Abstract

Background

The reported prevalence of depression among individuals with psoriasis varies substantially, and the effect of gender on depression distribution has revealed conflicting results. In addition, using medication to identify cases is uncommon.

Objective

To study the prevalence of pharmacologically treated depression among individuals with and without psoriasis in a Swedish population using ICD-10 codes and data from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register.

Methods

A retrospective case-control population-based study was performed including all living individuals (age ≥18 years) in Region Jönköping, southern Sweden (n = 273,536). ICD-10 codes for the diagnosis of psoriasis (L40.*) and depression (F32.* and F33.*), and data on pharmacological treatment from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, were extracted from electronic medical records between April 9, 2008 and January 1, 2016. The extraction date was January 1, 2016.

Results

The risk of pharmacologically treated depression was increased in individuals with psoriasis (age- and sex-adjusted OR 1.55; CI 1.43–1.68); 21.1% of women with psoriasis received pharmacological treatment for depression during the study period compared to 14.2% in the control population. Prevalence figures for depression were significantly higher in women with psoriasis compared to men. The risk of suffering from depression was highest among male and female patients with psoriasis under the age of 31 years.

Conclusions

Depression is common among patients with psoriasis. The results of the current study underline the need for dermatologists to adopt a holistic approach, looking beyond the skin, when handling patients with psoriasis in every-day clinical practice.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Depression, Sex, Age, Comorbidity

Introduction

Psoriasis is a heterogenous chronic inflammatory disease mainly associated with skin and joint manifestations. It is associated with a high prevalence of comorbid diseases including conditions such as metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases for which shared pathophysiological processes are known [1, 2]. Apart from physical discomfort, psoriasis leads to a significant psychosocial burden. Many studies have shown an association between depression and psoriasis [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. The relationship is bi-directional as it has been shown that psoriasis is associated with an increased depression risk but that depression is also associated with an increased risk of psoriasis [9, 10].

Severe psoriasis, long disease duration, and PsA are associated with higher depression risk [4, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Although the view of depression as a primary inflammatory disease may be debated, it is considered to be a disease influenced by inflammation [15]. Common inflammatory pathomechanisms such as deranged HPA axis and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-1β, interferon-γ, and interleukin-6 involved in both depression and psoriasis may be possible links between these two diseases [16, 17, 18, 19]. Several studies have shown that the treatment of psoriasis with biological drugs is associated with improvement both in symptoms of anxiety and depression [20, 21, 22].

The reported prevalence of depression in psoriasis varies substantially between 6 and 62% according to a systemic review and meta-analysis of 98 studies performed by Dowlatshahi et al. [3] (2014) and 2.1–39.2% in a systemic review by Koo et al. [19] including studies published between 2006 and 2016. This variation is attributed to differences in study design and sampling methods as well as differences in genetic predisposition or milieu. The diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) is based on the existence of depressive symptoms. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders − DSM-5, the diagnosis of MDD requires at least 5 symptoms to be present within a 2-week period. Depressed mood or anhedonia is mandatory. Other symptoms include appetite/weight changes, sleep difficulties, psychomotor agitation or retardation, loss of energy, diminished ability to think or concentrate, feelings of worthlessness, or excessive guilt and suicidality. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) criteria are similar to those of DSM-5 but require 4 out of 10 depressive symptoms yielding a lower threshold for mild depression. However, most studies on depression and psoriasis do not use structural clinical interviews since these are time consuming and expensive. Instead, questionnaires or ICD-10 diagnostic codes from the clinical setting are commonly used. When using questionnaires validated for the detection of depression such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI) one must be aware that they have not been developed to assess dermatology patients. It is possible that they may falsely detect symptoms and complaints related to psoriasis as symptoms related to depression [3].

There are several aspects of the unidimensional MDD construct as defined by DSM-5 or ICD-10 that are problematic. It cannot be ruled out that similar clinical features or symptoms may be caused by different underlying mechanisms. This would imply the existence of subtypes of depression that are currently missed [23, 24]. The criteria also include antagonistic symptoms such as weight gain or weight loss and psychomotor agitation or retardation, which furthermore underlines the heterogonous nature of depression states. Furthermore, epidemiological studies suggest that depression is dynamic in nature. Sub-syndromal states or depressive symptoms below ICD-10/DSM-5 criteria, dysthymia, and minor and major depression syndromes may occur in the same individuals over time [25]. A single structural clinical interview may indeed miss this continuum.

