEntegart M, Roditi G, Ford TJ, McDermott M, Morrow A. Rationale and design of the British heart foundation (BHF) coronary microvascular function and CT coronary angiogram (CorCTCA) study. Am Heart J. 2020;221:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taqueti VR, Di Carli MF. Coronary microvascular disease pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic options: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2625–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamis-Holland JE, Jneid H, Reynolds HR, Agewall S, Brilakis ES, Brown TM. Contemporary diagnosis and management of patients with myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2019;139:e891–e908. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sucato V, Testa G, Puglisi S, Evola S, Galassi AR, Novo G. Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA): Intracoronary imaging-based diagnosis and management. J Cardiol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scalone G, Niccoli G, Crea F. Editor's choice- pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of MINOCA: an update. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8:54–62. doi: 10.1177/2048872618782414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira VM. CMR should be a mandatory test in the contemporary evaluation of "MINOCA". JACC Cardiovas Imaging. 2019;12:1983–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vancheri F, Longo G, Vancheri S, Henein M. Coronary microvascular dysfunction. J Clin Med. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/jcm9092880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Filippo M, Capasso R. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging in the assessment of patients presenting with chest pain suspected for acute coronary syndrome. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:255. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.06.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos JG, Fyrdahl A, Wieslander B, Thalén S, Reiter G, Reiter U. Comprehensive cardiovascular magnetic resonance diastolic dysfunction grading shows very good agreement compared with echocardiography. JACC Cardiovas Imaging. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konerman MC, Greenberg JC, Kolias TJ, Corbett JR, Shah RV, Murthy VL. Reduced myocardial flow reserve is associated with diastolic dysfunction and decreased left atrial strain in patients with normal ejection fraction and epicardial perfusion. J Card Fail. 2018;24:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein R, Celiker-Guler E, Rotstein BH, deKemp RA. PET and SPECT tracers for myocardial perfusion imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 2020;50:208–218. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2020.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motwani M, Jogiya R, Kozerke S, Greenwood JP, Plein S. Advanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance myocardial perfusion imaging: high-spatial resolution versus 3-dimensional whole-heart coverage. Circ Cardiovas Imaging. 2013;6:339–348. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibanez B, Aletras AH, Arai AE, Arheden H, Bax J, Berry C. Cardiac MRI endpoints in myocardial infarction experimental and clinical trials: JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:238–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko SM, Hwang SH, Lee HJ. Role of cardiac computed tomography in the diagnosis of left ventricular myocardial diseases. J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;27:73–92. doi: 10.4250/jcvi.2019.27.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rischpler C, Nekolla SG, Kunze KP, Schwaiger M. PET/MRI of the heart. Semin Nucl Med. 2015;45:234–247. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoilund-Carlsen PF, Piri R, Gerke O, Edenbrandt L, Alavi A. Assessment of total-body atherosclerosis by PET/computed tomography. PET Clin. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asher A, Singhal A, Thornton G, Wragg A, Davies C. FFRCT derived from computed tomography angiography: the experience in the UK. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2018;16:919–929. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2018.1538786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conte E, Sonck J, Mushtaq S, Collet C, Mizukami T, Barbato E. FFRCT and CT perfusion: A review on the evaluation of functional impact of coronary artery stenosis by cardiac CT. Int J Cardiol. 2020;300:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuo H, Kawase Y. FFR and iFR guided percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovas Interv Ther. 2016;31:183–195. doi: 10.1007/s12928-016-0404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fathala A, Aboulkheir M, Bukhari S, Shoukri MM, Abouzied MM. Benefits of adding coronary calcium score scan to stress myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography imaging. World J Nucl Med. 2019;18:149–153. doi: 10.4103/wjnm.WJNM_34_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engbers EM, Timmer JR, Ottervanger JP, Mouden M, Knollema S, Jager PL. Prognostic value of coronary artery calcium scoring in addition to single-photon emission computed tomographic myocardial perfusion imaging in symptomatic patients. Circ Cardiovas Imaging. 2016;9 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tota-Maharaj R, Al-Mallah MH, Nasir K, Qureshi WT, Blumenthal RS, Blaha MJ. Improving the relationship between coronary artery calcium score and coronary plaque burden: addition of regional measures of coronary artery calcium distribution. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Mallah MH, Qureshi W, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Berman DS, Budoff MJ. Does coronary CT angiography improve risk stratification over coronary calcium scoring in symptomatic patients with suspected coronary artery disease? Results from the prospective multicenter international CONFIRM registry. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:267–274. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saraste A, 2019 Knuuti J.ESC. guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: Recommendations for cardiovascular imaging. Herz. 2020;45:409–420. doi: 10.1007/s00059-020-04935-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourque JM, Beller GA. Exercise stress ECG without imaging. JACC Cardiovas Imaging. 2015;8:1309–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourque JM, Holland BH, Watson DD, Beller GA. Achieving an exercise workload of > or = 10 metabolic equivalents predicts a very low risk of inducible ischemia: does myocardial perfusion imaging have a role? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christman MP, Bittencourt MS, Hulten E, Saksena E, Hainer J, Skali H. Yield of downstream tests after exercise treadmill testing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alzahrani T, Khiyani N, Zeltser R. StatPearls Publishing LLC; Treasure IslandFL: 2020. Adenosine SPECT thallium imaging. StatPearlsStatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann A, Williams J. Considerations for stress testing performed in conjunction with myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Med Technol. 2020;48:114–121. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.120.245308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Einstein AJ. Effects of radiation exposure from cardiac imaging: how good are the data? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:553–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biersmith MA, Tong MS, Guha A, Simonetti OP, Addison D. Multimodality cardiac imaging in the era of emerging cancer therapies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Cancer Society. Understanding Radiation Risks from Imaging Tests. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/tests/understanding-radiation-risk-from-imaging-tests.html Accessed October 9 2020.