MDD as opposed to psoriasis is a disease with a heterogeneous sex distribution, the disease being twice as common among women [26]. The published data on the gender distribution of psoriasis patients with depression is somewhat conflicting. Several studies suggest no gender difference in depression occurrence [27, 28] whereas other studies state that female sex is associated with higher risk of depression [29, 30, 31].

Knowledge about the prevalence and age and sex distribution of depression in patients with psoriasis is imperative for clinicians to make better risk assessments in everyday practice. Identifying undiagnosed depression has the potential to improve compliance, quality of life, and patient health. Population-based studies on psoriasis and depression including data on antidepressant drugs use are sparse. Hence, the present study was performed to estimate prevalence rates of depression among patients with psoriasis in comparison to the background population with focus on distribution over age groups, gender, and drug consumption.

Materials and Methods

For further details, see the online supplementary material (see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000509732 for all online suppl. material) (Fig. 1; Table 1) [32, 33].

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of Materials and Methods.

Table 1.

ATC codes for pharmacological treatment of psoriasis and depression extracted from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register and the number of individuals with psoriasis issued at least one prescription

| Medication | ATC codes | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Topical calcipotriol, combination with betamethasone or ichthammol | D05A: antipsoriatics for topical use | 2,629 (57.3) |

| Dimethylfumarate or acitretin | D05B: antipsoriatics for systemic use | 247 (5.4) |

| Topical corticosteroids III or IV | D07AC: corticosteroids, potent (group III) D07AD: corticosteroids, very potent (group IV) |

3,796 (82.8) |

| Immunosuppressive agents | L04AX03: methotrexate | 1,016 (22.1) |

| Apremilast | L04AA32: apremilast | 26 (0.6) |

| TNF-α inhibitors | L04AB: TNF inhibitors | 235 (5.1) |

| Interleukin inhibitors | L04AC: interleukin inhibitors | 37 (0.8) |

| Calcineurin inhibitors | L04AD01: ciclosporin | 55 (1.2) |

| Antidepressants | N06A: antidepressant drugs* | 1,383 (30.2) |

Including non-selective monoamine reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and other antidepressants.

Results

Study Population

The age and sex distribution of the study population is presented in Table 2. In total, 4,587 patients with psoriasis (prevalence 1.7%) and 30,298 patients with pharmacologically treated depression (prevalence 11.1%) were included; 268,949 individuals served as controls. The mean age of patients with psoriasis was higher than that of controls. Gender was evenly distributed among psoriasis patients and controls. In the depression group female gender was twice as common.

Table 2.

Demographics of patients with psoriasis and controls

| Psoriasis (n = 4,587) | Controls (n = 268,949) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 2,282 (49.7) | 134,560 (50.0) |

| Female | 2,305 (50.3) | 134,389 (50.0) |

| Age | ||

| Mean ± SD | 57.4±17.3 | 49.7±19.5 |

| Range | 18–103 | 18–105 |

| Age groups, n (%) | ||

| <31 years | 411 (9.0) | 57,497 (21.4) |

| 31–43 years | 637 (13.9) | 52,091 (19.4) |

| 44–55 years | 898 (19.6) | 53,689 (20.0) |

| 56–69 years | 1,382 (30.1) | 56,026 (20.8) |

| 70+ years | 1,259 (27.4) | 49,646 (18.5) |

Depression Is Increased in Patients with Psoriasis

The prevalence of pharmacologically treated depression was significantly higher among patients with psoriasis compared to the control population (16.9 vs. 11.0%, χ2p < 0.001). The odds ratio (OR) of suffering from pharmacologically treated depression in patients with psoriasis was found to be 1.64 (CI 1.52–1.78) and 1.55 (CI 1.43–1.68) when adjusting for age and sex.

Higher Risk of Depression in Females

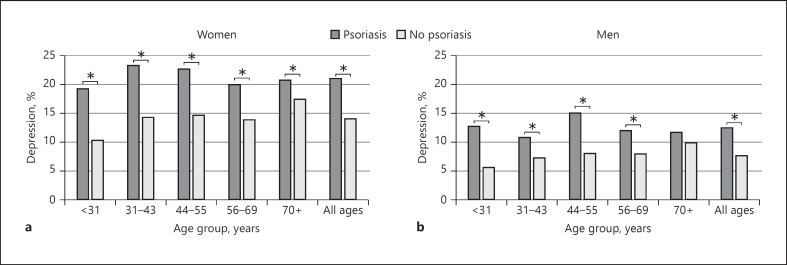

The prevalence of pharmacologically treated depression was significantly higher among women with psoriasis compared to men (21.1 vs. 12.6%, χ2p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The prevalence of depression among women (a) and men (b) with psoriasis compared to controls. * p < 0.05, χ2.

Female gender was associated with a similar increase in pharmacologically treated depression risk within both the control and psoriasis group: OR 1.84 (CI 1.80–1.88) and OR 1.68 (CI 1.47–1.92), respectively. When dividing the study population by gender, the OR of having pharmacologically treated depression with concurrent psoriasis was 1.71 (CI 1.51–1.94) for men and 1.62 (CI 1.46–1.79) for women (Table 3).

Table 3.

Individuals with psoriasis and concomitant depression stratified by sex and age showing the number, prevalence, and odds ratio of depression compared to the control population

| Age group | Female |

Male |

Both sexes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| depression, n (%) | OR (95% CI) |

depression, n (%) | OR (95% CI) |

depression, n (%) | OR (95% CI) |

|

| <31 years | 43 (19.3) | 2.08 (1.49–2.91) | 24 (12.8) | 2.42 (1.57–3.72) | 67 (16.3) | 2.28 (1.75–2.96) |

| 31–43 years | 70 (23.4) | 1.82 (1.39–2.39) | 37 (10.9) | 1.53 (1.08–2.16) | 107 (16.8) | 1.67 (1.35–2.06) |

| 44–55 years | 92 (22.8) | 1.70 (1.34–2.15) | 75 (15.2) | 2.01 (1.57–2.59) | 167 (18.6) | 1.78 (1.50–2.11) |

| 56–69 years | 140 (20.1) | 1.54 (1.27–1.86) | 83 (12.1) | 1.57 (1.25–1.99) | 223 (16.1) | 1.55 (1.34–1.80) |

| 70+ years | 142 (20.8) | 1.23 (1.02–1.48) | 68 (11.8) | 1.20 (0.93–1.56) | 210 (14.2) | 1.21 (1.04–1.40) |

| All ages | 487 (21.1) | 1.62 (1.46–1.79) | 287 (12.6) | 1.71 (1.51–1.94) | 774 (16.9) | 1.65 (1.52–1.78) |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Younger Age Is Associated with Increased Risk of Depression in Patients with Psoriasis

The OR of having a concomitant pharmacologically treated depression among men and women was related to age, with highest ORs at lower age. In females with psoriasis, there is a steady decrease in ORs over age groups. Males with psoriasis aged <31 years had the highest risk of suffering from pharmacologically treated depression (OR 2.42; CI 1.57–3.72) (Table 3).

Discussion

Our results show that Swedish patients with psoriasis are more likely to suffer from concomitant pharmacologically treated depression in comparison to individuals without psoriasis (age- and sex-adjusted OR 1.55; CI 1.43–1.68). This is in line with a meta-analysis of 98 studies on psoriasis and depression published in 2014 which showed a pooled OR of 1.57 (CI 1.40–1.76) [3]. A recent Norwegian survey-based population study (HUNT3) found no association (OR 1.12; CI 0.97–1.28). Only long disease duration, severe disease, or inverse location was significantly associated with depressive symptoms [8]. The HUNT3 study included data on possible confounders such as smoking, education, body mass index, and physical activity which is a strength. However, the participation rate was low, and the use of questionnaires suggests that patients with mild psoriasis lacking contact with the healthcare system may have been included. On the other hand, a US population survey study running during 2009–2012 with a very similar methodology to the recent Norwegian study has shown a higher OR of 2.09 (CI 1.41–3.11) [34].