- 38.Harvard Medical School. Radiation Risk From Medical Imaging. https://www.health.harvard.edu/cancer/radiation-risk-from-medical-imaging Accessed October 9 2020.

- 39.Bos D, Leening MJG. Leveraging the coronary calcium scan beyond the coronary calcium score. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:3082–3087. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5264-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Messenger B, Li D, Nasir K, Carr JJ, Blankstein R, Budoff MJ. Coronary calcium scans and radiation exposure in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;32:525–529. doi: 10.1007/s10554-015-0799-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Erbel R, Watson KE. Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:434–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parikh R, Patel A, Lu B, Senapati A, Mahmarian J, Chang SM. Cardiac computed tomography for comprehensive coronary assessment: beyond diagnosis of anatomic stenosis. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovas J. 2020;16:77–85. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-16-2-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richards CE, Dorman S, John P, Davies A, Evans S, Ninan T. Low-radiation and high image quality coronary computed tomography angiography in "real-world" unselected patients. World J Radiol. 2018;10:135–142. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v10.i10.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Den Harder AM, Willemink MJ, De Ruiter QM, De Jong PA, Schilham AM, Krestin GP. Dose reduction with iterative reconstruction for coronary CT angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Radiol. 2016;89 doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stocker TJ, Deseive S, Leipsic J, Hadamitzky M, Chen MY, Rubinshtein R. Reduction in radiation exposure in cardiovascular computed tomography imaging: results from the prospective multicenter registry on radiaTion dose estimates of cardiac CT angiography in daily practice in 2017 (PROTECTION VI) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3715–3723. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eskandari M, Monaghan M. Contrast echocardiography in daily clinical practice. Herz. 2017;42:271–278. doi: 10.1007/s00059-017-4533-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Case JA, deKemp RA, Slomka PJ, Smith MF, Heller GV, Cerqueira MD. Status of cardiovascular PET radiation exposure and strategies for reduction: an information statement from the cardiovascular PET task force. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:1427–1439. doi: 10.1007/s12350-017-0897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Kim KP, Smith-Bindman R, McAreavey D. Myocardial perfusion scans: projected population cancer risks from current levels of use in the United States. Circulation. 2010;122:2403–2410. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.941625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Desiderio MC, Lundbye JB, Baker WL, Farrell MB, Jerome SD, Heller GV. Current status of patient radiation exposure of cardiac positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomographic myocardial perfusion imaging. Circ Cardiovas Imaging. 2018;11 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.007565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen-Scarabelli C, Scarabelli TM. The ethics of radiation exposure in cancer-treated patients: Editorial for: frequent MUGA testing in a myeloma patient: a case-based ethics discussion. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:1355–1360. doi: 10.1007/s12350-016-0567-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kern M. Radiation exposure in cardiology testing: how much is too much? Letter from the editor. Cath Lab Digest. 2007:15. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kobayashi T, Hirshfeld JW., Jr Radiation exposure in cardiac catheterization: operator behavior matters. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017:10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.005689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richards CE, Obaid DR. Low-dose radiation advances in coronary computed tomography angiography in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2019;15:304–315. doi: 10.2174/1573403X15666190222163737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neves PO, Andrade J, Moncao H. Coronary artery calcium score: current status. Radiol Bras. 2017;50:182–189. doi: 10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Celeng C, Leiner T, Maurovich-Horvat P, Merkely B, de Jong P, Dankbaar JW. Anatomical and functional computed tomography for diagnosing hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovas Imaging. 2019;12:1316–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neglia D, Rovai D, Caselli C, Pietila M, Teresinska A, Aguade-Bruix S. Detection of significant coronary artery disease by noninvasive anatomical and functional imaging. Circ Cardiovas Imaging. 2015;8 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pijls NH, Sels JW. Functional measurement of coronary stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1045–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohan J, Bhatti K, Tawney A, Zeltser R. StatPearls; Treasure Island (FL): 2020. Coronary artery calcification. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rijlaarsdam-Hermsen D, Lo-Kioeng-Shioe MS, Kuijpers D, van Domburg RT, Deckers JW, van Dijkman PRM. Prognostic value of the coronary artery calcium score in suspected coronary artery disease: a study of 644 symptomatic patients. Neth Heart J. 2020;28:44–50. doi: 10.1007/s12471-019-01335-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Orringer CE, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, Budoff MJ, Goldberg RB, Gill EA. The national lipid association scientific statement on coronary artery calcium scoring to guide preventive strategies for ASCVD risk reduction (Early proof version) J Clin Lipidol. 2021:2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2020.12.005. Accessed January 6 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]