Jensen et al. [4] published a Danish nationwide cohort study on psoriasis and new-onset depression in 2016. After adjusting for comorbidity, the incidence rate ratio was significant only in patients aged <50 years with severe psoriasis. It is difficult to compare these results with our study as our method enabled the inclusion of cases where depression could have been diagnosed before the onset of psoriasis.

Depression was more prevalent among women in the control population, and our data revealed that this gender difference was also present in individuals with psoriasis, which emphasizes the frequent occurrence and importance of this comorbidity in women. There are previous studies that did not find gender differences [27, 28]. These studies differed in study design by recruiting patients consecutively at a dermatology outpatient clinic and sending questionnaires to patients with known psoriasis which could introduce bias. Including a whole population as in the current study implies robustness in results that these studies may lack. A recent Polish study on 219 patients with psoriasis has shown that female sex is associated with an increased risk of depression: OR 2.36 (CI 1.15–4.85), and a population-based Taiwanese study including 17,086 psoriasis patients and 1,607,242 controls found that the prevalence of depression is higher among young and middle-aged women with psoriasis, which is similar to the results of the current study [30, 31].

As reporting or diagnosing depression is not always performed correctly, data on comedication is important to substantiate depression claim. In the current study, we can assume that using the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (PDR) data on dispensed antidepressants increased the positive predictive value (PPV) of depression classification. In a German study in over 1,200 psoriasis patients hospitalized for severe psoriasis, comedication assessment revealed that 6% of the patients were taking psycholeptic and 5.5% antidepressant drugs, with 71.2% in the latter group being female [35]. Our study, running over a much longer time period, including individuals in both inpatient and outpatient care, revealed that 30.2% of the psoriasis patients were prescribed antidepressant drugs, with 62.4% being female.

In a systemic literature search including 98 studies, Dowlatshahi et al. [3] found that the prevalence for antidepressant drug use was 9% and that psoriasis patients used more antidepressants than controls (OR 4.24; CI 1.53–11.76). The high OR compared to the present study may be affected by misclassification using questionnaires or not taking into account other indications for antidepressant medication.

The association between depression and psoriasis differs over age groups, with the highest risk being present among young age groups (<31 years). This finding is concordant with previous studies proposing a higher psychological burden of psoriasis disease in younger ages [11]. Depression may be influenced by disease severity, and several studies have suggested that psoriasis in younger individuals tends to be more severe [36, 37].

The prevalence of psoriasis (1.68%) in the current study is comparable to previously published data of studies with similar design. A Swedish medical record-based study published in 2014 has shown a prevalence rate of 1.23% [38]. Studies of self-reported psoriasis in Nordic countries tend to have higher prevalence rates. In the NORPAPP (Nordic Patient Survey of Psoriasis and PsA) study published in 2019, psoriasis prevalence was 4.5% among Swedish respondents with self-reported psoriasis also diagnosed by a physician [39]. The discrepancy in prevalence rates between self-reported and register-based studies is well known. Not all patients with psoriasis have established contact with the healthcare system or they may misdiagnose other skin complaints as psoriasis. The prevalence of depression (11.1%) in the current study is similar to that in a previously published Swedish study showing a prevalence of 10.8% with similar gender differences [26], underlining the reliability of the present data.

There are some limitations to our study. Our methodology does not address temporal relationship between diagnosis and drug dispensation. If the time period between diagnosis and drug dispensation is long it increases the risk that the drug could be dispensed for another indication. Of the drugs studied, several have multiple indications, e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors could be prescribed for anxiety disorders apart from depression. Patients with mild psoriasis disease diagnosed before the study period may not necessarily have ongoing healthcare contact, leading to underrepresentation in the study group. Individuals with psoriasis not registered as such in the EMR during the study period are automatically included in the control population, possibly leading to an underestimation of the difference in depression occurrence. Patients with chronic diseases such as psoriasis may have more contact with healthcare givers leading to higher likelihood of diagnosing other concurrent diseases such as depression, leading to overrepresentation of depression in the psoriasis group. Epidemiological studies based on registries contain a risk of misdiagnosing patients. However, we applied strict case selection criteria to increase PPV. The PPV of a single L40.* diagnosis in a similar setting in the Skåne region (southern Sweden) has been shown to be 81–100% [38]. Another limitation is not adjusting for confounding factors such as obesity and smoking. Nevertheless, the aim of the present study was not to prove causality between psoriasis and depression. Causally linked or not, clinicians need to be aware of the association between depression and psoriasis. The studied population represents the patients having contact with the healthcare system, which arguably is the population relevant for clinicians to be familiar with.

Although prevalence of concomitant psoriasis and depression has been studied in Scandinavian countries, this is the first larger population-based study including a Swedish population. It is important to have in mind that the present study merely investigated the association of psoriasis and depression based on diagnostic codes and drug dispensation. There are many aspects of the association between psoriasis and depression that need further research. One is the hypothetical role of systemic inflammation as the bridge or moderator variable between the two diseases. It is suggested that the contribution of inflammation in depression is related to some but not all depression cases. Hypothetically, certain individuals could be more vulnerable to inflammatory stress due to genetics or childhood trauma [40, 41, 42]. Individuals with depression and higher systemic inflammation are proposed to belong to a subgroup with poorer response to antidepressant medication but better response to exercise, anti-inflammatory treatment, cognitive behaviour therapy, and weight loss (in the case of pre-existent obesity) [40, 43]. Identifying such subgroups among psoriasis patients could have the potential to improve treatment and decrease morbidity. Future studies should also include additional diagnostic tools for depression such as semi-structured interviews and aim to capture psychological and social factors of psoriasis disease that may influence depression. The effects of psychological interventions such as talking or cognitive behavioural therapy dealing with patient's anxiety about treatment or stigmatization and discrimination are important and should be studied further.

A survey to US dermatologists in 2018 showed that a majority agreed on the requirement for regular depression and suicide ideation and behaviour screening in psoriasis patients. Only 27% reported asking their patients about mood or depression [44]. Furthermore, a UK study has shown low agreement between dermatologists and patients regarding psychological distress and that dermatologists often fail to take action when patients are identified as anxious or distressed [45].

Clinicians need to be aware of the high prevalence of depression among patients with psoriasis in Sweden. There is a significant gender difference, and young patients are at higher risk of developing depression. Depression should be addressed in dermatology consultancies since it has the potential to jeopardize compliance, quality of life, and patient health. The World Health Organization Global Report on Psoriasis stresses the importance of people-centred care with focus on comorbidities. Our study further underlines the need of a holistic approach to patient management − possibly with the introduction of screening for depressive symptoms.

Key Message

Pharmacologically treated depression is common among patients with psoriasis. Age and sex influence depression risk.

Statement of Ethics

The present study was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the institute's committee on human research (Dnr. 2014/481-31).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The present study was funded by grants from the Swedish Psoriasis Association and FUTURUM Research Council County Jönköping. These funding sources were not involved in the preparation of data or the manuscript.

Author Contributions

A.D. designed the study, analysed data, and wrote the first draft of the paper and revised the manuscript. U.M. designed the study and wrote and revised the manuscript. O.S. designed the study, analysed data and wrote and revised the manuscript. M.N. analysed data and revised the manuscript. All co-authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the submitted version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Victor Nordling at Jönköping County Council for data retrieval support and Karin Sjöström and Åke Svensson for providing support during manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Conic RR, Damiani G, Schrom KP, Ramser AE, Zheng C, Xu R, et al. Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Cardiovascular Disease Endotypes Identified by Red Blood Cell Distribution Width and Mean Platelet Volume. J Clin Med. 2020 Jan;9((1)):E186. doi: 10.3390/jcm9010186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santus P, Rizzi M, Radovanovic D, Airoldi A, Cristiano A, Conic R, et al. Psoriasis and Respiratory Comorbidities: The Added Value of Fraction of Exhaled Nitric Oxide as a New Method to Detect, Evaluate, and Monitor Psoriatic Systemic Involvement and Therapeutic Efficacy. BioMed Res Int. 2018 Sep;2018:3140682. doi: 10.1155/2018/3140682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Arends LR, Nijsten T. The prevalence and odds of depressive symptoms and clinical depression in psoriasis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014 Jun;134((6)):1542–51. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jensen P, Ahlehoff O, Egeberg A, Gislason G, Hansen PR, Skov L. Psoriasis and New-onset Depression: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016 Jan;96((1)):39–42. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamb RC, Matcham F, Turner MA, Rayner L, Simpson A, Hotopf M, et al. Screening for anxiety and depression in people with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary referral setting. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Apr;176((4)):1028–34. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitt J, Ford DE. Psoriasis is independently associated with psychiatric morbidity and adverse cardiovascular risk factors, but not with cardiovascular events in a population-based sample. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010 Aug;24((8)):885–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu JJ, Feldman SR, Koo J, Marangell LB. Epidemiology of mental health comorbidity in psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018 Aug;29((5)):487–95. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1395800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modalsli EH, Åsvold BO, Snekvik I, Romundstad PR, Naldi L, Saunes M. The association between the clinical diversity of psoriasis and depressive symptoms: the HUNT Study, Norway. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Dec;31((12)):2062–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Min C, Kim M, Oh DJ, Choi HG. Bidirectional association between psoriasis and depression: two longitudinal follow-up studies using a national sample cohort. J Affect Disord. 2020 Feb;262:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dominguez PL, Han J, Li T, Ascherio A, Qureshi AA. Depression and the risk of psoriasis in US women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Sep;27((9)):1163–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, Gelfand JM. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010 Aug;146((8)):891–5. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tribó MJ, Turroja M, Castaño-Vinyals G, Bulbena A, Ros E, García-Martínez P, et al. Patients with Moderate to Severe Psoriasis Associate with Higher Risk of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms: Results of a Multivariate Study of 300 Spanish Individuals with Psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019 Apr;99((4)):417–22. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai TF, Wang TS, Hung ST, Tsai PI, Schenkel B, Zhang M, et al. Epidemiology and comorbidities of psoriasis patients in a national database in Taiwan. J Dermatol Sci. 2011 Jul;63((1)):40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu JJ, Penfold RB, Primatesta P, Fox TK, Stewart C, Reddy SP, et al. The risk of depression, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in patients with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Jul;31((7)):1168–75. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.González-Parra S, Daudén E. Psoriasis and Depression: The Role of Inflammation. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019 Jan-Feb;110((1)):12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010 Mar;67((5)):446–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maydych V. The Interplay Between Stress, Inflammation, and Emotional Attention: relevance for Depression. Front Neurosci. 2019 Apr;13:384. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connor CJ, Liu V, Fiedorowicz JG. Exploring the Physiological Link between Psoriasis and Mood Disorders. Dermatol Res Pract. 2015;2015:409637. doi: 10.1155/2015/409637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koo J, Marangell LB, Nakamura M, Armstrong A, Jeon C, Bhutani T, et al. Depression and suicidality in psoriasis: review of the literature including the cytokine theory of depression. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Dec;31((12)):1999–2009. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon KB, Armstrong AW, Han C, Foley P, Song M, Wasfi Y, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis and comparison of change from baseline after treatment with guselkumab vs. adalimumab: results from the Phase 3 VOYAGE 2 study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018 Nov;32((11)):1940–9. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strober B, Gooderham M, de Jong EM, Kimball AB, Langley RG, Lakdawala N, et al. Depressive symptoms, depression, and the effect of biologic therapy among patients in Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Jan;78((1)):70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langley RG, Feldman SR, Han C, Schenkel B, Szapary P, Hsu MC, et al. Ustekinumab significantly improves symptoms of anxiety, depression, and skin-related quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Sep;63((3)):457–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rantala MJ, Luoto S, Krams I, Karlsson H. Depression subtyping based on evolutionary psychiatry: proximate mechanisms and ultimate functions. Brain Behav Immun. 2018 Mar;69:603–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beijers L, Wardenaar KJ, van Loo HM, Schoevers RA. Data-driven biological subtypes of depression: systematic review of biological approaches to depression subtyping. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 Jun;24((6)):888–900. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0385-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessing LV. Epidemiology of subtypes of depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2007;115((433)):85–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson R, Carlbring P, Heedman Å, Paxling B, Andersson G. Depression, anxiety and their comorbidity in the Swedish general population: point prevalence and the effect on health-related quality of life. PeerJ. 2013 Jul;1:e98. doi: 10.7717/peerj.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Remröd C, Sjöström K, Svensson A. Psychological differences between early- and late-onset psoriasis: a study of personality traits, anxiety and depression in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013 Aug;169((2)):344–50. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esposito M, Saraceno R, Giunta A, Maccarone M, Chimenti S. An Italian study on psoriasis and depression. Dermatology. 2006;212((2)):123–7. doi: 10.1159/000090652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egeberg A, Thyssen JP, Wu JJ, Skov L. Risk of first-time and recurrent depression in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Jan;180((1)):116–21. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wojtyna E, Łakuta P, Marcinkiewicz K, Bergler-Czop B, Brzezińska-Wcisło L. Gender, Body Image and Social Support: Biopsychosocial Deter-minants of Depression Among Patients with Psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017 Jan;97((1)):91–7. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu SC, Chen GS, Tu HP. Epidemiology of Depression in Patients with Psoriasis: A Nationwide Population-based Cross-sectional Study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019 May;99((6)):530–8. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SCB Statistical database SCB, Box 24300, 104 51 Stockholmnd. [Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/

- 33.Furu K, Wettermark B, Andersen M, Martikainen JE, Almarsdottir AB, Sørensen HT. The Nordic countries as a cohort for pharmacoepidemiological research. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010 Feb;106((2)):86–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen BE, Martires KJ, Ho RS. Psoriasis and the Risk of Depression in the US Population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jan;152((1)):73–9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerdes S, Zahl VA, Knopf H, Weichenthal M, Mrowietz U. Comedication related to comorbidities: a study in 1203 hospitalized patients with severe psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Nov;159((5)):1116–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henseler T, Christophers E. Psoriasis of early and late onset: characterization of two types of psoriasis vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985 Sep;13((3)):450–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gudjonsson JE, Karason A, Runarsdottir EH, Antonsdottir AA, Hauksson VB, Jónsson HH, et al. Distinct clinical differences between HLA-Cw*0602 positive and negative psoriasis patients—an analysis of 1019 HLA-C- and HLA-B-typed patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2006 Apr;126((4)):740–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Löfvendahl S, Theander E, Svensson Å, Carlsson KS, Englund M, Petersson IF. Validity of diagnostic codes and prevalence of physician-diagnosed psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in southern Sweden—a population-based register study. PLoS One. 2014 May;9((5)):e98024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danielsen K, Duvetorp A, Iversen L, Østergaard M, Seifert O, Tveit KS, et al. Prevalence of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and Patient Perceptions of Severity in Sweden, Norway and Denmark: Results from the Nordic Patient Survey of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019 Jan;99((1)):18–25. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015 Nov;172((11)):1075–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15020152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis MC, Lemery-Chalfant K, Yeung EW, Luecken LJ, Zautra AJ, Irwin MR. Interleukin-6 and Depressive Mood Symptoms: Mediators of the Association Between Childhood Abuse and Cognitive Performance in Middle-Aged Adults. Ann Behav Med. 2019 Jan;53((1)):29–38. doi: 10.1093/abm/kay014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valkanova V, Ebmeier KP, Allan CL. CRP, IL-6 and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2013 Sep;150((3)):736–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee CH, Giuliani F. The Role of Inflammation in Depression and Fatigue. Front Immunol. 2019 Jul;10:1696. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang SE, Cohen JM, Ho RS. Screening for depression and suicidality in psoriasis patients: A survey of US dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 May;80((5)):1460–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richards HL, Fortune DG, Weidmann A, Sweeney SK, Griffiths CE. Detection of psychological distress in patients with psoriasis: low consensus between dermatologist and patient. Br J Dermatol. 2004 Dec;151((6)):1227–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data